Museum Artifact: “The Bear” Ortho-Scope 3-D Children’s Book, 1934

Made By: The Orthovis Company / Orthovis Publishing Co., 1328 S. Wabash Ave., Chicago, IL [South Loop]

“The amazing illustrations in ORTHOVIS educational books give the illusion of life-like depth and atmospheric distance. Through the eyes of the orthoscope that comes with each book, animals, birds and objects seem to become alive.” —Orthovis advertisement, 1938

About 90 years before there was a popular Chicago-based television series called The Bear, there was a slightly less renowned Chicago-made children’s book called The Bear. We can safely say that the former (a show about a wildly intense chef) was not based on the latter (a book literally about wild bears), but as Depression-era educational reading goes, The Bear is quite captivating in its own right, thanks to its use of early 3-D visual effects and some informative factoids direct from the staff at the Field Museum of Natural History.

About 90 years before there was a popular Chicago-based television series called The Bear, there was a slightly less renowned Chicago-made children’s book called The Bear. We can safely say that the former (a show about a wildly intense chef) was not based on the latter (a book literally about wild bears), but as Depression-era educational reading goes, The Bear is quite captivating in its own right, thanks to its use of early 3-D visual effects and some informative factoids direct from the staff at the Field Museum of Natural History.

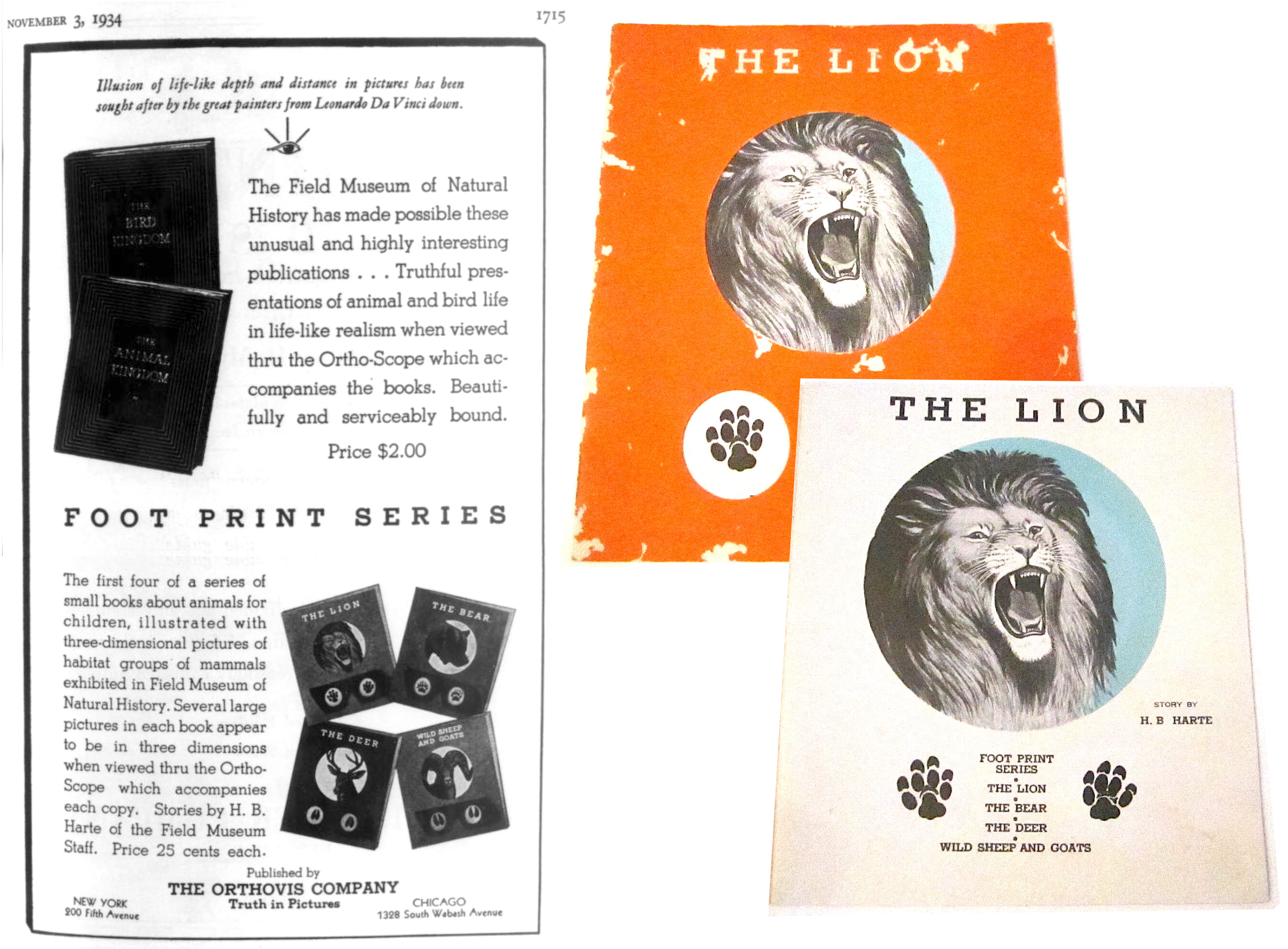

Published in 1934 by an upstart Chicago firm known as the Orthovis Company, The Bear was but one volume in “The Foot Print Series”—a collection of 3-D wildlife books developed in conjunction with the Field Museum over a 2-3 year period. Other titles included The Lion, The Deer, Wild Sheep & Goats, Giants of the Animal Kingdom, Strange Animals, Monkeys & Apes, and Wild Oxen. If you had the whole set, it goes without saying that you were the coolest kid in school . . . and maybe the only one with a stable economic home life.

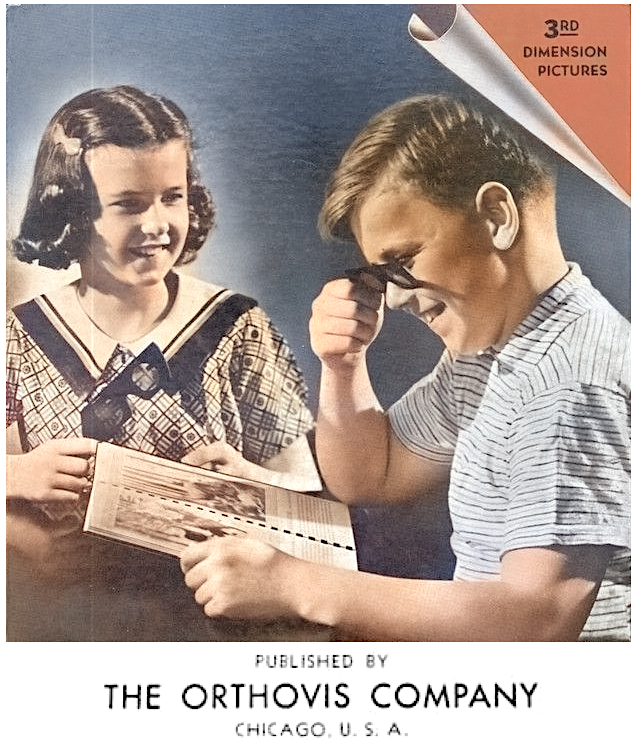

Considering that Chicago was home to some of the preeminent names in the American publishing industry, it might seem a bit odd that a respected institution like the Field Museum would partner with a relative unknown. But Orthovis Company president Montrose Newman—a lifelong salesman—was likely able to hook the curators on the so-called “Orthovis process” of “third-dimension picture” printing. It was, for all intents and purposes, a gimmick. But in the 1930s, 3-D glasses were very much in their infancy, still 20 years away from their more famous affiliation with 1950s movies and comic books. So, as a way to grab the attention of the ever-distracted youth of America, this gimmick had plenty of appeal. As Newman described it himself, “it’s almost like taking the museum into the home or the classroom, which is very nice indeed for those who cannot visit the museum.”

[Left: 1934 magazine ad for the “Foot Print Series” of books that Orthovis published in partnership with the Field Museum. Right: A look at the cover and title page of The Lion, another volume in the Foot Print Series of 1934 but as of yet not a prestigious Chicago-based TV show in the 21st century]

History of the Orthovis Company, Part I: Truth in Pictures

Founded in the early years of the Great Depression, the Orthovis Company wasn’t just a publisher that embraced 3-D visuals—it was entirely organized with that purpose in mind. The company name, after all, translates loosely to “see true,” and the slogan associated with many of its products communicated the same message: “Truth in Pictures.”

Headquartered at 1328 South Wabash Avenue in the former Coca-Cola Building, Orthovis was also affiliated in some fashion with its nextdoor neighbor: the unfortunately named Dickery Company (1322 South Wabash). Owned by Montrose Newman’s business partner E. J. Dick, the Dickery Co. published some 3-D books of its own during the same period in the mid 1930s, though with considerably less promotional effort behind them.

Headquartered at 1328 South Wabash Avenue in the former Coca-Cola Building, Orthovis was also affiliated in some fashion with its nextdoor neighbor: the unfortunately named Dickery Company (1322 South Wabash). Owned by Montrose Newman’s business partner E. J. Dick, the Dickery Co. published some 3-D books of its own during the same period in the mid 1930s, though with considerably less promotional effort behind them.

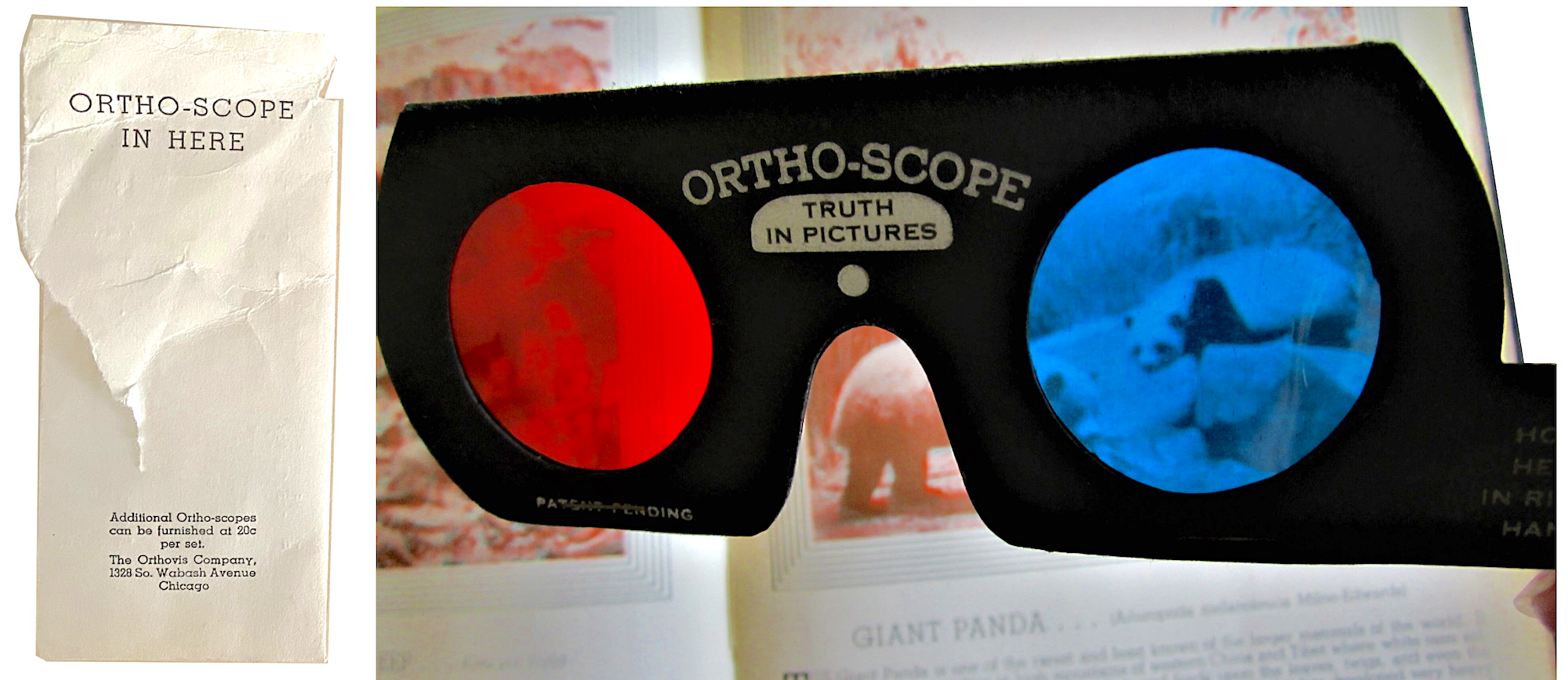

Each of the books in Orthovis’ Foot Print Series came with a free “Ortho-Scope” tucked into the inside cover. This primitive optical device—which had a “patent pending” label but doesn’t seem to have ultimately earned said patent—was arguably the primary product of the Orthovis Company; at least as essential to the enjoyment of its books as the content therein.

The Orthoscope was a handheld paper viewfinder with eye pieces made of a proto-plastic called Lumarith (a cellulose acetate material). It was a flimsy contraption, which is why the envelope it came in advertised replacement mail-order Orthoscopes for 20 cents (notably reduced to 5 cents by 1936).

The technology behind the Orthoscope combined some old 19th century tricks from stereoscopic viewers with some slightly newer innovations from the 1920s, namely the use of two color lenses—one red and one cyan/blue—to filter a single image in a manner that created a sense of depth within it.

“These pictures are not in the least like those you see in ordinary books,” reported the Lewiston Journal in Maine, one of many regional newspapers that eagerly promoted the release of The Bear and the other books in the Foot Print Series. “Two pictures are taken of the same view from two different angles, precisely as it would be seen by your two eyes. . . . These two pictures are colored, one red and one blue, and one is printed on top of the other. This accounts for the blurred effect they present in the book. Thru the scope it all clears up because the red eye picks out the red part of the picture and the blue eye picks out the blue part, and the two blend together with the effect of one outline standing out in relief against the other; which causes the appearance of depth in the pictures.”

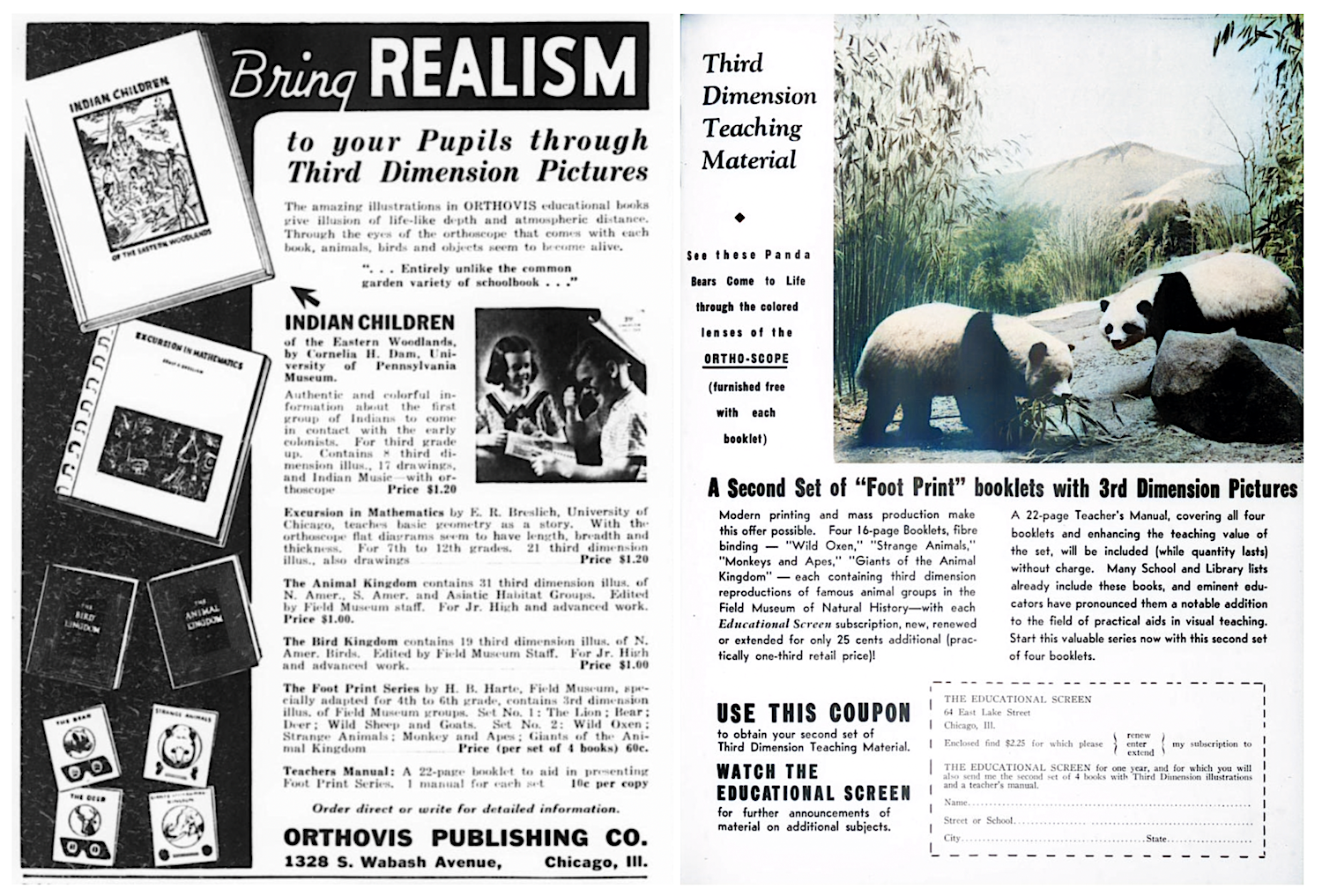

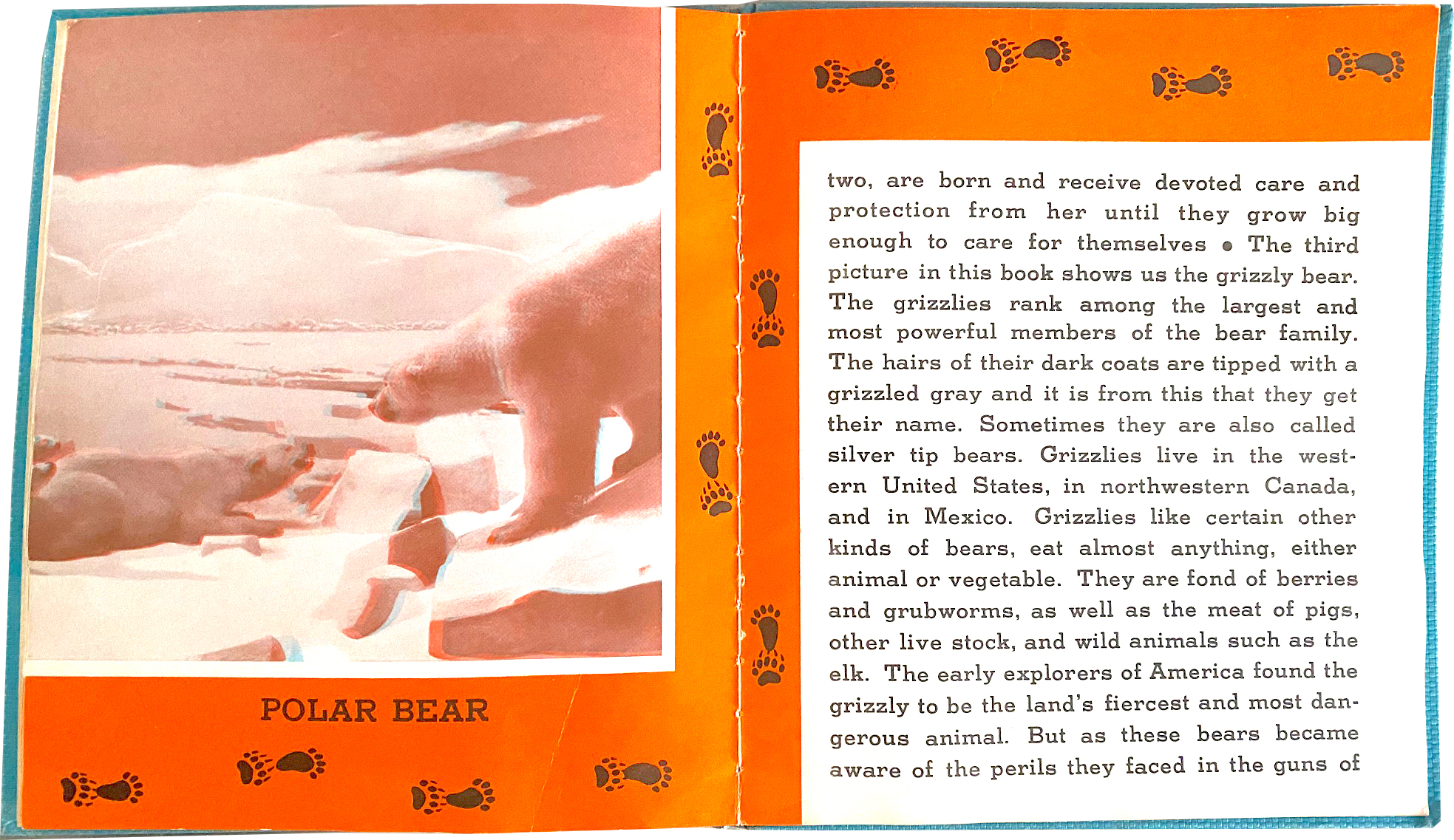

The “third dimension” effect was often compared to the experience of looking at a museum diorama, and by no coincidence, most of the images in The Bear and Orthovis’ other animal books came directly from the famous taxidermy diorama displays in the Field Museum.

[3-D images from the Orthovis book The Animal Kingdom, released during the same period as the Foot Print Series, and utilizing scenes from dioramas at Chicago’s Field Museum. Scans courtesy of taxidermy.net and the Stephen Rogers collection]

The written portions of the books, meanwhile, were handled by Field Museum staffer Horace B. Harte, a former Tribune and Daily News reporter who wound up spending the last 30 years of his life as the museum’s official public relations counsel. Since the books were aimed at kids aged about 8 to 14, it’s hard to say the copy represents the peak of pre-war nature writing, but it certainly got the job done.

“The third picture in this book shows us the grizzly bear. The grizzlies rank among the largest and most powerful members of the bear family. The hairs of their dark coats are tipped with a grizzled gray and it is from this that they get their name.”

“The third picture in this book shows us the grizzly bear. The grizzlies rank among the largest and most powerful members of the bear family. The hairs of their dark coats are tipped with a grizzled gray and it is from this that they get their name.”

That’s news to me! Consider me educated. And in 3-D no less!

The Orthovis Company continued to produce Orthoscope-aided educational books through the end of the 1930s, expanding beyond the animal kingdom with Excursion in Mathematics (by Ernest R. Breslich from the University of Chicago) and Indian Children of the Eastern Woodlands (by Cornelia H. Dam of the University of Penn Museum). These books were targeted for school curriculums and often paired with accompanying teacher’s manuals.

[The Orthovis Company was headquartered in the former Coca Cola Building at 1328 South Wabash Ave., which looks much the same today from the outside, but has been mostly converted into residential apartments on the inside]

II. A New Man

Montrose Newman, the mysterious character behind Orthovis, had done very well for himself, legitimizing his gimmicky printing enterprise through partnerships with esteemed institutions. Unfortunately, Newman’s own story is a very difficult one to track, with no visual aids—3-D or otherwise—to help us along the way.

We know that Montrose Kaufman Newman was born in New York City, that his wife’s name was Louise, and that they had no children. We also know that his birthday was March 12—it’s just the year that gets fuzzy upon inspection. On his World War I draft registration card (circa 1917), Newman’s birthdate is recorded as March 12, 1878. Later, on his World War II draft card, that date is changed to March 12, 1891, trimming his age by more than a decade. It’s the kind of inconsistency that looks more like a choice than an error.

We know that Montrose Kaufman Newman was born in New York City, that his wife’s name was Louise, and that they had no children. We also know that his birthday was March 12—it’s just the year that gets fuzzy upon inspection. On his World War I draft registration card (circa 1917), Newman’s birthdate is recorded as March 12, 1878. Later, on his World War II draft card, that date is changed to March 12, 1891, trimming his age by more than a decade. It’s the kind of inconsistency that looks more like a choice than an error.

Newman relocated from New York to Evanston, Illinois, with his wife around 1930, when he was either in his early 40s or early 50s. From the looks of it, the move was something of a life reset after a strange and varied career that had seen him travel the country as a salesman, a “sanitation expert,” an advertising man, and a minor film executive with the Audio Cinema Studio of Long Island—where he helped oversee the production of some early children’s cartoons.

While quite conservative in his views on morality and patriotism, Newman still seemed to base a lot of his work on bettering society through modernized approaches.

After the Orthovis Company folded in the early 1940s—likely due to waning interest in the magical orthoscope—Newman re-emerged in 1946 as the manager of a new Chicago publishing house called the Children’s Press, Inc., which was located at Throop and Monroe Street and financed by one of the city’s printing giants, the Regensteiner Corp.

[Several early offerings from the Children’s Press, Inc., a subsidiary of the Regensteiner Corp., founded in 1946. Montrose Newman served as VP and manager of the firm after the demise of Orthovis.]

“Montrose Newman, manager, has been identified with the production of juvenile books for the past 14 years and has placed before the public such successes as Justin Morgan Had a Horse,” the Tribune reported at the time.

“It is not our purpose to enter the field as merely another publisher of children’s books,” Newman announced. “Rather is it our plan to develop and produce books specifically for the present-day child whose alertness, thru the movies, radio, and other modern educational media, is amazingly advanced over the child of, say, 10 or 20 years ago.”

One of the first books published by the Children’s Press was Adventure Begins at Home (1946); a story written by the company’s editor-in-chief Margaret Friskey, but illustrated with 25 original paintings by a diverse group of child artists—with the intent of “broadening the reader’s understanding of boys and girls of different racial and religious backgrounds.” All royalties of the book supposedly went to an art scholarship fund.

One of the first books published by the Children’s Press was Adventure Begins at Home (1946); a story written by the company’s editor-in-chief Margaret Friskey, but illustrated with 25 original paintings by a diverse group of child artists—with the intent of “broadening the reader’s understanding of boys and girls of different racial and religious backgrounds.” All royalties of the book supposedly went to an art scholarship fund.

A year later, the Children’s Press published You and the United Nations, which Montrose Newman called an “important book” in a time of growing post-war tensions with the Soviet Union. “It is education in its broadest sense, where the ultimate security of the world depends on the children growing up in it.”

And indeed, most of the material Montrose Newman would champion for the remainder of his life—including his own numerous letters to the editor of the Chicago Tribune—showcase a fellow highly concerned about America’s future and, in particular, the Red Menace framed by the concurrent age of McCarthyism.

“Why must we wait for our GIs to be captured before using our best weapon against the godless ideology of communism—education?” Newman wrote in a letter to the Tribune in 1954. “Is it not feasible that, with a better understanding of his own government and the meaning and value of his American heritage, a young man can face up to patent lies and indoctrination of his captors? The time to use this weapon is not when the GI is in a position to be captured, but when he is still in his formative years. The privilege of living in this citadel of freedom must be made crystal clear to him.”

[You and the Constitution of the United States, by Northwestern University professor Paul Witty, was first published by the Children’s Press in 1948. Montrose Newman continued to publish new editions under his own Montrose Newman Co. into the 1950s]

During the 1950s, by no coincidence, Newman launched his own publishing house, the Montrose Newman Company (109 N. Dearborn St.), to focus on patriotic, civics-based lessons for flag waving American classrooms to utilize.

For all his noble messaging, though, there remain some peculiar blips in Montrose Newman’s own biography. In one instance early in his sales career, for example, he was accused of endorsing and cashing checks from a client—intended for his employer—and essentially running off with the money. When he re-emerged shortly thereafter as a disinfectants salesman in the 1910s (for the West Disinfecting Co. of New York), he began presenting himself as a sort of self-anointed guru on sanitation, touring schools up and down the West Coast and assessing their janitorial performance, despite having no official qualifications or authorized position in that field.

And while the altering of his birthdate is certainly forgivable, we are left with another mystery when it comes to Montrose Newman’s eventual date of death. Louise E. Newman, his wife, was recognized with an obituary in the Tribune upon her death in 1957—where it was noted that she had been living at 837 Mulford Street in Evanston and was the beloved wife of the “late Montrose Newman.” As of yet, however, we’ve been unable to find an obit or any form of death certificate or burial listing for Montrose Newman himself. We only know that he was still sending letters to the Tribune as late as 1955, so must have met his end around 1956. . . aged somewhere between 65 and 78.

And while the altering of his birthdate is certainly forgivable, we are left with another mystery when it comes to Montrose Newman’s eventual date of death. Louise E. Newman, his wife, was recognized with an obituary in the Tribune upon her death in 1957—where it was noted that she had been living at 837 Mulford Street in Evanston and was the beloved wife of the “late Montrose Newman.” As of yet, however, we’ve been unable to find an obit or any form of death certificate or burial listing for Montrose Newman himself. We only know that he was still sending letters to the Tribune as late as 1955, so must have met his end around 1956. . . aged somewhere between 65 and 78.

Perhaps Montrose Newman was merely an imperfect perfectionist, caught up in the nobility of his work like the TV chef in The Bear, and ultimately overlooked in the end, like a blurry picture seen without the clarifying lenses of a trusty orthoscope.

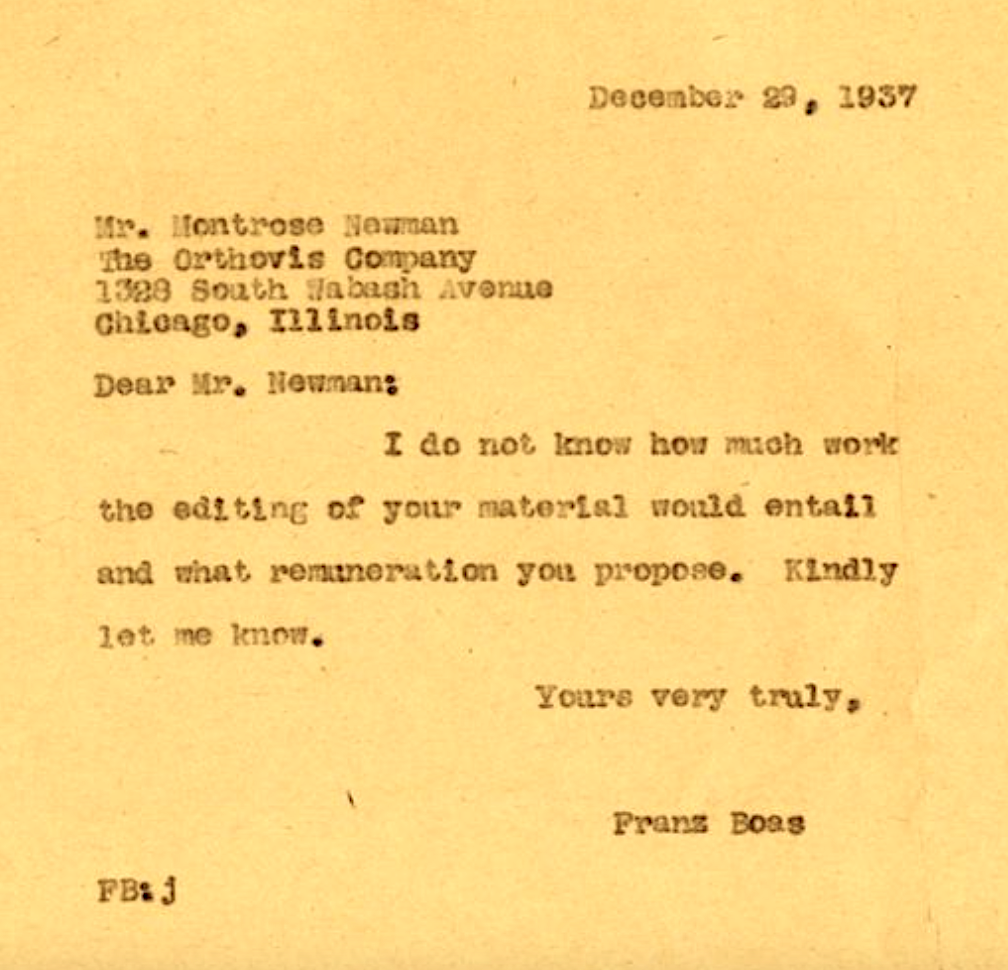

[A 1937 letter from the famed anthropologist Franz Boas to Montrose Newman, suggesting Newman had boldly recruited Boas to work on editing materials for the Orthovis Company. It doesn’t this seem arrangement was ever worked out.]

Sources:

“Sanitary Science: Its Application to Schools,” by Montrose Newman, Morning Register (Eugene, OR), Aug 29, 1911

“Eyeglasses Go With This Book” – Sun-Journal (Lewiston, Maine), June 23, 1934

“Four More Animal Books Published for Children” – Field Museum News, October 1935

“Children’s Book Week” – Evening Star (Wash DC), Nov 10, 1946

“From the Publishers” – Miami News, April 6, 1947

“Brainwashing Defense” (Letter by Montrose Newman) – Chicago Tribune, Sept 30, 1954

Louise Newman (obit) – Chicago Tribune, May 30, 1957

Horace B. Harte (obit) – Field Museum News – February 1960