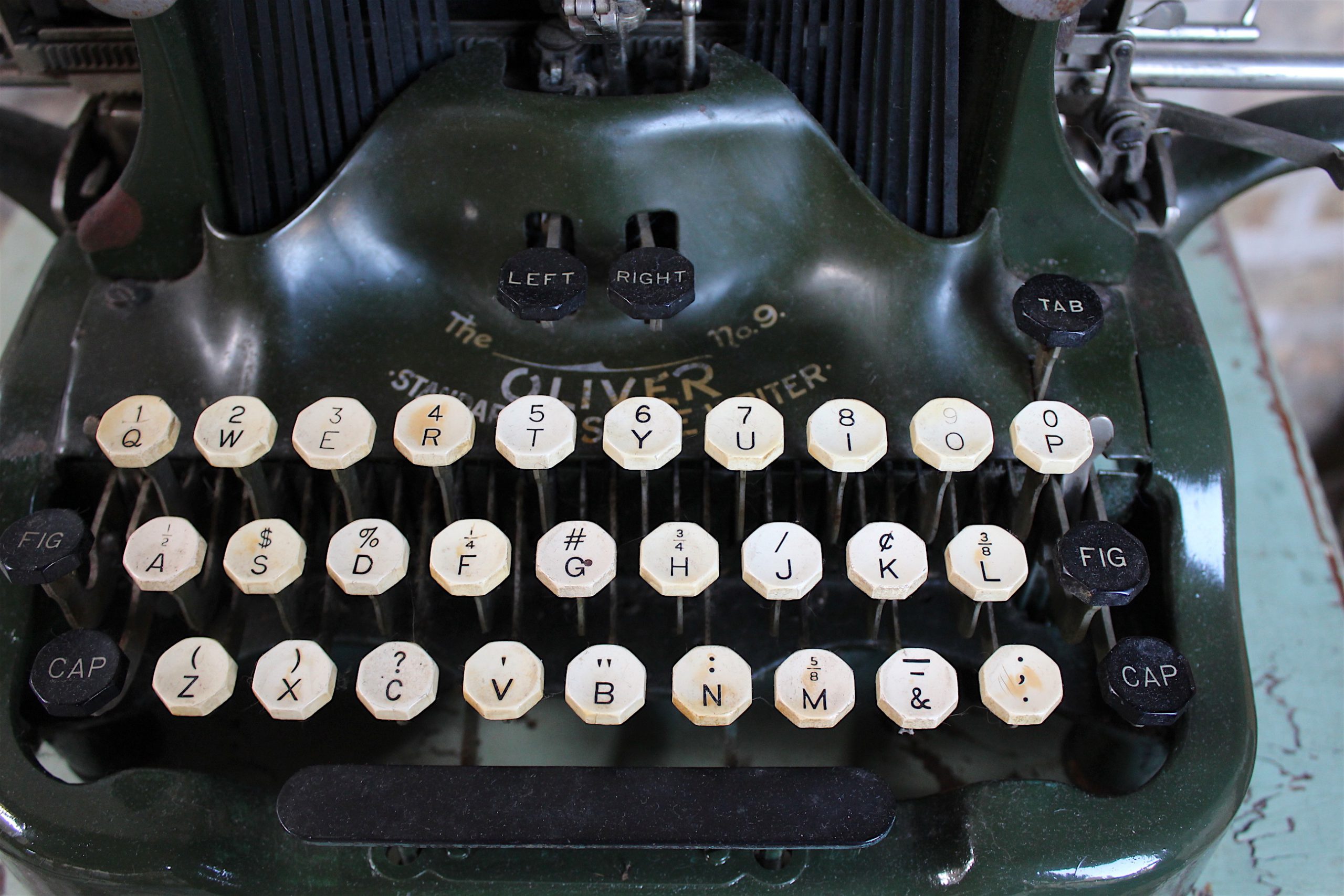

Museum Artifact: Oliver Typewriter No. 9, model year: 1917

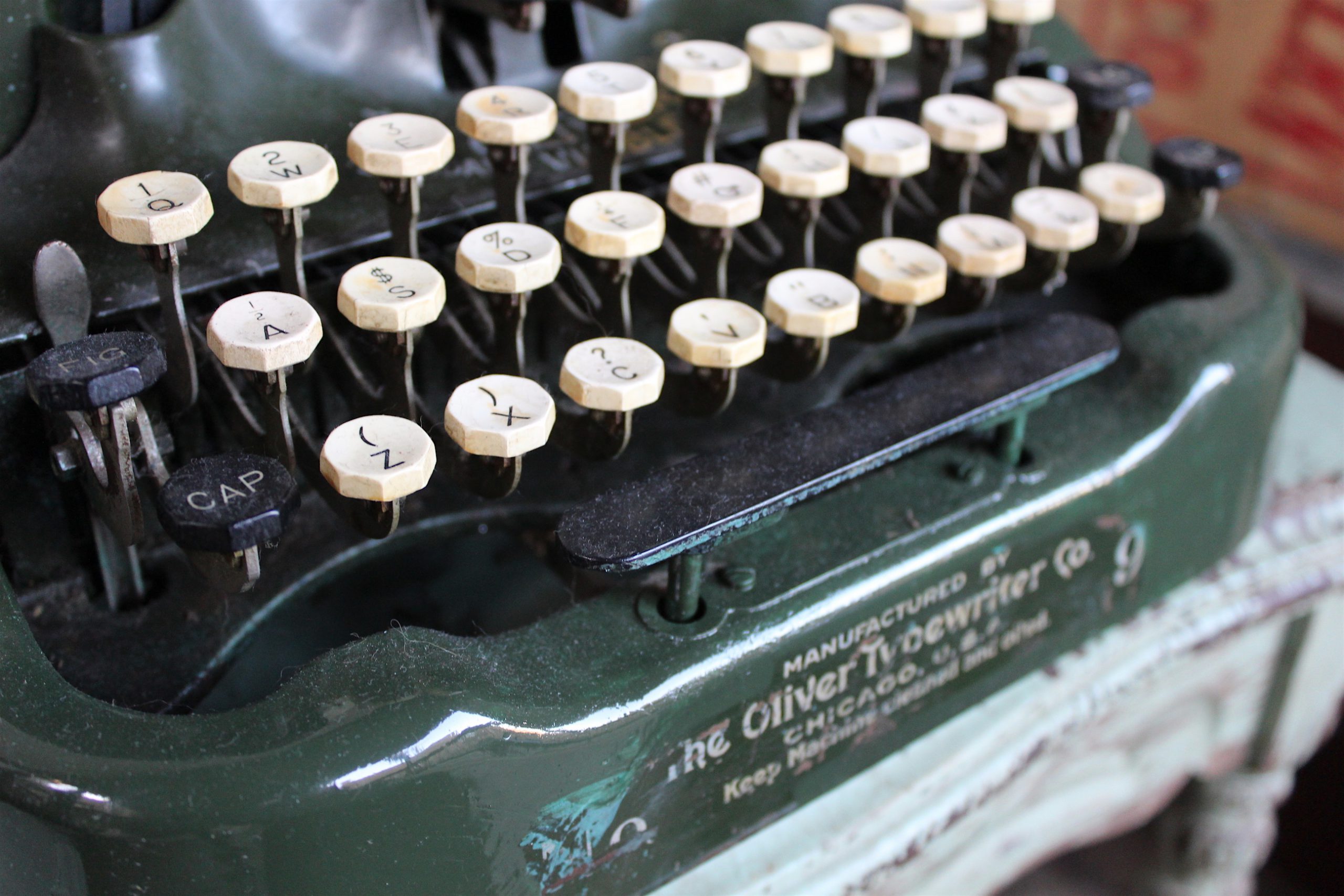

Made By: Oliver Typewriter Co., 159 N. Dearborn St., Chicago, IL / Factory: Woodstock, IL

“Simplicity, durability, speed, manifolding power, and visible writing are conceded to be the five great essentials in a typewriting machine. We present to the public THE OLIVER as the most striking embodiment of these features, and the most radical departure from other methods of construction.” —Oliver Typewriter Co. catalog No. 3, 1902

“Striking” and “radical” are certainly words that spring to mind just looking at this mean green typing machine—never mind the functional benefits. For my money, there’s no more aesthetically intriguing artifact in the Made In Chicago Museum.

“Striking” and “radical” are certainly words that spring to mind just looking at this mean green typing machine—never mind the functional benefits. For my money, there’s no more aesthetically intriguing artifact in the Made In Chicago Museum.

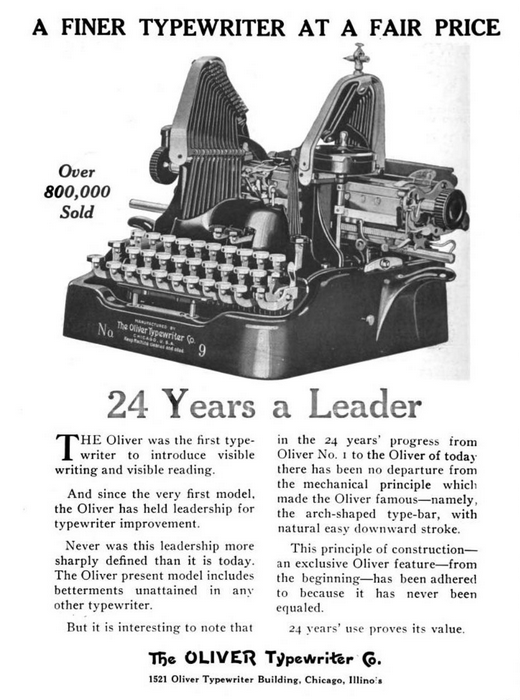

Across a 30-year run from 1896 to 1926, the original Oliver Typewriter Company (a later British version of the business carried on much longer) produced about a dozen different models of its unmistakable, bat-winged writing contraption; none in greater quantity than our museum artifact, the No. 9, which moved over 400,000 units after its 1915 introduction. By no coincidence, the small Chicago suburb of Woodstock, Illinois—home to both Oliver and the Woodstock Typewriter Co.—briefly became the unlikely typewriter capital of the world, shipping out 50% of the industry’s new machines each year.

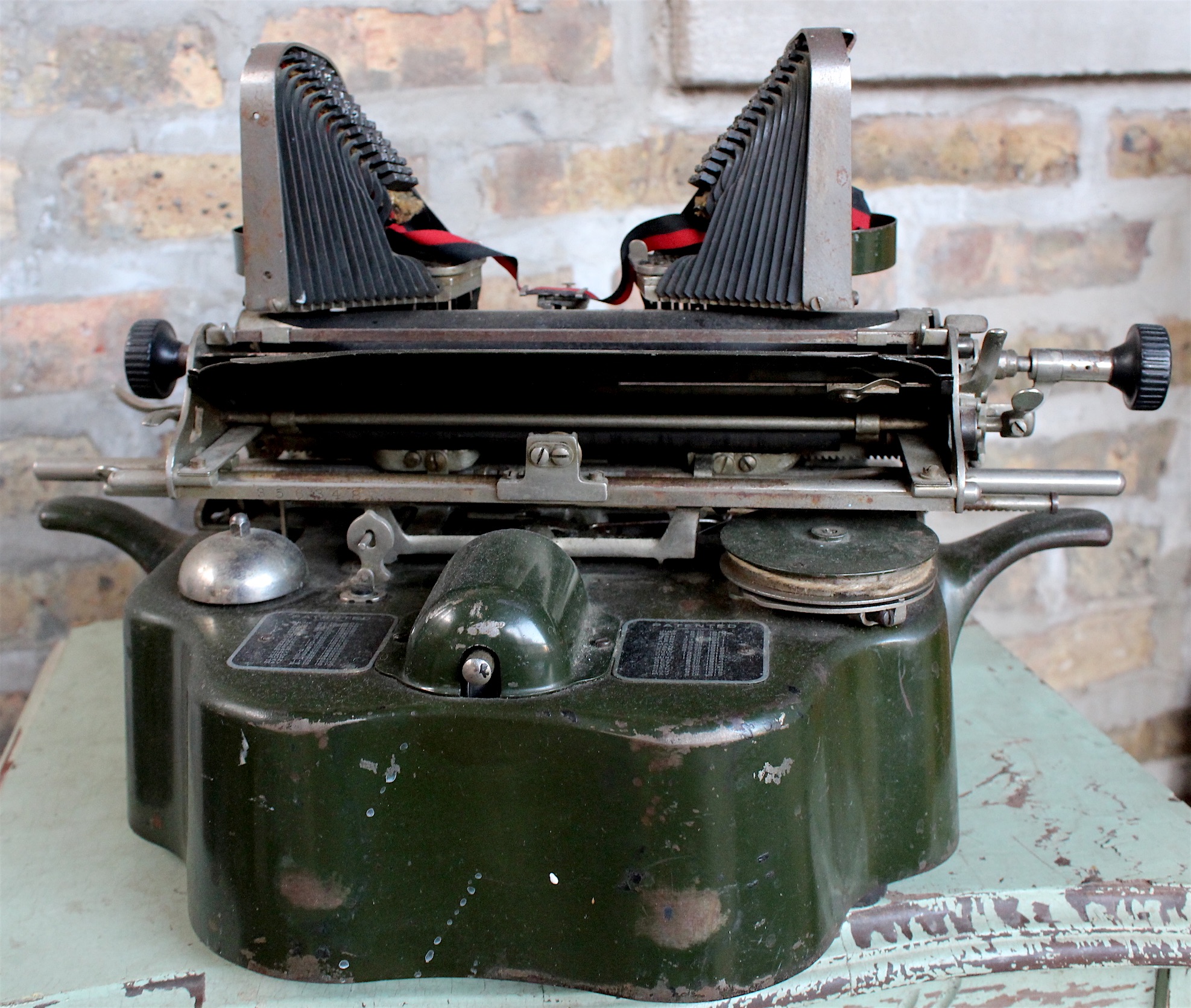

The Oliver No. 9, which remained in production through 1922, certainly had some helpful bells and whistles that its earlier predecessors lacked, but its makers never deviated too far from the original steampunk fever-dream first drawn up by company founder Thomas Oliver way back in 1894. As a result, no version of this typewriter bears any resemblance to the competing typing machines of its day—namely, the cookie-cutter, jet-black boxes churned out by the likes of Underwood, Royal, Remington, and that other Woodstock factory. Whereas those designs stuck to a standard of subtle sophistication, the Oliver was bold, aggressive, a tad flamboyant—more the pick-pocketing street urchin than the lonely orphan.

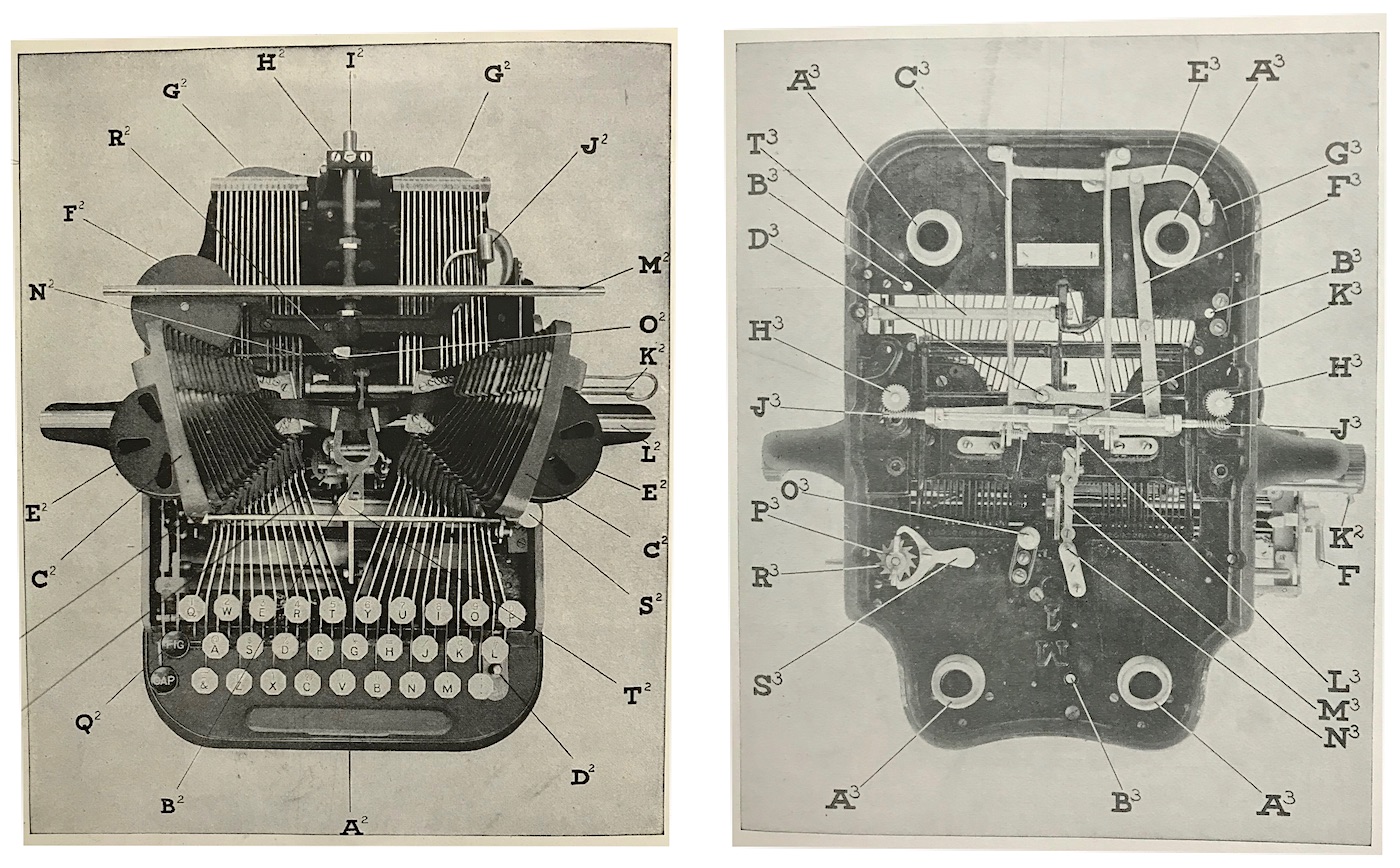

Most models were painted a deep olive green (for the sake of an olive/Oliver pun, presumably), and sported hexagonal keys, curved muscular plating, flared side handles (like little T-Rex arms), and that most significant of all features and innovations: the U-shaped, down-striking type-bars; aka, the bat wings. A beginning typist couldn’t be blamed for thinking the thing was about to leap off the desk at them, and at a weight of about 30 pounds, it could have done some damage, too!

History of the Oliver Typewriter Co., Part I: A Tale of Two Woodstocks

“While monuments are erected to the memory of statesmen, martyrs, warriors and heroes, the man who invents a utility—a practical common sense utility that lessens the labor of an individual or class of individuals—erects a monument to his own name, and Thomas Oliver is a man whose name will be on the roll of honor, a fit companion for the inventor of the telegraph, the telephone, the phonograph, the steam engine.”—Judge Charles H. Donnelly, from a eulogy delivered at the funeral of Thomas Oliver in Woodstock, Illinois, February 10, 1909

The story of the original Oliver Typewriter Company begins and ends in a place called Woodstock—only not the same Woodstock, and never the one of the famed hippie pilgrimage.

Thomas Oliver [pictured] was born in the small town of Woodstock, Ontario, in 1852, and while he’d wind up focusing his studies on becoming a Methodist minister, there was always the mind of a mechanical engineer brewing underneath (his mother once found that the family’s copper tea kettle, for example, had been smashed and contorted into a steam engine boiler by the precocious boy).

Thomas Oliver [pictured] was born in the small town of Woodstock, Ontario, in 1852, and while he’d wind up focusing his studies on becoming a Methodist minister, there was always the mind of a mechanical engineer brewing underneath (his mother once found that the family’s copper tea kettle, for example, had been smashed and contorted into a steam engine boiler by the precocious boy).

By the 1880s, Oliver’s religious pursuits had led him across the border and eventually to the town of DeWitt, Iowa, where he began his early career as a man of god. Not short into that assignment, however, his mind began to wander again. On a visit to the local town bank, he’d observed a stenographer tapping away furiously on one of the early typewriters of the era, and instantly deemed the machine an inefficient mess—”what good was a writing machine if you couldn’t even see what you were writing as you went along?” he thought to himself. And thus began a new calling for Thomas Oliver—a utilitarian’s siren song that seemed to light a greater fire under him than preaching the gospel ever had.

For several years, despite having no formal training or even a repairman’s understanding of existing typewriters, Oliver worked tirelessly to construct a functioning prototype of his own—a machine that would reveal each typewritten line on the paper as it appeared, without requiring the typist to lift up a lever and peek underneath. Famously, when nearly on the verge of giving up his efforts, the final component of his 500-piece puzzle came to him in a vision.

“It is the burden of some poet’s song that many of the world’s greatest inventions have come as the result of dreams,” the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune reported years later, “and this was the case in regard to Mr. Oliver’s invention.

“It is the burden of some poet’s song that many of the world’s greatest inventions have come as the result of dreams,” the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune reported years later, “and this was the case in regard to Mr. Oliver’s invention.

“He had been reading a work on machinery and thinking deeply about his pet project, when for the instant, tiring, he fell asleep in his chair. He had not slept long when like a flash the long sought design was pictured before him. Leaping from his chair like Archimedes is fabled to have done, and shouting that world old ‘Eureka’ to his surprised wife, he quickly sketched on paper the design he had caught in his dreams. To this day the essential feature of that design has remained unchanged. It was the U-shaped type bar.”

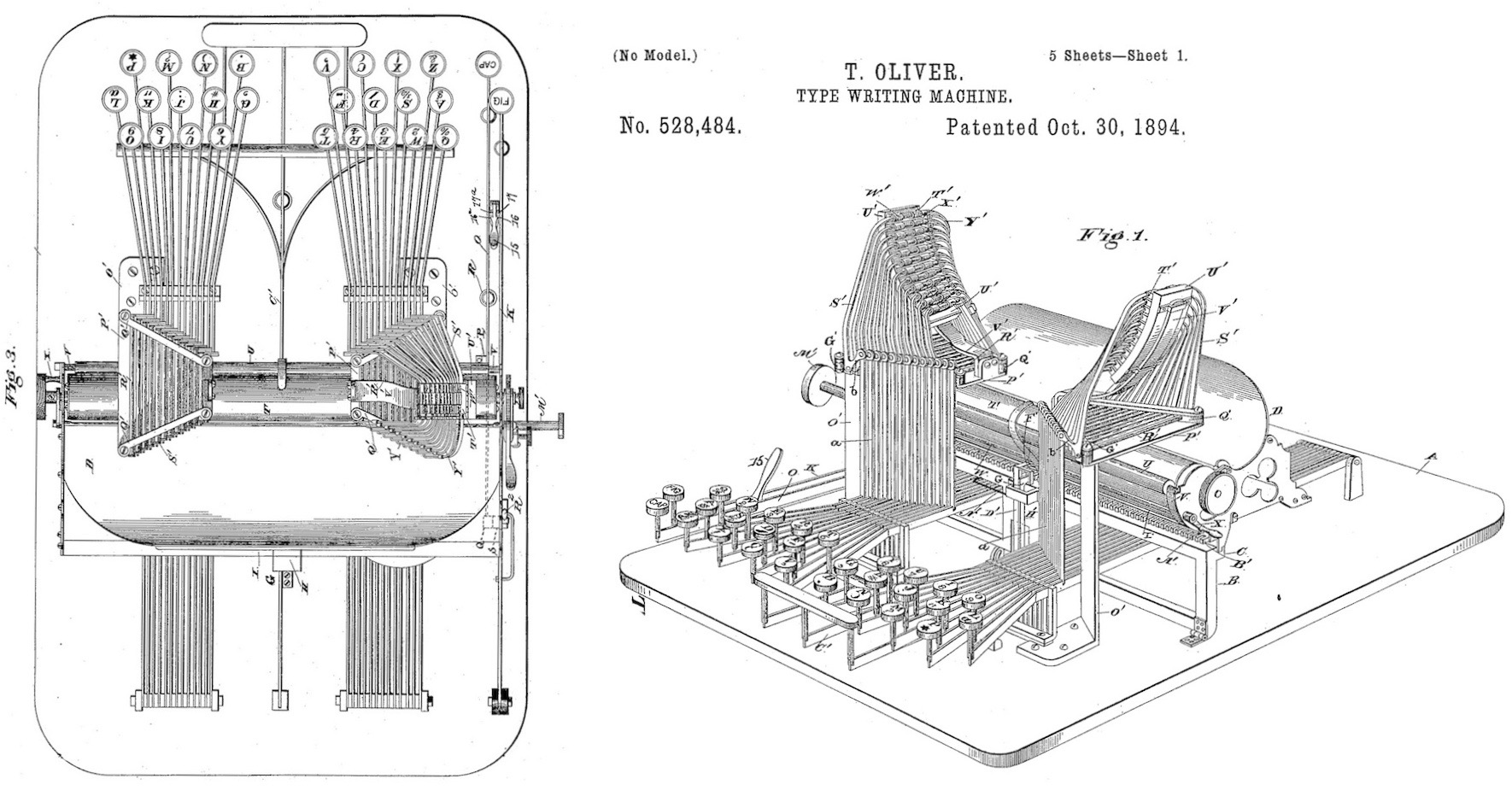

In 1891, at the age of 39, Thomas Oliver was awarded the first patent for his invention, and after scrambling together a few investors, he built up a small manufacturing operation outside of Dubuque in Epworth, Iowa. A second patent, approved in 1894, refined Oliver’s original design and introduced the familiar look that would define the brand for decades to come. Unfortunately for Thomas’s Iowa backers, though, they wouldn’t be reaping the spoils.

[Oliver’s 1894 patent revealed the set up of the U-shaped typebars in the manner that would define his machines for the next 30 years]

[Oliver’s 1894 patent revealed the set up of the U-shaped typebars in the manner that would define his machines for the next 30 years]

When on a sales trip in Chicago in 1895, Oliver got to discussing his business with a a group of interested big city investors, including future company presidents Granger Farwell, James Viles Jr., Lawrence Williams, and a wealthy newspaper publisher named Delavan Smith. A buyout soon followed, as the Chicago men purchased the shares from the frustrated Iowa fellows, while Oliver agreed to move his manufacturing operation east. The inventor retained 65% interest in his company (and creative control), and eventually opened the first Oliver Typewriter Company offices in Chicago at the corner of Clark and Randolph.

As for the new factory location, Oliver and his new cohorts searched a bit off the beaten path, and found themselves a deal when the tiny hamlet of Woodstock offered to donate the abandoned plant of the Wheeler and Tappan Pump Co., located about 60 miles northwest of Chicago, but still along a convenient rail route.

“Woodstock?” Thomas Oliver might have said when he heard the offer. “It’ll be like going home again.”

II. ‘Stock Players

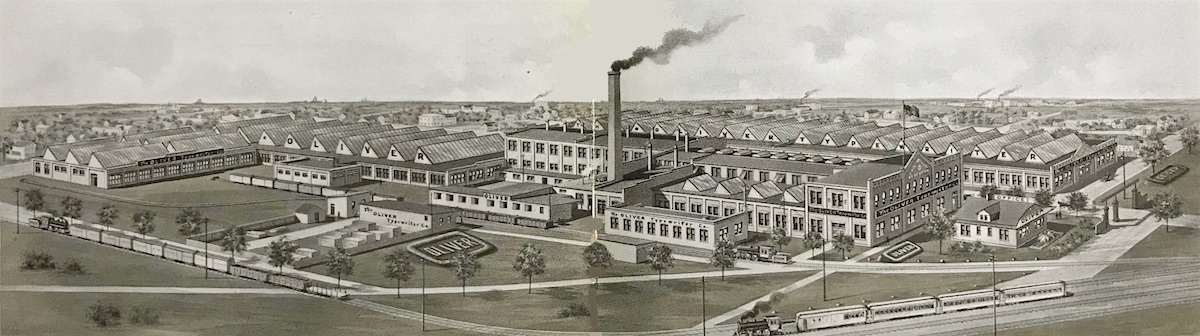

Oliver’s Woodstock factory opened in 1896, more than a decade before the Emerson Typewriter Co. (forerunner of the Woodstock Typewriter Co.) followed suit. As such, there was very little infrastructure in place to support a major industrial presence. The town’s entire population barely topped 1,500 in 1896, and within a year, more than a 100 of those residents were working at the Oliver plant. A year after that, it was 175. By the turn of the century, the team had grown to nearly 300, and the population of Woodstock had increased by 50 percent.

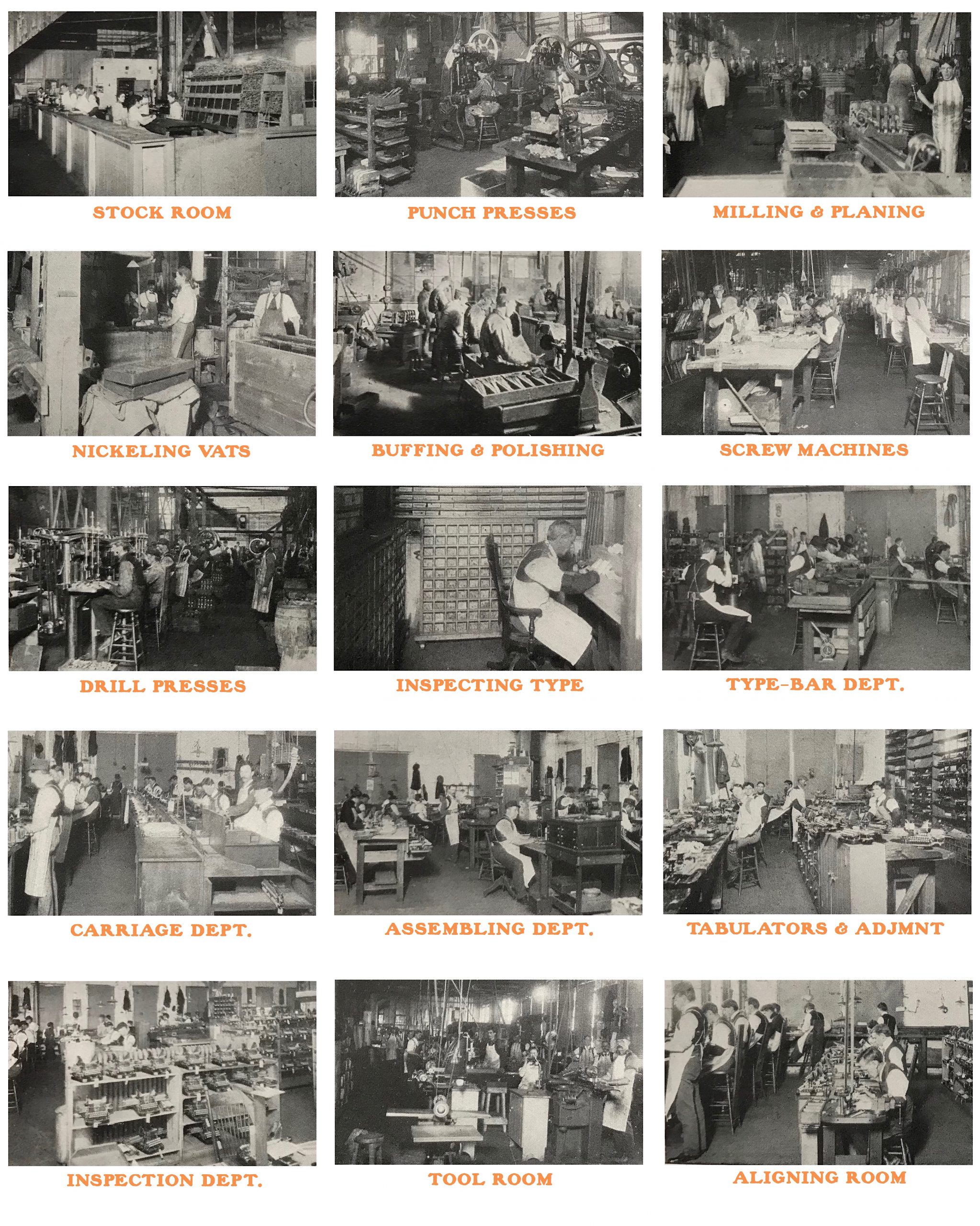

Among the new arrivals to the once sleepy town were the distinguished men tasked with turning a novelty product into a major manufacturing operation: guys like superintendent John Whitworth (former head of the Fowler Cycle Co. factory), assembly and repair department foremen George James Griffiths and Louis Johnson (both formerly of the National Sewing Machine Co.), mechanical department foreman Stephen Horr (who helped build the very first Olivers back in Iowa), enameling foreman Edwin E. Mead (a local Woodstock boy of “natural artistic talent”), tooling department head Lester A. Moreland (ex Stearns Bicycle Co.), and head inspector Harry Cross (“every machine comes under his critical eye and is passed as perfect on his judgment”).

Among the new arrivals to the once sleepy town were the distinguished men tasked with turning a novelty product into a major manufacturing operation: guys like superintendent John Whitworth (former head of the Fowler Cycle Co. factory), assembly and repair department foremen George James Griffiths and Louis Johnson (both formerly of the National Sewing Machine Co.), mechanical department foreman Stephen Horr (who helped build the very first Olivers back in Iowa), enameling foreman Edwin E. Mead (a local Woodstock boy of “natural artistic talent”), tooling department head Lester A. Moreland (ex Stearns Bicycle Co.), and head inspector Harry Cross (“every machine comes under his critical eye and is passed as perfect on his judgment”).

With Thomas Oliver and most of the company board members—including president Lawrence Williams and VP Delavan Smith—spending more time at the Chicago home office (by now relocated to 107 Lake Street), the evolution of the Oliver machine itself was increasingly left in the hands of those men on the Woodstock factory floor.

In the early years of the Woodstock Works, limited space led to cramped, over-heated conditions, as employees did painstaking machining and assembly work shoulder to shoulder. At the outset, they only completed about six typewriters per day, but by year five, the total had jumped to 40 per day, and by 1903, superintendent Whitworth told the Woodstock Sentinel newspaper that he expected the factory output to top 100 typewriters for every 10 working hours, with a three-fold increase beyond that once a new factory expansion was completed.

The Woodstock Works

The Woodstock Works

Departments of the Oliver Typewriter Co., circa 1903

“For some time past the enterprising people of this city have been observing the unusually rapid growth which the plant of the Oliver Typewriter Co. is enjoying,” the Sentinel reported in March of 1903. “Every day during the past few weeks new names have been added to the list of employees and that list has grown until on Monday last it reached 515.”

While the newspaper hailed the company’s success and described it as the “pride of Woodstock,” it also noted that the town itself still wasn’t equipped to handle the exploding population spurred by the Oliver factory, particularly when Whitworth was making it a point to hire only married men; seeing them as more likely to stick around. Married men, naturally, brought families, and families required homes—something in critically short supply in this portion of McHenry County. To compensate, the Sentinel implored its readers to take action and get to buildin’!

“That there isn’t an empty house in town, fit to live in, is a well known fact,” the paper acknowledged, “but worse than that there are many men who are now working here or want to come whose families must remain elsewhere. . . . The Oliver Typewriter Co. will furnish the employment for many people, but it is up to us to furnish the home. Build a house and do it now.”

“That there isn’t an empty house in town, fit to live in, is a well known fact,” the paper acknowledged, “but worse than that there are many men who are now working here or want to come whose families must remain elsewhere. . . . The Oliver Typewriter Co. will furnish the employment for many people, but it is up to us to furnish the home. Build a house and do it now.”

Woodstock might not have been created from scratch as a “company town” in the truest sense of the word, but its emergence in the early 20th century was almost entirely set in motion by the goings on at the Oliver plant. Accordingly, as the plant expanded, the company pulled out all the stops to keep its massive workforce (and thus, the townsfolk) happy, loyal, and off the picket line.

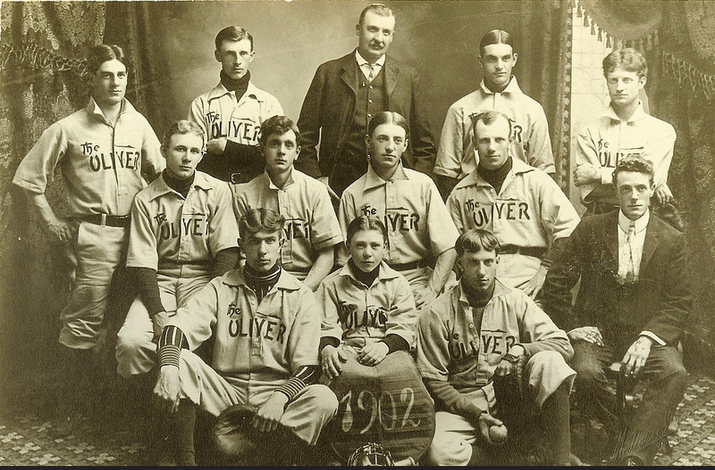

Within the factory’s first few years, a company concert band was formed, as well as a touring semi-pro baseball club. At worker assemblies, prideful company anthems were sung: “Oliver, My Oliver” (to the tune of “Maryland, My Maryland”) and “The Oliver is King” (to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne”). The name “Oliver,” for all intents and purpose, was more important to the community identity than the word Woodstock.

[After the Oliver Typewriter baseball club won its first game of the 1902 season, the Woodstock Sentinel reported that: “The Oliver team appeared in natty new uniforms of the colors so familiar to the users of Oliver typewriters, presenting a striking appearance, and their work with the stick did not belie that appearance, for they hit the ball good and plenty.”]

[After the Oliver Typewriter baseball club won its first game of the 1902 season, the Woodstock Sentinel reported that: “The Oliver team appeared in natty new uniforms of the colors so familiar to the users of Oliver typewriters, presenting a striking appearance, and their work with the stick did not belie that appearance, for they hit the ball good and plenty.”]

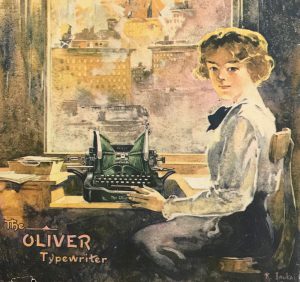

III. Selling the Shape

Meanwhile, back in Chicago, it was up to a team of roughly 30 salesmen to make sure every magical new Oliver dekstop found a worthy home—a task that was perhaps more challenging than they’d initially anticipated.

Meanwhile, back in Chicago, it was up to a team of roughly 30 salesmen to make sure every magical new Oliver dekstop found a worthy home—a task that was perhaps more challenging than they’d initially anticipated.

“The first Olivers were met with scorn and derision,” the company wrote reflectively in its own 1908 catalog, “not only by the Typewriter Trust, intrenched behind its capital of millions, but by the vast army of operators, to whom the words ‘visible writing’ conveyed no hint of the revolution they were destined to create.”

And so, Oliver’s army went door to door, business to business, showing the machine’s worth in practical, firsthand terms. Most customers were roped in by the convenience of the visible type alone, as salesmen were told to describe all past writing machines as foolishly “upside down,” while the Oliver finally turned things “right side up.”

[Above: Advertisement, c. 1905, seeking sales agents to promote Oliver Typewriters “at home”]

[Below: The Chicago based General Sales Team of the Oliver Typewriter Co., c. 1907]

The Oliver’s bat wings weren’t solely about creating sight lines, though. Salesmen had a boatload of other benefits to communicate about the design, touting its “simplicity, durability, speed, and manifolding power” along with the visible writing perks. These became the “five great essentials” of a typewriting machine . . . until “versatility” eventually made it “six great essentials.”

The key, of course, was the famous U-shaped typebar, with its “scientific level principle and wide, smooth bearings” (as noted in one advertisement). The bar not only ensured quality alignment and spacing, but also struck the paper with considerable force, making a “clear, clean-cut impression” that could serve as a “perfect stencil for mimeograph work.” And because the bars struck downward with gravity’s pull rather than up against it, the Oliver had “an action that is the lightest found on any typewriter. It is a pleasure to strike the keys.”

Soon enough, Oliver had clients as big as the Carnegie Company, American Steel & Wire, John Hancock, Montgomery Ward, Reid Murdoch & Co., and the U.S. Treasury Dept., as well as numerous overseas buyers and distributors.

“The cumbersome and complicated blind typewriters have become obsolete,” boasted an Oliver catalog. “The world has moved and is moving. Office equipment, and machinery generally, must keep pace with modern progress and inventive genius. The cry is for speed, efficiency, accuracy, durability; and The Little Giant, the all-conquering OLIVER, has proved itself the one machine that responds to these demands.”

IV. Landmark Status

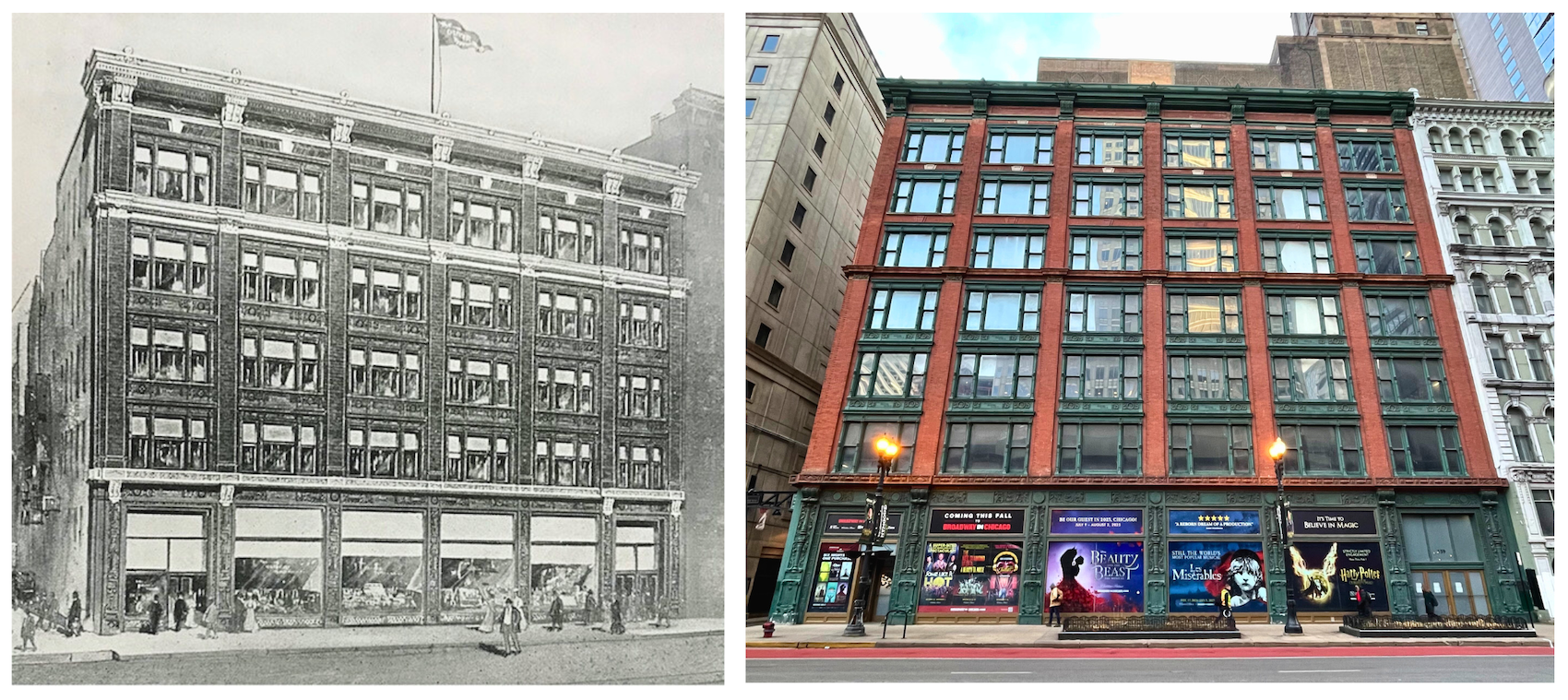

On April 28, 1907, the Oliver Typewriter Company took out a full page ad in the Chicago Tribune.

“Tomorrow morning,” the ad proclaimed, “the Oliver Typewriter will be ‘at home’ to its host of friends in the magnificent new Oliver Typewriter Building, 47-55 Dearborn Street [now known as 159 N. Dearborn St.], at Randolph. . . . The Oliver now has the honor of being the only typewriter in the world with its own exclusive office building.”

[The Oliver Building was five stories tall when it opened in 1907. It was then expanded to seven floors in 1920. It’s currently owned by the Goodman Theater. Photo on right by Andrew Clayman, 2024]

[The Oliver Building was five stories tall when it opened in 1907. It was then expanded to seven floors in 1920. It’s currently owned by the Goodman Theater. Photo on right by Andrew Clayman, 2024]

It was no humble structure, either. The red brick high-rise, designed by Holabird and Roche, is now a historic landmark, and looks every bit as impressive as it did in its own day, complete with the original cast iron, Oliver-trademarked ornamentation. It was truly a “model office building, combining with unusual architectural beauty every known facility for administering the affairs of the big corporation with ease, accuracy and dispatch.

“In convenience of arrangement, perfection of equipment, handsome appearance and substantial construction, the Oliver Typewriter Building is unsurpassed.”

While its manufacturing was centered in Woodstock, there was never any questioning Oliver as a Chicago business. Every typewriter had the word “Chicago” stamped on its base; the spectacular new mega home office was downtown; and Thomas Oliver—the man himself—lived with his wife in the Edgewater neighborhood at what’s now 5063 N. Winthrop Avenue.

Logically, the opening of the Oliver Building in 1907, combined with the successful debut of the Oliver No. 5 that same year, could have felt like a crowning achievement for good ole Tom Oliver. At 55, he should have been thinking about a happy retirement while basking in the rarified air of the legendary inventors club. That, however, was not how our hero rolled.

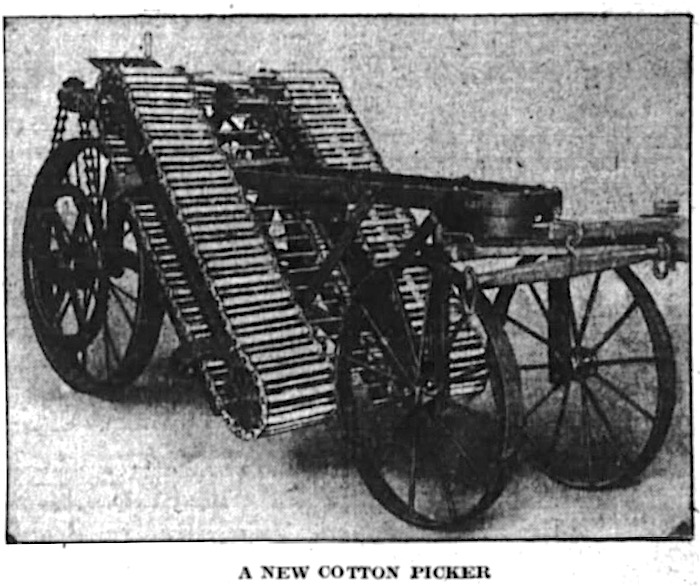

Instead, Oliver had found a new challenge to occupy his obsessions. Having conquered the office setting, he shifted to the agricultural market—specifically, the cotton picking machine. Yes, the device once revolutionized by Eli Whitney was overdue for an overhaul, and Thomas Oliver felt he was overdue for a second moment in the spotlight. Toiling for years on the project, he launched a new business in Chicago, the Oliver Cotton Harvester Company, and by 1909, finally completed a prototype machine to share with the world.

Instead, Oliver had found a new challenge to occupy his obsessions. Having conquered the office setting, he shifted to the agricultural market—specifically, the cotton picking machine. Yes, the device once revolutionized by Eli Whitney was overdue for an overhaul, and Thomas Oliver felt he was overdue for a second moment in the spotlight. Toiling for years on the project, he launched a new business in Chicago, the Oliver Cotton Harvester Company, and by 1909, finally completed a prototype machine to share with the world.

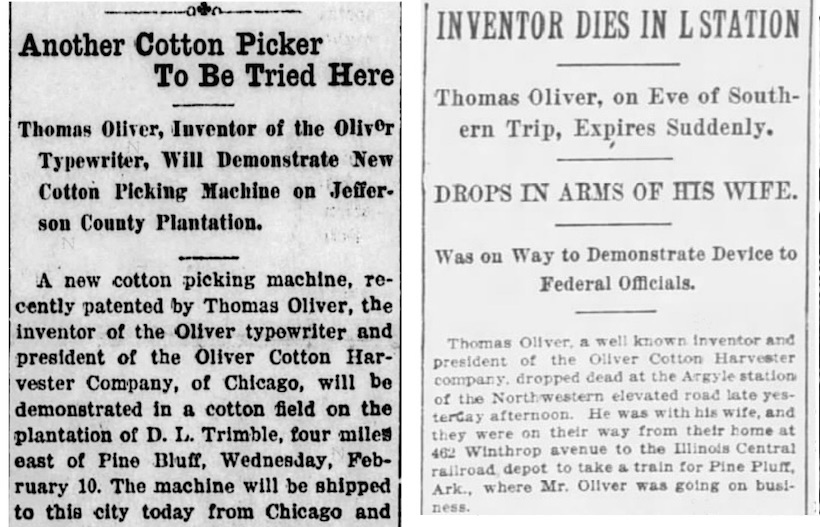

On February 6th of that year, the Daily Graphic newspaper in Pine Bluff, Arkansas reported that the new Oliver cotton picking device would be demonstrated on February 10th on the nearby plantation of a Mr. D. L. Trimble. “The machine will be shipped to this city today from Chicago and will be set up immediately after its arrival Monday. Thomas Oliver, the inventor, will come here to personally make the demonstration.”

But he never did.

On the afternoon of February 9th, Oliver and his wife took a chilly winter walk from their home to the nearby Argyle train station, ready to begin the long journey south for Thomas’s highly anticipated presentation. They were sitting on a bench at the station, luggage at their side, when Oliver suddenly collapsed. Within minutes, he was dead from heart failure.

His new invention had “occupied his mind to the exclusion of his health,” The Inter Ocean reported the next day.

[Left: Article from February 6, 1909, previewing Thomas Oliver’s upcoming appearance with his new cotton picking machine in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Right: Chicago Tribune story 4 days later, noting Oliver’s sudden death at Chicago’s Argyle station, at the beginning of his journey to Pine Bluff]

[Left: Article from February 6, 1909, previewing Thomas Oliver’s upcoming appearance with his new cotton picking machine in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Right: Chicago Tribune story 4 days later, noting Oliver’s sudden death at Chicago’s Argyle station, at the beginning of his journey to Pine Bluff]

V. Oliver, Post Oliver

Tragic story though it may have been, the death of the Oliver typewriter’s namesake did not slow the company’s roll as the 1910s unfolded. The operation continued to grow, only pushed further perhaps by the arrival of the Woodstock Typewriter Company and the friendly rivalry that ensued. As usual, Oliver’s catalogs laid all alternatives to waste in no uncertain terms, shamelessly listing off its singular achievements.

“Such revolutionary advances as visible writing, rigid typebars, writing in colors, automatic division of the keyboard, touch writing, Printype [a unique typeface design to look more like traditional book fonts], line-ruling devices, paper-holder, and many improvements of importance, owe their birth, their growth and their adoption by the public to the steadfast adherence of the Oliver Typewriter Company to proper principles of typewriter construction.”

“Such revolutionary advances as visible writing, rigid typebars, writing in colors, automatic division of the keyboard, touch writing, Printype [a unique typeface design to look more like traditional book fonts], line-ruling devices, paper-holder, and many improvements of importance, owe their birth, their growth and their adoption by the public to the steadfast adherence of the Oliver Typewriter Company to proper principles of typewriter construction.”

As noted earlier, the production of the Oliver No. 9 from 1915 to 1922 was something of a high-water mark for the business, as the Woodstock factory reached its peak output of about 325 machines per day. There were 1,400 parts in each typewriter by now, and 1,400 workers in Woodstock to make sure each one was in there. Better still, there were many thousands of customers, at home and abroad, willing to spend 100 hard-earned bucks(about $1,400 after inflation) to grab their own mean green machine.

There were some unwelcome warning signs on the road ahead, however.

First came the breakout of World War I, followed by America’s reluctant entry into the conflict. The Oliver factory, like many similar plants of the time, had to shift much of its focus into munitions and other government work during those years. Fortunately, the military needed typewriters, too, so the core business wasn’t entirely abandoned. Even so, by the time war ended in 1918, long tenured personnel like superintendent John Whitworth seemed to sense the business falling behind for the first time.

[During World War I, many women entered the Oliver workforce, helping to build not only typewriters, but munitions for the war effort]

[During World War I, many women entered the Oliver workforce, helping to build not only typewriters, but munitions for the war effort]

As unique as the Oliver No. 9 design was, for example, it was no longer miles ahead its competition in functionality, regardless of what the catalogs said. One particular disadvantage, in fact, was that the Oliver still had three rows of keys instead of the four rows that had now become the industry standard. To add a fourth row at this stage would have meant having to install even taller bat-wings and an even heavier frame. It was one of several mounting stumbling blocks that seemed to pile up right in time for a brief economic recession in the early 1920s.

In a dramatic response to this slowdown, the company slashed prices on the No. 9 after the war, advertising the machine as a mail order purchase in national magazines, with installment payment plans as low as $4 per month.

“A new Oliver No. 9, our latest and finest model, now only $64,” a 1921 ad read. “The identical typewriter that sold for $100 before the war. We now sell direct from the factory to you. A sensible method, an economical method. We inaugurated this plan during the war, when economy was urged upon all of us as a patriotic duty. And we were glad to break away from the old system of selling typewriters. It was too complicated, too costly, too wasteful.”

“A new Oliver No. 9, our latest and finest model, now only $64,” a 1921 ad read. “The identical typewriter that sold for $100 before the war. We now sell direct from the factory to you. A sensible method, an economical method. We inaugurated this plan during the war, when economy was urged upon all of us as a patriotic duty. And we were glad to break away from the old system of selling typewriters. It was too complicated, too costly, too wasteful.”

The company’s new, supposedly more efficient approach to selling its machines involved closing down dozens of branch offices around the world and letting go almost the entire team of traveling salesmen. It was a huge gamble, and it didn’t pay off. While sales spiked for a while in the mail order market, things turned south again when hundreds of customers started defaulting on their installment payments. This proved a complexity far more taxing than any of the old ones, and Oliver found itself struggling to afford the expenses of repossessing its own property.

By 1926, three years before the stock market crash would have doomed them anyway, the Oliver bubble officially burst. The once churning and billowing factory went silent, and the company’s final president, millionaire Edward Herndon Smith, at age 68, was more than happy to start his retirement. Much of the subsequent dirty work, then, fell to none other than poor old John Whitworth, the respected superintendent who’d stuck with the Oliver company for three decades, helping it build a town and conquer the world, only to wind up auctioning off every piece of machinery he had acquired.

In the summer of 1927, in a bit of a surprising twist, the vast majority of that property, and the Oliver Typewriter Co. itself, were purchased by a 67 year-old, UK-based businessman named George Mower for the price of £45,000. And from this, the British Oliver Typewriter Company (based in Croydon) was born, eventually finding some short-term success of its own as a leading machine of the Second World War and as a popular portable in the 1950s. By then, however, the bat wings had long since been shed.

The old Woodstock Works, meanwhile, was scooped up by the Alemite Die Casting Company, which passed it to a few additional owners before the entire ancient complex met the wrecking ball in 1997.

The Chicago era of the Oliver, while brief by some industrial standards, looks a bit more impressive when you look at it as a tech company; producing a 30 LB alternative operating platform for 30 years, and somehow maintaining at least a partial grip on the cutting edge. For the people who built over a million finely-tuned Oliver machines in Woodstock, these machines also represented a livelihood, a tight knit community, and a sense of pride. A century later, the first “visible writer” is still certainly a sight to behold.

The Chicago era of the Oliver, while brief by some industrial standards, looks a bit more impressive when you look at it as a tech company; producing a 30 LB alternative operating platform for 30 years, and somehow maintaining at least a partial grip on the cutting edge. For the people who built over a million finely-tuned Oliver machines in Woodstock, these machines also represented a livelihood, a tight knit community, and a sense of pride. A century later, the first “visible writer” is still certainly a sight to behold.

On that note, we’ve got a rusty Model No. 5 Oliver Typewriter in the museum collection, too, which may date as far back as 1907. You can click the photo above to learn more about that particular model.

More Images of the Oliver Typewriter Model No. 9

Sources:

U.S. Patent 528,484A – “Type-writing machine”

The Oliver Typewriter – catalog, 1908

Instructions for Using the Oliver Typewriter No. 3 – circa 1900

Oliver Typewriters – Catalogue No. 3, 1902

“1893 Woodstock Plant Runs Out of Time” – Chicago Tribune, February 11, 1997

“Woodstock Held Key to Typewriters” – Chicago Tribune, February 16, 1997

“Memorial Service For Thomas Oliver” – Woodstock Sentinel, Feb 11, 1909

“Iowa Preacher Invents Typewriter” – Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, March 29, 1908

“A New Cotton Picker” – Charlotte Observer, May 15, 1908

“Another Cotton Picker to Be Tried Here” – Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, Feb 6, 1909

“Inventor Dies in L Station” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 10, 1909

“The True History of the British Oliver Typewriter Manufacturing Company (1927-1960)” – oztypewriter

“Oliver Typewriter Building Ready in Record Time” – Ad, Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1907

“Build More Houses” – Woodstock Sentinel, March 19, 1903

“Won the First Game: Oliver Typewriter Baseball Nine Make a Good Start” – Woodstock Sentinel, May 22, 1902

“King of Typewriters” – Woodstock Sentinel, Dec 19, 1901

I have an Oliver No 9 with the ser. No 349344 and it does work what is the val of it and where can I get a Ribbon for it Thank you

I have a typewriter desk made by them with the branded name as copywrite. I can’t find anything on the desk.

I have a no9 that is missing one letter key tab. (the plastic piece that has the letter of that particular key) I want to know if there is any way to get a replacement. Also the no9, was it manufactured for several years or just 1? If only 1 then what year was that? Did it only come with one color ink or could you change the ribbon to a different color? Lastly, approximately how much would my no9 Oliver in great condition with only one missing tab, be appraised?

My Woodstock typewriter has the serial number N206863.

Could someone please tell me the model and year built? Also, where can I find replacement ribbons (or parts)? Lastly, the keys have removable plastic covers with the appropriate letter. These snap onto/on top of the regular keys. What is the purpose of these caps?

Thank you very much for any information.

Mark Lamb

I live in the U.K and have a model 7 machine in working order. Does it have any value?

Two years ago, I purchased an Oliver. In the back is a black ribbon attached to a triangle shaped ring. The ribbon and ring are not attached at the ring end. Is there a repair manual

and a parts house?

Hello,

Do you still have access to the following articles? I am researching Thomas Oliver and The Oliver Typewriter Company and am not sure where I can view these articles. If you know where I could view them or are able to provide them to me I would greatly appreciate it. Thank you!

“1893 Woodstock Plant Runs Out of Time” – Chicago Tribune, February 11, 1997

“Woodstock Held Key to Typewriters” – Chicago Tribune, February 16, 1997

“Memorial Service For Thomas Oliver” – Woodstock Sentinel, Feb 11, 1909

“Iowa Preacher Invents Typewriter” – Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, March 29, 1908

“A New Cotton Picker” – Charlotte Observer, May 15, 1908

“Another Cotton Picker to Be Tried Here” – Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, Feb 6, 1909

“Inventor Dies in L Station” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 10, 1909

“Oliver Typewriter Building Ready in Record Time” – Ad, Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1907

“Build More Houses” – Woodstock Sentinel, March 19, 1903

“Won the First Game: Oliver Typewriter Baseball Nine Make a Good Start” – Woodstock Sentinel, May 22, 1902

“King of Typewriters” – Woodstock Sentinel, Dec 19, 1901

The easiest way to access all of those articles is through a newspapers.com account, which enables keyword searching through the archives of numerous local papers.