Museum Artifacts: Rain King Model D Sprinkler, Sunbeam Mixmaster Junior, and Sunbeam Steam or Dry Iron, 1950s

Made By: Sunbeam Corp. / Chicago Flexible Shaft Co., 5600 W. Roosevelt Rd., Chicago, IL [Cicero]

“Whenever a Sunbeam appliance goes into a home, it isn’t long before others follow. That’s because Sunbeam appliances all give that extra measure of satisfaction that creates sincere enthusiasm and confidence.” —Sunbeam Mixmaster Junior instruction manual, 1952

The Sunbeam Corporation was one of three major Chicago manufacturing institutions that could trace its origins back to the enigmatic industrialist John K. Stewart; the others being the Stewart Warner Corp. (known best for its speedometers) and the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company—a world leading producer of sheep shearers and horse clipping machines. Strange as the lineage might seem in retrospect, Sunbeam actually grew directly out of the Flexible Shaft business, operating for two decades as an offshoot product line focused on electrical appliances for the home. By the time the “Mixmaster Junior” entered the American baking arsenal in the 1950s, however, Sunbeam had cannibalized its own parent company and re-organized as one of the most successful independent houseware brands in the world.

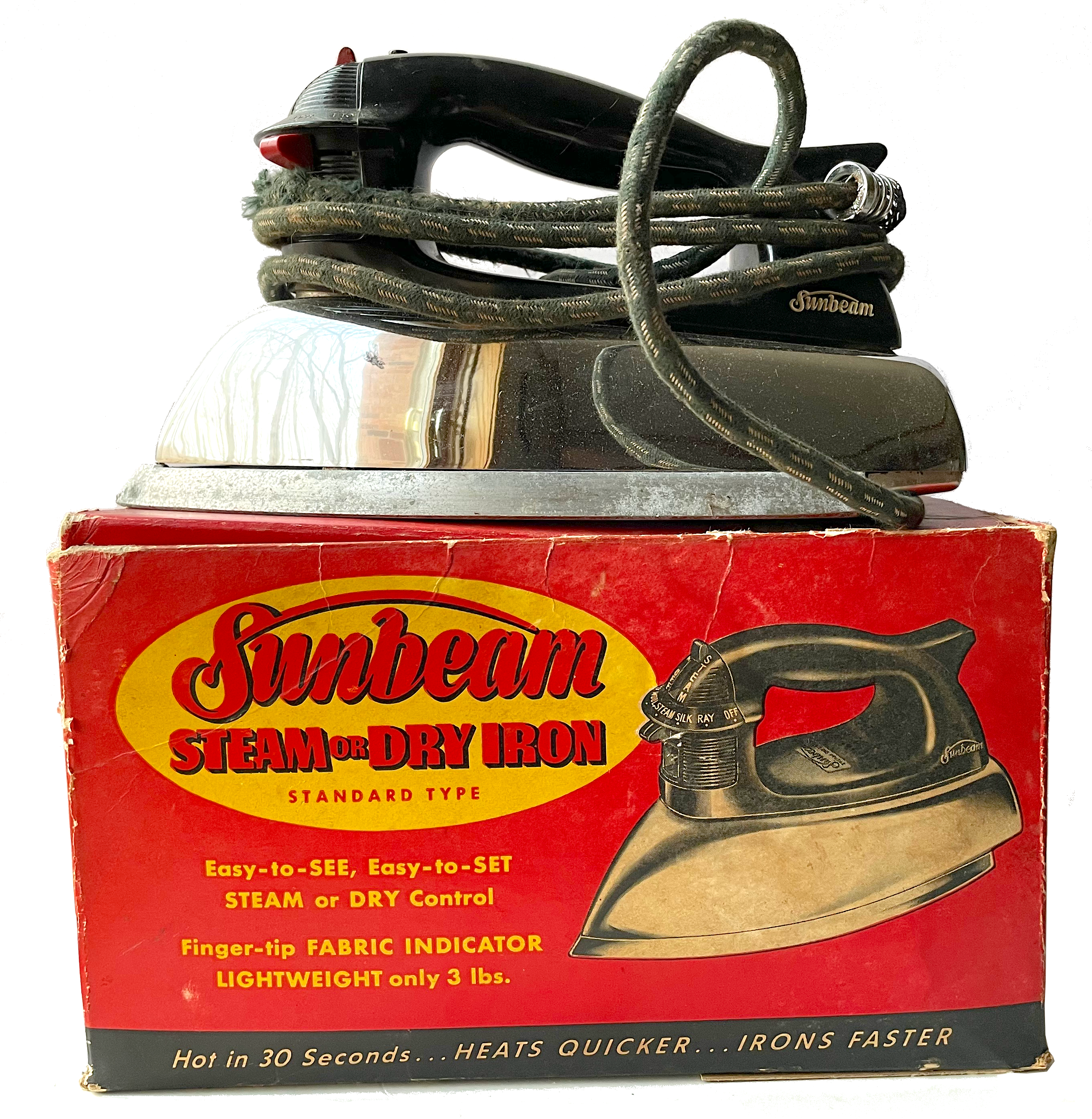

As discussed in our separate history of the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company, the unlikely emergence of the Sunbeam line really began after John Stewart sold the business in 1908. Two years later (while under the ownership of the British-based firm William Cooper & Nephews), the company introduced its first consumer home appliance, the “Princess” iron, and in 1920, another electric iron became the first to bear the Sunbeam name. By this point, Chicago Flexible Shaft had moved into a sprawling new factory complex at 5600 W. Roosevelt Road, with the goal of aggressively expanding its business and diversifying its products.

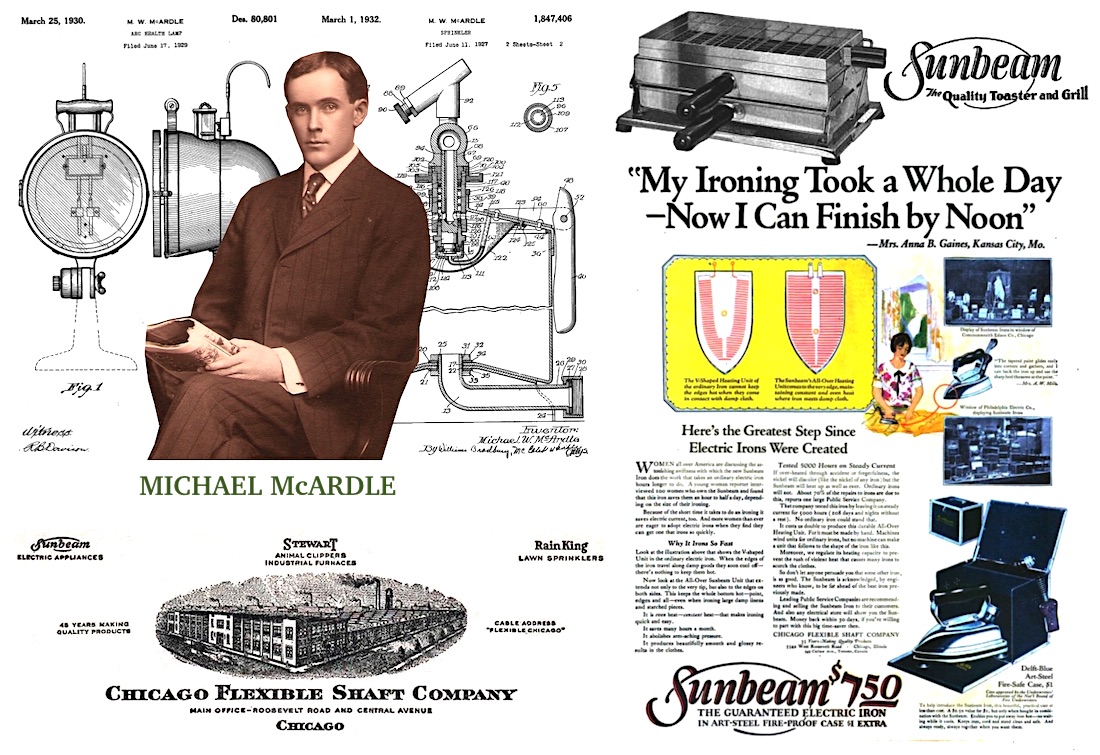

In the years that followed, there were a few men, in particular, who helped accomplish this mission, re-imagining everything from coffee makers to lawn sprinklers with bold designs and push-button functionality. The first, Michael McArdle, was a former lawyer and advertising manager who turned himself into one of the company’s leading product developers and its top executive during the ‘20s and ‘30s. His successor, Horace C. Wright, presided over the transformation from Chicago Flexible Shaft to the Sunbeam Corporation, leading the business through World War II and into its golden age of expansion. Finally, there was a Swedish immigrant and mechanical engineering savant named Ivar Jepson, who spent 40 years racking up scores of patents on iconic Sunbeam products, including the variations of the Mixmaster food mixer and the Rain King sprinkler seen in our museum collection.

[Sunbeam TV commercial, 1956. “For the best electric appliances made, look for the mark of quality: SUNBEAM!”]

History of the Sunbeam Corp., Part I: The Higher Standard

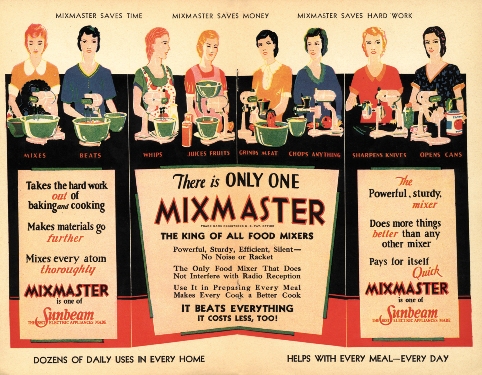

A quarter-century before the Sunbeam Corporation was officially established, a novel electric flat iron hit the market; manufactured by the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company. Advertised as “Sunbeam, the Quality Hand Iron,” this shiny new appliance was well understood by its makers to represent a potential sea change in their business, taking them beyond equestrian cosmetology and carriage heaters into America’s increasingly leisure-minded domestic life.

“The Sunbeam sets a new and higher standard in electric irons,” read a 1922 newspaper ad. “The choice of women who take pride in having the best household equipment. Superior in quality, beauty of design, and richness of finish. Made by master workmen whose years of experience guarantee a product of unusual worth. Stays out of the repair shop—built for service and lots of it. Price: $7.10.”

“The Sunbeam sets a new and higher standard in electric irons,” read a 1922 newspaper ad. “The choice of women who take pride in having the best household equipment. Superior in quality, beauty of design, and richness of finish. Made by master workmen whose years of experience guarantee a product of unusual worth. Stays out of the repair shop—built for service and lots of it. Price: $7.10.”

The Sunbeam iron didn’t necessarily operate at a higher level than the other electric iron / fire hazards of its era, but thanks to a strong national marketing campaign—mapped out in part by Chicago Flexible Shaft’s vice president and general manager Michael W. McArdle—it became a big seller, quickly inspiring a number of spin-offs under the new Sunbeam banner, including a popular electric toaster in 1924. In advertisements, “Sun-BEAM” now stood for “Best Electrical Appliances Made.”

McArdle (1874-1935) graduated from the University of Wisconsin’s School of Law in 1901 and joined the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company a few years later. It would be the only business he’d ever work for, rising from the ad department to general manager to company president. He was unusually hands-on when it came to research and development, too. As early as 1911, McArdle earned a patent on a new type of blade for the company’s animal shearing machines, and he’d collect at least 20 more over his career, dabbling in sprinklers, heating devices, irons, food choppers, and “health lamps.” His biggest contribution to Flexible Shaft’s growth, however, was his general open-mindedness and willingness to push the envelope, whether it came to design or sales tactics.

[Top Left: Michael W. McArdle and two of his patents for the Chicago Flexible Shaft Co. Right: Early Sunbeam advertisements from the 1920s.]

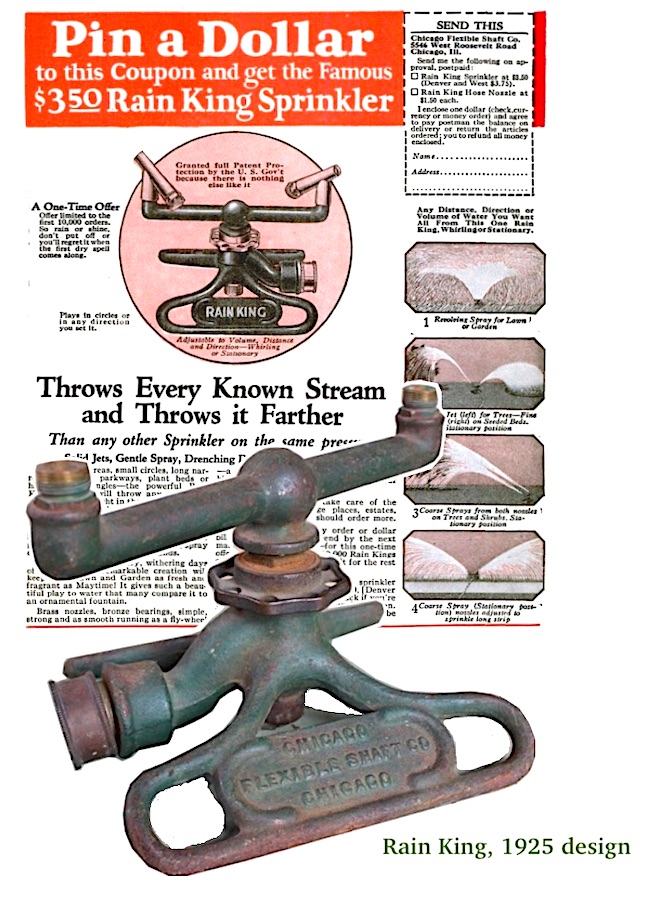

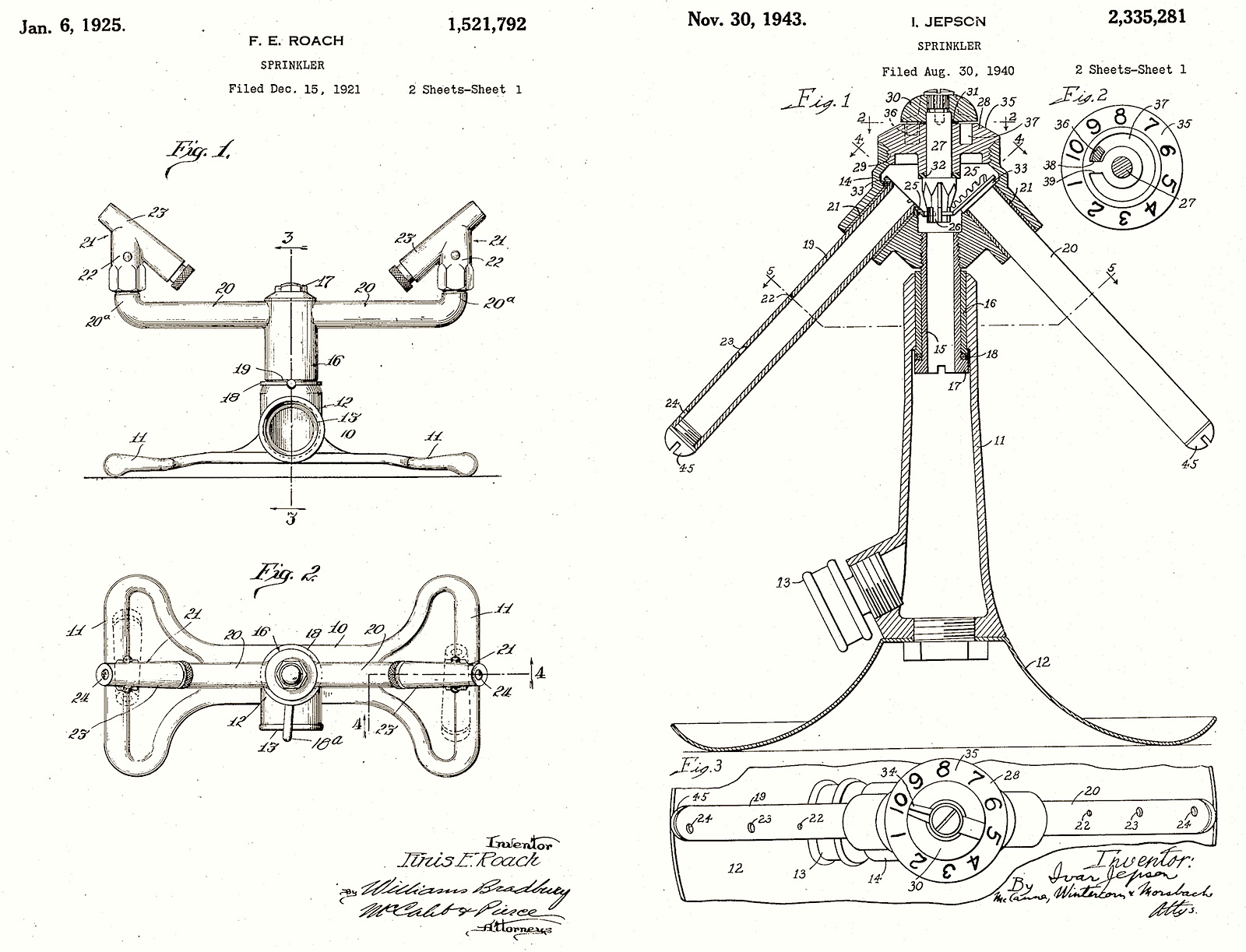

In the early 1920s, at the same time he was pushing the Sunbeam iron and toaster into American homes, McArdle started a campaign to conquer the suburban backyard, as well. In 1922, the “Rain King” brand of lawn sprinkler was introduced, based on designs by inventor Finis E. Roach (a man who usually specialized in dental appliances) and company engineer George Browning. The Rain King was a more dynamic take on the standard fountain sprinkler, “so constructed that it may be readily adjusted to meet the peculiar watering requirements of any portion of a lawn, parkway, flower bed, or the like,” Roach wrote in his patent application.

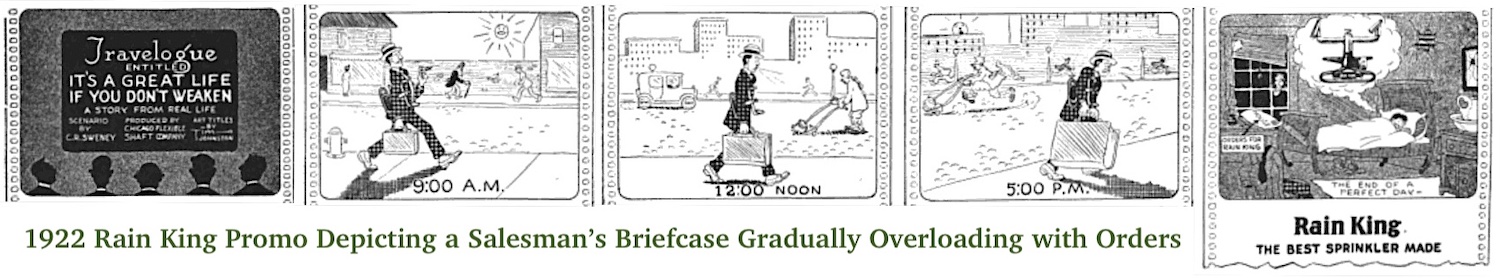

As with the early Sunbeam-branded products, McArdle wasn’t content to let the quality of the Rain King speak for itself. Competition was fierce in the years after World War I, and big national ad campaigns had to be aimed not just at the consumer market, but at the independent dealers and salesmen who could ultimately make or break a new product. With this in mind, McArdle brought in a marketing guru named C. R. Sweney—formerly of the D. B. Fisk hat company—to devise a unique strategy for getting the Rain King anointed nationwide.

As with the early Sunbeam-branded products, McArdle wasn’t content to let the quality of the Rain King speak for itself. Competition was fierce in the years after World War I, and big national ad campaigns had to be aimed not just at the consumer market, but at the independent dealers and salesmen who could ultimately make or break a new product. With this in mind, McArdle brought in a marketing guru named C. R. Sweney—formerly of the D. B. Fisk hat company—to devise a unique strategy for getting the Rain King anointed nationwide.

Sweney’s eventual methodology, as revealed in a 1923 article in Sales Management called “When You Want Distribution in a Hurry,” was to inundate would-be jobbers with personalized, often humorous direct-mail pieces; in such volume, in fact, that Chicago Flexible Shaft sent out more promo materials in one year “than they would ordinarily mail in five years.” Sweney even went out on the road with some salesmen for several weeks to get a sense of what they wanted to hear.

“After my trip I decided that all we could hope to do was to keep the salesmen from forgetting our product,” Sweney said. “Everybody else was competing for the jobbers’ salesmen’s attention. Hence, in planning the campaign I deliberately refrained from telling too much about ‘Rain King’ sprinklers. All I wanted to do was to have the jobbers’ salesmen say to themselves, ‘Well this fellow at the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company is a pretty good scout—maybe these ‘Rain King’ sprinklers are worth pushing. I’ll try one on this trip, anyway.”

The unorthodox approach paid off. Even though the Rain King cost about 3x-4x as much as the average sprinkler on the market at the time, it became a consistent seller, and hardware dealers were soon carrying and advertising the product in local papers themselves, using the preferred corporate slogan, “The Sprinkler with Brains!”

To their credit, the actual “brains” behind the Rain King never considered their work a finished product; nor did any of the Sunbeam appliances ever rise permanently above the research-and-development stage. After being elected company president in 1927, Michael McArdle only seemed to increase the time he spent working with the R&D team in Chicago to continuously refine Chicago Flexible Shaft’s existing designs and grab patents on any new innovation and style idea that bubbled out of the lab.

During this same period, there was also a plucky new draftsman on the payroll who was making a name for himself in the Roosevelt Road offices. He was 24 years old, new to the country, and working alongside much more seasoned professionals. And yet, in short order, Ivar Jepson would establish himself as “Mr. Sunbeam,” an unheralded company man who might also be the “unsung hero of American design,” as Stanford professor and IDEO founder David M. Kelley once wrote.

Part II: Reign of the Mixmaster

“An idea is abstract or wild as long as it does not work, and is practical after it has been made to work.” —Ivar Jepson, 1958

Contrary to what most of the internet seems to say on the subject, Ivar Jepson did not single-handedly invent the famous Sunbeam Mixmaster, which made its debut in 1930. A few different people could be credited with that joint honor, including Herman M. A. Strauss, John W. Lynch, and maybe most especially Albert F. Dormeyer—who never worked for Sunbeam, but designed the original industry-standard tabletop mixer in the 1920s for his own Chicago firm, the A. F. Dormeyer Company.

Contrary to what most of the internet seems to say on the subject, Ivar Jepson did not single-handedly invent the famous Sunbeam Mixmaster, which made its debut in 1930. A few different people could be credited with that joint honor, including Herman M. A. Strauss, John W. Lynch, and maybe most especially Albert F. Dormeyer—who never worked for Sunbeam, but designed the original industry-standard tabletop mixer in the 1920s for his own Chicago firm, the A. F. Dormeyer Company.

It’s very fair to say, though, that it was Jepson’s later contributions to an evolving design that propelled the Mixmaster ahead of all competitors, making it America’s favorite electric food mixer of the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s. And that, in a nutshell, is what distinguishes Jepson as a rare unicorn of industrial design. While he had hundreds of patents to his name, he was routinely an artist as much as a technician, always delivering form in league with function, and seemingly anticipating—or perhaps dictating— the public’s tastes.

“Jepson shaped the domestic landscape,” wrote Chee Pearlman, former editor of I.D. (International Design) magazine, in a 1994 editorial. “He created hundreds of objects that are now etched into our collective memory. Jepson serves as a role model for the generalist designer; he could design anything he invented, and could invent anything he designed.”

Born in Kristianstad, Sweden, in 1903, Ivar P. Jepson (sometimes spelled Jeppson or Jeppsson) grew up on a family farm, the lone son among four sisters. The plan was always a future of agriculture rather than industry, but as he grew up, Ivar couldn’t suppress his fascination with all the new gadgets of his era, from airplanes and motorcycles to simpler things like vacuum cleaners and electric fans. He studied engineering at Hessleholm Technical High School in his home country, then spent a year at the University of Berlin at Charlottenberg.

Finally, in 1925, Ivar boarded a ship for America, supposedly to follow up on a job lead he’d heard about way out in North Dakota. Once he got to Chicago, though, Jepson quickly realized he needn’t venture further. Settling into the flourishing Swedish community on the North Side, he moved into an apartment at 4222 N. Ashland Avenue and started attending meetings of the Swedish Engineers Club, which convened at 503 W. Wrightwood Avenue in Lincoln Park. Through those connections, most likely, Jepson got himself an interview with the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company just a couple months after his arrival, and by Christmas of 1925, he was employed with the company as a draftsman. When he moved up to R&D two years later, there were still just four mechanics and one development engineer on the team under McArdle.

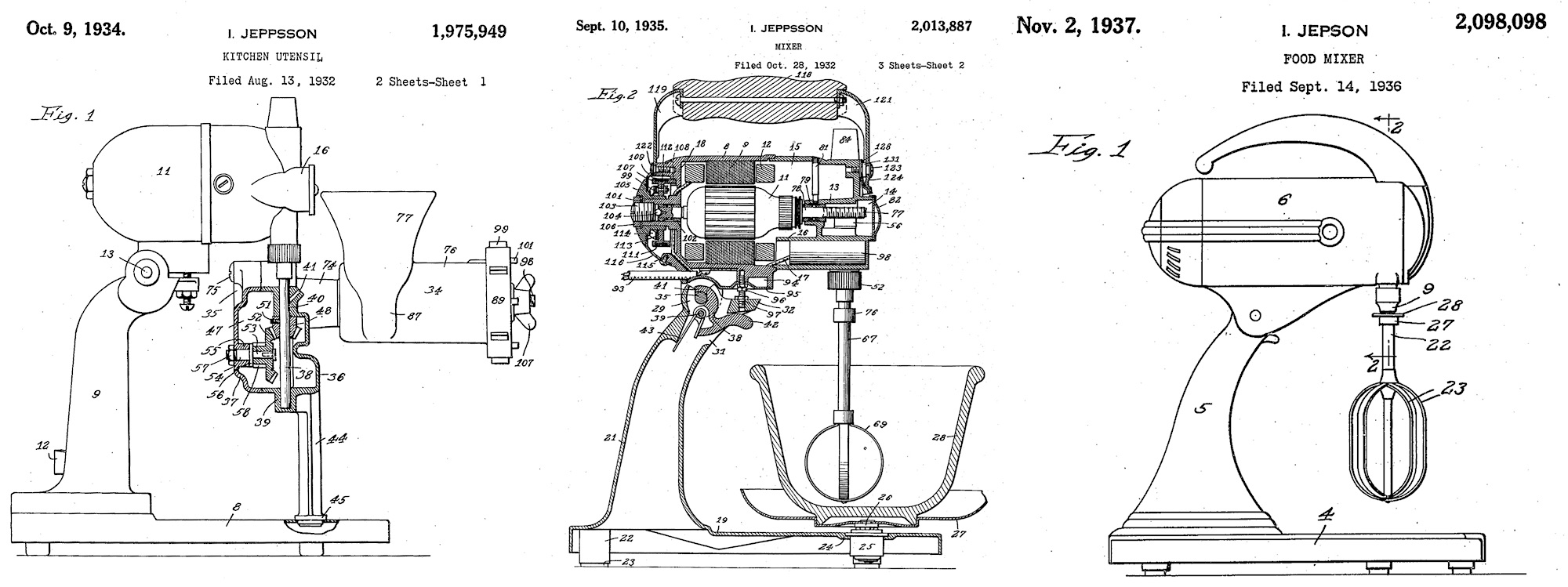

[Several early patents showing Ivar Jepson’s contributions to the evolution of the Sunbeam Mixmaster in the 1930s]

The earliest patent we could find on record for Jepson came four years later in the form of an “arc health lamp” that he co-invented with Michael McArdle himself. This must have left a positive impression on the company president, because McArdle soon had Jepson taking the lead on some of Chicago Flexible Shaft’s biggest projects. Over the next few years, Ivar patented new types of animal clippers, sadirons, “electric scissors,” can openers, toasters, pizza cutters, novelty cigarette lighters, and—of particular note in 1932—a re-conceptualized electric mixer that would improve upon the original Sunbeam Mixmaster.

“Among the various objects of the invention,” Jepson wrote in the patent application, “are to form the mixer in two units, a pedestal unit arranged to support the mixing bowl and a mixer unit consisting of a horizontally disposed motor and depending beaters, the motor being firmly supported on the pedestal for suitable rotation and being capable of complete removal from the pedestal for use as a portable mixing unit; to provide detachable heaters and improved means for releasably holding the same and driving them from the motor; to provide an arrangement of parts in a compact manner such as to cheapen the cost of construction and at the same time enhance the operating efficiency thereof; and to provide a handle construction such as to insure the proper use of the mechanism.”

By the end of 1932, despite the economic miseries of the Depression, Jepson’s work had helped the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company score a profitable year, and he was rewarded with a promotion to Chief Engineer—a role that, at the still young age of 29, essentially defined the rest of his life.

By the end of 1932, despite the economic miseries of the Depression, Jepson’s work had helped the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company score a profitable year, and he was rewarded with a promotion to Chief Engineer—a role that, at the still young age of 29, essentially defined the rest of his life.

“He was always tinkering,” Jepson’s daughter Brit Jepson d’Arbeloff told I.D. Magazine in 1994. “Everything was an idea. As long as you could plug it in and move its parts, it was something he was interested in. Basically he was an inventor. He had very rigid ideas about what people should do and what they shouldn’t do. He had kind of a mad genius attitude.”

D’Arbeloff recalled many a time that she and her siblings were used as Ivar’s “guinea pigs” at home. “It could be scary as hell,” she said. “You would get all these incredible shocks. I grew up with things like electric blankets that gave you a buzz if you sat on them. You would turn something in the frypan and get a little buzz. There was an electric hair straightener—no one in our family would get near that one!”

Jepson’s eccentric streak probably also bordered on cockiness at times. Once, when a colleague suggested he go and see a new machine at a trade show, Jepson supposedly responded, “I don’t have to go see it. I can sit here and think about it and know how it works.”

The attitude may have been justified. Through the rest of the 1930s, Jepson led a team that established an unmistakable Sunbeam aesthetic through an impressive string of game-changing designs, inspired by the Mixmaster’s success and equally by the wider trends of the Streamline Moderne. This included the popular Shavemaster line of electric razors, the Ironmaster (heir to the original Sunbeam Iron), the Automatic Toaster, and the Coffeemaster line of coffee makers.

[The Sunbeam Creative Team, c. 1940. Ivar Jepson is seated on the far right. Seated on the far left is George T. Scharfenberg, and directly behind him (standing) is Ludvik J. Koci. Photo courtesy of Tasha Coats.]

Two of the most famous models from this era, the Coffeemaster C20 (1938) and the Automatic Toaster T-9 (1939), were full-on collaborative creations that saw Jepson working with an All-Star team of talent. This included the Italian-American designer Alfonso Ianelli—a former cohort of Frank Lloyd Wright who had become a leading force in the streamline movement (as evidenced by his work on various exhibits at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933). A young Czech-American engineer named Ludvik J. Koci took ideas from the T-9 and helped develop the famous Sunbeam Toastmaster, one of the highlights of his 37 years with the business. Another new arrival, George T. Schafenberg, quickly became Jepson’s top man on all Sunbeam-branded products, including the aerodynamic Mixmaster of 1939, which set the standard for all that followed.

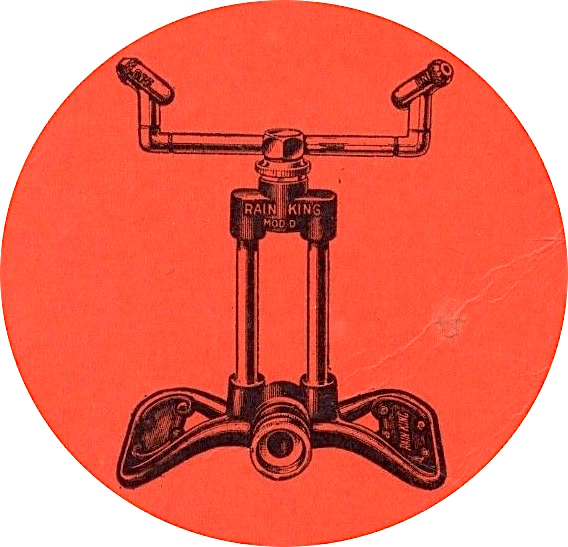

After Michael McArdle’s untimely death in 1935, Jepson and his team helped usher in a new generation of Rain King sprinklers, as well, including the 9″ tall, enamel-finished Model D featured in our museum collection. This handy double-armed device could be “easily set to water circles, long narrow strips, and hard-to-reach corners simply by turning the lock-wheel and nozzles. Each nozzle quickly adjusts for distance, direction, and volume. Throws any kind of spray from misty shower to drenching downpour.”

After Michael McArdle’s untimely death in 1935, Jepson and his team helped usher in a new generation of Rain King sprinklers, as well, including the 9″ tall, enamel-finished Model D featured in our museum collection. This handy double-armed device could be “easily set to water circles, long narrow strips, and hard-to-reach corners simply by turning the lock-wheel and nozzles. Each nozzle quickly adjusts for distance, direction, and volume. Throws any kind of spray from misty shower to drenching downpour.”

As prolific as he was in the 1930s, Ivar Jepson never really deviated from the “drenching downpour” setting when it came to his own creative output. His name is attached to over 600 patents; all of them collected while working for Chicago Flexible Shaft / Sunbeam between 1929 and 1961.

“At Sunbeam, Research and Development performs twin functions,” Jepson wrote in a company newsletter late in his career. “First, to discover and develop new products, and second, to improve the appearance, design and function of existing products, and adapt them to ever-changing consumer needs and preferences.”

***How To Use Your Rain King Model D Lawn Sprinkler***

An instructional guide provided with the Model D laid out its settings options, which you can utilize below if you (a) want to use a mid-century sprinkler for some reason, and (b) can understand these directions:

Stationary or Revolving Sprinkling

Stationary or Revolving Sprinkling

To lock the sprinkler arms, match the six sided hole in the lock wheel with the sides of the center nut in the middle of cross arms and push the lock wheel upwards to the cross arms. For Revolving: Release the hand lock wheel from the cross arms by pressing the hand lock wheel downward, clear of the center nut in the middle of the cross arms. Then set the nozzles ACROSS THE ARMS, one nozzle pointing away from you and the other nozzle towards you.

High Speed, Small Circle

High Speed, Small Circle

With the nozzles set at right angles to the revolving arms, as in the picture, the sprinkler will revolve at high speed and distribute water over a small circle.

Low Speed, Large Circle

Low Speed, Large Circle

This picture shows the proper setting of the nozzles for turning at slow speed. After setting the nozzles as shown, if arms to do not revolve, turn nozzles back until arms revolve.

III. The Wright Way

While the Depression had failed to slow down the Sunbeam machine, World War II at least redirected its energy. By this point, the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company was led by Horace Caldwell Wright, a lifelong company man who’d replaced his friend Michael McArdle as president in 1935, and subsequently took over majority ownership of the business, as well.

Wright was born in Tennessee in 1881 and moved to Chicago in the 1900s, where he got his start as a hardware dealer for the wholesale house of Hibbard, Spencer & Bartlett. By the early 1910s, he’d become one of the top young representatives of the Chicago Flexible Shaft Co., forming a successful sales team with his fellow upstart McArdle (the bond formed between the two men seems evident in the fact that Horace named his first born son William McArdle Wright).

Wright was born in Tennessee in 1881 and moved to Chicago in the 1900s, where he got his start as a hardware dealer for the wholesale house of Hibbard, Spencer & Bartlett. By the early 1910s, he’d become one of the top young representatives of the Chicago Flexible Shaft Co., forming a successful sales team with his fellow upstart McArdle (the bond formed between the two men seems evident in the fact that Horace named his first born son William McArdle Wright).

Wright’s dedication to the horse clipping and sheep shearing business was tested when he was asked to move across the world to head up Chicago Flexible Shaft’s interests in Australia. Dutifully, Horace took the assignment, and he and his family spent the next decade Down Under.

Upon his return to America in the mid ‘20s, Wright settled in Oak Park and jumped into an active role as company vice president. Like McArdle, he fancied himself a product developer, and was soon contributing to Jepson’s R&D team, putting his own name to two-dozen patents related to improvements on the company’s sprinklers, shavers, irons, and mixers.

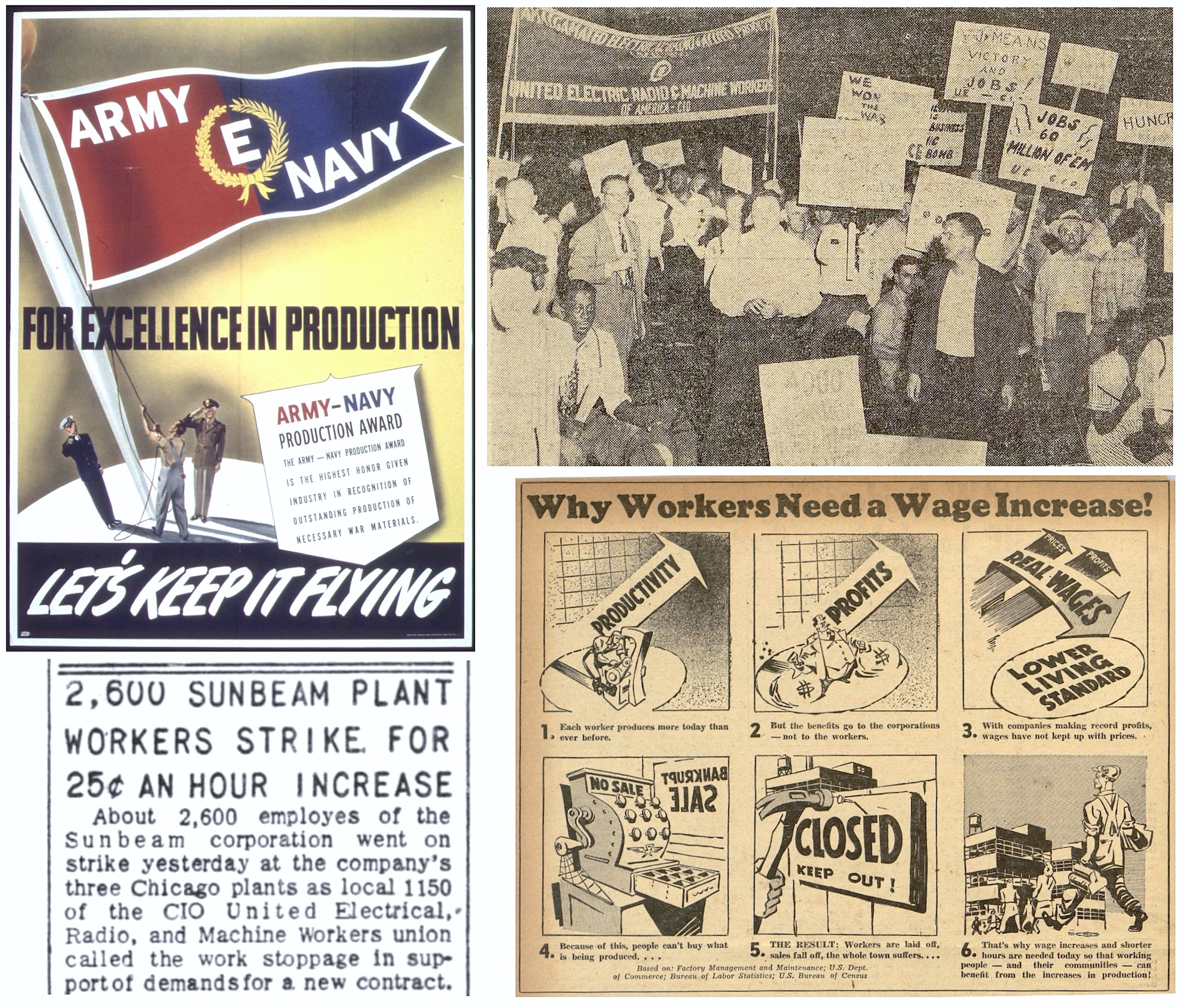

Under Wright’s watch, Chicago Flexible Shaft became “the world’s largest manufacturer of small electrical appliances,” according to the Tribune. And during the war, when those appliances had to be shelved, he helped convert the Roosevelt Road complex into a defense plant, making “shot, fuses, shells, gun loading mechanisms, and precision instruments for airplanes” (the company’s sheep shearing machines were kept in production, too, as wool was desperately needed for uniforms and blankets). Signifying the important role the company played in the war effort, Wright accepted an Army-Navy “E” Award at a ceremony outside the factory in 1943.

[Top Left: Sunbeam workers earned the Army-Navy “E” Award for great service in 1943. Top Right: Members of the UE (United Electric Radio and Machine Workers) rally at the Chicago Coliseum in 1946. Bottom Left: Local 1150 of the UE helped stage a week-long strike at the Sunbeam plant in 1949. Bottom Right: Illustration from the UE News, 1946.]

Despite appearances, there wasn’t always a sense of camaraderie among the company’s workers and its leadership. Disputes were common in the 1940s, not just in the form of union-organized walkouts, but also regular in-fighting within the unions themselves, as more conservative labor representatives clashed with what they considered to be a “Communist element” within the workforce.

In 1946, the same year Chicago Flexible Shaft was officially re-organized as the Sunbeam Corporation, picketers rallied outside the plant, clashing with police and blocking hundreds of employees from reporting to work. Another series of melees took place in 1949, as local No. 1150 of the United Electrical Radio and Machine Workers Union (UE) led a week-long walkout joined by the majority of Sunbeam’s 2,600 workers. Horace Wright, now in the role of company chairman, kept his distance, leaving new president Bernard A. Graham to fight the battle. Graham wasn’t particularly empathetic to the picketers, claiming they were trying to use Sunbeam as a “guinea pig” in a nationwide strategy to gouge the big employers in America’s growing appliance industry. The strike was largely unsuccessful, and the CIO expelled Local No. 1150 a year later, citing its rumored Communist ties. All of Sunbeam’s employees were forced to re-organize.

In 1946, the same year Chicago Flexible Shaft was officially re-organized as the Sunbeam Corporation, picketers rallied outside the plant, clashing with police and blocking hundreds of employees from reporting to work. Another series of melees took place in 1949, as local No. 1150 of the United Electrical Radio and Machine Workers Union (UE) led a week-long walkout joined by the majority of Sunbeam’s 2,600 workers. Horace Wright, now in the role of company chairman, kept his distance, leaving new president Bernard A. Graham to fight the battle. Graham wasn’t particularly empathetic to the picketers, claiming they were trying to use Sunbeam as a “guinea pig” in a nationwide strategy to gouge the big employers in America’s growing appliance industry. The strike was largely unsuccessful, and the CIO expelled Local No. 1150 a year later, citing its rumored Communist ties. All of Sunbeam’s employees were forced to re-organize.

It’s easy to understand why most of these factory workers were looking for a bigger piece of the pie. All around them, they saw the evidence of Sunbeam’s success, as the walls of the buildings were literally expanding around them. In the years after the war, Sunbeam was constantly acquiring more land and factory space, and by the mid 1950s, the massive HQ campus at 5400-5600 West Roosevelt Road was joined by additional Chicago plants at 4433 West Ogden Ave. and 1824 South Laramie St. They’d soon have more than 2 million square feet of manufacturing and office space in Chicago alone, with over 4,000 employees filling those spaces.

[Some of the post-war additions to the Sunbeam complex are still in use as part of the “Sun Gate Park” industrial park, est. 1989, at 5410-5480 W. Roosevelt Rd.]

IV. Sunbeam in the Shadows

Throughout the 1950s, Sunbeam appliances were ubiquitous in the kitchen, bathroom, living room, and garden, and the styles continued to push boundaries, as Ivar Jepson’s R&D department (which had grown to more than 50 employees) also welcomed in celebrated freelance designers like Robert Davol Budlong to add some flair to their latest looks.

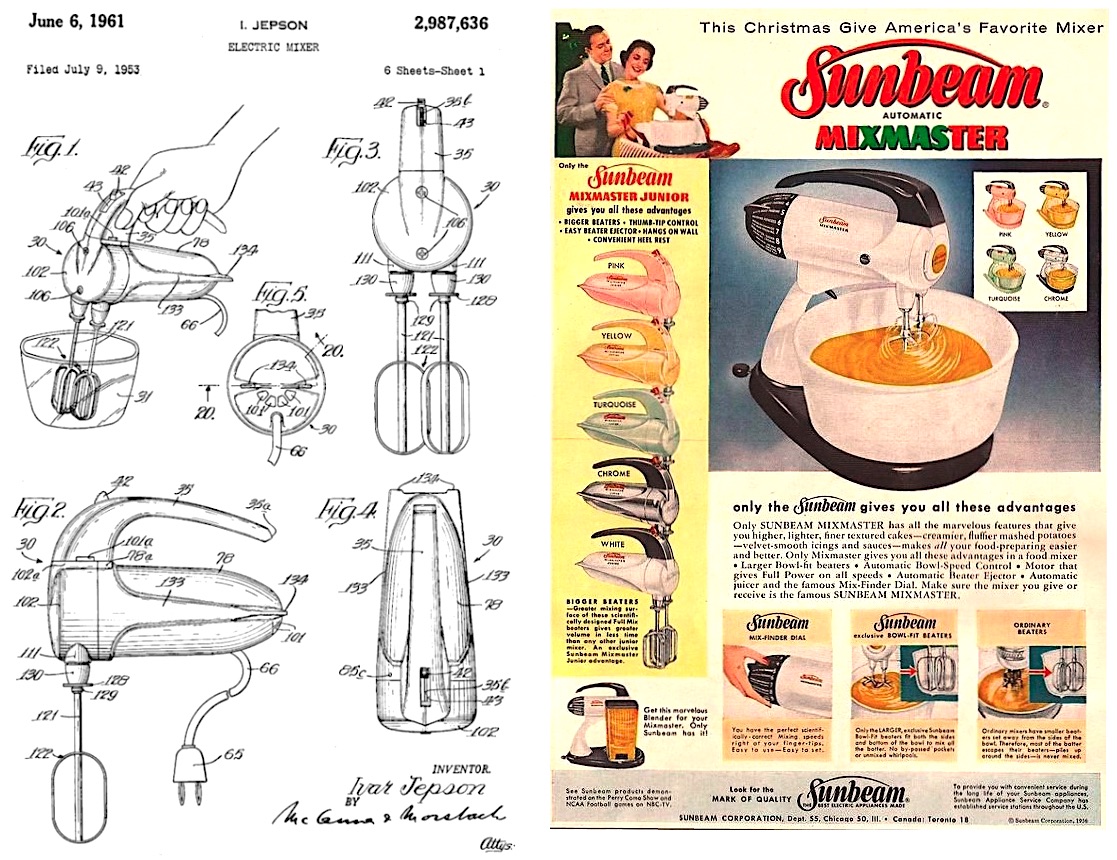

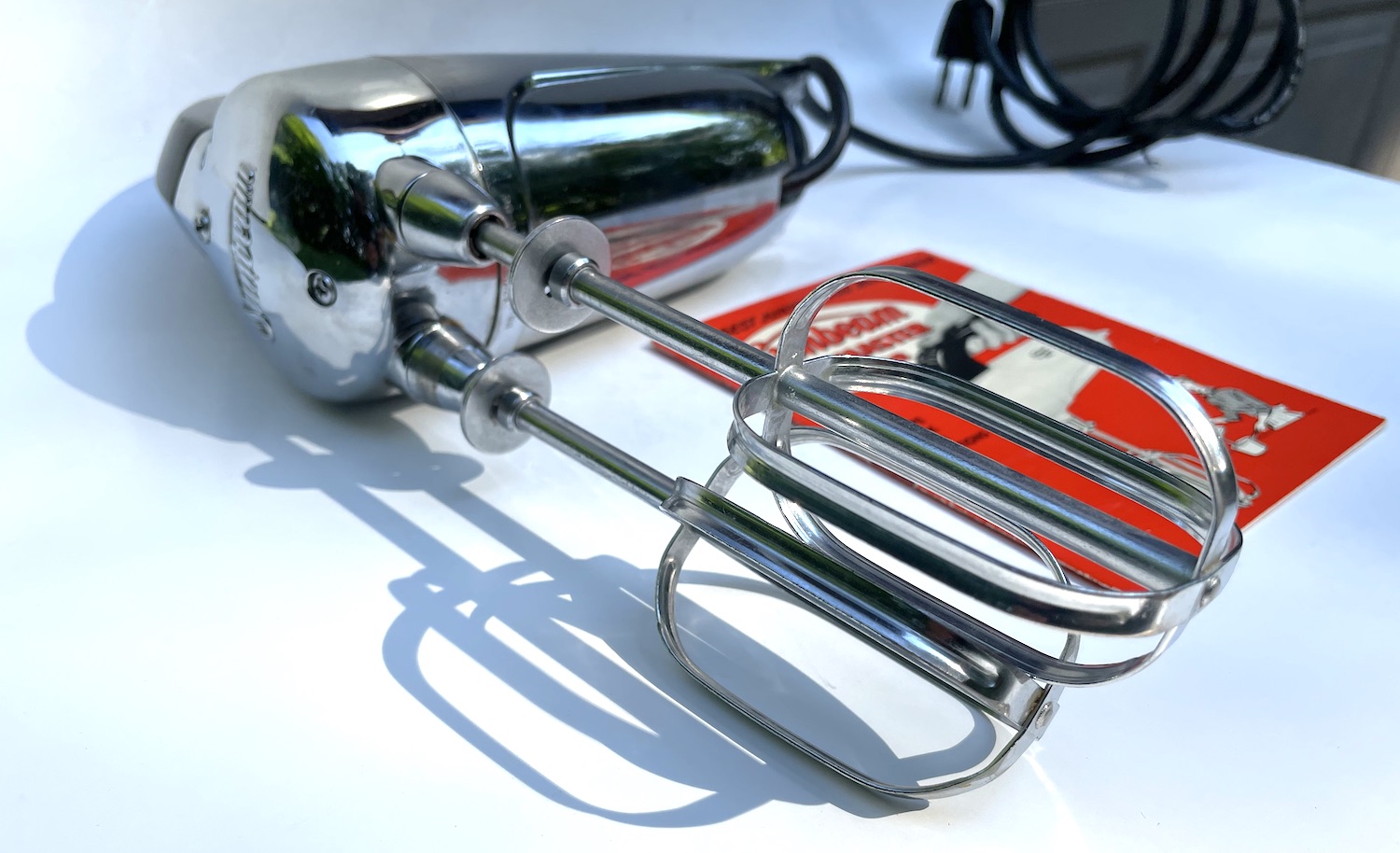

In 1953, Jepson (possibly with insights from Budlong) filed a patent on an early Mixmaster Junior—the hand-held mixer we have featured in our museum collection.

In 1953, Jepson (possibly with insights from Budlong) filed a patent on an early Mixmaster Junior—the hand-held mixer we have featured in our museum collection.

“In recent years there has been a tendency to build homes, apartments and the like with very small kitchens which really have no space for the heretofore conventional household mixer,” Jepson wrote in the patent application. “There is, therefore, a demand for a small, portable, electrically powered mixing unit which can be stored in a minimum of space and yet which is capable of performing a satisfactory mixing operation.”

At the time he was working on the Mixmaster Junior, Jepson—now about 50 years old—had developed a good working relationship with company president Barney Graham. When Graham was overthrown as part of a boardroom rebellion in 1955, however, the culture of the company began to change.

According to I.D. magazine, new president Robert P. Gwinn brought in an “emphasis on corporate hierarchy; lines of responsibility were established, stricter financial controls were introduced and a market-research section was established. . . . All this change was not to Jepson’s liking.”

[Left: One of Ivar Jepson’s Mixmaster Junior patents, filed in 1953. Right: 1956 advertisement showing the standard Mixmaster plus various colors of the Mixmaster Junior, including the chrome model seen in our museum collection.]

Feeling less room to spread his wings creatively, Ivar Jepson retired from Sunbeam in 1963. He died two years later of heart failure at the age of 62. Company chairman Horace Wright, who’d long since retired to Florida, had died in 1961, aged 80. Sunbeam’s original pioneers were mostly gone now, but in the short term, the business didn’t suffer for the loss.

Robert Gwinn, who’d first joined the company as a salesman back in the 1930s, had an appreciation for what had built the brand, and his ambition was to continue to repeat that success in every corner of the globe. In 1964, a year after Ivar Jepson’s retirement, Gwinn announced the building of a new $4 million research facility in suburban Oak Brook, largely devoted to product development for the European and Asian markets.

“We believe Chicago is the finest location for electrical research,” Gwinn said at the time. “We have every kind of the needed knowledge at our great universities and we have the scientists, technicians, and workmen here who have the know-how.”

By the 1970s, Sunbeam Corp. was still America’s biggest producer of small appliances, enjoying over $1.3 billion in annual revenue, but its commitment to Chicago was getting less clear. The company now had numerous offices and more than 75 factories (44 in the USA, 33 internationally), employing roughly 30,000 people in total; just 3,000 of whom were still based in Chicago. Robert Gwinn, who also became the CEO of Encyclopedia Britannica in the 1970s, remained confident in the face of an economic recession and increasing foreign competition, telling the Tribune in 1978 that “people aren’t inclined to buy a no-name iron or toaster. They’re willing to pay a little more for a name they trust.” Still, it seemed clear the company was starting to overstretch itself on the world stage. To keep down the overhead, Sunbeam—like many U.S. manufacturers of the time—realized it could pay workers lower wages in the southern states. That fact, combined with the deterioration of the old Roosevelt Road facilities, created a familiar and inevitable next chapter.

In 1981, Gwinn agreed to sell the Sunbeam Corporation to Allegheny International of Pittsburgh in a $640 million deal. Less than a year later, new Sunbeam president William Webber announced the closing of the last operational building in the Roosevelt Road complex, laying off 500 workers and unceremoniously ending the company’s 85-year tenure in Chicago.

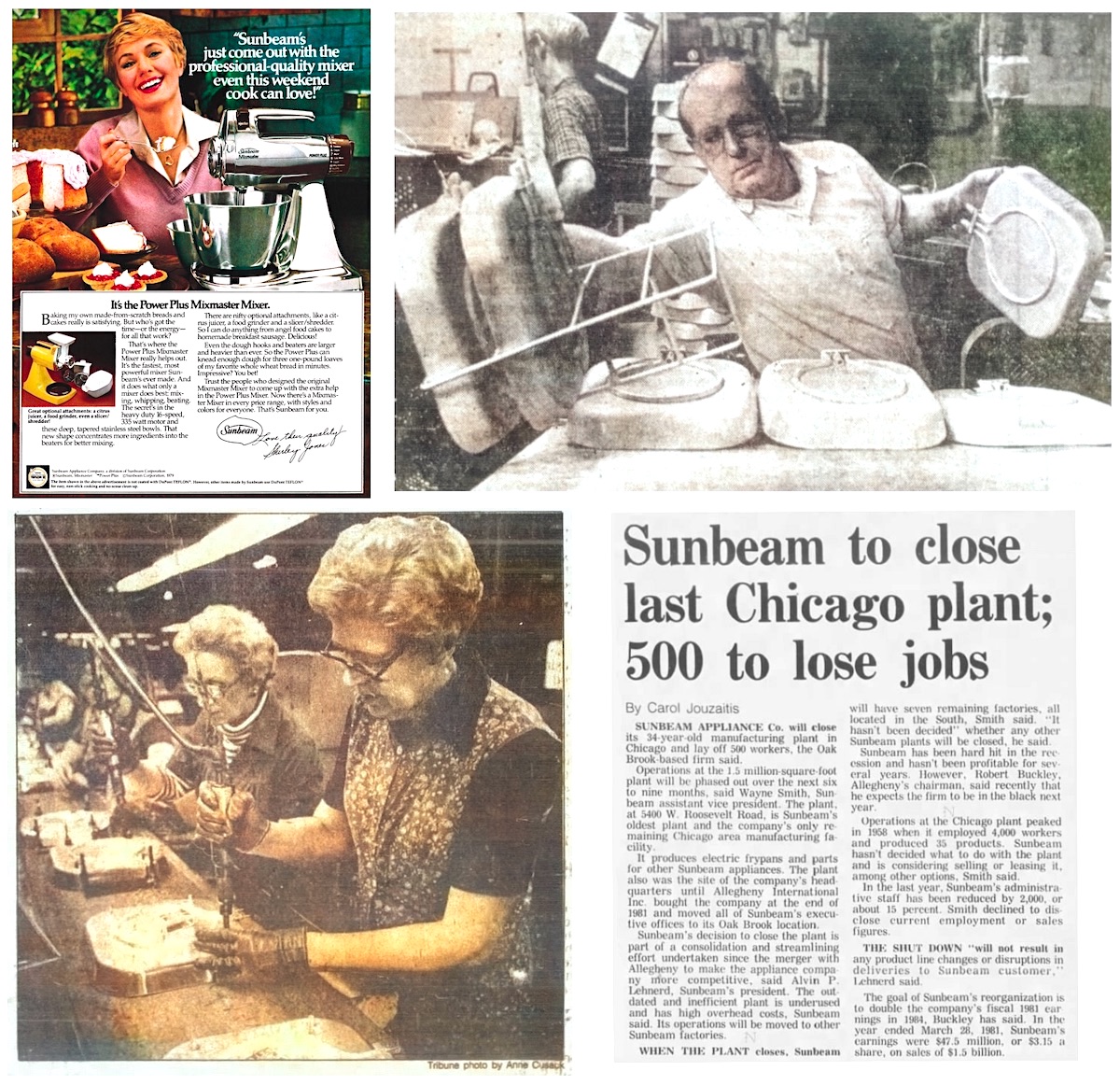

[Top Left: Mixmaster ad from 1980 featuring Shirley Jones. Top Right and Bottom Left: Workers at Sunbeam’s shrinking Roosevelt Road plant during its final years, 1978-1982. Bottom Right: Tribune piece from November 20, 1982, announcing closure of the last Chicago factory. Some corporate offices remained open in Oak Brook.]

Within a few years of leaving Chicago, Sunbeam’s sterling reputation on the stock market was also irreparably damaged. Allegheny International struggled mightily in the 1980s and went into bankruptcy. After the appliance division was re-organized in the 1990s as the Sunbeam-Oster Company, things only got uglier, as new CEO Albert Dunlap (aka “Chainsaw Al”) and several other executives were implicated in a massive accounting fraud scheme, which had ultimately backfired and sent Sunbeam into bankruptcy yet again.

The Jarden Corporation purchased the ruins of the brand in 2004, and Sunbeam Products are still sold today under the ownership of the conglomerate Newell Brands. The Mixmaster, with relatively few changes over the past 70 years, is still part of that product line, too. It is, however, made in China.

[The mid-century Sunbeam iron above is also part of our museum collection]

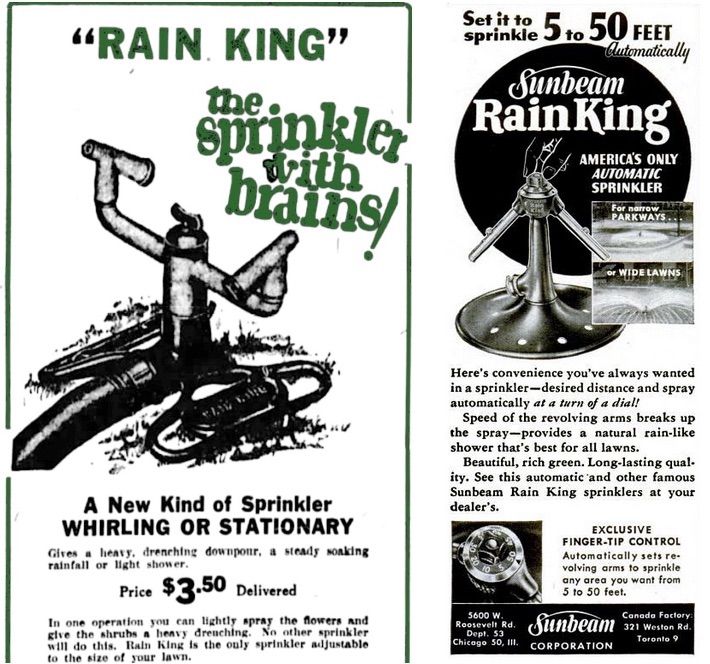

[Rain King ads from 1923 (left) and 1952 (right)]

[Rain King ads from 1923 (left) and 1952 (right)]

[F.E. Roach’s 1925 Rain King vs. Ivar Jepson’s 1940 model]

[F.E. Roach’s 1925 Rain King vs. Ivar Jepson’s 1940 model]

Sources:

“When You Want Distribution in a Hurry” – Sales Management, Vol 5, 1922

“The Army-Navy ‘E’ Citation . . . (awarded to Chicago Flexible Shaft)” – Cicero Life, April 21, 1943

“Massed Pickets of CIO Bar 850; 4 are Arrested” – Chicago Tribune, April 19, 1946

“2,600 Sunbeam Plant Workers Strike For 25-Cent an Hour Increase” – Chicago Tribune, June 2, 1949

“Union Calls 2,000 Back to Sunbeam” – Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1949

Sunbeam Mixmaster Junior Recipe Book and Instructions, 1952

“Wright Retires as Chairman of Sunbeam Corp.” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 7, 1961

“Huge Sunbeam Corporation Started Out Making Horse Shearing Machine” – Scott County Times (Forest, MS), April 3, 1963

“R. P. Gwinn: Corporation Head Held Many Posts” – Fort Lauderdale News, March 11, 1964

“Sunbeam to Build Research Facility” – Chicago Tribune, June 6, 1964

“Kitchen Electrics ‘Unique’: Made in USA” – Chicago Tribune, July 12, 1978

“Shareholders Approve AI’s Sunbeam Takeover” – Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Dec 30, 1981

“Sunbeam to Close Last Chicago Plant; 500 to Lose Jobs” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 20, 1982

“Mr. Sunbeam” – I.D. Magazine, May-June 1994

“Inventor, Engineer Ludvik J. Koci” (obit) – Chicago Tribune, Sept 30, 1999

“Modern By Design: Chicago Streamlines America” – Chicago History, Winter 2019

Mention George Browning

Archived Reader Comments:

“My grandfather, Edwin J. Gallagher, won a contest to re-name the company with his entry of “Sunbeam”. He won $1000, which was quite a bit of money at the time!” —Beth Gallagher Chipchak, 2020

“ Nice article, fun to read. Dad had a Rain King. He, Art Johnson, worked at Sunbeam in late 40’s, early 50’s. Would like to see info about the kitchen products.” —Margy Towler, 2019

Nice article, fun to read. Dad had a Rain King. He, Art Johnson, worked at Sunbeam in late 40’s, early 50’s. Would like to see info about the kitchen products.” —Margy Towler, 2019

“My father “Whitey” Schmidt started working at Sunbeam right after he got back from WWII. He worked there up until his retirement in 1980…

” —Karen Schmidt, 2019

” —Karen Schmidt, 2019

“Looks like they have torn down the building that made the lawn sprinklers because when I look at the buildings on Google maps, the only one on Roosevelt Road that is old is the one stop liquor store. ” —Randy the Wild Horse

“Yes, while the original location is marked on our “Lost Factory Map,” the building itself is long gone.” —Made in Chicago Museum

“I just bought my second one. will hook it up in tandem or use one on each lawn. BETTER THAN THE CHEAP PLASTIC CRAP OUT THERE!!” —Jim, 2018

“My Grandfather worked for Chicago Flexible Shaft-Sunbeam for over 50 yrs. He retired around 1954. He worked in the R&D Dept. and Ivar Jepson was his boss. I inherited my skills as a machinist from my Grandfather. When ever I see a old Sunbeam product brings a smile to my face and I get a feeling I once worked to help developed that product.  ” –-Richard J. Behrends, 2017

” –-Richard J. Behrends, 2017

Hello, I have a white Sunbeam mixer with beaters, 2 white bowls, small and large. It is a standup mixer with an off white cord. I was wondering if you could tell me what it is worth. I believe it is a Vista model. It is 12 speed. Dial on back is black. It works and I have not seen any chips on the bowls but no numbers. Do you know what year it may have been made?

The Vista Mixmaster was first sold 1963 and as late as 1978

Besides the Mixmaster, the Radiant Control toaster was one of Sunbeam’s most long-lived products. My parents received one as a wedding present in 1957, and I received a brand new Radiant Control toaster in 1997, without much difference in design. In combination with the bi-metallic strip and bi-metallic spring, it is an engineering masterpiece, simple in operation, and very reliable. Unfortunately, revised safety codes would have meant an expensive design change, and would have lost that iconic look that stood the test of time for 50 years.

I started working for Sunbeam in 1967 as a Value Engineer. My job was to determine Sunbeam’s cost to make a product. I remember one of the first products I worked on was the GE Toaster oven. According to the Sunbeam numbers I used we would have lost money on every unit if we were making the Toaster Oven.

We have a Sunbeam automatic toaster given to us as a wedding gift July 29, 1956, which has been in use ever since and is still bright and shiny after 66 years of marriage!

Hi, I had two Arts and Crafts period light fixtures. They were did brass inverted domes hanging from brass chains. The lights were made by Sunbeam with the electrical components made by National X-ray lighting. I sold them a an auction house. Has anyone else seen such fixtures?

I have a large collection of Sunbeam and other sprinklers. I am looking for someplace to donate them to. Any ideas? Thank you

I worked as a Sunbeam sales representative in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In that short period of time, I and Sunbeam retailers saw product quality deteriorate. Cheaper parts were incorporated into the products (to “value engineer”), and some manufacturing was moved to Mexico, resulting in many products returned as defective due to poor quality.

Sunbeam’s “LeChef” food processor was a worthy well-made and well-priced competitor to Cuisinart at the time and sold very well. But by about 1984, the decline of Sunbeam was well underway under Allegheny International.

For many years , Sunbeam has been just a name that was purchased, and is no better and no worse than similar products probably made in the same factories in China.

Ivar P. Jepson was my grandfather. Thanks so much for this article – I learned things I did not know. I was very young when he died, but I remember him and spent a lot of time in his workshop in Duxbury, MA that he built after he retired in the 1960’s. I would be happy to assist, to the extent I can, researchers or curators examining his work.

My grandfather was President from 1946-1955.

you have done a good job on sunbeam. i first noticed your presence when i was curious about a house in beverly and then found the history of stewart. some day i shall take a trip up to see the museum. in my ninety’s now and saw many of the chicago companies grow. i also saw what happened to the factory buildings. andy lapen, who owns sunbeam property is a friend since his dad bought his first chicago building around1970.

I bought a Rain King D-1 at a yard sale five years ago for $2. My wife was skeptical. it became her favorite sprinkler. Still works like a champ. I went out and bought another D-1 on eBay this week. The D-1 rates up there with Dormeyer electric drills and the 22-inch weber Grill and Mercedes diesel motorcars in terms of longevity. This stuff is just plain bullet proof!

I have a Rain King Sunbeam Model D: Water leaks from center post. Is the hex fitting under the roating head a nut that can be unscrewed to take the top off. Can’t tell if it’s cas as part of the unit or a nut that can me unscrewed.

Thanks.

Townsend

I have a sunbeam Rain King Model D-1. It leaks from the center post under the rotating head. Sounds like the same problem as Townsend’s. I would love to refurbish it and use it. I’ve been using it as a garden ornament but it deserves more! Any advice will be welcomed- kindly, Eileen

I had my first manual Rain King in 1957. I have acquired several others including the K-20a. Curious about the red dial versus the yellow dial. And about the manufacturing history of the K-20b traveling sprinkler with its long neck. Love the design of these spinners.

I have a Model D and it won’t rotate.

Water is spraying out of middle shaft

Where it rotates. Cleaned nozzles no

Plugs.

We have a model H Rain King that unfortunately has been sitting in a garage for at least 10 years. I would like to restore and preserve it. What do you recommend?

I am baffled as to how I am just now finding this forum. I am a recognized authority on antique/vintage lawn and garden sprinklers,…. with a small restoration business here at home.

My data-base, of every sprinkler of note, goes back 40 yrs. Pre-interent, pre-google. While my 380 unit collection pales in comparison to the top 5 collections in North America, I am know my stuff. Always more than happy to service any unit that comes along. I have work in print/magazines…and several of my restorations are in each of the 3 Irrigation Museums.

My eBay user ID = Oakly108. Feel free to look at my work on my YT channel. Coolyards

I have a Rain King Model K2 of my father’s that I think is from the early 50’s and still use it regularly. I particularly like the #5 setting as it concentrates the water lower to the ground and a smaller diameter. My question is there any maintenance that needs to be performed regularly on these, I don’ recall that my dad did anything, and it still runs fine although I hear a rotational ‘noise’ and wonder if there are any bearings needing grease? Or is the rotating head somehow riding on a cushion of water?

I found n old Rain King K-2 that’s in pretty rough shape. it works but the dial on top will only rotate from 0 to 10 ( hard to read) Can it be rebuilt and are there parts available , When were they made , from year to ?

Thanks,

Rod

Rod: Your choices are limited by values. A replacement knob is out of the question, as it would come with another SRK, and the minimum on eBay for anything, is now $20-30. Further to that, your K-2….the most common sprinkler of any brand, for all time, can be had for the cost of a knob. Rough shape = junk. Good Luck, Coolyards

Have a Rain King Model K-20A, the traveling sprinkler with the tape. Needs repair. Have any recommendations for contacts? A great remembrance growing up running thru water and my Dad.

Harry, I have restored 34 K-20’s, 14 Marina Blue K-20A’s, and 9 of the RARE Canadian model, with Yellow Knob……I have one opened up as I type…..getting a new shut-off clutch puck. Video is available on my YT channel…..and, shipping would be to 48170, Michigan…..should you decide to have it made working properly, again. Good Luck, Coolyards

I have a rain king hose nozzle

Patent 9-2-24

Anyone have more information?

certainly. It will be stamped as a Stewart, with a lock nut on the backside of the spray barrel….send along some photos…and Good Luck, Coolyards

I used John Deer green and it matched perfect.

Hello,

I recently acquired an old Rain King. Thing works like a champ, but I was thinking or repainting it (most all the paint is gone). So 2 things. Is it possible to take this apart so I can paint the cast body? 2. What was the original color. It appears to be a sort of lime-ish green?

Thank you,

Sean

Sean: an old RK says virtual nothing of what you speak of. Like, I have an old Ford…..Send along some photos, and lets see what you have. ALL sprinklers can be disassembled. The original color will certainly be present, with some simple parts removed. Sounds like a SUN-Ron model..Good Luck, Coolyards

I have a Sunbeam Automatic Rainking model K2 or K3, hard to tell.

When I turn on the water is starts to rotate, then stops. Is there anything

I can do to make it rotate?

Full water pressure measures at 60-70 psi. If it is not rotating, than start by checking to see if the turret has blockage…..remove both spray bar tips, for cleaning as well. Coolyards

I my boyfriend found a chrome rainking sprinkler nozzle. We was trying to find out how old it was?

I inherited a flexible Shaft Co. Toronto Majestic Rain King sprinkler and it leaks at the top of the posts where the rotating head fits. Someone has tried to fix it previously but alias they only stripped the brass nut. If you have a parts list or exploded view and maintenance suggestions I would appreciate any help you could give me. If you have theory behind the various features they would make interesting reading and help me pass on yesterdays technology to my grand kids. I am interested in the seal and the operation of the wheel

Thank you for your assistance and consideration Ian

Send me some photos…….with the understanding that you could have a non-repairable, and easily replaceable sprinkler. No false hope from Coolyards.