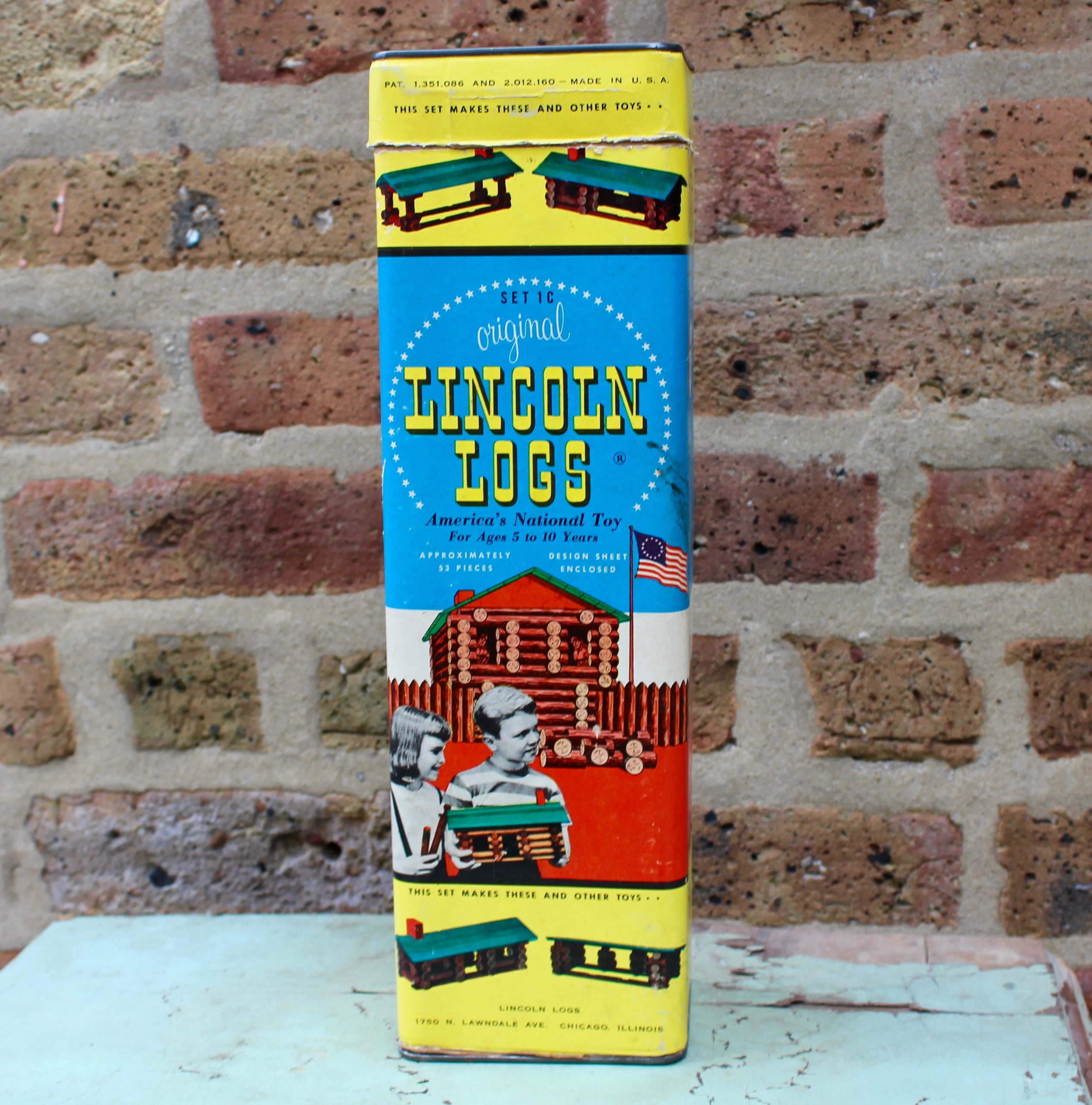

Museum Artifact: Original Lincoln Logs Set 1C, c. 1958

Made By: Lincoln Logs, 1750 N. Lawndale Ave., Chicago, IL [Humboldt Park]

“When I completed the design for ‘Lincoln Logs’ toy construction blocks, their success encouraged me, and making wooden objects became my temporary source of income. Marshsall Field’s bought all I could make.” –John Lloyd Wright, from his memoir My Father, Frank Lloyd Wright, 1946

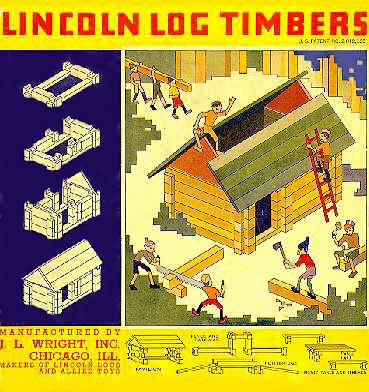

One of the most successful toys of the 20th century was also one of the most ingenious from a manufacturing sense. Why worry about complex assembly lines and detailed craftsmanship when you can just sell a kid a box of raw materials and let them finish the job?! In an industry typically dominated by hip new technology and shiny objects that “do stuff,” Lincoln Logs were nothing more than what they purported to be—logs. And yet, through a magical confluence of imagination, nostalgia, and patriotism, they somehow became “America’s National Toy.”

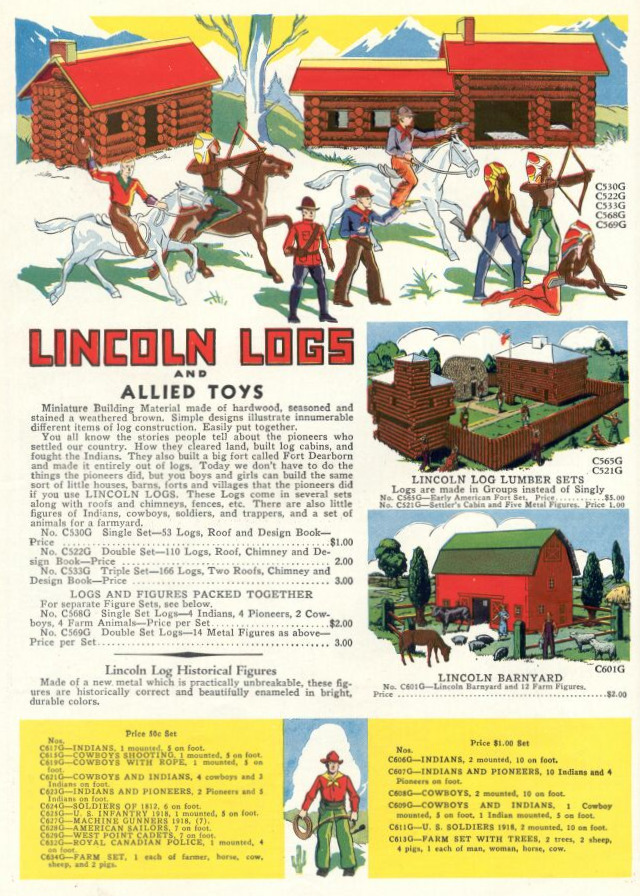

“You all know the stories people tell about the pioneers who settled our country,” read a 1934 Lincoln Logs advertisement. “How they cleared land, built log cabins, and fought the Indians. They also built a big fort called Fort Dearborn and made it entirely out of logs. Today we don’t have to do the things the pioneers did, but you boys and girls can build the same sort of little houses, barns, forts and villages that the pioneers did if you use LINCOLN LOGS.”

Besides the appreciated Fort Dearborn shoutout, the key takeaway from the copy above is the phrase “boys and girls.” Gender based toy segregation usually dictated the selling of dollhouses to girls and train sets to boys, but Lincoln Logs were for everybody. There is even a sly reference to building “little houses” at a time when Laura Ingalls Wilder’s “Little House” book series was all the rage among the gentler set.

There were many imitators that tried to steal Lincoln Logs’ niche over the years, including the “Frontier Logs” of crosstown rival Halsam Toys. But the lasting appeal of Lincoln Logs was already baked in—the perfect product with the perfect marketing campaign, all born from the mind of a man with a unique perspective on the delicate balance between 20th century urban progressivism and rural, frontier romanticism. John Lloyd Wright, after all, was the son of the guy who invented the very concept of “organic architecture.”

A Log, Log Time Ago . . .

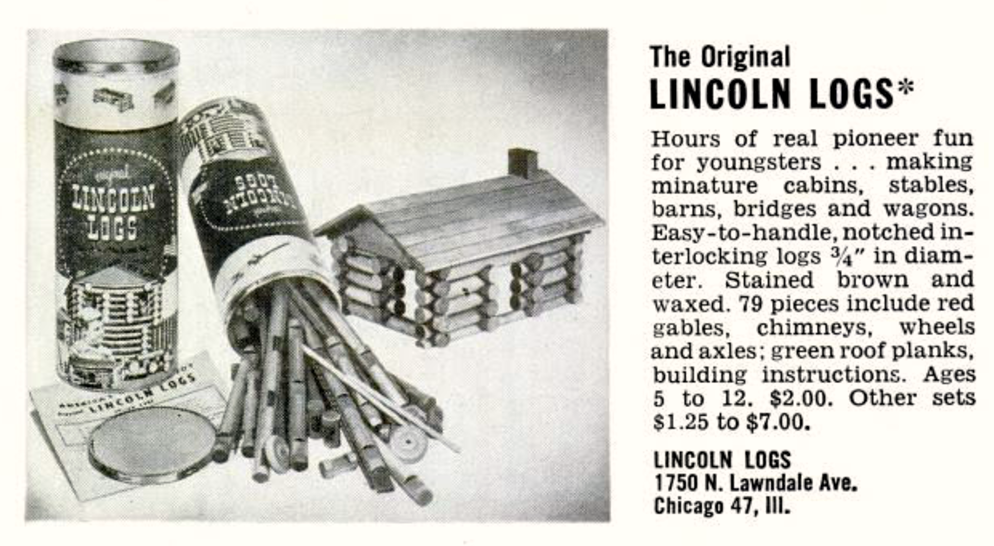

From the 1940s through the 1960s, Lincoln Logs’ Chicago factory was located at 1750 N. Lawndale Avenue in Humboldt Park, a space previously occupied by the Harmony Instrument Company. This positioned it conveniently along the same Bloomingdale train line as many other industrial all-stars of the era, including the Ludwig Drum Co. and Schwinn Bicycles. The building was owned and operated by the Playskool MFG Co., which purchased Lincoln Logs in the early ‘40s and helped elevate it into one of the ubiquitous toys of post-war suburbia.

By the 1980s, of course, virtually all the manufacturing along this strip was gone, and the elevated track of the Bloomingdale Line was abandoned and grown over. As a bit of a happy ending to that portion of our story, however, the city spent ten years and $95 million reviving the old track into a unique 2.5 mile bike path and public space, which officially opened in 2015. It’s now called the Bloomingdale Trail, or—to the locals— “The 606.”

As part of the rustalgic scenery visible from the The 606, you can still see the old Lincoln Logs plant, which—unlike most factories from its era—has neither been demolished nor turned into condominiums. In fact, it looks like it’s nary changed a bit since the days when workers churned out tiny timber all day.

[The former Lincoln Logs factory at 1750 N. Lawndale Ave. is currently available if you need it]

[The former Lincoln Logs factory at 1750 N. Lawndale Ave. is currently available if you need it]

The men and women who worked at the Lawndale factory might not have had the most rewarding gig in the world. While machining notches into little wood cylinders could pay the bills, all the fun of seeing the finished product—cabins, forts, villages, and all the rest—was left to the unseen customer. Still, whether they knew it or not, the Lincoln Loggers were all carrying on the artistic vision of a man who dared to dream big by thinking small. This man wasn’t just a toymaker; he was an architect! And though he wasn’t famous, his dad certainly was.

ProLOGue: The Daddy Issues of John Lloyd Wright

Both of Michael Jordan’s sons played basketball, but neither made it to the NBA. John Lennon’s sons became musicians, but found only marginal commercial success. Two of Ernest Hemingway’s sons wound up writing separate auto-biographies with the titles Papa: A Personal Memoir and My Life With and Without Papa.

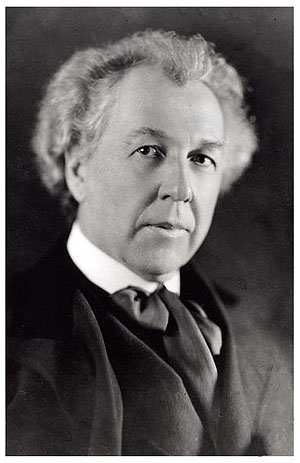

For all the supposed perks of being the progeny of the legendary—wealth, nepotism, book deals, etc.—there’s also the almost unavoidable letdown of discovering your own comparable limitations. That was certainly a dynamic John Lloyd Wright came to understand as the son of America’s best known architect. Like so many others in his boat, he first tried to rebel against expectation—“Imma go my own way!” This was followed by the inevitable attempt to follow in his father’s footsteps, which in turn resulted in the writing of a tell-all memoir rife with references to “my papa.” While walking that traditional path, however, Wright also took an unexpected detour that actually gave him a significant legacy all his own—even if most people don’t know about it.

For all the supposed perks of being the progeny of the legendary—wealth, nepotism, book deals, etc.—there’s also the almost unavoidable letdown of discovering your own comparable limitations. That was certainly a dynamic John Lloyd Wright came to understand as the son of America’s best known architect. Like so many others in his boat, he first tried to rebel against expectation—“Imma go my own way!” This was followed by the inevitable attempt to follow in his father’s footsteps, which in turn resulted in the writing of a tell-all memoir rife with references to “my papa.” While walking that traditional path, however, Wright also took an unexpected detour that actually gave him a significant legacy all his own—even if most people don’t know about it.

Yes, it was John Lloyd Wright—son of Frank Lloyd Wright—who invented everyone’s second or third favorite stackable construction game, Lincoln Logs.

We’re actually fresh off the 100th anniversary of that moment in 1916 when a 24 year-old John Wright—during one of his many estrangements from his dad—decided to pursue an idea that had been percolating in his mind for a while. By this point, he’d only been working in architecture for a few years, having reluctantly succumbed to the gravity of his own name. But as that career staggered a bit out the gates, a side gig as a toy designer was about to begin.

Logging On

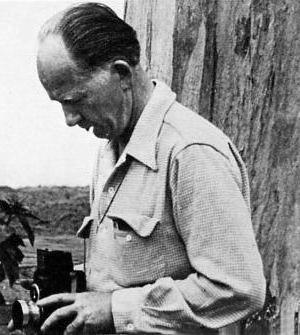

For much of 1916, John Wright had been working alongside his father in Japan, helping to sketch out a design plan for Tokyo’s new Imperial Hotel. Watching the process of developing such a complicated project was hugely educational and rewarding. Getting stiffed on a paycheck and ultimately fired by his own mildly deranged dad—by comparison—was a bummer.

[John Lloyd Wright (left) looking over blueprints with his father in Tokyo, 1916]

[John Lloyd Wright (left) looking over blueprints with his father in Tokyo, 1916]

A free agent in Chicago once more, John went back to the literal and proverbial drawing board. He observed the recent successful introduction of TinkerToys (invented by Charles Pajeau in nearby Evanston) and erector sets, and set forth combining the budding trend of cheap model construction toys with some of the concepts he’d acquired in Japan.

Some say he chose the name “Lincoln” to honor his dad’s original middle name: Frank Lincoln Wright (he changed it to Lloyd because… I don’t know, this isn’t about him). The more widely held belief for decades, however—aided by the product’s own marketing materials—was that Lincoln Logs were a clear nod to our 16th president; that noted log cabin builder himself, Honest Abe.

Either way, John Lloyd Wright had adapted the old-fashioned log cabin playsets of the past into a distinctly modern construction toy. And it was largely on the strength of one simple design choice: those flat notches machined into the ends of each miniature redwood beam. Now, it was far easier for a kid to interlock multiple logs without a Jenga style collapse. The public responded accordingly.

Either way, John Lloyd Wright had adapted the old-fashioned log cabin playsets of the past into a distinctly modern construction toy. And it was largely on the strength of one simple design choice: those flat notches machined into the ends of each miniature redwood beam. Now, it was far easier for a kid to interlock multiple logs without a Jenga style collapse. The public responded accordingly.

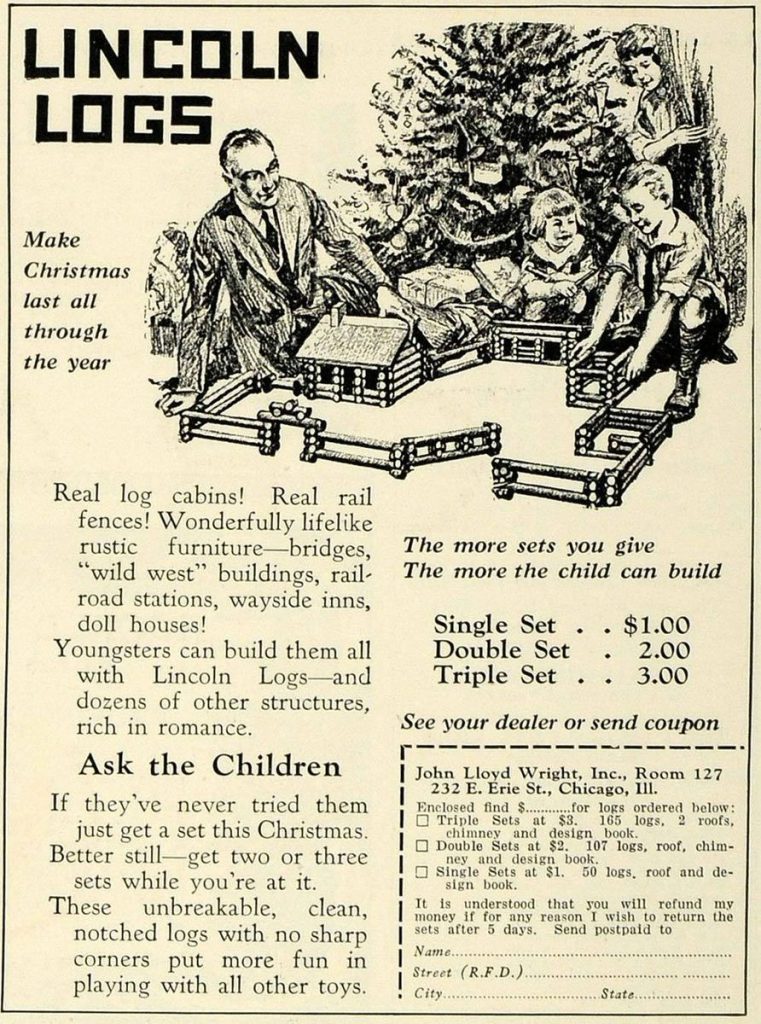

During World War I, when other toy manufacturers were slowing production to help build military supplies, Wright and business partner Walter Pratt Beachy started the Red Square Toy Company in Chicago, mass-producing Lincoln Logs for a country in need of tangible, vaguely nostalgic distractions. “Red Square” was a reference to the red square logo that Papa Frank used on a lot of his official documents. But with anti-Communist sentiment on the rise, John wisely changed course and started selling his products under his own name, John Lloyd Wright, Inc., within a couple years.

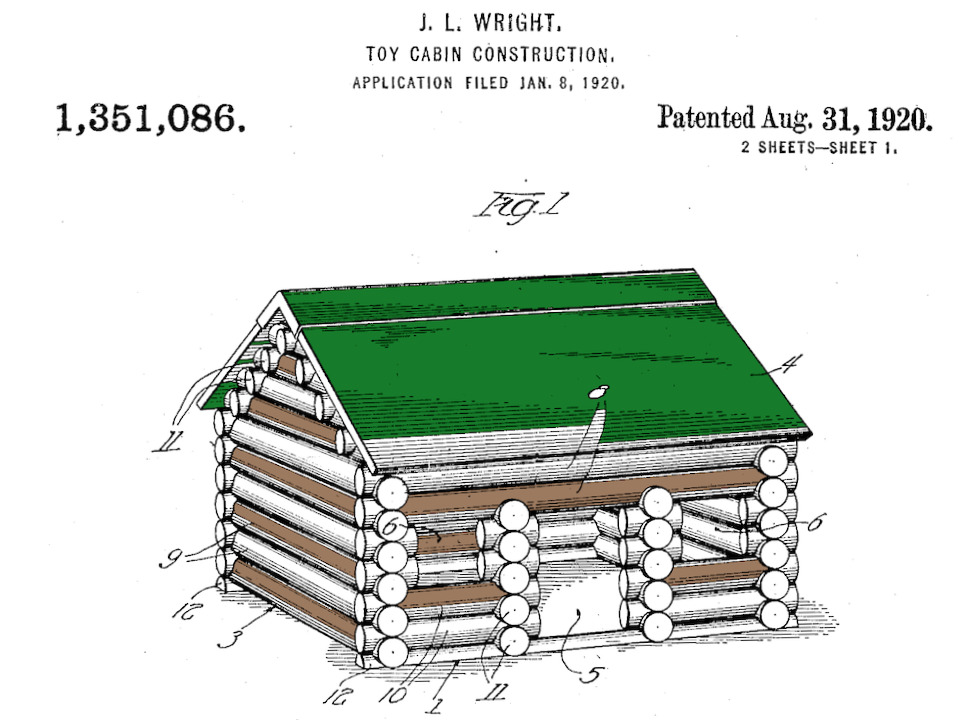

Wright officially patented his wondrous toy logs in 1920, describing them as such:

“The object of the invention is to produce a novel toy in the form of a multitude of members or parts in the form of logs, so shaped and treated as to provide the material for the building of diminutive log cabins and other like structures.”

Though he now lived in Long Beach, Indiana, Wright had an official Chicago office for all business related to Lincoln Logs and his other new property, Allied Toys. That office, weirdly, floated around constantly throughout the 1920s, but rarely further away than an elevator ride or a brief stroll—224 E. Erie Street (Room 179), 232 E. Erie Street (Room 127, then Room 136, then Room 37), 332 E. Erie Street (Room 72). It sounds a bit like he was getting treated like Milton from Office Space, but nonetheless, John Wright’s second career as toy man was underway—even if his heart remained devoted to full-scale house construction.

The Playroom

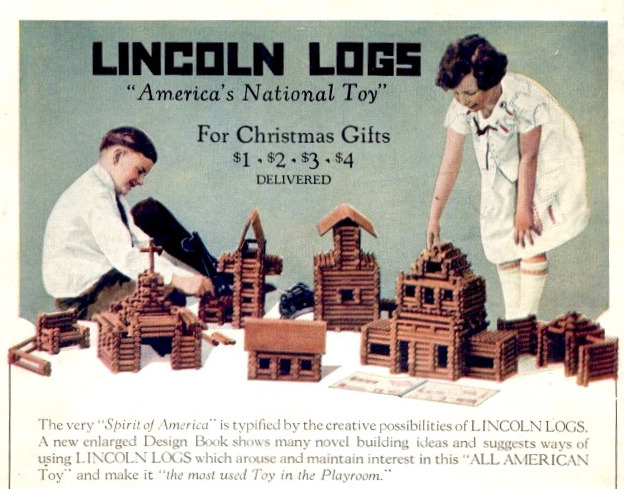

“The very ‘Spirit of America’ is typified by the creative possibilities of LINCOLN LOGS,” a 1926 magazine ad proclaimed, further describing the builder kits as “the most used Toy in the Playroom.”

The word playroom, interestingly enough, had heavy connotations for John Wright. Maybe more so than the Imperial Hotel, Tinker Toys, or Abraham Lincoln, it was memories of his own lavish childhood playroom—designed by his father for their Oak Park home—that really made the thought of toy-making so appealing. [Photo: John L. Wright as a goofy ass toddler, circa 1897]

The word playroom, interestingly enough, had heavy connotations for John Wright. Maybe more so than the Imperial Hotel, Tinker Toys, or Abraham Lincoln, it was memories of his own lavish childhood playroom—designed by his father for their Oak Park home—that really made the thought of toy-making so appealing. [Photo: John L. Wright as a goofy ass toddler, circa 1897]

“My first impression upon coming into the playroom [as a child] from the narrow, long, low-arched, dimly lighted passageway that led to it was its great height and brilliant light,” Wright wrote in his 1946 memoir, My Father Who Is On Earth. “The ceiling twenty feet high formed a perfect arch springing from the heads of group windows which were recessed in Roman brick walls. The oak floor marked off with kindergarten arrangement of circles and squares was always strewn with queer dolls, building blocks, funny mechanical toys, animals that moved about and wagged their strange heads.

“. . . In this room were the milestones to maturity; treasures, friends, comrades, ambitions; and through the years I have dreamed through the inspiration of this playroom.”

And so, even John Wright’s apparent divergence from his father’s influence and embrace of a new enterprise were—it seems—not really that at all. Lincoln Logs, like those “building blocks” from the old playroom, were a reach into the past, not the future. John was still looking for his father’s approval.

EpiLOGue

Unfortunately, earning the sincere respect of an egomaniac was no easy task. For all of John’s fond memories of the playroom, he also had the scars of watching his father abandon him and the rest of his family in 1909, running off with the wife of a client in a scandalous, public affair. After that same mistress was later murdered by a crazed servant, Frank Lloyd Wright drifted into stranger and stranger behavior, marrying a series of “mystics” and running his architecture school like a hippie commune. Through it all, he grew only increasingly convinced of his own greatness and less sure about everyone else’s.

Unfortunately, earning the sincere respect of an egomaniac was no easy task. For all of John’s fond memories of the playroom, he also had the scars of watching his father abandon him and the rest of his family in 1909, running off with the wife of a client in a scandalous, public affair. After that same mistress was later murdered by a crazed servant, Frank Lloyd Wright drifted into stranger and stranger behavior, marrying a series of “mystics” and running his architecture school like a hippie commune. Through it all, he grew only increasingly convinced of his own greatness and less sure about everyone else’s.

“I had to choose between honest arrogance and hypocritical humility,” he once said. “I chose honest arrogance.”

John Wright, meanwhile, described his up-and-down relationship with his brilliant father as “a lifelong struggle to avoid being destroyed.”

Nonetheless, by most human measures, the son did his father proud, even if it’s just in the figurative sense. John Lloyd Wright ran his toy business for 20 years before selling to Playskool (some say he sold the Lincoln Logs patent for just $800—a swindling—but it’s likely this was just fine-print within a much, much larger deal for the entirety of his Chicago business).

Nonetheless, by most human measures, the son did his father proud, even if it’s just in the figurative sense. John Lloyd Wright ran his toy business for 20 years before selling to Playskool (some say he sold the Lincoln Logs patent for just $800—a swindling—but it’s likely this was just fine-print within a much, much larger deal for the entirety of his Chicago business).

Throughout the Depression, John worked double-duty, continuing to design and build toys as well as actual people-sized homes, mostly in Indiana. Interestingly, like his father before him, he fell in love with a client’s wife in 1939 and ran off with her, abandoning his family to move to Del Mar, California. There, he built more real houses (nice ones, if not exactly tourist attractions), developed some more of his construction toys (“Wright Blocks” and “Timber Toys” had cult followings), and lived out his golden years—never quite shaking those old Oak Park demons.

[One of JLW’s side projects, “Wright Blocks,” were created in the early 1930s with a modern flair quite different from Lincoln Logs. They were made by the Modern Toy Building Co. of Philadelphia]

[One of JLW’s side projects, “Wright Blocks,” were created in the early 1930s with a modern flair quite different from Lincoln Logs. They were made by the Modern Toy Building Co. of Philadelphia]

On a final note, Lincoln Logs—which were manufactured in China for most of the past couple decades—returned to the U.S. in 2014, with all manufacturing done from a single plant in Burnham, Maine. The brand is now owned by a Pennsylvania company called K’NEX, which also owns video game game icons like Pac Man and the Angry Birds, plus—appropriately enough—Lincoln Logs’ old Illinois rival, Tinker Toys.

None of Abraham Lincoln’s sons, by the way, ever became President of the United States, and I’m not sure any of them ever built a log cabin either.

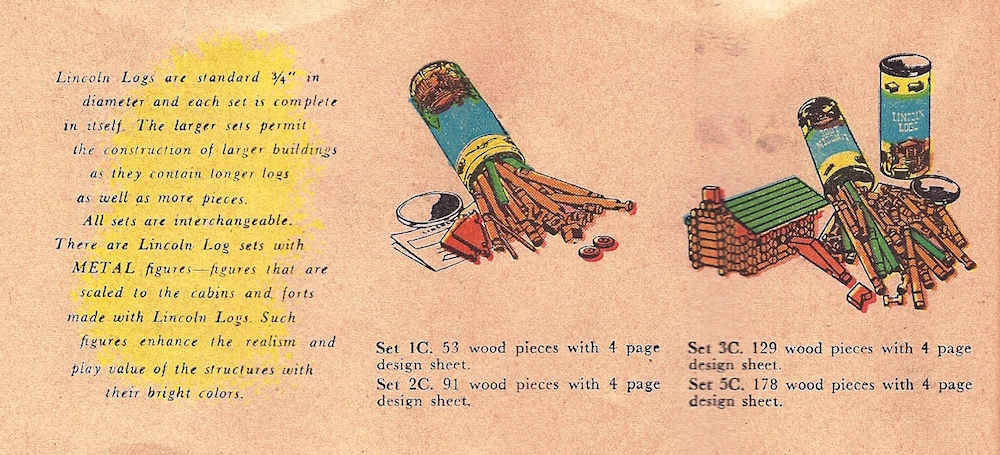

[Page from 1950 Playskool catalog. Playskool purchased Lincoln Logs in the early ’40s]

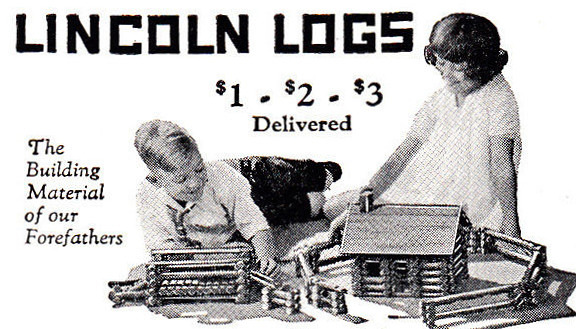

[Lincoln Logs magazine ad from 1934]

[Lincoln Logs magazine ad from 1934]

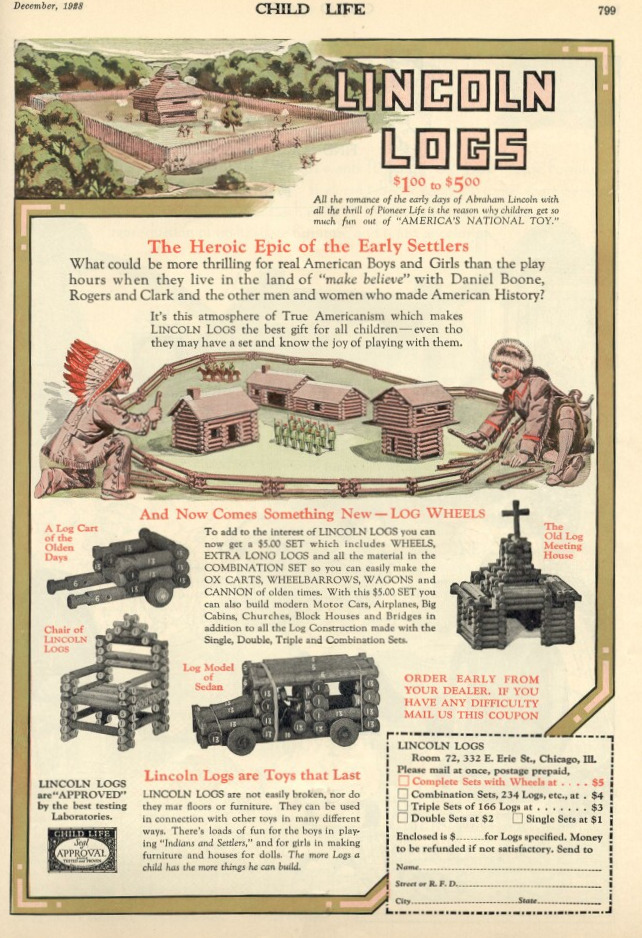

[1928 advertisement]

[1928 advertisement]

Sources:

My Father Who Is On Earth, by John Lloyd Wright, 1946

KNEX: (Current Lincoln Logs site)

IncredibleArt.org: “John Lloyd Wright”

Independent.co.uk: “Architect of Desire”

Archived Reader Comments:

“Hundreds of wonderful hours making different houses, forts, etc. It was so exciting creating different construction items.” —Dave, 2020

“just picked up the square box $3 set at Goodwill for $2 Missing the lid and 2 1/2 pieces out of 129 pieces, great patina, love it!” —pt, 2019

“Great story. Well written. Having grown up on the border of Humboldt Park and Logan Square in the 60s, I remember many bike rides down Bloomingdale Avenue. I went to school at Yates Elementary on Bloomingdale and Mozart. I also grew up with an interest in architecture, no doubt partly influenced by playing with Lincoln Logs as a kid. I did not know that FLW’s son was the inventor. Thank you for your efforts in memorializing Chicago manufacturing.” —Jeff Curran, 2019

I have a metal toy soldier on the bottom of the base is cast ” LINCOLN LOGS U.S.A.”

and is dressed as a ww1 U,S. soldier, marching with rifle on the right shoulder.

Can anyone tell me when this was made or any thing about it?

I have a doll house made of Lincoln loge from the early a 1950. It’s approximately 2 feet by 3 feet. Has electricity and glass windows.

It’s 2 stories high. A living room and kitchen on the first floor. 2 bedrooms and a bathroom on the second. The back is open. I do have some pix

Hello from Brookfield, Wisconsin,

I’ll begin by stating that, “no, I am not a robot” but I am a long time collector of American made toy figures, and in particular toy soldiers Every so often I come across pieces of interest and if the price is right I will purchase it. Some time in the 1990s I was encouraged by a friend to purchase the Lincoln Log OG, SON OF FIRE set. He told me to hang on and in time they should go up in value. I am now interest in selling the entire set of six. They are all in good shape and in terms of paint I would say the following: Og -93%, Nada – 95%, Big Tooth, 87%, Three Horn – 90%Rex – 99%, and Ru – 89%. If you are interest you may contact me by email. Thanks in advance for your consideration or any comments you may have. Sincerely, Robert Laabs

I have a miniature lincoln log set, logs are square about 1/2 in. can anyone provide info. thanks

I have an unopened Lincoln Log canister. It looks just like the one in the picture,

although the coloring looks “weathered.” The drawstring is still intact. I’m not sure what it’s worth or what to do with it.

Keep it safe. And dry.

I have a large wooden box that says “The Original Lincoln Logs”. It contains 151 logs. Under the handle it has a number “0166 K”. What does that mean and when was this made?

Thanks