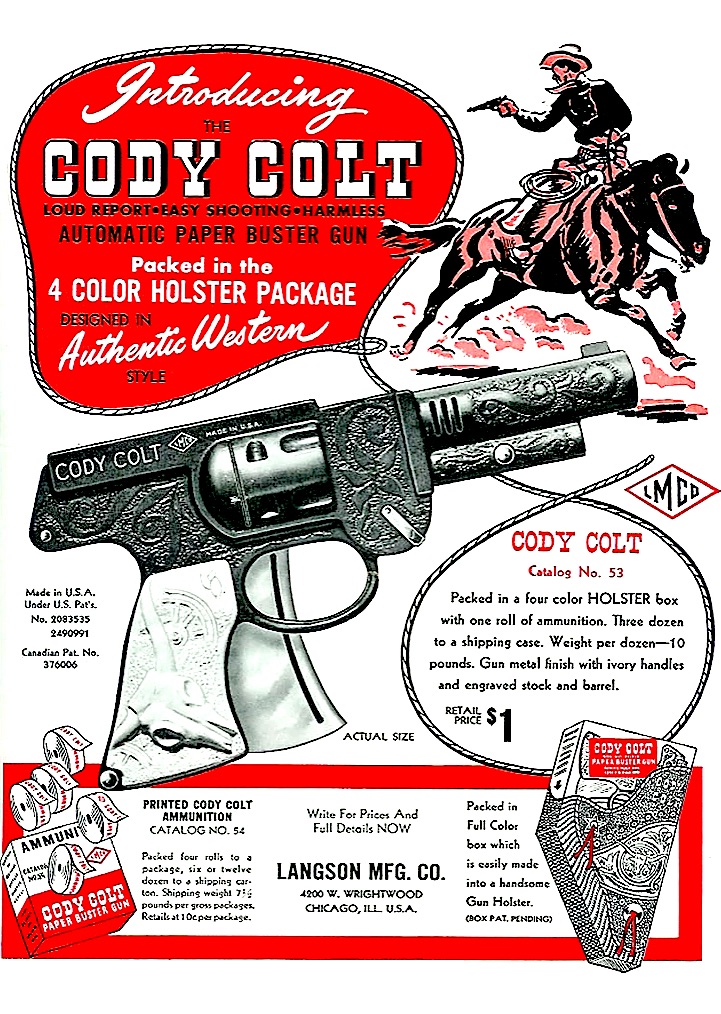

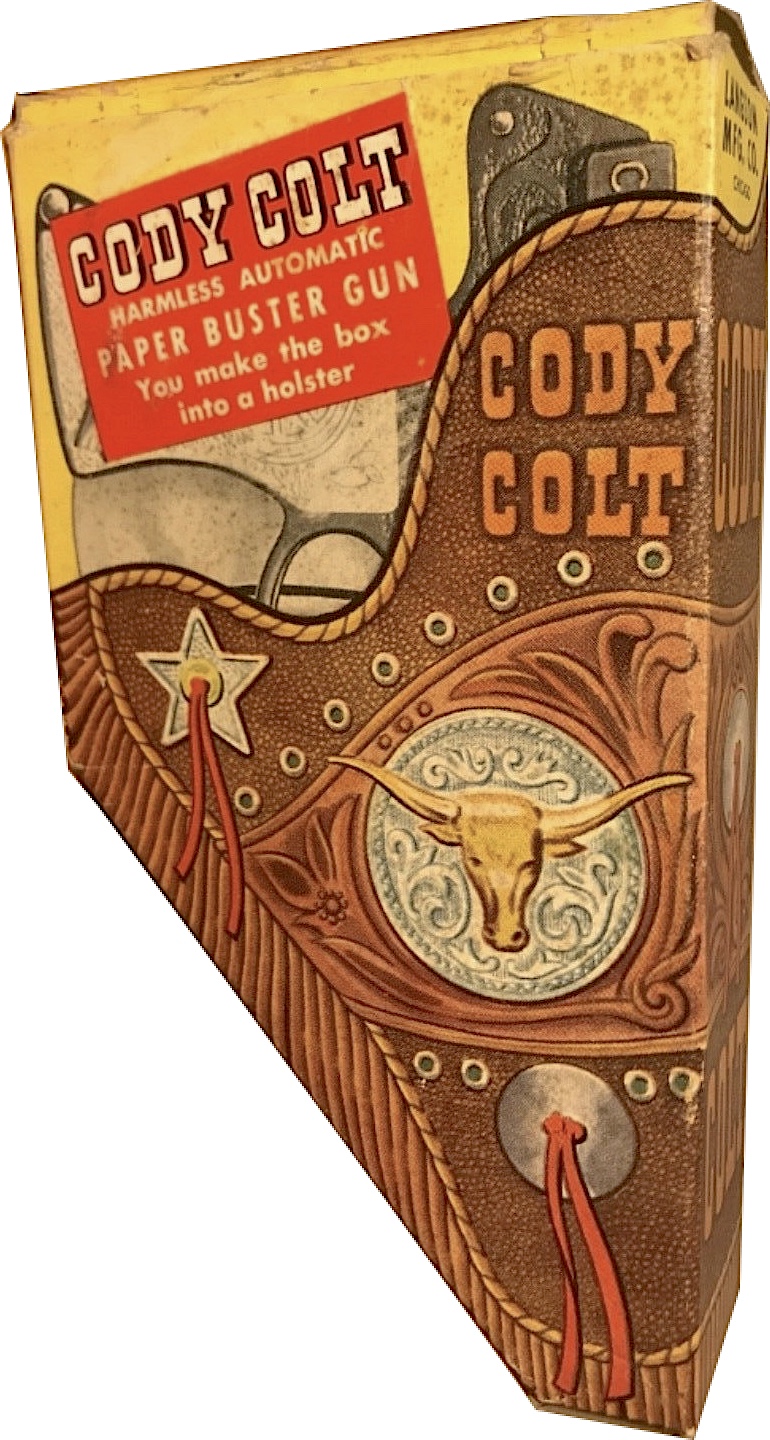

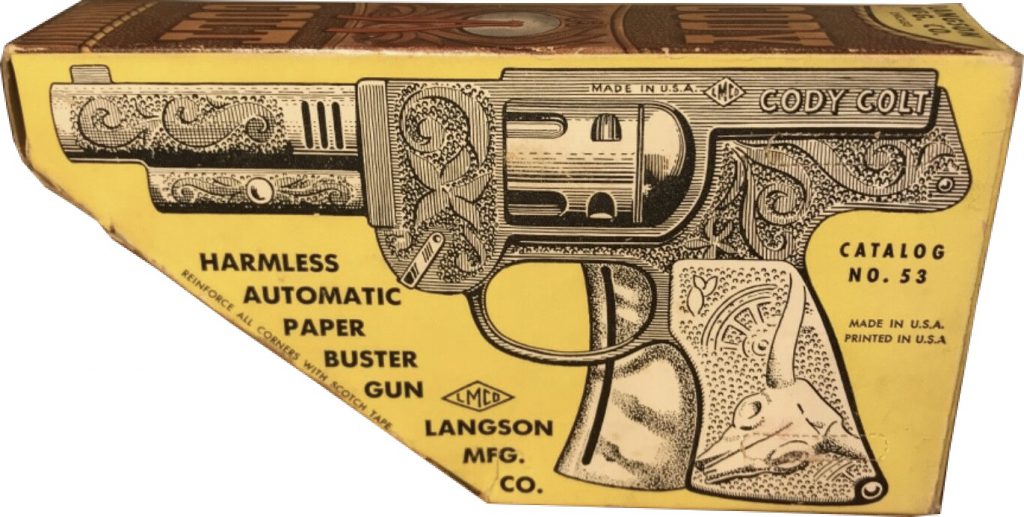

Museum Artifact: LMCO Cody Colt Paper Buster Gun, 1950s

Made By: Langson MFG Co., 4200 W. Wrightwood Ave., Chicago, IL [Hermosa / Belmont Gardens]

It might have the look and sound of a typical cowboy-themed cap gun from the 1950s, but there’s something a tad different about the LMCO “Cody Colt”—something that helps distinguish Chicago’s Langson Manufacturing Company from most of the competing toy gun manufacturers of its era.

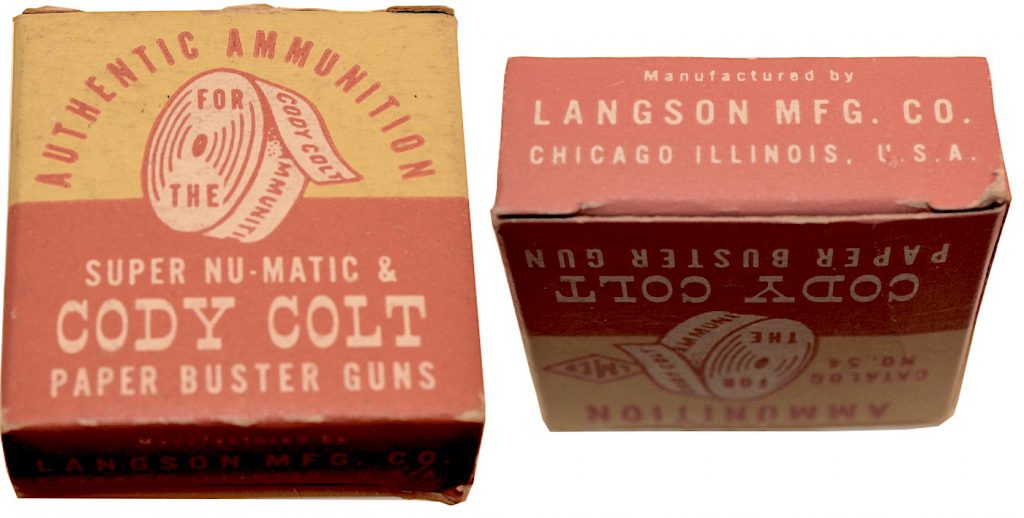

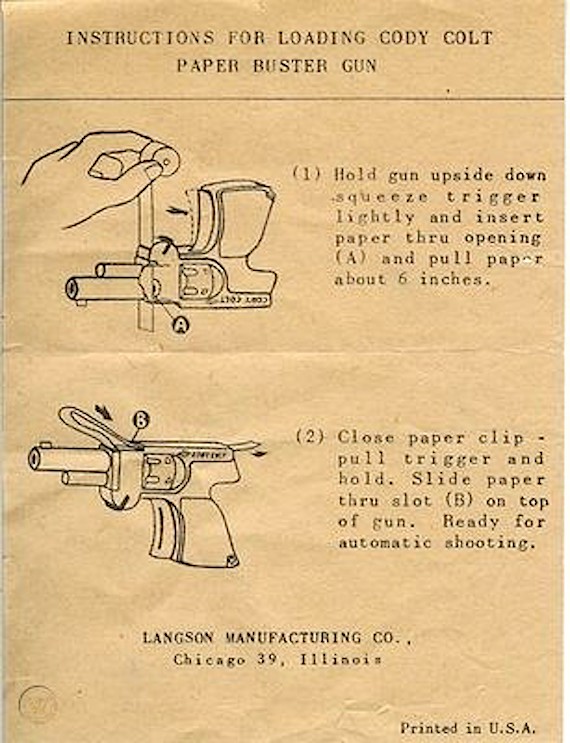

Utilizing a mechanism developed and continuously refined by company founder Otto A. Langos, the Cody Colt—like all the other guns, miniature cannons, and torpedoes LMCO produced from the 1930s to the ‘60s—was known more specifically as a “paper buster” or “paper popper.” This means that it relied on pneumatic power (i.e. condensed air pressure) to blast tiny holes through a rotating roll of paper ribbon; creating a loud, pleasing “pop” with each pull of the trigger.

Utilizing a mechanism developed and continuously refined by company founder Otto A. Langos, the Cody Colt—like all the other guns, miniature cannons, and torpedoes LMCO produced from the 1930s to the ‘60s—was known more specifically as a “paper buster” or “paper popper.” This means that it relied on pneumatic power (i.e. condensed air pressure) to blast tiny holes through a rotating roll of paper ribbon; creating a loud, pleasing “pop” with each pull of the trigger.

By stark contrast, most traditional children’s cap guns worked by literally firing off a genuine explosive charge; usually powered by a “gunpowder cap” with a mix of sulfur, potassium perchlorate and antimony sulfide. This tiny enclosed firecracker not only made the desired “bang,” but also sent a bad-ass billow of smoke from the end of the barrel every time little Jimmy “shot” his buddies at point blank range. . . . In essence, if you replaced a standard kid’s cap gun with an actual vintage pistol loaded with blanks, the difference would only be nominal—perhaps explaining why many street gangs wound up retro-fitting cheap toy guns into fully functional firearms (or “zip guns”).

All things considered, it’s easy to see why LMCO’s comparatively “harmless,” non-explosive paper busters appealed to safety-minded parents. The bigger achievement, really, was reducing the danger factor without boring the kids. Langson managed this by following the eternal golden rule of toy weaponry: the more realistic looking, the better. During World War II, in particular, when rationing prevented cap gun makers from packing their usual gunpowder charges, it was the paper busters that thrived—helping to save countless backyard games of “Cowboys & Indians,” “Cops and Robbers,” and “Martian Invaders,” not to mention all those imaginary Hitler assassinations.

The King of the Paper Busters

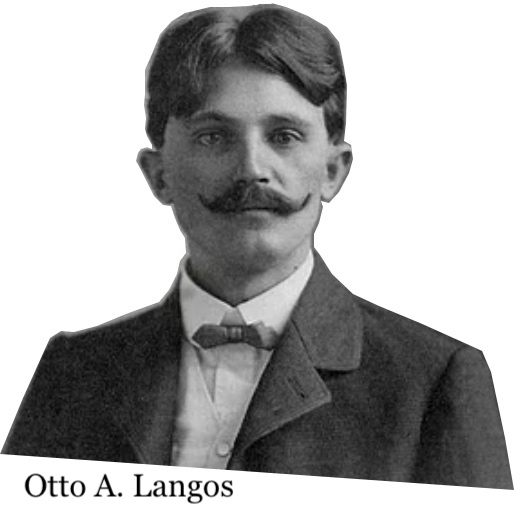

Otto Albert Langos was born in Hungary in 1877 and didn’t come to the States until 1902, at the age of 25. So, unlike many immigrant business owners who emigrated as children and adapted to the new language/culture at a relatively steady pace, Otto had a slightly more imposing road ahead of him if he wanted to provide for his wife Magdalena and their growing family.

According to his great-grandson Bill Cermak, Langos had been a music teacher back in Budapest, specializing in the under-appreciated string instrument known as the zither. This career hadn’t done much for Otto’s bank account or career prospects—hence the move across the pond. But the technical skill might have proven useful as he started his new life as a tool and die maker and machinist in America.

According to his great-grandson Bill Cermak, Langos had been a music teacher back in Budapest, specializing in the under-appreciated string instrument known as the zither. This career hadn’t done much for Otto’s bank account or career prospects—hence the move across the pond. But the technical skill might have proven useful as he started his new life as a tool and die maker and machinist in America.

Less than two years after his arrival, in fact—while living in Alliance, Ohio—Langos applied for his very first patent, teaming with a George Zimmermann of Pittsburgh to develop a new type of railway switch. It’s a complete mystery how a fresh-off-the-boat, Hungarian zither teacher gained any expertise in railroad engineering, but it’s our first evidence of the man’s wide-ranging ability and ambitions.

Leaving Ohio in 1905, Langos next became part of one of the largest influxes of Hungarian immigrants into Chicago, with the local population increasing from 7,463 in 1900 to 37,990 by 1910, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago. The Langos family settled in the Portage Park neighborhood, first at 4920 W. Byron Street, then into their long term residence at 5233 W. Warner Avenue.

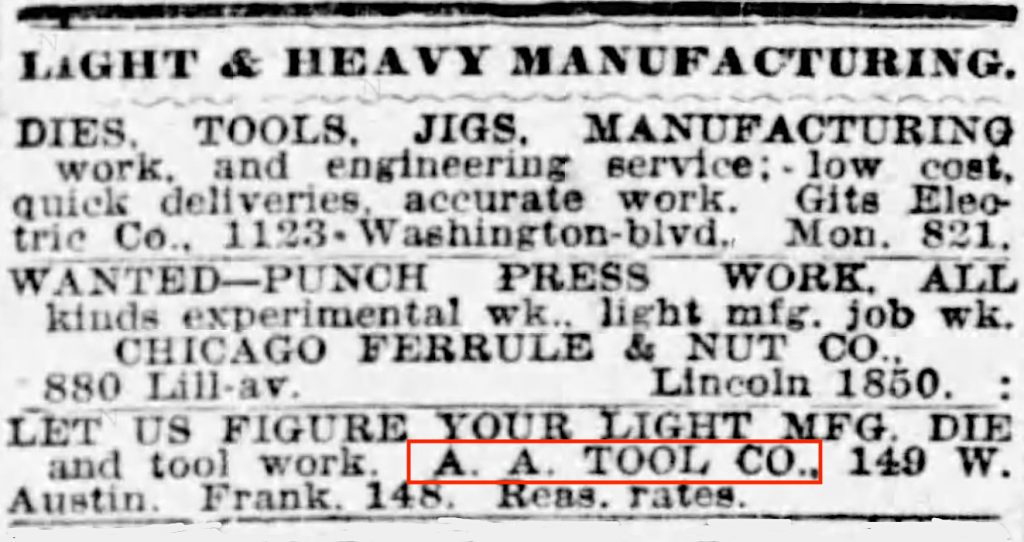

[A Tribune advertisement from 1917 shows Otto Langos’s employer, the A. A. Tool Co., offering its expertise in “light mfg. die and tool work.” As a weird coincidence, the ad directly above it is for the Chicago Ferrule & Nut Co., whose plant at 880 Lill Ave. would become the first Langson MFG. headquarters over a decade later]

[A Tribune advertisement from 1917 shows Otto Langos’s employer, the A. A. Tool Co., offering its expertise in “light mfg. die and tool work.” As a weird coincidence, the ad directly above it is for the Chicago Ferrule & Nut Co., whose plant at 880 Lill Ave. would become the first Langson MFG. headquarters over a decade later]

Otto found work as a tool maker in the city, employed by the A. A. Tool Co. at 149 West Austin Avenue [now Hubbard Street]. Here, he tried his best to scrape together enough scratch to feed seven kids, leaving any additional expenditures—like buying one of them a nice toy—as a rare luxury. Such limitations, however, could have provided the impetus for a mechanically crafty Mr. Langos to try something in the DIY department—setting the stage for an unlikely lifelong passion.

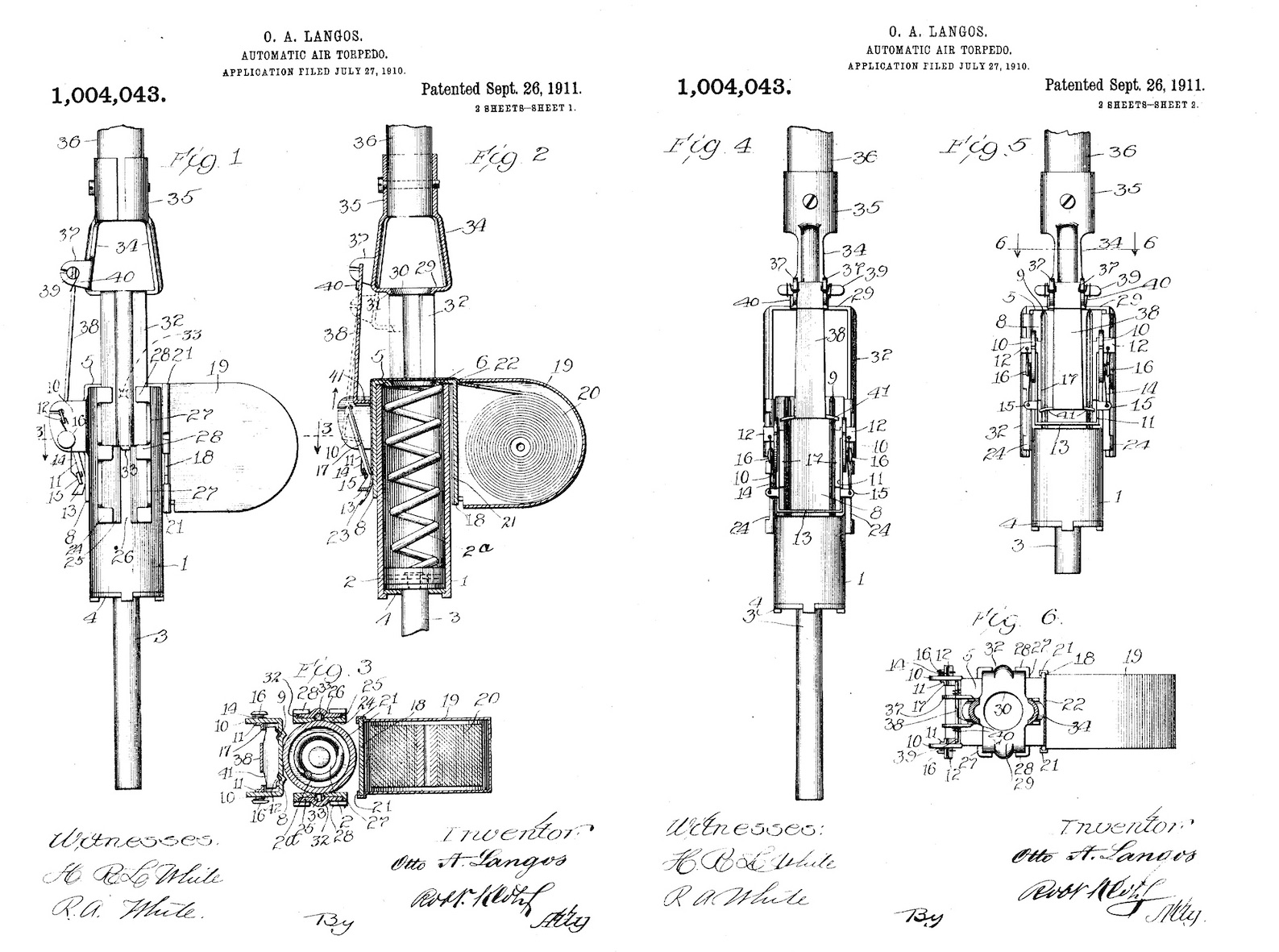

In 1910, at the of 33, Langos applied for a patent on his very first noisemaker toy invention—an “Automatic Air Torpedo” that he described as a “new and useful improvement” on similar paper-powered firing toys of the recent past. The goal was to “provide a toy capable of producing loud explosions or reports, and in which all elements of danger from the explosion have been eliminated.” The design was recognized on September 26, 1911, as U.S. patent No. 1,004,043, and it would be the first of 24 patents Langos would acquire over the next 40 years—15 of them related to paper buster toys.

[Otto Langos’ first paper buster patent, the 1911 “Automatic Air Torpedo”]

[Otto Langos’ first paper buster patent, the 1911 “Automatic Air Torpedo”]

The Name is Langson

During his early years as a toy inventor in the 1910s, Otto Langos earned his U.S. citizenship, but still remained a middling employee of the small-time A. A. Tool Company through World War I. Fortunately, his boss / business partner at that company, Melville M. Ostertag, was a young tool designer himself, and seemed to be a creative ally, as two of Otto’s early paper buster patents (a revised Automatic Air Torpedo in 1917 and a Toy Machine Gun in 1920) were assigned to Ostertag and likely manufactured on some small scale by A. A. Tool—although we’ve yet to find surviving evidence of any such production.

Langos also did work for A. A. Tool’s next-door neighbors, the substantially larger Russell Electric Co. Here, in 1922, he partnered directly with company founder Thomas C. Russell on the design of a “Wire Bending Machine,” as well as an early electric curling iron that would be marketed under the “Hold Heet” brand name.

Langos also did work for A. A. Tool’s next-door neighbors, the substantially larger Russell Electric Co. Here, in 1922, he partnered directly with company founder Thomas C. Russell on the design of a “Wire Bending Machine,” as well as an early electric curling iron that would be marketed under the “Hold Heet” brand name.

Bill Cermak’s research suggests that Otto launched the Langson MFG Co. during this same period, in 1923. But it seems like he might have been operating more as an independent contractor through the end of the 1920s, as we could find no direct mention of his own corporation until the onset of the Great Depression, when starting a business may have become more of a necessity.

In 1932, the Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations lists the Langson Manufacturing Company for the first time, with a headquarters at 878 Lill Avenue in Lincoln Park, former home of the Chicago Ferrule & Nut Company. The choice of the name “Langson,” rather than Langos, was likely just an effort to Americanize the word, but it also could have been a sort of odd mash-up of “Langos & Son,” referring to Otto’s eldest son Alfred joining the company. If anything, the name probably should have been “Langdaughter,” as it was actually Otto’s eldest girl, Matilda R. Langos (1904-1991), who was the first partner in the business, serving in the role of secretary/treasurer from 1932 onwards.

[Father & Sons photo from Bill Cermak’s Langson MFG site. From left: Louis Langos, Otto E. Langos, Otto A. Langos, Alfred Langos, and Harold Langos, circa 1940. Not pictured, sadly, are the three Langos daughters, Matilda, Lorretta, & Margaret, all of whom also contributed to the business.]

[Father & Sons photo from Bill Cermak’s Langson MFG site. From left: Louis Langos, Otto E. Langos, Otto A. Langos, Alfred Langos, and Harold Langos, circa 1940. Not pictured, sadly, are the three Langos daughters, Matilda, Lorretta, & Margaret, all of whom also contributed to the business.]

According to Langos family lore, Matilda was always the strongest voice encouraging her father to start his own business, and she would ultimately remain tied to the company herself for roughly four decades. Through that period, her brothers Alfred, Louie, Otto Jr., and Harold also played their parts, as did her younger sister Loretta Krieger, who put in at least 30 years of her own.

The Langos family business, it should be noted, was never strictly a “toy company.” The larger percentage of their output, in fact, was centered on general dies, stampings and metal fabrications for the less-than-glamorous heating industry. But it was the toys—particularly those paper busters—that became LMCO’s lone pop-cultural calling cards.

Out with the Old, In with the Nu-Matic

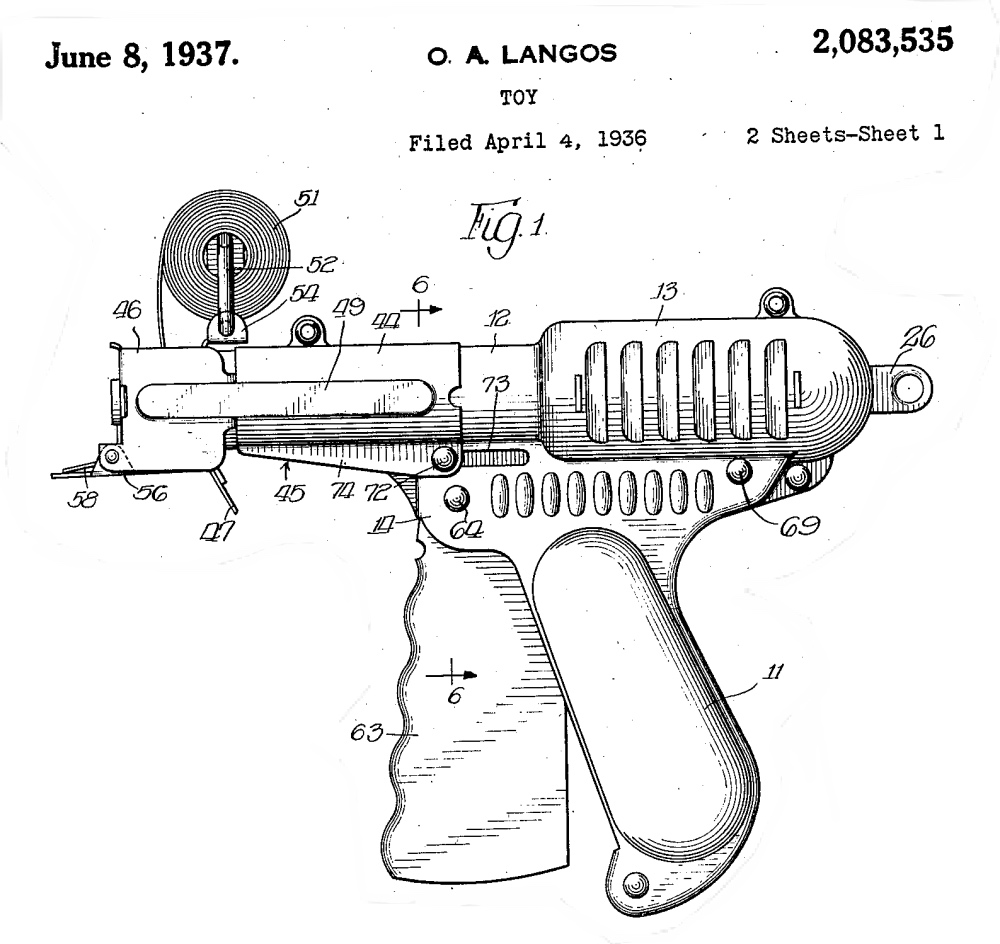

During the Depression, Langson Manufacturing managed to generate enough growth to require two migrations to larger factory spaces, starting with the Huron-Orleans Building in 1933 (a complex in which the Russell Electric Co. was also a tenant), and then on to 429 W. Superior Street in River North by 1937. Here, the factory started churning out Otto’s latest, futuristic looking “Nu-Matic” Paper Buster Gun—a pre-plastic, all-metal legend of the era.

Looking like an alien ray-gun from the pulp comics, the 25-cent shooter was “the finest toy of its kind anywhere. This model employs a new improved method of paper feed which eliminates sticking or clogging and insures a sure-shot every time. It’s the ideal 4th of July toy for children— no chance of burns, since it uses a 400-shot paper roll for ammunition. No chance of injury because all edges are round and smooth. It is constructed entirely of metal, finished in Black with Nickel Breach and Trigger. . . . BEWARE OF IMITATIONS.”

Looking like an alien ray-gun from the pulp comics, the 25-cent shooter was “the finest toy of its kind anywhere. This model employs a new improved method of paper feed which eliminates sticking or clogging and insures a sure-shot every time. It’s the ideal 4th of July toy for children— no chance of burns, since it uses a 400-shot paper roll for ammunition. No chance of injury because all edges are round and smooth. It is constructed entirely of metal, finished in Black with Nickel Breach and Trigger. . . . BEWARE OF IMITATIONS.”

Indeed, as no surprise, other desperate toy companies of the ‘30s weren’t hesitant to try and rip off Langson’s designs, and an aging Otto and his team were constantly having to stay a step ahead of new upstarts, while also trying to compete with the more popular offerings of much larger toymakers like New York’s Marx & Co. (makers of the G-Man Gun), the Daisy Manufacturing Co. of Plymouth, Michigan (known for licensing the official toy gun of Buck Rogers, as well as the famous Red Ryder), and the Hubley MFG Co. of Lancaster, PA, whose “Texan” cap gun basically set the standard for the Cody Colt.

LMCO was usually out-marketed and outsold by its stronger rivals, but the company maintained a decent market-share thanks in no small part to Otto Langos’s persistent efforts to keep improving the paper-pop mechanism he’d helped pioneer. His staff of designers—including his kids and other employees now sadly forgotten to history—made Langson’s products stand out with their space-age looks and bright colors. Kids who loved comic books, mobster movies, or fantasy dime novels all had their LMCO weapons of choice. And when America found itself under a more serious, non-fictional threat, Langson was quick to reorganize its arsenal accordingly.

[Otto Langos posing with the company car, circa 1940, when Langson MFG was still based at 429 W. Superior Street. Courtesy of Bill Cermak’s Langson MFG site]

[Otto Langos posing with the company car, circa 1940, when Langson MFG was still based at 429 W. Superior Street. Courtesy of Bill Cermak’s Langson MFG site]

Super Defense!

In the early 1940s, LMCO finally established a more permanent factory space at 4200 W. Wrightwood Avenue in Chicago’s Belmont Gardens neighborhood. This move might have coincided with a military supply contract of some sort, but that much is unconfirmed. It does seem, however, that Langson was able to keep at least some of its toy production going during the war.

As noted earlier, gunpowder rationing had put a literal cap on the cap gun market, so paper buster guns had gained—arguably—a vital role to play in the general morale of youngsters on the homefront; giving them an outlet both for their patriotism and their angst.

[Above: Langson’s last factory, in use from WWII to 1975, is still standing at 4200 W. Wrightwood Avenue in Belmont Gardens. Below: 1946 advertisement for punch press operators at the “new modern plant.”]

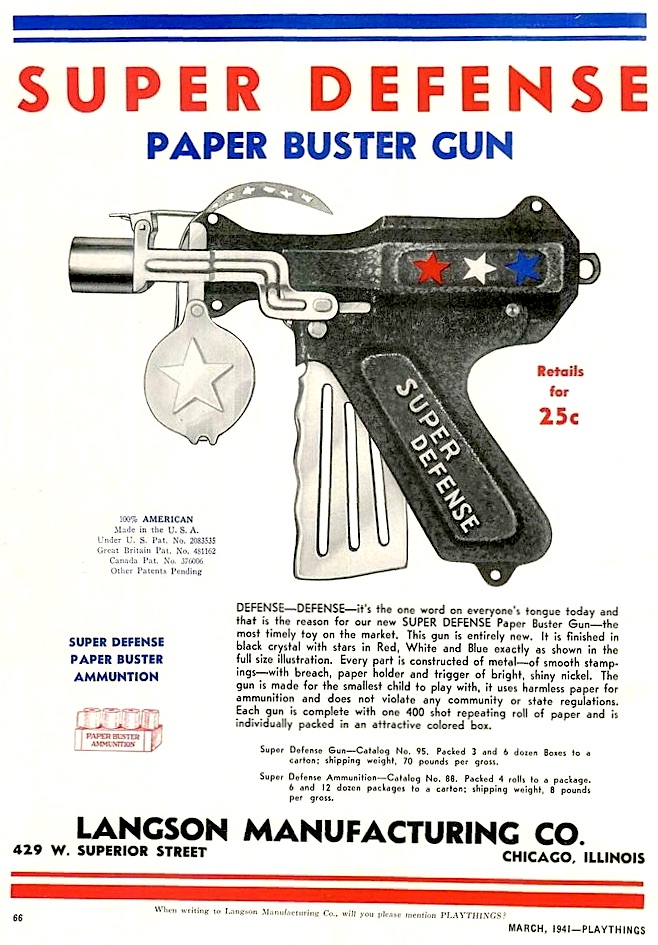

Certainly inspired by world events, the “Super Defense” Paper Buster Gun was Langson’s big seller of the early ’40s—a sort of uniquely All-American marriage of mobster, astronaut, military, and cowboy designs.

“DEFENSE—DEFENSE—it’s the one word on everyone’s tongue today,” read a 1941 advertisement. “And that is the reason for our new SUPER DEFENSE Paper Buster Gun— the most timely gun on the market.”

Throughout the war years, Otto Langos—now well over 60 years old—continued to collect new patents on his paper busters, including several refinements specific to the Super Defense Gun. An updated holder for the paper ribbon ammo, for example, was approved by the patent office on December 9, 1941—two days after Pearl Harbor.—and the complete design of the new gun itself was patented three years later.

Throughout the war years, Otto Langos—now well over 60 years old—continued to collect new patents on his paper busters, including several refinements specific to the Super Defense Gun. An updated holder for the paper ribbon ammo, for example, was approved by the patent office on December 9, 1941—two days after Pearl Harbor.—and the complete design of the new gun itself was patented three years later.

Despite these efforts, Otto was gradually conceding more of the day-to-day operations of the business to his children. And after applying for his final paper buster patent in 1948, he and his wife entered a well earned retirement, splitting time between a house in suburban Cary, Illinois, and a summer home near Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

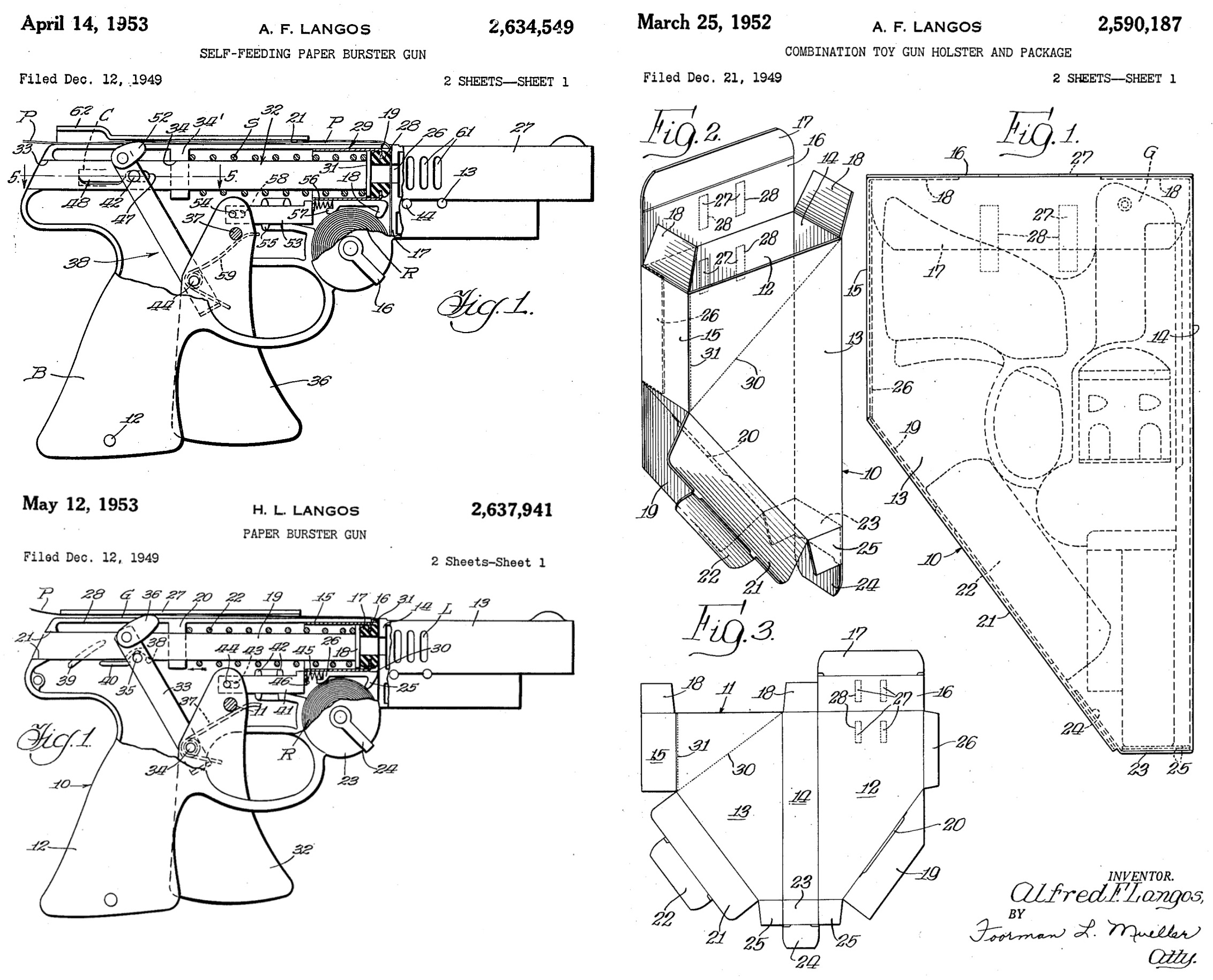

Back in Chicago, this left all new product designs squarely in the hands of sons Alfred and Harold, the two men most instrumental in the development of our museum piece, the Cody Colt.

[Otto’s sons Alfred and Harold Langos applied for several patents in 1949 that went into the making of the Cody Colt gun, including the self-feeding mechanism in the two designs on the left, and the unique packaging that turned into a holster, shown on the right]

[Otto’s sons Alfred and Harold Langos applied for several patents in 1949 that went into the making of the Cody Colt gun, including the self-feeding mechanism in the two designs on the left, and the unique packaging that turned into a holster, shown on the right]

Colt of Personality

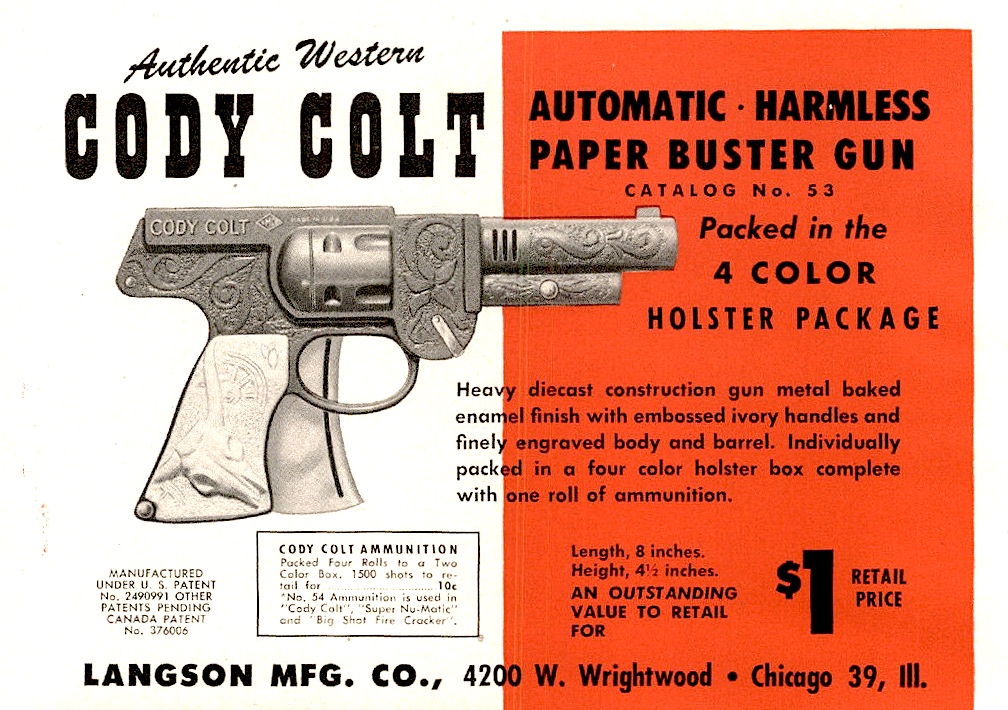

Introduced in 1950 at a selling price of $1 (about $10 with inflation), the Cody Colt was made to a much higher quality than your average dime store six-shooter, and—for that matter—was quite a bit fancier than the cowboy cap guns that would occupy Wal-Mart toy aisles decades later.

Since this was the heyday of the Lone Ranger, Hopalong Cassidy, and Roy Rogers, the “Authentic Western Style” of the Cody Colt had to appease a very large, very enthusiastic, and very demanding audience of cowboys and cowgirls in training. As such, Alfred and Harold Langos made sure it was made with a “heavy diecast construction, gun metal baked enamel finish with embossed ivory handles, and finely engraved body and barrel,” giving the paper buster a weight and substance that no modern plastic popgun could match.

Since this was the heyday of the Lone Ranger, Hopalong Cassidy, and Roy Rogers, the “Authentic Western Style” of the Cody Colt had to appease a very large, very enthusiastic, and very demanding audience of cowboys and cowgirls in training. As such, Alfred and Harold Langos made sure it was made with a “heavy diecast construction, gun metal baked enamel finish with embossed ivory handles, and finely engraved body and barrel,” giving the paper buster a weight and substance that no modern plastic popgun could match.

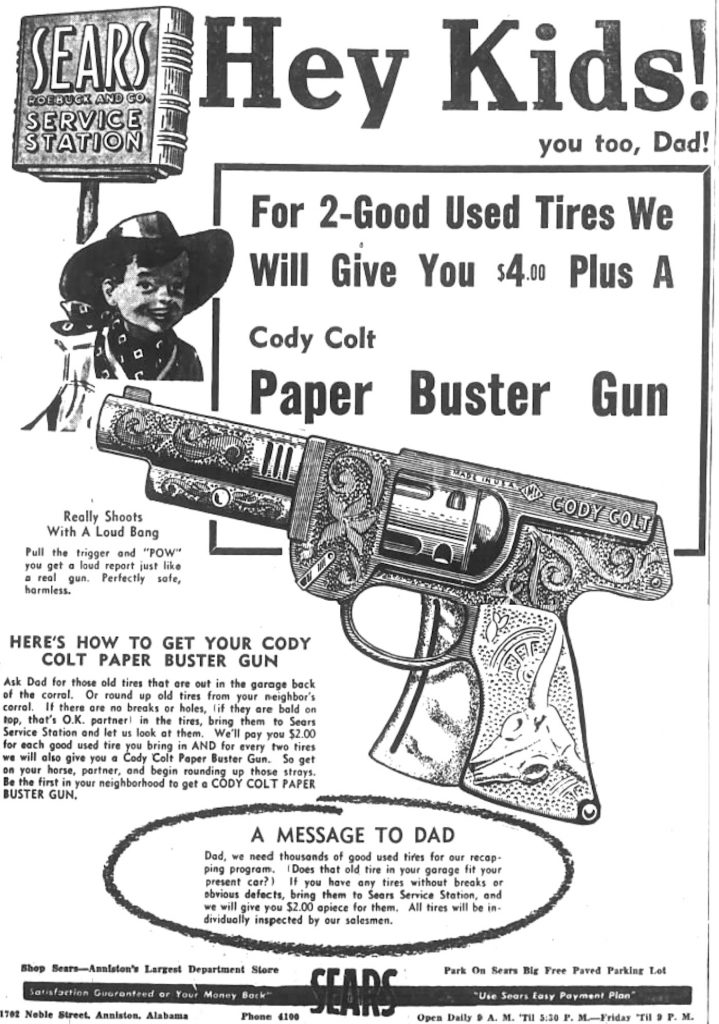

Even the box it was sold in doubled as a colorful holster, and the grip was a friggin’ steer’s skull. Whether you were the kind of kid who fancied himself a black-hatted bandit or a square-jawed lawman, this was the gaudy, obnoxiously loud toy gun of your dreams.

“Really shoots with a loud bang,” one 1951 newspaper ad read. “Pull the trigger and POW, you get a loud report just like a real gun. Perfectly safe, harmless.” Maybe not for a suburban dad suffering from PTSD, but generally, yes, no one is known to have been gravely wounded by a Cody Colt.

[Company founder Otto A. Langos and his wife Magdalena celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary with friends and family in Florida, 1953]

[Company founder Otto A. Langos and his wife Magdalena celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary with friends and family in Florida, 1953]

In 1953, when the Cody Colt was still in hot production, the entire Langos family traveled to Florida via Pullman car to celebrate Otto and Magdalena’s 50th wedding anniversary. Just a year later, Otto died at age 77. Eldest son Alfred E. Langos officially became the chairman of LMCO at that point, but died in 1958 himself at just 53.

By 1962, the company still employed 50 workers at the Wrightwood plant, but with interest in popping guns slowly declining, there is little indication that Langson kept up its toy production—focusing instead on stove burners and other metal fabricating work.

By 1962, the company still employed 50 workers at the Wrightwood plant, but with interest in popping guns slowly declining, there is little indication that Langson kept up its toy production—focusing instead on stove burners and other metal fabricating work.

Otto E. Langos served as president until his own premature death in 1965 at 56, leaving Harold as president, Matilda as secretary/treasurer, John Sebald (husband of another Langos daughter, Margaret) as plant manager, and Loretta Langos-Krieger as office manager.

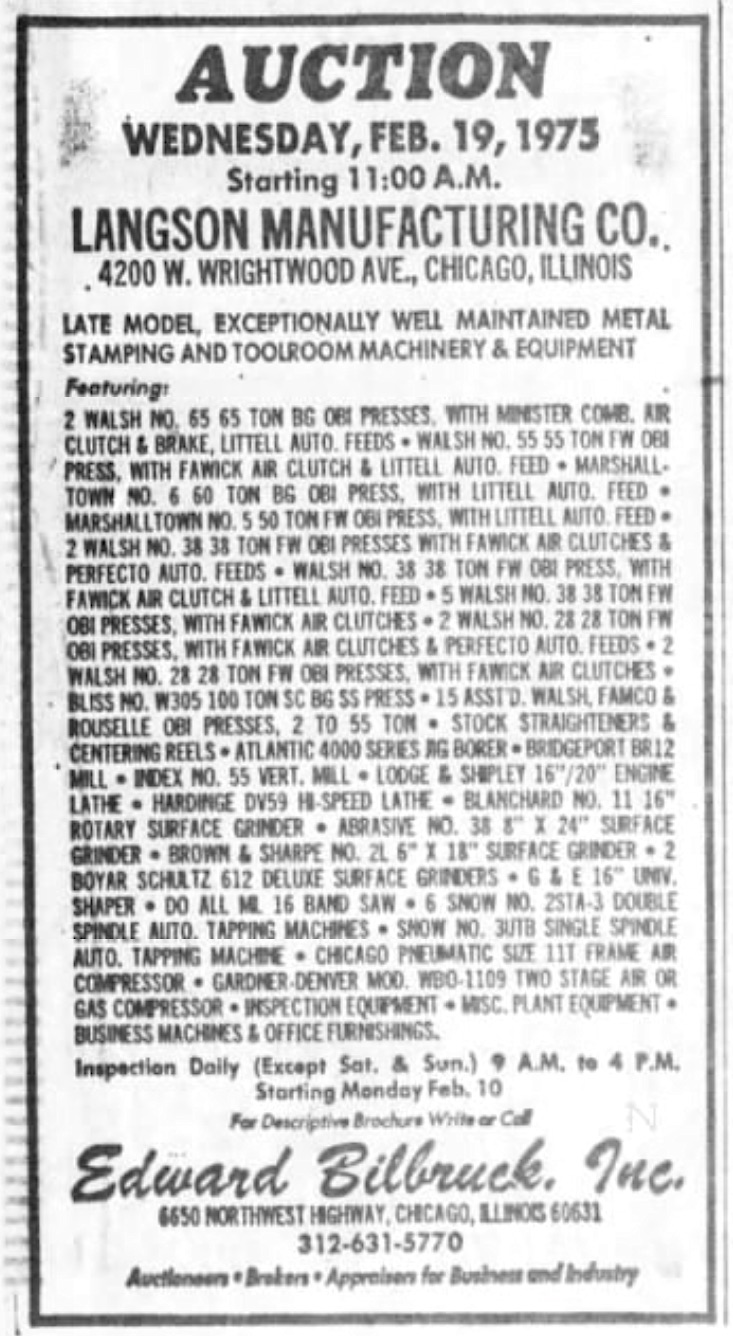

Finally, on February 19, 1975, the long-running plant at 4200 W. Wrightwood opened its doors for a public auction, as 40 years worth of tools and equipment were sold off—marking the official end of a small but important family business. Less than a week later, 65 year-old Loretta Krieger—who’d worked for the company for nearly her whole adult life—passed away, as well.

Sources:

Bill Cermak’s Langson MFG Co. Website

“During Gun Powder Ration, Toy Pistols Popped Paper with Air” – Florida Today, Dec 17, 2007

Cody Colt Ad – Anniston Star (Anniston, AL) – June 10, 1951

“Light and Heavy Manufacturing” – classified ads, Chicago Tribune, July 20, 1917

‘Aerial Torpedo Cane” ad – Playthings, April 1938

“Toasting Each Other” (Langos 50th Wedding Anniversary) – Fort Lauderdale News, March 19, 1953

“Huron-Orleans Building is Now 90 pct. Occupied” – Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1933

“Nu-Matic Paper Buster Gun” ad – Playthings, May 1937

“Super Defense Paper Buster Gun” ad – Playthings, March 1941

Alfred E. Langos obit – Chicago Tribune, Sept 27, 1958

Otto E. Langos obit – Chicago Tribune, Jan 28, 1965

Loretta Krieger obit – Wheeling Herald, Feb 26, 1975

Matilda R. Langos obit – Tampa Bay Times, December 20, 1991

“Auction” – Detroit Free Press, Feb 9, 1975

Hullo, my name is Denis Cherry, and I live in Fremantle in Western Australia. I recently purchased some old tools, and amongst them was a very old cast, open ended spanner with an embossed “LMCO” within an indented section of the shaft. I Googled “LMCO” and this site seemed the only possibility of a connection. Whether tools, that is spanners, were made by Langson Manufacturing Company I wouldn’t have a clue, and am hoping you may have more information. I presume I can send a photo if that would be helpful? Thank you for your assistance.

Daryl, below is a link for you to Langson Mfg. Co. who was the maker of the paper buster toys that you are asking about. There are many pictures, and a lot of other information about these toys there. I hope you enjoy the site! My great grandfather Otto Langos was the inventor of these toys, and the founder of Langson Mfg. Co.

Link> https://langson.wixsite.com/lmco

Regards,

Bill Cermak

I remember in Chicago area about 1958 one of the neighbor hood kids had “Super Pneumatic” paper buster pistol. It seems like it was aluminum and shaped more like a .45 auto. I would enjoy finding out anything about this or even a picture of one. I remember at the time I did not know how to pronounce pneumatic or know what it meant.

Thanks,

Daryl