Museum Artifact: Pepsodent Antiseptic Bottle, c. 1930s

Made By: The Pepsodent Co., 6901 W. 65th Street, Chicago, IL [Clearing / Bedford Park]

“Pepsodent Mouth Wash kills the stubborn germs in the fastest time it is possible for science to record . . . This remarkable discovery is a new and powerful weapon in fighting germ infections and diseases. It combats instantly the social evil of bad breath.” —Pepsodent Antiseptic advertisement, 1931

Before it was sold to the East Coast soap behemoth Lever Brothers in 1944, the Pepsodent Company was one of Chicago’s most widely recognized commercial manufacturers, with its toothpastes, powders, and mouthwashes positioned right at the forefront of a rapidly emerging oral hygiene market. The company was almost certainly more significant for its game-changing marketing campaigns, however, than for the effectiveness of its products—which often changed formulas in the face of customer complaints and harsh criticism from actual dentistry experts.

Before it was sold to the East Coast soap behemoth Lever Brothers in 1944, the Pepsodent Company was one of Chicago’s most widely recognized commercial manufacturers, with its toothpastes, powders, and mouthwashes positioned right at the forefront of a rapidly emerging oral hygiene market. The company was almost certainly more significant for its game-changing marketing campaigns, however, than for the effectiveness of its products—which often changed formulas in the face of customer complaints and harsh criticism from actual dentistry experts.

Early Pepsodent toothpastes were gritty and sometimes damaging to the enamel of the teeth they were supposed to be cleaning, but national sales numbers remained strong through the 1920s and ‘30s thanks in large part to clever advertising—not just in major magazines like Good Housekeeping, Life, and Ladies Home Journal, but through sponsorships of popular radio programs like “Amos n Andy” and “The Pepsodent Show Starring Bob Hope.”

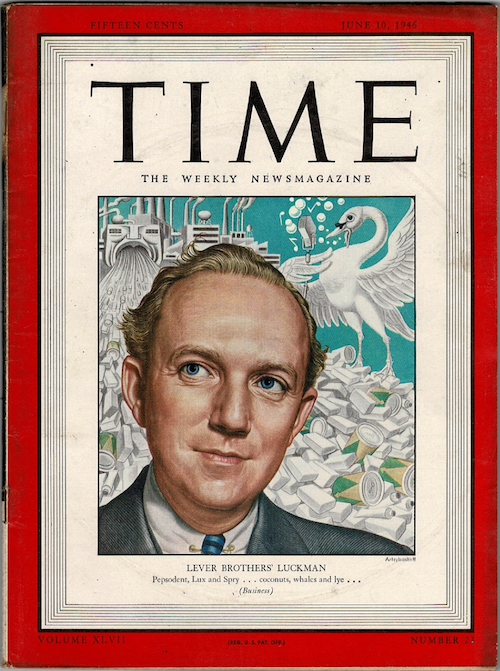

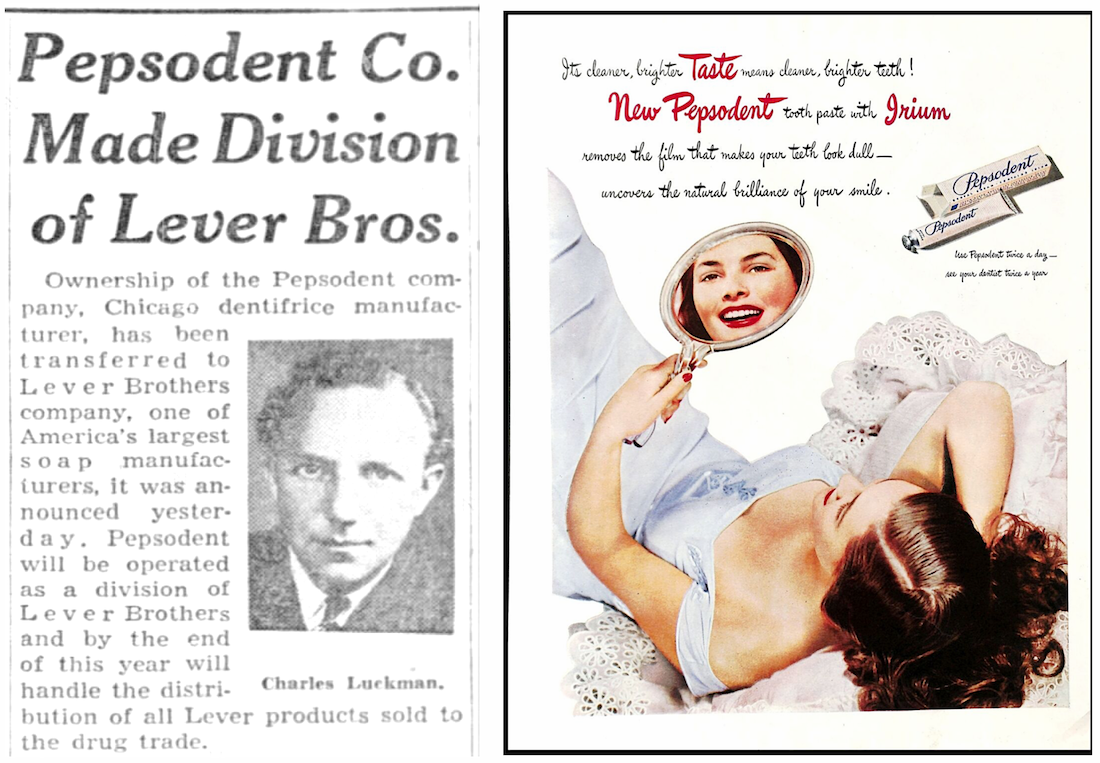

Pepsodent didn’t just hire celebrity spokesmen; it was owned and operated by famous and influential figures, including early investor Albert Lasker, one of the architects of modern American advertising, as well as Charles Luckman, the “Boy Wonder” company president who became a literal architect in his later years, running a firm that built such famed venues as the Los Angeles Forum and the current iteration of Madison Square Garden in New York.

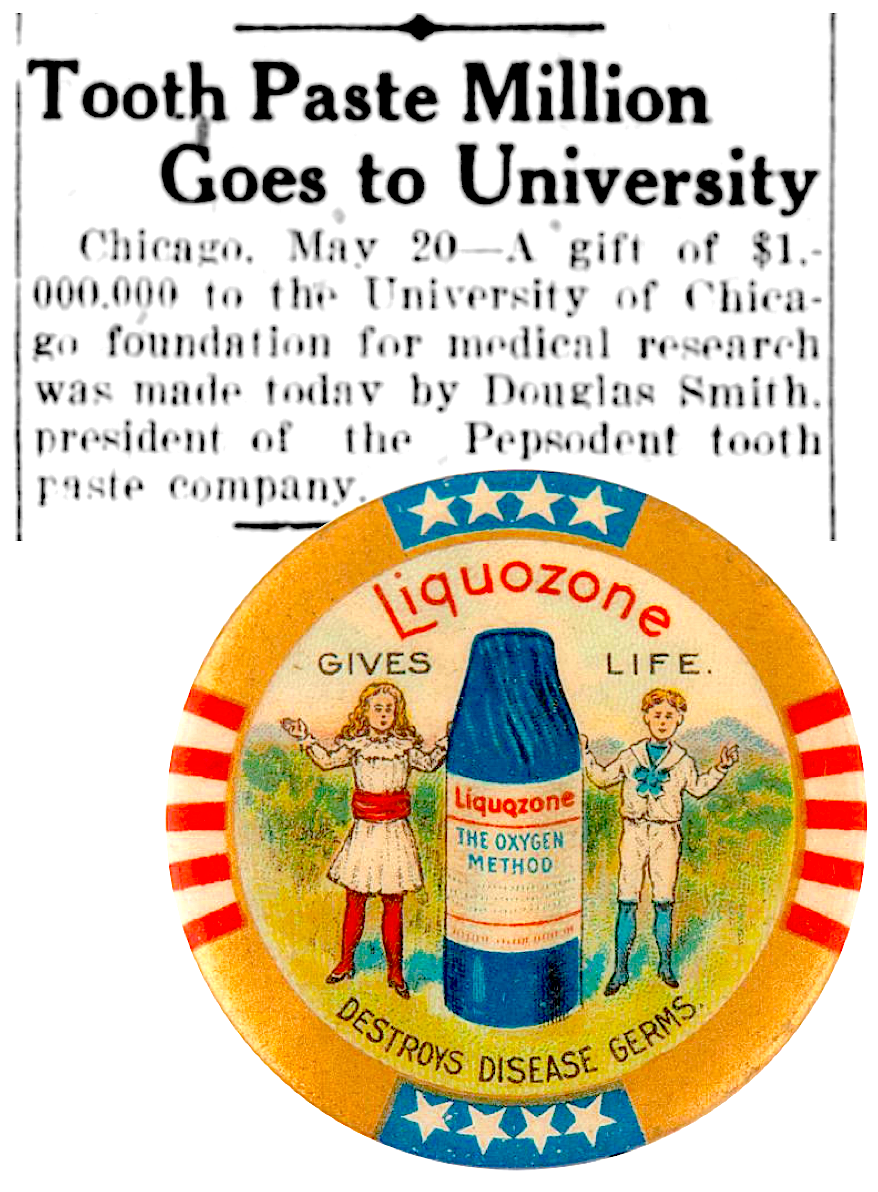

Even the man generally credited with starting the business, Douglas Smith, was something of a Chicago legend. A salesman who’d built his wealth by peddling quack medicines at the turn of the century, Smith was eventually seen as a pillar of the community—a respected banking giant, manufacturer, and philanthropist who famously donated $1 million of his own fortune to help fund medical research at the University of Chicago. After his death and the subsequent sale of the toothpaste business, Smith was still routinely remembered as the “inventor” of Pepsodent. This was, unfortunately, just another bit of false advertising. There was an entirely different fellow—of lesser wealth but equal intrigue—who actually started it all . . .

History of Pepsodent, Part I: Mr. Ruthrauff

The original Pepsodent formula was patented in 1915 by William M. Ruthrauff, a well traveled teacher, coach, and salesman with no background whatsoever, it seems, in dentistry or chemical science.

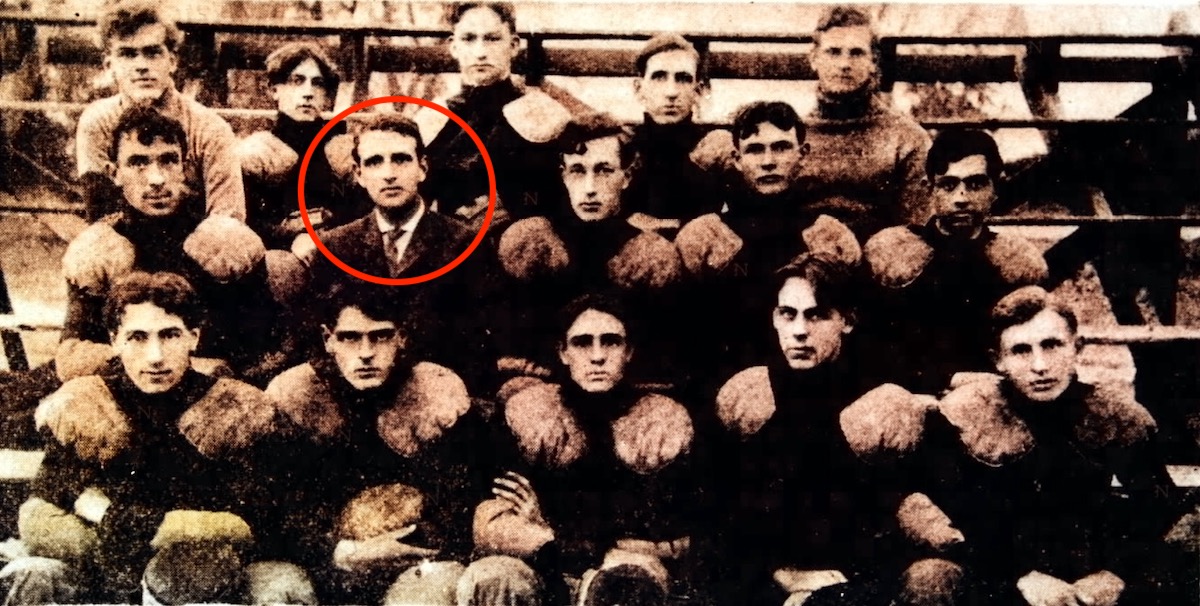

Born in Constantine, Michigan, in 1881, Ruthrauff graduated from Wittenberg College in Ohio, where his father—a reverend and Doctor of Divinity—was also the college president. William looked like he was headed for a similar path in education, teaching in a Joliet high school before joining the faculty at the University of Arizona and—as an amusing footnote—coaching its football team for one season in 1905 (his younger brother John was a standout player on the team). He also spent a few years as the superintendent of public schools for the city of Tucson. After the death of his first wife Ella from tuberculosis in 1906, however, Ruthrauff’s career made a significant pivot. By 1910, he was living in Chicago and working as a representative with the Silver Burdett Publishing Company, selling school textbooks rather than buying them. He also married his second wife Alice, a musician and socialite who would soon play her own significant role in the Pepsodent story.

[The 1905 University of Arizona football team, coached by future Pepsodent inventor William M. Ruthrauff, circled. Sitting directly in front of William is his younger John Mosheim Ruthrauff, who was a star player on the team and later became one of Tuscon’s leading engineers, handling much of the city’s early public works in the 1910s.]

How William Ruthrauff came to start experimenting with “dentifrices,” i.e. tooth powders and pastes, is anybody’s guess. But like just about everybody else involved in Pepsodent’s success, he seemed to recognize a gap in the marketplace and, perhaps more importantly, a method for exploiting it. Or else, he just met the right people at the right time.

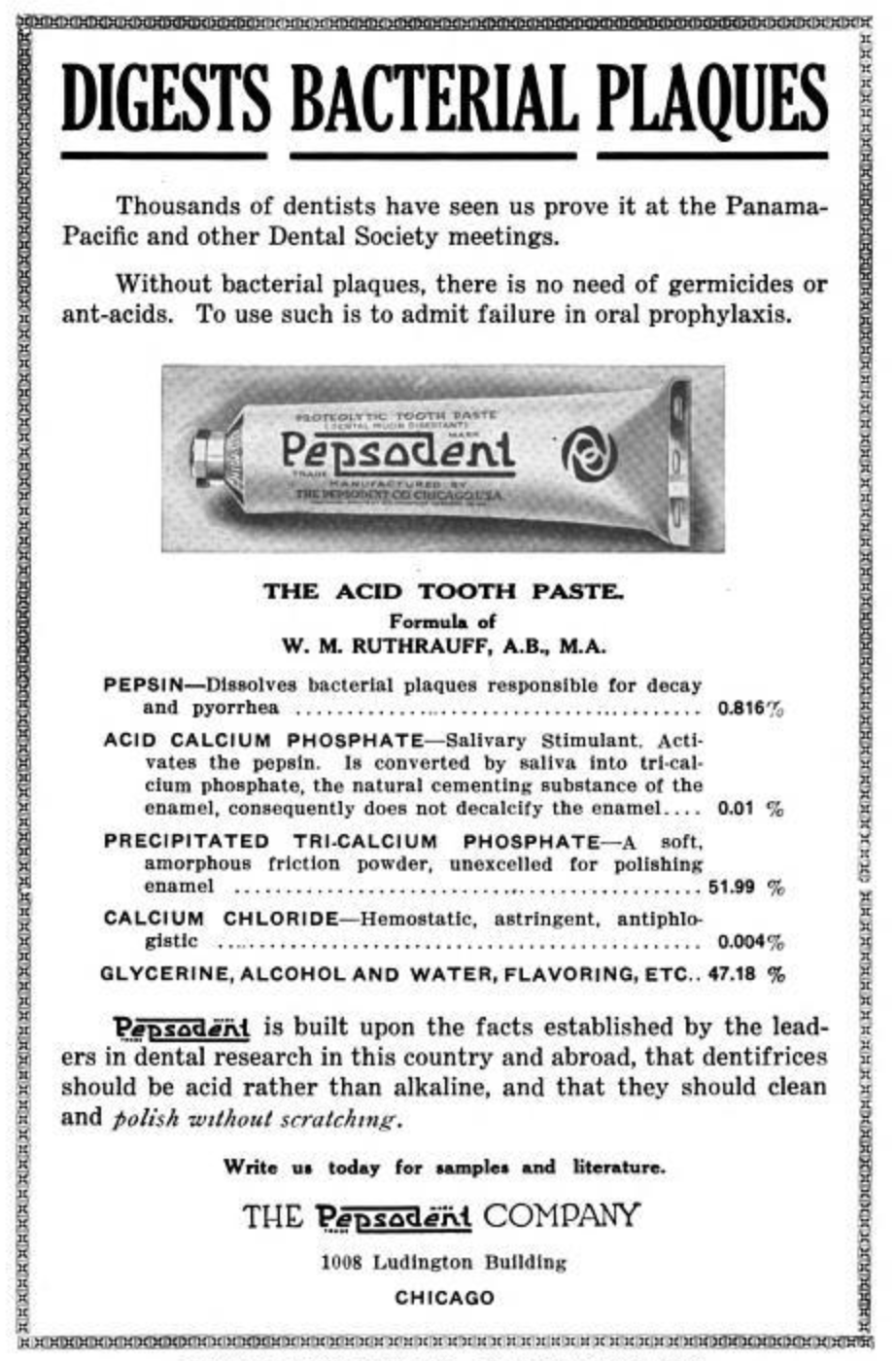

Ruthrauff applied for his first patent in the summer of 1914, describing his invention as a “useful improvement in dentifrices,” the prime purpose of which was “to dissolve mucin film [aka, plaque] as it collects upon the tooth before any harm can be done. Consequently there is no breeding ground for the bacteria, and no need for strong germicidal agents, usually employed in toothpastes.”

The original formula, which produced a non-foamy acid paste rather than the more popular alkaline type, called for “any quantity of tri-calcium phosphate, say 28 av. oz., and triturate in it 2.5 dr. oil of peppermint. Then add and mix thoroughly, 4 dr. gum tragacanth and 12 dr. sugar. To this add 16 fl. oz. solution of pepsin acidulated with hydrochloric acid, not to exceed 5%, such as any standard commercial essence of pepsin. An addition of a desired quantity of petroleum jelly to the above tends to prevent evaporation and adds slightly to the smoothness of the mixture, though this is not essential.”

This patent was approved in March of 1915, and by the first of April, we can already find the first mention of a “Pepsodent Company” doing official business, with the name clearly inspired by the pepsin in the formula. This original office wasn’t in Chicago, though—instead, the Pepsodent Co. was incorporated in the small railroad village of Cimarron, New Mexico, with only $2,000 paid into a declared capital stock of $250,000. Why Cimarron? Well, that’s where William Ruthrauff’s brother-in-law George Remley ran a law office. And since Remley was listed as one of the original incorporators of Pepsodent, it’s likely that the whole arrangement was created with the idea of protecting the patent in order to sell it off to a bigger entity.

Sure enough, after producing a small trial run of Pepsodent in 1915—largely in Western markets—Ruthrauff found the top-drawer Chicago investor he’d been dreaming of.

Douglas Smith, the former quack medicine king turned upstanding tycoon, liked the idea of breaking into the oral hygiene racket, anticipating that Americans were on the brink (finally) of seeing some value in brushing their teeth—hardly a common practice prior to World War I. Smith and his backers agreed to pay Ruthrauff a supposed $250,000 for full rights to the Pepsodent patent and business, equivalent to about $6.5 million in today’s money. This would be doled out in annual installments over five years.

Sweetening the deal even more, Ruthrauff was briefly kept on as a consultant and even used as a key component of Pepsodent’s first big promotional campaign in 1917, as strategized by Douglas Smith and his business partner, the advertising guru Albert Lasker. These early copy-dense advertisements, which aimed to introduce readers to the plague of plaque (“That Film on Teeth: The Source of All Tooth Troubles”), were formatted to look like articles from a medical journal, and the “author” of each “paper” was always none other than William M. Ruthrauff, A.B., A.M.

[Pepsodent’s first big national ad campaign in 1917 used William Ruthrauff’s name prominently. By this point, the Pepsodent Company already had its headquarters at 1104 S. Wabash Ave., where it would remain through the 1920s]

The “A.B. and A.M.” referred to Ruthrauff’s degrees from Wittenberg—I suppose if you can’t include a “D.D.S.” or an “MD,” best to at least put some combination of letters in there for the illusion of authority.

In any case, despite the great success of these ads, Ruthrauff’s name was abruptly retired from Pepsodent campaigns by 1918, and upon his exodus from the enterprise, he was forced to sign a non-compete agreement, short-circuiting any serious hopes he had of extending his toothpaste fame.

Before you feel too sorry for Mr. Ruthrauff, though, it’s worth looking at how he behaved after his proverbial ship came in.

After parting ways with Pepsodent, Ruthrauff and his wife left Chicago for Xenia, Ohio, not far from Wittenberg College. Once there, William took a job as the general sales manager with the Hooven and Allison Cordage Company, but the arrangement started to fall apart pretty quickly. Knowing that he still had several massive installments of Pepsodent payments owed to him by Douglas Smith, Ruthrauff—still well shy of his 40th birthday— found the prospect of a ho-hum life in rural Ohio hard to square. Within months, he was spending most of his time in hotels in Chicago and Philadelphia, barely ever seeing his wife Alice back in Xenia.

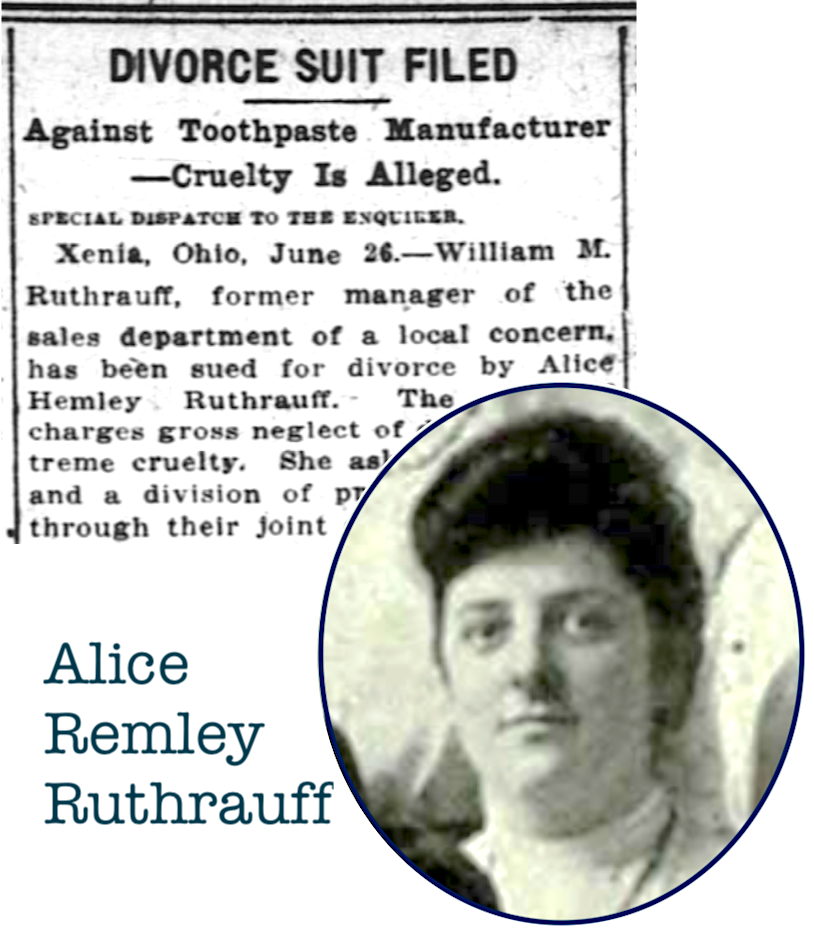

These “business trips” soon turned into something more akin to abandonment, and as such, Alice Ruthrauff filed for divorce in 1920, citing “neglect of duty and extreme cruelty.” William, she said, was leading an “idle, selfish life” with “fast people” in Philly. Even more eyebrow raising was Alice’s claim that she had actually “assisted [William] in preparing the formula for a certain brand of toothpaste which has had a large sale and that she is entitled to a share of the profits.”

Alice Ruthrauff was no pushover, nor was she a naive housewife. A native of Iowa City and daughter of former Iowa Attorney General Milton Remley, she earned her own B.A. from the University of Iowa in 1907, and was later described by local papers as “one of the most popular young women that ever left Iowa City”—“graceful in character . . . cultured in mind . . . lovely to look upon” . . . and a classically trained pianist of “rare worth.”

Alice Ruthrauff was no pushover, nor was she a naive housewife. A native of Iowa City and daughter of former Iowa Attorney General Milton Remley, she earned her own B.A. from the University of Iowa in 1907, and was later described by local papers as “one of the most popular young women that ever left Iowa City”—“graceful in character . . . cultured in mind . . . lovely to look upon” . . . and a classically trained pianist of “rare worth.”

Now, at age 34, she was alone in a quiet house in southwest Ohio, dropped by her deadbeat husband over a toothpaste fortune he hadn’t even fully collected yet.

In some respects, Alice Ruthrauff did have her revenge. Hearing that her husband planned to file for divorce and permanently move to Philadelphia, she beat him to the punch and ultimately won a huge victory: a court-ordered writ of injunction that gave her the right to block the substantial payments still owed to her husband by the Pepsodent Company. We can’t know for sure how this played out for either party over the long haul—while it certainly threw a wrench in her husband’s immediate plans, it’s unclear if justice was served for Alice. She remained in Xenia the rest of her life, and never remarried or had children. She died in 1947 at the age of 62, and was buried in her hometown of Iowa City.

William Ruthrauff, having been denied at least some substantial portion of his Pepsodent riches, spent much of the 1920s trying to build a new business in the same mold. Once his non-compete agreement had run out in 1922, he formed the W. M. Ruthrauff Company in Philadelphia. But his new toothpaste brand, which he called ACIDENT (as in, “acid” + “dental”), was more of an ACCIDENT waiting to happen. Ruthrauff was never quite able to regain his previous status, and by the 1940s, he’d somehow wound up working for a Philadelphia detective agency. He died in 1969, age 88, and was buried in Springfield, Ohio.

[This 1922 ad finds William Ruthrauff explaining his departure from Pepsodent and the big debut of his new toothpaste creation, ACIDENT. The new venture appears to have fizzled out by 1926]

Part II. Mr. Smith & Mr. Hopkins

Pepsodent is often remembered as one of the many big feathers in the cap of Albert Lasker, the “Father of Modern Advertising.” And indeed, Lasker was a minority shareholder in the company and the president of the Chicago advertising agency that plotted the toothpaste’s national rise to prominence. Before we get to Lasker’s role in building the Pepsodent brand, though, it’s worth noting that the company’s president, Douglas Smith, was no stranger to persuasive marketing in his own right.

As mentioned earlier, Smith (b. 1861) was known best to Chicagoans as a bank president (specifically the Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company) and philanthropist. Along with his much-celebrated million-dollar donation to the University of Chicago in 1925, he also funded progressive education programs for the blind; objectively good deeds all around. Still, there’s no getting around the fact that Smith was also a turn-of-the-century snake-oil peddler, and that much of his fortune came directly through the proliferation of bogus potions and nostrums.

It wasn’t necessarily something that had gone unnoticed either. Back in 1905, Collier’s Weekly had published a scathing assessment of Smith and his main business venture of that moment, Liquozone—a highly touted “universal antiseptic” that was actually 99% water and predictably useless.

“Mr. Smith,” the article claimed, “is by profession a promoter. He is credited with a keen vision for profits.” The piece further asserts that Smith was a “master of the silver tongue” with “the intuition of genius,” and that he legitimized his “dubious enterprise” by getting the financial backing of a prominent law firm. He also hired an up-and-coming advertising manager, Claude C. Hopkins, to lead Liquozone’s “enormous advertising campaign,” which relied heavily on an “ingenious system of pseudo-scientific charlatanry” to convince consumers of the product’s legitimacy.

According to a lawsuit filed that same year, Smith’s “silver tongue” may have been used for even darker treachery, as he was accused by the invalid widow of Thomas Oliver of defrauding her out of her valuable shares in the Oliver Typewriter Company (Smith, the widow claimed, had presented himself falsely as a former colleague of her late husband). Smith’s lawyers delegitimized the claim as “obviously a result of the unsettled imagination of an invalid,” and since it was 1905, the court appeared to concur.

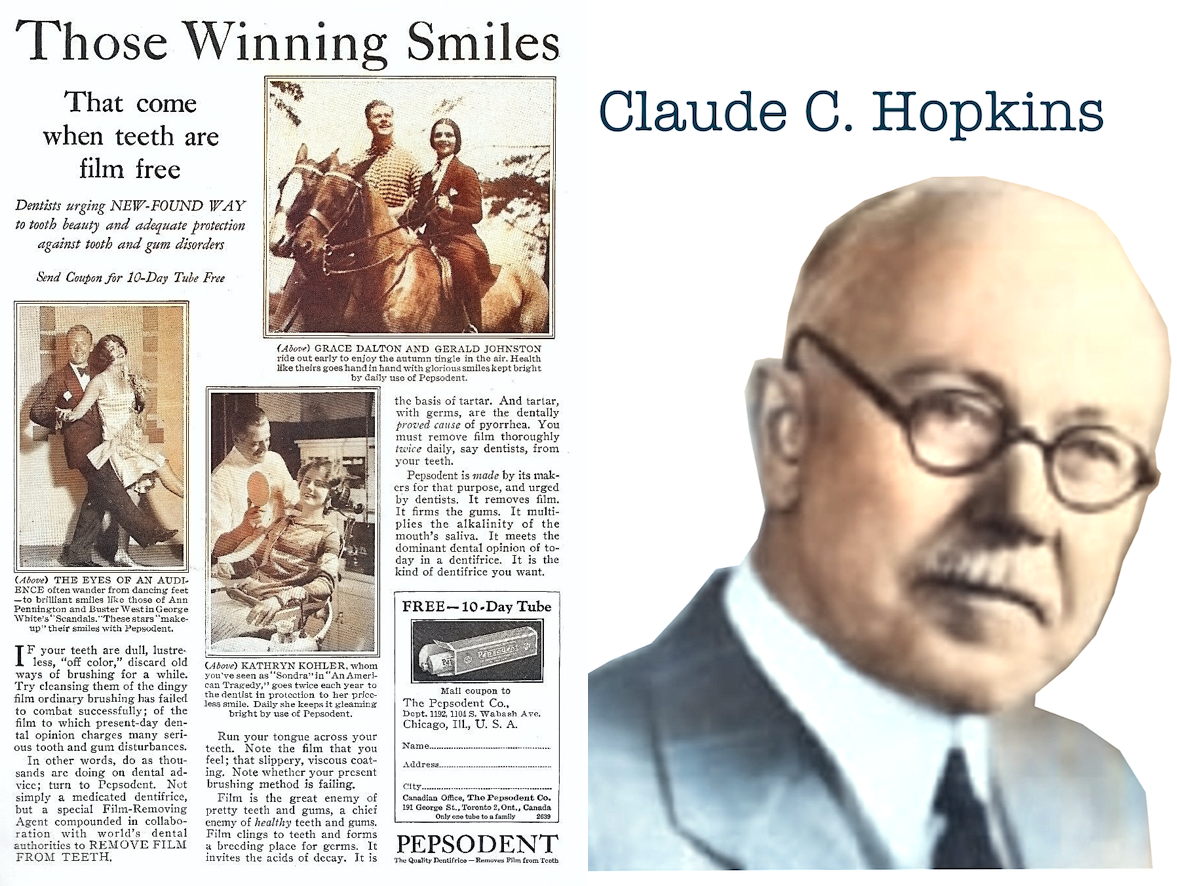

A year later, the Pure Food & Drug Act of 1906 brought some level of reform to the way patent medicines could be advertised. But the subsequent demise of Liquozone didn’t seem to alter Douglas Smith’s perspective very much. When he purchased the Pepsodent Company in 1916, the 55 year-old Smith immediately sought out his old cohort Claude Hopkins, who was now in the employ of one of Chicago’s top ad agencies, Lord & Thomas. Hopkins, who was later credited by Time Magazine for discovering that “a scientific demonstration is more convincing than a string of superlatives,” was tasked with trying to sell an unknown 50-cent toothpaste to a public barely interested in paying 25 cents for the competition. He balked at first, but at Smith’s insistence, he took on the challenge.

“The natural idea with toothpaste is to make it a preventative,” Hopkins later wrote in his memoir My Life In Advertising. “But my long experience had taught me that preventative measures were not popular. People will do anything to cure a trouble, but little to prevent it. Countless advertising ideas have been wrecked by not understanding that phase of human nature. . . . People do not want to read of the penalties. They want to be told of rewards.”

Accounts differ on whether Smith and Hopkins also invited Lord & Thomas president Albert Lasker into this project, or if Lasker simply inserted himself into the conversation. Either way, before the ink had dried on William Ruthrauff’s signature, Lasker had become Smith’s equal partner in the new Pepsodent Company, both as a shareholder and strategist.

[The Ludington Building, 1104 S. Wabash Ave., was home to the Peposodent offices from 1916 to 1931. The building, which dates to 1891, is now owned by Columbia College]

III. Mr. Lasker

“The omnipotent buying public carries in its mind only a dim conception of the part played in its daily life by this enormous new pseudoscience, advertising. How did that tube of Pepsodent toothpaste, for instance, reach your bathroom shelf? . . . It got there, obviously, because somehow Lord & Thomas had at least made you suspect that, of all toothpastes, Pepsodent is the one most imperative to your health and happiness.” —Time Magazine, 1926

Albert Lasker (b. 1880) was a second-generation German-American Jew from Galveston, Texas. He moved to Chicago at the age of 18, joined the Lord & Thomas agency as a lowly errand boy, and within just five years had become a top salesman and a partner in the business, replacing the retiring Daniel Lord.

Albert Lasker (b. 1880) was a second-generation German-American Jew from Galveston, Texas. He moved to Chicago at the age of 18, joined the Lord & Thomas agency as a lowly errand boy, and within just five years had become a top salesman and a partner in the business, replacing the retiring Daniel Lord.

By 1912, at just 32 years of age, Lasker was company president and well on his way to earning a reputation as the “Father of Modern Advertising”—the man who turned salesmanship into a printable art form. His basic mantra: “convince the reader that he should buy because it is in his interest to buy, rather than because you want to sell [it to] him.”

All did not come easy to Albert Lasker. A posthumous account of his life, 2010’s The Man Who Sold America, suggests that he may have suffered from Bipolar II disorder, leading to difficult relationships with family and business partners. His intensity was described in slightly different terms in his own day, though, when Time Magazine wrote that “Everything he laid his hands on turned into money. . . . He has a dynamo of a mind and bovine physical endurance to turn loose upon anything—from a lukewarm bean factory to an all-night bridge game—and the current he generates is seldom grounded.”

Like Douglas Smith, Lasker notably funneled a lot of his excess wealth into philanthropic causes and medical research. But in 1916, the same year he bought his minority interest in Pepsodent, he had no difficulty buying a partial ownership of the Chicago Cubs, as well—an asset he eventually handed off to his friend and client William Wrigley, Jr., along with the naming rights to the team’s new stadium. By this point, Lasker and his agency’s all-star copywriter Claude C. Hopkins had already helped make household names out of Palmolive soaps, Goodyear tires, Sunkist oranges, and Sun-Maid raisins, just to name a few.

[Chicago’s influential Lord & Thomas advertising agency, under the leadership of Albert D. Lasker, helped ramp up sales for a wide range of brands in the 1910s, including Sun-Maid Raisins, Palmolive soap, and Goodyear Tires]

Douglas Smith already knew and trusted Claude Hopkins, who was well on his way to becoming an advertising legend in his own right. But Lasker’s deep pockets and innovative “reason-why” philosophy of marketing had made Lord & Thomas a powerhouse agency capable of lifting Pepsodent well beyond the heights briefly reached by Liquozone a decade prior.

“Lord & Thomas straightaway learned all there was to know in fact and theory about the gritty white ooze that Mr. Smith’s chemists had carefully concocted, and all that there was to know about the toothpaste market—the best distribution areas, geographic and economic,” according to a 1926 article in Time.

Claude Hopkins himself recalled reading “book after book by dental authorities on the theory on which Pepsodent was based. It was dry reading. But in the middle of one book I found a reference to the mucin plaques on teeth, which I afterward called the film. That gave me an appealing idea. I resolved to advertise this toothpaste as a creator of beauty. To deal with that cloudy film.”

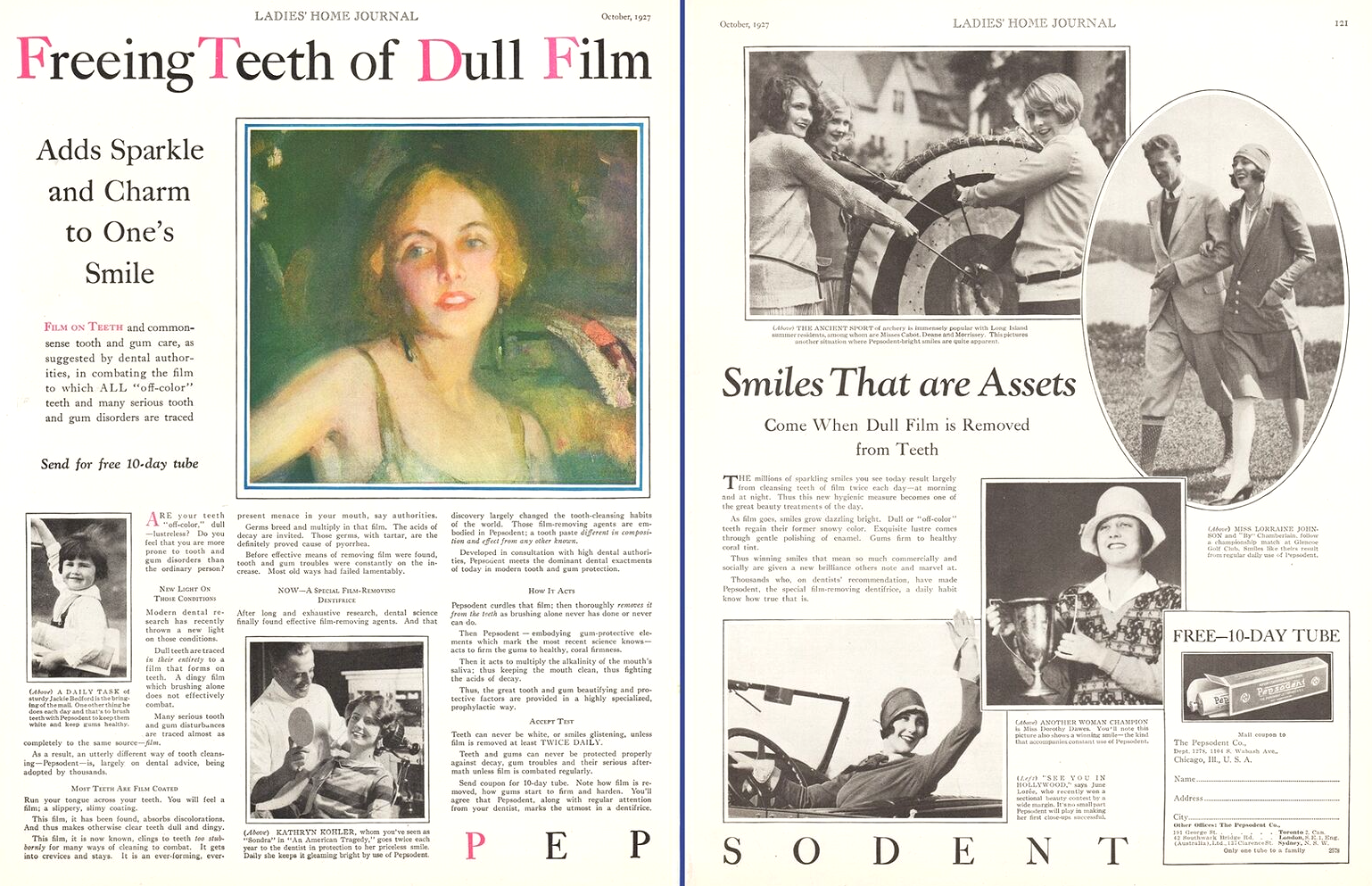

[The focus on removing plaque, or “film,” from teeth remained part of the Pepsodent ad strategy for many years, as evidenced by this two-page spread in Ladies Home Journal from 1927]

Lasker and Hopkins also carried over a particular gimmick from the Liquozone days, as almost every early Pepsodent ad emphasized “test” giveaways—encouraging readers to write in to the Chicago offices at 1104 S. Wabash for a free sample.

“The whole object of the ad was to induce a test for the good of the parties involved,” Hopkins wrote. “I never even mentioned that Pepsodent was for sale. I never quoted its price. My whole apparent object was to prove at our cost what Pepsodent could do.”

“Send the coupon for a 10-day tube,” read the call to action on one ad. “Brush teeth this way for 10 days. Note how thoroughly film is removed. The teeth gradually lighten as film coats go. Then for 10 nights massage the gums with Pepsodent, using your finger tips; the gums then should start to firm and harden. At the end of that time, we believe you will agree, that next to regular dental care, Pepsodent, the quality dentifrice, provides the utmost science has discovered for better tooth and gum protection.”

The first 5-10 years of Pepsodent marketing saw Lord & Thomas produce a massive variety of different ads with slightly tweaked copy and imagery. The goal, quite ahead of its time, was to A-B test how the public—in different parts of the country—responded to even the most subtle alterations in message, whether it concerned the “science” behind the product or the rationale for why a person might want to brush twice a day—a habit that, again, was NOT ubiquitous before Lasker and Hopkins showed up.

Hopkins, who became a millionaire off of the account, would later call Pepsodent the “greatest success in my career,” while Albert Lasker took it a step further, simply saying, “I am Pepsodent.” It’s easy to understand why. Without the aid of a traditional, boots-on-the-ground salesforce, the team at Lord & Thomas had made Pepsodent the country’s No. 1 selling toothpaste within 18 months of its first national advertisement. As for whether the product was equally embraced by the scientific community . . . that’s a different tale.

Part IV. Another Mr. Smith

“If your teeth are dull, lustreless, ‘off color,’ discard old ways of brushing for a while. Try cleansing them of the dingy film ordinary brushing has failed to combat successfully; of the film to which present-day dental opinion charges many serious tooth and gum disturbances. In other words, do as thousands are doing on dental advice; turn to Pepsodent.” —Pepsodent ad, 1927

It was hardly unusual for a hygienic or pharmaceutical product to make promises it couldn’t keep. Many a fortune in America were built on the easy grift of bottling run-off and selling it as a salve. Once Claude Hopkins introduced a more sophisticated brand of pseudo-science into mainstream advertising, however, it likely went even one step further in offending the actual scientists and researchers charged with trying to separate legitimate health aids from quackery.

It was hardly unusual for a hygienic or pharmaceutical product to make promises it couldn’t keep. Many a fortune in America were built on the easy grift of bottling run-off and selling it as a salve. Once Claude Hopkins introduced a more sophisticated brand of pseudo-science into mainstream advertising, however, it likely went even one step further in offending the actual scientists and researchers charged with trying to separate legitimate health aids from quackery.

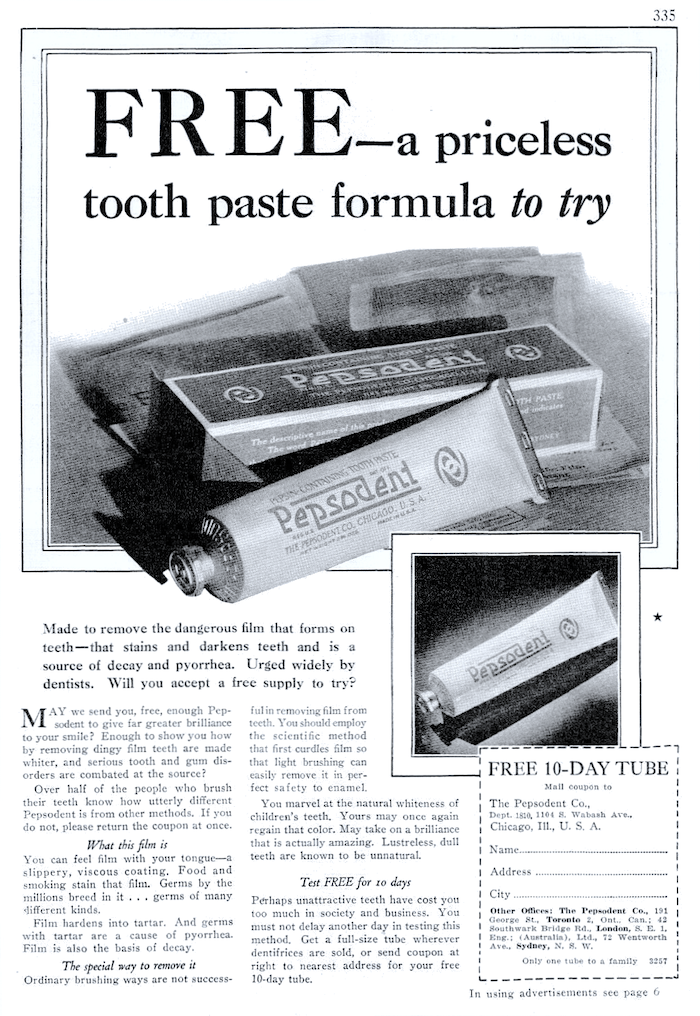

As such, Pepsodent’s rapid rise to prominence inspired no shortage of laboratory analysis from the guardians of dental health. In 1917, one particular headline in the Michigan Dental Journal seemed to sum up their findings rather brutally: “Pepsodent Devoid of Scientific Merit.”

In fairness, the lead researcher behind this study, Columbia University Professor William J. Gies, later clarified his actual findings, suggesting that the editor’s headline was far too “sweeping.” Pepsodent wasn’t completely useless, he said. It could clean the teeth alright. What it couldn’t do, unfortunately, was the thing it primarily claimed to do—which was to eliminate the film, or plaque, on the teeth.

“Our results make it evident,” Gies wrote, “that Pepsodent is put on the market in utter ignorance of the dental and biochemical principles involved, or with intent to mislead the multitude that may usually be deceived by plausible advertisement.”

Attacks like this weren’t ideal for Douglas Smith and Albert Lasker. But then again, they knew that a lot more people read Ladies Home Journal than the Michigan Dental Journal. And so, the advertising continued in the same style, backed by vague claims like “All Statements Approved by High Dental Authorities” and “Now advised by leading dentists the world over.”

By 1922, with Albert Lakser fully embracing Pepsodent as his pet project, the company reached a new sales high, hitting the $6 million mark—a massive leap from the $200,000 it had tallied in its first year. Leaning into the “altruistic advertising” concept, ads now claimed that Pepsodent was “part of a world-wide crusade for better tooth protection” and that it was “used in homes of some 50 nations, largely by dental advice.”

That momentum couldn’t carry on forever, though. Following the death of Douglas Smith in 1927, his son Kenneth Gladstone Smith (b. 1892)—who’d already been installed as president—was faced with the company’s first major crossroads, as increased competition was starting to put a squeeze on Pepsodent’s growth. The business had distribution in 62 countries and owned factories in Canada, France, Germany, Mexico, Argentina, New Zealand, and Australia, but it was starting to tread water on the homefront.

In response, Kenneth Smith looked to upgrade Pepsodent’s Chicago facilities. In 1929, the corporate offices moved from their original home in the Ludington Building on Wabash Avenue to the Palmolive Building at 919 N. Michigan Ave. (where Lord & Thomas also had its offices). Some manufacturing remained at the Ludington Building, but by 1931, Smith also purchased land for the erection of a new, modern factory complex in the Clearing Industrial District, at 6901 W. 65th Street. This would remain Pepsodent’s primary U.S. production plant for many years, even after its sale to outside interests in 1944.

“One of the best examples of the single story plant to be found anywhere is that of the Pepsodent Co., on the outskirts of Chicago,” the magazine Modern Packaging proclaimed in a 1940 article. “It is an unusually fine example of efficiency, not merely in the utilization of packaging equipment, but in its facilities and planning for so-called ‘get to’ and ‘take away’ work—i.e., the handling of raw and finished materials.”

Inside the Chicago Pepsodent Factory, 1940

[Top Left: Sketch of the Pepsodent plant published in 1931. Top Center: Shipping cartons are loaded on an overhead conveyor from the raw materials store room to the production floor. Top Right: Gravity roller conveyors take finished stock to shipping room. Bottom Left: Workers inspect products at the automatic tube filling station. Bottom Center: Automatic high speed filling and capping equipment prepares bottles of antiseptic. Bottom Right: Filled toothpaste tubes placed in cartons. Interior views from Modern Packaging, Feb 1940]

Superior even to the modernization of its factory, though, was Pepsodent’s wildly successful maiden voyage into the still new medium of radio. Starting in 1929, the company began sponsoring the “Amos n’ Andy” program on the NBC network. In this case, even the forward-thinking Albert Lasker wasn’t sure about the strategy, but Pepsodent vice president Walter Templin knew better. He’d seen the mesmerized, captive audiences that popular radio serials were creating, and he pushed hard for Pepsodent to dive into the airwaves.

“Amos n Andy” was essentially a minstrel show in audio form—not something any corporation would touch with a 10 foot pole today—but as the ‘20s gave way to the dreary days of the early ‘30s, the comedic half-hour program exploded in popularity and almost single-handedly shot Pepsodent back to the front of the toothpaste marketplace.

It’s a moment in time that’s also captured for posterity in the classic 1933 film, King Kong, which includes a vision of New York’s Times Square as it looked that year—a massive neon Pepsodent sign towering over all others, still touting its longstanding promise: “Removes Film from Teeth.”

[The “Amos n Andy” comedy show of the 1930s, sponsored by Pepsodent, featured white voice actors Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll performing as black characters, carrying over minstrel show tropes to radio. It wound up becoming one of the most popular radio shows of all time, listened to by millions of Americans every week.]

[The “Amos n Andy” comedy show of the 1930s, sponsored by Pepsodent, featured white voice actors Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll performing as black characters, carrying over minstrel show tropes to radio. It wound up becoming one of the most popular radio shows of all time, listened to by millions of Americans every week.]

[Left: The neon Pepsodent sign in Times Square, 1933. Right: A re-creation of Times Square in the 1930s, as seen in the 2005 re-make of King Kong, courtesy of Universal Pictures.]

Part V. Mr. Luckman

As with the first wave of Pepsodent success, the huge spike in sales driven by “Amos n Andy” led to another series of pushbacks from critics. In 1930, Kenneth Smith had approved the first major change in the Pepsodent formula, replacing the two original polishing agents—calcium phosphate and pyrocalcium phosphate—with the less abrasive dicalcium phosphate.

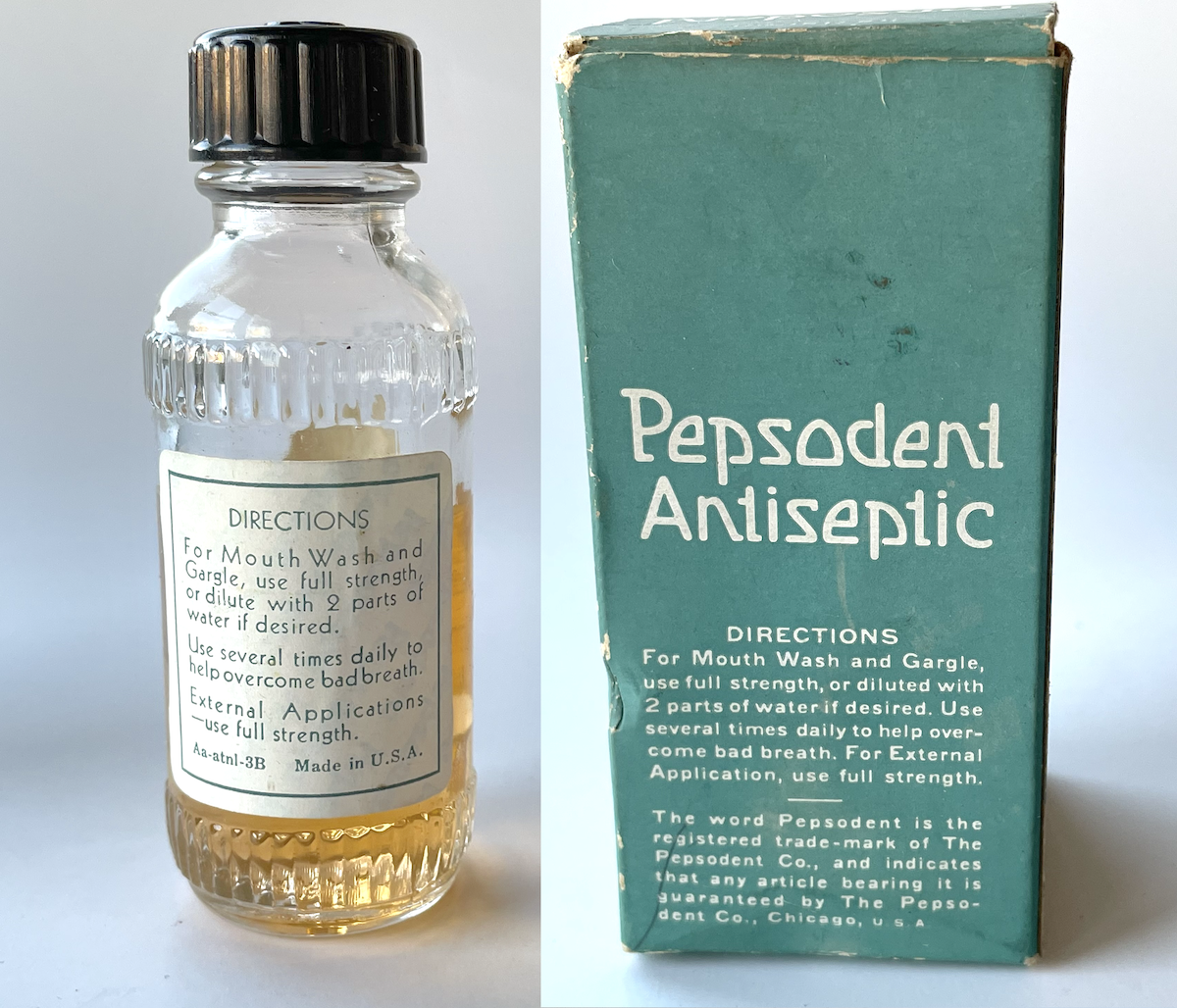

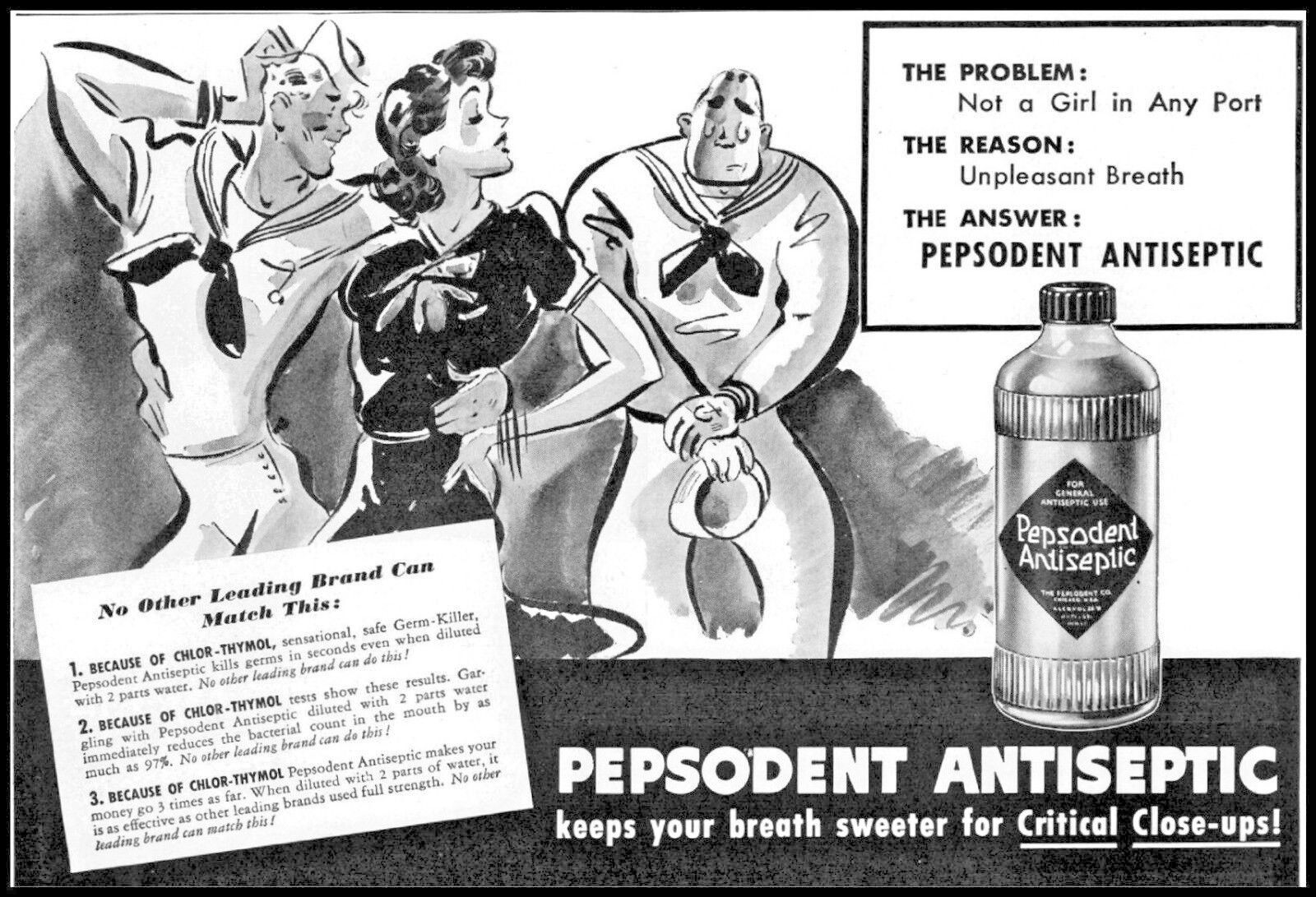

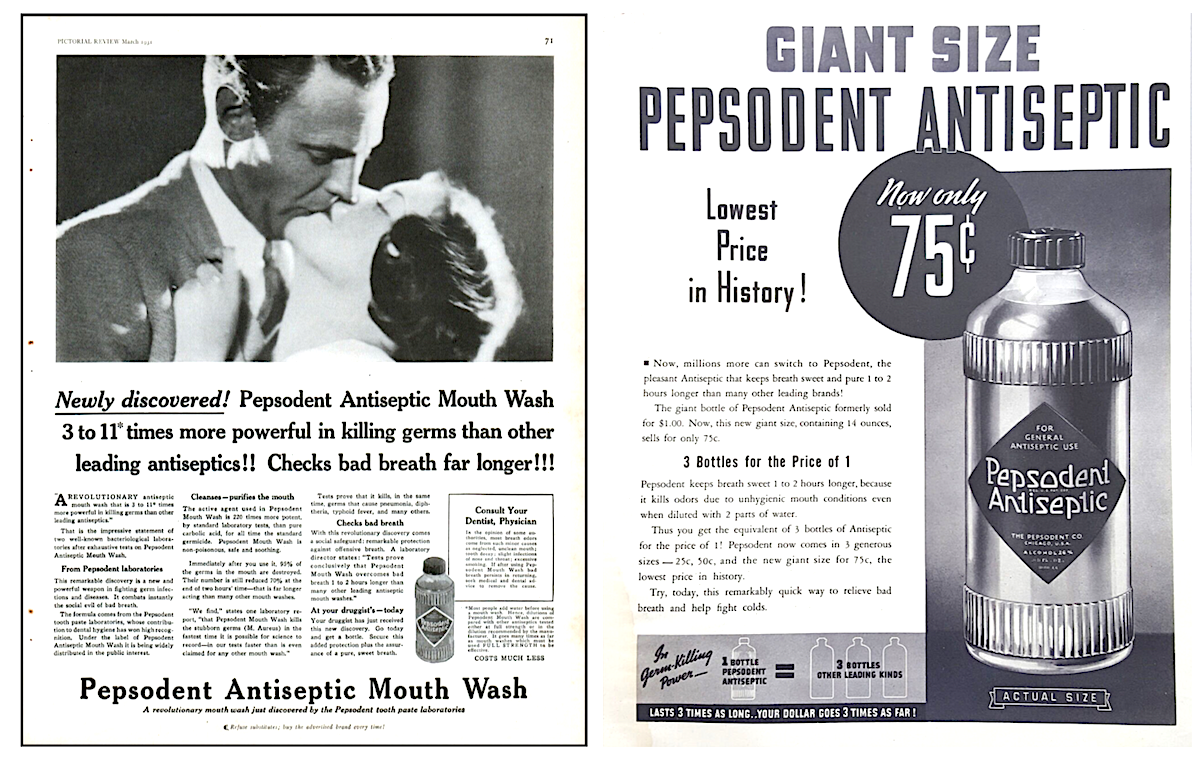

The change produced a grittier paste, though, and one that sometimes hardened and broke while still in the tube. Disappointed retailers, customers, and medical professionals again put the product in their crosshairs, and Pepsodent was forced to spend much of the 1930s on the defensive, making further tweaks to the formula and publishing booklets in defense of its efficacy. Smith also pushed to diversify the Pepsodent product line, with a great deal of emphasis put into its tooth powders and mouth wash, the latter of which was known as “Pepsodent Antiseptic.”

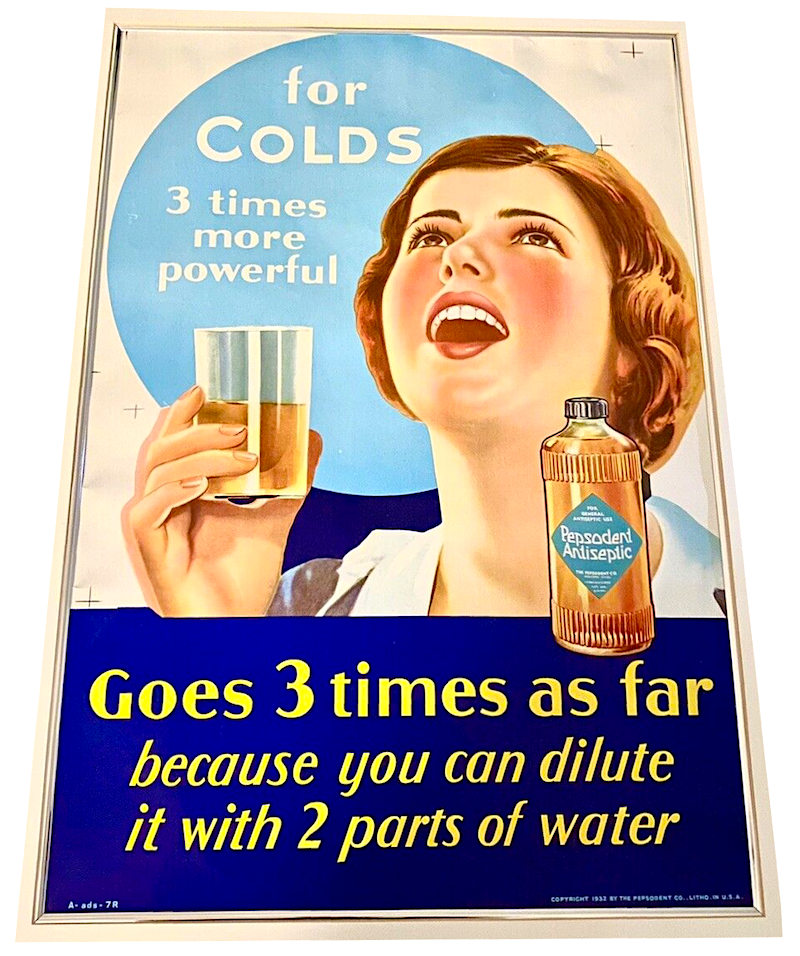

The bottle of Pepsodent Antiseptic in our museum collection likely dates from the mid to late 1930s, and includes its original box with a listed price of 10 cents, along with a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. This product, which contained 26% alcohol, was a breath freshener and bacteria killer like any modern mouthwash, but it was also promoted quite aggressively in the ‘30s as a preventative for the common cold.

“If everyone in this family uses Pepsodent Antiseptic, there should be 50% fewer colds,” read one 1935 ad, citing a very questionable in-house study.

[Left: Pepsodent Antispetic ad from 1935. Right: Antiseptic bottle and accompanying promo flyer from our museum collection, 1930s.]

The last great shift in management during Pepsodent’s Chicago era came in 1936, when VP Walter Templin stepped down, and Kenneth Smith hired three new executives into the organization: Leo C. Hoffman (VP of production), Stuart Sherman (VP of advertising), and Charles Luckman (VP of sales).

Luckman (b. 1909) was yet another in a line of Renaissance men to pass through the Pepsodent offices. A native of Kansas City, he’d graduated with honors from the University of Illinois School of Architecture in 1931, but with so few buildings getting built in the early years of the Depression, he wound up temporarily sidetracked into the world of sales—specifically with the Colgate-Palmolive Company, a Pepsodent rival.

Kenneth Smith managed to poach the 27 year-old Luckman in 1936, and his star continued to rise. During his first few years on the job, he was particularly influential in navigating Pepsodent’s dealings with independent drug stores, which were responsible for about 75-80% of its sales. During the Depression, many small druggists were feeling undercut by larger department stores selling products like Pepsodent at slashed prices—often promoted as enticing tie-ins with other items in the store. Luckman spent a whole year on the road glad handing with these clients and speaking in support of fair trade laws. He also gave Pepsodent something it hadn’t often had—a national human salesforce, increased from less than 10 to more than 100 by 1938.

“A lot of people are mistaken,” Luckman said years later in an 1987 interview with the Associated Press. “They think motivation is: ‘How do you get people to do what you want them to do?’ That’s crazy. Motivation is ‘how do you get people to do their best.’ That’s all you need to get from people. If they do their best, everything will come out all right.”

1938 was also the year that Pepsodent ended its long-running affiliation with “Amos n Andy.” Luckman and Lasker both agreed that it was time for a new flagship radio campaign, and on the recommendation of Albert’s son Edward Lasker, they hired a relatively unproven 35 year-old comedian from Cleveland named Bob Hope.

“The Pepsodent Show Starring Bob Hope” premiered nationwide on September 27, 1938, on NBC, and would eventually run for 10 years, ranking among the most popular radio shows of the WWII era and making a superstar out of its host.

“The Pepsodent Show Starring Bob Hope” premiered nationwide on September 27, 1938, on NBC, and would eventually run for 10 years, ranking among the most popular radio shows of the WWII era and making a superstar out of its host.

Once again, the braintrust at Pepsodent had struck oil, and despite a less than friendly relationship between Albert Lasker and Bob Hope, the company sponsorship continued for the full duration of the program.

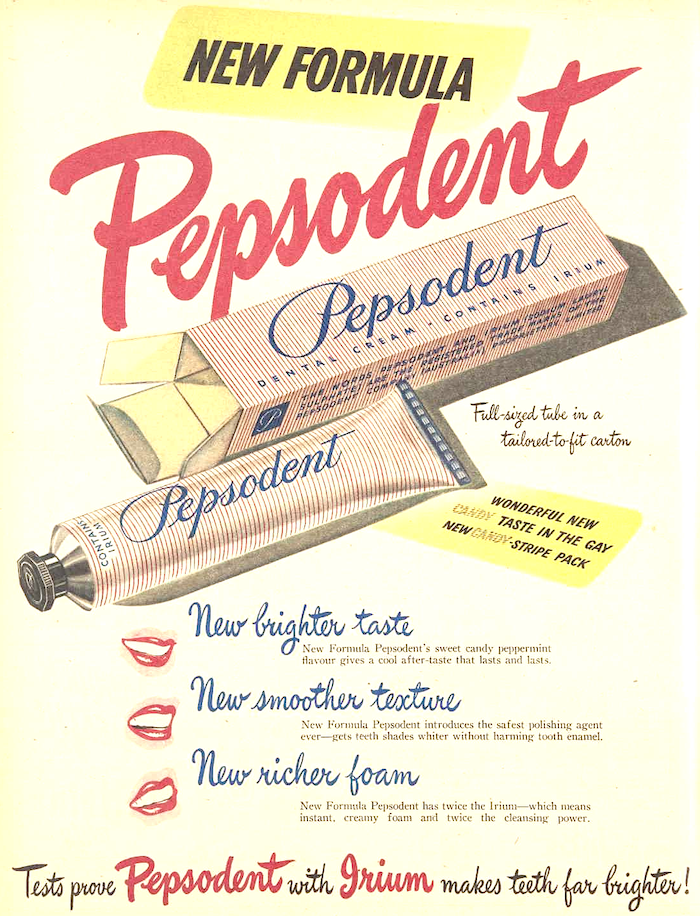

The launch of the Pepsodent Show, perhaps as no coincidence, coincided with one of the most famous, or infamous, marketing ploys of Albert Lasker’s career . . . the invention of a new element called Irium.

[Broadcast of the first episode of the Pepsodent Show with Bob Hope, September 27, 1938]

VI. When the Lever Breaks

“There’s only one dentifrice that contains that marvelous new tooth cleanser IRIUM—and that’s Pepsodent . . . So what? So this! Irium is so remarkable in helping Pepsodent safely brighten teeth—in helping Pepsodent gently brush away stubborn surface stains—that Pepsodent contains Irium has taken the country by storm!” —Pepsodent advertisement, 1938

After tinkering with its ingredients throughout the 1930s, Pepsodent eventually settled on a new formula for its pastes and powders, developed by one of the company’s longtime consultants, Dr. R. A. Kuever, a professor at Alice Ruthrauff’s old stomping grounds, the University of Iowa. Known internally as Formula 99, the new version of Pepsodent, patented in 1938, added a detergent and foaming agent more in line with other toothpastes on the market. The new ingredient, sodium alkyl sulfate, could have been casually mentioned in subsequent advertising, but Albert Lasker knew that the right wording or phrasing meant everything. And so, bold as ever, he simply invented a new, snazzy name for sodium alkyl sulfate: IRIUM. And for many years thereafter, this fictional element would remain Pepsodent’s No. 1 magical selling point.

As Lasker has anticipated, the allure of Irium inspired thousands of people to favor Pepsodent for a shining smile—especially when the message was coming directly from the nation’s new favorite comedian.

In Bob Hope’s autobiography, he even recounts a visit to Pepsodent’s Chicago factory around 1940, where he greeted the workers with the line, “Irium again!” [pronounced to sound like “here I am.”] “That was pretty funny if you knew the secret ingredient in Pepsodent,” Hope explains in the book. “Something called Irium . . . nobody ever found out what it was.”

Was the whole Irium campaign misleading? Had Albert Lasker, during his 25 years with Pepsodent, essentially used “modern advertising” tricks to deceive the public just like the patent medicine trolls of the past?

There might be an argument there, but there’s also an equal argument that the massive success of Pepsodent and its 25-year promotional campaign was essential to the wider evolution of dental care in America.

As Lasker later said himself, “The main thing advertising of dentifrices has done is [to] keep the people thoroughly alive to the needs of oral hygiene, saving them untold suffering and sickness.”

Naturally, this cultural sea change also caught the attention of other industrialists hoping to cash in on it. One of these was Lever Brothers, a Massachusetts-based, British-backed soap manufacturer looking to compete with rivals Procter & Gamble and Colgate-Palmolive in the toothpaste game. Acquiring Pepsodent would certainly achieve that goal, but in order to pursue a deal, Lever Bros. execs would have to determine which shareholder of Pepsodent actually wielded the most power: Kenneth Smith, Albert Lasker, or Charles Luckman?

In 1941, Smith had reduced his day-to-day involvement in the business and rewarded Charles Luckman with a promotion to Executive VP. By 1943, Luckman was elected president of the company at the age of 34, thus earning him his famous moniker from Time Magazine: “Boy Wonder of American Business.” As a progressive thinker, Luckman was sometimes questioned by his fellow executives, but tended to earn their respect, as well as that of his employees in Chicago, many of whom saw their wages rise with Pepsodent’s success.

“It seems strange to me that some of us in industry were trying to keep wages as low as possible,” Luckman later recalled, “whereas we had adequate proof that every time the standard of living was raised, we, as manufacturers, made more money.”

With Luckman in charge, the folks at Lever Brothers thought they now had the lay of the land and approached the Boy Wonder about a potential buyout. At first, Luckman steadfastly refused. In the midst of World War II, though, he also firmly believed—and publicly stated—that another major economic depression was on the horizon once the war was over. This outlook likely led to his change of heart.

In 1944, Luckman met with Kenneth Smith, who still owned 60% of Pepsodent. Smith again put his trust in Luckman and handed over his voting rights on a sale to the Boy Wonder. Luckman owned 15% of the business himself, which essentially became 75% with Smith’s blessing. This left Albert Lasker as the remaining big shareholder left to convince.

Things did not go smoothly there. Lasker, who could also be quite petty, considered Pepsodent to be his baby, and he was more than happy to shoot down the Lever sale in spite of his partners’ pleas. To finally get the deal done, Lever’s representative Frederick Peyser had to personally apologize to Lasker for not coming to him first. Lever Bros. also had to pay Lasker $1 more per share than they paid anyone else . . . a remarkable final jab that Smith and Luckman never forgave him for.

Sadly, Kenneth Smith died of pneumonia just a year later, in December of 1945. He was only 53.

Albert Lasker, who’d left Lord & Thomas behind in 1941, redirected much of the money from his sold Pepsodent shares into his foundation dedicated to cancer research. He was diagnosed with cancer himself in 1951 and died a year later, aged 72.

Charles Luckman stayed on as an executive with Lever Brothers after the sale, but spent much of the late 1940s working for the government, as he was specifically recruited by President Truman to serve on several committees, including the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, the Citizens Food Committee, and the Freedom Train, which was focused on helping the recovery in Europe after WWII.

In 1950, Luckman left Lever Brothers and returned to his original love, architecture. His firm Luckman & Associates went on to great success, designing some iconic mid-century buildings—L.A.’s Forum, Boston’s Prudential Tower, Houston’s NASA Manned Spacecraft Center, and New York’s updated Madison Square Garden, among them. Charles Luckman died in 1999 at the age of 89.

While the Pepsodent Company ceased to be an independent Chicago business after 1944, Lever Brothers continued to operate the factory at 6901 W. 65th Street as its “Pepsodent Division” through the 1960s. When Colgate and Crest beat them to the punch on adding fluoride to the formula, though, the once mighty Pepsodent brand died a slow death, and was gradually de-emphasized as a Lever Bros / Unilever property in the latter half of the century. The 65th street plant was sold in the mid 1980s, and the rights to Pepsodent toothpaste in North America were acquired by the Church & Dwight Company in 2003 (Unilever still owns the rights in other parts of the world).

In more recent years, Pepsodent has largely disappeared from the American market, as Church & Dwight has opted to focus on its Arm & Hammer toothpaste brand. There were no more clever marketing schemes left in the basket.

Sources:

The Great American Fraud: Articles on the Nostrum Evil and Quacks, by Samuel Hopkins Adams, 1907

“Lovely Bride’s Adieu to Athens” – Iowa City Press-Citizen, Jan 17, 1910

“New Chemical Company” – Santa Fe New Mexican, April 2, 1915

“Pepsodent Devoid of Scientific Merit’ – Michigan Dental Journal, Dec 1917

“Divorce Suit Filed Against Toothpaste Manufacturer” – Cincinnati Enquirer, June 27, 1920

“Court Grants Her Control of Money Coming to Husband” – The Gazette (Cedar Rapids), July 2, 1920

“Business Coalition” – Time, June 14, 1926

“Douglas Smith, Philanthropist, Dies in Hospital” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 8, 1927

My Life In Advertising, by Claude C. Hopkins, 1927

“Pepsodent to Have 2 Floors on Boul Mich” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 8, 1929

“Pepsodent to Have $500,000 Chicago Plant” – Chicago Tribune, July 19, 1931

“Get To and Take Away” – Modern Packaging, Feb 1940

“Charles Luckman, 34, Heads Pepsodent Co.” – Minneapolis Star, July 3, 1943

“Pepsodent Co. Sold to Lever” – Star-Gazette (Elmira, NY), June 30, 1944

“Corporations: Merger of Champions” – Time, July 10, 1944

“The Team That Made U.S. Football History” – Arizona Daily Star, October 19, 1955

“Lever Bros. Co. vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue,” 1957

“Charles Luckman: The Boy Wonder Looks Back” – Associated Press, Feb 7, 1987

Don’t shoot, It’s Only Me : Bob Hope’s Comedy History of the United States, 1990

“Albert Lasker’s Advertising Revolution” – Chicago History, Fall 2002

The Man who Sold America: The Amazing (but True!) Story of Albert D. Lasker, by Jeffrey L. Cruikshank and Arthur W. Schultz, 2010

How about Aim and Close-Up. They were made in that building in the late 70’s and 80’s. I worked there at that time. We ran 3 shifts, 7 days a week for years. We couldn’t make enough.

Hi

I live in England & I have a vinyl dated December 4th 1938 Pepsodent Programme 47 Part 2 Sunday.

The Gramophone Co.Ltd

Hayes, Middlesex,

England

I am writing to ask permission to use this photo with proper citation in a piece I am writing which will be published in the American Orthodontics Associations Journal.

https://www.madeinchicagomuseum.com/single-post/pepsodent/

Respectfully,

Marisa Porter

Hi Marisa. Which specific photo are you referring to? –Made In Chicago Museum