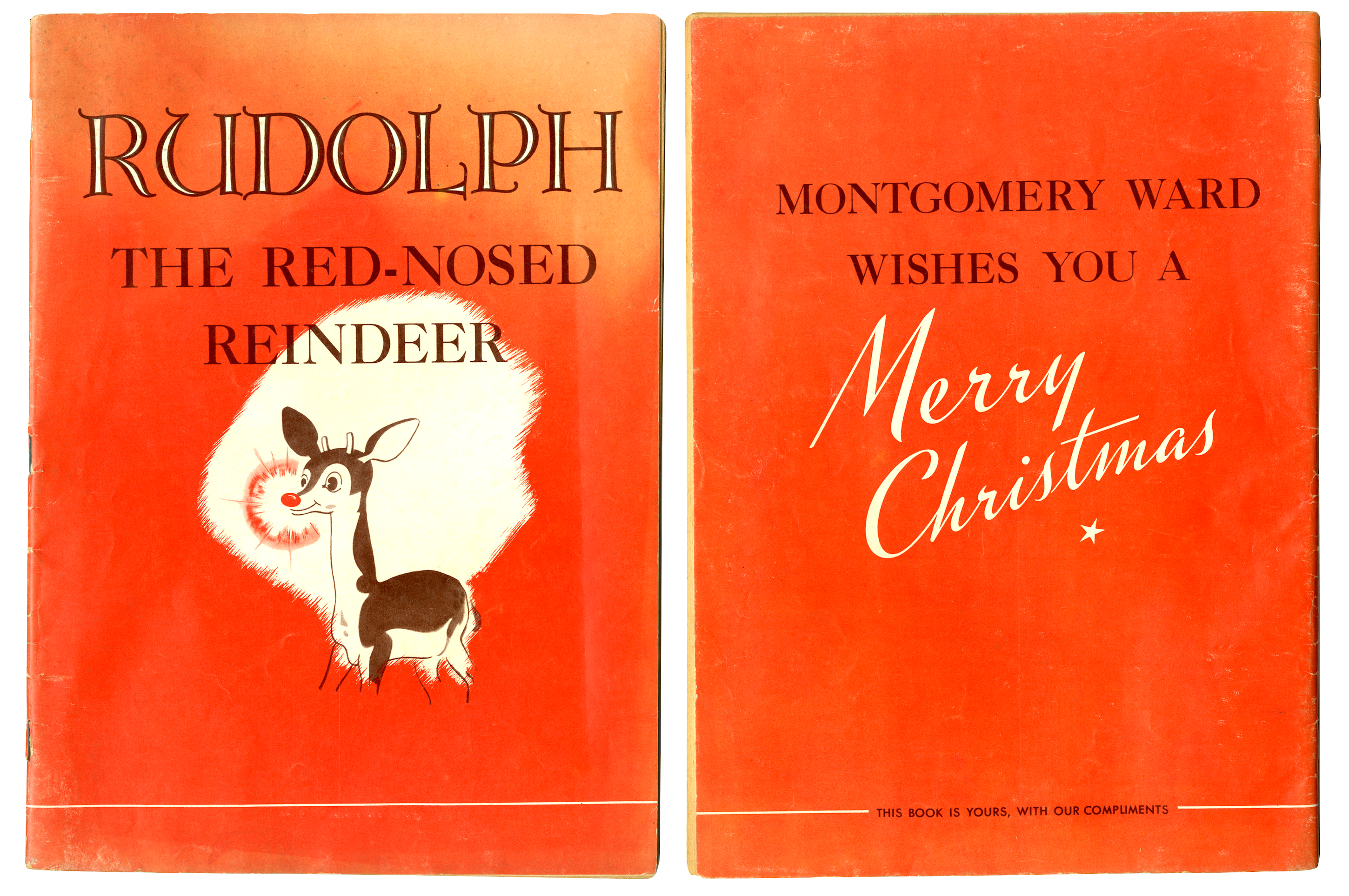

Museum Artifact: First Edition “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” Illustrated Book by Robert L. May, 1939

Made By: Montgomery Ward & Co., Inc., 758 N. Larrabee Street, Chicago, IL [River North]

“Today children all over the world read and hear about the little deer who started out in life as a loser just as I did. But they learn that when he gave himself for others his handicap became the very means through which he achieved happiness. My reward is knowing that every year when Christmas rolls around, Rudolph still brings that message to millions, both young and old.” —Robert L. May, copywriter at Montgomery Ward and creator of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, quoted in 1975

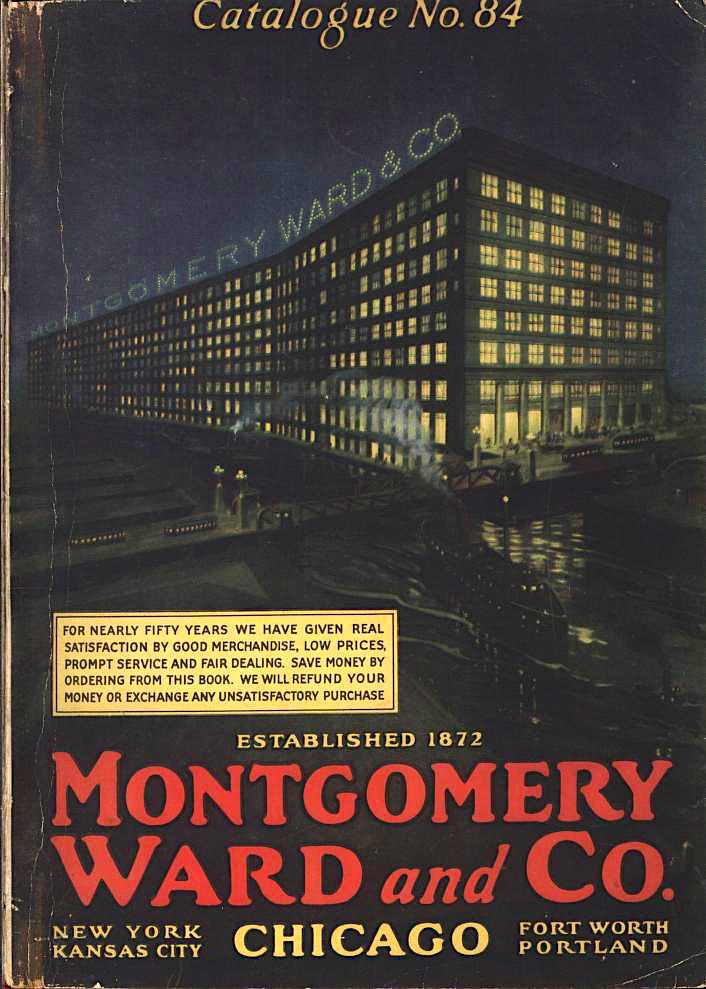

Eclipsed only by its longtime crosstown nemesis Sears, Roebuck & Co., the firm of Montgomery Ward & Co. was one of the uber-giants of 20th century American retail—a pioneer of mail-order merchandising that built up an equivalent brick-and-mortar empire, only to gradually collapse under its own unsustainable weight. As an important distinction, Ward’s was essentially a master distributor, and never manufactured goods of its own on the considerable scale that Sears did during the height of the two companies’ rivalry. What Ward DID do, however, was generate IDEAS, and at least one of them resulted in a pop cultural phenomenon that has long outlasted the company itself.

Eclipsed only by its longtime crosstown nemesis Sears, Roebuck & Co., the firm of Montgomery Ward & Co. was one of the uber-giants of 20th century American retail—a pioneer of mail-order merchandising that built up an equivalent brick-and-mortar empire, only to gradually collapse under its own unsustainable weight. As an important distinction, Ward’s was essentially a master distributor, and never manufactured goods of its own on the considerable scale that Sears did during the height of the two companies’ rivalry. What Ward DID do, however, was generate IDEAS, and at least one of them resulted in a pop cultural phenomenon that has long outlasted the company itself.

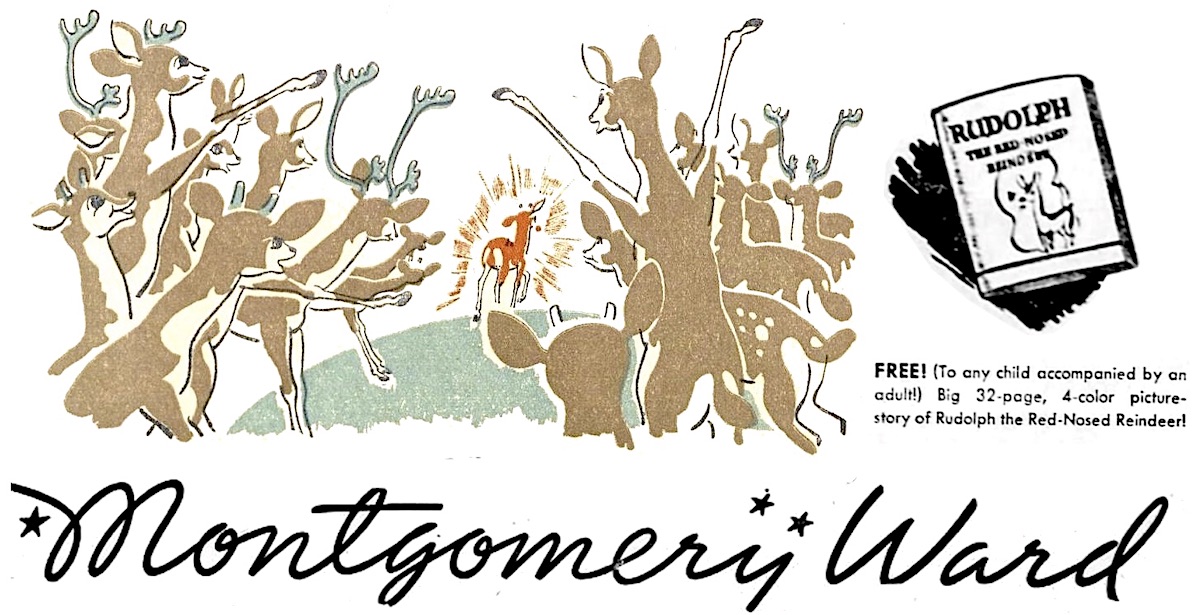

Believe it or not, the cheaply-made, 32-page “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” booklet featured in our museum collection is among the more valuable items we have on display. That’s because it’s a fairly rare, in-tact example of the original 1939 edition of the story, which debuted that year as a free holiday giveaway to visitors of Montgomery Ward’s retail stores (often handed to kids by Santa himself). There were no songs about Rudolph yet, nor any animated TV specials. This was the entirety of the character’s footprint in the zeitgeist. And yet, the simple underdog story (or under-deer story, I guess) penned by Ward copywriter Robert L. May instantly gained traction that first December.

“Ferdinand the Bull has a competitor,” announced an article in the December 10, 1939 edition of the Sedalia Democrat (a small newspaper in Missouri). “‘Rudolph, the Red-nosed Reindeer,’ it seems, is becoming the irresistible hero. . . . The little Christmas story was conceived, written and illustrated by members of the retail sales department of Montgomery-Ward in Chicago for a Christmas gift to customers in Ward stores. Orders from the retail stores and catalog order offices have totaled 2,400,000 copies, and, according to the company, teachers and psychologists are calling it a ‘perfect Christmas book for children.’ . . . It’s one of those whimsical little pieces that puts children in a gleeful mood and entertains adults as well.”

For all its associations with holiday cheer, Rudolph really was a shining light—pun intended—during a dark time both for its author and the country. This was the same year a very different ‘Dolph invaded Poland, after all, and while FDR’s New Deal had helped galvanize the economy and improve the status of companies like Montgomery Ward, the Depression wasn’t entirely in the rearview mirror just yet. For Robert May, the concerns were more personal.

“Here I was heavily in debt at age 35 still grinding out catalogue copy instead of writing the great American novel as I had once hoped,” May recalled in a 1975 article about the creation of Rudolph. “I was describing men’s white shirts. It seemed I’d always been a loser.”

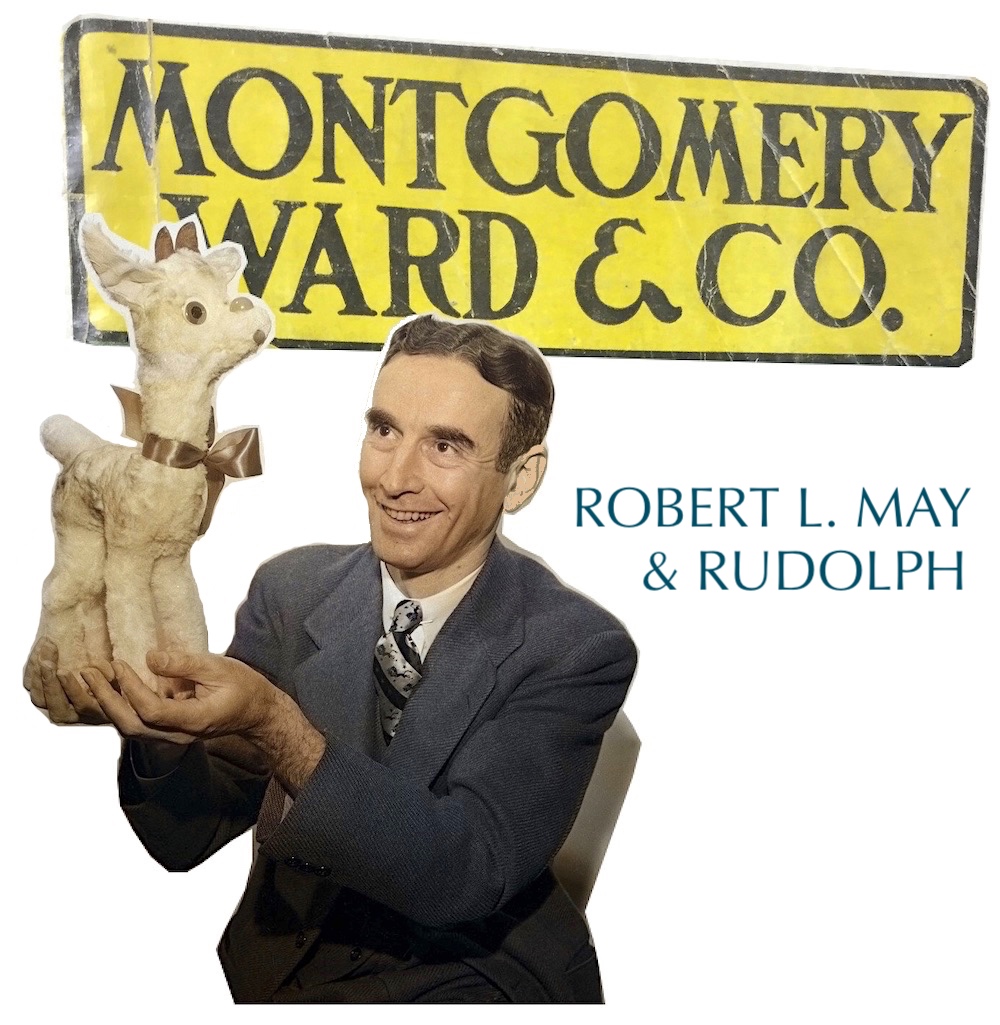

While making a measly salary as a copywriter, May had at least developed a reputation in the office for his funny poems and limericks, and thus he was called upon, in January of 1939, to start brainstorming a kids book for the following Christmas—something to replace the expensive holiday coloring books that Ward had been buying from other dealers. His boss requested that it be an animal-centric story, along the lines of Ferdinand the Bull, which had been published to great success a few years earlier.

While making a measly salary as a copywriter, May had at least developed a reputation in the office for his funny poems and limericks, and thus he was called upon, in January of 1939, to start brainstorming a kids book for the following Christmas—something to replace the expensive holiday coloring books that Ward had been buying from other dealers. His boss requested that it be an animal-centric story, along the lines of Ferdinand the Bull, which had been published to great success a few years earlier.

“I wondered about what kind of animal it should be,” May wrote. “Christmas . . . Santa . . . Reindeer? Of course, it must be a reindeer! Barbara, my four-year old daughter, loved the deer down at the [Lincoln Park] zoo. But what could a little reindeer teach children?”

May, who was ethnically Jewish but non-religious, decided he would cast his Christmas reindeer as an underdog like himself—“a loser, yet triumphant in the end.” Sitting in his office in the Montgomery Ward administration building at 758 N. Larrabee Street, May pondered his reindeer character (who was very nearly named Reginald)—and how it might find its way to joining Santa’s famous team of sleigh pullers.

“Outside the fog swirled in from Lake Michigan, dimming the street lights,” May remembered. “Light . . . something to help Santa find his way on a night like this. Suddenly I had it! A nose! A bright red nose that would shine through fog like a flood light.”

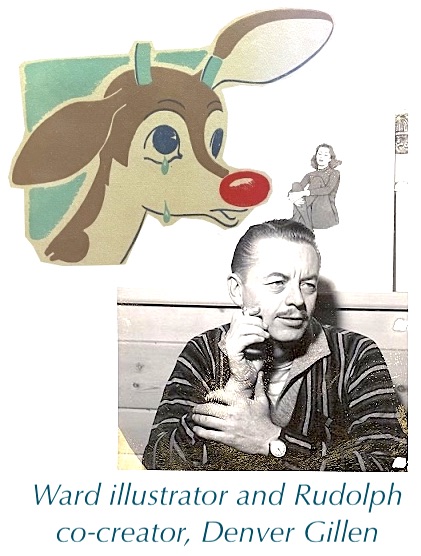

After hatching the idea, May walked over to the art department and asked Ward illustrator Denver Gillen to come with him to the Lincoln Park Zoo to visit the deer corral and draft some sketches for the book. The two then presented their outline for “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” to their boss, and the project was a-go (despite some concerns about a red nose suggesting the deer had a drinking problem).

Unfortunately, what should have been an enjoyable creative process for Robert May became far more challenging as the year went on. His wife Evelyn had been diagnosed with cancer, and her condition took a turn for the worse that summer. She died in July at just 33 years of age, leaving May a widower and single father.

Unfortunately, what should have been an enjoyable creative process for Robert May became far more challenging as the year went on. His wife Evelyn had been diagnosed with cancer, and her condition took a turn for the worse that summer. She died in July at just 33 years of age, leaving May a widower and single father.

After losing Evelyn, Robert was given the option to set aside the Rudolph project, but he refused, later writing that “I needed Rudolph now more than ever. Gratefully I buried myself in the writing. Finally, in late August, it was done. I called Barbara and her grandparents into the living room and read it to them. In their eyes I could see the story accomplished what I had hoped.”

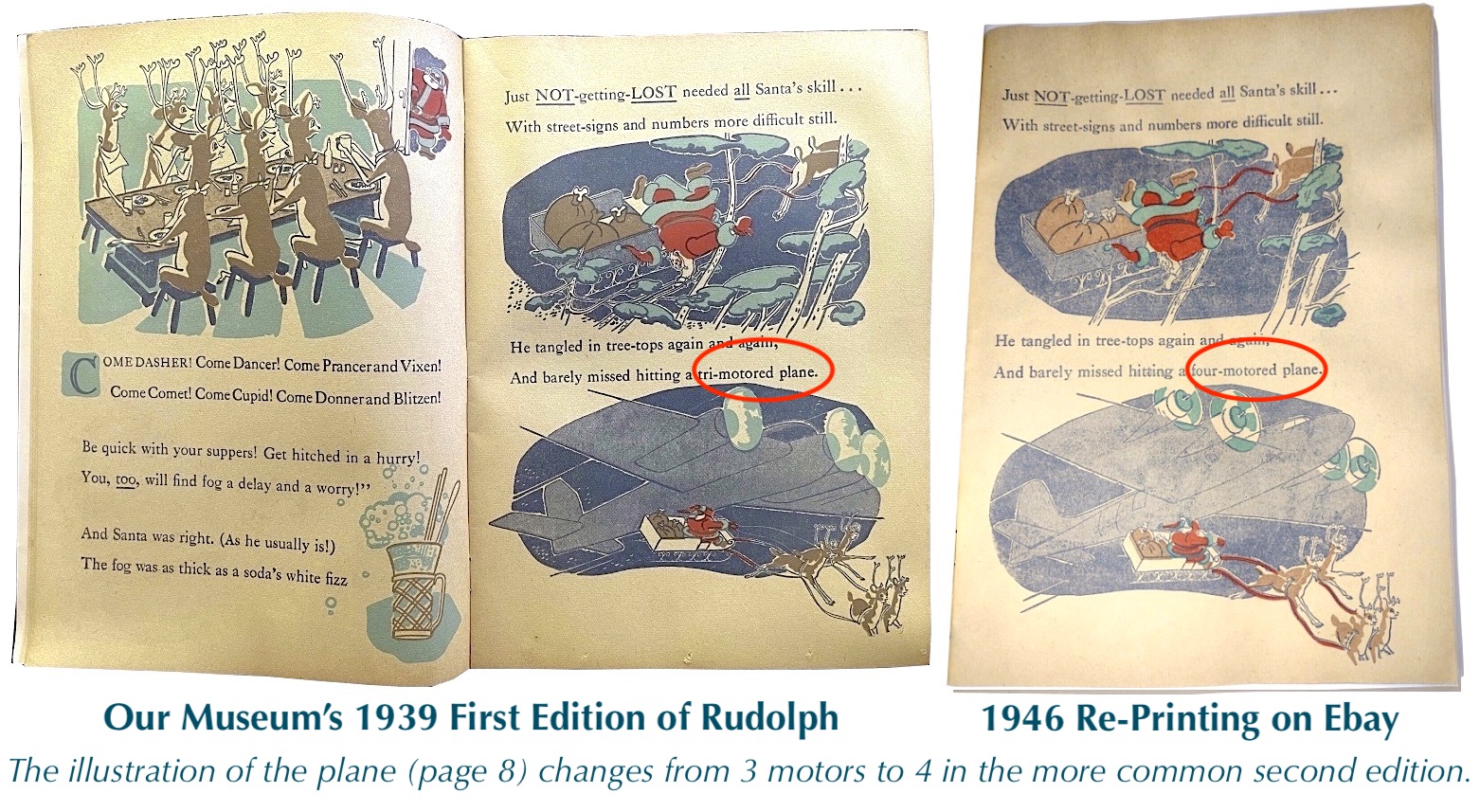

Two years later, in 1941, Robert married a Montgomery Ward secretary and aspiring artist named Virginia Newton, and the couple had five more children. The character of Rudolph took a hiatus during the war years, but the booklet was re-published, with slight tweaks, and handed out in even greater numbers in 1946, re-igniting reindeer-mania. [Incidentally, a lot of folks on eBay still regularly try to pass off the 1946 second edition as an original “first edition” of Rudolph, but there are ways to tell the difference, as noted in the comparison below].

What happened next truly feels like a grand gesture from a bygone time. In 1947, with interest in Rudolph at an all-time high and demand growing for new adaptations of the story, Montgomery Ward’s polarizing president Sewell Avery stunningly agreed to hand over 100% of the rights to the poem and character to Robert L. May, who’d still been struggling financially balancing his new family with lingering debt from his late first wife’s medical bills.

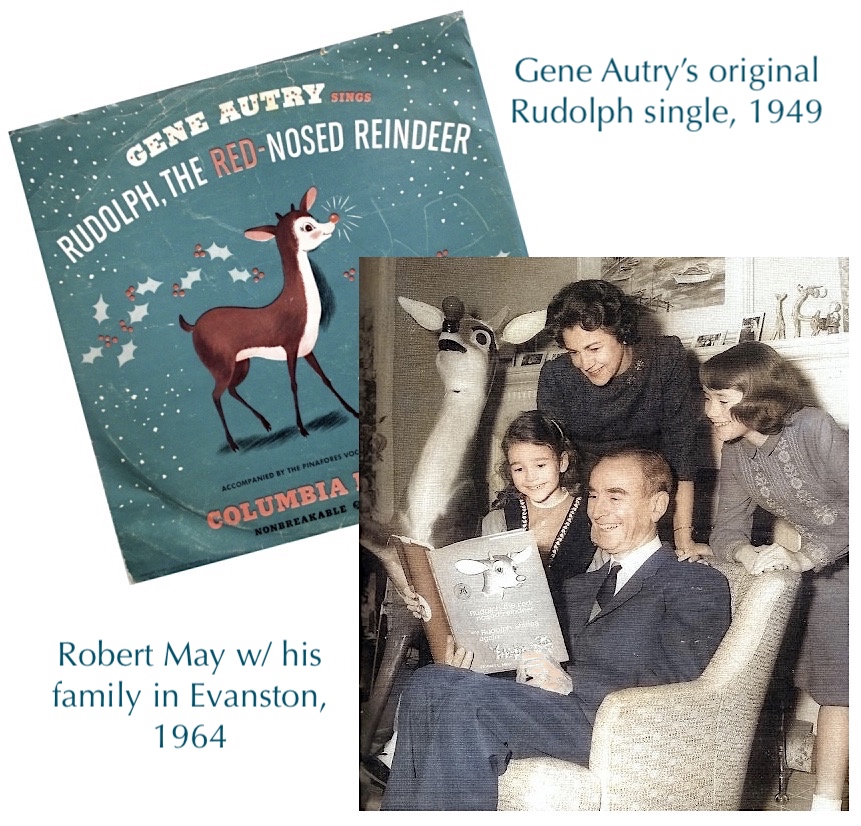

The first commercial version of the Rudolph book was published by Christmas of that year, and by 1949, cowboy singer Gene Autry had scored a big hit with the first rendition of the “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer” song—written by Robert May’s brother-in-law Johnny Marks.

“There is no question but that Rudolph has become a legend—the first new and accepted Christmas legend since Charles Dickens’ ‘A Christmas Carol,’ and Clement Moore’s ‘A Visit from St. Nicholas,’” the Chicago Tribune proclaimed in 1950.

“There is no question but that Rudolph has become a legend—the first new and accepted Christmas legend since Charles Dickens’ ‘A Christmas Carol,’ and Clement Moore’s ‘A Visit from St. Nicholas,’” the Chicago Tribune proclaimed in 1950.

One would presume that Robert L. May was set for life, but in reality, after focusing on Rudolph properties throughout the 1950s, he eventually found himself back in Montgomery Ward’s copy department—a victim of America’s sky high tax rates at the time. Even after the famous Rudolph stop-action animation TV special debuted in 1964, the character’s creator remained a catalog copywriter in Ward’s Chicago office, finally retiring in 1970 at the age of 65 (he died in Evanston in 1976).

Fifty years later, few people remember the Chicago ad man behind a beloved worldwide Christmas tradition, and as time goes on, memories of the enormously successful company he worked for have similarly faded. But the success of Rudolph was no fluke; it was made possible by the merchandising engine of Montgomery Ward & Co.—the firm that set the template for how to package and sell everything to everybody in the modern age.

History of Montgomery Ward & Co., Part I: The Godfather of Mail Order

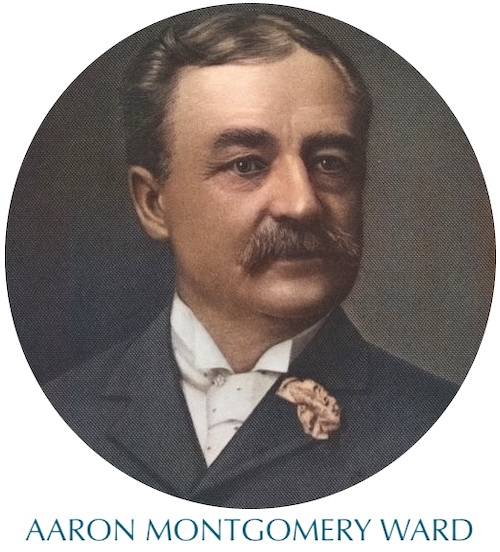

Unlike Sears-Roebuck (which was a partnership between Richard Sears and Alvah Roebuck), the name Montgomery Ward referred to just one man—Aaron Montgomery Ward: Godfather of Mail Order.

Born in Chatham, New Jersey in 1844, Ward was the working class son of a cobbler. His family moved to Michigan when he was nine, and by the age of 14, he’d already set out on his own, taking a series of odd, hard labor jobs in barrel factories and brickyards around the Midwest. It wasn’t until he landed an easier gig selling shoes, however, that Ward found his life’s calling as a skilled and intuitive dealer of goods.

As a traveling frontier salesman of the Great Plains, young Aaron Ward was usually far from the battlefields of the Civil War, despite being of the right fighting age. When the smoke had cleared, around 1866, he made his way to Chicago—America’s fastest growing city—to work as a salesman in the wholesale department of Field, Leiter & Co., the precursor to Marshall Field & Co.

As a traveling frontier salesman of the Great Plains, young Aaron Ward was usually far from the battlefields of the Civil War, despite being of the right fighting age. When the smoke had cleared, around 1866, he made his way to Chicago—America’s fastest growing city—to work as a salesman in the wholesale department of Field, Leiter & Co., the precursor to Marshall Field & Co.

It was a brief, early crossing of paths for two legendary names of Chicago commerce, as the 22 year-old Ward took notes from the innovative practices of 31 year-old Field—the mastermind of the modern department store. Ward also began to develop a business idea of his own; one that borrowed from the big city wholesalers, but was better equipped to meet the needs of the smalltown and rural customers he’d come to know from his wandering salesman days.

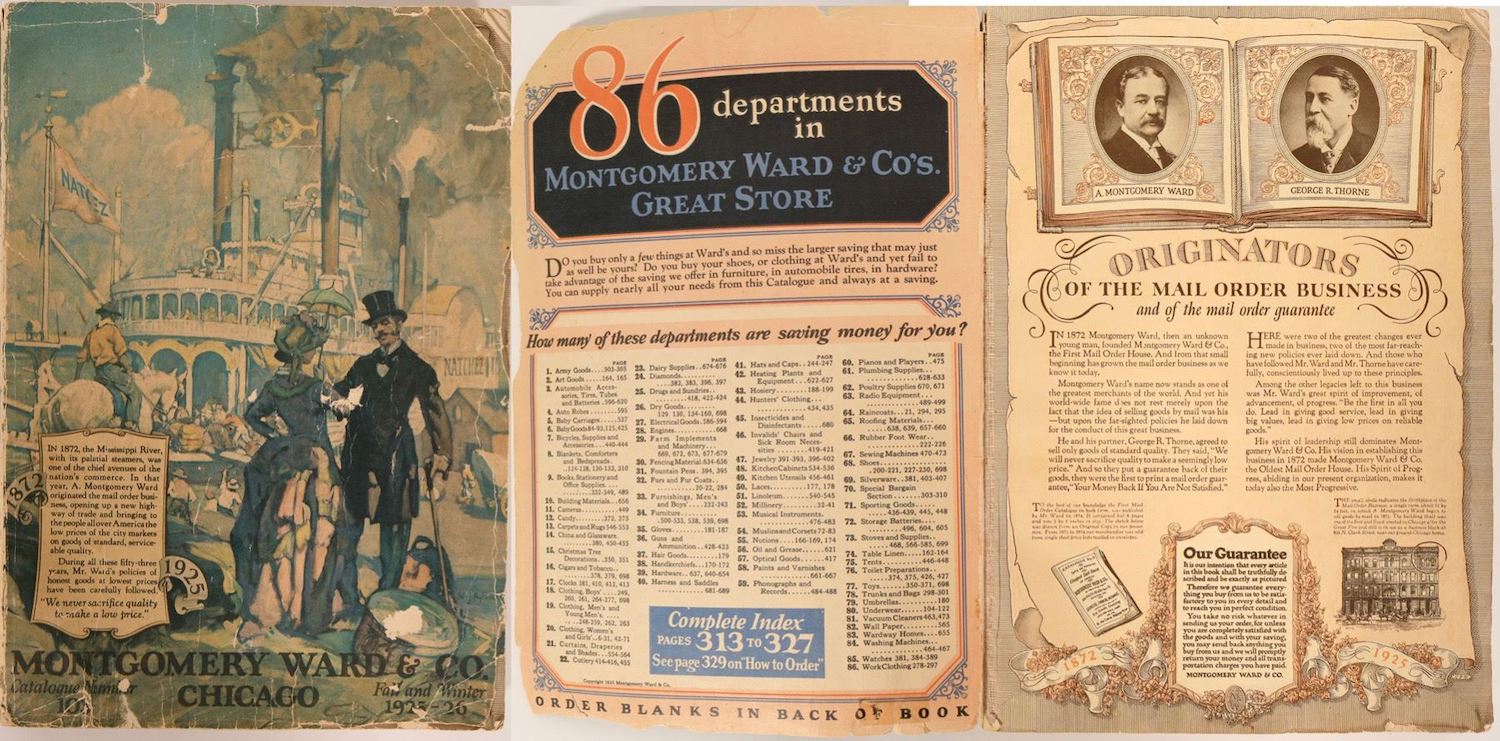

In point of strict fact, Montgomery Ward & Co. were not the “originators of the mail order business,” as the company often claimed. Businesses were sending out specialized catalogues for quite a few years before and during the war, using the new power of the railroad to connect with customers in the expanding West. Even Marshall Field had a mail order service in effect by 1870. Before Montgomery Ward, however, no one had quite figured out just how much potential this business model really had . . . and how limitless its inventory could become.

“Having had experience in all classes of merchandise (as a) traveling salesman,” Aaron Ward later wrote, “and (being) a fair judge of human nature, I saw a great opening for a house to sell direct to the consumer and save them the profit of the middle man.”

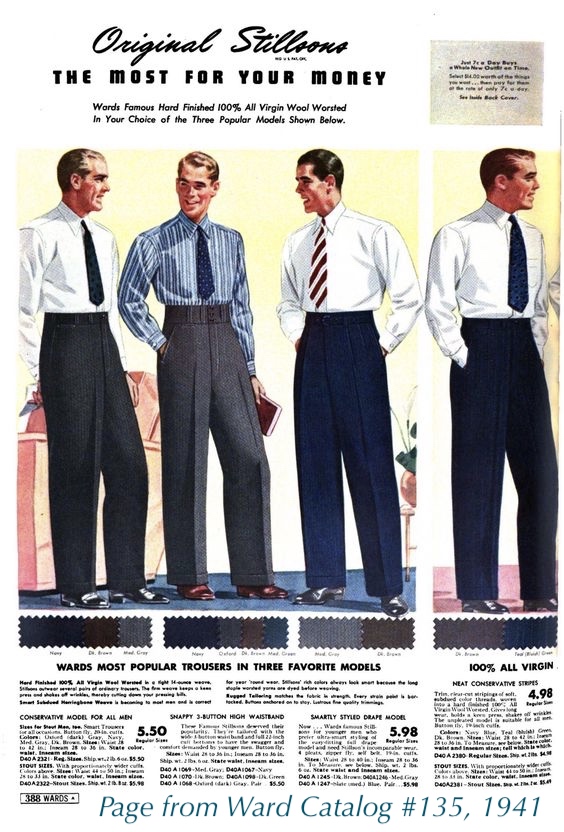

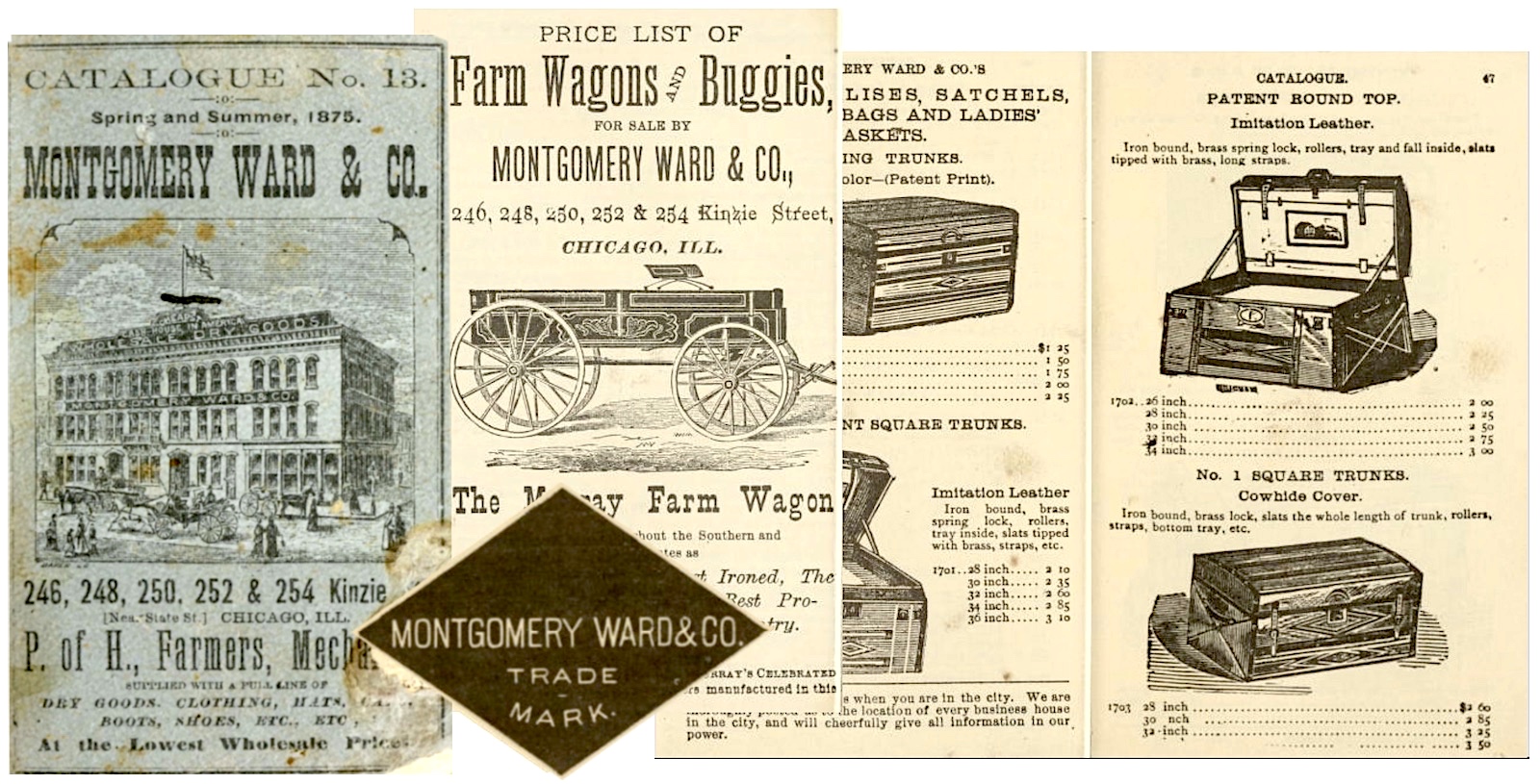

[Pages from Ward & Co. catalogue No. 13, 1875]

There was never a better time to launch a new mail order firm—and yet, it was also a remarkably unlucky moment to be timely. In the fall of 1871, after Ward had spent months putting together an inventory of goods for his very first catalog, the Great Chicago Fire reduced it all to ash. An older man might have taken that as a sign, but at 27, Ward just started over again, and with two investors from the C. W. & E. Pardridge Company, he re-loaded and launched his humble mail order house in 1872, run out of a small shipping office near the corner of Clark Street and Kinzie.

Considering that the whole country fell into an economic depression a year later, one could start to imagine that Aaron Ward’s dream was cursed. But in this case, good common sense won out.

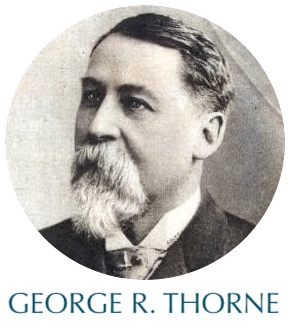

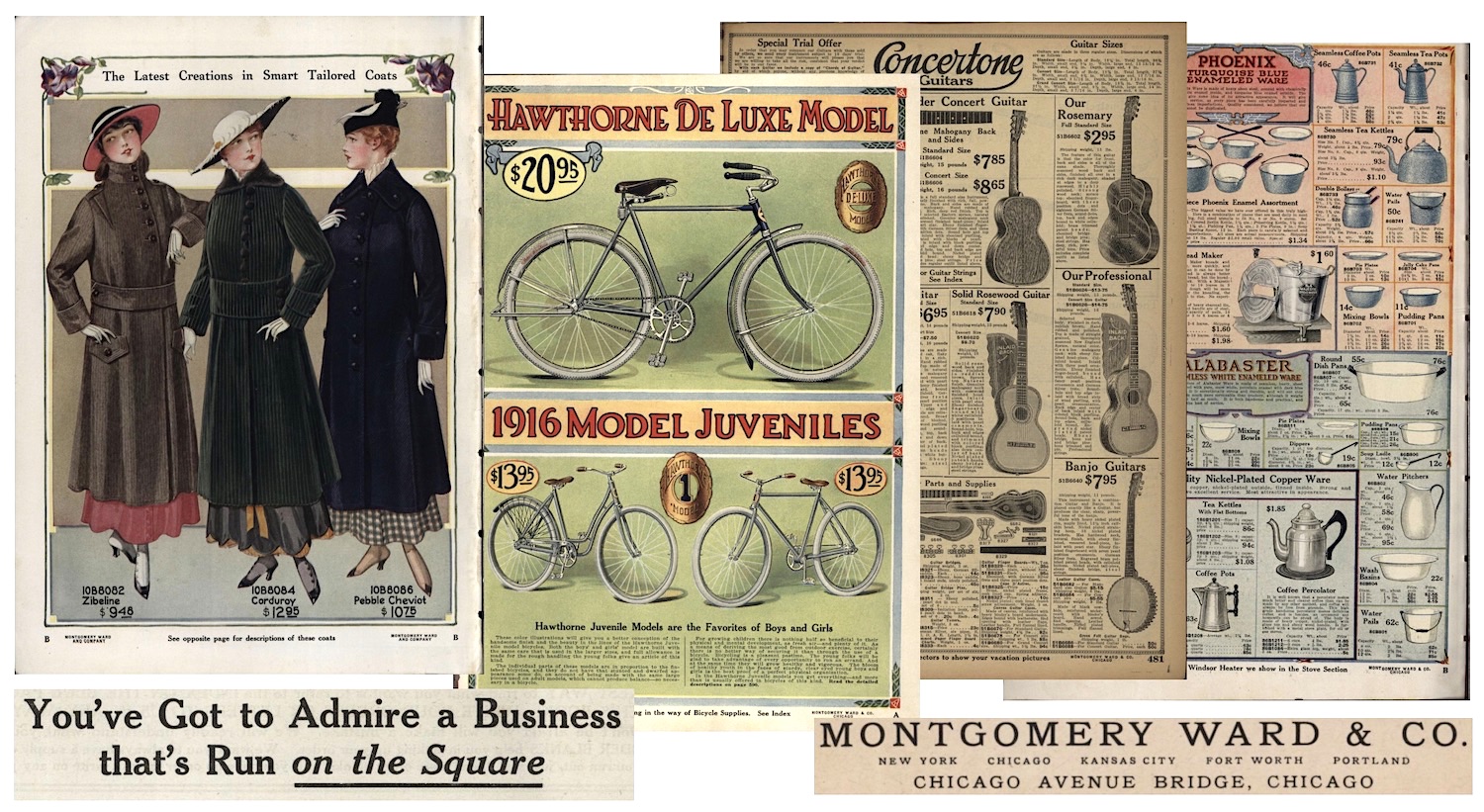

After a few years, Ward’s brother-in-law George R. Thorne joined him in the business, and the catalog was finding a real footing in the Heartland, expanding to 72 pages, albeit with just a dozen or so illustrations included. Catalogue No. 13, that spring, featured indexed sections for men’s and women’s clothes, linens and blankets, silverware, stationery, watches, jewelry, and traveling trunks.

After a few years, Ward’s brother-in-law George R. Thorne joined him in the business, and the catalog was finding a real footing in the Heartland, expanding to 72 pages, albeit with just a dozen or so illustrations included. Catalogue No. 13, that spring, featured indexed sections for men’s and women’s clothes, linens and blankets, silverware, stationery, watches, jewelry, and traveling trunks.

It’s not hard to grasp the appeal of being able to order such a range of necessities and novelties all at once—it’s the same idea behind Amazon’s success 150 years later. The even more revolutionary pitch, though, was Montgomery Ward & Co.’s unique guarantee: “If any of your goods are not satisfactory, after due inspection, we will take them back… and refund the money paid for them.”

The new age of “Love It Or Your Money Back” had begun, a full 18 years before Richard Sears got into the same racket.

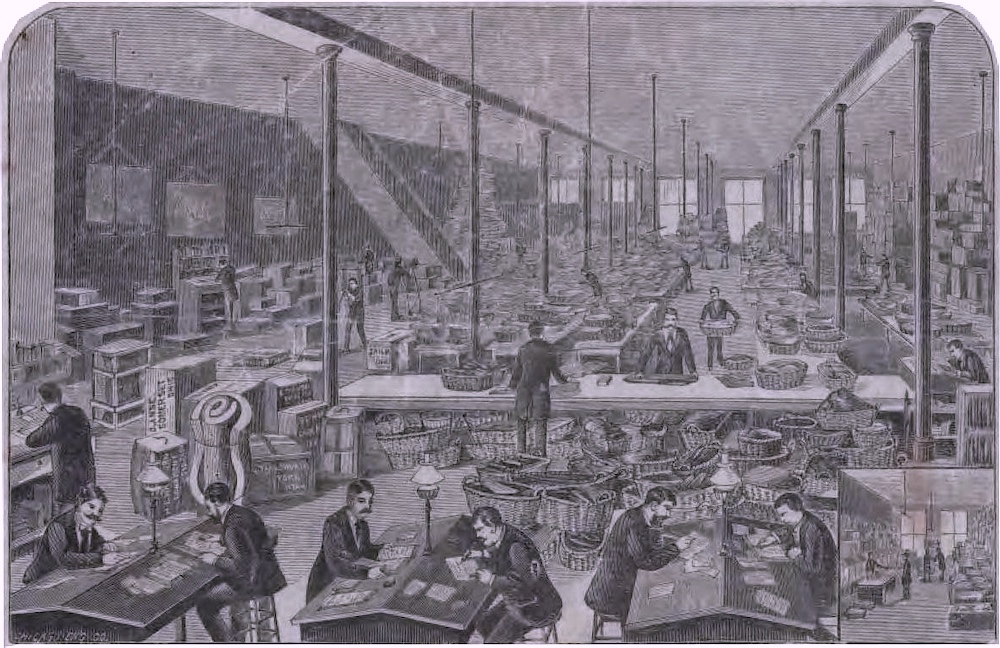

[Etching of the the third floor of the Ward & Co. warehouse at 227-229 Wabash Avenue, 1878]

II. An Unobstructed View

In his mid 30s, Aaron Montgomery Ward spent much of his time doing the same work Robert L. May would a half century later—writing catalog copy. His business was growing and succeeding, but it was still an upstart organization which—as a conduit between urban manufacturers and far-away farmers—relied heavily upon messaging to close the gap and earn the public’s trust.

“Aaron Ward proved a low-key, highly effective copywriter—the greatest who had ever appealed to farmers,” author Cecil C. Hoge wrote in his 1988 book, The First Hundred Years are the Toughest: What We Can Learn About the Century of Competition Between Sears and Wards. “He sold them as he taught them how to buy, and won their respect. He had a gift of extraordinary clarity. He knew what they wanted, what frustrated them, and how to persuade them better than anyone in mail order had before. He took the fear out of dealing by mail.”

Early catalogues featured hardly any flowery language or bold claims; it was all about establishing the process and setting the ground rules. “Order as much of anything as you wish,” Ward writes in the intro to the 1875 catalogue, “and you will be charged only in proportion to our quotations. . . . In writing your name and address, do not endeavor to show us a sample of spread-eagle, but rather affect the simple, plain and perfectly legible signature of John Hancock.”

Early catalogues featured hardly any flowery language or bold claims; it was all about establishing the process and setting the ground rules. “Order as much of anything as you wish,” Ward writes in the intro to the 1875 catalogue, “and you will be charged only in proportion to our quotations. . . . In writing your name and address, do not endeavor to show us a sample of spread-eagle, but rather affect the simple, plain and perfectly legible signature of John Hancock.”

By the 1880s, Montgomery Ward was widely known as the largest and most reputable mail order house in the country. In 1889, the same year Ward and Thorne finally opted to incorporate the business, the firm topped the $2 million sales mark for the first time and commissioned a new eight-story headquarters on a prime plot along Michigan Avenue. Once moved in, it seemed the company’s success had also increased the hubris of its managers, which now included all five of George Thorne’s sons.

“We started this mail order business and made it such a success that there is scarcely a department store in the land which has not tried it too,” read a Montgomery Ward ad in a December 1892 edition of Farmer’s Voice magazine. “They all, without exception, imitate our methods as far as they can find them out; they all want to know: ‘How does Montgomery Ward & Co. do it?’ We will tell you. We carry the goods in stock and are the only firm who can honestly say so. We attend to the mail order business alone. It is not a side issue with us, but our entire business. We have no retail trade to bother us and delay us. We study methods of improving our business as we would a science. We imitate no one.”

[Montgomery Ward promotional card from the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago]

Part of this smug perspective also meant that Ward executives never saw any of its emerging copycat competitors as a real threat—including Chicago’s own Sears, Roebuck & Co., which aimed at the same clientele with more of a willingness to cut corners, sell cheaper, and make bigger promises.

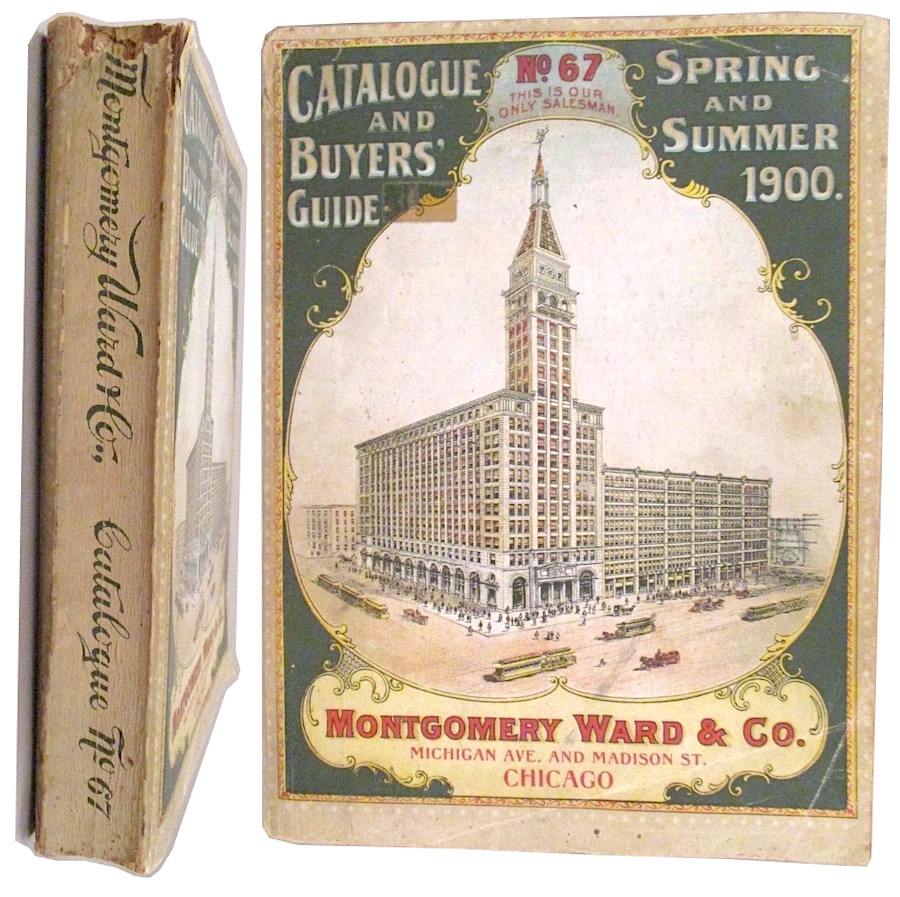

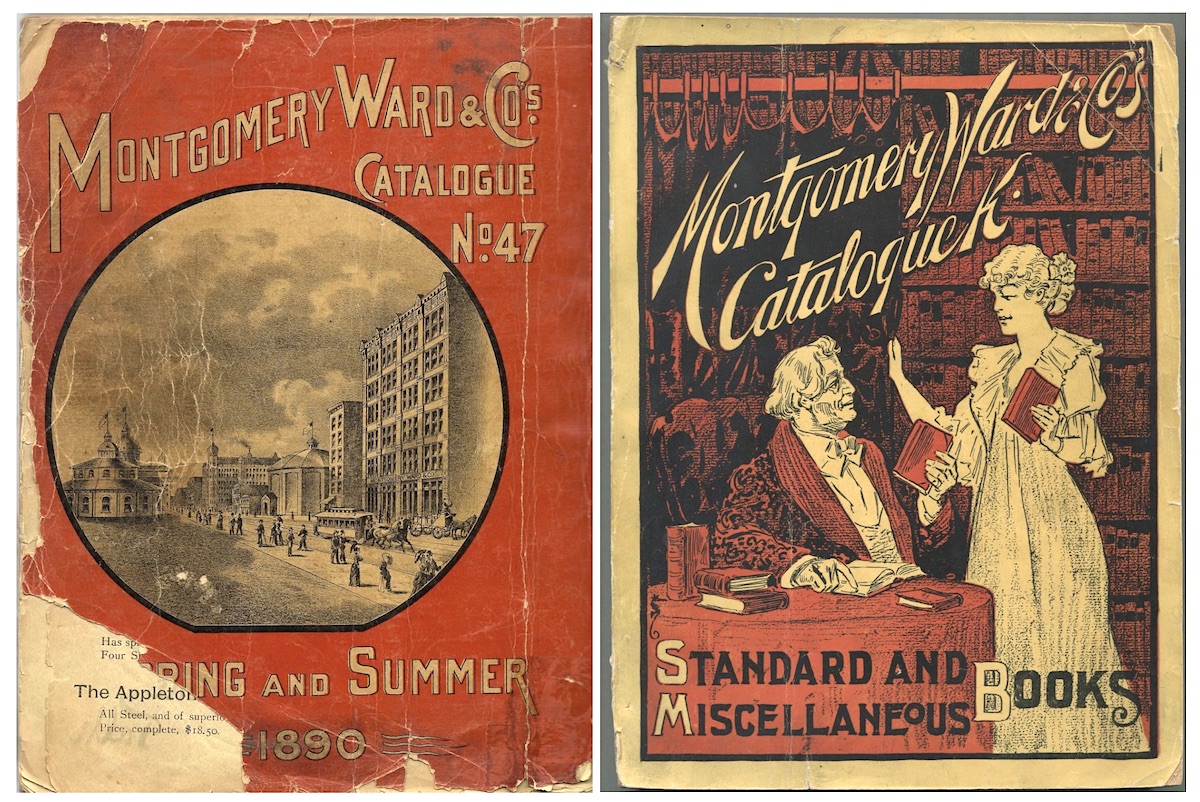

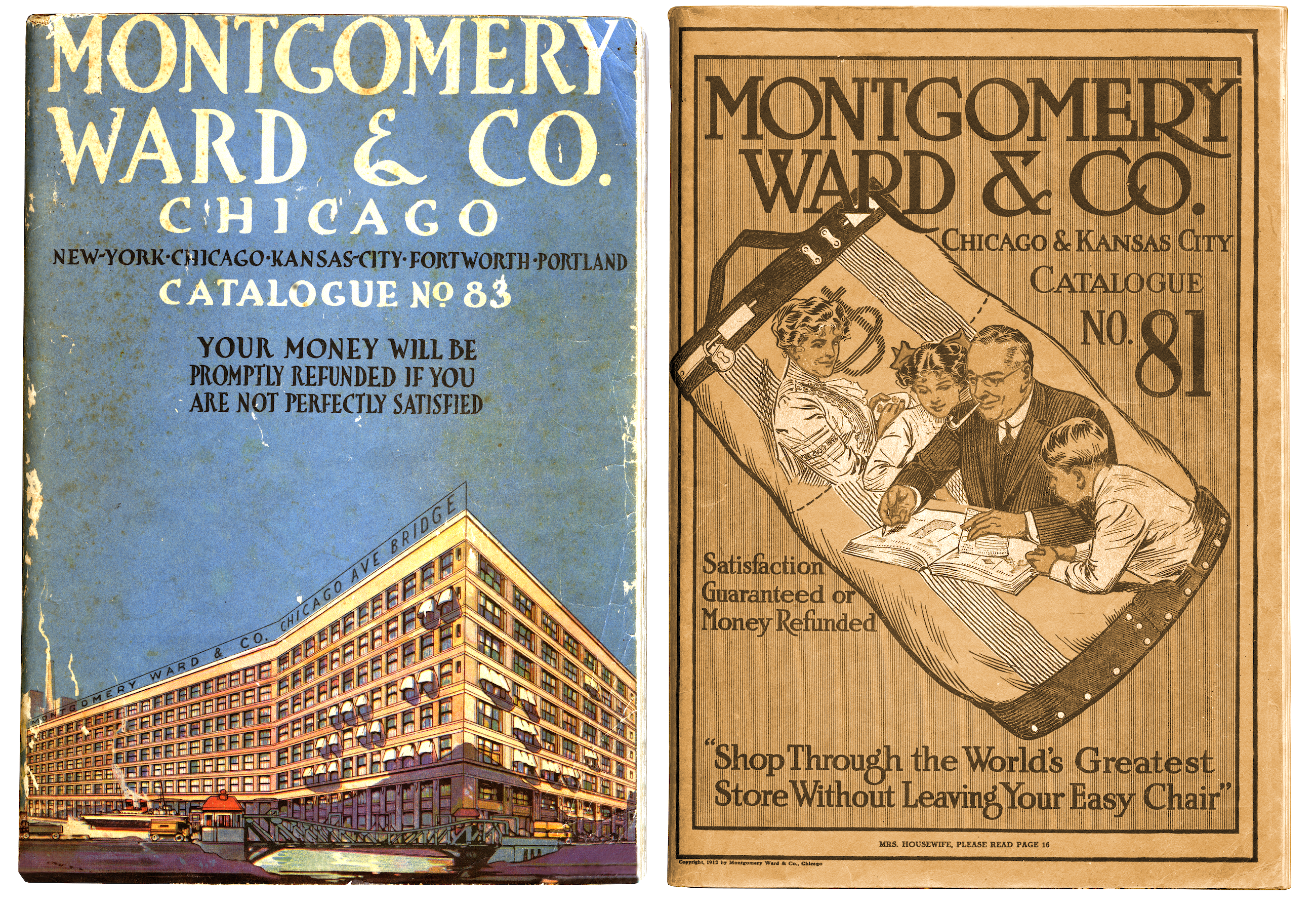

By the end of the century, Sears’s more reckless approach had nonetheless moved them neck and neck with Ward, with the two firms now jockeying for orders and bragging rights. Nationally, the companies tried to one-up each other with increasingly thick and colorfully illustrated mega-catalogs; while locally, they also seemed to be in an architectural competition, each rapidly expanding their downtown warehouses with more elaborate constructions.

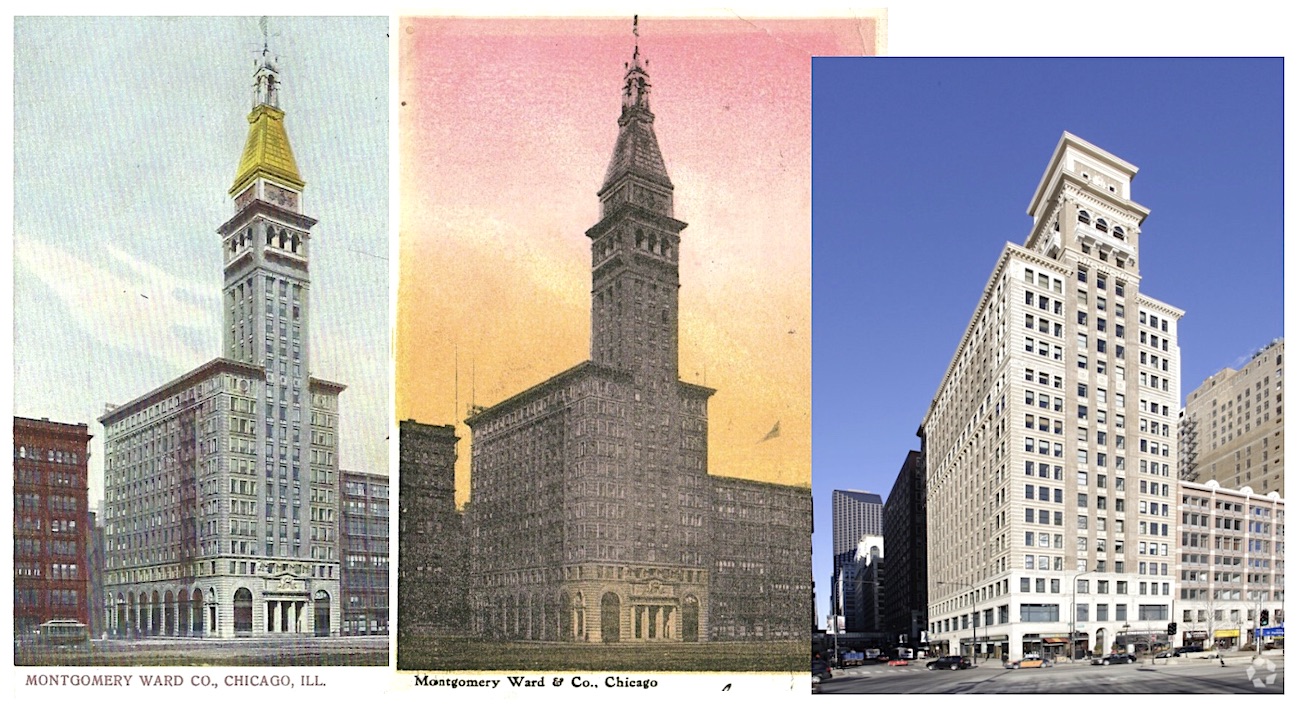

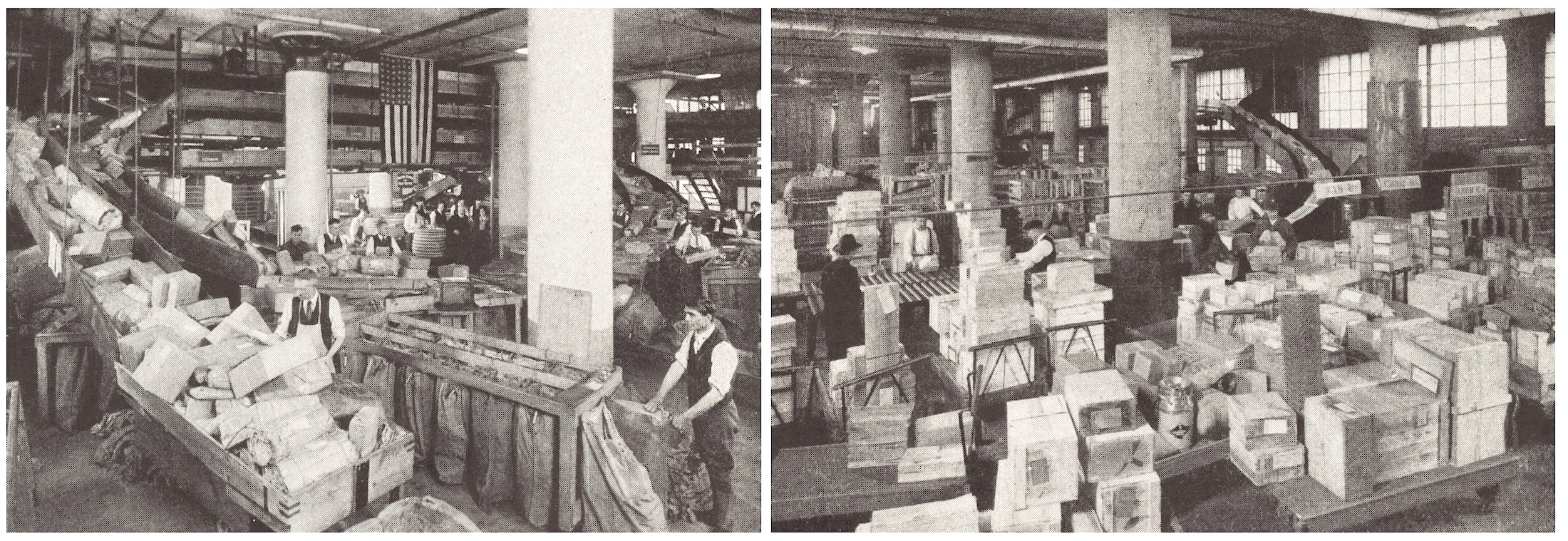

The addition of a 12-story tower to Ward’s Michigan Avenue complex in 1899 certainly signified the health of the company heading into the new century. By 1904, a promotional poster described the $5 million facility as a “Busy Bee Hive” of mercantile efficiency, with more than 3,000 employees now serving 2 million customers annually. “A force of 300 to 500 young ladies do nothing but open the mail and enter the orders. More than 200 correspondents, stenographers and typewriters are busy every day writing letters to friends and customers all over the world.”

The addition of a 12-story tower to Ward’s Michigan Avenue complex in 1899 certainly signified the health of the company heading into the new century. By 1904, a promotional poster described the $5 million facility as a “Busy Bee Hive” of mercantile efficiency, with more than 3,000 employees now serving 2 million customers annually. “A force of 300 to 500 young ladies do nothing but open the mail and enter the orders. More than 200 correspondents, stenographers and typewriters are busy every day writing letters to friends and customers all over the world.”

The tower portion of the Ward building would reign as the tallest in Chicago for the next 20 years (eventually eclipsed by the Wrigley Building in 1922), and its top floor, open-air observatory offered visitors the best view in town, free of charge.

As no coincidence perhaps, Aaron Ward himself had become deeply invested in using his considerable influence to change what that view out across Michigan Avenue would look like—not just for Ward customers, but anyone visiting Chicago in the future.

Over a 20 year period, from about 1890 to 1911, Ward was the single biggest factor in keeping Chicago’s downtown lakefront free of development and obstructions, as the city’s early planners had intended. In defiance of just about all civic leaders of his era, Ward was unique in recognizing the importance of having public park land available to everyone, not just the city’s elite. He helped lead efforts to clean up Grant Park—then known as “Lake Park”— which, since the Great Fire, had become crowded with “unsightly wooden shanties, structures, garbage, paving blocks and other refuse piled thereon.” Later, when Marshall Field proposed building his new natural history museum on the site, Ward dug in his heels again, defending the “open land” ideal. Ward’s multiple lawsuits got him labeled as “an enemy of real parks” by the Chicago Tribune. The newspaper actually went much further than that, calling Ward “a human icicle, shunning and shunned in all but the relations of business.”

[Looking down toward the south end of Lake Park just before it became Grant Park, circa 1900. This is the public land and unobstructed view of the lake that Aaron Montgomery Ward spent 20 years trying to ensure. The Field Museum, originally proposed for the center of Grant Park, was eventually built just south of the park near the Illinois Central Depot, and the use of landfill helped spring the larger museum campus around it.]

Ward was ultimately victorious in his efforts—Lake Park was reborn as Grant Park in 1901, and the Field Museum was built further south on land donated by the Illinois Central Railroad. Clear views across the park would be sustained, and appreciated, for the next century, and Aaron Ward would be remembered for his role in making it happen—even if nobody was giving him credit for anything in his own time.

“I think there is not another man in Chicago who would have spent the money I have spent in this fight with certainty that even gratitude would be denied as interest,” Ward said in 1909, noting that he “fought for the poor people of Chicago, not the millionaires. . . . Here is a park frontage on the lake, comparing favorably with the Bay of Naples, which city officials would crowd with buildings, transforming the breathing spot for the poor into a showground for the educated rich. I do not think it is right. . . . Perhaps I may yet see the public appreciate my efforts. But I doubt it.”

[Grant Park as it looked in the mid 1920s, with the former Montgomery Ward tower building looming in the background]

[The original Montgomery Ward Tower building at 6 North Michigan Avenue, built in 1899, is still standing today. It’s less recognizable, as the addition of four floors to the lower portion of the building, followed by the removal of the top pyramid portion, proved a considerable facelift. The building was only Ward’s headquarters for 10 years, as most workers moved to the building at 600 West Chicago Avenue by 1910.]

III. Game of Thornes

“The Montgomery Ward & Co. plan of retailing all kinds of goods around the world has extended the name of Chicago into every civilized land. Not only does our business reach every state, county, city, and hamlet, and nearly every farm in the United States, Canada, West Indies, Mexico, and throughout North America, but it also extends around the earth—six carloads of merchandise a week being our average shipments to the Orient, Australasia, and Trans-Pacific point; a carload a week to each, South Africa, South America, India, Canal Zone, Central America and Cuba; in addition to which an average of a ton of merchandise leaves the house daily by mail for foreign parts.” —Montgomery Ward & Co. ad, 1910

Aaron Montgomery Ward died in 1913, and while he might not have seen public appreciation for his land conservation work, he did live long enough to see the construction and completion of his company’s most ambitious headquarters to date.

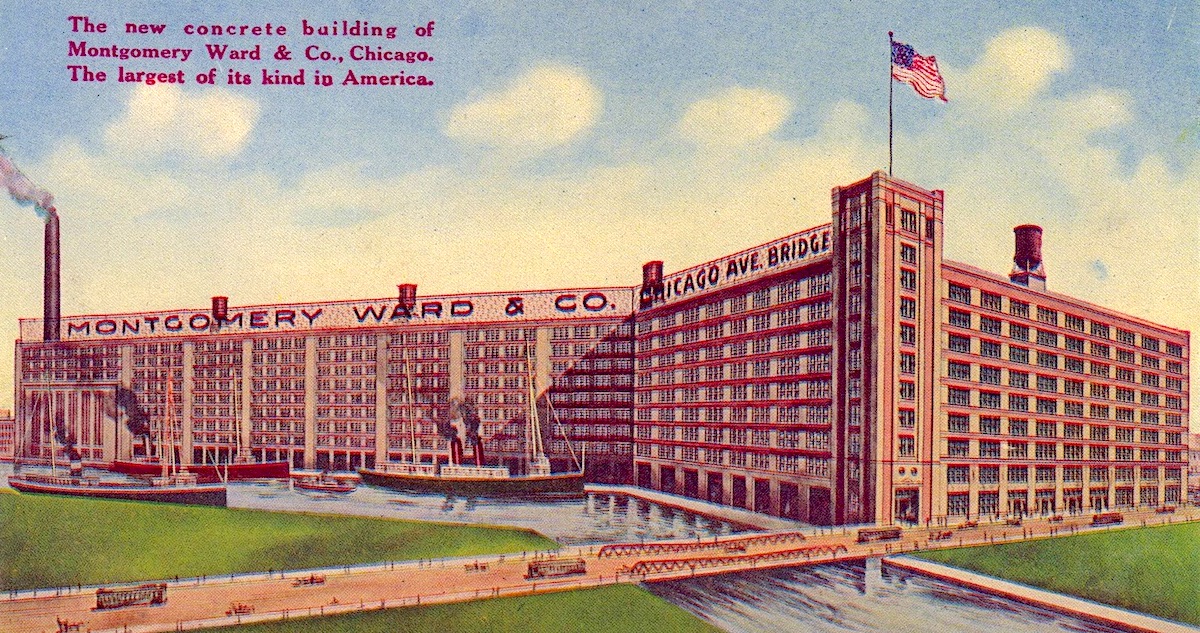

In 1908, with even its massive Michigan Avenue building no longer fit to handle its enormous order volume, Ward & Co. began relocating to a new eight-story, 2-million square foot, concrete-reinforced headquarters located along the north branch of the Chicago River— at what is now 600 West Chicago Avenue.

In 1908, with even its massive Michigan Avenue building no longer fit to handle its enormous order volume, Ward & Co. began relocating to a new eight-story, 2-million square foot, concrete-reinforced headquarters located along the north branch of the Chicago River— at what is now 600 West Chicago Avenue.

“Our new Chicago Avenue Building is said to be the largest structure in the world—fifty acres under one roof,” read one 1909 ad, which also promoted the company’s first walk-in retail outlet, visitable within the same complex.

With Aaron Montgomery Ward mostly in retirement in California, the new building was in many ways the achievement of (and metaphorical torch to carry) for his successors, the Thorne family. By the time the company fully relocated to the riverfront plant in 1910, its annual profits had topped the million dollar mark for the first time, and its daily operations were largely handled by the five sons of Ward’s old business partner George Thorne.

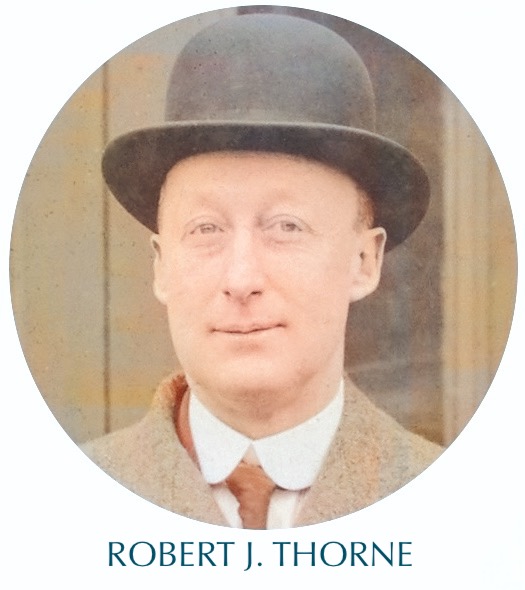

George’s eldest son William C. Thorne (b. 1864), who’d started working in the catalog department way back in the 1880s, was now company president; Charles H. Thorne (b. 1869) was treasurer; and idea-man Robert J. Thorne (b. 1875) was the young vice president (the two other brothers, George and James Thorne, were also board members). This new generation, coming up in the days of Teddy Roosevelt and his “Square Deal,” launched a campaign to further distinguish Ward & Co. from what they saw as its sleazy, underhanded competition over at Sears—the company that was now regularly winning the mail order wars.

“You’ve got to admire a business that’s run on the square,” read an intro page to Ward’s 1916 catalogue. “Every man in this house has got to be as square as men are made. This takes in everybody from the President to the office boy. . . . Cunning tricks don’t go here any more than downright dishonesty. And where every solitary man is strictly on the square, you can’t get anything but a square deal. That kind of principle can’t be beaten.”

[“Many big stores rolled into one lie in your lap as you read this,” read the intro to the 1916 Ward catalogue]

[The shipping rooms of the Chicago Avenue complex, circa 1920]

Robert Thorne, who took over the presidency after his brother William’s untimely death in 1917, liked to project an image of ethical superiority, but his own track record wasn’t sparkling. Back in 1905, while still a young executive fresh out of Cornell, he was accused of bribing Chicago transport companies to lock out local Teamsters during a season of intense and violent labor strikes in the city. Union leaders later claimed that Thorne had also bribed them to organize strikes against Montgomery Ward’s competition; namely Sears, thus stoking the flame.

In terms of his more positive character traits, Robert Thorne was a crafty logistical mind who helped expand and streamline the Ward network, much as Julius Rosenwald did for Sears during the same period. In the 1910s, Thorne took the Ward stock public for the first time; helped oversee the opening of new distribution centers in Kansas City, Portland (OR), and Fort Worth (TX); and organized the rollout of a novel benefits program for Ward employees, including group health insurance coverage. During World War I, Robert also put his experience to use as a volunteer for the U.S. Army, improving its outdated logistics and supply systems. His superior officer was a certain brigadier general named Robert E. Wood, whom Thorne would hire as a Montgomery Ward executive after the war.

In January of 1920, despite an extremely profitable 1919 Christmas season, Robert Thorne seemed to anticipate complications in the new decade. “The difficulties one sees ahead should only encourage him to put his head a little higher in the air and walk more firmly and courageously,” Thorne told Colliers magazine.

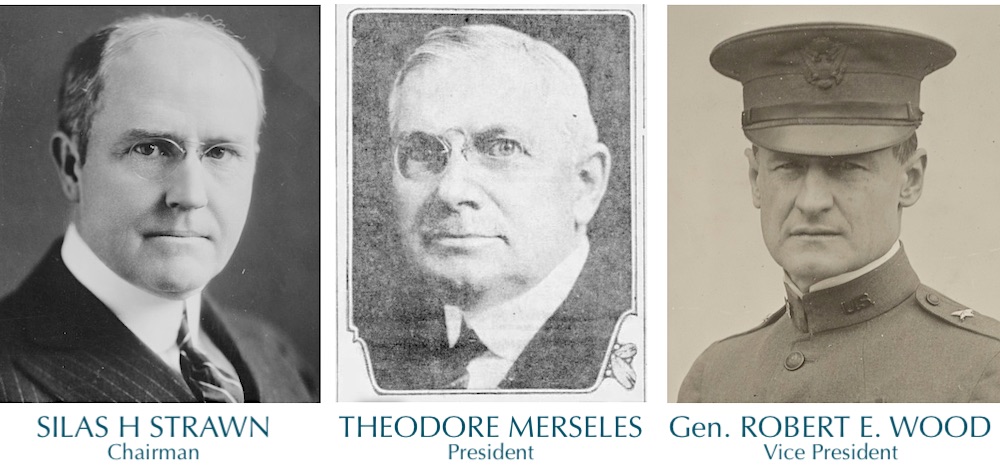

Within a few months, it was officially announced that Montgomery Ward & Co. had been acquired by a new corporate conglomerate, led by retail magnate George Whelan of the United Retail Stores Corporation with financial backing from J. P. Morgan and James B. Duke of the American Tobacco Co. The Thorne brothers were retained as directors, but the direction of the business in the 1920s would soon be determined by all-new leadership. Prominent Chicago lawyer Silas Strawn would become Ward’s chairman. Theodore Merseles—former VP of the National Cloak & Suit Co.—was its president, and the aforementioned General Robert E. Wood was VP.

The new team got off to a soaring start in the Jazz Age, pulling Ward & Co. out of an inflation-based slump and riding dominant fashion, auto part, and radio sales to $10 million profits—nearly catching up with Sears. The honeymoon was brief, however.

“The president [Merseles] and I just didn’t get along,” Robert Wood later recalled in a 1954 interview. “He wanted to use retail stores as an outlet for surplus goods. I wanted them to be an important part of the company. We agreed to separate.”

This split became the ultimate turning point in the history of 20th century American retail, as General Wood famously jumped ship to Sears—building it into the biggest chain department store in the country—while Ward & Co. was left to play catch-up once again heading into the challenging 1930s.

[Top Left: Some of the messenger boys at the sprawling Montgomery Ward building on the river used to famously roll through the long hallways on roller skates. Bottom Left: Seven female employees prepare for an office party in 1929. Right: The former Ward complex as it has looked in more recent years, home to offices of Groupon and the Big Ten Network, among others.]

IV. The Bureau of Design

Seeing the success of Sears’ rapidly growing network of brick-and-mortar stores, Montgomery Ward did its best to follow the formula, opening more than 30 stores by 1927, and a whopping 200 more in 1928—many of them located in smaller towns and suburbs rather than big urban centers. With George B. Everitt now in the role of president, Ward’s again hoped to paint itself as the classier alternative to Sears.

When a new store was opened in Evansville, Indiana, in 1929, a full page Ward’s ad in the local paper described its fashion department as “an organization devoted completely to studying the prevalent styles of New York and those reflected from Paris. Immediately upon the appearance of a new vogue, it is designed in Montgomery Ward stores and will be sent at once to Henderson and Evansville, as well as other stores of the Montgomery Ward chain.”

[Left: Exterior of a new Montgomery Ward store in Mineral Wells, TX, 1929. Right: Interior of a Ward store in Bismarck, ND, 1930s]

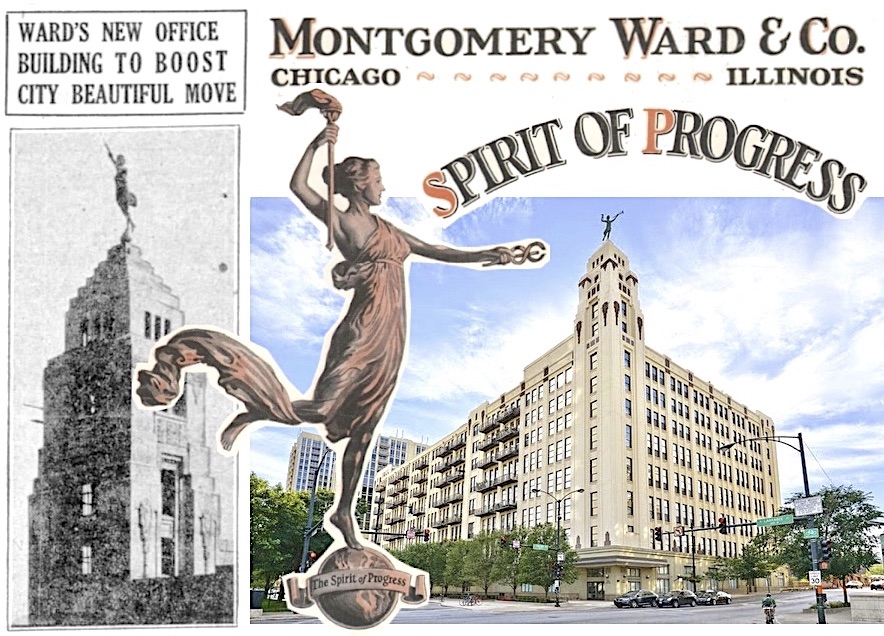

That same year, no expense was spared in completing Ward’s new Administration Building in Chicago at 758 N. Larrabee Street, which was built by the company’s own in-house architectural engineer, W. H. McCaully. On October 27, 1929—two days before the stock market collapsed—the Chicago Tribune praised the advanced features of the new structure, which was set to open that week.

“A heating plant fueled by oil which will not send forth great clouds of smoke into Chicago’s skies. Fire escapes that are concealed within the building, instead of sprawling over the walls. All roof paraphernalia enclosed and architecturally treated. These are a few contributions toward a better looking Chicago found in the new office and retail store building of Montgomery Ward & Co. . . . The structure is eight stories high with a twelve story tower. The tower carries a gilded statue entitled ‘The Spirit of Progress.’”

[Opened in 1929, the former Montgomery Ward Administration Building at 758 N. Larrabee Street is still standing today, and still features the “Spirit of Progress” sculpture at the top of its tower (this was a new version of a similar sculpture that had topped the old Ward tower on Michigan Ave. Copywriter Robert May likely was looking out of a window in this building in 1939 when he saw fog rolling in off the lake and pondered a hero reindeer with a red shiny nose.]

Ward & Co., like most big companies of the time, was blindsided when the economic bubble burst at the end of the 1920s. The company’s arguably out-of-control growth—highlighted by a peak fleet of 556 retail stores in 1930—left it unsurprisingly vulnerable to huge losses as the Depression set in.

After going nearly $9 million into the red in 1931, the company cleaned house, with majority shareholders at J. P. Morgan & Co. installing 57 year-old Sewell Avery as Ward’s new president. Avery was already the longtime president of the United States Gypsum Company, and had a track record of success leading a massive organization. He was also a borderline fascist who was diametrically opposed to the policies of soon-to-be U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt and anything else that might strengthen America’s labor unions.

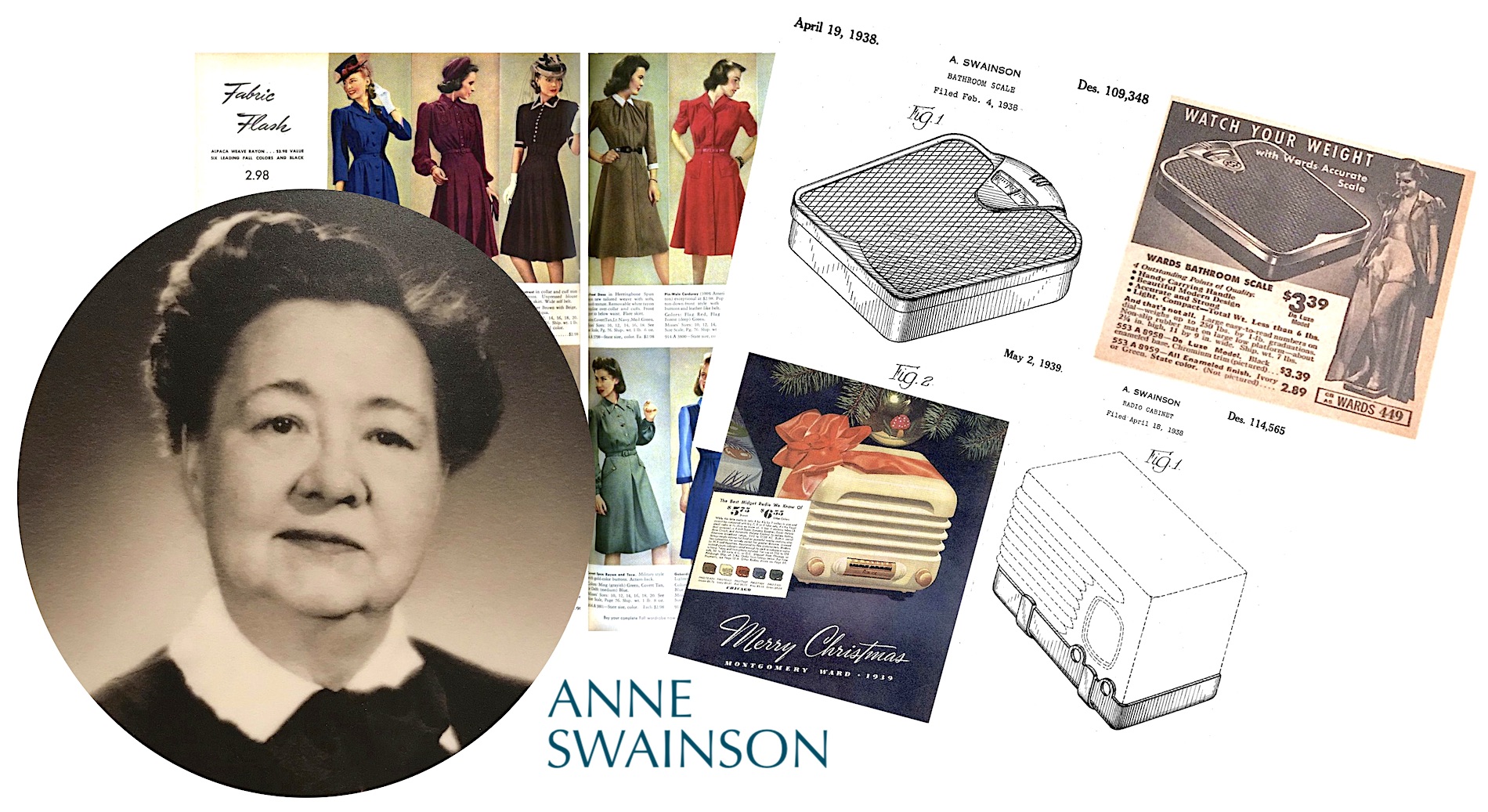

Ironically, despite fighting FDR’s New Deal tooth and nail, Avery’s company was among the big beneficiaries of the program, as profits returned in 1935 and ’36, and Ward leaped from just 25% of Sears’ volume back up to 82%. To Avery’s credit, he also knew how to recruit talent, cut costs, and trim fat—including the closure of more than 100 underperforming retail stores. In a rare instance or two, he was also open to some more progressive ideas when it came to his employees. As mentioned earlier, it was Avery who uncharacteristically agreed to sign over 100% of the rights to “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” to the copywriter who created it, Robert May. Earlier in the 1930s, Avery also oversaw the hiring of Anne Swainson as the director of the company’s new Bureau of Design.

Ironically, despite fighting FDR’s New Deal tooth and nail, Avery’s company was among the big beneficiaries of the program, as profits returned in 1935 and ’36, and Ward leaped from just 25% of Sears’ volume back up to 82%. To Avery’s credit, he also knew how to recruit talent, cut costs, and trim fat—including the closure of more than 100 underperforming retail stores. In a rare instance or two, he was also open to some more progressive ideas when it came to his employees. As mentioned earlier, it was Avery who uncharacteristically agreed to sign over 100% of the rights to “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” to the copywriter who created it, Robert May. Earlier in the 1930s, Avery also oversaw the hiring of Anne Swainson as the director of the company’s new Bureau of Design.

Swainson—who was the first woman to hold a management position with Ward & Co.—was arguably just as instrumental to the company’s recovery as Avery or FDR. While Montgomery Ward still outsourced the manufacturing for nearly all of its house-brand products, the Bureau of Design represented a new way to ensure that a wide range of goods—produced by dozens of different suppliers—could still present a cohesive, consistent, and modern aesthetic . . . hopefully distinct from Sears, JCPenney, or anyone else. Swainson (b. 1888)—a Swedish immigrant who’d made her name with a leading design firm in New York—was recruited by Ward’s new sales manager Walter Hoving (whom Avery had poached from Macy’s). She led a team of highly skilled architects, engineers, artists, and designers, all of whom helped streamline and modernize the look of the Ward catalog and many of the products therein.

“The success of the Bureau,” according to a 1956 article in Industrial Design magazine, “depended, ultimately, on Anne Swainson’s winning the buyer’s confidence, persuading them of the value of better design on the market, and in the management of a business like Ward’s. The Bureau was her baby. She created not only its concept of service but its design attitude by her selection of staff.”

More than 70% of Montgomery Ward’s roughly 35,000 nationwide employees were women, but Swainson was unique among them when it came to power and influence. Like Robert May, though, her enormous success with the company didn’t lead to considerable individual notoriety or bigger and better things. She remained with the Bureau of Design into the 1950s, as Sewell Avery gradually abandoned his investment in the department, and she died—still a Ward employee—in 1955, aged 67.

V. Avery vs. Roosevelt

“I find it almost irresistible to fight what I think is an injustice. To do so satisfies something within me. You don’t have to believe me when I say that I am not dominated by financial considerations. It just happens to be the case.” —Sewell L. Avery, Montgomery Ward president, 1944

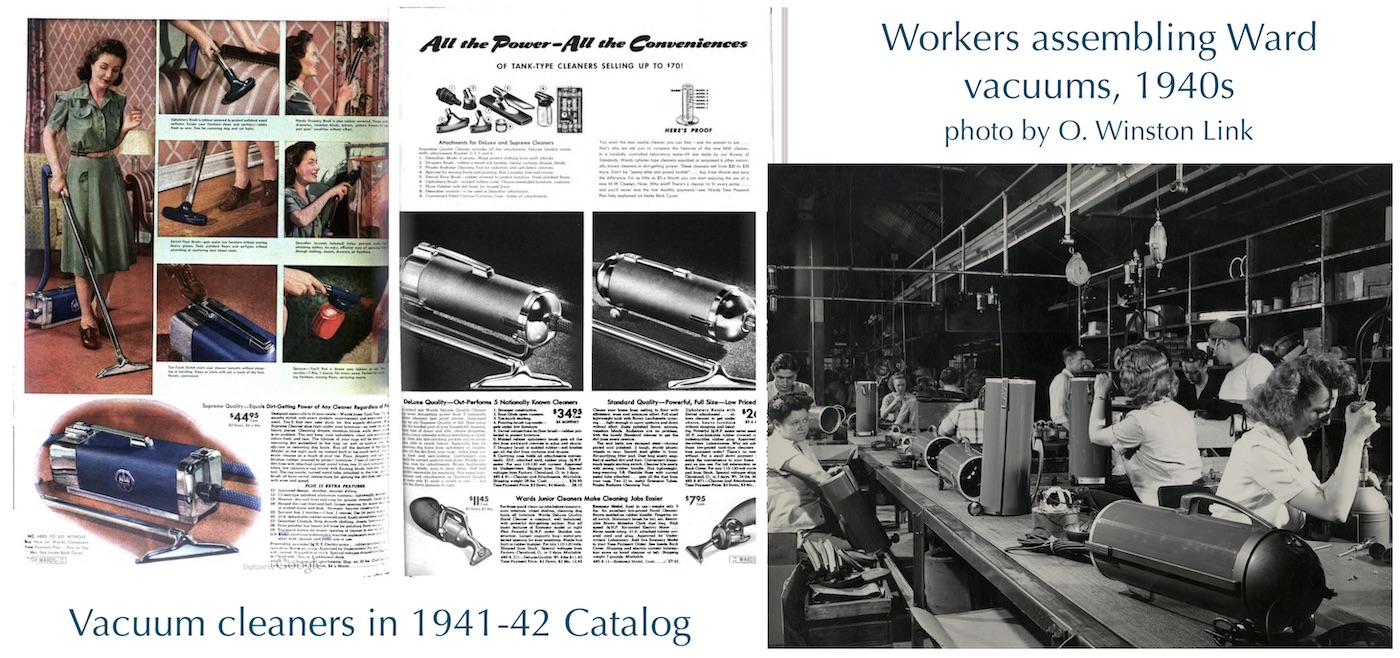

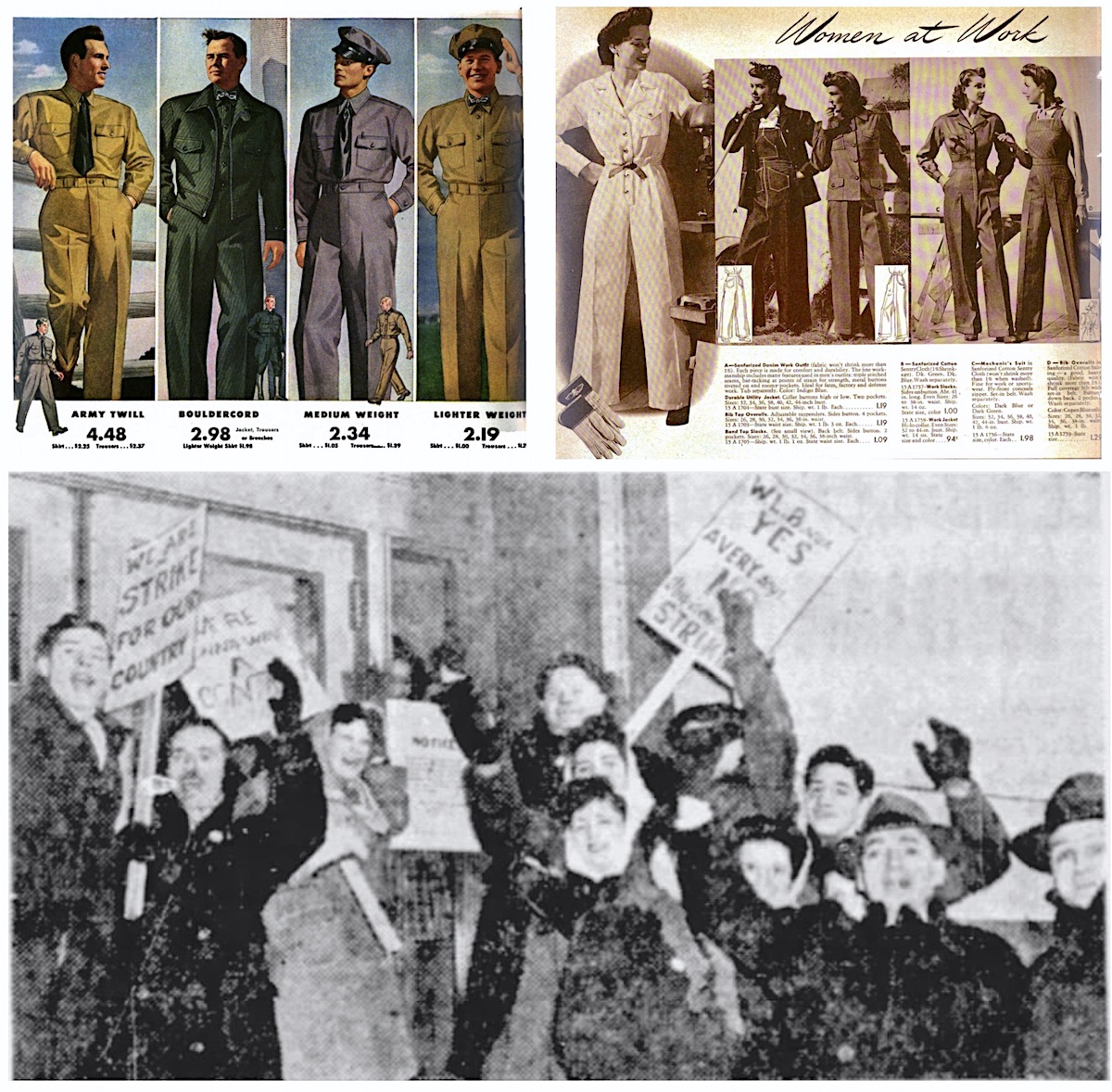

During World War II, Montgomery Ward & Co. continued to employ more than 75,000 men and women, including 6,800 in the Chicago headquarters alone, and it was actively supplying important parts, supplies, and clothing to the Allies (Ward also now owned three actual production factories: a paint and varnish plant in Chicago Heights, a fencing plant in Fort Madison, Iowa, and a farm equipment factory in Springfield, IL, where carburetors, propellers and gun mounts were being built for military aircraft). But while the company’s high-profile president Sewell Avery spoke often about patriotism and liberty, he was simultaneously fighting a separate war of his own against Franklin Roosevelt and the National War Labor Board. In fact, FDR had to repeatedly distract himself from addressing the likes of Hitler and Mussolini in order to deal directly with the defiant mail order magnate in Chicago.

During World War II, Montgomery Ward & Co. continued to employ more than 75,000 men and women, including 6,800 in the Chicago headquarters alone, and it was actively supplying important parts, supplies, and clothing to the Allies (Ward also now owned three actual production factories: a paint and varnish plant in Chicago Heights, a fencing plant in Fort Madison, Iowa, and a farm equipment factory in Springfield, IL, where carburetors, propellers and gun mounts were being built for military aircraft). But while the company’s high-profile president Sewell Avery spoke often about patriotism and liberty, he was simultaneously fighting a separate war of his own against Franklin Roosevelt and the National War Labor Board. In fact, FDR had to repeatedly distract himself from addressing the likes of Hitler and Mussolini in order to deal directly with the defiant mail order magnate in Chicago.

Well before Pearl Harbor, Avery—a tough talking multi-millionaire—had established himself as a staunch opponent of the New Deal and, in particular, the growing influence of labor unions. He likely instituted racist hiring policies, as well, as Ward’s was accused of “flagrant discrimination against minority groups” in one complaint filed by Local 20 of the United Retail, Wholesale & Department Store Employees. “The only jobs open to Negroes in the Chicago properties of Montgomery Ward,” according to the union’s 1944 memorandum, “are those of porter, bus boy, bus girl, elevator operator and matron. The bulk of mail order house, retail store and warehouse jobs are therefore closed [to them].”

[While selling uniforms for “Victory Workers” in its own catalog, Montgomery Ward faced rising pushback from its employees, as seen in the 1944 strike outside the Chicago warehouse, pictured above.]

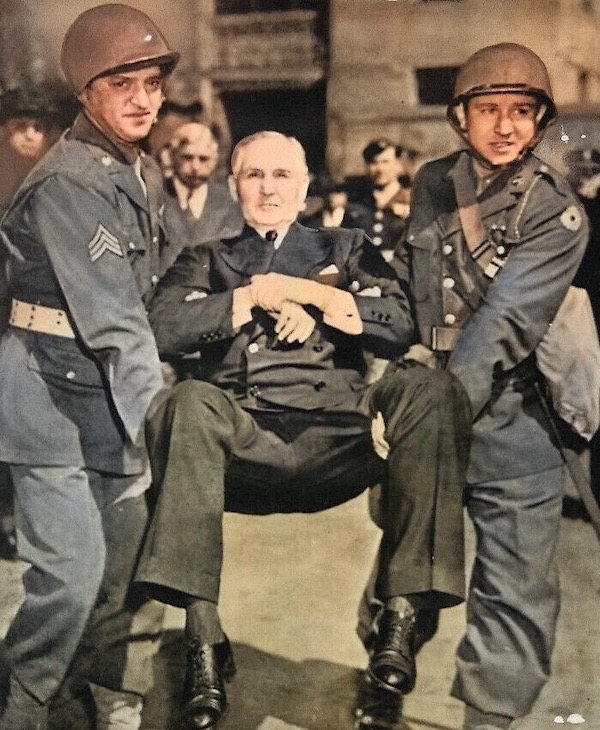

Now, under the new wartime powers granted to Roosevelt and the War Labor Board, Avery would be forced to collectively bargain with union leaders. This same policy was applied to large employers across the country, with the goal of sustaining wartime production by preventing all labor strikes and lockouts. Avery, however, was incensed at what he considered blatant government overreach, and he repeatedly challenged FDR in the form of lawsuits, national ad campaigns, and personal letters.

Roosevelt eventually lost patience himself, and in April of 1944, he took drastic action, ordering the seizure of Montgomery Ward’s Chicago offices and the direct removal of the 69 year-old Avery, who was literally carried out on to the street by two members of the National Guard.

A press photo of the incident, with Avery showing a sort of pompous indignation—arms folded as the two soldiers extracted him from his own office—landed in every major newspaper in America, and stoked weeks of heated debate among businessmen and the wider public.

“In this picture half the great social and political issues of America’s last ten years lie riven and exposed, their ends twitching,” read an editorial in Life magazine. “None of them is solved by it . . . But Sewell Avery’s flash of synthetic martyrdom will rest immortal in the files.”

Avery remained at the helm of Ward’s for another decade, but his stubbornness continued to damage the brand after the war, as he remained convinced of a new, imminent economic depression, rather the post-war boom that each passing year clearly documented. Sears left Ward in the dust, with triple the sales numbers, and in 1954, the elderly Avery was finally ousted by rival shareholders, replaced as president and chairman by lawyer John Barr.

VI. Slow Demise of the Old Behemoth

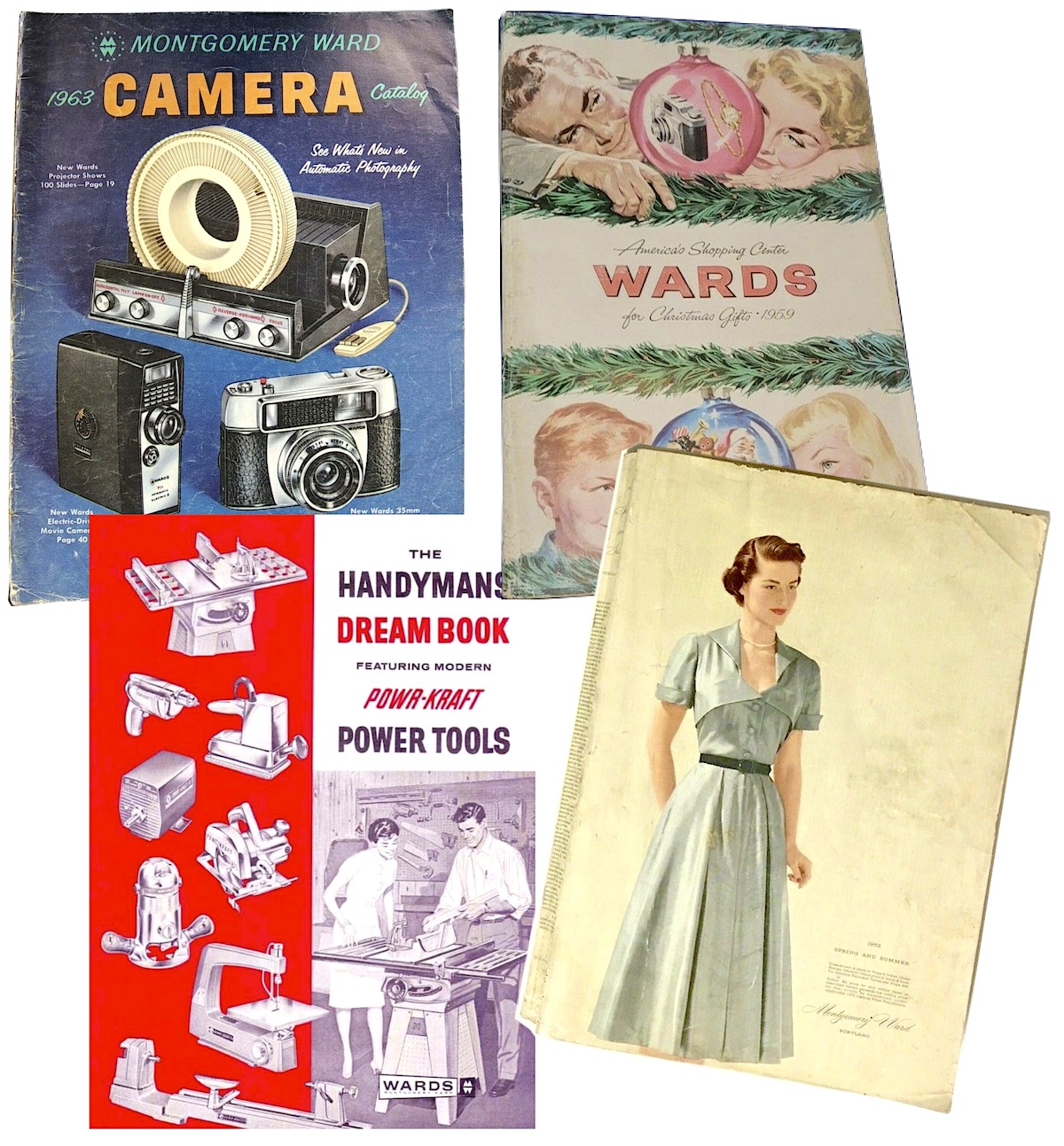

John Barr took over an 80 year-old retail business that still operated 600 stores, but hadn’t opened a new one in a decade. Meanwhile, the mail order business—now 40% of the company’s sales—was slowly sinking. The new U.S. highway system was bringing the shopping experience directly to middle America’s doorstep, and there was simply decreasing interest and appeal in Ward’s famous “Wish Book.”

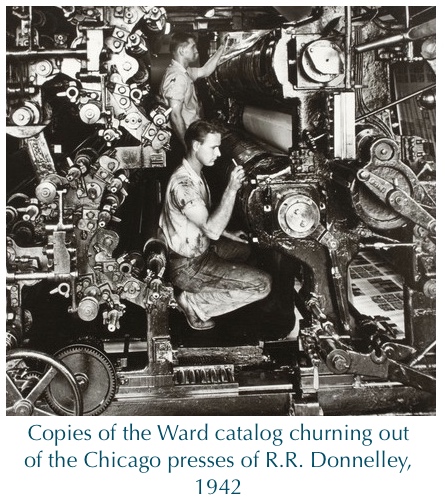

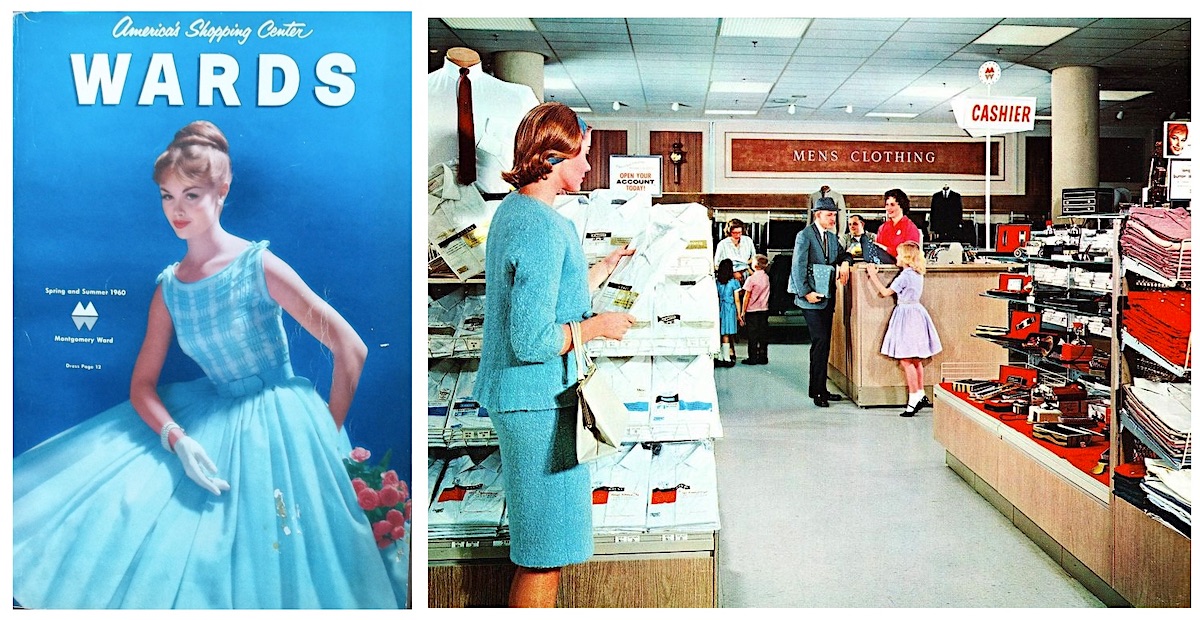

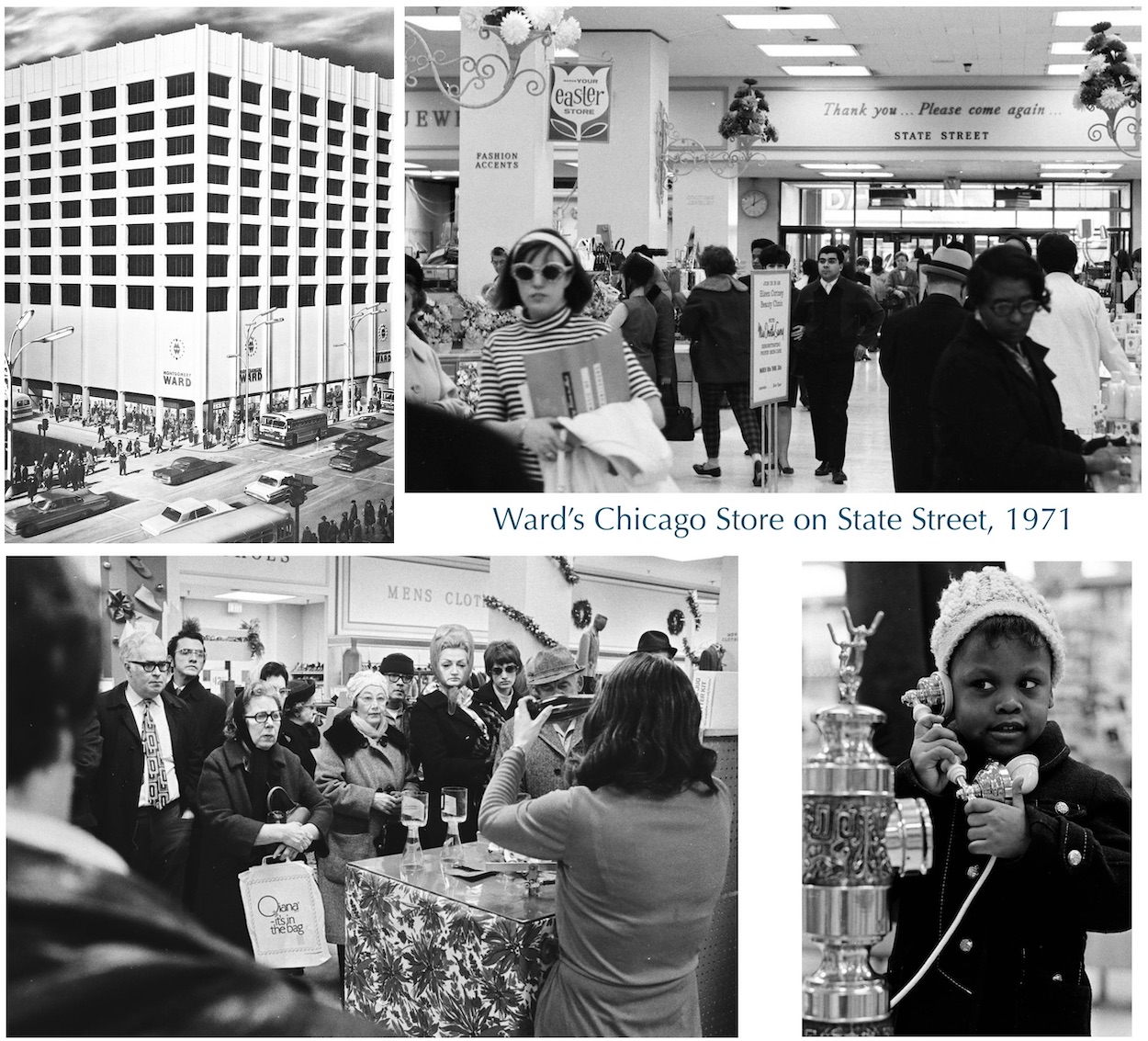

Montgomery Ward wasn’t exactly going down like a lead balloon, though. As folks of the Baby Boom generation will recall, the company had one last run left in them, as they rebuilt their infrastructure, opened fancy new department stores in the country’s rapidly sprouting suburban shopping malls, and produced upwards of 45 million catalogs a year: a big spring and fall issue, and a bunch of specialized issues: Automotive, Christmas, Farm & Garden, Photographic, Sporting Goods, Toys, and even Power Tools, among others (most were still produced by Ward’s longtime Chicago printing partner, R. R. Donnelley).

Montgomery Ward wasn’t exactly going down like a lead balloon, though. As folks of the Baby Boom generation will recall, the company had one last run left in them, as they rebuilt their infrastructure, opened fancy new department stores in the country’s rapidly sprouting suburban shopping malls, and produced upwards of 45 million catalogs a year: a big spring and fall issue, and a bunch of specialized issues: Automotive, Christmas, Farm & Garden, Photographic, Sporting Goods, Toys, and even Power Tools, among others (most were still produced by Ward’s longtime Chicago printing partner, R. R. Donnelley).

Sales topped $1.2 billion in 1960. The trouble was, that was only about 1/4 of Sears’s totals, and the actual profits were still stuck down around $15 million.

In another move to try and shake things up, Barr brought in a Sears exec—Whirlpool president Robert E. Brooker—to sprinkle some of the Sears magic on Montgomery Ward. Nobody had yet realized that Sears Roebuck was on borrowed time in its own right, and for much of the 1960s, copycatting the Sears playbook actually worked well enough—Ward built up more in-house brands and shut down more of its old failing stores in favor of new ones near faster growing urban centers out west. And yet still, despite $1.7 billion in sales in 1966, profits stayed down at $16.5 million.

[Above: Ward’s 1960 catalog and a store promotional photo from 1963. Below: Christmas shopping scenes, 1971, inside Ward’s store on State Street in Chicago (which had been converted from an early department store known as The Fair)]

In an action typical of the time period, Montgomery Ward merged with the Container Corporation of America in 1968, and seven years later, the Mobil Corporation took a controlling interest. Various experiments were made to revamp the stores and the catalog, including a new subset of quality discount shops under the Jefferson-Ward name, but it was a case of spinning plates—every new store that proved successful also added to Ward’s mounting costs, as its 100 year-old foundation started to crumble. The nickname “Monkey Wards,” once used lovingly by shoppers, evolved into something a bit more derisive as their experience declined and better options sprouted up.

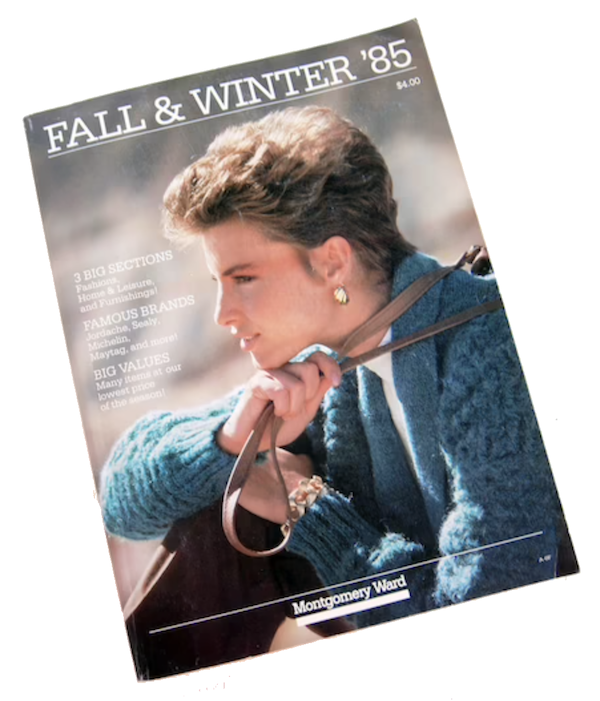

The famous Montgomery Ward mail-order catalog was printed for the final time in 1985, and new CEO Bernard Brennan rolled out a plan to redesign the remaining 300 retail stores once again, dividing each into four “stores within a store”: apparel, home furnishings & accessories, electronics & appliances, and automotive goods. Once again, the change led to a temporary rebound, and even record profits of $153 million in 1990. But that was the final bow. Wal-Mart and Target pummeled the stumbling old giant in the 1990s, and parent company GE Capital finally put Ward’s to bed after the Christmas season of 2000, announcing the closure of all 250 of its remaining stores—and its Chicago offices.

The famous Montgomery Ward mail-order catalog was printed for the final time in 1985, and new CEO Bernard Brennan rolled out a plan to redesign the remaining 300 retail stores once again, dividing each into four “stores within a store”: apparel, home furnishings & accessories, electronics & appliances, and automotive goods. Once again, the change led to a temporary rebound, and even record profits of $153 million in 1990. But that was the final bow. Wal-Mart and Target pummeled the stumbling old giant in the 1990s, and parent company GE Capital finally put Ward’s to bed after the Christmas season of 2000, announcing the closure of all 250 of its remaining stores—and its Chicago offices.

A headline in the December 29 issue of the Tribune that year claimed that “Wards’ end brings little grief to area business, civic leaders,” noting that most observers were pleased to see the struggling company give up its real estate to stronger up-and-coming stores like Kohls or Target. A letter to the editor several days later, however—written by the president of the Illinois Retail Merchants Association, David F. Vite—took a very different tone.

“It’s easy to say, yes, other stores will come in and fill in the vacancies,” Vite wrote. “But it isn’t easy for thousands of employees at Wards’ national headquarters to find new jobs. The closing of Wards ends 128 years, not only of service to customers but of service through civic affairs.”

[An abandoned Wards catalog store in Checotah, Oklahoma. Photographed in 2019 by Charles Hathaway]

Besides the oft-mentioned contributions of Aaron Ward’s protection of the lakefront or Robert May’s creation of Rudolph, Vite also mentioned “the hundreds of tutors Wards and its employees supplied to Cabrini-Green residents for more than 30 years, or the tens of thousands of coats that Wards supplied to the less fortunate. In addition, Montgomery Wards’ charitable foundation provided millions of dollars over the years to Chicago-area charities. . . . On its deathbed, Montgomery Ward should be saluted for the contribution it has provided Chicago and its customers throughout the United States during its tenure. It is a sad day when we stand at the ‘wake’ of a homegrown corporate giant and suggest there is little grief in its demise.”

Shortly after Ward’s closure, both its original tower building on Michigan Avenue and the mighty catalog house on Chicago Avenue were fully renovated—the former as condos, and the latter as corporate offices. The Montgomery Ward brand name and other intellectual property were also purchased and resurrected in recent years, with a new online and mail-order presence under the ownership of Colony Brands, Inc. The new entity has no true connection to the original organization.

Click the image below to flip though the entire 1939 Rudolph booklet:

Rudolph-1939-book-scans

[Ward catalogues No. 81 and 83, seen above, are both part of the Made In Chicago Museum’s collection.]

Sources:

Montgomery Ward Catalogues No. 13 (1875), No. 84 (1916), No. 93 (1920), No. 135 (1941)

“The Originators of the Mail Order Business” (Montgomery Ward ad) – The Inter Ocean (Chicago), May 19, 1901

“Earnings in the Mail Order Business” – Printers Ink, March 5, 1914

“Montgomery Ward Opens at Henderson” – Evansville Press (IN), August 8, 1929

“Ward’s New Office Building to Boost City Beautiful Move” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 27, 1929

“Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer is New Juvenile Fiction Hero” – Sedalia Democrat (MO), Dec 10, 1939

“Avery vs. US” – Life, May 8, 1944

“United States vs. Montgomery Ward & Co.” – U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois – 58 F. Supp. 408 (N.D. Ill. 1945)

January 27, 1945

“General Wood, 74, Quitting Chairmanship of Sears” – Tacoma Sunday News Tribune, April 25, 1954

“Montgomery Ward: Bureau of Design” – Industrial Design magazine, October 1956

“Highlights of Montgomery Ward’s 90 Years of Growth and Progress” – Warren Times Mirror (PA), Sept 11, 1962

Forever Open, Clear and Free: The Struggle for Chicago’s Lakefront, by Lois Wille, 1972

“Robert May Tells How Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer Came Into Being” – Gettysburg Times, Dec 22, 1975

The First Hundred Years are the Toughest: What We Can Learn from the Century of Competition Between Sears and Wards, by Cecil Hoge, 1988

“Montgomery Ward & Co., Inc.” – Encyclopedia.com

“Parent Throws in Towel on Retailer” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 29, 2000

“Respect Wards’ Contributions” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 3, 2001

Founders of American Industrial Design, by Carroll Gantz, 2014

“Anne Swainson: The Making of a Design Pioneer” – Innovation, Spring 2016

HAVE A OIL PANTING 12×10 WITH A OLD WOODEN

WHEEL BORROW WITH MONTGOMERY WARD CO WORDS ON IT BY A OLD ORK TREE / I CAN SEEN PICTURE…

I have a round disk looking thing with two ears one on each made out of old castlooks like the 60

Montgomery Ward camping trailer Model AX 9823B

I have this trailer and have not used it in a long time. Do you have a display for Montgomery Ward in your museum? Would you be interested in displaying this camper. I have pictures. Send me an email.

I have a 1978 MW microwave that I still use every day. Does the museum want it? Time for a new one!

My family had an artist who worked for Montgomery Ward. His name was Art Quentin back in the 1940s if not earlier. Do you have any documentation of his work? That would be fantastic to see!

Hi! I have a well kept set of the Rufus Family lions (stuffed animals) from about 1972. They were ordered from the Montgomery Ward catalog. I wonder if there’s a Montgomery Ward Museum of sorts that houses old MW products and displays them. I could also just send along some pics! Thank you.