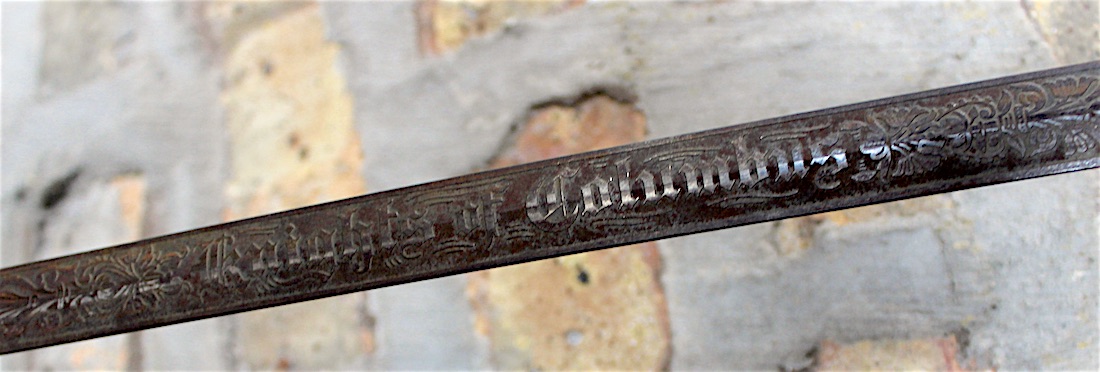

Museum Artifact: Knights of Columbus Ceremonial Sword, c. 1930s

Made By: T. C. Gleason MFG Co., 325 W. Madison St., Chicago, IL [Downtown/The Loop]

A Knights of Columbus sword, as you might presume, is made for symbolic, decorative use—not for combat. That being said, the sword in our collection, likely dating from the 1930s, is just sharp enough—and rusty enough—to at least pose a minor threat of tetanus. So keep your distance if ye be of weak heart or subpar hand-eye coordination.

As would seem appropriate for the instruments of a semi-secret society, the traditional swords and scabbards of the Knights of Columbus—that proud fraternal lodge of well-costumed American Catholicism—are a tad mysterious in their origins. Various types of swords were probably in use at KOC events dating back to the group’s founding in Connecticut in the 1880s, but it wasn’t until the “First Exemplification of the Fourth Degree” was held in New York in 1900 (introducing “Patriotism” as a new principle of the Order) that the more familiar black-handled sword tradition supposedly began.

In a rite of passage that’s still carried out today, assembly members who managed to attain the highest degree of the order and become Fourth Degree knights were also eligible to join the famed “Color Corps,” complete with all the recognizable ornate regalia: tuxedo, flamingo feather chapeau, flowing cape, and of course, the official sword. When the Fourth Degree celebrated its 100th anniversary in the year 2000, there were still more than 250,000 sword-wielding “Sir Knights” in service. So, for the few companies involved in the trade, ceremonial sword forging looks to have been a surprisingly steady business.

The earliest versions of the Knights of Columbus sword featured a flying eagle as the grip cap, but by the 1930s—according to most sources—the decapitated head of the Order’s patron, Christopher Columbus, took its place, and has remained there ever since.

Our museum artifact, produced by Chicago’s T.C. Gleason MFG Co., represents the first generation of these Columbus head models. We know this because the head is facing left (if you’re looking at the front of the sword), while later editions have him facing forward. Since knights were/are required to carry their scabbard on their left side, the original design kind of made more sense, as Columbus would always be facing in the same direction as the knight that carried him.

Over the past 70 years or so, two New York companies—Lynch & Kelly, Inc. and The English Company—have been the primary KOC sword makers. But prior to that, T.C. Gleason looks pretty unchallenged as the national leader.

What We Know About T.C. Gleason & Co.

As a proud, sword-carrying Knight himself, Thomas C. Gleason hardly wandered into this unusual business by accident. The first-generation son of Irish-Catholic immigrants was born in Illinois during the Civil War, and came of age just as the Knights of Columbus were expanding west. The organization was perfectly suited to Gleason, not just for its religious and philosophical principles, but its pomp and circumstance, as well.

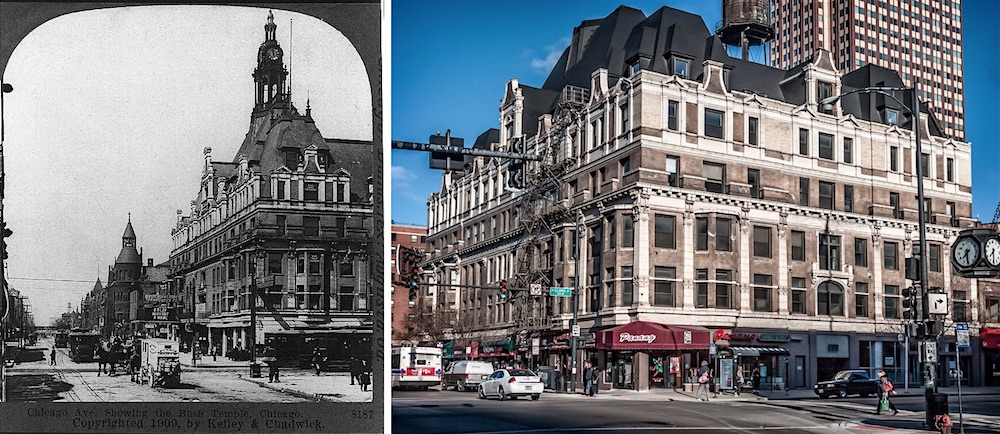

Before he ever got into manufacturing, Gleason [pictured] was a classically trained musician and theater director, and he always gravitated to a good production. He had studied music composition in Germany in his youth, and returned to his native Chicago to write, direct, and occasionally perform in stage plays through the turn of the century. In the 1900s, he was the general manager of the famed Bush Temple of Music (which is still standing at 100 W. Chicago Ave.), before taking over the College Theatre (at Sheffield and Webster) in 1910. Later, he produced some vaudevillian acts at Chicago’s Great Northern Hippodrome, including a popular one in 1917 called “The Submarine Attack,” starring Gleason’s own daughter Helen.

Gleason had a reputation, according to a 1915 article in the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, “for putting on stock productions of plays which had been successful just as soon as they could possibly be secured for that purpose.” On at least one occasion, he also put on a copyrighted show at the Bush Temple before he’d secured permission to do, which got him outright arrested in 1903. But he seemed to learn his lesson from that point forward.

[Program from Thomas Gleason’s time as the manager of the College Theatre in Lincoln Park, featuring “Gleason’s All Star Company,” 1912]

[Program from Thomas Gleason’s time as the manager of the College Theatre in Lincoln Park, featuring “Gleason’s All Star Company,” 1912]

Thomas was conveniently a big fan of Christopher Columbus, too. He co-wrote a four-act play about the explorer with Stanley Wood in 1910, and in the fall of that same year, joined with other loyal Chicago-area Knights in putting on one of the biggest productions in the organization’s history.

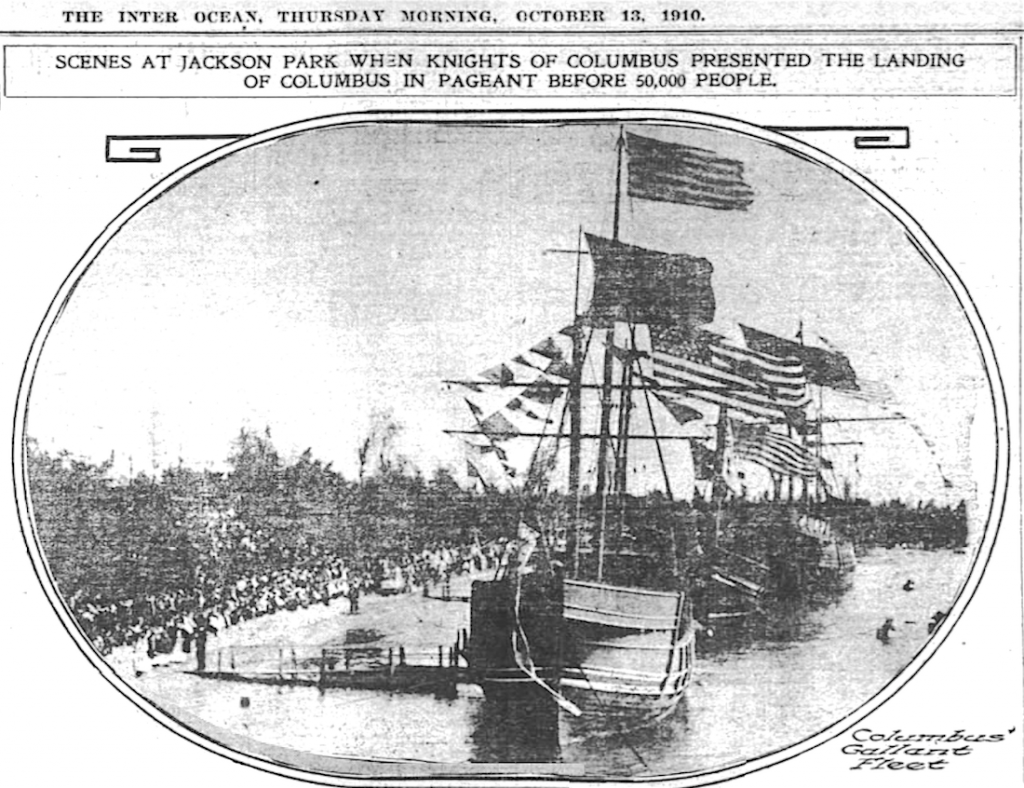

On October 12, more than 50,000 onlookers converged on Jackson Park (the largest gathering there since the 1893 World’s Fair), to watch 200 performers re-enact Columbus’s landing in the Americas, using the Knights of Columbus’s own fleet of Spanish sailing ships—albeit waving American flags. The celebration included elaborate set pieces and recreations of scenes from Columbus’s glorious journey, with careful avoidance of any of the more gruesome, historically accurate stuff.

By this point in time, demand for KOC swords and all other forms of lodge paraphernalia would have been reaching new peaks. The organization was growing by leaps and bounds every year—encouraging brotherhood and charity, combating anti-Catholic sentiments, and showing no shortage of flair at local parades and ribbon cuttings.

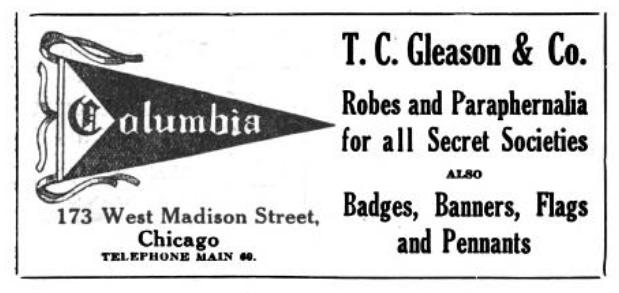

T. C. Gleason, as a deeply dedicated participant in this world, had already found another way to bring his two greatest interests—the lodge and the stage—together. In 1905, he’d organized T.C. Gleason & Co. with a capital stock of $5,000, joined by incorporators A.J. Schmidt and B.P. Barassa. The company specialized in the “manufacture of lodge sundries,” and had a small storefront downtown on Madison Street.

While continuing his theater management career at night, Gleason hoped to build up his new shop by day, catering not only to the Knights of Columbus, but all of those other secret societies taking over America’s men’s clubs. Whether you were a freemason, an elk, a moose, an odd fellow, or anything in between, you could get all your robes, badges, banners, and other symbolic paraphernalia—specially customized—from Gleason’s.

There were certainly some rough patches in the early going. Within months of launching the business, in fact, a major fire in the seven-story building at 170 Madison Street caused considerable damage to Gleason’s fourth floor plant.

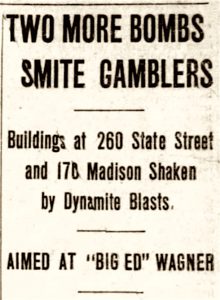

Four years later, in 1909, things got considerably more terrifying, as the same plant was badly damaged again when local gangsters set off a bomb in the building. The attack had targeted the Worth Jockey Club and gambling tycoon “Big Ed” Wagner, but the bombers had their reconnaissance slightly off—Wagner’s business was located on the third floor, while the explosive was detonated on the fifth. The resulting blast “tore a hole of about eighteen inches in diameter down through the ceiling of the fourth floor into the plants of T. C. Gleason & Co., makers of badges and flags,” according to the Tribune. “Most of the furniture and fixtures in the plant were demolished, nearly every pane of glass in the building was demolished, partitions were torn from their foundations, and plaster all the way from the saloon on the ground floor clear up to the roof was broken.”

Seemingly unfazed by these disasters, Tom Gleason rebuilt and carried on into the 1910s, becoming one of the most recognizable men in the country among the secret society crowd, particularly the good old Knights of Columbus. He would routinely travel to major lodge conventions and glad hand with the gatherers about their accessory needs. After one such event in Davenport, Iowa, in 1916, the local papers reported that:

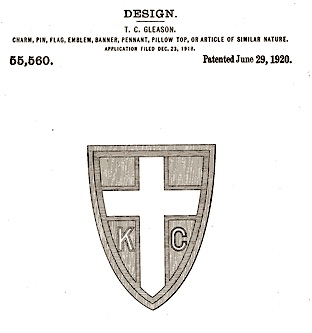

“T.C. Gleason, the owner of a Chicago regalia company, which provides the Knights of Columbus with much of their materials for degree work . . . is one of the shining lights of the convention. He can be found wherever a good social time exists.” [pictured: A Knights of Columbus badge/emblem that Thomas Gleason received a patent for designing in 1920]

“T.C. Gleason, the owner of a Chicago regalia company, which provides the Knights of Columbus with much of their materials for degree work . . . is one of the shining lights of the convention. He can be found wherever a good social time exists.” [pictured: A Knights of Columbus badge/emblem that Thomas Gleason received a patent for designing in 1920]

Somewhere along the line, the business was rebranded as the T.C. Gleason Manufacturing Co., and the swords and scabbards became a big part of the operation. As to whether any of these “weapons” were legitimately forged by Gleason’s own employees, however, seems to be a point of contention.

The sword in our collection, for example, despite having “T.C. Gleason MFG Co. / Chicago” etched into the blade, also says “Made in Germany” in tinier text just above the handle. This suggests that the general business model involved purchasing cookie cutter swords in bulk from Europe, then custom-branding and distributing them out of Gleason’s Chicago HQ. There was still craft and skill still required for this work, however, as it seems evident that much of the actual steel etching was being done in-house by Chicago workers, judging by this 1934 classified ad from the Tribune:

Sadly, Thomas Gleason didn’t live to see his business reach its sword-making apex in the ’30s and ’40s. In August of 1923, while driving with his wife and friends from a Knights convention in Montreal to another one scheduled in Boston, his vehicle overturned and crashed into a ditch, pinning him underneath. Remarkably, everyone survived the initial accident, including Gleason. But within days of his return to Chicago, further complications from his injuries led to his death at the age of 59.

From what I can tell, the T.C. Gleason MFG Co. appears to fade out of existence shortly after World War II, perhaps a victim of metal rationing during the era, or the overall drop-off in secret societies in the second half of the 20th century. If you have more insights into the business and who might have picked up the baton after Thomas Gleason’s demise, let us know by commenting below or sending us a message via the contact page.

[The Bush Temple of Music on Chicago Avenue, which Thomas Gleason managed in the first decade of the 1900s]

[The Bush Temple of Music on Chicago Avenue, which Thomas Gleason managed in the first decade of the 1900s]

Sources:

Fourth Degree Knights Of Columbus

The Advocate, Vol 53, 1917

“Claims Bush Temple Play” – Chicago Tribune, June 13, 1903

“New Corporations Licensed” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 27, 1905

“Fire Causes Terror in Hotel” – Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1905

“Two More Bombs Smite Gamblers” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 1, 1909

“Women Aid Reopened Theater” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 3, 1910

“Scenes at Jackson Park When Knights of Columbus Presented the Landing of Columbus in Pageant Before 50,000 People” – The Inter Ocean, October 13, 1910

“Society” – Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, Nov 4, 1915

“Welcome the Knights of Columbus at Opening of Convention Here Today” – The Davenport Democrat and Leader, Aug 1, 1916

“Convention Notes” – The Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), Aug 1, 1916

“The Huntington Theater: Miss Gleason, Clever Leading Lady” – Huntington Herald, Sept 30, 1916

“Prominent K. of C. Dead” – Freeport Journal-Standard, Aug 20, 1923

I have the eagle top knight sword, what cleaning solution can I use.

I have a same sword as well

Hi,

We have a game, we think, manufactured by T.C. Gleason. It has been in the family for years. We have no idea what it might be. I have taken a photo, but did not locate a place to attach and send. Hopefully you can help us solve the riddle.

I have one of the swords with Christopher Columbus head facing left that was passed down to my father from my grandfather! Have you found out what year they changed it to facing forward! I’m trying to narrow down how old it is!

Badge

member gold sing,

2 little chain slide down,

Sing KofC with logo and 4 white and red triangle

And for back side, we have mini punch : TC. GleasonFMG & co, Chicago

I bought at auction a KofC sword with the eagle top. It’s marked “T.C. Gleason & Co.”

“The House of Quality”

“Chicago”

I assume it’s from the early 20’s?

The script says “Knights of Columbus” on the blade. I’ve seen some that had a flattened

or cut off end of the blade. Some have the owner’s name in script on the blade.

Hello, I have an Eye Mask that has “Social Service. Ebenezer Baptist Church. It was made by T C Gleason Chicago. Looking for information as to when it was made.

Thank you for a great article on these swords. My father passed away and I found a sword like this in his collection. If you have found any more information about these swords or Mr. Gleason I would enjoy reading more.