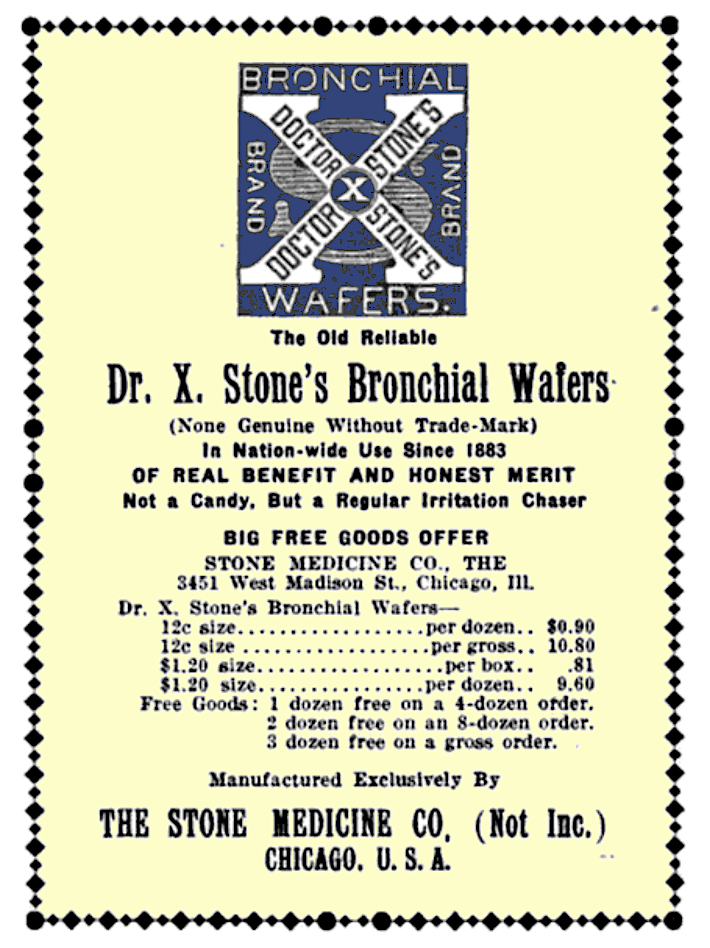

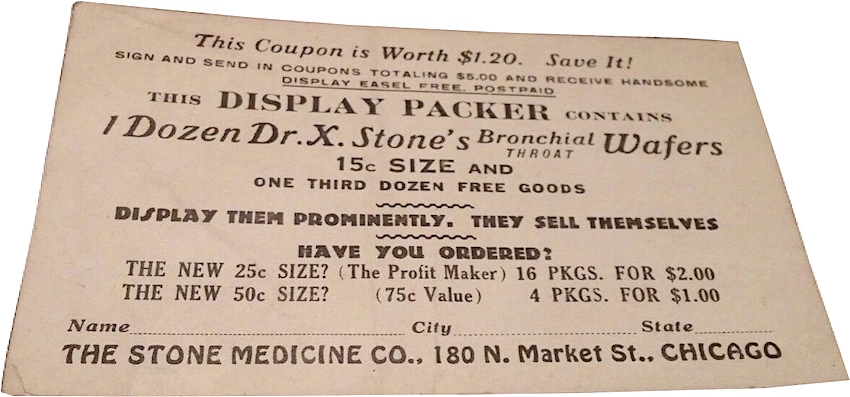

Museum Artifact: Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Throat Wafers, c. 1920s

Made By: The Stone Medicine Co., 3451 W. Madison St., Chicago, IL [Garfield Park]

There’s likely not a soul alive who can still speak to the product’s effectiveness, but for over 50 years—from 1883 to the middle of the Great Depression—Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers remained a ubiquitous checkout-counter solution for Americans suffering from “hoarseness, tickling of the throat, and coughing.” Sure, that commercial lifespan also lines up a little uncomfortably with the golden age of bogus patent medicines and “quackery,” but Stone’s Wafers still pleaded a convincing case for legitimacy, promoting itself in the 1920s as “The Old Reliable”—a medicinal treat “of Real Benefit and Honest Merit.”

This kind of language was, admittedly, a dramatic change in tone from the very first Bronchial Wafers campaign of the mid 1880s, when the Stone Medicine Company peppered the society pages of small-town newspapers with multiple one-line advertisements masquerading as community announcements. Each one reads like a deadpan Steven Wright joke, only told with a hyperbolic Victorian sensibility that renders them more weird than funny.

This kind of language was, admittedly, a dramatic change in tone from the very first Bronchial Wafers campaign of the mid 1880s, when the Stone Medicine Company peppered the society pages of small-town newspapers with multiple one-line advertisements masquerading as community announcements. Each one reads like a deadpan Steven Wright joke, only told with a hyperbolic Victorian sensibility that renders them more weird than funny.

Mixed into the Lost & Found classifieds, for example, would be this gem: “Lost—A severe sore throat by using Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers. Pleasant to take. Convenient to carry. 25 cents. By druggists.”

Or, in the obits section: “Death comes to all, but Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers often thwart the grim messenger. Price 25 cents. They are worthy of trial.”

Want more? You got it!

More 100% Real Dr. X. Stone Wafer Ad Copy from 1885-86:

“Minnie Palmer, the famous actress, says that Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers prevented her dismissing her audience many times. 25 cents.”

“Minnie Palmer, the famous actress, says that Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers prevented her dismissing her audience many times. 25 cents.”

“Rabbits’ tails are short, but not shorter than your cough spells will be if you use Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers. 25c.”

“A pretty woman is not as likely to break a man’s heart as Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers are to cure a cough. 25c.”

“Electricity, with all its energy, is not doing as much good today as is being done by Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers. 25c.”

“Every dog has his day, cats have the nights, and man has Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers, the great throat and lung remedy. 25 cents.”

“A fight yesterday between Miss Sore Throat and Mr. Bronchial Wafers (Dr. X. Stone’s) resulted in a victory for Wafers. 25c.”

And finally, as a tasteful tribute to former President Ulysses S. Grant following news of his death: “Gen. Grant’s fame was great, as is the fame of Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers for throat and lung troubles. 25c.”

[Dr. X. Stone ad as it appeared in the Owosso Times in Michigan, 1886]

[Dr. X. Stone ad as it appeared in the Owosso Times in Michigan, 1886]

Placebo effects aside, we can at least give Dr. Stone the benefit of the doubt and presume that his trademark concoction—based on its longevity more than its advertising—really did help clear out the old windpipes. It was especially recommended for “vocalists, music teachers, preachers, and public speakers,” they said, and was “the finest, most convenient and best lubricant that was ever made for the vocal organs.

“No opium, no belladonna, and nothing to clog the system. They are to the vocal chords what oil is to machinery.”

There are just a few lingering problems, though: (a) it’s unclear what Bronchial Wafers actually were made from, and (b) we don’t know how Dr. X. Stone created it, and most importantly, (c) there’s no proof the good Doctor Stone ever actually existed at all.

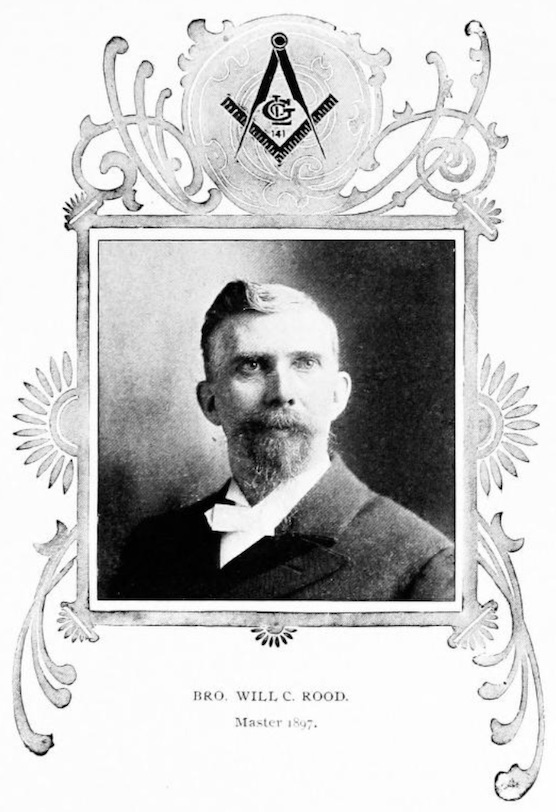

When you start to unpack the origins of this long defunct little drug, there is only one name you find every time, and it’s not Dr. Xavier Stone, nor Dr. Xander Stone, nor Dr. Xerxes Stone. Instead, it’s a dude named Will C. Rood—a duel-threat druggist and dressmaker with no clear training in either profession.

Rood Awakening

William Rood was born in the Mississippi River town of Quincy, Illinois, in 1853—the son of a farmer. He never reached a level of fame that made the adventures of his youth public knowledge, but somewhere between the farm and the Quincy Methodist College, he clearly got a crash course in entrepreneurism and mass marketing.

William Rood was born in the Mississippi River town of Quincy, Illinois, in 1853—the son of a farmer. He never reached a level of fame that made the adventures of his youth public knowledge, but somewhere between the farm and the Quincy Methodist College, he clearly got a crash course in entrepreneurism and mass marketing.

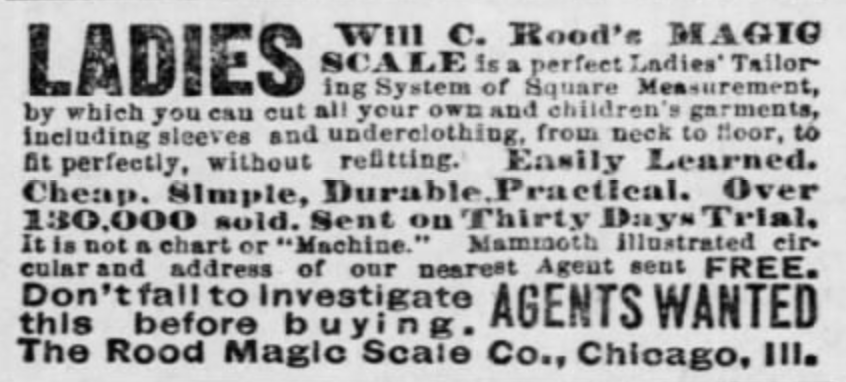

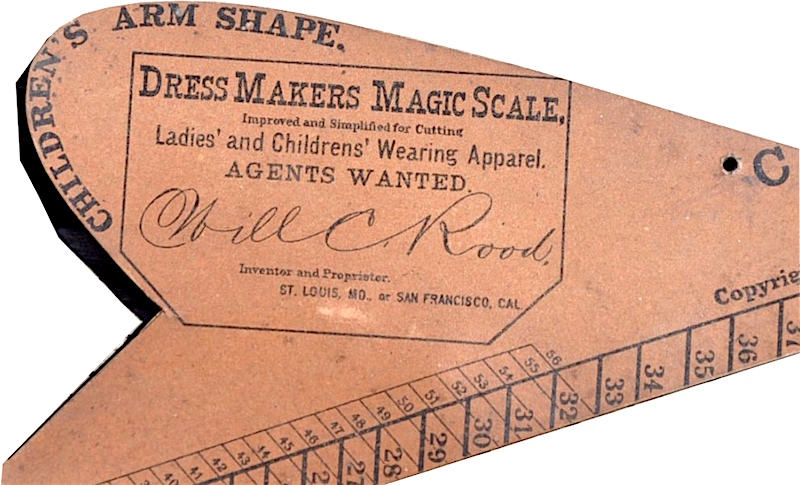

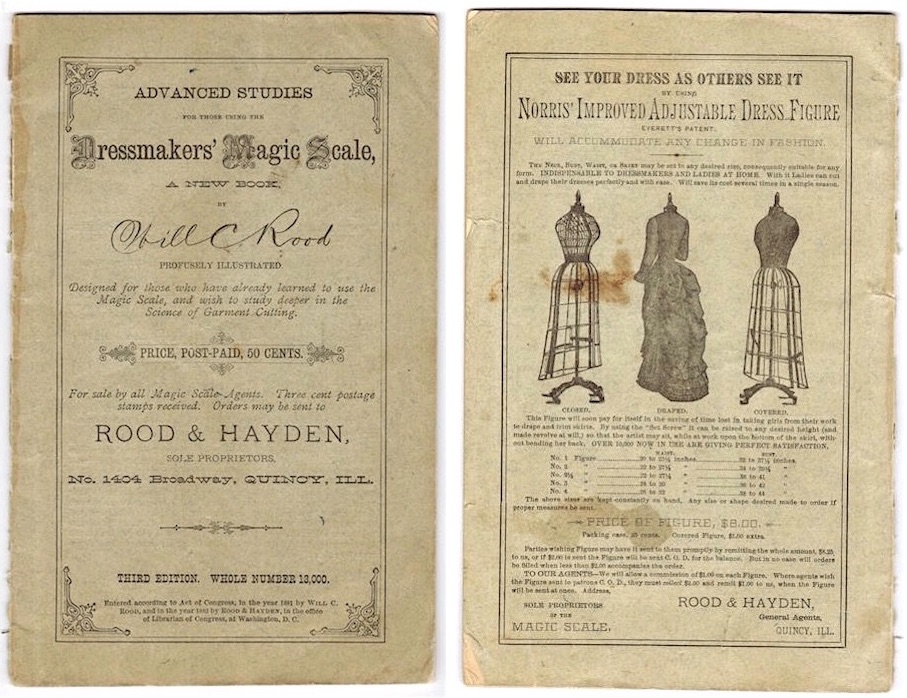

Rood seemed to have his training in education, but his first business pursuit, seemingly plucked from the sky in his mid 20s, was the invention of a new tailoring system for amateur dressmakers—a handy paint-by-numbers approach that he called the “Magic Scale.”

There were quite a few other similar “systems” and “methods” being sold during the late 1800s, giving upstart dressmakers a scientific rule book for sizing and cutting garments, supposedly resulting in a fit so perfect that a customer wouldn’t even have to try it on before buying. The creation of these systems and the outgrowth of classes, seminars and guide books related to them was partly a helpful reaction to the slow death of apprenticeships in the country, but also a pretty clear effort to undercut a traditionally female-controlled industry by selling an alternative product created by men.

[Rood Magic Scale ad from 1892]

[Rood Magic Scale ad from 1892]

We’ll never know if Will Rood’s intentions were sweet or unsavory, but he found enough happy returns from the earliest versions of his magic scale that he decided, in 1885, to organize an official business out of it with his wife Josie and business partner Norman Hayden.

The Rood Magic Scale Company, initially based out of Quincy, was formed with the intention “to manufacture and sell the dressmakers’ magic scale and other implements and books for the use of dressmakers and other garment-cutters.” Its capital stock was $30,000.

Tinker, Tailor, Druggist, Why?

The very same year he incorporated his magic scale company, Will Rood—through a series of events we will never know (tragically!)—started promoting a new product from his same Quincy, Illinois offices. It was, of course, Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers—manufactured by a mysterious new firm called the Stone Medicine Company.

The million dollar question—who was Dr. X. Stone?—seems like it should have been answered somewhere in the prolific advertising output of his namesake wafers. But alas, if the product really was initially created by some Midwestern druggist or physician by that name, I lack the evidence to confirm it. Instead, we have nothing but Will Rood’s fingerprints all over this thing from the outset.

The million dollar question—who was Dr. X. Stone?—seems like it should have been answered somewhere in the prolific advertising output of his namesake wafers. But alas, if the product really was initially created by some Midwestern druggist or physician by that name, I lack the evidence to confirm it. Instead, we have nothing but Will Rood’s fingerprints all over this thing from the outset.

In a small town like Quincy, it’s possible that Rood’s success in the dressmaking business simply opened him up to invest in a new, unrelated venture. Maybe a guy named Stone was selling his cough drops in a Quincy drug store, and Rood offered to mass distribute them. Or maybe Rood was already an amateur druggist in his own right and gave himself a cool alias with an X-men style logo to boot. Whatever the origin of the operation, an advertising avalanche was imminent.

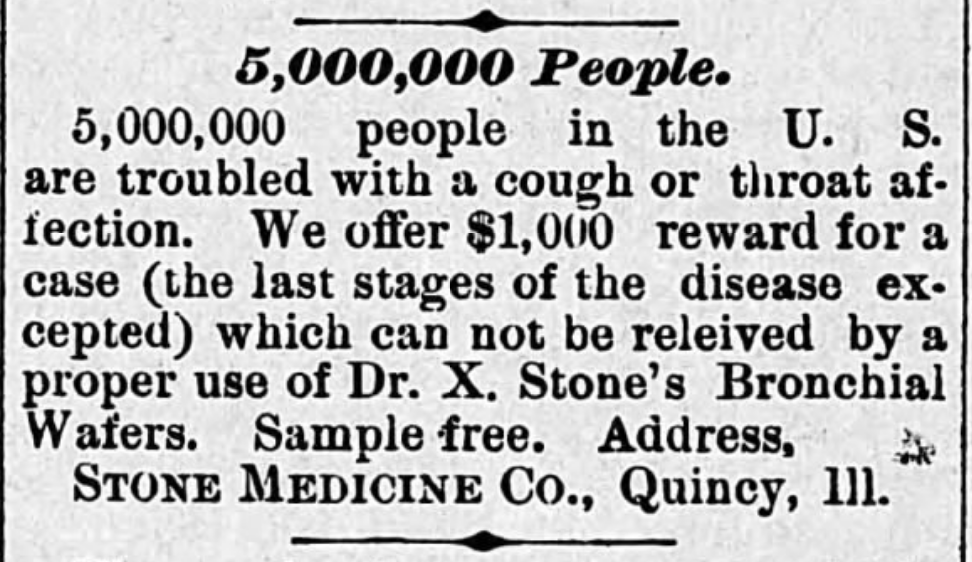

[Early Dr. X. newspaper ad by Stone Medicine Co., 1885]

[Early Dr. X. newspaper ad by Stone Medicine Co., 1885]

I am going to assume no Dr. X. customer ever successfully cashed in that $1,000 reward, but it’s not like Will Rood was risking anything with such promotions. The completely unregulated drug business of the 1880s—and the minuscule manpower required to churn out Stone Medicine’s only noteworthy product—made it a profitable and unrestricted enterprise.

By 1890, at the age of 37, Rood officially incorporated the Stone Medicine Co. for the same capital stock he’d put into the Rood Magic Scale Co., $30,000. Within a year, he and his family also made the big move up north to Chicago, bringing both of their businesses with them. Rood was ready to compete with the big boys in the western epicenter of smoker’s cough.

Master of Masons

Upon his arrival in Chicago, Rood quickly used his charm, intellect, and lead-footed sales tactics to elbow his way into the City of Broad Shoulders. He ran a publishing company to produce books and periodicals on his magic scale and scientific dressmaking techniques—one was called Will C. Rood’s Fashion and Cutting Journal. He also posted ads for Chicagoans to attend classes on how to use his system, and recruited enthusiastic converts to become sales agents.

Upon his arrival in Chicago, Rood quickly used his charm, intellect, and lead-footed sales tactics to elbow his way into the City of Broad Shoulders. He ran a publishing company to produce books and periodicals on his magic scale and scientific dressmaking techniques—one was called Will C. Rood’s Fashion and Cutting Journal. He also posted ads for Chicagoans to attend classes on how to use his system, and recruited enthusiastic converts to become sales agents.

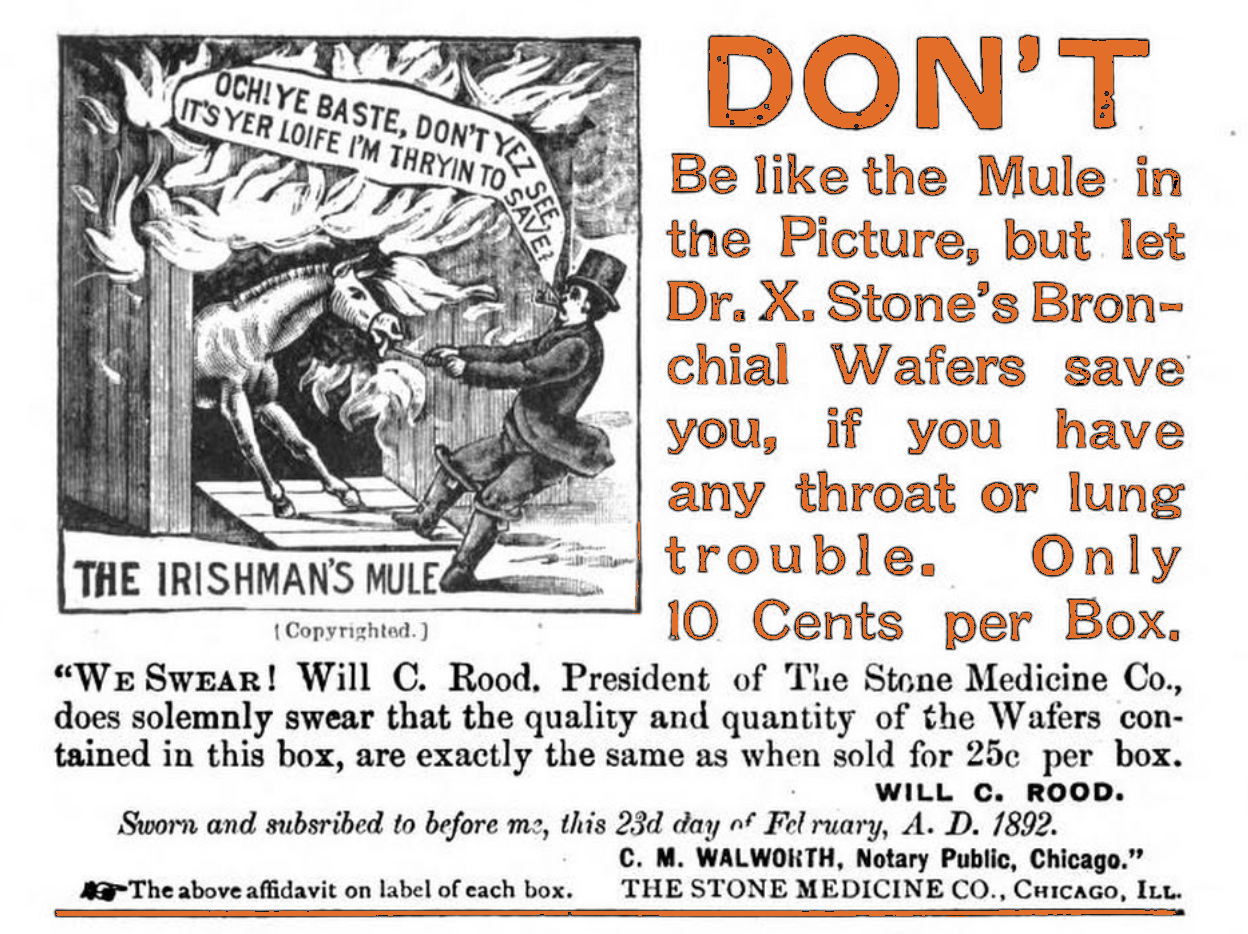

On the cough drop front, Rood wisely lowered the price on a box of Doctor Stone’s from 25 cents to a mere 10 cents, hoping to undercut the competition. When some customers and druggists questioned whether Rood was now using inferior ingredients to afford the lower retail price, he countered by running ads like the one below, making a personal vow—backed by a notary public—that Dr. X. was still the real deal.

“We Swear! Will C. Rood, President of the Stone Medicine Co., does solemnly swear that the quality and quantity of the Wafers contained in this box, are exactly the same as when sold for 25c per box.”

Again, since nobody knew what he’d used to make the stuff in the first place, such bold claims—notarized or otherwise—weren’t as ballsy as they appeared.

Rood proved shrewd yet again, and his status in turn-of-the-century Chicago high society was on the come-up. In particular, in a city filled with businessmen who moonlighted as ritual-practicing freemasons, Will Rood emerged as one of the top dogs of the ancient order.

“Mr. Rood joined the Masonic order in 1890,” the Cook County Herald later reported. “He has been worshipful master of Garden City Lodge, Chicago, high priest of York Chapter and chief officer of Tyrian Council, and he was one of the organizers and first president of the Illinois Fraternal Union of Past High Priests.”

Nothing weird about that.

By the time Rood became “Grand Master of the Grand Council of Royal and Select Master Masons of Illinois” (say that five times fast) in 1907, the papers only briefly mentioned his day job as a “medicine manufacturer.”

And how exactly was he manufacturing that famous medicine?

And how exactly was he manufacturing that famous medicine?

Well that story—much like the “Cryptic origins” of freemasonry that Rood liked to give speeches about in lodge meetings—will probably never be known either. From 1897 to 1905, the Factory Inspector of Illinois visited the Madison Street headquarters of the Stone Medicine Company each year and came away with the same employee head count each time—TWO. One man and one woman. Even the upper management of the business was a closely guarded family affair, with Josie Rood acting as secretary of both Stone Medicine and Rood Magic Scale, and daughter Rita Rood somehow ascending to the role of director for both companies before she’d even turned 20 years old.

As further evidence of Rood’s humble operation, you can actually still visit the building that served as the Stone Medicine Company’s headquarters during much of the 1910s and ‘20s. Located at 3451 W. Madison Street in Garfield Park, the little two-story shotgun-style brick shack—built in 1908—still clearly bears the name WILL C ROOD in a carved stone panel at the top of the building. It’s a cool surviving connection to our story—presuming it’s still standing by the time you’re reading this.

[The former Will C. Rood building at 3451 W. Madison St. was still bearing his name as of this photo in 2017, but a subsequent renovation removed that identifying stone for good. Its fate is unknown.]

[The former Will C. Rood building at 3451 W. Madison St. was still bearing his name as of this photo in 2017, but a subsequent renovation removed that identifying stone for good. Its fate is unknown.]

So, how did a medicine manufacturer with national distribution survive as a tiny family business? Well, a team of freelance sales agents did a lot of the leg work. Mail order sales could be handled from one office, as well. And as for who was cooking up the bronchial wafers or making the tins they came in. . . one would presume Rood had outsourced those jobs somewhere else along the line. The Stone Medicine Company, much like the legendary Dr. X. Stone, was probably more of a facade—a marketing identity rather than a traditional manufacturing operation. A little building with a name on it.

The End of Dr. X.

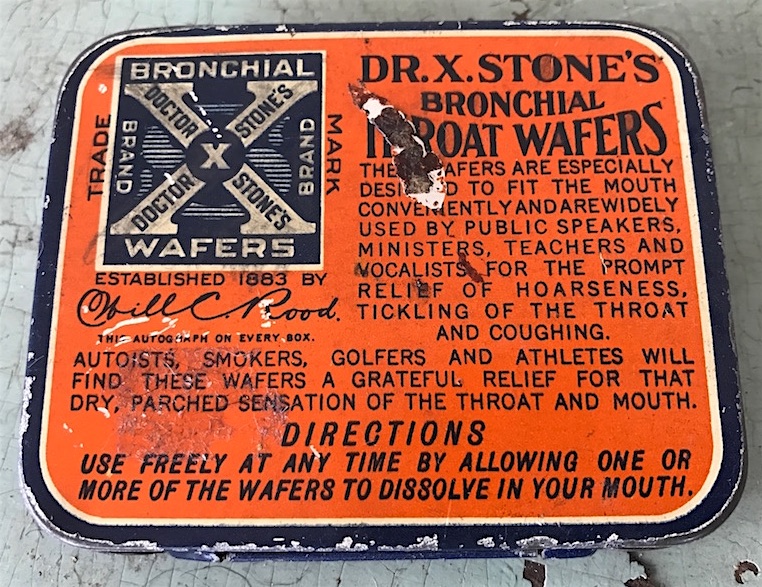

Following Will Rood’s untimely death in 1917 at the age of 64, the Stone Medicine Co. continued to produce Dr. X. Stone’s Bronchial Wafers, with Rood’s signature still featured on the tin for years to come (the Rood Magic Scale Co. seems to have folded some years prior). The company, under the new leadership of a mystery man named McCullough, moved around to a few different offices—one on Wacker, one on N. Market St., one possibly on 24th Street . . . records are scant. Most of the familiar advertisements started disappearing during the 1930s, however, and it seems as though the preferred throat wafers of the preacher and the jazz singer were no longer available by the onset of World War II.

A fellow freemason once gave a formal introduction of Will Rood in which he called him “reasonably successful in business affairs”—a kind of backhanded compliment if I ever heard one. Rood himself, in his subsequent speech, looked back on his past year as “Master of the Lodge” with the long-winded metaphor of a journey. He didn’t get the chance to make a similar speech when the Stone Medicine Company finally reached its end, so we’ll adapt his words here as a final farewell:

“A glance over the pages of our log book shows that we have cast anchor at the ports of Brotherly Love, Relief, Truth, Peace and Harmony many times, while we have been forced to stop at the port of Death a few times, as well. Owing to the dreadful financial storm through which we passed, we were unable to land at the ports of Financial and Numerical Success, but thanks to our brave old pilot, we escaped the dangerous breakers known as Debt. With the exception of this financial storm, our voyage has been peaceful and uneventful, and has, I think, resulted in strengthening the ties that bind us together. If we had done more work, and thus added more to our membership, I would unhesitatingly pronounce our voyage an unparalleled success.”

Our Artifact

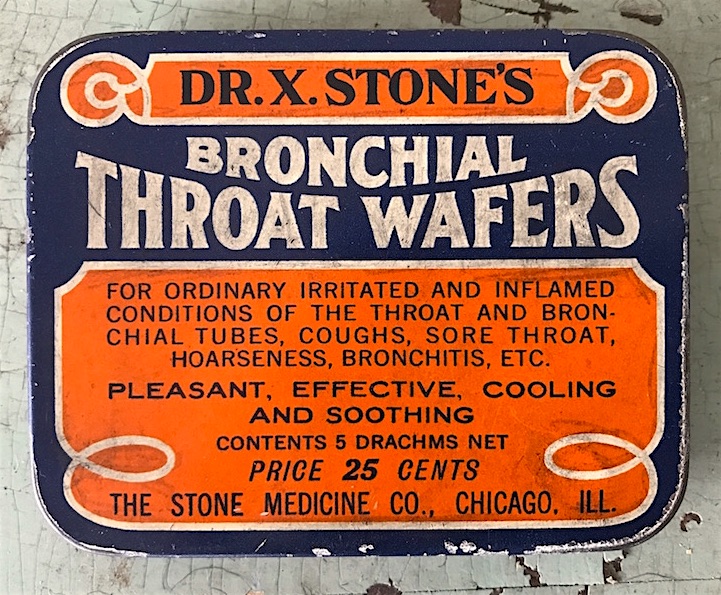

Here’s the text directly from our 1920s era Dr. X. tin—which, sadly, doesn’t have any fossilized wafers inside to analyze:

These wafers are especially designed to fit the mouth conveniently and are widely used by public speakers, ministers, teachers, and vocalists for the prompt relief of hoarseness, tickling of the throat and coughing.

Autoists, smokers, golfers and athletes will find these wafers a grateful relief for that dry, parched sensation of the throat and mouth.

DIRECTIONS:

Use freely at any time by allowing one or more of the wafers to dissolve in your mouth.

For ordinary irritated and inflamed conditions of the throat and bronchial tubes, coughs, sore throat, hoarseness, bronchitis, etc. Pleasant, effective, cooling, and soothing.

SOURCES

Gender and Technology: A Reader, edited by Nina Lerman, Ruth Oldenziel, Arwen P. Mohun

Report of the Factory Inspector of Illinois, 1905

“Chicago Man Chosen Grand Master of Royal and Select Masons,” Cook County Herald, Sept 20, 1907

Meyer Druggist, Vol. 42, 1921

The Palmyra Spectator, various editions, 1885-1886, Palmyra, Missouri

Owosso Times, various editions, 1885-1886, Owosso, Michigan

Directory of Directors in the City of Chicago, 1905

Werner’s Voice Magazine, August 1890

“New Corporations,” The InterOcean, May 9, 1885

Souvenir of the Semi-Centennial of Garden City Lodge: 1853-1903

Cutting for Men and Boys by the Magic Scale, by Will C. Rood