Museum Artifact: Thordarson Amplifying Transformer, c. 1920s

Made By: Thordarson Electric Manufacturing Co., 500 W. Huron St., Chicago, IL [River North]

“The Thordarson factory is more than an assembly plant. All phases of transformer manufacturing, engineering, core and case stamping, coil winding, impregnating, enameling, assembly, and testing are done under one roof. . . . It has grown from a small one-man shop to a place of leadership in the field—the largest organization in the world devoted exclusively to the manufacture of transformers.” —Thordarson Electric Sound Amplifier Manual, 1936

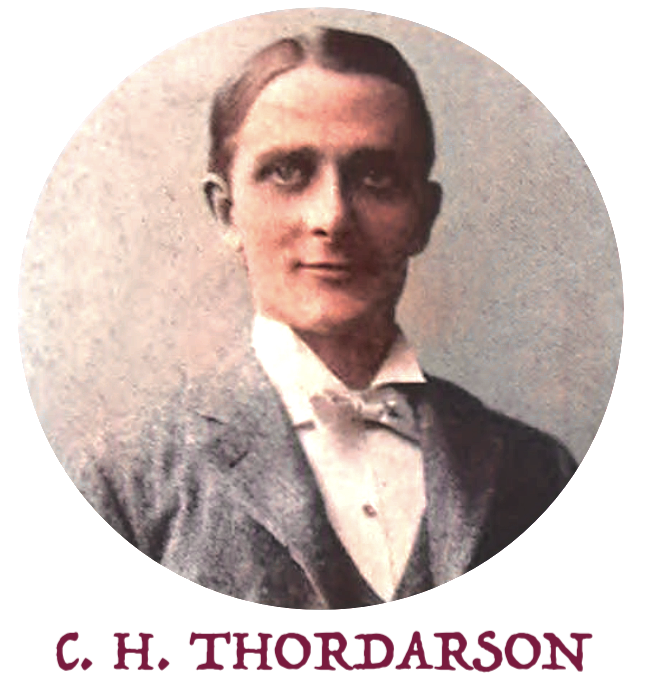

If Nikola Tesla was once the overlooked genius of the early electrical age, elbowed to the fringes by Edison, one could argue that the ghost of Tesla—embraced by 21st century tech bros as a sort of godlike cult hero—is now overshadowing many of his equally pivotal but less brandable contemporaries. Up near the top of this list would be Chester H. Thordarson, the Icelandic wunderkind (or “undrabarn”) who came to Chicago and pioneered many of the most important developments in electric transformers, inductors, and coils in the early 1900s, with well over 100 patents to his credit. According to one anecdote printed long after both of their deaths, Mr. Tesla even supposedly once referred to Mr. Thordarson as “America’s greatest inventor. . . . Every single thing he has done came out of his own head. He has more ideas, more good ideas, than anyone else.”

If Nikola Tesla was once the overlooked genius of the early electrical age, elbowed to the fringes by Edison, one could argue that the ghost of Tesla—embraced by 21st century tech bros as a sort of godlike cult hero—is now overshadowing many of his equally pivotal but less brandable contemporaries. Up near the top of this list would be Chester H. Thordarson, the Icelandic wunderkind (or “undrabarn”) who came to Chicago and pioneered many of the most important developments in electric transformers, inductors, and coils in the early 1900s, with well over 100 patents to his credit. According to one anecdote printed long after both of their deaths, Mr. Tesla even supposedly once referred to Mr. Thordarson as “America’s greatest inventor. . . . Every single thing he has done came out of his own head. He has more ideas, more good ideas, than anyone else.”

The Thordarson “Super Amplifying Transformer” in our museum collection doesn’t tend to grab people’s attention or pull at the nostalgia strings in the way an old Zenith radio or Western Electric telephone can. It’s quite small (less than 6 inches in height) and neither instantly impressive in design nor self explanatory in its function. When it was put into production in the early 1920s, though, the smarter folks in the budding electronics industry paid close attention.

“The new Thordarson 6 to 1 ratio audio frequency amplifying transformer is designed for those desiring a higher transformer ratio than our standard,” read a 1923 advertisement. “Unusually high and constant amplification without distortion over a broad band of audio frequencies. Core is twice the cross-section of that of the ordinary amplifying transformer and is made of special 36 gauge silicon steel. The coils have low distributed capacity. The high Thordarson standard has been maintained throughout.”

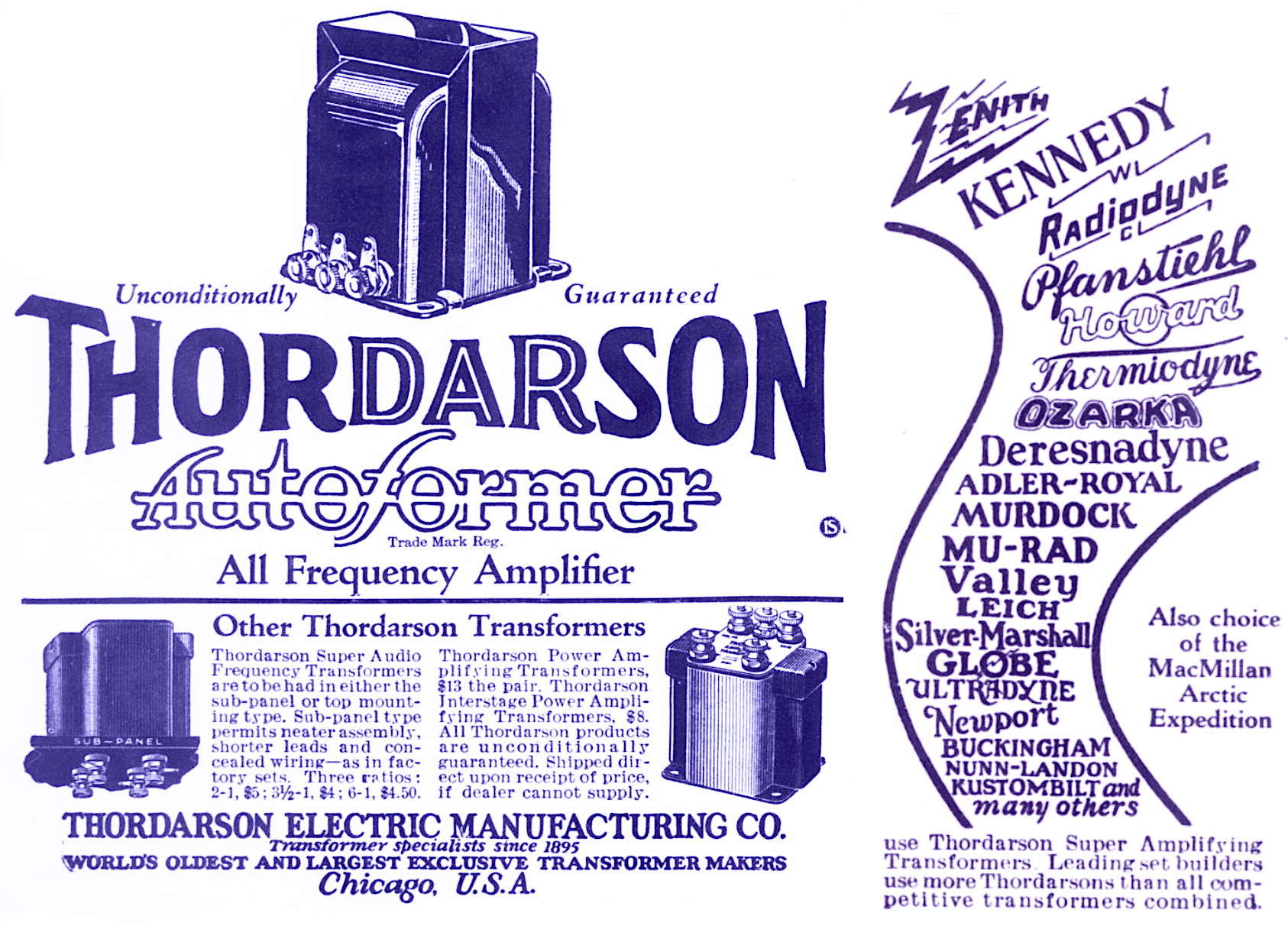

[1925 advertisement showcasing some of the Thordarson amplifying transformers being put to use within the emerging radio industry. The Super Audio model in the bottom left corner, in a 6-to-1 ratio, is the item from our museum collection]

Describing the actual science behind these early transformers in palatable terms is no easier in the 2020s than it was in the 1920s. As museum supporter Larry Chung astutely observed, however, an item like this—and the company that made it— help tell a bigger story that’s well within the understanding of any appreciator of modern gadgets.

“The evolution of transformers, or transforming AC wall-voltage into usable DC, is quite a filter through which to observe the advances in technology as a whole,” Chung told us, “and Thordarson has been there throughout. Radios, TVs, tube PAs, and instrument amplifiers—inductance drives it all, and Thordarson really has such a presence in all of it, albeit behind the scenes.”

History of the Thordarson Electric MFG Co., Part I: The Boy from Iceland

“Thordarson is a man who has never followed beaten paths, and who still avoids them. As the pieces of his story are fitted together, his career develops into a marvelous picture of how a man’s determination to take a certain direction and stick to it may lead him eventually beyond even his dreams.” –Neil M. Clark, American Magazine

“We left Iceland in 1873, when I was five,” Chester Thordarson (born Hjörtur Þórðarson) recalled to journalist Neil Clark as the two discussed his career for a 1926 feature in American Magazine. This would have been right around the same time that Chester’s Chicago based company, the Thordarson Electric Manufacturing Co. was promoting the “Super Amplifying Transformer” in our museum collection.

“We left Iceland in 1873, when I was five,” Chester Thordarson (born Hjörtur Þórðarson) recalled to journalist Neil Clark as the two discussed his career for a 1926 feature in American Magazine. This would have been right around the same time that Chester’s Chicago based company, the Thordarson Electric Manufacturing Co. was promoting the “Super Amplifying Transformer” in our museum collection.

“To people in Iceland, America was almost an unknown country.”

Exotic as the prospect may have seemed, Thordarson’s father was actually following a growing wave of immigration that had seen many of his countrymen abandon the Arctic coast to join a new community of Icelandic transplants on the faraway shores of Lake Michigan. As such, young Chester was left with a very brief but indelible impression of his homeland—formative memories of tending sheep with his sister on the rolling hills; watching the fishing boats out on the cold Arctic waters; and above all else, marveling at the sky lights of the Aurora Borealis and desperately desiring to understand what caused them.

Young Thordarson’s curiosity didn’t waver when his family settled in America, but his opportunities to pursue knowledge were quickly forced down an unconventional path.

“We had little, but it was enough to carry us as far as Milwaukee,” he told Clark. “Here we remained some time while my father was planning what to do and where to settle. But one day he was taken sick, and died soon after. With four children on her hands and absolutely no money, my mother was left to manage our adventures in a strange land, among people speaking an unknown language. . . . I went to a school a couple of sessions during the summer, and learned my letters. And that was about all the schooling I managed to get for a good many years. However, Icelanders are by nature and tradition a very literate people. It is said of them that if they are going on a journey they may sell their clothes to provide money, but they will take along their books. We had a number of books— in the Icelandic tongue—which I could and did read.”

[Thordarson’s personal collection of rare books, starting with a few brought with him from Iceland as a boy, reached a count of over 25,000 by the time of his death]

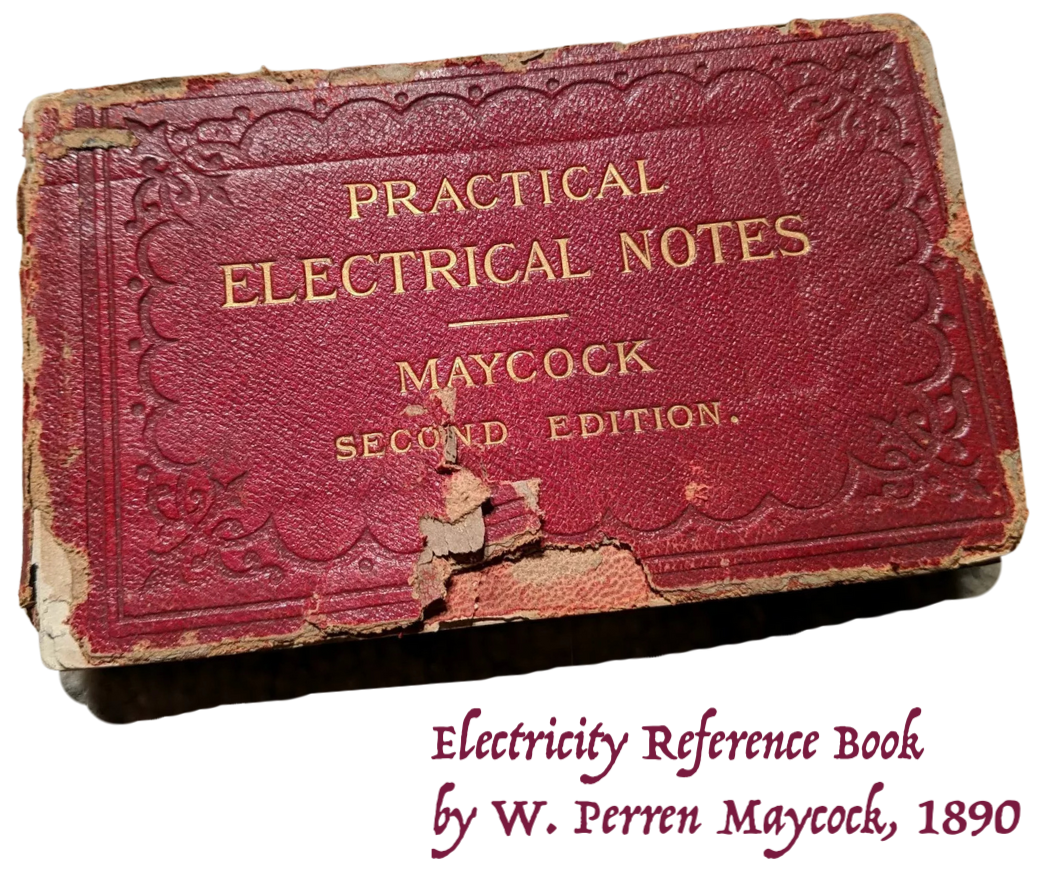

At the age of 13, Thordarson dragged some of those books with him on a 1,000 mile wagon train journey to a new farm settlement in North Dakota’s remote Red River Valley, where he would spend the next five years plowing fields and raising cattle, never setting foot in a classroom. But Thordarson still found daily inspiration from reading, including one specific Icelandic book on the subject of physics.

“During the long North Dakota winters,” Thordarson recalled, “I used to pore over this book until I learned it nearly by heart. In it I found for the first time the definition of a scientific experiment. I have read and heard many other definitions since, but none seems to me to be more clearly stated: ‘An experiment is a question that we place before Nature; and she always answers in a most direct way. If the answer is not what we expected, it is because we did not question correctly. After making several attempts, we learn to question more directly, and the answers we get from Nature will be more to our purpose.’

“I had always been asking questions of Nature. I now decided that I must somehow become a scientist.”

Thordarson, like many young folks in the 1880s, was particularly fascinated by electricity and its potential to dramatically change the world in the years ahead. He was compelled to channel his curiosity into scientific experiments of his own, but didn’t exactly have the optimal set-up living in a place that was off the grid even by pre-grid standards. A change of scenery was desperately needed and would, fortunately, soon present itself.

Thordarson, like many young folks in the 1880s, was particularly fascinated by electricity and its potential to dramatically change the world in the years ahead. He was compelled to channel his curiosity into scientific experiments of his own, but didn’t exactly have the optimal set-up living in a place that was off the grid even by pre-grid standards. A change of scenery was desperately needed and would, fortunately, soon present itself.

“By the time I was eighteen,” Thordarson said, “one of my sisters had married and had gone to live in Chicago. I saw here my opportunity. There were free public schools in Chicago, I knew, and undoubtedly there were also places where a great deal could be learned about electricity. My elder brother was running the farm; I left for Chicago and started to school.”

II. Pinching Pennies

“One of the greatest things I knew was how little I did know! I was keenly conscious of having completed only the seventh grade in school, whereas many of the men around me had been graduated from high school or college. My lack of schooling was a handicap, but I resolved to overcome it by harder work and closer application to study.” –Chester H. Thordarson, 1936

It’s hardly unusual to hear the story of the determined immigrant who carved their own path, ascended to the highest levels of education in America, and then went off to great success in business. Chester Thordarson, despite arriving in the U.S. at a very young age, didn’t benefit from its schools in quite the same way. When he moved to Chicago as an 18 year-old, his limited education and fractured English speaking landed him in a 4th grade classroom with kids half his age; an “embarrassing” circumstance that he accepted with a brave face. “All I wanted was a chance to learn.”

It’s hardly unusual to hear the story of the determined immigrant who carved their own path, ascended to the highest levels of education in America, and then went off to great success in business. Chester Thordarson, despite arriving in the U.S. at a very young age, didn’t benefit from its schools in quite the same way. When he moved to Chicago as an 18 year-old, his limited education and fractured English speaking landed him in a 4th grade classroom with kids half his age; an “embarrassing” circumstance that he accepted with a brave face. “All I wanted was a chance to learn.”

After two years, Thordarson had finished the seventh grade, but with no means of supporting himself, he had to abandon the school track and seek out work, which he found by asking a man from his church (Professor H. V. Richards) for a job at his small scientific appliance firm. He was paid $4 per week in the role, an outrageously low wage even for 1887.

“When you haven’t much, you learn how to make what you have go a long way,” Thordarson told American Magazine. “For one thing, you don’t buy useless articles. I managed by finding where my pennies would buy the most. I lodged in a pretty poor place on the West Side. If I remember correctly, I paid two dollars a week for my room and breakfasts. I walked to work. That left me one dollar each week for other meals, which consisted of stuff bought mostly at bakeries. One dollar remained. With that I bought books.”

Over the next five years, Thordarson educated himself through the three tried-and-true methods outside of the traditional schooling ascent: hands-on work, lots of reading, and meaningful travel—including an adventure through Mexico and up the coast of California that he funded with most of his savings in 1892. “I had a marvelous time, and I came back with a wealth of new ideas and a greater breadth of view. It was like a whole high-school course, all taken in a few weeks.”

[At the age of 26, Chester Thordarson was working for the Chicago Edison Company at the time of the famed 1893 Columbian Exposition, when Edison and Westinghouse were battling to literally outshine each other inside the Electricity Building]

Thordarson returned to Chicago in the midst of the excitement of the Columbian Exposition and all the celebration of innovation that came with it. He was working for the Chicago Edison Company by this point, and almost certainly would have played at least a small role but in the famous “Current War” between Edison and Westinghouse. Within a couple more years, though, Thordarson’s knowledge, ambition, and family responsibilities were making him increasingly impatient being a mere cog in a bigger machine.

“I was twenty-seven years old and I had saved seventy-five dollars when I decided to go into business for myself,” Thordarson said, recalling the launch of his first independent shop in 1895. “I gave up my job, got married, and started the business all at the same time—and all on the seventy-five dollars! I wouldn’t advise anybody else to do the same; and I wouldn’t advise against it. For me, this course turned out happily. I wouldn’t change a thing, not even the times when business came terribly slowly, when we were nearly broke and failure seemed just around the corner. Such experiences are the stuff life is made of.”

III. A Heavy Spark

If Thordarson had made something of a late start into his career as an electrical engineer, he wasted little time solidifying his status in the field. By 1897, his Chicago shop at 82 Market Street was a busy hive of activity, written about favorably in trade publications like the Western Electrician.

“C. H. Thordarson, who for many years has been engaged in constructing and repairing dynamos, motors, transformers, induction coils, etc., has now built up an excellent trade in Chicago and enjoys an enviable reputation among the electrical fraternity,” the magazine proclaimed in an 1897 issue, noting that Thordarson had done work for major manufacturers including the Chicago Telephone Co. and Western Union Telegraph Co. “Mr. Thordarson makes a specialty of winding armatures of any size or system, and his shop is exceptionally well fitted for work of this kind.”

“C. H. Thordarson, who for many years has been engaged in constructing and repairing dynamos, motors, transformers, induction coils, etc., has now built up an excellent trade in Chicago and enjoys an enviable reputation among the electrical fraternity,” the magazine proclaimed in an 1897 issue, noting that Thordarson had done work for major manufacturers including the Chicago Telephone Co. and Western Union Telegraph Co. “Mr. Thordarson makes a specialty of winding armatures of any size or system, and his shop is exceptionally well fitted for work of this kind.”

Around the turn of the century, Thordarson established a proper factory space at 153 S. Jefferson Street (later renumbered to 220 S. Jefferson St. in 1909) and began marketing his firm as a “Maker or Special High Potential Apparatus and Experimental Sets for Schools, Colleges, and Laboratories.” In 1904, he was recruited by a team of electrical engineers at Purdue University to lead the designing and construction of what would become the largest electric transformer in the world—fed from “an alternating current dynamo at 110 volts” and producing in turn “a current at the unprecedented potential of one million volts.”

“Some idea of the enormous electrical pressure may be realized by the layman when it is known that the voltage will send a current through almost any modern insulating material,” the Lafayette Weekly Courier reported at the time. “It will jump through eight foot of dry air, causing a discharge which resembles a bolt of lightning.”

[Two Thordarson advertisements from 1904 and 1905 and four images of the award-winning million-watt Thordarson transformer being constructed in Chicago (in an updated design) ahead of its showcase at the 1915 Pan-Pacific Expo in San Francisco]

Thordarson seemed to take particular delight in how the general public interacted with his super transformer, both in its original showcase at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, and the updated model he brought to the 1915 Panama-Pacific Expo in San Francisco.

“The really interesting events for most people were the evening displays,” he said. “We had a network of wires suspended about thirty-five feet above the ground outside of the building, and we used to charge this every evening with the extraordinarily high voltage at 25 cycles. . . . The current leaped in a brilliant arc four or five feet long, and roared with a sound like thunder that could be heard at a great distance. When we weren’t discharging to the ground but were charging the wires, they made a beautiful display, with luminous coronas around each wire and bright discharges of current at every corner and dead end. People could stand under the wires and get some peculiar sensations. If you held your hand above your head, for instance, there was a bright discharge from your fingertips. You could draw a heavy spark from your neighbor. Any object of metal on your person was likely to feel very uncomfortable.”

“The really interesting events for most people were the evening displays,” he said. “We had a network of wires suspended about thirty-five feet above the ground outside of the building, and we used to charge this every evening with the extraordinarily high voltage at 25 cycles. . . . The current leaped in a brilliant arc four or five feet long, and roared with a sound like thunder that could be heard at a great distance. When we weren’t discharging to the ground but were charging the wires, they made a beautiful display, with luminous coronas around each wire and bright discharges of current at every corner and dead end. People could stand under the wires and get some peculiar sensations. If you held your hand above your head, for instance, there was a bright discharge from your fingertips. You could draw a heavy spark from your neighbor. Any object of metal on your person was likely to feel very uncomfortable.”

Shockingly, there were no comparisons to Thor’s mighty hammer, but nonetheless, Thordarson’s monster transformers brought home gold medals in both 1904 and 1915, and further made a star of their creator.

After officially incorporating the Thordarson Electric Manufacturing Company as its own entity in 1907 (with Joseph W. Watkins as vice president and John A. Brennan as secretary), Chester soon set up a larger plant and lab down the road at 500 S. Jefferson Street. A profile in a 1911 issue of Popular Electricity noted that Thordarson now employed more than 100 workers at his Chicago headquarters, and that, therein, “you will find transformers, high frequency apparatus, electric welding and heating appliances, and experimental equipment of a multitude of kinds — special types every one, which are individually the products of his inventive genius. . . . Almost every university and technical school in the country bears evidence in its physical and electrical laboratories of the work of Thordarson.”

[Inside the Jefferson Street factory, circa 1910s. Top Left: Shipping Department, Top Right: Core Iron Press Room, Bottom Left: Hand Winding of Transformer Filament, Bottom Right: Sheet Metal Press Room. Wisconsin Historical Society]

Despite his notoriety for building giant, super-powerful transformers, the Popular Electricity article also complimented Thordarson for going to work “just as enthusiastically” on the design of “a little transformer to ring a doorbell.”

By the dawn of the 1920s, Thordarson products were now almost omnipresent necessities of the new electrical world, used in everything from automobiles and telephones to radios, sign lighting, welding, and electric toy train sets.

[A set of Thordarson magazine advertisements from the 1910s, showing the growing range of uses for the company’s transformer line]

IV: Out on an Island

“The trademark of efficiency in wireless transformers is the word THORDARSON on the maker’s name-plate.” –advertisement, 1917

As radio conquered the world in the 1920s, Thordarson Electric was taking something of a victory lap. In 1922, the company migrated to a six-story factory building at 500 W. Huron Street, providing more than four times the square footage of the previous HQ; much needed to keep up with an overwhelming demand for wireless transformers.

As radio conquered the world in the 1920s, Thordarson Electric was taking something of a victory lap. In 1922, the company migrated to a six-story factory building at 500 W. Huron Street, providing more than four times the square footage of the previous HQ; much needed to keep up with an overwhelming demand for wireless transformers.

As one of the firm’s 1923 catalogues boasted, “Radio is far from being a new field to Thordarson. 1904 marked the building of the first Thordarson spark transformer. The old time HAM operator has a tender spot in his heart for this now almost extinct ‘rock crusher.’ With equal success he is now using Thordarson C. W. filament heating and plate supply transformers. Today the Thordarson amplifying transformer is used in over thirty of the better standard makes of receiving sets, is sold by progressive dealers and jobbers everywhere, and is providing sweet and undistorted music for thousands of radio fans the world over.”

[1929 advertisement]

C. H. Thordarson, now approaching the age of 60, was a millionaire and widely revered by many of the younger inventors and executives leading the radio revolution. He was happy to rub shoulders with some of these men—Eugene F. McDonald of the Zenith Radio Corp. was a particular comrade—but the fraternization didn’t take place in the usual venues of Chicago’s high society. Instead, Thordarson enjoyed welcoming influential guests to the rather unique vacation estate he’d established on Rock Island, a 1,000-acre wooded retreat in Lake Michigan, off the northeast coast of Wisconsin. He’d begun purchasing land there in 1910, and during the ‘20s, Thordarson poured huge amounts of his wealth into building a sort of grand tribute to his Icelandic roots. A massive limestone boathouse, modeled after the parliament building in Reykjavík, was designed by noted Chicago architect Frederick Dinkelberg and constructed largely by a team of Icelandic immigrants from the region.

This unusual building, which has since been added to the National Register of Historic Places, welcomed the yachts of everyone from Thomas Edison and Henry Ford to political fat cats like Chicago mayor Big Bill Thompson. After disembarking, guests to the island would meet in the boathouse’s upper floor, the Viking Hall. In later years, some were fortunate enough to see Thordarson’s legendary library of rare books; a collection that had steadily grown to the many thousands, first housed in Thordarson’s factory office, and later on Rock Island, with subjects ranging from Icelandic folklore to one-of-a-kind science and natural history volumes (the University of Wisconsin’s Memorial Library still has more than 5,000 of Thordarson’s books in their Department of Special Collections, having acquired them shortly after his death).

[Top Row: Chester Thordarson’s Rock Island Boat House, under construction in the mid 1920s (left) and in its current condition as a landmark of the Rock Island State Park 100 years later. Bottom Row: The Viking Hall above the boat house, present day, and a party readying to board the yacht of Zenith Radio president Eugene McDonald (second from left) in 1924 en route to Rock Island. Chester Thordarson is the fourth of the men standing from the right, and Chicago mayor Bill Thompson is the fifth from the left. From Dick Purinton’s 2013 book Thordarson and Rock Island.]

“The guiding thought in the Thordarson library,” as writer J. Christian Bay wrote in 1929 for the journal of the Bibliographical Society of America, “is the development of a valid view of life. The many books, the beautiful bindings, the interesting provenance —all this must serve for the purpose of demonstrating that life is worth living. History, science, art—all this would be of little avail if the fifteen hundred mechanics and electricians doing the necessary work day by day in the shops and offices [of Thordarson Electric] were estranged from their quiet, thoughtful chief, who finds an equal joy in being familiar with his machines and in pondering over the message of his noble and remarkable books. Here, for the first time, I try to quote Mr. Thordarson verbally: ‘We pay the highest salaries the business can afford, and we try to treat one another in such a way that all of us may come and go with joy in this building.'”

While Thordarson supposedly had grand plans for even more building projects on Rock Island, he was also dedicated to preserving the natural wonders of the land, which helped lead to its re-establishment as a public state park in the 1960s.

While Thordarson supposedly had grand plans for even more building projects on Rock Island, he was also dedicated to preserving the natural wonders of the land, which helped lead to its re-establishment as a public state park in the 1960s.

In some respects, Chester Thordarson’s focus on Rock Island, and the enormous long term investment he’d made thereon, helped protect him from putting too much of his personal fortune into less noble things . . . like the stock market. While some of his associates—including the aforementioned architect Dinkelberg—were permanently ruined financially by the market crash of 1929, Thordarson was mostly unscathed. His business, however, was soon facing the same precipitous swoon as most of its competitors, with profits cratering during the first few years of the 1930s.

Finally, in 1936, a year shy of his 70th birthday, Chester Thordarson had a meeting with another one of his long time friends and associates, Dr. Charles F. Burgess of the Burgess Battery Company. In the midst of its own Depression-related slide, the Burgess company—which was headquartered in Madison, Wisconsin, but operated facilities in Moline and Freeport, Illinois—seemed a logical candidate for a merger, with the goal of aiding both ailing businesses. The deal was finalized in October of ‘36, and Thordarson Electric was re-framed as a subsidiary of Burgess, with the Chicago factory still in operation and Chester still acting as president (with Charles Burgess as chairman).

[Top Left: Thordarson Sound Laboratory, 1936. Top Right: Thordarson meets with Charles Burgess ahead of his merger with the Burgess Battery Co., 1930s. Bottom: 1929 ad, 1931 ad, and 1938 catalog]

V. The Thordarson Team(s)

“It is the job of the American radio industry to provide ships and planes with the indispensable equipment that constitutes their vital nerve systems, and you and I here at Thordarson are not only building the heart of almost every communications system, but we are also continually developing new ideas and equipment to keep our armies constantly supplied.” —Thordarson company newsletter (Thordar News), November 1943

The financial lifeline from Burgess was particularly well timed, as it allowed Thordarson Electric to stabilize its resources just in time for its biggest call to action. Like so many other Chicago factories, the facility on Huron Street was repurposed for government defense contracts during World War II, including the production of transformers that were put to use in tanks, subs, ships, aircraft, detection systems, and signal warning devices.

The financial lifeline from Burgess was particularly well timed, as it allowed Thordarson Electric to stabilize its resources just in time for its biggest call to action. Like so many other Chicago factories, the facility on Huron Street was repurposed for government defense contracts during World War II, including the production of transformers that were put to use in tanks, subs, ships, aircraft, detection systems, and signal warning devices.

The factory reached its highest ever production levels in 1943 and was awarded an Army/Navy “E” Flag for excellence that spring.

“To all of us who work here at Thordarson,” the Thordar-News staffers wrote after the E Flag announcement, “seeing the ‘E’ pennant flying from our building should be a cause for a pardonable amount of chest expansion. But, above all else, it should cause us to reflect soberly on what we, as individuals, are contributing to the war effort. It should make us mindful that only through doing our individual parts . . . only through cooperating with our fellow workers and taking an unselfish attitude at all times, can we hope to put forth our level best.”

Many of the factory craftsmen who’d been hired just before the war were now reading their copies of the Thordar News from opposite ends of the globe, having been called into military service themselves.

“Dear Gang,” Navy radioman Mort Maximini wrote back to his co-workers in 1944, “I just received the February issue of the Thordar News and really appreciate your kindness in sending it to all of us in the Service. I am out here somewhere in the South Pacific, where it is plenty hot, and am always thinking of how nice things were in dear old Chicago. The one thing I especially enjoy in the paper is the sports page, which Mitchell Stevens does a swell job on. I sure wish I was back there, now that it is spring and baseball just starting. I always got a kick out of playing on the Thordarson team. Lots of luck to this season’s team. In the radio shack aboard ship, we have a number of your transformers in our receivers, so keep up the good work. We really need them. Say hello to the gang in the testing department and give them my regards!” [Mort ultimately returned safely from the war and rejoined Thordarson, where his wife Lucy also worked. He died in 1978]

“Dear Gang,” Navy radioman Mort Maximini wrote back to his co-workers in 1944, “I just received the February issue of the Thordar News and really appreciate your kindness in sending it to all of us in the Service. I am out here somewhere in the South Pacific, where it is plenty hot, and am always thinking of how nice things were in dear old Chicago. The one thing I especially enjoy in the paper is the sports page, which Mitchell Stevens does a swell job on. I sure wish I was back there, now that it is spring and baseball just starting. I always got a kick out of playing on the Thordarson team. Lots of luck to this season’s team. In the radio shack aboard ship, we have a number of your transformers in our receivers, so keep up the good work. We really need them. Say hello to the gang in the testing department and give them my regards!” [Mort ultimately returned safely from the war and rejoined Thordarson, where his wife Lucy also worked. He died in 1978]

With many Thordarson workers like Mort now serving overseas, the Chicago plant recruited dozens of new specialists during the war, including an influx of women and people of color. Activities like sports clubs, “victory rallies,” and holiday parties helped build camaraderie during this period, not just among the Thordarson workers, but across the city, as the factory’s softball and basketball teams would square off in matches with clubs from many of the other major wartime manufacturers, including Stewart Warner, Bell & Howell, Seeburg, Victor Adding Machines, and Scott Radio. Reports of these contests and other new developments were reported in the Thordar News each month, further creating a shared identity among the new cohort at 500 West Huron.

[Left: The Thordarson basketball squad won three straight YMCA industrial league titles during the war years. Right: The staff of the Thordar-News kept the newsletter going not just for the workers in Chicago, but for those who’d left their jobs to serve in the war.]

[Left: The Thordarson basketball squad won three straight YMCA industrial league titles during the war years. Right: The staff of the Thordar-News kept the newsletter going not just for the workers in Chicago, but for those who’d left their jobs to serve in the war.]

Shortly before the end of the war, in January of 1945, Chester H. Thordarson died at the age of 77 after a long illness, leaving behind his wife Juliana and sons Dewey and Triggvi. His company had just marked its 50th anniversary.

Thordarson’s legacy was perhaps best summed up by one of his friends and fellow Icelandic-Americans, a Minnesota-born U.S. Navy officer and future politician named Val Bjornson. While stationed in Iceland for the Navy during World War II, Bjornson came upon a “storehouse of transformers and other electrical apparatus” on a remote mountain top that the British were using for radio communications. The equipment was labeled Thordarson Electric Company, Chicago. For Bjornson, this was “an almost symbolic development. . . . The output of this man’s genius and technical skill had returned to a military installation about 100 miles from the spot where he had been born.”

VI. The Second Half-Century

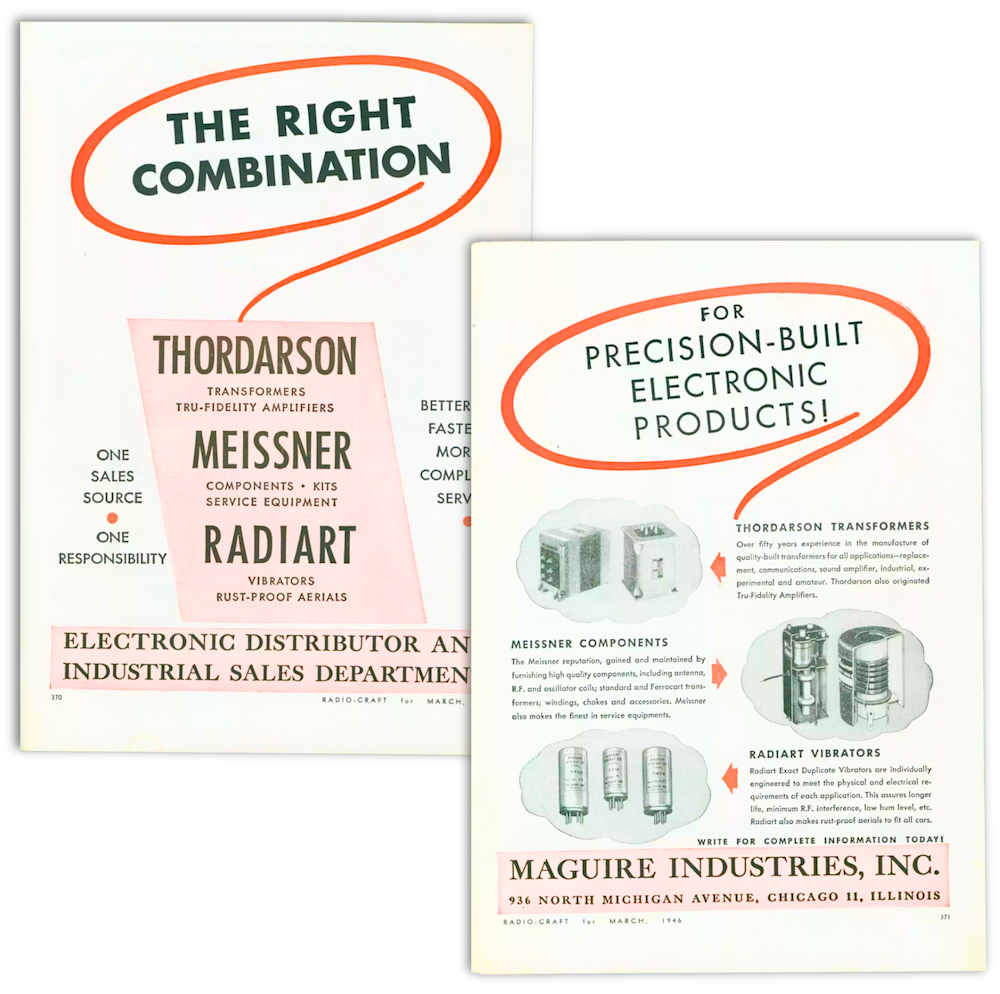

A year before Chester Thordarson’s death, the majority stock ownership of the business had moved from the Burgess Battery Co. to Maguire Industries, aka the Auto-Ordance Co., a weapons manufacturer best known for creating the favorite weapon of every blood-thirsty Chicago gangster: the Thompson submachine gun, or “Tommy” gun. Maguire was look to diversify its products beyond weapons after the war, and with Mr. Thordarson himself now out of the picture, the decision was made to merge Thordarson Electric into Maguire Industries as a subsidiary in 1945, with Thordarson’s vice president L. G. Winney moving over to the same role with Maguire.

Around the same time, Maguire had also acquired the Meissner Manufacturing Co. of Mt. Carmel, Illinois—a radio manufacturer—and by 1950, the decision was made to consolidate the two like-minded subsidiaries into one.

Around the same time, Maguire had also acquired the Meissner Manufacturing Co. of Mt. Carmel, Illinois—a radio manufacturer—and by 1950, the decision was made to consolidate the two like-minded subsidiaries into one.

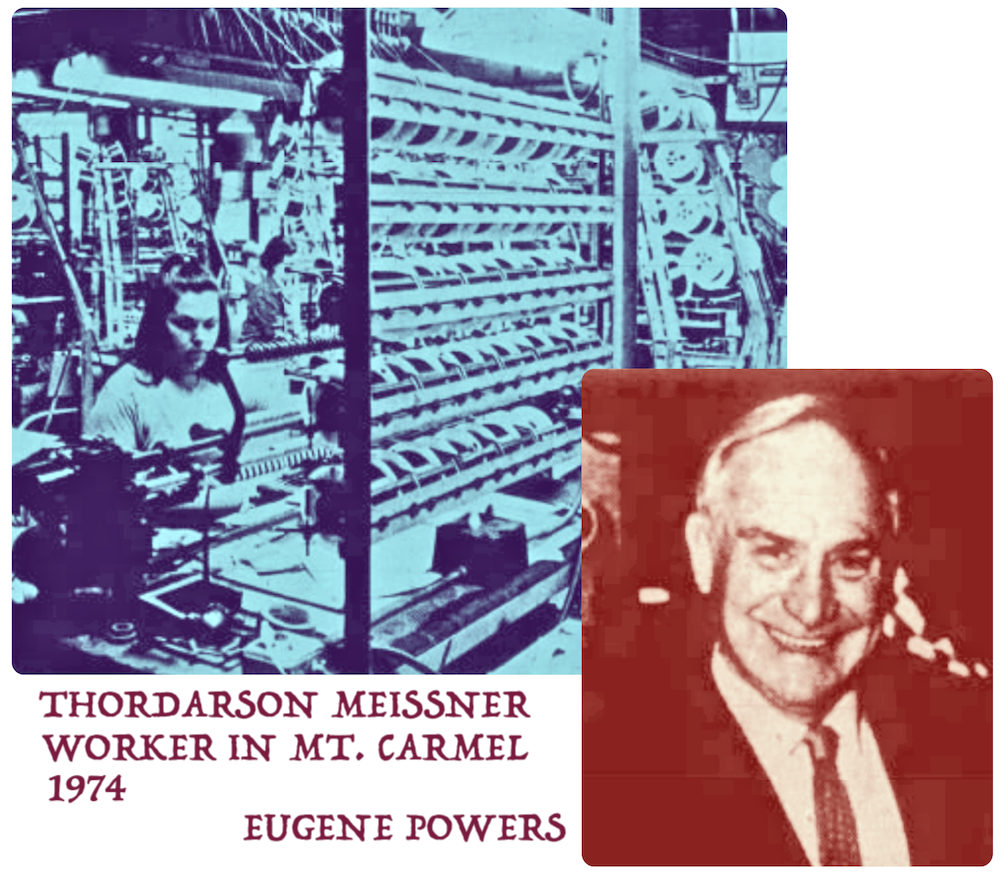

As Maguire’s executive VP Eugene Powers recalled in a 1995 article, “Both Thordarson and Meissner had fared badly during the first five postwar years. Thordarson had committed to equip the U.S.-Canada early warning system stretching across Alaska and Western Canada, to detect the approach of hostile planes. The contract was finally completed in 1950, but at a large loss to Thordarson. The work tied up most of Thordarson’s engineering and production facilities, thus preventing the company from participation in the rapidly emerging television market.

“At the request of the parent company I agreed to stay on and manage the business for a few months. I became interested in the rehabilitation of Thordarson and stayed on for the next 27 years!”

Powers ultimately made a success out of the new Thordarson-Meissner entity, but it came at a considerable cost, as the first major step involved shutting down the Chicago plant on Huron Street after 30 years and moving all production to Meissner’s Mt. Carmel facility. While all the leading talent from the Thordarson plant were welcomed to migrate to Mt. Carmel, Powers claimed that this did not go to plan: “A group of Chicago key employees who were helping to make the move, and who had agreed to stay with the combined facility in Mt. Carmel, in effect were taking off with some of the basic machinery and drawings,” Powers recalled four decades later. “As the equipment arrived in Mt. Carmel, they were unloading it into their own vehicles for transport back to Chicago to a plant which they had set up there. The plot was discovered by loyal Mt. Carmel employees, and reported to authorities. Several of the Chicago people were caught red-handed by the Wabash County Sheriff and taken into custody.”

Powers ultimately made a success out of the new Thordarson-Meissner entity, but it came at a considerable cost, as the first major step involved shutting down the Chicago plant on Huron Street after 30 years and moving all production to Meissner’s Mt. Carmel facility. While all the leading talent from the Thordarson plant were welcomed to migrate to Mt. Carmel, Powers claimed that this did not go to plan: “A group of Chicago key employees who were helping to make the move, and who had agreed to stay with the combined facility in Mt. Carmel, in effect were taking off with some of the basic machinery and drawings,” Powers recalled four decades later. “As the equipment arrived in Mt. Carmel, they were unloading it into their own vehicles for transport back to Chicago to a plant which they had set up there. The plot was discovered by loyal Mt. Carmel employees, and reported to authorities. Several of the Chicago people were caught red-handed by the Wabash County Sheriff and taken into custody.”

Whether viewed as criminal conspiracy or an understandable act of revolt by the employees of a shuttered factory, this was a rough final chapter for the Chicago era of Thordarson Electric. None of the key contributors from Huron Street wound up joining the 200-person staff in Mt. Carmel, and so the second half-century of Chester Thordarson’s business became something more like a soft reboot under the guidance of Eugene Powers.

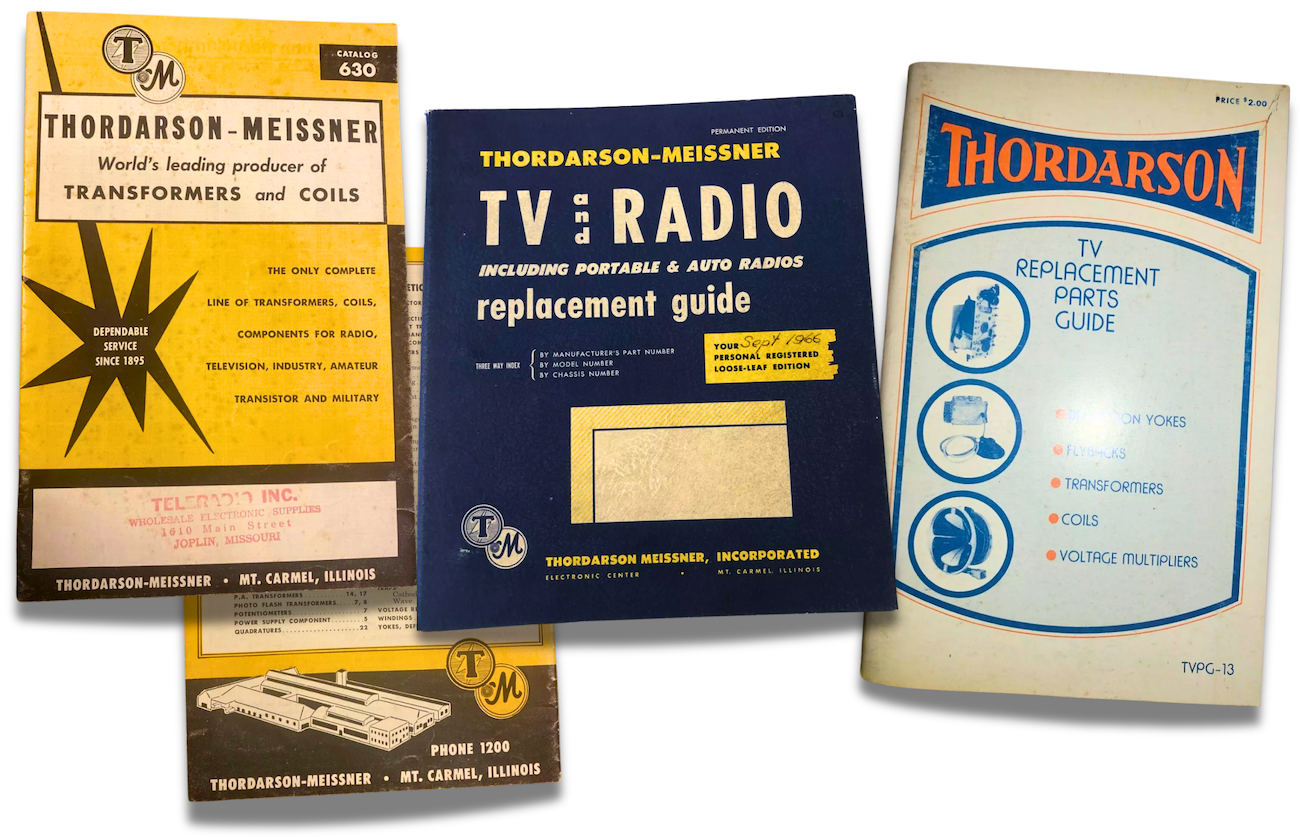

In its second life, Thordarson Meissner pivoted to the world of television repair supplies, finding great success first as a supplier, then as a manufacturer, as the company absorbed many specialist TV component firms and moved their production to Mt. Carmel and a couple other satellite facilities. By the 1970s, Thordarson Meissner employed more than 1,000 men and women, with half of them working at the Mt. Carmel plant. “Chester Thordarson would have been proud of the men and women in Mt. Carmel,” Powers wrote, “who achieved results in products Chester dreamed of.”

[Thordarson-Meissner catalogs from the Maguire Industries era, ranging from the 1950s (left) to 1966 (center) to 1980 (right)]

Shortly before Thordarson Meissner’s 100th anniversary in 1995, the company—having already been reduced to about 40 workers—was purchased by John Golko, who kept the Mt. Carmel plant in operation for several more years until filing for bankruptcy in 1999. A Nevada company called TRC Manufacturing apparently acquired the last vestiges of the business at that point, and a seemingly re-imagined version of Thordarson-Meissner, aka Thordarson Magnetics, carried on into the 2010s from a plant in Las Vegas, specializing in Chester Thordarson’s original bread and butter: transformers.

Unfortunately, the corporate website for this late-period Thordarson company has remained dormant since 2015, and its former Vegas HQ is now closed. As best we can tell, the once illustrious Thordarson Electric MFG Co. went quietly into the night without so much as a headline or an obituary. Only the former Chicago factory on Huron Street (long since converted into lofts) remains as a proper monument . . . along with a Viking boathouse on an island in Lake Michigan.

Sources:

“C. H. Thordarson . . .” – Western Electrician, Sept 11, 1897

“To Give Current of Million Volts” – Lafayette Weekly Courier (Indiana), May 5, 1905

“Electrical Men of the Times: C. H. Thordarson” – Popular Electricity, Jan 1911

“The Flare of Northern Lights Started Thordarson on His Quest” – American Magazine, Dec 1926

“Bibliotecha Thordarsoniana: A Private Collection of Scientific and Technological Literature,” by J. Christian Bay, Bibliographical Society of America, 1929

“Burgess Concern Buys Thordarson” – The Dispatch (Moline, IL), Oct 3, 1936

“C. H. Thordarson Dead; Founded Electric Firm” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 8, 1945

“Thordarson Electric Merges with Maguire” – Pittsburgh Press, July 5, 1945

“Find Employee List Growing at Plant Here” – Daily Republican Register (Mt. Carmel, IL), Nov 27, 1951

“Noted Inventor Had Roots in Windsor” – Capital Times (Madison, WI), Sept 17, 1958

“Meissner’s Corporation Base” – Daily Republican Register, Aug 19, 1974

“Rock Island Park has an Electrified History” – Wisconsin State Journal, Oct 10, 1976

Rock Island, by Conan Bryant Eaton, 1979

“Thordarson: A Century of Service” – Daily Republican Register, June 8, 1995

“Production Continues at Thordarson-Meissner” – Daily Republican Register, March 5, 1999

Thordarson and Rock Island, by Dick Purinton, 2013

I had found this in my house somone recently installed it. I’m curious on what this device does

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chester_Thordarson?wprov=sfti1