Museum Artifact: Shotwell’s “Car-Load” and “Miniature Chocolates” boxes + Shotwell’s “Popcorn Brittle” & “3-to-1” Wax Candy Wrappers, 1920s

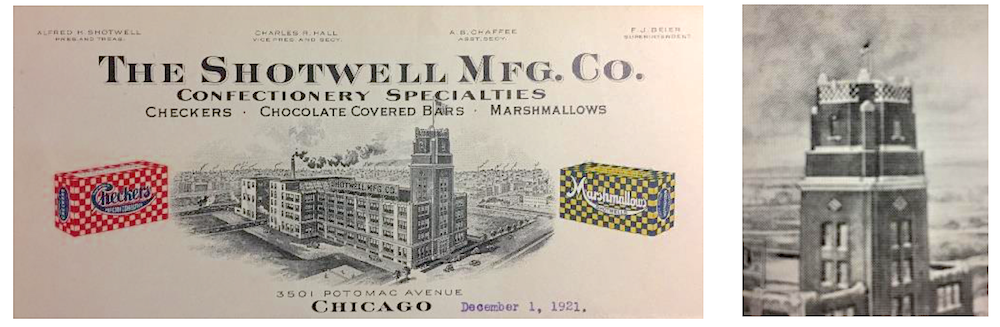

Made By: Shotwell MFG Co., 3501 W. Potomac Ave., Chicago, IL [Humboldt Park]

The Shotwell Manufacturing Company is one of Chicago’s forgotten confectionery giants; a former popcorn, candy bar, and marshmallow maker that operated from 1903 to 1952. The firm was notably opportunistic in its business practices—sometimes a tad shady even—and it wouldn’t achieve the longevity or cultural relevance of local rivals like Cracker Jack, Mars, or Brach’s. Even so, subscribers to the Shotwell doctrine still like to credit the company with at least a few major innovations of note, including the first athlete-sponsored candy bar (the Red Grange Bar, 1926) and the first boxed candy with a secret prize inside (Checkers, 1909). The fact that both claims are potentially dubious certainly shouldn’t deter us from digging a bit deeper into this rarely told tale from the Chicago Candyland archives.

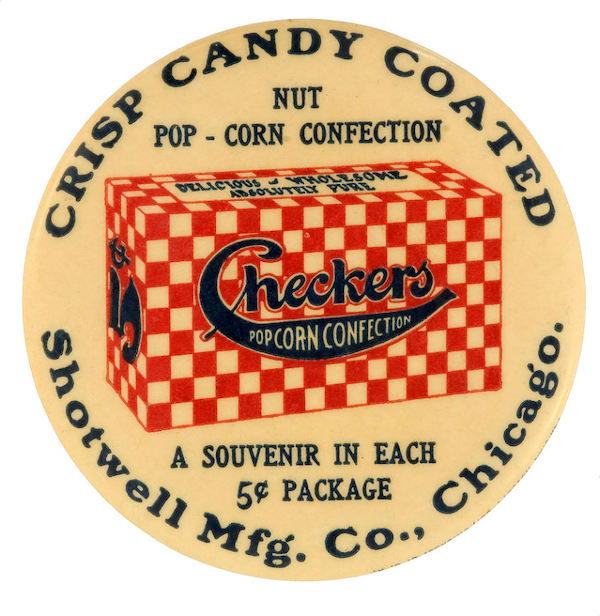

According to Alfred H. “Chip” Shotwell III, whose grandfather founded the Shotwell MFG Co. over a century ago, the family business once ranked as the third largest confectionery enterprise in America. This is hard to confirm, but certainly might have been true for a period in the 1920s, when Shotwell’s best selling product—the Cracker Jack knockoff known as Checkers Pop Corn Confection—was gaining ground on the genuine article. As no coincidence, the Cracker Jack Company eventually ponied up and purchased Shotwell’s entire popcorn operation in 1926, abruptly ending two decades of marketing battles between the two firms, and reducing the Shotwell line-up to its lesser known candy and marshmallow brands.

According to Alfred H. “Chip” Shotwell III, whose grandfather founded the Shotwell MFG Co. over a century ago, the family business once ranked as the third largest confectionery enterprise in America. This is hard to confirm, but certainly might have been true for a period in the 1920s, when Shotwell’s best selling product—the Cracker Jack knockoff known as Checkers Pop Corn Confection—was gaining ground on the genuine article. As no coincidence, the Cracker Jack Company eventually ponied up and purchased Shotwell’s entire popcorn operation in 1926, abruptly ending two decades of marketing battles between the two firms, and reducing the Shotwell line-up to its lesser known candy and marshmallow brands.

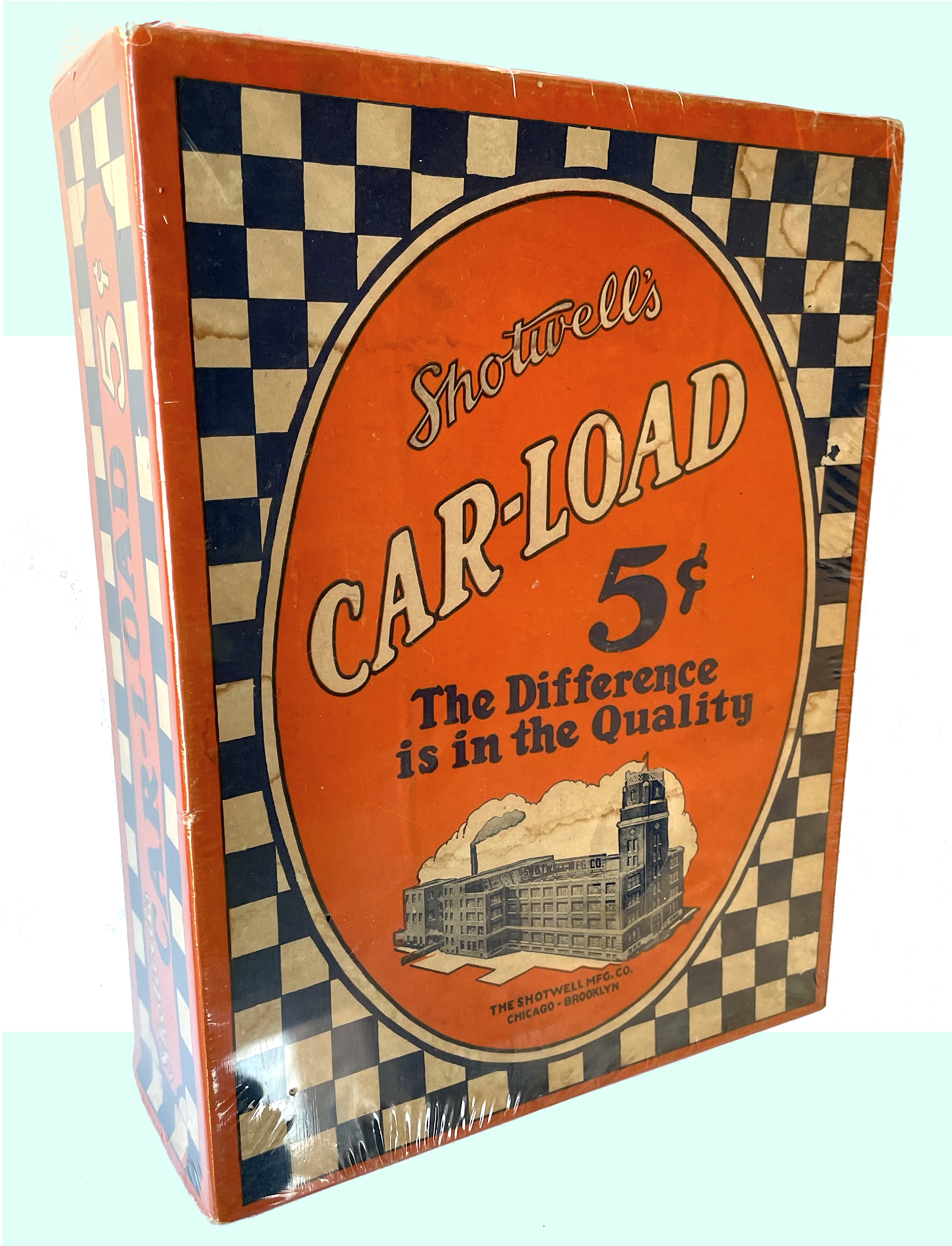

Interestingly, the three Shotwell products represented in our museum collection might have been direct casualties of that Cracker Jack sale, as the company looked to consolidate its product lines. The “Car-Load” chocolate bar—despite the very striking checkerboard display box featured at the top of this page—appears to have come and gone between 1926 and 1927. And the shelf-life was perhaps even shorter for Shotwell’s “Pop Corn Brittle” (with almonds) and a mysterious goodie called “3 to 1” (“Nothing Over 3”), both of which are advertised on uncut sheets of wax packaging in our collection, originally printed by Chicago’s Central Wax Paper Company. With essentially no supporting evidence of their existence in newspaper or magazine ads—or even any idea what the hell “3-to-1” contained or referred to—our best guess is that these brands might also have been in their infancy in 1926, and were swiftly abandoned once Cracker Jack swooped in and took over half of Shotwell’s business.

[The Made In Chicago Museum acquired some large uncut wax sheets, originally intended as packaging for Shotwell’s “Pop Corn Brittle” and “3 to 1” candies in the mid 1920s. Both brands appear to have been discontinued shortly after their creation. Also pictured above is a box of Shotwell Miniature Milk Chocolates, donated by Melissa Barker of the Houston County Archives & Museum in Tennessee.]

History of the Shotwell MFG Co., Part I: Alfred I

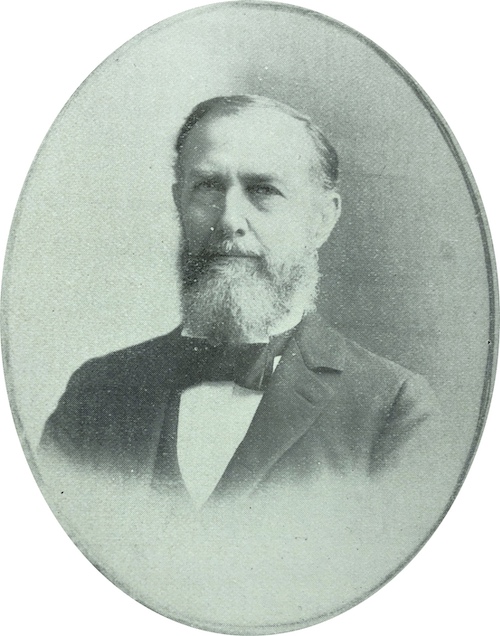

Alfred Shotwell, Sr., was something of a new arrival to Chicago when he launched his business in 1903. Born in West Point, Mississippi, in 1871, he was the son of a former Confederate Army colonel, Ruben H. Shotwell [pictured below], and grew up as one of the luckier kids of the Reconstruction. The family moved to St. Louis when Alfred was still a boy, and his father found some success there in the mercantile trade before becoming Secretary of the Police Board in the 1890s.

As late as 1900, 29 year-old Alfred was still living in St. Louis, as well, working in the higher ranks of a carriage manufacturing business. How or why he wound up in Chicago—pondering popcorn snacks—is anybody’s guess, but according to family lore, Shotwell soon became good pals with Harry G. Eckstein of Rueckheim Bros. & Eckstein . . . the makers of Cracker Jack. This friendship, in turn, supposedly entitled Shotwell free access to Cracker Jack’s Chicago factory, where he hatched the idea of carving out his own company in the same mold.

The fact that Alfred ultimately went into business producing a packaged, candied popcorn snack—almost identical to Cracker Jack—sounds a bit more like thievery than mere homage. And indeed, Rueckheim Bros. & Eckstein eventually sued Shotwell for patent infringement over the formula and sealed packaging used for “Checkers.”

If you believe the stories Alfred’s descendants later relayed to candy historians Fred and Harriet Joyce, however, Shotwell’s rivalry with Cracker Jack was actually a friendly one—with Alfred essentially collaborating with Louis Rueckheim and Harry Eckstein as much as competing against them.

“Alfred Henley Shotwell was a personable young man with a desire to make his mark on the world,” writes Fred Joyce, whose late wife Harriet interviewed Alfred “Shotty” Shotwell, Jr. (the founder’s son) and grandsons Charles Shotwell and Alfred “Chip” Shotwell III back in the 1980s. “He modeled his company after Rueckheim Bros. & Eckstein . . . and had a close association with them. There’s even an amusing story about how Mr. Shotwell and Louis Rueckheim each would pass out nickels to children [presumably on the same street corner], with Alfred telling them to go “buy Checkers!” and Louis telling them to “buy Cracker Jack!”

[Shotwell MFG Co. founder Alfred Shotwell, Sr., pictured in 1922]

Obviously, a lot of family-curated folklore is going to have a rose-colored tint to it, leaving plenty of room for skepticism. But I suppose it’s worth noting that the Cracker Jack Company did opt to keep producing and promoting Checkers for many years after acquiring the brand—rather than squashing it out of existence as a disreputable copycat. So maybe—patent lawsuits aside—there wasn’t too much bad blood there, after all.

II. Checkers: The ORIGINAL Prize Pop Corn Confection

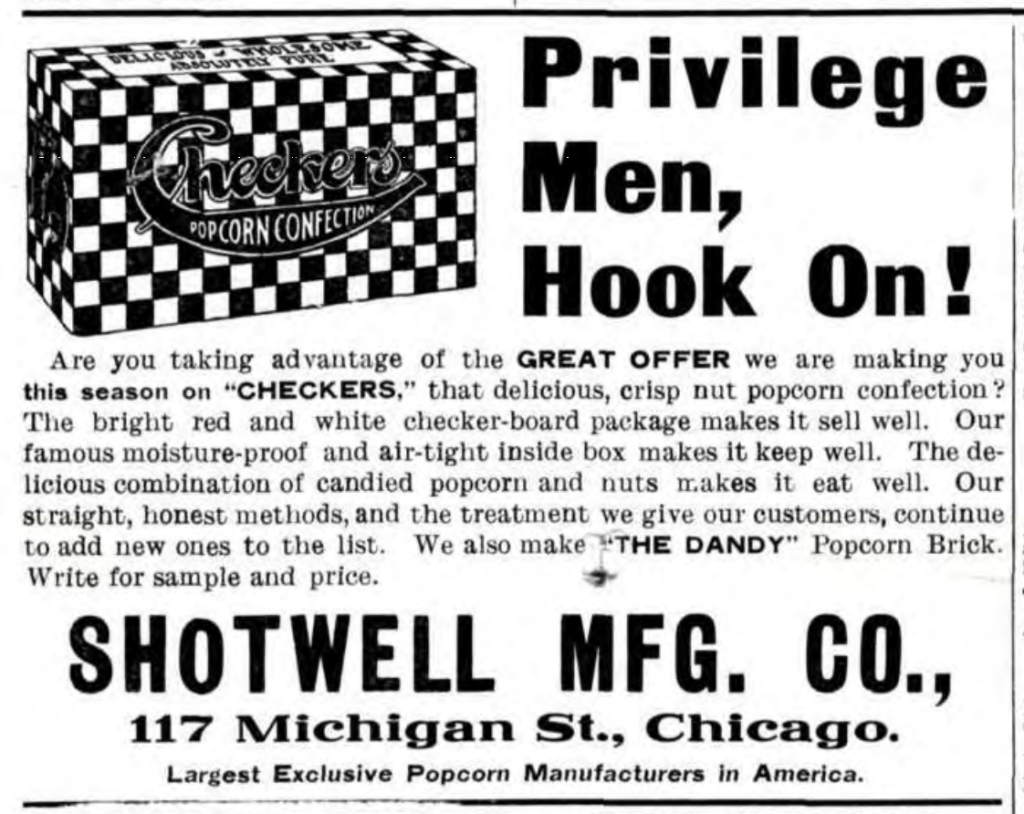

“Privilege Men, Hook On! Are you taking advantage of the GREAT OFFER we are making you this season on ‘CHECKERS,’ that delicious, crisp nut popcorn confection? The bright red and white checker-board package makes it sell well. Our famous moisture-proof and air-tight inside box makes it keep well. The delicious combination of candied popcorn and nuts makes it eat well. Our straight, honest methods, and the treatment we give our customers, continue to add new ones to the list.” —Shotwell MFG Co. advertisement, 1905

“Privilege Men, Hook On! Are you taking advantage of the GREAT OFFER we are making you this season on ‘CHECKERS,’ that delicious, crisp nut popcorn confection? The bright red and white checker-board package makes it sell well. Our famous moisture-proof and air-tight inside box makes it keep well. The delicious combination of candied popcorn and nuts makes it eat well. Our straight, honest methods, and the treatment we give our customers, continue to add new ones to the list.” —Shotwell MFG Co. advertisement, 1905

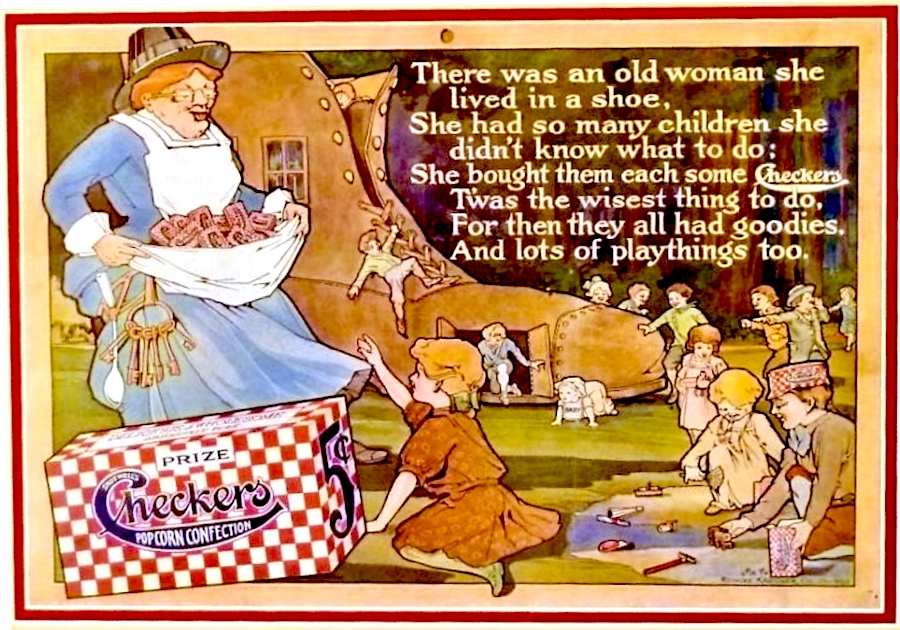

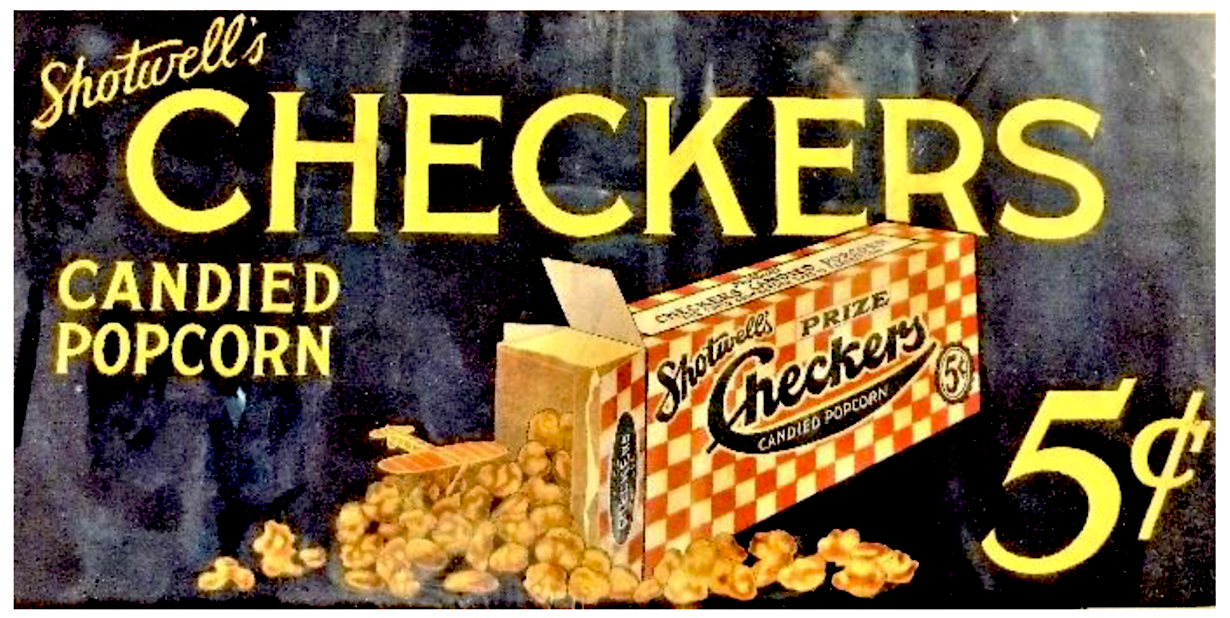

Upon its organization in 1903, the Shotwell Manufacturing Company was headquartered at 115-117 Michigan Street (what would now be about 146 W. Hubbard Street). Charles R. Hall was the secretary/treasurer (a position he would hold for 30 years), and a team of about 15 workers was on staff. To try and stand out from Cracker Jack, Alfred Shotwell packaged his flagship product in colorful red-and-white checkered boxes, which also included labels with questionable platitudes about Checkers’ supposed health benefits: “Delicious and Wholesome, Absolutely Pure.”

I suppose, from a modern perspective, Checkers might have been a bit more “wholesome” than our modern boxed candies. A complete description of how it was made—from an Iowa cornfield to the Chicago packaging plant—was provided during one of Shotwell’s (many) tax evasion cases in the 1920s, and conveniently describes all the ingredients therein; something that original packages of the snack were NOT required to do.

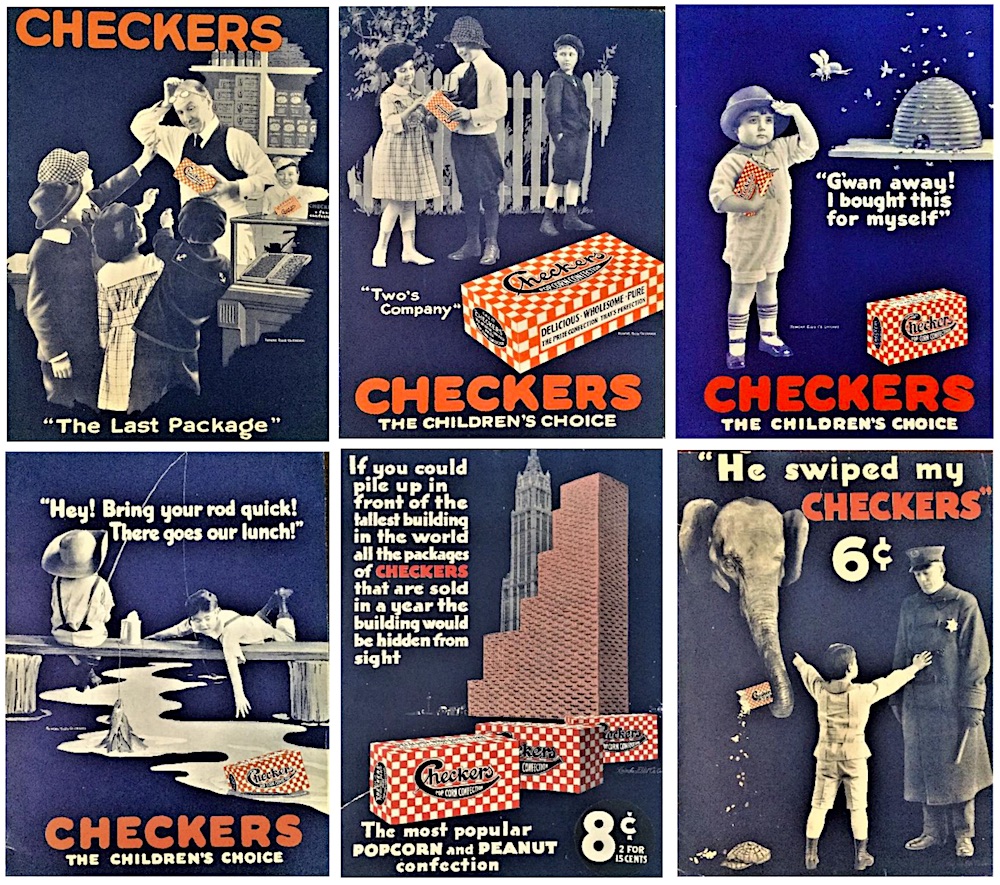

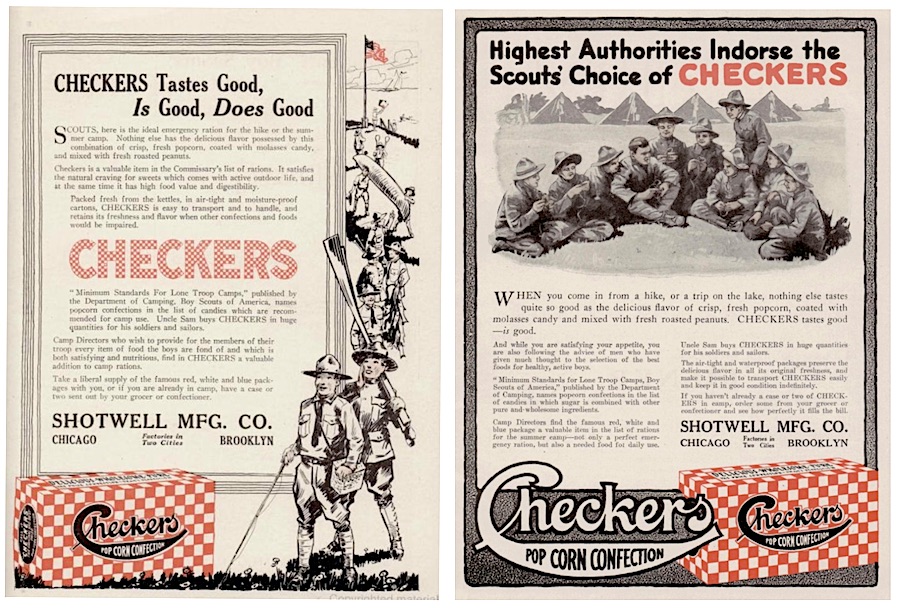

[Healthy or not, Checkers was marketed as “The Children’s Choice” in these ads from 1918-1919]

“The pop corn, after being gathered from the field, is cured, shelled, and screened. At the manufacturing plant the corn is conveyed to the popping ovens where it is pre-heated, popped, and again screened to remove the kernels which did not pop or which popped insufficiently to be salable. The popped corn is then conveyed to the mixing vats where a coating consisting of a syrup made of raw sugar, corn syrup, and molasses is poured on. The product is then cooled by rotation in an agitating machine. In Checkers the popped corn is then conveyed to the filling devices where it is mixed with a very small quantity of peanuts and then put into air and moisture tight packages. . . . By weight the finished Checkers were 38.43% pop corn, 6.15% peanuts, 17.08% sugar, 8.28% molasses, and 30.06% corn syrup.”

By 1907, as Americans were warming up to Checkers and its sister product, “The Dandy” popcorn brick, Shotwell’s Chicago team had increased to 84 workers, occupying a much larger facility at 407-411 N. Peoria Street. Just a few years later, it was on to an even bigger five-story plant at 1013-1021 W. Adams Street (a building that is still standing today after a full renovation in the 1990s).

[Left: Shotwell letterhead from 1913, showing the factory at 1013-1021 W. Adams Street. Right: The same building today, which still features the checkerboard exterior design from the Shotwell era, even though the company left the facility in 1922]

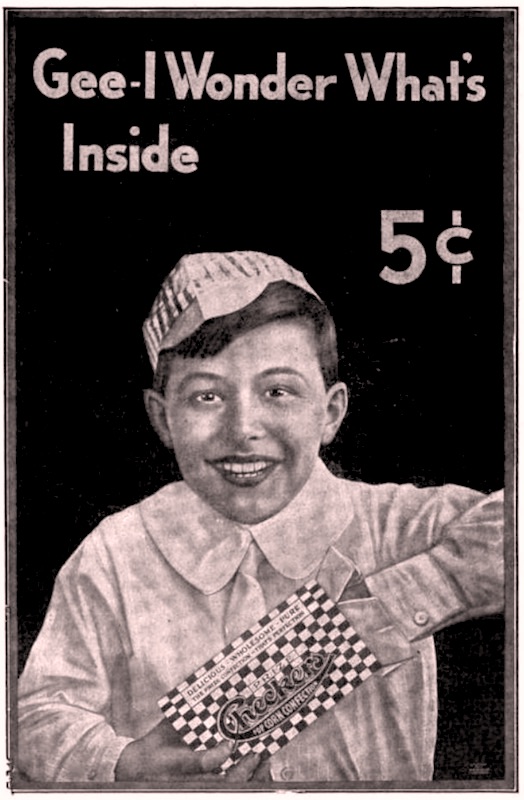

Part of Shotwell’s early, exponential growth may have been powered by a single, groundbreaking marketing choice—to start placing novelty mystery prizes in each package of Checkers. As early as 1909, newspaper ads were touting this gimmick (“every box contains a prize!”)—and soon the brand itself was rechristened “Souvenir Checkers,” and later “Prize Checkers,” to make the messaging as direct as possible.

In historical context, this type of sales tactic—the inclusion of a small prize or “premium” alongside a primary good—was nothing revolutionary; Wrigley gum, for example, had famously started out as a throw-in with William Wrigley’s line of soaps decades earlier. In the age of mass production, though, a lot of premiums would come in the form of a redeemable coupon—something you had to send back in the post or return to a local shop to exchange. The whole idea, after all, was to inspire repeat sales. Even early Cracker Jack prizes, which also started appearing around 1909, were of this rather dull type.

The supposed breakthrough with Checkers, then, was the decision to bury the prize—cheap and tiny though it may be—right there inside the box itself; cutting out the middleman and erasing the annoying lag time between snacking and “redemption.” Considering that Cracker Jack didn’t introduce its own famous novelty trinkets until 1912 (according to the Cracker Jack Collectors Association), it certainly opens the door to the idea that Shotwell really was “the ORIGINAL prize pop corn confection,” as it often claimed. Unfortunately, it’s also virtually impossible to confirm this with concrete evidence.

Surviving charms and trinkets from early Checkers boxes never have helpful copyright dates on them, and early advertisements, pre 1912, don’t make it clear if Checkers was offering physical prizes or the same sort of redeemable coupons that were common to the period. It’s only in 1912 that the advertising language becomes more specific, leaving the waters murky as to whether Checkers or Cracker Jack crossed the threshold first. [Strangely, in Fred and Harriet Joyce’s account of events, Alfred Shotwell actually asked his Cracker Jack buddy Harry Eckstein to help him “secure a shipment of trinkets for his first production runs,” which only confuses the timeline all the more.]

“Checkers costs but 5 cents,” read one Shotwell ad in 1912. “Each box contains an interesting souvenir—worth nearly 5 cents alone.”

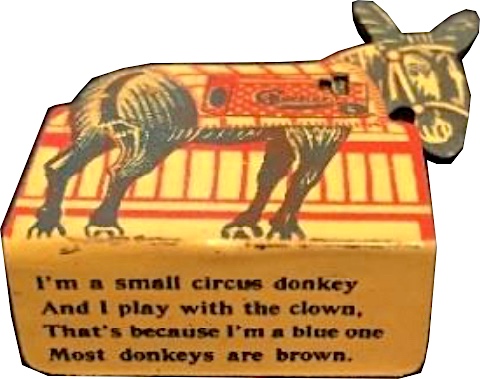

As for what constituted an “interesting souvenir” in 1912? Well, how about a tiny stand-up paper figurine with a terrible four-line poem written on it?

This puppy lives in Checkerstown

His name is Teddy Tox

And when he begs for Checkers

He always gets a box

There were also tin whistles, spinners, key chains, children’s costume jewelry, and “motion picture” slide cards. The various trinkets were sourced—as best we can tell—from a range of different suppliers. And while surviving examples aren’t collected with the passion of their Cracker Jack counterparts, diehard devotees will often say that Checkers actually had the superior doo-dads back in the day.

[Vintage Checkers prizes from the collection of Fred and Harriet Joyce]

III. Down on the Farm

Of course, pop corn, peanuts, and prizes weren’t the only blatantly obvious parallels between Checkers and Cracker Jack. Even the products’ geographical battlegrounds were increasingly overlapping. Besides the competing Chicago packaging plants, Shotwell and CJ also had major popcorn factories in western Iowa, and—by 1915—each had opened a satellite facility in Brooklyn, New York, elbowing one another for east coast distribution.

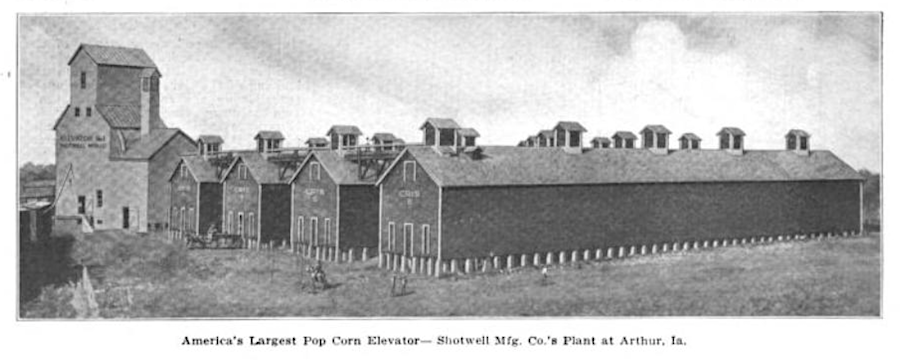

All clever marketing schemes aside, Alfred Shotwell knew that everything boiled down to the preponderance of the popcorn, so he poured a great deal of his resources into the Shotwell satellite plant in the tiny town of Arthur, Iowa; a little over 400 miles west of Chicago. Here, in 1913, he installed “what is said to be the largest and certainly the finest popcorn elevator in this country,” according to The Grain Dealers Journal. That 65 foot tall elevator could efficiently deliver new popcorn loads to any of the plant’s four storage cribs, each measuring 28’x28’ and 180 feet long, “with a total capacity of 2 million pounds of popcorn.”

“The Shotwell MFG Co. buys and cures popcorn solely for its own use. It contracts with the farmers to raise corn according to its specifications and in this way secures a uniform grade. The popcorn is cured for two years. During this time it must be frequently cleaned and aerated so that it dries uniformly. This elevator was designed in order that these operations can be carried on easily and economically.”

By the end of the 1910s, Shotwell, Cracker Jack and a company called D. L. Clark & Co. collectively “manufactured and sold 90% of the pop corn and pop corn confectionery” in America. There were 30 million packages of Checkers sold in 1919 alone, and Shotwell’s net annual earnings were up around $240,000, equivalent to $3.5 million after inflation.

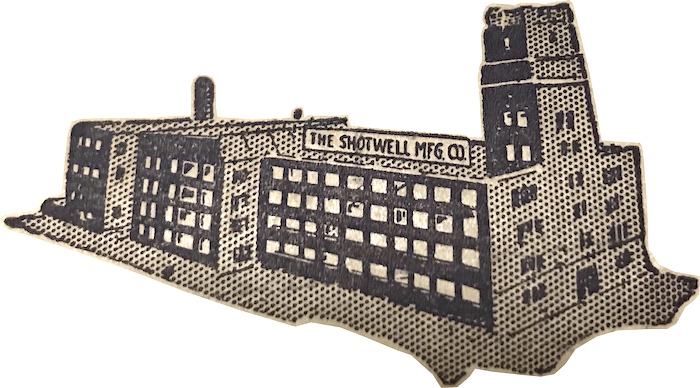

“The Shotwell Manufacturing Company, makers of popcorn confections, have undergone such rapid expansion,” Commerce magazine reported in 1920, “they have been forced to plan the construction of a new plant. They have acquired from D. A. Raggio 158,775 square feet on West Potomac Avenue, 500 feet west of Homan Avenue, at a cost of $1 per square foot. Plans are being prepared for the first unit of a large plant, which will be four and five stories in height, 80×192; and contain 88,000 square feet. A corn storage building, 40×60 ft., will also be erected separate from the main building.”

The new factory—complete with a checker pattern at the top of its central tower—was up and running by 1922, probably marking the pinnacle of Shotwell’s powers. And though he’d give up his Iowa plant and stop popping popcorn just a few years later, it’s possible that Alfred Shotwell saw a rosier future ahead in the form of a different product . . . the candy bar. These wildly popular, cheaper-to-make treats—combined with the untapped potential of America’s growing celebrity culture—would form the basis for a brand new Shotwell business model in the Roaring ’20s.

[The Shotwell factory at 3501 W. Potomac Avenue later became Zenith’s Plant No. 4 in the 1950s, but was ultimately torn down. The former site is now home to the Pablo Casals Elementary School.]

IV. The Galloping Ghost

After unashamedly piggy-backing off Cracker Jack’s pop corn formula back in the early 1900s, Shotwell headed into the 1920s laser focused on America’s candy bar craze. This was the era in which Chicago confectioners were rapidly producing soon-to-be iconic chocolate bars like the Oh Henry! (Williamson Candy, 1920), Baby Ruth (Curtiss Candy, 1921), and Milky Way (Mars, 1924), and Shotwell wanted desperately to get its own horse in the race.

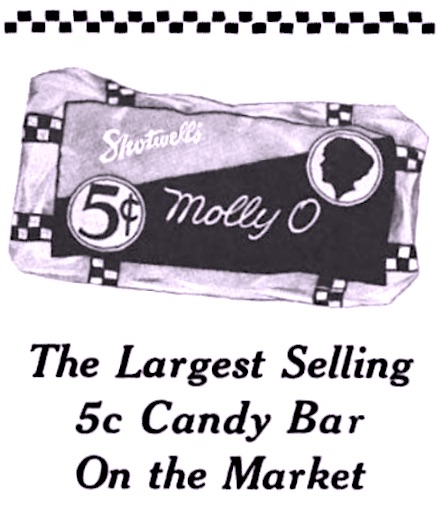

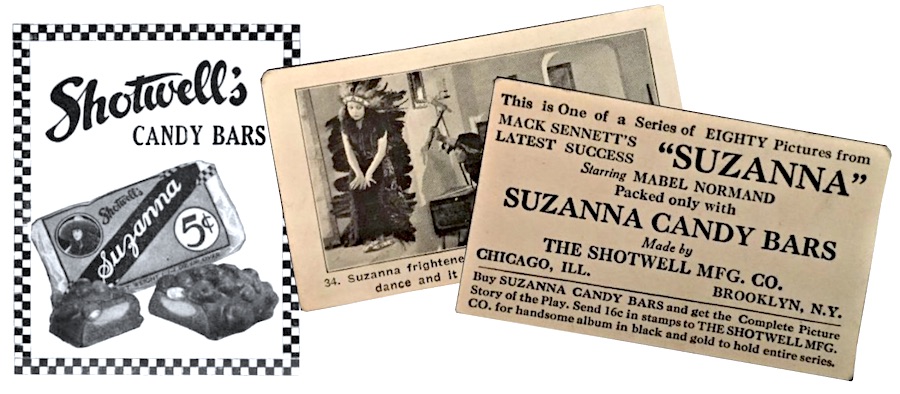

The company produced a broad line-up of “nickel bars” to match up with those names above, including the Car-Load featured in our collection, as well as the Winner, Handy Andy, Cherry Cream, Carmelita, and Roasty Toasty. For the kid with money to burn, there were also “dime bars” like the Love Dream, Tackle Me, Fluffy Duff, and Silver Dime. Shotwell’s biggest sellers, however, were the Molly O and the Suzanna; both of which were named after silent film comedies starring the popular actress Mabel Normand.

The company produced a broad line-up of “nickel bars” to match up with those names above, including the Car-Load featured in our collection, as well as the Winner, Handy Andy, Cherry Cream, Carmelita, and Roasty Toasty. For the kid with money to burn, there were also “dime bars” like the Love Dream, Tackle Me, Fluffy Duff, and Silver Dime. Shotwell’s biggest sellers, however, were the Molly O and the Suzanna; both of which were named after silent film comedies starring the popular actress Mabel Normand.

It’s not clear what type of financial deal Shotwell had reached with Normand or the films’ producer, Mack Sennett, but both candy bars were sold with collectable picture cards with stills from the movies, suggesting a clear, early example of a cross-promotional relationship between Hollywood and the candy biz. It was a successful venture, too, as the Molly O was even described in one 1923 ad as “the Largest Selling 5c Candy Bar on the Market.” Such commercial tie-ins were fleeting, though, and the Molly O—unlike its namesake—didn’t have legs.

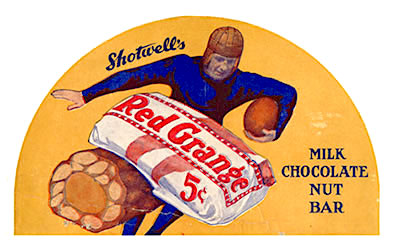

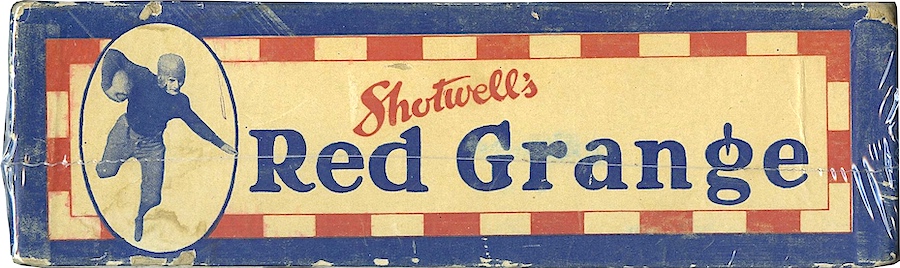

Several years later, while simultaneously negotiating the sale of his entire popcorn division to Cracker Jack, Alfred Shotwell made a similar but pricier maneuver, inking a deal with America’s biggest football star of the moment, Harold “Red” Grange, to produce a chocolate bar in his honor. This was, by some assessments, America’s first celebrity sponsored candy bar—although that is certainly up for debate. Famously, the baseball legend Babe Ruth never actually signed off on Curtiss Candy’s use of the name “Baby Ruth” in 1921, but he did launch his own competing bar—Ruth’s Home Run Candy Bar—in 1926 . . . the same year as Shotwell’s Red Grange Bar.

Grange, who’d become a star while playing for the University of Illinois, made his pro debut with the Chicago Bears in 1925, during the infancy of the National Football League. He was one of the first superstar athletes of the cinema age, and his appearances in newsreels and short films spread his celebrity from coast to coast. As a gridiron and matinee idol, Red stood out to Alfred Shotwell as the ideal human promotional vehicle, so he offered the 23 year-old $12,000 up front just for the rights to his image, with far more cash factored into the long-term deal.

Grange, who’d become a star while playing for the University of Illinois, made his pro debut with the Chicago Bears in 1925, during the infancy of the National Football League. He was one of the first superstar athletes of the cinema age, and his appearances in newsreels and short films spread his celebrity from coast to coast. As a gridiron and matinee idol, Red stood out to Alfred Shotwell as the ideal human promotional vehicle, so he offered the 23 year-old $12,000 up front just for the rights to his image, with far more cash factored into the long-term deal.

“It involved some royalties,” Alfred’s grandson Chip Shotwell later explained. “He was paid $62,000, which was a hell of a lot of money back then.” To be exact, that’s about a $900,000 payment with inflation factored in.

Before the ink was dry, the Shotwell factory on Potomac Avenue was cranking out Red Grange Bars faster than Red could find the endzone.

“Another Shotwell success,” read one ad in the candy trades, “a big two ounce maple caramel cream nougat center rolled in peanuts and chewy caramel with milk chocolate coating; lithographed glassine wrapper with individual picture of Red Grange; 24 bars in Red Grange display box.”

Of course, Shotwell incorporated prizes into this whole undertaking, as well, producing a set of 12 collectable cards featuring images of Grange—aka “the Galloping Ghost.” Kids were also encouraged to hold on to all their Red Grange Bar wrappers, as a certain number could be traded in for yet another coveted prize: a Red Grange football!

“Remember at this time there were candy stores everywhere,” Chip Shotwell noted in a recent Grange biography. “My grandfather had salesmen who would travel around to these stores and ask for some space to set up a display and so forth. The nicer the display was, the more eye-catching it was [for customers].”

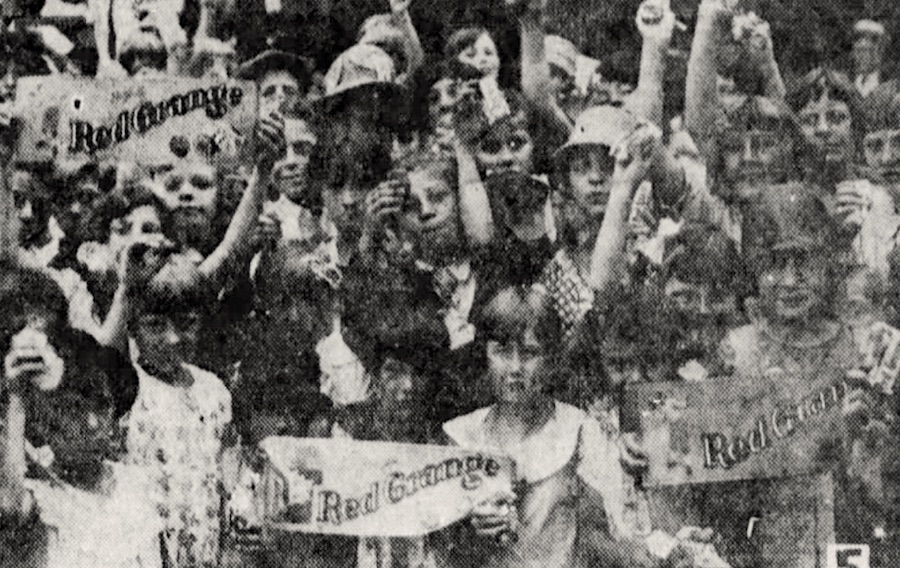

Aside from just setting up displays, Shotwell salesmen were also active in local events for their territories, handing out free candy bars and encouraging kids to “be like Red.” In Dayton, Ohio, for example, a sales associate named George “Scottie” Dunlop had the job . . . you can see some of his enthusiastic recruits below.

[Children showing off their Red Grange candy bar boxes at a promotional event in Dayton, Ohio, in 1926. The prizes were handed out by Shotwell’s resident Dayton representative, George Dunlop]

Anyway, like most athlete-sponsored candy bars of the subsequent century, the Grange Bar had a relatively short shelf life, as did Shotwell’s attempts at similar campaigns with candy bars named after famous (and now long forgotten) radio stars of the ‘20s, including the “Uncle Bob” and the “Sam n’ Henry.” According to Chip Shotwell, though, his family remained friendly with Red Grange long after their business affairs were over.

“Oh yeah, my grandfather would go to the games and take my dad [Alfred Shotwell, Jr.] with him. Red called my father ‘Shotsie.’ Dad always loved to visit and stop by to see Red (when he retired in Florida). He was the salt of the earth. The nicest guy you would ever meet. And very quiet about his history and his accomplishments; about how great he was. He didn’t do any bragging; he was very humble.”

It’s possible that Alfred Shotwell Sr. could have benefited from a little more Grange-like humility himself. While an admirable risk taker and aggressive marketer, his ambition sometimes came back to bite his business.

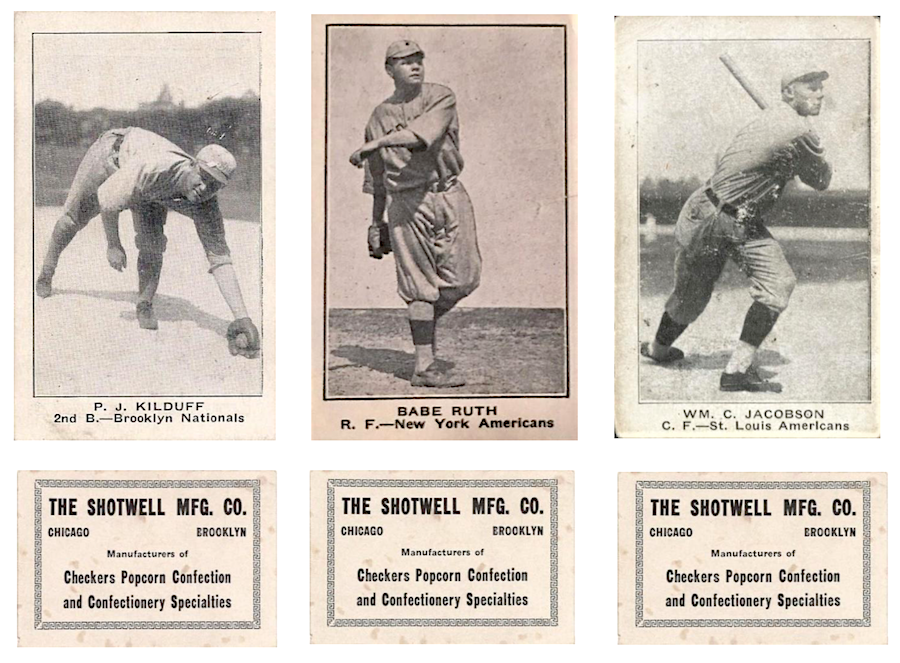

[Before finding its football star, Shotwell also briefly offered a set of baseball cards with boxes of Checkers in 1921, of which only a few are still known to exist. One of those, a Babe Ruth card, was supposedly purchased at a pawn shop in 2019 for $2, and could be worth multiple thousands . . . although collectors remain skeptical as to its authenticity.]

V. Legal Woes, or Shotwell That Ends Well

Alfred Shotwell’s lawyers, it seems, were often as busy as the workers in his factory. Along with the patent infringement lawsuits from Cracker Jack in the 1910s, Shotwell was back in court in 1921; hit with a cease-and-desist from the Federal Trade Commission for illegally bribing merchants with special gifts if they agreed to push Shotwell products above those of its competitors.

A few years later, the company came under investigation by the IRS for tax dodging; as Shotwell allegedly filed for large refunds by claiming that Checkers and their other pop corn products were NOT classifiable as “candy,” and thus didn’t have to comply with regulations established for that industry. The U.S. Court of Claims felt otherwise—although Checkers had already been sold off to Cracker Jack by the time the ruling came down.

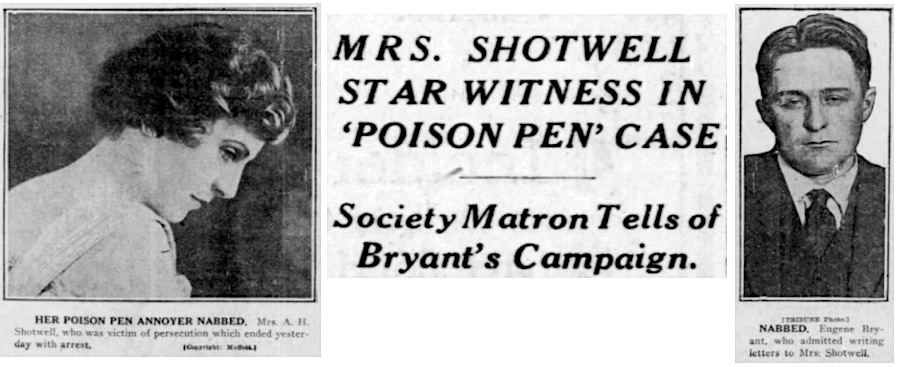

Shotwell’s most publicized and stressful court case of this period, however, had nothing to do with the family business at all. Across ten months spanning 1921 to 1922, Alfred’s wife Bess was terrorized by a mystery extortionist who sent her dozens of “poison pen” letters along with repeated threatening phone calls—many of which demanded cash payments to prevent acts of violence against the Shotwells and their 8 year-old son Alfred, Jr.

“I’m not alone,” one of the letters claimed. “You are dealing with a coast to coast blackmail gang that has operated for twenty years. The Chicago police have no worries over me. I see you and speak to you nearly every week. That’s how clever I am. Catch me? Ha. ha.”

When the perpetrator was finally arrested and identified as the elevator boy in the Shotwells’ building—Eugene Bryant—it became headline news across the country, with Bess’s court testimony generating particular interest in October of 1922.

“Courtroom hangers-on sat up and took notice to see charm and refinement in the witness’ chair where so many persons of a very different type have sat,” the Tribune reported. “The jury seemed sympathetic. Obviously it was interested. It cupped palm behind ear to catch Mrs. Shotwell’s murmured answers, as, visibly ill at ease, she listened to the crazy boastings, blasphemous threats, salacious insinuations, read in the monotonous legal voice of [her lawyer] Mr. Stewart.”

The accused, Eugene Bryant, plead insanity due to shellshock from his service in World War I. As the son of a respected judge (Wilbur Bryant of Nebraska), he got the benefit of the doubt and spent two years in a mental institution before getting his release.

Meanwhile, the Shotwell Manufacturing Company managed to stay largely scandal-free for a while, surviving the economic obstacles of the 1930s without any improprieties (or, at least, federal charges). When an aging Alfred Shotwell Sr. stepped away from the business during World War II, however, the incoming team of new executives quickly created a new mess of their own.

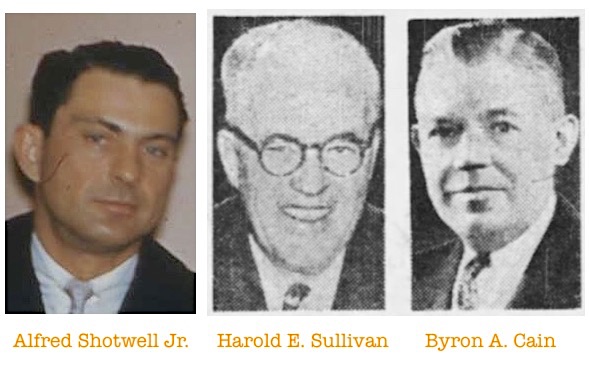

While Alfred Shotwell, Jr. (1914-2001) did work for the family business, he never took over the leadership from his father, and instead went on to purchase the Gaare Oil Company of Palatine, IL, in the 1940s. Since Junior was Alfred and Bess’s only son, this left no clear successor in line at the candy factory. Into that void stepped a Chicago real estate developer named Byron A. Cain, who became company president during the war, with Harold E. Sullivan installed as executive vice president and Frank J. Huebner as VP. All three of those men were later indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of defrauding the government from 1944 to 1946; lying about the firm’s income and selling its corn syrup and sugar on the black market.

While Alfred Shotwell, Jr. (1914-2001) did work for the family business, he never took over the leadership from his father, and instead went on to purchase the Gaare Oil Company of Palatine, IL, in the 1940s. Since Junior was Alfred and Bess’s only son, this left no clear successor in line at the candy factory. Into that void stepped a Chicago real estate developer named Byron A. Cain, who became company president during the war, with Harold E. Sullivan installed as executive vice president and Frank J. Huebner as VP. All three of those men were later indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of defrauding the government from 1944 to 1946; lying about the firm’s income and selling its corn syrup and sugar on the black market.

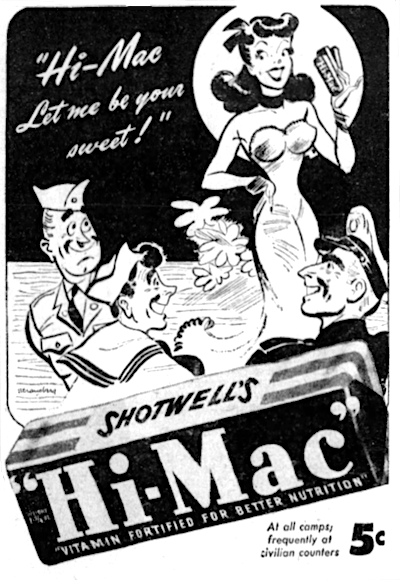

This was a particularly severe offense, considering the sneaky impetus for the crime was to avoid rationing restrictions created by World War II . . . at a time when Shotwell was advertising its Puritan Marshmallows and Hi-Mac, Shur-Mac, and Big Yank candy bars with patriotic fervor.

Neither Alfred Shotwell Senior nor Junior were directly involved in the business at that point, and neither were accused of any crimes. When the full story hit the papers in March of 1952, however, it marked a very sad end to an era. Alfred Sr. died just a month later, on April 20, 1952, and within another week—on April 25—the Shotwell Manufacturing Company was sold to the Chase Candy Co. of St. Louis, which moved all production to its own factory.

Sources:

“The Checkers Story” – Fred and Harriet Joyce

Red Grange: The Life and Legacy of the NFL’s First Superstar, by Chris Willis

“America’s Largest Pop Corn Elevator” – Grain Dealers Journal, July 10, 1913

“Federal Trade Commission vs. Shotwell MFG Co.” – 1920

“Federal Trade Commission Cases on Giving of Jobbers’ Premiums” – The Spice Mill, Feb 1921

“Letters Cause Police to Guard Shotwell Home” – Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1922

“Wife of Millionaire Receives Warning” – The Times (Munster, Indiana), May 26, 1922

“Mrs. Shotwell Star Witness in ‘Poison Pen’ Case” – Chicago Tribune, October 26, 1922

“Cracker Jack Adds to Holdings” – Odebolt Chronicle, Aug 19, 1926

“Over 400 Attend August Birthday Party at State” – Dayton Herald, Aug 26, 1926

“‘Red Grange the Newest Confection'” – The Tennessean (Nashville), Jan 17, 1926

“Shotwell MFG Co. vs. United States” – 1929

“Indict 3 Candy Firm Heads as Tax Evaders” – Chicago Tribune, March 15, 1952

“Chase Candy Buys Shotwell Company” – The Billboard, May 10, 1952

“Suit Provides Barrier to U.S. Sauber Probe” – Chicago Tribune, April 13, 1956

“Shotwell Tax Fix for $10,000 Bared by U.S.” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 10, 1957

“From Candy to the Oil Business” – Gaare Oil Co. advertisement, Arlington Heights Herald, June 30, 1966

I acquired a candy box full of buttons back in the 70s I still have this box and need to know if the box is worth anything it’s a Crafton candy box with a date on it of November 7th 1945

I have one of the picture cards packed with the Suzanna candy bars. Does it have any value as a collectible?