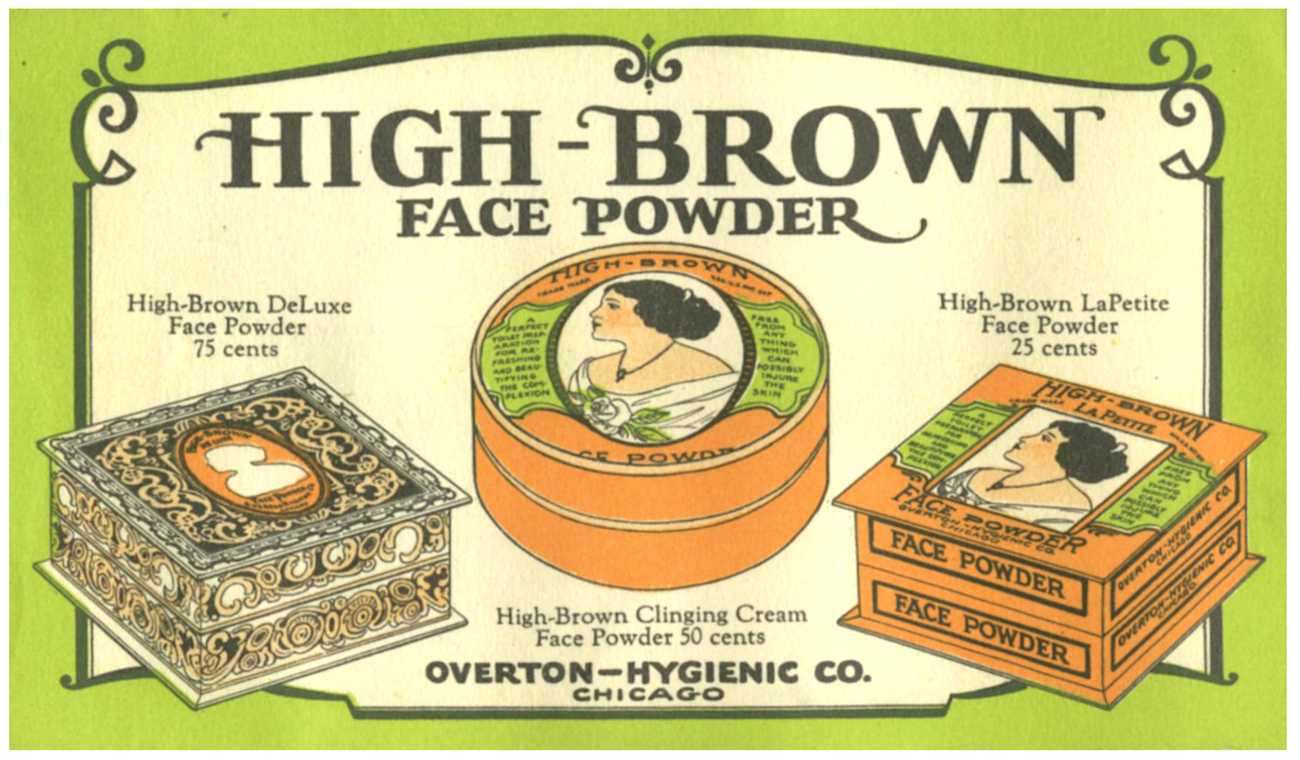

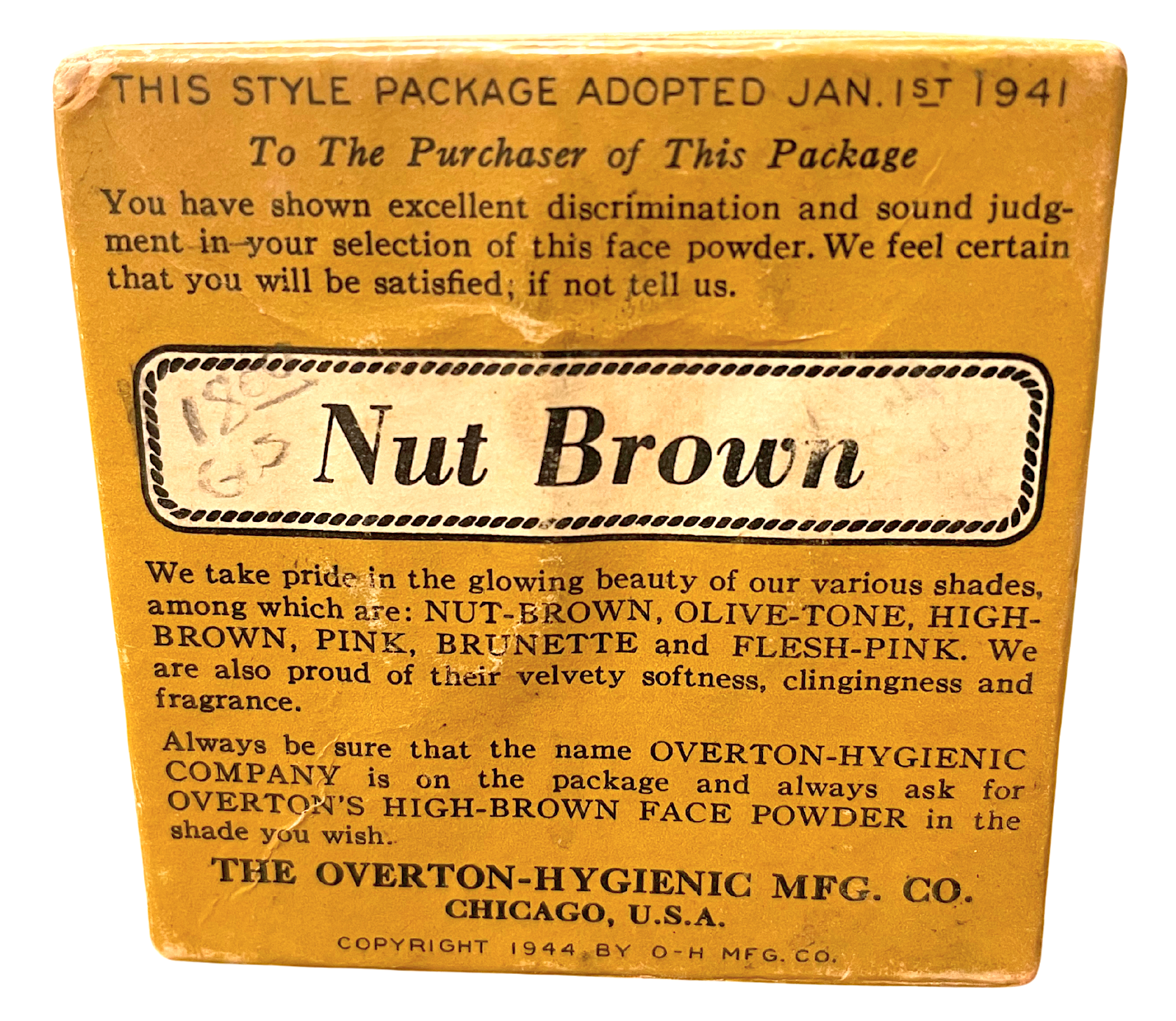

Museum Artifact: Overton’s High Brown Face Powder, 1944

Made By: The Overton-Hygienic Manufacturing Company, 3621 S. State Street, Chicago, IL [Bronzeville]

“High-Brown Face Powder clings so closely and matches the skin so perfectly that no one ever suspects the powder is there. The quality is rare, the perfume rich and fragrant. . . . Every known facility and method for the manufacture of face powder are employed so as to yield the famous High Brown quality demanded by the ‘lady who knows.’” —Overton Hygienic MFG Co. advertisement, 1921

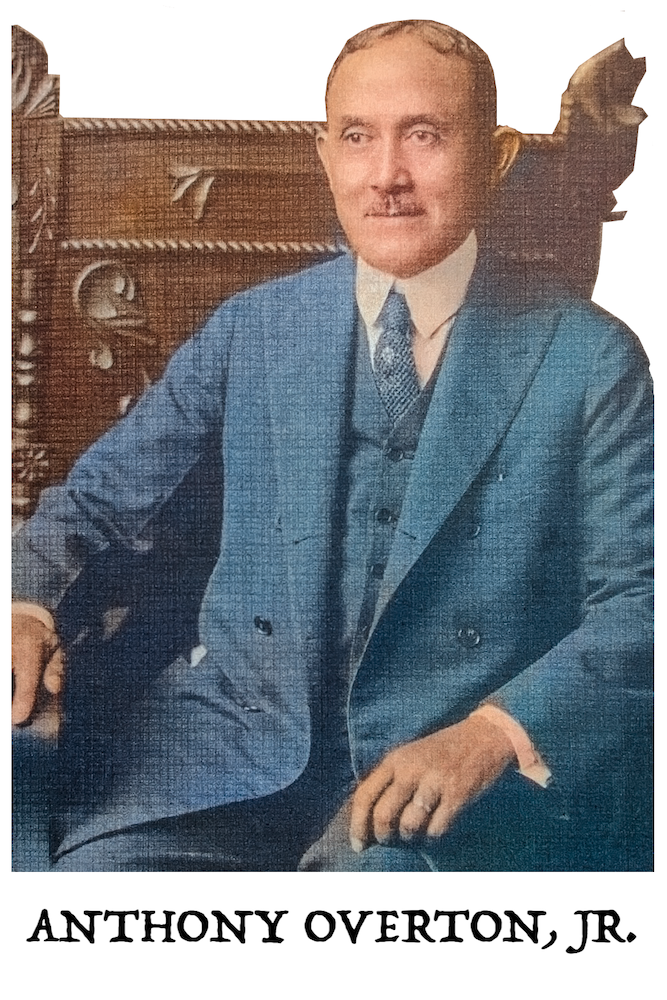

Anthony Overton, Jr., was one of Chicago’s most influential businessmen and one of the best known African-American business owners in America during the early 20th century. As a manufacturer, banking executive, and newspaper publisher, he was in many ways the living embodiment of the thriving Bronzeville neighborhood, where his companies employed hundreds of black men and women in jobs that were often wholly unavailable to them elsewhere in the city. And that’s a key point. Telling the story of Overton’s success can sometimes run the risk of metaphorically “powdering over” the glaring racial disharmony that always undermined his more idealistic vision.

Anthony Overton, Jr., was one of Chicago’s most influential businessmen and one of the best known African-American business owners in America during the early 20th century. As a manufacturer, banking executive, and newspaper publisher, he was in many ways the living embodiment of the thriving Bronzeville neighborhood, where his companies employed hundreds of black men and women in jobs that were often wholly unavailable to them elsewhere in the city. And that’s a key point. Telling the story of Overton’s success can sometimes run the risk of metaphorically “powdering over” the glaring racial disharmony that always undermined his more idealistic vision.

In the years between Overton’s arrival in Chicago (1911) and the opening of the Overton-Hygienic Manufacturing Company’s landmark factory building at 3619 S. State Street (1923), Bronzeville had become something of a pocket of utopia inside a powder keg. The “Great Migration” of African-Americans from the southern states was helping to build a vibrant, self-sustaining community here, but a concurrent new wave of hate-stirring propaganda in the media (exemplified by the blockbuster 1915 film The Birth of a Nation) was also creating an upswing in racially motivated violence against the city’s black citizens. There was no worse example than the horrific Chicago Race Riot of 1919, when at least 38 people were killed and thousands lost their homes, mostly on the South Side.

As the son of enslaved parents, Anthony Overton was hardly ignorant to these injustices and atrocities, but like so many other ambitious arrivals to Chicago, he was also hopeful that new opportunities would inevitably bring progress. On the way to becoming a self-made millionaire, he proved as shrewd and driven as any of his white counterparts in the downtown skyscrapers; most of whom would never welcome him into their billiard rooms, let alone boardrooms.

One-hundred years later, Overton remains a disappointingly obscure character, even as the city has made substantial strides in celebrating and commemorating many of its seminal African-American figures. Some of that lack of recognition, admittedly, is due to the relative absence of surviving personal records from Overton’s life and businesses—as well as the occasional misinformation he personally helped perpetuate about both. More than that, though, there might also be a subtle hesitance to celebrate a man who essentially made his fortune selling “cheap cosmetics.”

When you know the full story of the Overton-Hygienic MFG Company and its importance to thousands of women who never had access to these types of products before, however, it’s hard to see it as anything other than a noble legacy—every bit as significant as Overton’s more celebrated work with the Chicago Bee newspaper or Douglass National Bank.

[1931 advertisement for Overton’s High Brown Face Powder]

History of the Overton-Hygienic MFG Co., Part I: Topeka

As is sadly the case with countless important figures in African-American history, tracing the early life of Anthony Overton—and particularly the lives of his parents—is a challenging endeavor. Enslaved men and women were rarely granted the careful consideration of census takers and record keepers, and as such, many of their stories are permanently lost to time. The fact that we even know as much as we do about the Overtons is a testament to how much they achieved in the years after the Civil War, long before young Anthony Jr. ever sold his first box of face powder.

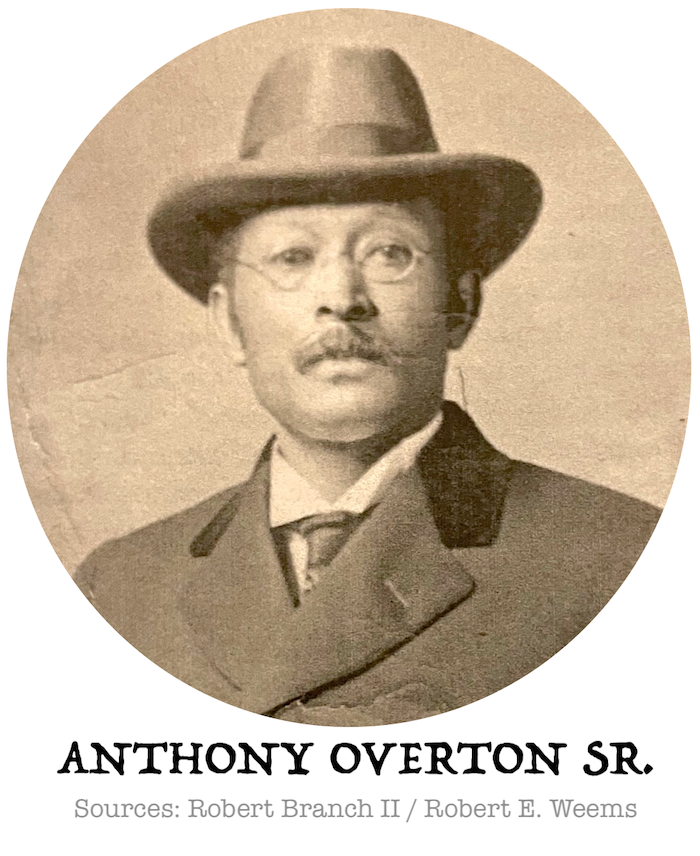

His parents, Antoine “Anthony” Overton, Sr., and Martha Deberry Overton, were both born into slavery in the 1820s, and spent most of the Civil War on a plantation in Monroe, Louisiana, starting a young family in a time of unimaginable tumult. While they were in the heart of Confederate territory, the plantation happened to be owned by an ex-Northerner with Union sympathies and a relatively “progressive” mindset. This dynamic put Overton, Sr., in some unique situations during the war, discussing politics with his “master” and sometimes helping him covertly assist the Union’s cause by thwarting the efforts of local Rebel troops.

His parents, Antoine “Anthony” Overton, Sr., and Martha Deberry Overton, were both born into slavery in the 1820s, and spent most of the Civil War on a plantation in Monroe, Louisiana, starting a young family in a time of unimaginable tumult. While they were in the heart of Confederate territory, the plantation happened to be owned by an ex-Northerner with Union sympathies and a relatively “progressive” mindset. This dynamic put Overton, Sr., in some unique situations during the war, discussing politics with his “master” and sometimes helping him covertly assist the Union’s cause by thwarting the efforts of local Rebel troops.

After the war, Overton, Sr. quickly developed a reputation for his own leadership and entrepreneurial skills as a free man. He ran a general store in Monroe, helped establish the first school for African-Americans in the region, and—most impressive of all—was elected to the Louisiana state legislature in 1871.

By that point, Overton’s son, Anthony Overton, Jr., was about 7 years old. And thus, from an early age, he was given a very different vision of what a black man could achieve in America compared to any generation prior.

[Kansas Avenue in the town of Topeka, KS, c. 1880 (colorized) – courtesy of Kansas State Historical Society]

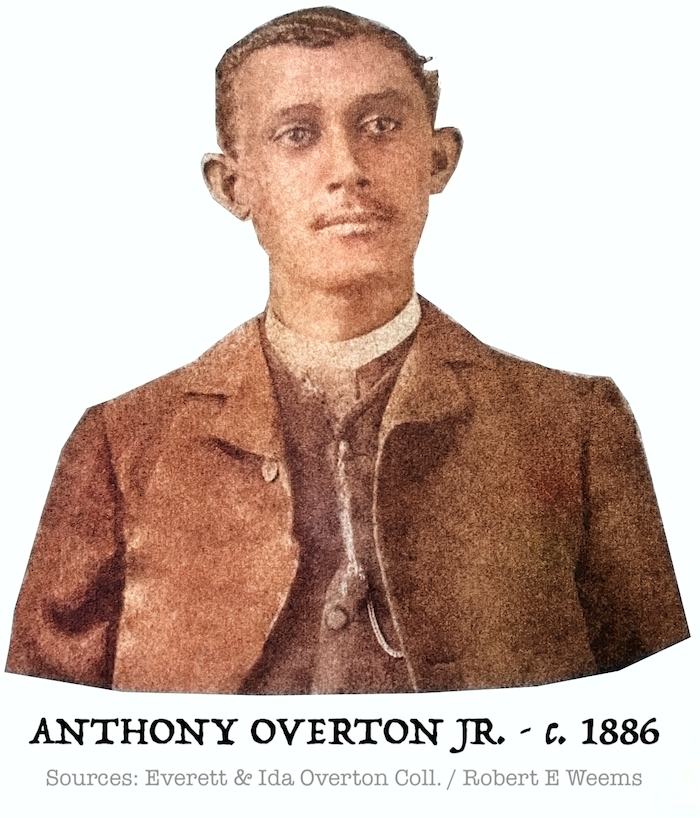

By 1880, the Overton family had relocated to Topeka, Kansas, and while the next few years would be critical to establishing Anthony Jr.’s trajectory into success as an adult, the actual details of those experiences have also become significantly blurred, thanks in large part to Anthony Jr.’s own inconsistent memory and/or propensity for creative embellishment.

In one version of events, Overton Jr. recalled developing his business acumen by running a profitable fruit stand as a teenager; in another, he said he quit school altogether to become a Pullman porter. The way Overton described the next stage of his career is also dubious, as he often claimed to have both (a) earned a law degree from the University of Kansas and (b) served as a municipal judge in Topeka.

Thanks to more recent research by author and historian Robert E. Weems for his 2020 Overton biography, The Merchant Prince of Black Chicago, we know that there are merely threads of truth to these tales, with much of the substantive stuff easily debunked. For example, Anthony’s older brother Mack Wilson ran a successful grocery business in Topeka, and Anthony himself was, in fact, a student at both the University of Kansas (in Lawrence, KS) and Washburn College (Topeka) in the late 1880s. However, Weems could find no evidence—nor any reasonable likelihood—that Anthony Overton ever graduated with a law degree or joined the Kansas Bar Association, let alone reached the level of judge.

Thanks to more recent research by author and historian Robert E. Weems for his 2020 Overton biography, The Merchant Prince of Black Chicago, we know that there are merely threads of truth to these tales, with much of the substantive stuff easily debunked. For example, Anthony’s older brother Mack Wilson ran a successful grocery business in Topeka, and Anthony himself was, in fact, a student at both the University of Kansas (in Lawrence, KS) and Washburn College (Topeka) in the late 1880s. However, Weems could find no evidence—nor any reasonable likelihood—that Anthony Overton ever graduated with a law degree or joined the Kansas Bar Association, let alone reached the level of judge.

Weems found similar problems with oft-repeated accounts of Overton’s time in Oklahoma during the 1890s land rush, when he supposedly became the “leading citizen of the town” of Wanamaker, OK. Instead, actual records from the period suggest that both the upstart town of Wanamaker and Overton’s young career had hit major stumbling blocks during those years, including Anthony’s failed attempt to become the treasurer of Kingfisher County (he was the only Republican candidate in the county to lose his race in the 1892 election).

Once he entered the public eye, it seems like Overton felt the need to rewrite his early history in order to substantiate the “legitimacy” of his later success. But, from a modern perspective, his real-life struggles only enhance the story, as his resilience led directly to the creation of the business that built his empire.

II. Kansas City

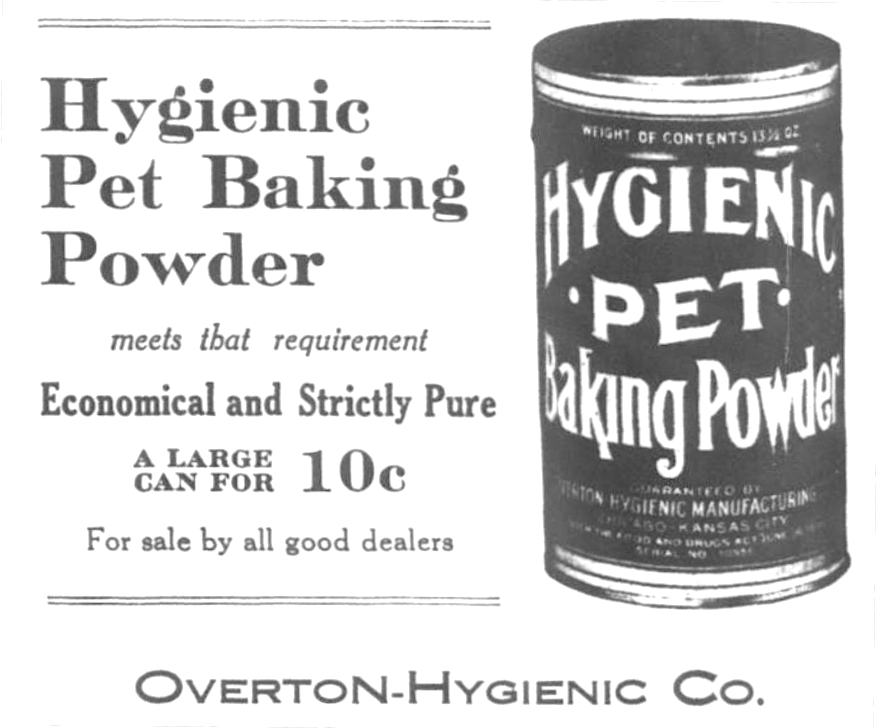

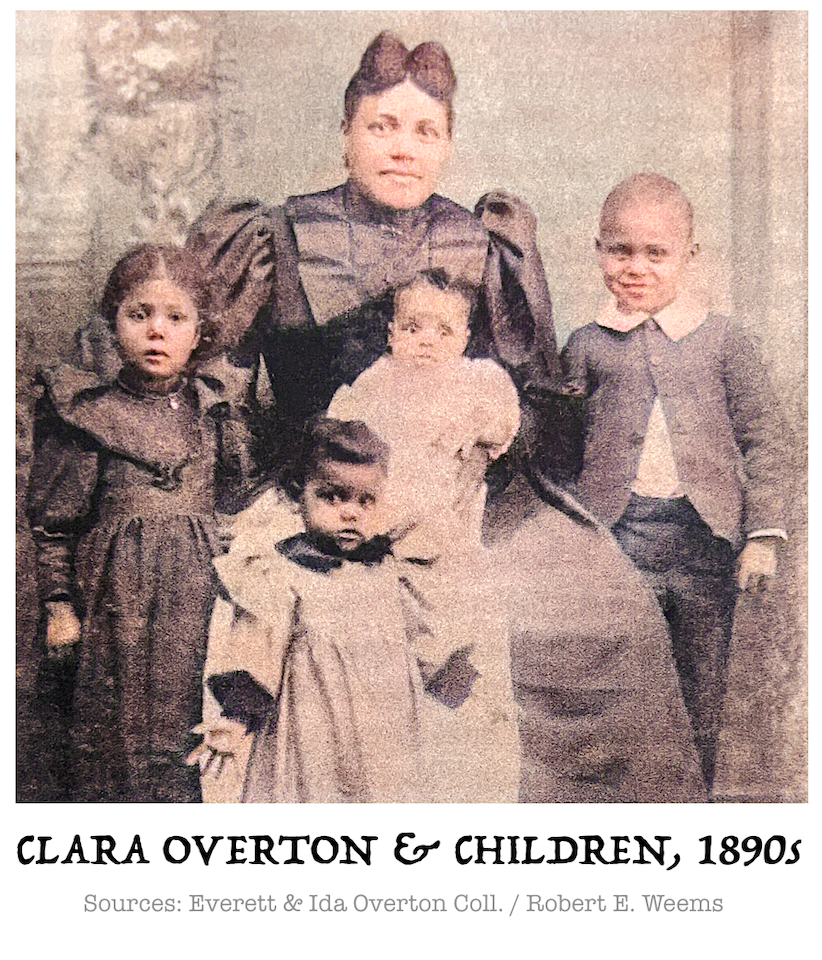

After his failures in Oklahoma, Overton and his new wife Clara settled in Kansas City, where they raised their four children through the 1890s into the new century. Here, Anthony tried his hand at the mercantile trade once more, and slowly built a steady enterprise. By 1898, he’d earned enough capital to start producing a few grocery items under his own Overton brand name, starting with a line of baking powder. This is how the Overton Hygienic Manufacturing Company was born.

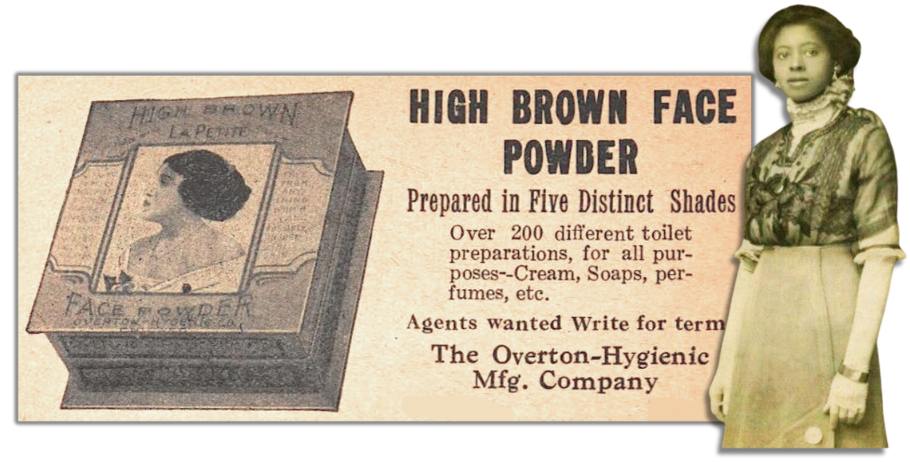

According to Weems’ research in The Merchant Prince of Black Chicago, the launch of the manufacturing business revealed Overton’s “uncanny ability to determine and influence consumer wants and desires.” Around 1900, with his baking powder already selling well, he “quickly realized there was a potentially bigger market for face powder that complimented and enhanced the complexions of African American women.” This led to the introduction of Overton’s “High Brown” face powder, followed soon by a whole line-up of related cosmetics.

According to Weems’ research in The Merchant Prince of Black Chicago, the launch of the manufacturing business revealed Overton’s “uncanny ability to determine and influence consumer wants and desires.” Around 1900, with his baking powder already selling well, he “quickly realized there was a potentially bigger market for face powder that complimented and enhanced the complexions of African American women.” This led to the introduction of Overton’s “High Brown” face powder, followed soon by a whole line-up of related cosmetics.

While Overton’s entire sales team only consisted of three men at this point, word spread fast, and for good reason. Up until this point, women of color in America had no choice but to make do with cosmetics decidedly not produced with their skin tones in mind. The significance and novelty of a new alternative is hard to overstate.

“The use of face powders made by white concerns for the white woman,” read one early High Brown Face Powder advertisement, “make you look as if you had fallen into a flour barrel. . . . [High Brown] is the first and only face powder that was ever made especially for the complexion of colored ladies.”

Of course, even with a pioneering product, some exclusionary ideas persisted, as the very term “high brown” itself was often used specifically to describe light-skinned or mulatto African Americans. Anthony and Clara Overton fit under this description themselves, and the Overton cosmetic lines undoubtedly served this type of complexion better than they did those with darker skin tones. Nonetheless, the general response was enthusiastic, as a whole new industry had suddenly emerged into what had once been a frustrating void.

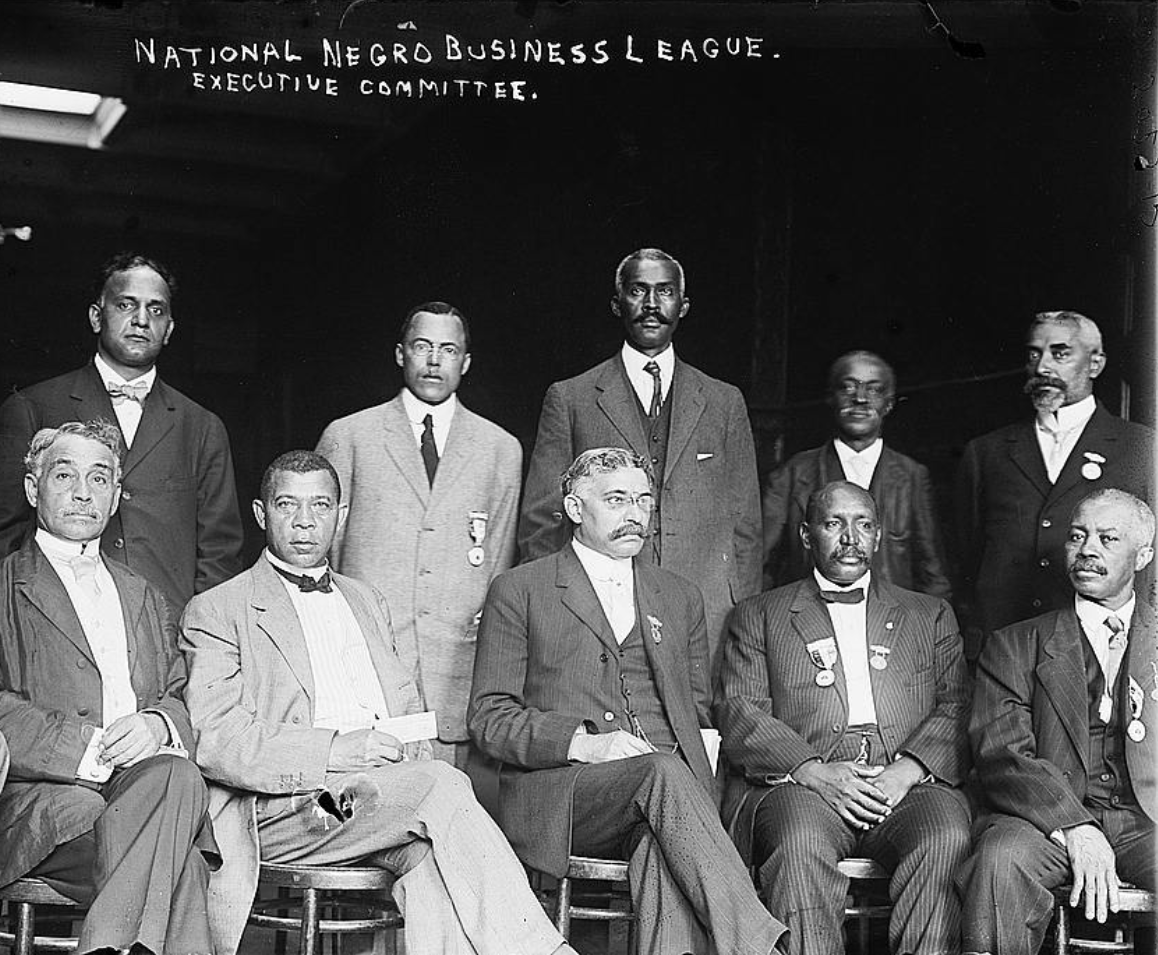

Finally—with no fiction or embellishment required—Anthony Overton, Jr. had become a success, as the High Brown line rapidly gained devotees well beyond Kansas City. The timing was also excellent, as Overton’s newfound fame coincided with the emergence of Booker T. Washington’s new National Negro Business League in 1900. As such, Overton started a regular correspondence with Washington, and was even invited to speak at the NNBL’s 1901 conference, where he shared his trademark optimism with an impressed audience.

“While there is no denying the fact that the negro is subject to some disadvantages on account of race prejudice,” he said, “I am pleased to state, from personal experience as a salesman, I can attribute the failure to make a sale in very few instances to this cause alone.”

“While there is no denying the fact that the negro is subject to some disadvantages on account of race prejudice,” he said, “I am pleased to state, from personal experience as a salesman, I can attribute the failure to make a sale in very few instances to this cause alone.”

Whether out of bold self belief or a necessary sense of denial, Overton often downplayed the role of racism throughout his career. Any obstacle, it seems, was just there to be overcome by the person willing to lead the way.

This attitude was evident in a letter Overton wrote to Booker T. Washington in 1904, after severe flooding had shut down his Kansas City factory and threatened the future of his business. “Adversities sometimes tend to make a man of one,” he wrote. “Within another six months, we will be doing a larger and better business than before.”

After another six years, however, Overton’s family-run business was still struggling to stay profitable, as the costs of manufacturing, sales, and shipping—with a limited workforce—was undermining the potential of Overton Hygienic’s products. The only logical move, of course, was a move to America’s superior industrial hub. And so, in 1911, the Overtons made their way to Chicago.

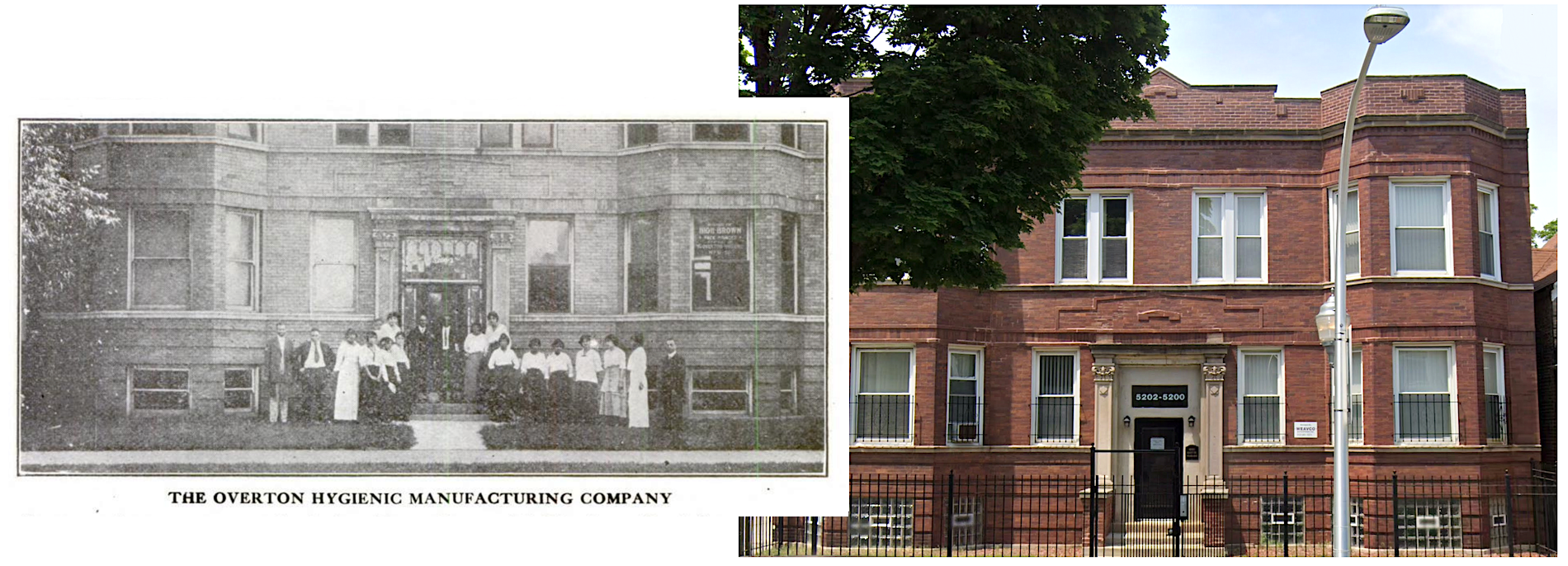

[Then and Now: The original Chicago headquarters of the Overton-Hygienic MFG Co. at 5200 S. Wabash Ave., as seen in 1915 and 2023]

III. Chicago

Anthony Overton’s first full year in Chicago was a whirlwind of devastating losses and galvanizing triumphs, starting with the death of his wife Clara in July of 1912 at just 45 years of age (the cause seems to have been some combination of heart disease and Bright’s disease). The Overtons had four children entering higher education at the time, but Clara was more than a matriarch; she had also been actively involved in the development of the Overton-Hygienic product line; perhaps even the brains behind it.

“She [Clara] is a thorough business woman and to her is due credit for the success of the firm,” the Topeka Plaindealer once noted after touring the Overton factory in 1911. “Although Mr. Overton is a hustler, he is not the equal of his wife when it comes to managing on the inside.”

“She [Clara] is a thorough business woman and to her is due credit for the success of the firm,” the Topeka Plaindealer once noted after touring the Overton factory in 1911. “Although Mr. Overton is a hustler, he is not the equal of his wife when it comes to managing on the inside.”

Clara Overton’s 1912 obituary in the Chicago Defender supported this view, describing her as a “prime mover of the business” who “did lots to give it the reputation it has.”

Merely a month after losing his wife and business partner, Anthony Overton found himself back at the podium in the convention of the National Negro Business League, trying to establish himself not just as a skilled “hustler,” but as one of Chicago’s new black mercantile heroes; the man who built a cosmetics business from the ground up without selling out to white interests.

“Having abiding faith in our own people,” he said in his 1912 speech, “we have conducted our business strictly as a Negro enterprise, and have none but Negroes employed in any capacity.”

[Anthony Overton (seated) with his sales team outside the Wabash Avenue offices, 1916. Colorized image. Part of the Everett & Ida Overton collection]

Rather than limiting sales opportunities, he added, this policy had actually boosted his ability to get product placement in white-owned establishments, as many white shop owners, he claimed, “appreciated the effort” of African-Americans trying to build something on their own.

Overton didn’t emphasize gender as much as race when speaking before his fellow businessmen, but his company also employed predominantly women outside of the traveling salesmen ranks, with all three Overton daughters—Eva, Mabel, and Frances—eventually following in their mother’s footsteps and taking on roles in the business.

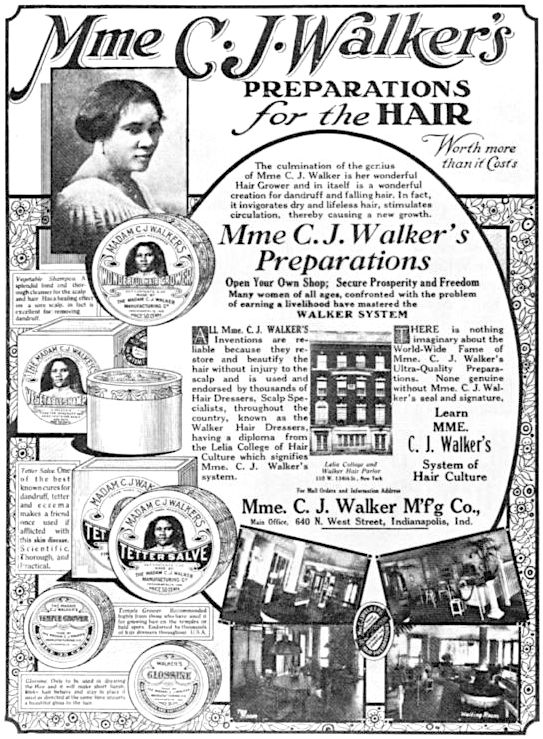

Hiring women to prepare, package, and sell cosmetics wasn’t entirely unusual for the time period (lower salary requirements was always a plus), but Overton’s use of female voices as the marketing braintrust of the operation was a bit more novel for a male-owned business; even if it was likely motivated by the rise of two hugely successful new rivals in the African-American cosmetics industry: Annie Turnbo (creator of the Poro line out of St. Louis) and Sarah Breedlove of Indianapolis, better known as Madam C. J. Walker.

Both Turnbo and Walker were on their way to becoming self-made millionaires, and both were their own best spokesmodels, using their personal understanding of make-up and hair care to build trust with their largely female clientele. Overton would have been all too aware of this phenomenon, and clearly made many of his subsequent marketing decisions with Turnbo and Walker in mind.

Both Turnbo and Walker were on their way to becoming self-made millionaires, and both were their own best spokesmodels, using their personal understanding of make-up and hair care to build trust with their largely female clientele. Overton would have been all too aware of this phenomenon, and clearly made many of his subsequent marketing decisions with Turnbo and Walker in mind.

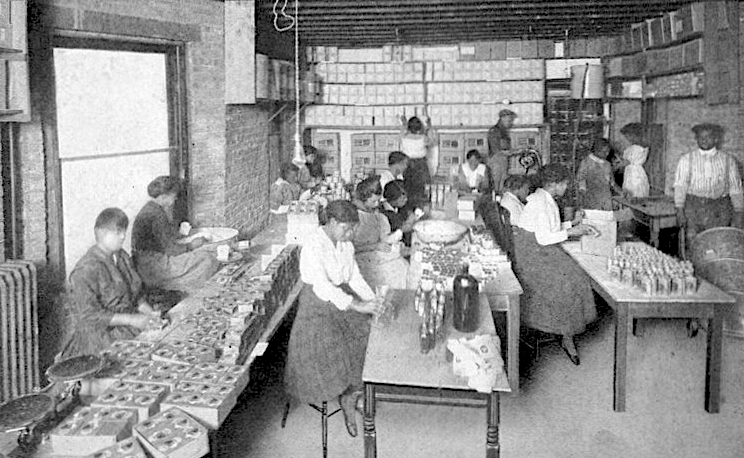

For its first decade in Chicago, the Overton-Hygienic MFG Co. was based at 5200 S. Wabash Avenue (at the south end of Bronzeville), with a branch office at 3519 S. State Street (at the north end of the neighborhood). The regular staff totaled somewhere between 35 and 45 workers. Since mainstream department stores like Marshall Field would never put African-American cosmetics on its sales floor, the Overton branch office served this purpose, employing a team of women to host demonstrations for curious visitors, introducing them to Overton’s expanding line-up of products.

“Thousands of people have become acquainted with the powders and perfumes manufactured by Mr. Overton,” the Chicago Defender reported in 1915, “and they claim his goods to be the very best on the market.” The same article encouraged readers to visit the company sales room and meet “the pretty girls who will be in charge.”

Even with helpful support from the local black media, Anthony Overton—still a skilled hustler at heart—wanted greater control of the narrative around his products. If he couldn’t be the face of his brand like Madam C. J. Walker, perhaps he could skip the advertising entirely and jump straight to the mainline of communication with his audience . . . publishing.

[Overton employees preparing packages of High Brown Face Powder and other products, 1920s. The Chicago plant supposedly shipped out as many as 4 million containers of High Brown in one year alone during the height of its popularity.]

IV. The Bronzeville Mogul

“A new man in any field, in order to deserve public consideration, must be a BENEFACTOR in some way to his community, be he minister, physician, lawyer, mechanic or merchant. If a merchant . . . he must feel it his duty to sell a superior quality of goods at the price prevailing for goods of only ordinary quality; or sell goods of a standard quality at a lower price; or make deliveries more promptly; or in some way render some additional conveniences or accommodations.” —Anthony Overton, writing under the presumed pseudonym “McAdoo Baker,” in a 1917 issue of the Half-Century Magazine

Starting in 1916 and for the decade that followed, Anthony Overton financed the publishing of The Half-Century Magazine; a title referencing the 50 years that had passed since emancipation. While there was an obvious intent to utilize the publication as a vehicle for advertising his cosmetics and other products, Overton clearly cared about the messaging and sophistication of the articles, as well, which covered culture, style, economics, and (mostly Republican) politics within the African-American community. The goal wasn’t necessarily to target a female audience only, but nonetheless, Overton maintained the strategy of putting women in key positions at the magazine and contributing his own input from the shadows—sometimes in the form of articles written under a pseudonym.

Starting in 1916 and for the decade that followed, Anthony Overton financed the publishing of The Half-Century Magazine; a title referencing the 50 years that had passed since emancipation. While there was an obvious intent to utilize the publication as a vehicle for advertising his cosmetics and other products, Overton clearly cared about the messaging and sophistication of the articles, as well, which covered culture, style, economics, and (mostly Republican) politics within the African-American community. The goal wasn’t necessarily to target a female audience only, but nonetheless, Overton maintained the strategy of putting women in key positions at the magazine and contributing his own input from the shadows—sometimes in the form of articles written under a pseudonym.

As Robert E. Weems points out in The Merchant Prince of Black Chicago, the Half-Century “sought to proactively promote the notion of African American feminine beauty” and refused to take on extra advertising revenue from any products that might reinforce dangerous stereotypes or take advantage of readers’ insecurities or gullibility (i.e. snake oil products, “get rich quick” schemes, etc.). Overton’s daughters and sons-in-law were active staff members of the magazine, and carried out the mission to produce material that empowered and celebrated the community; both for its achievements and potential. For better or worse, there was considerably less ink spilled on the boatload of rightful grievances that many of its readers would have carried with them about the state of the world. Anthony Overton, like many wealthy men before and after him, was perhaps a bit too convinced that anyone ought to be able to follow his lead; less conscious of the massive factors of circumstance and luck involved in that ask.

While the Half-Century eventually ended its run in 1925, Overton remained highly active as a newspaper publisher, starting with his affiliation with the Chicago Whip in 1919—created as a competitor of the city’s top black newspaper, the Chicago Defender—and later launching his own paper, the Chicago Bee, in 1926.

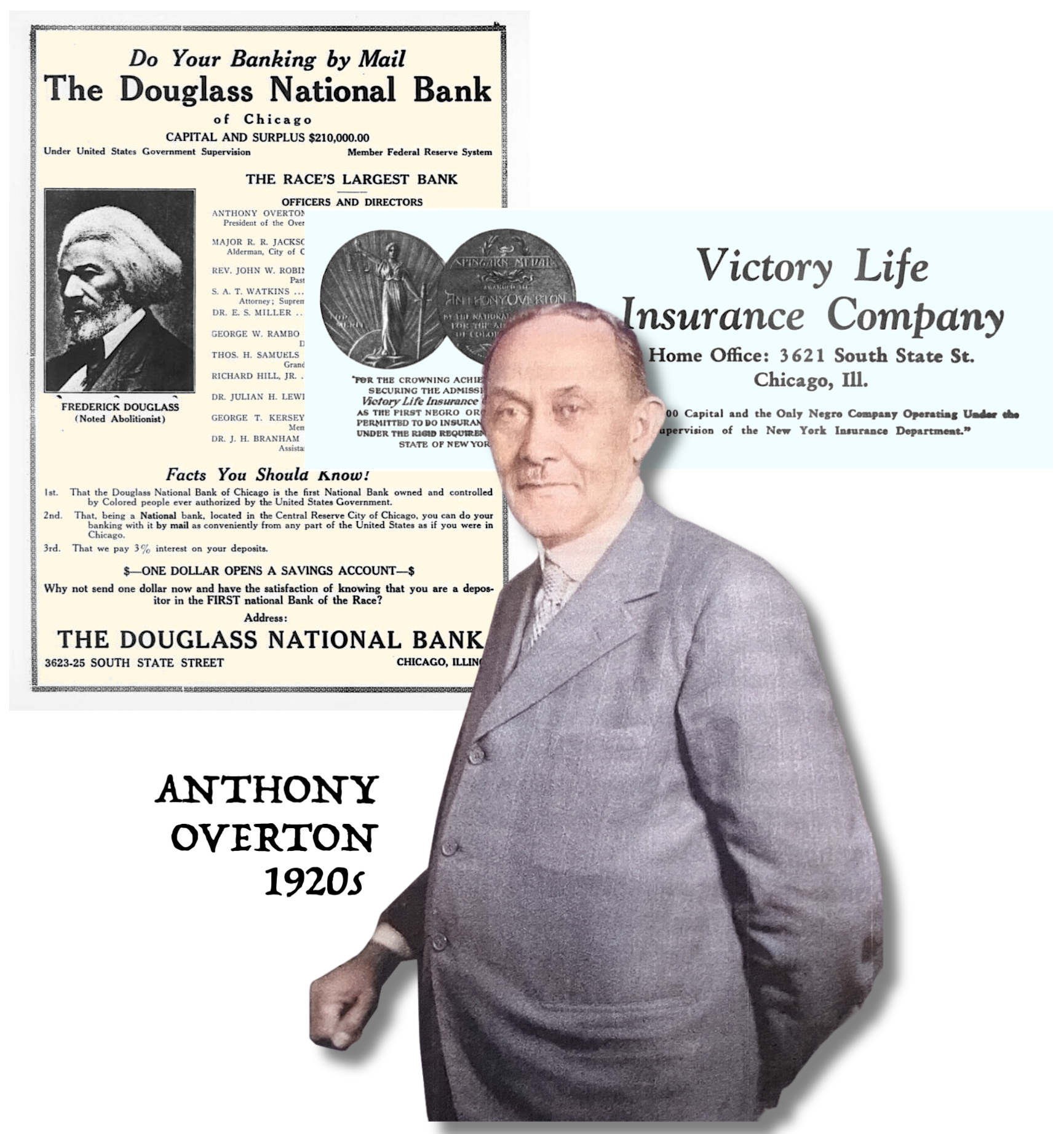

By this point, Overton and his family were at the peak of their powers. Anthony Overton, at the age of 60, was widely viewed as the most successful black business owner in America, not only as a merchandiser, but as the operator of two of the foremost black-owned financial institutions in the country: the Douglass National Bank (established in 1922) and the Victory Life Insurance Co. (1924). As the newly nicknamed neighborhood of “Bronzeville” and its “Black Metropolis” continued to build its reputation, Overton was arguably the most popular man on his local block, as well—a major employer and property owner with a squeaky clean image.

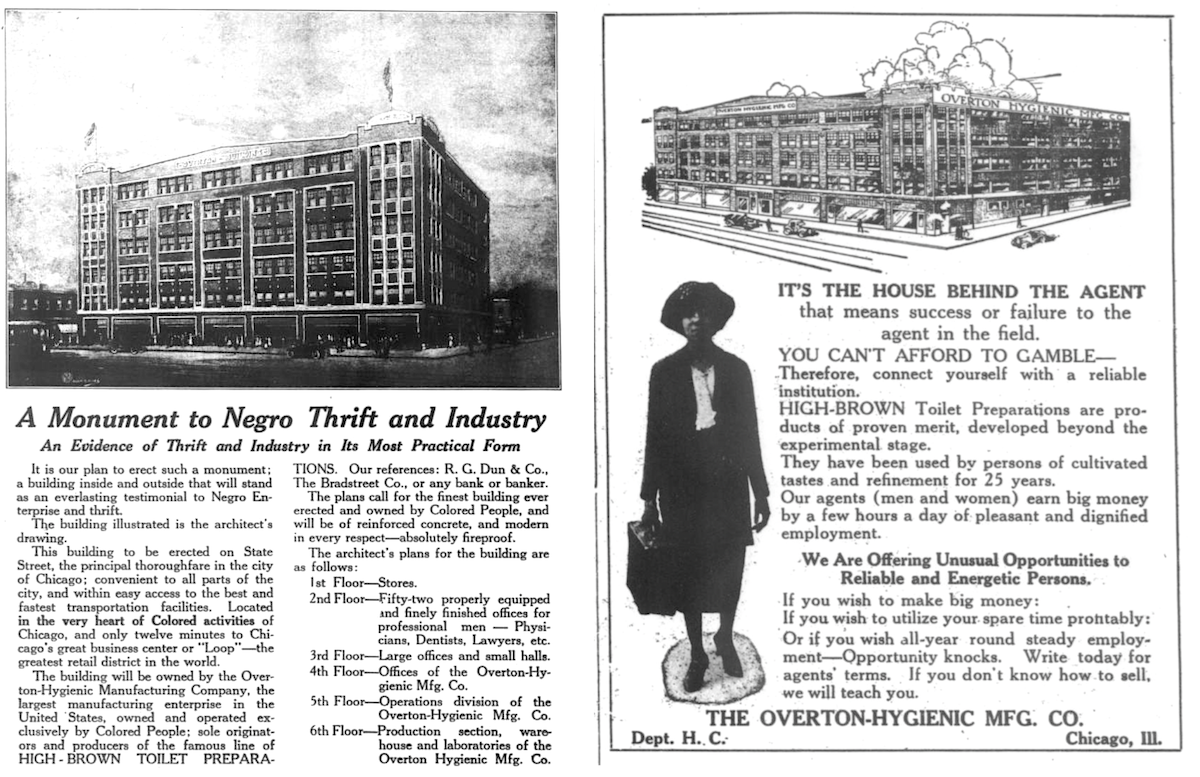

Working with architect Z. Erol Smith, he had erected the new four-story Overton-Hygienic Building in 1923, at 3619-27 South State Street, which would later be joined by the Art Deco offices of the Chicago Bee Building (3647-55 S. State Street) in 1931. The Hygienic building was famously described in the pages of the Half-Century Magazine as a “Monument to Negro Thrift and Industry . . . the finest building ever erected and owned by colored people—reinforced concrete and modern in every respect.”

Working with architect Z. Erol Smith, he had erected the new four-story Overton-Hygienic Building in 1923, at 3619-27 South State Street, which would later be joined by the Art Deco offices of the Chicago Bee Building (3647-55 S. State Street) in 1931. The Hygienic building was famously described in the pages of the Half-Century Magazine as a “Monument to Negro Thrift and Industry . . . the finest building ever erected and owned by colored people—reinforced concrete and modern in every respect.”

According to Gerald Danzer’s 1998 article Chicago’s Black Metropolis: Understanding History through a Historic Place, “each floor of this building was used for a different purpose. The cosmetics manufacturing took place on the top floor while other aspects of the business, including sales, accounting, and advertising, occupied the third floor. The second floor held the Victory Life Insurance Company as well as rental space for professional offices. The first floor housed a drug-store, the Douglass National Bank, and other commercial ventures.”

The headquarters of the Overton-Hygienic MFG Co. was a reflection of the principles of the company and the ultimate evidence of its remarkable success.

[Top Left: Postcard of the Overton-Hygienic Building / Douglass Bank Building, 1928. Top Right: The same building, recently renovated, at 3619-3627 S. State St. Bottom Left: Preserved Overton sign at the top of the building. Bottom Right: Workers inside the cosmetics production area in the upper floor of the building, 1920s.]

“In twenty-five years this business has grown from a small, one-room shop to one of the finest concerns in the world for the production of toilet articles,” the Half-Century noted in a 1923 ad/article. “Today this is a national institution, with its agencies and customers dotting the country from coast to coast. The reasons for this remarkable growth are not hard to find. The Overton-Hygienic Co. has given service and made HIGH-BROWN Toilet Preparations superior in quality.

“. . . They have spared no expense in putting out attractive packages. They have put honesty and skill into every preparation offered to the public. They are a firm of proven dependability and high character, marketing nothing but reliable merchandise.”

“. . . They have spared no expense in putting out attractive packages. They have put honesty and skill into every preparation offered to the public. They are a firm of proven dependability and high character, marketing nothing but reliable merchandise.”

Anthony Overton was now in the award-collecting phase of his career, voted the “outstanding Negro business executive in the United States” for 1926, and receiving both the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal for outstanding achievement and the Harmon Foundation Gold Medal for business in 1927.

Incidentally, the number one box office movie of 1927 was The Jazz Singer—one of the first “talking pictures,” in which the white singer Al Jolsen spends much of the film in blackface. Anthony Overton’s vision of African-American excellence and equality was still a long way from taking root in the mainstream.

V. It Ain’t Overton ‘Til It’s Overton

In the storybook version of Anthony Overton’s life, the 1930s should have seen him ride off into the sunset of retirement, leaving his growing empire to the next generation. Instead, as it was for no shortage of business owners from all racial and ethnic backgrounds, this decade cruelly pulled the rug out from many of his hard-earned accomplishments and cast a harsh light on some of his previously unseen missteps and misdeeds.

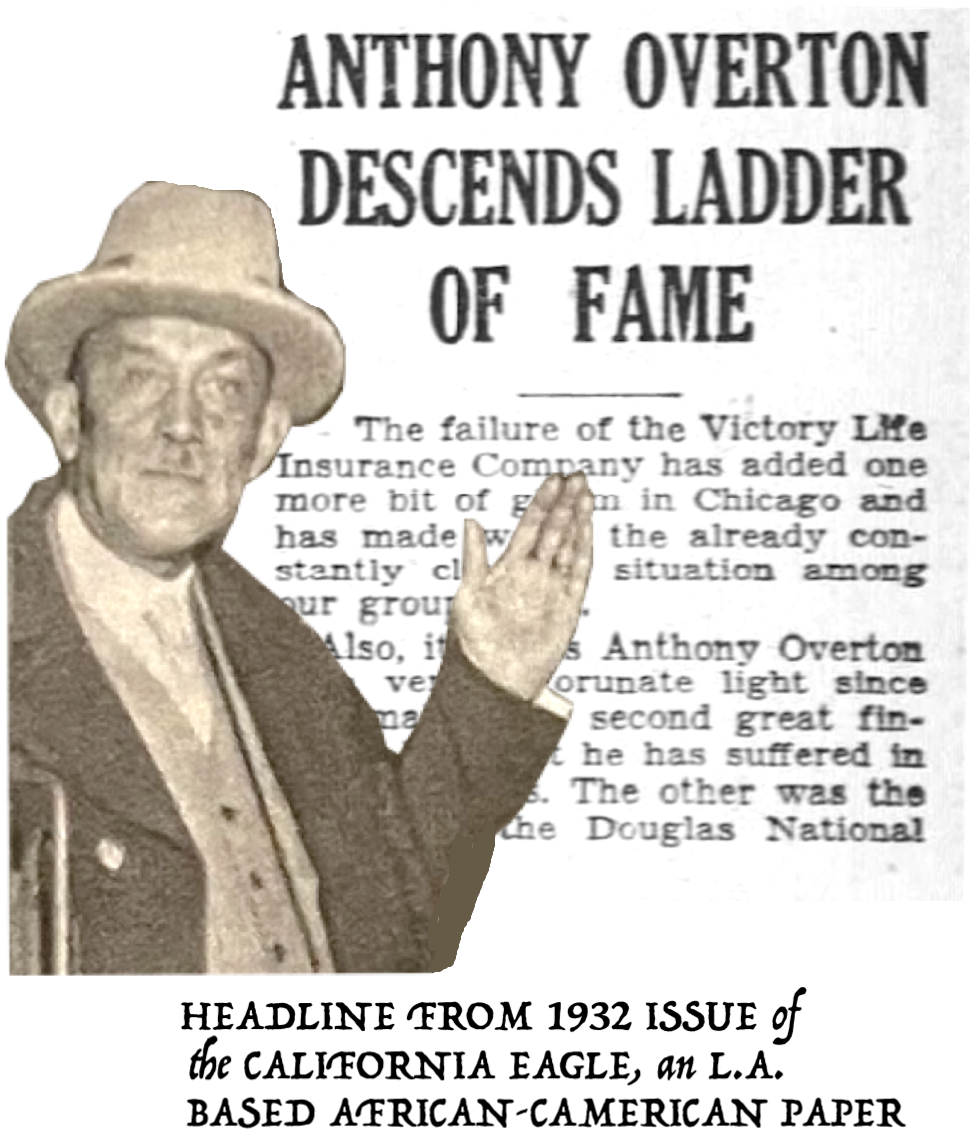

Without getting too far into the weeds, much of the evidence that came to light after the stock market crash of 1929 pointed to considerable mismanagement of both the Douglass National Bank and Victory Life Insurance Co., with Anthony Overton funneling stock from one into the other and setting up questionable real estate and advisory contracts that routinely benefitted himself and his family. Overton’s once sparkling reputation took a pummeling, especially after he was ousted from the Victory board and then forced to shut down the Douglass Bank.

Without getting too far into the weeds, much of the evidence that came to light after the stock market crash of 1929 pointed to considerable mismanagement of both the Douglass National Bank and Victory Life Insurance Co., with Anthony Overton funneling stock from one into the other and setting up questionable real estate and advisory contracts that routinely benefitted himself and his family. Overton’s once sparkling reputation took a pummeling, especially after he was ousted from the Victory board and then forced to shut down the Douglass Bank.

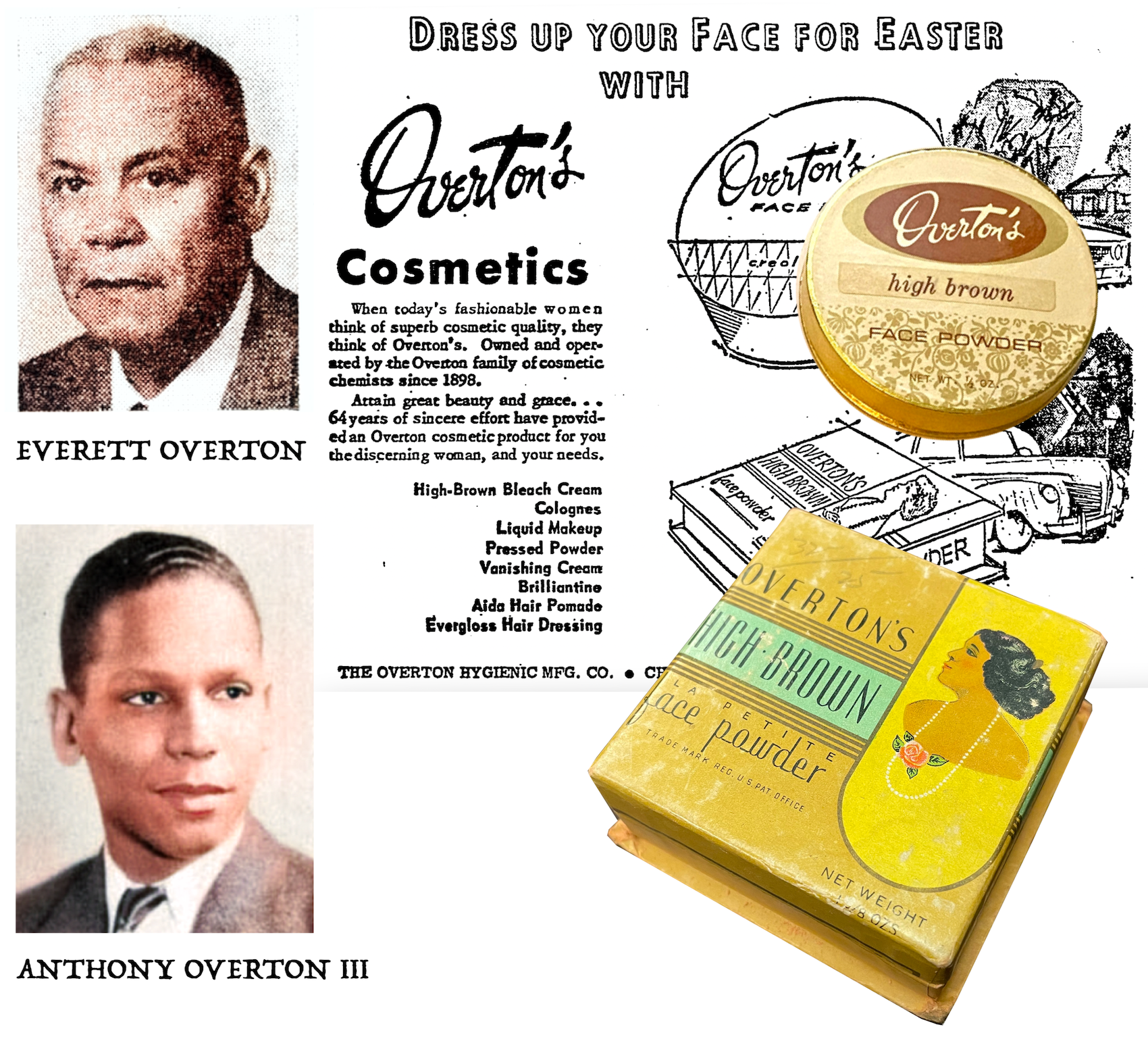

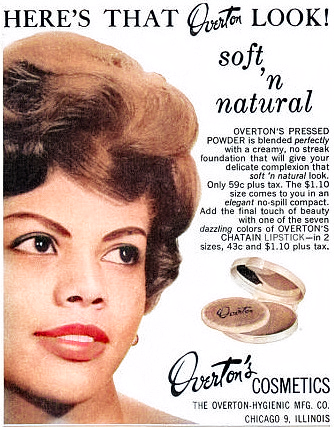

The Overton-Hygienic MFG Co. saw a major drop in sales, as well, during the Depression, but largely sustained its image, continuing to produce High Brown Face Powder and other products in beautiful, elaborately designed boxes that contrasted with the wider industry’s slow move into simpler, more streamlined packaging.

One might assume that Anthony Overton had to make some major sacrifices in his own life—giving up the presumably lavish lifestyle of his 1920s heyday during the rougher times of the ’30s. But according to most accounts, irresponsible opulence was never an issue for the minimalist Overton. In fact, he was famously quite opposed to “showing off” his fortune, and was never seen in an expensive car or otherwise flaunting his status. Rather than upgrading his original Chicago home (which was an apartment above the first Hygienic office building at 5200 S. Wabash), he chose to spend much of his later life as a guest boarder in the homes of his grown-up children.

[Anthony Overton’s three daughters all contributed to the operations of the Hygienic business as well as the Chicago Bee]

While Anthony’s son Everett Overton was taking a larger managerial role at the Hygienic offices, the company still featured a largely female team. The same was true at the Chicago Bee offices down the street, which famously featured an all-woman editorial team led by editor-in-chief Olive Diggs.

By the 1940s, with many of Anthony’s financial failures moving further into the rearview, his legacy was slowly repaired by a series of retrospectives—partially in his own newspaper, but also in the pages of competitors like the Chicago Defender, which praised his career exploits and downplayed his financial scandals in a 1942 profile. “Money never meant much to [Overton],” the article claimed. “For if it had he would have acquired for himself and his family more of the luxuries of life. Business is an end in itself. It’s a game and he likes to play.”

At a company banquet in 1946, just months before Overton’s death, Olive Diggs gave a speech that—due to her direct working relationship with the man—says about as much as one could about his character.

At a company banquet in 1946, just months before Overton’s death, Olive Diggs gave a speech that—due to her direct working relationship with the man—says about as much as one could about his character.

“He treats the rich and poor who come to his desk with the same air of courtesy. He has taught us to be just rather than charitable; fair rather than self seeking, patient rather than indifferent, and has made us more sensitive to our brothers’ needs. . . . For those of us who affectionately call him ‘A.O.,’ we are proud to call you BOSS—and friend. Thank God for men like you.”

Anthony Overton died on July 2, 1946, at 82 years of age. Unfortunately, the Chicago Bee didn’t last much longer after his passing, but for those who expected the Overton-Hygienic Company to go a similar route, the Overton family had other ideas, as most of the surviving children and grandchildren of the founder contributed to the upkeep of the business over the ensuing years.

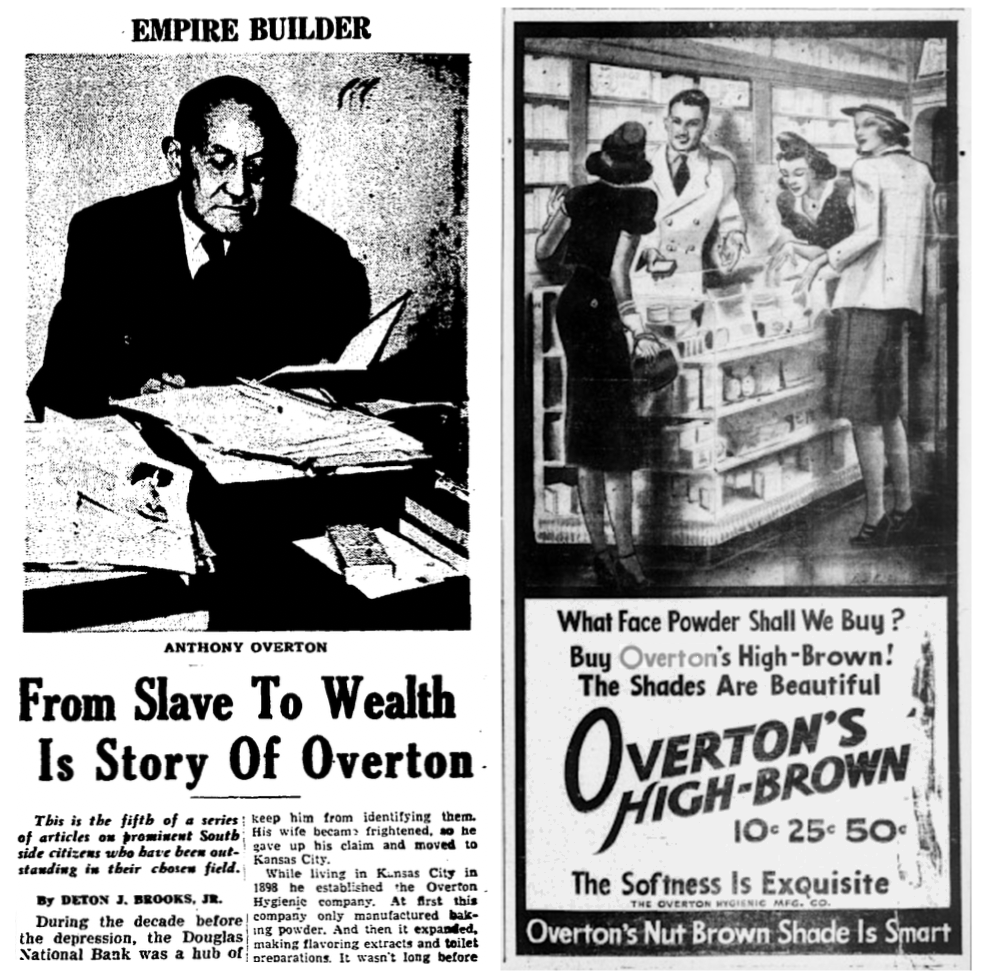

Everett Overton (1889-1960) became company president after his father’s death and piloted the business through the 1950s. Along with spending most of his life attached to the company, Everett also studied chemistry at the Armour Institute with the direct intent of being involved in the development of new cosmetic products. Among the innovations he is credited with is the creation of the “Nut Brown” shade of High Brown Face Powder—as represented by the 1940s artifact in our museum collection. This shade made up for an earlier shortcoming of Overton’s flagship product, working better with darker skin tones.

Everett’s son, Anthony Overton III, took the reins in the 1960s, and while his efforts to boost the aging brand were admirable, he faced far greater challenges than either his father or grandfather, thanks to a cultural shift that saw far more competition from other black-owned cosmetics businesses as well as established white-owned businesses that were finally embracing a wider demographic. Overton was increasingly seen as an older person’s cosmetic brand, while new African-American make-up lines like Flori Roberts and Fashion Fair were considered trendier, more modern options, and could now be purchased in mainstream department stores. Similarly, Chicago’s black-owned Johnson Products Company became the new major hair-care success of the 1960s, largely by following Anthony Overton’s old playbook, i.e., “determining and influencing consumer wants and desires” with its cornerstones products, Ultra Sheen and Afro Sheen.

Overton-Hygienic, by comparison, no longer had the capital to invest in a big R&D department, nor to advertise quite as extensively as Johnson did in magazines like Ebony and Jet.

By the dawn of the 1980s, both the Overton brand and its crumbling Bronzeville headquarters were in dire straits. Anthony Overton III partnered with outside investors to keep the family business going, but it finally collapsed in 1983 after more than 70 years in Chicago.

By the dawn of the 1980s, both the Overton brand and its crumbling Bronzeville headquarters were in dire straits. Anthony Overton III partnered with outside investors to keep the family business going, but it finally collapsed in 1983 after more than 70 years in Chicago.

Sadly, in the aftermath, Overton III failed to salvage critical historical records of the Overton-Hygienic business, and instead opted to toss most of its paperwork into the garbage—a huge loss for future researchers of Chicago’s African-American business and cultural history. On the bright side, though, great steps have been taken in the subsequent decades to renovate both the Overton-Hygienic Building and Chicago Bee Building in Bronzeville, each of which earned Historical Landmark status.

An elementary school in Bronzeville that was named in honor of Anthony Overton, Jr., back in 1963 was closed in 2013, but has since been added to the National Register of Historic Places. It’s in line to be converted into a community center, with local rapper G Herbo, a former student at the school, as a lead investor in the project. After Herbo pleaded guilty in 2023 to a major wire fraud operation, however, it’s unclear whether that plan and its timeline currently stand.

[Top: The Overton-Hygienic Building boarded up in the 1970s and renovated in the 2020s. Middle: The Chicago Bee Building before and after its similar refurbishment. Bottom: The former Anthony Overton Elementary School at 221 E. 49th Street, which was opened in 1963 and closed in 2013. Its proposed future as a community center has been slow to develop.]

[Overton sign above doorway of landmark Overton-Hygienic Building in Bronzeville]

[Even after it the building opened in 1923, some Overton-Hygienic advertisements continued to show the original 6-story artist rendering of their new headquarters rather than the 4-story reality. In some cases, a random 5-story rendering of the building also appeared–again, well after the 4-story building had been completed.]

Sources:

“We Visited the Overton-Hygienic Manufacturing Co.” – Topeka Plaindealer, Jan 20, 1911

“Some Chicagoans of Note” – The Crisis, September 1915

“Anthony Overton Descends Ladder of Fame” – California Eagle, July 22, 1932

“From Slave to Wealth Is Story of Overton” – Chicago Defender, Dec 26, 1942

Everett Overton [obit] – Jet, Feb 11, 1960

Chicago’s Black Metropolis: Understanding History Through a Historic Place, by Gerald A. Danzer, 1999

The Merchant Prince of Black Chicago, by Robert E. Weems, 2020

What a wonderful and thorough article! Thank you so much for mentioning the Makeup Museum too!