Museum Artifact: Swanberg Mechanical Pencil, c. 1923

Made By: Swanberg MFG Co., 1516 W. Foster Ave., Chicago, IL [Edgewater / Andersonville]

Once seemingly destined to take its place as mankind’s preferred writing stick, the mechanical pencil only ended up writing itself into a corner. No refinement, no reimagining from one generation to the next, could ever quite transition these utensils from the drafting room to the classroom; novelty to norm. Instead, against all rational explanation, most school kids these days are still using the same snappable cedar-wood No. 2’s as their great grandparents.

It’s a far cry from the glorious, sharpener-free future Julius Swanberg was imagining one-hundred years ago.

It’s a far cry from the glorious, sharpener-free future Julius Swanberg was imagining one-hundred years ago.

As a young mechanical engineer and prolific inventor, the Chicago-based, Sweden-born Swanberg tackled the automatic pencil conundrum with a gusto rarely matched by many men before or after him. From his little lab on the North Side, he stripped every existing design to its skeleton, assessed each millimeter with a jeweler’s eyeglass, then worked to fix all inefficiencies. By 1919, he believed he had cracked the code, devising a new blueprint for the mechanical pencil that might finally make it the scrivener’s first choice.

“Due to the fact that suitable wood for pencils is continually becoming more difficult to obtain,” Swanberg wrote in his patent application, “metallic casings are now coming to be quite generally used.

“The metallic casings as heretofore constructed, however, have been so complicated and expensive that the average user could not afford to buy them, or they have been poorly constructed and unsuccessful in operation.

“It is therefore an object of this invention to provide a pencil having a metallic casing which can be economically constructed and which is at the same time durable and positive in operation.”

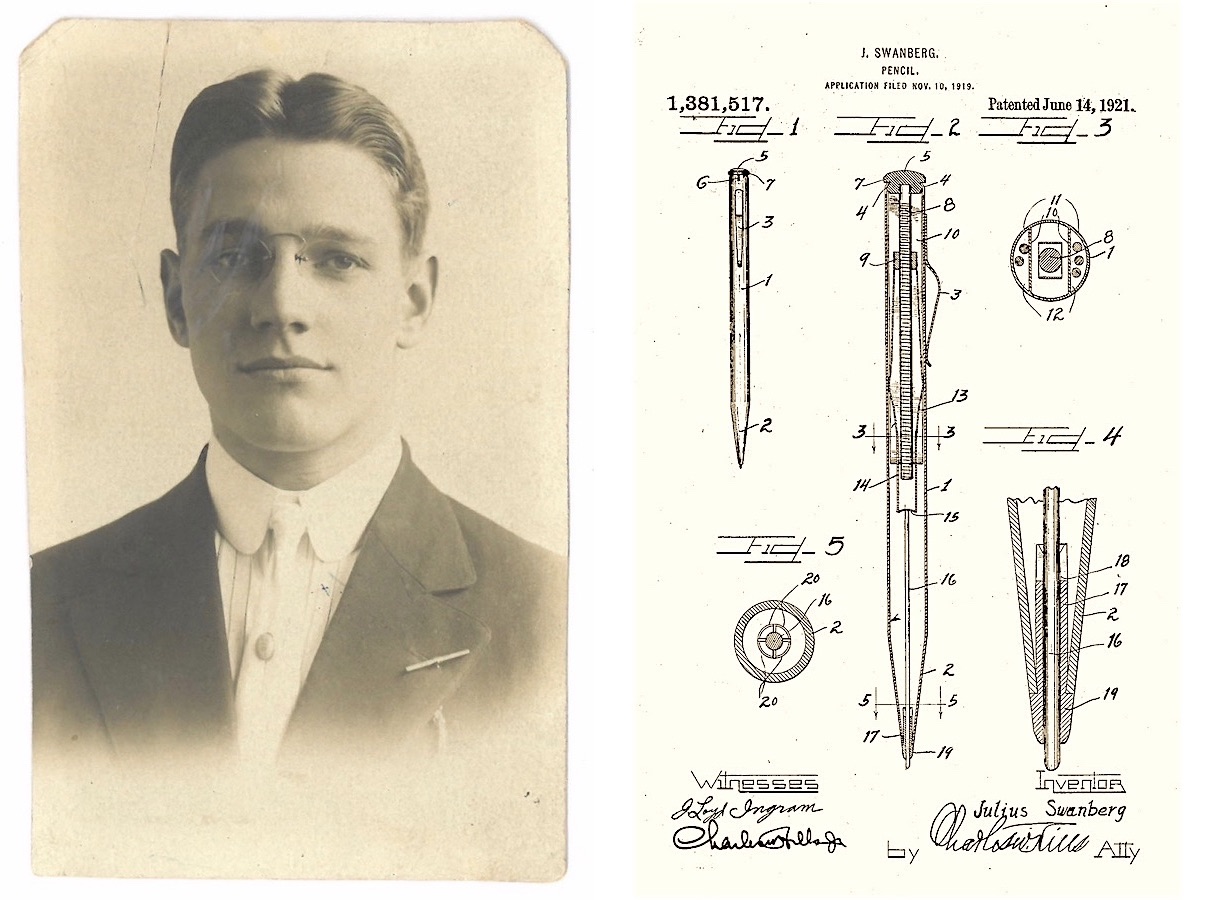

[Julius Swanberg and the pencil patent he applied for in 1919. Swanberg photo, circa 1901, donated by his late daughter Eunice to the Swedish-American Museum in Chicago.]

[Julius Swanberg and the pencil patent he applied for in 1919. Swanberg photo, circa 1901, donated by his late daughter Eunice to the Swedish-American Museum in Chicago.]

Swanberg laid out a few more basic tenets:

⇒ The pencil will never require sharpening.

⇒ The pencil will have a chamber in its casing for storing extra leads.

⇒ The pencil will have a metallic casing that’s adapted to utilize the entire length of the leads.

It took roughly two years for Swanberg to receive approval on his patent, but an awful lot went down in the meantime. Through a head-spinning series of events, his stylish invention went from prototype to mass production, with a national marketing blitz following close behind.

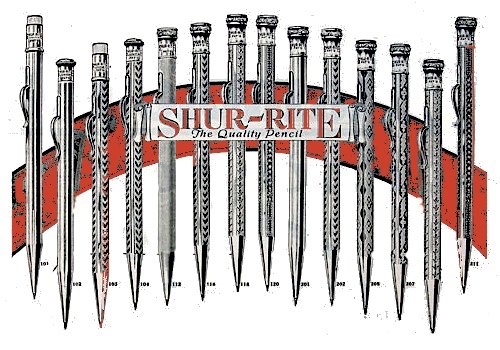

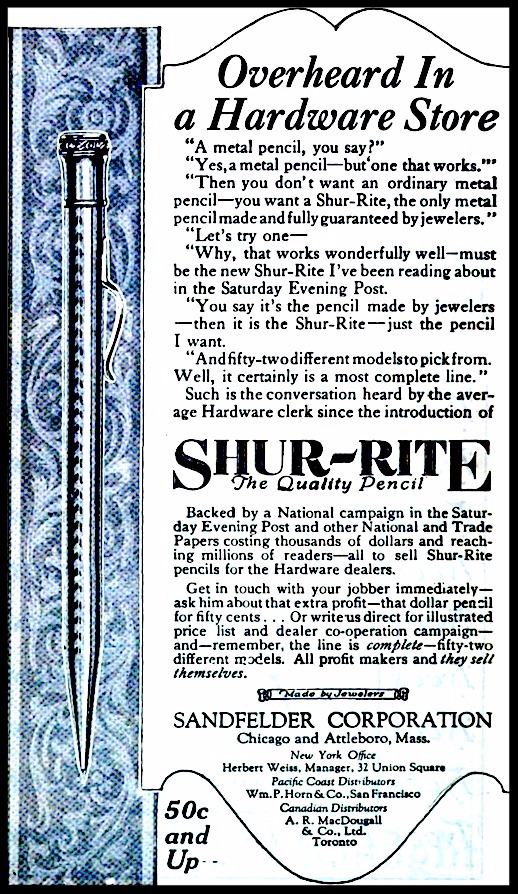

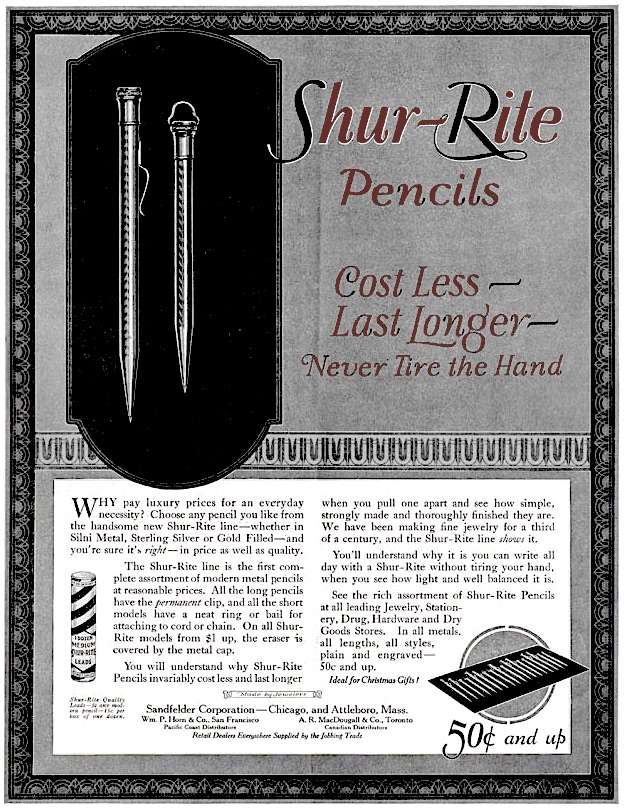

In 1921, the “Shur-Rite” pencil, as it had come to be known, was repeatedly splashed across full-page ads in the Saturday Evening Post—no small task for an upstart—and news of its development spread quickly through the trade magazines of stationers and jewelers, alike [during this period, metal pencils were largely seen as a luxury item, and they looked the part].

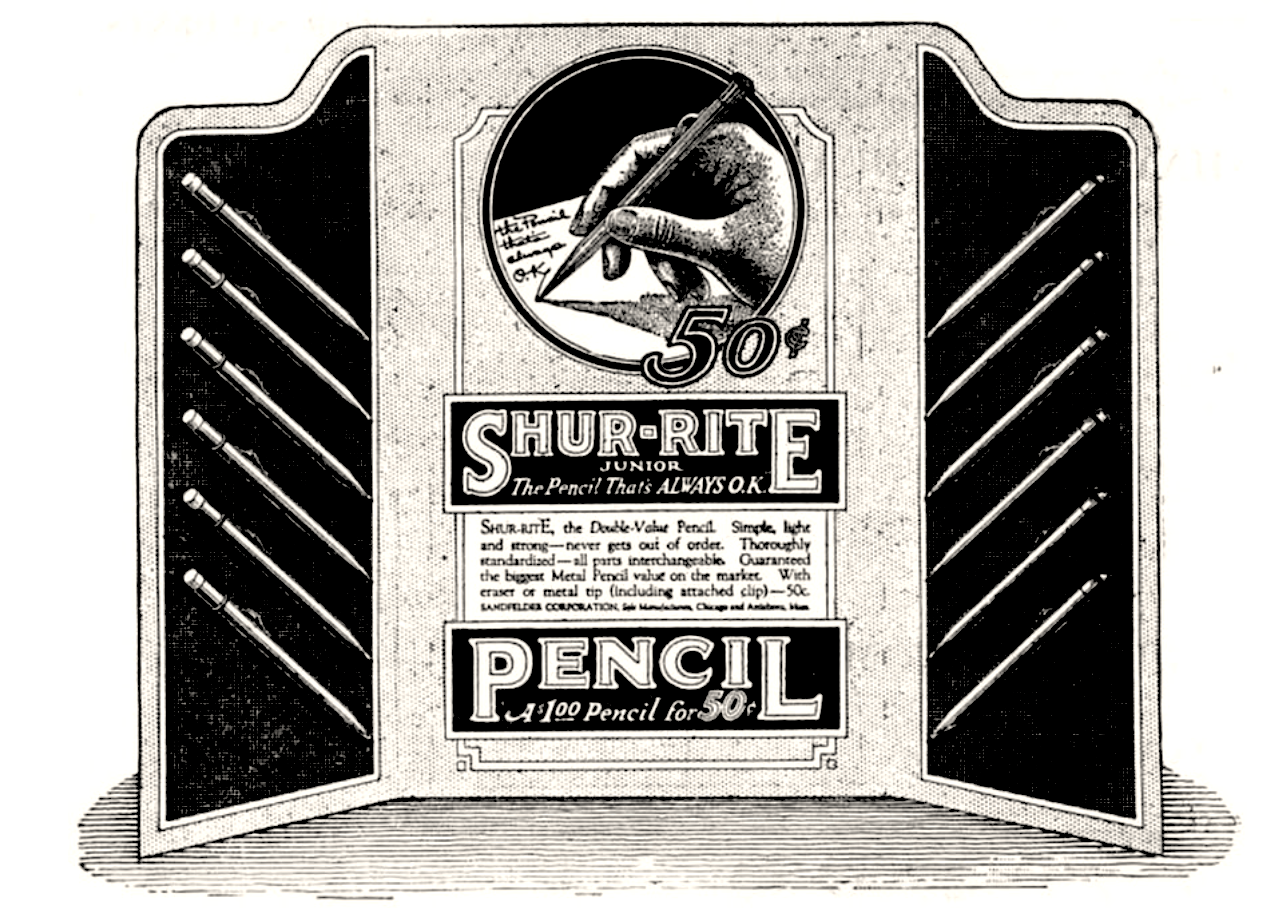

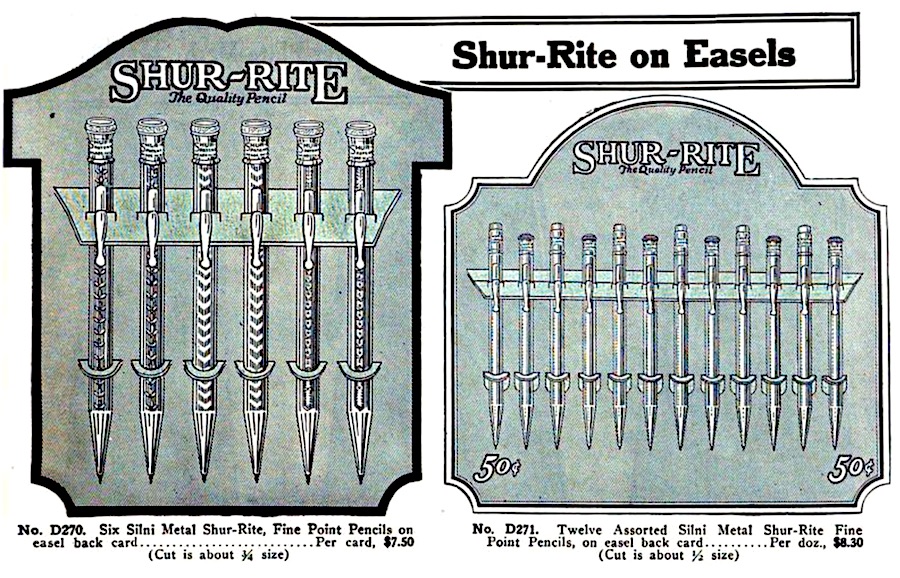

Though Swanberg’s patent was originally assigned to Andersonville’s Fabart Instrument Company (1516 W. Foster Avenue), manufacturing and distribution were swiftly taken over by a jewelry firm called the Sandfelder Corporation, which trademarked the Shur-Rite name and pitched it to the public as “The Quality Pencil.” The Shur-Rite Junior, a smaller model, had a slightly less inspiring slogan—“The Pencil That’s Always O.K.”

Right from the outset, Sandfelder promoted a whopping 52 variations of the muzzle-loader pencil, starting at 50 cents a pop. Users could turn the crown to the right to feed the lead, and replacement leads were available in a distinctive red-striped box.

“Why pay luxury prices for an everyday necessity?” read one Shur-Rite ad. “Choose any pencil you like from this handsome new Shur-Rite line—whether in Silni Metal, Sterling Silver, or Gold Filled—and you’re sure it’s right—in price as well as quality.”

“Why pay luxury prices for an everyday necessity?” read one Shur-Rite ad. “Choose any pencil you like from this handsome new Shur-Rite line—whether in Silni Metal, Sterling Silver, or Gold Filled—and you’re sure it’s right—in price as well as quality.”

“The day of the ‘memorandum pencil’ (convenient but heavy) is past,” read another. “It has served to awaken the public to the advantages of the metal pencil, and paved the way for the day-in-and-day-out pencil—the Shur-Rite—so light as well as balanced that you can write all day long with it and not tire your fingers. . . . Shur-Rite is a fast seller because it makes fast friends. To lift up a Shur-Rite is to own it. To pull one apart and see the astonishingly simple mechanism is to wonder why somebody hasn’t made pencils the Shur-Rite way long ago.”

At just 34 years of age, Julius Swanberg’s ship appeared to have come in. He had solved humanity’s mechanical pencil riddle, creating a cheap metal option that finally functioned properly. His stock had risen from the tiny-font classifieds to the prime real estate of America’s readership. He was going to be the most famous Swedish-American engineer since John Ericsson. . .

. . . And then, by the next year, it was over. The Shur-Rite disappeared from the marketplace in 1922—poof, as if it had never existed. Swanberg, in turn, was left to re-organize his affairs under the banner of his own business, the Swanberg MFG Co., only to see his once celebrated design permanently relegated to the obscure fringes of the industry.

So, what the hell happened here? An unforeseen flaw in the Shur-Rite’s mechanism? Tax fraud? A factory fire? Well, unfortunately, we don’t really know. But just like at any other point in history, the best laid plans of mice and men can end up boiling down to profits. The aggressive promotion of the Shur-Rite pencil sure suggests that its investors were swinging for the fences, and its short shelf-life indicates they may have swung right out of their shoes.

Trying to figure out exactly where things went off the rails may be a hopeless venture, and Jon Veley at The LeadHead’s Pencil Blog has already made his own gallant attempt, bringing far more pencil industry knowledge to the table than I could. What I can do, though, is lay out a bit of a localized “Julius Swanberg Timeline” to help establish the context for the artifact in our museum collection—a Swanberg MFG Co. pencil from the post-Shur-Rite era.

The Ultimate Swanberg Pencil Timeline!

1887 – Julius Swanberg is born in Stockholm, Sweden.

1903 – Arrival in U.S. at age 15.

1910 – Julius marries Hulda Johnson in Chicago [pictured]. Their daughter Eunice is born two years later.

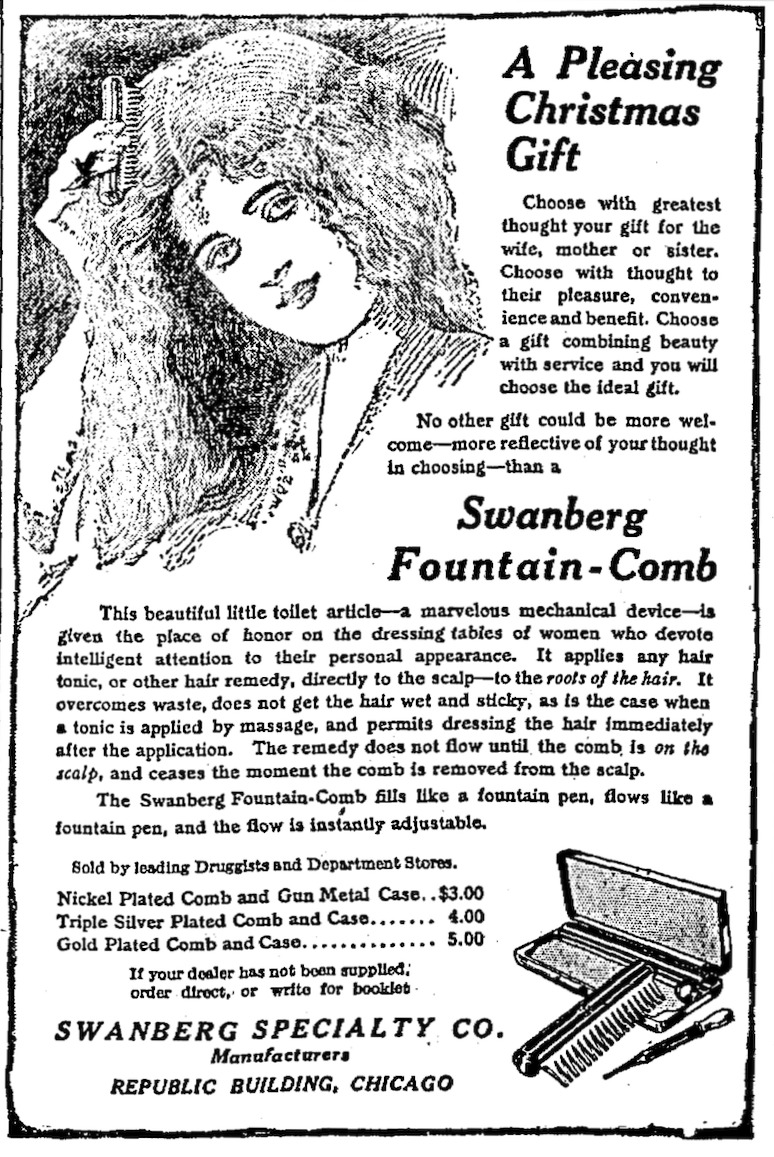

1910-11 – Still in his early 20s, Julius invents and promotes the “Swanberg Fountain Comb”—a liquid dispensing hair brush for “women who devote intelligent attention to their personal appearance.” The Swanberg Specialty Company is launched to help sell it, with an office in the Republic Building at State and Adams. The product appears in regional ad campaigns in 1910 and 1911, but as a prelude to the Shur-Rite experience, it vanishes shortly thereafter.

[Swanberg Fountain Comb advertisement, 1910]

[Swanberg Fountain Comb advertisement, 1910]

1917 – Swanberg is now affiliated with the International Brass & Rubber Works at 1516 W. Foster Avenue in Edgewater, and is advertising his services regularly in the classified section of Popular Mechanics.

[Swanberg’s thank you letter to Popular Mechanics was featured in the magazine’s classified section in the April, 1917 issue]

[Swanberg’s thank you letter to Popular Mechanics was featured in the magazine’s classified section in the April, 1917 issue]

1919 – The International Brass & Rubber Works factory is now the property of the Fabart Instrument Company, presided over by 31 year-old Edward H. Fabrice.

– Swanberg, now 32, starts assigning his new inventions to the Fabart Instrument Company, including fire safety products like an “Automatic Fire Alarm.”

– Swanberg applies for a patent on his first mechanical pencil design. It’s also assigned to the Fabart Instrument Co.

1920 – The Sandfelder Corp., a jewelry firm run by brothers Milton and Sylvan Sandfelder, strike a deal to manufacture and distribute the pencil nationally. They rent out an office in the Heyworth Building at 29 E. Madison Street and employ a team of roughly half a dozen salesmen, mostly from the jewelry trade, to hit the road and spread the word about the Shur-Rite. West Coast and Canadian distribution deals are also worked out independently.

The Sandfelders were from the old school of jewelry slingers. Natives of St. Louis, Milton (b. 1870), and Sylvan (b. 1873) lost their father when they were still kids, and their uncle Samuel Bauman—a successful St. Louis jewelry store owner—took them under his wing. Samuel’s own son Sidney L. Bauman followed in the same line of work, as well, and he joined his cousins in Chicago in 1921 to help with their big metal pencil experiment.

The Sandfelders were from the old school of jewelry slingers. Natives of St. Louis, Milton (b. 1870), and Sylvan (b. 1873) lost their father when they were still kids, and their uncle Samuel Bauman—a successful St. Louis jewelry store owner—took them under his wing. Samuel’s own son Sidney L. Bauman followed in the same line of work, as well, and he joined his cousins in Chicago in 1921 to help with their big metal pencil experiment.

Their strategy, it seems, was to sell the Shur-Rite as a crossover—affordable for the masses but also “the only metal pencil made and fully guaranteed by jewelers.” According to one ad, “the Shur-Rite factory has been fashioning jewelry of the finer sort for nearly forty years.”

From what I can tell, the so-called “Shur-Rite factory” was actually the jewelry manufacturing plant of one of Sylvan Sandfelder’s longtime associates, D. B. Briggs & Co., and it was located not in Chicago or St. Louis, but in Attleboro, Massachusetts. So while the first Swanberg pencil was forged in Chicago, it was likely mass-produced on the east coast.

1921 – Sandfelder rolls out Swanberg’s now patent-approved pencil as the “Shur-Rite,” and creates a far-reaching, high profile ad campaign in both trade magazines and mainstream outlets like the Saturday Evening Post. Some trade articles now describe the related Chicago business as simply the “Shur-Rite Pencil Company.”

1922 – Sandfelder Corp sues the Pencil Products Corp of New York (owned by James Salz). for trademark infringement, due to its attempted use of the name “Salz-Rite” for a pencil. Sandfelder would win the case a year later, but the point was moot.

– All advertising for the Shur-Rite pencil ceases by the end of the year, and its salesmen are re-assigned. Existing Shur-Rites are bought out in bulk, and sometimes rebranded to clear out overstock. Why? Your guess is good as mine.

If you’re wondering, the Sandfelder Corp (aka The Sandfelder Company., aka Sandfelder Bros) survived the Shur-Rite debacle, though they didn’t necessarily learn their lesson. In the late ‘20s, the brothers threw their weight behind a series of gimmicky weight loss belts—the “Beauty Mold Corset” for women, and the “InchesOFF Abdominal Belt” for men. They maintained an office at 100 E. Ohio Street and promoted the weight loss products nationwide in 1930. Like the Shur-Rite, though, the campaign seemed to putter out after a year.

[1930 advertisement for Sandfelder’s “InchesOFF” abdominal belt]

[1930 advertisement for Sandfelder’s “InchesOFF” abdominal belt]

1922 – Julius Swanberg organizes the Swanberg Manufacturing Company at the same address as the Fabart Instrument Company, 1516 W. Foster Ave., with a capital stock of $75,000.

Incidentally, it’s worth noting that the Fabart Instrument Company also resurfaced in later years. In fact, after skipping out on all the pencil mania, the company wound up operating fairly successfully through the Depression and all the way into the 1950s at a small factory in Uptown: 4740 N. Clark Street. They specialized in bottle caps and other assorted “precision equipment.”

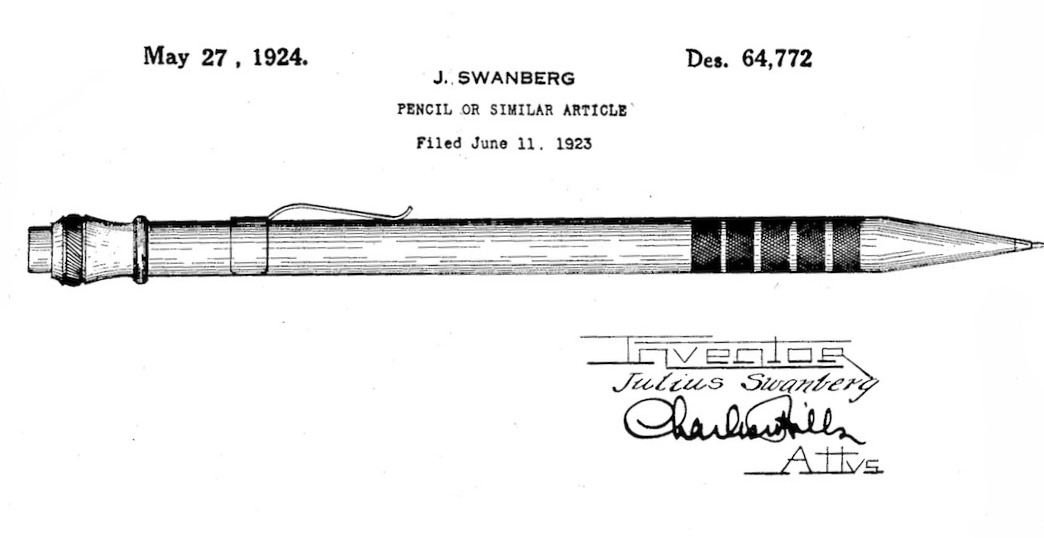

1923 – Swanberg applies for a patent on an updated mechanical pencil design which will be utilized for the pencil in our museum collection.

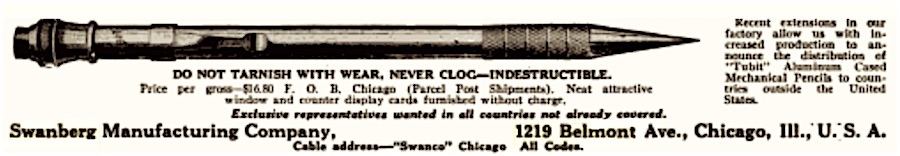

1924 – Swanberg becomes a naturalized U.S. citizen, moves the Swanberg MFG Co. offices to 1219 W. Belmont Avenue.

1924 – Swanberg becomes a naturalized U.S. citizen, moves the Swanberg MFG Co. offices to 1219 W. Belmont Avenue.

1925 – Some ads list Swanberg’s headquarters at 5247 Ravenswood, which suggests he might have been outsourcing the manufacturing of his pencils to the Denoyer-Geppert Company, an Edgewater business he would later work for himself. The Belmont address continues to appear concurrently throughout the 1920s, however.

[Former Swanberg offices at 1219 W. Belmont Ave]

[Former Swanberg offices at 1219 W. Belmont Ave]

1925 – The Swanberg MFG series is promoted in newspaper ads as “The Friendly Pencil,” with variations including the Tubit (25c), Swanberg No. 7 (50c), Swanberg No. 5 (50c), and Swanberg No. 11 ($1).

“There’s a real sense of delight in having a pencil that pleases you,” read one of the 1925 ads. “And the Swanberg does just that! For the perfect balance, beautiful design and pleasing touch will make an immediate hit with you. Once used, the Swanberg will become your life-long friend—for it catches the spirit of writing.

“The mechanical simplicity is an exclusive feature protected by Swanberg patents. It is your insurance against the annoyances of clogging, etc., in the ordinary type. Its perfect operation guarantees life-long satisfaction.”

1928 – Swanberg’s last pencil related patent is approved.

1930 – Census reports list Swanberg as a machinist in the tool & dye industry.

[Julius Swanberg and his daughter Eunice in 1931. From Eunice Swanberg’s donation to the Swedish-American Museum in Chicago]

[Julius Swanberg and his daughter Eunice in 1931. From Eunice Swanberg’s donation to the Swedish-American Museum in Chicago]

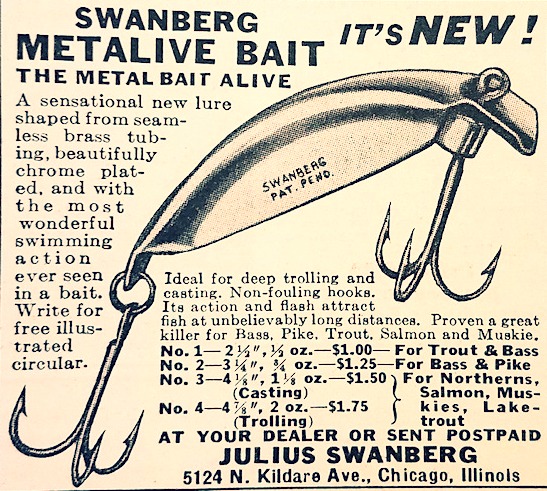

1931 – Switching gears, Swanberg applies for a patent on a fishhook holder.

1939 – He earns another patent for a fish bait plug lure, which is sold during the Depression as the “Swanberg METALIVE Bait.” Julius’s business is listed at his own home address, 5124 N. Kildare Ave., where he lives with his wife and adult daughter.

1942 – WWII draft card now lists Julius Swanberg, 54, as a tool and dye maker with the Denoyer-Geppert Company at Ravenswood Station.

1955 – Swanberg dies at age 68, leaving behind wife Hulda and daughter Eunice.

We conclude the Julius Swanberg story with a clip from a 1921 issue of the Meyer Druggist, assessing the young Swede’s first foray into mechanical pencil design:

“Here at last is a fine-point pencil with a real class to it at a popular price that makes it a fast seller and frequent repeater. Simple, light and strong, it does not get out of order. Thoroughly standardized; all parts interchangeable. Made of Better Metal, with good strong clip attached.”

Ya done good, Julius. Ya done good.

[Julius Swanberg, c. 1930s]

[Julius Swanberg, c. 1930s]

Sources:

Swanberg: The Friendly Pencil – Waco News-Tribune, April 19, 1925

“These Shur Were the Best They Made” – LeadHead’s Pencil Blog, 2013

“Heyworth Building” – Chicago Central Business and Office Directory, 1922

Jeweler’s Circular, Vol. 83, Issue 2, Nov. 1921

Pencil Patent US1381517 A – Julius Swanberg, 1919

Popular Mechanics, Nov 1909, April 1917

Chicago Tribune, December 20, 1910

Meyer Druggist, Vol. 42, 1921

Geyer’s Stationer, July 14, 1921

Saturday Evening Post, January 14, 1922 / Feb 11, 1922

American Stationer and Office Outfitter, July 2, 1921

Good Hardware, Vol. 3, 1921

I have in my possession a Swanberg mechanical pencil. I will add that I’m agreeable to selling it if you’re still looking to aquire one. KEITH

A very interesting find. I would love to obtain one of these pencils. It would be a great conversation piece in my family. Who knows, Julius could be a relative.

Jeffery,

Check Ebay. The pencils come up for auction periodically.