Museum Artifact: Standard Brewery “OaKay” Export Beer Bottle, c. 1910

Made By: The Standard Brewery, W . Roosevelt Rd. and S. Campbell Ave., Chicago, IL [Tri-Taylor]

It might seem like we’re currently living in the golden era of the regional micro-brewery, what with upwards of 3,000 “craft beer” producers now in operation in the U.S., and about 70 inside the Chicago city limits alone. The “brew-pub” phenomenon, where patrons are invited to drink at an establishment tied directly to the production source, also feels trendy and new. But, as you might expect when it comes to Chicago and its longstanding relationship with booze, most of these stones have all been turned over before.

The Standard Brewery, which operated out of an imposing plant in the Tri-Taylor neighborhood from 1892 to 1920, was just one of the many highly successful Chicago brew houses of its time—competing with the likes of Wacker & Birk (171 N. Des Plaines), McAvoy (24th St. and South Park), Schoenhofen (18th and Canalport Ave.), the Best Brewing Co. (1317 Fletcher Ave.), and a conglomerate of indie breweries known as the United States Brewing Companies—just to name a few.

The Fermentation of an Industry

Long before Chicago earned its reputation as a bootlegging capital, these (mostly) upstanding businesses were the prolific and profitable bloodlines to the city’s perfectly legal drinking establishments. Most of them, including Standard, not only sold their kegs to independent taverns and alehouses, but also signed exclusivity contracts with some saloon owners, creating “tied houses” where only the beers of the one sponsoring brewery would be served. It was a firmly established network of loyal producers, suppliers, and drinkers, all organically developed for more than half a century—then abruptly severed with the passing of the 18th amendment.

This isn’t to say that everything about those pre-Prohibition days was sunshine and rainbows. Chicago’s local breweries were banking huge profits, in no small degree, from the rampant alcoholism disproportionately impacting the city’s working class and immigrant populations. At the same time, though, both the brewing tradition and the tavern community were important cultural touchstones and points of pride for much of Chicago’s previously disenfranchised newcomers—particularly the Germans and the Irish.

This isn’t to say that everything about those pre-Prohibition days was sunshine and rainbows. Chicago’s local breweries were banking huge profits, in no small degree, from the rampant alcoholism disproportionately impacting the city’s working class and immigrant populations. At the same time, though, both the brewing tradition and the tavern community were important cultural touchstones and points of pride for much of Chicago’s previously disenfranchised newcomers—particularly the Germans and the Irish.

Back in 1855, these groups had been blatantly targeted by new city ordinances enacted by mayor Levi Boone (a great-nephew of Daniel Boone), decreeing that all taverns must be closed on Sundays and that the cost of a liquor license would rise from $50 to $300 annually, essentially forcing the shutdown of many prominent establishments. Immigrant groups responded by rioting downtown, leading to the death of a protester and 60 arrests. When Boone was voted out a year later, the ordinances went with him.

In the years that followed, as the immigrant population continued to grow, many well established brewers from the old country saw an opportunity to serve their old customers—and a potentially boundless new market—overseas.

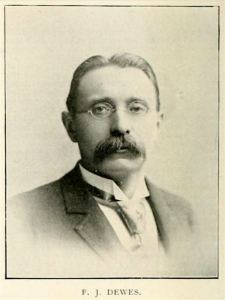

One of these men was Francis Joseph Dewes, future president of the Standard Brewery.

From Prussia With Love

Dewes was not the classic fresh-off-the-boat case. Born in Losheim, Germany (Prussia) in 1845, he’d trained under his father Peter, who was both a brewmaster and a member of the first German Parliament in Frankfurt. Young Francis then graduated from the Realschule in Cologne, and—by the age of 23—set sail for America, well armed with the skills and confidence he’d need to quickly move up the ranks of Chicago’s brewing elite.

Dewes was not the classic fresh-off-the-boat case. Born in Losheim, Germany (Prussia) in 1845, he’d trained under his father Peter, who was both a brewmaster and a member of the first German Parliament in Frankfurt. Young Francis then graduated from the Realschule in Cologne, and—by the age of 23—set sail for America, well armed with the skills and confidence he’d need to quickly move up the ranks of Chicago’s brewing elite.

He started as a bookkeeper for Rehm & Bartholomae in 1868, then became the secretary for the brewery of Michael Brand and Valentine Busch (of no known relation to Adolphus Busch, the soon-to-be beer magnate of St. Louis). Dewes helped Brand & Busch re-build their business after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, then stepped up again to assist Brand when Busch died a year later. In 1876, Dewes married a 19 year-old mädchen named Hedwig Busch—who doesn’t appear to have been related to either Valentine or Adolphus either. I guess people named Busch were just magnetically drawn to breweries during this period.

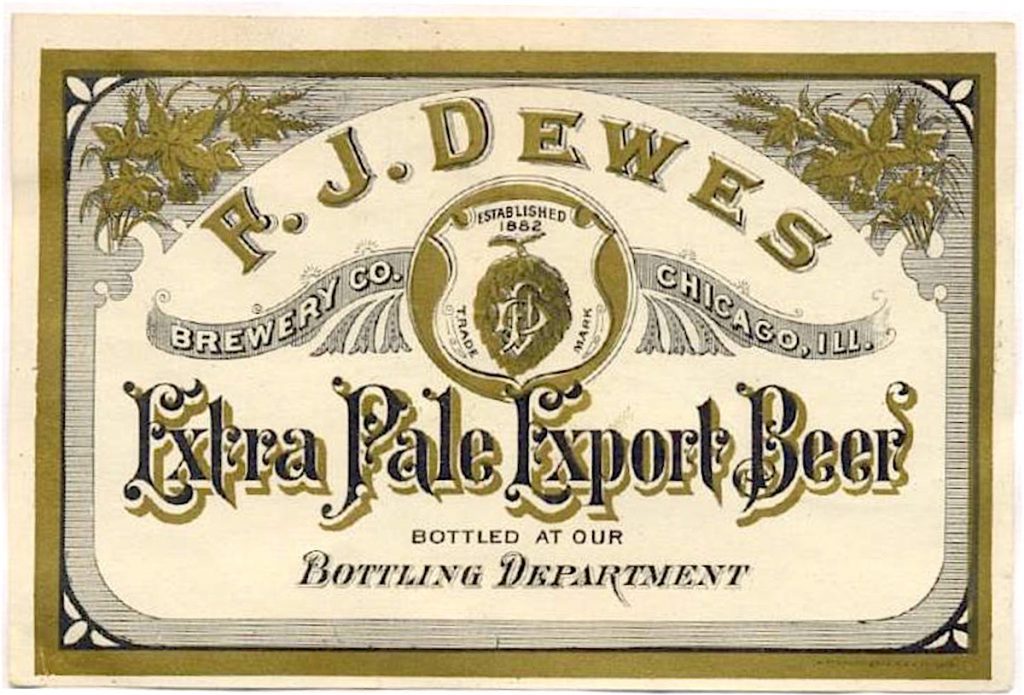

Anyway, after a decade with Brand Brewing, Francis Dewes was ready to launch his own operation, rolling out the new brews of the F. J. Dewes Brewery Company in 1881. The first headquarters was located at the corner of Hoyne Avenue and Rice Street in Ukrainian Village. That red brick building appears to have survived the past century+ as a rare reminder of Chicago’s first great beer epoch.

[The first F. J. Dewes Brewery Co. building at Hoyne and Rice Street]

[The first F. J. Dewes Brewery Co. building at Hoyne and Rice Street]

In short order, F. J. Dewes emerged as one of the preferred ale makers in the region, not just for the city’s German population, but beer drinkers of all tongues and skin tones. Dewes brought the finest brewing techniques of Germany and Denmark to the West Side of Chicago, and he made deals with saloon keepers across the city, setting up a solid fleet of tied houses. By the end of the 1880s, he was a bona fide millionaire.

“[F. J. Dewes Brewery Co.] has taken high rank, second to none of Chicago’s famous breweries,”read a company bio in the 1892 book, Chicago and Its Resources Twenty Years After, 1871-1891. “F. J. Dewes, the well known head of the house, had been long and favorably known to the trade. The popular device of the brewery is ‘Hoppen und Malz Gott erhalt’ (Hops and Malt may Gold preserve). The special brand of the Dewes Brewery, the ‘Muenchener’ beer, was introduced in 1889 as a beverage particularly adapted to domestic purposes. Following the example of the celebrated Jacobsen brewery of Copenhagen, Denmark, an establishment known the world over, the Dewes Brewery has first introduced to Chicago the method ‘Hansen’ to produce absolutely pure yeast. The output of this brewery this year will be 80,000 barrels, and in the very near future the capacity will be doubled, in order to meet the greatly increasing demands of the trade.”

Villa Dewes

The early 1890s was something of a banner period for Francis Dewes. With his exponentially increasing wealth, he began making some legacy-minded investments—most of them tied to his heritage. In 1892, he commissioned a large Felix Gorling sculpture of the great Prussian naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, which—appropriately enough—still sits in a prominent place in Humboldt Park.

Shortly thereafter, Dewes began working with architects Adolph Cudell and Arthur Hercz on plans for a new mansion to be constructed in Lincoln Park. The “Villa Dewes” at 503 West Wrightwood incorporated Baroque and French influences into an extremely lavish, highly ornamented celebration of World’s Fair era decadence—clearly unfazed by the severe economic recession happening concurrently.

Shortly thereafter, Dewes began working with architects Adolph Cudell and Arthur Hercz on plans for a new mansion to be constructed in Lincoln Park. The “Villa Dewes” at 503 West Wrightwood incorporated Baroque and French influences into an extremely lavish, highly ornamented celebration of World’s Fair era decadence—clearly unfazed by the severe economic recession happening concurrently.

Still standing today as a historic landmark, the “Francis J. Dewes House” is one of the city’s few private 19th century magnate mansions that’s been properly preserved or refurbished to its original glory—this following a series of random residents that included the Swedish Engineers Society (1920s-1960s), gay “Mr. Leather” icon Chuck Renslow (1970s), controversy-plagued city official Peter Schivarelli (1970s), and real estate developer Fred Latsko (2000s), who had his record of deception and forgery expunged by a prison-bound governor Rod Blagojevich in 2009. At last look, the completely restored house was on sale for a nice and tidy $12 million.

[2010 walking tour of the Dewes House produced by YoChicago]

Dewes was expanding his business’s real estate at the end of the century, too. He took over a major complex on North Avenue (319 West by present day street numbers), and also played a role in the foundation of a new side venture, The Standard Brewery—which opened its large plant at W. 12th Street and Campbell Avenue in 1892. Initially, another German brew veteran by the name of J.W. Niederpruem served as Standard’s president, with Francis Dewes’s much younger brother August leaving the Dewes Brewery to serve as secretary. The original Standard line-up also included a former city alderman named John Gaynor (politicians running breweries was a long Chicago tradition dating back to Michael Diversey) and an ex-foreman with Milwaukee’s Miller Brewing Co., August Keiffer.

“This is one of the youngest, but most enterprising brewing companies in Chicago,” Chicago and Its Resources said of the Standard Brewery. “In erecting its works it had the advantage of all the modern improvements which it was enabled to adopt without extensive changes in old appliances. . . . It has a capacity of 150,000 barrels of beer per annum. . . . In personnel, as well as in appliances, the Standard is thoroughly equipped for business and is destined to enjoy the large measure of success which it deserves.”

[The Standard Brewery in all its glory, circa 1908]

[The Standard Brewery in all its glory, circa 1908]

For more than five years, the F. J. Dewes Brewery Co. and the Standard Brewery Co. co-existed—disproving some histories that F. J. Dewes simply became Standard. In truth, it’s unclear how closely involved Francis Dewes was with Standard in its early years, outside of the connection with his brother. By 1898, however, the wheels were in motion for the two entities to converge.

OaKay Then!

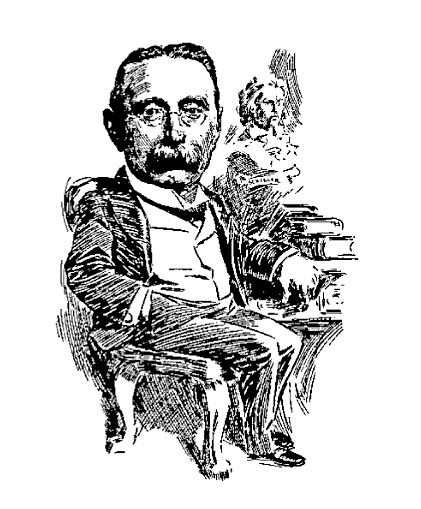

First, the F. J. Dewes Brewery Co. went through a rebranding process, officially becoming the “City Brewery Co.” in 1898. This was likely done in preparation for Dewes himself [pictured here in sketch form] leaving to take over the presidency at the Standard Brewery, which he did shortly thereafter, bumping his brother August to the VP position.

First, the F. J. Dewes Brewery Co. went through a rebranding process, officially becoming the “City Brewery Co.” in 1898. This was likely done in preparation for Dewes himself [pictured here in sketch form] leaving to take over the presidency at the Standard Brewery, which he did shortly thereafter, bumping his brother August to the VP position.

City Brewing and Standard Brewing carried on simultaneously for a brief time, as well, but by 1906, City had faded into obscurity, as a 60 year-old F. J. Dewes put his full focus into his new flagship. His decision to jump to Standard likely was inspired by the capabilities of the Campbell Avenue factory (sometimes also identified as 2500 W. Roosevelt Road). The brewery simply had more stills, more trucks, and more room for growth.

[A Standard Brewery deliver truck, circa 1915]

[A Standard Brewery deliver truck, circa 1915]

Aside from some violent worker strikes—an absolute norm at the turn of the century—Standard operated fairly smoothly and efficiently into the 1910s. Dewes did face a lawsuit in 1909 for using patent-infringing corks—but it didn’t exactly stir the pot. There were occasional movements to join larger syndicates, as well, with other Chicago brewers hoping to join forces to compete with the growing giants out of Milwaukee and St. Louis. But at his advancing age, Dewes now finally seemed content to enjoy the status quo. He had his mansion, his family, and the respect of the community. His son—a Harvard educated lawyer named Edwin—also joined the company as a secretary, seemingly putting the firm in good hands for years to come.

It was during this time that the artifact in our collection, a glass bottle of “OaKay Export,” was enjoyed by some thirsty lad or lass.

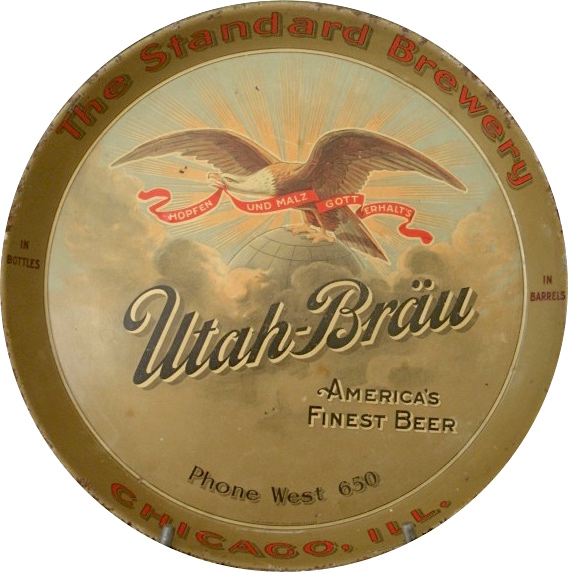

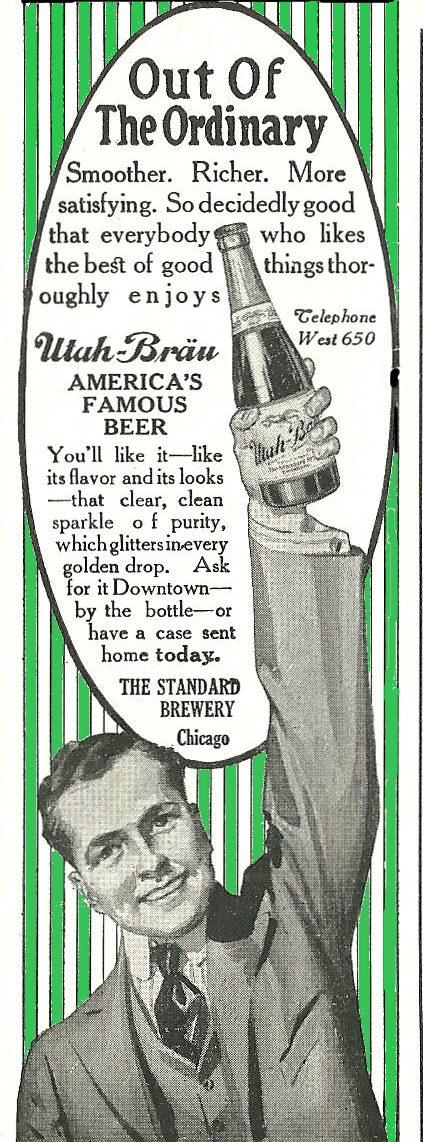

OaKay was a malt extract and something of a secondary product for Standard at the time, though it was notably promoted as being “specially brewed for family use”— whatever that means. Most of Standard’s heavy marketing at the time was going into its “UTAH-BRAU”—a mix of Utah barley and Bohemian hops that was alternately known as “America’s Finest Beer” and “America’s Famous Beer.” It’s hard to say that it was really either one. But I reckon we’ll never know for sure.

In any case, the debate was left moot by 1920, as the great experiment known as Prohibition began. Like many breweries of the day, Standard tried to stay in business brewing non-alcoholic “near beer” for a short time, but with real booze now turning into a black market game, the old distribution chains were as dry as the laws.

In any case, the debate was left moot by 1920, as the great experiment known as Prohibition began. Like many breweries of the day, Standard tried to stay in business brewing non-alcoholic “near beer” for a short time, but with real booze now turning into a black market game, the old distribution chains were as dry as the laws.

This was a bit of a sad closing chapter for Francis Dewes, who died in 1922 at the age of 78. He didn’t exactly lose his fortune, but his legacy was at least left in serious question at the end. His son Edwin left the brewery to work as a stockbroker, and brother August Dewes had reached retirement age himself. The Standard Brewery had reached its end . . . in a matter of speaking.

And Finally, the Gangster Era

Somewhere between the death of Francis Dewes and the official closure of the Standard Brewery, the company’s sprawling complex at 12th and Campbell fell into the hands of a rather famous pair of new “investors.”

More precisely—either by sale or underhanded acquisition—the brewery was now the exclusive property of the Irish mob’s famed “beer barons,” Terry Druggan and Frank Lake. Veterans of the infamous “Valley Gang,” Druggan and Lake were high-society millionaire bootleggers, overseeing a syndicate that eventually aligned with the operations of Al Capone.

[Left: Famed Irish-American gangsters Terry Druggan and Frank Lake, dapper gents by day, ran the Standard Brewery during the early Prohibition years. Right: Deputy U.S. marshals John J. Oros, John B. Showalter, and John F. Emery raid the gangsterized Standard Brewery in 1924]

[Left: Famed Irish-American gangsters Terry Druggan and Frank Lake, dapper gents by day, ran the Standard Brewery during the early Prohibition years. Right: Deputy U.S. marshals John J. Oros, John B. Showalter, and John F. Emery raid the gangsterized Standard Brewery in 1924]

Druggan and Lake’s control of the Standard Brewery was arguably their most tenuous. A raid on the facility in 1924 led to a high profile trial for both men and a one year prison sentence. Acting as their own attorneys in that case, both gangsters claimed that they’d merely been selling harmless and perfectly legal near-beer from the Standard plant, and that crooked cops had actually swapped the product out with real booze as a wicked frame-up. The judge didn’t buy it. Even so, Druggan and Lake’s boundless connections in the police department and city government enabled them to regularly walk out of prison for business meetings or light entertainment—the perks almost made it a pleasant stay.

Once the freed men joined up with Capone’s outfit, they seem to have gone right back to utilizing the Standard Brewery’s equipment. After getting hit for tax evasion in the late ‘20s, however, Druggan finally had the property seized. From there, the once thriving plant fell into total disrepair.

Once the freed men joined up with Capone’s outfit, they seem to have gone right back to utilizing the Standard Brewery’s equipment. After getting hit for tax evasion in the late ‘20s, however, Druggan finally had the property seized. From there, the once thriving plant fell into total disrepair.

“Nobody seems to own the old Standard Brewery out on Roosevelt Road,” read the first line of a 1930 article in the Prescott Evening Courier. “Four boys arrested for stealing copper piping from the brewery were in court yesterday and the state appeared to have a pretty good case except for the fact that it couldn’t prove the piping belonged to anyone before the boys had it. . . . The brewery used to belong to Terry Druggan, beer baron and racketeer, but Druggan said the government took it from him for defaulting in his income tax payments. Federal officials said they had not obtained complete title. . . . The boys were freed.”

Two years later, with the Depression taking its toll, the Tribune reported that the old Standard Brewery “had been looted by residents in the neighborhood until it is now only a brick shell.”

“The government has been attempting to dispose of the brewery, and put it up for sale some time ago,” the story continued, “but the bids were so low that the government itself bid it in and kept it. The problem of disposal has now been solved, for the structure is practically worthless in its present condition, it was said.”

With the business, the brand, and the brewery all gone, F. J. Dewes’ once beloved beer empire appeared doomed to be forgotten entirely. As recently as 2015, though, a different architectural relic had the Standard Brewery suddenly back in the news.

[The former Standard Brewery tied house at 3801 W. Grand Ave., before its demolition in 2015]

[The former Standard Brewery tied house at 3801 W. Grand Ave., before its demolition in 2015]

A beautiful deco building at 3801 W. Grand Ave.—the only known remaining Standard Brewery tied house—was under threat of demolition. Preservationists jumped in to try and prevent the teardown of the building, which still featured the eagle emblem of the Standard Brewery carved in stone. In the end, it was a half-victory. The building was still demolished, but many of the historic elements were removed and preserved.

So, while we can’t take a tour of the Standard Brewery plant or try its latest libations in a cool brew-pub (with over-priced brand merchandise), the legacy of this original Chicago micro-brew still lives on—in old collector bottles like this one, and in the city’s fully revived and thriving brewery culture.

[This former Dewes Brewery building at 319 W. North Avenue still bears the name of its founder more than 125 years later]

[This former Dewes Brewery building at 319 W. North Avenue still bears the name of its founder more than 125 years later]

Sources:

Chicago and Its Resources Twenty Years After, 1871-1891: A Commercial History Showing the Progress and Growth of Two Decades from the Great Fire to the Present Time (pub. 1892)

The Book of Chicagoans: A Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men and Women of the City of Chicago, 1917

Francis J. Dewes House – Historic American Buildings Survey

“Demolition Imminent for Former Standard Brewery Tied House” by ChicagoPatterns.com

“Druggan, Lake to Learn Fate Today in Court,” Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1924

“Dimiss Charges Against Three in Giant Still Case,” Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1932

“Nobody Claims Old Chicago Brewery,” Prescott Evening Courier, May 25, 1930

“$9.9 Million Pays Your Dewes, Lets You Get Your Gründerzeit On” from ArcChicago.blogspot.com

I have a standard brewery bottle that I found, while scuba diving in Fallen Leaf Lake, Lake Tahoe area, Ca. It is aqua/green color, embossed with the eagle, also says this bottle not to be sold. Do you have an idea how old it may be? Thanks

The Deputy US Marshall pictured in the article is my grandfather and his name was John J. Oros, not John L. Oros.

I have many articles and pictures of his activities in the day, draining beer into the river and serving subpoena’s to high society on the Gold Coast in his dress suit and bullet proof vest.

I enjoyed the article.

Just found glass bottle Chicago standard brewery while working on underground piping. In north of town.

It’s nice to see all the old Chicago history preserved here! My name is Charles Grommes La Roche, Louise Grommes Rehm was my grandmother, Frank A. Rehm being my great grandfather. My great aunt Frieda Grommes was married Armin W. Brand in October of 1905, so you see this story and the Chicago beer and whiskey trade are in my blood! Hubert Grommes, my great great uncle, and John Baptiste Grommes, my great great grandfather, of Shoenberg Prussia, emigrated to Chicago in 1850 and founded Grommes & Ullrich in 1860. Thanks for writing and posting all this, the old history should be preserved and not forgotten in my opinion. Charles Grommes La Roche in santa Barbara, California

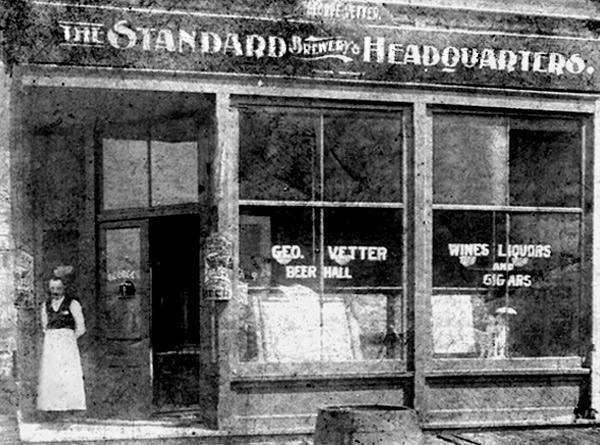

One of the photos features George Vetter Brew Hall. He is my wife’s Great, Great Grandfather. He moved to California in the Fall 1907 after his stores in Chicago closed and went bankrupt. He died in Feb 1913.

I have a beer bottle with the standard brewery Chicago on it-