Museum Artifact: “Hercules” Telephone Box, c. 1908

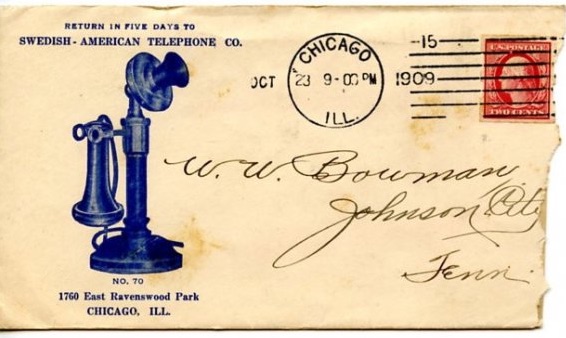

Made By: Swedish-American Telephone Co., 5235 N. Ravenswood Ave., Chicago, IL [Edgewater]

There aren’t a lot of Swedish things left in Chicago’s original Swedish neighborhood these days. In just the past few years, Andersonville has lost its beloved Swedish Bakery, along with Ann Sather’s restaurant, Erickson Jewelers, Erickson’s Deli (no relation), and even the old iconic neighborhood water tower—painted for decades in the blue and gold of the Motherland (a facsimile has since been installed). If you want to get your Swede on in Andersonville, however, fear not, for you can still visit the sad mannequins at the Swedish-American Museum, sip some glogg at Simon’s Tavern, or have a gander at a true Chicago industrial landmark, the Swedish-American Telephone Company Building!

“Our immense plant in Chicago employs only the most modern methods of manufacture known,” the Swedish-American Telephone Co. declared in a 1908 edition of its self-published magazine, Rural Telephone. “Located, as we are, in a field like Chicago, we are enabled to select our skilled mechanics, specialists, and experts from a vast array of the finest talent in the world. Labor of this kind may cost a trifle more than it does in small towns, but it proves vastly more satisfactory in the end.”

“Our immense plant in Chicago employs only the most modern methods of manufacture known,” the Swedish-American Telephone Co. declared in a 1908 edition of its self-published magazine, Rural Telephone. “Located, as we are, in a field like Chicago, we are enabled to select our skilled mechanics, specialists, and experts from a vast array of the finest talent in the world. Labor of this kind may cost a trifle more than it does in small towns, but it proves vastly more satisfactory in the end.”

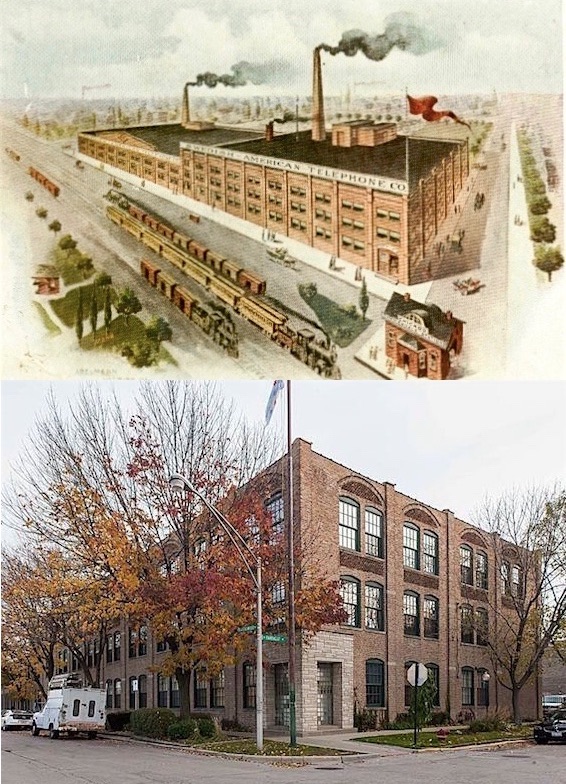

Located just west of Andersonville’s main Clark Street drag, at the corner of Farragut and North Ravenswood, the “immense” factory space mentioned above was the the Swedish-American Telephone Company’s home from 1905 to 1923. For an additional 60 years after that, it served as the headquarters of the Denoyer-Geppert Company, a map and globe maker—hence the inspiration for the building’s current residential identity as the “Map Factory Lofts.” As far as the National Park Service is concerned, though, it’s still officially the Swedish-American Telephone Co. Building; part of the National Registry of Historic Places. It’s a status the building earned not only for its role in the growth of the Andersonville / Edgewater community, but for its unique architecture—which exhibits “significantly more concern for facade composition than the standard industrial building of its day . . . revealing a certain pride of ownership.”

[The Swedish-American Telephone Co., c. 1910 and 2016]

[The Swedish-American Telephone Co., c. 1910 and 2016]

The founders of the Swedish-American Telephone Co. didn’t actually have anything to do with the construction of their factory (it was originally built by and for the F.S. Betz medical supply company in 1895), but the whole “pride of ownership” concept likely would have resonated with the various craftsmen in their employ.

Much like the esteemed reputation of “German engineering” in the auto industry, the Swedes were widely viewed—accurately or not—as the masters of “telephony” at the turn of the century. This started with Sweden’s fast development in fully networking its own cities in the late 1800s, and was furthered by the success of international companies like the Ericsson Telephone Co. (based in Stockholm) and Stromberg-Carlson (a Chicago company headed by Swedish-Americans). Early telephones benefited from any association with Swedish expertise. And so, when the Swedish-American Telephone Company was founded in 1899, its name was more strategic than it was self descriptive.

That’s not to say it was false advertising. There were certainly Swedes involved in the company, especially in the factory workforce. But not everybody in the head office was flying the Nordic Cross.

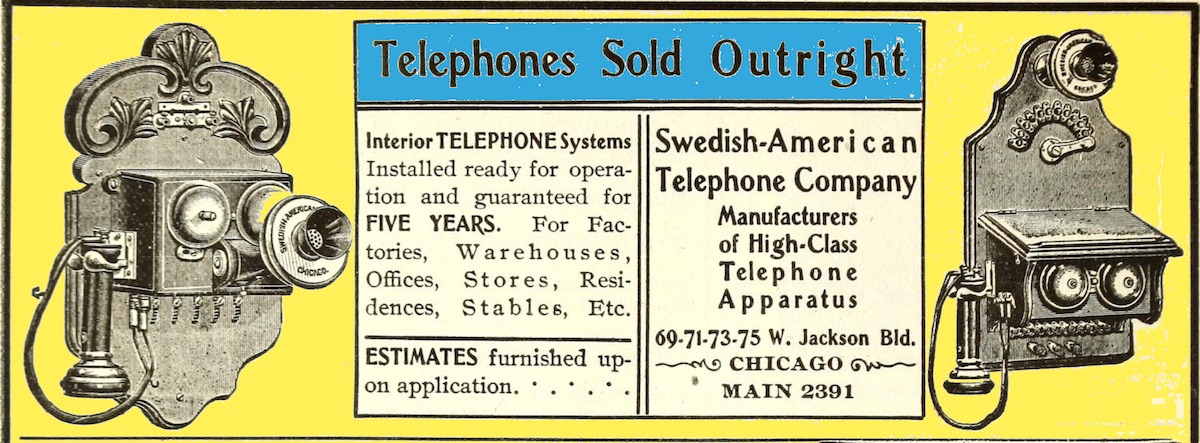

[Early Swedish-American Telephone Co. ad from 1901]

[Early Swedish-American Telephone Co. ad from 1901]

The Players

In many respects, the S.A.T.C. was actually a pretty late entry into Chicago’s battle royale of independent telephone makers. When Alexander Graham Bell’s original phone manufacturing patent expired back in 1894, it launched a torrent of new start-up companies, not unlike the dot-com bubble a century later. The aforementioned Stromberg-Carlson was out ahead of the field, while the Chicago Telephone Supply Co. (1896) and Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Co.(1897) were among the many to follow on its heels.

While these companies were initially “independent” in terms of their separation from the mighty Bell System networks, nobody was really flying completely solo. The chaos of a rapidly evolving new technology—and industry— led to a confusing mess of cross-pollination and precarious allegiances. A company like Swedish-American, for example, made its own apparatuses, but also imported some Ericsson components from Sweden, which in turn, they could swap for some additional pieces from local friend-rivals like Stromberg-Carlson. Similarly, the men and women involved in the Chicago telephone industry—from the technicians and salesmen up to the owners and managers—were routinely playing musical chairs, jumping from one company to another or sometimes balancing several at the same time; waiting to see which had the staying power.

While these companies were initially “independent” in terms of their separation from the mighty Bell System networks, nobody was really flying completely solo. The chaos of a rapidly evolving new technology—and industry— led to a confusing mess of cross-pollination and precarious allegiances. A company like Swedish-American, for example, made its own apparatuses, but also imported some Ericsson components from Sweden, which in turn, they could swap for some additional pieces from local friend-rivals like Stromberg-Carlson. Similarly, the men and women involved in the Chicago telephone industry—from the technicians and salesmen up to the owners and managers—were routinely playing musical chairs, jumping from one company to another or sometimes balancing several at the same time; waiting to see which had the staying power.

It was into this chaotic scene that the Swedish-American Telephone Co. emerged, and it’s why pinpointing the roles of each man involved can prove challenging. No two sources seem to tell the tale the exact same way, but I have done my best to identify what we’ll call the “key players” in 1899.

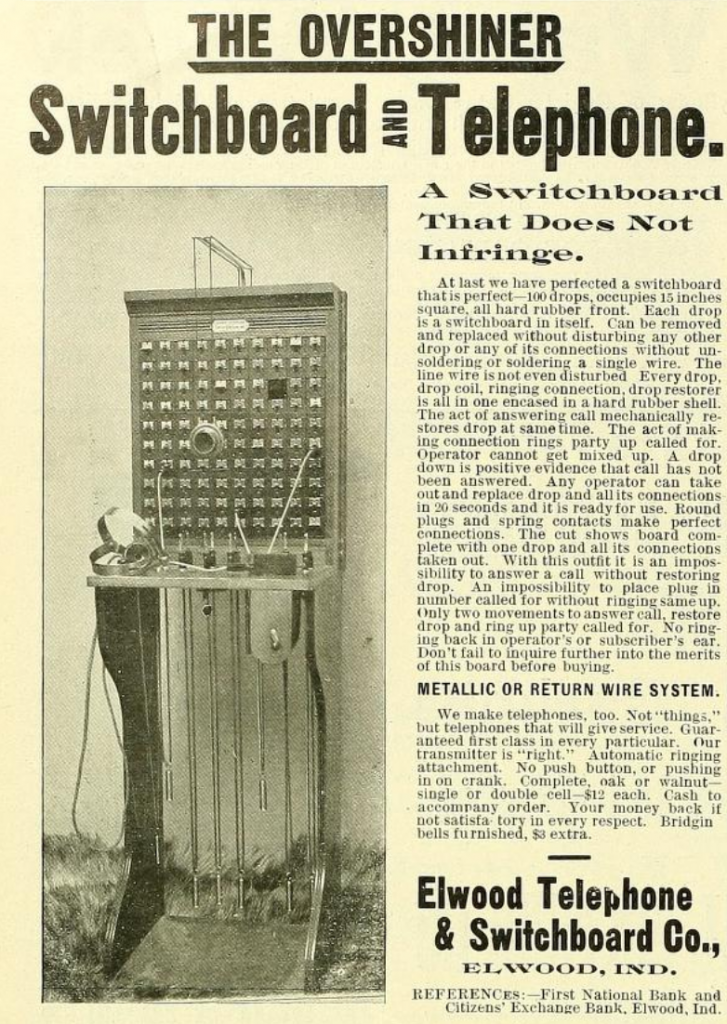

E.B. Overshiner, President – A fourth generation American of German ancestry, SATC’s first president, Ellsworth B. Overshiner, was about as Swedish as a hamburger. But he certainly had the chops to run a telephone firm. For the four years prior, the 32 year-old had already been in business with his father James Overshiner (a former wagon manufacturer during the Civil War) running the Elwood Telephone Co. in central Indiana. There, E.B. gained a ton of hands-on experience building phone components and the network systems themselves. Probably more significant than his technical prowess, however, were his people skills. A graduate of the University of Kentucky and a former employee of the Pennsylvania Railway, Overshiner had developed the ability to charm coal miners and corporate tycoons with equal aplomb, using the classic “shoot from the hip” approach that still mesmerizes gullible types to this day. It worked to his advantage for more than a decade with Swedish-American. Unfortunately, Overshiner’s outward folksiness masked an easily unhinged individual who eventually couldn’t outrun his demons (as you’ll soon see).

E.B. Overshiner, President – A fourth generation American of German ancestry, SATC’s first president, Ellsworth B. Overshiner, was about as Swedish as a hamburger. But he certainly had the chops to run a telephone firm. For the four years prior, the 32 year-old had already been in business with his father James Overshiner (a former wagon manufacturer during the Civil War) running the Elwood Telephone Co. in central Indiana. There, E.B. gained a ton of hands-on experience building phone components and the network systems themselves. Probably more significant than his technical prowess, however, were his people skills. A graduate of the University of Kentucky and a former employee of the Pennsylvania Railway, Overshiner had developed the ability to charm coal miners and corporate tycoons with equal aplomb, using the classic “shoot from the hip” approach that still mesmerizes gullible types to this day. It worked to his advantage for more than a decade with Swedish-American. Unfortunately, Overshiner’s outward folksiness masked an easily unhinged individual who eventually couldn’t outrun his demons (as you’ll soon see).

A.V. Overshiner – Ellsworth’s kid brother Arthur, born in 1872, was also working in the phone business in Indiana for several years before following his bro to Chicago to start the SATC. According to an account in Telephony magazine, A.V.’s role was more on the marketing end of things at first. “He spent considerable time on the road working up business, and a little later on became sales manager. The business continued to grow and the force was correspondingly increased. Mr. Overshiner handled all sales correspondence and advertising.” He eventually was elevated to Vice President.

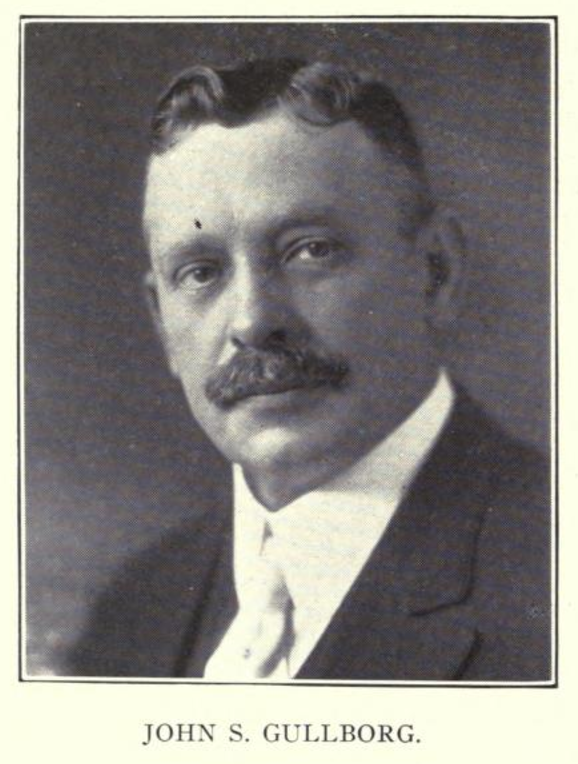

John S. Gullborg – Born in Sandhem, Sweden, in 1863, John Gullborg brought the Swedish authenticity to the Swedish-American Telephone enterprise. As such, he is often cited as the co-founder of the company, alongside E.B. Overshiner. How active a role he actually played in the day-to-day operations of the firm, however, are harder to say. Gullborg had paid his dues working up the Chicago industrial ladder, putting in years at the Gormley & Jeffrey bicycle factory, Excelsior Iron Works, Featherstone & Sons ice machine plant, and eventually his own start-up, the Gullborg Bicycle Co. (est. 1895). The SATC was really his first serious foray into the telephone business, but he caught on quickly, eventually leaving after three years to join the larger Stromberg-Carlson Co. From there, Gullborg had great success, collecting more than 50 patents in both the telephonics and automotive industries, highlighted by a new type of automatic die-casting machine that made him a fortune. Gullborg’s biggest contribution to the Swedish-American Telephone Co., in the long run, was selling them his Jackson Blvd. factory—the company’s downtown home before moving up to Andersonville.

John S. Gullborg – Born in Sandhem, Sweden, in 1863, John Gullborg brought the Swedish authenticity to the Swedish-American Telephone enterprise. As such, he is often cited as the co-founder of the company, alongside E.B. Overshiner. How active a role he actually played in the day-to-day operations of the firm, however, are harder to say. Gullborg had paid his dues working up the Chicago industrial ladder, putting in years at the Gormley & Jeffrey bicycle factory, Excelsior Iron Works, Featherstone & Sons ice machine plant, and eventually his own start-up, the Gullborg Bicycle Co. (est. 1895). The SATC was really his first serious foray into the telephone business, but he caught on quickly, eventually leaving after three years to join the larger Stromberg-Carlson Co. From there, Gullborg had great success, collecting more than 50 patents in both the telephonics and automotive industries, highlighted by a new type of automatic die-casting machine that made him a fortune. Gullborg’s biggest contribution to the Swedish-American Telephone Co., in the long run, was selling them his Jackson Blvd. factory—the company’s downtown home before moving up to Andersonville.

S.W. Moon – “Among the pioneers in the independent telephone field,” an 1899 issue of Telephone Magazine reported, “probably few are better and more favorably known than Mr. S.W. Moon, who until recently held the position of general manager for the American Electric Telephone Company, from where he resigned to take the active management of the recently incorporated Swedish American Telephone Company of Chicago.” S.W. Moon was a major get for the Overshiner brothers, as they’d managed to convince the noted battery expert to jump ship from the established American Electric firm. He was a fellow Indiana boy (American Electric was based in Kokomo, IN), so that may have helped their cause. For whatever reason, Mr. Moon is rarely mentioned in most modern summations of the SATC’s formation, but he seemed to be a pivotal figure in those first few years.

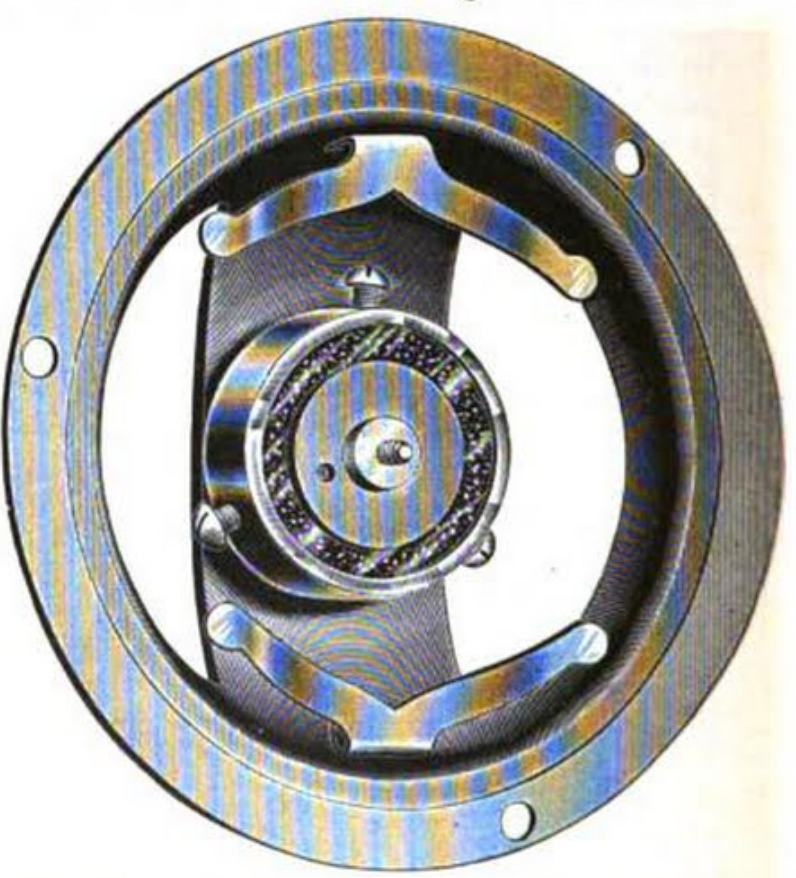

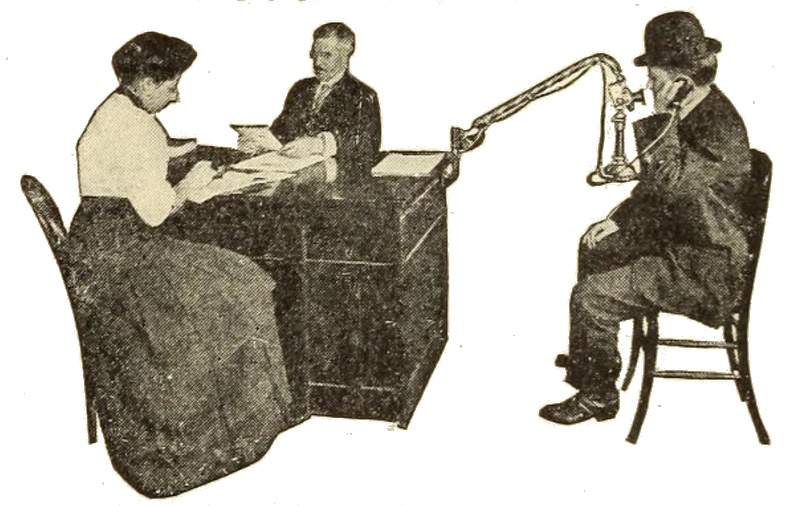

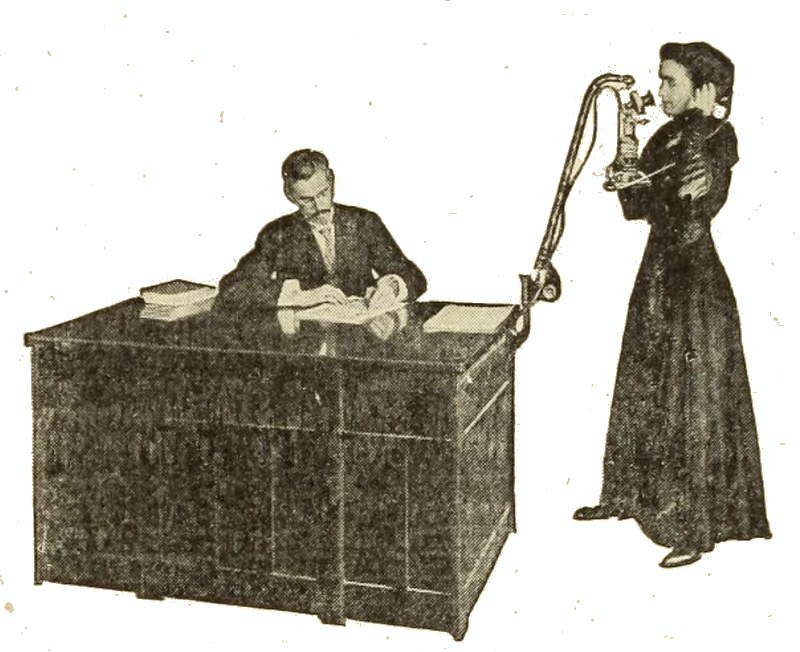

Tiodolf Lidberg – Mr. Lidberg really built the foundation for SATC’s success when he agreed to assign the patents for his groundbreaking new transmitter design [pictured] to the fledgling company. In return, E.B. Overshiner made Tiodolf a VP and Superintendent of the Swedish-American factory. Telephone Magazine claimed the Lidberg transmitters “mark an epoch in the development of modern telephone construction. . . The instrument is highly sensitive to vibration, is delicately responsive, and, like a tuned instrument, its responses are harmonious with the producing cause. . . . The [Swedish-American Telephone Co.] is the first independent manufacturer to place on the market a transmitter that is absolutely superior to the American Bell long distance.” By 1905, Telephony added that “[Mr. Lidberg] is recognized as one of the leading telephone engineers of the United States, and the successful operation of the [Swedish-American] factory is almost entirely due to his efforts.”

Tiodolf Lidberg – Mr. Lidberg really built the foundation for SATC’s success when he agreed to assign the patents for his groundbreaking new transmitter design [pictured] to the fledgling company. In return, E.B. Overshiner made Tiodolf a VP and Superintendent of the Swedish-American factory. Telephone Magazine claimed the Lidberg transmitters “mark an epoch in the development of modern telephone construction. . . The instrument is highly sensitive to vibration, is delicately responsive, and, like a tuned instrument, its responses are harmonious with the producing cause. . . . The [Swedish-American Telephone Co.] is the first independent manufacturer to place on the market a transmitter that is absolutely superior to the American Bell long distance.” By 1905, Telephony added that “[Mr. Lidberg] is recognized as one of the leading telephone engineers of the United States, and the successful operation of the [Swedish-American] factory is almost entirely due to his efforts.”

So, with this motley crew in place, Swedish-American hit the ground running, moving from a tiny plant in Old Town (around what is now 1713 N. Wells St.) to a medium sized downtown building at 73 W. Jackson Blvd, then basically across the street to the former Gullborg factory at 88 W. Jackson Blvd (today known as 555 W. Jackson, and also still standing).

[555 W. Jackson Blvd., home of Swedish-American from 1902-1905, and largely unchanged today]

[555 W. Jackson Blvd., home of Swedish-American from 1902-1905, and largely unchanged today]

Boom Years

“The Swedish American Telephone company started business within a year but the progress of this enterprising concern has been phenomenal,” Western Electrician reported in 1900. “The motto of the company is, ‘The very highest class of workmanship at reasonable prices.’”

By 1905, the trajectory was similarly upwards and outwards.

“The Swedish American Telephone Company started in business in a small way five years ago and is now ranked as one of the best established industries of its class in the country,” Telephony claimed. “This growth has been made in spite of close competition with the largest and most prosperous telephone manufacturing concerns. Their success is due because of the genuine merit and excellence of their apparatus during times when many companies were sacrificing the quality of their apparatus in order to meet competition or to increase their profits.”

After little more than two years at the second Jackson Blvd. plant, the SATC finally found its permanent home by the end of ’05, taking over the previously discussed complex at what is today 5235 N. Ravenswood Ave. While there was already a growing Swedish population in Edgewater at the time, the arrival of the Swedish-American Telephone Co. really helped solidify the area (and the sub-section of Andersonville, in particular) as Chicago’s Swedish stronghold. The neighborhood developed rapidly over the next two decades, with just about everybody either working for the telephone firm or knowing someone who did.

The factory itself took up a whole city block, and it looked good doing so. In its own literature, SATC called the Ravenswood plant, “without a doubt the most modern and complete telephone manufacturing plant in the world. Each department is under the direct supervision of practical, experienced, and skilled men. Each department is also provided with testing apparatus, and the experts that have charge of the testing departments require accuracy and uniformity in every detail. In dealing with the Swedish American you can be assured of getting 100 cents value for every dollar invested and instruments that will last a lifetime.”

The factory itself took up a whole city block, and it looked good doing so. In its own literature, SATC called the Ravenswood plant, “without a doubt the most modern and complete telephone manufacturing plant in the world. Each department is under the direct supervision of practical, experienced, and skilled men. Each department is also provided with testing apparatus, and the experts that have charge of the testing departments require accuracy and uniformity in every detail. In dealing with the Swedish American you can be assured of getting 100 cents value for every dollar invested and instruments that will last a lifetime.”

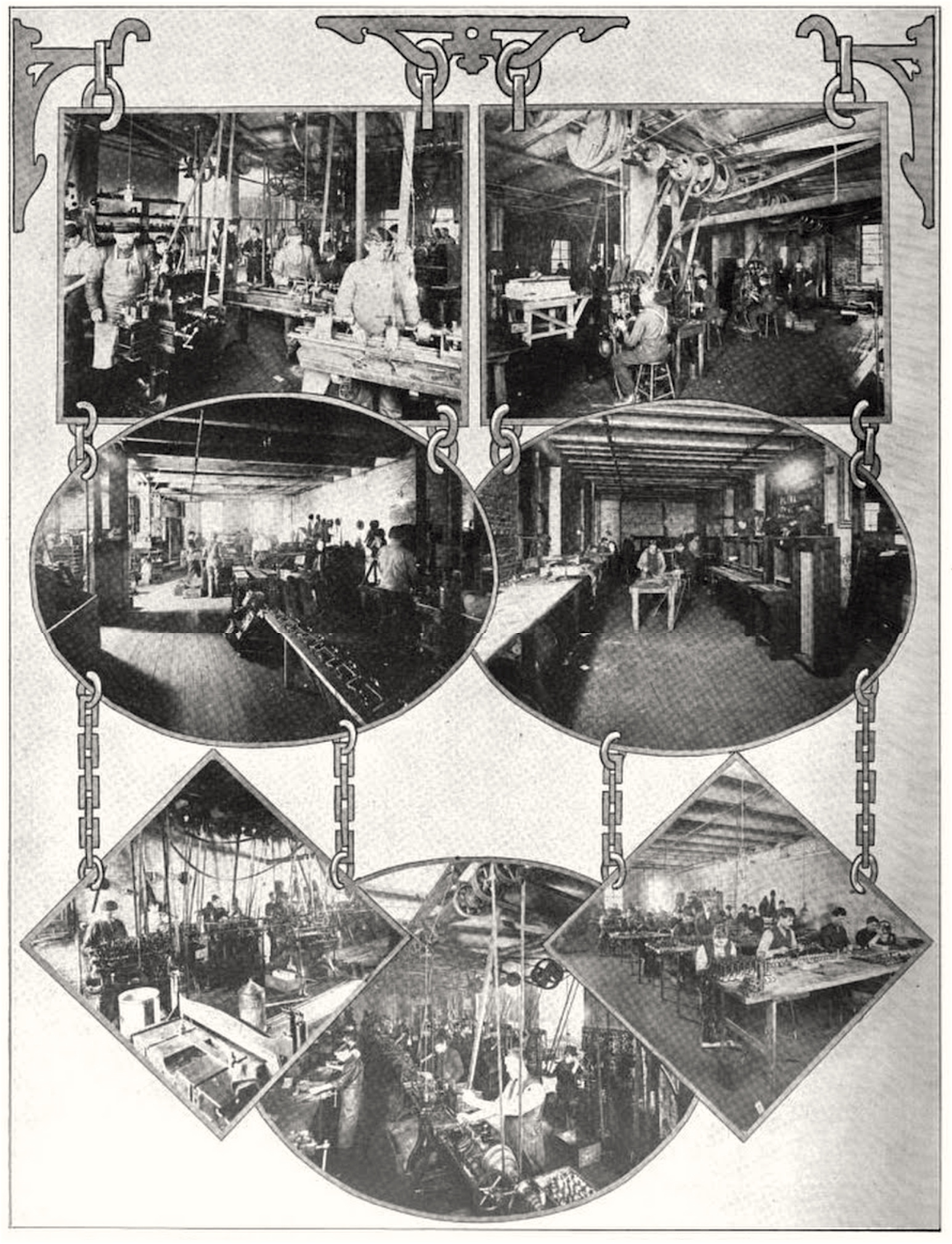

Overshiner and Lidberg set up portions of the plant for every part of the phone-making process—an electrical laboratory, a testing department, assembly, screw machining, punch press, switchboard manufacturing, bushing & polishing, plating, stockroom, shipping, and even a separate air-tight room for the transmitter department; keeping dust and dirt away from Lidberg’s sensitive instruments.

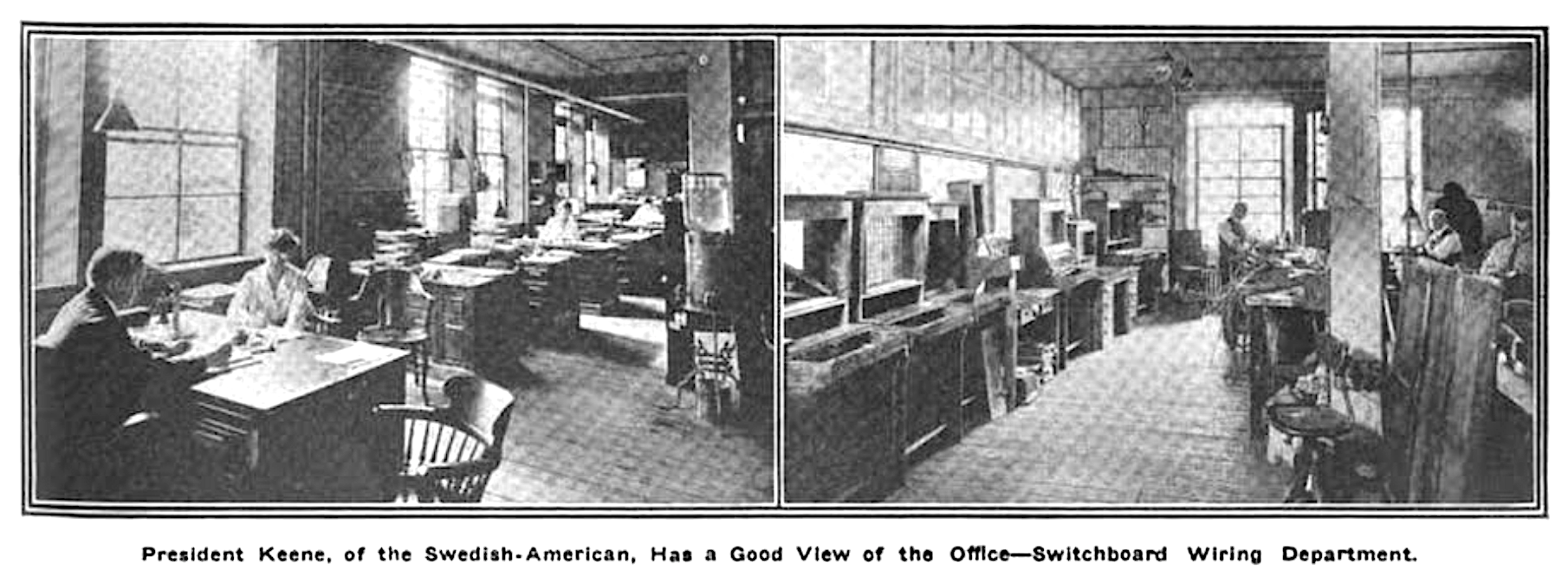

[Inside the Swedish-American factory, c. 1905]

[Inside the Swedish-American factory, c. 1905]

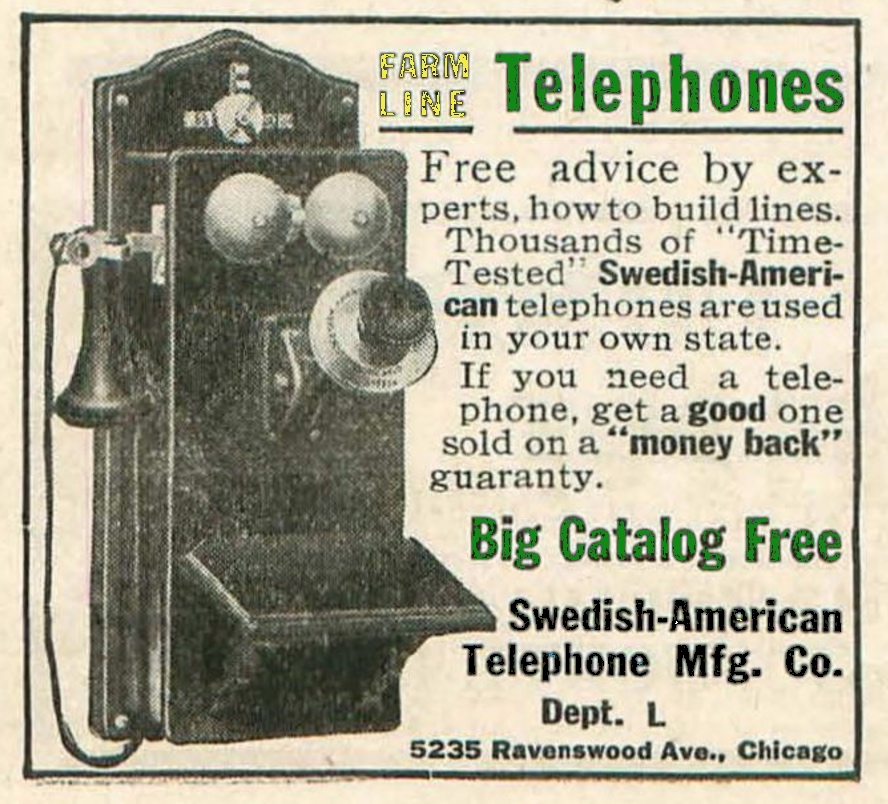

While located in the fastest growing city in America, working out of a state-of-the-art urban manufacturing plant, the Swedish-American Telephone Co.—somewhat ironically—established itself as a leader in “rural telephones.” This included serving clientele like farmers from Overshiner’s old Indiana stomping grounds, as well as the railway workers he’d established connections with during that phase of his career.

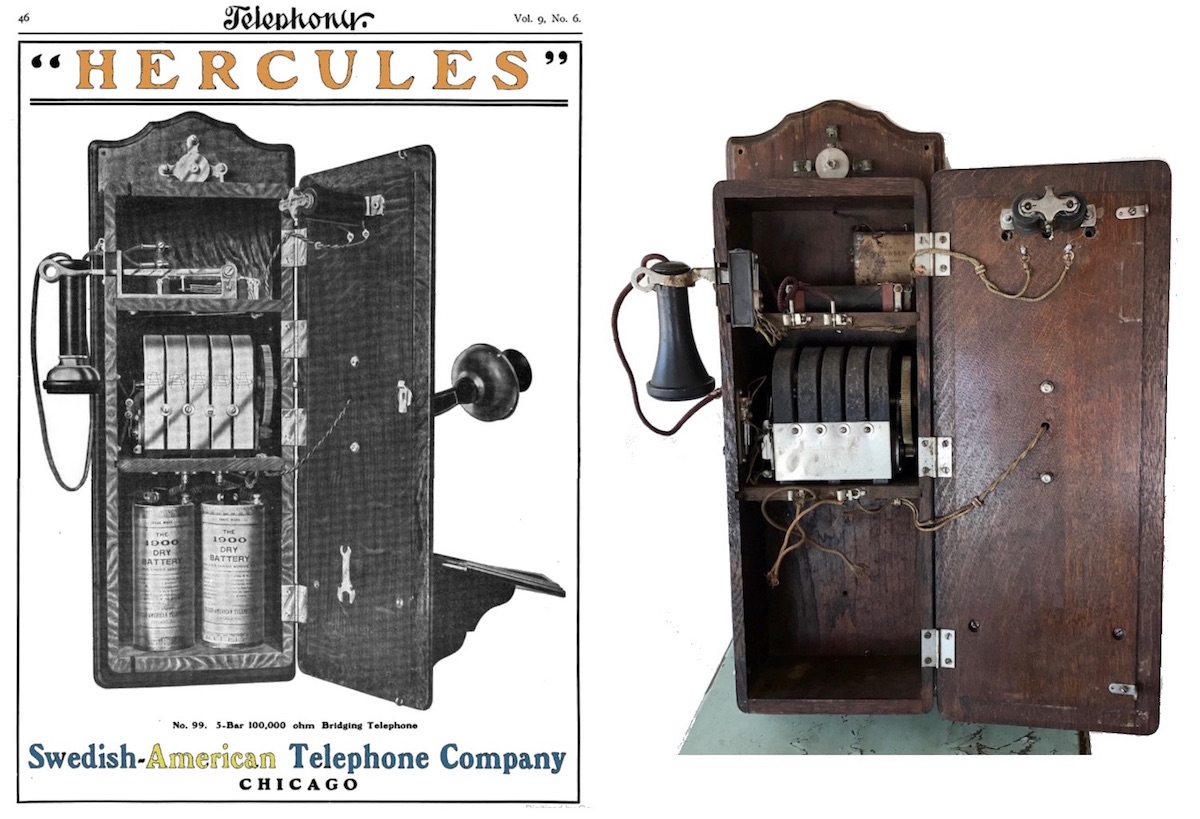

“The Swedish American Telephone Company makes a specialty of manufacturing equipment for small community exchanges, party and rural lines,” Telephony reported. “The demand for their well known ‘Hercules’ type of bridging telephone is especially heavy.”

[1908 Hercules ad vs. the our museum Hercules, 2017]

[1908 Hercules ad vs. the our museum Hercules, 2017]

Hercules! Hercules!

Hey, that’s the very brand of Swedish-American telephone in our museum collection! As you can tell from the photos, the century-old phone box includes plenty of self-identifying marks, from the green “Hercules” and SATC Lions logos on the front oak panel to the Swedish-American name on the metal plating of the transmitter and the interior magneto. There is a patent date listing of 1903, as well, but the condenser is stamped as having been tested in 1916, so the whole unit was put together some time between those dates.

SATC had a number of brands it developed (“Peerless” and “New Swedish Beauty” were others), but Hercules seemed to be the most popular.

“The unusual strength and durability of this instrument appeals to all telephone men,” Telephony elaborated, “and they unhesitatingly pronounce it an ideal telephone for heavily loaded lines and severe service. . . . There probably are more Hercules telephones used on rural lines than any other three makes, is their claim.”

It’s not really clear if was the “telephone men” or the Swedish-American Telephone Co. making that claim, but either way, it certainly wasn’t unusual for SATC to go toot its own horn.

Dial M for Marketing

Like many businesses of its era, SATC wasn’t content to merely advertise in the usual trade magazines. They wanted to control the narrative. As such, they put out their own publications (as mentioned a couple times already), which were quite intentionally made to look just like any other third party journal.

At an industry conference in 1903, E.B. Overshiner was directly challenged over the ethics of releasing ads masquerading as magazines, referring specifically to SATC’s first self-made periodical, “Sound Waves.”

Overshiner, after lightening the mood with some insider jokes that had the room cracking up, replied that such publications were “a strictly legitimate way of advertising. The Deere Company and the McCormick Reaper and Harvester Company do the same thing, and no one thinks of criticizing them for it. We do not charge for the papers. If those who receive them do not want to read them, they needn’t.”

Overshiner, after lightening the mood with some insider jokes that had the room cracking up, replied that such publications were “a strictly legitimate way of advertising. The Deere Company and the McCormick Reaper and Harvester Company do the same thing, and no one thinks of criticizing them for it. We do not charge for the papers. If those who receive them do not want to read them, they needn’t.”

Interestingly, Overshiner discontinued “Sound Waves” just weeks after that event. But, a short time after that, he started up a new journal, “Rural Telephone,” which served the identical purpose.

Here, SATC could blur the line between company catalogs and trade tabloids. There might, for example, be an educational article for small-town readers about how to organize a rural telephone line. But halfway through said article would be the key advice: “When ready for telephones, order the No. 99 Hercules or No. 88 New Swedish Beauty from Swedish-American Telephone Company. These instruments are built especially for rural lines, and are unquestionably the best instruments for this purpose on the market.”

[1904 Swedish-American advertisement]

[1904 Swedish-American advertisement]

Overshiner Goes Overboard

As he found greater success, E.B. Overshiner only became more outspoken and more of a shameless self promoter. While SATC’s magazines were describing the company as “the largest manufacturer of magneto and long distance telephone apparatus in the world,” Overshiner was impatiently acquiring and juggling a slate of other business ventures—the Dominion Telephone MFG Co. in Canada, General Radio Equipment Company of Chicago, Popular Electricity Publishing Company, Vit Talking Machine Co., and more. In 1910, he started the American Wagon Company out of the Ravenswood plant (honoring his dad’s old line of work), and—in an attempt to get investors on board—purchased full-page ads in magazines like The Railroad Telegrapher, trying to sell his old blue-collar brethren on a get-rich-quick scheme.

“A new Million Dollar corporation which I am heavily interested in and President and Director of, will be one of the greatest and best paying Industrial Corporations in the United States and its stock will advance many times in value,” Overshiner wrote. “I will make every railroad man that joins me in this new enterprise some real money in sums worth while, and on an investment of only fifty dollars and five months to pay it in.”

“A new Million Dollar corporation which I am heavily interested in and President and Director of, will be one of the greatest and best paying Industrial Corporations in the United States and its stock will advance many times in value,” Overshiner wrote. “I will make every railroad man that joins me in this new enterprise some real money in sums worth while, and on an investment of only fifty dollars and five months to pay it in.”

The American Wagon Company never remotely approached those lofty predictions.

A year later, shortly after his father died, Overshiner wrote a bizarre, long-winded guest-editorial for Telephony magazine, attacking the pretentious Bell company and aligning himself, again, with the straight-talking everyman.

“I’m wondering if it is the ‘high-falutin’ bunk’ or the plain, old-fashioned heart to heart-to-heart talk that has the most influence with telephone buyers,” he wrote, clearly suggesting the latter was the answer. “I know that my concern has never indulged in anything but fact-stuff, without any ‘trimmin’s.’ The man who has piked in poles and helped to carry the reel awhile in the forenoon, adjusted a few ringers and hook contacts, and cleaned the gravity battery zincs in the afternoon, then run the board while the operator went to supper, and did the office work at night, is the man I want to reach. I can talk his kind of telephone talk—the talk that he and I have learned from the School of Experience.”

Part of that talk, it seems also involved skewering the general public for its ungratefulness.

“I say that there is not one telephone manager in the United States who is paid what he earns,” he continued, raising his fervor. “The last straw to his burden is when the sponging, non-subscribing, sneaking, grafting, can-I-use-your-phone-a-minute telephone user has the unadulterated gall and monumental nerve to kick and complain about the service. It’s enough to provoke premeditated murder. . . . I don’t know exactly why I am writing all this.”

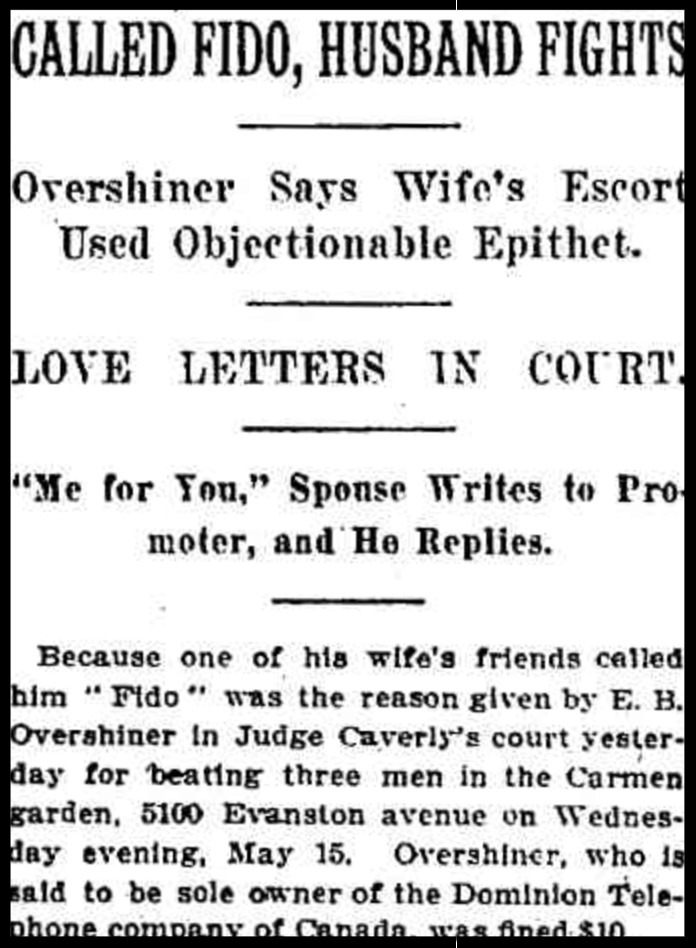

Months after that article was published, it suddenly became clear that Overshiner’s simmering anger wasn’t limited to letter writing. He was arrested for beating up three men after one of them supposedly addressed him as “Fido.” At least one of the men was apparently also friends with Overshiner’s wife Florence, who had recently filed for divorce. As part of that court filing, Mrs. Overshiner accused her husband of thirteen additional acts of cruelty against her. Overshiner, in return, gathered what he claimed were private love letters between his wife and another man, and had them read aloud in court. The salacious case soon became national tabloid news. This was the beginning of a long sad road.

Months after that article was published, it suddenly became clear that Overshiner’s simmering anger wasn’t limited to letter writing. He was arrested for beating up three men after one of them supposedly addressed him as “Fido.” At least one of the men was apparently also friends with Overshiner’s wife Florence, who had recently filed for divorce. As part of that court filing, Mrs. Overshiner accused her husband of thirteen additional acts of cruelty against her. Overshiner, in return, gathered what he claimed were private love letters between his wife and another man, and had them read aloud in court. The salacious case soon became national tabloid news. This was the beginning of a long sad road.

By the time the divorce was finally settled in 1913, Overshiner had left his post as president of the Swedish-American Telephone Company (it’s not clear if it was of his own accord). He wept on the witness stand during his testimony at the end of the case, but the judge ruled in his wife’s favor, characterizing E.B. Overshiner as “no better than a beast.”

In a further twist, the couple’s six year-old son Channing refused to go to his mother, and was ultimately given temporary custody with his father. “Channing and I will work it out together,” Florence Overshiner said. “His father has poisoned the boy against me, but there always has been in his heart the love and respect a son should feel for his mother.”

Hanging Up

During World War I, Overshiner shifted much of his attention to producing equipment for the government’s Signal Service Department, then continued diving deeper into radio, talking machines, and other things. Meanwhile, the Swedish-American enterprise was under completely new ownership by 1918. William R. Keene took charge that spring, with the humorously named Guy A. Joy serving as secretary and treasurer.

Keene’s goal was to keep the Swedish-American product up to the high standard of the past 20 years, but as the telephone industry moved out of its bronze age, the need for an independent “rural telephone” specialist began to evaporate. SATC was sold to Stromberg-Carlson in 1923, and the Ravenswood factory was promptly cleared out to make room for the map makers.

As for E.B. Overshiner, things were only getting more disturbing. In 1920, after taking a Vit Talking Machine sales trip to Logansport, Indiana, he was charged with “contributing to the delinquency” of a 16 year-old girl. According to the warrant issued, Overshiner, then 53, “attempted to induce the girl to go to Chicago with him, where her only duty would be to dress up and look pretty and sit in his office.” He’d apparently made the same advances on several other girls.

“I don’t remember the incident,” Overshiner told the Tribune. “Haven’t heard anything about any affidavit or warrant, or anything about young girls. Haven’t the least idea what it’s all about. There was a carnival on when I was there and I may have treated some of the girls to candy or ice cream or something like that.”

There do not seem to be any follow-up reports on that case, likely because Overshiner—a millionaire at the time—settled out of court in some fashion. His reputation was tarnished beyond all repair, however, and his fall from grace was irreversible.

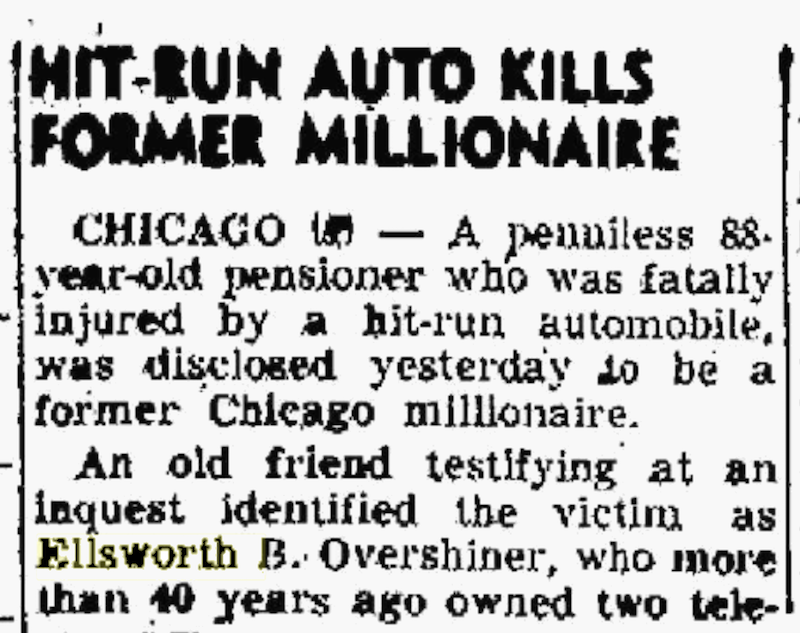

At some point, Overshiner put everything he had into a tungsten mining operation somewhere in South America. He was up to his old tricks again, assuring old friends it was a sure-fire moneymaker. When that venture eventually nose-dived, however, E.B.’s entire remaining fortune was lost. He was essentially never heard from again until New Year’s Day, 1956, when a “penniless 88 year-old pensioner” was struck by a hit-and-run vehicle on a Chicago street. The man, who died 11 days later, was identified as the “former Chicago millionaire” Ellsworth B. Overshiner—once the industrial king of Andersonville.

At some point, Overshiner put everything he had into a tungsten mining operation somewhere in South America. He was up to his old tricks again, assuring old friends it was a sure-fire moneymaker. When that venture eventually nose-dived, however, E.B.’s entire remaining fortune was lost. He was essentially never heard from again until New Year’s Day, 1956, when a “penniless 88 year-old pensioner” was struck by a hit-and-run vehicle on a Chicago street. The man, who died 11 days later, was identified as the “former Chicago millionaire” Ellsworth B. Overshiner—once the industrial king of Andersonville.

Hmm, this whole tale went off in a bleak direction I wasn’t anticipating. Sorry, folks. Next glogg’s on me.

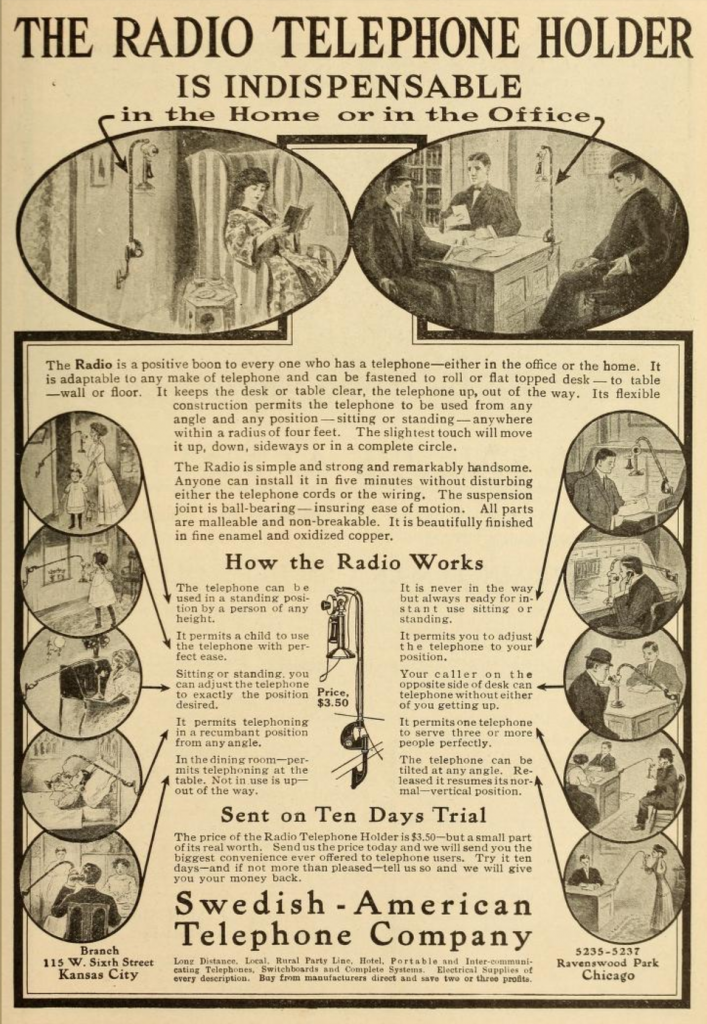

[1910 advertisement]

[1910 advertisement]

[1897 ad for E.B. Overshiner’s original phone company, Elwood Telephone & Switchboard Co.]

[1897 ad for E.B. Overshiner’s original phone company, Elwood Telephone & Switchboard Co.]

Sources:

Rural Telephone, 4th edition, by Swedish-American Telephone Co., 1908

Telephony, Vol. 9, No. 6 (1905), Vol. 61, No. 12 (1911), Vol. 64 (1913), Vol. 66, No. 18 (1913), Vol. 74, No. 24 (1918)

Electrical Engineering & Telephone Magazine, Dec. 15, 1899

Western Electrician, Vol XXVI (1900)

Telephone Magazine, July 1901

The Swedish Element in Illinois, by Ernst W. Olson, 1917

“Swedish-American Telephone Co. Building” – National Registry of Historic Places, 1985

American Telephone Journal, Vol. 16 (1907)

“Called Fido, Husband Fights” – Chicago Tribune, June 1, 1912

Archived Reader Comments:

“Thank you for this wonderful information. I inherited a Swedish American Hercules phone. It originally was on my Mother’s farm in North Dakota, 60 years or more ago. I will always keep it but I’d like to know what it is worth. It’s in pretty good shape on the outside. Not sure about the insides. Does anyone have a contact for me to research this? Thanks so much.” –Wendy P., 2019

“Great piece of writing. Enjoyed reading about SATC history I just added a complete “HERCLUES” wall phone for my collection. Having the history of the company adds much. Thanks. ” —

Hi

My wife bought the vintage phone from an auction. I believe it is an Hercules style phone. It has two #s on mouth piece 273170 and on the magnet inside 3826. It is missing a few pieces

-the piece if metal between the two ringer bells, on the front top I think it is missing an ID symbol, it is missing a seal and name plate on the front. not sure of it is missing a crank on the front right side, it is missing the two batteries in side the phone, and one screw and washer is missing. Diane bought the phone on 7 Jan 2025. Any assistance is greatly appreciated.

Thanks Richard and Diane Wright shilady26@gmail.com

.

I have a Swedish American telephone with the serial number is 32403. Was wondering if you can give me any information about it? Also the insignia of the lions are worn off. Is there any way I can get those would really appreciate it.

We have a 1908 swedish-american phone with the signa on it.Good shape would like to sell

Hello do you know where I can get a Hercules decal for a restored phone I have the newer Swedish American but can’t seem to find the other decal . Or did this phone only have one the serial number is 311649 any and all help is appreciated thank you Clyde Ross chatham illinois also do you have any wall art that I can get for this phone

I am in the process of refinishing a phone that has been in my clients family since the early 1900’s. The insignia of the lions and hercules are worn to the point of unrecognizable. I just got lucky hen reading your website and am wondering if those items are available for purchase. If so are they decals or metal print?

Do you have any telephones from 1919 candle stick, kind.

I have what appears to be a Swedish American wooden 4x5x8 phone booth with domed top. It originated in the Old English Hotel and Opera house in Indiana. Would love to find out more information on it.

I have a Swedish American telephone with the decal on stating it is a 1910. This telephone is in excellence condition.

Would you have any idea of what the price for this would be. It has all the inners inside of it.

I bought this exact phone with all the insides in tact for just under $600 at a local antique store in Las Vegas, NV. Hope that might help. C Lumley

We have what looks to be a telegraph transmitter with Swedish American Telephone Company on it, but can’t find any information about it online.