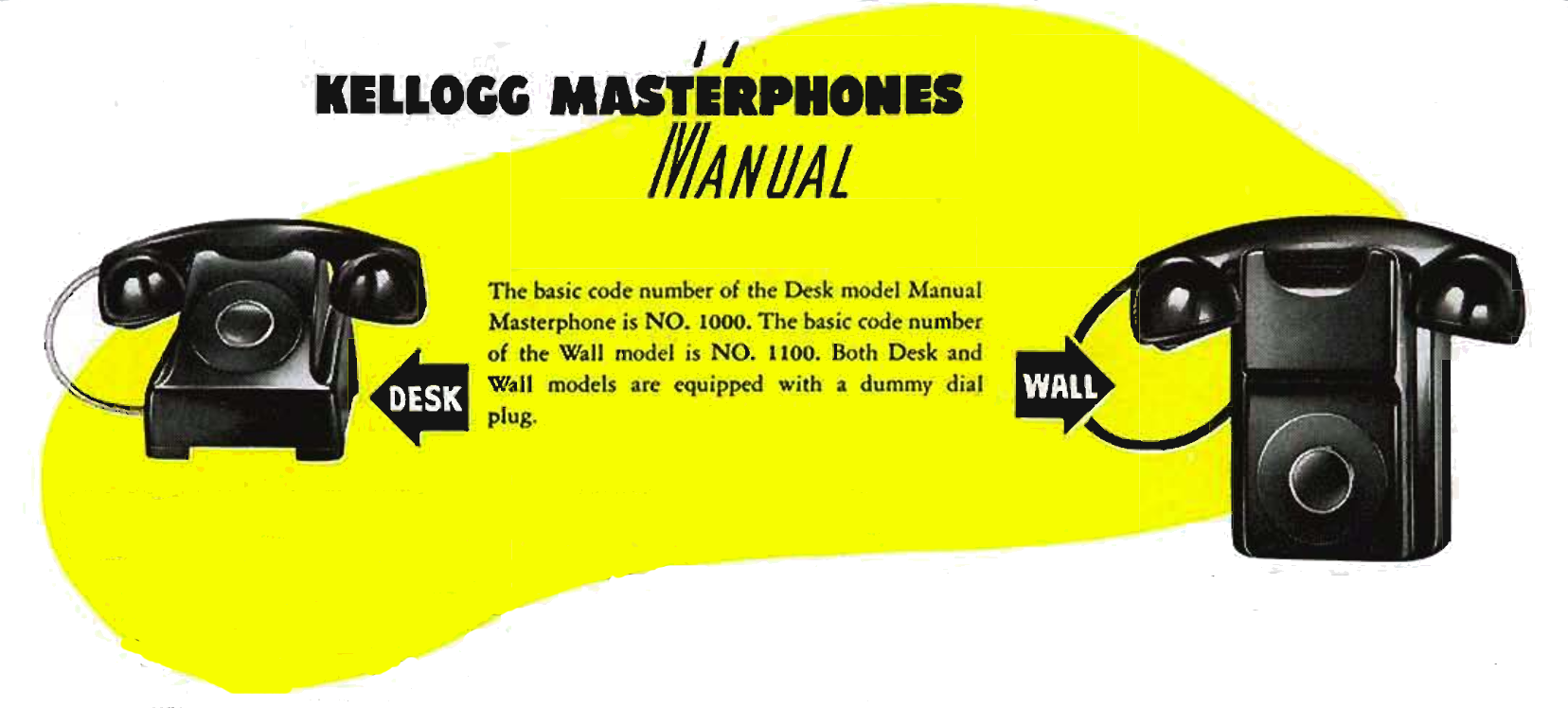

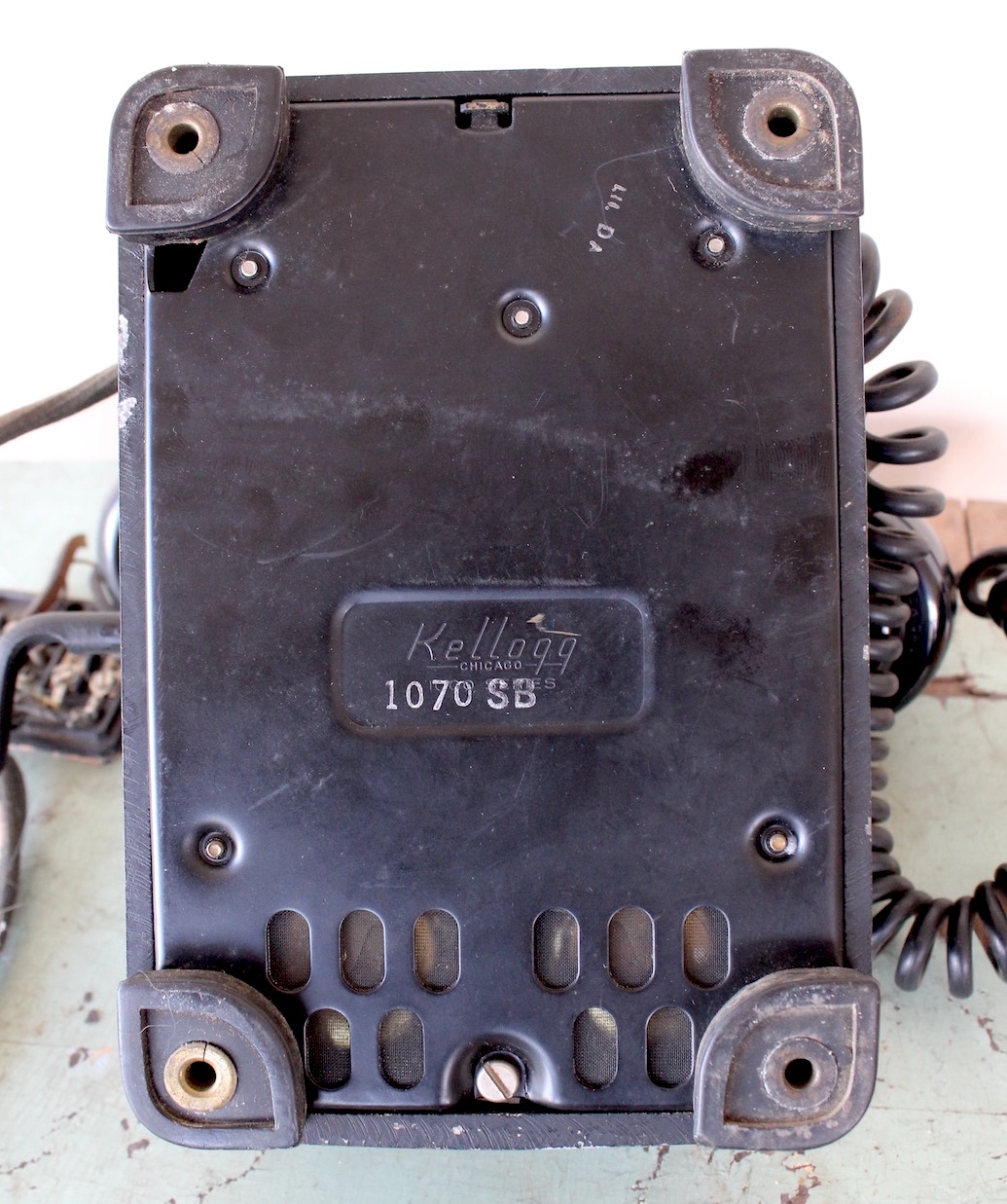

Museum Artifact: Kellogg Redbar 1000 Series Masterphone, 1952

Made By: Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Co., 6650 S. Cicero Ave., Chicago, IL [Bedford Park]

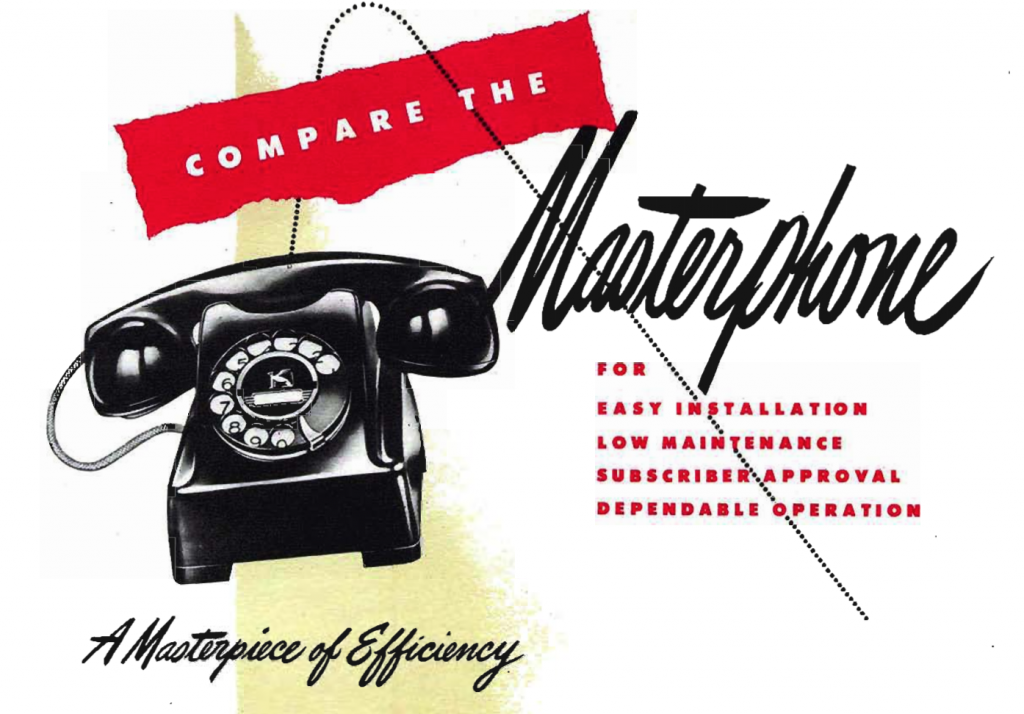

Widely promoted during the Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Company’s 50th anniversary in 1947, the 1000 Series “Redbar” Masterphone—like the one in our collection—is a bit of a postwar icon. It might not have the rich oak exterior of an early box phone or the brass shimmer of an old candlestick model, but compared to the way most mid-century phones were shedding sex appeal with each technological advancement, the curvaceous Redbar was the bakelite black beauty of its day.

“In less than one short year, the Kellogg 1000 Series Masterphones have become the talk of the telephone world,” according to one of the company’s own 1947 sales pamphlets. “These amazing new telephones, featuring years-ahead simplicity of design, inter-changeability of universal parts and new accessibility, have been delivered to telephone companies everywhere.”

“In less than one short year, the Kellogg 1000 Series Masterphones have become the talk of the telephone world,” according to one of the company’s own 1947 sales pamphlets. “These amazing new telephones, featuring years-ahead simplicity of design, inter-changeability of universal parts and new accessibility, have been delivered to telephone companies everywhere.”

Indeed, the Redbar wasn’t just popular for its good looks. According to a 2004 article by former Kellogg employee Roger Conklin in the Telephone Collectors International newsletter, Singing Wires, this phone was a step ahead of its contemporaries on the inside, too.

“Rather than the mass of tangled wires connecting the various components together in other telephones, there is instead a one-piece molded interconnecting block that includes the bright red hook switch. The condenser and induction coil are fully encapsulated and equipped with plugs that are inserted into sockets just like tubes in the radios of that era. . . . Screw terminals are clearly marked with their function. There is no confusion, such as exists with other kinds of phones from that era, about which wire goes where if cords or internal components are disconnected and replaced. Installation and repair was a cinch.”

Conklin also notes that “with the 1000 Masterphone, Kellogg was the first to introduce a manual screwdriver adjustment which the telephone installer could use to fine-tune the transmitter current to more closely match the line to which it was connected.” This, along with Kellogg’s new Decimonic ringing frequencies, helped cut down on white noise interference and ensure that party-line users only heard their phone ring when a call was specifically intended for them, rather than the neighbors.

The Redbar phone in our own collection (manufactured in 1952) has a blank dial, meaning it was used for manual service. This could be swapped out with a proper automatic rotary dial with a quick plug-in-and-go feature—another innovation.

The Redbar phone in our own collection (manufactured in 1952) has a blank dial, meaning it was used for manual service. This could be swapped out with a proper automatic rotary dial with a quick plug-in-and-go feature—another innovation.

I could go much, much deeper into the techno-babble of obsolete communication devices, but the more important idea is this—Kellogg, even after 50 years, was still consistently pushing boundaries in its industry and carrying on the legacy of its late founder, Milo Kellogg. Things were looking good at the company’s Cicero Avenue plant in the late 1940s, as peacetime optimism set in and the Masterphone did strong sales. In the tech biz, though, yesterday’s accomplishments always pale in comparison to tomorrow’s challenges.

In 1951, during the middle of the Masterphone Redbar era, Milo’s son James G. Kellogg retired as company chairman. Shortly thereafter, third-generation president James H. Kellogg agreed to sell the family business to the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. (ITT), forming a new entity called ITT-Kellogg. By the following decade, the entirety of that operation, and its roughly 1,000 jobs, all departed Chicago for plants in Tennessee and New Jersey. A few decades and several business deals later, the Kellogg name slipped out of use, and the significant contributions of the Kellogg family were largely forgotten right along with it.

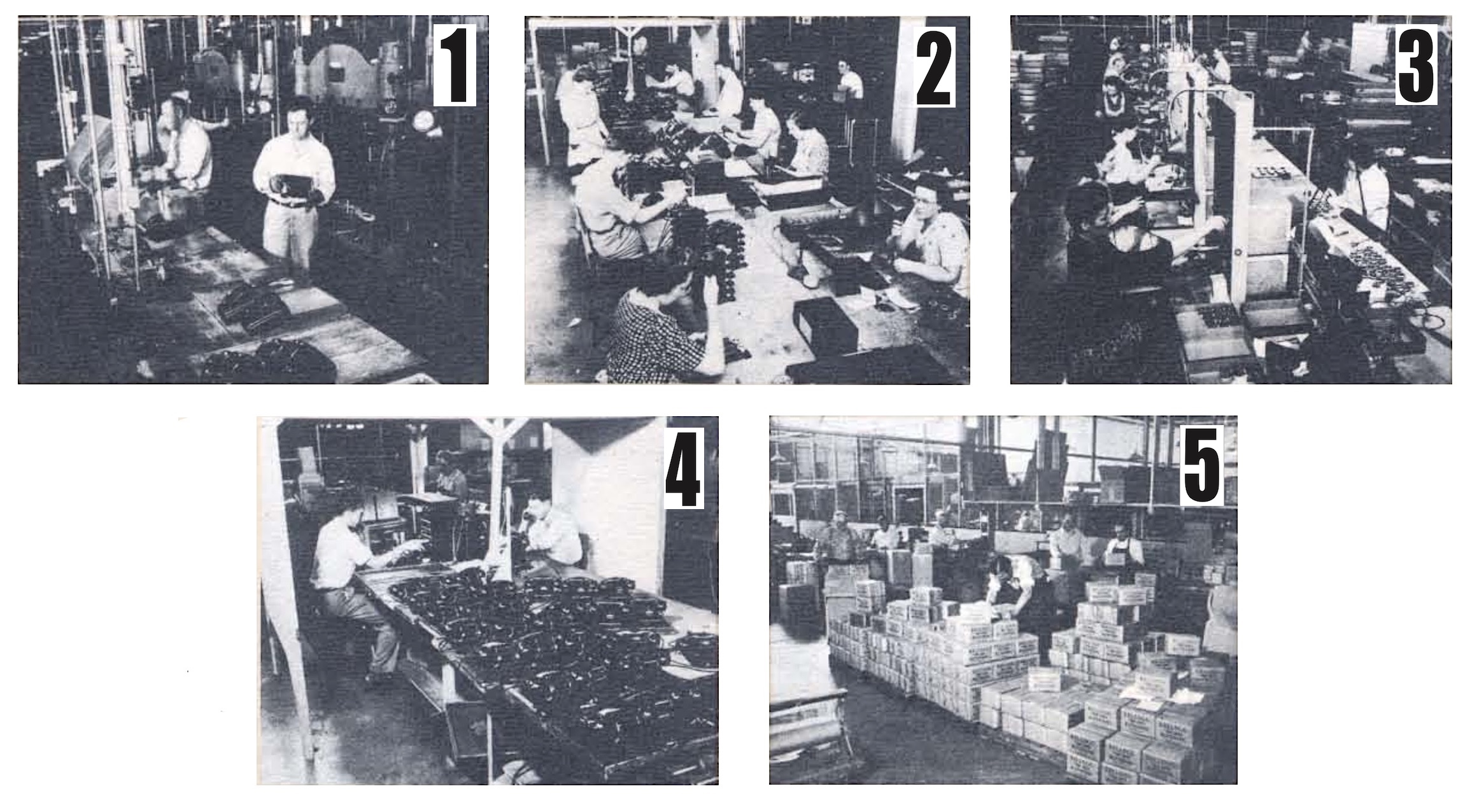

Kellogg Factory Workers Building the Masterphone 1000 Series at 6650 Cicero Ave., 1947:

1. Phone housings are molded in 200-ton hydraulic presses.

2. Ringers and block are mounted to base, and condensers & induction coils are plugged in.

3. The receiver’s 22 fragile parts are assembled under a magnifying glass.

4. Final inspections of each completed Masterphone.

5. Off to the shipping department.

Milo Kellogg: Freedom Fighter

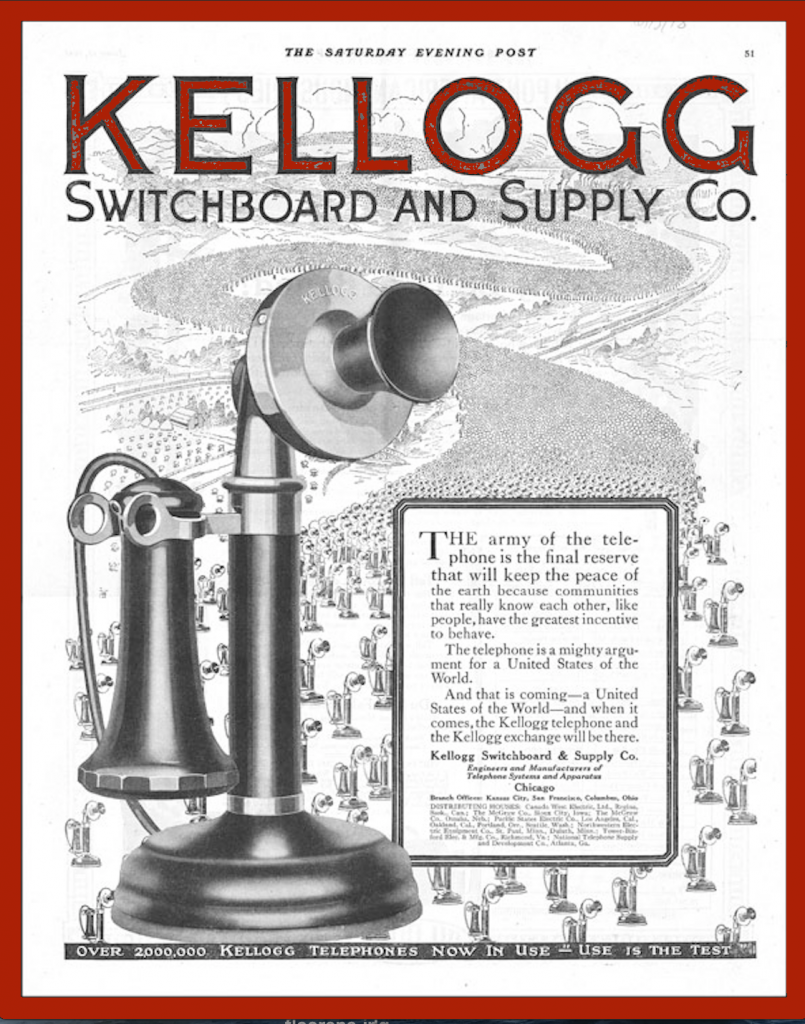

If Elisha Gray is the under-appreciated genius of the American telephone story, then Milo Kellogg’s whisper-soft obscurity ought to be considered at least twice as unjust. For a man once deemed “synonymous with the telephonic history of the country,” Kellogg has since had his reputation buried by time and his name usurped in the culture by those corn flake boys up in Battle Creek. So, what do we really know about the founder of the Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Company?

Well, for one thing, he was neither a bandwagoner nor an ancillary character in the birth of the modern telecommunications industry. Milo Kellogg was right there from the beginning, working directly with Elisha Gray himself in the fledgling company that soon became Western Electric. He’d arrived in Chicago in 1870—six years before the first U.S. telephone patent was issued—as a 21 year-old fresh out of the University of Rochester. In the offices of Gray and Enos Barton, Kellogg quickly found his niche, tinkering with circuits and gradually changing the world. He was there—serving as manufacturing superintendent—when Gray famously went to war with Alexander Graham Bell for those vital phone patent rights in 1876, and he was still on the scene when Western Electric was subsequently purchased by the victorious Bell Company in 1882.

Kellogg even invented the switchboard that would become the Bell standard for years to come. But over the long haul, old rivalries died hard. The American Bell Telephone Company was, in many respects, the evil empire of this era, and Kellogg soon grew weary of his monopolistic overlords. By 1889, at the age of 40, he left Western Electric and boldly entered into the independent ranks, taking leadership roles with the Great Southern Telephone & Telegraph Co. and Chicago’s Central Union Telephone Co. His main focus, though, remained more on the research and science side than the business end of things. The only way to topple a tech giant like Bell, he keenly understood, was to out-tech them.

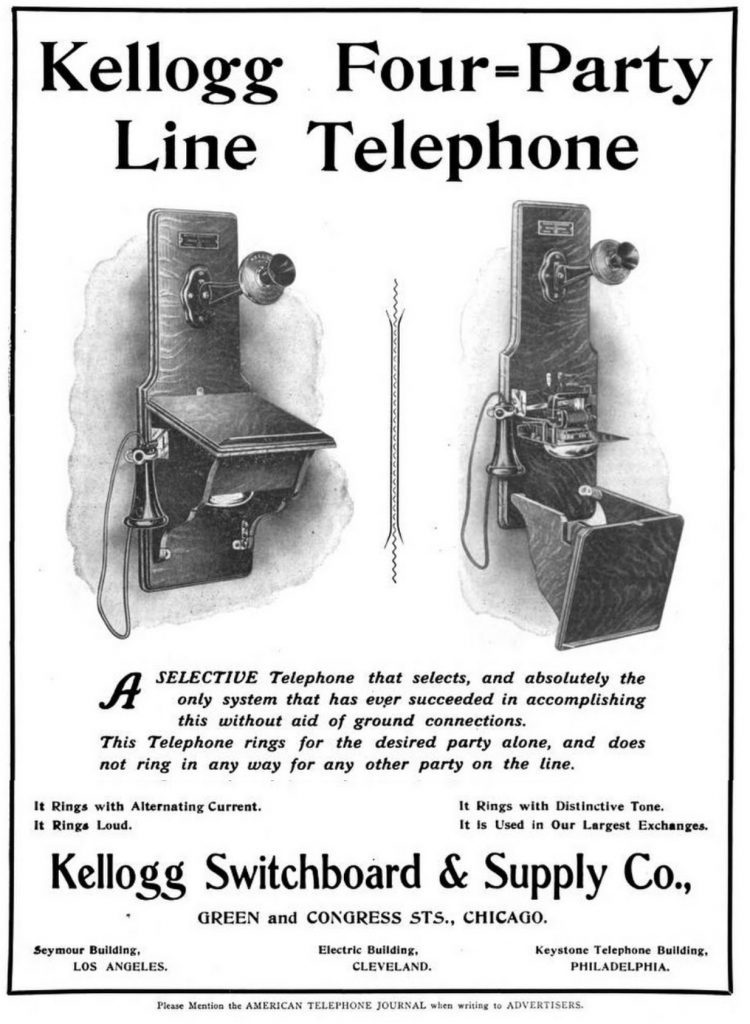

By the 1890s, Kellogg had become the undisputed master of the switchboard, and he’d helped countless independent operators obtain quality, long-lasting phone systems, particularly in small towns outside the iron grip of Bell. These efforts only increased when many of Bell’s original telephone patents began expiring in 1893.

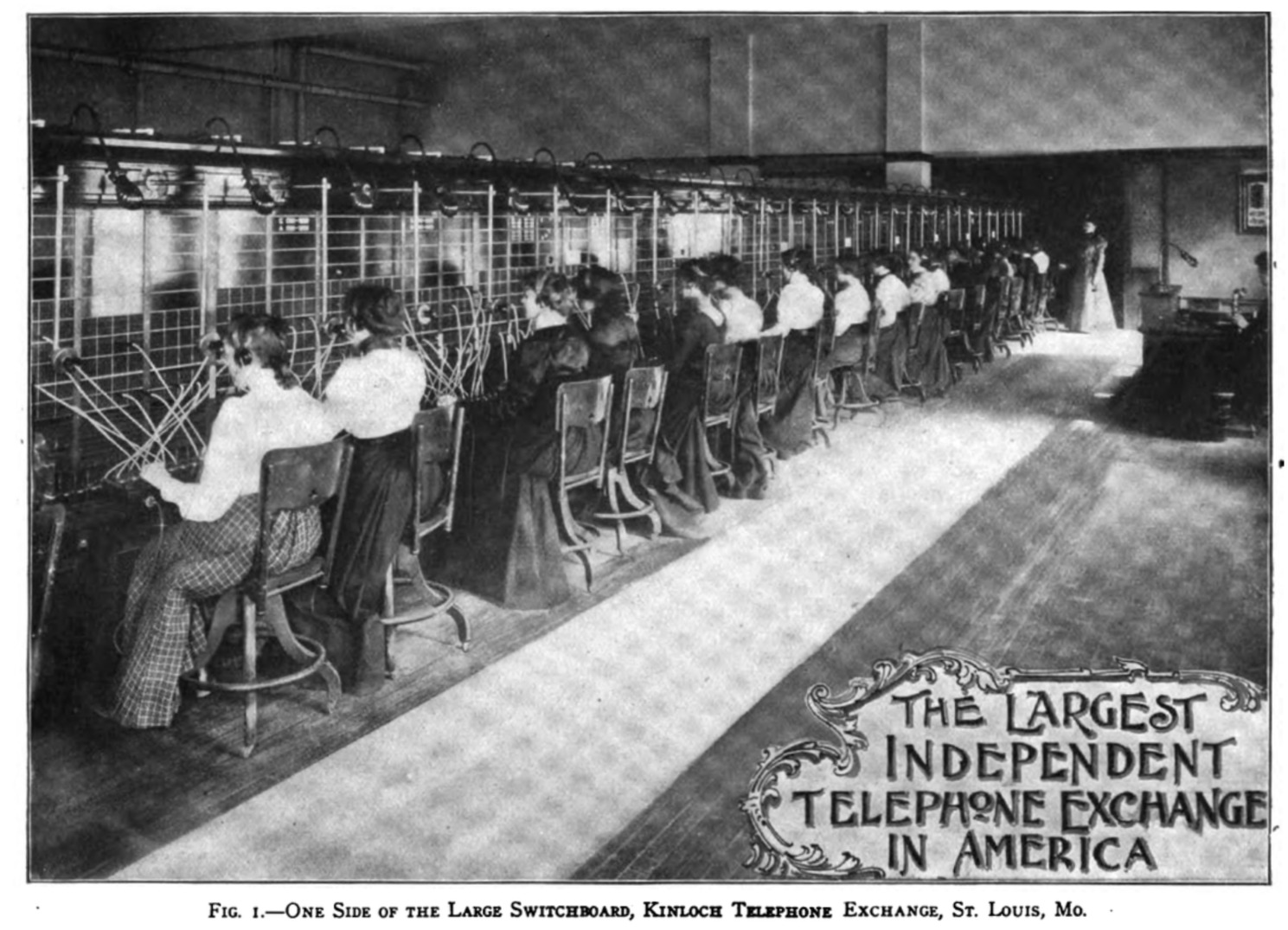

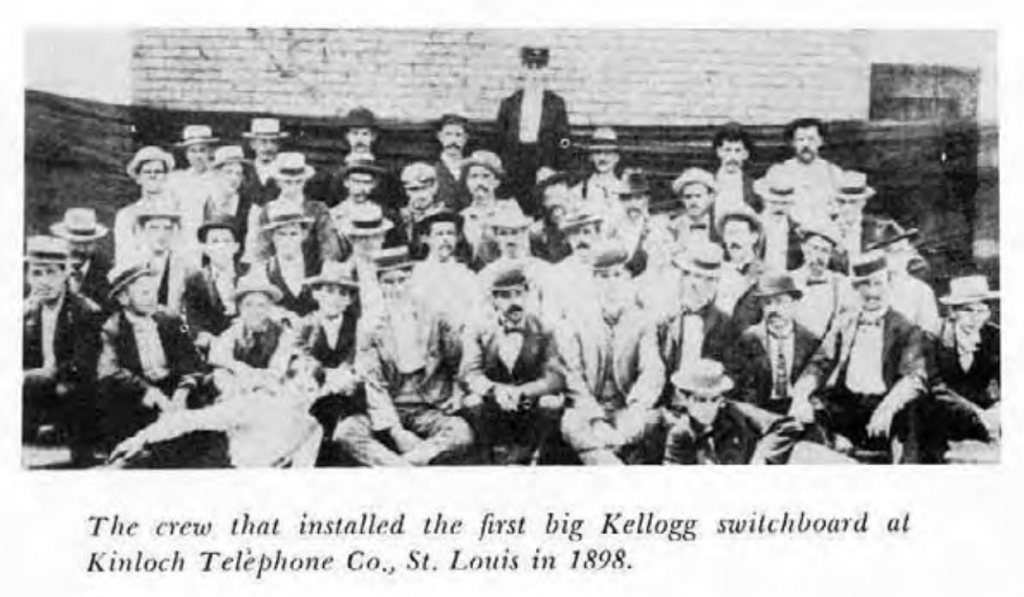

In the next few years, Milo Kellogg collected nearly 150 patents of his own, more than Gray and Bell collected in their entire careers, combined. He also marked a major shake-up in the industry when, in 1897, he helped the Kinloch Telephone Co. of St. Louis (then the fourth largest city in the country) produce an unprecedented, fully independent municipal phone exchange system—bashing through the former Bell monopoly in the city.

“The Kinloch system, which has been in course of construction since March 1, 1897, will be in operation within 30 days,” the St. Louis Dispatch reported on September, 4, 1898. “The feature in which the Kinloch is said to lead is in its improved switchboard. There is not another like it in the world, for the reason that it is has just been invented. Milo G. Kellogg of Chicago is the inventor. He also invented the switchboard in use by the Bell company.

“The chief point of superiority claimed for the new Kellogg switchboard is that it is all ‘central,’ doing away entirely with sub-stations, and thus avoiding the necessity of calling ‘Main,” ‘Sydney,’ etc.

“The Kinloch switchboard has a capacity of 20,000 telephones, the largest single switchboard in the world.

“Another feature that appeals to the public much more directly is the notable reduction in price. . . about half of former prevailing prices.”

The Kinloch project was basically the jumping off point for the new Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Company, then based out of an old schoolhouse in Highland Park, Illinois. Many had doubted whether a small upstart company could handle the production and installation of the St. Louis system, but once it went off without a hitch, similar contracts soon followed in Cleveland, Philadelphia, Buffalo, Los Angeles, and eventually overseas. The floodgates of the “indie” phone movement had opened.

[The original Kellogg factory, a converted schoolhouse in Highland Park, 1897]

[The original Kellogg factory, a converted schoolhouse in Highland Park, 1897]

“Milo Gifford Kellogg blazed the way for the independent telephone manufacturer,” the Chicago Engineer magazine later noted.

And for a perfectionist like Kellogg, blazing the way meant literally walking in the footsteps of his employees and making sure everything was being installed to his precise standards. One worker on the Kinloch system, Frank Taubeler, later shared his memories of his boss in the Golden Anniversary edition of the company newsletter, the Kellogg Messenger.

“He paced back and forth from one end of the room to the other,” Taubeler recalled. “A very imposing figure he was. There wasn’t a thing that escaped his eye. Mr. Kellogg was a thoroughly democratic individual and quickly won the confidence and respect of those who worked for him. I cannot but realize now what big moments those were for him—the biggest exchange in the United States and the first move in the Independent cause.”

The book Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, published 20 years after the Kinloch project, further hailed the Kellogg Company’s efforts as having “revolutionized the telephone industry.”

The book Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, published 20 years after the Kinloch project, further hailed the Kellogg Company’s efforts as having “revolutionized the telephone industry.”

“They were the first Independent telephones and switchboards, and have helped all telephone men to a knowledge of a better apparatus. It was the Kellogg Company who originated and made available economical party line systems for the small town telephone users, as well as the metropolitan. It was the Kellogg Company that, eighteen years ago, produced the Kellogg transmitter through which today, practically without change, millions of people are talking.”

So yeah, Milo Kellogg—a wiz kid, an inventor, a business leader, and, most importantly, a rebel. As with any story about rebels, however, this one will eventually include a chapter where the empire strikes back.

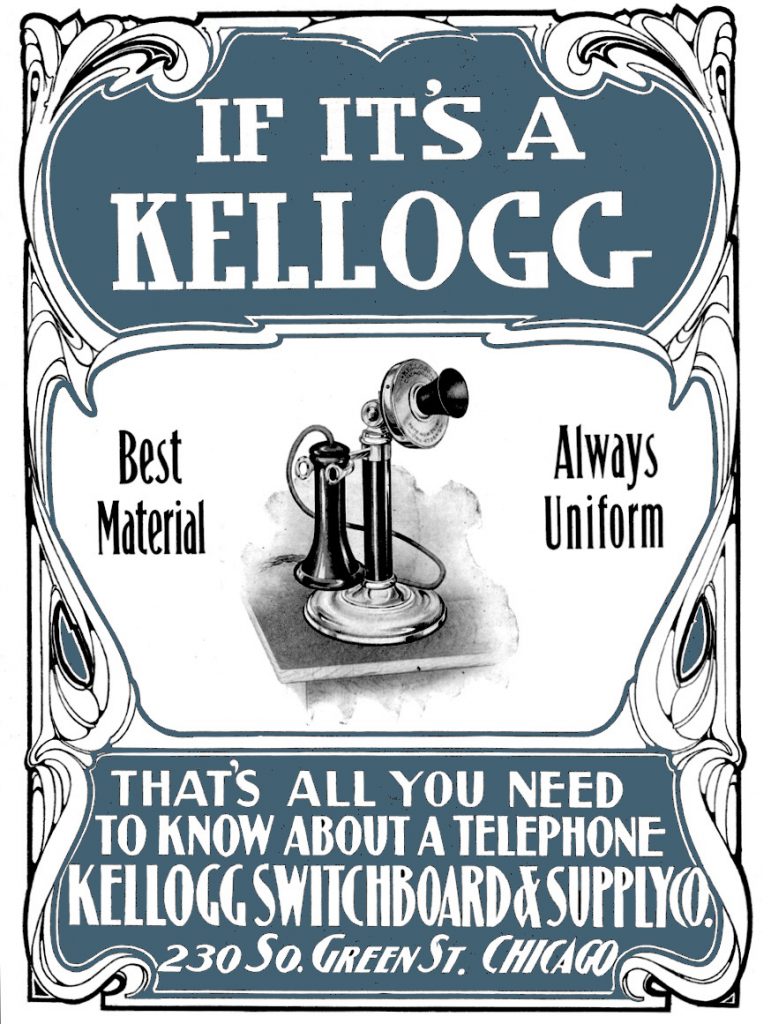

[1902 Kellogg advertisement from the American Telephone Journal]

[1902 Kellogg advertisement from the American Telephone Journal]

Inside the Factory

“The apparatus of the Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Company has gained an enviable reputation, and the concern was awarded the only gold medal on the merits of its ‘apparatus and systems’ by the Pan-American Exposition. The liberal policy of the company has attracted to its employ the best experts, experimenters, and skilled mechanics to be found in this country.”

—Profitable Advertising, January 1902

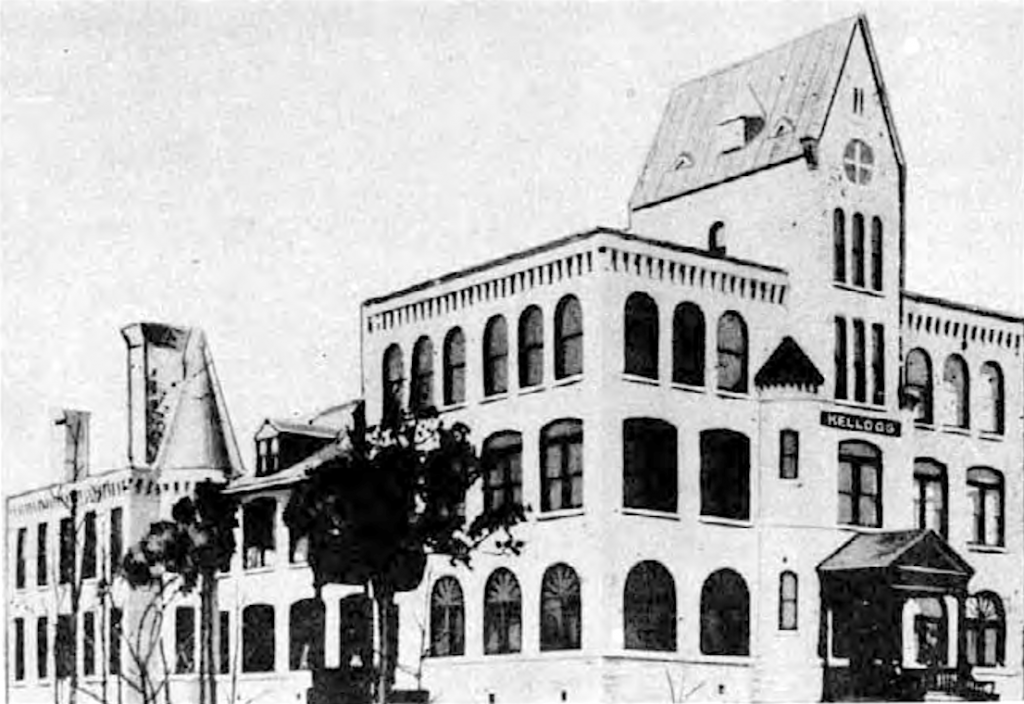

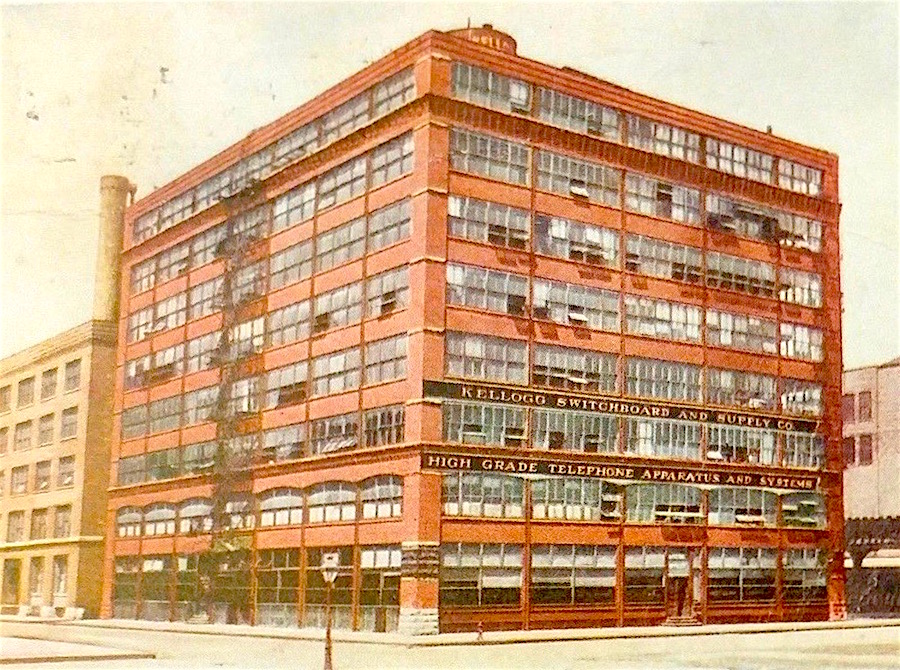

With business booming, Milo Kellogg was able to leave his makeshift schoolhouse factory behind in 1899, moving his business to a more modern plant downtown at 231 S. Green Street, at the corner of Congress Street (land now occupied by interstate 290). By the following year, the factory employed a whopping 800 workers: 624 men, 156 women, and 20 kids under the age of 16. As growth continued, two additional buildings were purchased on Peoria Street and Harrison Street.

[Factory at Green St. and Congress, Kellogg headquarters from 1899-1914]

[Factory at Green St. and Congress, Kellogg headquarters from 1899-1914]

In a 1903 article in the Magazine of Business, Kellogg purchasing agent Charles P. Belden laid out the organizational structure of the Kellogg operation; unrivaled in how it produced nearly every component of a modern telephone system.

“It will give some appreciation of the complexity of detail involved in this business to consider that 900 distinct types of finished apparatus are coded and manufactured. This apparatus is composed of units or ‘piece-parts’ to the number of 4,128 and it requires 4,034 different drawings or blueprints to guide the work of manufacturing.

“The company is divided into fifteen different departments, each in charge of a foreman. Through the application of a system the company aims to relieve these foremen of all detail work, and thus enable them to devote their entire time and energies where they belong—to production.”

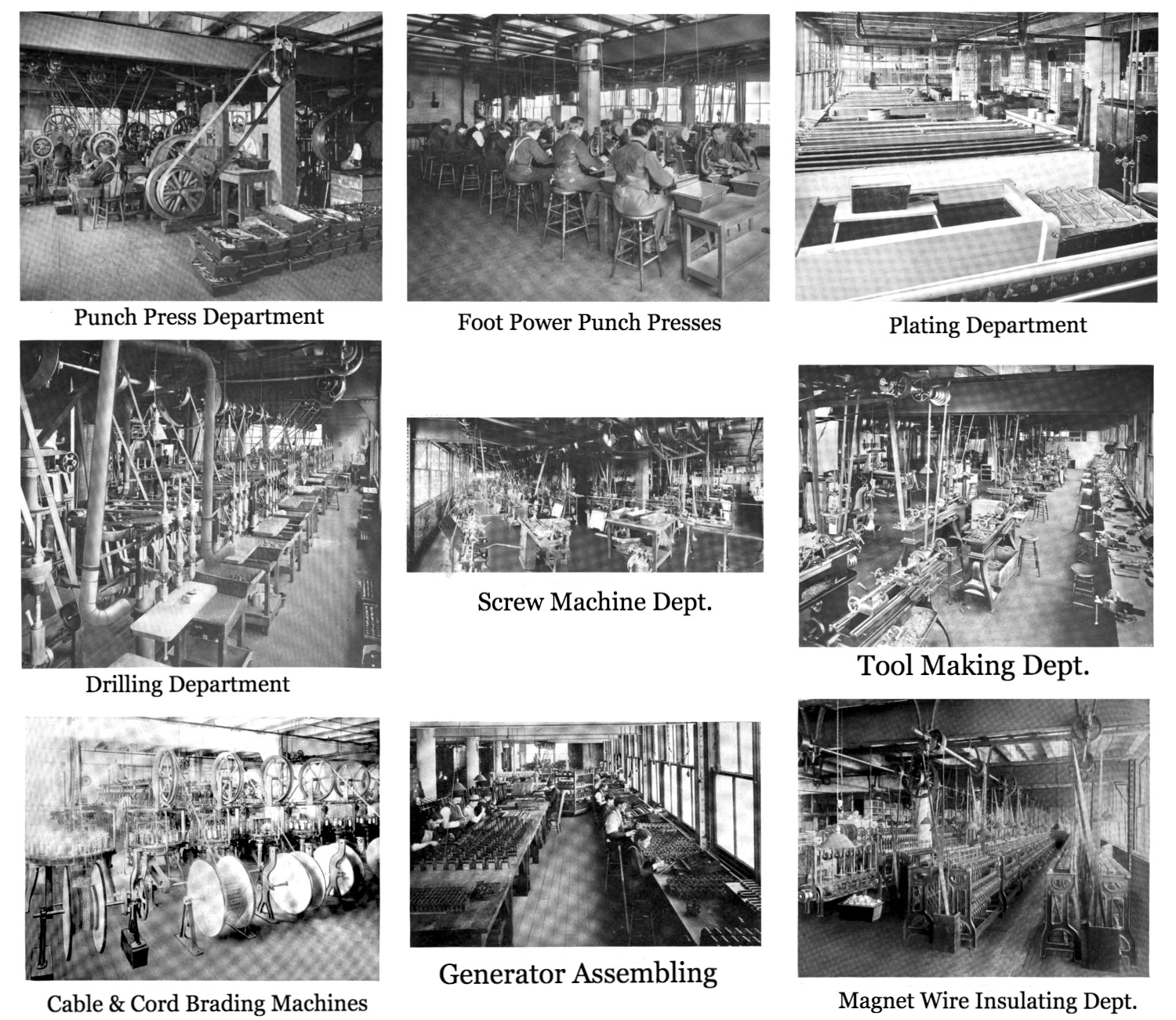

Various departments of the Kellogg factory on Green Street, 1904:

As shown above, Kellogg had full factory floors devoted to everything from punch press and screw machine departments to drilling, tool making, generator assembling, magnet wire insulating, and cord braiding.

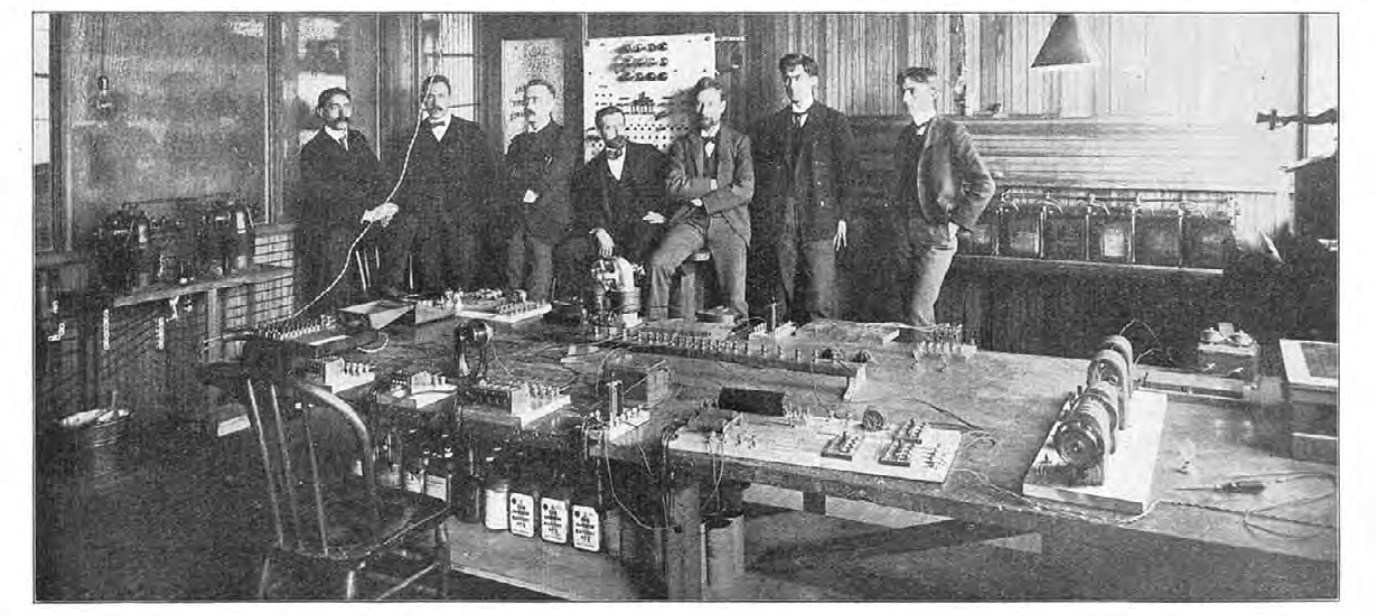

There was also, notably, a “laboratory and experimental” department, led by some of the foremost engineers in the industry, including MIT grad Francis W. Dunbar, Cornell grad Kempster B. Miller, former Bell chief electrician William W. Dean, and William Kaisling—a former cohort of Nikola Tesla. Another Cornell graduate, J.G. Brobeck, was in charge of the testing room, and every single apparatus produced in the Chicago factory supposedly had to get his final approval before shipping out.

[Inside the Kellogg research laboratory in 1901. From left: J. Henry Lendi, J.C. Neely, William W. Dean, Francis W. Dunbar, Kempster B. Miller, W.A. Taylor, and R.H. Manson]

[Inside the Kellogg research laboratory in 1901. From left: J. Henry Lendi, J.C. Neely, William W. Dean, Francis W. Dunbar, Kempster B. Miller, W.A. Taylor, and R.H. Manson]

“In the manufacture of telephones we have spared no pains in our methods to produce a telephone that should be lasting, efficient, and as near perfect as the finest time-piece,” claimed a 1902 Kellogg bulletin. “The demand for first-class instruments is becoming more universal, and it is this demand we wish to supply. In attempting to produce an instrument of the highest efficiency, everything has been done that skill, money or experience could do.

“It is the aim of the Kellogg Company to produce the finest telephone apparatus in the world; finest in design, finest in workmanship and finish, finest in quality, and, as a natural consequence, finest in results secured. In our line of telephone instruments we are confident that we have not fallen short of this purpose. The instruments will speak for themselves.”

The Empire Strikes Back

Right as his company was hitting its stride, Milo Kellogg fell ill toward the end of 1901. He was only 52, but the illness was severe enough that he was forced to retire to California and hand control of the business to his trusted brother-in-law, Wallace L. DeWolf. Over the next year, business continued on an upward trajectory, and when Milo subsequently made a surprise recovery and returned to Chicago, it seemed like everything was back in its right place. There was just one small problem. Good old Wallace, it turns out, had been a DeWolf in sheep’s clothing.

Back in January of 1902, just weeks after Milo Kellogg had stepped away from the business, DeWolf had done the unthinkable. Perhaps presuming that his brother-in-law would soon be dead anyway, he sold Milo’s entire interest in the Kellogg Company to the Bell-controlled Western Electric Company. This was a devious betrayal, somewhere between Lando and Judas, and its evil was only amplified by the fact that the deal was kept secret by all parties involved. No one at the Kellogg Company, including Milo himself, was informed of the sale, nor were any media outlets or customers.

Back in January of 1902, just weeks after Milo Kellogg had stepped away from the business, DeWolf had done the unthinkable. Perhaps presuming that his brother-in-law would soon be dead anyway, he sold Milo’s entire interest in the Kellogg Company to the Bell-controlled Western Electric Company. This was a devious betrayal, somewhere between Lando and Judas, and its evil was only amplified by the fact that the deal was kept secret by all parties involved. No one at the Kellogg Company, including Milo himself, was informed of the sale, nor were any media outlets or customers.

It was an incredible coup for Bell / AT&T / Western Electric—an imperial force seeking to re-take its telephone monopoly once and for all. Not only had they absorbed their greatest competitor, but—by keeping the acquisition under wraps—they now had the ability to directly influence an array of critical, pending legal cases, as well. For years, Bell had accused Milo Kellogg of patent infringement on certain components of his apparatus. Now, by owning his company, they could take those claims to court and put up an intentionally meager defense for the opposition. It’s like playing a video game when you’re holding both controllers. Bell was in position to thoroughly crush Kellogg and its legacy going forward.

What no one seemed to have counted on, however, was Milo Kellogg’s return from death’s door. In the summer of 1902, he finally learned of DeWolf’s betrayal, and took immediate action to try and resolve the situation. There were months of negotiation with his former co-worker at Western Electric, Enos Barton, to buy back the sold stock and re-take his rightful place as owner of Kellogg Switchboard & Supply. Perhaps if Elisha Gray hadn’t died a year prior, there could have been a friendlier resolution between the old telephone veterans. Instead, Barton cut off all negotiations.

What no one seemed to have counted on, however, was Milo Kellogg’s return from death’s door. In the summer of 1902, he finally learned of DeWolf’s betrayal, and took immediate action to try and resolve the situation. There were months of negotiation with his former co-worker at Western Electric, Enos Barton, to buy back the sold stock and re-take his rightful place as owner of Kellogg Switchboard & Supply. Perhaps if Elisha Gray hadn’t died a year prior, there could have been a friendlier resolution between the old telephone veterans. Instead, Barton cut off all negotiations.

By the spring of 1903, word of the tenuous situation had finally reached a wider audience, and the minority stockholders (aka, Milo loyalists) saw no alternative but to file suit against Bell, AT&T, and Western Electric. They believed Bell’s ultimate goal was to dissolve the Kellogg Company entirely, and they gained a court injunction to prevent such a move.

The minority owners of Kellogg released a statement on June 10, 1903, trying to ensure devoted customers that victory would be imminent.

“The suit brought by the minority stockholders of the Kellogg Company is not only in the interest of these stockholders, but is primarily in the interest of the customers of the Kellogg Company. The most eminent counsel available has been secured and the minority stockholders are confident that the Bell interest will be permanently barred from influencing the management of the Kellogg Company, and also that the sale of the stock will be nullified and Mr. Kellogg reinstated to active management.

“The present situation is one in which the customers of the Kellogg Company may now feel assured that their interests will be fully protected by the Kellogg Company under its old management.”

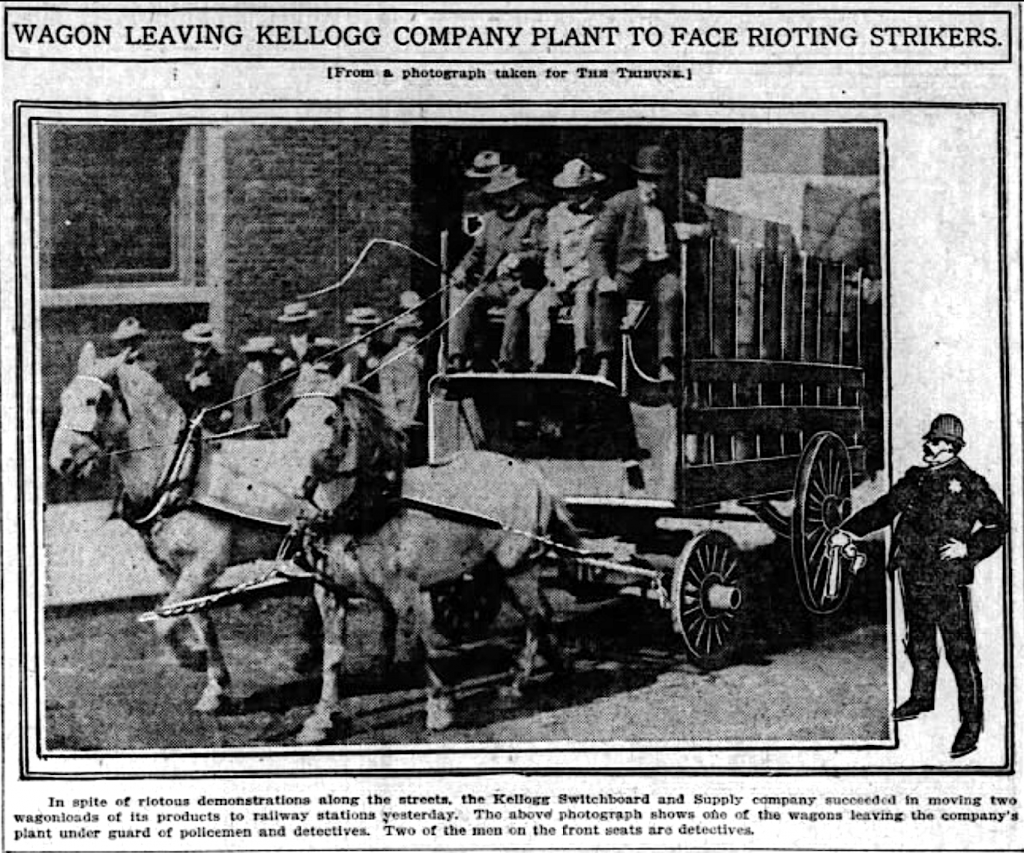

Unfortunately, it wouldn’t be quite so simple. The legal battle over gaining back control of the business and its patents would continue for another six years, taking a major toll on everyone involved. In the meantime, having lost power over its own operation, Kellogg quickly lost favor with many of its workers, as well. In 1903, the same year as the first lawsuit, a massive strike organized by the Brass Molders Union Local 83 and International Brotherhood of Teamsters turned ugly. Kellogg’s new masters in the Bell Telephone Trust refused to negotiate with the striking workers, and frustrated picketers soon turned to violence.

[Striking workers gather outside the Kellogg plant, 1903]

Through much of the summer of ’03, the scenes outside the Green Street factory made national news. Several people were killed as fights between union men, non-union teamsters, and police officers raged on. On July 17, the Quad-City Times in Davenport, Iowa, reported of a crowd of 500 men and boys outside the factory—a so-called “lawless element.”

“A crazed mob last evening wrecked the lower floor of the building of the Kellogg Switchboard and Supply company, West Congress and Green streets, around which strike and riot have been eddying for several days. The 17 plate-glass windows on the first floors were smashed to pieces with stones, and the infuriated rioters did not desist until most of the smaller windows in the second and third floors were broken.”

The Chicago Tribune later deemed it the most violent labor uprising in nearly a decade. In the end, though, it was also a fruitless one. The Bell-controlled Kellogg Company simply eliminated and replaced 90% of its workforce in the end. How things might have played out with an independent Milo Kellogg still in power, we’ll never know.

The Chicago Tribune later deemed it the most violent labor uprising in nearly a decade. In the end, though, it was also a fruitless one. The Bell-controlled Kellogg Company simply eliminated and replaced 90% of its workforce in the end. How things might have played out with an independent Milo Kellogg still in power, we’ll never know.

By the time the Illinois Supreme Court finally did grant full majority ownership of the company back to Milo in February of 1909, there was little time left for him to enjoy it. He died later that fall at the age of 60, and his son Leroy D. Kellogg took the reins. Wallace DeWolf, incidentally, went on to pursue his life’s passion for art, eventually having some of his own paintings and etchings exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Kellogg Switchboard & Supply would remain an independent business once more right up until its sale roughly four decades later.

Innovative to the End

After the extreme tumult of those early years, a sense of stability returned in the 1910s. Milo’s sons Leroy and James G. Kellogg carried on their father’s vision, and the company remained at the forefront of the industry—even if outpacing AT&T and Western Electric was never quite in the cards.

After the extreme tumult of those early years, a sense of stability returned in the 1910s. Milo’s sons Leroy and James G. Kellogg carried on their father’s vision, and the company remained at the forefront of the industry—even if outpacing AT&T and Western Electric was never quite in the cards.

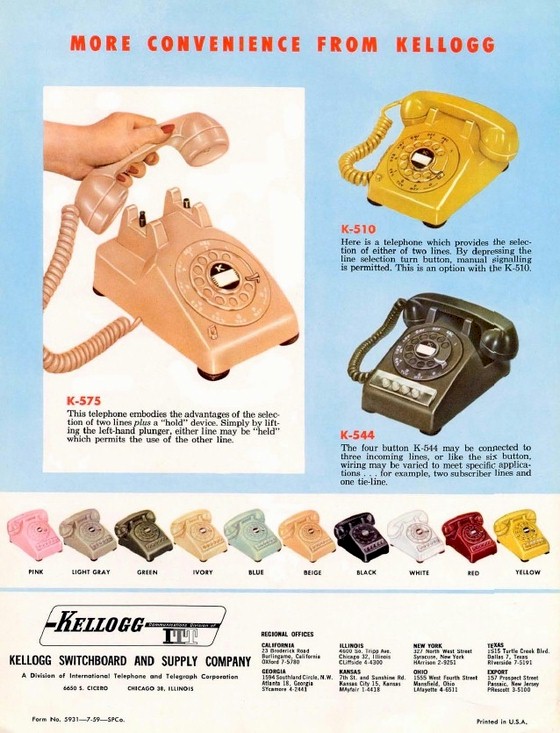

From World War I through World War II, Kellogg remained tied to its roots as a provider to independent phone companies—the largest such manufacturer in the world. They were regarded as pioneers in many avenues, having introduced the first lamp signal boards, the first cradle style phones in the U.S. (the Grab-A-Phone), and later, the first non-positional transmitter. The company also rebuilt its reputation literally from the ground up, opening up a new thirteen-acre mega-plant at 1020-1070 West Adams Street in 1914, where greater concern was shown for the demands of employees and customers, alike.

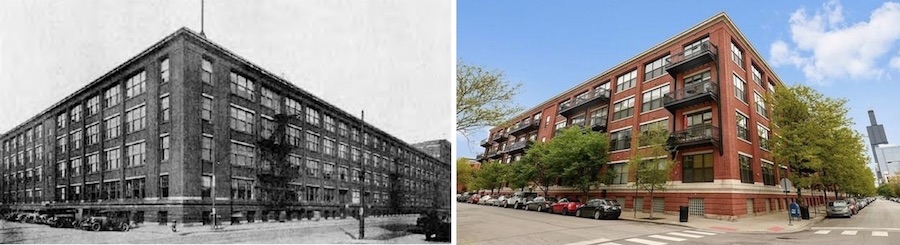

[The former Kellogg plant at 1060 W. Adams St., 1920s vs. present day (turned into condos)]

[The former Kellogg plant at 1060 W. Adams St., 1920s vs. present day (turned into condos)]

In 1926, a sales bulletin invited independent telephone men to come to Chicago and tour the company grounds to see firsthand what they’d be getting with Kellogg.

“The engineers would be glad to talk over your problems and tell you some of the things Kellogg is accomplishing in the telephone development field. The other departments would gladly discuss your telephone and outside plant requirements. Everywhere in the office you would find a friendliness and willingness to help you with your problems. That is the Kellogg spirit.

“Then we would go into the plant. You would see dozens of screw machines turning out small parts automatically. You would see batteries of presses punching out other parts and forming some of the larger ones. You would see the finishing and plating of all kinds of parts. You would see the presses molding the receiver shells and caps. Each department would be making something, no matter how small, which would become a part of your equipment.

[pictured below: Longtime Kellogg cabinet maker Frank Pavelec in 1959]

“You would probably be impressed by the close inspections made of all operations. Everything must come up to the Kellogg standard or it is cast aside.

“You would probably be impressed by the close inspections made of all operations. Everything must come up to the Kellogg standard or it is cast aside.

“The assembling department would be restful after the whirr and roar of the other departments. Here you would see the carefully trained artisans constructing before your eyes the switchboard itself, their skilled hands rapidly putting together the various parts and assemblies. You would marvel at the amount of material that goes into the switchboard in so small a space, still leaving plenty of room for easy access. You would leave this department with a feeling of confidence and an understanding as to why Kellogg switchboards always make good.”

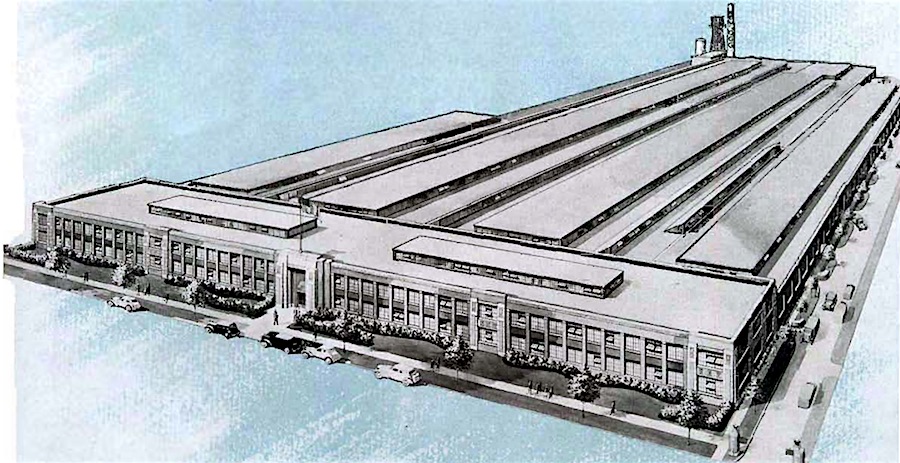

Like most other businesses, Kellogg had to re-calibrate a bit in the 1930s, and not everyone came through the challenges unscathed. Leroy Kellogg, for one, took his own life in 1933—having already departed from the leadership of the business years earlier and fallen into financial ruin. His brother James G. and nephew James H. remained deeply involved with the company, however, and were able to both cut costs and advance production by moving into a more modern, single-story factory in the Clearing Industrial District in 1938 (at 6650 S. Cicero Ave.). In the process, Kellogg’s 17 departments were streamlined into six.

[Kellogg’s Clearing District plant at 6650 S. Cicero Ave., its HQ from 1938-62]

As they had in the first World War, Kellogg devoted most of its resources to the U.S. government during World War II—making field sets, microphones, telephones, receivers, and switchboards for the army and navy. At least 800 of the company’s own employees, from across the country, also headed to the battlefront.

When the war was over, and the Chicago workforce ballooned back to 1,000, Kellogg claimed there were over 31 million “K” branded telephone sets in the U.S. alone. The Cicero Avenue plant was expanded by another 50,000 square feet in 1946, and with third-generation president James H. Kellogg now in charge, production jumped 3x in the first months of 1947 compared with the year prior.

[Kellogg employee George Ernst (left), who joined the milling department under Milo Kellogg in 1898, presents a gold telephone to third generation president James H. Kellogg, as part of the company’s Golden Anniversary in 1947]

[Kellogg employee George Ernst (left), who joined the milling department under Milo Kellogg in 1898, presents a gold telephone to third generation president James H. Kellogg, as part of the company’s Golden Anniversary in 1947]

The men and women who would have been building the Red Bar 1000 Masterphones like the one in our collection would have also been enjoying perks their early predecessors in the labor movement never could have imagined—paid vacations and holidays, a cafeteria with an actual chef, group insurance programs, retirement plans, and a first aid and safety council to handle on-the-job mishaps.

After James H. Kellogg sold off the majority stock to ITT in the early 1950s, the white flag was effectively raised on the old war for independence. Even so, the new company remained a Chicago fixture for one more decade. Along with the 400,000 sq. ft. Cicero plant, there was a large systems engineering factory at 500 N. Pulaski and smaller facilities at 6000 W. 51st St. and 5959 S. Harlem Ave.

After James H. Kellogg sold off the majority stock to ITT in the early 1950s, the white flag was effectively raised on the old war for independence. Even so, the new company remained a Chicago fixture for one more decade. Along with the 400,000 sq. ft. Cicero plant, there was a large systems engineering factory at 500 N. Pulaski and smaller facilities at 6000 W. 51st St. and 5959 S. Harlem Ave.

Several generations have now passed since Kellogg’s last Chicago days, but the company is worthy of remembrance as a hefty branch in the evolutionary tree of global communication. Obviously, one should always hesitate to judge the true philosophies of a business by the content of its ad copy, but if you read enough material from the Kellogg archives, it starts to feel like its operators really did see the growth of telecommunications as a noble calling, rather than just a good line of work.

“A completed telephone at best is only a combination of wood, steel and copper,” read the intro to the May 1921 edition of the Kellogg newsletter, Telephone Facts. “A thousand completed switchboards, while representing vast mental and physical accomplishments, are in themselves only examples of engineering design, mechanical perfection and high-grade workmanship.

“But take two telephones and connect them through a switchboard, and we have an altogether different proposition. Then we have something much more than apparatus, because life itself is involved.”

Sources:

“A History of the Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Company” + Catalog Scans from TelephoneCollectors.info

“Impressive Gains: That’s Kellogg Story Since 1952” – Chicago Tribune, June 7, 1960

Telephone Facts, Vol. II, No. 5, May 1921

“The Kellogg Type 1000 Masterphone,” by Roger Conklin, Singing Wires, June 2004

“A System for Purchasing,” by Charles P. Belden, The Magazine of Business, October 1903

“Telephone Systems” – St. Louis Dispatch, September 4, 1898

Kellogg Messenger: Golden Anniversary Edition, April 1947

“Laboratory and Experimental Work at the Kellogg Telephone Factory” – Western Electrician, Jan 5, 1901

Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Co. Bulletin No. 13 and 14, 1904

Profitable Advertising, January 1902

“Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Company” – Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, Vol. 3, 1918

Kellogg Masterphone Catalog: 1000 Series, 1948

Masterphone 1000 Series brochure, 1947

“The Chicago Mob” – Quad-City Times, July 17, 1903

Archived Reader Comments:

“My husband’s grandfather, Joseph Raskey worked on Adams as a machinist in the early 1900’s, He died at a young age (49) and the company gave his widow a gold watch. They seemed to really care about their employees.” —Linda Raskey, 2018

“This is wonderful. My mother worked at Kellogg Switchboard in the summer of 1944 when it was a defense factory. She made a piece that went into ship radios. Though jobs were frozen then, she received a medical excuse for dismissal due to her rheumatoid arthritis. She spoke of her time at here with great pride. Thanks for this!” —Lynn Burgess, 2017

I owned a Kellogg switchboard Desk with serial number 20044 excellent condition call if interested

I am in need of a number holder for my Kellogg Candlestick. Phil 713-907-2407

I’m researching the date of manufacture for a Kellogg Switchboard & Supply- serial # 13734 ?

Is there a publication that would indicate year of manufactured to serial number?

Hello, I have a pair (2) Aristocrat model K-30HB/3 car telephone units. I don’t have the actual handset, but the tube filled trans/rx units. Are they worth listing as is, or best to strip for parts? Thanks!

I have Two Kellogg Switchboard Switch Boxes – 1 is all oak dove tail with glass face and a big one is on a Slate Slab with mounting holes and dove tail oak case with glass front. 4 switches inside. Best offer.

I have a vintage (I assume) Kellogg Emergency Bell and have no information about it and can’t seem to find ant so far. The cover is about 3″ in diameter with a bell of about 1 3/4″ to 2″ maybe and the “knocker” is about the size of an old muskets ball maybe 0.50″. It says Kellogg Emergency U.S.A. on the cover and inside on the back of the bell assembly there are two stamps, C-1 & L.S.J.W. however it could be three stamps since the is a small space between the S. & J. Any information would really be appreciated.

This is in response of Risk Jacobs’ post April 28, 2023.

Rick did you ever find more about the 177-c horn and head set?

It sounds like it was used by an operator

I have a Kellogg 177-c horn which you can hang around your neck and a headset.

Can somebody tells me from what year it was and where it was used for ?

I have a Candlestick Desk Set phone with a separate ringer box. I want to restore it

to the original condition. I am looking for parts, mainly the receiver cord, and the candlestick to ringer box cord.

I am also looking for the Circuit diagram 21188-C

I have an antique (wooden w/crank) Kellogg Pay Phone. It has to be one of the first pay phones. I’m looking to sell at a reasonable price if you know anyone who might be interested. I have a lot of antique telephone stuff too!!

Edward, I hope this Kellogg catalog helped. There are other Kellogg phone catalogs from different years where I found that catalog #6. You can find the other catalogs at the following link: https://www.telephonecollectors.info/

I have an old Kellogg Magneto(generator), from an old wall phone.

It has a plate on the front of it that says:

KELLOGG

..below that it says:

CHICAGO-U.S.A.

There are three screws holding the plate on.

Above the three screws is the number 22 stamped.

There are no other numbers or letters on this unit.

Is there a way to find out what year,or era,this was made in ?

Thanks so much for any input.

I found a sort of horn from the kellogs switchboard and supply company

But I can not find it anywhere on the net

maybe you can help me out

It works on 12 volts and it sounds like the A ford OOGAH claxon/horn

I saw similar horns that were used for factory hal shipyard dockyards etc so you could here the phone ring on the yard etc

I realy would like to know what I have

Thanks Ton

Kellogg also manufactured “capacitors” which were blocks filled with tar that contained electrolytic capacitors (also called condensers) for the Zenith Radio Corp back in 1928. It was Zenith part number 22-41. I’m trying to ascertain the values of the capacitors as I am restoring a Zenith console radio model 39-A. Can you help!

Your example of the 1070 Masterphone was actually manufactured in April 1952, it has a date stamp on the bottom.

The Kellogg 1000 series was actually announced in 1945, not in 1947, per the April 1947 anniversary issue of Kellogg Messenger. Also, the magazine “Telephony” carried an advertisement for the Masterphone 1000 in March 1945. Various examples of 1000 type Masterphones have been found that are dated in 1946. Major marketing campaigns appear to have starting in 1947, though.

I appreciate the insight, Karl. Would it be possible for you to email an image of that 1945 Telephony advertisement to contact@madeinchicagomuseum.com ? I couldn’t find any reference that early, but it certainly makes sense that it would have been in a pre-production of sorts for a while before the big rollout. Also, are you determining the 1952 date of our phone from the “1070 SB” stamp or the smaller stamp (I couldn’t really even make out the second one). Either way, do let me know. I noted the phone was “circa” 1947 but will happily update it to the exact date of its specific production if the stamp suggests it.