Museum Artifact: Super-Sensitive Stainless Strings – Viola A and D Strings, c. 1950s

Made By: Super Sensitive Musical String Company, 4814 W. Division St., Chicago, IL [North Austin]

The Super-Sensitive Musical String Company has the longest name of any business featured in the Made In Chicago Museum, but its time in Chicago was comparatively brief; and its clientele notably niche. Before and after moving its operation to Florida in the early 1970s, Super-Sensitive primarily served the needs of student musicians—manufacturing quality stainless steel strings for both high-end and garden variety violins, violas, basses, cellos, and the like.

According to a 1968 advertisement in The School Musician magazine, there were “8 Reasons Why Super-Sensitive Stainless Steel Strings are best for your bow instrument:

According to a 1968 advertisement in The School Musician magazine, there were “8 Reasons Why Super-Sensitive Stainless Steel Strings are best for your bow instrument:

- Stay in tune longer

- Uniform construction

- Won’t rust or corrode

- Modern manufacturing

- 100% hand-inspected

- Perfect tone

- Attractively priced

- Unaffected by humidity or temperature changes”

These were the same reasons that Super-Sensitive strings were embraced and endorsed by some of the world’s great musicians, from Fritz Kreisler and Gregor Piatigorsky in the 1940s up through Itzhak Perlman and Yehudi Menuhin in the ‘80s.

The company was still producing its Red Label strings in Sarasota, Florida, up until 2021, when all of its lines were acquired by the world’s largest string maker, D’Addario.

The sale and essential demise of the business brought some renewed interest in Super-Sensitive’s early Chicago years and the somewhat contested origins of its innovative product. Here’s what we know . . .

[Then former Super-Sensitive Musical String factory at 4814 W. Division Street, as seen in the 1960s (left) and 2023 (right).]

History of the Super-Sensitive Musical String Co., Part I: Wackerle & Sindelar

According to the 1998 catalog of the Super-Sensitive Musical String Co., the business “was founded in Chicago, Illinois in 1930 by a violinist who was frustrated by the gut strings of his day. The gut strings would lose their pitch after a very short period of time. After conducting extensive research, he developed a stainless steel string.”

For whatever reason, the official corporate version of this tale often omitted the name of the founder himself, which led to a little bit of debate—or just confusion—about his actual identity over the years.

For whatever reason, the official corporate version of this tale often omitted the name of the founder himself, which led to a little bit of debate—or just confusion—about his actual identity over the years.

Today, depending on which internet search result you randomly land upon, the invention of the Super-Sensitive string will be credited to either Lewis Edward “Ed” Wackerle (b. 1888) or Frank Sindelar (b. 1882). Both Chicagoans, the former was a metalworker and an engineer, while the latter was a “luthier,” or maker and repairer of stringed instruments; specifically violins in Sindelar’s case.

While we’d love to stir up some posthumous drama between the two men for entertainment value, the bread crumbs suggest more of a friendly business relationship rather than a rivalry.

Ed Wackerle is the guy who collected the patents you can see listed on the Super-Sensitive viola strings in our museum collection: #2,241,282 (filed in 1939) and #2,241,283 (filed in 1940). Both inventions relate to the function and production of “a musical string comprising a wire encased in a thermosetting phenolic resin and wrapped with metal tape; the resin serving to insulate the wire and tape electrically from each other.” Once approved, these patents formed the foundation of the Super-Sensitive Musical String Company, which—despite its oft-listed establishment date of 1930—didn’t really become a trademark and a proper business until the early 1940s.

[Two “Musical String” patents awarded to Lewis Edward Wackerle in 1941]

Wackerle was a native of Meredosia, Illinois, near Springfield, and spent much of his early life working as a building superintendent and chief engineer at the Illinois Woman’s College (later known as MacMurray College) in nearby Jacksonville, IL. He dabbled in radio communications during the 1920s and, according to one story, enjoyed playing around with a new-fangled mechanical violin—“a nickelodeon-type machine similar to a coin-operated player piano.” Only trouble was, the gut strings on the instrument never stayed in tune.

By 1930, Wackerle and his family had moved north to Chicago, likely to find better prospects during the Depression. Over the next decade, Ed continued working for other employers while slowly fine-tuning his steel string concept in his spare time. This included a stint with the Interstate Metal Products Co., at 4433 Ogden Avenue, where he served as a design engineer developing a line of Art Deco metal furniture.

Frank Sindelar, meanwhile, was already a well known violin maker by this point, connected both to the old European tradition (he studied in Vienna) and the highly regarded Chicago school of craftsmen, having trained under local master John Hornsteiner. He opened his own shop in 1917 and painstakingly produced more than 300 instruments over the next few decades, some of which still go on sale today for multiple thousands of dollars. “It’s not an art,” Sindelar said of his work in a 1948 Tribune feature, “but a lifetime study. It takes so many years to learn what not to do.”

[Left: Frank Sindelar helps out a child prodigy at his Chicago violin shop, c. 1930s. Right: A 1933 Sindelar violin + label]

If Ed Wackerle wanted to test the usefulness of his steel string in the late 1930s, Frank Sindelar likely would have been the one man in Chicago most capable of making a nuanced assessment of it.

And so, the Super-Sensitive string entered its testing phase just before the outset of World War II, with Wackerle as the tinkering engineer behind it, and Sindelar as its badge of authenticity. The best evidence we have to support this united effort comes from a pretty famous first-person witness: the great American violinist Aaron Rosand (1927-2019).

In a 2014 interview with the British music magazine The Strad, Rosand discussed his time as a 12 year-old prodigy at the Chicago Musical College in 1939.

“At around the same time,” he recalled, “I was actually instrumental – albeit inadvertently – in developing the steel string. Frank Sindelar, a very fine violin maker whose shop was within walking distance of my home on the west side of Chicago, took a personal interest in me after my debut, aged ten, with the Chicago Symphony, and subsequent local appearances. He loaned me a lovely small Gagliano violin, and with this instrument I became involved in regular string experiments.

“I was selected to be the guinea pig for some new steel strings (in all gauges) produced by the forerunner of the Super-Sensitive Musical Strings Company. I soon learnt how string thickness affects the velocity of response and the quality of sound. The string’s manufacturer was a steelworker and amateur violinist, and he took my youthful advice to make them thinner for a quicker reaction. The strings were very durable and I used them throughout my high school years.”

It’s a fairly safe assumption that the “steelworker” to which Rosand referred was our pal Ed Wackerle. And, further fitting this narrative, a trademark application filed by Wackerle in 1945 states that he had been doing business as the Super-Sensitive Musical String Company since July of 1941. This is a full 11 years after the supposed founding of the enterprise, but perfectly in line with the two Wackerle string patents, which were both approved by the U.S. Patent Office in 1941.

There was an element of bad timing here, considering that World War II was about to usher in four years of metal rationing—not ideal for a business dependent on steel. But with Sindelar’s help, word of the new strings still managed to reach some musicians of considerable influence during the war.

[Left: Cartoon of violinist Fritz Kreisler from the New Yorker, 1925. Center: Photo of Kreisler from the same period. Right and Top: Ed Wackerle’s original trademark for the Super-Sensitive Musical String Co., in use since 1941 and filed in 1945. Kreisler became an important early endorser of the brand.]

Part II: On Division Street

“Like all friends who are worth the having, violins are super-sensitive and temperamental in the highest degree, and if an artist is to get the best that is in them he must treat them with the utmost care and consideration.” —Fritz Kreisler, violinist, 1928

The Austrian violinist and composer Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962) was speaking about the “super-sensitive” nature of violin strings long before it became a brand name, and as one of the foremost players on Earth, his early endorsement of Wackerle and Sindelar’s new string was a massive coup. Kreisler had moved to the United States during World War II, and was known to have stopped by Sindelar’s shop on more than one occasion.

The great Ukrainian-born cellist Gregor Piatigorsky had also settled in the U.S. during the 1940s and similarly took a liking to the Super Sensitive string, even striking a deal with the fledgling Chicago business to send a few boxes of the strings to the Soviet embassy so some of his countrymen back home could get access to them.

The great Ukrainian-born cellist Gregor Piatigorsky had also settled in the U.S. during the 1940s and similarly took a liking to the Super Sensitive string, even striking a deal with the fledgling Chicago business to send a few boxes of the strings to the Soviet embassy so some of his countrymen back home could get access to them.

Mainstream interest naturally followed among string players at all levels, especially those living in regions where hot and muggy weather wreaked havoc on their tunings.

“To live in a climate where the temperature goes up to 117 degrees must indeed be troublesome for a violinist,” Etude magazine editor Harold Berkeley wrote in reply to a reader’s letter in the December 1944 edition of the classical music publication. “I can easily understand that your strings do not stay in tune. . . You might try the ‘Super-Sensitive’ strings, which have steel centers wound with aluminum. . . I have heard good reports of them.”

While the positive reputation of Super-Sensitive strings continued to grow in the years after the war, the actual manufacturing operation remained very small, abiding by the sort of hand-crafted principles that Frank Sindelar would have applied to the making of the string instrument itself.

By 1950, a small factory was in use at 4814 West Division Street, with less than 10 workers on the payroll. After the deaths of both Ed Wackerle and Frank Sindelar in 1952, the business came under the ownership of Ed’s widow Alice Wackerle, with Harold V. Allbaugh serving as plant manager.

Allbaugh (1903-1980) became the head of the business during its final years in Chicago, introducing some innovations of his own in composite string manufacturing. Once he reached retirement age in the late 1960s, though, it was time to start looking for potential buyers. Allbaugh likely could have sold out to a larger competitor, but instead, he found a rather unlikely bidding group in the form of Super-Sensitive’s personal accountant Vincent Cavanaugh and his son John, who officially took over the firm in 1967.

“You don’t have to have musical talent to make strings,” John Cavanaugh told the Rotary magazine in 2022. “I can’t play, myself. I took six cello lessons in my entire life. The instructor, a cellist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, said to me, ‘Did you know this is out of tune?’”

The Cavanaughs might not have been musicians, but they had some ideas on how Super-Sensitive could start ramping up its production after 25 years adhering to old-fashioned methods.

The Cavanaughs might not have been musicians, but they had some ideas on how Super-Sensitive could start ramping up its production after 25 years adhering to old-fashioned methods.

“When we came into the picture, a violin A-string operator could make 24 dozen strings a day,” John Cavanaugh recalled. “Dad, being an engineer [as well as a CPA], designed new equipment that could make 110 dozen better-quality strings a day.

“In the old days, strings would be made of sheep gut or hog gut. Now an E string can be just a stainless steel or tin-plated wire. An A string is made of nylon. Our D was a layer of nylon with a thin layer of nickel and silver, and our G was made of copper and silver. The lower the note, the thicker the string.”

The Cavanaughs made great strides getting Super-Sensitive’s Red Label strings into school orchestras all over North America. That success, however, soon made the old Division Street plant incapable of keeping up with orders.

In October of 1972, “they filled a pair of tractor-trailer rigs with machinery, wire and assorted other equipment and headed to Florida”—specifically Sarasota—to begin a new era.

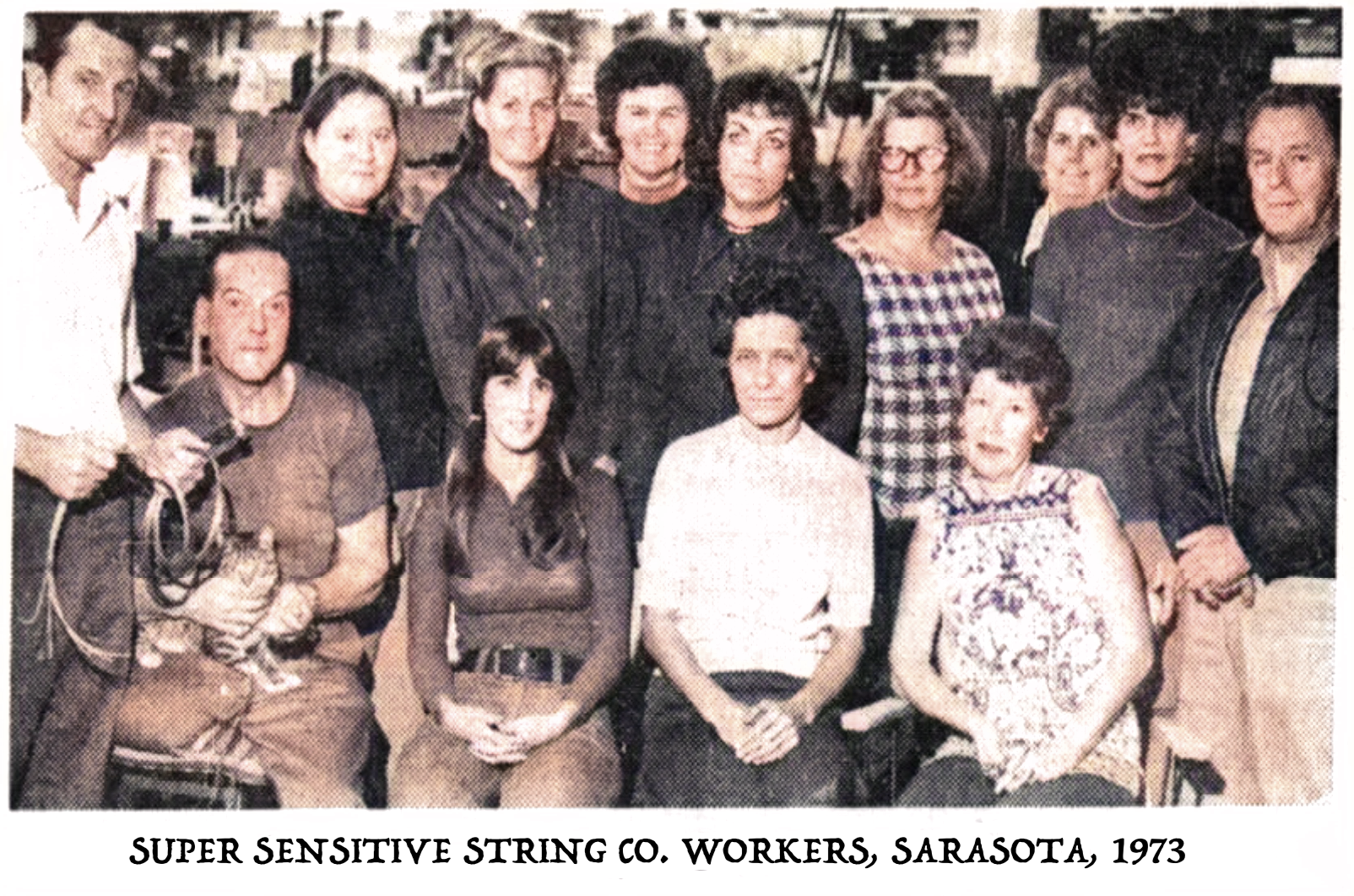

According to a 1973 profile of the business in the St. Petersburg Times, “all of their old employees in Chicago were offered the opportunity to move to Sarasota with the firm. The only one to accept was 20 year-old employee George Ryan.”

The Super-Sensitive Musical String Co. remained a successful, family-operated company for the subsequent 50 years in Sarasota, even expanding into guitar strings and bringing back the popular Black Diamond brand in its later years. Steel strings were now produced in much greater numbers by far larger corporations, however, and after the Covid pandemic took its toll on the business, the decision was made to sell the company to one of the industry giants, D’Addario, in 2021.

Loyalists to the Super-Sensitive brand remain—including those musicians who still favor the quality of the original Chicago strings, which usually get snapped up quickly when they find their way to eBay.

[1998 company catalog cover, featuring artwork by Frank Hopper depicting various users and endorsers of Super Sensitive strings]

Sources:

“Strings and Torrid Temperatures” – Etude, December 1944

“16th Century Art is Heritage of Craftsman” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 28, 1948

“Edward Wackerle, Former Resident, Dies in Chicago” – Jacksonville Daily Journal, Aug 14, 1952

“Super-Sensitive Strikes Profitable Note” – St. Petersburg Times, Dec 26, 1973

Super-Sensitive Musical String Company – 1998 Catalog

Gregor Piatigorsky: The Life and Career of the Virtuoso Cellist, by Terry King, 2010

“Aaron Rosand on Finding the Perfect Set of Strings” – The Strad, Feb 7, 2014

“Celebrated Strings” – Sarasota Herald-Tribune, May 15, 2017

“Made in SRQ: Super-Sensitive Musical Strings” – Sarasota Magazine, Feb 28, 2018

“String Theorist” – Rotary, Feb 2022

I just stumbled upon your article, and I’m truly honored that you featured Super-Sensitive Musical String Co. This company has been a cherished part of my family for over 50 years until I sold it five years ago. My grandfather, Vince, and my father, John, relocated the business to Sarasota in 1972. More than 25 years ago, my father and I made the strategic decision to expand by acquiring Black Diamond Strings, which proudly holds the title of the oldest string company in the USA, established in 1890. If you’d like more details, I would be more than happy to share! I have a lot of stories to tell!

Greetings, While going through my Grandpa’s old violin case I found a set of your strings. The Violin is a Carlo Bergonzi knock off from the 1920’s. Sears would sell violins with famous violin makers names, like, Carlo Bergonze, Antonio Stradivari. to name a couple. The names the printed in the violin. I had the violin appraised a number of years ago and found some of its history. To bad it wasn’t a real Bergonzi, it would have been worth a lot of money.

I have a set of the strings. E -A – D and G in there original packages, (somewhat worn).

I just found this to interesting. I hope your company is doing well.

Thank you for your time.. Wayne Powell

A well-regarded Chicago violin maker, Frank Sindelar, was credited with being the developer of Super Sensitive violin strings. The company relocated to Sarasota, Florida some time ago.