Museum Artifact: Three Musketeers, Milky Way, Snickers, and Mars Toasted Almond Bar Display Boxes, 1930s-1950s

Made By: Mars Incorporated, 2019 N. Oak Park Ave, Chicago, IL [Galewood]

“The finest quality ingredients blended by the most skillful workers in the most modern institution of its kind.” – Mars Bar display box, 1930s

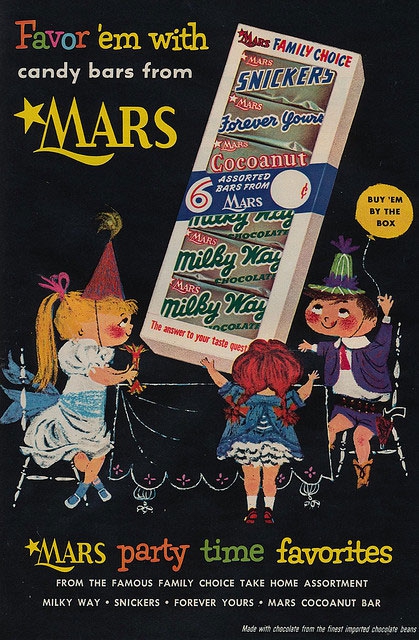

Still consistently ranked among the top ten largest privately owned companies, of any kind, in the world, Mars Incorporated ($45 billion in sales in 2022) stands in stark contrast to most of the cherished but long-defunct Chicago confectioners of yore—a graveyard of ex-rivals that includes Curtiss, Bunte, Williamson, Shotwell, and Peerless, to name just a handful. So monstrous is the Mars empire, in fact, that it recently absorbed one of Chicago’s other international snack giants, the Wrigley Company, with the casual “why not” attitude of an impulse buy at the grocery store. This acquisition added a line of leading chewing gum brands to a Mars stable of products that already boasts the country’s top selling candy (M&M’s) and candy bar (Snickers), plus shopping cart ubiquities such as Ben’s Original Rice and Pedigree and Whiskas pet food.

Naturally, a corporation of this size—with a century of history in its rearview—has generated plenty of attention and analysis over the years. In its early days, such scrutiny was welcomed by flamboyant company founder Frank C. Mars, whose lavish, country-club style Chicago factory once had an open-door policy to the world. Across subsequent generations, however, the keepers of the Mars empire have maintained an almost notorious shield of secrecy—often unwilling to give interviews, have photos taken, or even allow outsiders to tour their factories. The family’s massive wealth, similarly, wasn’t flaunted with eye-catching extravagances, as a low profile became the strict Mars dress code.

“The ability to be secretive is one of the finest benefits of having a private company,” third-generation company president Forrest Mars, Jr., said in a rare address at Duke University in 1988. “Privacy at times today seems like a relic of the non-media past, but it is a legal right – morally and ethically proper and even desirable – and a key to healthy, normal living. It allows us to do the very best we can, the very best we know how, and to do so without being concerned with self-aggrandizement.”

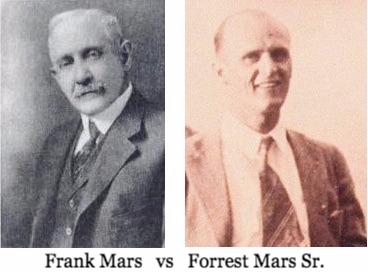

Paradoxically, the silent nature of the Marses (Martians?) only made them the focus of more intrigue over the decades, as a long line-up of journalists tried to unravel the various mysteries baked into the business, from the debated origins of its most popular products to the hidden turmoil underlying its leadership. In particular, the bitter fallout between Frank Mars and his son Forrest Mars, Sr.—while certainly not a part of the official corporate timeline—has always seemed essential to understanding the company’s unique evolution.

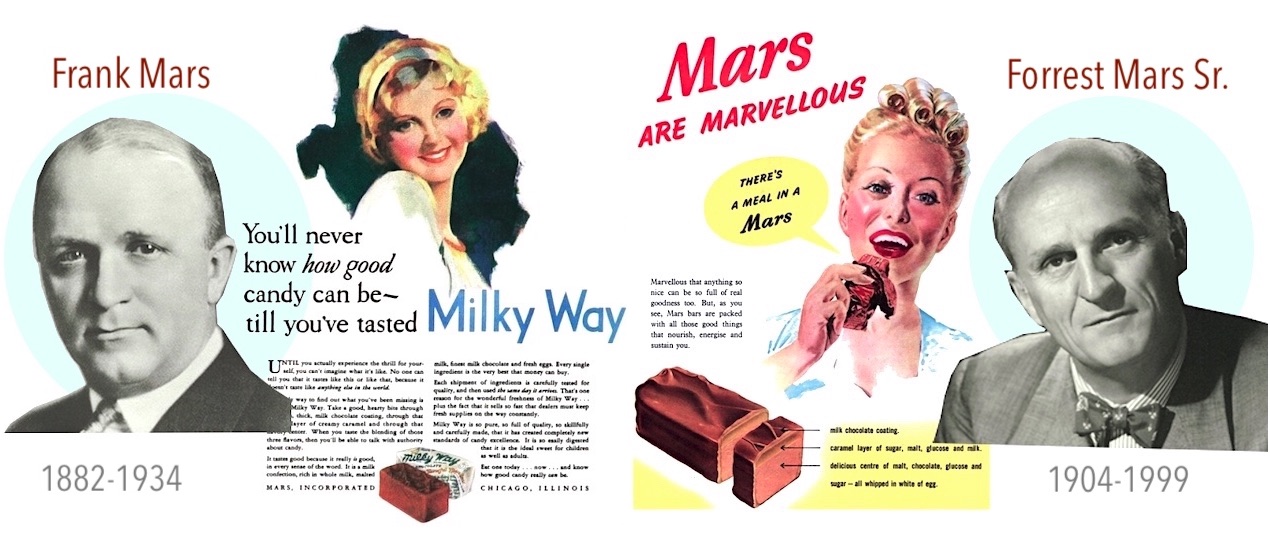

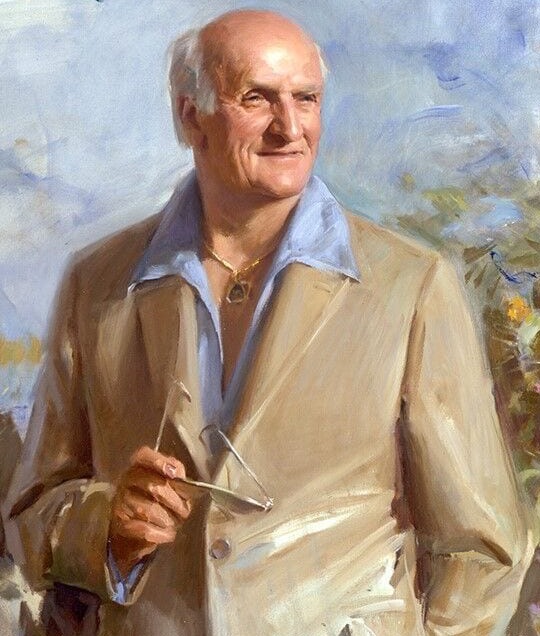

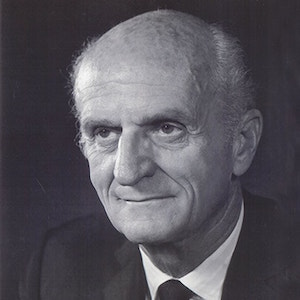

[Left: Company founder Frank Mars and an 1930 American advertisement for the Milky Way. Right: Frank Mars’s son Forrest Mars and a 1948 British ad for the Mars Bar]

You can still find evidence of that 90 year-old family feud, in fact, if you visit the United Kingdom, where the candy bar we know as the “Milky Way” is called a “Mars Bar,” and the bar they call a “Milky Way” actually tastes like a “3 Musketeers” (which doesn’t exist overseas). Up until the 1990s, even the beloved Snickers was known to the Brits as the “Marathon” bar. These random incongruities, amongst others, are left over from the 1930s, when Forrest Mars, Sr.—booted out of Chicago by his dad and banished to England—turned Mars Candy into two polarized but parallel family businesses, separated by a literal and metaphorical ocean.

Led by conflicted figureheads with conflicting philosophies, the two halves of Mars would eventually re-converge into the company we know today, but not with any happy family reconciliations. Mars might be the fourth planet from the sun, but before that, lest we forget, it was the Roman god of war.

[The concept for M&Ms, one of Mars’s flagship candies, was actually developed by Forrest Mars, Sr., when he was in exile from Mars Inc.’s Chicago mothership during the 1940s]

History of Mars, Inc., Part I. The Rover

Like any good multi-billion dollar company worth its salt, Mars Inc. began in the most humble of fashions—with early days spent scrounging for cash in some of the colder corners of the country.

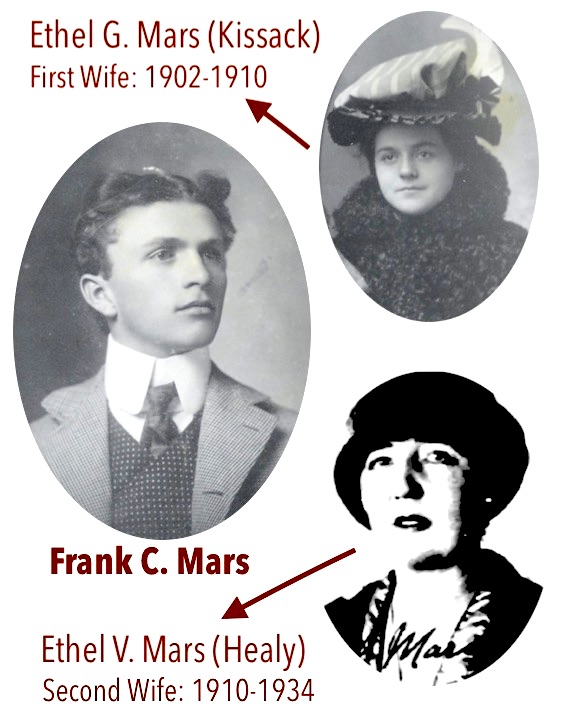

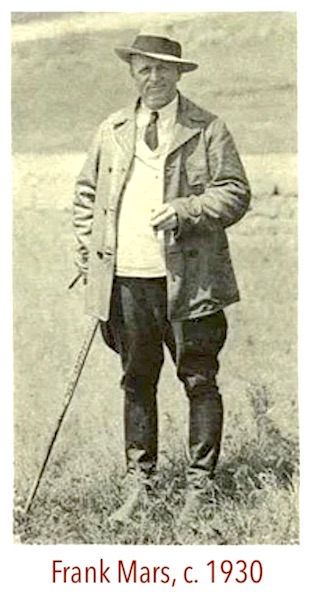

Around the turn of the century, Franklin Clarence Mars (b. 1882)—a polio survivor and son of a gristmill worker—was working as a chips salesman in Wadena, Minnesota, trying meagerly to support his first wife, Ethel G. Mars (Kissack), and their young child, Forrest (b. 1904). Looking for a new opportunity, Frank soon moved his family across the country to Tacoma, Washington, but once they got there, his struggles only continued.

By 1910, Ethel had run out of patience. She divorced Frank, citing his failure to provide for the family. In the aftermath—due to her own limitations—she had to send away 6 year-old Forrest to live with his grandparents in Saskatchewan, where he would spend most of his youth enduring a very strict, Episcopalian upbringing.

While young Forrest maintained a warm correspondence with his mother during his Canadian exile, there was no such relationship with Frank, who offered little in both communication and child support money. One can surmise that the idiosyncrasies and insecurities of Forrest Mars—and his bitter feelings toward his father—were forged during these years.

In fairness, Frank Mars wasn’t necessarily resigned to the role of the irredeemable deadbeat dad. Still a young man, he was trying his damndest, it seems, to make up for past missteps.

Starting in 1911, he had invested all his energy (and dwindling capital) into a DIY candy business in Tacoma, which he operated with his second wife, coincidentally also named Ethel . . . in this case, Ethel V. Mars (Healy). Even after another string of failures nearly ruined them, Frank and Ethel 2 kept the business going, developing an original line of butter cream candies that gained a small following.

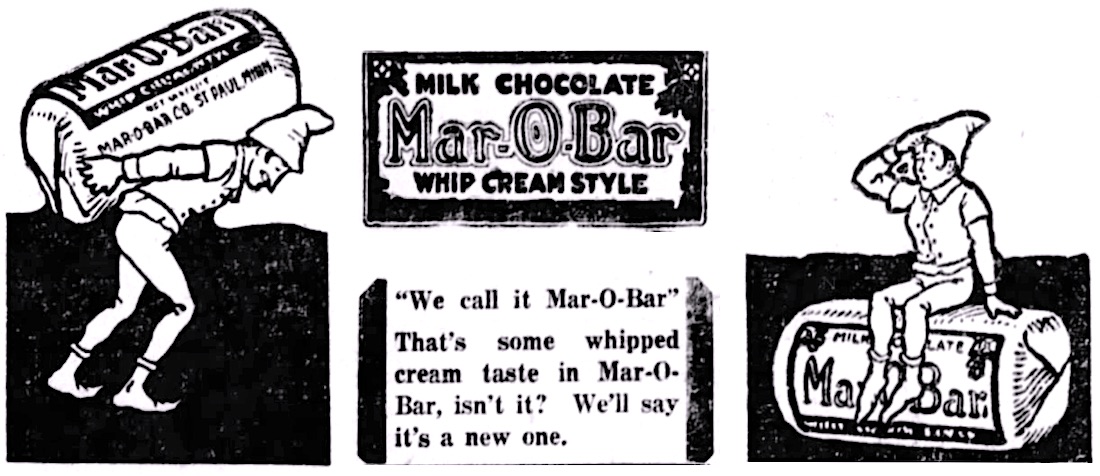

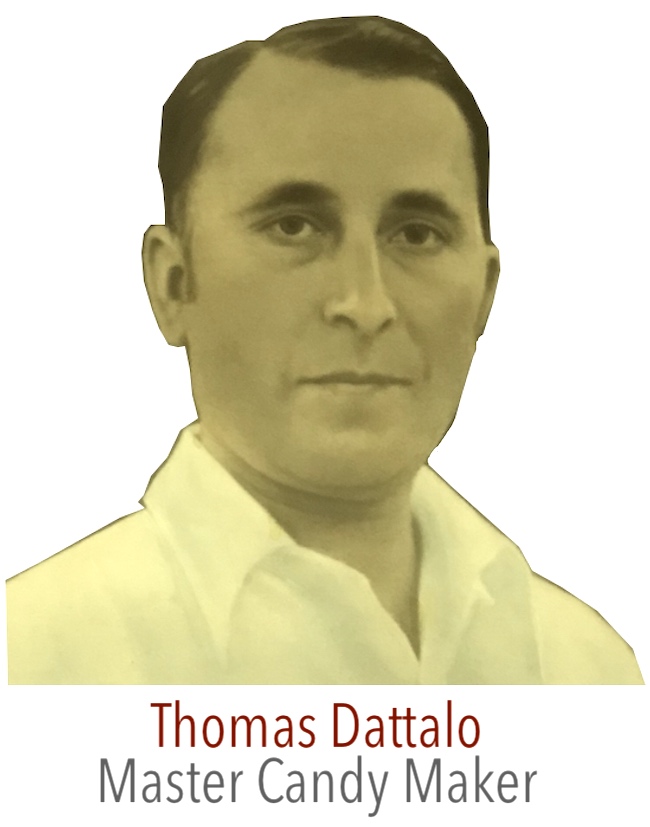

After World War I, the couple moved back east to Minnesota, where Frank started a candy business called “The Nougat House,” with a line of hand-made “Patricia” candies named for his daughter (his only child with Ethel 2). His next big product, the Mar-O-Bar—a “whip cream style” chocolate bar—was introduced in 1920, well timed with America’s emerging post-war candy bar obsession. It did well enough to give Frank his first firm footing in the industry, and he launched the Mar-O-Bar Company in Minneapolis to produce it, hiring a young, skilled Italian-American candy maker named Thomas Dattalo (b. 1895) as his very first full-time employee.

[The “Mar-O-Bar,” Frank Mars’s original chocolate bar, as advertised in 1922]

According to a retrospective in a 1960 edition of the Mars company newsletter, Milky Way News, “business fluctuated daily” at the old Mar-O-Bar Co. “When it was good, it meant long hours of toil. When it was bad it meant money wasn’t always available, and paychecks were by no means certain.” Despite that lack of security, Frank’s righthand man Thomas Dattalo “never thought of quitting. His faith in Mr. Mars was boundless. If ever a young company had a loyal employee, Mars had one in Tom Dattalo.”

The Mar-O-Bar never came close to the sales numbers of Hershey or Curtiss’s Baby Ruth, but it set Frank Mars on a new path; at the age of 40, he’d become a source of inspiration rather than a disappointment. This set the stage for the most important meeting in Mars company history, as a father and his estranged son put aside their differences to hatch a billion dollar idea . . . or so the story goes.

II. Milky Way or the Highway

In 1922, Frank Mars supposedly invited his now 18 year-old son Forrest—a student at Cal-Berkeley—to come to the Twin Cities and discuss the budding “family business.” They hadn’t seen each face to face in years.

In the most colorful but likely apocryphal version of the meeting that followed, dad and son sat down at a local Minneapolis diner and politely chatted over a couple malted milkshakes. Frank brought Forrest up to speed on his new Mar-O-Bar Company and the pros and cons of the Mar-O-Bar itself—how it tasted great, but didn’t transport well over long distances. Forrest, the typical unimpressed teenager, made his own spur-of-the-moment suggestion: Why don’t you make a candy bar version of a malted milk drink?

“I was just saying anything that entered my head,” Forrest Mars later claimed, according to the 1998 book, The Emperors of Chocolate: Inside the Secret World of Hershey and Mars. “And I’ll be damned if a short time afterwards, he has a candy bar. And it’s a chocolate malted drink. He put some caramel on top of it, and some chocolate around it – not very good chocolate, he was buying cheap chocolate – but that damn thing sold. No advertising.”

“I was just saying anything that entered my head,” Forrest Mars later claimed, according to the 1998 book, The Emperors of Chocolate: Inside the Secret World of Hershey and Mars. “And I’ll be damned if a short time afterwards, he has a candy bar. And it’s a chocolate malted drink. He put some caramel on top of it, and some chocolate around it – not very good chocolate, he was buying cheap chocolate – but that damn thing sold. No advertising.”

Roughly 100 years later, the corporate timeline on Mars.com describes the creation of the Milky Way in similar terms: “1923: Father and Son Collaborate and Launch New Candy Bar.”

Left out of this narrative, unfortunately, is the aforementioned Thomas Dattalo, the man Frank Mars often referred to as “the Master Candy Maker.”

According to some of his surviving family members, Dattalo was the true inventor of the Milky Way, along with quite a few other famous Mars confections. “Mars had the money,” Dattalo’s granddaughter Rosanne Eiternick told the Made In Chicago Museum, “my grandfather knew how to make candy.”

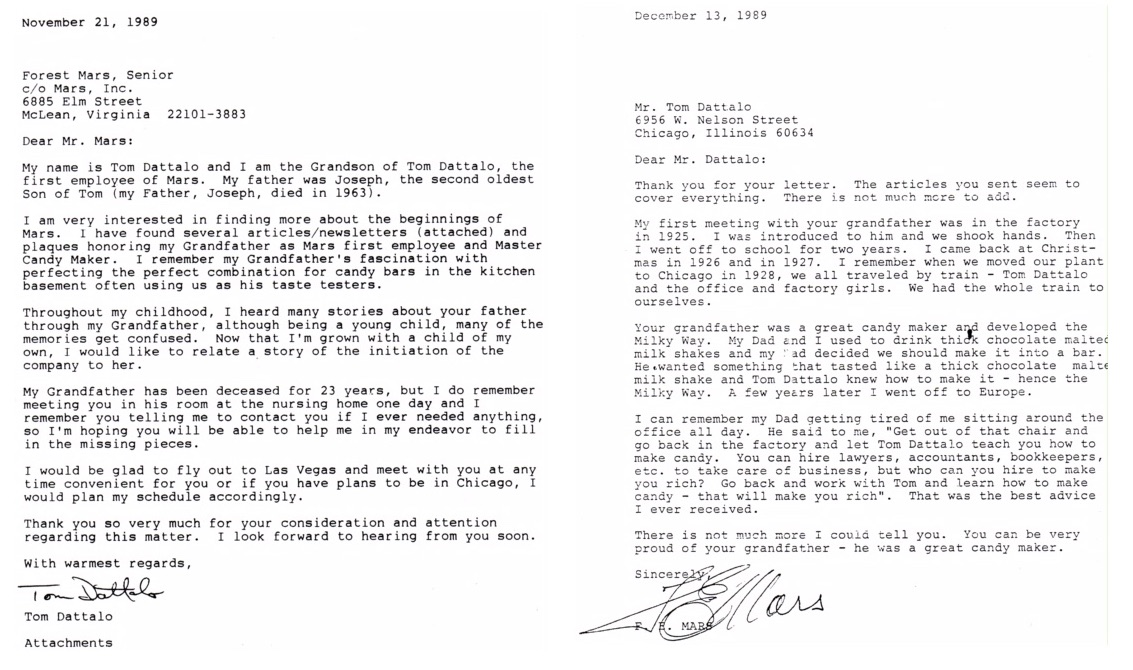

Another of Dattalo’s grandkids, also named Tom Dattalo, sent us some evidence to substantiate these claims—in the form of his own correspondence with Forrest Mars, Sr., back in 1989.

[Correspondence between Tom Dattalo, grandson of Mars’s former Master Candy Maker, and Forrest Mars, Sr., from 1989. These letters have not been officially substantiated, but appear to be legitimate.]

In contrast with the interview he gave in 1966, an elderly Forrest Mars acknowledged in this private letter that the idea for a malted milk candy bar hadn’t come from his own mind; nor had it been a case of random inspiration.

“Your grandfather was a great candy maker and developed the Milky Way,” Mars wrote to Dattalo’s grandson. “My dad and I used to drink thick chocolate malted milk shakes and my dad decided we should make it into a bar. He wanted something that tasted like a thick chocolate malted milk shake and Tom Dattalo knew how to make it; hence the Milky Way.”

Forrest, who was known to be curmudgeonly on his best day, seemed to show a softer side in describing his memories of Dattalo and the early Milky Way days, as well.

Forrest, who was known to be curmudgeonly on his best day, seemed to show a softer side in describing his memories of Dattalo and the early Milky Way days, as well.

“I can remember my dad getting tired of me sitting around the office all day. He said to me, ‘Get out of that chair and go back in the factory and let Tom Dattalo teach you how to make candy. You can hire lawyers, accountants, bookkeepers, etc. to take care of business, but who can you hire to make you rich? Go back and work with Tom and learn how to make candy — that will make you rich.’ That was the best advice I ever received.”

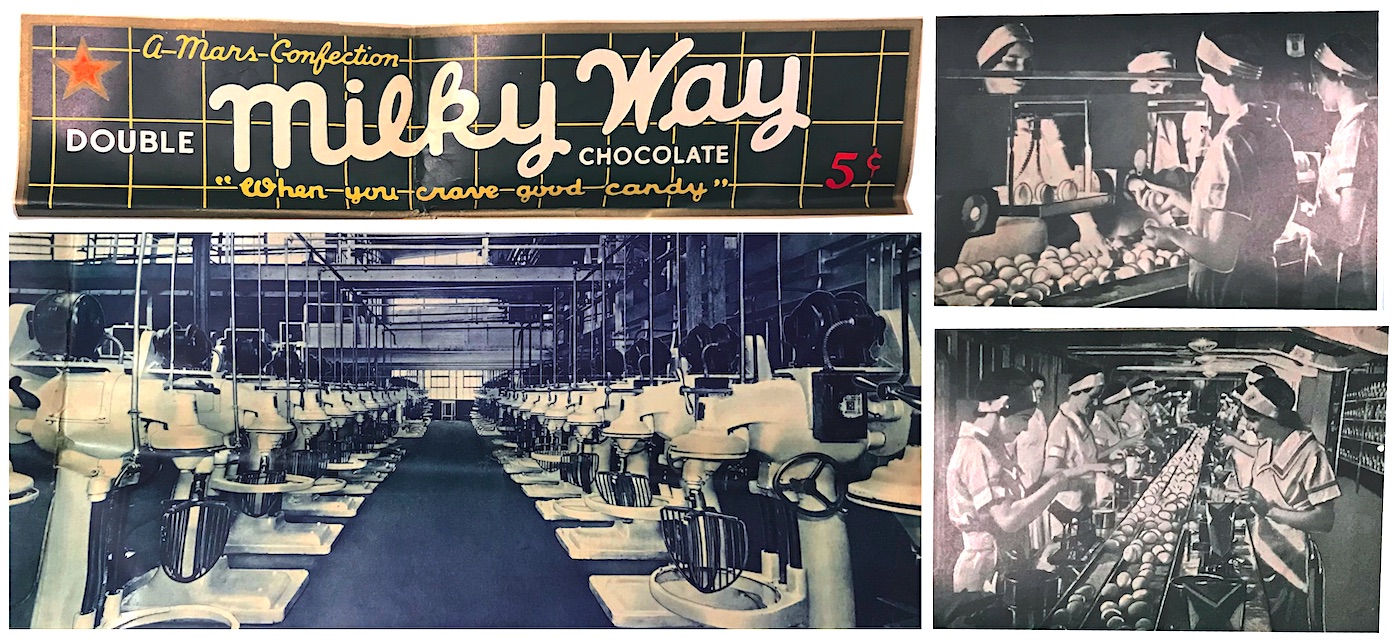

Dattalo’s success in perfecting the malted milk bar vaulted the Mar-O-Bar Company into the big leagues. Cleverly named the “Milky Way” (as a reference to both its malted milk content and Frank Mars’s astronomical surname), the new bar did $800,000 in sales in its first year ($12 million after inflation)—not bad for a 5-cent chunk of chocolate that cost half as much to produce as most of its competitors.

Even the famous Borden Milk Company put out advertisements celebrating their mere association with the Milky Way: “The Mar-O-Bar Company of Minneapolis have capitalized on the popularity of Malted Milk and are using a carload of Borden’s Malted Milk every 15 days in the manufacture of their ‘Milky Way’ Malted Milk Bar,” read a 1924 ad. “There are many other bars on the market but none that has grown in public favor as fast as the Milky Way—whose growth has been phenomenal.”

Milky Way had made Frank Mars a wealthy man, and he wasted no time basking in all the perks that 1920s high society had to offer.

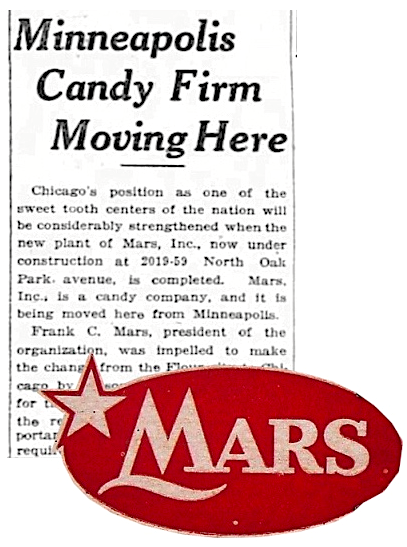

While young Forrest was off studying industrial engineering at Yale, the family business continued to grow, and the Mar-O-Bar Company soon gave way to Mars, Incorporated. Even more importantly, the decision was made to move the factory from Minneapolis to a new building in Chicago, where distribution could be maximized and a cheaper freight rate would save on expenses. Forrest Mars later took credit for this idea, too, suggesting he had to push his reluctant father into pulling up stakes.

III. The Chicago Plant

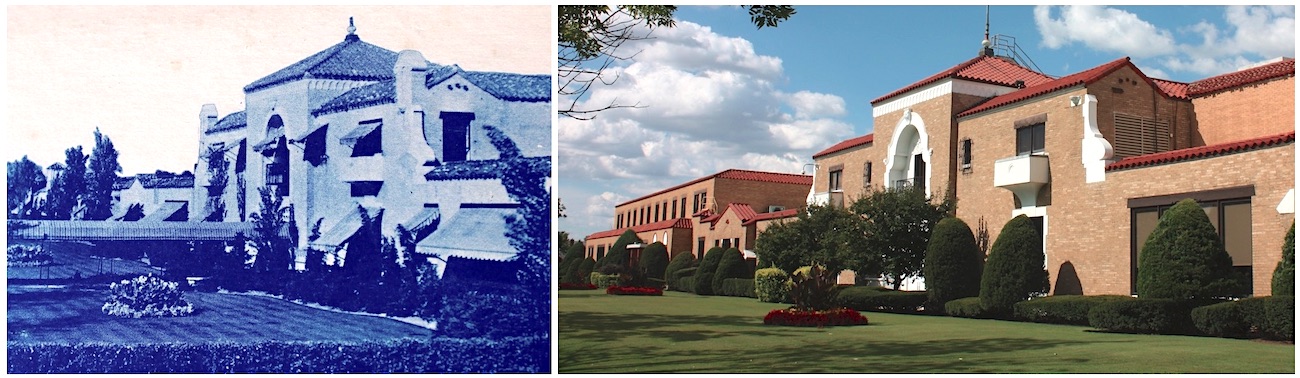

“Chicago’s position as one of the sweet tooth centers of the nation will be considerably strengthened when the new plant of Mars, Inc., now under construction at 2019-59 North Oak Park Avenue, is completed,” the Chicago Tribune reported in 1928.

“Frank C. Mars, president of the organization, was impelled to make the change from the Flour City to Chicago by reason of the facilities here for the shipment of his products and the reception of raw materials—important in the case of candies, which require a quick turnover.”

“Frank C. Mars, president of the organization, was impelled to make the change from the Flour City to Chicago by reason of the facilities here for the shipment of his products and the reception of raw materials—important in the case of candies, which require a quick turnover.”

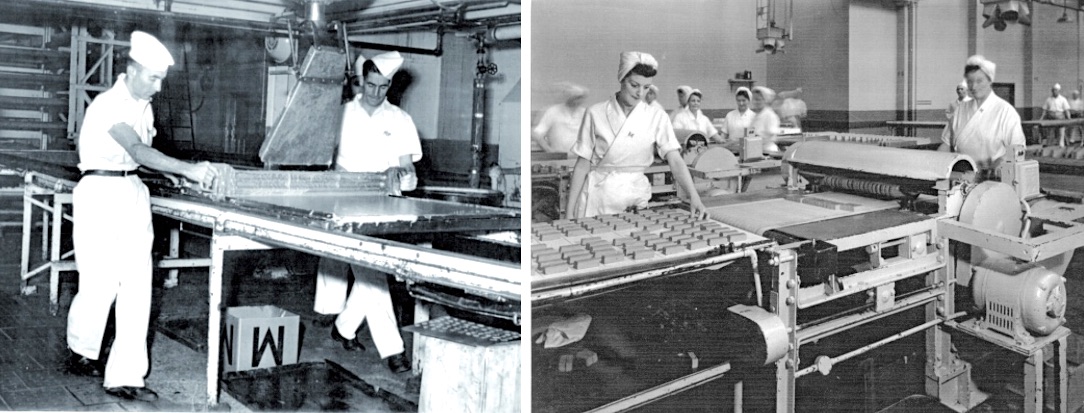

By the end of 1928, a year before the stock market crash would only amplify its comparative opulence, the new Mars factory was completed in Chicago’s Galewood neighborhood. It employed over 300 people at the outset, more than half of whom were existing workers who opted to make the move from Minnesota. Frank Mars coaxed them with the promise of building the “most beautiful” candy plant in America, and by most accounts, he certainly seemed to have a solid claim to the title.

Built on 16 acres of land purchased from the former Westward Ho Golf Club, the Mars factory—which would remain one of the company’s North American Chocolate Division facilities well into the 21st century—was unlike any other manufacturing plant of its time, or any time since, really.

Chicago Tribune reporter Al Chase summed up the factory on the occasion of its 25th anniversary in 1953. At the time, it still purported to be the largest candy plant in the world.

[The Mars candy factory at 2019 N. Oak Park Ave., 1950s and present day. Mars ads often noted that all ingredients were prepared in the company’s “modern, sunlit candy kitchens.”]

[The Mars candy factory at 2019 N. Oak Park Ave., 1950s and present day. Mars ads often noted that all ingredients were prepared in the company’s “modern, sunlit candy kitchens.”]

“The Spanish type structure is an outstanding bit of architecture, and it stands in a beautiful setting of brilliant green bent grass, beds of flowers, shrubs, and towering trees,” Chase wrote.

“A casual passersby who didn’t know what it was probably would think it a fashionable club or some important institution—never a factory. The tinted walls, rich red tile roofs, two-story high curved top windows, and a long canopy extending 100 feet or more from the main entrance to the sidewalk, give no hint of manufacturing activities.

“Even after one steps through wide, inviting doors into the big, high ceilinged lobby, the illusion of ease instead of labor persists. Fine oil paintings are hanging on throughout the general offices. Oriental rugs are scattered about. Except for the sound of assembly line production sifting through from the manufacturing area, one still never would guess it was part of a manufacturing plant.”

[Inside the Mars Chicago plant in the 1930s. Left: A battery of beaters whips egg whites with sweet syrup for the centers of 3 Musketeers bars. Right: Inspecting eggs (top) and breaking eggs (below) for use in the Milky Way]

Frank and Ethel 2 weren’t just spending their Milky Way money on swank factory features, either. Unlike the generations that would follow them, these Martians had no shame about visibly waving their wealth flags.

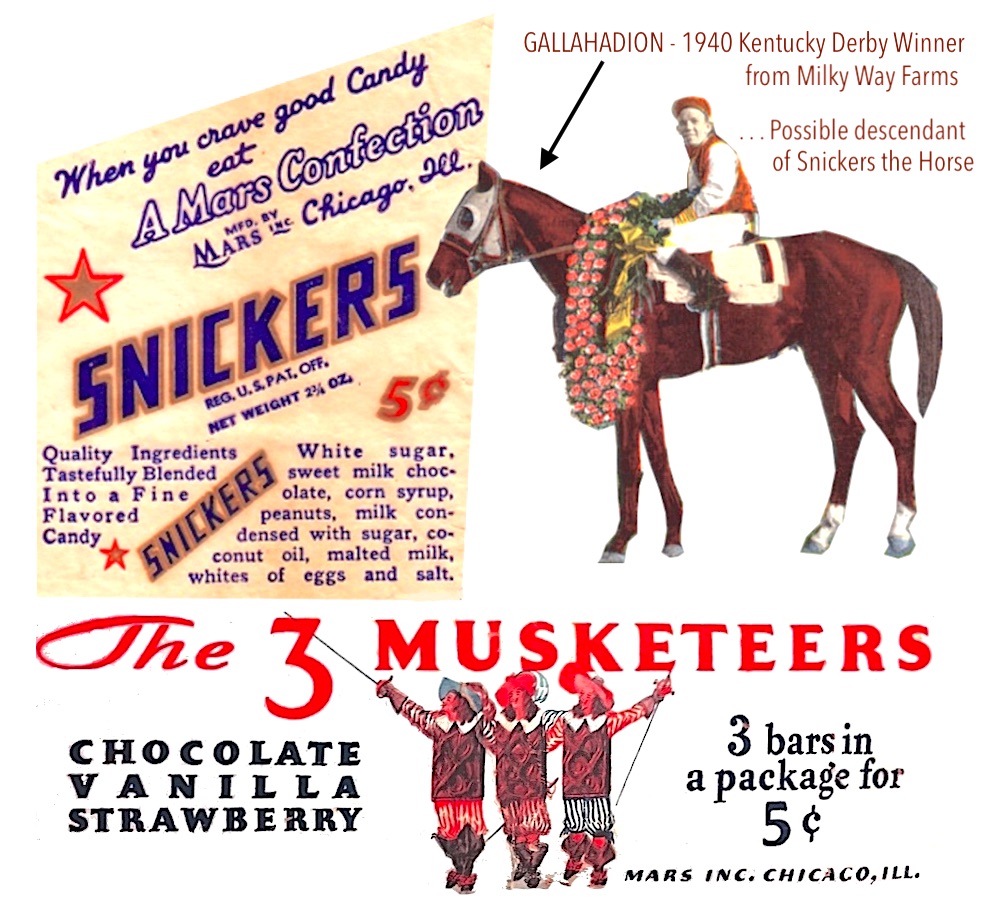

Depression be damned, Chicago’s new candy power couple purchased themselves a Duesenberg town car worth $20,000 (a ridiculous $300,000 in modern cash) and were gleefully chauffeured near and far, from the factory grounds to as far north as their new palatial estate in Minocqua, Wisconsin. Like many of the other leading Chicago tycoons of the period, Frank Mars also jumped into the ranching and horse breeding game, employing 100 people to run his nearly 3,000 acre “Milky Way Farms” in Tennessee. Ethel Mars kept the ranch going after Frank’s death, and eventually got a Kentucky Derby champ out of the effort, the 1940 winner Gallahadion.

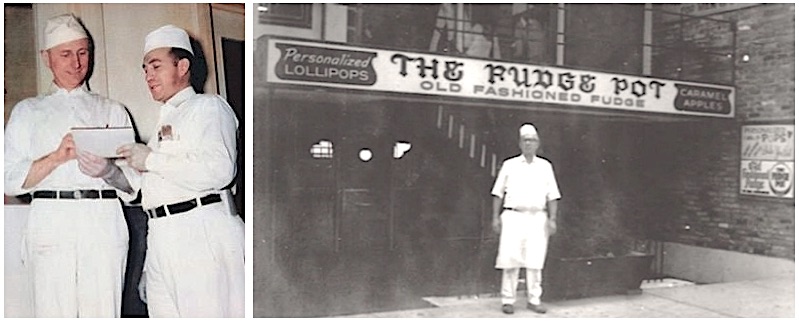

With his fortune made, Frank seemed to lose a bit of his motivation when it came to the confectionery arts. That responsibility was largely left in the hands of the ever reliable Tom Dattalo, whose family now lived in a house that Frank had bought for them on Oak Park Avenue, just down the road from the Chicago plant.

“When operations were moved from Minneapolis to Chicago, Tom [Dattalo] came with the company,” according to a 1960 edition of the Milky Way News. “With the change came increased responsibilities. Three shifts of candy making required Tom to get up around 4:00 or 5:00 a.m. to oversee the end of the third shift operations. It required him to stay through the day and supervise the beginning of the second shift operations. This would keep him on the job until 6:00 or 7:00 p.m. Also for many years Tom came to work on Saturday and Sunday.”

While Thomas Dattalo ran the candy lab, his nephew James Dattalo got into the business helping the landscaping crew on the factory grounds, before gradually getting his daily lessons on all aspects of the confectionery trade. Years later, in 1963, James would open up his own candy shop in Old Town, the Fudge Pot, which is still in business today, operated by James’s son, Dave Dattalo.

[Left: Former Mars chief candy engineer Tom Dattalo with his son Jim, 1940s. Right: Jim Dattalo standing outside his own business, the Fudge Pot on Wells Street, 1960s]

[Left: Former Mars chief candy engineer Tom Dattalo with his son Jim, 1940s. Right: Jim Dattalo standing outside his own business, the Fudge Pot on Wells Street, 1960s]

Such endearing tales of generational succession only seem more quaint when compared to the mess that was the Mars family dynamic.

Case in point, the very same year that Frank Mars opened up the new Chicago factory/resort, an unexpected new employee also re-joined the fold—the fresh Yale graduate Forrest Mars. I suppose it’s certainly possible that both father and son were genuinely committed to finally patching up their tenuous relationship and working together for the good of the family. It’s also possible that Forrest saw a lucrative opportunity to dive straight into the deep end of corporate America, using nepotism or fatherly guilt as his bridge. Either way, things were never destined to go smoothly.

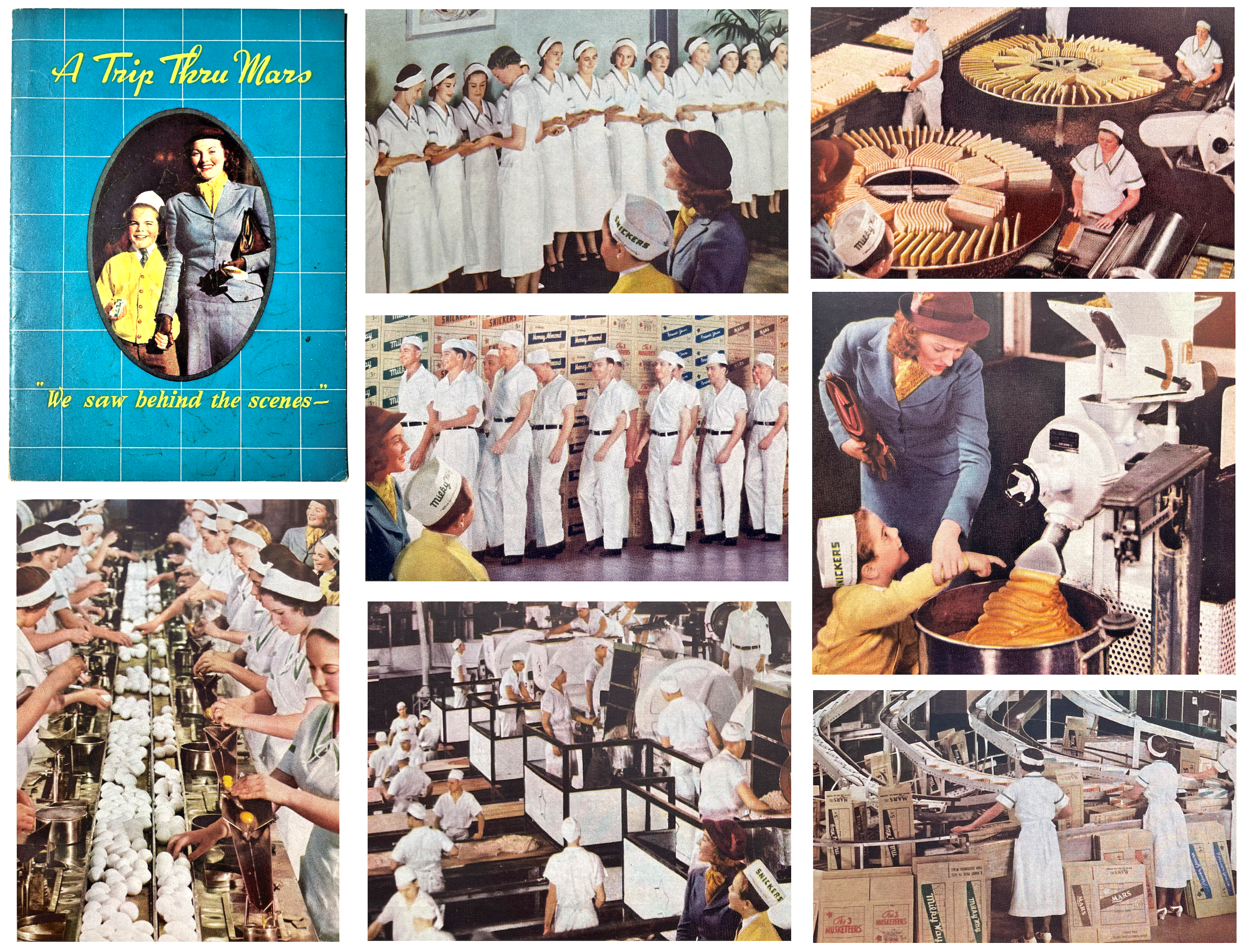

[Images from a 1938 promotional booklet called “A Trip Thru Mars,” showing how public tours of the N. Oak Park Avenue factory used to be commonplace, and even a key means of marketing. “We have about 40,000 visitors a year,” the booklet reads, “mostly from Chicago and nearby towns. And our greatest sales increases have come from nearby, where more people have seen how the candy is made in our plant.”]

IV: Mars vs Mars

“If you like peanuts and chocolate too, then Snick-Snick-Snickers is the bar for you!” –Mars advertising jingle, 1950s

Right off the bat, the new Mars partnership was faced with the brutal uncertainty of the market crash and the threat of a total economic depression. To make matters worse, Frank’s old-school solutions for keeping the business afloat bared little resemblance to Forrest’s fresh Ivy League sensibilities and militant preference for efficiency over “beauty.”

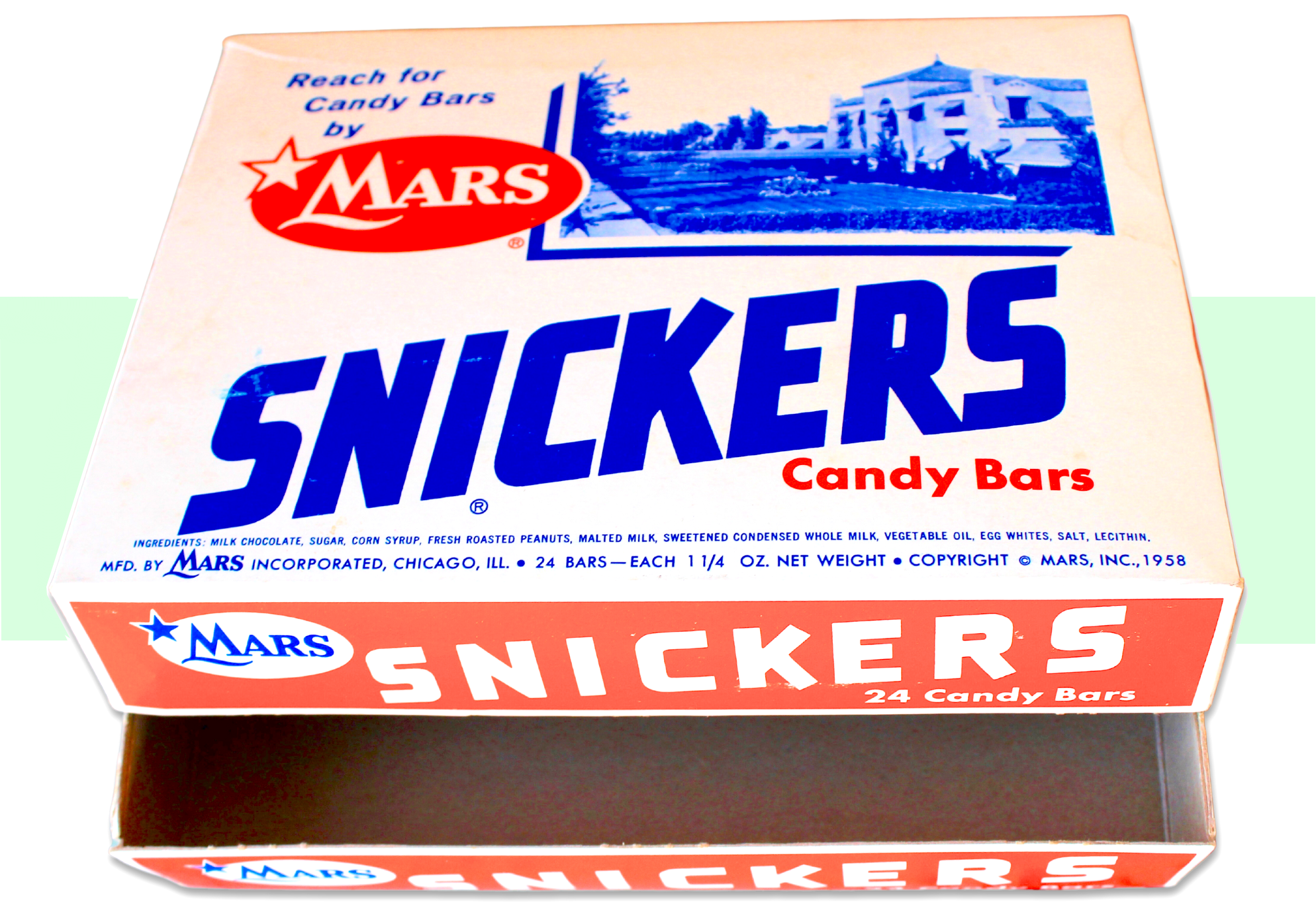

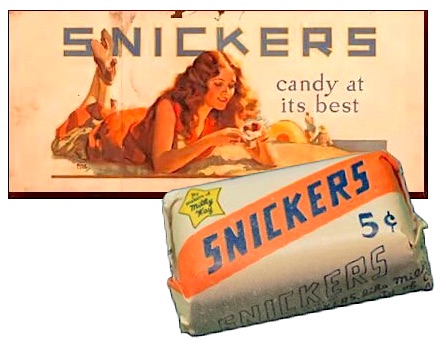

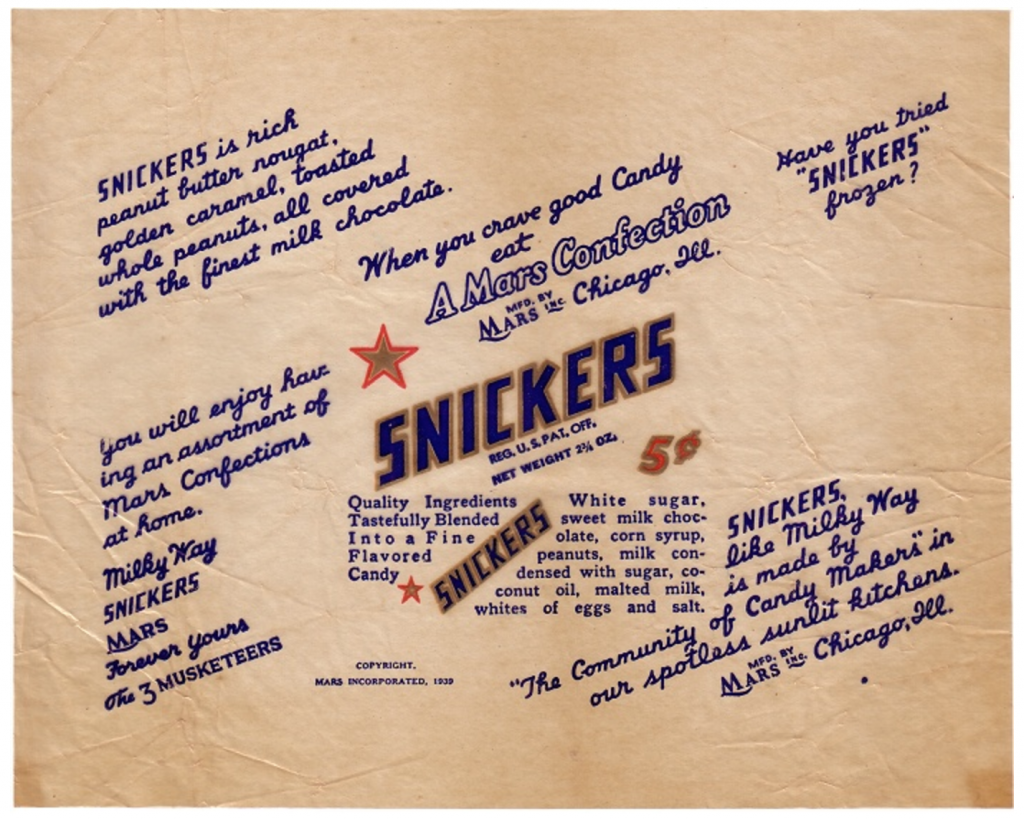

The duo managed to do a few things right during this tumultuous period, including the launch of two major new candy bar successes: Snickers (1930) and Three Musketeers (1932).

The duo managed to do a few things right during this tumultuous period, including the launch of two major new candy bar successes: Snickers (1930) and Three Musketeers (1932).

The Snickers Bar, which was named after one of Frank and Ethel Mars’s prized race horses, was also likely a Tom Dattalo concoction. The recipe essentially just added peanuts to the Milky Way blueprint, but the change was enough to distinguish Snickers as its own thing and eventually turn it into one of the best selling candies of all time.

The 3 Musketeers bar, meanwhile, was so named because the original design included three separate pieces—one vanilla, one strawberry, and one chocolate, with whipped mousse on the inside. Restrictions during WWII eventually cut the production down to just the chocolate version, and so it would stay.

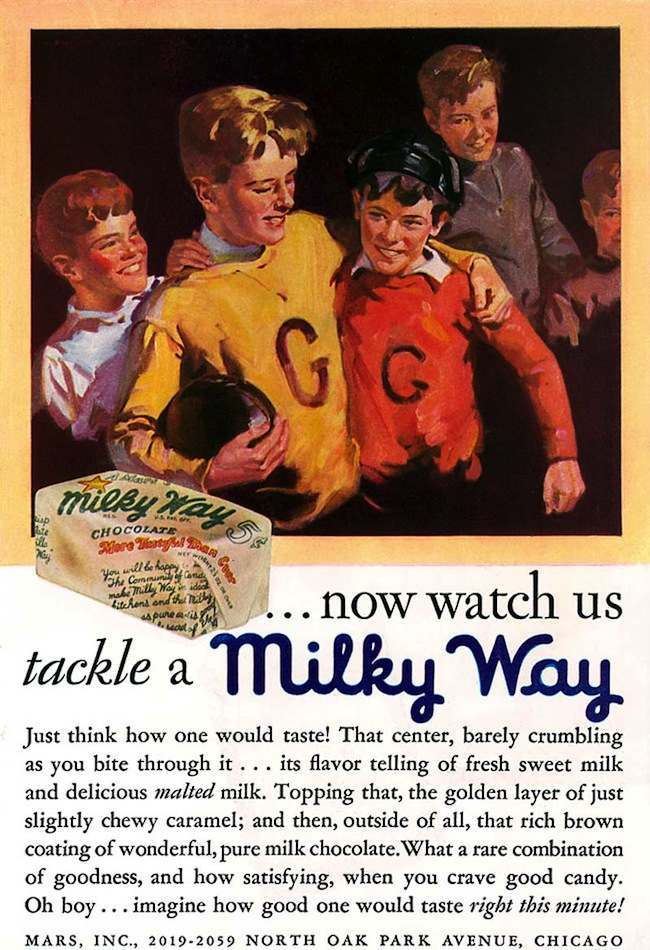

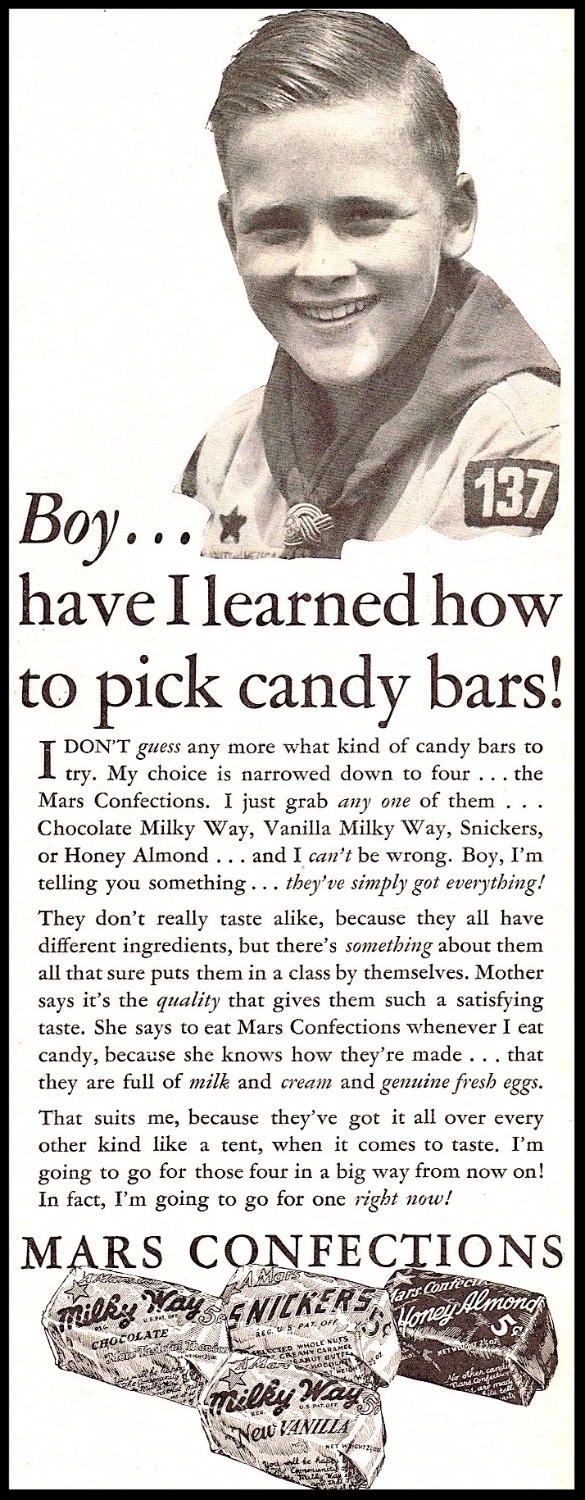

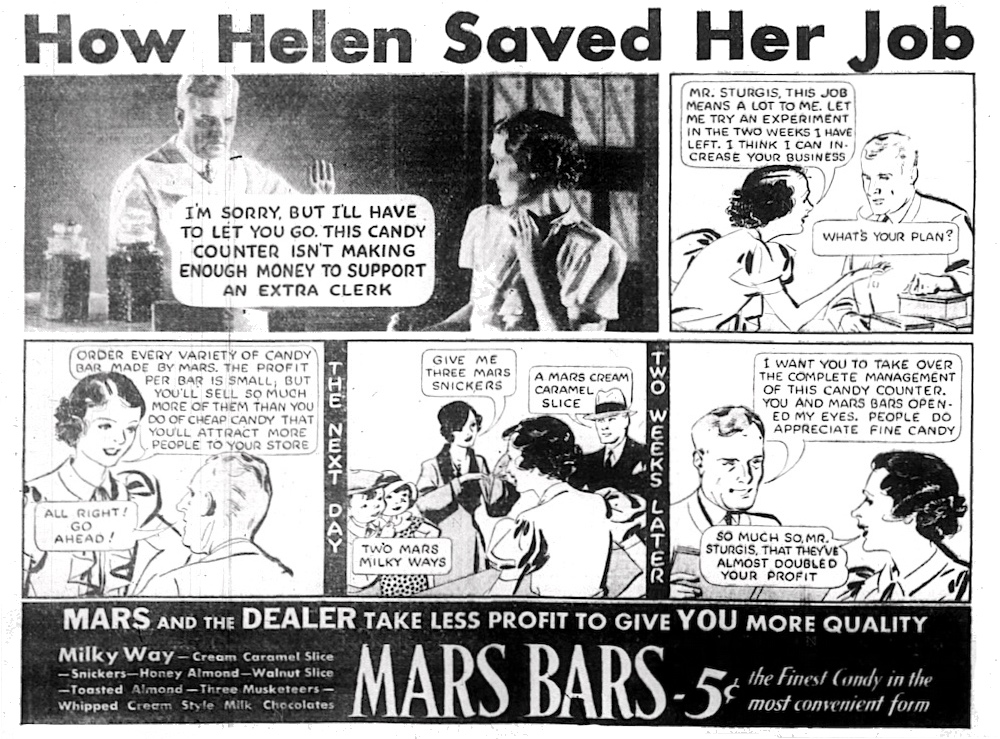

There wasn’t a great deal of focus on individually advertising the Snickers or 3 Musketeers in their early years. By the time Mars Inc. was sending out display boxes like the one in our museum collection (1958), however, these slickly branded bars had achieved stardom through a new sort of marketing medium—TV commercials. This meant you wouldn’t just be daydreaming about candy bars, you’d be singing about them, too.

[Snickers TV commercial from 1954]

Anyway, despite a productive first few years in Chicago, it soon became clear that Frank and Forrest Mars wouldn’t be able to peacefully co-exist much longer, and that the heir to the Mars throne might not be destined for the role. After challenging his father relentlessly about the best way to run the business—and demanding ownership of one-third of Mars Inc. for himself—Forrest finally pushed one button too many in 1932.

“This company isn’t big enough for the both of us,” Frank Mars supposedly told his son (an oft-cited quote that seems far too theatrical to be real). “Go to some other country and start your own business!”

“This company isn’t big enough for the both of us,” Frank Mars supposedly told his son (an oft-cited quote that seems far too theatrical to be real). “Go to some other country and start your own business!”

If Frank Mars really did say this, it seems doubly insensitive, considering it’d mark the second time he’d essentially banished his son to a foreign land. This time around, however, Forrest Mars was more than prepared to take on the challenge.

“Things got bitter,” Forrest recalled in video recording made for the Mars family archives, which was later quoted in the aforementioned Emperors of Chocolate book in 1998. “I’m not proud of this. I told my dad to stick the business up his ass. If he didn’t want to give me one-third right then, I said I’m leaving. He said leave, so I left.”

Forrest forgot to mention that he also had a wife, Audrey, and a young child, Forrest Jr., at the time. So, technically, he should have said “we left.” But anyway, the destination was England. And thus the alternative / bizarro / thoroughly British version of Mars Candy was about to be let loose upon the world.

[Factory workers at the Mars candy plant in Slough, England, c. 1940s]

[Factory workers at the Mars candy plant in Slough, England, c. 1940s]

V. Is There Life On Mars (or in Britain)?

Yes, the simplest way to explain why the “Mars Bar” is so much more prominent in the UK, or why Snickers went by another name for decades, is that there were, essentially, two separate Mars companies in operation during much of the 20th century.

Way back in 1932, Forrest Mars Sr.—essentially kicked out of America for being a wise ass—was given a couple parting gifts by his papa on the way to the airport: $50,000 in cash and the patent rights to sell the Milky Way bar formula in Great Britain. Frank Mars might not have seen eye to eye with his kid, but he clearly respected Forrest’s skills and potential as a businessman. The banishment, perhaps, was his version of a helpful kick in the pants (or trousers, if we’re keeping with appropriate UK terminology)

Way back in 1932, Forrest Mars Sr.—essentially kicked out of America for being a wise ass—was given a couple parting gifts by his papa on the way to the airport: $50,000 in cash and the patent rights to sell the Milky Way bar formula in Great Britain. Frank Mars might not have seen eye to eye with his kid, but he clearly respected Forrest’s skills and potential as a businessman. The banishment, perhaps, was his version of a helpful kick in the pants (or trousers, if we’re keeping with appropriate UK terminology)

Noting the preferences of British candy lovers, Forrest got started by tweaking the original Milky Way formula to add a little extra sweetness. He called his creation the “Mars Bar,” and introduced it to the UK market in 1932. Production was initially based out of a small factory in the city of Slough (home of the Wernham Hogg Paper Company in The Office), employing just the 12 people he could afford with his dad’s financial aid. When the Mars Bar proved every bit as popular with the Brits as the Milky Way was with the Yanks, however, Forrest suddenly was the well-to-do captain of his own substantial organization—still shy of his 30th birthday, but already taking orders from nobody.

One one hand, the young ex-pat mogul was achieving a stunning level of success in the midst of the Great Depression. Unfortunately, Forrest was also fueling himself on a sort of maniacal urge to outdo his father (or some other inner demons), and he began running an increasingly tight ship at his UK factory, often lashing out at employees for the slightest misstep.

Then, just two years into his time in England, Forrest got word from back home. Frank Mars was dead at the age of 52.

No one can know for sure how Forrest processed the news, but it’s believed he didn’t bother flying home for the funeral. He also soon learned that his father had left the majority of Mars Inc. in the hands of his second wife, Ethel V. Mars, along with their daughter Patricia. The father-son war, it turned out, couldn’t even end in death.

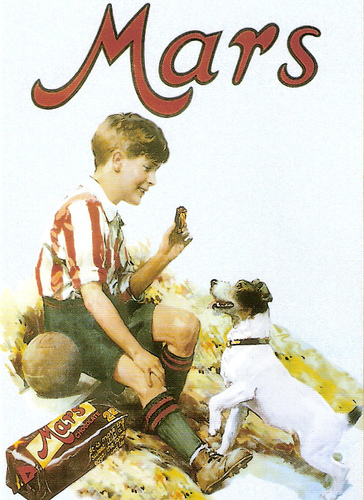

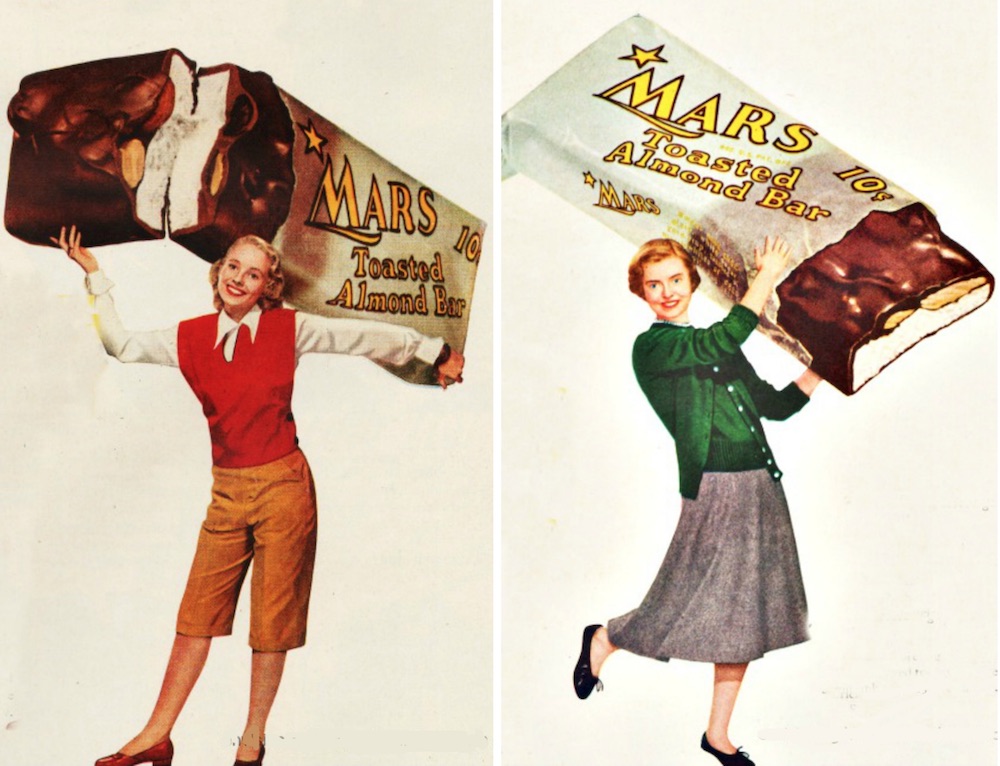

[In 1936, two years after Frank Mars’s death, Mars Inc. in Chicago debuted its own “Mars Bar,” featuring toasted almonds—a totally different formula from the Mars Bar that Forrest Mars was selling in the UK. The cross-Atlantic confusion had officially begun.]

[In 1936, two years after Frank Mars’s death, Mars Inc. in Chicago debuted its own “Mars Bar,” featuring toasted almonds—a totally different formula from the Mars Bar that Forrest Mars was selling in the UK. The cross-Atlantic confusion had officially begun.]

VI: “Not In Your Hand”

It would take another three decades for Forrest Mars to finally reclaim what he believed to be his birthright—total ownership of Mars Incorporated USA. In the meantime, though, he managed to build a global company (eventually known as Food Manufacturers Inc.) that actually outclassed the American Mars mothership in nearly every department, particularly during the 1940s.

It was Forrest who hatched the idea for Uncle Ben’s rice. It was Forrest who revolutionized packaged pet food in an era when most families still fed their cats and dogs table scraps. And it was Forrest who went into business with Bruce Murrie, son of the Hershey Company president, to create a new type of miniature round chocolates with a hard candy shell coating—something designed as a convenient snack for American soldiers during WWII (an answer to the “Smarties” he saw British troops enjoying). Known as the M&M—short for “Mars and Murrie”— this candy is the recognized flagship brand of Mars Incorporated today, but when they were introduced to the wider public in 1945, M&Ms were a product of an independent venture called M&M Ltd. It would be another 20 years before they’d find their way into the original Mars candy “family.”

It was Forrest who hatched the idea for Uncle Ben’s rice. It was Forrest who revolutionized packaged pet food in an era when most families still fed their cats and dogs table scraps. And it was Forrest who went into business with Bruce Murrie, son of the Hershey Company president, to create a new type of miniature round chocolates with a hard candy shell coating—something designed as a convenient snack for American soldiers during WWII (an answer to the “Smarties” he saw British troops enjoying). Known as the M&M—short for “Mars and Murrie”— this candy is the recognized flagship brand of Mars Incorporated today, but when they were introduced to the wider public in 1945, M&Ms were a product of an independent venture called M&M Ltd. It would be another 20 years before they’d find their way into the original Mars candy “family.”

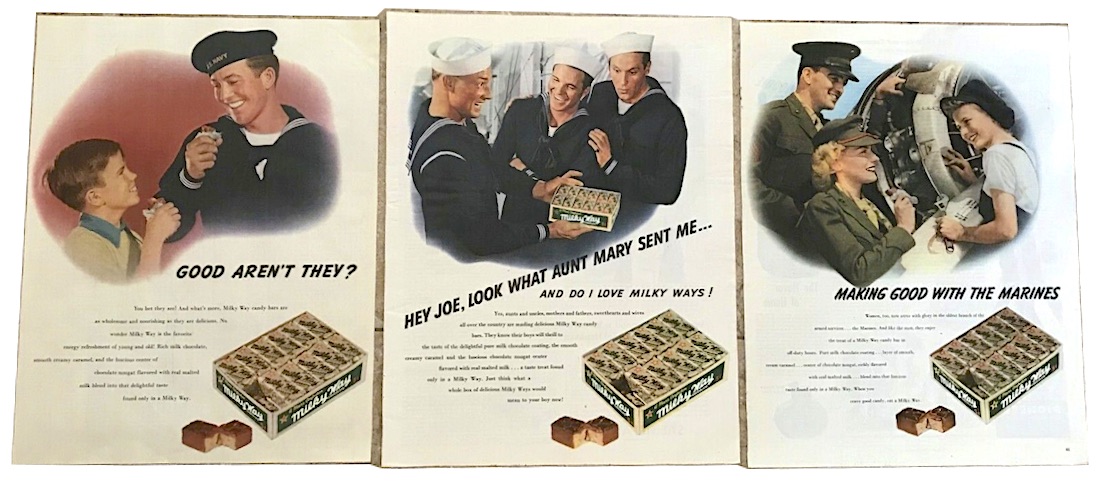

In that sense, then, the Chicago-Mars story in the years after Frank Mars’s death is one of comparative stagnation. In the ’40s, while Forrest was breaking back into the U.S. market producing M&Ms in New Jersey and Uncle Ben’s in Texas, the old Mars Inc. plant in Chicago was merely holding steady—selling the same marquee candy bars with little expansion.

Even after the death of Ethel V. Mars in 1945, Forrest Mars remained just a minority owner in his father’s company, as his half-sister Patricia held the power. Patricia, in turn, decided to leave her uncle William Kruppenbacher as CEO of Mars Inc., fanning the flames of Forrest’s rage all the more.

[The Mars factory in Chicago continued producing chocolate bars during WWII, with many of them shipped overseas for the troops]

“Slip,” as Kruppenbacher was known to colleagues, was a capable businessman himself, and he did guide the company through much of the Depression and the war, with employment at the Chicago plant growing to over 2,000 workers by 1950. Recognizing the benefits of cross-promotion and new modes of advertising, Kruppenbacher took some bold steps in that arena, too, including a Mars sponsorship of what would become one of the country’s most popular radio and TV quiz shows, “Dr. IQ.”

Unfortunately for Kruppenbacher, he also spent much of the ‘40s and ‘50s dealing with the looming presence of Forrest Mars—who remained hell bent on taking over his dad’s company. Even when the profits of Food Manufacturers Inc. surpassed that of Mars Inc. in the early 1950s, Forrest was never swayed from his ultimate goal. It was clearly a matter of principles, and with his minority stake and seat on the board, Forrest took advantage of every opportunity to hound Kruppenbacher and push his own ideas on how Mars Inc. should be run. He even had his own office in the Chicago plant, allowing him to see the day-to-day of the company’s operations firsthand, looming over old loyalists of his dad like chief candy maker Thomas Dattalo.

Unfortunately for Kruppenbacher, he also spent much of the ‘40s and ‘50s dealing with the looming presence of Forrest Mars—who remained hell bent on taking over his dad’s company. Even when the profits of Food Manufacturers Inc. surpassed that of Mars Inc. in the early 1950s, Forrest was never swayed from his ultimate goal. It was clearly a matter of principles, and with his minority stake and seat on the board, Forrest took advantage of every opportunity to hound Kruppenbacher and push his own ideas on how Mars Inc. should be run. He even had his own office in the Chicago plant, allowing him to see the day-to-day of the company’s operations firsthand, looming over old loyalists of his dad like chief candy maker Thomas Dattalo.

“When Forrest Mars came back,” Dattallo’s grandaughter Rosanne Eiternick says, “he claimed all the rights of the candy making and closed off all the information towards the history of the company. . . . We feel our grandfather got the raw deal.”

As the power struggle waged on, Forrest Mars Sr. seemed to have less and less patience with the people around him, no matter which plant he was stalking. In her book The Emperors of Chocolate, author Joël Glenn Brenner describes the increasingly gloomy atmosphere at the M&M factory in New Jersey, where Forrest had long since run his old business partner Murrie out of town.

“Explosive fits of screaming and cursing pierced the order of the factory floor several times a day. It seemed anything could set [Mars] off when he arrived at the factory. An employee who forgot to wash his hands, a messy pile of papers on a salesman’s desk, or a speck of chocolate on a uniform could send him reeling into an abusive rage. Most workers eventually learned to shrug off these episodes, waiting patiently with heads bowed until the blood rushed out of Forrest’s face and the taunts and name-calling ceased, almost as abruptly as they had begun.”

According to one former employee, Forrest Sr. “treated everybody in the world like they were stupid—except him.”

[Mars CEO William Kruppenbacher, second from right, checking out some new machinery in the Mars plant in 1959. He’d quit his post shortly thereafter.]

[Mars CEO William Kruppenbacher, second from right, checking out some new machinery in the Mars plant in 1959. He’d quit his post shortly thereafter.]

Kruppenbacher, like Murrie and Dattalo before him, finally had enough in 1959, retiring and leaving the CEO position to Patricia Mars’s third husband, James Fleming. It soon became clear, however, that Fleming was out of his element. Mars Inc. started going in the wrong direction.

With few other obvious candidates waiting in the wings, and Patricia herself diagnosed with cancer, the unavoidable moment had finally arrived. Forrest Mars bought out the remaining stock and became the new president and CEO of Frank Mars’s old candy company in 1964, simultaneously merging Food Manufacturers Inc. and its properties under the Mars name, as well. There was now one and only one Mars Inc., worldwide.

The friendly corporate version of events might make it sound like a proud legacy was merely carrying on through the family line, but it’s worth emphasizing that Forrest Mars Sr. had to buy Mars Inc. rather than inherit it. And while he did bring his own sons into the business, those relationships proved no warmer than the one he’s experienced with his own dad.

VII: Forrest for the Trees

One might have hoped that Forrest Mars Sr. would have found some peace by the age of 60. But he had no intentions of celebrating his hard fought victory by letting Mars Inc. carry on as it had for the past 40 years. His arrival at the Chicago factory as the company’s new CEO became the stuff of legend.

Here’s how Fortune magazine recounted the event several years later in a 1967 company profile:

“[Forrest] Mars did not just walk into the room; he charged in. His ring of hair was gray around his gleaming scalp, but he still had the athletic stance of a much younger man. He wore an English suit with wide lapels, and his tie was unstylishly wider still. ‘We didn’t know if he was ahead of the times, or behind,’ recalls a participant. After a few quips, which sparked a little dutiful laughter, Mars talked of his plans and hopes for the Mars Candies Division, as the Chicago operation was henceforth to be known. He paused. ‘I’m a religious man,’ he said abruptly (he’s an Episcopalian). There was another long pause, while his new associates pondered the significance of his statement. Their mystification increased when Mars sank to his knees at the head of the long conference table. Some of those present thought that he was groping on the floor for a pencil that had slipped from his hands. From his semi-kneeling position, Mars began a strange litany: ‘I pray for Milky Way. I pray for Snickers…’ “

It was immediately clear to the Chicago workers that it wasn’t going to be business as usual from that point forward. But that wasn’t necessarily a bad thing.

While Forrest Mars spent much of his first year eliminating some of the fancier and cuddlier elements of the Chicago plant and offices—goodbye, stained glass windows, wall paintings, executive dining room, PR events, etc.—he didn’t forget to appease his employees in other ways. Salaries were raised for workers at all levels, and benefits and bonuses were improved. The factory was kept cleaner and made more efficient by the installation of new machines and technology, and all employees—regardless of their position—ate lunches together and punched the same clock.

[“American Dairy Princess” Bonnie Sue Houghtaling tours the Chicago Mars Candy plant in 1961, guided by factory superintendent Donald McDonald (center). Tours like this were virtually eliminated once Forrest Mars took over the company in 1964]

[“American Dairy Princess” Bonnie Sue Houghtaling tours the Chicago Mars Candy plant in 1961, guided by factory superintendent Donald McDonald (center). Tours like this were virtually eliminated once Forrest Mars took over the company in 1964]

It wasn’t necessarily that Forrest was more compassionate than his predecessors. As the Fortune article noted, it was simply about “applying mathematics to economic problems.” With good wages and benefit programs, the hardline conservative Mars was able to bust unions and keep Mars Inc. free of labor movement rumblings. And by keeping everyone on the same level in the factory ecosystem, the management team would never rest on its laurels either.

As no surprise to Mars himself, the changes paid off.

With the Mars Inc. world headquarters now located in suburban Washington D.C. (and Chicago serving as a candy bar hub), Forrest Sr. started focusing on expanding factory development in Europe during the 1960s, to great effect. In the U.S., the Hershey Company, as always, remained the primary competition in the chocolate business. But by producing its own chocolate and peanuts completely in-house for the first time, Mars Inc. was able to cut costs and move past its Pennsylvania rival for the majority of the years to come.

Meanwhile, most of America’s smaller candy makers were disappearing or merging to try and hold onto any niche in the market they could. In 1965 alone, three of Mars Inc.’s old Chicago contemporaries were purchased by larger corporations—Williamson Candy (by Warner-Lambert Pharmaceutical), E.J. Brach & Sons (by American Home Products), and Reed Candy Co. (by P. Lorillard). With fading competition and the power of M&Ms, Snickers, Milky Way, and 3 Musketeers—all top ten sellers in the industry—Mars became the undisputed mega-power in confections.

And yet . . . as ever, Forrest Mars Sr. was a deeply dissatisfied man.

VIII: Mars Attacks

In the late 1960s, as his sons Forrest Jr. and John Mars took on larger roles in the company, employees described very tense relationships between the three men, with Forrest Sr. often berating his children much as he did the workers at the M&M plant years earlier.

According to one former Mars worker, Forrest Mars Sr. “was terrible” to his sons. “He would shout and call them dumb and stupid. He would harangue them over the smallest detail. Everyone in the room would fall silent, and you could hear him screaming all the way into the factory. It was horribly embarrassing.”

According to one former Mars worker, Forrest Mars Sr. “was terrible” to his sons. “He would shout and call them dumb and stupid. He would harangue them over the smallest detail. Everyone in the room would fall silent, and you could hear him screaming all the way into the factory. It was horribly embarrassing.”

A Mars profile in a 2001 issue of Biography Today further describes a moment during a 1964 company meeting when Forrest Sr. angrily ordered one of his sons “to kneel on the floor and pray for the future of the company. He then resumed the meeting, leaving the young man to kneel silently on the floor for an hour in front of his co-workers. The son reportedly rose to his feet only after his father called an end to the meeting and walked out of the conference room.”

Forrest Mars Sr. had also developed a deep distrust of people and increasingly refused to share any information about himself or his company. Some believe the attitude dated back to the 1940s, when a magazine article about his company’s success with Uncle Ben’s Rice led to the U.S. government asking Mars for the recipe (they were hoping to duplicate it for military use). If you reveal details about your products, he now believed, it only opened the door to others taking advantage of you.

Even in 1966, when Mars finally agreed to do a rare interview with Candy Industry and Confectioner’s Journal, he reportedly was so furious about being misquoted in the article that he wrote off all media contact for his family AND Mars employees from that point forward.

The madness of King Mars didn’t conclude with his retirement from the company in 1973. Instead, he proved unwilling to completely walk away from the multi-billion dollar machine he’d engineered for so long. When his sons finally refused to deal with him any further, Mars Sr. started a new candy business, Ethel M Chocolates (named for his mother, Frank Mars’s first wife Ethel G. Mars), in Henderson, Nevada.

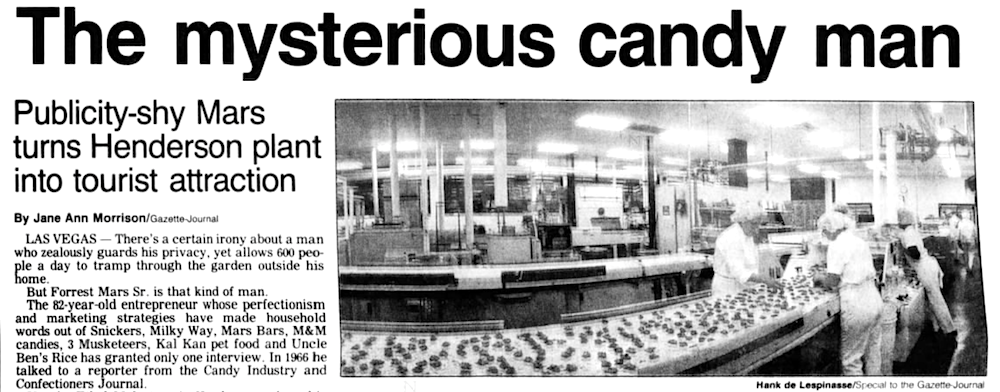

[Headline from a story on Forrest Mars Sr. and Ethel M from the Reno-Gazette Journal, Oct 20, 1986]

Throughout the 1980s, Forrest Sr. not only went to work everyday at the Ethel M factory, he lived there—an elderly man staring down on his factory employees from a penthouse office with one-way glass windows. They came to call him the “Phantom of the Candy Factory.” In a complete reversal from his old philosophy, Mars also wanted the Ethel M plant run as a tourist attraction to draw more revenue. Its lavish gardens, not unlike those maintained back at the Oak Park Avenue plant in Chicago, welcomed thousands every year—not that any guest ever caught a glimpse of the phantom.

In 1990, shortly after the death of his wife Audrey, Forrest Sr. sold Ethel M to his children at Mars Inc.—including his daughter Jacqueline, who had joined the family business. All of them were billionaires and among the 50 wealthiest Americans. But, like the generation before, money had not been enough to heal old wounds.

Mars Inc. refused to share any information about Forrest Mars Sr. with the media throughout the 1990s, as well. Until his death was formally announced in 1999, no one had been completely sure if the great business titan was still alive. Employees supposedly had learned to avoid mentioning the father’s name around his kids—even when the kids themselves had reached retirement age.

[M&Ms World in Las Vegas, 2014]

[M&Ms World in Las Vegas, 2014]

Still, for all the animosity, Forrest Mars Jr. and John Mars—much like the grandfather they never really knew—had an undeniable respect for Forrest Mars Sr. as a strategist, manager, and innovator. They followed his belief in absolute privacy, and they trained future leaders of the company in the so-called “Five Principles” of the Mars business: Quality, Responsibility, Mutuality, Efficiency, and Freedom. They didn’t suffer fools easily, and in the most commonly cited example of their perfectionist nature, they made human employees taste test the pet food.

Mars Inc. was criticized through the end of the 20th century for everything from the obesity epidemic to animal testing and skimping on charitable contributions, but through it all, the business’s global reputation remained largely undamaged, and its profits continued to grow.

Mars Inc. was criticized through the end of the 20th century for everything from the obesity epidemic to animal testing and skimping on charitable contributions, but through it all, the business’s global reputation remained largely undamaged, and its profits continued to grow.

In a nice sign of change, the company’s fourth generation of leadership, with Victoria Mars as Chairman and Grant F. Reid (a rare outsider) as CEO, has shown signs of creating more direct involvement with the community and giving people a look behind the curtain. Mars continues to maintain a presence in Chicagoland, as well, with an ice cream plant in Burr Ridge, a candy factory in Yorkville, and a pet food plant in Mattoon. The global headquarters of its chocolate and chewing gum subsidiary, now known as Mars Wrigley Confectionery, is also still here, inside Goose Island’s “Global Innovation Center.”

As for the legendary Galewood candy facility . . . it’s still in use, but the company announced that it will permanently close in 2024, putting close to 300 men and women out of work, and leaving the building just a few years shy of its 100th anniversary. Mars execs say they will donate the campus to the community for a new use.

Unlike eating a Snickers bar, the Mars Inc. story doesn’t always satisfy. It wasn’t the rags to riches tale of a Norman Rockwell family, nor do the heroes of the story always elicit our sympathy. Like a Mars Bar posing as a Milky Way, things aren’t always what their packages would suggest. But once you can see it for what it really is, it may prove admirable in some other ways you never anticipated.

[Early Snickers wrapper design from 1939]

[Early Snickers wrapper design from 1939]

Sources:

Corporate Cultures and Global Brands, edited by Albrecht Rothacher

“Forrest Mars Sr.,” Biography Today: Scientists and Inventors Series, 2001

“Minneapolis Candy Firm Moving Here” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 12, 1928

“The Sweet, Secret World of Forrest Mars,” Fortune Magazine, 1967

“Standard Set By Mars Plant Built in 1928,” Chicago Tribune, Nov 15, 1953

“The Mysterious Candy Man” – Reno Gazette-Journal, Oct 20, 1986

“The Candy Man,” The Guardian, 1999

“Sweet Secrets: Opening Doors on the Very Private Lives of the Billionaire Mars Family,” The Washingtonian, 1996

“Life in Mars: Reclusive Dynasty Behind One of World’s Most Famous Brands,” The Guardian, 2008

On Leadership, by Allan Leighton, 2007

“Life on Mars: The Mars Family Saga has All the Classic Elements,” by Joel Glenn Brenner, The Independent, 1992

The Emperors of Chocolate: Inside the Secret World of Hershey and Mars, by Joel Glenn Brenner, 1998

Bitter Chocolate: Investigating The Dark Side Of The World’s Most Seductive Sweet, by Carol Off

Crisis in Candyland: Melting the Chocolate Shell of the Mars Family Empire, by Jan Pottker, 1995

Archived Reader Comments:

“My folks took my brother and I to “Super Circus,” a TV show on Sundays during the 1950s. The program was telecast fro the Civic Opera House/Kemper Insurance Bldg on Wacker Drive just south of Lake Street. It was sponsored by Mars Candies…Milky Way, 3 Musketeers and Snickers (which I sometimes still indulge myself). My uncle worked for Kimball Candy on Belmont Avenue, a business that produced a most horrible tasting coconut candy.” —Dave, 2020

“Does anyone remember Mrs. Stevens candy co ??? It was located just south of Chicago Av. on Franklin Blvd. About 700 north.” —Just Curious, 2019

“My grandfather Thomas Dattalo and Mr. Mars made candy together in Minnesota. They started the business together. Mars had the money, my grandfather knew how to make candy. But he never got any recognition for this. They came down to Chicago together with my grandfather’s nephew, James, to start the business on Oak Park Ave. I believe around the Depression time. My uncle did the landscaping for years until he died. My uncle lived in Elmwood Park. My grandfather was the Master Candy Maker. He lived on Oak Park Ave. Mr. Mars had bought the house for him. When Mars’s son came back, he claimed all the rights of the candy making. Thomas’s nephew, James Dattalo, went on to open the Fudge Pot in Chicago on Wells Street. His son still operates it today. Dave Dattalo.

. . . We tried to get information to prove this but when Mars’s son came back he closed off all the information towards the history of the company. Is there anyway you can dig a little for us. We feel our grandfather got the raw deal. Forrest Mars did send a letter to my brother regarding my grandfather.” —Rosanne Dattalo Eiternick, 2017

“Hi Rosanne, this is great info. I will try to dig around for old news stories that might mention your grandfather and Mars. Do you still have the letter Forrest Mars wrote to your family? If I can substantiate the story, I will happily add Thomas Dattalo to the Mars origin story. Many thanks!” —Made In Chicago Museum

“I have an old display box for the “Two Bits” candy bar and I am wondering why there is no mention of this bar in the history ? I would appreciate more information and an approximate date this candy was made.” —Janice, 2017

“Hi Janice. The “Two Bits” was a variation on the Milky Way, featuring chocolate, peanuts, and cream caramel. It was introduced in the mid 1930s and was still available at least into the 1950s, it appears. There are a number of Mars products not mentioned in the history above, as short-lived brands didn’t carry the same significance to the business.” —Made In Chicago Museum

Hello. My mother, Mary O’Leary Heraty, worked at the Mars production facility in Chicago around 1940. I don’t know whether she would be working under the name O’Leary or Heraty at the time. She was married in 1939 and her husband, John E. Heraty, was a pipefitter who died in a construction accident on August 3, 1950. My widowed mother was left with 6 children (ages 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12) and gave birth to her seventh child one month after my father’s death. You can understand why we are trying to piece together the story of her remarkable life. Thanks so much for any information you can provide to my 4 remaining siblings and me. God bless.

My sister was friends with Judy Fleming. She was Patricia’s daughter. Judy invited my sister and me to come to Marlands for a vacation during the summer of 1956 or so. We went back for several more wonderful visits. Judy’s 1/2 sister, Pat, was coming up from Phoenix and I was to be friends with her. I ended up being in her wedding several years later. Those were amazing memories and crazy times. Patricia had seven children and they were all there with various friends. We put on water ski shows for the adults, had parties every night, and one street dance where we wore gunny sacks over bathing suits and the boys wore white formal jackets over their swimming trunks. They had Mars bars on this long table in a bowl that most people use as fruit bowls. It was 40 acres of fun and wonderful memories.

Sadly Mars announced the pending closure of the Galewood factory earlier this year. No timetable was given. It was the site of the best field trip I ever had in grade school (back in the early 1960’s).

After reading this article I realizes I didn’t know as much about the family as I thought. I worked in Cleveland , Tenn.plant 20 yrs. I was Good Will ambassador to Confectionates. I met Forest Sr. At Ethel M and had breakfast with him and his little dog Susie. He learned I was there after losing my son in military. We talked times. He had his regrets about the problems with his dad. After having his stoke and moving to Miami I visited him. He was a gracious host. I gave him a golf shirt from the Minnapolis Country club his father had designed. The Milky Way Farms main house is designed After the club. Mars tops any company for employment in my opinion. The family was very personal with their associates. First name basis alway. They lived the 5 principles. So did we..a choice not a force

I lived in Nevada in the 70s and 80s and really enjoyed Mrs. Mars candy which was liquor filled. Are they still being made? Thank you for your reply.

My father and some of his high school friends worked there in the mid-1940’s. One of the funny stories Dad told was they let you eat as much candy as you wanted while on shift. He said after about 2 weeks, you could not stand the thought of eating it any more.

My Aunt and brother each worked at Mars candy at the facility on Oak Park Avenue.My Aunt was there in the 40’s and beyond and was secretary to William Kruppenbacher. She had many photos and memorabilia from there. She also had the picture of Fran Mars on his farm in Tennessee and a hand carved cane that belonged to Frank Mars. I also have a hand written journal from Mrs Kruppenbacher for an around the world cruise they took in 1960. Please let me know if you have any interest in these items.

HI Judy.

My Aunt Glorene Snell Parcel and her husband Millard Parcel worked at the Chicago plant during the 40’s as well. I am trying to locate any info and/or photos of them during that time. Also anyone that may still be living that may have been friends of theirs that might have any stories to share. Thank you for your reply.

God Bless You.