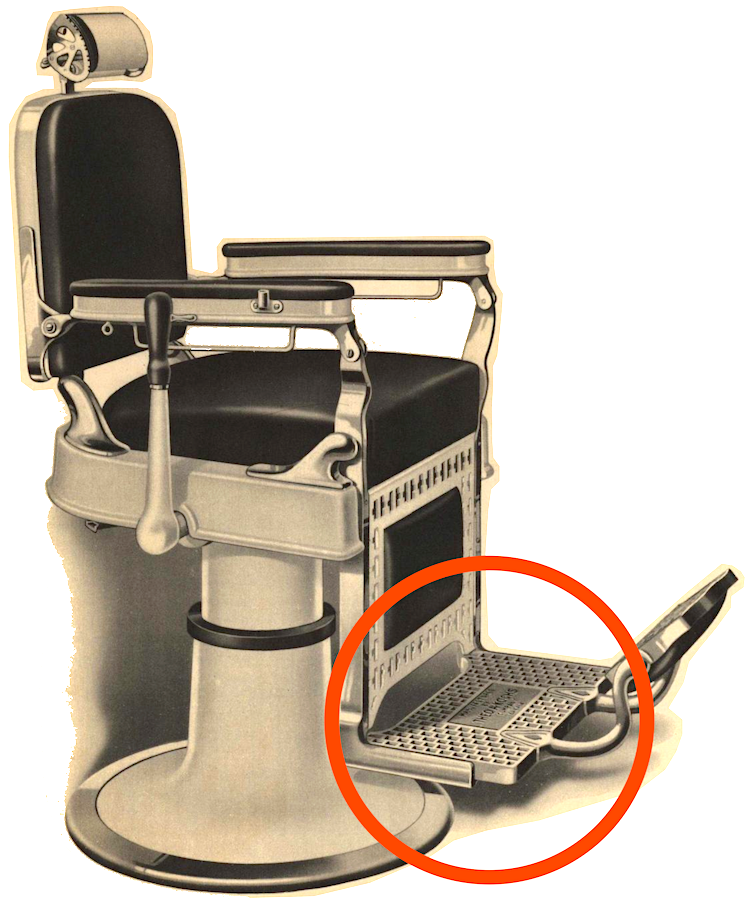

Museum Artifact: Barber Chair Footrest (Lower Plate), c. 1920s

Made By: Theo. A. Kochs Company, 659-679 N. Wells Street, Chicago, IL [River North]

“Quality is our watchword, and chairs of our manufacture can be depended upon to be as near perfection as is possible. We aim to make only the very best, and economy is never allowed to interfere with the quality of the goods. Our customers are, therefore, always safe in placing their orders with us, for they will positively receive full value for every cent paid.” —Theodore A. Kochs Company catalog, 1903

Few things are more associated with mainstream, Main Street Americana than the barbershop—and unsurprisingly, many of the sights, sounds, and smells that came to define these establishments in the late 19th and early 20th century can be traced back to the fastest growing city of that period.

Few things are more associated with mainstream, Main Street Americana than the barbershop—and unsurprisingly, many of the sights, sounds, and smells that came to define these establishments in the late 19th and early 20th century can be traced back to the fastest growing city of that period.

During the World’s Fair hoopla of 1893, Chicagoan A. B. Moler effectively launched the modern age of hair styling by opening the first barber college in the country and penning the first widely accepted textbook of the trade, The Moler Manual of Barbering. A generation later, an organization of Moler acolytes called the Associated Master Barbers of America—established in Chicago—would be responsible for standardizing much of the industry, including the introduction of licensing requirements for professional barbers and sanitation regulations for shop owners.

Long before all of these more bureaucratic developments, though, Chicago was already home to the Theodore A. Kochs Company, one of the big tentpole businesses (or barber pole businesses, I suppose) of salon culture.

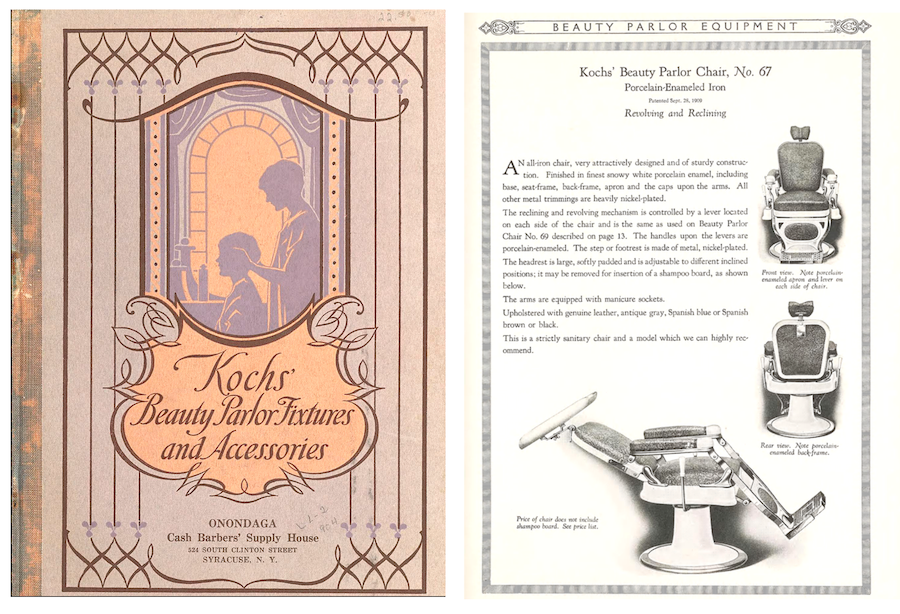

Founded during the city’s post-fire rebuild in 1871, Kochs played an important role in advancing both the functional and aesthetic quality of American barbershops and beauty parlors—each of which had fallen into ill repute through most of the 1800s.

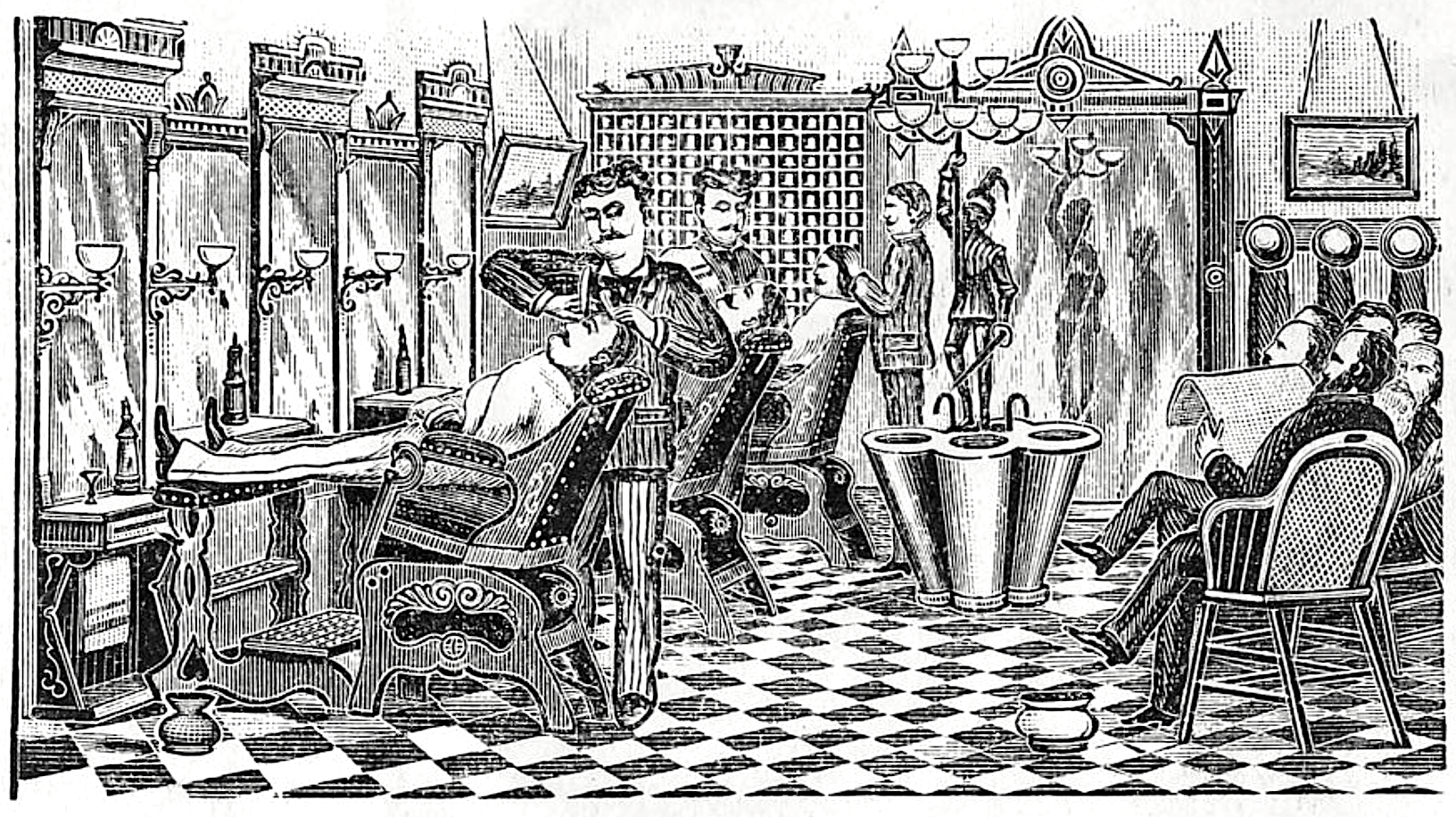

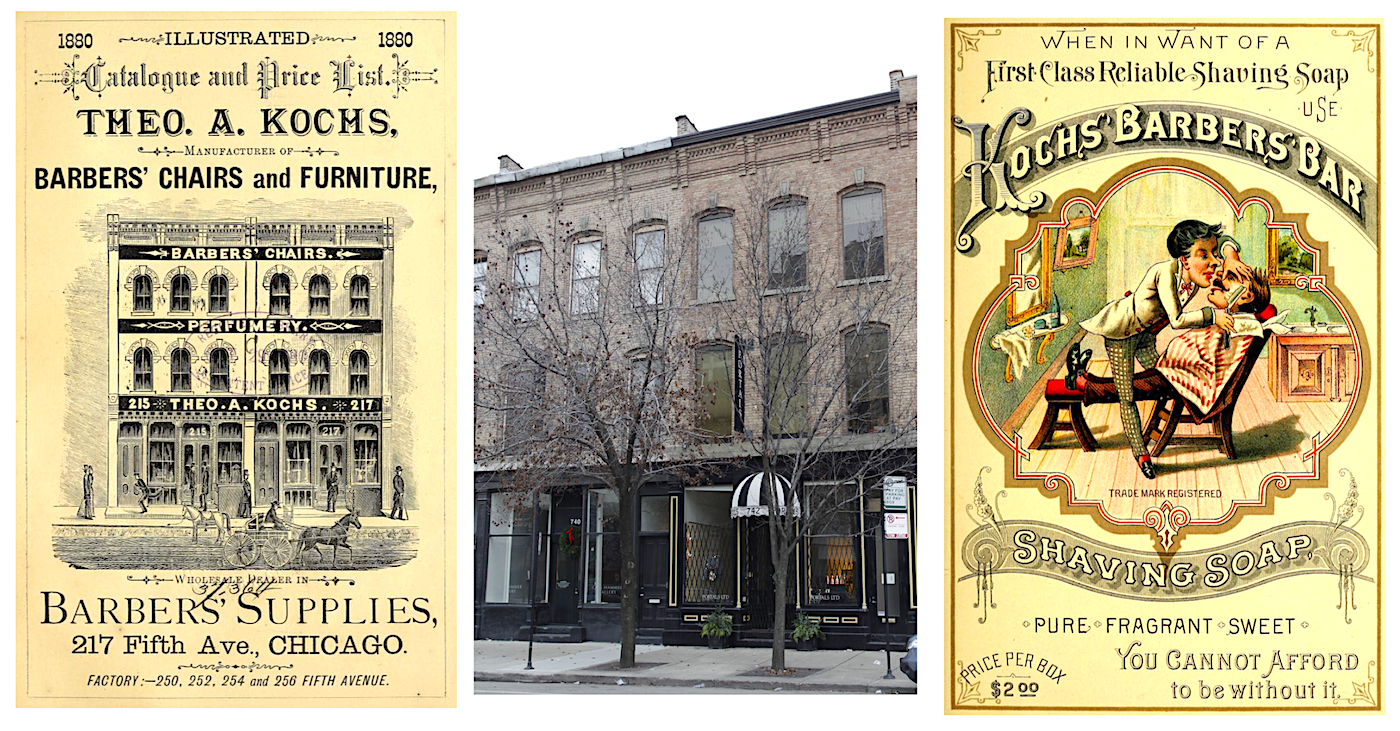

[Artist’s depiction of a barber shop, from 1880 Kochs Company catalogue]

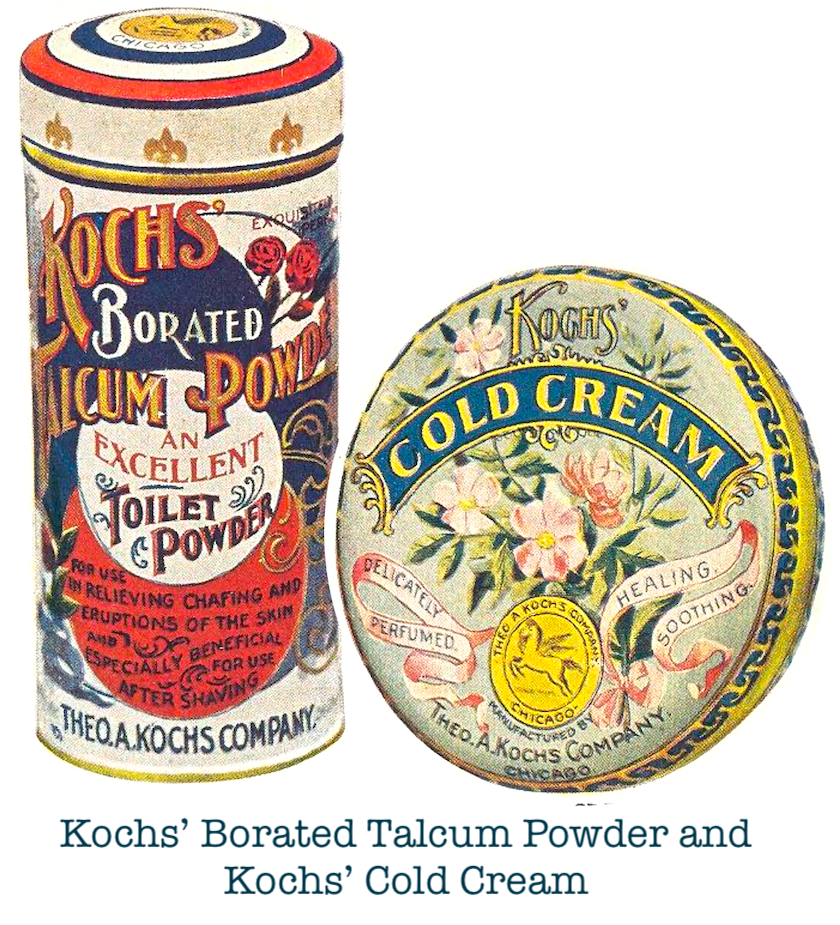

At its bustling River North factory, the Kochs Co. produced or warehoused just about every imaginable piece of barberalia: chairs, clippers, combs, and creams . . . barber’s poles, mirror cases, shaving mugs, and wash stands . . . even something called the Imperial Mustache Curler.

The specific artifact in our museum collection dates (roughly) to the 1910s or ‘20s, and served as the lower portion of the footrest apparatus on a hydraulic Kochs barber chair. While this heavy metal footplate has turned a rusty brown over the course of a century, you can still see the attention to detail and leftover Art Nouveau design elements that were so important to the early styling of these chairs. The goal wasn’t just to pamper the customer, but to create a cohesive style within the shop—one more akin to a wealthy gentleman’s club rather than the tawdry gambling hall vibe of the typical Civil War era hair-cuttery.

The specific artifact in our museum collection dates (roughly) to the 1910s or ‘20s, and served as the lower portion of the footrest apparatus on a hydraulic Kochs barber chair. While this heavy metal footplate has turned a rusty brown over the course of a century, you can still see the attention to detail and leftover Art Nouveau design elements that were so important to the early styling of these chairs. The goal wasn’t just to pamper the customer, but to create a cohesive style within the shop—one more akin to a wealthy gentleman’s club rather than the tawdry gambling hall vibe of the typical Civil War era hair-cuttery.

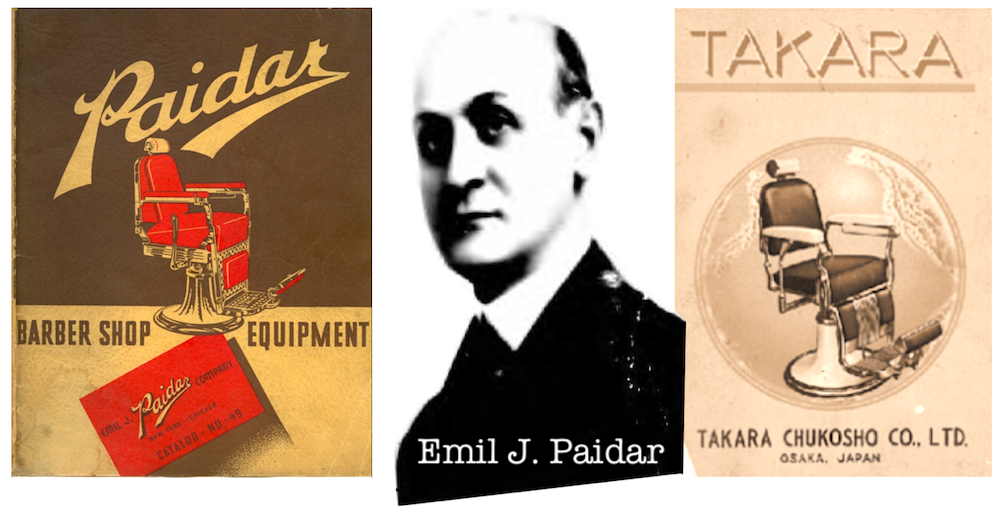

The Kochs Company borrowed plenty from its competitors’ innovations, and in turn, was copycatted constantly by others. One of the other big names in the industry, Chicago’s Emil J. Paidar, actually started out as a licensed distributor of Kochs’ patented designs before launching a manufacturing business of his own.

Quality, as mentioned in that catalog excerpt at the top of this article, was what ultimately kept the Kochs name relevant for over 70 years. But while the engineering of a Kochs barber chair is everything you’d expect from a business run by a well educated German immigrant, Mr. Kochs himself didn’t actually come from a mechanical background. In fact, if not for the Great Chicago Fire, he might never have closed up his pharmacy.

[An assortment of Kochs barber poles from the 1888 catalogue]

History of Theo. A. Kochs Company, Part I: The Man Himself

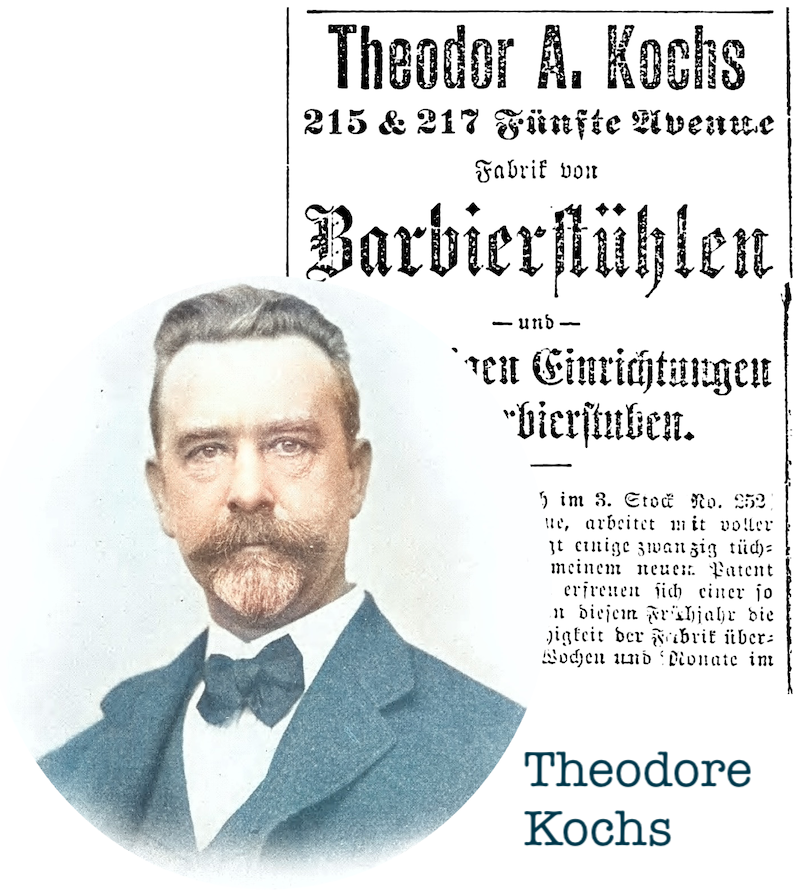

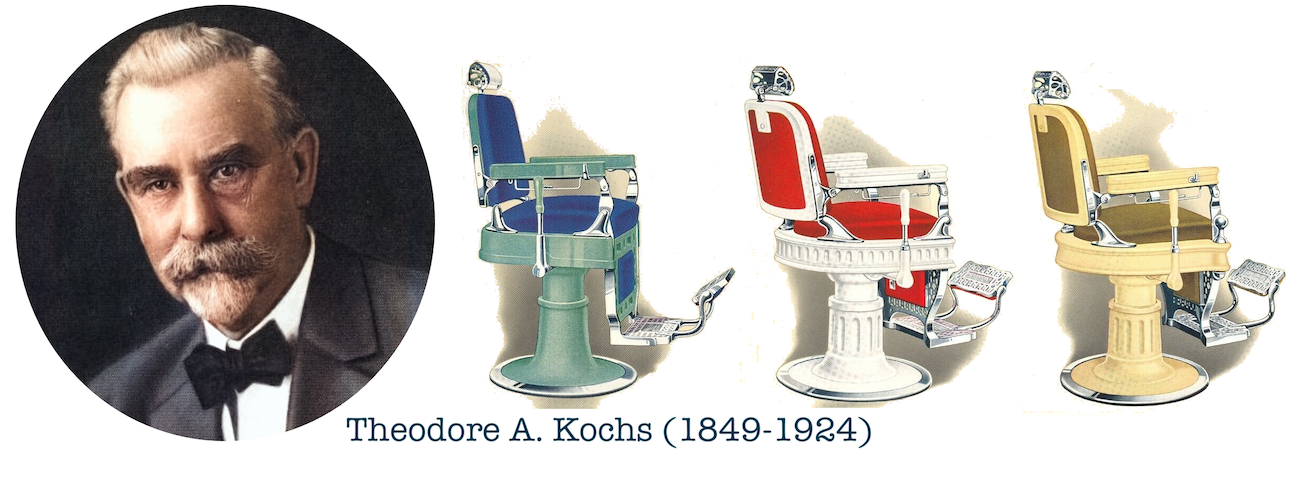

Theodore Kochs (and yes, that’s KOCHS with an “S” at the end; a detail that would be routinely overlooked across his life) was born in the town of Emmerich, Germany (Prussia at the time), in 1849. He studied chemistry at his hometown university, but by the age of 18, he was already on a ship to America, joining a steady stream of German immigration into the rising metropolises of the Midwest.

By 1869, Kochs had managed to set up a drug store on the West Side of Chicago, and business was apparently quite good. Like so many others in the wake of the fire of 1871, though, he was suddenly left with a blank slate. Still only 22 years old, Kochs re-assessed his prospects and decided to rebuild, but with a rather substantial alteration in his business model.

By 1869, Kochs had managed to set up a drug store on the West Side of Chicago, and business was apparently quite good. Like so many others in the wake of the fire of 1871, though, he was suddenly left with a blank slate. Still only 22 years old, Kochs re-assessed his prospects and decided to rebuild, but with a rather substantial alteration in his business model.

Within a few years, he’d established the Theo. A. Kochs Company, maker of “barber supplies,” with an office at 215-217 Fifth Avenue (what would now be 750 N. Wells St.) and a factory next door at 207-209 Fifth Ave. (742 N Wells St.).

According to a 1878 advertisement in Chicago’s German language newspaper Staats-Zeitung, the “patentirter Barbierftuhl” (patented barber chairs) of Theo. A. Kochs were already well known in the industry. The 1880 company catalog paints a clearer picture, claiming that “our Barbers’ Chairs have gained a high reputation all through the country and are acknowledged to be the most durable and artistic in design. So great has been the demand for them, that we have been obliged to increase the capacity of our factory until we are now able to furnish them at the rate of over 100 per month.”

As noted, after just a few years in business, the Kochs manufacturing space had already moved across the street to 250-256 Fifth Avenue (837-843 N. Wells St.). From here, the firm was offering full outfitting services for barbershops, with its 50-page catalog including not only the company’s own chairs and washstands, but loads of wholesale goods and Kochs-branded accoutrement: shampoos, pomades, soaps, perfumery, etc. A page of color illustrations featuring your classic red, white and blue barber poles was also included.

[Left: Sketch of the Kochs offices at 217 Fifth Ave. (750 N. Wells St.) in 1880. Center: A surviving building at 742 N. Wells St., which was also part of Kochs’ complex in the early 1880s. Right: Ad for Kochs’ Barbers Bar Shaving Soap, 1888]

The Kochs calling card from the very beginning, though, was its line of patented, reclining barbers chairs. We really have no idea how or why Theodore Kochs wound up pursuing this highly niche furniture market. But having run a pharmacy for a few years, it makes sense that he might have done business with some men from the salon trade and thus recognized a growing supply-and-demand gap. The chair, naturally, was the centerpiece of any hair salon, and it was the most important factor in determining if the trend toward sophisticated style and comfort would persist.

As explained by architectural historian Sigfried Giedion in his 1948 book Mechanization Takes Command, the American barber chair was beginning to “throw off its century-old stiffness” by the latter half of the 1800s. Unlike its European counterparts, which remained rigid and straight, the U.S. chair was in constant flux, as designers looked to solve the basic problem facing every barber in his daily work.

“There is but one correct position for hair-cutting,” Giedion writes, “the vertical, which requires a normal seat. For shaving, the customer is in the most favorable position when swung so far into the horizontal that both cheeks and the underside of the chin present almost vertical surfaces. . . . Readily to combine the two activities, shaving and hair-cutting, the chair should be movable and adjustable.”

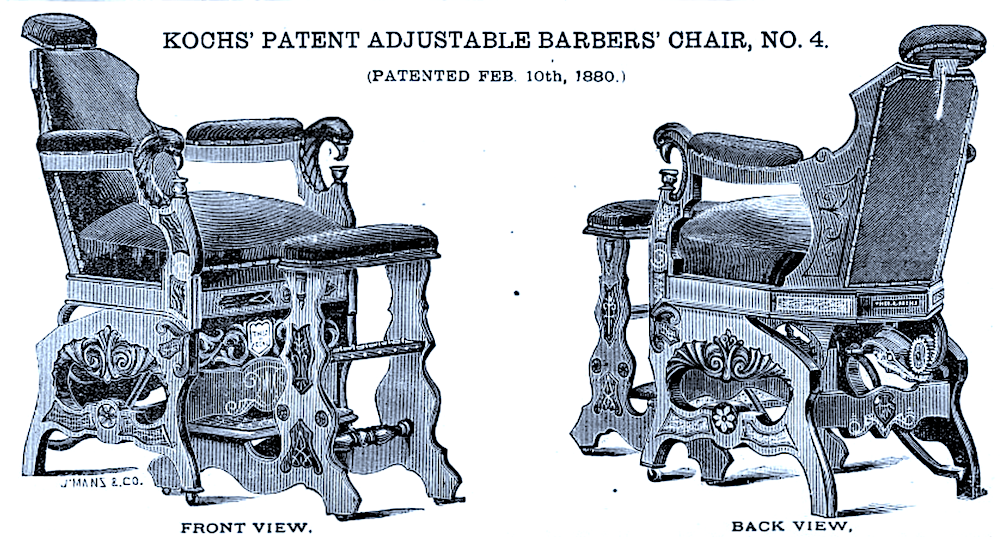

[One of Kochs’ earliest and most influential barber chair models was the No. 4, designed by Franz Peters and patented in 1880]

The first wave of adjustable barber’s chairs—ratcheted and clunky— emerged during the 1850s. Improvements in these “tilted chairs”—for both barbers and dentists—came along in the late 1860s, and by the time Theodore A. Kochs and his team entered the game in the ‘70s, the whole adjustment from vertical to horizontal had become greatly improved thanks to smoother mechanisms patented by manufacturers such as the Archer Company of St. Louis and the Eugene Berninghaus Co. of Cincinnati.

One of Kochs’ lead engineers, Franz Peters, built upon these existing designs and patented several more important developments in the field between 1877 and 1880; for a while, his models became the industry standard.

“The machinery [of our chair] is of a very simple and ingenious construction,” the 1880 Kochs catalog explained, “and works easier than any other machinery on Barbers’ Chairs. Two rack-bars fastened on the upper part of the chair are connected with the gears, and same gears are again in connection with a horizontal bar provided with a steel spring on the underside so as to form a Perfect Lock. This bar is operated by a lever with projecting pedal to the rear of the chair in easy reach for the barber’s foot from all sides.”

“The machinery [of our chair] is of a very simple and ingenious construction,” the 1880 Kochs catalog explained, “and works easier than any other machinery on Barbers’ Chairs. Two rack-bars fastened on the upper part of the chair are connected with the gears, and same gears are again in connection with a horizontal bar provided with a steel spring on the underside so as to form a Perfect Lock. This bar is operated by a lever with projecting pedal to the rear of the chair in easy reach for the barber’s foot from all sides.”

As an example of how the Kochs Company was impacting the overall reputation of the barber trade, have a look at how the Chicago Tribune reported on the opening of a new “barber shop and bath” inside the Lakeside Building on Clark Street during the spring of 1881. Run by the Petillon Brothers (formerly of the Grand Pacific Hotel), the new shop was said to “eclipse, in magnitude or palatial accommodations and in richness, taste, and splendor of modern appointments, accessories, and general furniture, outfit and equipment, anything heretofore attempted in Chicago or the Western World in the department of our civilized existence known as tonsorial and bathing.

[Illustration of a barbershop outfitted by Kochs, inside Chicago’s Grand Pacific Hotel, 1888]

“. . . There are ten luxurious chairs of special design, very ornate, handsomely upholstered, and embracing the latest improvements in construction. These chairs, which for their elegance, symmetry, strength, and simplicity of construction, and all requirements, are pronounced superior to any before made, were furnished by Theo A. Kochs, 217 Fifth avenue, as were other furnishings and appointments.”

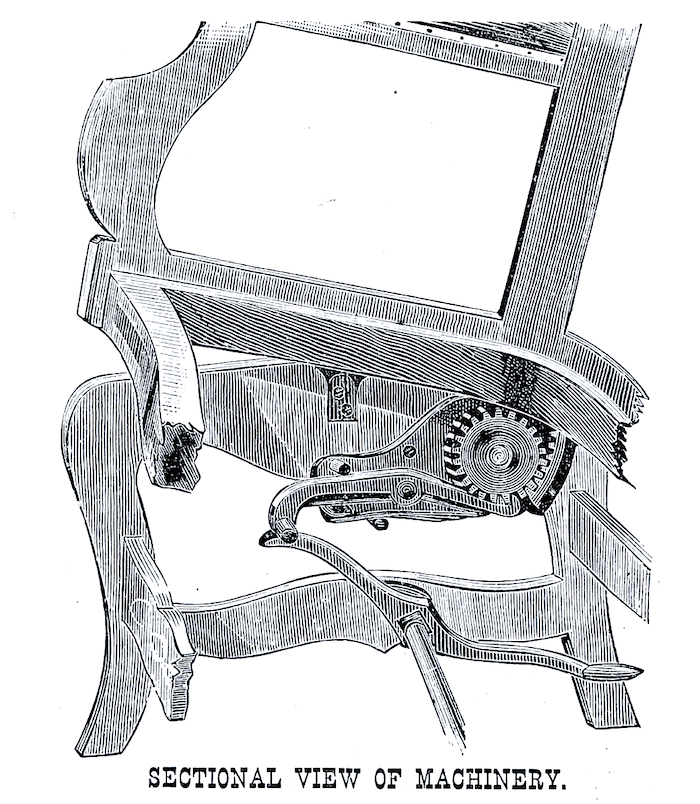

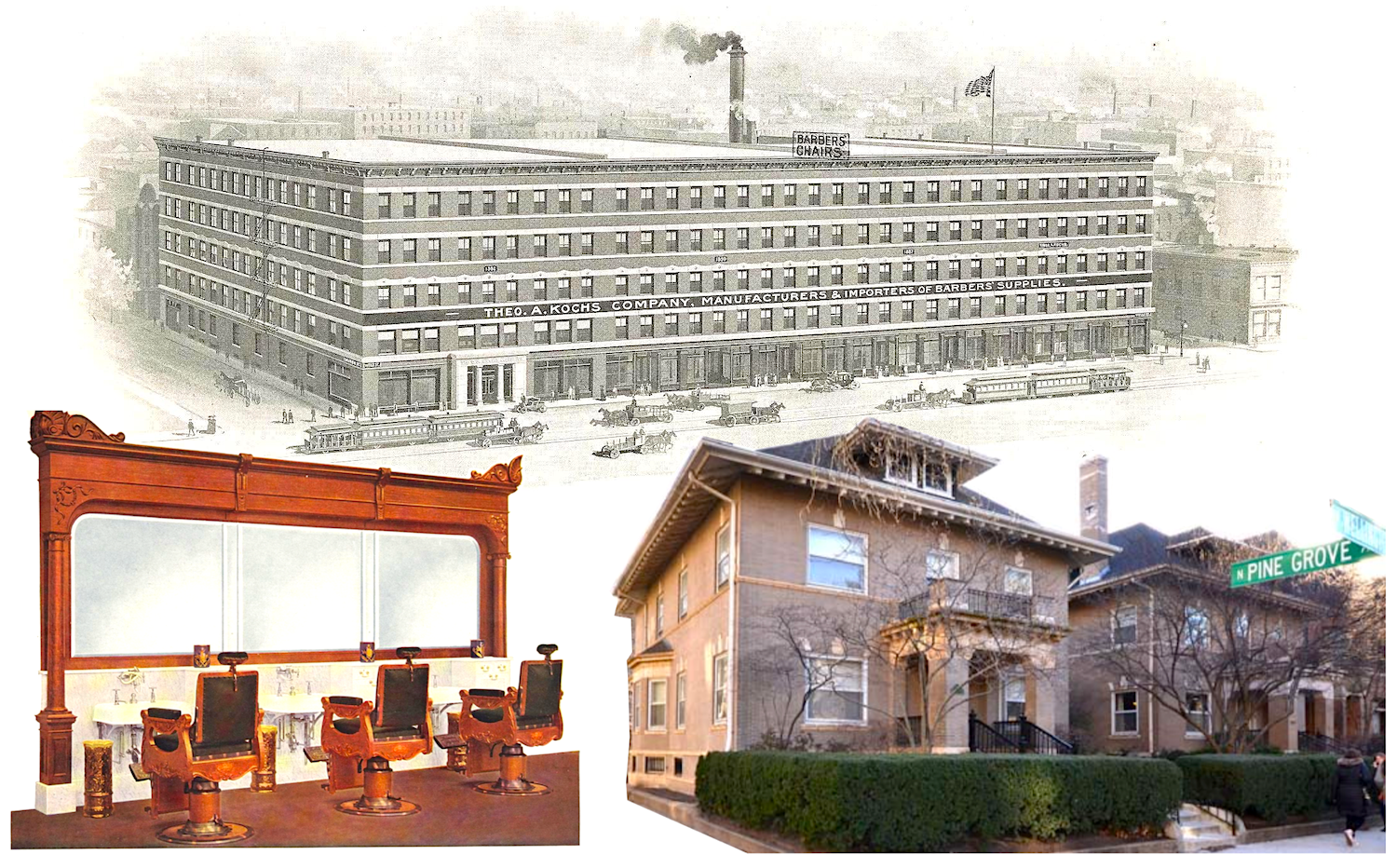

The Kochs chairs of the 1880s are mechanically impressive, but to a 21st century eye, they also look more like a place to sit for one’s execution rather than a quick trim. The four-legged throne-style chair, often with a detached footrest, remained en vogue through the 1880s, but by 1893, the popular styles start to look more familiar, with a central hydraulic column under the seat for north/south adjustments, along with more precise movements in the headrest, backrest, and attached two-part footrest.

II. The Big House on Wells Street

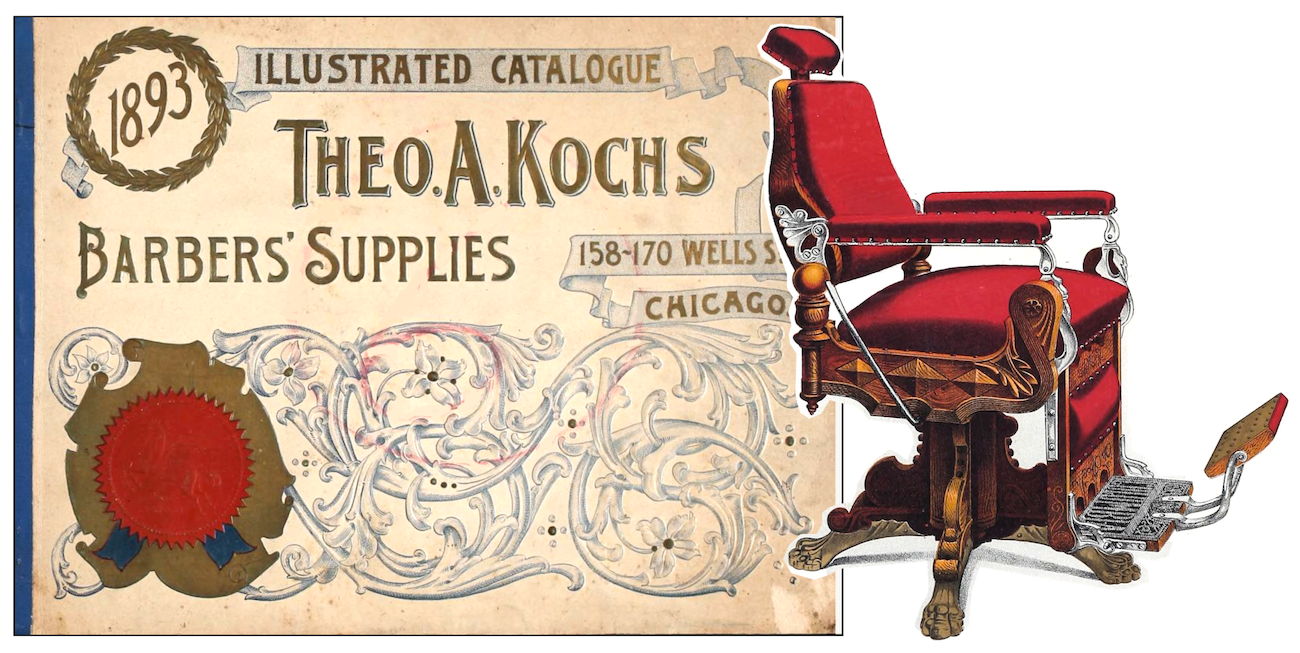

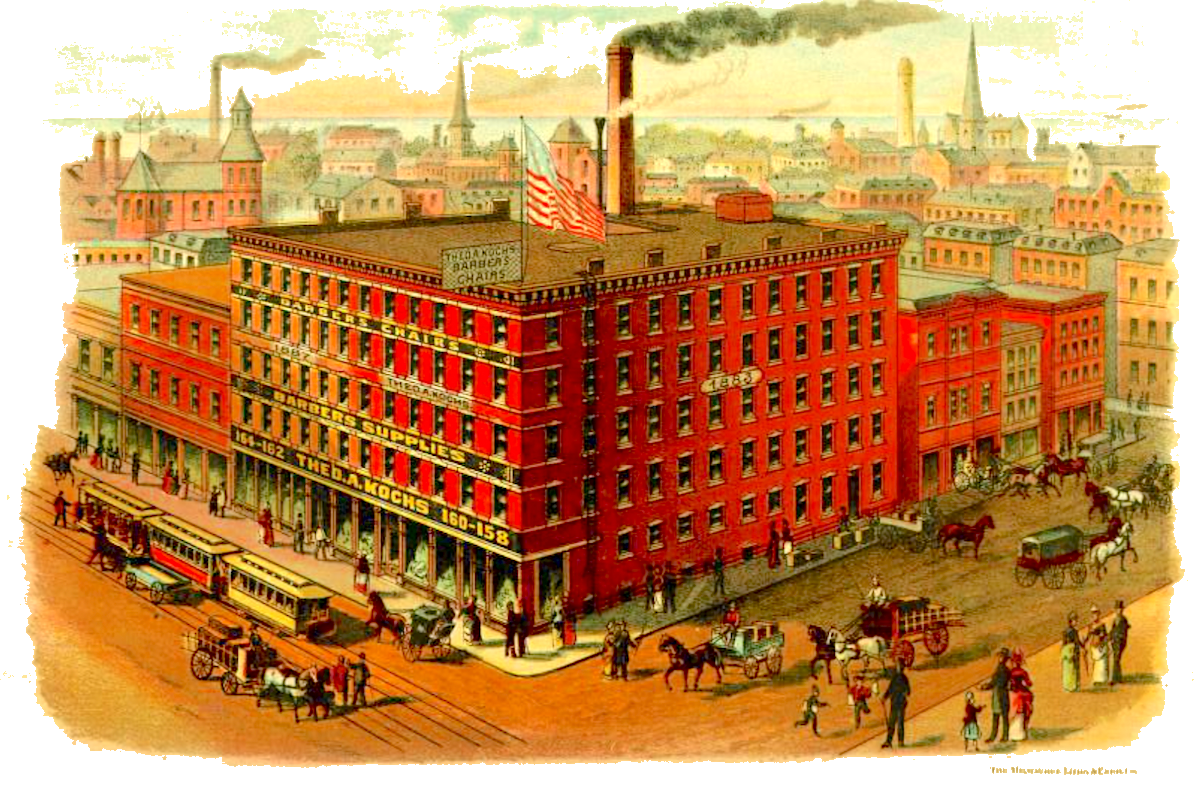

“In illustrating the rapid growth of the City of Chicago and its wonderful development, one of the best examples is the establishment of Theo. A. Kochs, manufacturer of Barbers’ Supplies, at 158-170 Wells Street.” —Chicago, the Garden City, 1893

It’s highly unlikely that Theodore Kochs could have envisioned or even hoped for the sort of growth his business experienced in the dash toward the end of the century. In 1883, he was forced to expand his factory space once again, paying for the construction of a new headquarters at 158-160 N. Wells Street (which would later become 659 N. Wells after the street number changes of 1909). Another story was added to the building in 1885, and the adjoining lot was acquired and added on within another two years.

It’s highly unlikely that Theodore Kochs could have envisioned or even hoped for the sort of growth his business experienced in the dash toward the end of the century. In 1883, he was forced to expand his factory space once again, paying for the construction of a new headquarters at 158-160 N. Wells Street (which would later become 659 N. Wells after the street number changes of 1909). Another story was added to the building in 1885, and the adjoining lot was acquired and added on within another two years.

“But even this was not sufficient,” according to the 1893 guide book, Chicago: Garden City. “In 1890 the building was again enlarged so that now it occupies a frontage of 148 feet on Wells Street and 110 feet on Erie Street, making a total floor space of almost two acres.

“In this vast establishment about 250 men are employed in the manufacture of Barbers’ Chairs and Furniture, Barbers’ Poles, Decorated Shaving Mugs, Cosmetics and Perfumery of all descriptions, and, in fact, everything that is required in a modern barber shop. These goods are shipped to all parts of the United States, from Maine to California, to Canada, Mexico, England, Australia and South America, and the establishment that was born twenty years ago now supplies the barbers in every corner of the civilized world.”

[Theo A. Kochs Company’s Chicago factory, “largest of its kind in the world,” as illustrated in the 1888 catalog]

Kochs had undeniably become a mighty success story, and with the company name prominently displayed in those cast iron footrest plates, anybody watching their hair clippings drop down onto their shoes would come to know the brand out of Chicago.

That being said, Kochs never entirely vanquished its competition. In particular, the similar sounding Koken Company out of St. Louis had gained considerable ground in the 1880s, with its founder Ernest Koken emerging as the leading innovator and patent collector of the period. As such, competing barber supply catalogs at the turn of the century relied heavily on (a) offering the most value for the stylist’s dollar, and (b) the newest advances in “chair technology,” for lack of a better term.

In its 1893 catalog, Kochs touted its revolving and rotating “Columbia” model (patented in 1891 and named in honor of the approaching Columbian Exposition): “One lever is all that is necessary to recline the chair or to revolve it when reclined or upright, and every result can be accomplished that other chairs require a lever AND a foot treadle to accomplish.”

By 1903, the hydraulic age was in full effect, and Kochs chairs had shed their legs entirely in favor of a pedestal design with a combination of “quarter-sawed oak” and iron, “neatly japanned in black and gold and fitted with solid brass rim, polished,” with maroon leather or mohair plush upholstery.

The Koken Company had raised the bar for the whole industry, but Kochs showed no hesitation in rising to the challenge. It’s easy to understand why barber chairs from this era are highly sought after by collectors. They are remarkable feats not just of functional furniture design, but detailed Art Nouveau styling.

Some of the key engineers and designers involved in Kochs’ early 20th century chairs include Charles W. Fischer, Herold H. Ross, and Charles Pfanschmidt. Theodore Kochs, presumably more of a businessman than an inventor, only collected a few patents under his own name, mostly for arm-rest designs.

[Top: Kochs expanded factory, 1903. Bottom Left: Kochs chairs and mirror case set-up, 1906. Bottom Right: These homes at 305 and 309 W. Wellington Avenue were both built in 1901 for Theodore Kochs and his family.]

III. The Recline and Fall of a Barber Chair Giant

“When you are in Chicago we hope that you will not fail to honor us with a visit, for a few minutes ride upon the north side cable car will bring you to our door. Our offices are upon the second floor at the Huron St. corner, to which the entrance to our building leads you, and we assure you that it will afford us great pleasure to meet you and to conduct you through our establishment. We employ skilled union labor, and the 250 men in our factory are experts in their several lines.” —Kochs Co. catalog, 1903

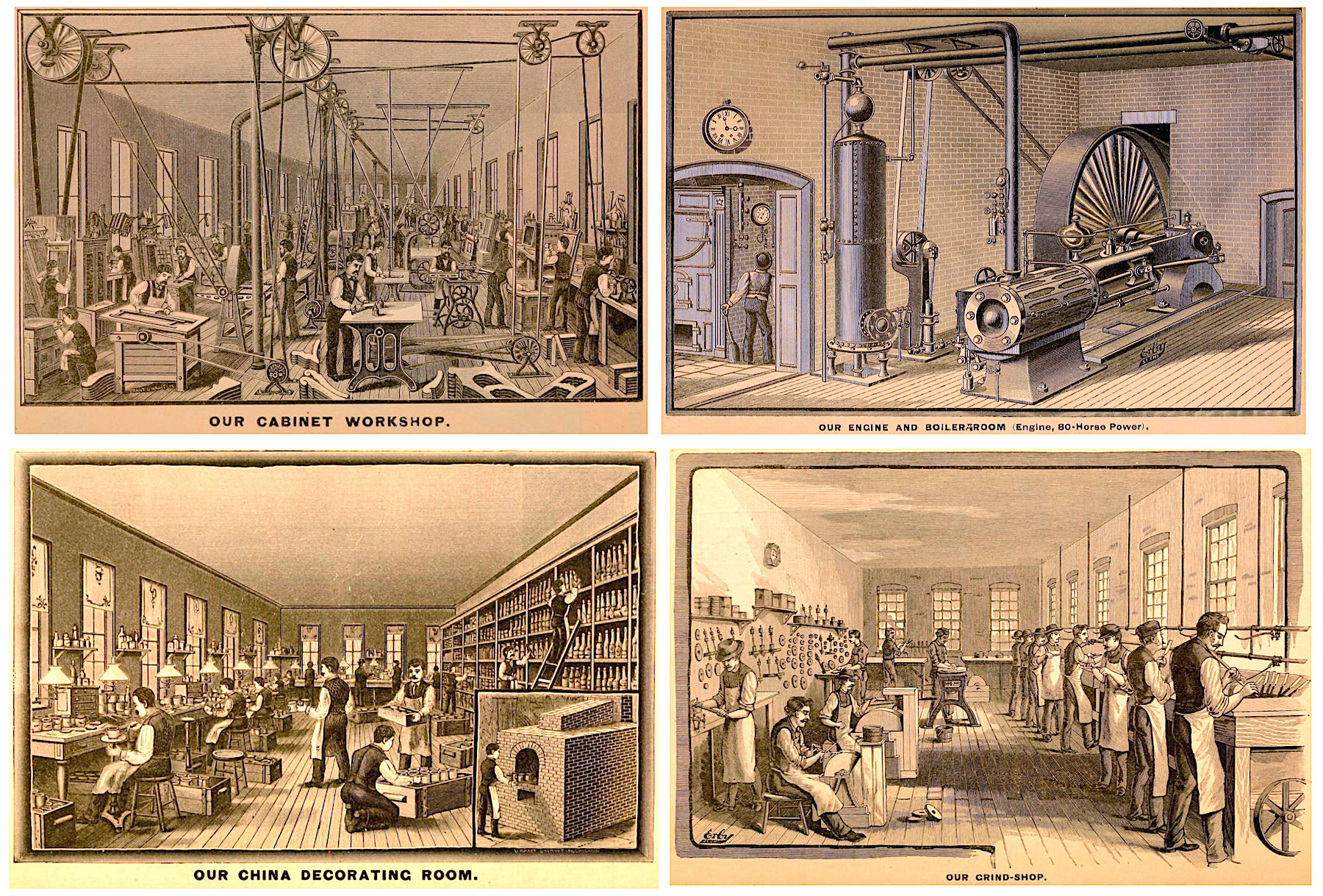

Like many of Chicago’s leading manufacturing businesses in the early 1900s, the Theo. A. Kochs Company was proud to use its “skilled union labor” as a selling point to the public, but the actual relationship between those workers and company management was far from lockstep.

[Workers depicted in four departments of the Kochs Company factory, 1888: the Cabinet Workshop, the Engine and Boiler Room, the China Decorating Room, and the Grind Shop]

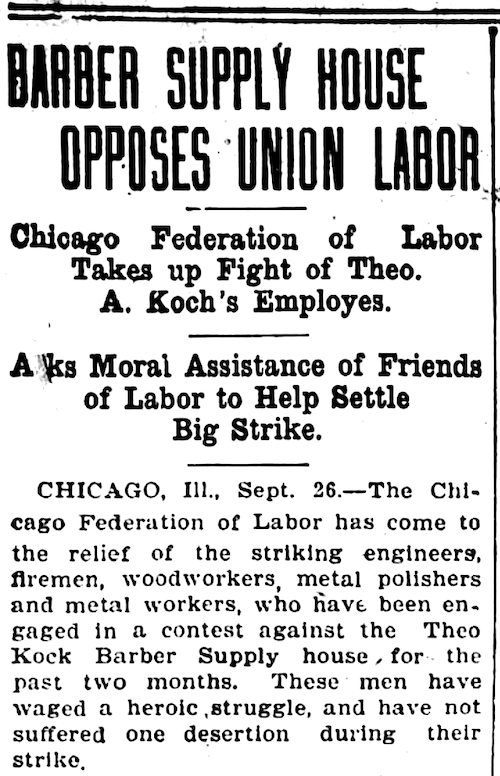

By 1907, things started to get ugly, as Theodore Kochs’ refusal to negotiate a 25-cent pay increase with the metal workers union led to a summer of labor strife, as angry picketers clashed with scab replacement workers outside the Wells Street factory.

“All employees in every department walked out” in July, according to the Inter Ocean newspaper, including 100 woodworkers, 18 metal workers, 14 metal polishers, and a fireman. The strike stretched into September, as Kochs steadfastly refused to bow to the unions’ demands.

“We intend to fight this scab-breeding firm to a finish and have an abundance of money to lick Mr. Kochs to a frazzle,” the striking workers told the Labor World newspaper in a joint statement. “We will hand him the lemon proper! We expect to be injunctionized, but injunctions cut no ice with us. We will continue this fight . . . the boys on strike are enthusiastic and eating the best of buns and biscuits. Remember, money is no object to us. . . . All supply houses have been informed that the Theo. A. Kochs Barber Supply company is ‘Unfair.’”

“We intend to fight this scab-breeding firm to a finish and have an abundance of money to lick Mr. Kochs to a frazzle,” the striking workers told the Labor World newspaper in a joint statement. “We will hand him the lemon proper! We expect to be injunctionized, but injunctions cut no ice with us. We will continue this fight . . . the boys on strike are enthusiastic and eating the best of buns and biscuits. Remember, money is no object to us. . . . All supply houses have been informed that the Theo. A. Kochs Barber Supply company is ‘Unfair.’”

In October, Theodore Kochs went to the extreme of calling the Chicago PD and having 14 striking workers arrested for vagrancy and for “molesting workers who have taken their places.” A judge threw out the case, ruling that “men on strike are not habitual loafers” and could not be held under a vagrancy charge.

If the Kochs Company didn’t suffer much negative press for warring with its own workers, it’s only because the narrative was all too familiar at the time. Besides, all the noise on Wells Street was far enough away from Kochs’ prominent showroom on Randolph Street, where visiting salon owners could check out the latest in “genuine porcelain enameled iron hydraulic barbers’ chairs.”

Maintaining client loyalty may have proven a tad harder during World War I, when anti-German sentiments put any German-sounding business under threat of boycott. At the outset of the 1920s, though, the Kochs Company was still one of the three or four top names in barber supplies, and upon Theodore Kochs’ death in 1924, at the age of 74, he was widely recognized as a respected “pioneer” in his industry.

“He was a Chicagoan for a period covering 55 consecutive years,” according to a posthumous bio in the Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois. “The business which he established and developed here has been a notable success and has been of service to the public throughout all of America. It is but fitting that the annals of this state history shall contain a permanent expression of appreciation to Mr. Kochs, for in point of character, success and charity and good fellowship, his life was worth much to Chicago.”

Kochs left behind an estate of $625,000 (close to $11 million in 2022 terms), most of which was left to his wife Thekla. Amusingly, a substantial sum of $500 was also set aside for Theodore’s own favorite barber, Charles Newton of 5048 Glenwood Avenue.

Robert T. Kochs, son of Theodore and Thekla, took over the company presidency, but he died just a short time later in 1930, at only 53. Timing up with the collapse of the stock market, the 50 year-old business was suddenly on unstable ground heading into the 1930s.

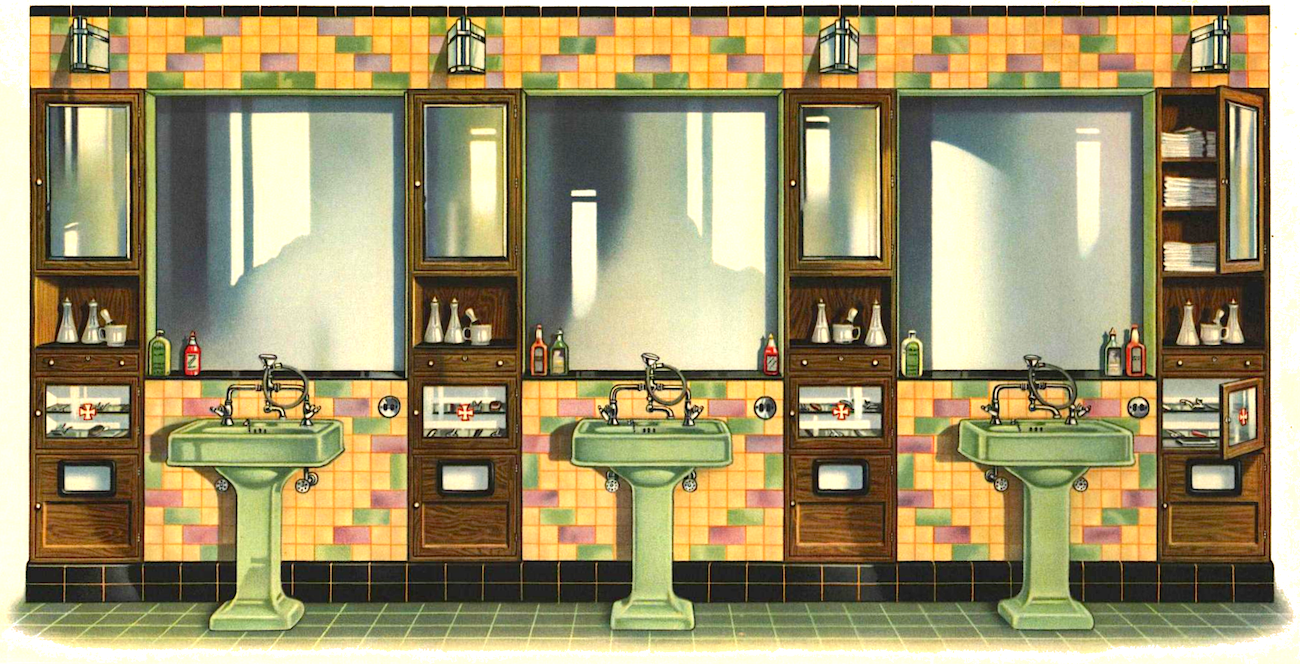

In an effort to stay on or ahead of the industry trends, new management (headed for a time by former company secretary Walter Juede) pushed heavily into Art Deco styles with its chairs and particularly its big mirror case designs in the ‘30s.

[Art Deco mirror cases and washstands, from 1931 Kochs catalog]

“With the introduction of the fixtures shown in this catalog,” read a 1931 sales book, “Kochs takes another important forward step in the promotion of better barber shop interiors. Real interiors—comparable with those of banks, theatres, libraries, offices, hotels and fine club rooms—are made available for barber shops for the first time. Kochs introduces mirror cases of materials used in the finest metropolitan business establishments, styled to the last-minute cry of the modern.”

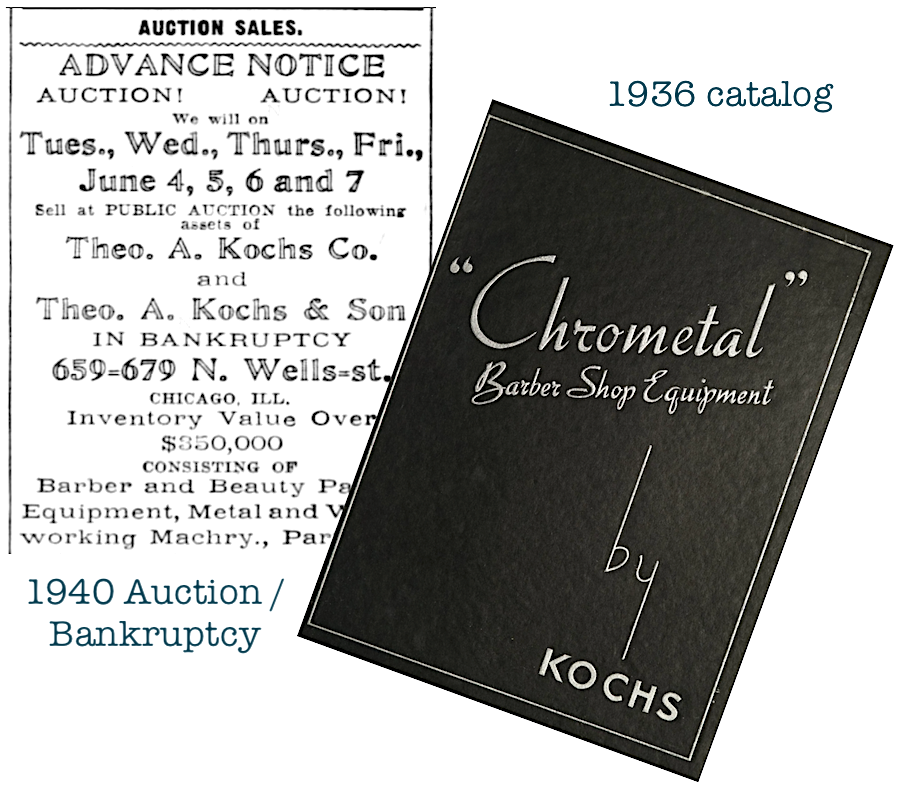

Not every attempt at marketing the modern paid off. In 1936, the company proclaimed that its new “CHROMETAL” barbers’ chair would “herald the beginning of a new era,” but by 1939, the Federal Trade Commission filed a cease-and-desist order against Kochs, citing that a chair with chrome plating alone couldn’t be advertised as true chrome metal, or “chrometal.”

It was, in some respects, the company’s final stumble.

In the spring of 1940, the Theo. A. Kochs Co. filed for bankruptcy, and its five-story factory and all the equipment and machinery therein was put up for public auction.

In the spring of 1940, the Theo. A. Kochs Co. filed for bankruptcy, and its five-story factory and all the equipment and machinery therein was put up for public auction.

The patents and trademarks of the business were ultimately purchased and saved by none other than Emil J. Paidar, head of Chicago’s second biggest barber supply house, the Emil J. Paidar Co., which operated just down the street from Kochs at 1120 N. Wells Street.

Paidar (b.1875) had started out in business as a distributor of Kochs chairs in the 1910s before starting his own manufacturing line in the ‘20s. Now, with the Kochs name under its banner, the Paider Company was able to double its notoriety and greatly expand its business, briefly becoming America’s top barber chair producer in the 1950s.

It was the arrival of post-war competition from Japan, however, that permanently changed the marketplace and effectively wiped out any lasting relevance for the old Kochs brand.

Japan’s Takara-Belmont Company started selling to the U.S. market in 1957. Before that point, the stable of American barber chair makers—led by Paidar and Koken—produced 10,000 chairs per year for the country’s 100,000 barber shops. Takara blew up this relationship almost overnight, both by essentially copying the Paidar chairs and by selling at roughly 70% of the retail cost.

[Emil J. Paidar (1875-1950) purchased the patents and trademarks of Theo. A. Kochs in 1940. After his own death in 1950, Paidar’s company continued to thrive in the 1950s until competition from Japan’s Takara Belmont Company radically changed the U.S. barber supply market in the 1960s]

Representatives of both Paidar and Koken pleaded for government support and tariffs to help them combat the Japanese takeover, but it didn’t come fast enough for Koken, which Takara-Belmont bought out in 1969.

That seemed to be a wake up call for legislators, who then went into overdrive to try and prop up the failing Emil. J. Paidar Company. Former Illinois governor and sitting federal judge Otto Kerner, whose sister May Kerner Carter was on Paidar’s board of directors, arranged for close to $2 million worth of government loans to keep Paidar—and Chicago’s barber supply legacy—alive. The effort turned into a disaster. Otto Kerner was eventually forced to resign in a mail fraud scandal. The Paidar Company went belly up by 1973, and its final factory at 1355 W. 43rd St. was sold off. There would be no more genuine Kochs barber chairs coming down the line in Chicago or anywhere else.

Sources:

“Theo. A. Kochs – patentirter Barbierftuhl” – Staats-Zeitung (Chicago), April 29, 1878

“Barber’s Chair” – U.S. Patent 224, 604 (1880)

Theo. A. Kochs Catalogue, 1880

“Petillon’s New Barber Shop and Bath” – Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1881

Theo A. Kochs Catalogue, 1884

Theo A. Kochs Catalogue, 1888

Theo. A. Kochs Catalogue, 1893

Chicago, the Garden City, by Andreas Simon, 1893

Theo. A. Kochs Catalogue, 1903

“Barber Supply House Opposes Union Labor” – The Labor World, Sept 28, 1907

“Pickets Taken as Vagrants” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 16, 1907

“Theo. A. Kochs, Barber Supply Dealer, Is Dead” – Chicago Tribune, March 14, 1924

“Theodore A. Kochs” – Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois, with Commemorative Biographies, 1926

Standardized Barbers’ Manual – Associated Master Barbers of America, 1928

“Robert Kochs, Barber Supply Maker, Dead” – Chicago Tribune, March 18, 1930

Modern Mirror Cases by Kochs, 1931

Chrometal Barber Shop Equipment, 1936

“Auction: Theo. A. Kochs Co. and Theo. A. Kochs & Son in Bankruptcy” – Chicago Tribune, June 2, 1940

Mechanization Takes Command, by Siegfried Giedion, 1948

“Emil J. Paidar . . . Name to Remember” – Corpus Christi Times, June 28, 1970

“The Great Barber Chair Coup” – Time Magazine, Aug 10, 1970

“Force Behind the Throne” – Riverfront Times, Feb 23, 2000

I have one from barn find it porcelain but vinyl missing just wondering age and it’s worth

How can I view some of the Koch’s catalogs from the late 1800s?

We have 2 of your chairs…. My dad recently passed away and was a barber for over 60 years. Not sure how much they are worth.

I have a Theo A. Kochs barber’s chair and looking to sale it.

Would love if you could forward me any information you are able to share… Just aquired my grandfathers chair and would like to restore it to original conditions.

I’m restoring a1920 Koch chair need a manual and diagram etc

Would there be anyplace to locate parts for a Theo A Koch’s barber chair? Need a head rest in red. Thanks

Hello, I have acquired an original Theo A. Koch barber chair and am restoring it. Trying to find an owners manual or any literature for it has proven to be difficult. I figured this was a great place to reach out to and see if you have any information to help with my processes.

Hi, we have what we believe to be a Koch childrens chair, very unusual one. It is a full size rocking horse, on the Koch base. Would love to see if it is in one of your catalogues. can we send a photo. thank you, Marsha

14173 Theo Koch, Barber Pole can you please tell me the year.

Are you aware of a supplier that makes replacement parts for Kochs barber chairs?

I am an antique furniture restorer in South Africa

Thanking you in advance

I have a Theo Koch chair I am currently restoring. The serial number is 268825. Is there any way you could tell me what year it was manufactured. Thank you

I have a 1955 George Koch’s barber chair trying to see how many was made that year

Theo, Cook’s, barber chair, wood and metal leather seat and back also has separate foot stool the pack and play just says February 17 80-August 14 88. I cannot find another one like it anywhere. Is there anyway you can give me some information

I HAVE A BARBER CAIR THEO A KOCHS WITH FACTORY NUMBER 207276

CAN YOU FIND FROM WHAT YEAR ITS MANUFACTURED?

We have a full barber chair that is from this manufacturer, would you all like it?

Would like to know what year my theo Koch barber chair is?

Hey Glenda,?what did u pay for the chair

I have a Theo A Koch’s wood barber chair great condition interested in value and who might be an interested purchaser. Not sure if the date can anyone help me with info on model or I/d number location

Just purchased a wooden barber chair. Trying to find information

Hi,I have more information on my Theo a Koch Barber Chair.The factory number on the wooden seat base is 161736,please let me know what you find,thanks

I obtained a Theo A. Kochs barber chair through a purchase of a home in Michigan.

It is of museum quality. Can you lead me in the proper direction to sell the piece of history?

Raytown clean up a Theo A Kochs chair for my Uncle, belonged to my Grandpa( Johnathan Koch) would like to know how to date it…

i have a Theo A Kochs chair i have restored i have been told its 1900 to 1915 others have told me 1890s form the upholsterer i am looking to confirm the year the chair was made would you be able to help me in this