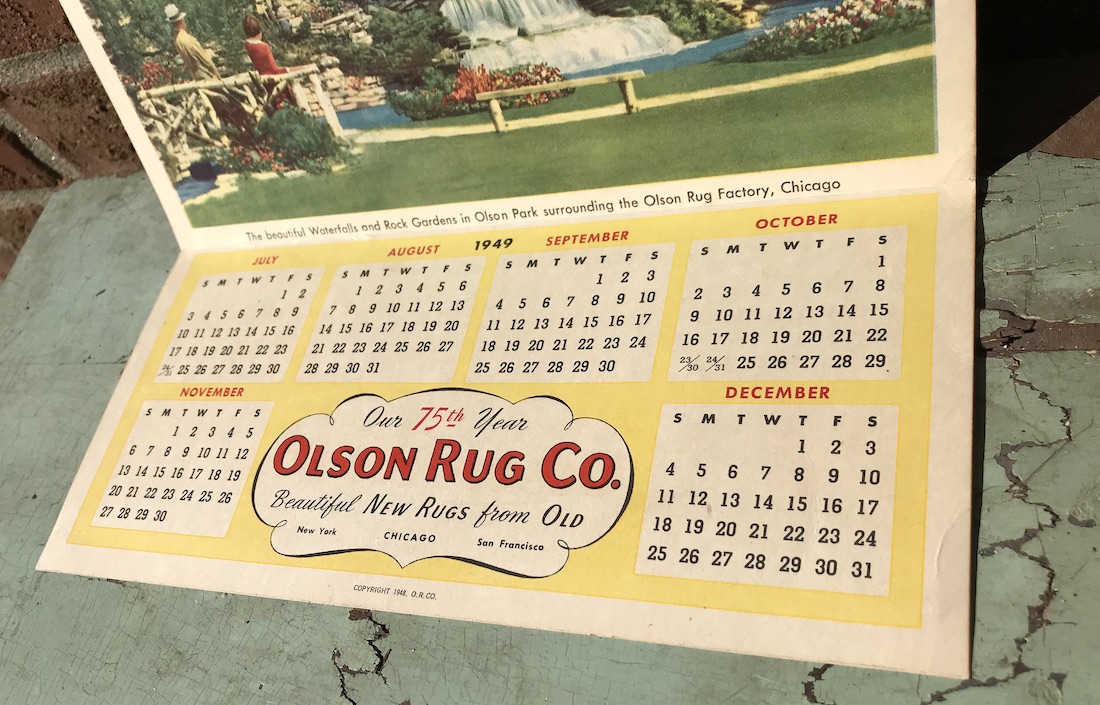

Museum Artifact: Olson Rug 75th Anniversary Calendar, 1949

Made By: Olson Rug Co., 2800 N. Pulaski Rd., Chicago, IL [Belmont Gardens]

No other manufacturing business in Chicago ever had a headquarters quite like that of the Olson Rug Company. From 1935 to 1965, the sprawling Olson factory campus at the northwest corner of Diversey Avenue and Pulaski Road—with its stunning man-made waterfalls, rock gardens, sculptures, and light shows—didn’t just serve as a nice place for workers to have their lunch breaks. It was open and free all day to the general public, as well; an oasis of nature and beauty in an otherwise grey and industrial section of Avondale / Logan Square.

The Olson Memorial Park was attracting upwards of 200,000 visitors per year by the time the calendar in our museum collection was printed in 1949, marking the 75th anniversary of a Chicago rug weaving institution. Another 75 years have nearly passed in the interim, and while the Olson brand name still exists in the form of eight small Chicagoland retail stores, most people have forgotten the glory days of the original company, when it was one of the largest and most progressive manufacturing firms of its kind.

The Olson Memorial Park was attracting upwards of 200,000 visitors per year by the time the calendar in our museum collection was printed in 1949, marking the 75th anniversary of a Chicago rug weaving institution. Another 75 years have nearly passed in the interim, and while the Olson brand name still exists in the form of eight small Chicagoland retail stores, most people have forgotten the glory days of the original company, when it was one of the largest and most progressive manufacturing firms of its kind.

Even setting aside their early adoption of green industrial spaces, the company’s entire business model was arguably “eco-friendly” many decades before that term entered the general vernacular. A high volume of Olson rugs were literally produced from recycled materials, after all—sourced from the public, woven anew, and sold back to them at discount prices. “Beautiful New Rugs from Old,” as the slogan goes on the 1949 calendar. The company didn’t waste money and energy sending door-to-door salesmen across the country with carpet samples, either. They relied entirely on advertising, mail order catalogs, and a few classy showrooms. It all worked, too, as a tiny mom-and-pop business, founded by a Norwegian immigrant just after the Great Chicago Fire, wound up employing close to 2,000 Chicagoans at its mid 20th century apex.

History of the Olson Rug Company, Part I: “Send ‘em to the Rug Man”

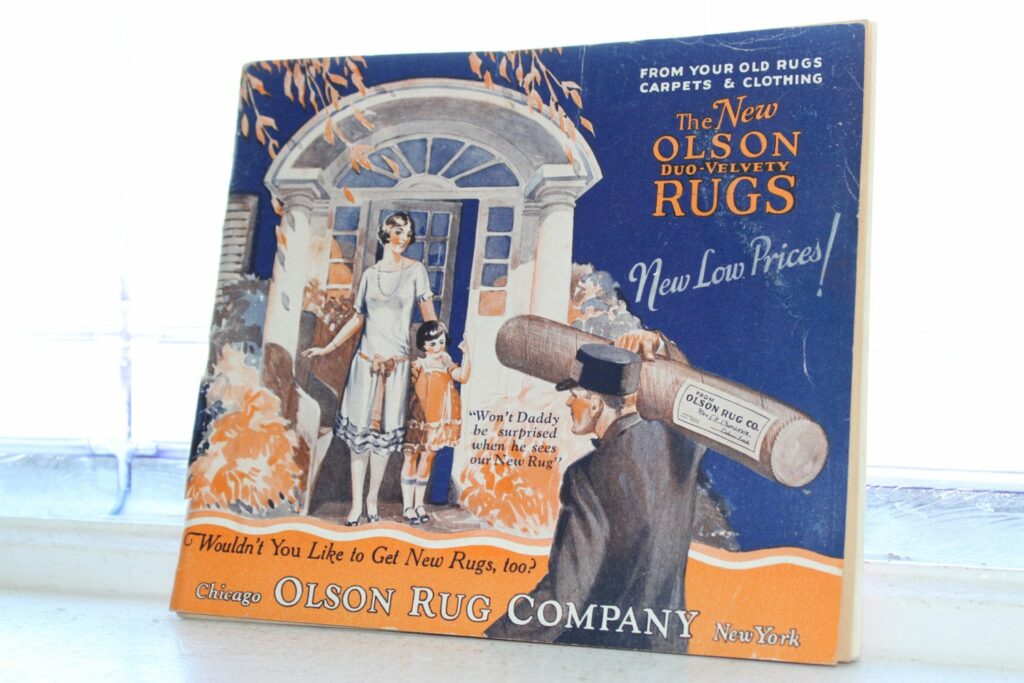

Any time you’re talking about a family business built from humble origins, the “establishment” of said business is likely to become a matter of folklore over time. The Olson Rug Company always pinpointed their founding to 1874 (hence the 75th anniversary in 1949), when founder Oliver B. Olson supposedly invented the “Olson Fluff Rug”—a hand-weaved product made from older, repurposed fabrics. “O. B. Olson conceived the idea,” according to a 1932 issue of The Santa Fe Magazine, “that thrifty American housewives were unknowingly throwing away, in the form of their old carpets, rugs and worn out clothing, valuable woolen materials that could readily be utilized in the weaving of fine new rugs.”

Since Oliver was also the sole employee of “O. B. Olson & Co.” in those early days, however, it’s fairly impossible to get a real sense of what he was up to, and whether the “fluff rug” was as novel as it seemed. Instead, we’re left with much later accounts like Louis James’s sappily patriotic “Men Who Make America Great” newspaper column, which offered up an Olson origin story, trumpets ablare, in 1959.

Since Oliver was also the sole employee of “O. B. Olson & Co.” in those early days, however, it’s fairly impossible to get a real sense of what he was up to, and whether the “fluff rug” was as novel as it seemed. Instead, we’re left with much later accounts like Louis James’s sappily patriotic “Men Who Make America Great” newspaper column, which offered up an Olson origin story, trumpets ablare, in 1959.

“Chicago has written some celebrated events into U.S. history—apart from that famous fire,” James wrote. “Not the least of them occurred one mid-summer day in 1874. On that day O. B. Olson moved into a small cottage at Ohio Street near Ogden Avenue and started to weave rugs. He worked alone. When he finished a rug he tucked it under his arm—and sold it. From that modest start to the huge enterprise it spawned is a story of a dedicated man—and an equally dedicated son.”

Unfortunately, James doesn’t really go on to provide the story of the “dedicated” father in any more detail. We’re only told that he was “delivering rugs to lots of Chicagoans, and a few in the outlying areas,” and that when he died in 1901, his teenage son Walter took over, using that “paternal training, supplemented by his own youthful energies, to push the Olson Rug Co. into high gear.”

[1901 advertisement for O. B. Olson & Co.]

The small problem here is that Oliver B. Olson—Norwegian immigrant, devout Lutheran, weaver of rugs— actually died in 1895 at the age of 44, when his son and heir Walter Eugene Olson (b. 1884) was just 11 years old—not exactly prime age to start pushing the family business into “high gear.”

We do know that O. B. Olson & Co. stayed in business in the intervening years after Oliver’s death, perhaps run by his widow Augusta or another family member. Whoever it was, they deserve some credit of their own, because by the time Walter Olson finally finished high school and took over the business himself in 1902, it was already employing 41 workers in a manufacturing plant at 375 W. Lake Street.

From there, Walter’s “youthful energies” were let loose, and by 1906, he and his business partners, Joseph E. Heckel and Louis S. Swenson, had organized and incorporated the new Olson Rug Company with a capital of $50,000, complete with a downtown office at 278 W. Madison St. and a bigger factory at 1373 Carroll Avenue, now employing about 200 people. Considering both Olson (president) and Heckel (secretary) were just 22 years old at the time, it’s hard not to be impressed.

From there, Walter’s “youthful energies” were let loose, and by 1906, he and his business partners, Joseph E. Heckel and Louis S. Swenson, had organized and incorporated the new Olson Rug Company with a capital of $50,000, complete with a downtown office at 278 W. Madison St. and a bigger factory at 1373 Carroll Avenue, now employing about 200 people. Considering both Olson (president) and Heckel (secretary) were just 22 years old at the time, it’s hard not to be impressed.

Interestingly, in Walter Olson’s obituary some 70 years later, a slightly different story is told; one in which he “started to work when he was 18, buying two wooden hand looms for making rugs. He and his wife Ida [married 1908] then worked into the small hours of the morning to make a success of the business. ‘Mr. Olson was a human dynamo—with vision,’ Ida said, ‘and I was a jack-of-all-trades.’”

Perhaps Walter and Ida saw the value in creating a little folklore of their own, casting themselves as sweaty-palmed Dickensian weavers, hand-making each rug by candlelight, rather than the owners of a rapidly growing 20th century industrial juggernaut.

You can see this same idea—the promotion of a false folksiness—as early as 1906, when one of the company’s first big national campaigns introduced the Olson business as if it was one friendly tradesman working out of a Chicago cottage, like Oliver Olson might have been 30 years prior.

[1906 advertisement for the newly incorporated Olson Rug Co.]

“I Will Make Beautiful Rugs From Your Old Carpets,” the ad’s headline read, emphasizing the first-person singular. “Don’t sell your old carpet or rug to a rag man for a few pennies, send the same to me—‘Olson the Rug Man.’ Don’t bother to beat or clean it—just tie a rope ‘round it—put on a tag with my address—when it arrives, I’ll pay the freight. Then I will renovate it, weave it carefully into a handsome new rug in plain, oriental, or fancy design of soft, pliable texture, closely woven and at very small expense. It makes no difference where you live—my customers range from Maine to California. I guarantee my rugs to be rich and durable, and to lie flat and smooth.”

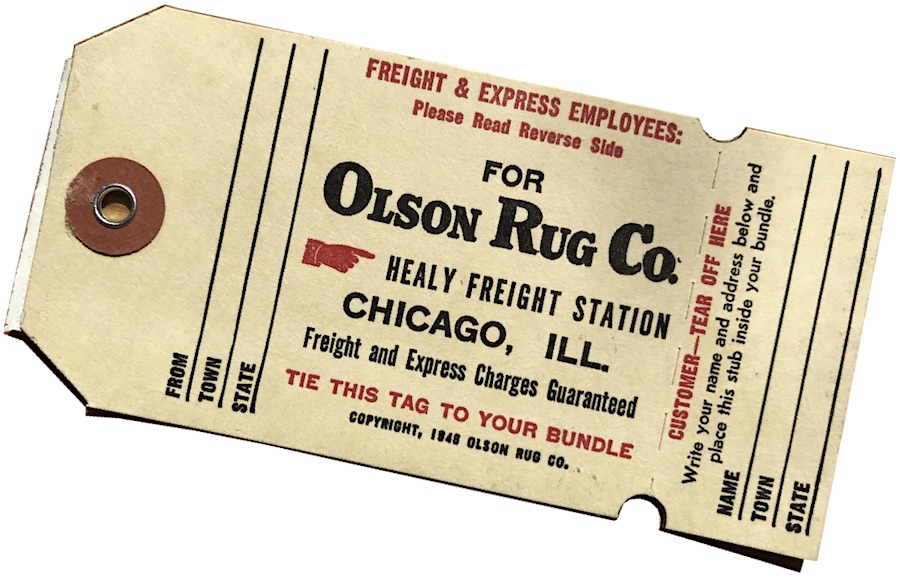

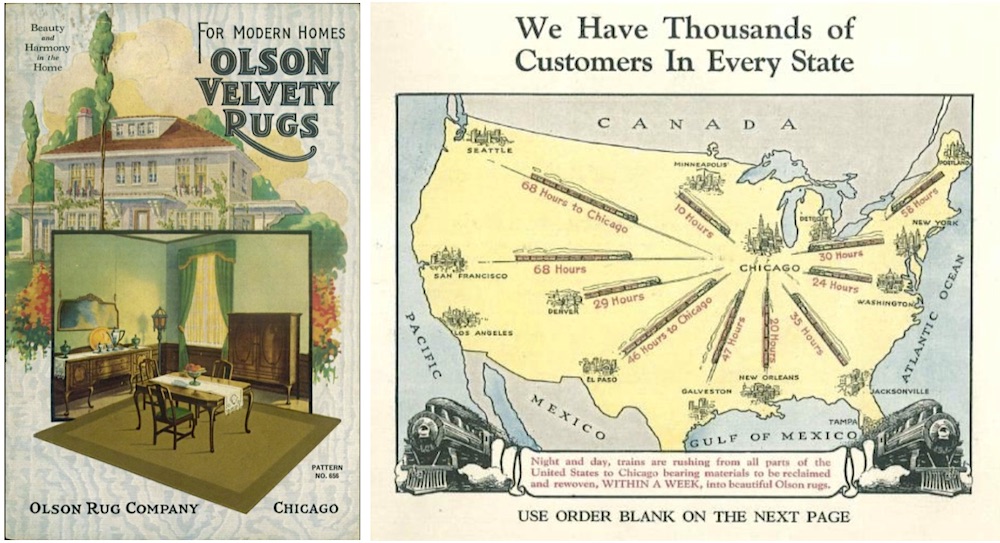

That same ad also says “Reliable Agents Wanted,” but Olson soon scrapped that concept entirely, seeing a middle-man sales force as an increasingly unreliable and unnecessary waste of money in the age of the mail-order superpowers like Sears-Roebuck and Montgomery-Ward. “Olson the Rug Man” shifted completely to catalog sales in the years ahead, and—utilizing America’s mighty rail system—found huge success taking in the country’s old ragged rugs and sending them back out again, reborn for the new century.

That same ad also says “Reliable Agents Wanted,” but Olson soon scrapped that concept entirely, seeing a middle-man sales force as an increasingly unreliable and unnecessary waste of money in the age of the mail-order superpowers like Sears-Roebuck and Montgomery-Ward. “Olson the Rug Man” shifted completely to catalog sales in the years ahead, and—utilizing America’s mighty rail system—found huge success taking in the country’s old ragged rugs and sending them back out again, reborn for the new century.

In the years ahead, as he joined Chicago’s millionaire class, Walter Olson would hear himself referred to as a “tycoon,” “industrialist,” and “magnate,” or, as a friendlier consequence of all three, a “philanthropist.” None of these descriptors ever pleased him, though.

“Just call me Walter Olson . . . Rug Man,” he told those who asked.

II. “Beautiful New Rugs From Old”

In 1911, Olson Rug had a new six-story factory and warehouse completed at the northwest corner of Monroe and Laflin Street (1500 W. Monroe / 28-42 S. Laflin) in the West Loop. Known as the Olson Building, it cost about $60,000 to construct (or roughly $1.5 million in today’s money), and featured 225,000 sq. ft. of floor space plus all mod cons and compatibility with new electric machinery. The result: a production spike of up to 1,200 rugs per day, available in dozens of unique patterns and styles.

While the plant on Monroe Street was only the company headquarters for about 15 years, and never became the public gathering spot that its successor would, the building has survived to this day nonetheless, with the original “Olson Building” lettering still visible above the front entrance on Laflin Street. After numerous other companies used the space over the past century, it was converted into a residential building in more recent years, with two more stories added, as well.

[The Olson Building at Monroe at Laflin, as seen in a 1922 catalog and today. The Olson name is still there above the main entrance after more than a hundred years]

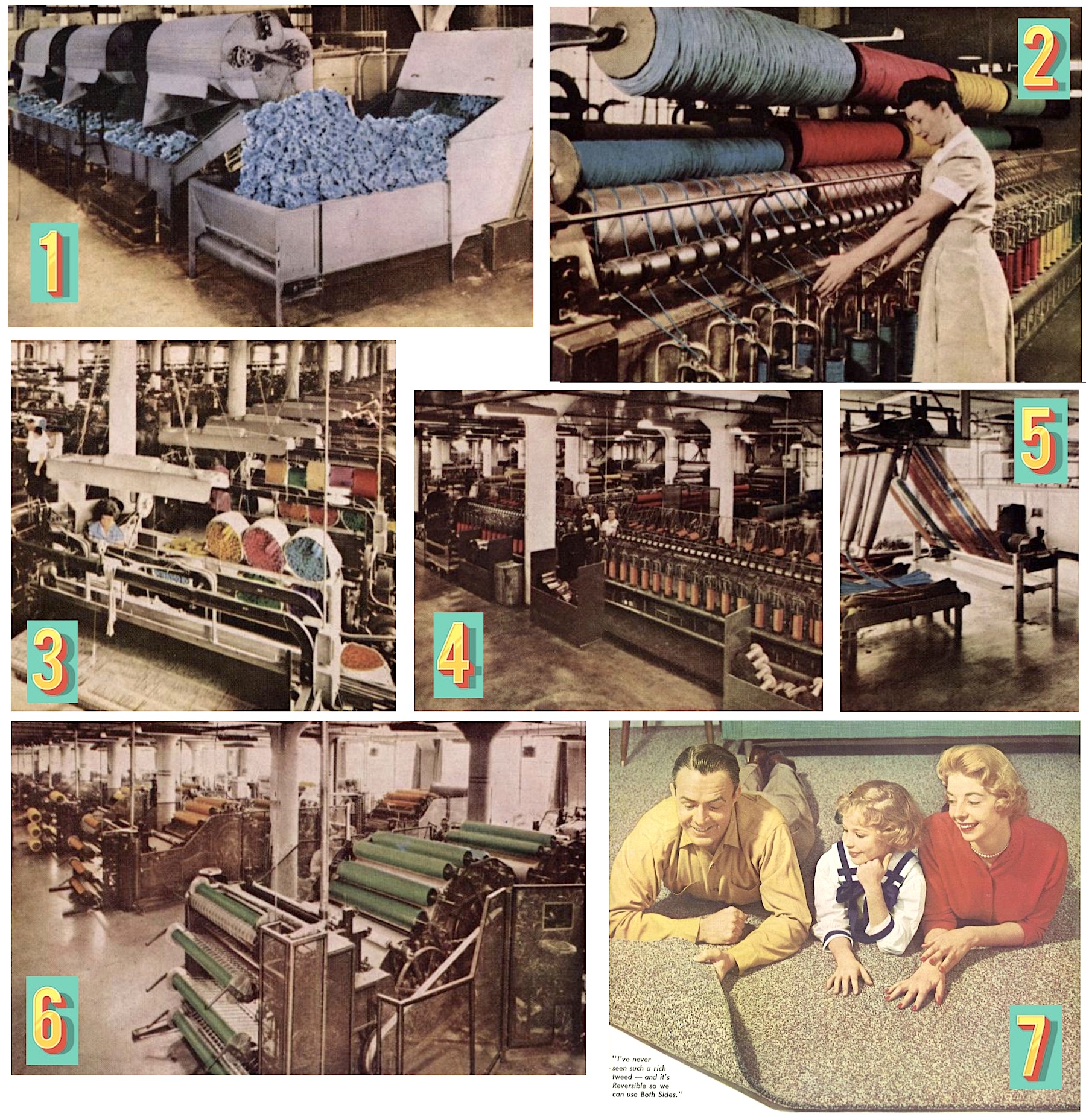

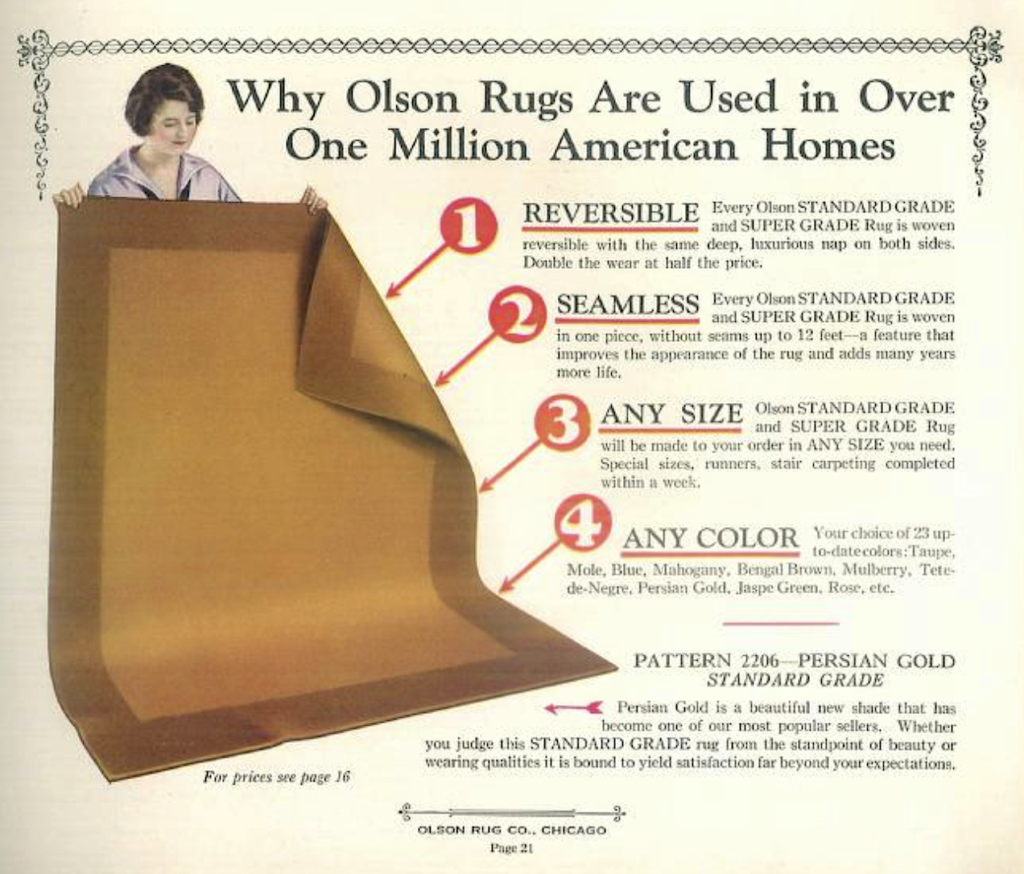

After World War I, Olson’s catalogs rapidly evolved, as well, featuring full-color sample images and step-by-step details on how each rug was made, essentially overwhelming would-be customers with the sheer scientific precision of the company’s “patented process.”

“The intensely interesting story of how your old material is transformed within one week into beautiful new, rich-toned OLSON VELVETY RUGS is a lesson in efficiency and practical economy,” read the 1922 catalog. “Aided by the most improved machinery, perfected and patented by the Olson Rug Company, our expert workmen are able to reclaim the material in your old carpets, rugs, and old clothing and weave it into new rugs, so superior to rugs made by any other concern from old material, that there is no comparison.”

By the 1920s, Olson already had a fleet of “auto trucks” that would collect every customer’s raw materials, so to speak, from Chicago’s freight depots. They would then be weighed and marked with a card noting the specific instructions for each order. Once leaving the scales, all the old material then went through the same gauntlet at the Laflin Street plant:

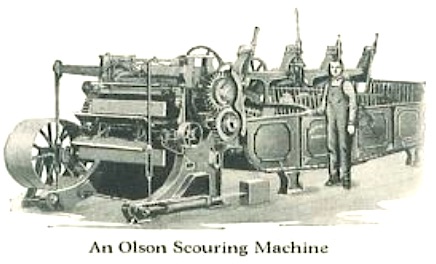

Cleaning & Scouring:

Cleaning & Scouring:

Washing and disinfecting the old fabrics to remove stains, grease, etc. Bleaching would soon be added to the first phase, as well, where the old colors of the previous rug/carpet/clothes would be eliminated to prep the material for its new life.

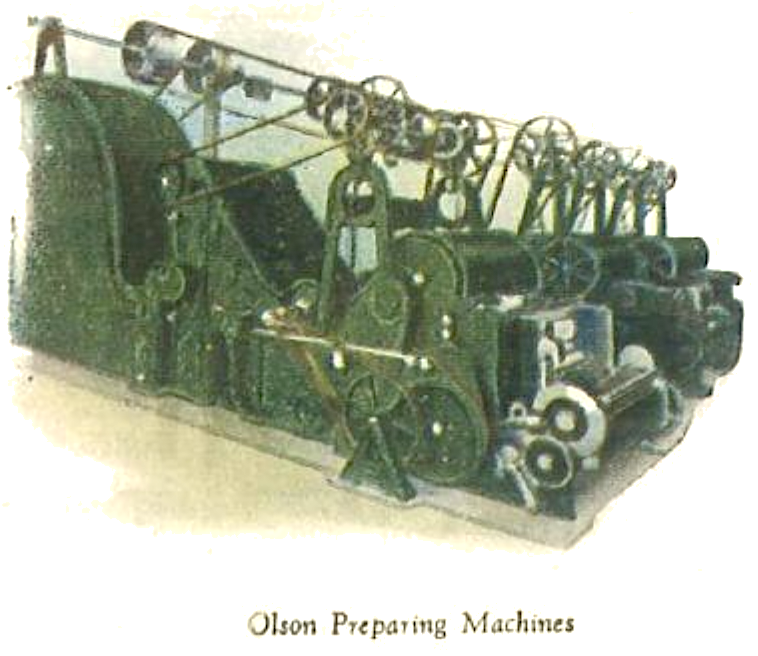

Reclaiming the Wool:

Reclaiming the Wool:

Sending the material through an automatic wringer, a drying room, a patented “preparing machine” (which cuts up the material), and a pickering-and-carding machine, which combs the material into “long, soft, fluffy fibres—the equal in every respect of new wool.” Each preparing machine cost over $5,000 and could produce 7,000 LBS of material per day.

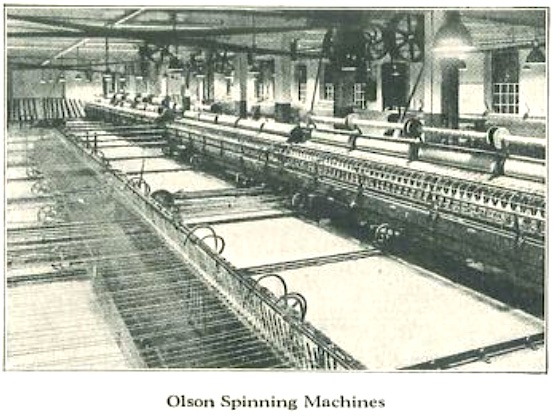

Spinning:

Spinning:

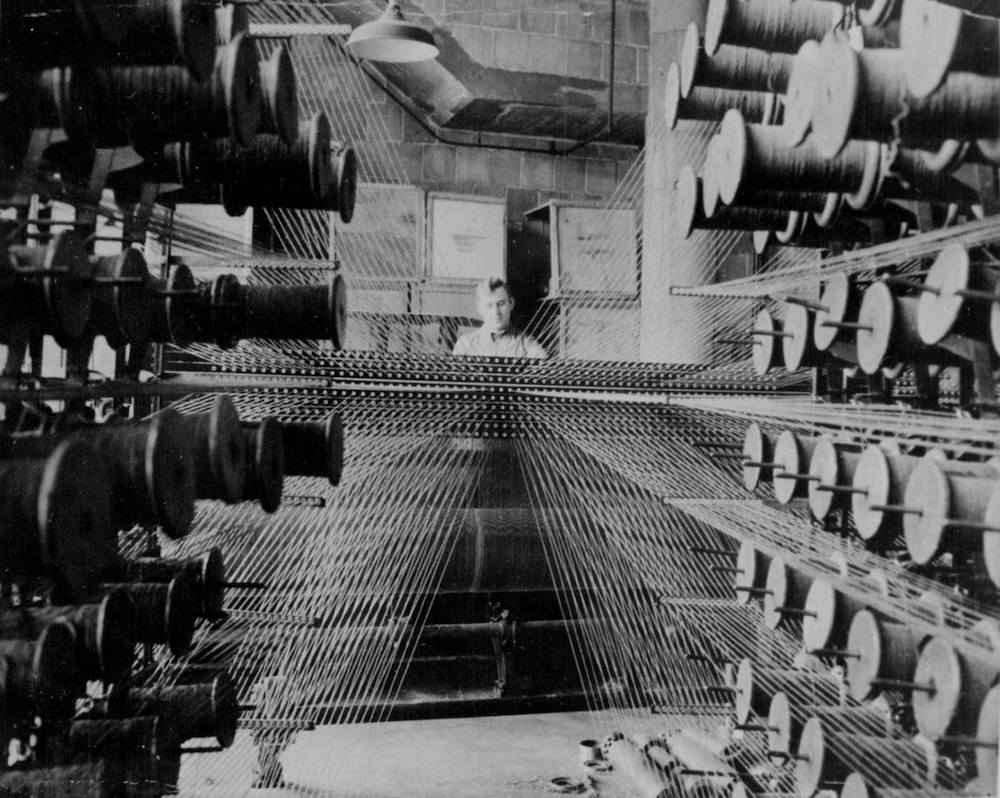

A fleet of 125 ft. long spinning machines then spin the fibres into fine rug yarn. “The remarkable strength and extreme tightness of the yarn are responsible for the long life of service one gets from Olson Velvety Rugs.”

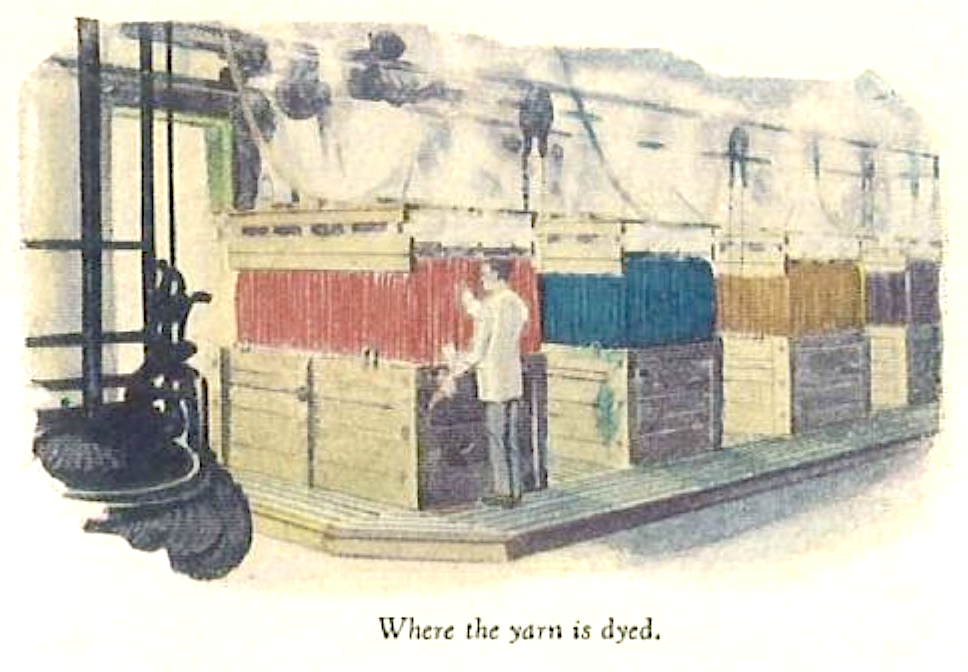

Dyeing:

A “force of expert chemists” dye the yarn the exact shade requested for the new rug, then steam dry it, wind it into cops, and send it to the Olson power looms. The dyeing method used allows the yarn to remain pliable and soft, “adding longer life to your rugs. ”

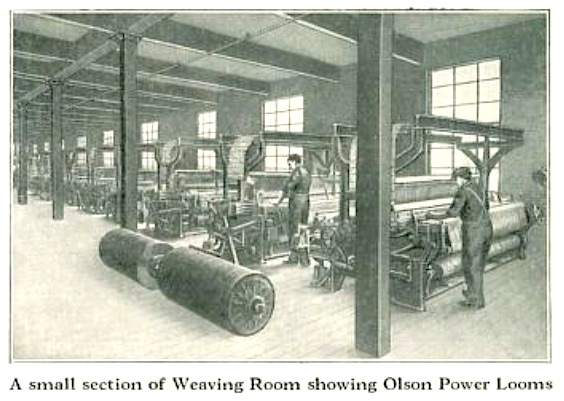

Weaving:

Weaving:

Olson’s “skilled weavers, many of whom have been with us for more than 35 years, weave the yarn in your rug in such a way as to bring out all the rich lustre. The power looms ‘beat’ the yarn into the rug with such force that the body is as strong as leather.”

Warp:

“The strongest chain is no stronger than its weakest link, and a rug is no stronger than the warp on which it is woven.” Whereas most rug weavers were using two or three-ply warp, Olson always weaves with long staple, hard-spun, four-ply warp with its power looms. So, clearly, that’s better.

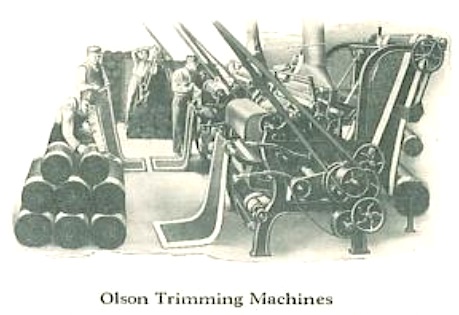

Binding, Trimming:

Binding, Trimming:

More patented machines “coil the heading ends and lock-stitch twice,” giving the rug “a substantial binding and a neat finish.” It’s then put through a trimming machine to shear the surface to “perfect evenness.”

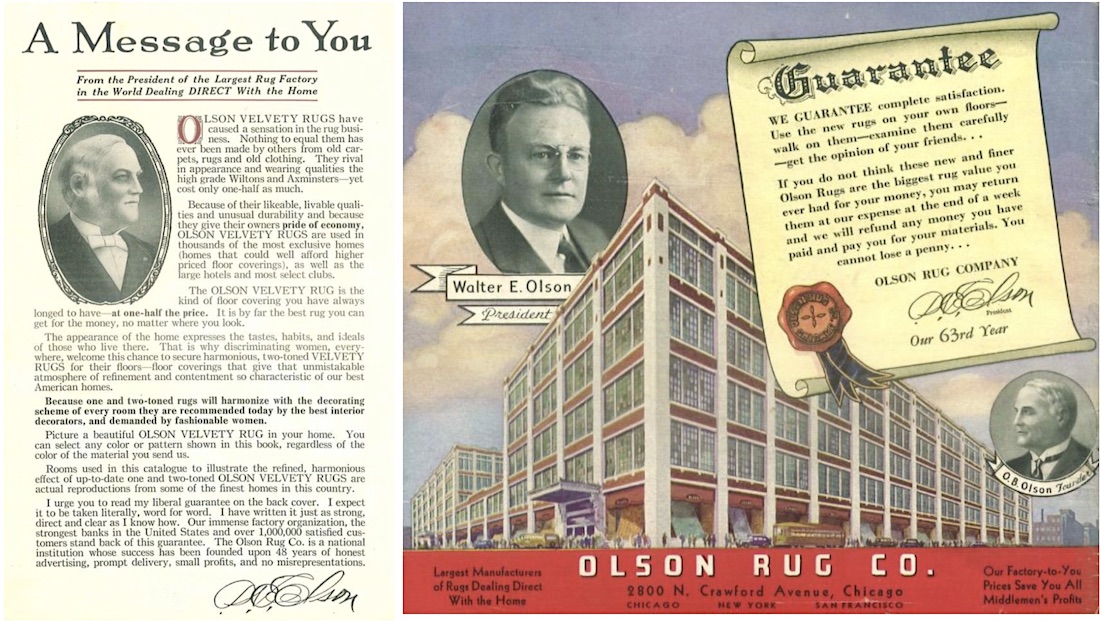

With his company being this transparent about its industrial might, Walter Olson’s humble “Rug Man” persona was no longer viable as a marketing gimmick. But for some reason—rather than stepping out as the proud president of a highly successful coast-to-coast corporation—he seemed strangely dedicated to keeping his own name and likeness out of company literature during the 1910s and ‘20s. The introductions written at the beginning of each catalog, for example, were attributed to someone identified only as “The President of the Largest Rug Factory in the World Dealing Directly with the Home,” and they were usually accompanied not by a photograph of Walter, but an old portrait supposedly depicting his late father, the “Founder” (oddly, the images of O. B. Olson used in many Olson catalogs seem to depict a man quite a bit older than O. B. himself, who didn’t live past 44). Even the handwritten signature at the end of each message looks intentionally illegible—a sort of weird combination of Walter E. and Oliver B.

Was Walter weary of the spotlight? Was he just trying to keep his father’s spirit alive in a bizarre way? Who knows. But once the Great Depression set in, the old rules of engagement were apparently thrown out—Walter finally started showing his face, both in his catalogs and increasingly in public; and it was a face his customers and employees all seemed to like just fine.

[In the introduction to the 1922 company catalog (left), Walter Olson’s name is never directly mentioned, and only a presumed portrait of his long deceased father Oliver is displayed. By 1936 (right), Walter was finally pictured prominently, and a smaller picture of Oliver—possibly edited to look less annoyed than the original version—is now identified as “O. B. Olson, Founder.”]

III. Great Gains and Painful Losses

“We guarantee complete satisfaction. Use the new rugs on your own floors—walk on them—examine them carefully—get the opinion of your friends . . . If you do not think these new and finer Olson Rugs are the biggest rug value ever had for your money, you may return them at our expense at the end of a week and we will refund any money you have paid and pay you for your materials. You cannot lose a penny.” —Walter E. Olson, the Olson Rug Guarantee, 1936

Interestingly, some of Walter Olson’s most ambitious work seemed to coincide with some of the most challenging periods of his life.

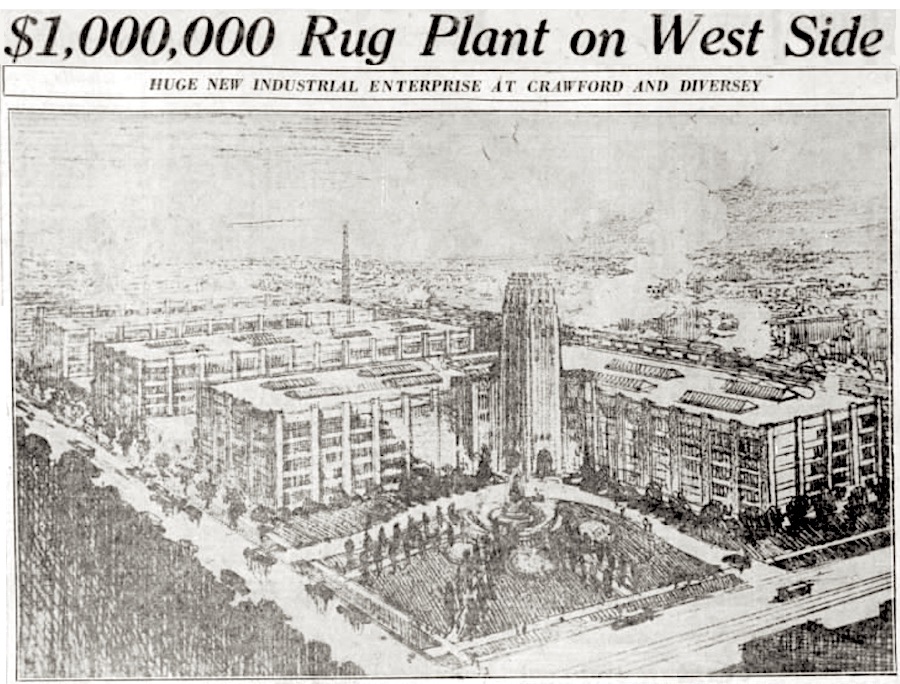

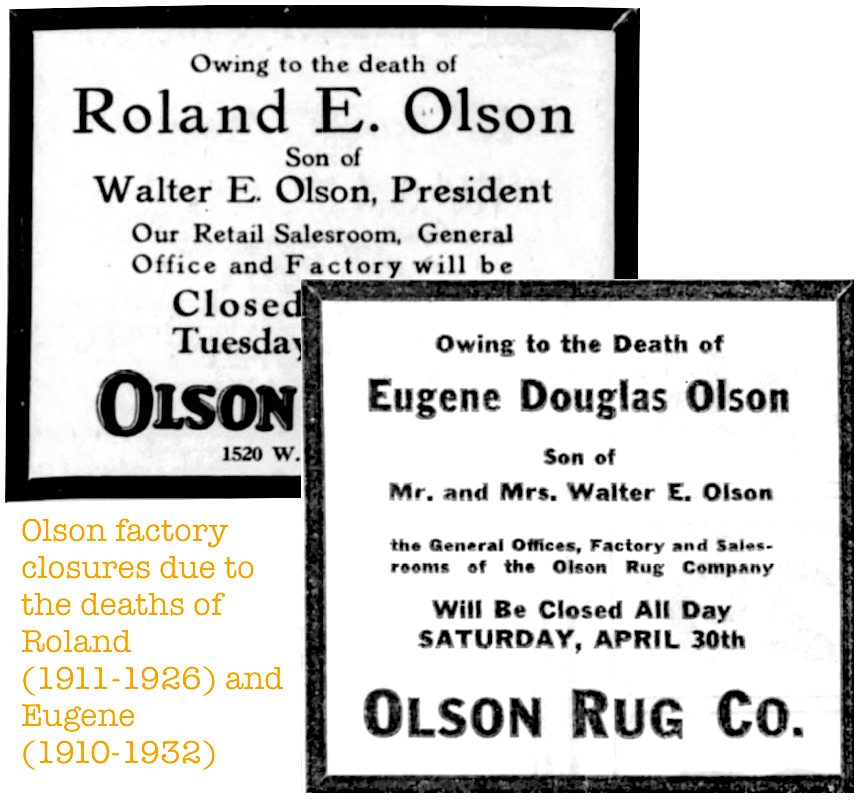

In 1926, just a few months after his son Roland E. Olson died unexpectedly at just 15 years of age, Walter announced the launch of several major expansion projects, including the opening of large Olson retail stores at 3121 N. Lincoln Ave. and 4025 W. Madison St., and—of far greater significance—the building of a $1 million, five-story mega-plant at the northwest corner of Diversey and Crawford Avenue (later renamed Pulaski Rd.). The building, which was actually just the first of several Olson that would build on the 20-acre property, was ultra-modern by 1920s standards, and still aesthetically pleasing by 2020s century standards.

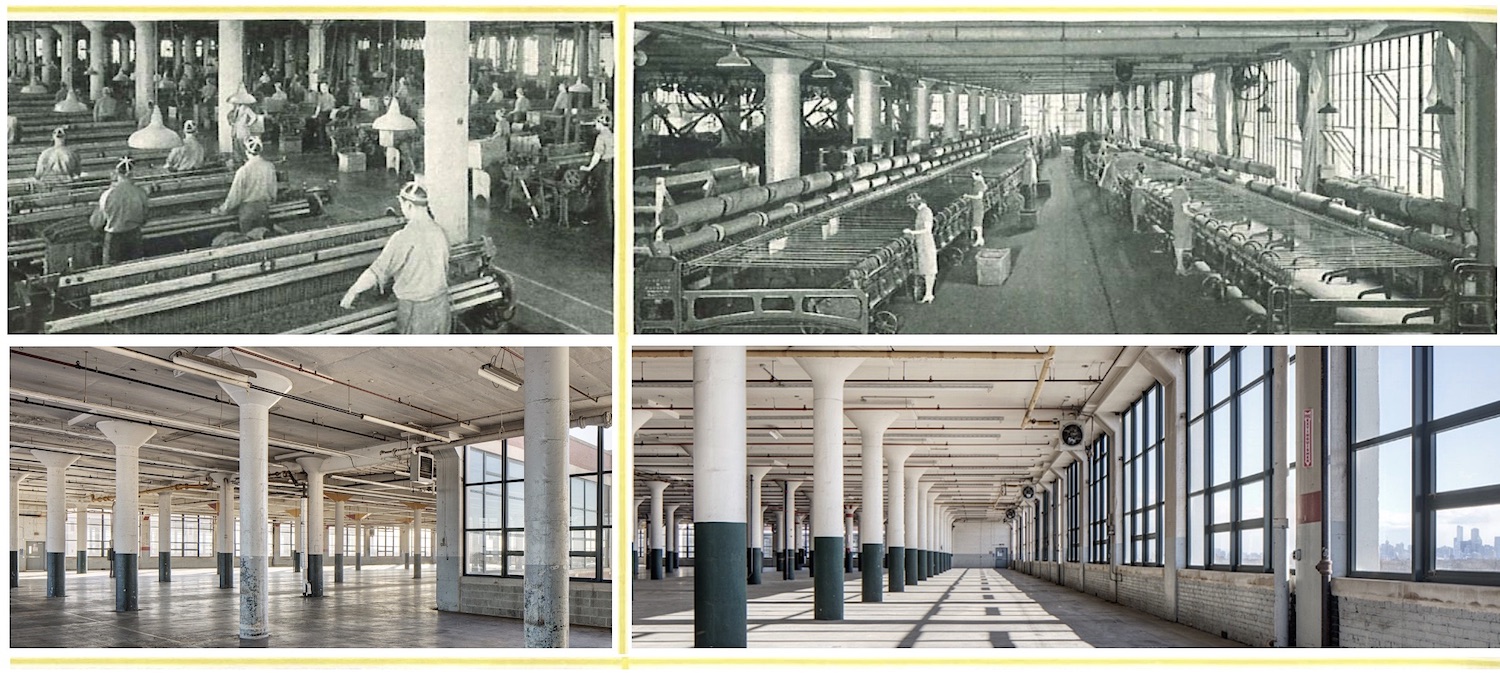

“The character of the building is really what grabbed us from the first time we saw it,” says John McLinden, who recently led the project to convert the old abandoned Olson complex into new apartments and offices, known as The Fields Lofts. “It’s got these beautiful tall ceilings from 14 to 17 feet; incredible concrete columns; steel windows that span up to 10 feet tall. It’s just rich in character and detail.”

The spacious Olson plant was built in 1926 with the idea of turning Chicago into America’s new rug-and-carpet hub, a title held for generations by Philadelphia. As part of the plan, Olson would also start making their own high-end Wilton and Axminster rugs using more imported wools from “far flung parts of the world,” brought directly up to the plant’s door via the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul railroad.

[Then & Now: The Olson Rug Factory at Diversey and Pulaski, circa 1930 vs 2019. Many of the original features were retained as the complex was converted into the “Fields Lofts,” which opened in 2019]

“When the machinery, already ordered, is installed,” Walter told the Tribune ahead of the new factory’s opening, “we intend to extend an invitation to the general public, and to the school children of Chicago in particular, to see how rugs are manufactured from raw wool, through thirty different processes, into the complete rug.”

Walter’s surviving son, Eugene D. Olson, was one of those Chicago school kids at the time; a teenager finishing up high school. He would go on to attend the University of Wisconsin, and may well have become the third generation of Olsons to lead the family business, had tragedy not struck again.

In April of 1932, almost six years to the day after his brother Roland’s death, 22 year-old Eugene Olson left his parents home at 3726 N. Sheridan Rd., picked up two friends, and drove up north to visit some college cohorts in Madison. Five miles west of Elkhorn, Wisconsin, Eugene lost control of the vehicle and crashed into a tree. He and his friend Howard Black were both killed.

In April of 1932, almost six years to the day after his brother Roland’s death, 22 year-old Eugene Olson left his parents home at 3726 N. Sheridan Rd., picked up two friends, and drove up north to visit some college cohorts in Madison. Five miles west of Elkhorn, Wisconsin, Eugene lost control of the vehicle and crashed into a tree. He and his friend Howard Black were both killed.

Considering how much Walter Olson had vocally championed the “father-son legacy” of the Olson Rug Company, the losses of BOTH of his children at such young ages had to be devastating on multiple levels.

To cope with the pain, he and his wife Ida started spending more time in their secluded summer home in the woods of northern Wisconsin, enjoying the beauty of nature and getting away from the whir and hum of the factory looms. Ultimately, Walter Olson did what he usually did, and threw himself back into work. Only this time, he had found a new passion project—bringing some element of the peace and tranquility of that Wisconsin lodge to the comparatively cold and noisy environment of the Olson Rug factory.

[Olson Rug Showrooms, 1930s]

IV. The Waterfall By the Rug Factory

“It is men like my old friend, Walter E. Olson, and others who are leading America out of the depression. He has the courage to go ahead with an enterprise which will aid materially in supplying work for the building trades and furnishing steady employment for residents of this neighborhood.” —Chicago Mayor Edward Kelly, 1935

The first major expansion of the still brand-new Olson plant at Diversey and Pulaski began in 1929, as the complex was essentially doubled in size to keep up with demand. To the surprise of many, however, Walter Olson announced yet another massive expansion in 1935, despite the significantly changed financial climate brought on by the Depression.

“Contrary to the opinion of some business men with whom I’ve discussed this new unit,” Walter said, “I consider the present an excellent time to build for industrial purposes as well as homes. We are erecting this building not alone because our business warrants it, but because we anticipate an ever increasing volume this year, next year, and the years thereafter. We are building because we have utmost faith in Chicago’s future and equally as great a faith in the future prosperity of the nation.”

Now 51 years old, the “Rug Man” had gained a reputation for his people skills and political action, and he was regularly encouraged by friends to run for office, though he never did. In business, he had rarely ruffled feathers, as evidenced by the fact that the two men with whom he’d incorporated the company back in 1906—Joseph Heckel and Louis Swenson—were still part of his executive staff 30 years later (when Swenson died in 1933, he was replaced as secretary by another longtime employee, Walter’s brother-in-law Christian Reichel).

[In the late ’20s into the ’30s, Olson Rug still had its Monroe Street and Diversey plants running simultaneously]

As a do-gooder political figure, meanwhile, one of Walter’s prime pre-occupations was the horrific mob violence dominating Chicago’s headlines, and he did his best to help fund programs to get weapons off the streets. He even personally paid for a ballistic test to try and track down the perpetrators of the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929. A year later, after the stock market collapse, Walter organized a group of business leaders to promote a “Hire-a-Worker Week” in Illinois, in which “every employer of labor in the state be solicited to add one man to his staff.”

Olson took the further bold step of hiring back 900 of his own workers to full-time schedules in 1932, when most businesses were still cutting labor to stay afloat, and he subsequently embraced Roosevelt’s National Recovery Act with full confidence of an economic turn-around.

Even as wool materials became harder to come by, and stockholders wiped their brows, Walter came up with creative ways to keep his workers—many of them first or second generation Polish-Americans from the surrounding Avondale neighborhood—gainfully employed.

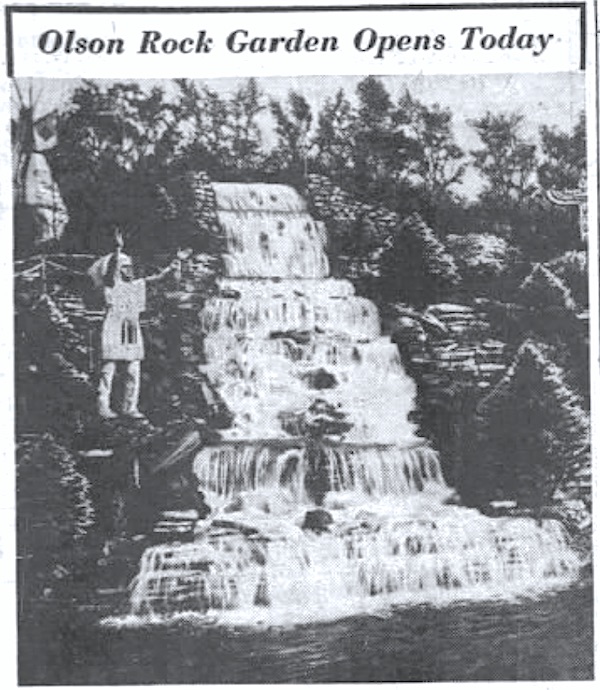

“Plans for the elaborate beautification of the ten acre plant of the Olson Rug Company, at Crawford and Diversey, were announced yesterday by Walter Olson, president,” the Tribune reported on August 11, 1935. “The landscaping program includes the immediate erection of a $10,000 rock garden, said to be the most pretentious undertaking of its kind in the country. When completed the 445,000 square feet factory site, once a farm, will be known as Olson Park, in honor of O. B. Olson, founder of the company.”

“Plans for the elaborate beautification of the ten acre plant of the Olson Rug Company, at Crawford and Diversey, were announced yesterday by Walter Olson, president,” the Tribune reported on August 11, 1935. “The landscaping program includes the immediate erection of a $10,000 rock garden, said to be the most pretentious undertaking of its kind in the country. When completed the 445,000 square feet factory site, once a farm, will be known as Olson Park, in honor of O. B. Olson, founder of the company.”

Olson used many of his own textile workers as makeshift garden builders, and he sourced the limestone and many of the trees and plants from local areas. When completed, the rock garden was at least “25 feet high, with three waterfalls cascading into a lily pond at its base.” An old dugout canoe was added to the scenery, along with sculptures of Native American figures.

As no coincidence, Olson Park’s official opening, in September of 1935, was used to commemorate Illinois’s annual “American Indian Day,” as well as the 100th anniversary of the treaty that cast Chicago’s last three native tribes—the Pottawatomies, Chippewas, and Ottawas— out of the region. Being a great admirer of Native American history and culture, Walter Olson invited representatives of those tribes and at least 10 others to take part in the event, and even figuratively “deeded” the land at Olson Park back to the tribes as a friendly—if misguided—gesture. In return, Chief Passing Storm of the Winnebago tribe named Walter an honorary chief, giving him the name Standing Buffalo.

An estimated 25,000 people attended the ceremony that day, but as word continued to spread about the park, and as Olson continued to develop it with caves, pools, bird sanctuaries, walking trails, lawn furniture, food concessions, and big Christmas galas in the winter, it became an institution unto itself—always free to the public, and often cited in the nostalgic memories of Chicagoland baby boomers.

For Olson employees, especially the increasing number of women operating the looms during World War II, the gardens were as essential to their health and well-being as any of the modern amenities within the giant 1,000,000 square foot factory itself.

[Photos of Olson Memorial Park, circa 1950s (from epigrrl)]

V. The Tufted Age

Unsurprisingly, Walter Olson received regular “Good Neighbor” honors from the city of Chicago for his efforts in the relatively new movement of industrial beautification. Year by year, he also became one of the more noteworthy and reliable philanthropic forces both in Chicago and Miami, where he and Ida were spending a lot of their time in semi-retirement.

During the war, Walter donated thousands of dollars to Army Emergency Relief, delivered 10,000 pounds of turkey to his workers for the holidays, and even had 30 special guest cottages built on his property in Wisconsin, which were set aside for the use of any Olson Rug employees looking to get away for a weekend—including working women dealing with the absences of their husbands or boyfriends fighting overseas.

Back at the factory, much of the daily work shifted from the usual rug weaving assembly line to new “defense projects,” although the commercial business was also allowed to continue—as sound, soft footing in the household was apparently still seen as an essential for civilian morale.

Back at the factory, much of the daily work shifted from the usual rug weaving assembly line to new “defense projects,” although the commercial business was also allowed to continue—as sound, soft footing in the household was apparently still seen as an essential for civilian morale.

“Yes, we are still making and selling quality rugs, carpets, and broadlooms as far as our War Work permits and within the limits set by government regulations,” read one Olson newspaper ad in February of 1944. “Of course, ‘War Work Comes First’ at the busy Olson factory—and we are mighty proud of the splendid record of our craftsmen in the production of necessary war materials.”

“It is our sincere wish,” Walter Olson personally added in another wartime ad, “that Health, Happiness, and Security will be yours during the coming year . . . and that we may all soon be blessed with Victory and a just and lasting Peace.”

When peace did come, the Olson Rug Company headed into the 1950s as a business technologically light years ahead of the one Walter Olson had first incorporated in 1906, and yet—in terms of the business model and sales pitch—not all that different at all. Almost all business was still handled by mail order, and the company was still dependent on its customers to send them the cheaper “used” fabrics required to keep the cycle of production moving.

“Due to scarcity and very high cost of new rug materials,” Walter Olson wrote in the intro to his 1949 catalog, “the money-saving Olson plan of using the valuable wools and other materials in your old rugs, carpets, clothing, etc., now deserves greater consideration than ever. . . . I am sure you, too, will find it fascinating to send away a bundle of worn woolens—and in return receive luxurious Reversible Rugs that will win the praise of your family and friends. I invite YOU to try it. I promise a PLEASANT SURPRISE.”

There was nothing inherently flawed in the tried-and-true Olson method, and yet—just as they’d been able to undercut the competition by saving on materials—the scales of progress soon began tipping against them in similar fashion. The post-war age brought the rise of “tufted carpeting” (made by 1,000+ needle industrial sewing machines), as well as cheap, man-made synthetic fibers like nylon and polyester.

Even with Olson’s enormous arsenal of churning machines and its highly trained workforce of 1,800 men and women, it still took about 10 days of labor to make just one 55-yard roll of Wilton broadloom carpet, according to a 1953 feature in the Tribune. A “tufted” carpet could be manufactured 10x faster, and synthetic fibers were much easier to produce—reducing the need for the same sort of material import infrastructure, not to mention the man power to run a dozen different machines for sorting, scouring, picking, combing, bleaching, steaming, spinning, winding, and weaving wool.

Even with Olson’s enormous arsenal of churning machines and its highly trained workforce of 1,800 men and women, it still took about 10 days of labor to make just one 55-yard roll of Wilton broadloom carpet, according to a 1953 feature in the Tribune. A “tufted” carpet could be manufactured 10x faster, and synthetic fibers were much easier to produce—reducing the need for the same sort of material import infrastructure, not to mention the man power to run a dozen different machines for sorting, scouring, picking, combing, bleaching, steaming, spinning, winding, and weaving wool.

To get a sense of how enormous this industrial sea change was, it’s estimated that about 90 percent of American rugs and carpets were woven from wool in 1950; that number is closer to 2 percent today.

By the 1960s, adaptations were being made, and synthetic fibers were increasingly being added into the construction of each Olson rug in Chicago. While still attributing their process to “sheer Olson Magic,” the company had to start revealing the fiber content of its products to oblige by the new U. S. Textile Labeling Act. In 1962, that broke down as such:

⇒ 65% New Carpet Wools

⇒ 15% New Carpet Nylon

⇒ 10% New Carpet Acetate

⇒ 10% Other Carpet Fibers

⇒ Reclaimed materials from customers now used only for the “sturdy inner” (center) of each rug.

[Olson Factory in 1960: 1 – Blending Machines, 2 – Spinning Machines, 3 – Weaving Looms, 4 – More Spinning Machines, 5 – Drying Machines for Setting the Dye, 6 – Carding & Combing Machines, 7 – Satisfied Olson customers enjoying a reversible tweed rug]

VI. Last Stitch Efforts

One of Walter Olson’s favorite employee programs over the years was something he called “Olson Guaranteed Notes”—workers could save up and purchase notes, at the cost of $100 each, and “loan” them to Mr. Olson, who’d put them in the bank to earn interest. Every July 1 and January 1, the employee would then earn 6% on their investment, with an option to renew and get new notes.

“What Mr. Olson likes about the plan,” the Suburbanite Economist reported in 1955, “is that an employee saving $100 to buy a note forms the habit of thrift. Thrift, he says, and work, made America great, adding that one of the best signs of the times and a portent of continued prosperity is that savings accounts are at an all-time high and growing each year.”

Now in his 70s, and more interested in playing golf in Florida than catching up with the polyester rug revolution, Walter Olson finally put his own thrift above his work. There would be no more factory expansions; no more throwing good money after bad.

In 1962, he sold the family business and its retail stores to the Stephen-Leedom Carpet Company of New York City, although ownership of the Chicago plant and park weren’t part of the deal. The Olson factory was to remain its own autonomous operation under the arrangement, and a new president was quickly named in the form of 56 year-old Harry Stoll, an outsider from the furniture industry. Unfortunately, Stoll died less than a year into his new job.

Around the same time, long bubbling problems started to emerge within the ranks, including accusations that Olson management had been refusing to negotiate with the Textile Workers Union of America, dating back even before the sale. New boss Emanuel Grabell righted the ship for a while, and a big push was made into franchising and expanding the Olson retail stores

Around the same time, long bubbling problems started to emerge within the ranks, including accusations that Olson management had been refusing to negotiate with the Textile Workers Union of America, dating back even before the sale. New boss Emanuel Grabell righted the ship for a while, and a big push was made into franchising and expanding the Olson retail stores

By the end of 1965, though—shortly after the deaths of both his wife Ida and longtime business partner Joseph Heckel—Walter E. Olson finally gave up the incredible factory and grounds he’d spent 40 years developing. It was sold to Marshall Field’s and converted to warehouse space, with hopes that the Olson Waterfall Park might carry on under the department store’s watch, as well. At some point in the 1970s, though—likely after Walter’s death at age 91 in 1975—paradise was unceremoniously paved over and replaced with a parking lot, Joni Mitchell style.

Meanwhile, Chicago businessman Jerry Rosenberg—owner of his own carpet shops around the region—purchased Olson’s retail operations in 1974, and his sons Richard and Robert Rosenberg continued to head up the Chicagoland stores into the 21st century, before filing for bankruptcy in 2011.

[A former Olson Rug distribution office at 832 S. Central Ave. in Chicago, seemingly abandoned in the 2010s]

Eight Chicagoland retail shops have survived, and current Olson Rug & Flooring Co. president Andrew Hader still refers to the company’s 146 year history as a selling point. The Olson name is really little more than storefront signage now, however, as it seems that no real local manufacturing has been retained. As such, any direct link to Walter Olson’s business is a bit tenuous at best.

As for the old 1.5 million square foot factory/warehouse in Avondale, Marshall Field’s eventually handed it over to Macy’s, of course, which then abandoned the Olson complex entirely. It’s only been in the last few years that the building has been fully revived as industrial-chic apartments and offices. Unfortunately, the new owners chose to pay homage to the short-lived Field’s warehouse, rather than the Olson factory, in giving the building its new identity as the “Field’s Lofts.” The rock garden and waterfall weren’t part of the rehab either, and remain, instead, a fond memory for the old-timers who still remember getting excited about a weekend trip to the local rug factory.

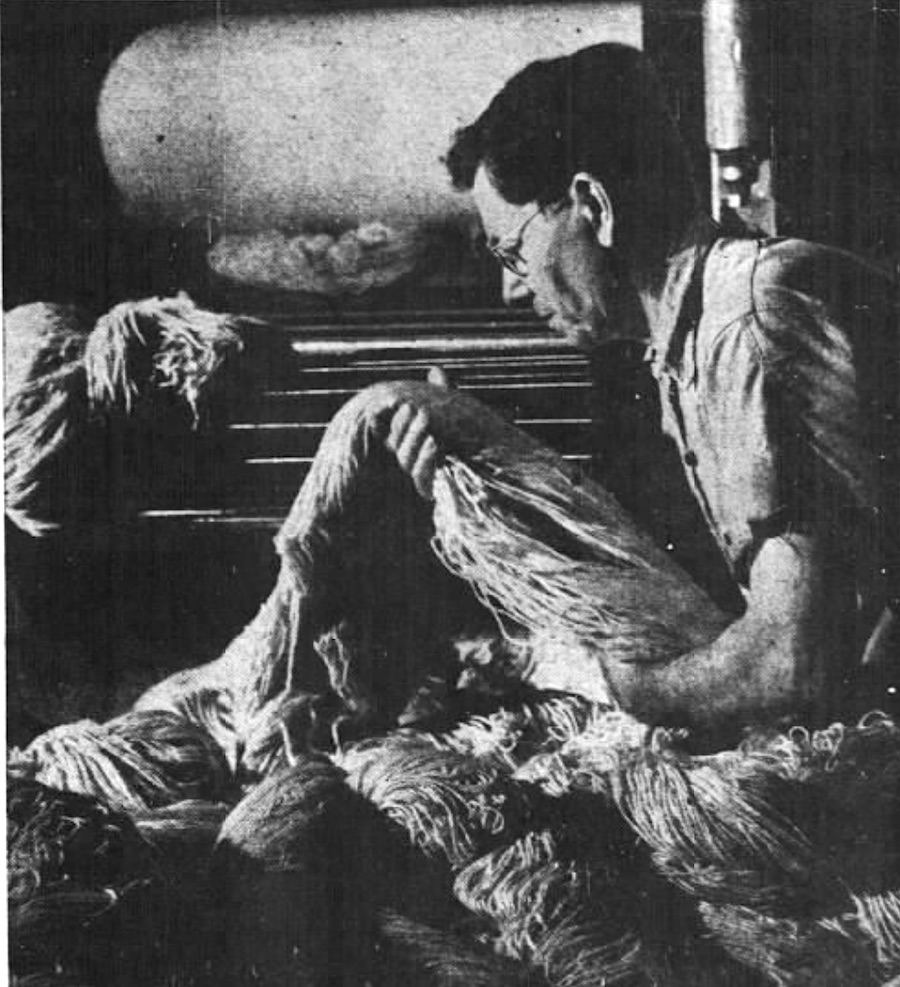

[Olson employee Louis Mohapp runs wool through a wringer in 1953]

Sources:

Olson Rug Company catalogs: 1922, 1924, 1926, 1931, 1935, 1949, 1950, 1963

“Olson Rug to Franchise Stores” – Chicago Tribune, May 12, 1967

Bankruptcy Form – Olson Rug & Flooring, Inc., 2011

“Tufted Carpeting Manufacture Developed Over Past Two Decades” – Wichita Eagle, April 13, 1955

“Harry Stoll Appointed President of Olson Rug” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 10, 1962

“Mayor Launches Work on Olson Rug Co. Addition” – Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1935

“Clerks to Give One Day’s Pay to Unemployed” – Jacksonville Daily Journal (IL), Oct 23, 1930

“Forensic Ballistics Aid Chicago Sleuthing” – Carbondale Free Press, May 4, 1929

“Dad Dearborn to Get $1,000,000 Rug Plant on West Side” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 8, 1926

“Rug Concern to Open Shop on North Side” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 14, 1926

“Olson Rug Co. Plans Store at 4025-27 Madison” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 27, 1927

“Youths, Girls, Town Official Die in Crashes” – Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1932

‘Christian Reichel Elected Secretary of Olson Rug” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 14, 1934

“Looks Bad for Fish” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 3, 1939

“Record Crowds Visit Olson Rug Co. Waterfalls” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 9, 1942

A History of the Norwegians of Illinois, by A. E. Strand, 1905

“Kids Floored By Olson Rug Park” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 18, 2009

“Rug Weaving Art Succumbs to Machine Age” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 6, 1953

“Workers Paid 6% on Notes by Olson Rug” – Suburbanite Economist, March 23, 1955

“Top Rug-to-Consumer Firm Got Its Start in a Cottage” – Mansfield Advertiser, Aug 26, 1959

“Stephen-Leedom Buys Olson Rug” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 4, 1962

“Walter E. Olson, 91; Retired Manufacturer, Philanthropist, Golfer” – Miami Herald, April 25, 1975

Archived Reader Comments:

“I remember the falls well when I was a kid. My friend and I rode our bikes there from 500 n. Avers Av. Also was a small wagon vender there selling hot dogs and snacks.” —Not Enjoyable Anymore, 2020

The Olson name lives on in northern Wisconsin at the Walter E. Olson Memorial Library in Eagle River. We are located in the area where his family vacationed and owned property, and the original library building was built through an endowment from the Olson estate.

I still have a original letter to the Olson Rug Company from June 27, 1911.

Is any body interested in it? The Letter head is very impressive and it has got a signature. And it is addressed to W.E.Fuller, Colebrook, N.H.

I bought that in 1995 on a boots sale market in London and somehow can’t through it away.

My dad, Mitch Katnik, after returning from the war in the Pacific, became head groundskeeper at the “Olson Park” during the late 50’s – early 60’s while at the same time operating the Florence Greenhouse @ Milwaukee Ave and Springfield. After that he became Superintendent of the Lombard Park District and was to become known as the “Keeper of the Lilacs”. He passed away in 2000 at 81 having worked his whole life doing what he loved!

I remember the waterfalls and flowers and all good memories. My brother keeps talking about a real big chair, maybe orange colored. Do you recall it? Really enjoyed these memories and the article. Thank you! Ingrid. 7/27/23

I remember working at my Uncle Roy’s News stand, at Milwaukee & Pulaski, at the age of 14,1968, was across the street from the Milford Ball Room and Theater. I would worked the Saturday night sift from 4pm to 1am..stuffing hundreds of papers with adds and delivering them to beeping cars that wanted the Tribune, Sun Times, & American Herald. There was a 3 star edition that got to the Stand by 11pm that had all the final scores in college and pro sports. This was best the seller of the day because many of the guys were wagering on those games and wanted to know the results after their dates on Sat night. The Milford BR &Theater shows let out at 12, so it was crazy for a 1/2 hour! I took the Pulaski bus past Olson Waterfall a lot !!

I still have 2 post cards, as well as an story of how in the front lawn was done up as fall summer. Don’t forget about all the ducks too!!

My family owns an original 11×12 Olson Rug. It is presumed to have been made in the 1920’s based on a story our father told about riding in a wagon to deliver boxes of old rags to the train depot in town. Looking through the catalogs available, I don’t see this pattern until the 1941 catalog, which is not in keeping with the family lore.

We would be curious to know if there is an appraiser or some means by which to discover the true creation date. And like Pat, we’d be curious to understand the monetary value, if there is one. PLUS, it would be great to maybe find a museum or some public display location that would like to keep this beautiful rug intact for others to ogle over.

I’ve seen the waterfall postcards, but thanks for the fascinating story!

I have an original reversible 7’ x 10’ wool Olson rug. It is in excellent condition. Does it have any value today?