Museum Artifact: Squirrel Nut Cracker, 1910s

Made By: Kelling-Karel Company / Double Kay / Kelling Nut Co., 217 W. Huron St., Chicago, IL [River North]

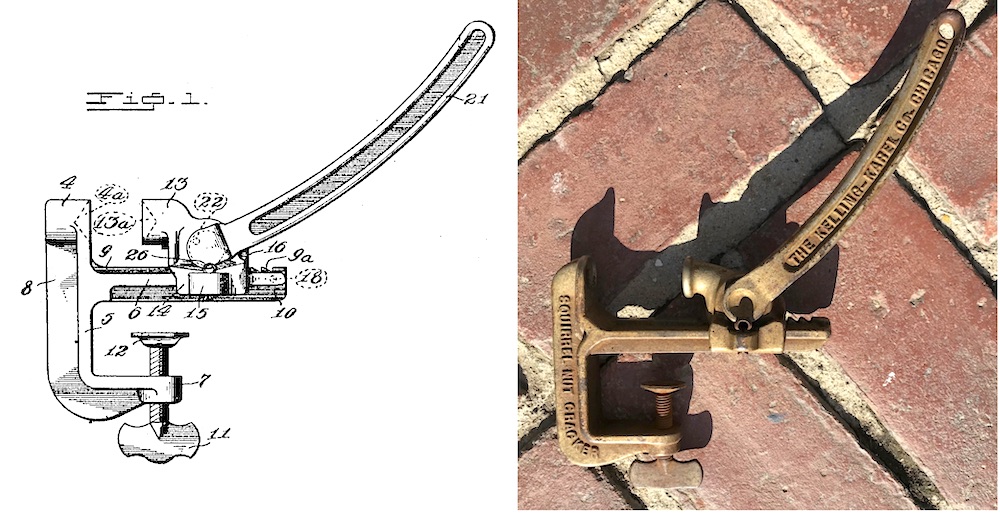

“The ‘Squirrel’ Nut Cracker is suitable for all kinds of table nuts, and is so designed that it cracks the shell but not the kernel. It is adjustable for different sizes of nuts—pecans, hazelnuts, walnuts, etc.. Are all easily cracked with it. The Squirrel Nut Cracker can be attached to the side of the table, and because of its scientific construction, is easily operated even by children.” —blurb in the House Furnishing Review, August 1916

The Kelling-Karel “Squirrel Nut Cracker” pictured above is actually the second such device we’ve acquired for the museum collection. The first—purchased for $5 at the famous Rose Bowl Flea Market in Pasadena, California—didn’t survive the trip back to Chicago. Despite its cutesy name and rusty facade, airport security at LAX deemed it a “potentially dangerous weapon.”

As absurd and embarrassing as it is to have an antique nutcracker confiscated from your carry-on bag while standing there helplessly in your socks with your hands over your head, there may yet be a valuable lesson to be learned from this experience. Sometimes a seemingly innocent thing really does have the potential to do real harm. In the case of the Squirrel Nut Cracker, one need look no further than the way the product was marketed in newspapers across the country 100 years ago.

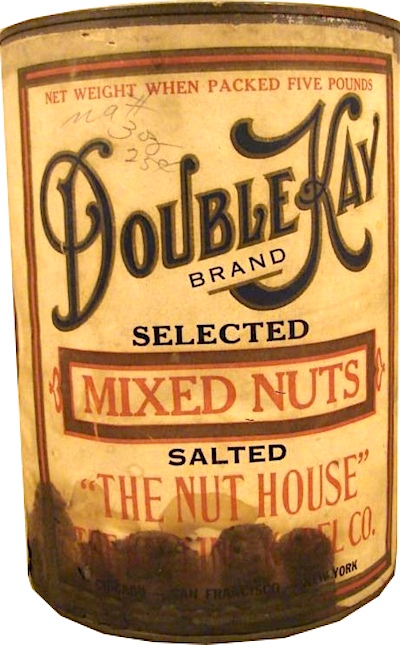

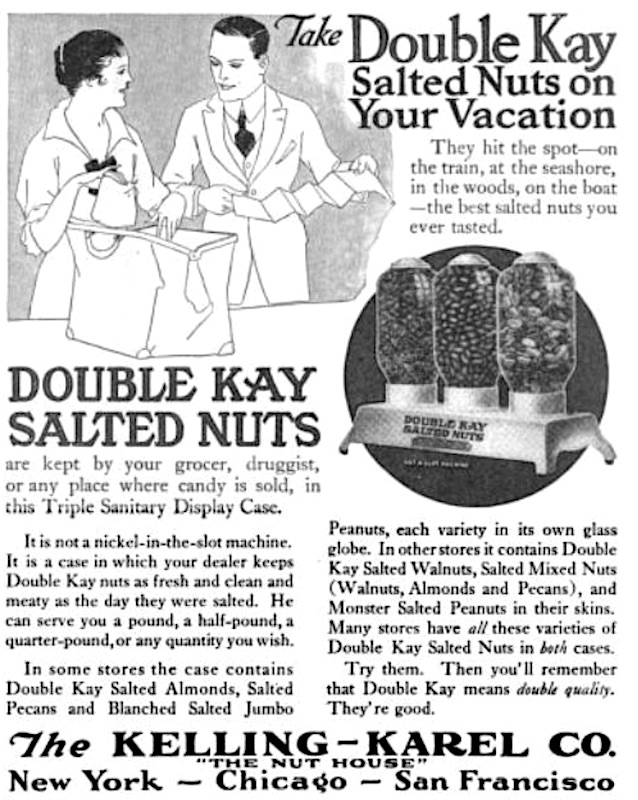

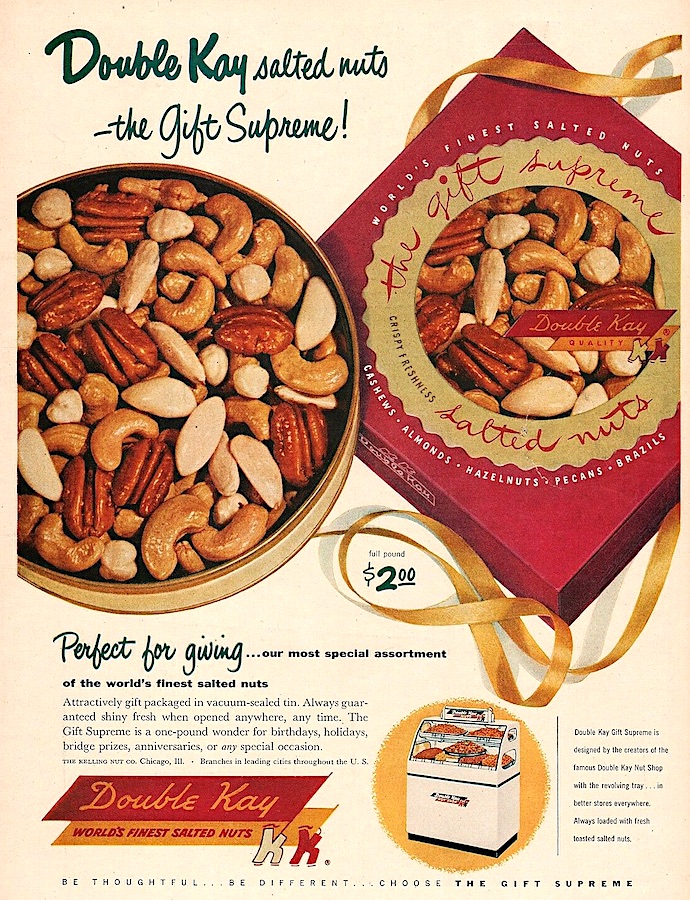

At the time, the Kelling-Karel Company of Chicago was one of the fastest growing “shellers and importers of nuts” in the country, known for their “Double Kay” brand of salted nuts. The company did not manufacture nut crackers, mind you, but merely licensed this funky table-mounted design as a promotional tie-in with their products; particularly well suited for safely fracturing the shell of the increasingly popular Brazil nut.

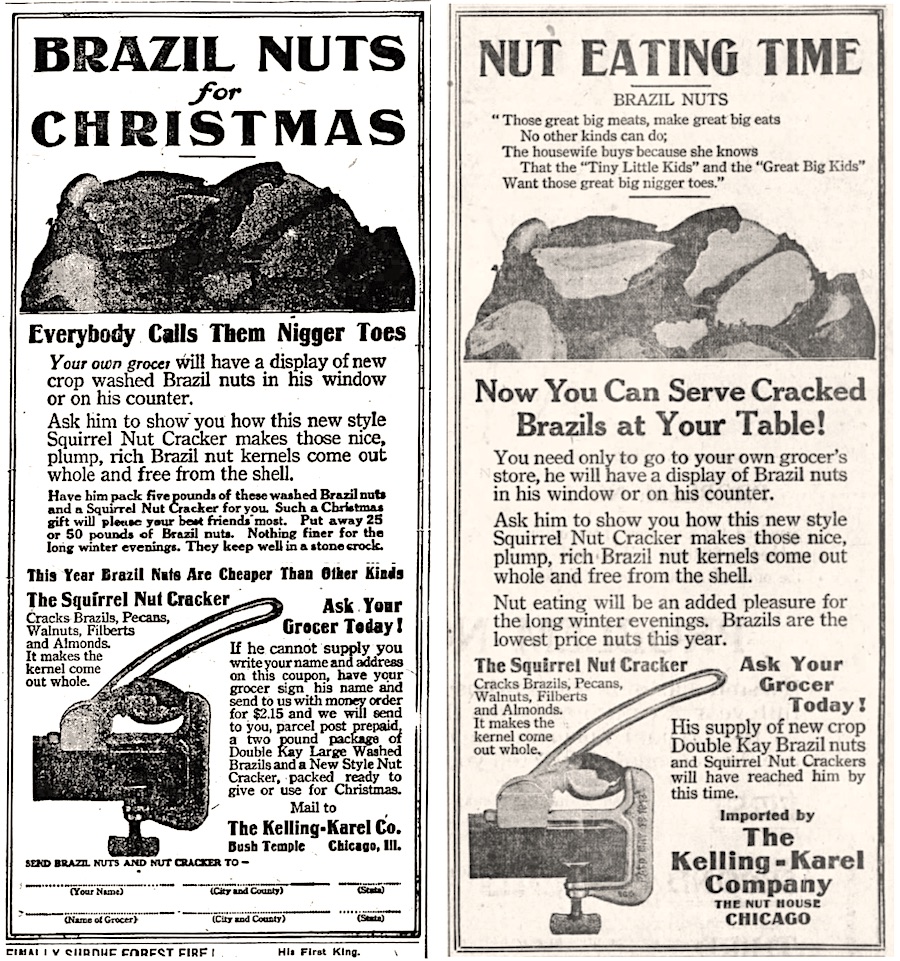

Unfortunately, back in the 1910s (and for decades thereafter), Brazil nuts were widely known and referred to—in mainstream America—by a certain, horrific nickname . . . one you might expect to hear from a KKK member rather than a salesman for KK.

“Everybody Calls Them N***** Toes!” a 1918 advertisement for the Squirrel Nut Cracker shamelessly exclaimed in bold text. “Now you can serve cracked brazils at your table! You need only to go to your own grocer’s store; he will have a display of Brazil nuts in his window or on his counter. Ask him to show you how this new style Squirrel Nut Cracker makes those nice, plump, rich Brazil nut kernels come out whole and free from the shell.”

[A pair of 1918 Kelling-Karel newspapers ads, using common racist slang in the promotion of brazil nuts and the Squirrel Nut Cracker]

Another ad offered up an original Brazil nut inspired poem, just as cringe inducing as you would expect:

“Those great big meats, make great big eats

No other kinds can do;

The housewife buys because she knows

That the ‘Tiny Little Kids’ and the ‘Great Big Kids’

Want those great big n***** toes.”

So, yes, as it turns out, a Squirrel Nut Cracker can be a weapon; just more as an unlikely relic of old-fashioned, carefree American racism, rather than as a makeshift set of nunchucks.

History of the Kelling Nut Company, Part I: “Kelling Me Softly”

Whether you choose to hold the company, its advertising agency, or the realities of 1910s American society responsible for the Squirrel Nut Cracker’s unfortunate promotional campaign, we shall carry forward nonetheless with a bit of context on the business behind the artifact.

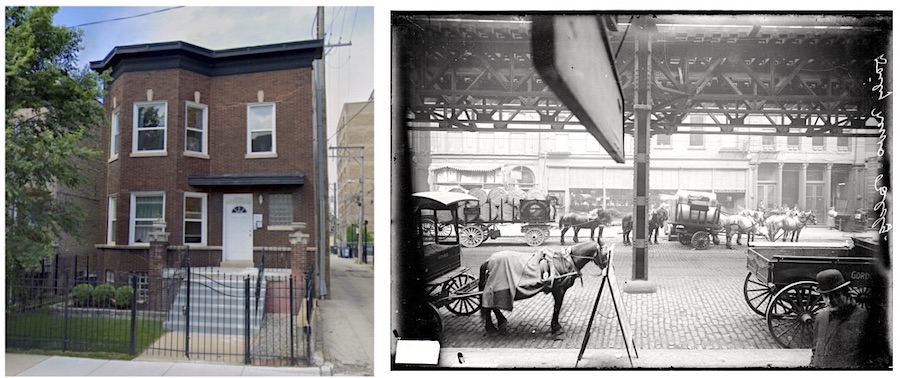

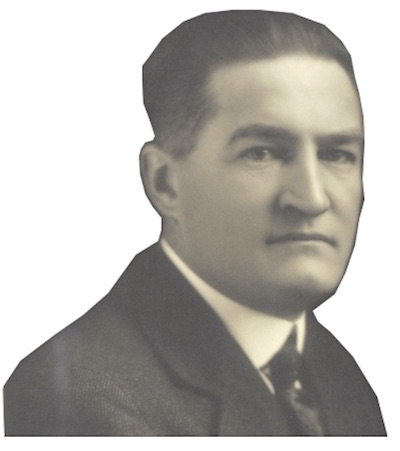

M. J. Kelling & Company—later to become the Kelling-Karel Co. and even later, the Kelling Nut Co.—was organized around 1906. According to one light-hearted, retrospective piece in a 1964 issue of the Chicago Tribune, company founder Max J. Kelling started out “roasting nuts in his mother’s Milwaukee kitchen and selling them door to door”—helping to support the family after the death of his father. From there, “he outgrew Milwaukee, came to Chicago, opened the Kelling Nut Company, and sold nuts to stores via horse and wagon.

“By the age of 27, Mr. K. had cornered the pecan market—which is bound to make a man a little proud—and had become a millionaire.”

That’s obviously the short and sweet version. A deeper dive into Max Kelling’s past reveals a tad more complex character than your average baby-faced, buggy-driving peanut dealer.

Born in Milwaukee in 1881, Kelling was the son of German immigrants, and his father Frederick did indeed die when he was quite young. Max’s youthful ambitions and self-sufficiency went well beyond pecan hawking, however, as he earned himself a law degree from the University of Wisconsin and served as the chief deputy clerk in the courts of Milwaukee County up until the age of 25—when he unceremoniously split for Chicago.

Max’s older brother Alfred H. Kelling was a professional food chemist with a degree from MIT, and it’s likely that his insider knowledge of that industry played a role in his little bro jumping into the field.

[Left: A home at 1056 W. Foster Avenue, where Max and Emma Kelling lived in 1910. Right: A view of horse-and-buggy merchants on Chicago’s Fifth Avenue (now known as Wells Street) in 1911. One of Kelling’s first offices was located on this street, and he likely sold nuts in this same location.]

In 1907, after finding considerable success during his first year in the nut trade, “Max Kelling decided things were pretty good, and took a trip to Europe,” according to the Tribune. “But his business associates sold him out, and he came home owning three pecans and several toothbrushes.”

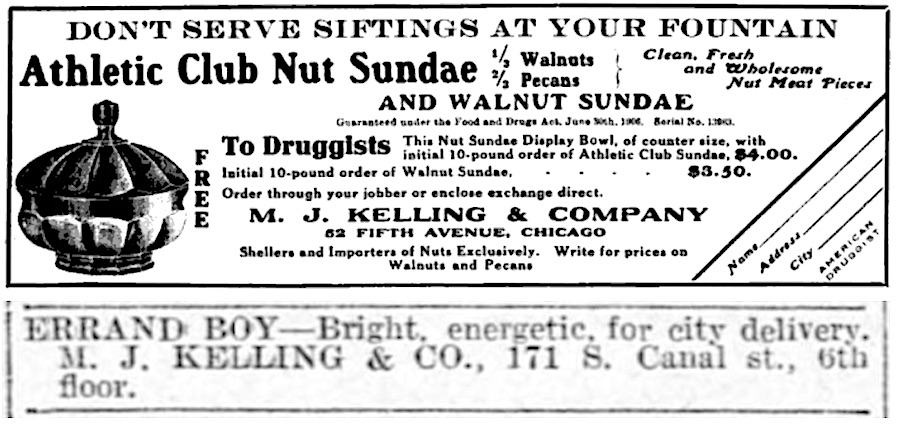

Fortunately, this appears to have been a brief setback, as M. J. Kelling & Co. was doing a strong business once again by 1908, opening offices at 52-56 Fifth Avenue (now Wells Street) and 171 S. Canal St (sixth floor). Among their biggest clients during this period were druggists and candy shops—any place with a soda fountain—as the relatively new concept of the ice cream sundae had created much greater demand for dessert nut toppings. Kelling was among the early suppliers that leaned into the trend, inventing its own sundae recipes in an effort for exclusivity.

[Above: 1908 advertisement for M. J. Kelling & Company’s “Athletic Club Nut Sundae.” Below: A 1908 ad in the Tribune, seeking an “errand boy” to work at the Kelling & Co. offices on 171 S. Canal Street]

“Every soda fountain should serve Athletic Club Nut Sundaes, made from a delicious combination, one-third walnuts and two-thirds pecans,” read one blurb in the American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record. “M. J. Kelling & Co., 52 Fifth Avenue, Chicago, shellers and importers of nuts, prepare the nuts for these sundaes, as well as for Walnut Sundaes, from clean, fresh and wholesome nut meat pieces. . . . The firm is one of the few houses who are making a specialty of shelled nuts, and its success is attributed to the fact that specialization makes it possible to give the line the attention which it deserves.”

In 1909, the short-lived M. J. Kelling & Co. was re-organized once again, this time emerging as the Kelling-Karel Company. Shortly thereafter, the firm’s most enduring product line was introduced: “Double Kay” salted nuts. That name alone gives the impression that Max Kelling had found himself an equal partner in crime; a Laurel to his Hardy, a Tinker to his Evers. But the “Karel” in Kelling-Karel—the second “kay” in Double Kay—doesn’t seem to fit that mold. In fact, it has taken us a surprising amount of effort just to figure out who this Mr. Karel actually (probably) was.

II. The Mysterious Mr. Karel

“As a delicacy and a wholesome food, for dinners, parties, luncheons, for auto trips, picnics, excursions and summer outings, nothing can surpass salted nuts when of good quality. . . . Double Kay Salted Nuts are prepared in our sanitary kitchens. They are packed in metal boxes, to keep them fresh and crisp. Each box has a glass cover, so you can see the selected quality of each purchase. Our automobile delivery makes it possible for you to secure the Double Kay salted nuts fresh every day at all first class dealers. A box today will please everyone at your table.” —Kelling-Karel Company advertisement, 1910

There were four varieties of Double Kay salted nuts in 1910: almonds (imported from Spain), pecans, pistachios (imported from the Black Sea district), and assorted table nuts. Details like that are widely documented in newspapers and trade magazines of the period. Any information about the mysterious Mr. Karel in the Kelling-Karel partnership, however, proves almost suspiciously absent from the public record—not just in 1910, but in any historical accounts of the business.

There were four varieties of Double Kay salted nuts in 1910: almonds (imported from Spain), pecans, pistachios (imported from the Black Sea district), and assorted table nuts. Details like that are widely documented in newspapers and trade magazines of the period. Any information about the mysterious Mr. Karel in the Kelling-Karel partnership, however, proves almost suspiciously absent from the public record—not just in 1910, but in any historical accounts of the business.

He was, it seems, as much a myth as a man—save for a single, solitary reference we managed to unearth in a 1911 edition of the Lakeside Annual Directory of City of Chicago. Here, you can skim through the alphabet and find a “Karel, John C., v. pres., Kelling-Karel Co., 217 W. Huron”—though, unlike most businessmen listed in the book, no home address is provided.

This was just enough information for us to piece together a probable—albeit unofficial—explanation of how Kelling-Karel and Double Kay came to be.

As mentioned earlier, Max Kelling was a law clerk in Milwaukee before becoming the pecan king of Chicago. Well, in what seems unlikely to be a coincidence, one of the county court judges he worked under was a man named John C. Karel (b. 1873)—a fellow Wisconsin law school graduate; former football star for the Badgers; and a rising political force in the Democratic Party.

Unlike Kelling, John C. Karel never left Milwaukee. The good judge was still presiding over cases in that city up until his death in 1938. Despite his apparent temporary designation as “vice president” of the Kelling-Karel Co., it’s unlikely he had any active role in the day-to-day business of the Chicago firm, either. What he probably did do in 1909 was offer up some financial assistance to an old protege . . . agreeing to invest in Max Kelling’s growing enterprise in exchange for a cut of the profits and his name on the banner.

As his profile quickly escalated in Wisconsin politics in the ensuing years, however, Judge Karel might have intentionally distanced himself from the Double Kay association a bit. In 1912, in particular, Karel—at just 39 years of age—suddenly found himself the Wisconsin Democrats’ nominee for governor . . . and there was nothing nutty about it.

“A judge campaigning for the first office in the state stirred Wisconsin this last year in a manner the historic Badger commonwealth had not been treated before,” wrote John G. Pallange of the Milwaukee Press Club, following Karel’s loss in that election. “The jurist upset political traditions, astonished the voters with the dignity yet energy of his campaign, traversed the 54,000 square miles up and down from side to side, and emerged from the contest with the judicial ermine untarnished. He was not elected; but he accomplished a feat for the Democratic party. A Republican plurality of 84,000 four years ago was reduced to 11,000.”

[Aluminum campaign token from one of John C. Karel’s runs for governor of Wisconsin. “Vote for John C. Karel,” it says, “Because he stands for lower taxes, less inspectors, university out of politics, government back to the people.”]

The judge got another crack at the governor’s mansion in 1914, but lost again. Still, over 100 years later, John C. Karel is regarded as a significant enough historical figure to warrant having his own Wikipedia page. Unfortunately, that page—and every other bio we came across—makes no mention of the Kelling-Karel Company amongst his accomplishments or business interests. So, I suppose in terms of confirming our various theories—as the judge himself might have said—the jury is still out.

By 1924, Max Kelling made something of a moot point of the mystery anyway, as the Kelling-Karel Company was officially scrapped and reorganized under the banner of the Kelling Nut Company. The popular “Double Kay” brand name was retained after the change, albeit under less obvious pretenses. “Double Kay means double quality,” one ad read.

III. “The Nut House”

If John C. Karel really was the key financier behind Kelling-Karel, that it’s safe to say it was a more fruitful pursuit than his gubernatorial races. With Max Kelling and company secretary Henry E. Schrubb running the business in Chicago, the 1910s saw Double Kay emerge as a national powerhouse brand.

“Eight years ago a hair-trigger man named M. J. Kelling started putting up five and ten-cent packages of salted nuts,” one ad read in a 1917 issue of Printer’s Ink. “Today the Kelling-Karel Co., New York, Chicago and San Francisco, is one of the two or three largest factors in this country’s shelled and salted nut business. They have won jobbers, dealers and public to DOUBLE KAY SALTED NUTS by attractive, practical ‘Big Deals’ and the Triple Sanitary Display Case.”

“Eight years ago a hair-trigger man named M. J. Kelling started putting up five and ten-cent packages of salted nuts,” one ad read in a 1917 issue of Printer’s Ink. “Today the Kelling-Karel Co., New York, Chicago and San Francisco, is one of the two or three largest factors in this country’s shelled and salted nut business. They have won jobbers, dealers and public to DOUBLE KAY SALTED NUTS by attractive, practical ‘Big Deals’ and the Triple Sanitary Display Case.”

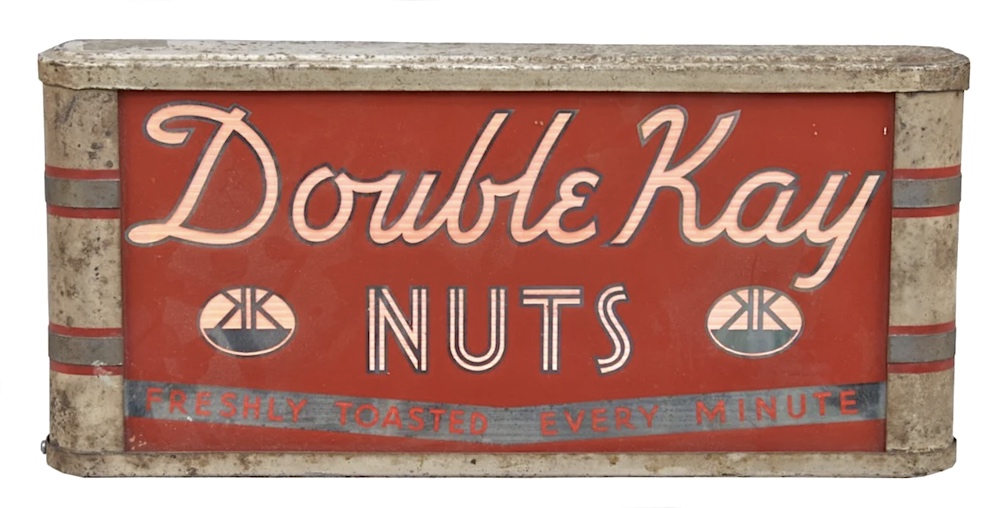

Double Kay nuts were a different sort of commercial snack from the pre-packaged candy bars or Cracker Jacks of the same era. While some were sold in sealed tins and lined up on grocer’s shelves, many more were sent to dealers in bulk, along with exclusive glass display cases and carry-out boxes that not only kept the product “fresh and clean,” but also aesthetically eye-catching to passersby.

“Look well at this display case,” read a 1917 ad in the Saturday Evening Post. “It holds salted nuts of a quality, freshness and variety such as few merchants have ever been able to offer in the past. It is not a slot machine. Your druggist, grocer, or any other dealer who sells candy, has it on his counter. From it he can supply you with any quantity you desire.”

Over time, Max Kelling was quite active in the design and production of his display cases, collecting patents on several himself, and always emphasizing the Kelling display as a sort of “shop within the shop.”

Meanwhile, over at 217 West Huron Street, the factory workforce was growing exponentially; with immigrants making up a large portion of the staff. As a German-American employing a large team of non-English speakers, Max Kelling soon found himself having to “prove” his patriotism after World War I broke out. In a new era of anti-immigrant fervor, public acts of flag waving went a long way.

In one report from 1917, Kelling gathered 147 of his foreign-born employees together to encourage them to buy war bonds, or “Liberty Loans,” as they were known.

“The meeting was unique,” according to a blurb in the The Furniture Worker. “Because most of those present could not speak English, arrangements were made for quartettes to sing ‘America’ and other national patriotic songs in their native tongues, each group joining lustily when the tongue he understood was reached. In an interview Mr. Kelling said: ‘I’m proud of my fellows. We have a regular melting pot when it comes to nationalities and they are enthusiastic about the war loan. Those who didn’t subscribe merely went home to talk it over. Every employe in the plant will have a bond by the end of the week. Every plant in the city, or elsewhere, can do the same thing if the employer will only give his men the cue and take the leadership in getting them interested.”

It was during this same time period, incidentally, that Kelling-Karel became “exclusive distributors” of the Squirrel Nut Cracker; the gadget that sparked our research in the first place.

There’s probably no way to determine where most of these devices were actually manufactured, but we know the design was developed by a Mr. Wiley N. Gradick of the Woldert Grocery Co. in Tyler, Texas, and that it was patented on May 13, 1913.

“A new nut cracker is being put on the market which is said to possess many strong points,” The Hardware Reporter noted that year. “It is known as the Squirrel Nut Cracker, and was devised by the Woldert Grocery Company, Tyler, Tex. The rapidity with which nuts of varying sizes can be inserted between the concave jaws is a feature of the cracker on which strong stress is laid. After the nut is inserted, with an upward and forward swing of the 7.5 inch lever, sufficient pressure is exerted to crack shells without injuring the meat.

[Left: Drawing from Wiley N. Gradick’s 1913 patent. Right: The first Squirrel Nut Cracker we acquired for the Made In Chicago Museum, which wound up getting confiscated at the L.A. airport]

“The cracker is made of cast metal and has an extreme opening of 1-7/8 in. The two heads are 7/8 in. diameter, with concave surfaces of 11-16 in. diameter to receive the ends of the nuts. The base on which the ratchet sliding jaw and lever works is 5-1/4 in long, and the clamp opening has a capacity of 1-1/4 in. Any table nut, up to and including the largest hickory shellbark, can be cracked by sliding the movable jaw against the nut, then raising the handle, so that the pawl or latch housed in the movable casing catches, when pressure on the nut will crack it with an easy movement, properly graduated.”

Kelling’s association with the Squirrel Nut Cracker seems to conclude by the 1920s, but overall, business was still picking up.

In 1921, Chicago Commerce reported that “the Kelling-Karel Co. is said to be the largest manufacturer of shelled nuts in the world, and the location of the company here gives Chicago a new and growing industry.”

The following year, the company established a new HQ and plant in the North Pier Terminal building at 365 E. Illinois Street, and by 1924, the re-branded Kelling Nut Co. was officially on its way to world domination . . . or as close as one can get with 5-cent bags of salted nuts.

[The Kelling Nut Company had manufacturing and service facilities in the North Pier Terminal building, 365 E. Illinois St., from 1922 into the 1950s]

IV. Fully Authorized

There were, of course, more “financial reverses” to come, as the Tribune later put it, but none that Max Kelling couldn’t slink his way out of. “On one occasion, working 24 hours a day, he sought a bank for refinancing, went into the board of directors room, and went to sleep. This won him the loan, as a bank official said, ‘Anyone who can sleep in our board of directors room is bound to be successful.’”

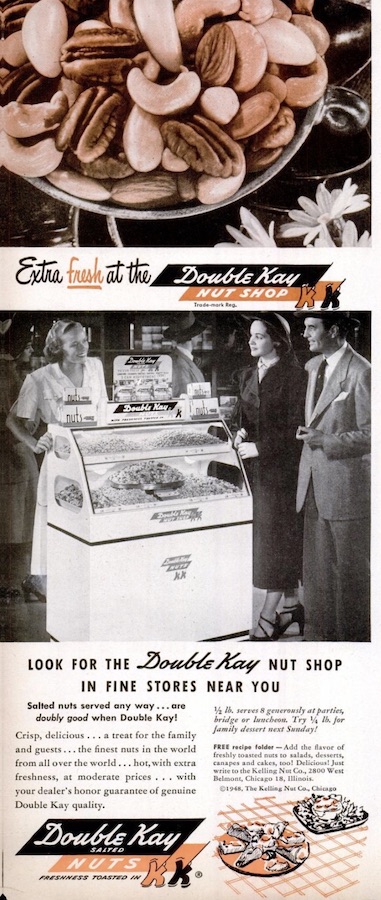

During the brutal 1930s, the Kelling Nut Co. established a sort of franchise system for its carefully conceived Double Kay Nut Shop. If a drug store or candy shop agreed to exclusively carry Kelling nuts and display and prepare them in the style dictated by the company, they could then advertise themselves as having an “Authorized Double Kay Nut Shop.”

“Nuts from all over the world,” read one 1932 ad for the Crispy Corn Shop, an authorized dealer in Woodland, California. “Watch us toast them right before your eyes—marvelous peanuts from the sunny South; flavory almonds from the Mediterranean; rare cashews from Mangalore; alluring pecans from Dixie. They’re fine food for the children, and you’ll want a supply for your next bridge party. Visit our nut shop department, or phone your order.”

The Double Kay Nut Shops were a great success and remained a staple of the business for many years, even through logistical challenges posed by the Depression and World War II.

The Double Kay Nut Shops were a great success and remained a staple of the business for many years, even through logistical challenges posed by the Depression and World War II.

As Max Kelling told Billboard magazine in 1944, 55% of the normal American peanut crop generally went to salters and candy manufacturers, and 50% of that amount was earmarked for overseas shipments to the Armed Forces in the midst of the war, leaving a considerable shortage in some Double Kay display cases. Ever the optimist, though, Kelling noted that “peanut acreages are being greatly increased, and a new crop is expected to provide reasonable quantities for all purposes.”

The company emerged from the war on an upswing, as Double Kay—“World’s Finest Salted Nuts”—were available not only in Double Kay Nut Shops around the country, but increasingly in vacuum-packed gift tins available at grocers and supermarkets.

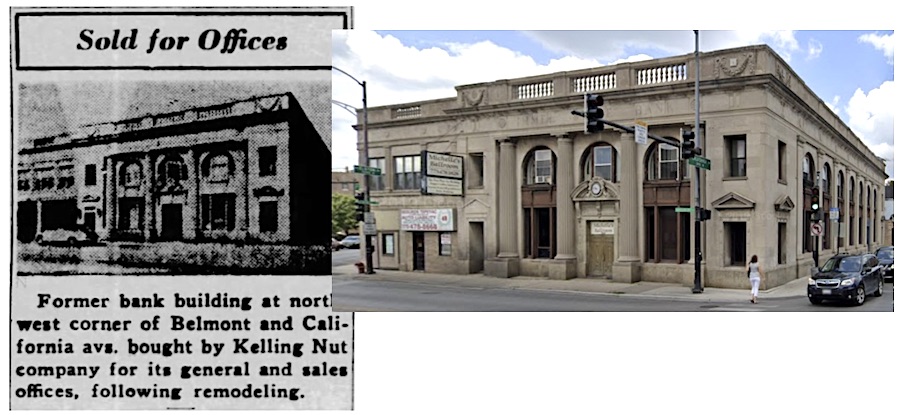

In 1947, Kelling Nut announced a new headquarters for its general and sales offices, taking over a neoclassical bank building at 2800 W. Belmont Ave.—one that had been closed since the banking panics of 1930-31.

“During the Depression,” Kelling executive VP Robert Patience later said, “many banks took over nut companies. But we’re probably the only nut company that ever took over a bank.”

[Left: 1947 article reporting Kelling moving its offices to the former Immel State Bank Building. Right: The same building, at 2800 W. Belmont Ave., still standing today; currently operating as “Michelle’s Ballroom.”]

V. 500,000 Tons and What D’ya Get?

You can patent display cases and trademark brands and slogans, but if you’re in the business of selling nuts, in the end, there are limits to how much you can really do to fend off the competition . . . outside of paying top dollar for the crop itself. After the war, Kelling’s share of the market gradually shrunk, as the nature of its competitors began to change. On one hand, there were numerous regional nut companies with their own footholds in certain parts of the US—the Peterson Nut Company of Cleveland, as one example, had a president coincidentally named Donald Kelling . . . somehow of no relation to Max (though they did have business dealings). As a larger threat, though, were the big food conglomerates, which had bottomless pocket books and much stronger distribution networks than any stand-alone nut specialist. Even the famed Planters Nut Company—one of the longtime competitors of Kelling—was purchased by Standard Brands in 1960.

On the bright side, the Kelling Nut Co. was positioned for a peaceful transition of power. In 1957, Max Kelling—age 76—was named company chairman, and his son Robert S. Kelling, 45, assumed the presidency; remaining in the role for the next 15 years.

Old Max never properly retired, however, nor did he ever seem to lose the ambitious spirit that had got him into the business in the first place. At age 82, he even went back to college, pairing up his long abandoned Wisconsin law degree with another one in philosophy, this time from Loyola-Chicago. As late as 1964, Max was still attending “the occasional company gathering,” the Tribune noted, “perhaps attired in black shirt, red tie, and beret; a costume which you have to be rich to get away with.”

A survey—conducted by the Kelling Nut Co. itself—indicated they were still “the country’s No. 1 favorite nut” in the 1960s, “to the tune of some 500,000 tons annually.” By this point, the company had plants operating in Paterson, NJ, Albany, GA, Baconton, GA, and Burlingame, CA. The general offices remained in the bank building in Chicago, but local production—the “Made in Chicago” part—had largely dried up.

America’s favorite or not, Max and Robert Kelling finally decided there was no real viable future for the Kelling Nut Company as an independent family business. Their decision to sell the firm to the Corn Products Company of New York in 1967, however, did tie back to another family connection. Max’s late brother Alfred Kelling—the chemist who’d help inspire him to get into the snack food business—was also the head of the technical department at Corn Products for many years, right up until his death in 1963. So there was likely some built-in trust that CPC would carry the Kelling name into a better future.

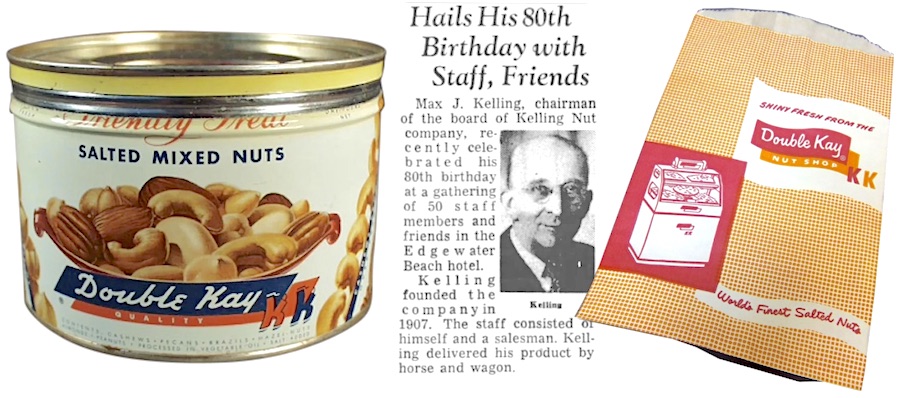

[Several items (not part of our collection) from Kelling Nut Company’s later years in the ’50s/’60s: a Double Kay Salted Mixed Nuts tin, a newspaper clipping from Max Kelling’s 80th birthday celebration in 1961, and a take-away bag used with the Double Kay Nut Shop.]

But alas, there would be no return to the glory days for Double Kay.

Following the death of Max Kelling in 1969, the business was eventually taken over in the ‘70s by the conglomo-giant General Foods. It was sold again in the 1980s—along with its old rival the Peterson Nut Co.—to a company called Fairmount Snacks Group, Inc. As late as the early 2000s, Fairmount maintained a brand called “Kelling Kernel Fresh,” which was tied in with Peterson’s products. But after Kanan Enterprises purchased Peterson Nut in 2003, it merged that brand with another historic Cleveland nut business, forming “King Nut Companies.” From there, references to the old Kelling name seem to disappear, save for the occasional appearance on rusty antique nutcrackers—be it in a museum, or the confiscated objects room of the Los Angeles International Airport.

SOURCES

King Nut Company History – KingNut.com

“Announcement” – Kelling-Karel ad, Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1910

“Double Kay Salted Nuts” (ad) – Printer’s Ink, June 28, 1917

“Double Kay Salted Nuts” (ad) – Saturday Evening Post, June 9, 1917

“Peanut Situation” – Billboard, May 13, 1944

“Hails His 80th Birthday with Staff, Friends” – Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1961

“Corn Products Promotes Debry” – The Record (Hackensack, NJ), Aug 15, 1967

“Americans Don’t Like Shelling Their Peanuts” – Fond Du Lac Commonwealth Reporter (Wisconsin), July 12, 1968

Lakeside Annual Directory of City of Chicago, 1911

Max J. Kelling obituary – Chicago Tribune, Oct 18, 1969

“Peterson vs. Johnson Nut Co.,” Supreme Court of Minnesota, March 7, 1941

“Kelling Nut Company elected Max J. Kelling Chairman” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 5, 1957

“Squirrel Nut Crackers” – House Furnishing Review, August 1916

“A Line O’ Type or Two: ‘Nuts'” – Chicago Tribune, October 20, 1964

“Sold For Offices (Immel State Bank Building)” – Chicago Tribune, March 23, 1947

U.S. Patent 1061470A: “Nutcracker,” 1913

“Hint to Buyers” – American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record, Sept 1908

Archived Reader Comments:

“Hi, l find a can from that company, not opened, full with penauts, l think that is from WWll, by the place where l find can. Is that can have some value? I m from Serbia, and l guess that this come here with some of shotdown american pilots in WWll…” –-Max, 2019

I managed the Kelling Nut Co. plant in Patterson, NJ when it was owned by CPC Int’l in the late `1960’s.

I was born in 1949 and grew up in Hinsdale, Illinois. Sometimes when I was in the shopping district, as a kid with a little money, if I was hungry I would walk to Van’s drug store and buy a 1/4 pound of Double Kay Spanish peanuts, which would fill me up.

$0.15 + 4% sales tax ($.01) = $0.16

Cheapest lunch I could buy. 😀

My great grandpa Gus Kelling was also Max’s brother and he was involved in the company too. He went to Brazil at least once and patented in his own name Brazil nut shelling machinery and other nutty inventions. Big complicated machines- I looked up the patents and saw the drawings… He may have had something to do with your little nutcracker. His wife Lilly Schulz died in 1909 from diphtheria leaving 2 young daughters and the older one Florence got brain damage from a high fever during the 1918 “spanish” flu pandemic, and had to be institutionalized… These sad things happened. My grandma who I knew well, Katherine Kelling, the surviving child, was always told that SHE was the inspiration for the double k name- hahaha. Anyway thanks for the article. I’d like to learn even more about my family history.

Hello. Could you please tell me if I can get replace lids for the glass container? I recently purchased a Double Kay salted nut descender and it did not have the right kids. Please and thank you.

Sincerely

Dixie

Recently acquired a squirrel nut cracker. Patd. in May 18, 1913.. Really cool item. Would like some feedback on, is it rare, is it soult after, is it valuable. Don’t mind if you email me…cdonpitts937@gmail.com. Enjoyed the read!!!