Museum Artifact: Revere 88 Movie Camera and Revere 85 Movie Projector, 1940s

Made By: Revere Camera Company, 320 E. 21st St., Chicago, IL [Near South Side]

“The Revere takes the clearest and steadiest home movies you have ever seen. Its advanced design (pocket size), its exclusive automatic film-threading sprocket, five speeds (including slow motion), precision construction, and many other proven features make Revere the outstanding value of 8mm movie cameras.”

–Advertisement for the Revere Model 88 camera, 1941

The Revere Camera Company never fully escaped the shadow of its Chicago rival Bell & Howell, and as a result, its role in the early home movie industry has largely been forgotten. For a brief period of time, however, this upstart firm—launched by former radiator repairman Samuel Briskin in 1939—became America’s preferred producer of budget-priced 8mm movie equipment, including the Model 88 camera and Model 85 projector in our museum collection.

The Revere Camera Company never fully escaped the shadow of its Chicago rival Bell & Howell, and as a result, its role in the early home movie industry has largely been forgotten. For a brief period of time, however, this upstart firm—launched by former radiator repairman Samuel Briskin in 1939—became America’s preferred producer of budget-priced 8mm movie equipment, including the Model 88 camera and Model 85 projector in our museum collection.

By the early 1950s, Revere employed 1,500 workers at two major Chicago plants (320 E. 21st Street, 221 E. Cullerton Street), and its production had expanded into electric drills, tape recorders, and other electronics. Sam Briskin’s aggressive advertising strategies, acquisitions, and pricing schemes had established an unlikely dynasty, but it was his son Ted Briskin—Revere’s young playboy president—who was always generating more of the headlines.

Between 1945 and 1953, the dashing Teddy married and divorced three different Hollywood actresses—a run that likely proved far less amusing back in Chicago, where his father was usually left holding the bag.

To be fair, Revere’s eventual collapse was probably caused more by the usual culprits: i.e., foreign competition + changes in technology and public taste. But the dynamic of a self-made immigrant entrepreneur and his spoiled, skirt-chasing son do make for a better tale; a classic American family drama.

History of the Revere Camera Co. Part I: From Russia with Radiators

Even as a millionaire industrialist himself, it was probably difficult for Revere founder Samuel Briskin to fully relate to the celebrity tabloid lifestyle of his silver-spooned son.

Born Shulem Boriskin in Russia in 1891, Samuel was virtually penniless when he fled his home country as a teenager to escape growing anti-Semitic hostilities, thus joining the latest wave of Jewish emigration to the U.S. He got himself a new name and new home in Chicago, but still had little more than a sixth grade education and far better Yiddish skills than English. To say Sam Briskin was a long shot for success would have been a generous analysis. But—like the hundreds of other immigrants who came to lead many of Chicago’s top manufacturing companies—Briskin had a certain grit and determination that seemed to render any odds-making irrelevant.

Born Shulem Boriskin in Russia in 1891, Samuel was virtually penniless when he fled his home country as a teenager to escape growing anti-Semitic hostilities, thus joining the latest wave of Jewish emigration to the U.S. He got himself a new name and new home in Chicago, but still had little more than a sixth grade education and far better Yiddish skills than English. To say Sam Briskin was a long shot for success would have been a generous analysis. But—like the hundreds of other immigrants who came to lead many of Chicago’s top manufacturing companies—Briskin had a certain grit and determination that seemed to render any odds-making irrelevant.

By the age of 20, he’d found himself a metal working job in Chicago, and a new bride, Bessie. By the age of 30, he was a father of six, working at a factory in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, to put food on the table. Gobs of money still did not appear to be in his imminent future, but Sam had a rather daring plan. He would return his family to Chicago and start his own company, making car radiators—an industry in which he’d developed some expertise as a repairman.

The Excel Auto Radiator Company [sometimes incorrectly called the “Excel Radiator Company”] started operations in the early 1920s, and soon benefited from Samuel’s skillful salesmanship. Headquartered at 1827 S. Michigan Avenue through its first decade, the company managed to win contracts with Sears-Roebuck, Montgomery Ward, and Western Auto, leading to rapid growth and additional plants in Dallas, Kansas City, Oakland, Minneapolis, and Philadelphia.

[Classified ad for the Excel Auto Radiator Co., 1928]

Sam Briskin hoped his newfound success would give his kids a far better childhood than the one he’d endured, but wealth wasn’t a shield for tragedy. In 1922, his daughter Ruth died at the age of six, and in October of 1929, four days before the stock market crash, his eldest daughter Lena passed away at 17. It’s unclear what the causes of death were, but many years later, when Sam Briskin became the largest single donator to the Babe Ruth Cancer Fund, his comments to the press offer us some possible insight.

“My boys and I loved Babe Ruth,” he said. “We knew the disease that killed him—it has struck among our relatives and friends.”

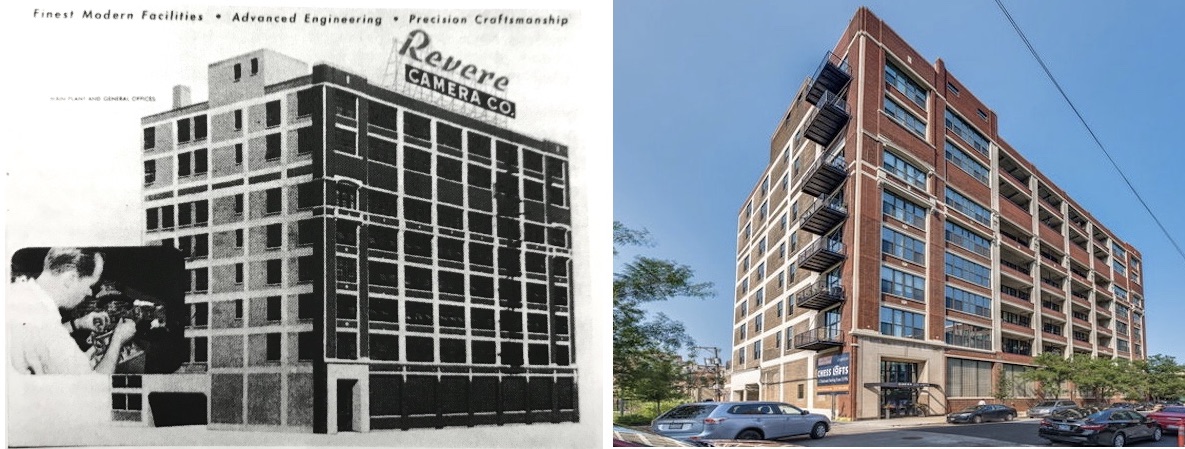

Fortunately for the surviving Briskin children, their father’s radiator company was one of the few manufacturing businesses to remain profitable during the Great Depression, expanding into a major new factory space at 320 E. 21st Street in 1933. Sam Briskin, by the age of 45, had become a self-made millionaire; several years before the idea of a camera company had even entered his mind.

[The former Excel Auto Radiator and Revere Camera building at 320 E. 21st St. It briefly became the home of Chess Records in the late ’60s, and was redeveloped into an apartment complex in 2010.]

II. Revere’s Ride

The actual impetus for the creation of the Revere Camera Company is a bit hard to pinpoint. According to one story, Sam Briskin simply overheard someone talking about how expensive Bell & Howell’s home movie cameras were, and with a bit of hubris, decided to build his own and undercut the competition. Other reports suggest the start-up was a passion project of Sam’s son Teddy, who liked going to the movies and found the industry a lot more interesting than car radiators.

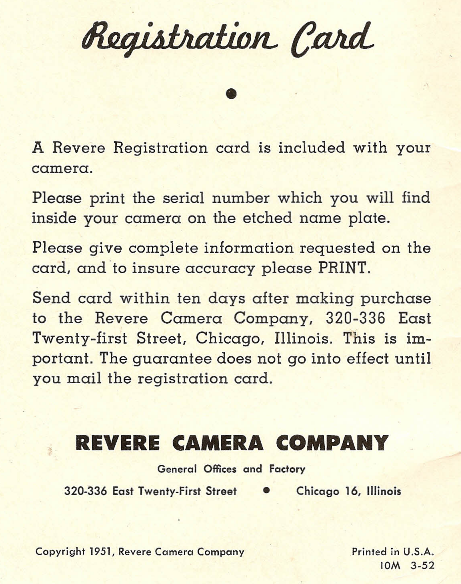

Whatever sparked the idea, Sam Briskin officially organized his new company in 1939 and called it “Revere,” supposedly as an homage to New York’s Revere Copper & Brass Inc., a leading and loyal supplier to the Excel Auto Radiator Co. during the Depression. Since Revere Copper was founded in 1801 by Paul Revere himself, I suppose—in a roundabout way—that Revere Camera was also named after the Revolutionary War hero.

Whatever sparked the idea, Sam Briskin officially organized his new company in 1939 and called it “Revere,” supposedly as an homage to New York’s Revere Copper & Brass Inc., a leading and loyal supplier to the Excel Auto Radiator Co. during the Depression. Since Revere Copper was founded in 1801 by Paul Revere himself, I suppose—in a roundabout way—that Revere Camera was also named after the Revolutionary War hero.

From the beginning, Briskin certainly seemed to treat the Revere Camera Company as a sort of “training wheels” business for his young sons: Phil (25), Ted (21), and Jack (17). Each was given a one-third stake in the company, and cinema fan Ted was gifted the role of president. Papa Sam, as Chairman, kept just 5 percent of the Revere stock for himself, and continued to focus on the established radiator empire. It’s highly unlikely he realized just how high Revere’s ceiling truly was.

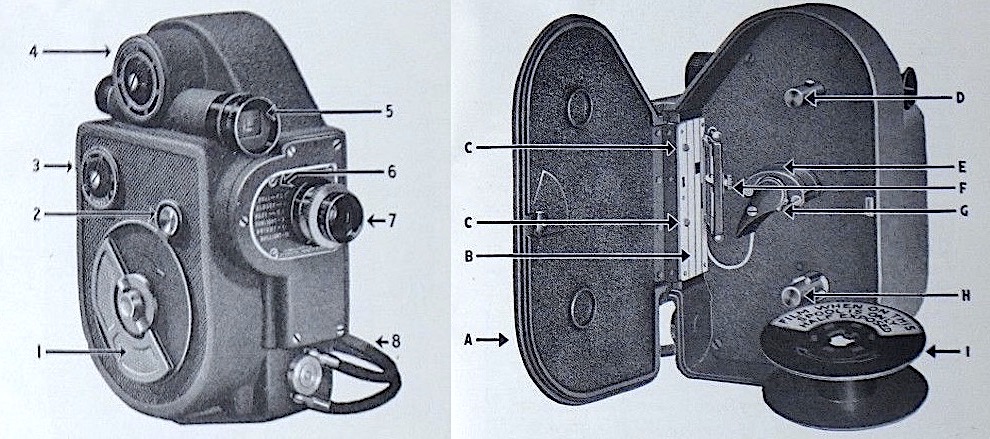

The company’s original home office was located at 33 N. LaSalle Street, but it soon came to occupy more and more space inside the Excel Auto Radiator plant at 320 E. 21st Street. By 1940, just a year into operations, Revere was producing its first Model 88 movie cameras—a new take on the conventional “double 8” cameras already on the market. Like Bell & Howell’s “Filmo Companion” model, it was pocket-sized and featured an exterior winding key, a sprocket for threading the spool of film, and a wrist cord. A full wind-up would generate about two solid minutes of filming time. After that, you’d have to remove the film, reverse the spools, and shoot your next two minutes. There were, of course, also various confusing options for speed choices (go with 16), focus, exposure, etc.

[Parts of the Model 88 Camera: 1-Winding Key, 2-Operating button, 3-Speed control dial, 4-Adjustable footage meter, 5-Objective view finder, 6-Lens plate, 7-Lens, 8-Wrist cord. A-Camera door, B-Aperture Plate, C-Film Guides, D-Upper spindle, E-Sprocket guide, F-Film gate catch, G-Sprocket, H-Lower spindle, I-Take-up spool]

[Parts of the Model 88 Camera: 1-Winding Key, 2-Operating button, 3-Speed control dial, 4-Adjustable footage meter, 5-Objective view finder, 6-Lens plate, 7-Lens, 8-Wrist cord. A-Camera door, B-Aperture Plate, C-Film Guides, D-Upper spindle, E-Sprocket guide, F-Film gate catch, G-Sprocket, H-Lower spindle, I-Take-up spool]

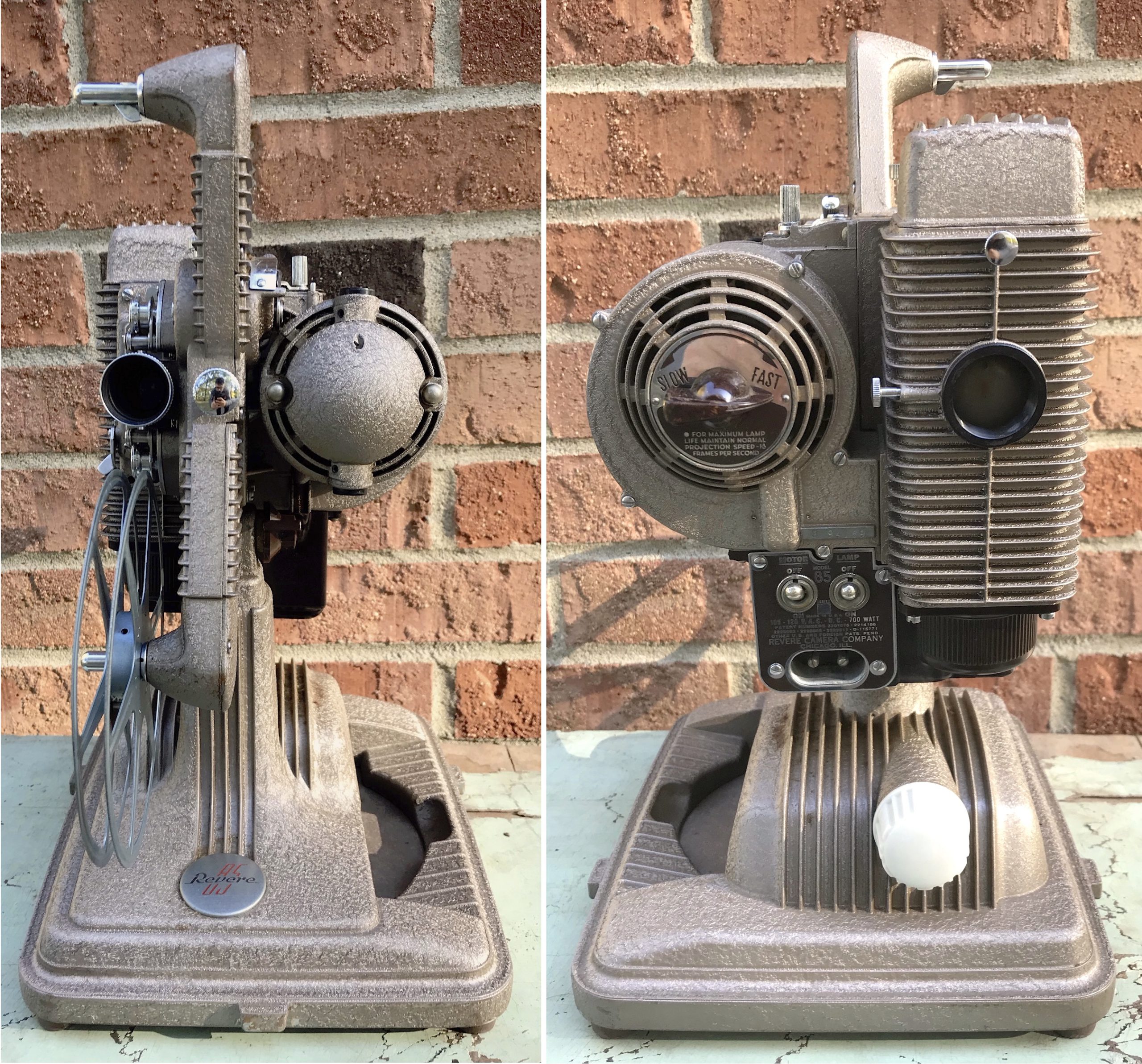

The key innovation was the price tag; while the B&H Companion was going for about $50 before the war, Revere offered the Model 88 for just $30. The Revere silent film projector was an even better bargain at $60, about half the B&H rate.

These gaps might suggest that Revere products were literally half-rate in quality, as well, but the Briskins didn’t half-ass anything. They developed a strong R&D team and looked for efficient production methods to cut costs while still producing reliable equipment. It all paid off in soaring sales numbers—right up until America’s entry into World War II put the entire commercial camera business on indefinite pause.

These gaps might suggest that Revere products were literally half-rate in quality, as well, but the Briskins didn’t half-ass anything. They developed a strong R&D team and looked for efficient production methods to cut costs while still producing reliable equipment. It all paid off in soaring sales numbers—right up until America’s entry into World War II put the entire commercial camera business on indefinite pause.

The Revere factory dutifully repurposed itself for defense sub-contracting both during and after the war, producing wing actuators, screw machine parts, precision gears, and cameras designed exclusively for military use. The U.S. government wouldn’t officially relieve Revere of its obligations until 1948, but the Briskins had fully prepared for their peacetime renaissance in the civilian market.

“Obstreperous Sam Briskin has given the old-time outfits a rude shock,” Fortune reported in its July issue that year. “His Revere Camera Co. is advertising like mad and flooding the market with low-priced, slick-looking, and entirely satisfactory cameras and projectors. If it continues its spectacular growth it may even displace Bell & Howell as the largest dollar volume producer.”

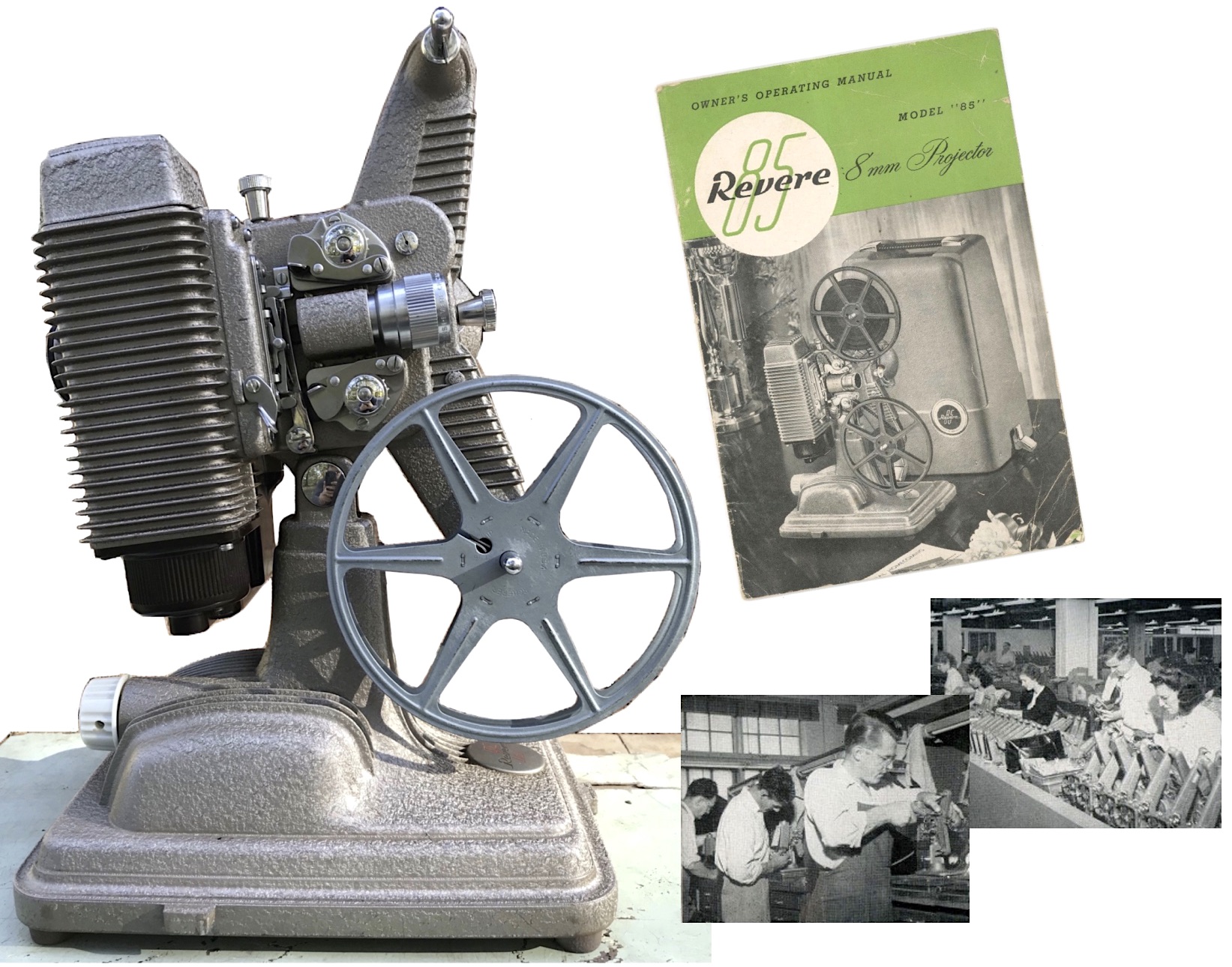

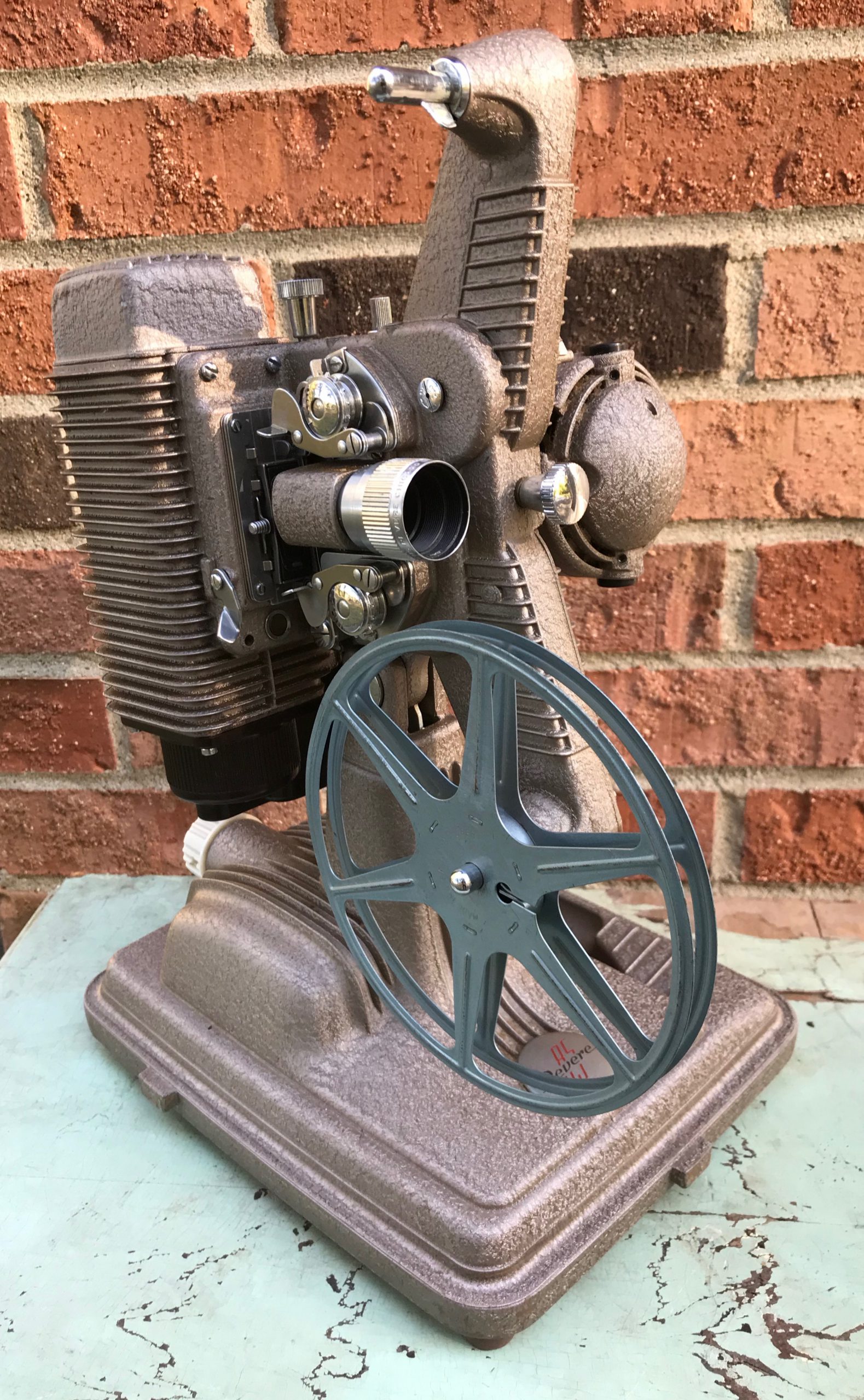

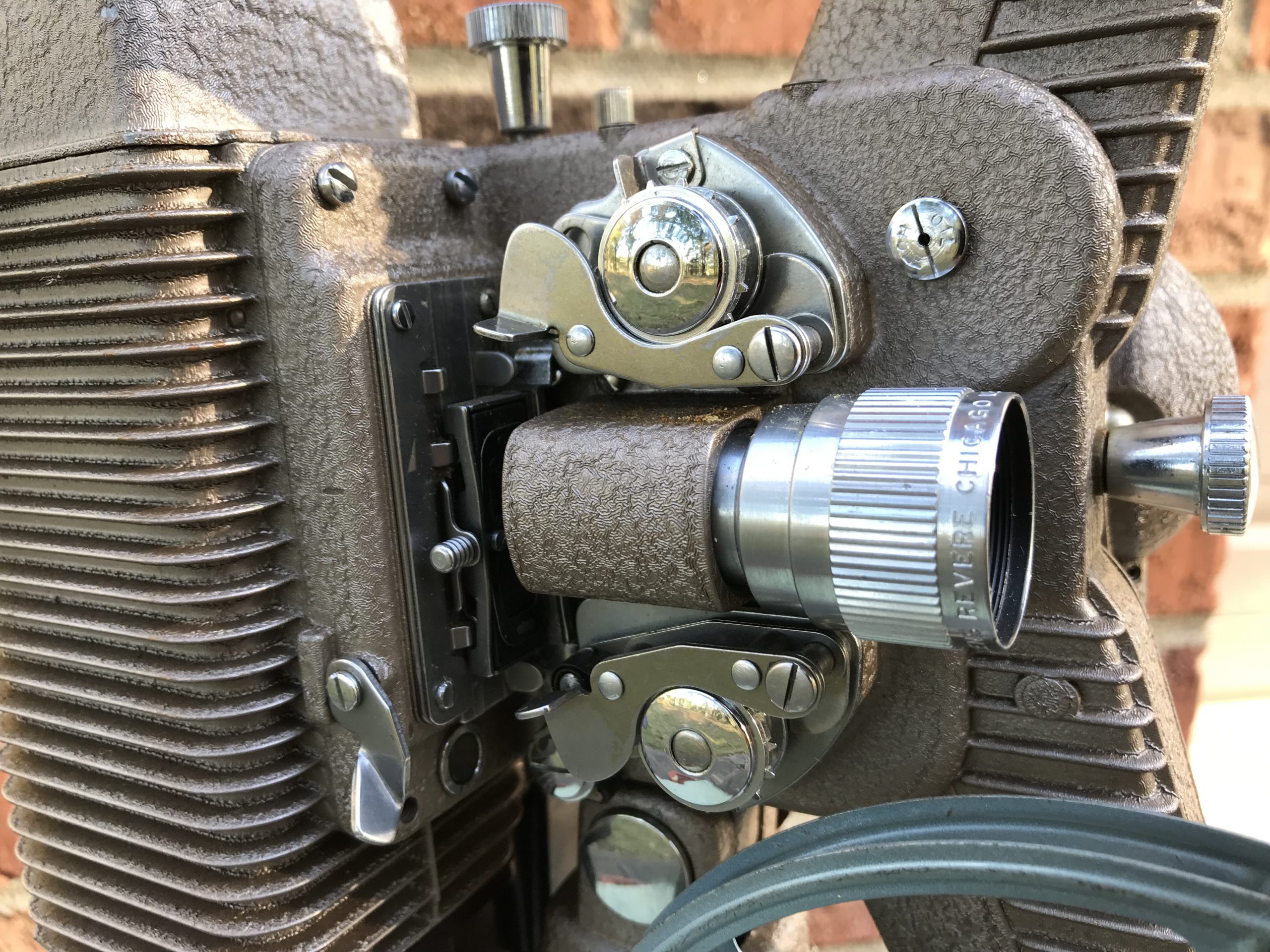

[The Made In Chicago Museum collection also includes this Model 85 Revere Projector, a top seller in the post-war 1940s. “The exceptional quality of your Revere ’85’ Projector is evident in every detail of design and performance,” according to a user manual. “You will find that it combines operating ease with ‘theatre quality’ projection to an unexcelled degree.”]

[The Made In Chicago Museum collection also includes this Model 85 Revere Projector, a top seller in the post-war 1940s. “The exceptional quality of your Revere ’85’ Projector is evident in every detail of design and performance,” according to a user manual. “You will find that it combines operating ease with ‘theatre quality’ projection to an unexcelled degree.”]

That same year, 1948, Sam Briskin brought a $3 million lawsuit against the undisputed giant of the industry, Eastman Kodak, accusing them of monopolizing the sale and production of 8mm color film. It was a cocky move for a relative newcomer to the photo field, but it was also a clear indication that the old radiator man had firmly shifted his focus to movie cameras.

Within another few years, the Excel Auto Radiator Company [which, confusingly, never had any connection to the Excel Movie Products Inc., another Chicago manufacturer of film projectors] was sold off, and its workers were absorbed into Revere’s ever-expanding roster. The most famous member of that roster, however—the golden child Teddy Briskin—was becoming a saga unto himself.

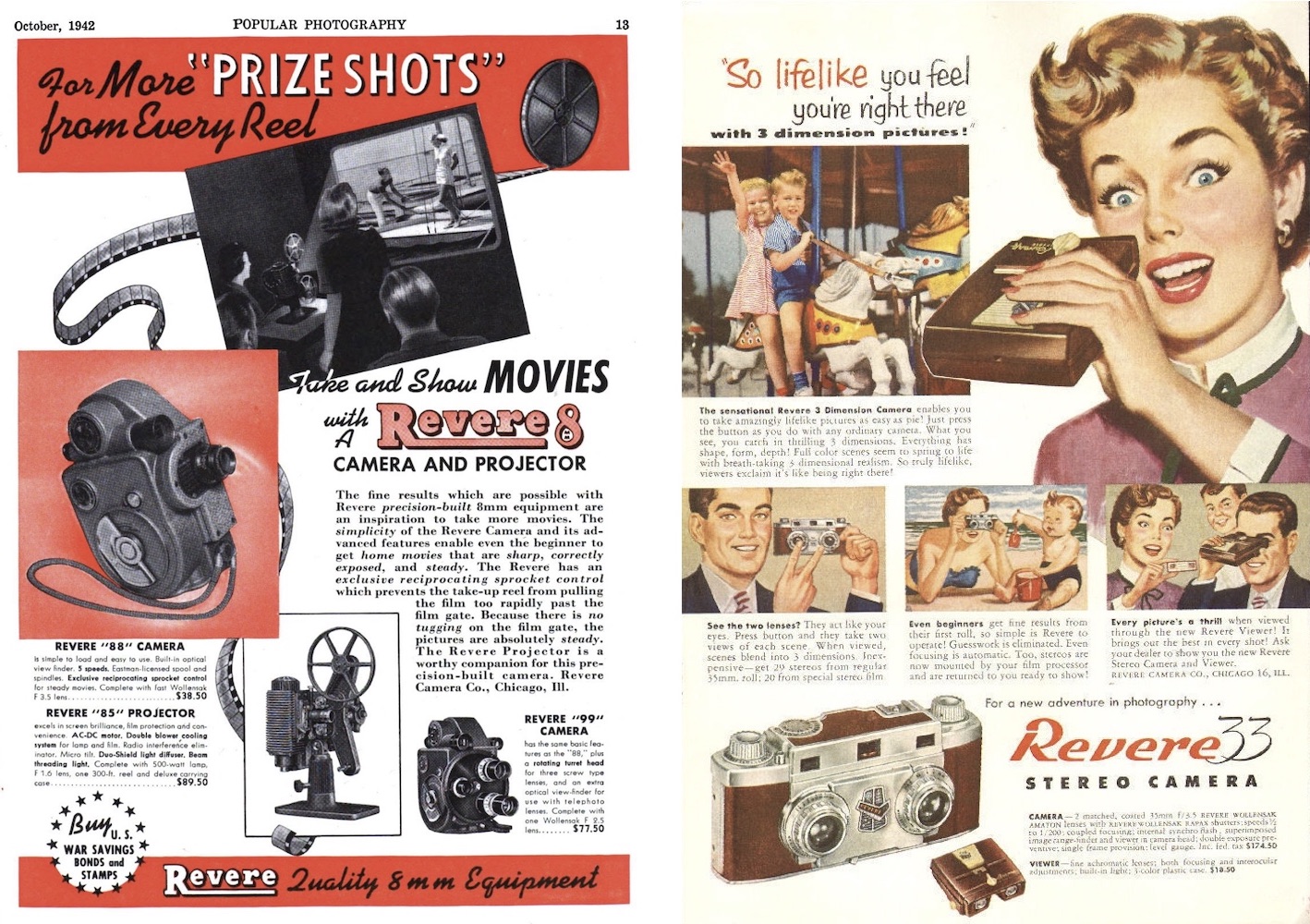

[The Revere 8mm products in 1942 (left) and the Revere33 Stereo Camera in 1953 (right)]

[The Revere 8mm products in 1942 (left) and the Revere33 Stereo Camera in 1953 (right)]

III. Right Said Ted

“Isn’t he handsome? Isn’t he rugged? I could never find anything like that in Hollywood. I had to go to Chicago. Great town, Chicago. Say, you ought to try this married life. It’s the only way to live!” –actress Betty Hutton, quoted during a party at the Beverly Hills Hotel, October 1945.

During those same post-war years when the Revere Camera Company was threatening to become America’s No. 1 home movie camera maker, Ted Briskin was evolving from millionaire bachelor to Hollywood husband. When not promoting Revere cameras around the Midwest, he was flying back to L.A. to be with his new bride, the A-List singer and actress Betty Hutton—she of Annie Get Your Gun and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek fame.

During those same post-war years when the Revere Camera Company was threatening to become America’s No. 1 home movie camera maker, Ted Briskin was evolving from millionaire bachelor to Hollywood husband. When not promoting Revere cameras around the Midwest, he was flying back to L.A. to be with his new bride, the A-List singer and actress Betty Hutton—she of Annie Get Your Gun and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek fame.

“I’ve talked to a lot of newlyweds during the many years I have been writing on movie marriages,” famed Hollywood scribe Louella O. Parsons wrote in 1945, “but I doubt if I’ve ever seen anybody as ecstatically happy as Betty and her Chicago groom, the very good looking Ted Briskin.”

Ted and Betty had met at a Chicago restaurant called the Singapore, where they proceeded to dance the night away in a scene straight out of the sappiest ’40s musical.

“You know,” Betty told Louella Parsons with a giggle,” I still thought he was probably a gangster or married, and I insisted the next day that he show me the plant where he manufactured cameras, which he said he owned. I kept saying to myself: Nothing like this could happen to me. There must be something wrong with him. But there’s isn’t a thing in the world wrong with him. He’s perfect!”

Not surprisingly, Betty would eventually change her tune on that front, but in the short term, a wedding was quickly in the works—a development not eagerly embraced by the Briskin clan, who had to shoo away tabloid reporters from the Chicago factory.

Not surprisingly, Betty would eventually change her tune on that front, but in the short term, a wedding was quickly in the works—a development not eagerly embraced by the Briskin clan, who had to shoo away tabloid reporters from the Chicago factory.

“My family,” Ted Briskin admitted to Parsons, “were yet to be reckoned with. To them, marrying an actress from Hollywood was something nobody in our family had ever done or believed possible. But my 96 year-old grandmother, who still rules the family, said ‘If you want to marry Betty, go ahead!’ But I don’t suppose anything in the world could have kept me from doing it.”

I suppose that could be interpreted as a romantic statement of devotion, but to Ted’s Chicago brethren, it was more of an unceremonious brush-off. Not only was Ted marrying outside the Jewish faith, but he also swiftly abandoned his Revere obligations for the West Coast, where he proceeded to go into direct competition with his father, launching his own Briskin Camera Company in 1946, with Betty Hutton as his vice president.

[After modeling in Bell & Howell camera ads just two years earlier, Betty became the face and VP of the new Briskin Camera Co. in 1947]

[After modeling in Bell & Howell camera ads just two years earlier, Betty became the face and VP of the new Briskin Camera Co. in 1947]

The “Briskin 8” movie camera included an easy magazine load feature, and was well publicized in the late 1940s. But by 1950, both the new company and Ted’s marriage were already on the rocks. A high-profile divorce was followed by a high-profile reconciliation (Briskin and Hutton had two children together), but ultimately the whole house of cards collapsed, and a second divorce followed a year after the first.

A few years later, Hutton attributed the failed marriage(s) to communication problems; Ted was “cultured and educated,” while she was a high school dropout. “You see I hadda fight hard all the way up,” she said. “Sometimes I said things that shocked Ted and I didn’t mean to.”

This was the kind of thing a woman might say in the 1950s, but in her actual divorce proceedings, Hutton cited “mental cruelty” from Ted as the actual crux of the fallout.

In the aftermath, Ted Briskin returned to Chicago with his tail between his legs. He went back to work for his dad at Revere, but soon fell back into old habits. In October of 1952, he eloped with 22 year-old actress Joan Dixon after their very first date. That marriage, surprise to no one, tanked within a month. Three years later, Briskin married 23 year-old Colleen Miller [pictured], an actress with Universal Studios. Third time, it seems, was the charm, as the two remained hitched for 20 years.

In the aftermath, Ted Briskin returned to Chicago with his tail between his legs. He went back to work for his dad at Revere, but soon fell back into old habits. In October of 1952, he eloped with 22 year-old actress Joan Dixon after their very first date. That marriage, surprise to no one, tanked within a month. Three years later, Briskin married 23 year-old Colleen Miller [pictured], an actress with Universal Studios. Third time, it seems, was the charm, as the two remained hitched for 20 years.

Ted Briskin certainly embraced all the benefits that his father’s achievements had afforded him, but ultimately, he never quite realized his own lofty goals in the camera business or in Hollywood. By 1953, it was his younger brother Jack who was serving as Revere’s president, with eldest brother Phil as VP.

IV. Overexposure

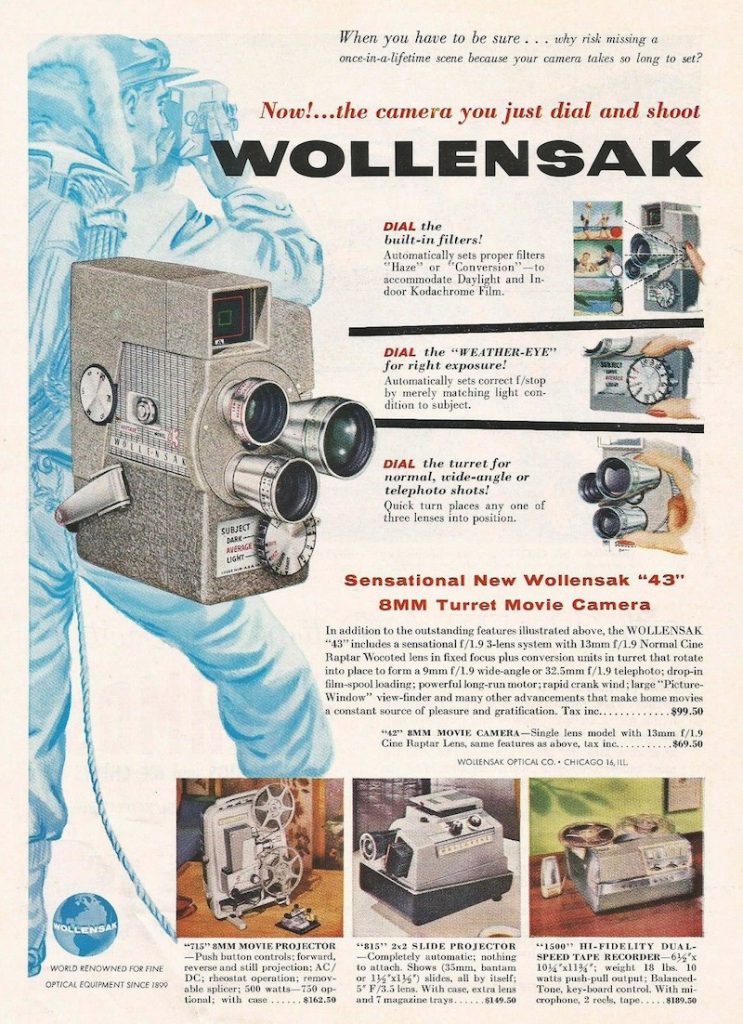

By the time Ted Briskin rejoined the Revere fold in the early 1950s, the company was already beginning to lose ground in the marketplace, as Bell & Howell had finally punched back with its own line of cheaper 8mm cameras and tape recorders. In response, an aging Sam Briskin made arguably his boldest move yet, purchasing the Wollensak Optical Company of Rochester, New York; which had previously been Revere’s independent lens provider.

Besides giving Revere almost total control over all the components of its cameras, the acquisition of Wollensak also set the table for Sam and his sons to enter the high-end market for the first time. In 1953, they introduced a new line-up of movie cameras bearing the Wollensak brand name. They were, in truth, virtually identical to the co-existing Revere models, but were marked up in price and spruced up for marketing purposes. Basically, if Bell & Howell was now willing to go low to win the camera wars, Revere had to prove they could sell high.

Besides giving Revere almost total control over all the components of its cameras, the acquisition of Wollensak also set the table for Sam and his sons to enter the high-end market for the first time. In 1953, they introduced a new line-up of movie cameras bearing the Wollensak brand name. They were, in truth, virtually identical to the co-existing Revere models, but were marked up in price and spruced up for marketing purposes. Basically, if Bell & Howell was now willing to go low to win the camera wars, Revere had to prove they could sell high.

The new venture was a mixed bag. The respected Wollensak name did, indeed, help move product. But as the ’50s carried on, Revere simply didn’t have the resources to keep up with B&H, Kodak, or any of the other larger corporate powers in the industry. Public interest in 8mm cameras was steadily dropping anyway, and Revere no longer had novelty or pricing on its side. Sometimes, in its efforts to leapfrog its competitors, the company bit off more than it could chew, and only wound up falling further behind as increasingly advanced automatic camcorders became the norm.

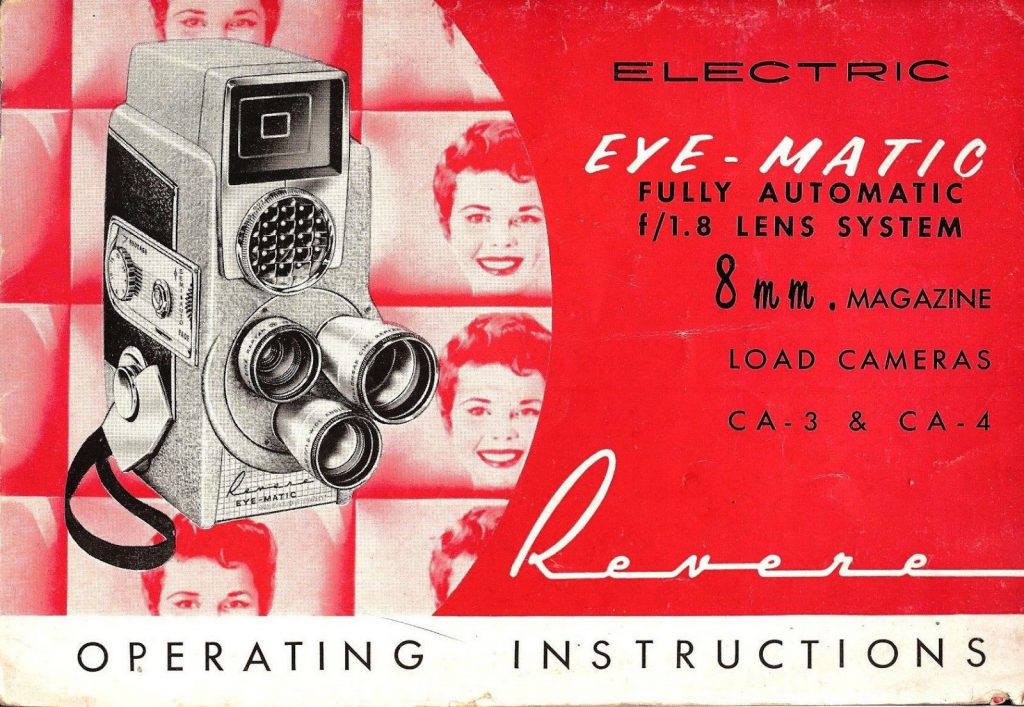

[Manual for the Revere Electric Eye-Matic camera, 1958]

[Manual for the Revere Electric Eye-Matic camera, 1958]

In 1960, after many years donating his time and money to cancer charities, Sam Briskin [pictured below in his later years] was afflicted with the disease himself. He was nearly 70 years old, and was faced with a difficult decision. He could either pass the fate of the family business on to his sons—as had presumably been the plan for the years—or, recognizing Revere’s downward trajectory, he could hit the eject button.

In the end, for reasons we’ll never fully know, he chose the latter. Revere and all its subsidiaries, including Wollensak, were sold to Minnesota’s 3M Company in the summer of 1960 for about $20 million; with the tape recorder business representing the prime focus of the deal. Sam Briskin died the following year.

In the end, for reasons we’ll never fully know, he chose the latter. Revere and all its subsidiaries, including Wollensak, were sold to Minnesota’s 3M Company in the summer of 1960 for about $20 million; with the tape recorder business representing the prime focus of the deal. Sam Briskin died the following year.

During the sale to 3M, it was Ted Briskin, interestingly enough, who took a lead negotiating role. It was also Ted who stayed on as Revere’s vice president after the buyout, while brothers Phil and Jack (both known to date a blonde model or two in their own right) left for greener pastures.

Ted tried to keep the spirit of the old Revere brand alive in the ’60s, but under 3M’s meager management, the company continued its steady decline. The 21st Street plant was sold within a few years, and was briefly occupied by Chess Records in the late 1960s. By the early ’70s, the Revere name was put to bed for good. Ted Briskin died in 1980, five years after separating from Colleen Miller.

The fact that the Model 88 in our museum collection has suffered some noticeable bumps and bruises (it was an estate sale find) seems fitting. This was a company started in humble fashion, sold to the everyman, and generally overlooked in the history of home movie making. Sure, maybe Ted Briskin got distracted by silver screen starlets and let Bell & Howell beat him in production. And maybe his father invested money in the community, but not enough in innovation. Whatever the reasons for Revere’s second class status, it remains an inarguable American—and Chicago—success story; a business that pushed its competitors to make movie-making available to the masses.

P.S. – It should be noted that Revere’s Samuel Briskin is an entirely different person from Samuel J. Briskin—a leading Hollywood film producer during the same era.

[Ted Briskin and Betty Hutton with Bob Hope, c. 1950]

[Ted Briskin and Betty Hutton with Bob Hope, c. 1950]

SOURCES

“Divided Classes Comprise Most Hollywood Parties” by Bob Thomas, syndicated column, October 20, 1945

“Revere Camera Co. vs Eastman Kodak Co.” – United States District Court, N.D. Illinois, E.D, Oct 5, 1948

“From Now On Betty Hutton Will Lead Double Life” – St. Petersburg Times, Feb 7, 1946

“Actress Wins Divorce” – Evening Sun (Baltimore), April 5, 1950

“Ted Briskin Marries Actress for Third Wife” – L.A. Times, Jan 21, 1955

Home Movies: A History of the American Industry, 1897-1979, by Alan Kattelle, 2000

“In Hollywood with Louella O. Parsons” – October 28, 1945

“3-M May Buy Briskin Firms” – Billboard, July 4, 1960

Archived Reader Comments:

“Thank you for posting this article Andrew Clayman, good read!

Ryan Briskin

Richard Briskin’s son,

Ted Briskin’s grandson!” —Ryan Briskin, 2020

“Wonderful overview of the Revere Camera Company! As a designer and collector, I am curious to know who was responsible for the industrial design for the various cameras. In my collection I have the model 55 and it’s an interesting piece of industrial design. Thank you for any information.” —Michael Zambelli, 2020

“Sam Briskin was a compassionate man & treated his employees like family. He gave all employees a large box of chocolates each time a new grandchild was born. My sister (who has passed). Worked in the office in the 1940s. Phil the oldest son asked her out but she turned him down? Great place to work!” —Joanne Kohler Stevenson, 2019

“This is Richard Theodore Briskin and I just wanted to reiterate my father Ted arranged to 3M deal, I remember him telling my mother COLLEEN still alive today and my sister Robin and I about the 3M deal even though he spearheaded that sale for 60 million he had previously sold his stock in Revere to move his last wife Colleen and his only daughter Robin and me his only son Richard to California where he worked for 20 years inventing and patenting a cigarette that burns tastes ashes just like a marlboro with absolutely no carcinogens. The patents were sold to Phillip Morris and Reynolds tobacco. You can Google the patent and see the names and patents. Of course it was never produced and locked away.” [edited by request] —Richard Briskin, 2017

The first Revere camera was The REVERE SUPER8MM CINÉ CAMERA, MODEL C8 SINGLE 8 (sic), released in 1939. That is a camera for 8 mm wide stock on 30-foot spools. It else has the same features as the successor Revere 88, 99, and Ranger. Bell & Howell had launched the first Straight Eight Filmo in 1935. In 1936 came the Univex A-8 from New York. Agfa put the Movex 8 on the market in 1937, the first Straight-Eight camera to be loaded with a cassette.

I found a Revere “85” projector in excellent condition in my mothers things, any idea what it would be worth or what to do with this projector?

My father, S. Lee Pastor, designed Wollensak tape recorders. In January of 1963, he moved his team, Revere Mincom, to St Paul, MN to work for 3M and design background music systems. While at Revere, he earned 50 patents.

After he passed in 1998, we donated his patents and many of his tape recorders to the Pavek recording museum in Minneapolis MN.

I haver a Revere made for the Wollensak Optical CO. Model 57 S# 75 2687

it appears to be in working condition, after many searches have not found this Model #

Looking for any information I can obtain an a possible value if any.

My name is Fran Foderaro, my father, Anthony J. Foderaro was a transformer engineer for Midwest Coil and Transformer Corp. in Chicago. In his job he would have to visit suppliers of products used in transformers. He visited 3M in about 1960 or ‘61. 3M actually gave my father a 35mm EE127, Electric Eye camera as a gift. Or Dad loved that camera taking pictures at our yearly fishing trips to Eagle Lake Ontario, Canada. Sadly, two years in a row for some very odd reason the camera gave my Dad fits as it would not work. The second year, my Dad sat at the table in our cabin for what seemed like days! After that long stay, Dad quietly got up, walked to the gigantic rock at the foot of the lake and threw it as far as he could.

The camera sits there in about 15-20 ft. of water. Now, my five children have been there over the decades and now with their children. My oldest son and his wife scuba dive. They promise that before I leave this life that they will retrieve it. I got a very good one on eBay along with the instruction manual.

My Dads colorful expletives ring in my ear every time we are at that giant rock. Of course I am committed to repeat this family story every time we are there.

Hello,

I’ve recently inherited my father’s Revere Eye-matic Magazine Eight Model CA-8, NO. 8. I can’t find any information about this model anywhere on line and would love to know more. If anyone has information about it I’d appreciate it. Thanks! Barb

Hello: I have a Wollensack 1580 Stereophonic Tape Recorder and to day it finally broke down. Can you tell me who could repair this? I bought it new in 1964. Thank You Joe

about what years was the revere magazine 16mm model 26 made?

I have a VERY large collection of Revere cameras and projectors.

Included in my collection are several models of the “C8” which was before the Revere 88.

That camera has a patent number which is NOT for the camera but for a camera lens made by someone else !

I also have collected other non-camera items such as the Revere radio, a Revere 1/4 inch drill

and the hand held rotary drill kits.

I also have the Briskin cameras and the cameras sold under other names.

Would ther be someone who would like to talk to me?

Charles Crehore

480-9487166

I have a Model 80 Revere Standard 8MM Projector and would like to determine its value. It still works when plugged in and all the parts are in good condition. My estimate is that is about 75-80 years old. I do not want to join your association or pay you any money for this – just someone who could give me a “ball park” estimate via e-mail as to its worth.

John Siegfried

My father Robert L. MOORE I believe designed many of the lens and cameras and recording equipment for Revere. It’s surprising to never hear about him there. He was brilliant and invented many patented things for himself and many other companies. Later in life the Japanese would call him when there scientists or engineers could not figure something out. He always did. He still designed for other companies thru his 80s. To bad so many true inventing engineers never get the credit for without them there would be nothing to sell.

I very much agree, Bobbi. We’d love to shine more of a light on engineers. If you have a photo of your father and any other info related to his work with Revere we’d be glad to incorporate some of it into this article. –Made In Chicago Museum

I have the first Revere camera produced, it’s a Super 8 model C8. It’s a single 8 design and I think they only made it for a year before upgrading to the 88. It was my grandfathers who was something of a shutterbug back in the day. He said after a while they no longer sold the old 8mm single film stock and he had to split 16mm in the darkroom to use in this camera. The camera is in excellent condition and IMO would be an excellent addition to the Made in Chicago collection. I’d like to donate it the museum. If your interested, just let me know.

Hi –

I have my mother’s Revere 16 mm. “Magazine Cine Sixteen, Model 16” camera. It’s a beautifully designed artifact and a sentimental family heirloom. I’m doing research on it and found this article fascinating.

Do you know what year this model was produced and/or do you have a resource you could refer me to to find out? THANKS.

Thanks.

m. Brandt

I have my late dad’s Revere Magazine 16 with me in working order here in Sydney. Not sure when it dates from but we had it with us on a home built mobile caravan trip from Cape Town to Victoria Falls back in 1967

Ted’s two eldest daughters would be surprised to read Richard Theodore Briskin’s comment stating that Ted’s “only daughter” was Robin! Ted had two daughters by his first wife, Betty Hutton … they are Lindsay Diane Briskin and Candice Elizabeth Briskin. #settingtherecordstraight

Hello from Italy,I have a Revere TRS 850 rtr recorder,with AM-radio,bought from my father in 1953,at Genoa(importer for ITALY:”Ciastraco”-Capriotti);on the magnetic head casing it’is a plate “licensed from Armour Foundation”: what’is Armour F.?

Thank you!

Dario Pisani

Mod# t2000

Sr# 4116

What is it

I have a Revere 87 8-mm camera my dad was using in early 50s when I was young. In the article above it the 85 & 88 models are discussed but not the 87. When was it made? Anything different about it? Unfortunately, the light bar that was used with it I threw away some decades ago. Thanks

Hi

I have an old REVERSE 55 8mm Camera and I would like to know the value today.

In 1956 while in S. Francisco I bought a Revere D888 slide projector. for 150 US dollars. It was then the best slide projector on the market. I still have it in perfect working order and it was fun that I saw in the net a similar projector for sale in 2007 for 15 Us Dollars! I bought it and after some carefull diy work I have it working flawlessly like the other one bought 51 years earlier!

So much for the quality of manufacture of those equipments!

Hello,

My father has passed a few years ago, and I found on his belongings this Revere câmera model 88!

I would like to know how much does it sell on the market !

Thank you

Best regards

Karla

I Own a Revere Model 80 8mm Projector and it’s in working order and one of my favorite Projectors. Very well made. I also own a Revere 16mm Projector from the 1940’s and it’s well made and in working order. Two of my favorites to use. Thanks, Eugene

https://www.facebook.com/shoutoutvideos

Thank you for this article! My father worked at Revere Camera in the 1950’s until his death December 7, 1963. His name was Paul Jurich 40 yrs old. Thank you! He spoke highly of Revere!

Maryetta (Jurich) Christie 08/26/2020

I have an Revere -Eight 85″ projector copyright 1948 which is in very good condition, do you know what the value would be? I also have the original case with an owner’s manual

My Father was Philip F Briskin, the oldest son of my Grandfather Sam Briskin. My Father was Vice-President of Revere Camera Company. I am Melanie Elizabeth Briskin an entrepreneur myself and owner of Florida Seashells and Fossils LLC in Cape Coral, Florida. I was Born and raised in Chicago and left there to move to Florida with my mother Betty Boyles Briskin in 1978-79. I am very proud of my family heritage. My Grandfather Sam Briskin was from Ukraine-Kiev Russia and left there many years ago with my Grandmother Bessie Briskin. He was a very hard working and smart business man and started from a vegetable cart and later to owning Excel Radiator and Revere Camera Company.

I have a revere eight 60 turret magazine camera with all instructions and case. Is it worth anything?

How muck is the 88mm 85 projector worth in today’s narket