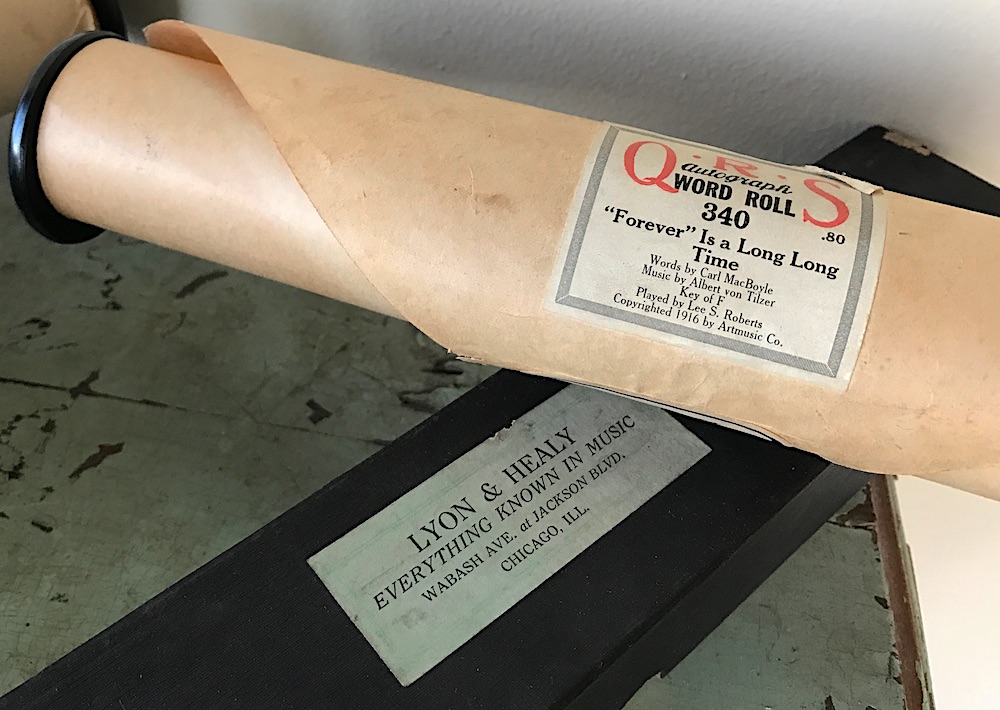

Museum Artifacts: QRS Player Piano “Autograph Word Roll” #340 – “Forever is a Long Long Time,” 1916

Made By: The Q-R-S Company, 412 Fine Arts Building – Factory at 4829 S. Kedzie Ave.[Brighton Park]

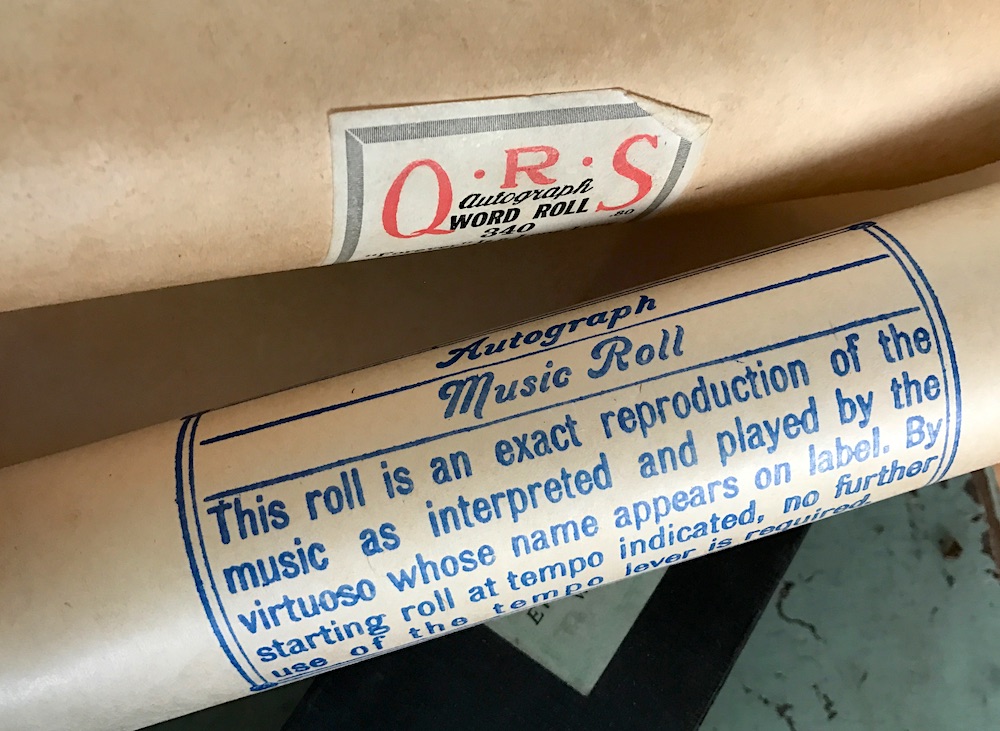

“Up to the advent of the Q-R-S Autograph Roll all player piano music rolls were much alike—all made the same mechanical way. . . The Q.R.S. Autograph Music Roll is hand played—it is practically a photographic record of the hand playing of an artist. And its playing on your instrument is identical with the manual playing of the artist who made it in the first place. The leading pianists of the country are represented on Q-R-S Autograph Music Rolls with all their individuality faithfully recorded.” —Q-R-S advertisement, 1913

The self-playing piano, aka the “player piano,” “reproducing piano,” or “pianola,” is certainly an endangered species of the musical kingdom these days—a novelty often relegated to kitschy hotel lobbies or shopping mall food courts. The appealing weirdness and wonder of these mechanical instruments, however, is almost uniquely unchanged across 100+ years. Even a kid raised on Youtube and Spotify can find themselves momentarily mesmerized by the sight and sound of 88 untouched keys bobbing up and down with harmonious precision—seemingly at the hands of an invisible man.

The self-playing piano, aka the “player piano,” “reproducing piano,” or “pianola,” is certainly an endangered species of the musical kingdom these days—a novelty often relegated to kitschy hotel lobbies or shopping mall food courts. The appealing weirdness and wonder of these mechanical instruments, however, is almost uniquely unchanged across 100+ years. Even a kid raised on Youtube and Spotify can find themselves momentarily mesmerized by the sight and sound of 88 untouched keys bobbing up and down with harmonious precision—seemingly at the hands of an invisible man.

That uncanny combination of magic and mechanization—the proverbial ghost in the machine—was all the more gobsmacking to folks in the early 1900s, when radios and record players (let alone televisions) were still a little ways down the road. Back then, the player piano became a surprisingly mainstream form of household entertainment—a major investment, to be sure, but popular enough in middle class parlor rooms to support an enormous industry; much of it centered in the established piano-manufacturing hub of Chicago.

The Q-R-S Music Company was born out of this relatively brief but intense phenomenon, becoming the world’s largest producer not of player pianos, but player piano rolls—the perforated paper sheets that “fed” the instrument its precise musical instructions. To some, QRS and its ilk were purveyors of soulless “machine music,” but to others, they were miracle workers of the modern age—bottling and preserving the note-by-note performances of very real human beings, including everyone from George Gershwin and Sergei Rachmaninov to Jelly Roll Morton and Fats Waller.

History of the QRS Company, Part I. The Artifact

The artifact in our museum collection is a fairly random but representative example of a QRS piano roll from the company’s early Chicago era. It contains a punch-hole interpretation of the song “Forever is a Long, Long Time,” a new composition by “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” scribe Albert von Tilzer. The tune was copyrighted in 1916 and likely recorded and released a year or two later.

Branded as an “Autograph Word Roll” (No. 340), our particular unraveled scroll features the piano stylings—and literal stamped autograph—of Lee S. Roberts (1884-1949), a prolific songwriter and piano roll recording artist who also happened to be the vice president of the QRS Co.

“I had no intention of becoming a pianist or composer,” Roberts said in 1921. “I owe all my achievement and success in that direction to the influence of the player [piano] and the extensive amount of musical literature with which it surrounded me.”

As just one of millions of tuneful tubes churned out by the company during its pre-Depression heyday, this edition of “Forever is a Long Long Time” would have been copied from an initial “master roll”—created directly from Lee Roberts performing the song on a special “marking piano,” likely in one of the QRS offices in Chicago, San Francisco, or New York. According to Brian Dolan’s 2009 book Inventing Entertainment: The Player Piano and the Origins of an American Musical Industry, “the marking piano was designed so that each time a key was played, its associated stylus struck a roll of paper that rolled over a carbon cylinder, leaving a mark—note on, note off—on the reverse of the paper. Each of these marks would then be punched, creating the music roll.”

As just one of millions of tuneful tubes churned out by the company during its pre-Depression heyday, this edition of “Forever is a Long Long Time” would have been copied from an initial “master roll”—created directly from Lee Roberts performing the song on a special “marking piano,” likely in one of the QRS offices in Chicago, San Francisco, or New York. According to Brian Dolan’s 2009 book Inventing Entertainment: The Player Piano and the Origins of an American Musical Industry, “the marking piano was designed so that each time a key was played, its associated stylus struck a roll of paper that rolled over a carbon cylinder, leaving a mark—note on, note off—on the reverse of the paper. Each of these marks would then be punched, creating the music roll.”

In essence, then, the piano roll captured Roberts’ personal rendition of “Forever is a Long Long Time” like a photograph—or maybe more like a slightly doctored photo, as edits and alterations were also part of the manufacturing process.

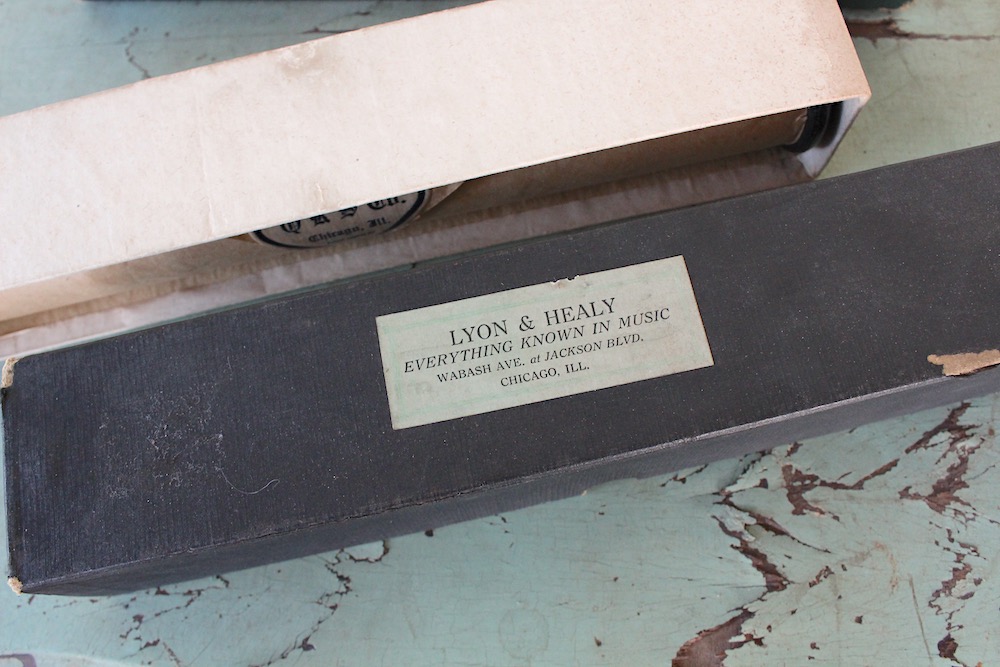

Once that master roll found its way to the QRS manufacturing plant, a perforating machine could follow its pattern to produce hundreds of identical copies, which would then be distributed to retailers across the country, including the reputable Chicago music dealer Lyon & Healy, who boxed and sold our specific museum artifact.

From there, at the average cost of 25 or 50 cents ($6 to $12 in today’s money), a customer would have picked up this hot new jam of 1916 and eagerly brought it home to play for the family.

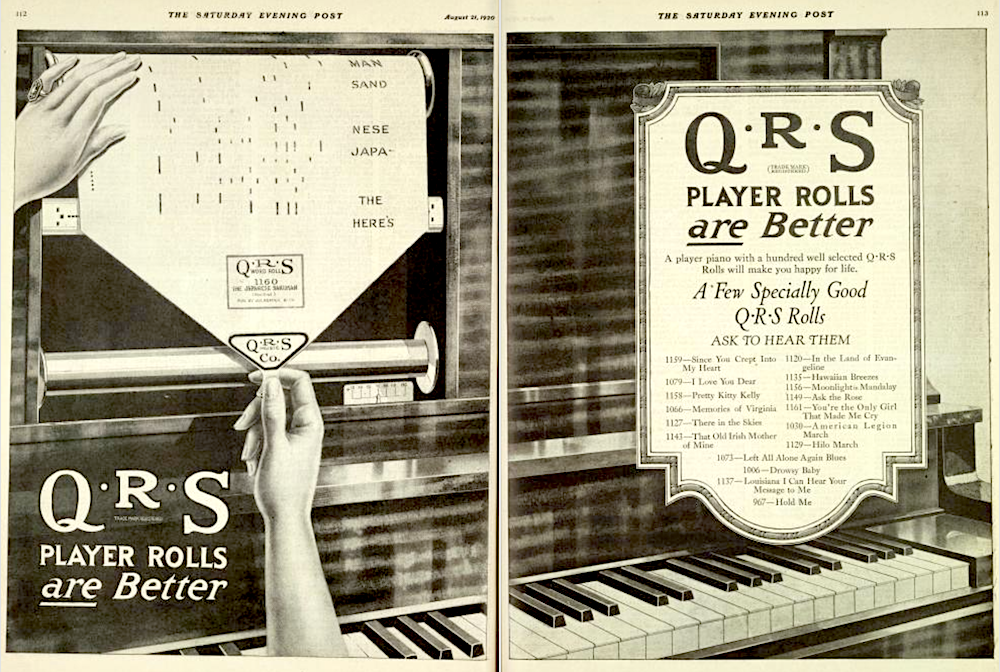

Most player pianos had a built-in compartment centered above or below the keyboard, where the roll (wrapped around a spool) could be inserted into the player mechanism, or “stack.”

“As the paper is fed through the player piano,” according to noted piano roll transcriber Artis Woodhouse, “it is read by the player mechanism, which trips the piano hammers to strike the strings. The position of holes along the width of the roll determines the pitch of the note, the position of holes along the length of the roll determines when in time the note occurs, and the length of the holes determines how long the notes are held.” This amazing mechanism functioned on pneumatic principles, with pushed air moving through the holes in the paper and back through various valves and bellows to communicate its intended sound.

“As the paper is fed through the player piano,” according to noted piano roll transcriber Artis Woodhouse, “it is read by the player mechanism, which trips the piano hammers to strike the strings. The position of holes along the width of the roll determines the pitch of the note, the position of holes along the length of the roll determines when in time the note occurs, and the length of the holes determines how long the notes are held.” This amazing mechanism functioned on pneumatic principles, with pushed air moving through the holes in the paper and back through various valves and bellows to communicate its intended sound.

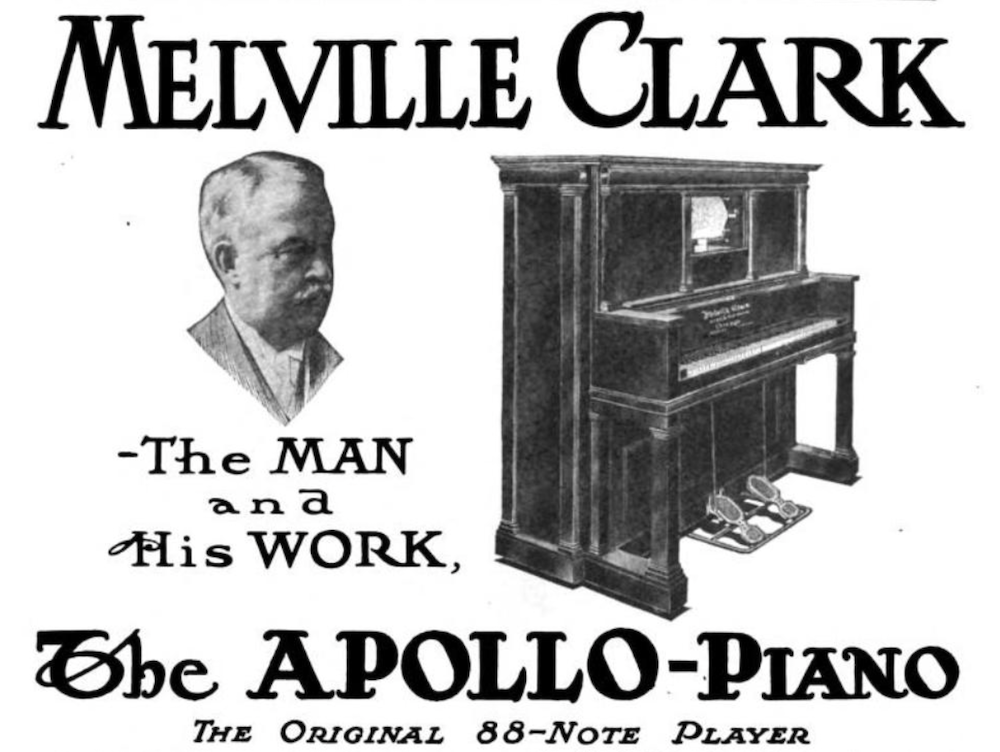

Some of the early pianolas and player pianos were rightly criticized for a clunky, stilted playing style that fell far short of recreating the subtle art of the human hand. New improvements in the technology began rapidly upgrading the simulation in the early 1900s, however; many of them credited to the work of a man named Melville Clark, a Chicago based inventor and manufacturer who—conveniently enough—is also generally recognized as the founder of QRS.

Part II: Clark’s Story

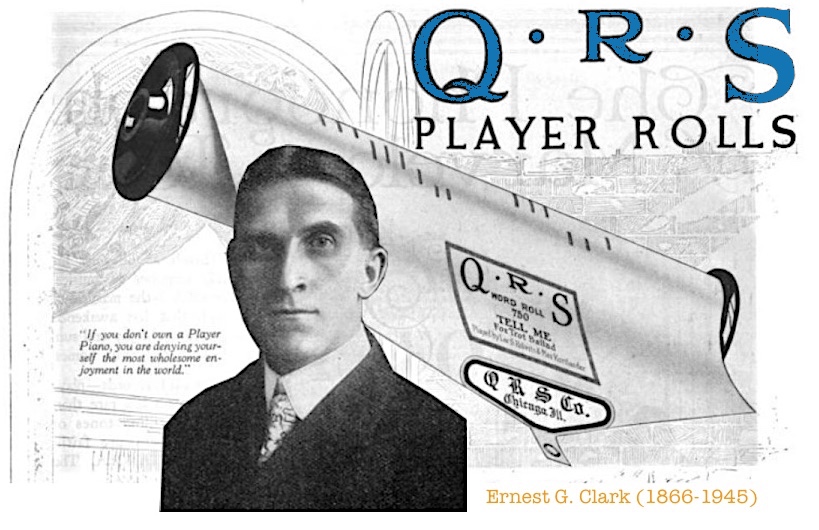

A native of Oneida County, New York, Melville Clark (b. 1848) came from a family of artisans and craftsmen. His father Thomas Clark was a picture frame maker, his older brother George Waldo Clark ran a music store in Syracuse, and his younger brother Ernest G. Clark would eventually lead the QRS music roll team and the Clark Orchestra Roll Company. Melville even had a famous nephew of the same name—George’s son Melville A. Clark (b. 1881)—who ran his own separate instrument business in Syracuse (the Clark Music Co.) and found great success as the inventor of the Clark Irish Harp; the first portable string harp.

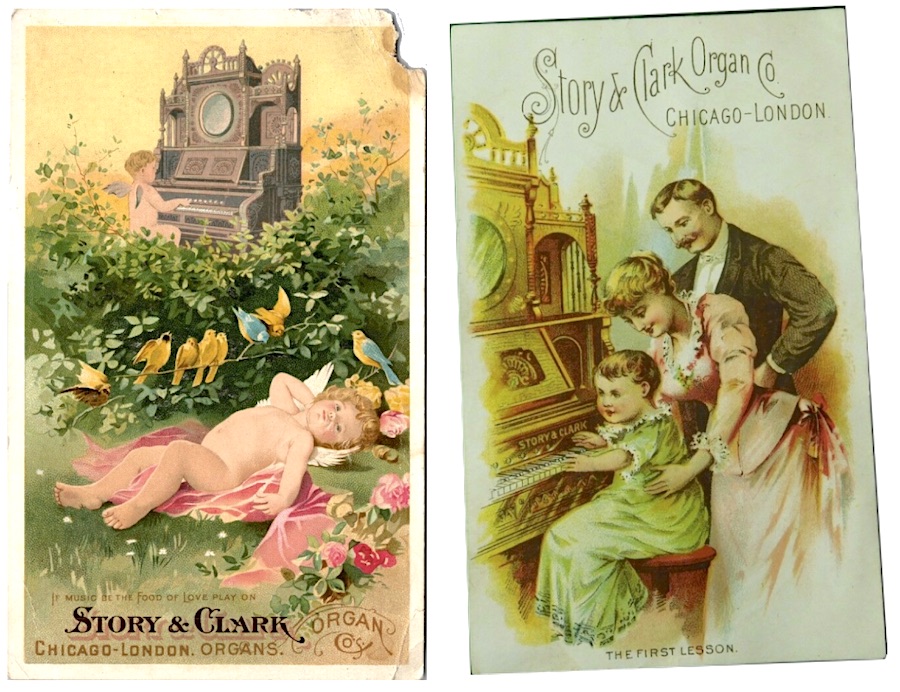

The “original” Melville Clark, meanwhile, always kept his focus on keyboard instruments. Starting out as a piano tuner and organ builder in Syracuse, he made a bold move to the west coast in 1875 to organize his first business (Clark & Co., Oakland, CA); then relocated to Chicago, where he ultimately joined up with Hampton L. Story to form the famed Story & Clark Company in 1884. S&C was initially an organ manufacturer, but the company began producing pianos in the 1890s, and their reputation was stellar from the outset; particularly in regards to the innovative chops of Melville Clark.

“There is probably not a single manufacturer in the country who has a superior personal knowledge of mechanism and principles of musical instrument manufacture than Mr. Clark,” one trade journal proclaimed in 1891, “and certainly no man whose brain is more fertile in the originating of improvements.”

[Victorian collector cards advertising the Story & Clark Company, circa 1890]

After traveling to Europe in the early 1890s and observing new developments in mechanized self-playing “pianolas,” Melville returned to Chicago with a new obsession—one well suited to the inventive spirit of the Columbian Exposition.

Everybody liked listening to a good piano tune, he figured, but a relative few had the skill and patience to play the instrument at a high level. The player piano met the public halfway; serving both as a highly advanced “music box” and an educational tool for prospective pianists and visual learners.

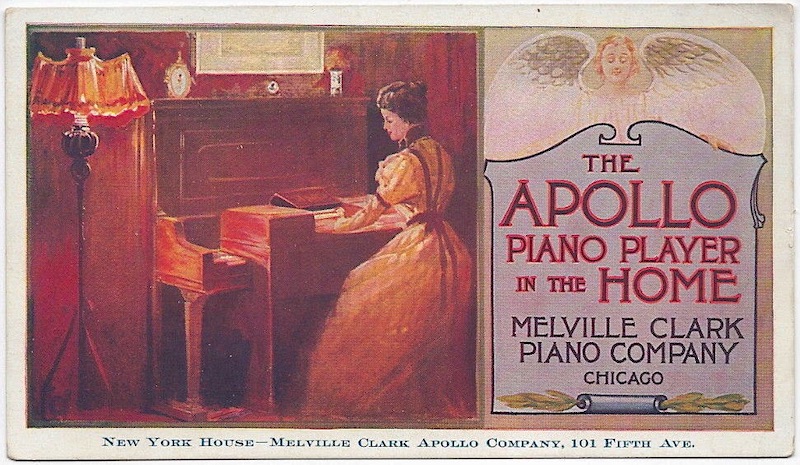

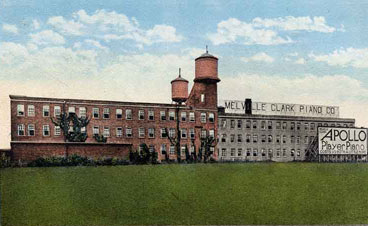

Finally, in 1900, Melville elected to “go solo,” as it were, respectfully parting ways with Story and forming an entirely new enterprise built around his latest inventions: the Melville Clark Piano Company. As one of the preeminent piano men in the country, this made for big news not just in the highly competitive Chicago market, but across the industry.

“One of the most important happenings of the week in this city has been the organization of the Melville Clark Piano Co. and the divorce, after sixteen years of close association, of the interests controlled by Melville Clark and the Storys,” the Music Trade Review reported on February 17, 1900. “. . . It is the intention of the Melville Clark Piano Co. to make the Clark piano an instrument of high grade, and which by reason of Mr. Clark’s scientific ability and prestige, as well as the quality of its manufacture, will command a special position in the field.”

From its first plant on West Madison Street, the Melville Clark Company soon had 150 men and women in its employ. Many were working to produce the world’s first mechanized, 88-note upright piano with a built-in player mechanism; a Clark invention that he dubbed the “Apollo” (previous options on the market were usually limited to 65 notes). Rather than using a vacuum motor to run the music rolls—as was common in other models—the Apollo used a spring-wound clockwork motor that was wound by pumping the piano’s pedals. Later models required no human guidance at all, a factor which differentiates a “reproducing piano” from a standard player piano.

From early on, a department was also established within the Melville Clark plant for recording and manufacturing a new line of paper piano rolls that would work exclusively with the Apollo. Likely for legal reasons, Melville elected to make this roll department a separate company unto itself, and installed his highly capable younger brother Ernest G. Clark as the first president of the new subsidiary, which would be known—somewhat inexplicably—as the Q-R-S Company.

III. It Ain’t an Acronym

While advertisements would later suggest that the three letters stood for “Quality Real Service,” the actual origin of the name Q-R-S remains something of a mystery. One theory is that the mail department at the Melville Clark Company was overrun with roll orders, filed under “R,” and that workers had to utilize the adjacent “Q” and “S” pigeon holes on either side. Another article in a company bulletin in 1918 (suggesting the origin of the name had already been lost by that point) guessed that maybe the letters had been a reference to “arousing people’s Q-R-oSity.” Ugh, hope not.

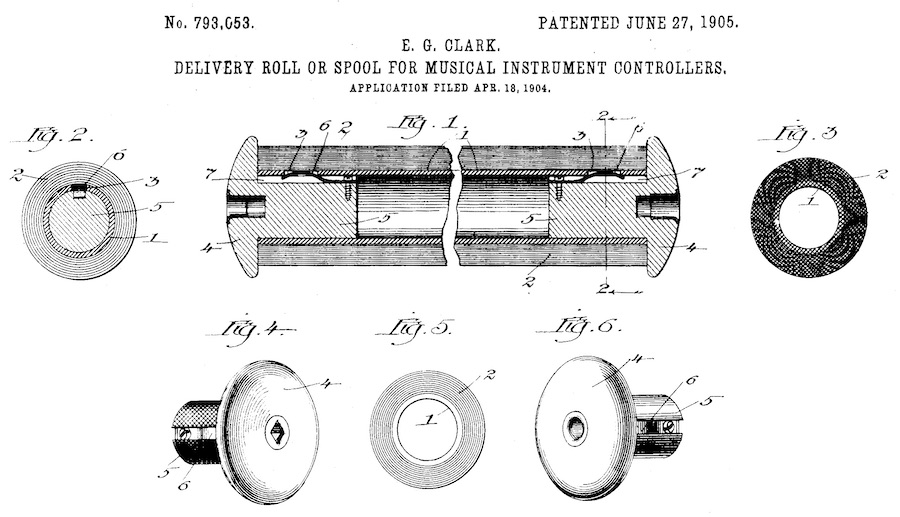

Whatever the inspiration, the QRS Company remained little more than a wing of the Melville Clark Co. through the first decade of the 1900s, although Ernest Clark was proving just as mechanically savvy as his older brother, eventually collecting more than a dozen patents related to the construction and use of perforated music rolls.

[An early Ernest G. Clark patent for a “delivery roll or spool for musical instrument controllers,” 1905. While Ernest was 18 years younger than his brother Melville and routinely overshadowed, his inventions were just as important to the success of both the Apollo pianos and QRS rolls]

Most of Ernest’s new creations were put into use in a major new factory that the Clark Company and QRS established in DeKalb, Illinois; a railroad-friendly town about 60 miles west of Chicago.

At the grand opening of the DeKalb plant in 1905, Melville Clark told reporters he expected to be able to produce 2,500 traditional pianos and as many as 4,000 player pianos per year. These were mighty ambitious goals for an upstart company competing against numerous rivals in a brand new field, but some key developments over the next few years validated Clark’s confidence.

First, in 1907, Clark was victorious in a high-profile court case that rocked the industry. Ruling in White-Smith Music Publishing Co. vs. Apollo Company, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that music roll makers didn’t have to pay royalties to composers, as the rolls were deemed to be part of a machine, rather than clearly identifiable copies of copyrighted sheet music. This case became surprisingly relevant many decades later, when similar lawsuits emerged around computer program coding.

The next big win for Clark and QRS came a year later, in 1908, when a piano manufacturers convention in Buffalo, New York, concluded with the 88-note piano roll being officially adopted as the industry standard format, validating Melville’s design and sending many of the early 65-note pianola purveyors to their doom.

In the long run, standardization was a victory for the whole industry, as the public no longer had to fret about which various roll formats would work in which pianos. This convenience, and the emergence of a booming ragtime dance craze, led to exponential sales growth. In 1909, an estimated 45,000 player pianos were sold in the country, and by 1919, that tally had more than quadrupled to 208,000 units sold—loosely mirroring the growth in automobile sales during the same decade. To put it in another context, an estimated 85% of all pianos sold in the U.S. between 1910 and 1925 were “automated,” with at least some mechanical accompaniment built in.

For an instrument we now think of as a pure novelty, it can be hard to wrap our 21st century heads around those numbers, especially when you consider that even a low-end player-piano in the 1910s was selling for $300-$500; about the same as a Model T Ford, and equivalent to roughly $5,000 to $8,000 in today’s money. The surprising popularity of these big expensive machines only really makes sense against the stark absence of viable music-listening alternatives.

Yes, the phonograph existed in 1910—in a pre-electric state—but the snaps, crackles, and fuzzy distortion we associate with those old recordings was also part of the original listening experience; a symptom of an infant technology. This meant that—outside of becoming an accomplished musician or hiring one—there was no way to enjoy the true sound of skillfully played music within the home.

Yes, the phonograph existed in 1910—in a pre-electric state—but the snaps, crackles, and fuzzy distortion we associate with those old recordings was also part of the original listening experience; a symptom of an infant technology. This meant that—outside of becoming an accomplished musician or hiring one—there was no way to enjoy the true sound of skillfully played music within the home.

A player piano offered a new hope . . . not a rough recording cranked out through a horn, but a genuine performance physically communicated through the hammers and keys of the piano itself—close to how it might sound with a capable person tickling the ivories. Young musicians could also use the piano rolls as accompaniment while they honed their own skills, and struggling composers could find a new audience with greater ease than merely selling their unheard sheet music on street corners.

Better still, just about any popular song under the sun could be added to your own personal concert collection simply by picking up the latest QRS piano roll at your local music shop. There was rarely a shortage, as the QRS plant in DeKalb was boxing up about 4,000 rolls per day by 1912.

[Factory workers at the Melville Clark / QRS plant in DeKalb, IL, c. 1915, courtesy of DeKalb Daily Chronicle]

IV. Soul of the Performer

“Q-R-S Player Rolls are made from the ‘master patterns’ which are recorded from the hand playing of great pianists. Expense is not spared in making Q-R-S ‘masters.’ No pianist is too prominent—no fee too large to pay for the sake of getting out a Q-R-S Roll that is up to our quality standard.” —QRS Company ad, 1919

In 1912, Melville Clark made arguably his biggest contribution to the music industry, inventing the QRS Marking Piano (aka the Apollo Marking Piano)—the vehicle through which a live pianist could directly mark each note he hit onto a carbon cylinder as he played. Before this, QRS master rolls were generally hand-punched by draftsmen using rulers to simulate the spacing of a keyboard, leading to a lot of the problems with stilted playback. This new innovation* was a major game changer for “natural” sound recording, and was later described by music historian Alfred Dodge as doing “more than the phonograph and photographic camera combined, because it reproduces the soul of the performer.”

*In 1992, 80 years after its invention, the QRS Marking Piano was named an official “National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark” by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

After the development of the marking piano, some of the best known and respected pianists in the world—including many who’d once been skeptical of automatic instruments— were increasingly willing to join the music roll revolution and cut their own cylinders. Even the great Sergei Rachmaninoff, upon listening back to his own first piano roll recording in 1919 (for the American Piano Company, a QRS rival), supposedly said, “Gentlemen, I, Sergei Rachmaninoff, have just heard myself play!”

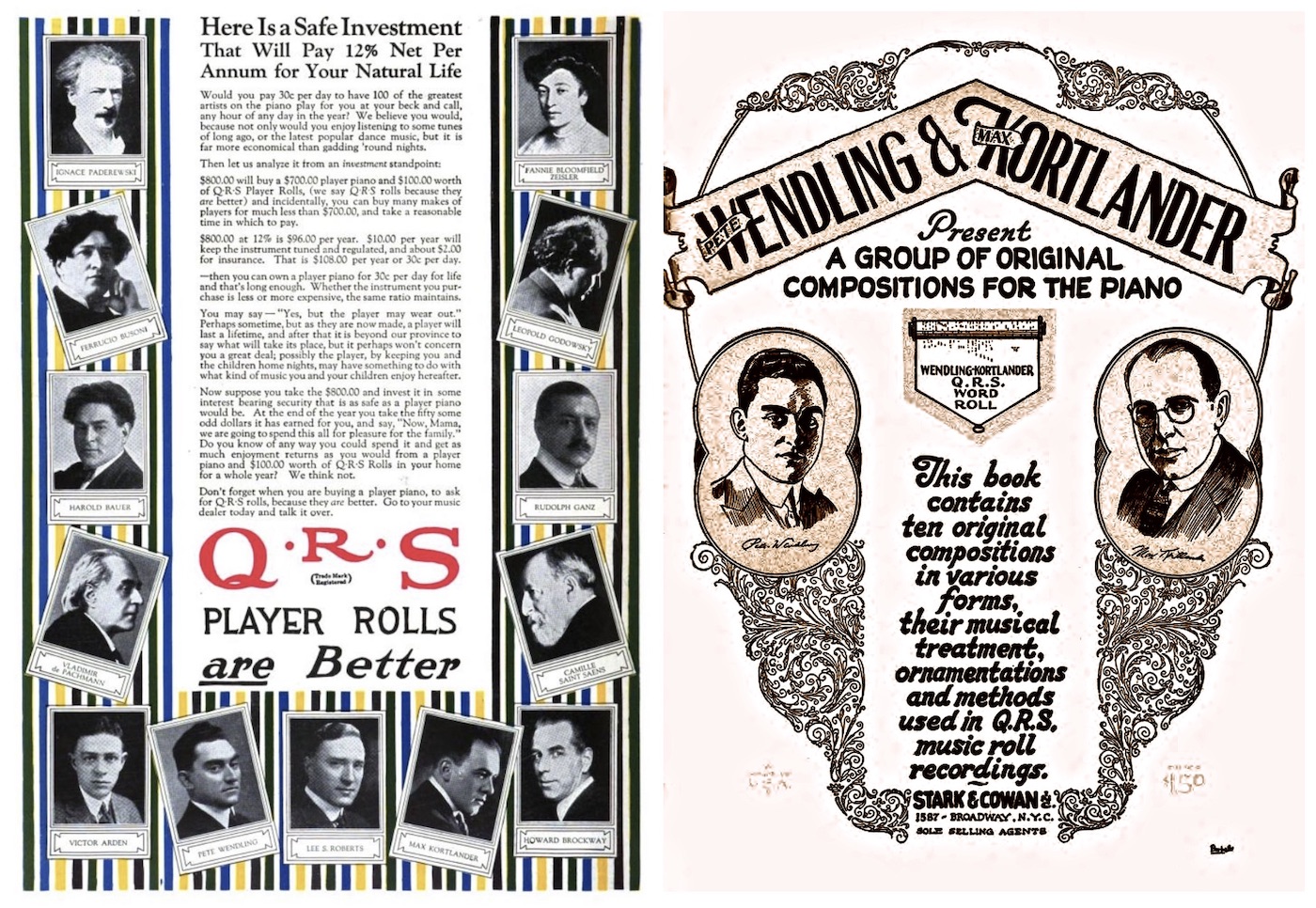

[Left: 1922 ad featuring some of the musicians featured on QRS piano rolls, ranging from classical composers like Camille Saint-Saëns to QRS employees Lee S. Roberts and Max Kortlander. Right: 1924 sheet music compilation book featuring some QRS piano rolls compositions by Kortlander and Pete Wendling]

QRS didn’t necessarily need to go out recruiting famous concert performers—by the late 1910s, the company had built its own team of regular in-house contributors, including the aforementioned company VP Lee S. Roberts, as well as highly accomplished player/composers Peter Wendling, Zez Confrey, and the “King of the Player Piano,” Max Kortlander. While all of these men were white, QRS had been more progressive than most of its competitors in recording black artists, as well, including a series of rolls by John “Blind” Boone that were released back in 1912—among the earliest recordings ever made of a black musician.

For years, the songs of American popular music had always mattered more than the artist, but this was quickly changing as music buyers began to develop affinities for the styles of certain players. And since the same songs and performers would often be found on piano rolls produced by different companies, the reputation of each manufacturer and the quality of their sound became increasingly important, as well.

“If you already have it in a roll of another make,” read one 1916 ad for the new recording of Whose Pretty Baby Are You Now?, “hear this QRS Word Roll. Then you’ll understand why 90% of the dealers in Chicago sell QRS rolls.”

Standing out from the crowd wasn’t always easy. During most of the 1910s, QRS was still battling dozens of well known competitors, including names like Ampico (New York), Standard (New Jersey), and a few key rivals that would later become QRS acquisitions: Connorized (New York), Vocalstyle (Cincinnati), Imperial (Chicago), and the United States Music Co. (Chicago). From their own corporate offices in Chicago’s Fine Arts Building, the QRS creative team was always at work rolling out (pardon the pun) new features and gimmicks to keep pace, highlighted by the popular “Word Roll”—which printed the song’s lyrics directly on the sheet—and the related “Story Roll” and “Mother Goose Roll” for sing-a-longs with the kids.

It was soon clear, though, that keeping up with the changing musical preferences of the public would really determine which companies sank or swam. By 1916, the Aeolian Company of New York—the country’s largest player piano manufacturer—had already employed the African American pianist James P. Johnson as its new roll recording star. And over the next couple years, the Great Migration of black musicians from the South continued to bring a new, energetic new style of ragtime to American cities—setting the template for the jazz age, and creating a fork in the road for the sensibilities of the QRS Company.

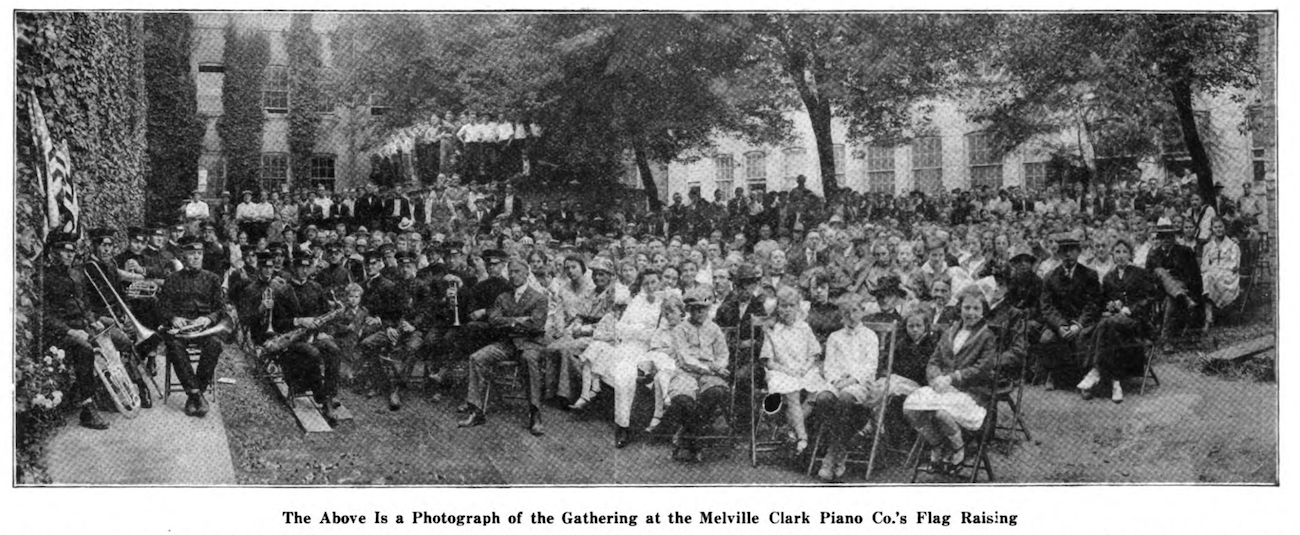

[Above: The QRS and Melville Clark corporate offices were located in Chicago’s Fine Arts Building at 412 S. Michigan Ave. for much of the 1910s, seen above then and now. Below: 400 employees of Clark and QRS attend a service flag raising at the DeKalb campus in 1918]

V. New Blood

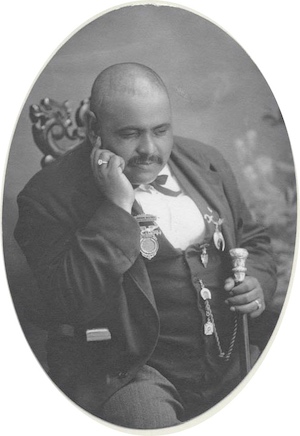

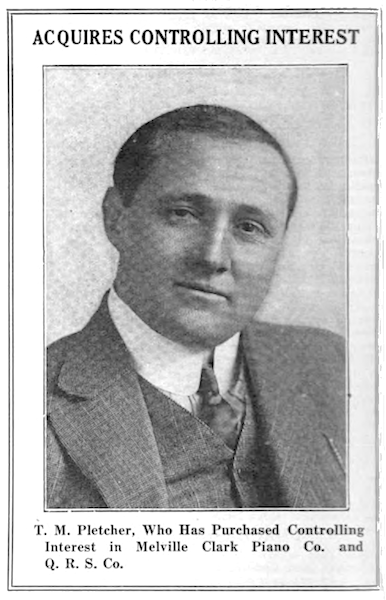

The change in the music scene, it turns out, coincided perfectly with a major shake-up in the QRS offices. In October of 1918, it was announced that the controlling interest in both QRS and the Melville Clark Company had been purchased by Thomas M. Pletcher (b. 1871)—a general manager with the business who’d started out as a salesman way back in 1903.

According to an article that month in the Music Trades, “The decision of Melville Clark to relinquish the control of the two companies is the result of long deliberation. For some time Mr. Clark, who has been a dominant factor in the music industry for many years, has felt that he was entitled to take things easier—to place himself in a position where he could fully enjoy the fruits of his many years of successful climbing in the trade. He expressed this wish to his associates and the big deal resulted. One condition, however, on which he agreed to relinquish the active control of the business was a personal assurance from Mr. Pletcher that the business would continue to be conducted strictly along the lines which have built its success—the Golden Rule methods—and that the same standard of excellence in the various products would be rigidly insisted upon.”

For his part, Tom Pletcher said he looked forward to giving “more time to the development of the business both in this and foreign countries,” but added that Melville Clark was “still substantially interested and will give the company the benefit of his genius, judgment and wide experience.”

Well, that didn’t quite go to plan. Melville Clark, age 70, would be dead within a few weeks of the sale, marking the official end of an era. At a subsequent meeting of the Chicago Piano Manufacturers Association, Clark was widely praised by all his old friends and rivals—including reps from Lyon & Healy, the Cable Piano Co., the George P. Bent Co., and the W.W. Kimball Co., along with QRS cohort Lee S. Roberts, who stayed on as vice president under Pletcher.

Less than a year later, in the summer of 1919, Pletcher sold the Melville Clark Company and its distribution wing, the Apollo Piano Co., to the Wurlitzer Company, which took over the entire DeKalb plant. The QRS Company, however, wasn’t part of the deal. Instead, Pletcher relocated the now fully independent piano roll business back to Chicago, renting space in an existing plant at 4829 S. Kedzie Avenue.

Pletcher also moved forward with new factories in San Francisco and New York City, including a major, modern new facility that opened in the Bronx in 1920. Max Kortlander—the aforementioned “king of the player piano”—was dispatched to run the NYC recording department, and from coast to coast, QRS’s new young leadership wasted little time actively recruiting more diverse musicians who could better represent the tastes of the Roaring ‘20s.

[The QRS Chicago factory at 4829 South Kedzie Avenue, in use from 1919 to approx.1932. It was later owned by International Harvester and ultimately torn down near the end of the century]

This would eventually lead to recording sessions with some of the early icons of African American jazz and blues, including James P. Johnson himself (composer of the decade’s biggest dance craze, “The Charleston”), noted Chicago piano men Clarence “Jelly” Johnson and Clarence M. Jones, and future legends Fats Waller and Jelly Roll Morton; the latter of whom is believed to have cut his QRS rolls at the Chicago factory.

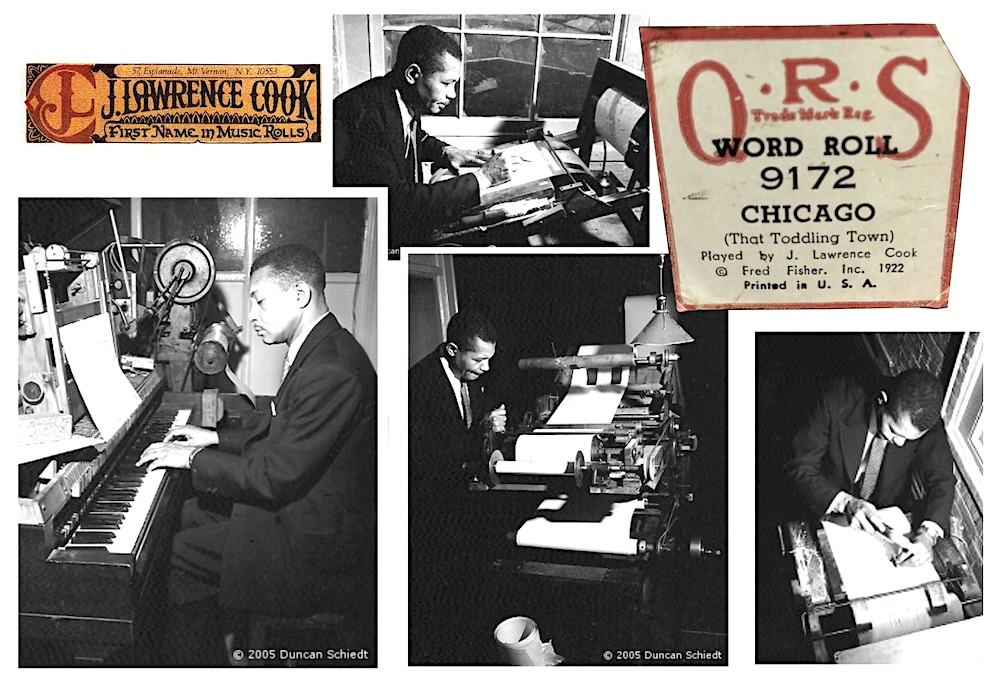

The most significant QRS recruit of the early ‘20s, though, was a lesser known musician named J. Lawrence Cook—the man would become the single most prolific piano roll recording artist of all time.

Born in Tennessee in 1899, Cook was a wunderkind African American pianist and arranger who is estimated to have produced and/or recorded as many as 20,000 different rolls across a 50+ year career—the vast majority of them for QRS.

According to census and draft records, Cook briefly lived on Chicago’s South Side in the late 1910s, doing several odd jobs, including a gig with the Novelty Candy Company. It’s possible his musical skills first came to the attention of QRS during this period, but he didn’t officially join the company on a permanent basis until 1923, when he came to work under Max Kortlander in the Bronx office.

Along with the countless rolls credited directly to Cook at the keys, there were many hundreds more in which he did most of the heavy lifting for other artists, arranging and editing even the likes of James Johnson and Jelly Roll Morton. The case has been made that no man did more to bring black music into mainstream America than J. Lawrence Cook, but his skills went far beyond any single genre, as he was just as adept interpreting a classical piece or—years later—a Beatles tune.

[Above: J. Lawrence Cook at work at the QRS offices in New York. Below: Cook’s arrangement of “Tea for Two,” from QRS piano roll #2894]

VI. On a Roll

“The factories of the Q-R-S Music Co. in Chicago and New York are working night and day at present and expect to keep up this pace for some time to come,” the Music Trades reported in 1921. Thomas Pletcher was quoted in the story adding that, “Whatever other factories are doing, ours are running on time and overtime.” This was a veiled reference, perhaps, to the fact that new options in home music entertainment—specifically the radio—weren’t causing any concern in the QRS house.

Pletcher wasn’t fibbing. His company was still cresting, and by 1927, QRS hit record sales of 10 million rolls. They were also benefiting from a shrinking bubble, though, absorbing old foes like Connorized and the U.S. Music Co. en route to their now undisputed dominance in the industry.

Pletcher wasn’t fibbing. His company was still cresting, and by 1927, QRS hit record sales of 10 million rolls. They were also benefiting from a shrinking bubble, though, absorbing old foes like Connorized and the U.S. Music Co. en route to their now undisputed dominance in the industry.

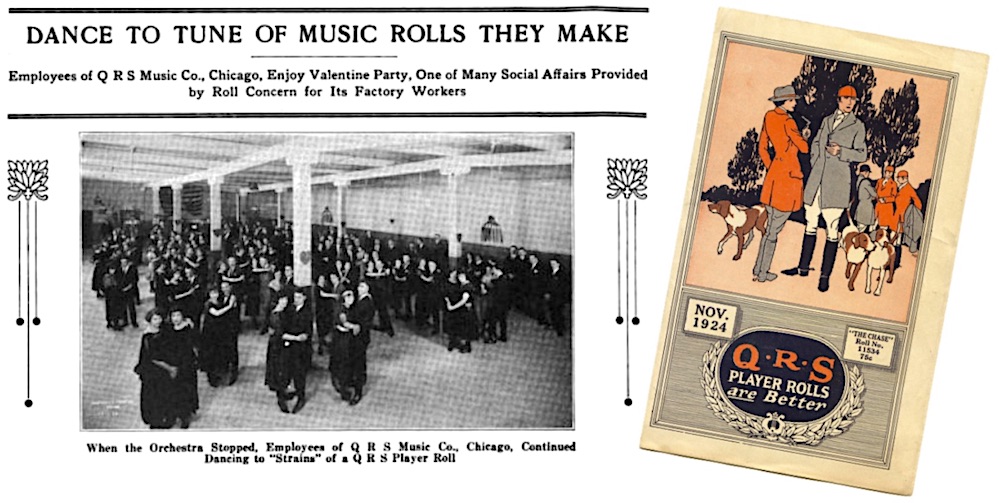

While the Bronx plant was now the main hub of the firm, the Chicago factory was still thriving, and its employees—a mix of men and women—seemed to have a pretty good working environment, if you believe the Music Trades.

“The Q-R-S Music Co., as well as providing the best possible conditions for its employees during working hours, also puts forth every effort to make their social life enjoyable,” read an article in 1923, recounting a recent Valentines Dance held at the Chicago factory.

“These efforts, in face of the labor troubles and dissatisfaction often met these days, have resulted in making the entire force ‘hit on all twelve’ and are cause for pride on the part of the company. . . . This dance and this happy group of persons who make the music rolls that make thousands of others happy all over the country are due to the efforts of T. A. Cunningham, general factory manager of all the QRS factories, and Tom Spence, superintendent of the Chicago factory, who arranged the affair.”

Tom Pletcher, to his credit, wasn’t expecting to keep dancing his way to endless success. An expert salesman, he saw radio and record players as the legit threats they were, and he tried his best to put QRS in position to diversify and compete.

In the early ‘20s, the company started making its own piano roll cabinets, speakers, and portable phonographs, but had little luck carving out a new niche. Pletcher also established a potentially lucrative partnership with the Chicago company that would soon be known as the Zenith Radio Corp, taking over the manufacture of their CRL receivers and developing a line of “Red Top” radio tubes. Zenith’s president, Eugene F. McDonald, even made Pletcher a vice president at the radio firm for a few years, but when the QRS factory proved unable to keep up with Zenith’s growing demands, the working relationship sputtered out.

Other QRS business strategies in the ’20s were a tad less respectable, leading to Pletcher and his team coming under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission for price fixing schemes.

Other QRS business strategies in the ’20s were a tad less respectable, leading to Pletcher and his team coming under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission for price fixing schemes.

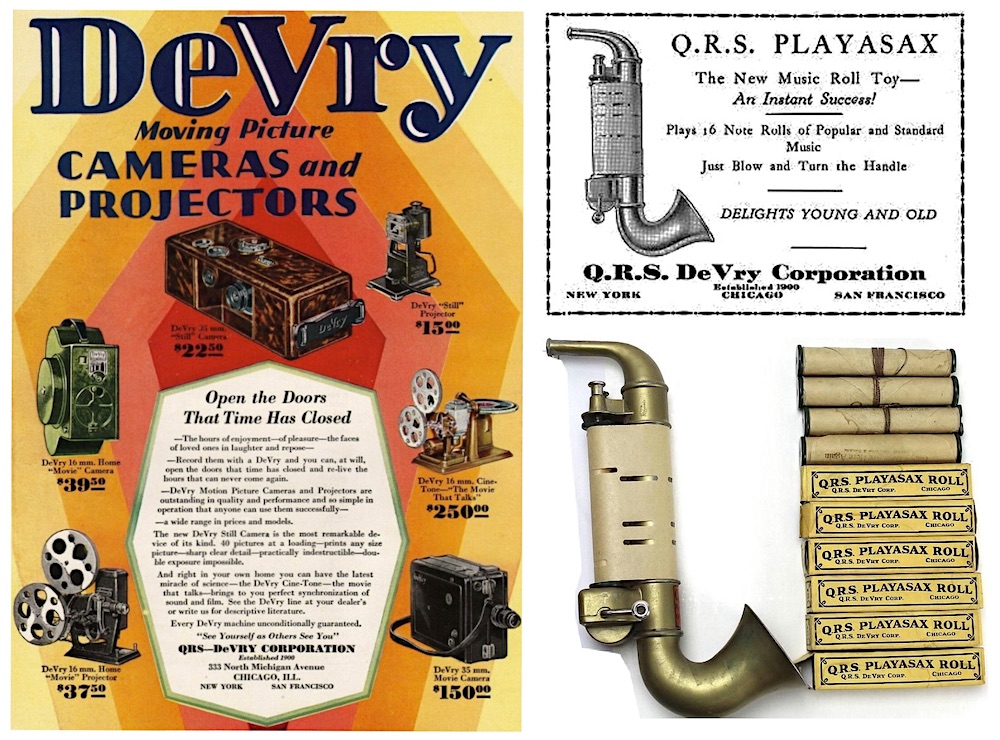

Pletcher’s last big Hail Mary toss for product diversification came in the spring of 1929, when QRS purchased Chicago’s DeVry Corporation, a major producer of movie cameras and projectors. The new combined entity, QRS-DeVry, sought to become Chicago’s ultimate dynamic force in visual and audio entertainment, and even expanded into some intriguing / bizarre new types of automatic instruments, such as the QRS “Playasax.” Unfortunately, the timing of this bold new venture was downright awful.

[Left: Advertisement for QRS-DeVry camera and projectors, 1929. Right: Ad for the automatic “QRS Playasax,” 1929, along with an image of the instrument and its associated music rolls]

VII. The Second Life of Q-R-S

The easy narrative is that the stock market crash in October of 1929 pulled the rug out from under QRS-DeVry. After all, just two years earlier, QRS had its highest piano roll sales numbers in its history, and just about all its old competition had been bought out. In reality, Thomas Pletcher was walking a tightrope for most of the late 1920s, acquiring other roll manufacturers largely because they were there for the taking—the industry was getting crushed by radio and phonographs. The market crash merely provided the final blow.

By 1932, Pletcher was forced to start disbanding QRS-DeVry piece by piece, including selling the AV part of the business back to Herman DeVry and shutting down the Kedzie Avenue plant (which eventually came under ownership of International Harvester). This was, officially speaking, the end of the QRS Company in its original incarnation, and the end of its days as a Chicago business. It was not, however, the end of QRS piano rolls.

Longtime QRS musician and recording manager Max Kortlander couldn’t bear to see the demise of this once proud business—and the artform itself—so he famously mortgaged his own home in order to buy out Pletcher and take over the surviving QRS properties in New York. It wouldn’t exactly be a glorious return to form. Running the revived company under a new name—the rather villainous sounding “Imperial Industrial Corporation”—Kortlander had to scrap all hand-played “Autograph” rolls in favor of cheaper rolls marked out with pen and paper. Most of these were arranged by the one man Kortlander knew he had to retain from the original QRS team: J. Lawrence Cook.

Longtime QRS musician and recording manager Max Kortlander couldn’t bear to see the demise of this once proud business—and the artform itself—so he famously mortgaged his own home in order to buy out Pletcher and take over the surviving QRS properties in New York. It wouldn’t exactly be a glorious return to form. Running the revived company under a new name—the rather villainous sounding “Imperial Industrial Corporation”—Kortlander had to scrap all hand-played “Autograph” rolls in favor of cheaper rolls marked out with pen and paper. Most of these were arranged by the one man Kortlander knew he had to retain from the original QRS team: J. Lawrence Cook.

Through the 1940s and ‘50s, Cook remained the most important talent at Imperial, which revived the QRS brand name during a nostalgic wartime revival in piano roll sales. Despite being one of the most heard recording artists of the early 20th century, though, Cook never achieved fame beyond the niche world of music roll aficionados, nor did he make a fortune from his work. Through most of his career, he kept a second job with the New York City Post Office, retiring more on the government pension than his musical earnings.

Following the death of Max Kortlander in 1961, his widow Gertrude sold the business to entrepreneur Ramsi P. Tick, who moved the operation to Buffalo, New York, in 1966. While the company never got close to regaining its old standing, it did succeed for decades in keeping the legacy of player pianos and music rolls alive.

For most of the past 50 years, QRS was the only major roll manufacturer still actively creating new product—both in the form of re-released classic rolls and new digitized player piano tech—and the Buffalo era wound up exceeding the lifespan of both the Chicago and Bronx chapters of the company history.

Unfortunately, after various stops and starts, the Buffalo plant finally produced its last roll in 2019. QRS Music Technologies, Inc., lived on, however, and as of 2021, still produced piano rolls on a small scale at a plant in Seneca, Pennsylvania.

[A tour of the QRS roll factory in Buffalo, NY, from late 1980s Canadian TV program “The Acme School of Stuff”]

Sources:

Inventing Entertainment: The Player Piano and the Origins an American Musical Industry, by Brian Dolan, 2009

“The QRS Marking Piano: A National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark” – The American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 1992

“Q R S Player Rolls” – The Purchaser’s Guide to the Music Industries, 1922

“The QRS Story” – The Phonographic Record, Vol. 18, Issues 3/4, 1983

“Q R S Music Co. Enters Roll Cabinet Field” – The Music Trades, March 31, 1923

“White-Smith Music Publishing Co. vs Apollo Co.” – U.S. Supreme Court, 1908

“Federal Trade Commission vs. The Q.R.S. Music Company,” 1924

Face Time with Jere DeBacker – DeKalb Daily Chronicle, April 14, 2014

“A Buffalo Love Story: Bob Berkman, the Player Piano and QRS Music Rolls” – WBFO NPR

“J. Lawrence Cook” – doctorjazz.co.uk

“Max Kortlander: King of the Player Piano” – doctorjazz.co.uk

“Maximilian J. Kortlander” – ragpiano.com

“Melville Clark Piano Company” – Mechanical Music Registry Project

“Q.R.S. Company Have Plans Underway for New Chicago Building” – DeKalb Daily Chronicle, June 14, 1919

“New Concern Will Mean Much to Us” (Wurlitzer buys out Melville Clark Co.), DeKalb Daily Chronicle, Aug 20, 1919

“QRS Autograph Roll Master List” – AMICA News Bulletin, Vol 25, No. 3, May/June 1988

Hi. We are in our 70’s and realize the time to downsize is now. We are getting our proverbial ducks in a row. Our player piano has decided to be a manual piano only so even giving it away has become a difficult task! The idea of cutting it up goes against everything I have ever considered but unfortunately it has probably become a reality.

My next concern is the 80 to 100 piano rolls. When my husband’s family purchased the piano for his sister and Jay to learn to play the piano he said there were a few hundred rolls. It came out of a movie theater and most were the rolls of the Silent picture era. They destroyed the majority of the rolls at that time. …. I’m curious as to whether or not the Q.R.S. Rolls can be dated by the box they are in, or the writing on the box. The majority of the boxes are QRS with a few Picturoll, Kimball etc . Is there a site that dates these rolls or possibly a museum? Would I like to sell them? Yes. But if selling them is just not possible and donating is the only way they will see the light of day then I will look into that option too. I’m not a hoarder but have an affectionate relationship with items that hold a memory for my past. This piano and the rolls that I heard played by our daughter and her group of friends still bring me joy through the memories.. However the space is just not there for it in our future. Any ideas you can give me for selling the rolls, or donating the rolls and piano would be greatly appreciated.

Thank you Jan Petty….. a woman whose own mother said in the nicest way possible “Sweetheart you just couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket.,..” and whose own daughter as a toddler laying on my lap while I was singing and rocking her to sleep put her little finger to her lips and whispered shhhhush” and yet STILL loves to sing when she’s alone THANKS you for any assistance to can give me.

One correction: The “Autographed” rolls were not hand-signed. The signature was rubber-stamped on each roll, at the same time as the title-block was.

We have 2-3 boxes of piano rolls and a player piano that we can date back to early 1900’s. Our family got it from an elementary school in Golf, IL. Know of anyone that’s be interested in these items? Thank you!

Hi! Did anyone answer your inquiry? I have 3 boxes of boxed player piano sheets. Wondering if you found a place who would be interested in them?

I would be interested if the offer still stands.

I have several boxes of player piano rolls purchased in the early 1900. Do you know who would what to purchase them?

I would be interested

Not sure if anyone see this. But I bought many qrs word rolls at an estate sale last year. I’ve seen many 3 or 4 number ones but I came across a 5 number on 31395 are 5 number ones rare and what year would it be from. Thanks Jack Dedrick

I just got a 5-digit roll: 33297 – “Russian Rag” (a tune published in 1918).

Its box is about 25% smaller around than a standard QRS small box, and it’s not marked QRS anywhere except on a printed label on one end. I wonder if this was to save materials during World War I.

The roll isn’t Autographed, and doesn’t name the arranger. It just names the composer (Cobb, after Rachmaninoff) and the publisher (Rossiter, who published the 1923 follow-up, “New Russian Rag”). And it has dynamics marked all through it.

QRS doesn’t have any versions of “Russian Rag” in its archives, so this is a real rarity.

Great job and read & by the way, QRS is still manufacturing piano rolls. We have moved production to our factory in Seneca PA. Where we are merging new tech with old so we can continue our commitment to keep this piece of America alive.

Thomas Dolan

CEO QRS Music Technologies, Inc.

Hi, I was cleaning out my mother’s attic and found an old QRS model 15 portable victrola. It can be wound up and the turntable spins but it stops spinning when you try to play a record on it. Do you know of any reputable victrola restoration companies? I’d prefer one near Albuquerque, New Mexico. Thank you!