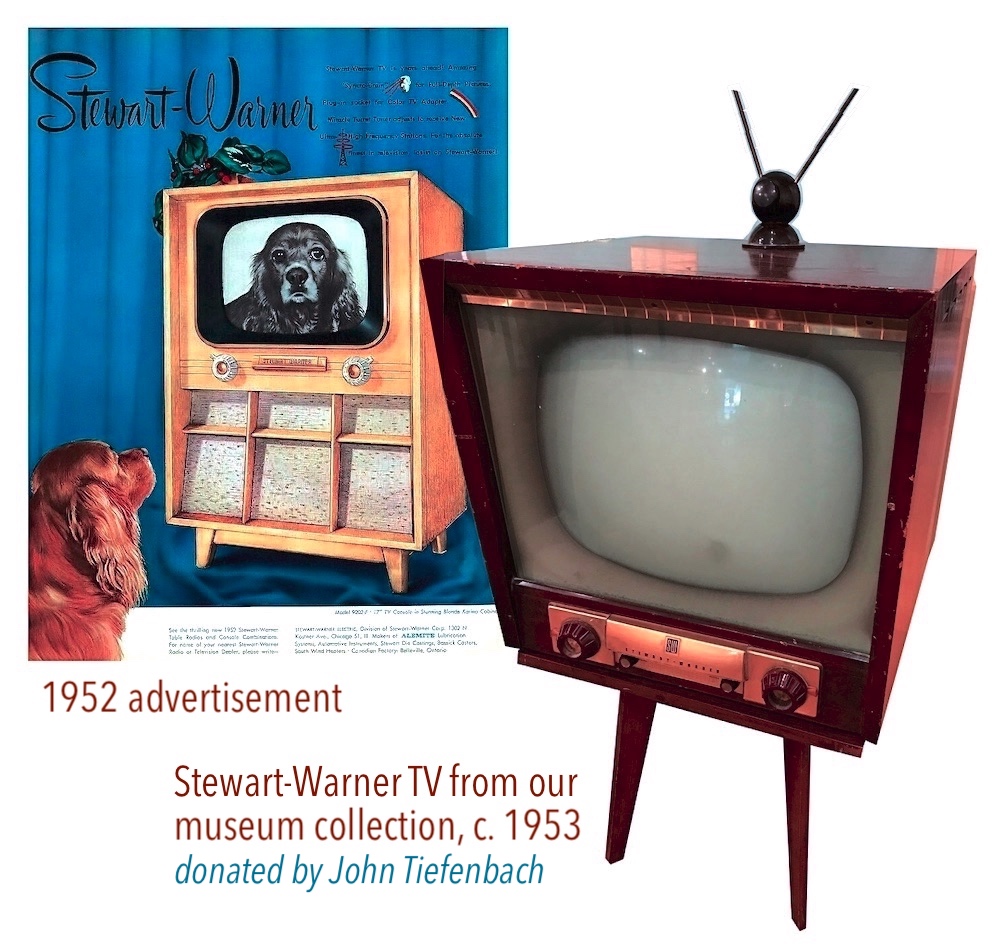

Museum Artifact: Cadet Bicycle Speedometer and Stewart-Warner Television + Stand, 1950s

Made By: Stewart-Warner Corp., 1826 W. Diversey Pkwy, Chicago, IL [Lincoln Park]

“The ‘Cadet’ Bike Speedometer is not a toy! It’s a precision instrument, just like the one on your Dad’s car! It’s made by famous Stewart-Warner, the same company that has made millions of speedometers for cars, trucks, buses and motorcycles.” —Stewart-Warner advertisement, 1956

Stewart-Warner, as the hyphen would suggest, was a company launched from the combined efforts of two men; although the partnership was more like a handshake at the end of a fist fight.

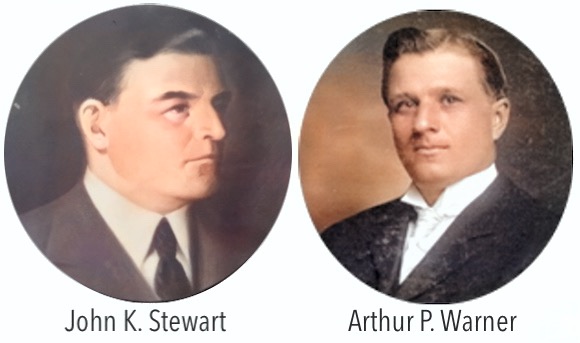

In the early years of the automobile, John K. Stewart of Chicago and Arthur Pratt Warner of Beloit, Wisconsin, were leaders of rival companies, each competing to corner the market on the development of new motor car accessories—particularly the speedometer. No shortage of lawsuits were filed between the Warner Instrument Company and the Stewart & Clark MFG Co., with both sides accusing the other of patent infringement and general chicanery. It was only in 1912, nearly a decade into the feud, that A. P. Warner decided to adopt an “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” strategy, agreeing to merge with his nemesis and form a new entity, the Stewart-Warner Speedometer Corporation.

In the early years of the automobile, John K. Stewart of Chicago and Arthur Pratt Warner of Beloit, Wisconsin, were leaders of rival companies, each competing to corner the market on the development of new motor car accessories—particularly the speedometer. No shortage of lawsuits were filed between the Warner Instrument Company and the Stewart & Clark MFG Co., with both sides accusing the other of patent infringement and general chicanery. It was only in 1912, nearly a decade into the feud, that A. P. Warner decided to adopt an “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” strategy, agreeing to merge with his nemesis and form a new entity, the Stewart-Warner Speedometer Corporation.

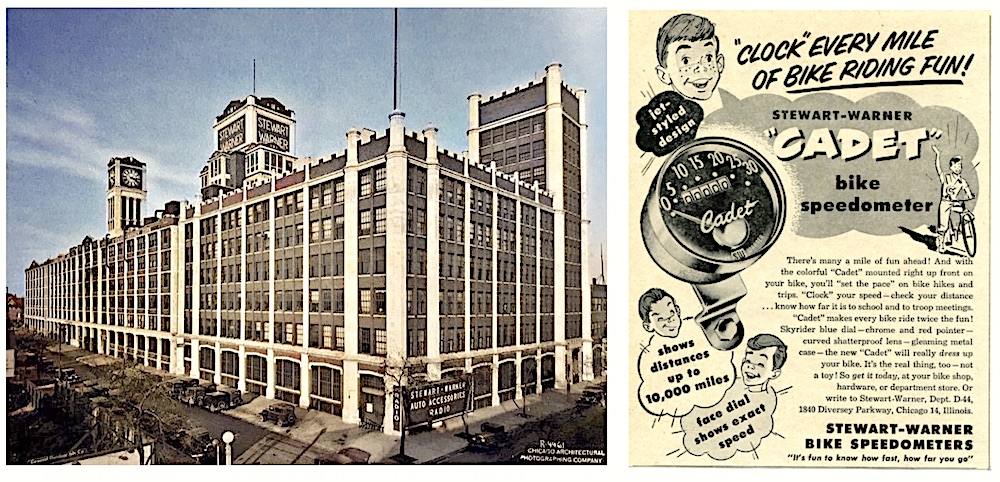

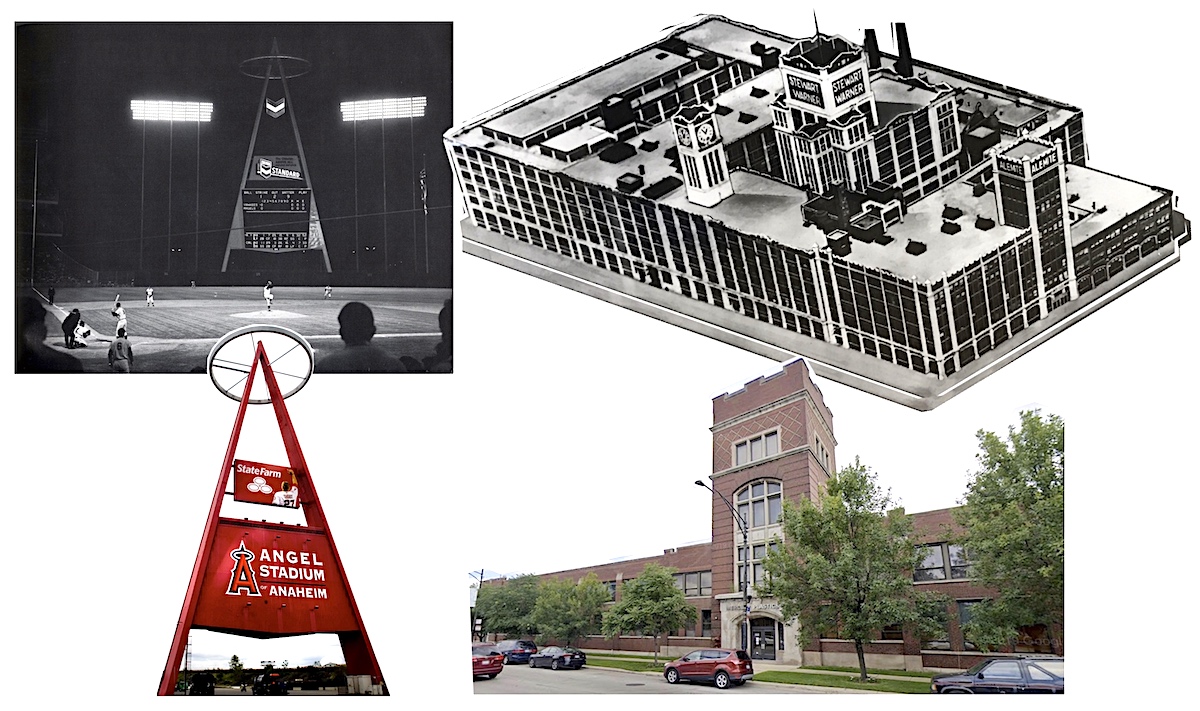

In the decades that followed, Stewart-Warner would solidify itself as an internationally known leader in accessories and instruments for all sorts of transport vehicles, including bicycle speedometers for the kiddos—as evidenced by the classic 1950s “Cadet” in our museum collection. As radios, televisions, refrigerators, and other home appliances were added to their arsenal, the company emerged as one of the largest employers in Chicago, particularly during and after World War II. The main Stewart-Warner plant at 1826 W. Diversey Parkway was a true marvel even in the heyday of the urban mega-factory, spanning six floors and over a million square feet, and employing upwards of 8,000 workers at its peak. Its eventual demise in the 1980s is a familiar tune, but the initial rise of Stewart-Warner remains a modern manufacturing epic.

[Left: Colorized photo of the Stewart-Warner plant on Diversey Parkway, 1930s. Right: 1954 ad for the Cadet bike speedometer]

History of the Stewart-Warner Corp, Part I: Mr. Warner and Mr. “Stewart”

John K. Stewart (b. 1869) and Arthur P. Warner (b. 1870) were two Gilded Age wunderkinds seemingly cut from the same cloth. Born months apart (Stewart in Nashua, New Hampshire, and Warner in Jacksonville, Florida), they each were the sons of factory workers, and learned about mechanical engineering through hands-on labor rather than in a classroom. Both men collected their first patents and started their own companies by the age of 21; both chose their best friends as business partners (Thomas J. Clark was Stewart’s cohort, while Arthur had his brother Charles Warner); both married their wives in 1897; both had two children; both had substantial fortunes by the age of 30; and both were passionate enthusiasts for the exciting new industry of motorized transport.

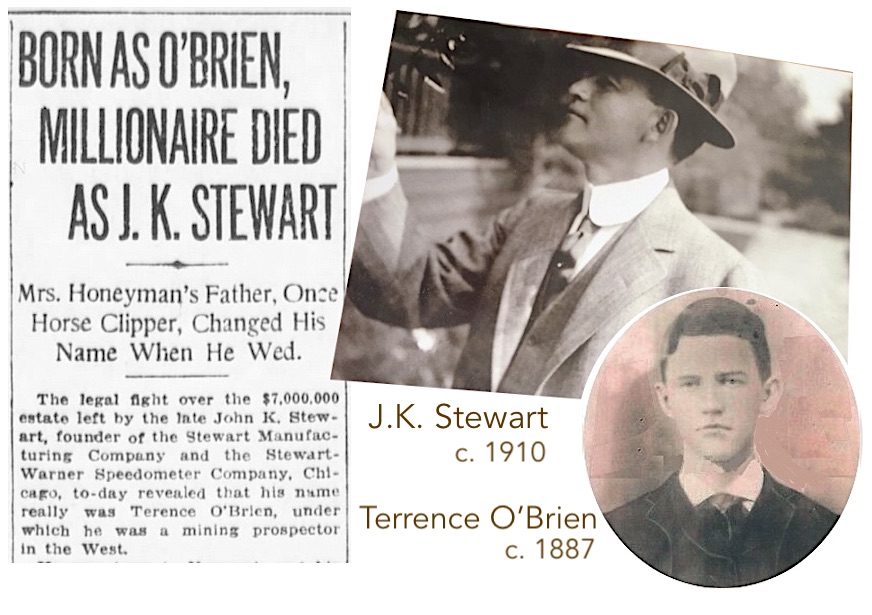

There were some diversions in the parallelism, however. Most notably, while Arthur Warner always maintained a strong connection to his family and adopted hometown of Beloit, Wisconsin, John Stewart kept his own past deeply shrouded in mystery. In fact, “John Stewart” wasn’t even his real name. As discussed in our history of his first business, the Chicago Flexible Shaft Co., Stewart was actually born Terrence O’Brien, and had spitefully left New Hampshire behind as a teenager after a falling out with his father. By the time he and his childhood pal Tom Conlon arrived in Chicago in the early 1890s, they had created new identities for themselves: “John K. Stewart” and “Thomas Jefferson Clark”; and they would be known solely by these names as their fame and fortune grew, with their families back in Nashua being none the wiser.

There were some diversions in the parallelism, however. Most notably, while Arthur Warner always maintained a strong connection to his family and adopted hometown of Beloit, Wisconsin, John Stewart kept his own past deeply shrouded in mystery. In fact, “John Stewart” wasn’t even his real name. As discussed in our history of his first business, the Chicago Flexible Shaft Co., Stewart was actually born Terrence O’Brien, and had spitefully left New Hampshire behind as a teenager after a falling out with his father. By the time he and his childhood pal Tom Conlon arrived in Chicago in the early 1890s, they had created new identities for themselves: “John K. Stewart” and “Thomas Jefferson Clark”; and they would be known solely by these names as their fame and fortune grew, with their families back in Nashua being none the wiser.

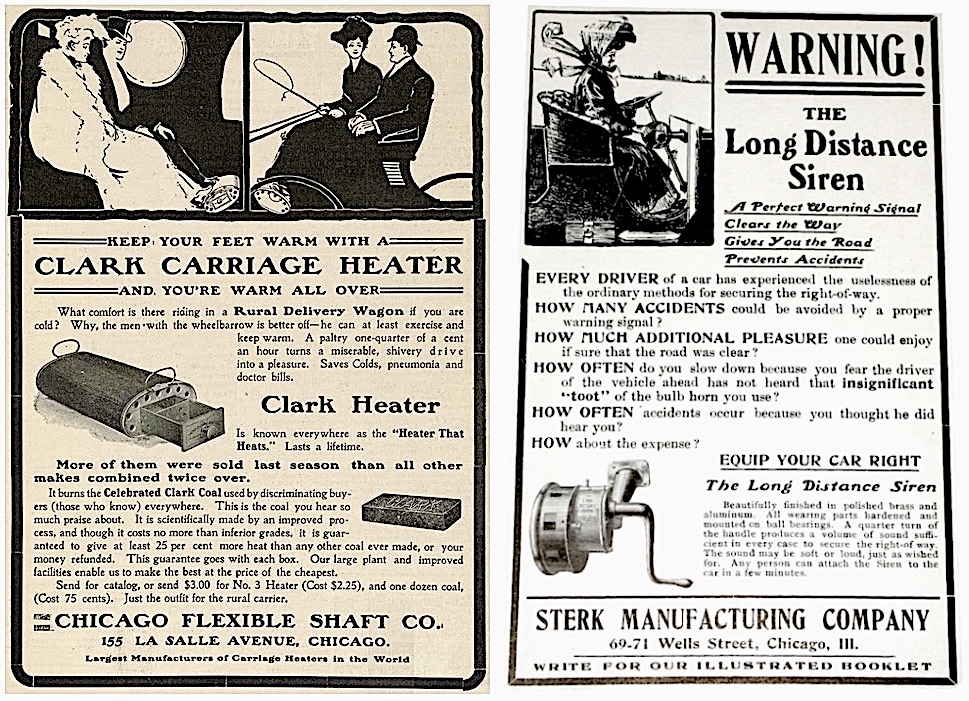

As noted, Stewart and Clark’s first successful venture was the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company (incorporated in 1897), which utilized a Stewart patent to create new, faster cutting tools for shearing sheep and clipping horses. As the 20th century began, though, the duo’s minds were increasingly preoccupied with horsepower rather than horses. In 1905, they formed the Stewart and Clark MFG Company (originally and briefly known as the STERK MFG CO.) to focus on the motor car, starting first with an early “long distance siren” design, shortly followed by a primitive speed gauge. These products were assembled in the new Stewart & Clark plant at 69-71 Wells Street, but using components largely made at the Chicago Flexible Shaft factory at Lasalle and Ontario Street.

[After finding success with the Clark Carriage Heater (left) in the first years of the 1900s, Chicago Flexible Shaft Company founders John Stewart and Thomas Clark expanded their car accessory business with their new venture as the Sterk MFG Co., later changed to the Stewart & Clark MFG Co. Pictured is a 1906 for one of Sterk’s first products, a Long Distance Siren, or car horn.]

With the streets of American cities turning into chaotic free-for-alls among inexperienced new motorists—darting amongst cable cars, horses, wagons, bicycles, and pedestrians—the need for functional car horns and accurate speedometers now seemed essential to establishing any sense of order and safety. Whoever cornered the market on this technology, it seemed, would clearly be in line for a substantial cash windfall.

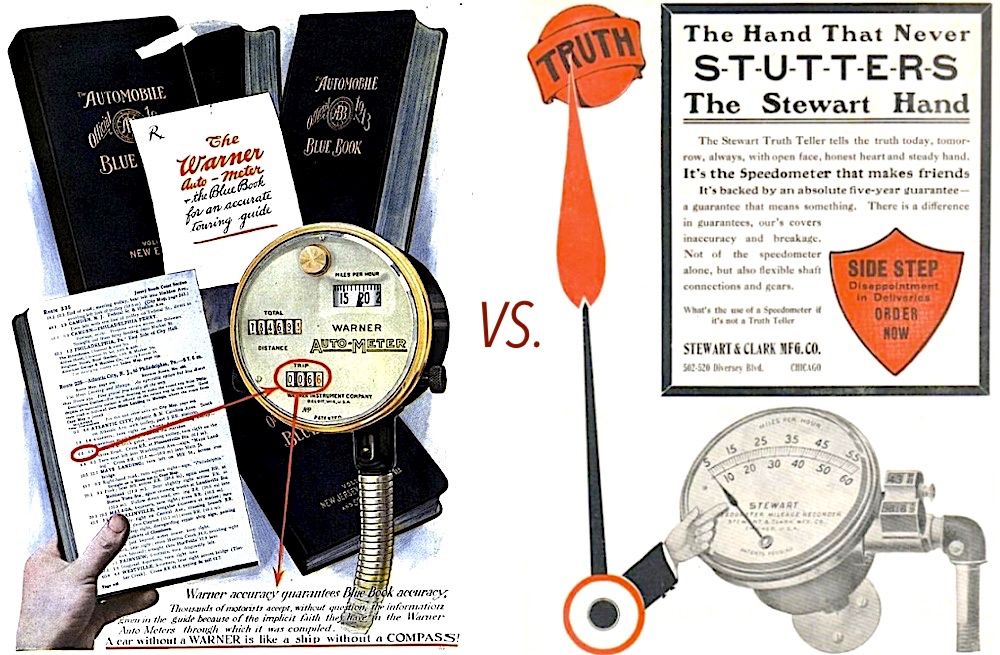

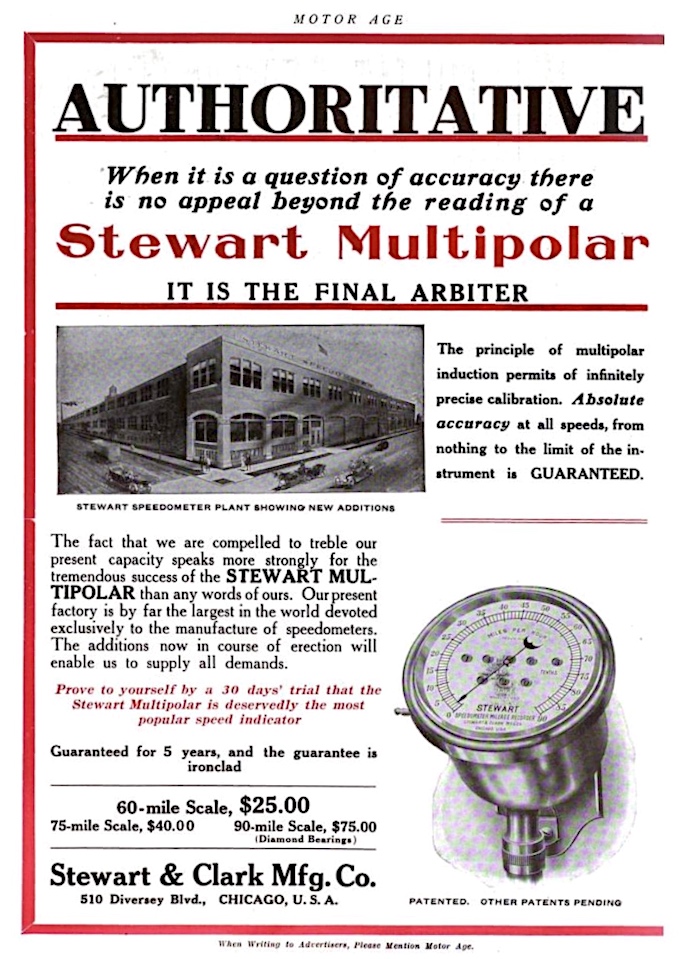

Stewart & Clark, utilizing the same flexible shaft patent they’d championed in barnyard tools, raced to the front in the Speedometer Wars, but they had a worthy foe up north in Wisconsin, in the form of the Warner Instrument Company, which Arthur Warner had launched with his brother Charles in 1904. The “Warner Auto-Meter,” a speed gauge they’d originally developed for measuring the movement of elevators and industrial equipment, operated on magnetic principles and was quickly adapted successfully for the motor car. Stewart & Clark soon came out with a comparable magnetic design of their own (arguably a total rip-off), and the rivalry was on.

[A 1912 ad for the Warner Auto Meter (left) and a 1907 ad for the Stewart Speedometer (right)]

II. The Speedometer Wars

In these days before radio and television, big promotional stunts and exhibitions were often the marketing strategy du jour, and the Stewart Speedometer and Warner Auto-Meter were both showcased across the country and beyond.

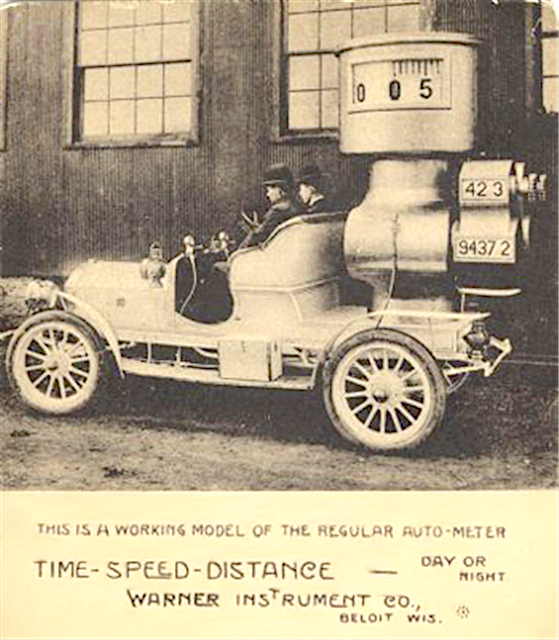

Arthur Warner, a showman as much as an inventor, took to these events like a duck to water. Around 1906, he built a giant-sized working model of the Auto-Meter—gold-plated, no less—and had it installed in a touring car for dramatic demonstrations. Driving around with his speed on ostentatious display, Warner got himself arrested in New York for driving 15 miles per hour—well above the 10mph limit of the time. Later, in Washington, D.C., President Teddy Roosevelt himself supposedly popped out from the White House to check out the Warner-mobile and its fancy instrument.

By 1909, Arthur Warner had also become the first American to purchase his own private aircraft and the first man to make a successful flight in Wisconsin. As such, he weaved aviation references and promotions into his marketing, and even produced a version of the Auto-Meter for flight use, known as the Aero-Meter.

By comparison, Stewart & Clark’s most memorable promotional event was one that ended in tragedy. In July of 1907, Thomas Clark agreed to showcase the Stewart Speedometer by driving in the Glidden Tour—a rally-style race organized by the American Automobile Association. During the event, on slick roads in Ohio, his Packard flipped over into a ditch and pinned him to the steering wheel. Clark died the next day. He was just 38 years old.

John K. Stewart was devastated by the loss, but seemingly more determined to do right by his old friend; by making their company an undeniable force in the automotive age. Stewart wasn’t the public figure that Warner was, but he knew how to build and distribute on a large scale and how to undercut the competition. Establishing a new building for Stewart & Clark at Diversey Blvd. and Wolcott Avenue, he pushed forward in a campaign to beat the Warner Instrument Company by essentially flooding the market.

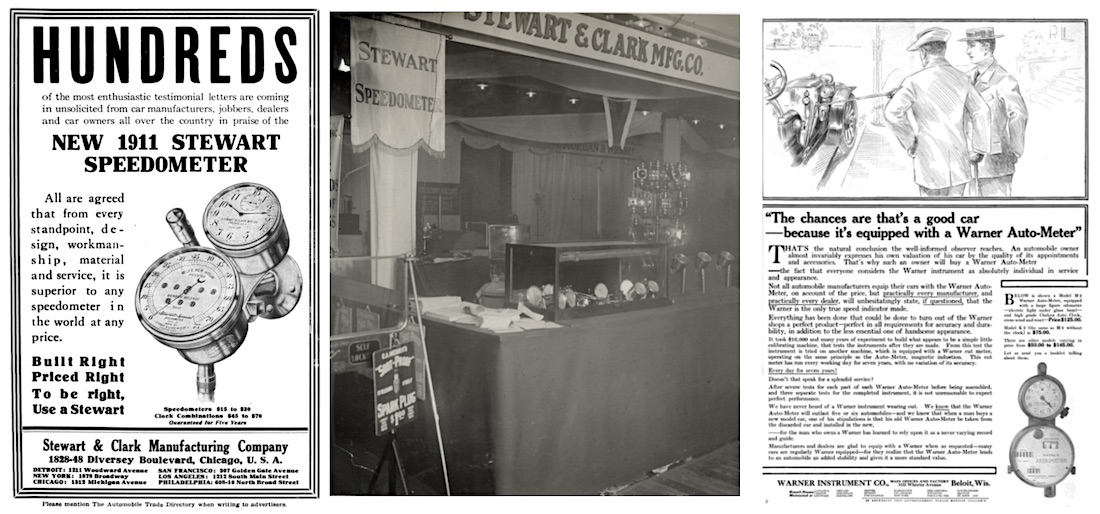

“The Stewart’s circulation is four times that of all other speedometers,” read a Stewart Speedometer advertisement in 1912. “It is the best made, most accurate, most dependable, most beautiful, and most popular.” Another ad offered a simpler message: “Built Right, Priced Right. To be right, use a Stewart.”

[Left: 1911 Stewart & Clark ad. Center: Stewart & Clark exhibit table from an industry convention, 1909. Right: 1911 Warner Instrument ad]

Outgunned in terms of sales numbers, Warner countered by presenting its speedometer as the high-end choice for the refined motorist. “The best speedometer is not necessarily the best, simply because its maker chose to call it that,” one ad claimed, clearing referring to Stewart. “On the contrary. The best is rather that speedometer which is chosen, preferred and insisted upon by the majority of automobile manufacturers who make the highest grade and highest priced cars, and the majority of those individuals who own the highest grade and highest priced cars.”

“Not all automobile manufacturers equip their cars with the Warner Auto-Meter, on account of the price,” read another 1911 ad, “but practically every manufacturer and practically every dealer will unhesitatingly state, if questioned, that the Warner is the only true speed indicator made.”

Stewart answered back in a 1912 ad, shooting down Warner’s premise that higher prices meant a better product. “Their higher price isn’t based upon superiority, but is necessitated by lack of demand. . . . If we had not organized our plant on an enormous scale—if we did not turn out so many speedometers—we would have to ask you double what we do.”

Stewart answered back in a 1912 ad, shooting down Warner’s premise that higher prices meant a better product. “Their higher price isn’t based upon superiority, but is necessitated by lack of demand. . . . If we had not organized our plant on an enormous scale—if we did not turn out so many speedometers—we would have to ask you double what we do.”

Ultimately, Arthur Warner had to concede at least one truth—the Stewart Speedometer was the best seller, by a long shot, and its use in the Ford Model T was basically the death knell for Warner’s hopes of becoming the industry standard. There was still the possibility of beating Stewart in the courts, thanks to several ongoing patent lawsuits, but that effort had become exhausting, as well.

“My brother and I had to spend all too much time over several years fighting the Stewart Company for our patent rights,” A. P. Warner later wrote in his memoir, Making Things. “We would no sooner get all the evidence before one judge than Stewart would find some way of starting all over with another judge, until the case had come up before six or eight judges.”

According to the memoir, when a judge finally did seem prepared to rule in Warner’s favor, John Stewart responded by offering to buy Warner out and merge their companies. “I had been away from home so much of the time, and was so tired,” Warner confessed, “that we decided to sell.”

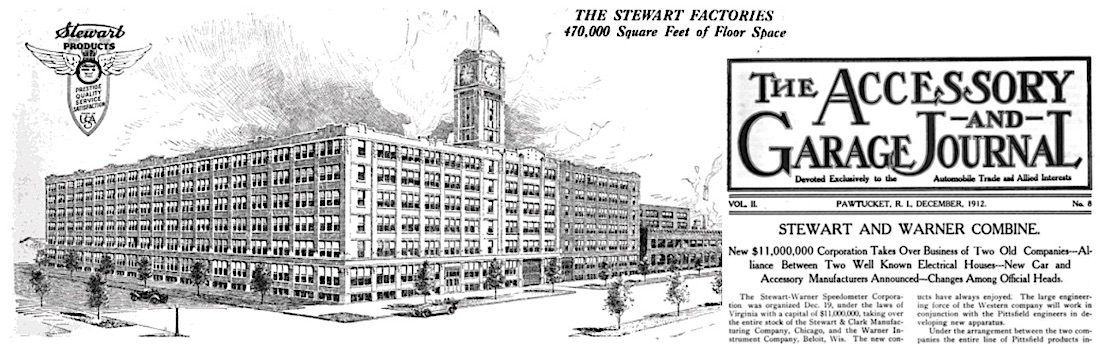

And so, in 1912, the Stewart-Warner Speedometer Corp. was born, a union of foes, headquartered at the growing Stewart plant on Diversey Blvd. in Chicago.

[Left: The Stewart-Warner complex on Diversey Parkway as it looked in the 1910s after the acquisition of the Warner Instrument Co. Right: 1912 headline in the Accessory & Garage Journal announcing the merger.]

Despite the name of the new merged company, Arthur Warner wasn’t involved in running the Stewart-Warner Corp. He went off and made further millions in real estate and copper mining, then invented the electric car brake, which he sold through a new business called the Warner Electric Brake & Clutch Company (est. 1927), which is still in business today as Warner Electric. Arthur Pratt Warner died in 1957 with over 100 patents to his credit.

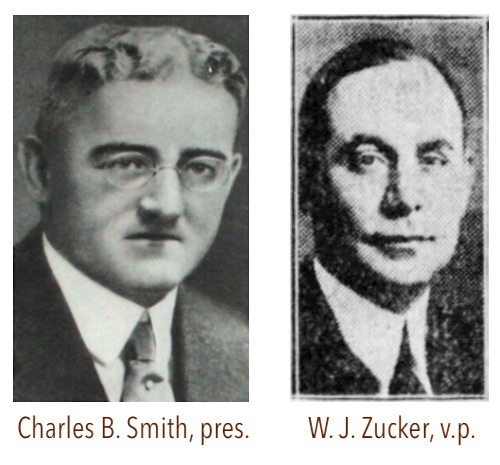

For John K. Stewart (who had over 80 patents himself), winning the Speedometer Wars proved to be one of his final great achievements. In 1916, at just 47 years of age, he died from a stroke at his New York City apartment. At the time, he’d already handed over most of the daily running of the Stewart-Warner Corp. to treasurer Charles B. Smith, and was focusing on new projects like the Stewart Phonograph Co., which was headquartered on Wells Street in Chicago. While he died a multi-millionaire, Stewart’s businesses only became bigger powerhouses in the decades after his death; not only Stewart-Warner, but the old Chicago Flexible Shaft Co., as well, which morphed into the kitchen appliance giant Sunbeam Corp.

In 1921, five years after Stewart’s death, legal matters concerning his estate finally led to the discovery of his earlier identity as Terrence O’Brien; a name which even Stewart’s own wife (who died shortly after him) and children don’t appear to have known.

In 1921, five years after Stewart’s death, legal matters concerning his estate finally led to the discovery of his earlier identity as Terrence O’Brien; a name which even Stewart’s own wife (who died shortly after him) and children don’t appear to have known.

“Recent revelations make the history of the Speedometer King’s life far more absorbing than had even been supposed,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that year, describing Stewart’s journey from working class runaway to auto parts magnate. “Eccentric millionaires are far from rare in this country, but the subject of this story hardly belongs in that category. He indulged in no spectacular extravagances; silver bathtubs were not in his line. Rather, as one of the country’s richest men, [Stewart] retained the picturesque qualities that had marked him when he was a fearless, roving, inquisitive, loyal, implacable adventurer. He did not forget his friends; neither did he forget those who had incurred his animosity.”

Just for the sake of historical accuracy, John K. Stewart may not have owned a silver bath tub, be did have a small fleet of custom-made yachts.

[1916 Stewart-Warner advertisement published in the Saturday Evening Post]

III. Stewart-Warner After Stewart and Warner

In the wake of John K. Stewart’s death, the Stewart-Warner Speedometer Corp. re-positioned its directors in 1916, with Charles B. Smith elected president, Winfred J. Zucker vice president and secretary, Leander H. LaChance CEO, and T. T. Sullivan treasurer. The Chicago factory employed 3,000 workers at the time, and the former Warner plant in Beloit was adapted into a gray iron and brass foundry, employing 400. On a much broader scale, Stewart-Warner had offices in a dozen other major cities from coast to coast, along with 60 exclusive stores they called “service stations,” specializing in S-W accessories—which now included tire pumps, vacuum gasoline feed systems, hand and motor horns, spark plugs, searchlights, bumpers, odometers, and more. The Stewart Speedometer, though, was still the company calling card.

“It is estimated that over 1,000,000 automobiles will be built during the coming year,” a Stewart-Warner ad read at the dawn of 1917. “That smashes to smithereens the great record of only last year—which was considered gigantic. But we are prepared. We have planned a production of 1,000,000 Stewart Speedometers. We doubled our factory to do it. We increased and enlarged our branches. We opened up additional service stations. We bought raw materials months ago. . . . Why did we do all this? Because we have the resources. We do 95% of the speedometer business of the country.”

[In 1919, Stewart-Warner promoted it’s “Big Ten” products as “Custom Built Necessities: They’re More Than Accessories.” The Big 10 included (1) Stewart Speedometer, (2) Warner Speedometer, (3) Stewart Truck Speedometer, (4) Stewart Motor-Driven Warning Signal, (5) Stewart Hand-Operated Warning Signal, (6) Stewart Vacuum System, (7) Stewart V-Ray Searchlight, (8) Stewart Spark Plug, (9) Stewart Autoguard, and (10) Stewart Hub Odometer. The expanded Chicago factory, designed by L. G. Hallberg, is pictured above in a 1918 photo.]

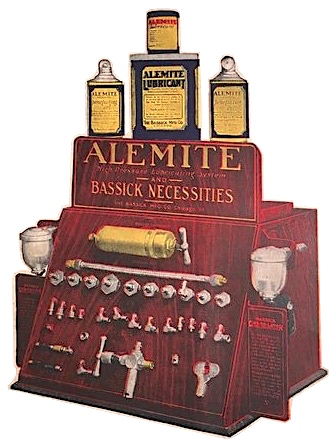

That near monopoly helped turn Stewart-Warner into an industrial behemoth, as the market value of its stock increased from $55,000 at the company’s 1912 merger to roughly $30 million a decade later. Over that same span, the company acquired several competitors in the auto parts field, including the V. Ray Spark Plug Co. and the Van Sicklen and Jones speedometer brands. The biggest addition came in 1924 with the purchase of the Bassick-Alemite Corporation, a leader in automobile lubrication systems (under the ALEMITE and ZERK brands) and hardware (Bassick MFG).

When the smoke cleared on that handshake, the re-named Stewart-Warner Corporation now had two massive Chicago plants—17-acre and 9-acre respectively—along with facilities in Elgin, IL, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Canada. The businesses under its umbrella, which also included the prolific Stewart Die Casting Corp., were credited in 1929 with manufacturing “80 percent of all furniture hardware made in the United States; half the casters used throughout the world; and hardware equipment for 98 percent of the American automobiles, excluding Fords.”

When the smoke cleared on that handshake, the re-named Stewart-Warner Corporation now had two massive Chicago plants—17-acre and 9-acre respectively—along with facilities in Elgin, IL, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Canada. The businesses under its umbrella, which also included the prolific Stewart Die Casting Corp., were credited in 1929 with manufacturing “80 percent of all furniture hardware made in the United States; half the casters used throughout the world; and hardware equipment for 98 percent of the American automobiles, excluding Fords.”

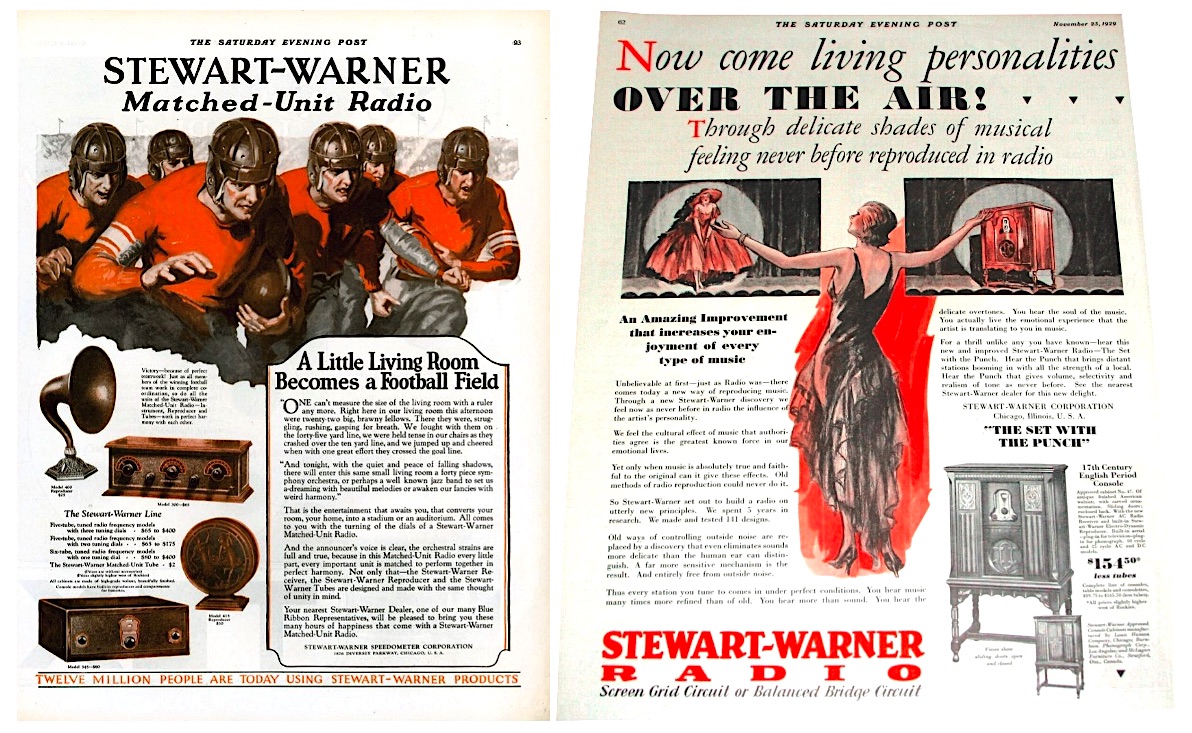

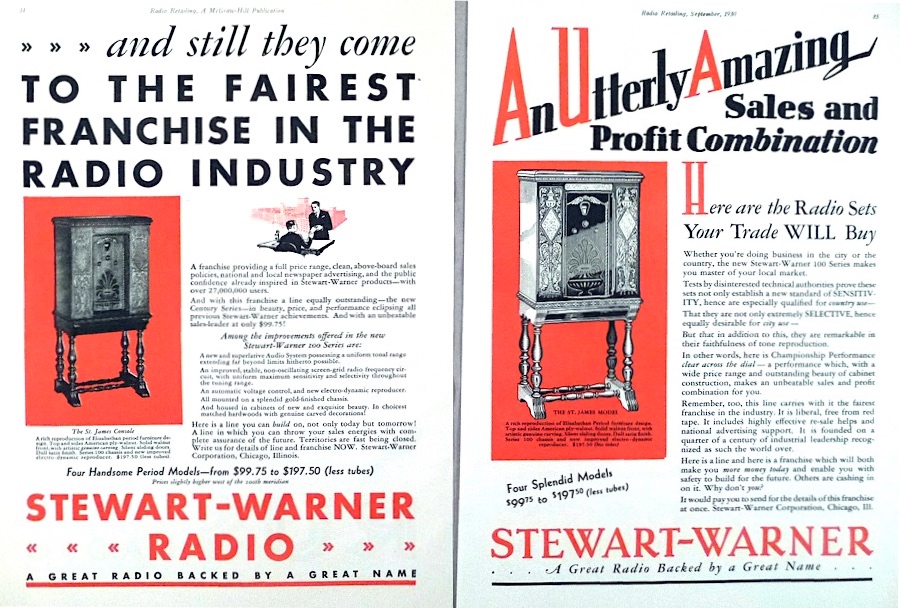

And yet, even with those claims to fame, Stewart-Warner spent much of the late 1920s promoting a very different venture; one that likely would have pleased its late founder. John K. Stewart was a music lover and audiophile who was just getting into the phonograph business before his death; had he lived a few years longer, his attention almost surely would have moved to the radio, and as it happened, his company jumped headfirst into the new wireless age anyway.

“Quite naturally the manufacturing experience through the years has been helpful to us in making radio receivers,” Stewart-Warner vice president Winfred J. Zucker said in 1929. “Methods and policies that were responsible for the success of the Stewart-Warner speedometer and our other lines of diversified products have been followed by our radio engineers.”

Stewart-Warner’s early “Matched Unit” and “Magic Dial” radio receivers were heavily promoted and well received, pun intended, with heavily ornamented wood console cabinets gradually giving way to smaller, more streamlined desktop designs.

“For a thrill unlike any you have known—hear this new and improved Stewart-Warner radio—the Set with the Punch!” read a 1929 magazine ad. “Hear the Punch that brings distant stations booming in with all the strength of the local. Hear the Punch that gives volume, selectivity and realism of tone as never before.”

The Stewart-Warner team was well ahead of the curve on television, as well, becoming the first major manufacturer to equip its radio assemblies with TV connections, in anticipation of a technology not yet available. “It probably won’t be so long before we can sit at our fireside and see and hear events that are taking place many miles away,” Zucker said when promoting the new 900 Series radios in 1929. “. . . If television broadcasting arrives on a big scale, one year or five years hence, these receivers will be modern and available for that type of broadcasting.”

For all their foresight, though, the executives at Stewart-Warner didn’t anticipate their own overconfidence coming back to bite them. Throughout the roaring ‘20s, as they absorbed rivals and diversified their product lines, the “old guard” of the company—led by Charles Smith (b. 1873), Zucker (b. 1879), Leander LaChance (b. 1874), and Vail R. Bucklin (b. 1877)—began enriching themselves with salary raises and bonuses, while increasingly alienating and exploiting the “outside” managers and engineers they’d conquered.

Charles Smith, according to a memoir written by his own son-in-law Bill Holmen, “ruled the company as an autocrat.” Ironically, though, the thing that may have most antagonized his stockholders was his surprising willingness to negotiate fairly with organized labor—the less powerful life blood of the business. As the son of Irish immigrants and a self-made man, Smith “had extraordinary sympathy for labor causes,” Holmen wrote, adding that Stewart-Warner was among the first large automotive plants in Chicago to be unionized. “[Smith] was well aware of the enmity caused by championing the rights of labor, but felt there were moral values to be upheld.”

By 1933, after several years of multi-million dollar net losses at the outset of the Depression, an all-out revolt broke out at the top of Stewart-Warner, led by two of the key figures of the company’s Alemite division. One was the young general manager of Alemite, Joseph E. Otis, Jr. (b. 1892), and the other was the prolific and eccentric Austrian engineer Oscar Zerk (b.1878), whose invention of the famed Zerk grease fitting in 1929 had become a massive money-maker for Alemite and S-W.

Zerk, who was also the fourth largest shareholder in Stewart-Warner, “had no intention of watching his investments depreciate without a murmur,” according to a 1934 piece in Time magazine. “Last spring Mr. Zerk launched a ferocious proxy campaign to oust the management [at Stewart-Warner], charging them with pocketing unconscionable fat bonuses, with gross inefficiency and a general lack of business acumen.”

Zerk’s rebellion was largely successful, as a new board of directors was elected in 1933, which soon uncovered evidence to support Zerk’s accusations against the S-W officers. Smith, Zucker, LaChance and Bucklin—most of whom had been with the company from its earliest days— were all kicked to the curb and sued for recovery of misspent funds. Charles Smith, who had already lost much of his personal fortune after the stock market crash, was “most hurt and embittered that men in Stewart Warner whom he had brought to power, and whom he regarded as friends, would undermine and turn on him in the crunch.” Joseph Otis, a Yale grad, was elected the new company president, and James S. Knowlson—a Cornell grad and former president of the Speedway MFG Co.—was elected chairman of the board.

[Left: 1933 ad for a Stewart-Warner Movie Camera. Top: The new S-W leadership after Zerk’s 1933 rebellion. Bottom Center: Inventor and S-W stakeholder Oscar Zerk. Bottom Right: A Stewart Warner Service Station in Seattle, WA, 1937]

The new leadership at S-W ushered in big changes to avoid any further pull into the Depression’s undertow. “Unprofitable lines including cinema equipment were dropped,” Time reported, referring to the company’s short-lived production of home movie cameras. “Alemite’s operations were consolidated with the Stewart-Warner Chicago plant. Superfluous subsidiaries were dissolved. A new accounting system was installed and assets were written down. Stewart-Warner reported a $1,791,000 loss for 1933 but in February [1934] sales were running 150% ahead of last year.”

By 1937, when chairman J. S. Knowlson spoke at a Stewart-Warner 25th anniversary event, the company had managed its best financial year since 1929, allowing it to bring back much of its laid off personnel while also introducing some new products, including a line of refrigerators.

[1938 Stewart Warner “Sav-A-Step” Refrigerator Sales Film]

“Unknown symptoms of serious illness become acute when they are described vividly,” Knowlson said, referring to people who remained pessimistic about an economic recovery, “and both businesses and boys mope with supposed maladies when actually enjoying robust health.”

From Knowlson’s standpoint, a fruitful industrial sector still depended on what it always had—great ideas. “The rapidity with which new products have appeared in the advertising pages, in our industries and in our homes has been exceeded only by the speed with which new men have taken their place in managements, the laboratories and on the boards of successful companies,” he said. “There is scarcely a man in any group such as this who does not in his own person attest the truth that in this age the doors of opportunity have been open, and that it has been a period characterized by alertness to new products and an equally ready appreciation of new abilities.”

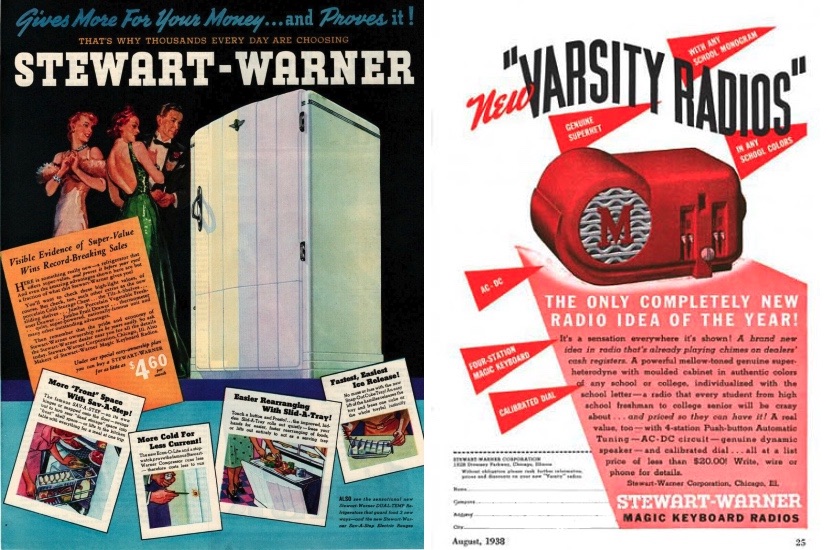

[Advertisements for the Stewart-Warner refrigerator (1939) and Varsity Radio (1938)]

IV. Stewart-Warner in Wartime

After Joseph Otis left to become president of the Dodge Corporation in 1939, James S. Knowlson became both the chairman and president of Stewart-Warner. Shortly thereafter, his responsibilities would go well beyond selling radios, fridges and speedometers.

Starting in 1940, well before Pearl Harbor, Stewart-Warner’s Chicago plant was already taking on military contracts to aid the Allies, with 14% of the factory’s volume given over to making artillery fuses by the spring of 1941. While many business owners felt increasing anxiety about America’s halfway in / halfway out involvement in the war overseas, Knowlson seemed quite practical in his approach.

“Any one with a soap box and a good pair of lungs can predict what we in this country are going to do,” he said, “and any one who hears these predictions can shrug his shoulders at another piece of bombast. Talk can be laughed off—but production can’t be laughed off.”

“Any one with a soap box and a good pair of lungs can predict what we in this country are going to do,” he said, “and any one who hears these predictions can shrug his shoulders at another piece of bombast. Talk can be laughed off—but production can’t be laughed off.”

Less than a month after the U.S. finally declared war, Knowlson was posted to an important position on the War Production Board, as “head of the division of industrial operations,” and he unsurprisingly converted most of the Stewart-Warner fleet of factories into defense plants. The Diversey headquarters, known as “Division One,” went on a 24/7 schedule, producing shell fuzes, radio and communication equipment, various instruments, and the Alemite lubricating equipment essential to just about all military vehicles. Some of this gear would be used on the battlefield by Stewart-Warner employees, 400 of whom joined the armed forces in that first year.

In something of a patriotic fluff piece, a Tribune reporter visited the Diversey factory in 1942, just ahead of July 4th, to talk with employees who were more than happy to forgo their holiday to punch in at the plant.

Hugo Bernahl, a welder, pushed his mask above his head to speak to the reporter. “For Uncle Sam, we’ll do anything to keep ‘em flying,” he said. “And if they need more, we’ll work faster.”

Catherine Hughes, a spot welder, agreed. “Working on the Fourth is okay if it’s for the good of the men in service.”

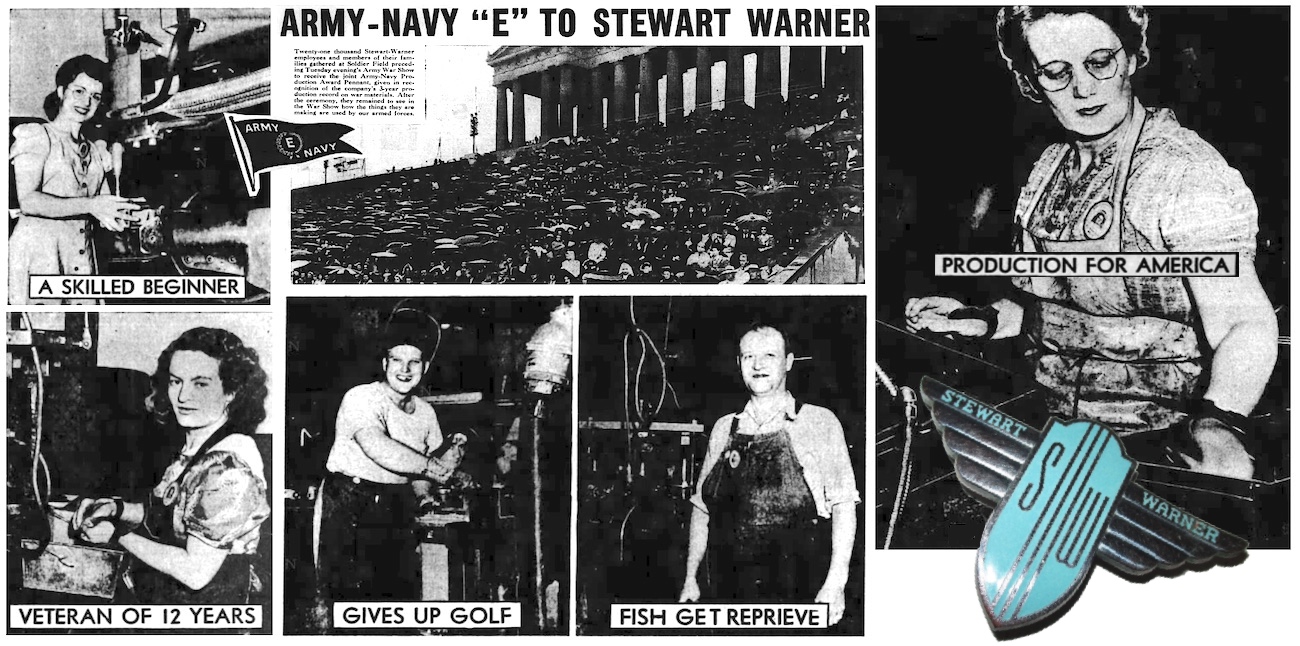

[Stewart-Warner’s Chicago factory workers during WWII. Top Left: Rose Podlesak, welder. Top Center: Over 20,000 S-W workers and family members gathered at Soldier Field for presentation of the factory’s Army-Navy “E” Award. Top Right: Eve Crawford, punch press operator. Bottom Row (from left): Nell Harvey (punch press operator), Hugo Bernahl (welder), and Henry Groh (die machinist). From Chicago Tribune.]

Twenty-nine year-old punch press operator Nell Harvey, who started with Stewart-Warner when she was 17, said she planned to celebrate after her shift was over, and Rose Podlesak, a newcomer to factory work, didn’t mind coming in on the Fourth, since her husband worked for Stewart-Warner, too, and would be doing the same. All around these dedicated employees, patriotic signs hung from the walls, urging them on. One said “MacArthur is giving his all, are you?” “Accidents Help the Axis,” read another.

By the summer of 1945, Division One had received four Army-Navy “E” awards for excellence in war production, and there were five more awarded to other Stewart-Warner facilities, including three for a plant in Indianapolis and two for the Green River Ordnance plant in Dixon, IL.

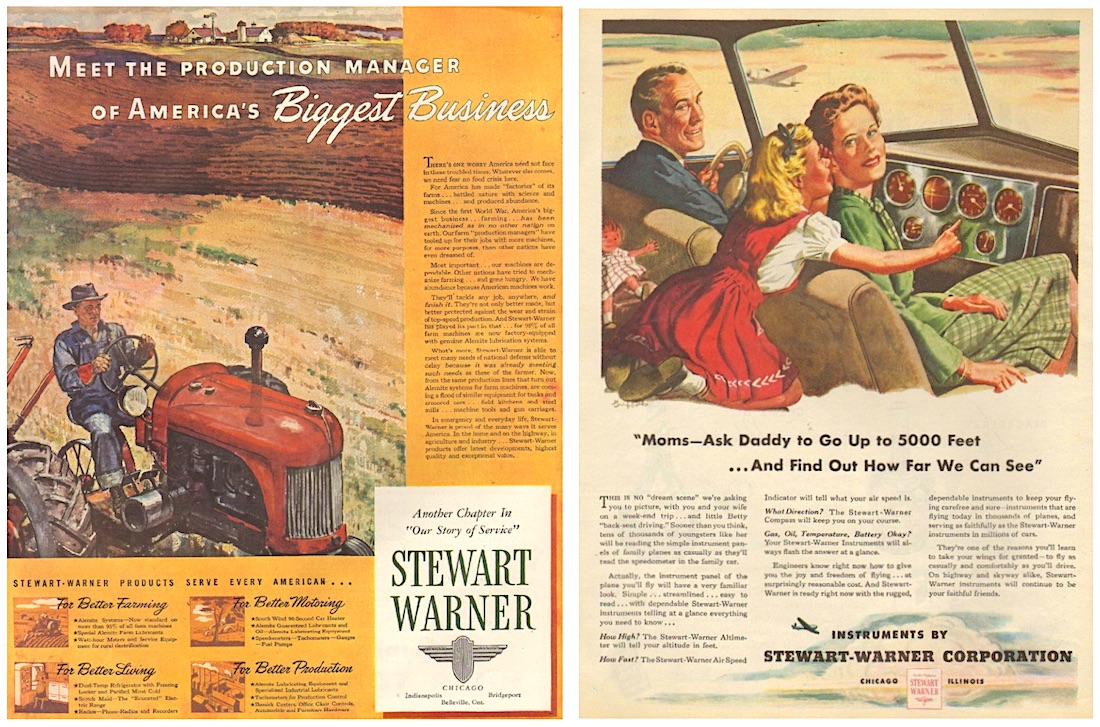

While focused on “the cause,” the company wasn’t necessarily keeping a low profile during the war. The marketing department was already crafting the new image of Stewart-Warner for a hopeful post-war world, buying colorful ad space in the Saturday Evening Post and other mainstream magazines, proclaiming that “Stewart-Warner Products Serve Every American.” This concept was grouped into four categories; products for Better Living (radios, refrigerators, electric stoves), Better Motoring (speedometers, fuel pumps, car heaters, and lubricants), Better Farming (Alemite lubricating systems were now used on “95% of all farm machines), and Better Production (Alemite for industrial machines, Bassick casters and furniture hardware). At the same time, S-W could also promote its patriotic performance, building on its already solid reputation with the American public.

“In emergency. and everyday life, Stewart-Warner is proud of the many ways it serves America,” read a 1944 ad. “In the home and on the highway, in agriculture and industry. . . . Stewart-Warner is able to meet many needs of national defense without delay because it was already meeting such needs as these of the farmer. Now, from the same production lines that turn out Alemite systems for farm machines are coming a flood of similar equipment for tanks and armored cars . . . field kitchens and steel mills . . . machine tools and gun carriages.”

[Two Stewart-Warner advertisements from 1944]

Other wartime advertising focused more on almost delusional levels of post-war optimism, including a series depicting a suburban family flying their own private plane equipped with a Stewart-Warner instrument panel.

“This is no ‘dream scene’ we’re asking you to picture, with you and your wife on a weekend trip and little Betty ‘back-seat driving.’ Sooner than you think, tens of thousands of youngsters like her will be reading the simple instrument panels of family planes as casually as they’ll read the speedometer in the family car.”

Well, the “family plane” was not forthcoming for the middle class, but once the war ended, Stewart-Warner did come to represent a certain tangible brand of “high-tech,” whether in the form of the bicycle speedometers they promoted in children’s magazines, or the new television sets that helped raise those same kids.

J. S. Knowlson—whose work for the War Production Board earned him the Medal of Merit—was now one of Chicago’s most illustrious industrialists, described by his cohorts in a 1953 Tribune feature as a “salty character who puts up a gruff exterior but who actually is as kindly as they come. However, he does look at things that come before him with a cool and efficient eye.

“. . . Since Knowlson became associated with Stewart-Warner its success record is a matter of history. It has broadened its activities so that it no longer can be considered as mainly an automobile accessory manufacturing company. . . . It has about 10,500 employees. Sales last year were about 120 million dollars. One of Knowlson’s major problems today is that of getting together a staff of men from whom to select his successor when that becomes necessary.”

V. Record Profits, Failing Factories

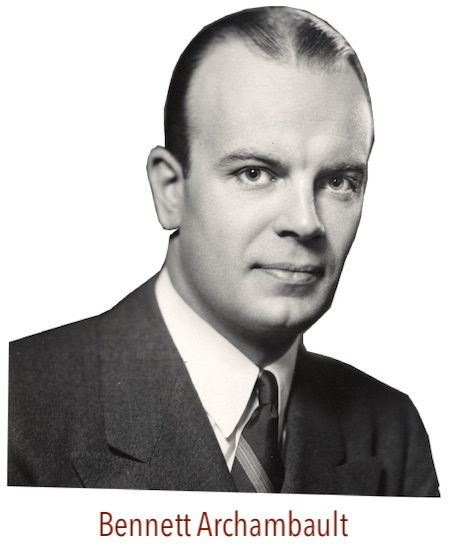

In 1954, a 44 year-old MIT grad named Bennett Archambault was elevated to president and CEO of Stewart-Warner. Like Knowlson, he’d been awarded a Medal of Merit for his work during WWII, when he ran the European operations of FDR’s Office of Scientific Research and Development.

A staunch Republican, Episopalian, and anti-Communist, Archambault was very much a business leader of his time—noble in principle, but not necessarily progressive or enthusiastic when it came to worker empowerment. No one could deny his success when it came to the bottom line, however. After Jim Knowlson died in 1959 at the age of 75, Archambault took over both the presidency and the chairmanship, and by the end of that year, Stewart-Warner was posting its highest earnings in company history—with particular gains for its heating and cooling products, including the South Wind and Winkler lines, largely built in Indiana.

It was around these last days of the 1950s—caught between “Ozzie and Harriet” and Elvis, Sputnik and McCarthyism—that the Cadet speedometer in our museum collection was made . . . and likely sold to a young Schwinn owner who saw the ad in Boy’s Life.

[Cadet Speedometer ad from the late 1950s and the Cadet from our own museum collection]

In 1962, Stewart-Warner marked its 50th anniversary in the same location they’d started on Diversey Parkway, albeit in a grand terra cotta industrial estate that John K. Stewart wouldn’t have recognized.

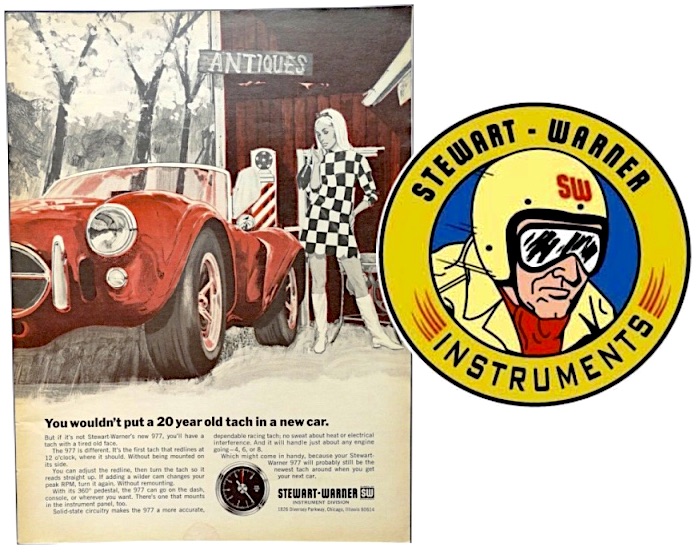

The firm still employed over 8,000 people across its various facilities and subsidiaries, with about 3,000 at the Diversey HQ. The Stewart Die Casting division at 4535 W. Fullerton Ave. had another 1,000 employees, and the Electronics division at 1300 N. Kostner Ave. had 1,000 more. Stewart-Warner televisions had never really caught on, and had been discontinued in the ’50s, with radios soon to follow. But there were other, more unusual new electronics ventures, including scoreboards for major sports venues. Starting in 1966, S-W designed, built, and installed these units at dozens of famous ballparks, including Fenway Park in Boston, Tiger Stadium in Detroit, Giants Stadium in New Jersey, and Memorial Stadium in Los Angeles. One of their first scoreboard projects also remains their most iconic: the “Big A” at Angel Stadium in Anaheim, CA.

[Left: Then and Now of the “Big A” scoreboard in Anaheim, California, built by Stewart-Warner in the mid 1960s. Top Right: The main Chicago plant on Diversey as it looked from above in the ’60s. Bottom Right: 4535 West Fullerton Ave., former home of Stewart-Warner’s Die Casting division from 1917 to the 1980s. The building is now the home of Mercury Plastics.]

Whether putting together speedometers or scoreboards, most of the men and women in Stewart Warner’s employ had to feel fairly secure in their jobs, as the company continued to hit new sales peaks year after year throughout the decade of the ‘60s and well into the 1970s, largely bucking the trends of decline affecting many of its U.S. competitors. By 1980, the company owned 14 U.S. plants (five in the Chicago area) and four foreign plants, but the cracks caused by keeping so many plates spinning, for so long, were finally starting to show.

In 1981, there was a major labor strike at the Diversey plant—the first to occur after 38 years of collective bargaining. Interviewed at the time, employee Verna Scott, an 11-year vet of the company, laid out the rationale for the strike: “The troubles with discrimination, low pay, and poor benefits have built up over a long time,” she said. Scott’s boss, Bennett Archambault, now 71 years old, scoffed at this notion. “The strike should not have occurred,” he told the Tribune. “We believe that unrealistic expectations were created as a result of the intense competition among unions.”

In 1981, there was a major labor strike at the Diversey plant—the first to occur after 38 years of collective bargaining. Interviewed at the time, employee Verna Scott, an 11-year vet of the company, laid out the rationale for the strike: “The troubles with discrimination, low pay, and poor benefits have built up over a long time,” she said. Scott’s boss, Bennett Archambault, now 71 years old, scoffed at this notion. “The strike should not have occurred,” he told the Tribune. “We believe that unrealistic expectations were created as a result of the intense competition among unions.”

Neil Burke, who was the business manager for the United Workers Association-United Electrical Workers (UWA-UE), acknowledged that shake-ups among the labor groups had played a role in ending the long peace at Stewart-Warner, but simplifying the strike down to that was overlooking some harsh truths. “The company underestimated the needs of the workers and the unity and strength of the members,” he said.

“The strike will have a significant impact on our first quarter results,” Archambault bemoaned.

Four years later, some of the Alemite Division’s production was moved from the Diversey plant to a facility in Tennessee; and some of the Electronics division was contracted out to a plant in Mexico. These developments, combined with slowing sales and deteriorating machinery in the Diversey plant, were creating a dark cloud over Stewart-Warner’s future in Chicago.

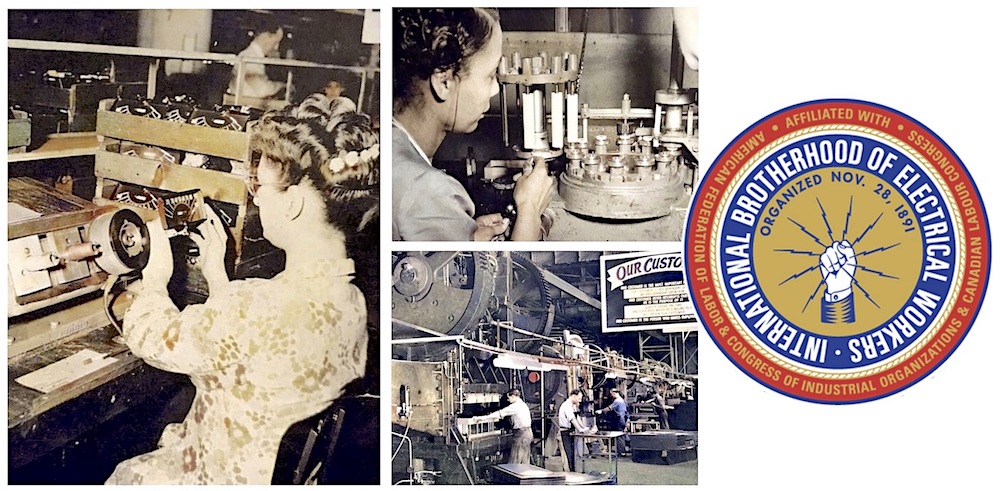

[In 1979, after 30 years of association with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), Stewart-Warner’s Chicago workers formed an independent union, the United Workers Association, which led to feuds with the old union and the bosses at S-W, leading to a strike in 1981.]

“You could see it coming; no one was really surprised,” 20-year employee Shirley Williams told the Chicago Reader at the time. “They weren’t fixing machines; they were laying people off. We kept saying, if you fix the plant up, if you modernize technology, we can increase sales, and nobody would have to lose their job. But no one seemed to be listening.”

“They’re falling to pieces,” machine operator Bob Pitera told the Tribune in 1987, referring to the outdated, rundown equipment. “It’s like running the Indianapolis 500 with a 1959 Chevy. You may get around the track, but that’s it.”

Like the factories themselves, Stewart-Warner’s products were beginning to fall behind new trends in technology, as the old dials and gauges of the past were clearly not going to remain the norm on the dashboard displays of the computer age.

In the face of these downward trends, local Chicago groups were organized in the late ’80s to try to save the business, led by the Coalition to Keep Stewart-Warner Open. Even after Bennett Archambault announced the sale of the company to British Tyre & Rubber (BTR) in 1987, there remained hope that the new foreign ownership might choose to invest in the once mighty Chicago factory and revive its machinery and R&D departments. But it wasn’t to be.

In 1989, the final remaining 700 S-W employees left in Chicago got word that BTR would be closing all Chicago operations and moving to Juarez, Mexico. Adding disaster to disappointment, any hopes of giving the Diversey plant a well deserved revival fell by the wayside, as well, as the building was largely gutted by a massive fire in 1993 and demolished a year later.

Through various hand-offs among corporate overlords since, the Stewart-Warner brand name lives on, currently in the portfolio of a Wisconsin based company called CentroMotion.

[Exclusive photos of the elusive John K. Stewart, as provided to the Made In Chicago Museum by Stewart’s great grandson R. Stewart Honeyman, Jr. The top left image shows Stewart and his wife Julia christening a ship. The image on the right is Stewart holding his baby daughter Marian, circa 1901.]

Sources:

“Stewart and Warner Combine” – Accessory & Garage Journal, Dec 1912

John K. Stewart obit – Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 3, 1916

“Arthur Pratt Warner” – Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame

“New Officers for Stewart-Warner” – Chicago Tribune, June 15, 1916

“Stewart-Warner Speedometer Corporation” – Poor’s Manual of Industrials, 1922

“Two Men and a Horn” – Automobile Trade Journal, Dec 1, 1924

“Stewart-Warner-Bassick-Alemite Combine Releases Loading Organization” – Automotive Industries, Nov 27, 1924

“What’s Behind Your Stock: Stewart Warner Speedometer Corp” – News-Herald (Franklin, PA), Oct 12, 1925

“Television in the Movies Soon, W. J. Zucker Thinks” – The Journal (Meriden, CT), May 1, 1929

“Huge Factory is Turning Out Fine Receivers” – Oakland Tribune, September 20, 1929

“New Cabinets for Radio are Work of Art” – Star Tribune (Minneapolis), Sept 26, 1929

“Stewart-Warner President Quits” – Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, PA), July 25, 1933

“Sue Stewart-Warner Former Heads on Bonus” – Chicago Tribune, March 4, 1934

“Business: Stewart-Warner-Alemite” – Time, March 19, 1934

“C. of C. Terms ’37 Industry Gain Biggest” – Indianapolis Star, Dec 21, 1937

“J. E. Otis Jr. to Quit as Stewart-Warner Head, Joins Dodge MFG” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 4, 1939

“Stewart-Warner’s Chairman Also to Serve as President” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 17, 1939

“Stewart-Warner Ends First Year of Military Production” – Chicago Tribune, May 24, 1941

“W-O-R-K Spells Fourth of July at Arms Plant” – Chicago Tribune, June 28, 1942

“Production Awards” – Motor Boating, June 1945

“The Road to Success: A Sketch of James S. Knowlson, Head of Stewart-Warner,” Chicago Tribune, Feb 14, 1953

Making Things, by Arthur Pratt Warner, 1955

“Archambault Chairman of Stewart-Warner Firm” – Great Falls Tribune (Montana), March 30, 1959

“1959 Stewart Net Up 53 PCT. to a New High” – Chicago Tribune, March 14, 1960

“No Quick Solution to Stewart Strike” – Chicago Tribune, March 18, 1981

“Rundown and Out?” – Chicago Tribune, May 17, 1987

“Calling London: Can Stewart-Warner’s New Owners be Persuaded to Save This Plant?” – Chicago Reader, May 12, 1988

Our Archipelago, by Bill Holmen, a memoir and family history, with excerpts on Charles B. Smith provided by David Martin

Archived Reader Comments:

“Well I just saw a great commercial for their refrigerator with Art Carney (age 18) doing an impression of FDR!” —Cassandra Johnson, 2019

My Grand Father worked there for over 40 years. My parents both worked there, met and married. I grew by 4 blocks from that factory. If it didn’t go, I would have worked there. Memories.

I have a 120 volt alarm clock with Chicago Flexable Shaft Co. engraved on the metal case with Patent applied for engraved as well. The face of the clock has Sunbeam printed on it. Do you have any information on this clock? It is neat old clock.

employee Shirley stephens looking to find her

I have a Stewart Warner kitchen stove/range 1940/41 I can not find info on. It is in good shape & still works. It has a partial paper sticker on back that I was able to figure out year from. I looked up on line when I got it & found an advertisement sheet on I believe ebay. To my disappointment, I did not purchase.

Is there any information on these?

I have a rpm tach and odometer steward warner cage it also had the steering wheel mont the # is 100178 like to know the age and it’s worth and a little history on what is was used on. Thank yo

I have a stewart warner model 329738 engine balancer. How much was it new? What would it be worth today?

We lived exactly 8 doors west of the Diversey plant at 1918 Wolfram St. That giant clock served as the family’s kitchen timepiece for years as we looked out the kitchen window at it. We never saw the morning sun rise though, living in the shadow of the giant building.

i have a cook stove, model 8019. looks like it made in 30s or early 40s, can’t find much info on it..

My grandfather worked at the Chicago plant as the Elevator Man for numerous years. Mr. Smyles

My father worked at the Chicago plant on Diversy Ave in the 70s as a stationary engineer. His name was Rudolph Walters. I remember going with him to pick up his paycheck every week.

I have the first Stewart-Warner T-25895 speedometer calibrating machine. I would like to know if you would be interested in it ?

I can send pictures and specs.

Calibrating machine

All speedometers

S.I 120 page 2

January 30 1928

Supersedes T-12

Page 1to 9

Above. Page service instructions.

I was in the speedometer repair business since early 1960’s

Hello

Do you steel have a Stewart-Warner T-25895 speedometer calibrating machine ?

I have Stewart Warner hand held tach model 757-w in original can tach never been used is it worth anything to your company 361 453-5454 thank you

I WAS THE TALENT SCOUT RECRUITER OF THE PESONNEL DEPT…..IN THE EARLY TO MID 70’S……..salaried employment………best years of my life even though it was the corporate version of viet nam daily warfare. my claim to fame was my naming the diversey ops….THE NEAR NORTH CASTLE…….for our many ads in the chicago tribute and sun times along with the local papers…….the employees were the best,,,,,those were the days my friend……..oh yes those were the days.

I have a small hand grease gun I think model number 6562 Patton 14759801676626 Manufactured by Stewart Warner Corp a LEM ITE made in Chicago USA I’d send you a picture but I don’t know how to do that on this website my phone number is area code 5138048750 and I would like to hear from somebody if you could tell me what this is thank you