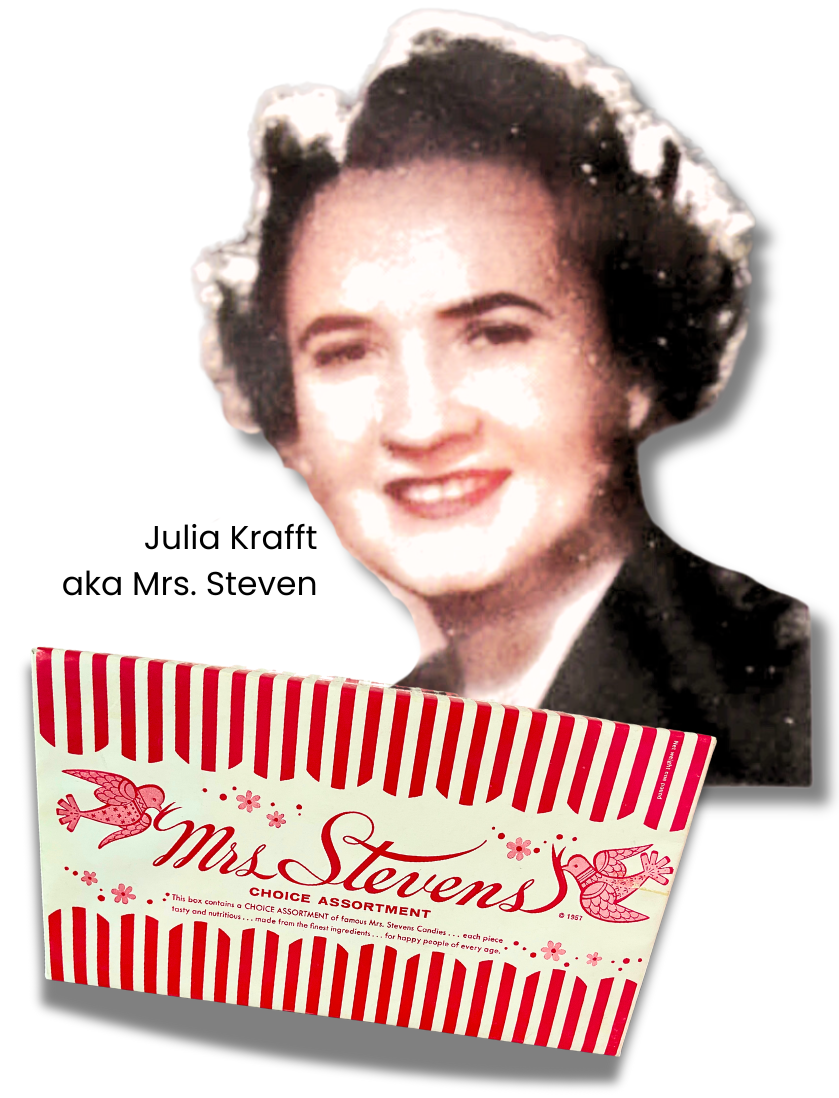

Museum Artifact: Mrs. Steven’s Candies Tins, 1920s-1960s

Made By: Steven Candy Kitchens, Inc., 611 N. Sacramento Blvd., Chicago, IL [Humboldt Park]

Donated By: Chaleen Stevens (no relation)

“It’s easy to make money in your kitchen, even if you don’t have any business sense. There are many women who could develop profitable small businesses which could be handled from their homes and still not interfere with their domestic duties.” –Julia Steven Krafft, 1950

Even in the roughest years of the Great Depression, Chicagoans were beyond spoiled for options when it came to the cure-all known as candy. Virtually every block in the city had a notable confectioner plying their trade, and every neighborhood, in turn, seemed to have its own factory building now mass producing sweets for wider distribution. Mars was here; plus Curtiss, Williamson, Brach, DeMet, Bunte, Fannie May, Ferrara, and on and on. One of the more unique success stories, though, was that of Mrs. Steven’s Candies; a genuine one-woman DIY kitchen that grew into a beloved local institution from the 1920s to the 1960s, employing more than 500 Chicagoans at its post-war height.

Even in the roughest years of the Great Depression, Chicagoans were beyond spoiled for options when it came to the cure-all known as candy. Virtually every block in the city had a notable confectioner plying their trade, and every neighborhood, in turn, seemed to have its own factory building now mass producing sweets for wider distribution. Mars was here; plus Curtiss, Williamson, Brach, DeMet, Bunte, Fannie May, Ferrara, and on and on. One of the more unique success stories, though, was that of Mrs. Steven’s Candies; a genuine one-woman DIY kitchen that grew into a beloved local institution from the 1920s to the 1960s, employing more than 500 Chicagoans at its post-war height.

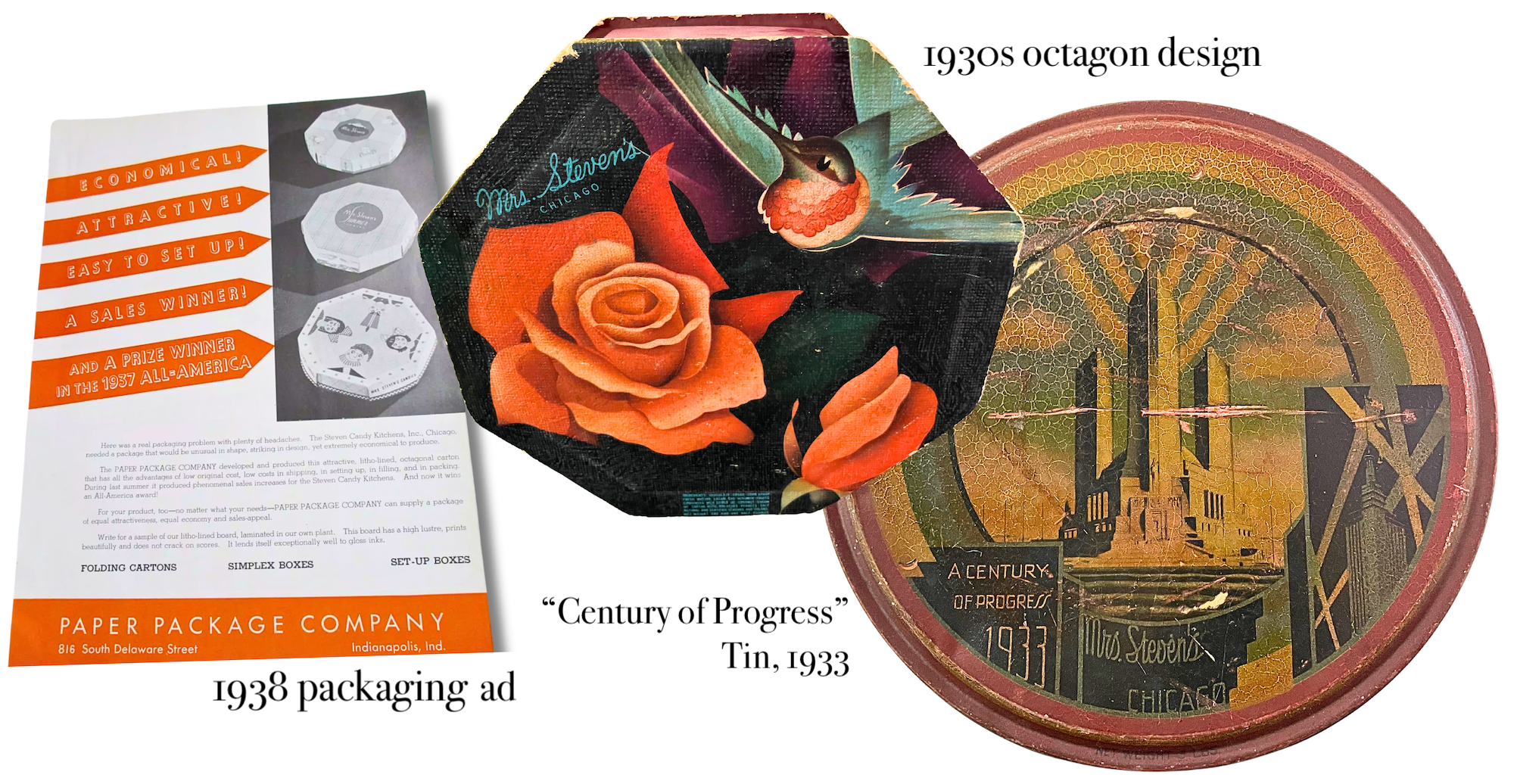

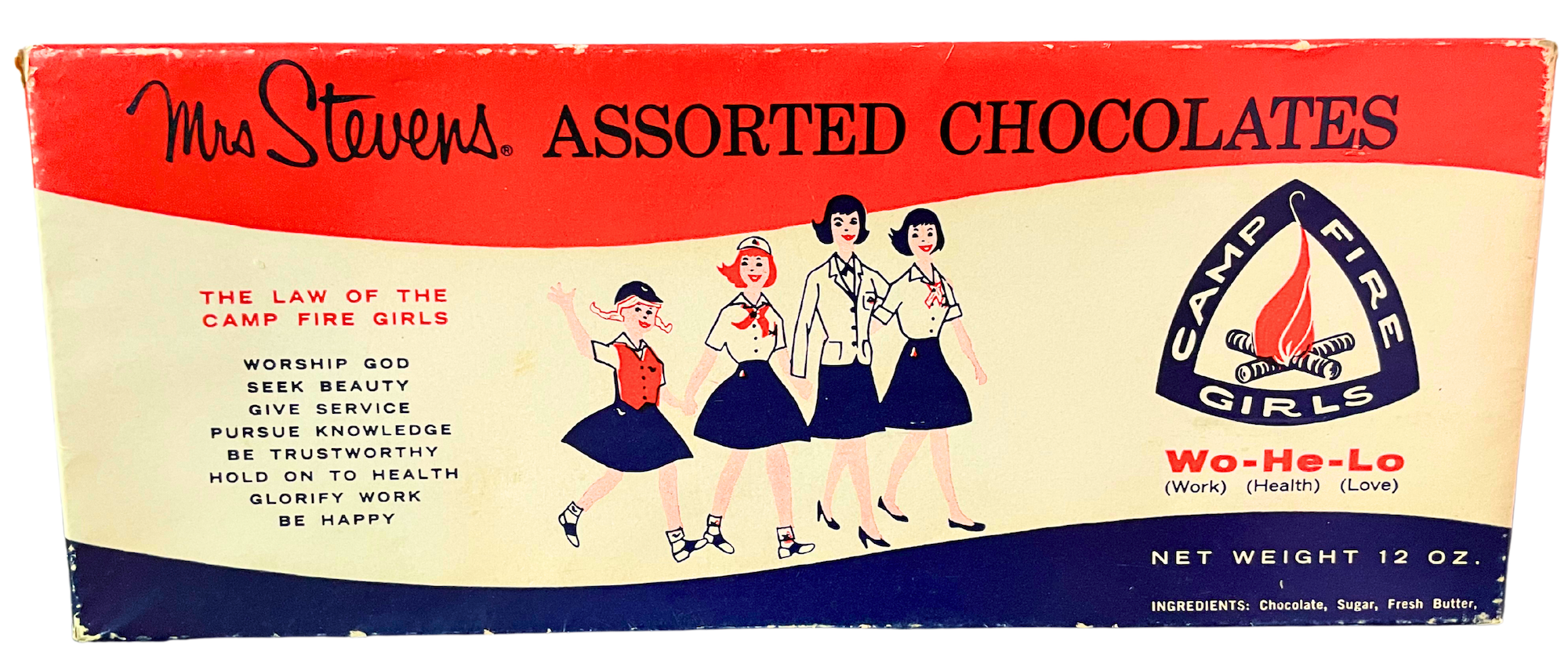

Defunct for more than 50 years now, the nostalgia for Mrs. Steven’s actual product has predictably waned, but an interesting legacy has carried on in the form of the company’s 10-inch wide circular candy tins, which usually sold for a buck in the 1930s. Though the delicious prizes inside probably provided all the necessary enticement for would-be buyers back then, Steven and its packaging partners went the extra mile by constantly putting out new tin designs. Floral options were always a good bet, but seasonal variations (Santa, Easter Bunny, Halloween witches) and special event editions (1933 World’s Fair) inspired people to hold on to their tins long after the contents had been consumed. Repurposed as handy little storage containers, these colorful Steven tins retain a lot of charm, especially from the perspective of a candy lover in the disposable, plastic-wrapped nightmare of the 21st century.

The Made In Chicago Museum is pleased to have a very large selection of original Mrs. Steven tins in our collection, donated by life-long collector Charleen Stevens (no relation). You can see the full assortment of that collection in one mesmerizing gif below, followed by a complete history of Mrs. Steven Candies.

History of Mrs. Steven Candies, Part I: Mrs. Clark

The Mrs. Steven in question was Julia Steven Krafft, the farm girl turned big city entrepreneur. Born Julia Clark in 1896, she grew up on a small farm near Wayne, Illinois, about 40 miles west of Chicago. Her parents were not necessarily devoted to the land, though. George Clark, her father, was a salesman at heart. He also had a progressive view on his daughter’s career prospects, sending her to the Ellis Business College in Elgin, IL, after she’d finished her basic schooling.

“Young Miss Clark was greatly intrigued by arithmetic,” according to a feature in a 1953 issue of the Chicago Tribune. “She had a quick mind and developed her own way of finding solutions to problems. The head of her school, Frank W. Ellis, encouraged her to do this instead of compelling her to follow the conventional methods. She learned to add columns of figures at sight. In this she worked out little mental short cuts which proved to be of great value later. She is a whiz at finding any errors in a restaurant bill.”

“Young Miss Clark was greatly intrigued by arithmetic,” according to a feature in a 1953 issue of the Chicago Tribune. “She had a quick mind and developed her own way of finding solutions to problems. The head of her school, Frank W. Ellis, encouraged her to do this instead of compelling her to follow the conventional methods. She learned to add columns of figures at sight. In this she worked out little mental short cuts which proved to be of great value later. She is a whiz at finding any errors in a restaurant bill.”

Initially parlaying her math skills into a bookkeeping job, Julia worked her way up to an office manager role with a thread works during World War I, earning $200 a month–”a munificent wage at the time for a woman.”

Julia Clark became Julia Steven after marrying a Wheaton farmer named Leslie B. Steven in 1919. A daughter, Virginia, soon followed, and at the age of 25, Julia was happy to enter into a life of rural domesticity; or at least she claimed as much decades later.

“I was very happy because a girl raised on a farm thinks of nothing more aggressive than being a farm wife,” she told International News Service writer Phyllis Battelle in 1950. “I was, at first, perfectly content to stay in my kitchen and make fudge . . . which was always my specialty.”

[Packaging fpr Mrs. Steven’s “Jungle Jollies” animal candies, 1940s]

Still a student of numbers, though, Julia started looking into her family’s finances in the early 1920s and came to the realization that running a small farm in Illinois was not exactly a lucrative life path for a growing family. Most farmers in the area didn’t clear $1,000 in annual earnings (that’s less than $18,000 in 2024).

“That news,” Julia said, “was discouraging. I wanted my little girl to have more than that, for herself alone. So I thought of ways in which I could perhaps make some supplementary money.”

Encouraged by her sister Bertha, Julia approached a local bakery in Wheaton about supplying fudge and other candies for their shop. The shop owner agreed and sold the candy for $1 a pound, keeping a 10-cent commission.

“Soon the people of Wheaton were talking about Mrs. Steven’s candy and buying it,” according to a 1941 article in Sales Management.

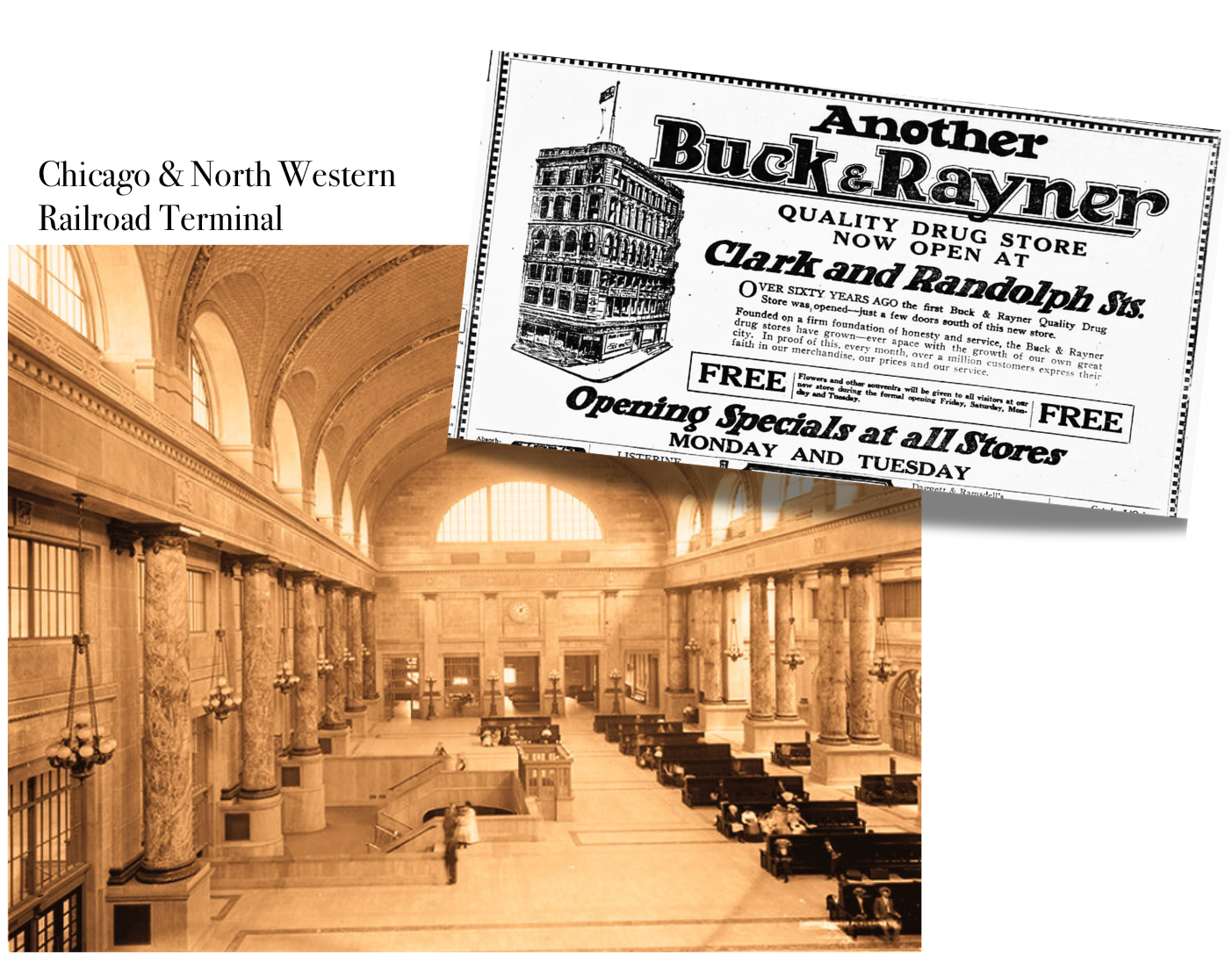

By around 1925, Julia was feeling bold enough to take a shot at finding a seller in Chicago. On something of a whim, she took a train to the city and made her first pitch minutes later at the Buck & Rayner drug store right there at the North Western railroad terminal. Luck was smiling on her. Not only did the store agree to a deal, but its owner, Walter Krafft, would ultimately become her second husband (Julia kept the Steven surname after her divorce from Leslie Steven, using it more as a business alias).

By around 1925, Julia was feeling bold enough to take a shot at finding a seller in Chicago. On something of a whim, she took a train to the city and made her first pitch minutes later at the Buck & Rayner drug store right there at the North Western railroad terminal. Luck was smiling on her. Not only did the store agree to a deal, but its owner, Walter Krafft, would ultimately become her second husband (Julia kept the Steven surname after her divorce from Leslie Steven, using it more as a business alias).

Part of the original deal with Buck & Rayner also included the rather important caveat that Mrs. Steven would start manufacturing her candies locally, in Chicago, in order to keep the stock flowing. And so, the quiet farm life was abruptly abandoned as the young mother suddenly found herself seeking out factory space downtown. As to whether this major upturning of expectation directly led to the end of her first marriage, we don’t know. But her husband Les was soon out of the picture, and it was instead Julia’s sisters, Bertha and Mildred, who became her trusted business partners as “Mrs. Steven’s Home Made Candies” slowly grew.

Part II. Mrs. Steven

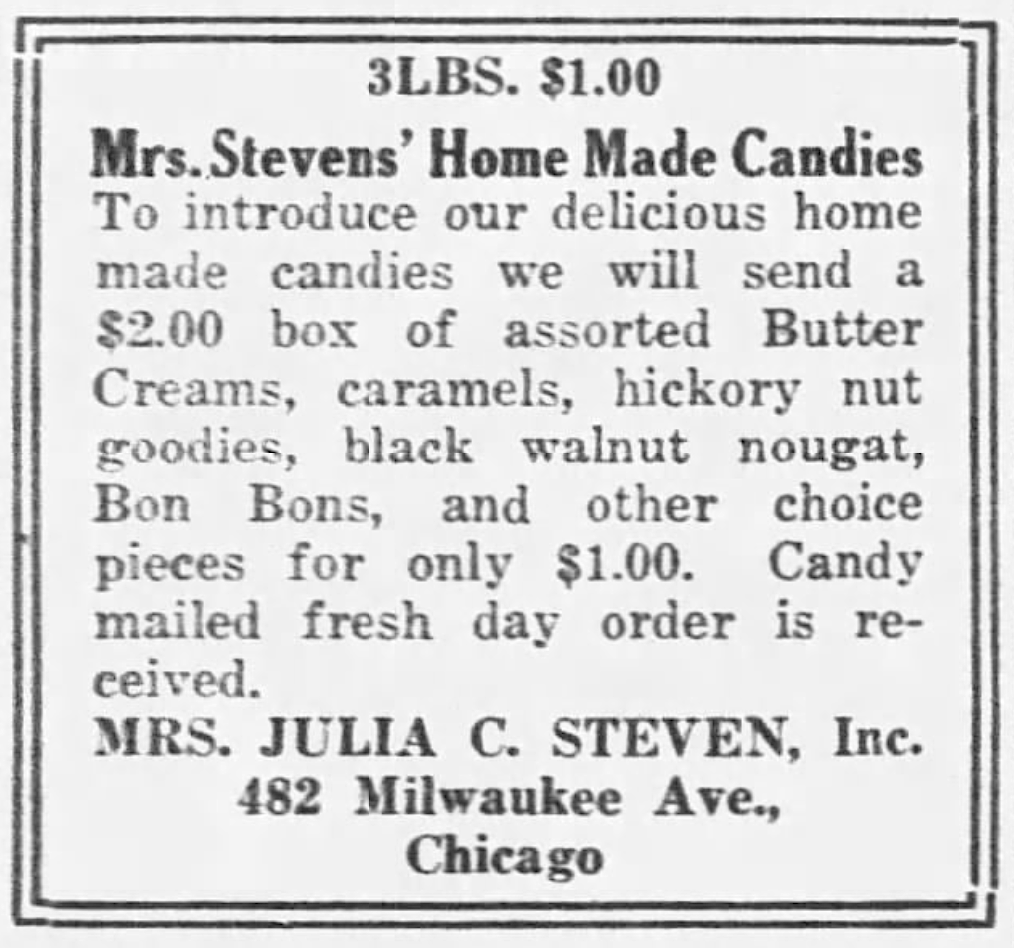

Investing her life savings of $1,000 into the venture, Julia Steven rented her first one-room chocolate making facility inside a building on North Wells, making everything from “nougat to nutballs.” It was a clunky start. She couldn’t keep the candy from melting before it could be transported. Subsequent moves to better spaces at 482 N. Milwaukee and another on the corner of Milwaukee, Halsted and Grand Avenue led to improvements, but when her main supplier Buck & Rayner was sold to another company, Julia had to scratch together new partnerships to stay afloat.

Fortunately, it didn’t take long for “grocers, tobacco store-keepers, and even retail clothing shops to start bidding for the succulent product, and almost immediately business took a 50 percent rise.”

As Mrs. Steven later recalled, she was then able to “open three candy shops [of our own] in Chicago. Then somebody told us how smart it would be to package out candy in cans, so that it could be shipped fresh, all over the country. Since then, there’s been no stopping the business.”

Using her experience both as a savvy bookkeeper and financially strapped farm woman, Steven carefully strategized how best to present her product to the market. During the Depression years, “one of the things she determined to discover,” according to Sales Management, “was the unit price, in coin, that Mr. and Mrs. John J. Public would give up with the least pain when bent on candy buying. One might think that very simple, but it took plenty of watchfulness and experimentation to find out.”

The magic number, it turned out, was still one dollar, and indeed, more than half of Mrs. Steven’s sales through the 1930s remained $1 candy boxes, usually weighing 2-3 pounds. Advertising was kept to a minimum, but certain flourishes helped create a distinct brand identity.

“Outside of the candy itself,” Sales Management noted in 1941, “the package is important. [Mrs. Steven] changes her featured packages, mostly in tin containers, ten times each year. The present package wears a wisp of colorful dogwood on a sky-blue background with a butterfly on it. St. Valentine’s Day was celebrated with a heart-shaped tin box featuring bright red. Mother’s Day brought the heart again, but the background was something between lavender and orchid. Halloween, probably, black and yellow in a different shape, and Christmas, red and green. The color scheme must follow either sentiment or the season. That’s important. It makes for sales.”

“I don’t always select a package because it is beautiful or because, from the point of accepted packaging, it is correct,” Mrs. Steven told Sales Management. “I try to get a package that is new. For example, our heart-shaped tin. It was designed and made by Seymour Products Co., the first tin package of its kind, and I have the exclusive use of it in the United States. The customer likes something different, fresh and new.”

Sales Management went as far as to say that, “Mrs. Steven has probably done more than any other candy manufacturer to popularize the dollar package,” and her corresponding window displays of those packages, at her own stores and affiliated department stores, added to the company’s reputation.

Sales Management went as far as to say that, “Mrs. Steven has probably done more than any other candy manufacturer to popularize the dollar package,” and her corresponding window displays of those packages, at her own stores and affiliated department stores, added to the company’s reputation.

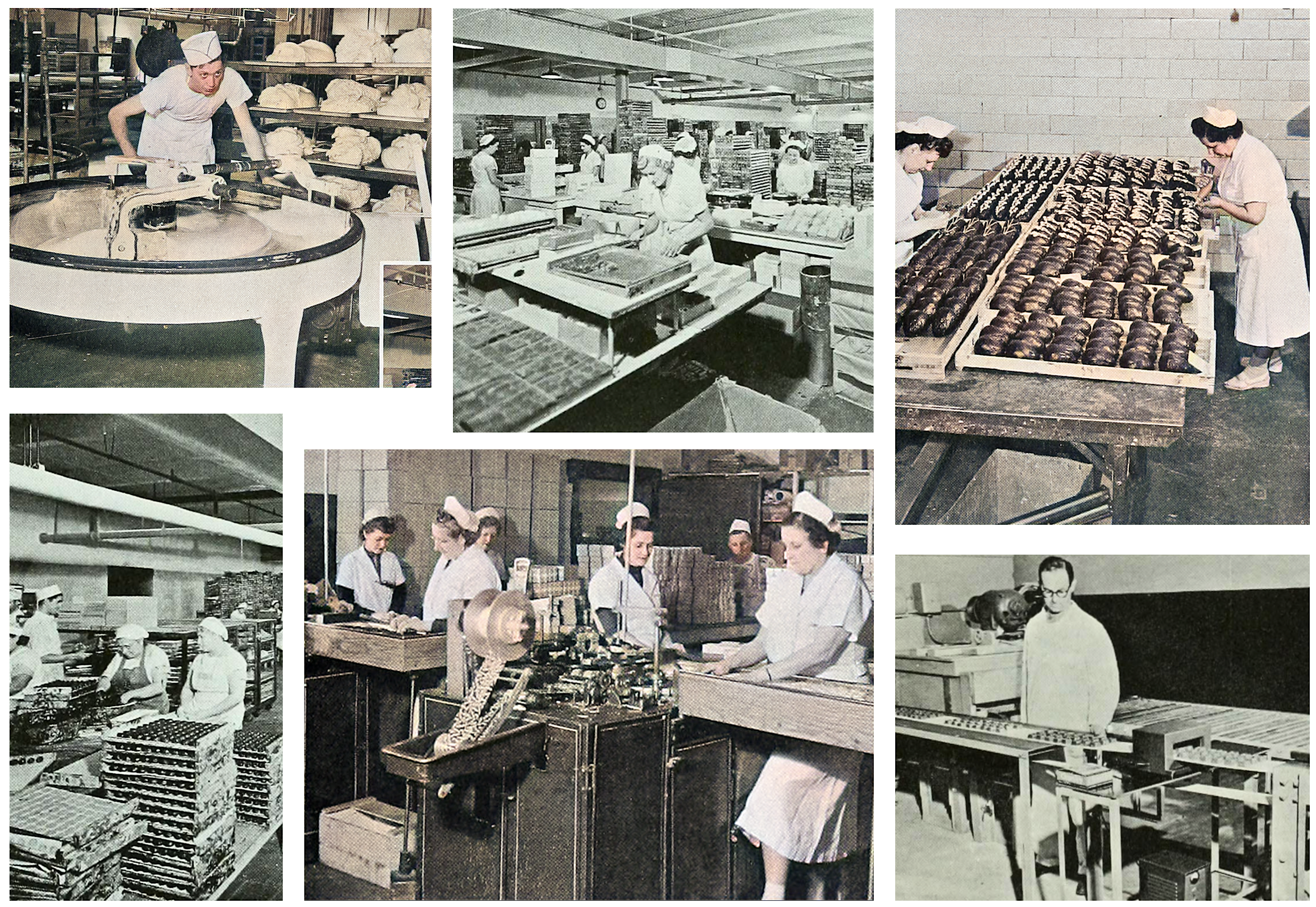

By the early 1940s, there were 16 dedicated Mrs. Steven shops in Chicago alone, plus satellite shops in Milwaukee and New York and a nationwide distribution department. A brand new quarter-million dollar factory in Humboldt Park, at 611 N. Sacramento Blvd., was another proud reflection of the company’s success; covering 43,000 square feet and eventually employing close to 500 workers, almost all of them women. This included Julia Krafft as president, of course, along with her sister Bertha Blinks as secretary and another sister, Mildred Sayer, as vice president. “It’s a women’s business if there ever was one,” Sales Management decreed.

“I still make candy in my own kitchen,” Krafft said shortly after the new plant opened, “but I have 500 candy-makers in my employ who do it better!”

During the war, besides rolling out patriotic tins, Mrs. Steven’s Kitchens took part in various drives for war bonds and supplies for the Allies, including a silk and nylon stocking drive in 1943 that was organized by one of the young candy packers at the plant, Mary Ramson. For her part, Julia Krafft put much of her own newly earned wealth toward the sponsorship of war orphans in Europe, but her soft spot for children always included the kids of Chicago, as well. For close to 30 years, starting back in the early days of the Depression, Julia would welcome local children to her shops for “the Saturday Sampling Club,” handing out free sweets (usually overstock “seconds”) to routinely large crowds of kiddos queuing up outside. She had become something far more than a candy maker or a socialite. She was a genuinely beloved pillar of the community.

[Left: Kids lining up outside a Mrs. Steven shop for the “Saturday Sampling Club,” 1941. Right: Julia Steven Krafft handing out candy in Chicago, 1951]

III. Mrs. Krafft

Despite her big city success, Julia Steven Krafft was still a country girl at heart, and after the war, she began dedicating more of her time to another ample investment. Honey Bear Farm, located outside of Genoa City, Wisconsin, was the Krafft family’s own specially curated Midwestern Shangri-La; a collection of quaint shops and a restaurant amidst lovely rural surroundings and well manicured gardens. Opened in 1951, it remained a popular weekend destination for several decades, particularly for families from Chicago and Milwaukee looking to get out of the city.

“It was no trick at all to round up a half dozen relatives and friends for a 65 mile drive out highway 12 to Honey Bear Farm,” Chicago Tribune columnist Kathryn Loring wrote after a visit in 1958. She happily described “a few hours of browsing thru shops of rural sophistication” and a “luncheon of delectably home cooked flavor.”

“It was no trick at all to round up a half dozen relatives and friends for a 65 mile drive out highway 12 to Honey Bear Farm,” Chicago Tribune columnist Kathryn Loring wrote after a visit in 1958. She happily described “a few hours of browsing thru shops of rural sophistication” and a “luncheon of delectably home cooked flavor.”

“We found Mrs. Walter A. [Julia] Krafft,” Loring added, “owner of the picturesque place, accompanied on an inspection tour of the grounds by her French poodle, Honey Bear–we always forget to ask if the poodle is named for the farm, or the farm for the poodle.”

Now in her early 60s, Julia Krafft seemed to be the living embodiment of squeaky clean Americana at its finest–capitalist achievement combined with humble smalltown charm. She had already sold her controlling interest in Mrs. Steven’s Candy Kitchens in 1956, but seemed content to spend her retirement alongside husband Walter Krafft at their country estate, just a stone’s throw from Honey Bear Farm; which was now operated by her daughter Virginia. When Virginia announced her engagement to the new vice president of Steven’s Candies–Francis Dore–the future looked even brighter.

[Julia Steven Krafft taking calls at work (left) and relaxing at home with husband Walter and their two poodles, 1952]

From here, though, the story takes a much darker turn.

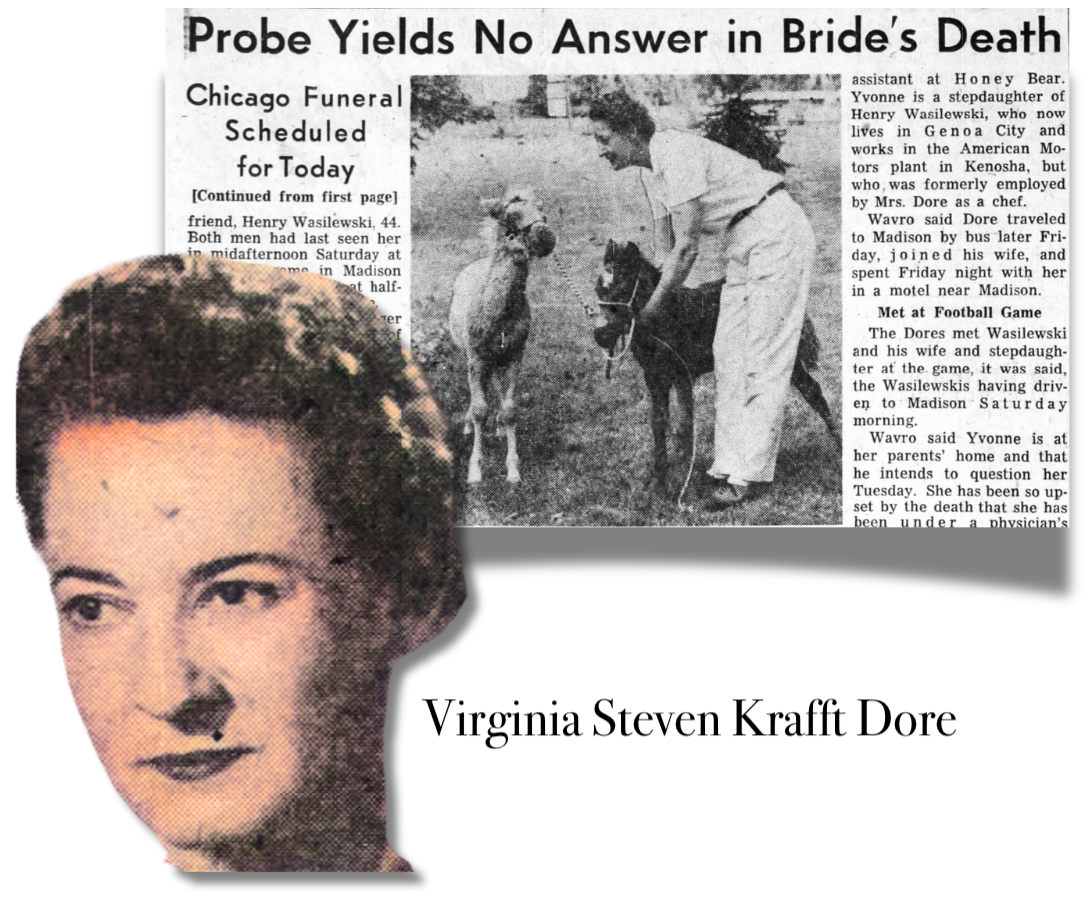

First, in January of 1959, Walter Krafft died from a prolonged illness at the age of 69, leaving Julia a widow. Then, something far more shocking. In October of that same year, just six weeks after her wedding to Francis Dore, Julia’s daughter Virginia Steven Krafft was found dead in her home at Honey Bear Farm. She was only 39 years old.

The cause of death was carbon monoxide poisoning brought on by a car left running in a closed garage underneath the bedroom where Virginia’s body was discovered. Unsurprisingly, though, the circumstances of the death led to immediate questions as to whether this was a horrible accident, a suicide, or foul play. Julia Krafft, a grieving mother in understandable shock, refused to believe it was anything but an accident; a tragic consequence of her daughter leaving the engine of her car running . . . after oddly choosing to drive home alone from a football game she’d attended with her husband and several friends. Francis Dore and those same friends, arriving at the house later that night, found Virginia’s body.

The disturbing incident led to months of police investigations, including interviews with dozens of Honey Bear Farm employees and plenty of grilling of the widower, Francis Dore. There was media speculation as to Virginia’s physical and mental health on the day in question, as well. Just a week after the story broke, newspapers reported that Virginia Dore had told her mother Julia, “only two hours before her death, that ‘things have been bothering me,’ and that she planned to seek the help of Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, author of the book The Power of Positive Thinking.” Virginia was also found to have had a blood alcohol level well over the legal limit at the time of her death.

The disturbing incident led to months of police investigations, including interviews with dozens of Honey Bear Farm employees and plenty of grilling of the widower, Francis Dore. There was media speculation as to Virginia’s physical and mental health on the day in question, as well. Just a week after the story broke, newspapers reported that Virginia Dore had told her mother Julia, “only two hours before her death, that ‘things have been bothering me,’ and that she planned to seek the help of Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, author of the book The Power of Positive Thinking.” Virginia was also found to have had a blood alcohol level well over the legal limit at the time of her death.

By the following spring, after Francis Dore had taken a lie detector test and police had explored various other avenues, Virginia Dore’s death was finally ruled “self caused” as a result of leaving the car running under her bedroom, though no declaration was made as to whether this was intentional or unintentional.

Sadly, the story didn’t end there. When it was revealed that Virginia’s will made no mention of her new husband, it led to several years of court battles between Francis Dore and his mother-in-law Julia Krafft, who–while perhaps not suspicious of Francis as a murderer–was at least not so thrilled about him becoming the new heir to her fortune. A probate court ruled in Julia’s favor in 1962.

By this point, in the early ’60s, DeMet’s Candies had taken over all of the old Steven’s retail locations, and a team of businessmen led by publisher William H. Rentschler had purchased the candy factory on Sacramento Blvd., subsequently renaming the company Stevens Candy Kitchens, Inc. (insultingly pluralized, with no apostrophe). Rentschler presided over the business through the 1960s and opted to change its name again, to Martha Washington Kitchens, in 1966, selling off the Mrs. Steven name one last time before it disappeared fully in the 1970s.

[Workers at the Steven Candy Kitchens plant in the mid 1960s. Clockwise from top left: Candy mixes are swirled in a beater; finished candies are delicately boxed for retailers; large chocolate easter eggs are decorated; candies inspected and sorted; hard candies are wrapped automatically in cellophane; bonbons are hand-dipped to get the perfect coating. Source: Universal World Reference Encyclopedia, 1965]

For understandable reasons, Julia Krafft decided to sell the Honey Bear Farm and other local properties not long after the deaths of her husband and daughter. Honey Bear Farm did carry on through the 1970s under the ownership of the well known Chicago retailer Carson Pirie Scott & Co., but closed for good in the early 1980s.

Julia Steven Krafft spent her final years in Rancho Santa Fe, California, living to the ripe old age of 98. When she died in 1994, the Chicago Tribune described Mrs. Steven’s Candies as a “very popular item in Chicago for several generations.” By that point, though, the brand had already begun to fade into obscurity, kept alive mainly by the colorful old tins still utilized by the thousands for tiny trinket storage. Interestingly, the company’s modernist 1940 factory building at Sacramento Blvd. and Ohio Street is also still standing and looking fairly spiffy, though its current owner is unknown.

“Nothing is so important to the happiness of people as work. The schools should do more in teaching young people how much work can mean to them.” –Julia Steven Krafft

[The former Steven candy factory building at 611 N. Sacramento Blvd, as seen in 2024]

Sources

“Mrs. Steven’s Candy Shops Report 70% Gain in Sales” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 5, 1933

“Award Contract for a $200,000 Candy Factory” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 13, 1940

“Mrs. Steven’s $1,000,000 Candy Business–and How it Grew” – Sales Management, Aug 1, 1941

“Women in War Work” – Chicago Tribune, June 29, 1943

“Confection Magic Pays Candy Queen” – Tulsa World, Aug 13, 1950

“Foster Parent” – Beecher City Journal, Aug 9, 1951

“Four Farms, Philanthropy, Her Family, & Business Keep Chicagoan Occupied” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 26, 1952

“The Road to Success: Sketch of Mrs. Julia Steven, Founder of Big Candy Company” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 7, 1953

“Out Highway 12” – Chicago Tribune, April 13, 1958

“Virginia Krafft Becomes Bride of Francis Dore at Powers Lake” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 6, 1959

“Continue to Probe Death of Wisconsin Socialite” – Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN), Oct 27, 1959

“Hope Heiress’ Will May Aid Death Probe” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 28, 1959

“New Clues in Socialite’s Death, Was She Murdered?” – Des Moines Register, Oct 31, 1959

“Rule Candy Heiress’ Death Self-Caused” – Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1960

“Husband Loses Bid for Wife’s $150,000 Estate” – Chicago Tribune, March 10, 1962

The Universal World Reference Encyclopedia, 1965

“Julia Krafft, 98, Founder of Mrs. Steven’s Candies” – Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1994

“William H. Rentschler” (obit) – Chicago Tribune, Dec 24, 2009

I was in that bldg. in the late 1990s as a truck driver.

They were making Dutch Maid brand kitchen clenser.

A worker there told me that they also made Mustard and that was moved to somewhere in WI.

I have a tin from Mrs. Steven’s candies that my grandmother had. I can’t find a date on it, but it is of a Fawn with palms and flowers around the Fawn. Is there somewhere that will tell me the year this was used?

My mother worked in the office for Steven Candies during WWII and beyond. The owner Mrs Julia (Stevens) Krafft attended the wedding of my parents in 1950. My mom told me the story of this company and the owner/family. It is nothing short of a fascinating story that has the making if a movie.

I have a Stephens Candy Kitchen Christmas tin that my great grandmother used to store buttons. It is red with Santas face on the lid.

I found an old “Mrs. Steven’s” metal candy box and wondered if your company would like yo have it. It was in my Great Aunt’s things & I think it’s probably from the 1940’s. Please let me know before I toss it out. Thank you!

I have a pink plastic Easter egg from Mrs. Steven’s in its original box. Is it of any value ?

My parents told the story of how they met at Orchestra Hall. My dad worked as an usher at Orchestra Hall while attending music school, and Mom worked at a Stevens Candy shop that was apparently in the lobby or next door.

I wonder if you could clarify: Was there a candy shop in the lobby or next door? And are there any photographs?

Thanks for any information!

I think this is the company that my Dad worked at for years. It later became Martha Washington Candies and then that closed down.