Museum Artifact: Johnsons Ice Skates, c. 1960s

Made By: Nestor Johnson MFG Co., 1900 N. Springfield Ave., Chicago, IL [Hermosa / Logan Square]

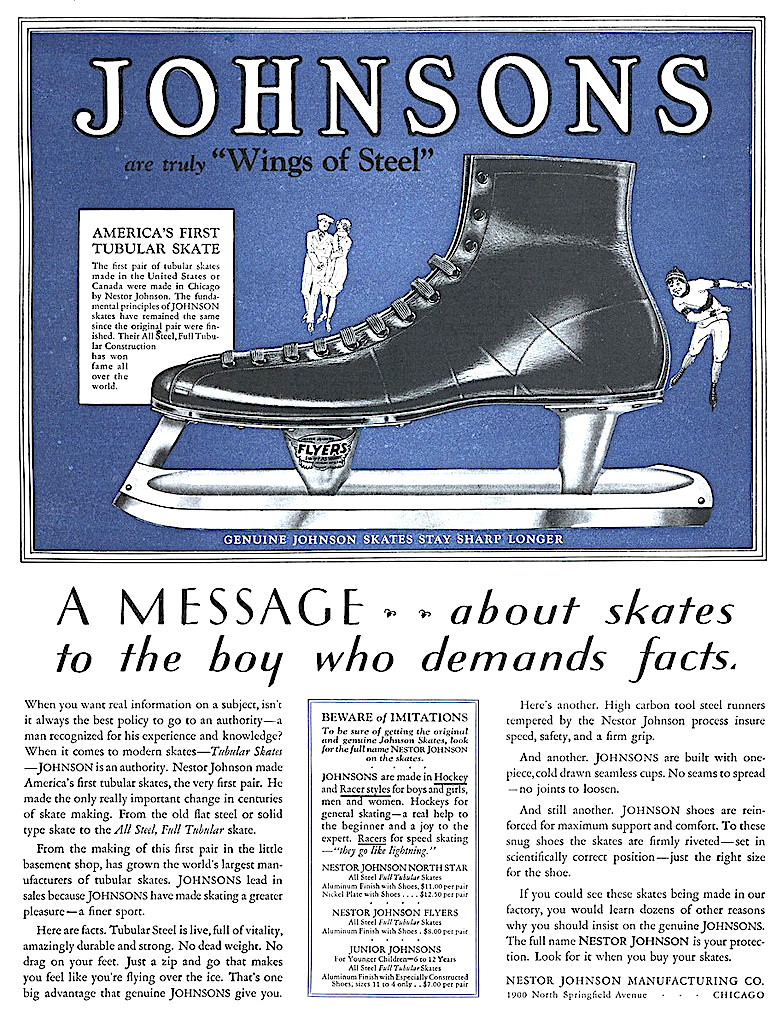

“The first pair of tubular skates made in the United States or Canada were made in Chicago by Nestor Johnson. . . . He made the only really important change in centuries of skate making. From the old flat steel or solid type skate to the All Steel, Full Tubular skate. From the making of this first pair in the little basement shop, has grown the world’s largest manufacturers of tubular skates. JOHNSONS lead in sales because JOHNSONS have made skating a greater pleasure—a finer sport.” —Nestor Johnson MFG Co. advertisement in Boy’s Life, 1927

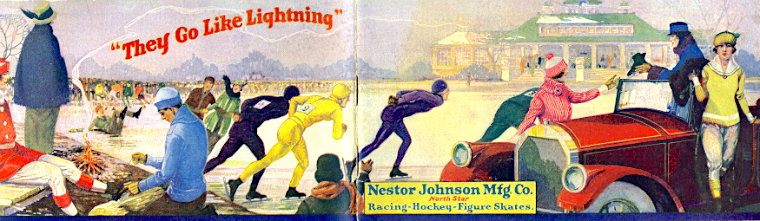

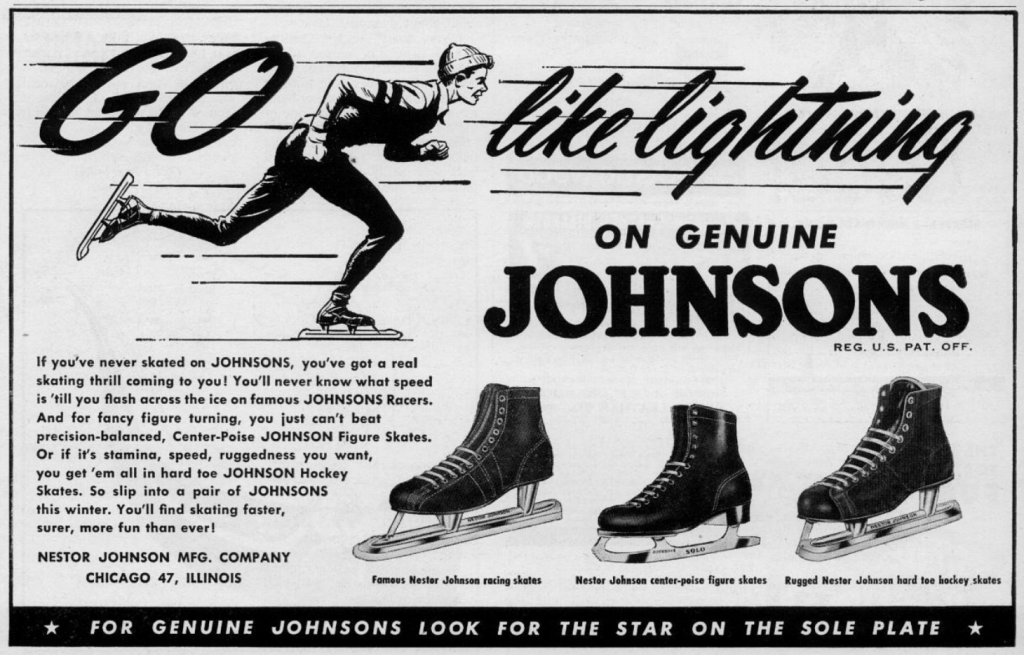

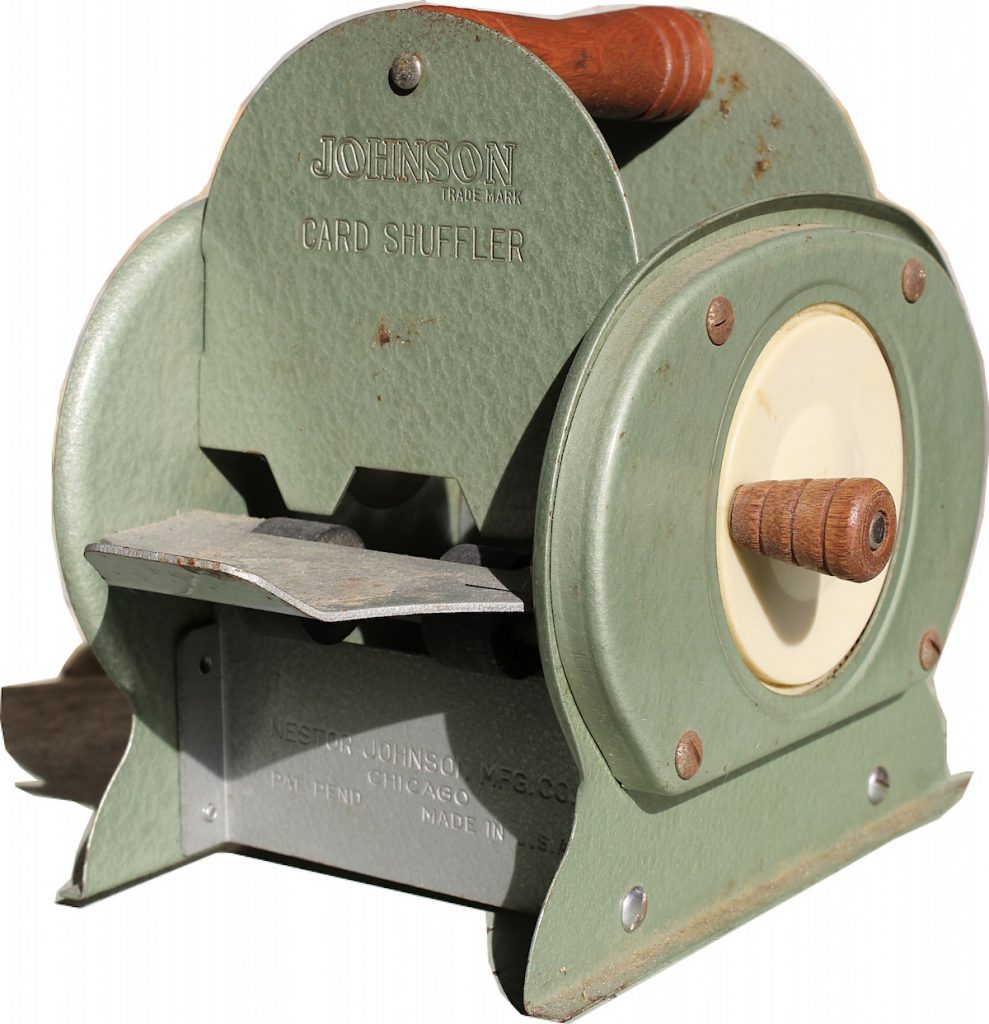

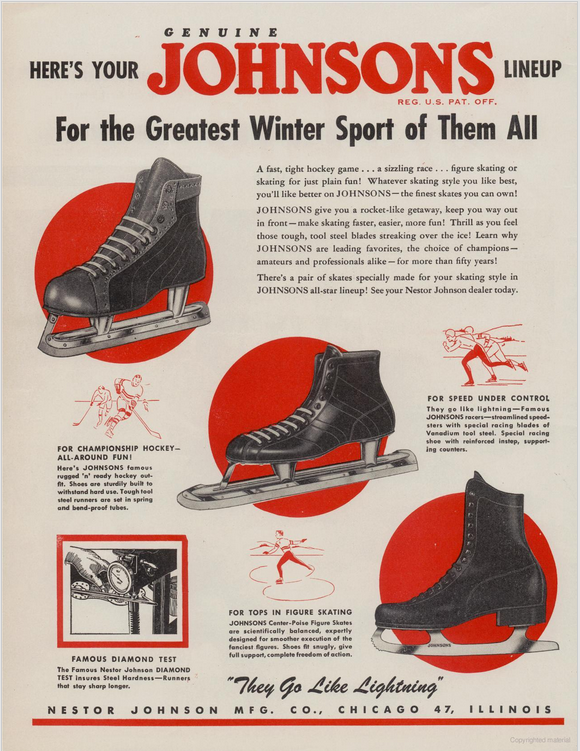

While our museum collection also includes one of their snazzy 1950s playing card shufflers, the Nestor Johnson MFG Company was always—first and foremost—an ice skate manufacturer, and the speed skates we have on display are a pretty representative example of their mass-produced, mid-century blades (“They Go Like Lightning!”).

While our museum collection also includes one of their snazzy 1950s playing card shufflers, the Nestor Johnson MFG Company was always—first and foremost—an ice skate manufacturer, and the speed skates we have on display are a pretty representative example of their mass-produced, mid-century blades (“They Go Like Lightning!”).

For decades, this company was one of Chicago’s “Big Three” names in the skate making biz, alongside F.W. Planert & Sons and Nestor’s own inner-family nemesis, the Alfred Johnson Skate Co. All three rivals were located in the northwest of the city, and all three were ultimately done in less by each other, and more by cheaper imports.

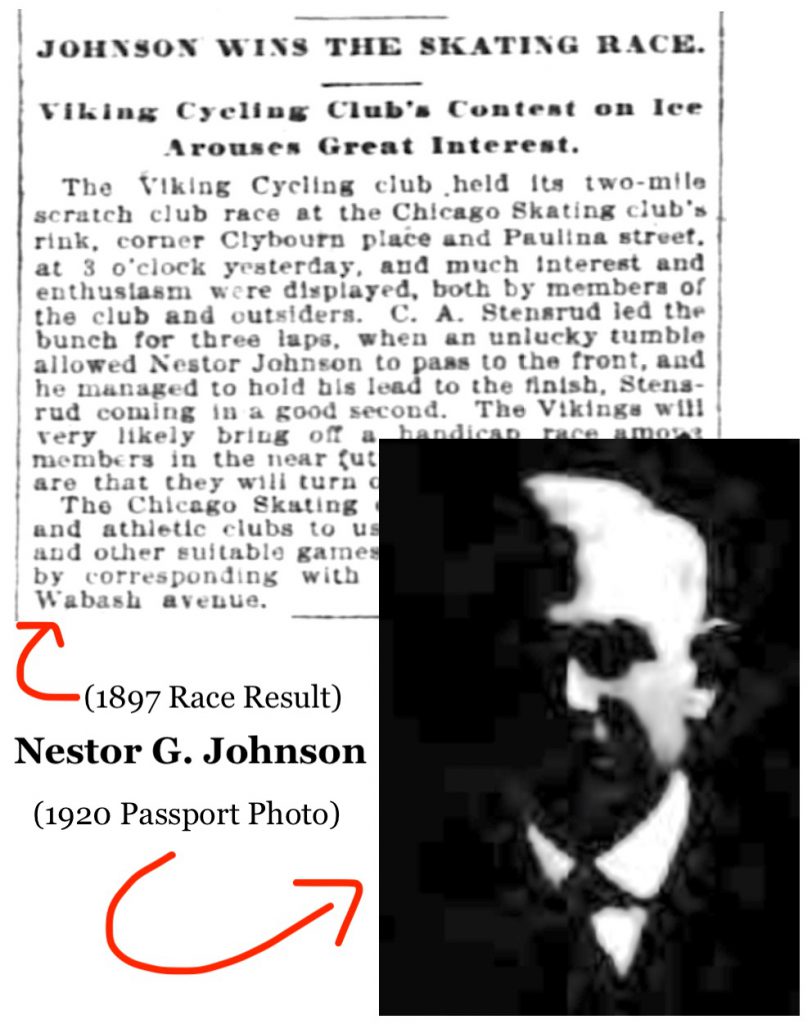

Nestor Johnson, the company founder and namesake, was born Nestor Georg Johansen in Oslo, Norway in 1867. Uniquely gifted as both a mechanic and sportsman, he came to America at the age of 20, and quickly set out to combine his two passions into a singular life’s pursuit. The way he figured, being the fastest ice-skater in his new homeland wasn’t just dependent on physical fitness, but quality of equipment—and as a certified bicycle repairman, he had an inside track on the latter. Soon, Nestor’s new take on all-in-one racing skates would make him a local cult hero on the ice, while also forming the basis for a highly profitable business . . . and an intense sibling rivalry.

[Eight competitors prepare for an ice skate race at the Humboldt Park lagoon in 1902. Nestor G. Johnson was a regular at these highly popular events, first as a speed skater, then as a skate designer, race organizer, and referee]

[Eight competitors prepare for an ice skate race at the Humboldt Park lagoon in 1902. Nestor G. Johnson was a regular at these highly popular events, first as a speed skater, then as a skate designer, race organizer, and referee]

History of Nestor Johnson, Part I: “King of the Blades”

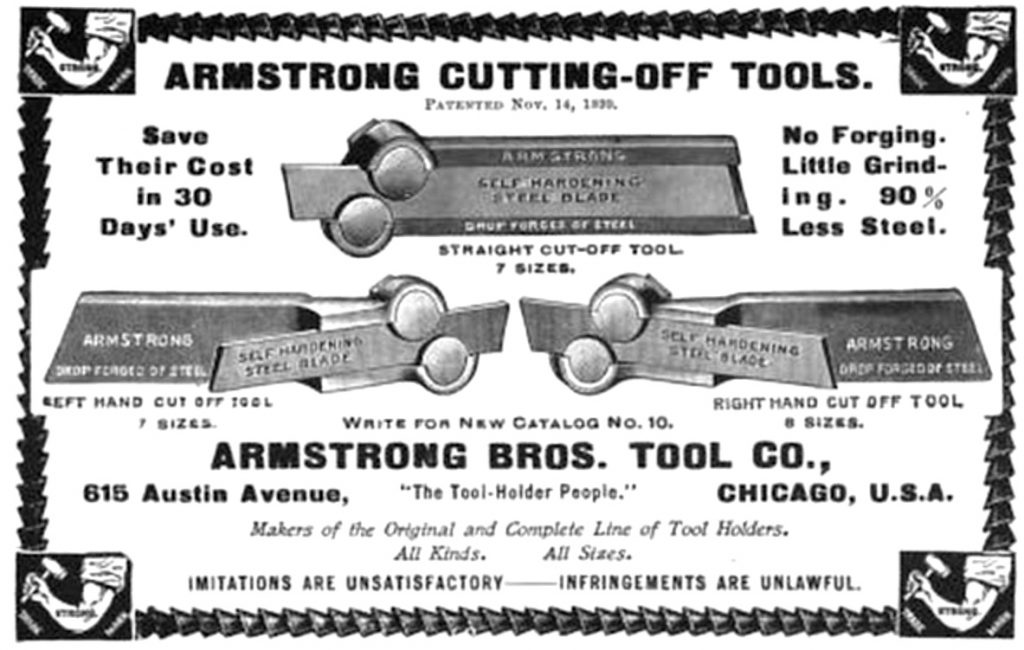

In the 1890s, Nestor Johansen and his new bride Annie—both now going by the Americanized surname “Johnson”—were part of a growing community of Norwegian immigrants settling around Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood. By day, Nestor was earning good money fixing bikes and selling parts, eventually landing him in the employ of the similarly inclined Armstrong Bros. Tool Company. Evenings and weekends, meanwhile, were devoted to the thrill of competition.

Along with his membership in several cycling and rowing clubs, Nestor emerged as one of the most recognizable faces in the city’s Norwegian-American Skating Club, regularly finishing among the leaders at well-attended winter skate races on the frozen ponds of Humboldt Park, Garfield Park, and Lincoln Park.

Along with his membership in several cycling and rowing clubs, Nestor emerged as one of the most recognizable faces in the city’s Norwegian-American Skating Club, regularly finishing among the leaders at well-attended winter skate races on the frozen ponds of Humboldt Park, Garfield Park, and Lincoln Park.

“A race was run Feb. 13 in the forenoon of Humboldt Park between George Syverson and Nestor Johnson, both members of the Norwegian Skating Club of Chicago,” the local Inter Ocean newspaper reported in its sports pages in 1891, noting that Johnson beat his rival across a whopping 15-mile distance with a time of 40:10 to 41:30. “This is, perhaps, the quickest time ever made in Chicago.”

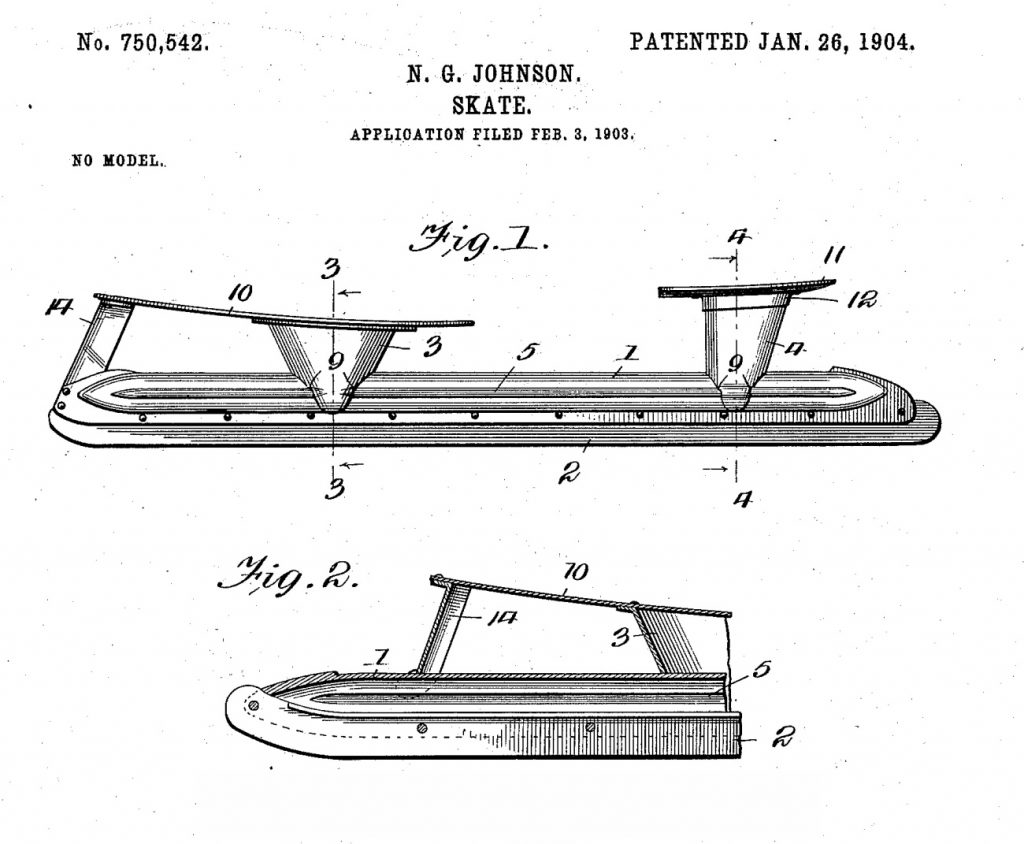

Like everyone else, Nestor caught the ambition bug after visiting the Columbian Exposition in 1893, and by the following winter, he had begun hand-making his own new style of reinforced racing ice skate, gradually showing it off to friends in the skate racing community. The “tubular” skate would be officially patented a decade later, with Nestor describing his intent “to form a hockey or racing skate having a hollow framework provided with a thin runner. Prominent objects of my invention are to improve the construction of such skates, to strengthen the same and thereby insure their more readily standing the severe strains put upon them, and to secure these results in a simple, practical, and inexpensive manner.”

The tubular design provided a game-changing framework for both the blade and the boot, but not everyone was on board immediately. Johnson’s new racing skates were so fast that they were actually briefly banned on Lincoln Park’s pond out of fear that reckless flying youths would become “a menace to the other people on the ice.” Nestor, recognizing that his budding business would fare much better free of such restrictions, pleaded his case, claiming his razor-sharp racers were “no more dangerous than an ordinary club skate.” Backed by a growing number of converts, he eventually got his way.

By 1903, Nestor Johnson was still a key mechanic and salesman for the Armstrong Brothers Tool Company, even representing the firm and its new line of “tool holders” on business trips to his native Scandinavia. Year by year, though, his “side hustle” as a skate-maker and race organizer was becoming more lucrative than his regular work. A lot of it was a matter of good timing.

By 1903, Nestor Johnson was still a key mechanic and salesman for the Armstrong Brothers Tool Company, even representing the firm and its new line of “tool holders” on business trips to his native Scandinavia. Year by year, though, his “side hustle” as a skate-maker and race organizer was becoming more lucrative than his regular work. A lot of it was a matter of good timing.

It’s hard to overstate just how popular ice skating had become in Chicago at the dawn of the new century. There were as many as 600 rinks in regular operation across the city, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, and when the State Championships of speed skating came to Humboldt Park on New Year’s Day of 1903, an incredible 50,000 people came to watch it.

Nestor Johnson was there himself, of course, but serving as a judge and timekeeper only. His younger brother Alfred—newly arrived from Norway—did compete in the races, but to little fanfare or success.

At 36, Nestor was getting a tad long in the tooth for racing, and he wasn’t entering as many events from 1900 onward. This makes it a bit amusing that, upon his death many years later, several papers published an obituary citing Nestor as “the Illinois ice skating champion from 1901 to 1908.” As best we can tell, this was total nonsense, and yet, it’s a stat that’s been referenced in subsequent skating histories for decades since.

II. California (Avenue) Bound

While Nestor Johnson’s fame as a speed skating champion may have been overblown, “Johnson’s Racing Skates” were most assuredly known to just about any serious skater and ice hockey player in America, with newspapers as far away as Montana promoting them regularly by 1906. Compared with old-fashioned clamp-on skates, the modern Johnson skates—with their fancy corrugated tubing, precision steel blade, one-piece plates and braces, and aluminum bronze finish—could cost you a heck of a lot more dough: maybe $10 to $15 instead of $1 or $2. But much like what happened with the basketball shoe market later in the 20th century, the cultural phenomenon (and peer pressure) around skate sports made the investment seem suited to the passion.

Johnson soon left Armstrong Brothers behind, and by 1908, he’d acquired a new, dedicated manufacturing space for himself at 638 N. California Avenue . . . soon to become 1237 N. California Avenue after the Chicago street name changes of 1909.

[The first Nestor Johnson skate factory at 1237 North California Avenue, circa 1920 and 2019]

[The first Nestor Johnson skate factory at 1237 North California Avenue, circa 1920 and 2019]

Pushing beyond the usual skating club circles, Nestor started making the rounds at conventions like the giant Shoe and Leather Market Fair at the Chicago Coliseum in 1909, where his sales pitch for his latest hockey and racing skates was repeated in the pages of the Boot & Shoe Recorder magazine.

Says Nestor Johnson: “These are the pioneer skates of their kind in America, and are skillfully manufactured under my own personal supervision. Having been a leading speed skater and participated with success in many races in Europe as well as in the United States, I fully understand the requirements of the skater. . . . Special attention is called to the fact that these skates are used for pleasure as well as speed. The entire skate is made in such a scientific and novel manner that it combines not only features of lightness but also those of strength; both very essential factors.”

For a while, Nestor’s small factory was still a catch-all for bicycle repair, skate making, and other hodgepodge jobs, but in 1912, the Nestor Johnson Manufacturing Company was finally, officially incorporated as a skate business, starting with just $10K in capital. Nestor, his wife Annie, and Julian T. Fitzgerald were the listed incorporators. Nestor’s aforementioned brother Alfred Johnson—eight years his junior—was hired as a machinist.

For a while, Nestor’s small factory was still a catch-all for bicycle repair, skate making, and other hodgepodge jobs, but in 1912, the Nestor Johnson Manufacturing Company was finally, officially incorporated as a skate business, starting with just $10K in capital. Nestor, his wife Annie, and Julian T. Fitzgerald were the listed incorporators. Nestor’s aforementioned brother Alfred Johnson—eight years his junior—was hired as a machinist.

It’s impossible to say what sort of relationship Nestor and his kid brother had before this point or during their years working together. But it’s safe to assume that some sort of serious tension soon brewed.

III. Brother vs. Brother

By 1917, the same year he turned 50, Nestor Johnson was a wealthy man and already set for retirement. The presumption, perhaps, was that he’d now hand the keys over to his brother Alfred. But things took a fairly dramatic left turn that spring.

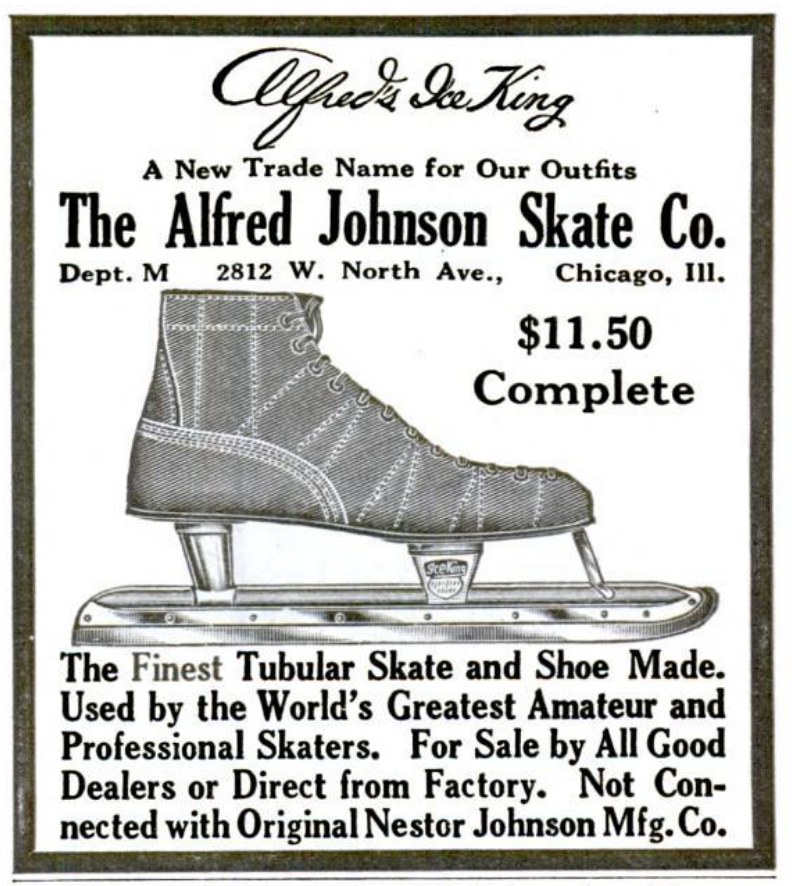

In an industry-rattling move, the ever-overlooked Alfred K. Johnson—joined by two other commanders of the Nestor Johnson MFG Co. (Julian Fitzgerald and Gustav E. Schmidt)—announced their immediate departure from the California Avenue plant and the organization of a brand new, separate business of their own. Alfred wasn’t planning to quietly branch out into some new industry, either. He was taking on his brother’s ice skate empire head on!

“One of the most important developments in ice skating circles during recent years is the formation of the Alfred Johnson Skate Company of Chicago,” announced the April 1917 issue of Billboard magazine, “which has been issued an Illinois charter to manufacture tubular ice skates. Alfred Johnson and G.E. Schmidt, who for many years were in the construction and mechanical departments of the Nestor Johnson Manufacturing Company, and Julian T Fitzgerald, secretary and sales manager of the same company, severed their connection with the Nestor Johnson Company to incorporate the new company. The capital stock is $20,000, and Alfred Johnson has been elected president. Work was started some time ago on a three story and basement brick and stone factory and sales rooms at 2812 W North Avenue, Chicago. The two senior members of the firm have had many years practical experience in the manufacture of tubular skates, having been in the business from its infancy, and with their continued service should be able to produce a most satisfactory skate.”

“One of the most important developments in ice skating circles during recent years is the formation of the Alfred Johnson Skate Company of Chicago,” announced the April 1917 issue of Billboard magazine, “which has been issued an Illinois charter to manufacture tubular ice skates. Alfred Johnson and G.E. Schmidt, who for many years were in the construction and mechanical departments of the Nestor Johnson Manufacturing Company, and Julian T Fitzgerald, secretary and sales manager of the same company, severed their connection with the Nestor Johnson Company to incorporate the new company. The capital stock is $20,000, and Alfred Johnson has been elected president. Work was started some time ago on a three story and basement brick and stone factory and sales rooms at 2812 W North Avenue, Chicago. The two senior members of the firm have had many years practical experience in the manufacture of tubular skates, having been in the business from its infancy, and with their continued service should be able to produce a most satisfactory skate.”

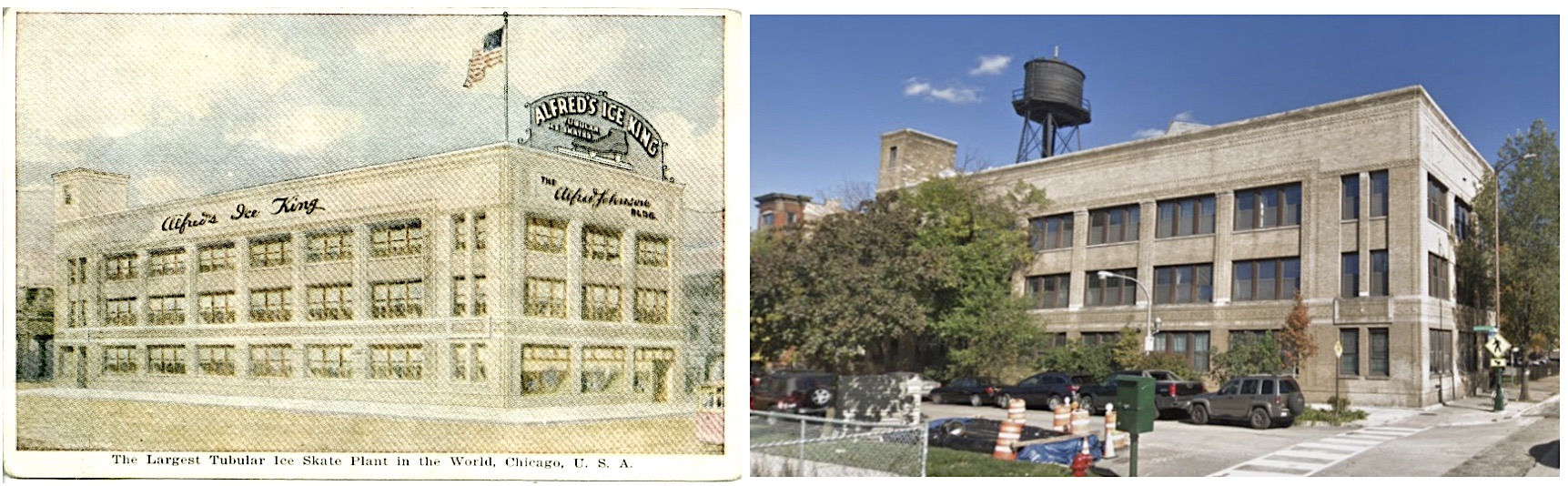

As you can see in the vintage advertisement above, Alfred wasn’t short on bravado either, dubbing his new brand of skate the “Ice King” and hailing it as the “Finest Tubular Skate and Shoe Made.” An all-out brother vs. brother civil war had commenced, fought with “blades” instead of rifles.

[The former Alfred Johnson “Ice King” skate factory at North Avenue and Francisco, 1920s vs 2019]

[The former Alfred Johnson “Ice King” skate factory at North Avenue and Francisco, 1920s vs 2019]

So what led Alfred Johnson to abandon his big bro and compete against him? Well, it could be that the retiring Nestor had told him he intended to put the business in the hands of a business protege, James W. Clark, rather than keeping it in the family. It’s also possible, I suppose, that Alfred actually broke away to keep making skates the way his brother always had; and that he didn’t trust Clark and new plant manager C.A. Ritter to do the same.

I can only speculate as to how all the politics really went down. What is clear is that the Nestor Johnson MFG Co. didn’t respond to Alfred’s new business venture as a form of friendly, sibling competition. In fact, with Clark now in control, the Nestor Johnson Company took the Alfred Johnson Skate Company all the way to the Illinois Supreme Court over the use of the name “Johnson” as a trademarked brand in the tubular skate business.

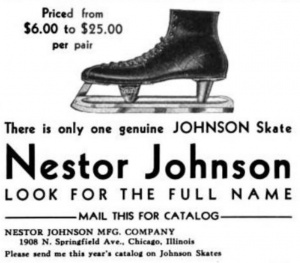

Eventually, a 1924 court ruling determined that Alfred could still use his own surname in the promotion of his skates, so long as he included the words “not connected with the Nestor Johnson Manufacturing Co.” in all advertising. Meanwhile, Nestor Johnson ads made a point of telling skate buyers that “there is only one genuine JOHNSON skate.” Christmases in the Johnson family must have been interesting.

Eventually, a 1924 court ruling determined that Alfred could still use his own surname in the promotion of his skates, so long as he included the words “not connected with the Nestor Johnson Manufacturing Co.” in all advertising. Meanwhile, Nestor Johnson ads made a point of telling skate buyers that “there is only one genuine JOHNSON skate.” Christmases in the Johnson family must have been interesting.

Around the same time as the court decision—with Nestor now happily retired to a dairy farm in Wisconsin—James Clark relocated the business from the California Avenue plant to a massive new headquarters at 1900 N. Springfield Avenue, on the edges of Logan Square and the Hermosa neighborhood. The company was now entering the modern skating era with enemies at the gate: not only Alfred, but F.W. Planert and big national distributors like Spalding. A booming roller rink fad also had a lot of kids giving up their blades for wheels. It was time to buckle down.

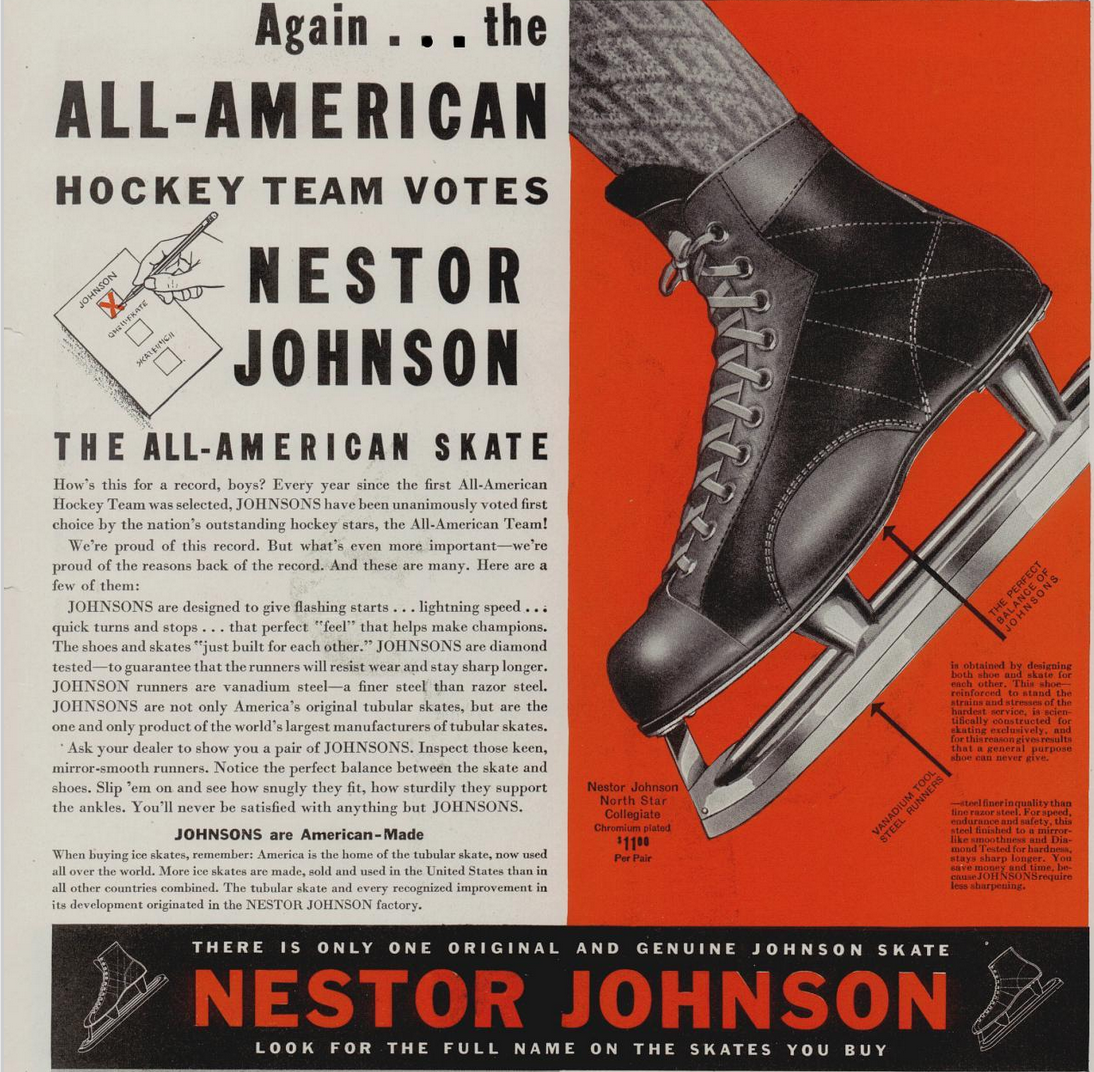

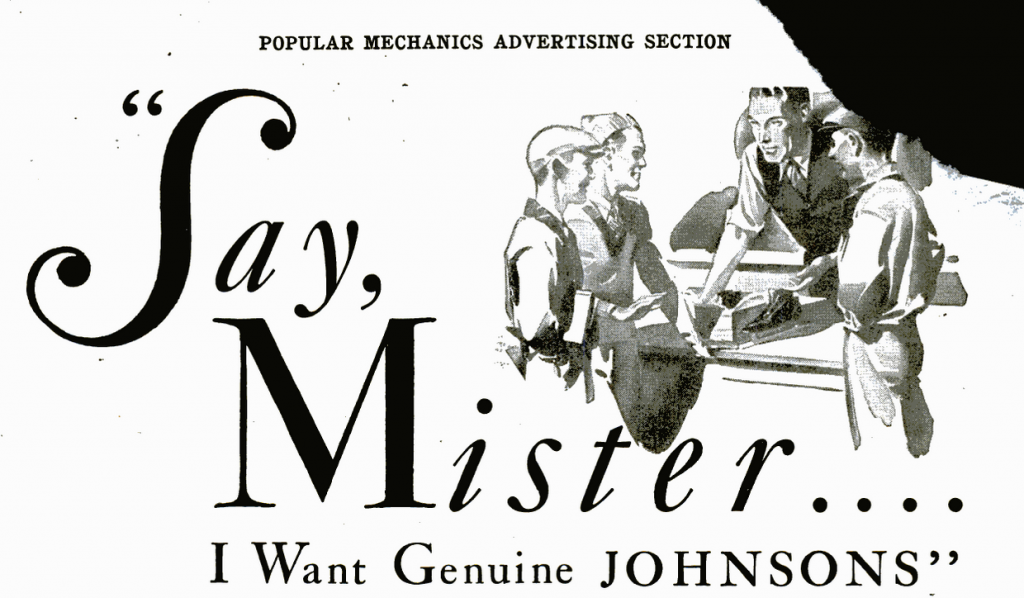

IV. Genuine Johnsons

When the stock market crashed in 1929, every skate maker had reason for concern. Now more than ever, the Nestor Johnson Co. needed to firmly separate itself from the pack. Towards that end, they started some amusing marketing campaigns built around their superior reputation, casting all other brands of skates as mere imitators. Genuine Johnsons were “Wings of Steel” that ran circles around those knockoff Ice Kings. And—more importantly—all the kids in the neighborhood KNEW IT TO BE SO. Or at least that was the premise.

Nestor ads often played out elaborate narratives, with smart-ass hockey kids telling shopkeepers why they wouldn’t even consider giving any other skate the time of day.

Of course, the slogan “I Want Genuine Johnsons” might not survive the pitch meeting these days, but it suited everybody just fine during the Depression.

From a 1931 ad in Popular Mechanics:

“I came here to get genuine JOHNSONS and I get them or you don’t get my money. And I’m speaking for the bunch, too.”

“You sure are,” chorused Tom and Dick. And ‘flashy’ Bill, the left wing of the school hockey team, said: “You couldn’t get me on any other skate.”

Amateur hockey was, indeed, growing rapidly in Chicago in the 1930s, and Nestor Johnson’s next president, Charles I. Johnson [not believed to be a relation], embraced the trend and his company’s potential role in it. “Hockey is new,” he wrote in a letter to skate dealers. “It packs a wallop, and it has a big future. With the right leadership . . . and promotion, the future is better than bright.”

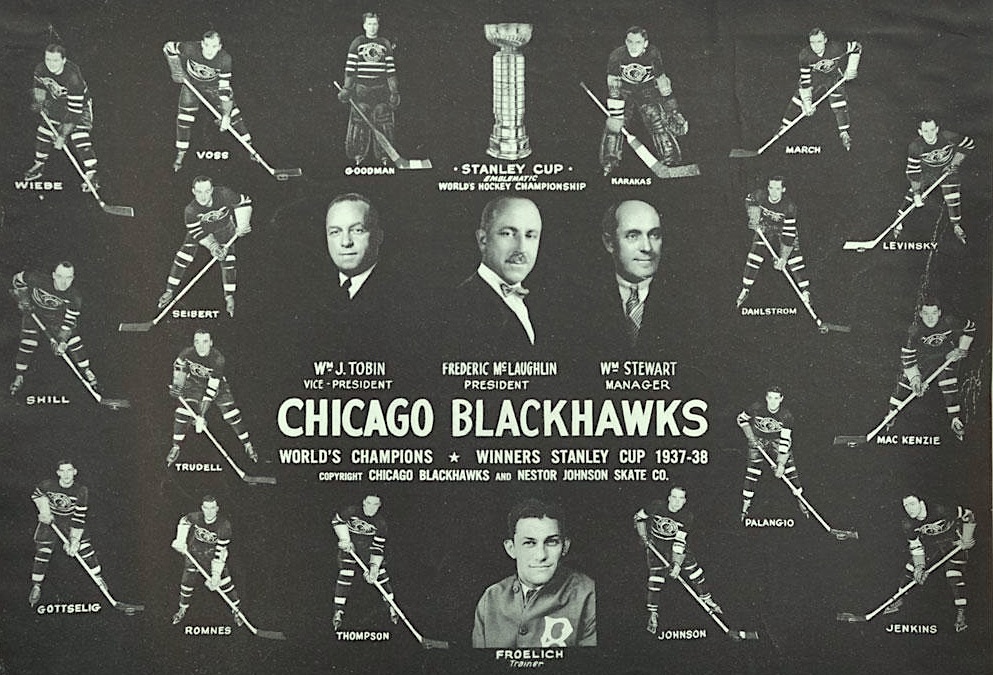

[Promotional Nestor Johnson poster celebrating the Chicago Blackhawks’ 1938 Stanley Cup title]

[Promotional Nestor Johnson poster celebrating the Chicago Blackhawks’ 1938 Stanley Cup title]

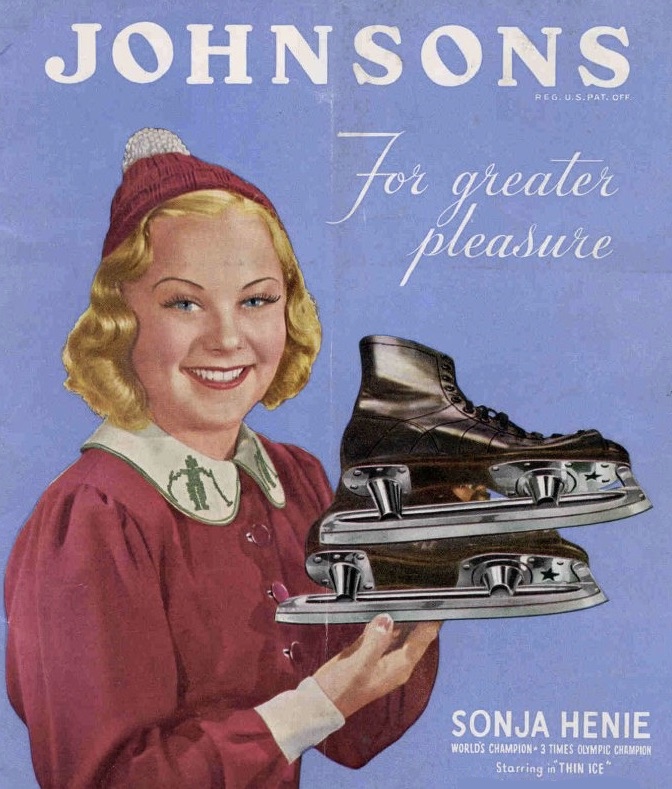

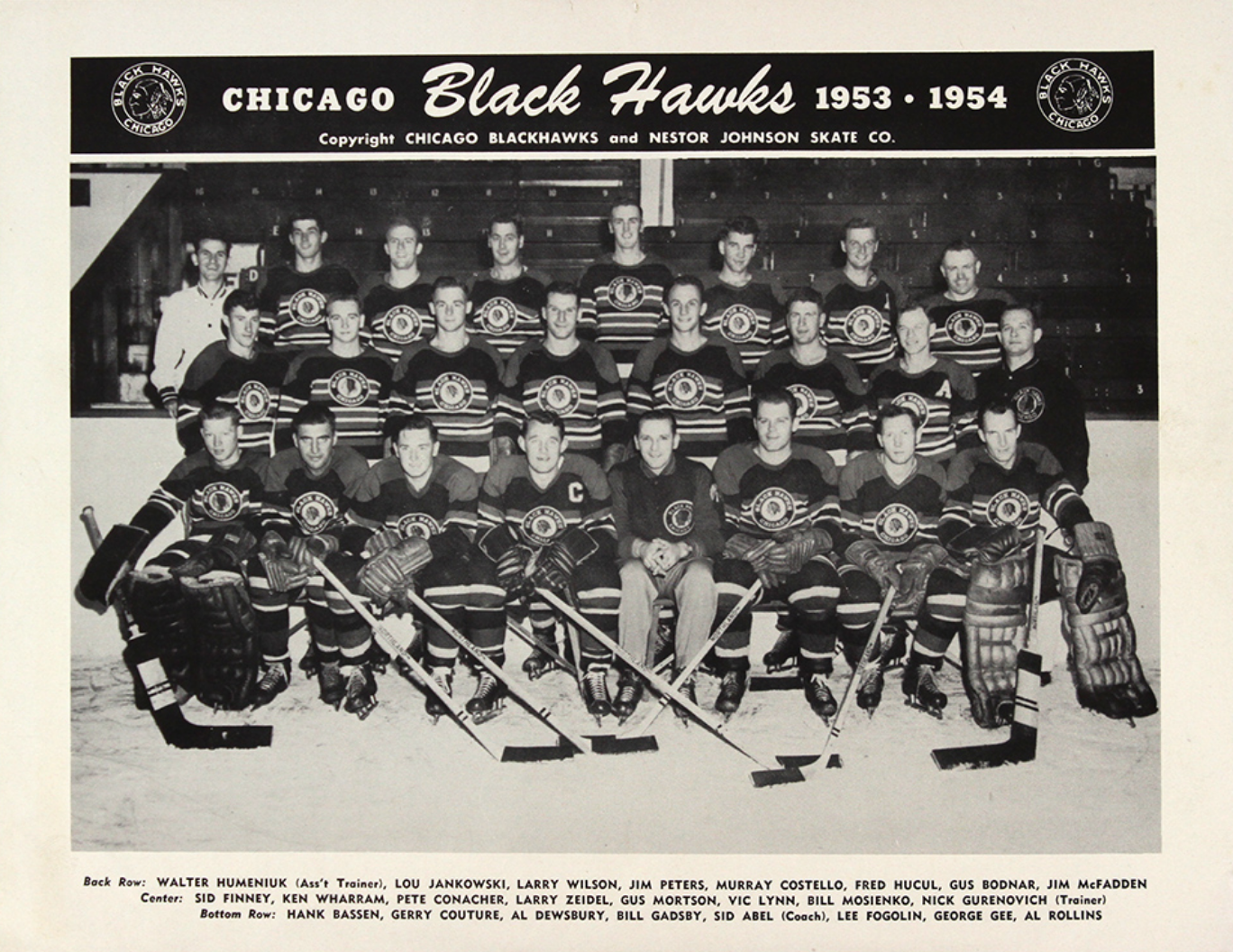

To further legitimize Johnsons skates with the hockey kids, Charles Johnson eventually managed to steal away the Chicago Blackhawks sponsorship from F. W. Planert, and with celebrity endorsements proving increasingly popular across the board, an even bigger splash was made in the women’s figure skating market, as Nestor Johnson became the official skate of Olympic superstar Sonja Henie.

Henie was a native of Norway herself, and while her rumored fondness for Adolf Hitler certainly sours her legacy more than a tad, her reputation among little girls was considerably more simple and sterling.

Henie was a native of Norway herself, and while her rumored fondness for Adolf Hitler certainly sours her legacy more than a tad, her reputation among little girls was considerably more simple and sterling.

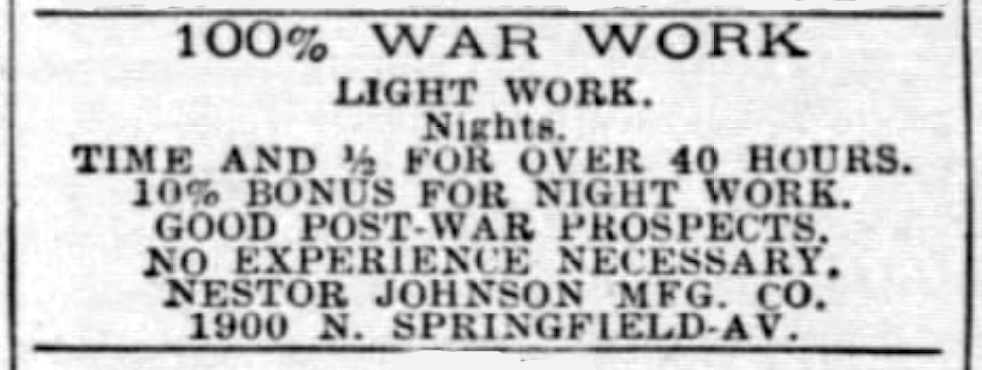

All these various marketing efforts were enough to help the Nestor Johnson MFG Co. hold off its challengers and survive the economic downturn. Once the U.S. entered World War II, however, it was all something of a moot point. While skates were still marketed from 1942-1945, it was almost entirely back-stock, as Nestor Johnson’s obligations shifted to using their steel and machining tools for government work.

All of Chicago’s skate-makers likely got a boost financially from building war supplies, but some were able to re-adjust to peacetime more easily than others.

[1943 “Help Wanted” ad seeking men for “100% War Work” at the Springfield Ave. plant]

V. The Human Touch

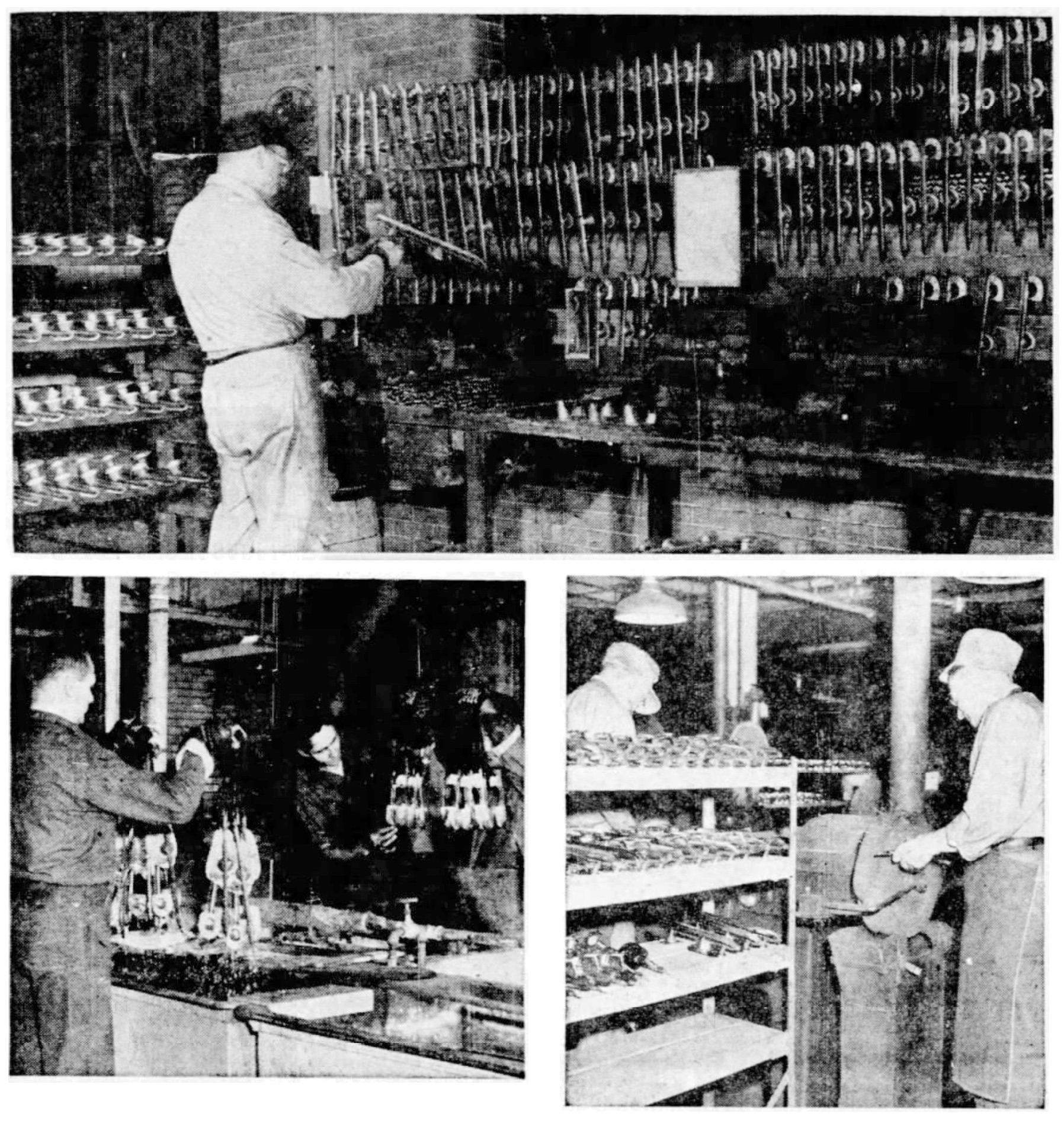

In 1949, the Chicago Tribune did a small profile on the city’s now 50 year-old tubular skate trade, mentioning Nestor Johnson, Alfred Johnson, and Planert as the regional leaders. Nestor’s Springfield Avenue plant had 100 workers on staff by this point, but they were still using crafty production methods much along the lines of what Nestor himself would have recognized decades earlier.

“Thru their assembly lines cold steel is machine cut and stamped into stanchions, sole and heel plates, and the other bits and pieces which will make up the finished skates,” Tribune scribe Jane Gardner wrote. “The blades that will sough thru the ice are the prima donnas of the manufacturers’ considerations, however. Metal for the blades is heated twice in ovens and cooled in liquid baths so the proper degree of toughness without brittleness may be achieved. Then, because the manufacturer has learned the stresses and strains of the descending weight of each footstroke, a third step is given that part of the blade attached to the shoe. In a seeming paradox, that upright part must be ‘softened.’

“Assembly line techniques give out after a fixed point in skate manufacture, however. The human eye and touch must take over to finish those blades.”

[Images from inside the Nestor Johnson factory, 1949, by Tribune photographer Robert Keigher. Top: Worker Frank Rietow fits the skate’s heel and sole cups to the tubular clamp for the blade. The skates are set up by size and genre: racers, figure skates, and hockey skates. Bottom Left: Plating room workers Leo Markowski, Matt Dassinger, and Joe Lenkowski dunk the skates to “clean, copper coat, nickel plate, and chrome plate the metal parts.” Bottom Right: Arthur Katz, a 40 year vet of the Nestor Johnson Co., was an expert in grinding the contour, or “rock,” of the blades.]

[Images from inside the Nestor Johnson factory, 1949, by Tribune photographer Robert Keigher. Top: Worker Frank Rietow fits the skate’s heel and sole cups to the tubular clamp for the blade. The skates are set up by size and genre: racers, figure skates, and hockey skates. Bottom Left: Plating room workers Leo Markowski, Matt Dassinger, and Joe Lenkowski dunk the skates to “clean, copper coat, nickel plate, and chrome plate the metal parts.” Bottom Right: Arthur Katz, a 40 year vet of the Nestor Johnson Co., was an expert in grinding the contour, or “rock,” of the blades.]

Readers likely found it appealing to see the artful, personal craftsmanship that still went into making their skates, but these images were actually portents of doom in a way.

Three months after that article was published, Nestor George Johnson died in Wisconsin at the age of 82, bringing a certain era to an end. A year after that, his brother’s once rebellious and thriving firm, the Alfred Johnson Skate Co., went bankrupt and closed its plant for good. The “Ice King” was dethroned, but the war for survival at the Nestor Johnson manufacturing plant carried on.

VI. The Thaw

Like many old-school companies dealing with the harsh realities of automation, the plastic revolution, and cheaper imported goods, the Nestor Johnson Company decided it was time to diversify in the 1950s. President Austin N. Clark, son of the late former prez James Clark, not only encouraged designers to work on other types of sporting goods, but on any other random marketable concept that might help the company increase its revenue.

The big winner of this campaign, surprisingly, was a small invention by company vice president Rudolph Notz, who applied for a patent in 1950 on what he called a “playing card shuffler device.” You can read all about it in more detail on our Nestor Johnson Card Shuffler page (we actually have two shufflers in the museum collection, just as we technically have two Johnson skates).

The big winner of this campaign, surprisingly, was a small invention by company vice president Rudolph Notz, who applied for a patent in 1950 on what he called a “playing card shuffler device.” You can read all about it in more detail on our Nestor Johnson Card Shuffler page (we actually have two shufflers in the museum collection, just as we technically have two Johnson skates).

The Shuffler and other novelty items did indeed help stem the tide for a while, and in the 1960s, other boosts came from logical progressions into hockey equipment like helmets, elbow pads, chest protectors, and mouth guards. Still, for a company so deeply tied to American ice skate history, losing a significant share of that market was basically like, I don’t know, skating on a thin sheet of ice? Is that metaphor apt?

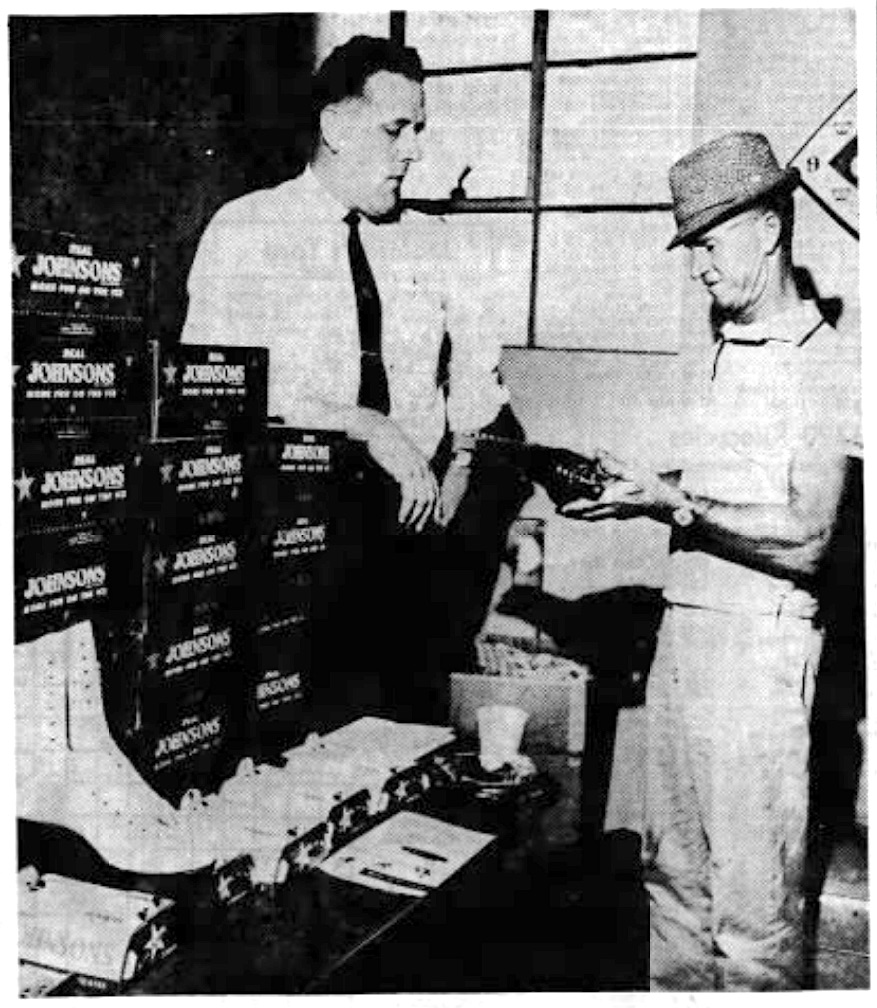

To reclaim their place in the consumer’s memory, Nestor Johnson representatives—led by sales manager Lew Oyen—continued to canvas the country in the ’60s, meeting with dealers and customers at conventions and shops in towns small and large, explaining calmly and enthusiastically why a quality, well-fitted skate still made a difference.

[Nestor Johnson sales manager Lewis Oyen, left, talks with a customer at a sporting goods store in Owensboro, Kentucky, in September of 1963. From the Messenger-Inquirer newspaper]

[Nestor Johnson sales manager Lewis Oyen, left, talks with a customer at a sporting goods store in Owensboro, Kentucky, in September of 1963. From the Messenger-Inquirer newspaper]

“My father ran the plant until roughly 1972,” Lew Oyen’s daughter Carol told the Made In Chicago Museum. “My aunt got him a job there a couple of years after coming home from the Service around 1950; she was a secretary.

“My father knew hockey players, Olympians, Ice Capades skaters . . . even fitted the chimpanzee for ice skates. He also judged speed racing at the Chicago parks. Everyone who knew Lew, loved Lew Oyen.”

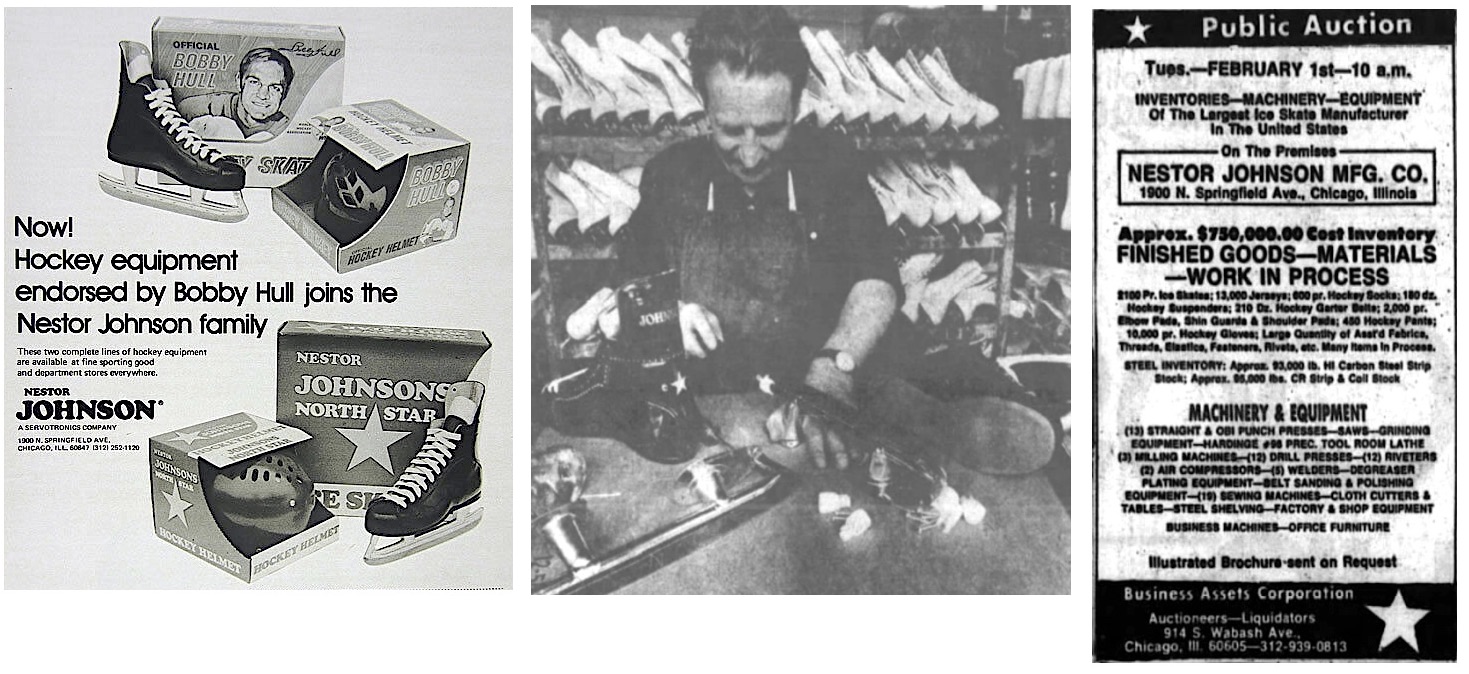

In the early 1970s, Nestor Johnson was purchased by Servotronics, Inc., out of Buffalo, New York. The new bosses kept the company in Chicago after the sale—still based out of the same aging Springfield Avenue plant they’d been in for 50 years—with a total staff now reduced to a little over 50 men and women. A turnaround in sales looked increasingly unlikely, but maybe not impossible. Servotronics even signed a deal with Blackhawks legend Bobby Hull to have his own official Nestor Johnson hockey skate.

In the early 1970s, Nestor Johnson was purchased by Servotronics, Inc., out of Buffalo, New York. The new bosses kept the company in Chicago after the sale—still based out of the same aging Springfield Avenue plant they’d been in for 50 years—with a total staff now reduced to a little over 50 men and women. A turnaround in sales looked increasingly unlikely, but maybe not impossible. Servotronics even signed a deal with Blackhawks legend Bobby Hull to have his own official Nestor Johnson hockey skate.

The problem was, Hull had just left Chicago after 15 years to play for the Winnipeg Jets. It was a metaphor of sorts; Nestor Johnson’s Chicago days were nearing an end, too.

[Left to Right: 1974 ad fro Bobby Hull’s official Johnson hockey skate; worker Julian Bildz attaching plastic caps to skate blades at the Johnson plant in 1975; an advertisement for the public auction at the now closed plant in 1977]

[Left to Right: 1974 ad fro Bobby Hull’s official Johnson hockey skate; worker Julian Bildz attaching plastic caps to skate blades at the Johnson plant in 1975; an advertisement for the public auction at the now closed plant in 1977]

On February 1, 1977, a public auction was held at 1900 North Springfield Avenue. The Nestor Johnson MFG Company’s long free-skate had come to its end, and roughly $750,000 worth of remaining skates, hockey gear, machinery, and equipment were let go at bargain prices.

The abandoned factory managed to find a few more occupants but fell into complete disrepair by the end of the century. It met the wrecking ball in 2005, replaced by new apartment buildings. The nearest dedicated ice rink is about 4 miles away.

[Race officials gathered in Humboldt Park in 1902. One of these men is almost definitely Nestor Johnson . . . we just don’t know which one. from Chicago History Museum]

[Race officials gathered in Humboldt Park in 1902. One of these men is almost definitely Nestor Johnson . . . we just don’t know which one. from Chicago History Museum]

Sources:

“Shoe and Leather Market-Fair: Skating Shoe Makes Friends” – Boot and Shoe Recorder, Sept 1, 1909

“A Race was Run . . . ” – The Inter Ocean, Feb 15, 1891

“Johnson Wins the Skating Race” – The Inter Ocean, Dec 26, 1897

“Pleads for Racing Skates” – The Inter Ocean, Jan 3, 1901

“Nestor Johnson Mfg. Co. v. Alfred Johnson Skate Co.” (1924)

“Expert Worker Puts Soul Into Shaping Skates” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 9, 1949

“Nestor Johnson Dies, Was Skate Inventor” – Marshfield News-Herald (Wisconsin), April 21, 1949

“Armstrong Bros. Tool Co. . . .” – Science and Industry, Vol. 7, 1902

“A Lot of Good Skates Made Johnson Roll” – Chicago Tribune, June 16, 1975

Playing for Change: The Continuing Struggle for Sport and Recreation, edited by Russell Field

Professional Skaters Association Newsletter Jan/Feb 2014

Archived Reader Comments:

“My family home where I grew up and where my mother (93) and sister still live (my father passed away in 1999) was built and owned by Nestor Johnson. ♡” —Mary, 2019

“I own a pair of skate blade protectors made of hard maple with leather straps the name Johnson and sons Seattle is branded into the side of the maple. Could this be related to the brothers?

How old would guess they are ?” —Diane, 2019

“I do remember blade protectors made of hard rubber. …and blade sharpeners I had the job of helping my mom address booklets to people who sent in .10 for them.

What a good life.

So simple.” —Carol Oyen Pappas, 2019

I am an avid hockey puck collector and own a “Gold Medal Johnson’s Official” hockey puck. I’m trying to find the history of this puck. I am aware of the Nestor Johnson hockey pucks used by the Central Hockey League and International Hockey League in the 1960’s. I don’t know if my puck is made by Nestor or one of the other Johnson companies.

Does anyone have information about Nestor pucks?

When did the Model 65 card shuffler start selling?

I am seeking a pair of the plastic end caps for the blade tubes. Mine finally wore off. Anyone have a stash of them somewhere?

For many many years my Dad would take me to the hardware store on 26th street in Chicago for new Johnson ice skates. I was in heaven, I also knew that it was sort of a hardship to spend the $15.00, but he wanted me to have them🥰. Thanks Dad for the great memory and generosity.

In 1955, when I was 12 years old, I went to the Nestor Johnson Company and got measured for a pair of racing skates. I still have them and they still fit (sort of).

The shoe plate says “For Nestor Johnson USA. Made in Norway”. There is a wing symbol in the center of the printing with what looks like the word “VING” below it. Also, there is no star cutout on the plate. Any idea how old these skates are? I know I bought them in 1955 but were they made earlier? Were the blades made in Norway before Chicago?

Hi I have a pair of white womens nestor ice skates with heel stamped made in Czechoslovakia in inside and foot. Are they worth more?

I have a Nestor Johnson tool for sharpening skates. Has a bolt clamp that fastens to a work bench. Skates are locked in (upside down) and one runs a stone on the flat surfaces to get an even sharpening of blade. I looks very old but it still works. All solid steel. Somebody really want it? I live in Eagan, MN. January 20, 2022

I have a pair of early 50’s Nester Johnson’s 17″ speed skates, men’s size 10. Looking to sell and wondering what the value.

I am here because of a Google search as I’m looking at an 8 x 10 black and white glossy photo produced by the Chicago Black Hawks when they won the Stanley Cup in 1960/61. It’s a beautiful photo without any commercial markings that includes all the players and executives including Arthur Wirtz, Thomas Ivan and James D Norris. And the Stanley Cup. The copyright is listed: Chicago Black Hawks and Nestor Johnson Skate Co.

Almost every Christmas during the late 50’s and early 60’s there was a brand new pair of Johnsons under the tree. Dad, Chris Katz, you see, worked for NJ for many years. One year he even presented me a set of official Blackhawk uniform patches. A few times, on Saturdays, when I was 7 or 8, dad brought me to work with him. Very happy I found this page loaded with history and memories. Thank you.

My grand father, John Burke used to take my brother’s & I to the Johnson plant every Summer to get fitted for new speed skates for the season. He knew most of the people at the plant.

Hi!

I just purchased a pair of Johnson’s Hard Toe Hockey Duro Model 743 skates new in the box. There is a touch of wear on the box but the skates are in almost perfect condition. Brown and black with yellow laces. I was hoping someone could tell me what year they are from? My guess is the 1950’s or 1960’s.

Thanks!

I have the same shuffler shown here, but instead of the plastic crank plate, mine is steel with a metal gear inside. Was this an earlier design, or later.?

My mother was a champion speed skater in the 40s. Luetta DuMez. She skated with CYO. I have her engraved Silver Skates that she won and a bin of used speed skates. Is there a museum that would like to display these items?

I found my mother‘s skates they are white boot. No heel. Identified with Nestor Johnson mfg, Chicago insignia. It also says lo-boys I can’t seem to find any information about them. All I see are black skates. Might you be able to provide any information about yhem

Hi, Angela,

Do your skates have speed skating blades?

My mother was a national champion speed skater in the 40’s and had a long association with the Nestor Johnson company. After having children, she coached a team. At the start of every season, she took us to Nestor Johnson for our new skates. One year, they had trouble fitting me with a speed skating boot, so they made me a pair of speed skates with a white figure skating boot (without the heel). I am thinking that you either have my skates or I am not the only person they made skates like that for. 🙂

BTW – When I was 4, I had the smallest pair of speed skates ever made by the Nestor Johnson Mfg. Co. They adapted a hockey blade to make my speed skates. Sure wish my mother had not lent those out years ago – would love to have them now.