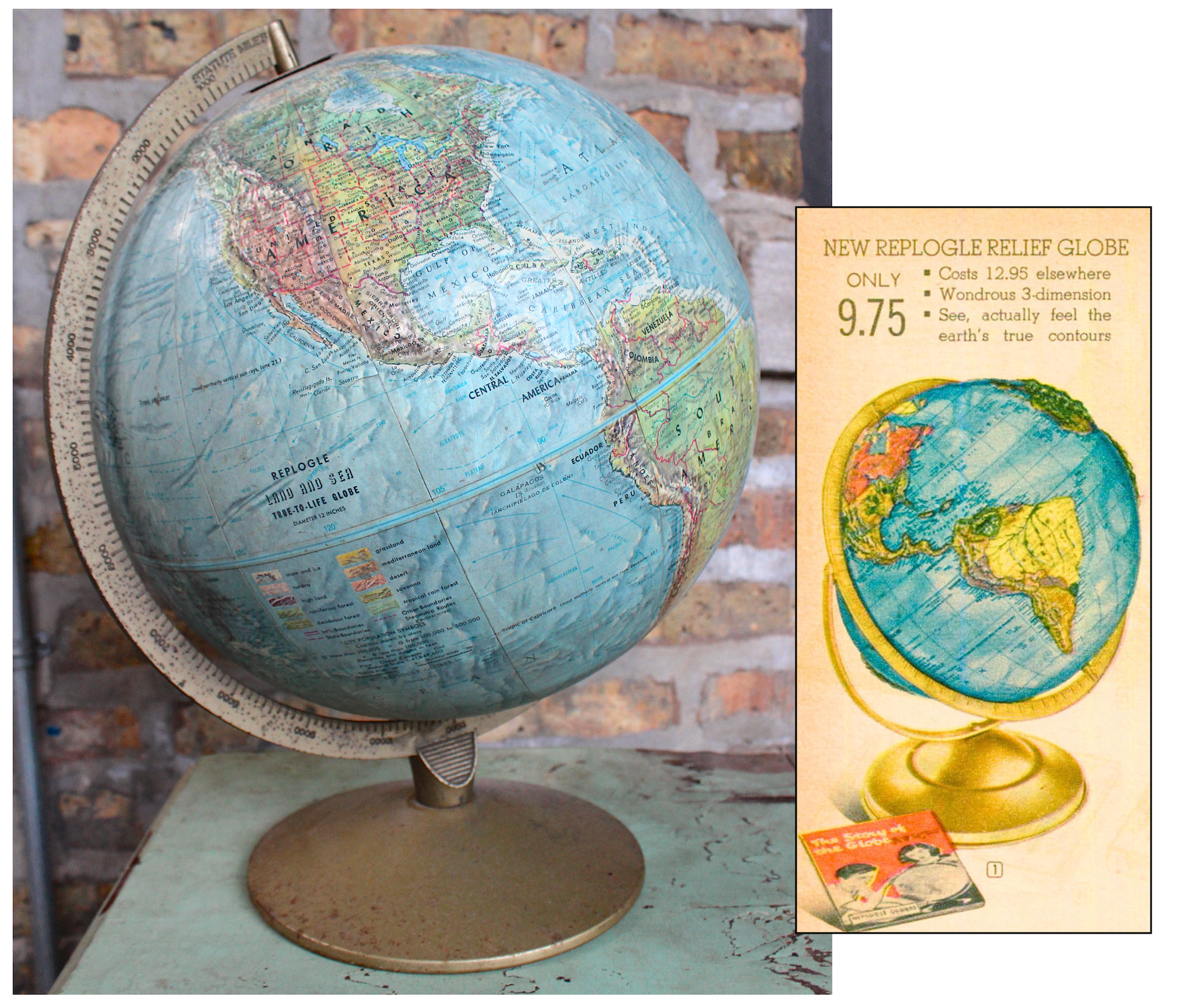

Museum Artifact: Replogle 12″ Relief Globe, 1964

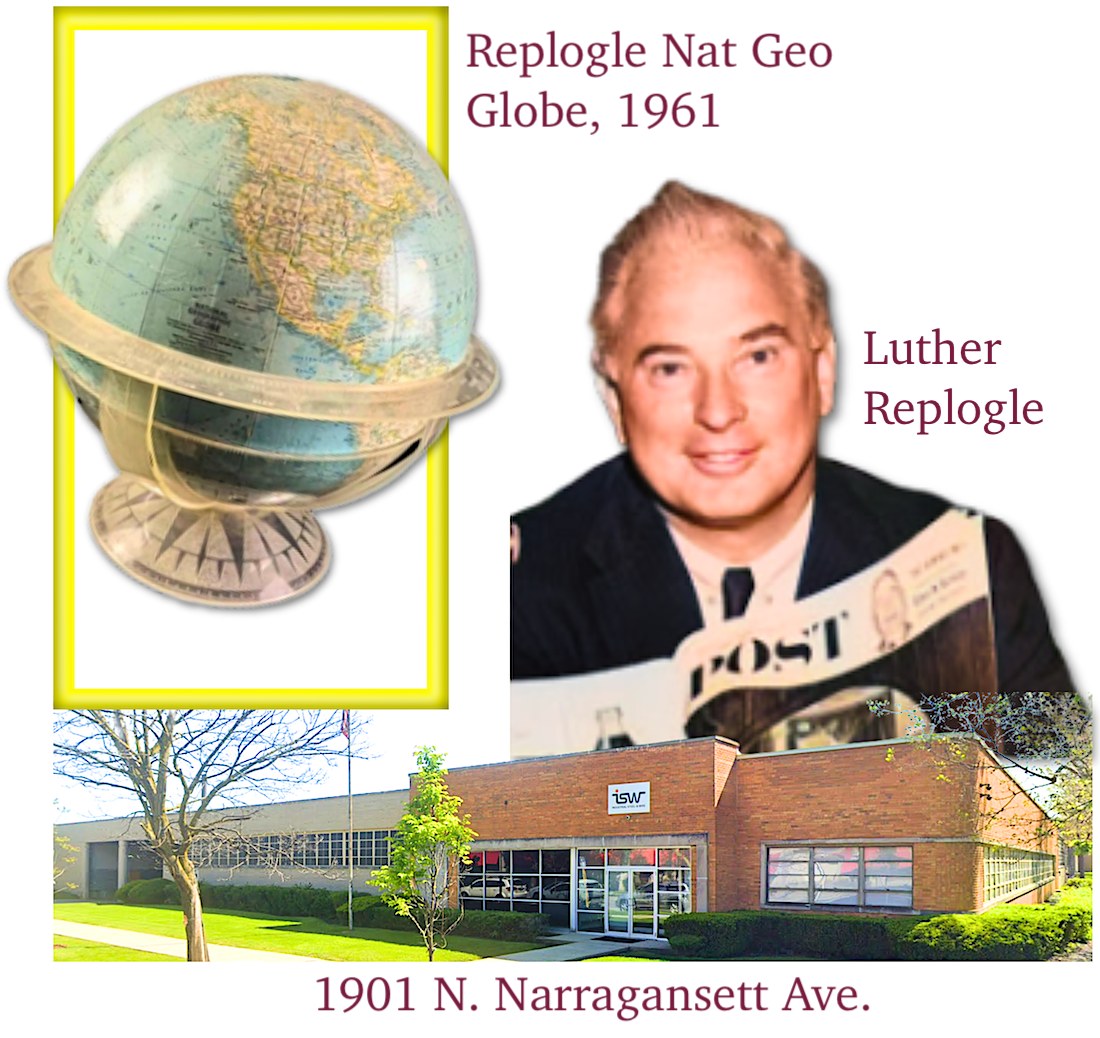

Made By: Replogle Globes, Inc., 1901 N. Narragansett Avenue, Chicago, IL [North Austin]

“As I followed that globe from beginning to end of the manufacturing process, I was struck by something cosmic in the very setting. Overhead, conveyers whirled finished spheres in stately orbits. Below them, ranks of plastic bases glittered like stars. I stood amid a galaxy in miniature.” —National Geographic president Melville Bell Grosvenor, describing his tour of the Replogle Globe factory in Chicago, 1961

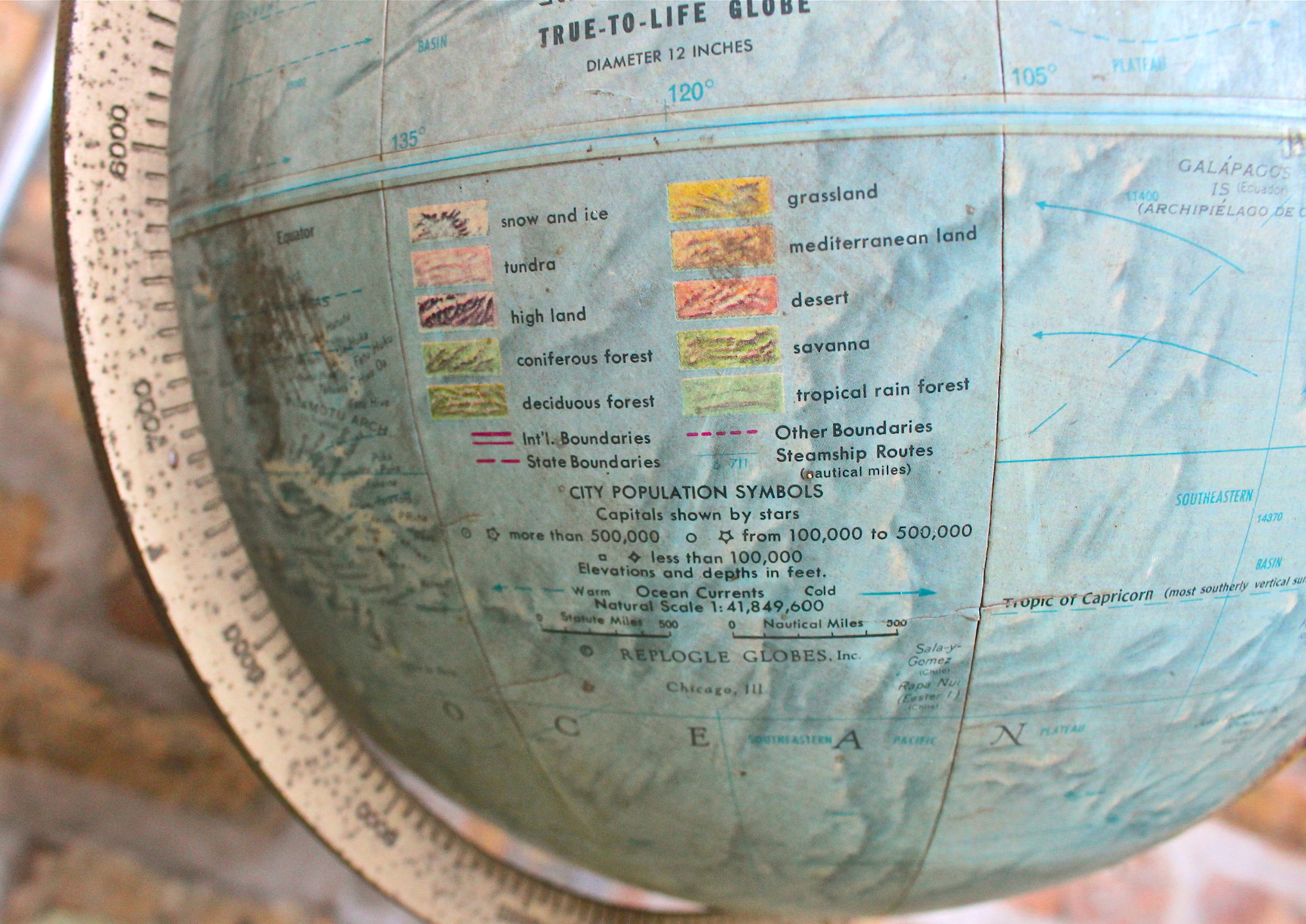

Replogle, appropriately enough, is one of Chicago’s best-traveled brand names. If you look for the trademark on any random spinning globe you encounter (it’s usually stamped a little west of the Galapagos Islands), you’ll quickly get a sense of how this former mom-and-pop enterprise grew larger than any “to-scale model” could measure.

Replogle, appropriately enough, is one of Chicago’s best-traveled brand names. If you look for the trademark on any random spinning globe you encounter (it’s usually stamped a little west of the Galapagos Islands), you’ll quickly get a sense of how this former mom-and-pop enterprise grew larger than any “to-scale model” could measure.

In our school days, many of used a Replogle globe—probably one slightly discolored by years of grubby-handed spins— to find the locations of faraway cities. What we didn’t know is that a lot of people in those faraway cities were doing the very same thing, studying the earth on a globe created in Chicago and exported to the wider planet. Once you start noticing Replogles out in the wild, you’re hard-pressed to go far without spotting another one. In recent years, I encountered an ornate 1950s model in a B&B in New Orleans; a utilitarian ‘80s design sitting in a bookshop window display in Dublin, Ireland; a small ‘60s bookend style in a café in Rome.

For nearly a century, Replogle has been the world’s leading manufacturer of . . . the world. Even many of the globes that don’t say “Replogle” on the label still passed down the company’s conveyor. And it all started nearly 20 years before mankind had ever seen an actual photograph of the planet Earth as we know it.

[Luther Replogle, center, discussing some of his company’s latest globes during an appearance on Chicago’s WGN-TV in the 1950s. WGNTV.com]

History of Replogle Globes, Part I: A Good Rep

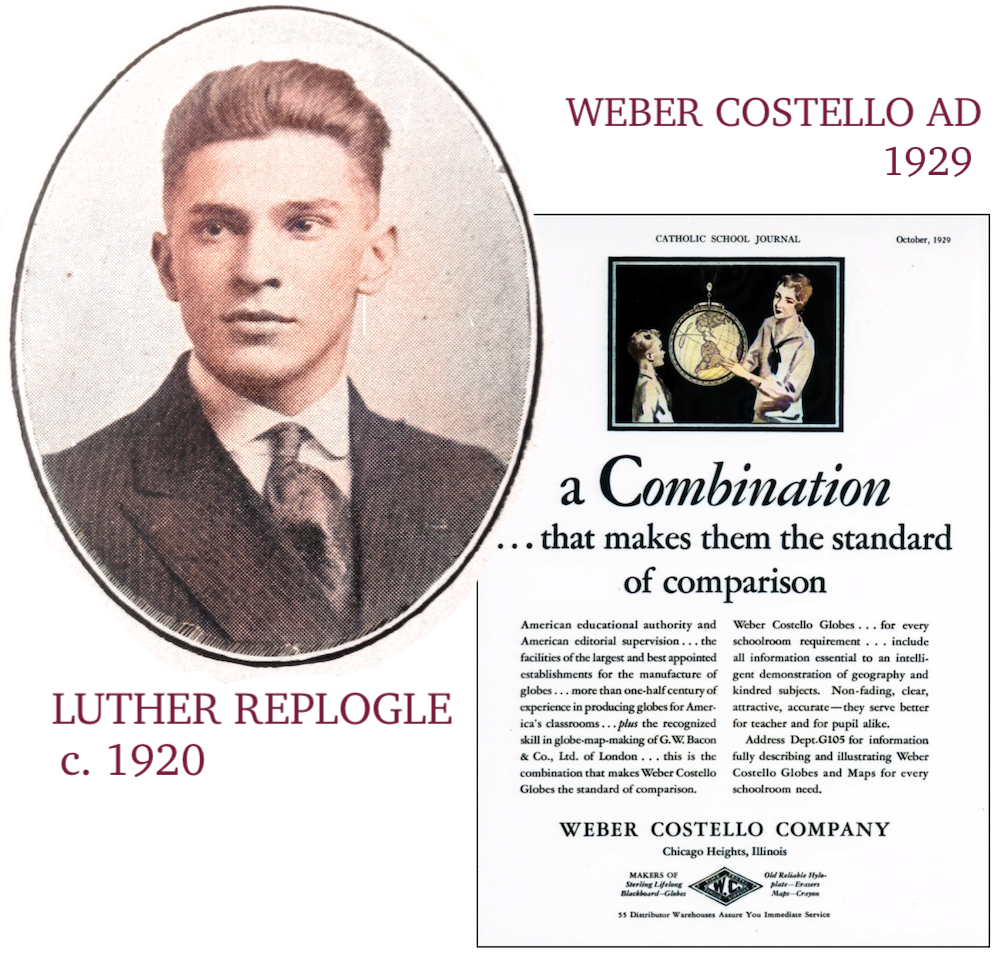

Luther Irvin Replogle is the hero of this story; another example of the down-and-out salesman with a dream of something greater. He didn’t invent the globe—some Greek guy beat him to that punch about a millennium beforehand—but Replogle, a Pennsylvania Dutchman himself, saw a potential for these objects that no one before him had yet imagined.

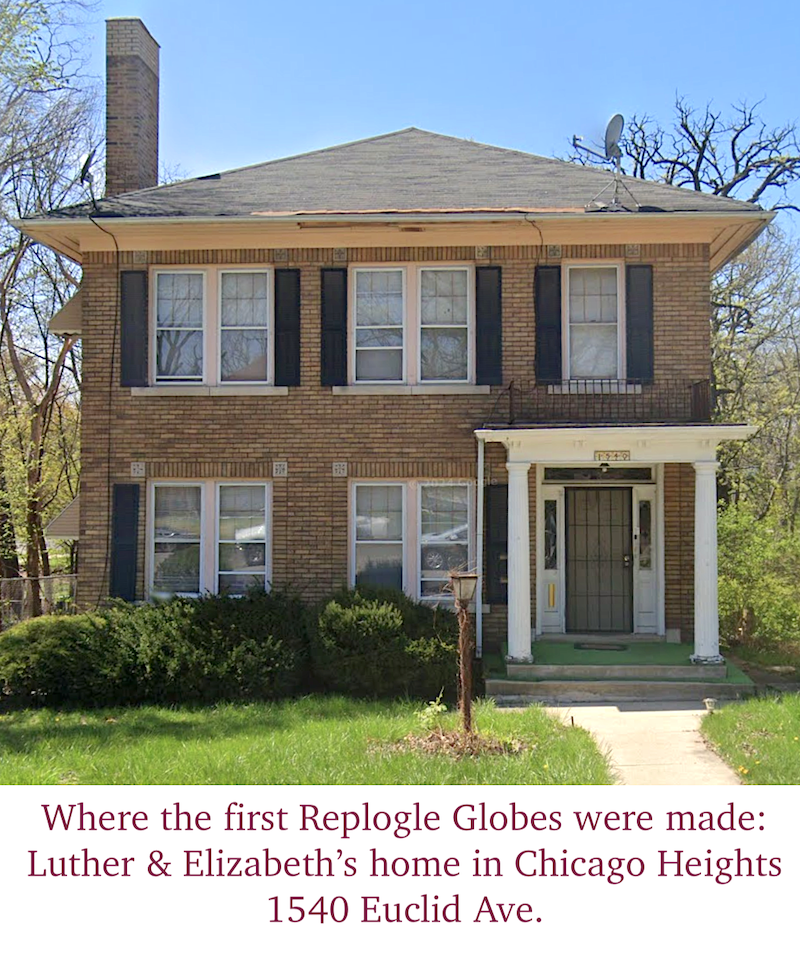

Born outside Altoona, Pennsylvania, in 1902, Replogle—known by his schoolmates as “Lute” and his business colleagues as “Rep”—was a bright student, earning an appointment to the U. S. Naval Academy in Annapolis in 1920. After two years, though, he dropped out and hit the reset button; reasons unclear. By the age of 25, Replogle was a newly married man but still not an entirely fulfilled one. He was now living in Chicago Heights, Illinois, and working as a salesman for the Weber Costello Company, a maker of various schoolroom supplies, including blackboards, erasers, pencil sharpeners, and yes, globes.

Born outside Altoona, Pennsylvania, in 1902, Replogle—known by his schoolmates as “Lute” and his business colleagues as “Rep”—was a bright student, earning an appointment to the U. S. Naval Academy in Annapolis in 1920. After two years, though, he dropped out and hit the reset button; reasons unclear. By the age of 25, Replogle was a newly married man but still not an entirely fulfilled one. He was now living in Chicago Heights, Illinois, and working as a salesman for the Weber Costello Company, a maker of various schoolroom supplies, including blackboards, erasers, pencil sharpeners, and yes, globes.

The work was steady enough, but after the stock market crash of 1929, any sense of job stability was out the window. Luther was at an early crossroads in his life, and decided to chase a hunch. He’d developed a notion that the colorful world globes he was hawking for Weber-Costello might have a wider appeal beyond their usual clientele, i.e., school superintendents and scholarly businessmen. Radio, telephones, and film were making the world feel smaller, and the average citizen wanted a tangible means of putting it all in a proper geographical context. . . . an affordable means, that is.

And so, in 1930, when most Americans were clinging to their jobs in desperation, Rep supposedly quit his (according to company lore) and started a DIY globe-making operation in his basement. An alternative, perhaps more likely version of this story is that he and his wife Elizabeth were both involuntarily unemployed at the dawning of the Depression, leaving the globe idea as their wild shot in the dark at scratching out a living. To get started, they borrowed $500 (about $10,000 in 2025 money) to organize an upstart business in their Chicago Heights apartment, meticulously crafting and hand-painting 12” globes from cardboard and plaster. Luther then packed the fragile spheres into his Model T and drove around Chicago selling them for $25 each. That is the equivalent of a whopping $475 by today’s standards. Business, predictably, was slow at the outset.

[Early 1933-34 Replogle globes, produced at the first Chicago plant at 320 S. Franklin St.]

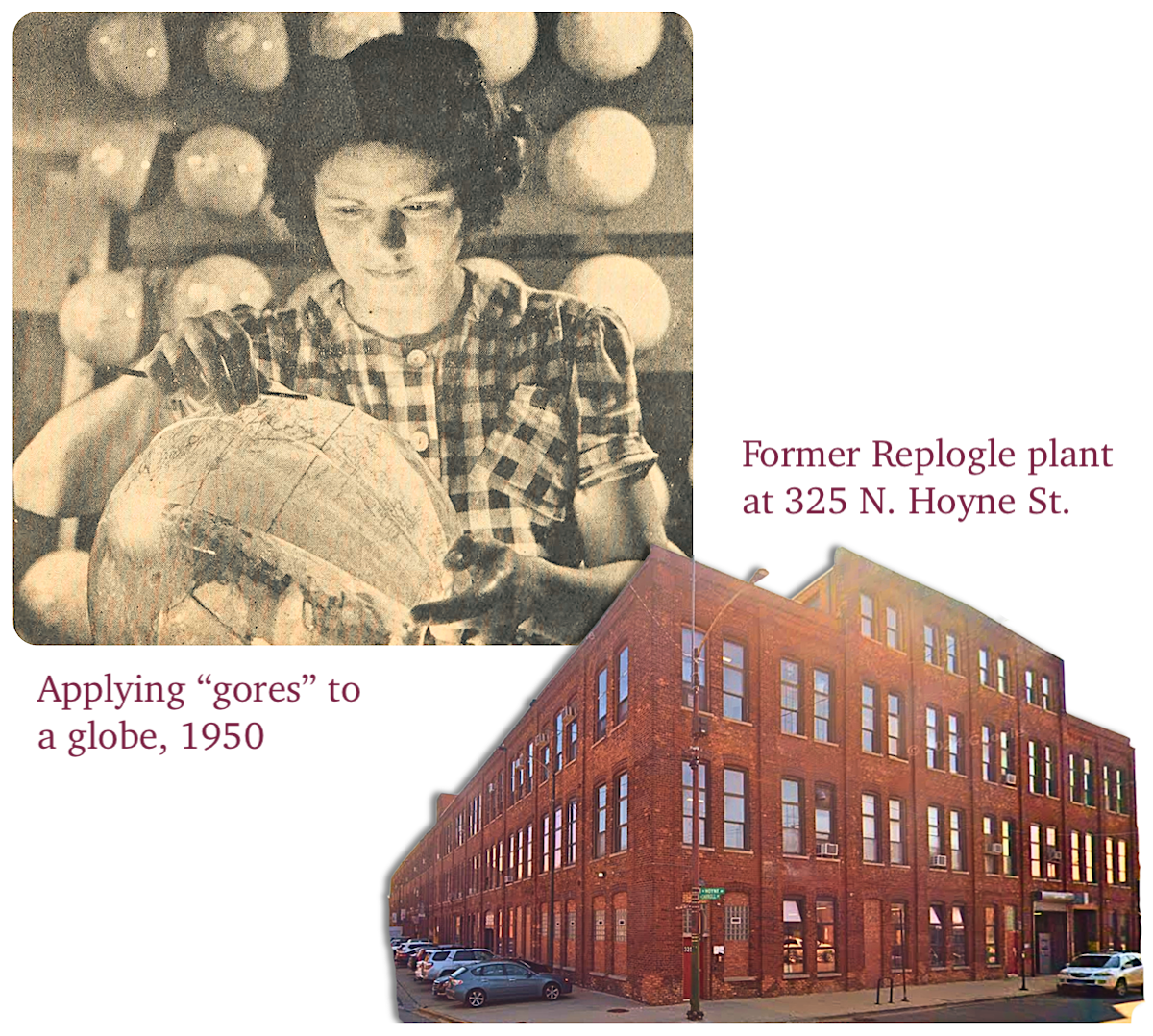

Even when Replogle purchased a modest manufacturing space at 320 S. Franklin St., in the Loop, he could afford only one employee, a Swedish immigrant, to work there. The skeletons of each globe were made in-house, but the actual exterior map sheets were purchased from a printer, then cut into sections (known as “gores”) and delicately hand-pasted with a strong adhesive. It was a difficult and time consuming process and not one traditionally suited for fast production on a mass scale.

According to company lore, it was the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago that inspired Replogle to re-imagine the business model and get the literal ball rolling.

According to company lore, it was the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago that inspired Replogle to re-imagine the business model and get the literal ball rolling.

Ahead of the event, Chicago’s beloved department store Marshall Field’s supposedly recruited Replogle to make 100,000 souvenir globes for the “Century of Progress” celebration, each of which would be marked at the far more reasonable price of $1.75 (roughly $33 in modern terms). Somehow or another, Luther and Elizabeth met the challenge despite the limitations of their small plant, and the Marshall Field globes went on to great success, putting Replogle on the proverbial map.

It’s a satisfying anecdote but also one that has proven disappointingly hard to substantiate. For one thing, it’s unclear how the upstart Replogle factory was able to meet such a tall order with its limited resources in the midst of the Depression—did Marshall Field & Co. offer up some of its manpower? As another stumbling block, the Made In Chicago Museum has yet to actually locate one of these souvenir globes on the usual platforms of vintage wares; at least not one that was clearly (a) made by Replogle, (b) connected to Marshall Field, and (c) produced specifically for the 1933 World’s Fair. Presumably, plenty of these 100,000 models should still be around, but the specifics of their design is hazy and surviving evidence, as a result, is scant.

In any case, whether jumpstarted by the Century of Progress or not, Luther Replogle managed to establish enough of a reputation for quality work in the early 1930s that he was soon outselling his own former cohorts at Weber Costello, as well as crosstown rivals Denoyer-Geppert. His partner in life and business, Elizabeth Replogle, was also a vital factor in the company’s early success, which made her sudden death in 1937 (she had caught pneumonia while on a trip to Mexico City) a tragic blow both personally and professionally. “Bets,” as Luther called her, was only 36 years old, and had given birth to the couple’s first child just two years prior.

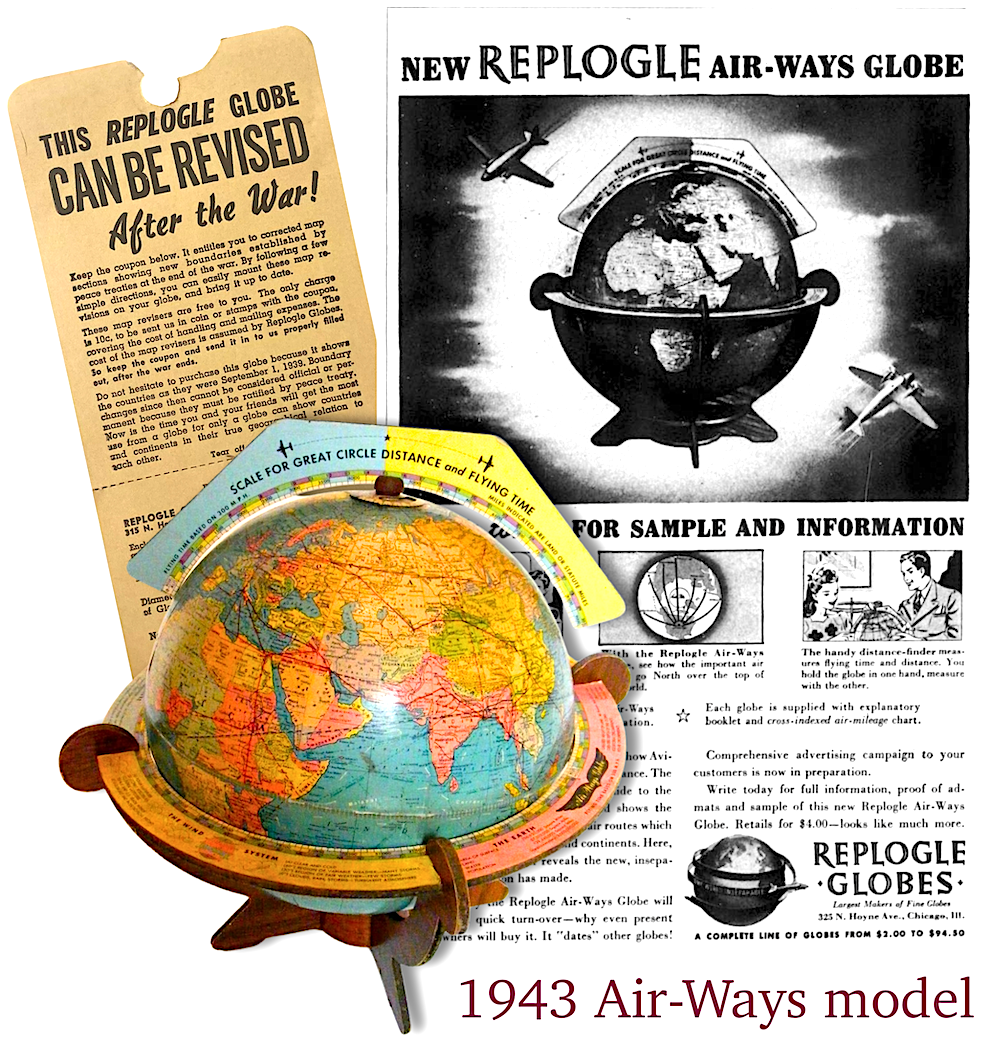

Following Elizabeth’s death, the company faced several years of lower sales and rough sledding. The thing that turned around its fortunes, oddly enough, was another tragedy: the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor.

[Hustle and bustle inside the Replogle factory in Chicago, c. 1940s. Replogle Facebook page]

II. The World Is Truly Round

As Luther Replogle later recalled to Travel magazine in a 1951 feature story, his company’s switchboard was “jammed with calls” in the days after the United States entered World War II, as department stores were being inundated with requests for up-to-date globes. More than just a classroom tool or a piece of posh home decor, the globe now represented a way for everyday people to make sense of the realities of this unprecedented conflict in a tangible way.

“The world seemed to have been shaken out of its two-dimensional torpor at that time,” reporter Arnold Caplan wrote in that Travel article, “and war-scared eyes began to peer around the evanescent curves of a world that had begun rather uncomfortably to assume a new and shrinking dimension. . . In the fifth decade of the twentieth century, man had suddenly discovered that the world was truly round—not just on paper.”

As globe sales spiked anew in the early 1940s, Replogle received another powerful, unpaid endorsement from none other than the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who started encouraging families to “get out your globe” as he described complex world affairs during his “Fireside Chat” radio broadcasts. Just about every U.S. President since has had an updated, 32-inch Replogle “Diplomat” globe in the White House.

To keep up with wartime demand, Replogle Globes, Inc., moved its operations from its 300-square foot downtown office to a 60,000 sq. ft. space at 325 N. Hoyne Street on the West side, with its workforce now increased to as many as 300 men and women. Here, production continued at a steady pace after the war, as the adoption of more advanced manufacturing methods enabled 1,500 globes per day to be completed, or “more than a world a minute,” as Travel magazine put it.

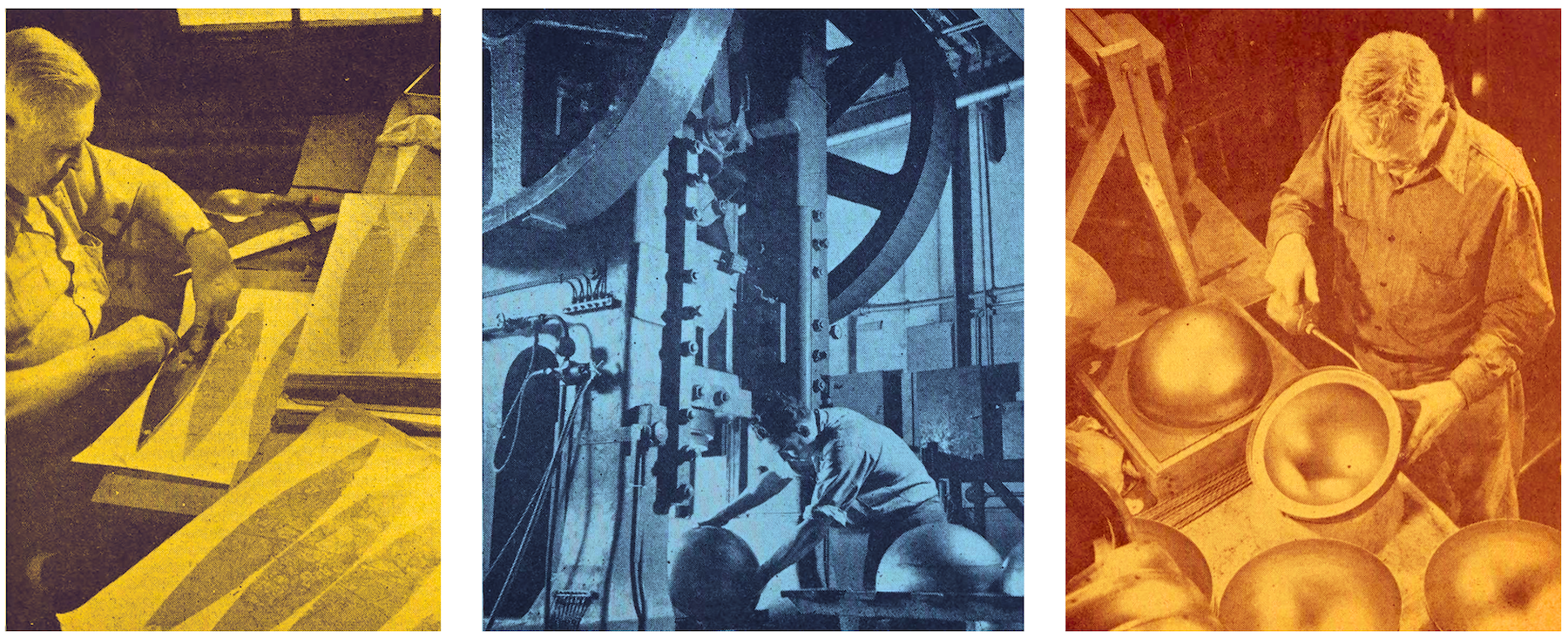

“When you step into the factory, you find yourself in a world of globes in various stages of production. You notice immediately a battery of 50-ton capacity completely automatic hydraulic presses, designed especially for making globes. To make machine globes, great pressure is required. The greater the pressure used in forming a globe ball, the more accurately names, places and lines will match, and the smoother and harder the ball.”

[Inside the Replogle plant in 1950. Top Left: Paper map “gores” are cut ahead of pasting. Top Center: Steel hemispheres are pressed into shape. Top Right: Two hemispheres are cemented together to form a new globe. Bottom: Making precise adjustments in the Replogle mapmaking department.]

Despite the speed, automation, and machining power, however, the actual creation of each Replogle globe still remained meticulous and demanded well-trained specialists across each stage.

According to a 1953 article in the Chicago Tribune, “Although most globes are made by machines on a modern assembly line, much work is done by hand and by skilled artisans. For example, it takes about two years to train a person in the globe covering technique. A skilled globe coverer can complete about ten 12-inch globes or eight 16-inch globes a day. It takes a day and a half to put the map on one of Replogle’s massive 32-inch globes.”

In that same story, Luther Replogle himself added: “If you think pasting strips of the map onto a round globe by hand is easy, just try to cover a smooth round apple sometime with a flat piece of paper without creating any tears or wrinkles in the paper.”

In that same story, Luther Replogle himself added: “If you think pasting strips of the map onto a round globe by hand is easy, just try to cover a smooth round apple sometime with a flat piece of paper without creating any tears or wrinkles in the paper.”

Perfectionism was also required to ensure that the actual geographical details on the globe—its essential purpose, after all—were 100 percent accurate and up-to-date.

“Making any globe map from scratch calls for a large expenditure of time and money,” Travel noted in 1951. “Replogle maintains its own map making department. Much research is required before work can be started on any new globe map. A vast library of government maps, foreign and domestic atlases, and much other geographical reference material constantly being replenished provides some of the information required.”

It was (and remains) a never-ending task for Replogle’s map makers, keeping up with political upheavals, international border disputes, and name changes. Those subtle alterations, year to year, do offer an unanticipated benefit for modern globe collectors, however, as you can usually pinpoint the age of any vintage U.S. globe by looking at how certain countries were being identified at the time. The 12-inch Replogle globe in our museum collection, for example, can be dated to 1964 for two hyper-specific reasons: Zambia is no longer Northern Rhodesia, but Barbados is still “Barbados (Br.).”

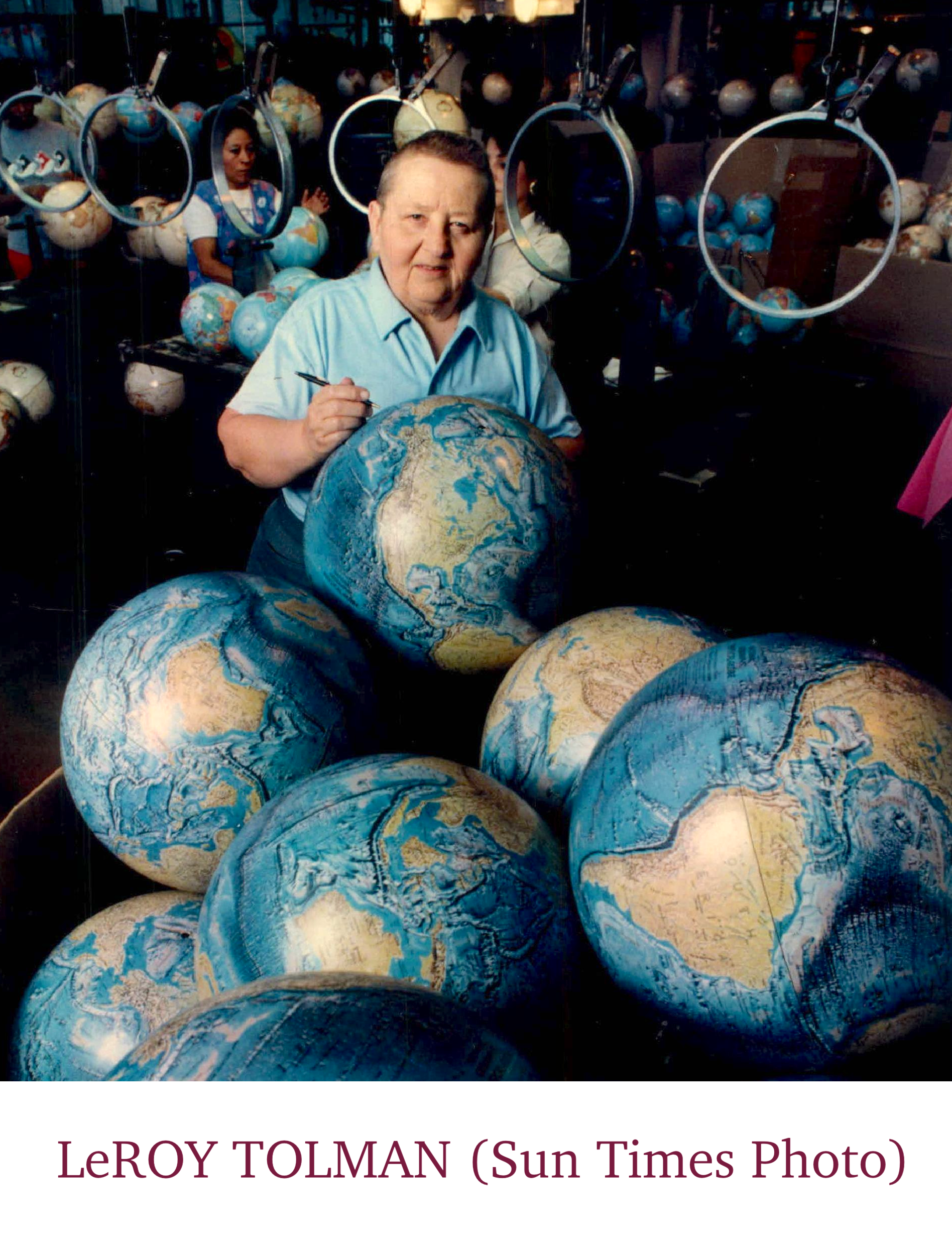

Of course, if you’re trying to determine the age of a globe made for the international market, things can get a tad more complicated. That’s because the “correct” details of a certain time period sometimes depended on the customer for whom a specific globe was designed. This was still the case when Chicago Sun Times reporter Neil Steinberg visited the Replogle plant in 1998 and spoke with head cartographer LeRoy Tolman [pictured below in 1987]. Here’s an excerpt from that story:

“Part of Tolman’s job is determining the accepted outline of a nation. He spreads a big map of Egypt out over his desk, responding to an irate Egyptian government complaint that its southern boundary with Sudan is shown as it actually is, and not how it exists in the fervent hopes of the Egyptians.

“Not much of a market in Egypt, so Tolman, after checking with the U.S. State Department, keeps the border where it is in actuality. That isn’t always the outcome. The company wants to sell globes and doesn’t flinch at following a customer’s interpretation of what the world looks like.

Globes going to Arab countries retained “Palestine” years after Israel was founded. Japanese globes show the country as still possessing the Kirin Islands, which the Soviets stripped away in 1945.

So if Saddam Hussein placed a big enough order, he could get globes showing the United States as a possession of Iraq? ‘All but Illinois,” said Tolman. ‘Economics is the prime factor.'”

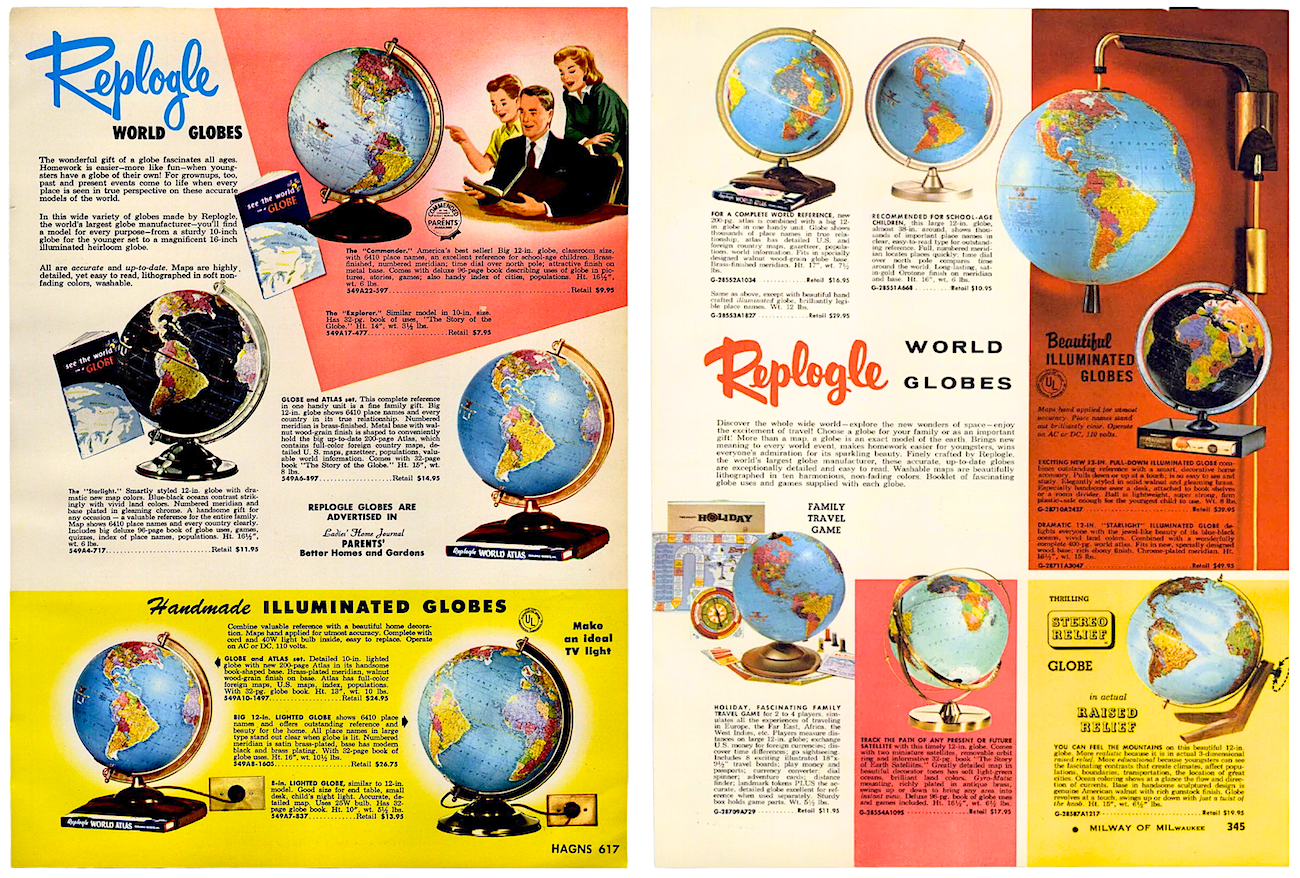

[Replogle magazine ads from 1957 (left) and 1961 (right)]

III. Touring the Replogle Factory: 1961

By 1954, Replogle Globes, Inc., had outgrown its Hoyne plant and acquired a new, modern 75,000 square foot facility at 1901 N. Narragansett Avenue in the North Austin neighborhood. This factory would eventually expand to nearly twice its original size, and would remain home to Replogle for the next several decades. It’s still in use today as the home of Chicago’s Industrial Steel & Wire Company.

Luther Replogle, now approaching the age of 60, was happily re-married and enjoying life as one of the pillars of the community of suburban Oak Park, IL. In 1959, he elected to sell his controlling interest in Replogle Globes to the Meredith Publishing Company (Better Homes & Gardens, Ladies Home Journal), but did stay on as President and CEO, using his influence to broker a manufacturing partnership with Scan Globes in Denmark, as well as a fruitful deal with the National Geographic Society to produce its official globes; more than 120,000 of which were sold to Society members between 1960 and 1961 alone.

Luther Replogle, now approaching the age of 60, was happily re-married and enjoying life as one of the pillars of the community of suburban Oak Park, IL. In 1959, he elected to sell his controlling interest in Replogle Globes to the Meredith Publishing Company (Better Homes & Gardens, Ladies Home Journal), but did stay on as President and CEO, using his influence to broker a manufacturing partnership with Scan Globes in Denmark, as well as a fruitful deal with the National Geographic Society to produce its official globes; more than 120,000 of which were sold to Society members between 1960 and 1961 alone.

National Geographic president Melville Bell Grosvenor visited Replogle’s new Chicago factory in 1961 and “marveled at the ingenuity and skill with which the beautifully lithographed rosettes, the molded hemispheres, the glistening lacquer were brought together into the finished product.

“Here I found no mindless assembly line, but dedicated craftsmen presiding over ingenious machines. The keen-eyed workers who punch polar holes into the flat gores by means of a complex ‘bombsight,’ the ‘Equator girls’ who bound 0-degree latitude with an incredibly deft flick of the wrist, the final packers—all inspect constantly and reject ruthlessly any globe that fails to meet the most stringent standards.”

[Replogle factory workers, 1961. (1) A punch press slices gores from flat hemisphere maps, each representing 30 degrees of longitude. (2) Gores are fitted on to a metal shaping die before a hydraulic press wraps the gores into one hemisphere of a globe. (3) Northern and Southern hemispheres are joined into a complete globe, then attached to a metal hoop and sent down a conveyor system. (4) An exterior lacquer is sprayed on each globe as it comes down the conveyor. (5) Final inspection before polar caps are added and the globes are packed for shipping.

[Luther Replogle (far right) shows National Geographic president Melville Bell Grosvenor how the conveyor system works at Replogle’s Chicago plant, 1961]

IV. Spinning Back Around

The workforce at the Replogle plant was as diverse as it was dedicated. As company president William C. Nickels explained in a 1977 News Journal article, “Just as it takes many different people to make up a world, it takes a variety of people to make a world.”

William Nickels had worked for Replogle for two decades and, as general manager, had played a pivotal role in building up the company’s capacity to meet orders in the 1960s. In 1969, when 67 year-old Luther Replogle was summoned by President Richard Nixon to become the new U.S. Ambassador to Iceland, the daily operations in Chicago were left all the more in the hands of Nickels. Four years later, when he got word that Meredith Publishing was looking to unload the slumping globe business, Nickels pulled together a team of investors and purchased the company himself.

William Nickels had worked for Replogle for two decades and, as general manager, had played a pivotal role in building up the company’s capacity to meet orders in the 1960s. In 1969, when 67 year-old Luther Replogle was summoned by President Richard Nixon to become the new U.S. Ambassador to Iceland, the daily operations in Chicago were left all the more in the hands of Nickels. Four years later, when he got word that Meredith Publishing was looking to unload the slumping globe business, Nickels pulled together a team of investors and purchased the company himself.

By this point, the employee count at the Narragansett factory had dipped to 150, but Replogle was still the largest globe maker on the globe, handling 70 percent of all such production and claiming 600 different models to its credit, including varieties of the Moon and Mars.

More change was afoot in the 1980s, as Replogle saw a gradual uptick in competition from cheaper plastic globes coming out of the Asian market, not to mention the whirlwind of geographical change brought about by the end of the Cold War. Even so, the company maintained its niche position atop the industry, and by 1987, required another move to a larger facility; this time in suburban Broadview, Illinois. Here, the workforce again swelled to 300, and the output of the factory spiked to upwards of 10,000 globes per day, including the ones sold by noted partners National Geographic and Rand McNally.

In terms of explaining why Replogle was able to maintain such a steady business year after year, Nickels told the Tribune in 1987, that, “From a cartographic standpoint, of course, the physical world is pretty stationary. But because it was turned over to us humans, the political part is apt to change every day.”

Replogle Globes, Inc., didn’t face a true existential crisis until the 2000s, when the company was acquired by the Herff Jones Company (better known as a manufacturer of class rings). In 2010, Jones re-located the business to a facility in Indianapolis, laying off more than 80 Chicago area employees in the process. The economic downturn of this period had already taken a toll, and by 2014, Herff Jones was planning to shut down its Replogle operations entirely.

Much as Bill Nickels had done nearly half a century prior, however, Replogle’s devoted purchasing manager, Joseph Wright, along with three other employees, rallied to save the business and purchase it from Herff Jones outright. Not only was this effort successful, but the new ownership group was also now able to move Replogle back to Illinois, to a plant in Hillside, about a half hour west of Chicago. This enabled some of the company’s former Chicagoland employees to return to their old jobs, and solidified Replogle as one of the rare uplifting tales among the storied businesses in the Made In Chicago Museum.

[Replogle employees pose with the product inside the Hillside plant, 2017 – Replogle Facebook page]

. . . As for Luther Replogle himself, the company namesake and founder died in Chicago in 1981 after a brief illness at the age of 79. According to the website of the Replogle Foundation, the Icelandic ambassador role he took on in the 1970s proved “an ideal post for him. [Replogle] worked diligently to strengthen U.S. foreign policy and defense ties with a valuable NATO ally, supported development of the national air carrier, Icelandic Air, and took a lively interest in the people and history of the country. . . . At the end of his Ambassadorial service in 1972, the Republic of Iceland awarded him its highest honor, The Grand Cross Star of the Order of the Falcon.”

*****

A unique memory from a Made In Chicago Museum visitor: “When I was in 5th grade (1990) I visited the Replogle factory and saw how the globes were made. I saw my very first industrial robots in that factory, and it made quite an impression on me. Thirty years later, I work as a senior engineer at FANUC, the world’s leading industrial robot manufacturer. Nostalgia for that moment, as a small boy, standing mouth agape watching these mechanical arms lifelessly move around on their own, is what lead me here. I’m glad to see that they’re still in business and in the Chicago area. Their dedication to not only putting globes in the classroom, but opening their factory doors to young minds is something remarkable.” —Scott Jackson, 2020

Sources:

“Making the World Go Round” – Travel, April 1951

“Biggest Globe Firm Building New Factory” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 24, 1953

“Your Society Takes Giant New Steps” – National Geographic, Dec 1961

“They Make the World Go Round” – Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1975

“Replogle: The World is Their Business” – News Journal, Dec 22, 1977

“Creating Spheres of Influence” – Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1987

“Replogle Sold the Globe to the World” – Chicago Sun Times, Jan 2, 1998

Archived Reader Comments:

“Hi, my name is Eleanor McMullen and i worked in Replogle Globes through the summer of 1984. I spent three months in Chicago as an Irish student on a J1 visa. I have very fond memories of working in the Narrangansett plant and remember fellow American students Sam Tinaglia, Gary Reimer, and Immy White. Still talk about my time there.” —Eleanor McMullen, 2017

In the mid 1950’s my family had a Repogle globe and a 36 inch by 24 inch wall map AND a card game to go with them. The map was on the wall right by the kitchen table where we always ate. We would sit there together often (though not while actually eating) and play that card game. We loved it and my sister and I remember it and the joy it brought all of us to play it. As I remember it, the cards had the name and maybe a picture of every nation shown on the map and the task was to get sets of four that fit the same criteria such as “countries that touch two oceans” or “countries that share a border (perhaps worded differently) and maybe “countries touch by a sea”. This meant that to play you had to look at the map or the globe and find the answers rather than look at the information on the card. I have not been able to find a vintage game but I would love to have a list of the instructions and especially what the categories were. Can you help me? No matter what I’d like you to know that your company produced something that gave my family many hours of joy and togetherness. I would love to be able to share this game with my grandchildren.

how can i tell what year my globe is made? it has Chosen (Jap) what other countries on globe would help me figure out year. My grandmother was a school teacher in 1914. it is said she had it then

i have a ciarca 1930s replogle 12″ globe was wondering value

Hello, I have a new with tags Globe Grams colorful globe. The world building game!

I was curious as to the value ?

I recently came into the possession of ”Replogle” globe purched in a thrift shop here in Australia. My Google search only mention globes of 12 inches and larger,no mention at all of a 10 inch size, which this is. I’m assuming this globe was made pre 1945 as ”Taiwan” is still marked as ”Formosa”. Can you enlighten me further?

Regards,

Frank.

I have a 10″ illuminated Replogle library globe with pre 1932 political boundaries. It doesn’t have a stand so I keep on an old lamp where it fits nicely and can be lit up. It has a wonderful patina that glows warmly at night. I wonder, though, if anyone out there might be able to help me locate its proper stand.

When I was in 5th grade (1990) I visited the Replogle factory and saw how the globes were made. I saw my very first industrial robots in that factory, and it made quite an impression on me. Thirty years later, I work as a senior engineer at FANUC, the world’s leading industrial robot manufacturer. Nostalgia for that moment, as a small boy, standing mouth agape watching these mechanical arms lifelessly move around on their own, is what lead me here. I’m glad to see that they’re still in business and in the Chicago area. Their dedication to not only putting globes in the classroom, but opening their factory doors to young minds is something remarkable. Thank you for preserving this part of Chicago history!