Museum Artifacts: Stenograph Reporter Model (c. 1947) and LaSalle Stenotype Master Model Four (c. 1935)

Made By: Stenographic Machines, Inc., 80 E. Jackson Blvd. [Downtown / The Loop]

“The Stenograph was the best machine ever made. It would work with or without oil. Every bearing was like a jewel.” —Robert T. Wright (1906-2000)

Now I will admit from the outset, Robert Wright’s opinion of the Stenograph might not be entirely unbiased, considering he owned six patents related to the machine’s invention and spent roughly 50 years presiding over the company that produced it. Even so, the objective proof is in the proverbial pudding.

Nearly 80 years after the first Stenograph Shorthand Machine entered the lives of America’s secretaries and court reporters, the brand has become a proprietary eponym within the culture, a la Kleenex or Band-Aids. The Stenograph company itself (Stenograph LLC, now based in Elmhurst, IL) has also long-since smoked its would-be competitors, owning 90% of the marketplace.

Nearly 80 years after the first Stenograph Shorthand Machine entered the lives of America’s secretaries and court reporters, the brand has become a proprietary eponym within the culture, a la Kleenex or Band-Aids. The Stenograph company itself (Stenograph LLC, now based in Elmhurst, IL) has also long-since smoked its would-be competitors, owning 90% of the marketplace.

If you’re wondering, yes, stenography is still big business in the 21st century, and while the tool of the trade has evolved with electric motors and paperless readouts, the basic principles of this groundbreaking dictation tool have mostly held true.

“A person today would still be able to write on an old manual machine [like the one in the Made In Chicago Museum], because the keyboard has not changed,” explains Frank Chvojcsek, a Stenograph employee since 1964 and the company’s current Director of Mechanical Engineering. “The tension or force required to push the keys down was much greater back then, and the depth of stroke was longer than current writers, so a reporter today might get tired a lot quicker using the old models. But the Ireland Keyboard design, the key levers, the feel of the board—they have been part of every machine since the 1940s.”

The Stenograph in our own collection is an early Reporter model, circa 1947—a slightly tweaked version of the prototype Stenograph Shorthand Machine that debuted in 1939. The device was the co-invention of a former correspondence school president named Milton H. Wright, his son (the aforementioned) Robert T. Wright, and engineer John G. Sterling. From the beginning, it served as the flagship product for the young Chicago company known as Stenographic Machines, Inc.—even though its manufacture was credited to another local business, The Hedman Company.

The Reporter model—which differs from the standard Secretarial model only in that it includes a deeper die-cast tray for holding more paper (300 fold vs. 100 fold)—has a lightweight magnesium “crinkle black” shell, with an 11-inch self-inking ribbon and a “positive clutch” mechanism for silent operation. A customized carrying case was sold with it for easy transport.

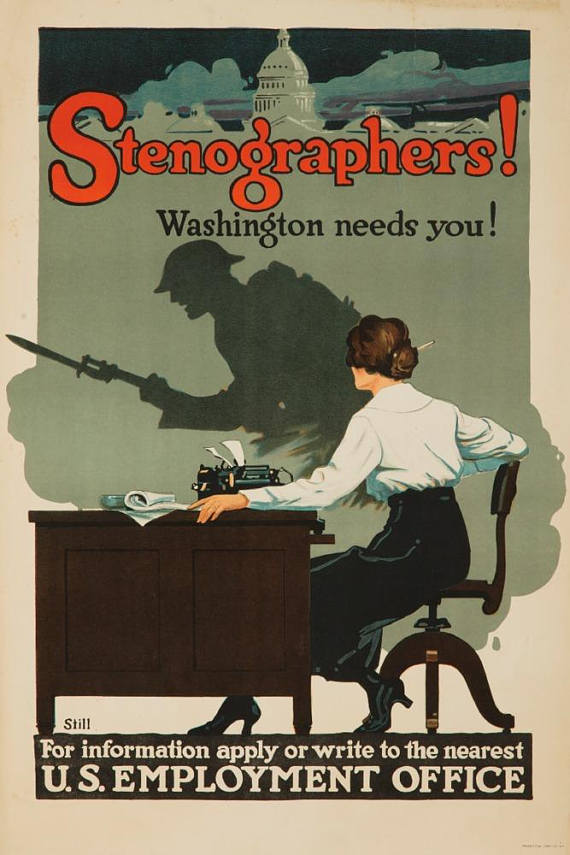

Dependable, portable and fast, the Stenograph found its audience just as the Second World War demanded a leap forward in precision dictation. For all its innovations, though, it was still very much part of a long lineage, borrowing and fine-tuning design elements—not to mention an entire sub-language—from the shorthand machines that had come before it.

Pre-History

The word “Stenograph” was actually coined long before Milton and Robert Wright came along. The first shorthand typing machine widely sold in the U.S. was invented by an Illinois court reporter named Miles Bartholomew in the late 1870s, just a few years after the debut of the QWERTY typewriter. His company, the United States Stenograph Corporation, made its cumbersome 10-key machines in East St. Louis, Illinois, with marginal commercial success.

Plenty of inventors saw the need for a better equipped turbo shorthand machine, but a truly practical, fully operational design didn’t come along for another 30 years, when another court reporter named Ward Stone Ireland patented his “Stenotype” machine in 1911.

Beyond pulling off a simple engineering feat (the 22-key machine was a reasonable 11.5 LBS and introduced a fully depressible keyboard), Ireland had pushed forward the entire field of shorthand communication, giving reporters the ability to type whole words phonetically with a quick stroke. Overnight, there was a new gold standard.

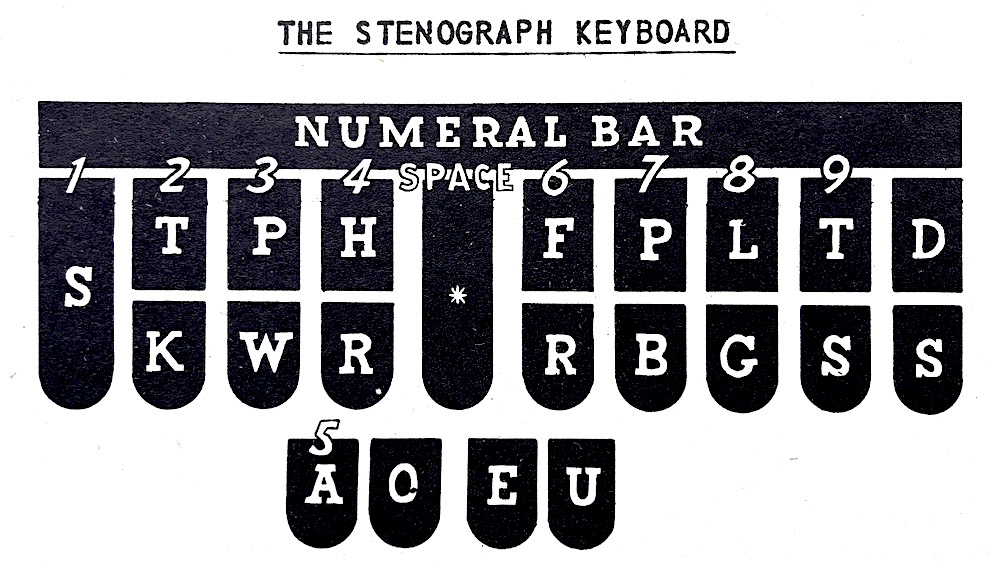

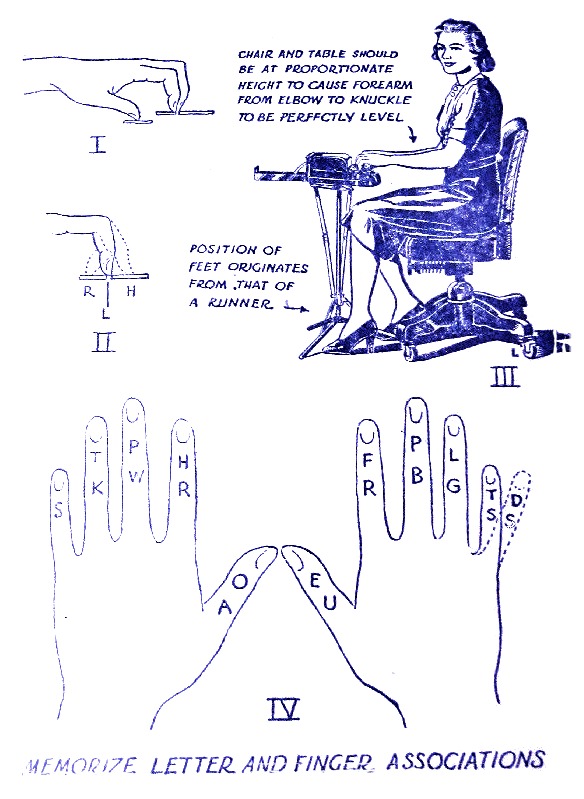

Basically, Ireland divided his keyboard into three sections. The left side keys represent initial consonant sounds, the right side represents ending consonant sounds, and four bottom keys (operated by the thumbs) create your vowels.

“The genius of the Ireland keyboard—the simplicity of it is fantastic,” Robert Wright later said. “Every sound is in the position it is on the keyboard because of the frequency with which it occurs in the language, and, secondly, the sequence in which it occurs. You have two total phonetic systems under each hand.”

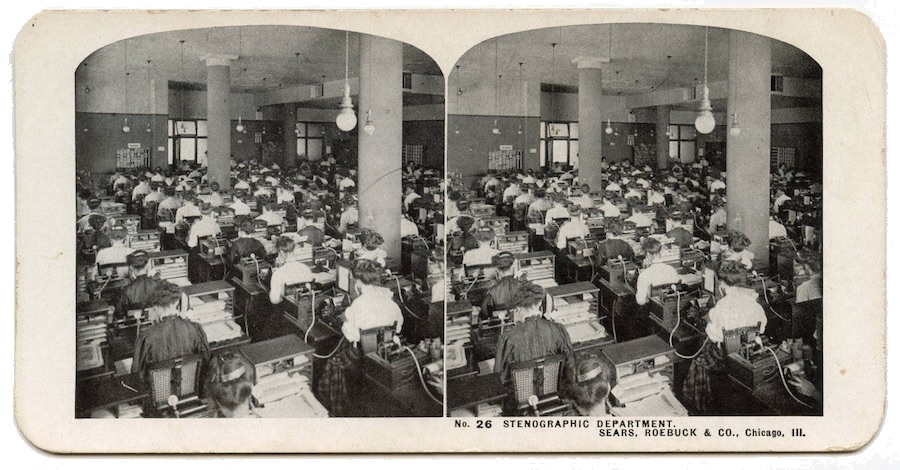

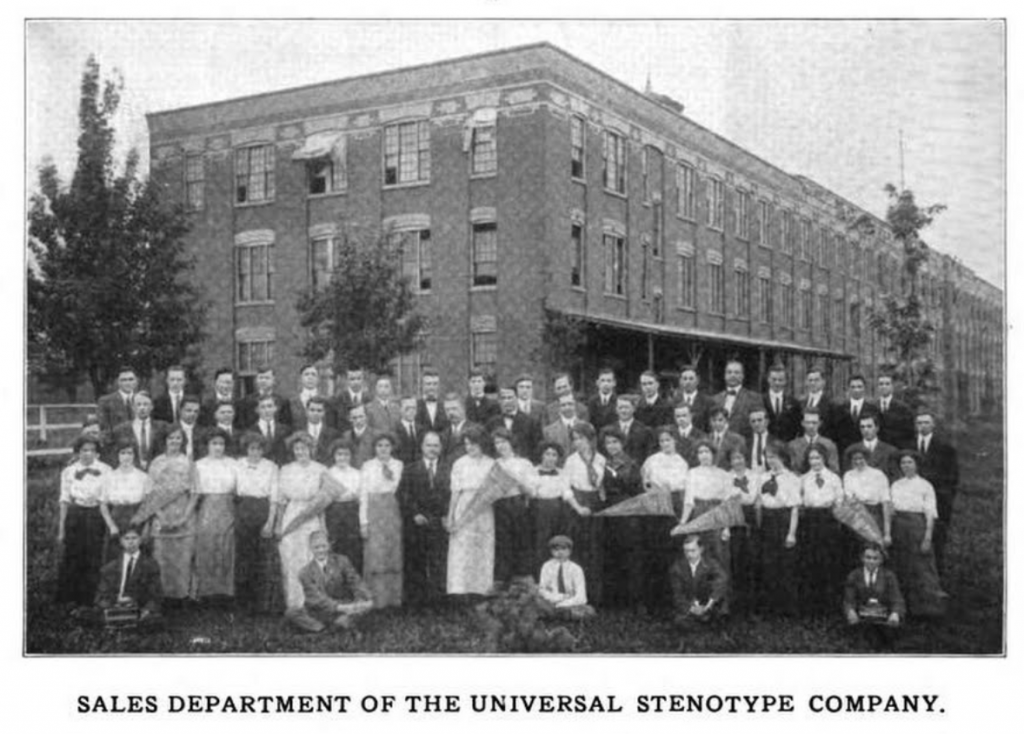

If this all sounds a bit confusing, well, people 100 years ago thought so, too. That’s why special seminars and training courses were developed to help users not only get a knack for the Stenotype machine itself, but the Stenotype “theory.” As legions of students were converted to professionals, the machine—manufactured by Ireland’s Universal Stenotype Company in Owensboro, Kentucky—became a sensation; proving more accurate in many cases than pen-and-pad note takers.

[An overview of the Stenograph keyboard, taken here from the first Stenograph Hand Book in 1940, uses Ward Stone Ireland’s 1911 design, largely unchanged]

[An overview of the Stenograph keyboard, taken here from the first Stenograph Hand Book in 1940, uses Ward Stone Ireland’s 1911 design, largely unchanged]

“Considering that the Stenotype has been on the market but a short time, the growth of this company is nothing short of marvelous,” the Shorthand and Typewriter News reported in 1913. “Growing as it has from a small workshop to an immense organization employing hundreds of skilled mechanics in less than two years is convincing proof of the merits of the Stenotype.

“A year ago this machine was practically unknown and the profession of Stenotypy was in its infancy. Today, Stenotypes are used in recording dictation in thousands of the country’s most progressive business offices, and nearly three hundred of the leading business colleges of the United States teach Stenotypy as a part of their curriculum.”

By anyone’s estimation, Ward Stone Ireland was headed for great wealth and reverence in the decades to come. The luck of the Irish, however, was not with him.

Just as his business was hitting its stride, Ireland was forced to switch over much of his factory production to government munitions work after the U.S. entered World War I. The transition went fine during the war itself, but after peace was declared, the Universal Stenotype Company went into a freefall. As it did with many other manufacturers, the U.S. government simply abandoned its contracts with Ireland, leaving him with a stockpile of munitions and nowhere to sell them. His company soon went bankrupt, and Ireland himself struggled to find his footing again.

In his later years, reduced to work as a small time shipping clerk in New Jersey during the Depression, Ireland was offered a job by one of his greatest admirers, Milton Wright of the upstart Stenographic Machines, Inc.

“My father tried very hard to employ [Ireland] after the company was formed,” Robert Wright later recalled, “ but he was so bitter about what had happened to his machine that he would not come to work for my father at all. He died not a pauper but almost, and we helped see to it that he was properly buried.”

In 1940, when Stenographic Machines, Inc. published its first user handbook, the introduction made a point of noting that “Mr. Ireland’s remarkable keyboard has endured without a peer and without fundamental change . . . That fact in itself constitutes matchless tribute to his originality and inventive genius.”

As Frank Chvojcsek mentioned, even now—after more than 100 years—that basic Ward Stone Ireland keyboard is STILL the industry standard.

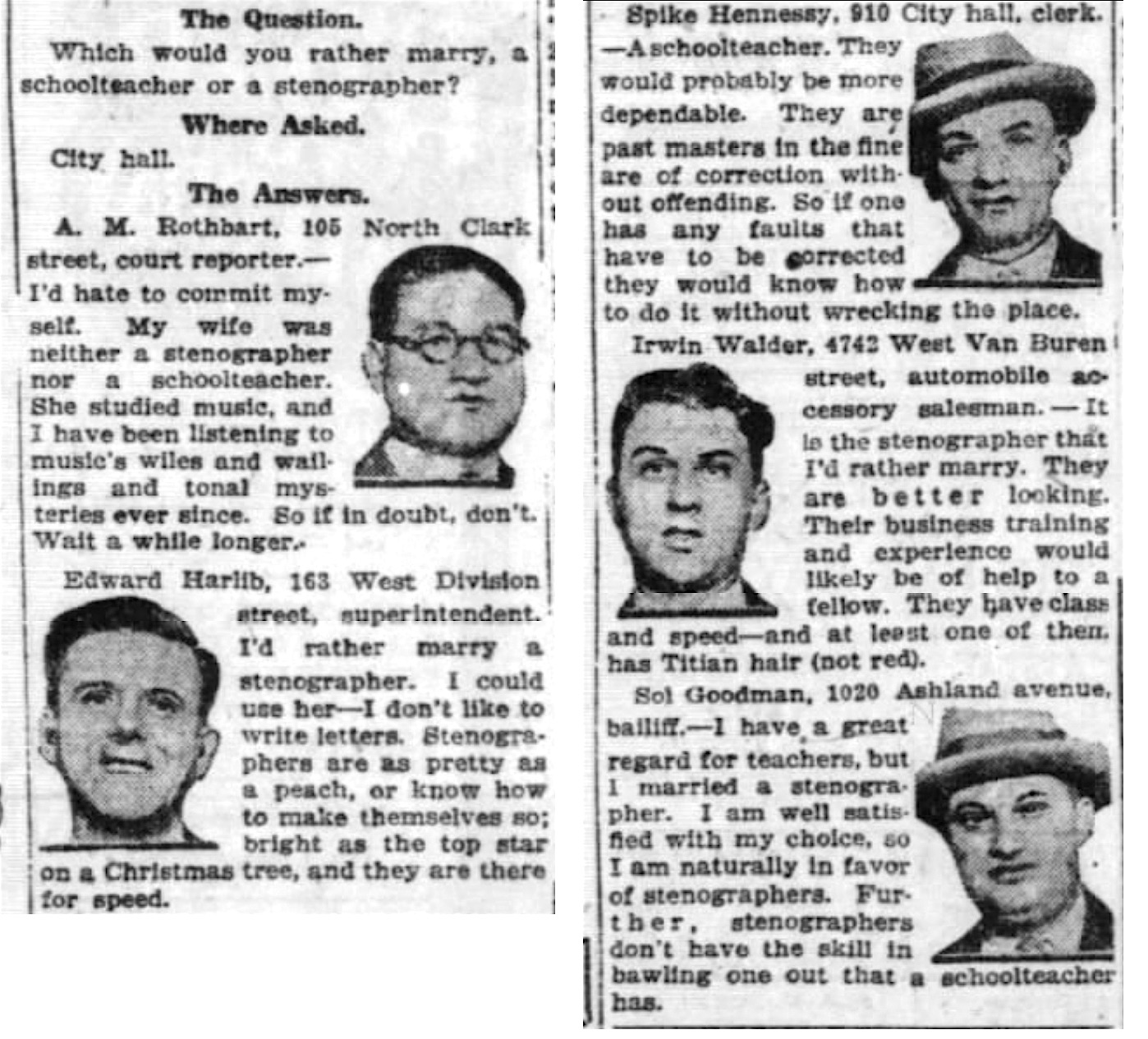

[On December 24, 1925, the Chicago Tribune’s “Inquiring Reporter” asked five random men outside City Hall whether they’d “rather marry a school teacher or a stenographer,” implying that these were, by now, perhaps the two most common professions for women in Chicago. The question was sent in to the paper, incidentally, by a Miss Florence Barros of Park Ridge. The responses are . . . interesting.]

[On December 24, 1925, the Chicago Tribune’s “Inquiring Reporter” asked five random men outside City Hall whether they’d “rather marry a school teacher or a stenographer,” implying that these were, by now, perhaps the two most common professions for women in Chicago. The question was sent in to the paper, incidentally, by a Miss Florence Barros of Park Ridge. The responses are . . . interesting.]

The Wrights Buy the Rights

In an un-dated interview (likely from the 1980s) acquired from the archives of the Stenograph company, an elderly Robert T. Wright discusses the history of his business with Richard Mowers of the National Court Reporters Association. Within the chat, he details how Ward Stone Ireland’s demise actually planted the seeds for the Stenograph’s birth.

“My father [Milton Wright] was vice-president of LaSalle Extension University [a Chicago correspondence school] in the 1920s. A lady reporter—one of Ward Stone Ireland’s students—happened to be in Chicago, and somehow or other she demonstrated to my father the consequences of writing on an Ireland Shorthand Machine. This was a pretty big machine in those days, but he was impressed.”

By 1927, Milton Wright had persuaded the officers and board of directors at LaSalle to acquire the assets of the long bankrupt Universal Stenotype Company, including the rights to the Stenotype machine itself, which could be built anew by an third-party manufacturer.

According to later court records, “from 1928 to 1936, LaSalle sold the Stenotype machine largely to students taking courses in Stenotypy by the correspondence or home study method, and to a lesser extent to business schools. Starting in 1936 LaSalle began to sell its machine to students enrolled in schools known as ‘Stenotype Institutions,’ which LaSalle assisted in organizing.” —Stenographic Machines, Inc. v. Federal Trade Commission, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, 1956

[The Stenotype “Master Model Four” pictured above is also part of our museum collection. Dating from the 1930s in the early days of the stenotypy program at Chicago’s Lasalle Extension University, the machine revived the Ireland keyboard, although it’s not entirely clear which entity in Chicago was manufacturing it prior to the founding of Stenographic Machines in 1938. The machine in our collection was kindly donated by an Indiana court reporter, Jennifer Morrow.]

Milton Wright, whose past business background was in real estate, had managed to breathe life back into the fading Stenotype brand. Now, he pondered raising the value of his new property with some good old fashioned rehab work.

“The machine was unreliable and noisy,” Robert Wright recalled. “My father asked me—I was then working in a research outfit outside of Chicago—to do something about this machine. My degree was in physics. I couldn’t get a job. I called myself an engineer. Anyway, I spent probably four or five years part-time working on this old machine with a young toolmaker who would make the parts up for me as I designed them. And we produced a clutch—the old clutch never worked—and five other improvements, and we got six patents on this.”

What Robert doesn’t mention is that he was also simultaneously studying patent law at Northwestern University, en route to becoming an attorney.

“When my father left LaSalle to form Stenographic Machines, I gave him the six patents. Elsie Price, his secretary, had written the textbooks, and she gave him the complete textbooks. This was the creation of Stenographic Machines. Incorporated in May 1938.”

Machining the Machines

“The first Stenograph machine was made December 17, 1939. World War II set in in 1941, at which time the government took the metal away from all manufacturers that were not in munitions. At one time I found and bought 20 tons of scrap aluminum which my father was able to trade for 10 tons of steel to make more machines with.” —Robert T. Wright

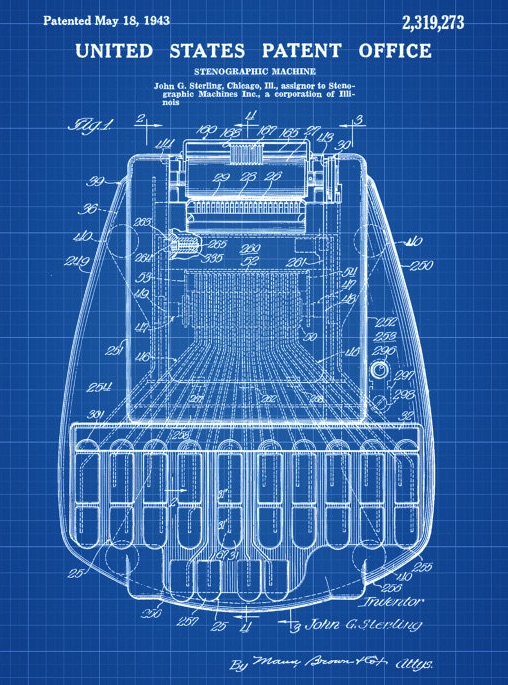

Robert Wright doesn’t mention John G. Sterling in his account of the Stenograph’s origins, but it was Sterling who actually applied for several of the key early patents (under license to Stenographic Machines Inc.) and was credited as the machine’s first inventor. In a 1939 patent application, Sterling laid out in great detail how the new Stenograph would separate itself from the Stenotype and other flawed instruments already on the market.

“Some of the more important objects of the invention, therefore, are as follows:

1. To hold weight to a minimum by the use of lightweight materials and by a general simplification of the machine as a whole.

1. To hold weight to a minimum by the use of lightweight materials and by a general simplification of the machine as a whole.

2. To improve the appearance of the machine and make it easier to grasp in moving it from place to place.

3. To reduce the overall dimensions of the machine, and at the same time increase its sturdiness and ability to retain adjustments even when the machine is handled roughly.

4. To reduce manufacturing costs by organizing the elements of the machine into sub-assemblies.

5. To provide a dependable clutch mechanism for feeding paper into the machine, which continuously gives silent operation and is readily adjustable.

6. To employ a ribbon mechanism that will provide uniform type impressions on the paper.

7. To use a ribbon that is substantially less expensive than those now commonly used in stenographic machines.

8. To improve the means for handling the paper fed into the machine and increase the paper carrying capacity.”

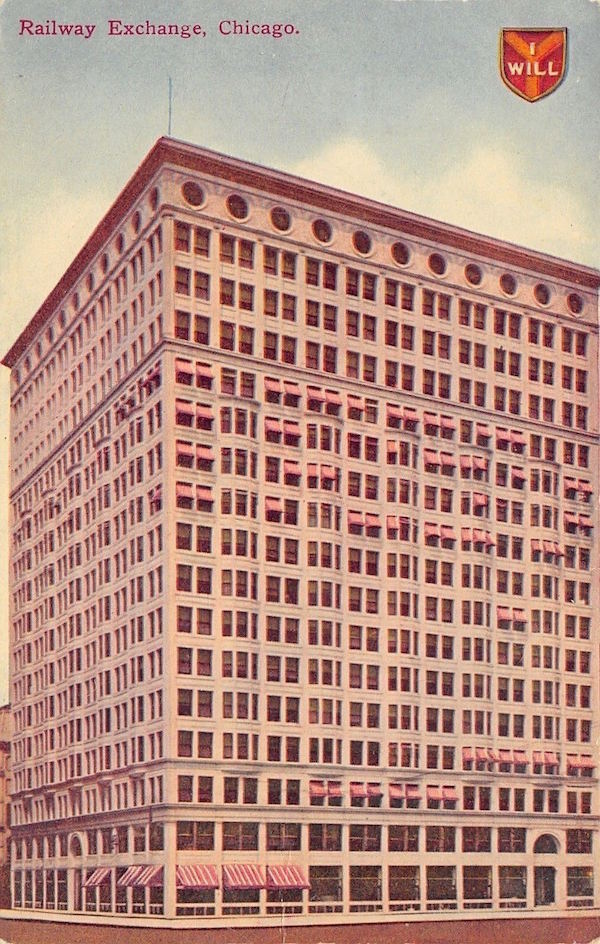

With patents applied for and money in pocket, the first Stenograph offices were established in 1939 at 80 East Jackson Blvd, in the Railway Exchange Building [pictured below]. As had been the case during his days at LaSalle, however, Milton Wright had no intentions of handling the production of his machines in-house. Instead, he needed to find new investors and a reliable mass manufacturer.

“My father took one of these models that we had made,” Robert Wright said, “and we tested them with Chicago reporters first. They were friendly. [Milton] then flew around the United States to the business schools that he had previously enlisted to teach the old Stenotype system, and sold them on the idea of helping finance this new machine which we called the Stenograph.

“My father took one of these models that we had made,” Robert Wright said, “and we tested them with Chicago reporters first. They were friendly. [Milton] then flew around the United States to the business schools that he had previously enlisted to teach the old Stenotype system, and sold them on the idea of helping finance this new machine which we called the Stenograph.

“He sold $22,500 worth of preferred stock and came home with the money in his pocket. He also sold firm orders for 2,500 machines for $50,000, which he banked at the Harris Trust. This was in 1938-39. The tools actually cost $82,000. He borrowed the rest of the money on his life insurance and paid for the tools, which are now insured for $1.5 million.

“Mr. [Herbert] Hedman contracted to make the machine. He had it tooled and manufactured the machine under contract. Stenographic Machines paid Mr. Hedman $17.50 for each Secretarial model and $22.50 for each Reporter model. The company wholesaled this at $37.50 and $40.50 and retailed it at $52.”

As you can see on the 1940s era Stenograph Reporter model in our collection, the nameplate clearly states that the machine was “Manufactured by The Hedman Company, Chicago, USA,” which was headquartered at 1158 W. Armitage at the time. It was a logical partnership, since Herbert Hedman (and his father Max before him) had been producing the famed F&E Check Protector Machine for over 20 years. According to some additional evidence and the insider knowledge of Frank Chvojcsek, however, it’s possible that Hedman may have actually outsourced its work on the Stenograph, too.

[Early Stenographs like ours were clearly manufactured by the Hedman Company . . . or not.]

[Early Stenographs like ours were clearly manufactured by the Hedman Company . . . or not.]

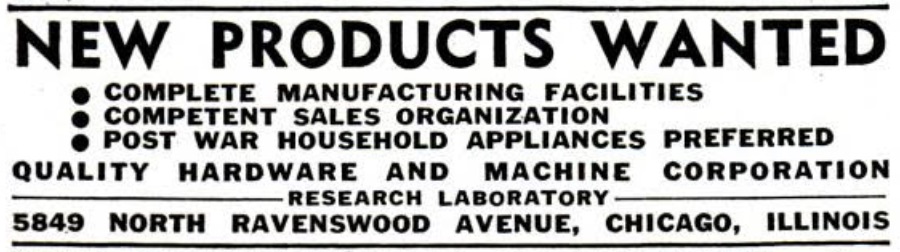

From what Frank has heard over the years, a company called the Quality Hardware and Machines Corporation was the actual manufacturer of the early devices. There are a couple breadcrumbs to support the theory, too:

1. After the war, according to court records, Stenographic Machines, Inc. formed an unlikely partnership (aka an illegal monopoly) with its main rival and Milton Wright’s old employer—LaSalle/Stenotype. “In October, 1948, LaSalle was desperately in need of machines and finally approached Stenographic Machines Inc. in an effort to supply it temporarily with Stenograph machines and eventually with a new model of Stenotype machine. . . Under the provisions of the contract, Stenographic Machines Inc. agreed to aid LaSalle in developing a new model Stenotype and to have those machines manufactured by Stenographic Machines’ manufacturing source.”

2. A 1950 issue of Die Castings magazine identifies Quality Hardware (by then a division of Continental Copper & Steel Industries, Inc.) as the “manufacturer of the LaSalle Stenotype for Stenographic Machines, Inc.” Since we know Stenographic Machines was using the same manufacturer for both the Stenograph and Stenotype by this point, deductive reasoning would suggest that Quality Hardware, located at 5849 North Ravenswood Avenue, was doing the heavy lifting for the Hedman Company by the time our museum artifact was made in the late 1940s.

From what I can tell, Quality Hardware was basically a gun-for-hire manufacturing company, taking on work for other businesses and wholesalers without necessarily stamping their own name on it. Interestingly, one of their contracts included working with the University of Chicago to make non-bonded uranium slugs for the Manhattan Project during the war.If Hedman did seek out Quality Hardware’s help during this same period, a lot of early Stenographs might have been built in the same building as a key component in the development of the atomic bomb.

Aaaaanyway, we might never know for sure where our specific little Stenograph rolled off the assembly line, but by the early 1950s, things became a lot simpler to track. After moving its corporate headquarters to 318 S. Michigan Avenue in 1950, Stenographic Machines Inc. ended its relationship with Hedman two years later, and finally established its own manufacturing plant in Skokie at 8040 Ridgeway Avenue [Frank believes they might have poached a couple workers from Quality Hardware in the process].

[Above: 8040 Ridgeway in Skokie, Stenograph’s manufacturing facility from 1952-1964]

[Below: A newspaper ad looking for female workers, 1960]

“We took over manufacture of the machine because [Hedman] started downgrading the quality,” Robert Wright explained. “We had to overhaul every machine he made the last two years. There are 500 parts in it, and we couldn’t contract any of those parts because we could not find any manufacturer to maintain the tolerance necessary to produce the quietness and absolute reliability. We had to buy our own machine tools and make the parts ourselves, all except the screws and round shafts. We very seriously hardened—this was tube steel hardening, the best there is—and ground and polished every shaft and every bearing in that machine.

“A human hair is three-thousandths of an inch thick. The clearances in there were five-ten-thousandths. You couldn’t put one-third the thickness of a human hair in the bearings. That is how expertly it was done. . . . Charles Kettering of General Motors [a man who held 186 U.S. patents of his own] said at at a public hearing, ‘The best piece of machinery I know in the world is the Stenograph.’”

“A human hair is three-thousandths of an inch thick. The clearances in there were five-ten-thousandths. You couldn’t put one-third the thickness of a human hair in the bearings. That is how expertly it was done. . . . Charles Kettering of General Motors [a man who held 186 U.S. patents of his own] said at at a public hearing, ‘The best piece of machinery I know in the world is the Stenograph.’”

That Kettering quote is unsubstantiated, by the way, but kudos to Robert Wright for showcasing his own dictation skills.

Incidentally, the Hedman Company came out with its own shorthand machine years later, and tried to undercut Stenograph in the process. It failed and quickly disappeared.

Cold War Heroes

“The company grew to where it is now on two bases. One is extremely high quality of a product in the machine. The second was the recognition that all of our customers were human beings and had to be treated as such.” —Robert T. Wright

“I rarely worked directly with Robert Wright,” adds Frank Chvojcsek, “but he had a philosophy that we all followed at Stenograph, that anything is possible.”

This philosophy was not limited to the gradual design improvements of the Stenograph machine. During the Cold War, the braintrust at Stenographic Machines Inc.—if you believe Robert Wright’s dramatic retelling—were also right there at the front lines, helping the U.S. Government gain an espionage edge on the Soviet Union. Forget the Space Race. The real drama was in the stenograph decoding game.

“We got called up by IBM during the war,” Wright said, “and we worked with them for many years to help them rapidly translate the Russian language. An IBM computer was going to do this, but they couldn’t find any way to get the input into the computer except through our keyboard. . . . My wife Ruth was so important in the process. She was a linguist. In six months at night school she developed sufficient capability in the Russian language to speak and write it. Because she was a Stenotypist and student of this keyboard, she developed a keyboard which only made four little changes in our present keyboard, and you could write the Russian language on it.

“We manufactured the machine; the military used it; and we translated everything that came out of Russia by radio. We trained 200 English-speaking Russians to operate the machine. Everything around the world the Russians said, we had, and we translated it with this. They also translated Isvestia and Pravda and put in on the President’s desk every morning.

“I had a guy who managed to get the machine and notes out of the Kremlin every night, and we managed to translate these. The Russians had copied our version of their machine, and they had Russian Stenotypists, and we got the notes out of the wastebasket every night.

“I had a guy who managed to get the machine and notes out of the Kremlin every night, and we managed to translate these. The Russians had copied our version of their machine, and they had Russian Stenotypists, and we got the notes out of the wastebasket every night.

“This really ought not be publicized.” [oops]

“We were engaged in this from about 1944 or 1945 until 1960. All during the Cold War we were beating the pants off the Russians. Everything they did, we knew—everything. . . . We had a great relationship with IBM for many years. They assisted us; we assisted them; and we did fabulous things in the intelligence field.”

To Be Quite Frank

During the height of Stenograph’s secret spy era in Skokie, in 1956, company founder Milton H. Wright died at the age of 80, leaving the business officially in the hands of his 50 year-old son.

A few years later, Robert Wright rolled out the first plastic Stenograph machines. He also hired a young Frank Chvojcsek to join a relatively small engineering department in 1964.

“Back then,” Chvojcsek says, “all of the employees worked in a pretty dark environment [at the Ridgeway factory in Skokie] and usually were assigned tasks only within their particular department. In 1965, though, Stenograph moved to a new location [7300 Niles Center Rd. in Skokie], which was brighter, larger, and air conditioned, and just presented a much better working environment. Later on, the employees would also be trained to be able to work in multiple departments on any given day.

“Back then,” Chvojcsek says, “all of the employees worked in a pretty dark environment [at the Ridgeway factory in Skokie] and usually were assigned tasks only within their particular department. In 1965, though, Stenograph moved to a new location [7300 Niles Center Rd. in Skokie], which was brighter, larger, and air conditioned, and just presented a much better working environment. Later on, the employees would also be trained to be able to work in multiple departments on any given day.

“My most memorable accomplishment was when I was given the lead on a new housing design for the 1970 Secretarial / Reporter models. The only direction given from Robert Wright was that the new design be tear-drop and rounded in shape. After a few discussions I was able to produce a wood model of the Secretarial. At that time the Secretarial was the preferred unit and the Reporter would take its shape from the Secretarial. Once the wood model was accepted, the design was released to the industrial designers for detail drawings, then to the model makers and finally to the model making shop for tooling. The combined number of those units built at its highest point was 15,000 units per year. By 1983, the Secretarial unit was discontinued due to low production, and the Reporter model became the Professional model.

“In the years since, I have been involved in every design on the mechanical side up to the current Luminex.”

[Paper-free and electronic, but the current Stenograph Luminex is still quite familiar looking]

[Paper-free and electronic, but the current Stenograph Luminex is still quite familiar looking]

Because Stenograph absorbed most of its remaining competition by the end of the 20th century, it’s hard to imagine there is a soul on earth who knows more about the Stenograph and its many forms than Frank Chvojcsek. And while he wasn’t exactly mentored by Robert Wright, he certainly carries on the founder’s passion for the equipment.

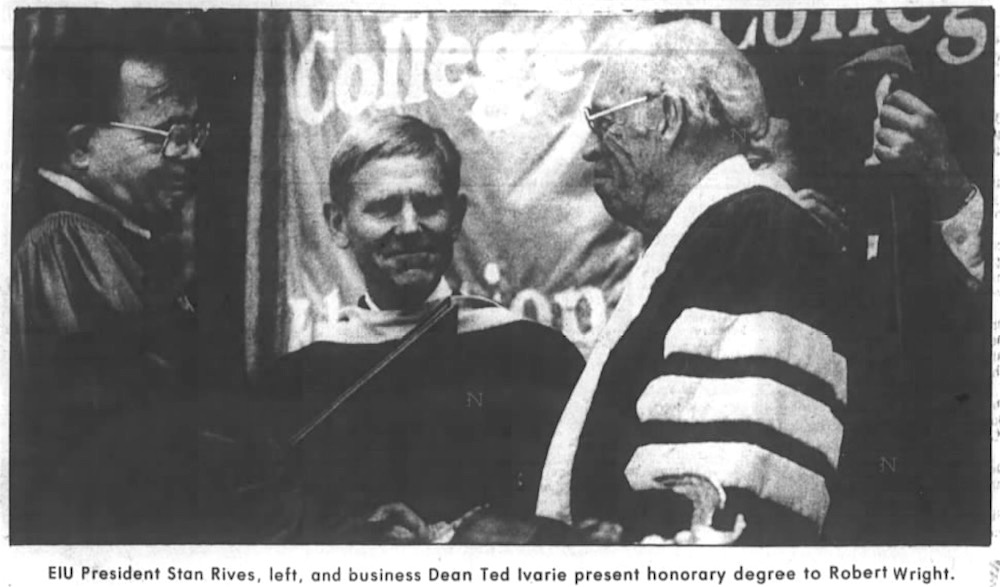

Robert Wright himself remained in his role as president of Stenograph until retiring in 1978, and he never completely separated himself from its operations. Back in the 1960s, he also co-founded the College of Lake County in Grayslake, IL (where he eventually served as Chairman during the mid 1970s), and created the Stenograph Research Foundation at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston.

In 1989, roughly a decade before his death, Eastern Illinois awarded Wright an honorary doctorate for his years of public service and creative business leadership. Around the same time, Stenograph left Skokie for a new facility in Mt. Prospect. It would remain there for 20 years, before relocating to its current HQ, 596 W. Lamont Rd. in Elmhurst, in 2009.

Sources:

Stenographic Machine – U.S. Patent 2,319,273

Stenograph Hand Book, published by Stenographic Machines Inc., 1940

“A History of the Shorthand Writing Machine,” by Stenograph LLC

Die Castings, Vol. 8, 1950

Chicago Tribune, December 24, 1925

“Stenographic Machines Inc. v. Federal Trade Commission, 233 F.2d 755 (7th Cir. 1956)”

“History of the Stenograph Machine” by Robert T. Wright w/ Richard Mowers (c. 1980s)

Robert T. Wright obituary, Chicago Tribune, October 28, 2000

“Rives to Grads: ‘Live on Edge of Significance'” – Journal Gazette (Mattoon, IL), August 7, 1989

‘Lease Three Floors in Building for $230,000 Rental” – Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1950

“Stenograph Moves to New Expanded Quarters” – Journal of Business Education, Vol. 41, 1965, Issue 1

Archived Reader Comments:

“Fascinating. Thank you! Stenograph writers are the best! Will be researching more about the Stenograph/Russian spying, for sure!” –Jana, 2018

Will be researching more about the Stenograph/Russian spying, for sure!” –Jana, 2018

I have a stenograph machine, Serial No. 6610935 that I used in the 1970 at school. Can you tell me if it is worth anything. It is in perfect condition and has a roll of paper with it. The hard cover is in good condition too. Thank you for your help.

I have a stenographic machine that my dad used in the 1940s that is in perfect condition. Do you have any suggestions as to what to do with it?

Thanks!

I have the same machine you have except in the back where it says patented mine says patents pending is it worth any money?

I inherited an original model circa 1947. As pictured above.

It is in excellent condition, complete with tripod and case.

Wondering if anyone interested in purchasing this for their collection.

Hi, I have one that’s exactly like it, but it said patent pending. Also it has initial of JHL. Do you know anything about it?