Museum Artifact: Pines Automatic Winterfront Radiator Shutter, c. 1920s

Made By: Pines Winterfront Company, 1135 N. Cicero Ave., Chicago, IL [West Humboldt Park]

“Winterfront is a necessity for winter driving because it regulates the inflow of cold, thereby maintaining the motor at highest efficiency. It is an important factor in keeping thousands of cars in operation during the winter and has been of big help in bringing about the ’12-month motor car.’” —Pines Winterfront advertisement, 1925

It’s not a common talking point in the early history of the American automobile, but for the first couple decades of their manufacture, engineers didn’t overly concern themselves with making “winter fit” cars . . . especially not ones with engines capable of withstanding a Chicago caliber cold blast. Instead, most drivers innately understood—like the Midwestern boat owners of today—that there was a season for driving and a season for vehicular hibernation.

It’s not a common talking point in the early history of the American automobile, but for the first couple decades of their manufacture, engineers didn’t overly concern themselves with making “winter fit” cars . . . especially not ones with engines capable of withstanding a Chicago caliber cold blast. Instead, most drivers innately understood—like the Midwestern boat owners of today—that there was a season for driving and a season for vehicular hibernation.

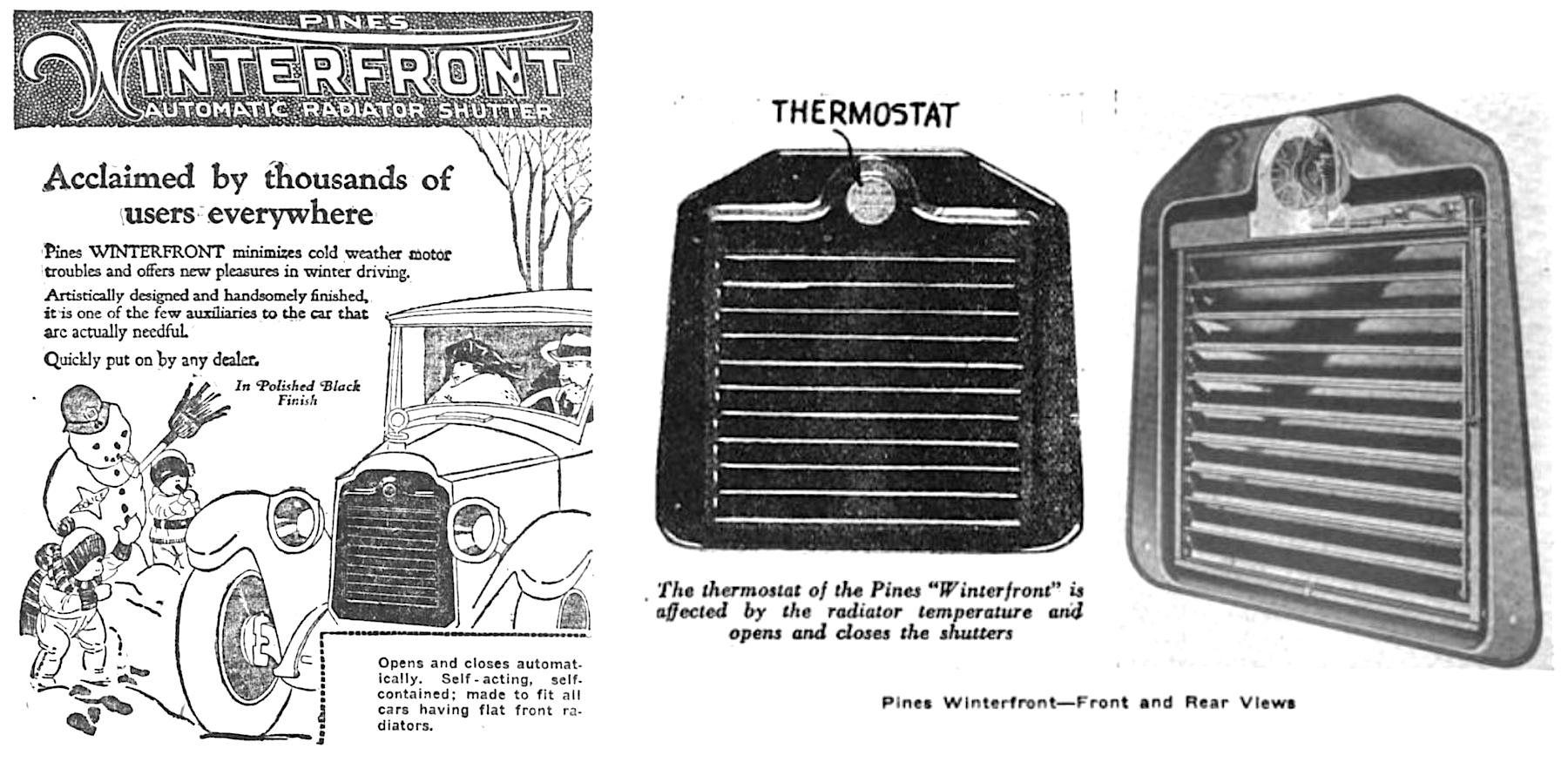

The Pines Winterfront Company helped change that, introducing and mass-producing a singular product that could reliably protect the motors of many of the popular automobiles already on the road in the 1920s. Attached to the grill of the vehicle, this metal radiator shutter, known as the Automatic Winterfront, was thermo-controlled and responsive to the temperature around it, closing up its slats to keep cold air away from the motor when needed, then automatically opening up and allowing airflow once the motor had fully heated up. As its own inventor would later describe it, the Winterfront was a fairly “simple solution” to one of the biggest causes of engine failure, and for that same reason, it didn’t require a lot of complicated explanation to get potential buyers—both in the form of car manufacturers and everyday drivers—interested in the upgrade.

The Winterfront boom was a relatively fleeting one, as the big car companies predictably integrated superior mechanisms by the 1930s, rendering the old grill attachments obsolete. Nonetheless, there is at least one lasting testament to the brief but bountiful success of the Pines Winterfront Company, and it’s hard to miss if you’re ever driving—in wintertime or otherwise—through Humboldt Park around Division Street and Cicero Avenue.

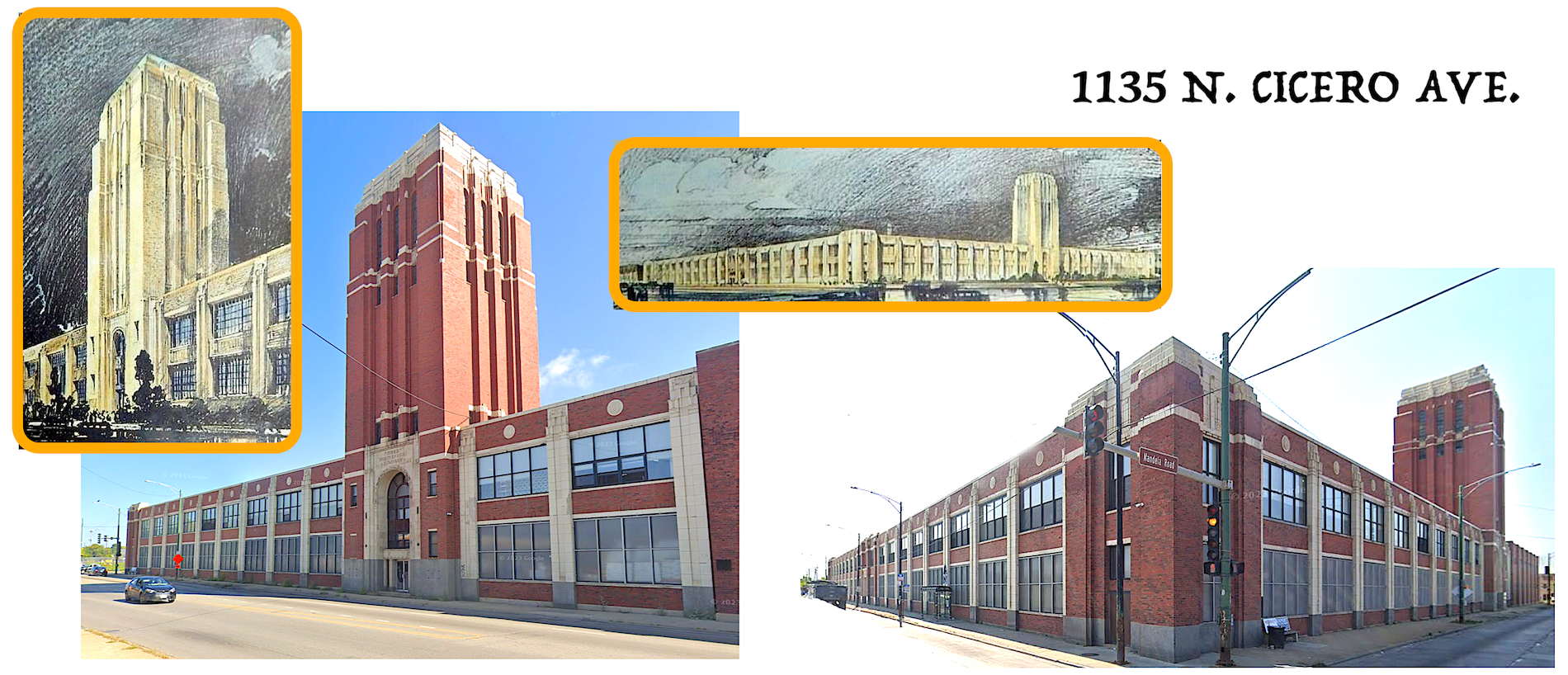

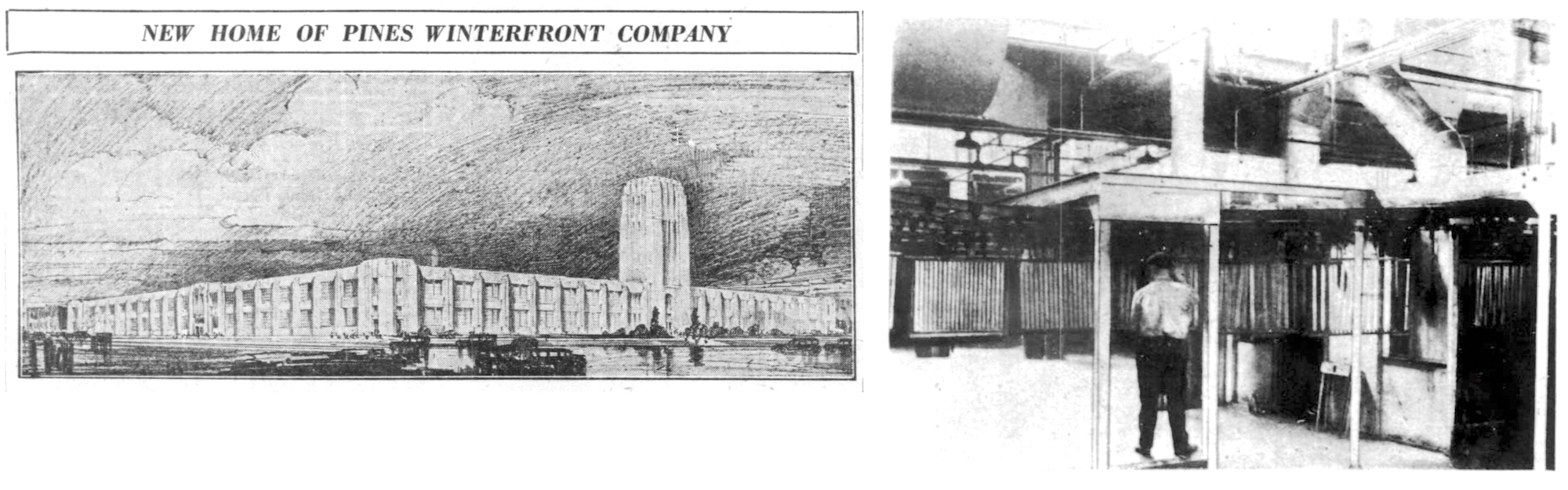

[Then and Now: Artist rendering of the Pines Winterfront Building from 1929, and recent views of the same building in 2023]

The Pines Winterfront building, at 1135 N. Cicero, was opened in 1929 to considerable fanfare. Designed by the architectural firm of Mundie and Jensen, the 190,000 square foot complex is a two-story affair, save for the 120-foot Art Deco central tower (which originally doubled as a water tower) that still looms over the neighborhood.

“Industrial utility and classic beauty have been combined in the new Pines Winterfront structure,” the Chicago Tribune reported at the time. “The tower in front of the building rears itself well above the rest of the edifice and lends to the plant an appearance of artistic architectural achievement.”

When ground was first broken on the factory, early reports estimated a total cost of $1 million for the project, but by the time it was completed, the Tribune noted that its price tag had tripled to $3 million, or about $54 million after inflation. This suggests that Pines Winterfront’s executives may have fallen into the same trap as many of their contemporary manufacturers in the late 1920s, throwing financial caution to the wind after a solid decade of reliable returns. In the end, the Pines Winterfront Company name would remain above the entranceway of its new home for the next century, but the business itself would be gone before it had even settled in.

History of the Pines Winterfront Company, Part I: Raleigh and Pipenhagen

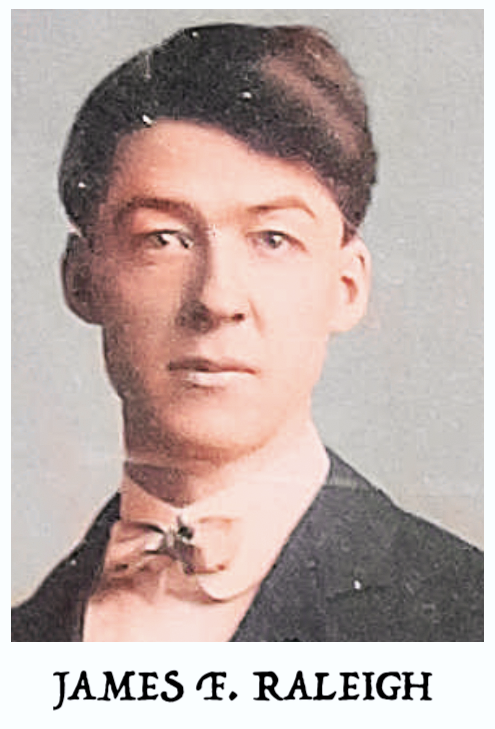

The invention of the Winterfront shutter is generally credited to one man—James Francis Raleigh (1879-1973). But it’s hard to say whether his innovations were born more from an independent streak of brilliance or a brilliant bit of serendipity.

Raleigh was born in Chicago in 1879 to an English father and an Irish mother. By the age of 30, he and his wife Nettie and their son Robert were living in a small home at 4113 W. 21st Place in the Lawndale neighborhood. James was employed as a machinist with the Industrial Manufacturing Company, a tool-making business about three miles up the road at 408 N. Sacramento Avenue. Life was . . . good enough.

Raleigh was born in Chicago in 1879 to an English father and an Irish mother. By the age of 30, he and his wife Nettie and their son Robert were living in a small home at 4113 W. 21st Place in the Lawndale neighborhood. James was employed as a machinist with the Industrial Manufacturing Company, a tool-making business about three miles up the road at 408 N. Sacramento Avenue. Life was . . . good enough.

Raleigh, however, had greater ambitions. Beyond his talents as a metal worker, he also had an inventive mind, and started applying for various patents in the 1910s. One of his inventions, a stamp-affixing machine, was approved by the U.S. patent office in 1913. A year later, he made his first mark on the field of automotive technology, patenting an “engine starter” that claimed to help prevent the common problem of “back-firing.”

It’s certainly logical that Raleigh would have moved on to another engine problem as his next project. But it’s also possible that the radiator guard idea simply fell into his lap.

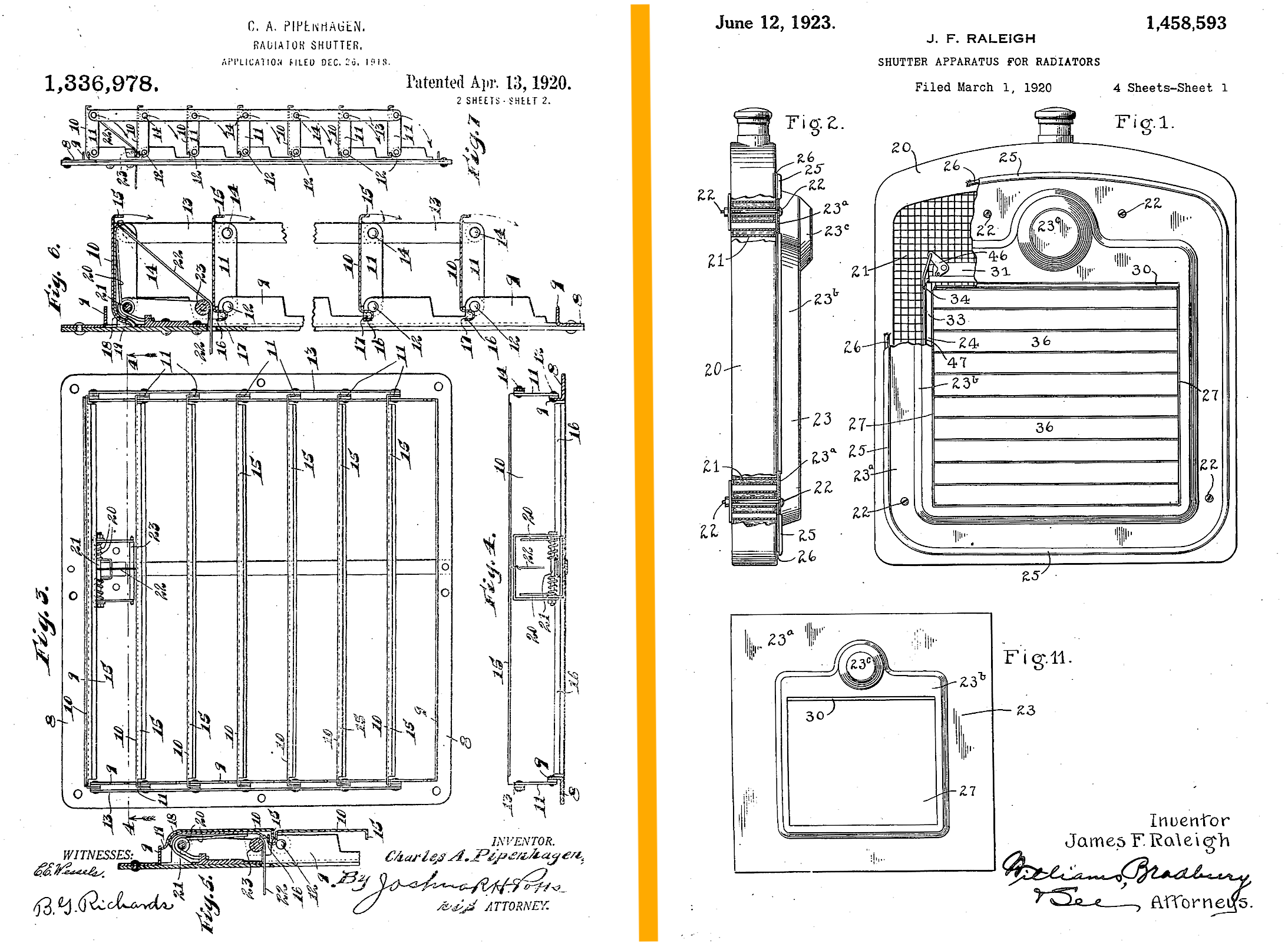

Around 1918 or 1919, while still employed by the Industrial MFG Co., Raleigh crossed paths with a like-minded inventor named Charles A. Pipenhagen (1883-1967). A former hardware dealer with Hibbard, Spencer & Bartlett, the German-born Pipenhagen had recently launched his own Chicago business, the Pines Manufacturing Company*, 56 E. Randolph Street, with the goal of producing some of his own unusual novelty products. So far, that had included a “glass roach trap,” a “jelly bag” strainer, and a “lawn edge trimmer”—none of which had captivated the masses. Like Raleigh, however, Pipenhagen also dabbled in automobile mechanisms, and had applied for a patent on a “radiator-shutter” in 1918 (U.S. patent 1336978A). He’d even introduced his “Pines Radiator Guard” at the 1918 Chicago Auto Show—two full years before Raleigh filed his first such patent.

[Left: Charles A. Pipenhagen’s “Radiator Shutter” design, which he filed for a patent in 1918, and was approved in 1920. Right: J. F. Raleigh’s “Shutter Apparatus for Radiators,” filed in 1920 and approved in 1923. Raleigh’s design is one of the relevant patents listed on the Winterfront shutter in our museum collection, while Pipenhagen’s is not.]

So, did Pipenhagen introduce Raleigh to the idea of such a device, or did Raleigh—already hard at work on the problem himself—seek out the like-minded Pipenhagen for a chat? Sadly, those details are lost to time. What we do know is that the two middle-aged men—rather than seeing each other as rivals—were willing to work together, with Pipenhagen soon taking on Raleigh as a new partner in the Pines MFG Co.

As part of their agreement, Pipenhagen also contracted out the manufacturing of all Pines radiator guard devices to Raleigh’s previous employer, the Industrial MFG Company, on Sacramento Blvd. Everyone involved seemed to recognize the significant potential of this new invention to transform the fortunes of all involved.

By 1920, Raleigh had applied for his own patent on an improved radiator guard, combining his own ideas with elements from Pipenhagen’s work. This design would be branded under Raleigh’s chosen product name, the Winterfront, but also carry the Pines manufacturing name, hence, the Pines Winterfront. The new patent wouldn’t get approval for another three years, but the buzz within the auto industry had already grown exponentially in the interim.

By 1920, Raleigh had applied for his own patent on an improved radiator guard, combining his own ideas with elements from Pipenhagen’s work. This design would be branded under Raleigh’s chosen product name, the Winterfront, but also carry the Pines manufacturing name, hence, the Pines Winterfront. The new patent wouldn’t get approval for another three years, but the buzz within the auto industry had already grown exponentially in the interim.

Raleigh’s “thermostatically operated radiator shutter” was described in a 1920 issue of the Auto Trade Journal as a “new product of great use to the automobilists in the winter. . . . The device has the drawn steel shell made to closely fit over the core of the radiator and retained by four bolts through the radiator. A braided cord edging is used to form a protecting cushion between the two. The shutters are made of very smooth steel and are ribbed to give strength. The shutter axles or trunnions are turned brass and operate in composition bearings. The thermostat is located in the upper portion of the drawn steel shell or frame and is connected by means of rods and levers with the shutters.

“The thermostat consists of a pair of wafer cells, a spacer and an aluminum heat conducting flange or plate. The thermo water cells are spring bronze and filled with a mixture of liquid gasses proportioned to make the cells expand and contract at the desired temperature. The operation is entirely automatic, the shutters opening as the heat rises above 130 degrees Fahrenheit and closing when it falls below.”

Okay, so maybe describing the Pines Automatic Winterfront as a “simple solution” to engine troubles is a bit of an oversimplification in its own right. But James Raleigh seemed to know that the narrative, from a marketing perspective, mattered more than the mechanical details.

“After the causes of motor wear were known,” Raleigh wrote in a 1927 article in the Chicago Tribune, “it became a simple matter to remedy it, and the success of this remedy is the reason why cars are now operated during the coldest winter days in large numbers. The remedy found was to prevent the cold air from entering the motor until the motor was warm enough to operate satisfactorily. This was accomplished by an automatic radiator protection device which covers the radiator front until the engine is hot enough and then automatically opens.”

II. The Season of Winterfront

Within a year of the Winterfront earning its patent in 1923, the Pines MFG Co. had absorbed the Industrial MFG Co. and become the Pines Winterfront Company. Its manufacturing capacity had also been maxed out, requiring the acquisition of more space down the street at 430 N. Sacramento Blvd.

“Dealers’ sales have developed from a modest beginning in 1919 to over $3 million in the season of 1924-25,” a company advertisement claimed. “The present factory, devoted almost exclusively to the manufacture of the WINTERFRONT, has a frontage of 225 feet by 130 feet deep, two stories, and is equipped with latest machinery to insure a product of uniformly high quality and in quantity to take care of the seasonal requirements of the trade.

“Dealers’ sales have developed from a modest beginning in 1919 to over $3 million in the season of 1924-25,” a company advertisement claimed. “The present factory, devoted almost exclusively to the manufacture of the WINTERFRONT, has a frontage of 225 feet by 130 feet deep, two stories, and is equipped with latest machinery to insure a product of uniformly high quality and in quantity to take care of the seasonal requirements of the trade.

“The WINTERFRONT is indeed an article which we are proud to make and which every dealer can be even more proud to sell.”

Part of the reason for the steady growth of the business was an early realization about its target audience. According to an interview that company chairman Charles Pipenhagen gave to Printer’s Ink magazine in 1927, it became clear that drivers of lower-cost automobiles were less likely to pay for a Winterfront, as they were satisfied to buy a much cheaper leather or fabric radiator cover to do the same job, albeit with inferior performance.

“It was something of a disappointment to realize that we were not going to be able to touch the big mass market,” Pipenhagen said. “Nevertheless, we followed a policy which I believe now has proved better for us.”

That policy essentially involved ignoring the low-priced car market in favor of the higher class—which at the time meant cars selling for $3,000 or more. Owners of these vehicles were more willing to pony up for the best quality radiator cover, and with a growing middle class—and a monopoly on its niche product—Pines Winterfront saw its sales soar.

[Left: Company chairman Charles A. Pipenhagen showing off the Pines Automatic Winterfront at an industry convention in 1926. Right: The rusty example from our museum collection.]

The year 1928, in particular, was a huge one for the business, as Pines had now arranged deals to install their shutters as built-in equipment on some of the top-selling high-end models of the period, including the Hupmobile 8, Chrysler 75, Chrysler Imperial, Dodge Senior Six, Graham-Paige, Stearns Knight, Stutz, Jordan, Gardner 130, Cadillac, La Salle, Pierce-Arrow, and Lincoln. Importantly, by the end of that year, the nation’s leading car manufacturer, the Ford Motor Company had also started talks with Pines.

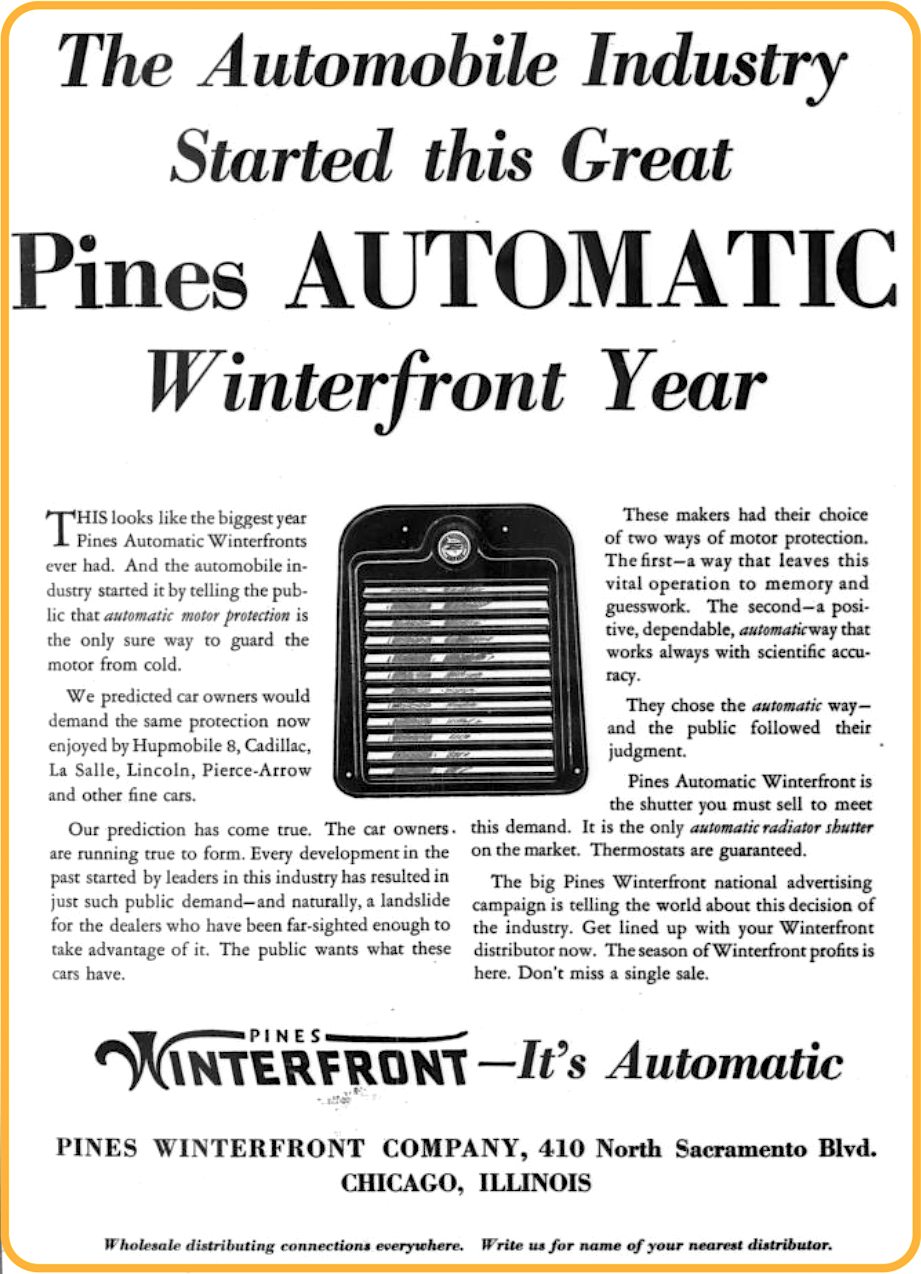

“Our prediction has come true,” read a 1928 Pines-Winterfront ad in the Motor Age trade magazine. “The car owners are running true to form. Every development in the past started by leaders in this industry has resulted in such public demand—and naturally, a landslide for the dealers who have been far-sighted enough to take advantage of it. The public wants what these cars have. . . . Pines Automatic Winterfront is the shutter you must sell to meet this demand. It is the only automatic radiator shutter on the market. The season of Winterfront profits is here. Don’t miss a single sale.”

It’s easy to understand, then, why Jim Raleigh and Charles Pipenhagen saw nothing but glory in their immediate future. And thus, they went ahead with the ambitious investment into their new dedicated mega-plant in Humboldt Park, complete with the giant tower subtly designed in the style of the Winterfront screen itself.

It’s easy to understand, then, why Jim Raleigh and Charles Pipenhagen saw nothing but glory in their immediate future. And thus, they went ahead with the ambitious investment into their new dedicated mega-plant in Humboldt Park, complete with the giant tower subtly designed in the style of the Winterfront screen itself.

“Our entire plant has been laid out,” Raleigh told the Tribune ahead of the new factory’s opening in 1929, “to increase the quantity production on a scale that will meet with out constantly increasing demand for built-in radiator shutter equipment, which we expect to be universally used in automobiles in the not far distant future. . . . Our [Belt Line] railroad facilities will give us service to every line in Chicago every thirty minutes if necessary.”

The tower portion of the new building housed the 70,000 gallon water tower for the modern sprinkling system, as well as storage rooms and offices for executives. The ground floor of the rest of the complex included all of Pines’ machinery, tooling, and manufacturing equipment, while the second floor housed offices, finishing and plating rooms, and a laboratory for experimental work. Raleigh also informed the Tribune that the factory would also have “its own hospital and its own staff of physicians and nurses, as well as a restaurant and lounge room for employees.” Some of these more luxurious services, however, may not have lasted long. By the end of 1929, the economic outlook for Pines Winterfront, its new factory, and the rest of American business, had changed dramatically.

[The Pines Winterfront factory was a modern marvel, including the efficiency of its material-handling equipment, as discussed in a 1930 issue of the American Machinist, from which the photo on the right was sourced. “An overhead monorail system carries the pressed steel parts successively through the washer, dryer, and spray booths; then rack-type trucks bring the parts to the ovens and propel them mechanically through.”]

III. Winterfront Freezes Over

“This winter give your car and yourself a break. Avoid coughing starts, long warm-up periods, a frozen radiator, a heater that won’t heat. Anti-freeze solution only prevents water from freezing solid; it does not warm the water. Neither does a thermostat. That is the Winterfront’s job—and it does it properly, scientifically.” —Pines Winterfront newspaper ad, 1937

In the summer of 1931, in just the company’s second year in its new enormous headquarters on Cicero Avenue, chairman Charles Pipenhagen made a brief speech at the Pines Winterfront company convention, discussing his optimism about new products that the firm was rolling out.

In the summer of 1931, in just the company’s second year in its new enormous headquarters on Cicero Avenue, chairman Charles Pipenhagen made a brief speech at the Pines Winterfront company convention, discussing his optimism about new products that the firm was rolling out.

“The new items, the battery fillers and turn signals, were enthusiastically received at the dealers’ convention and the initial orders placed indicate that the sales volume for the immediate future will substantially exceed the estimate originally made by us,” Pipenhagen told his employees and distributors.

In the midst of the Great Depression, though, many workers had come to recognize the difference between wishful thinking and genuine good news. In reality, Pines Winterfront wasn’t finding much success expanding beyond its one flagship product, and the crippling costs of running its factory were undercutting its efforts to stay afloat during the economic crisis.

By 1933, frustration and infighting among Pines shareholders led to a radical shake-up of the business’s leadership. Pipenhagen, Raleigh, and most of the other directors of the company announced their “retirement” that summer, and a completely new braintrust was brought in to try and protect the freezing engine of the Pines Winterfront Company.

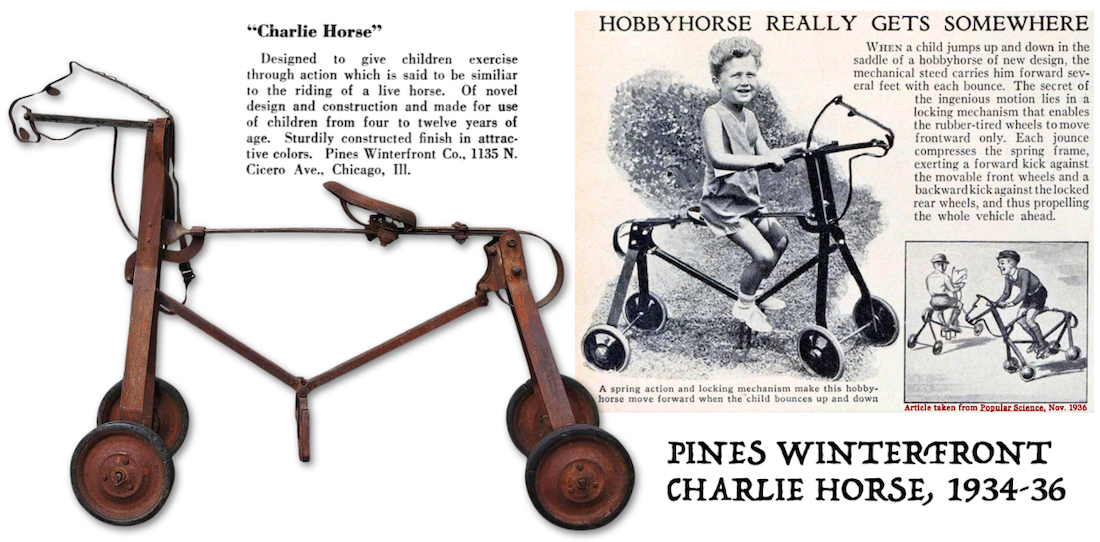

New president William O’Neill, formerly of the Stromberg Carburetor Company, tried to turn over any stone possible to make effective use of Pines’ resources. In 1934, for example, the company suddenly started marketing a random line-up of children’s toys, including a four-wheeled “Charlie Horse” (for ages 4-12) that was supposed to simulate the experience of riding a real horse. It didn’t catch on.

By 1935, O’Neill saw doom on the horizon and resigned, as well, leaving Pines Winterfront limping through the last few years of the 1930s, switching up management several more times while still clinging to the last bits of its marketshare with the old reliable Winterfront shutters.

Finally, in 1940, the company’s remaining shareholders agreed that the inevitable time had arrived. The radiator guard line was sold off to the Sheller Manufacturing Company, and the Pines Winterfront Company was effectively dissolved, citing “continuing operation losses and exhaustion of working capital.” A subsequent two-day auction cleaned out the Cicero Avenue building, which was then supposedly sold to the U.S. Army for about $500,000, or less than 1/6 of its building costs. It would become a wartime plant of the Honeywell Corporation through 1944.

In 1945, Leaf Brands, Inc.—of gum and baseball card fame—moved into the factory, occupying it for the next 40 years. Interestingly, though, Leaf never bothered replacing the Pines Winterfront signage over the doorway of the tower building, and even through decades of subsequent boarded-up deterioration, the sign has remained.

In 1945, Leaf Brands, Inc.—of gum and baseball card fame—moved into the factory, occupying it for the next 40 years. Interestingly, though, Leaf never bothered replacing the Pines Winterfront signage over the doorway of the tower building, and even through decades of subsequent boarded-up deterioration, the sign has remained.

As for the two heroes of our story . . . James F. Raleigh went on to serve as the president of the Underwood Electric Company in the 1940s and Webster Chicago / Webcor in the 1950s. He died in 1973. Charles Pipenhagen led the Capson Manufacturing Company, a metal specialties business, for the rest of his career. In his 1967 obituary in the Chicago Tribune, Pipenhagen is credited with “developing the automatic radiator shutter for autos.” For the sake of semi clarity, though, it is Raleigh’s 1920 patent number—rather than one of Pipenhagen’s—that appears on the Winterfront in our museum collection.

[One of Pines products that pre-dated the Winterfront: the Pines Lawn Edge Trimmer, 1916]

Sources:

“Pines Radiator Shield” – Motor Age, Jan 31, 1918

“Thermostatically Operated Radiator Shutter” – Automobile Trade Journal, Jan 1, 1920

“40,000 Shares – Pines Winterfront Company (ad)” – Chicago Tribune, March 12, 1924

“Pipenhagen, Charles Albert” – Who’s Who in Chicago, 1926

“75 Percent of All Motor Trouble Laid to Winter Operation” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 30, 1927

“When the Seasonal Slump Can’t Be Avoided, Minimize It” – Printer’s Ink, May 19, 1927

“Recognition for Pines Winterfront is Becoming More Industry-Wide” – Automotive News, Nov 14, 1928

“Four Times Present Space in Proposed Pines Co. Plant” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 27, 1929

“Weatherproofing Winterfronts” – American Machinist, May 22, 1930

“Distributors Attending the Pines Winterfront Company Convention” – Detroit Free Press, June 20, 1931

“Pipenhagen Resigns from Pines Winterfront” – Automotive Daily News, April 25, 1933

“Pines Revises Its Executive Staff Set Up” – Automotive Daily News, June 14, 1933

“Pines Winterfront Plans Dissolution” – Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 26, 1940

“Pines Winterfront Business to Sheller” – Detroit Free Press, July 14, 1940

“Complete Two Day Auction at Pines Winterfront Co.” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 16, 1940

“Pipenhagen, 84, a Retired Inventor, Dies” – Chicago Tribune, May 12, 1967

“Ask Geoffrey: What Became of Artist Behind These 1970s Murals” – News.WTTW.com – Dec 12, 2018