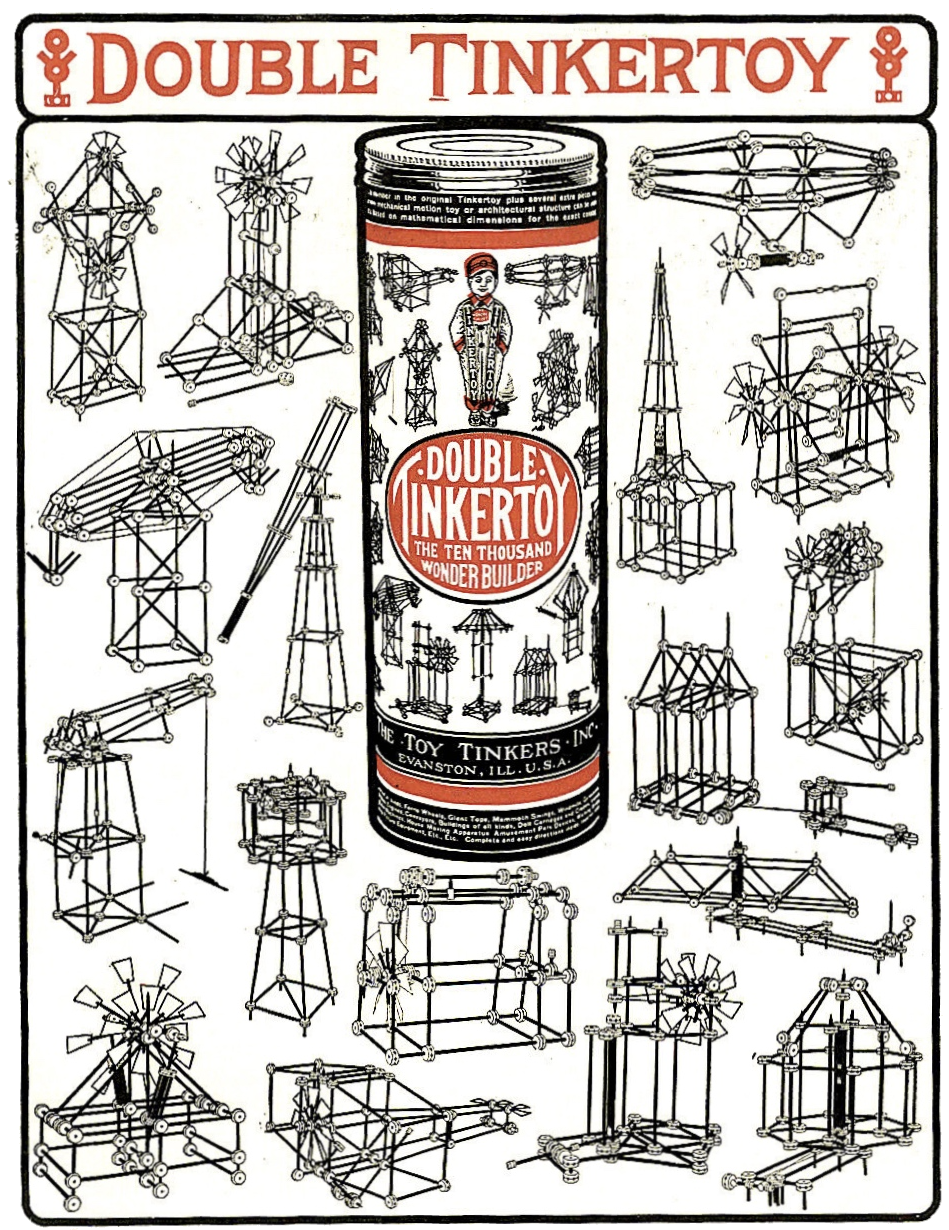

Museum Artifact: Tinkertoy Wonder Builder Set, c. 1930s

Made By: The Toy Tinkers, Inc., 2012 Ridge Ave., Evanston, IL

“Toys haven’t been considered a ‘regular business’ in the United States until very recent years. We relied on Japan and Europe to supply our children; and, by and large, a very inferior article they supplied. But toys are coming up here in a business way these days, and Chas. H. Pajeau, the man who put Tinker Toys across, is one of the leaders in the new industry.” —System magazine, 1918

For 60 years, Evanston, Illinois was the proud home of Tinkertoy—a product inspired by the Pythagorean theorem and supported by the old adage: “a stick and spool will amuse a child.”

For 60 years, Evanston, Illinois was the proud home of Tinkertoy—a product inspired by the Pythagorean theorem and supported by the old adage: “a stick and spool will amuse a child.”

Along with the Erector Set and Lincoln Logs, Charles Pajeau’s simple model-building kits helped launch a construction toy “fad” that’s now carried on for well over a century. Even in the age of endless digital distractions, these tangible, task-oriented toys represent a $9 billion industry—about 10 percent of the global toy market (as of 2020)—with quite a few of the originators still leading the way. Tinkertoy is one of them, although manufacturing has long since left Illinois, landing most recently in a Hatfield, Pennsylvania plant owned by Basic Fun, Inc.

As with many of the 20th century’s most enduring toy brands, the success of Tinkertoy is often attributed to a technical innovation, but it probably hinged just as much—if not more so— on a savvy marketing campaign. Good timing didn’t hurt either. When Pajeau and his business partner Robert Pettit launched their new enterprise in 1914, they couldn’t have anticipated how World War I would necessitate a tectonic shift in how department stores and mail order catalogs sourced their toys. The culture was changing, too, as the very idea of toy shopping—once considered only a seasonal Christmastime activity—was now part of a family’s year-round budget.

Even so, Tinkertoy wasn’t instantly recognized as a winner by the toy dealers of America. Its creators would have to scratch and claw and get a little bit theatrical to prove just how entertaining a tube full of sticks and spools could be.

History of Tinkertoy, Part I: The Monument Man

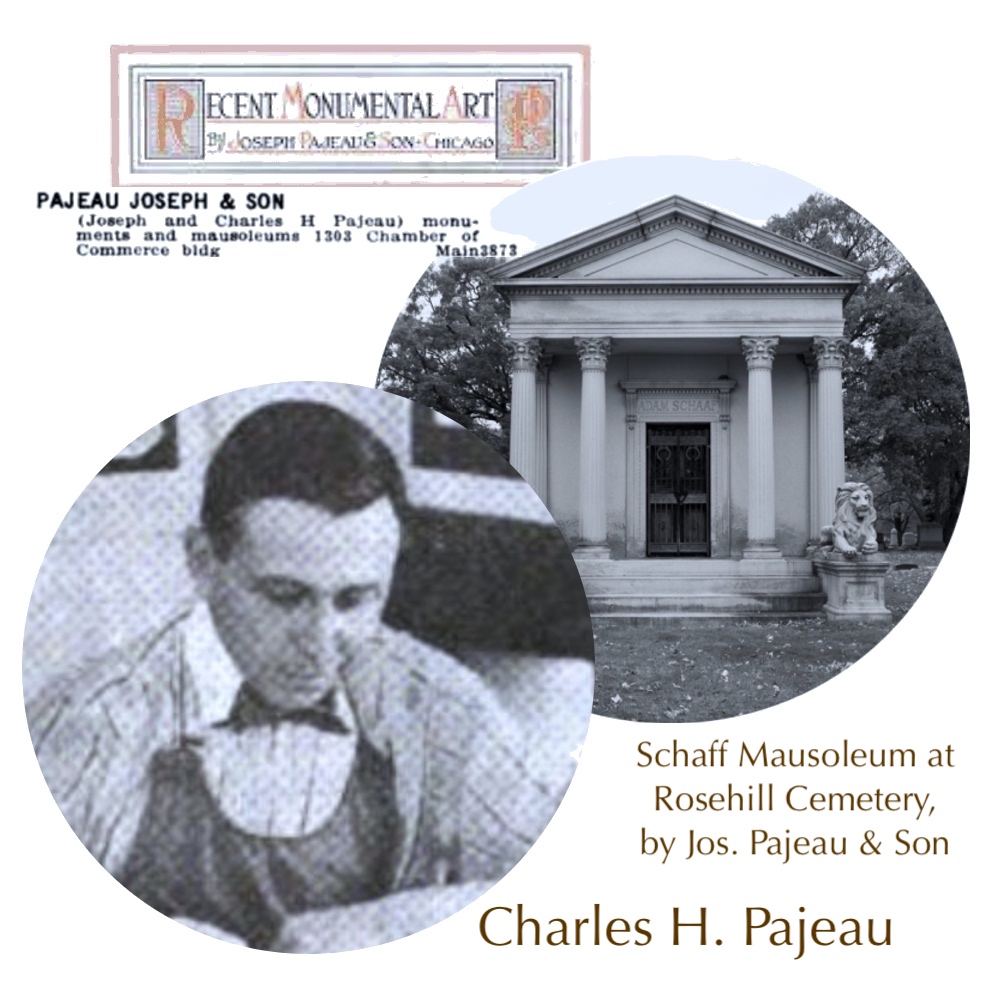

Unlike his local toy-making rival John Lloyd Wright—creator of Lincoln Logs and son of the famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright—Charles Hamilton Pajeau didn’t have the weight of great public expectations hanging over him at a young age. Born in 1875 and raised on the South Side of Chicago, he attended the Harvard School for Boys (a noteworthy prep school) and Hyde Park High School, then dutifully joined his father in the family business—producing granite monuments and mausoleums for some of the city’s wealthier, recently deceased citizens.

“I never liked it,” Pajeau later admitted in a 1918 interview. “Several sides of it were disappointing to me. And so, more as a relief from the monument business, I guess, than for any other reason, I took to experimenting with toys.”

“I never liked it,” Pajeau later admitted in a 1918 interview. “Several sides of it were disappointing to me. And so, more as a relief from the monument business, I guess, than for any other reason, I took to experimenting with toys.”

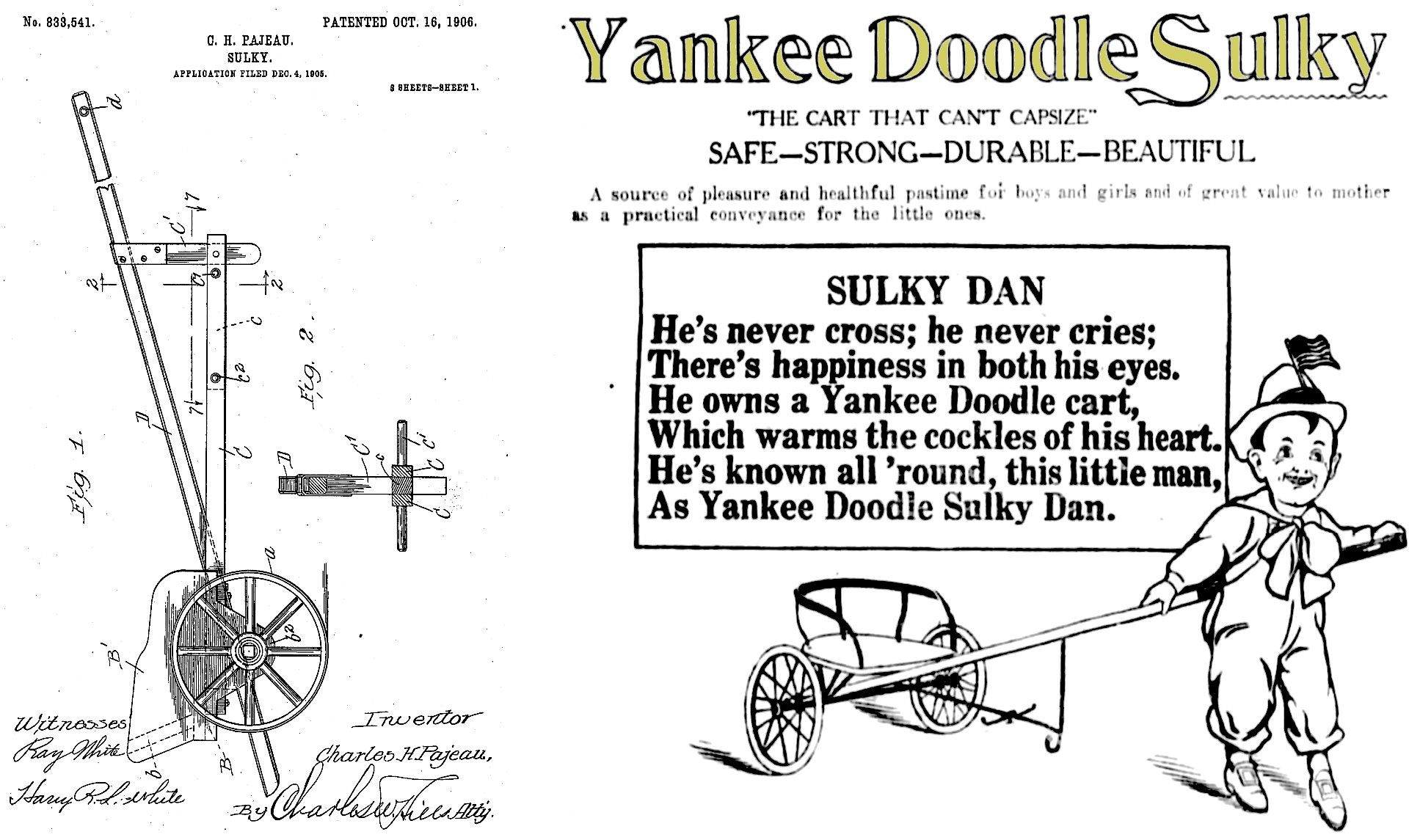

The experimenting went on for a while, too. After a brief flirtation with bicycle design in the late 1890s, Pajeau received a patent for his first legit toy invention in 1906—a child’s two-wheel pull-cart that was marketed nationwide as the “Yankee Doodle Sulky.” For a brief moment, it looked like Charlie was destined to become the Radio Flyer guy rather than the TinkerToy guy, but the Yankee Doodle Sulky eventually spun out when its distributor collapsed, putting Pajeau back at the drawing board and back in the granite business. It wasn’t until 1915, at the age of 40, that he finally left the firm of Joseph Pajeau & Son for good, pursuing the toy dream full-time.

By now, Charles had a home in Evanston with his wife and daughter (both named Grace), and enough money from the monument trade to fund his further forays into toy tinkering. This is where the usual legend of Tinkertoy tends to begin.

[Left: 1906 patent for Pajeau’s “sulky” children’s cart. Right: Newspaper ad for the “Yankee Doodle Sulky,” 1908]

II. Pajeau Meets Pettit

In the days before everybody riding on the L train had a smartphone to stare into, conversations were often struck up with fellow passengers. And in those conversations, life-changing relationships were occasionally formed. For Charles Pajeau, it was a not-so-chance encounter with one of his regular acquaintances on the train from Evanston to Chicago. Pajeau was heading into the Pajeau & Son offices downtown, while the other man—Robert Pettit (b. 1881)—was en route to the Chicago Board of Trade, where he braved the herds as a grain broker. As the two frustrated, middle-aged businessmen got to talking more regularly, though, the topic shifted to their mutual interest in a career change.

By 1913, Pajeau was trying to bounce back from the Yankee Doodle Sulky fallout and develop a new, more cost-effective toy line to finally usher him out of the gravestone racket. Pettit, meanwhile, had recently entered the automobile business, creating a car transport service between Evanston and Chicago called the James Motor Express Co. (which, as a commuter himself, might have been established for self-serving reasons).

By 1913, Pajeau was trying to bounce back from the Yankee Doodle Sulky fallout and develop a new, more cost-effective toy line to finally usher him out of the gravestone racket. Pettit, meanwhile, had recently entered the automobile business, creating a car transport service between Evanston and Chicago called the James Motor Express Co. (which, as a commuter himself, might have been established for self-serving reasons).

Pettit was a Pennsylvania native and a Princeton grad; he married a classmate’s sister, Rachel Hazelhurst, right after college, and wound up living with her well-to-do family in Evanston. According to his grandson, Bob Martin, Pettit was the quintessential “straight-laced, competent business manager,” contrasting with the more witty and extroverted Pajeau. But Pettit also had a sensitive side. “Having lost his mother at age 2 and his father at 13, he endured a childhood of grief and disruption,” Martin says. A life in finance wasn’t fulfilling, but getting into a field where he could serve a greater good—be it public transport or children’s education—had a strong appeal.

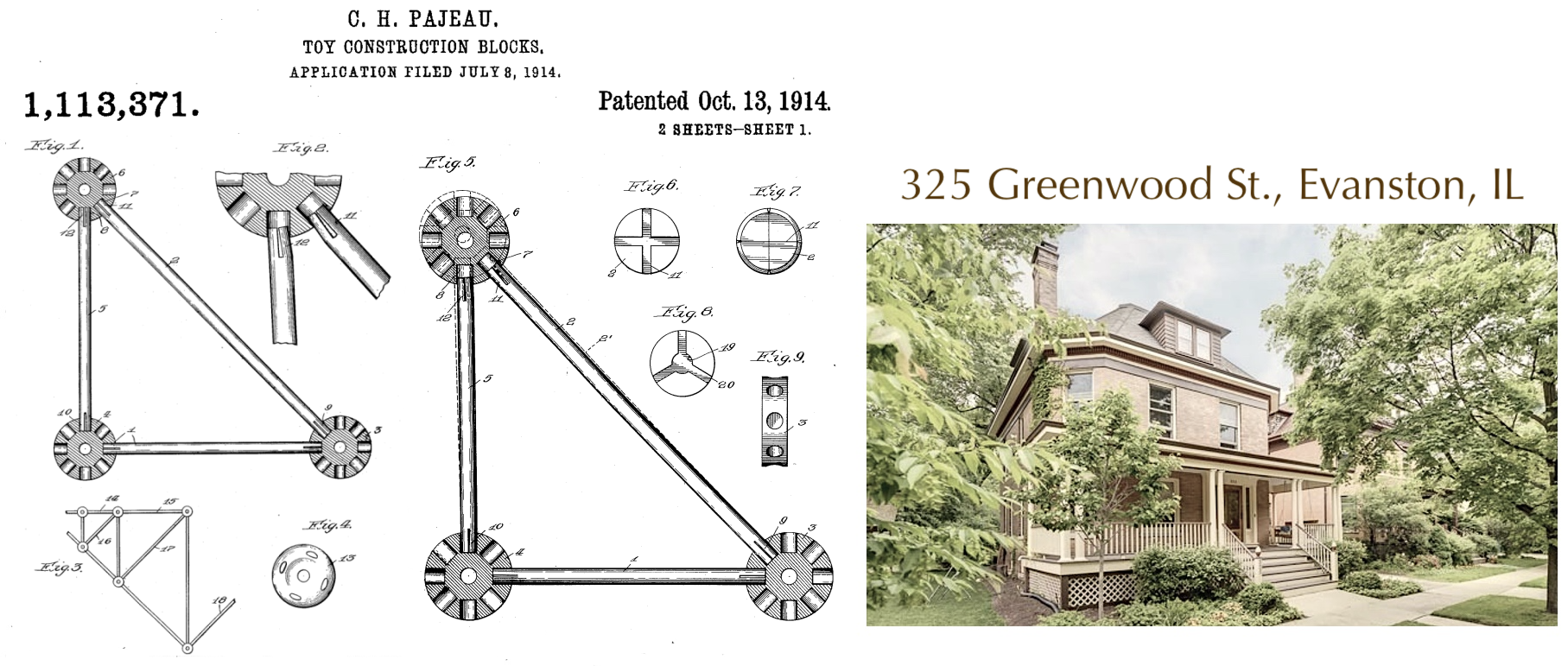

Eventually, his pal Pajeau gave him the direction he was looking for. On one of their train chats, Charles told Bob about a new toy idea he’d been developing inside his little home workshop at 325 Greenwood Street.

[The Evanston house where Pajeau invented the Tinkertoy, 325 Greenwood St., was built in 1898 and is still standing today]

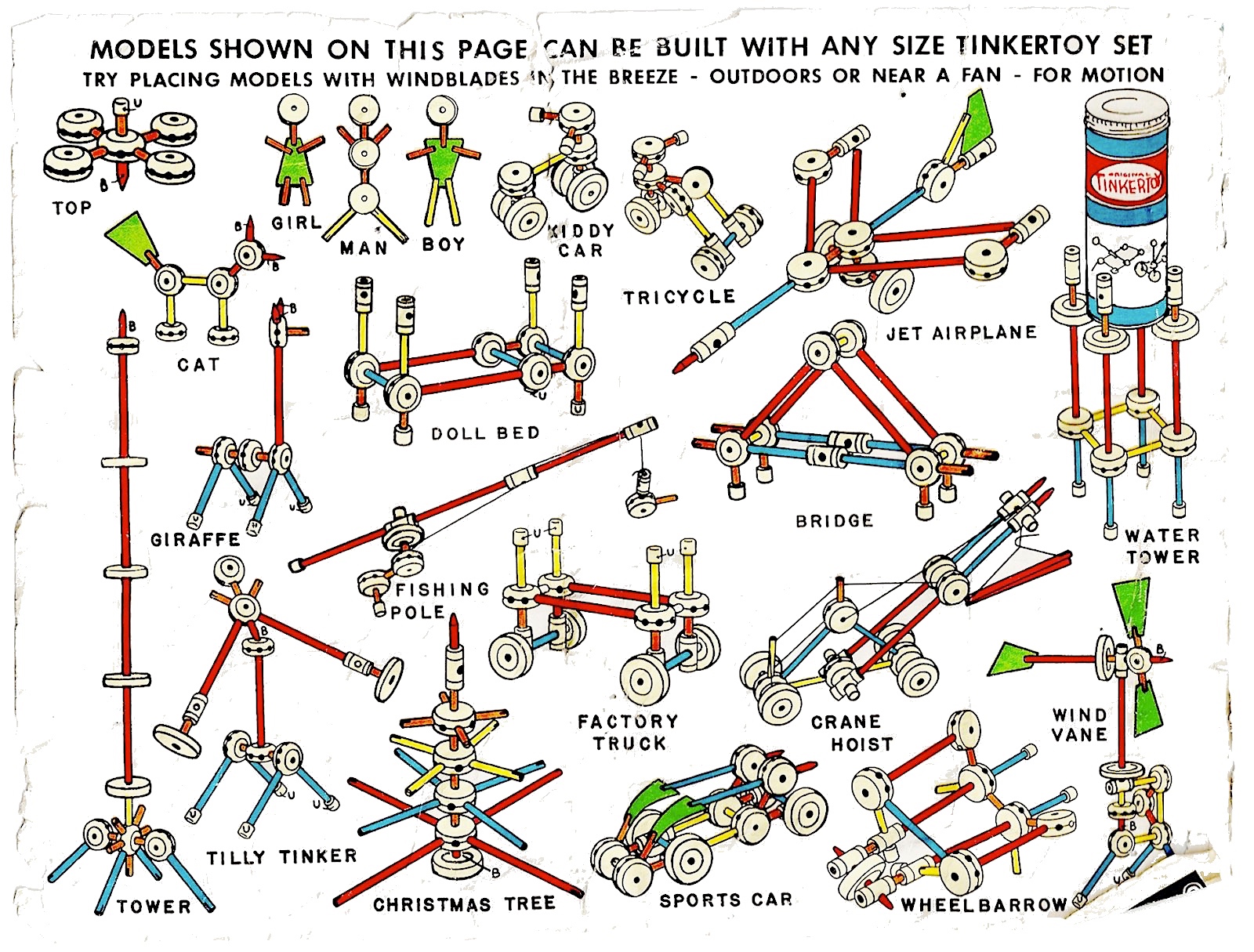

As System magazine later described it, Pajeau had “hit on a wooden construction toy which presented vast possibilities to the user; with a small wooden disk containing eight horizontal holes and one vertical center hole, and cylindrical sticks of various lengths to fit snugly into the holes, a youngster could build miniature bridges, windmills, ferris wheels, wagons, and a dozen other contrivances.”

This was, of course, the prototype for Tinkertoy. More important than the concept, though, Pajeau also had a firm grasp of the mathematics behind its eventual execution.

“It was here that old Pythagoras’s geometrical discovery [of the relations beside the sides of triangles] was put to work. For by utilizing the relationship of the line lengths shown in that principle, Pajeau arrived at the relative lengths for the sticks of his toy.”

Pajeau would later brag that his patented, Pythagorean sticks rendered all competitors’ designs inferior. “We had dozens of imitators as soon as our toy became a success,” he told System. “We could have spent all our profits in patent infringement litigation. But we smiled and let the infringers run along, and eventually they all discontinued the manufacture of wooden construction toys. Because of the relative length of our sticks, a child is always able to make what he is constructing meet at both ends. The infringers selected haphazard lengths for their sticks, and so about half the time the youngster could not complete a job. That speedily put the other manufacturers up against it.”

Pajeau would later brag that his patented, Pythagorean sticks rendered all competitors’ designs inferior. “We had dozens of imitators as soon as our toy became a success,” he told System. “We could have spent all our profits in patent infringement litigation. But we smiled and let the infringers run along, and eventually they all discontinued the manufacture of wooden construction toys. Because of the relative length of our sticks, a child is always able to make what he is constructing meet at both ends. The infringers selected haphazard lengths for their sticks, and so about half the time the youngster could not complete a job. That speedily put the other manufacturers up against it.”

Pajeau wasn’t exaggerating—there were loads of toy makers that either sprouted up or entered the construction toy business in the 1910s (including the American Mechanical Toy Co., N. N. Hill Brass Co., Structo MFG Co., Master-Builder, and the Engineero Co., among others). However, not all of them were piggybacking directly off of Tinkertoy. In fact, in the interest of historical context, it’s worth looking at the piggybacking done by Pajeau himself—most notably in following the lead of A. C. Gilbert’s Erector Set, which had debuted nationwide in 1913, a full year earlier. To take it even a step further, Gilbert’s idea for the Erector Set was almost certainly influenced by existing model construction kits like Meccano out of Great Britain, which dated back to 1901 (incidentally, Meccano eventually purchased the Erector Set brand a century later, in 2000, uniting the longtime cross-Atlantic rivals).

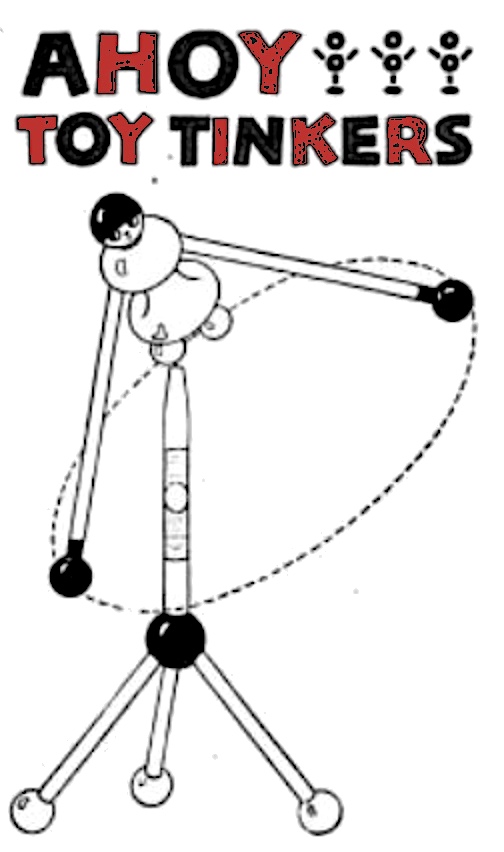

In any case, with a patent applied for, Charles Pajeau convinced Bob Pettit to invest in “the Tinker Toy,” and a new enterprise was formed by the end of 1914, cutely dubbed “The Toy Tinkers of Evanston in the State of Illinois.” As legend has it, they rented a small workshop at a cost of $17.50 per month, purchased the raw wood materials they needed, then hired one kid to help with assembly and packaging. The next step, they presumed, would be swiftly infiltrating the great toy sections of America’s leading department stores and mail order catalogs. But alas, with war in Europe complicating the marketplace, they found themselves rebuffed at every level. It might have ended there, if not for the fact that Pajeau and Pettit had already been through their share of scrapes as men of grain and granite. They weren’t going to be denied.

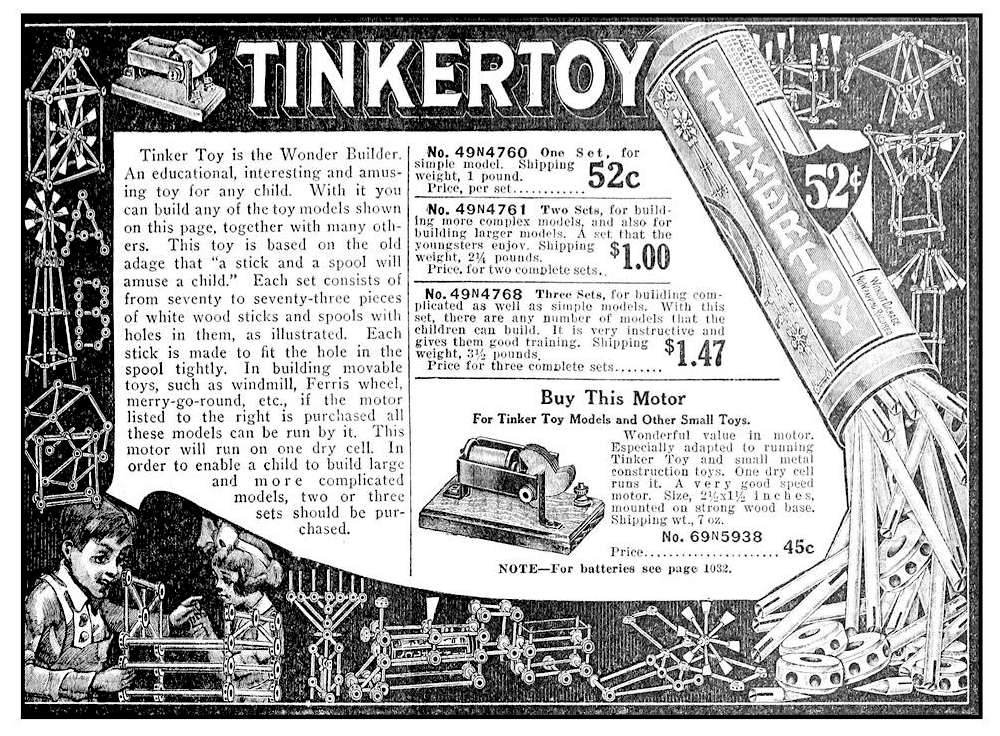

[Tinkertoy ad in 1918 Sears-Roebuck catalog]

III. A Way Into the Window

“Tinkertoy, the Wonder Builder, is designed for boys and girls from five to eighty-five! The set comprises 73 wooden spools and rods from which all kinds of moving and stationary figures can be easily constructed . . . each representing in toy form many of the large mechanical and architectural works of the present time. The Tinkertoy Wonder Builder is both entertaining and instructive.” – Tinkertoy ad, 1915

Tinkertoy’s big coming out party was the Christmas season of 1915, when they finally talked their way into a prominent window display at Marshall Field’s in downtown Chicago. For the year prior, though, Pajeau and Pettit had been forced to run a highly unorthodox campaign to get eyeballs on their product.

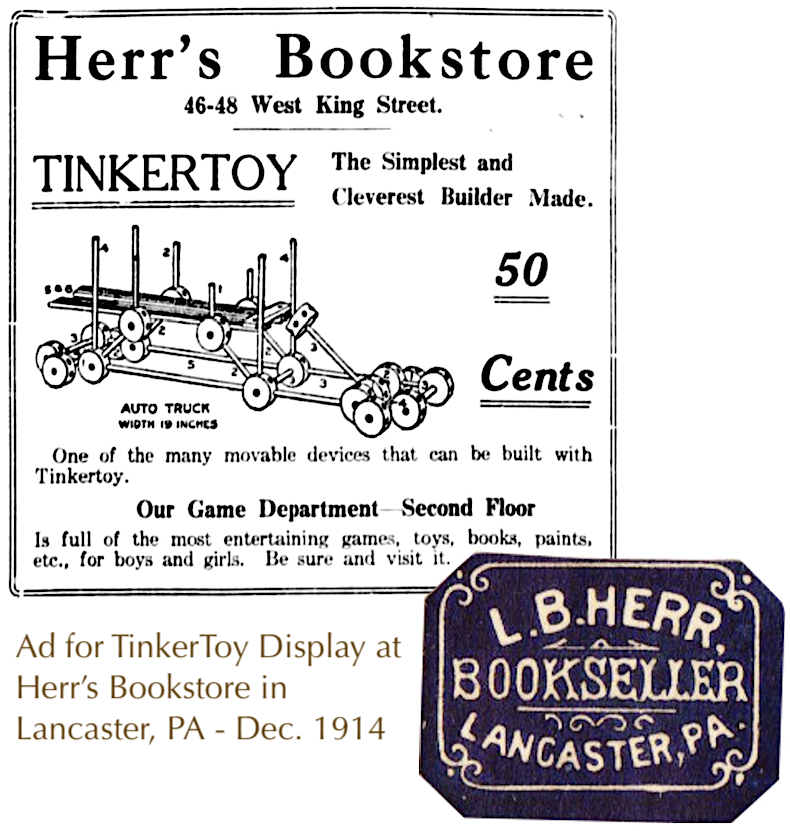

Unlike a teddy bear or a baby doll, their toy wasn’t self explanatory; it couldn’t sell itself just by sitting cute and motionless in its packaging. So, the Toy Tinkers looked for opportunities to display the possibilities of their construction kits in places outside the usual constraints of a toy department. This included “cigar stands, corner drug stores, stationery stores, and neighborhood dry goods stores,” according to an article in Printer’s Ink. In Lancaster, Pennsylvania, it was the second floor of Herr’s Bookstore. People who walked into these establishments without the slightest intention of buying a toy often came away with a new Christmas idea.

Similarly, when traditional industry schmoozing wasn’t working at the 1914 Toy Fair in New York City, Pajeau supposedly went a bit rogue and struck deals to display Tinkertoy contraptions at a shop in Grand Central Station and a couple nearby hotels, using electric fans to animate the various miniature windmills and ferris wheels. Once kids were stopping in their tracks in awe, the toy buyers at the fair finally took notice, too.

Even so, for their first holiday season in 1914, Pajeau and Pettit were still recruiting salesmen through newspaper ads, putting them in uniforms, and having them run pop-up Tinkertoy displays on street corners . . . preferably in the visual range of the nearest department store.

“If I never got anything else from the monument business,” Pajeau said, “I learned that it takes more than a good product to make a satisfied customer. As a result, we put out demonstrating crews which worked, one at a time, in every big city in the country. The crews built up a demand; and in not one instance did the direct sales fail to pay the crew’s expenses.”

[TinkerToy window display at the Mabley & Carew department store in Cincinnati, OH, 1915. Notice the tagline: “TinkerToy for Girl or Boy . . . 1,000 Toys in One”]

By the following Christmas, the campaign had finally graduated to Marshall Field’s, where Pajeau and Pettit again insisted on a performative element to the display, employing little people dressed as Santa’s elves to demonstrate Tinkertoy for window shoppers on State Street.

“The Tinkertoy is prominently featured for the coming holiday season,” wrote the Dry Goods Reporter in November of 1915. “Merry-go-rounds, swings, windmills, spinning tops, aeroplanes, automobiles, cranes, etc., are among the interesting things that may be made from the toy; the retail price of which is 50 cents. . . . State Street toy departments have sold hundreds of these toys from window demonstrations. They are interesting in their movements and bright colored flags, and seldom fail to attract the attention of passers-by.”

As another clever move right from the outset, Pajeau and Pettit opted to package each Tinkertoy set in a durable, laminated fiber mailing can, measuring 11-1/2” x 3” in diameter, and featuring bright blue and orange colors. The back of the can included space for a recipient’s mailing address and parcel postage, making it simple for department stores and mail-order houses, alike, to send out thousands of sets to eager kids across the country and eventually, around the world.

IV. “An Architectural Credit to Evanston”

“When a customer has been sold a Tinkertoy, we still have a good chance to sell him another, or several. For the more sets a youngster has, the more elaborate models he can build; by stressing that fact in their advertising, our dealers sell a lot of repeat orders.” —Lawrence D. Ely, General Sales Manager, Toy Tinkers of Evanston, 1922

If Robert Pettit was the business-school brains of the Tinkertoy operation, Lawrence Ely was its equally adept promotional guru. Forging uniquely friendly and trustworthy partnerships with both department stores and jobbers alike, he and his counterpart in the company’s New York office helped Tinkertoy become an enduring brand, even after its initial novelty waned. Clever advertising, of course, was also a big factor, as boys and girls, toddlers to teens, were always welcome into the fun, and parents were assured of the product’s safety and educational value.

If Robert Pettit was the business-school brains of the Tinkertoy operation, Lawrence Ely was its equally adept promotional guru. Forging uniquely friendly and trustworthy partnerships with both department stores and jobbers alike, he and his counterpart in the company’s New York office helped Tinkertoy become an enduring brand, even after its initial novelty waned. Clever advertising, of course, was also a big factor, as boys and girls, toddlers to teens, were always welcome into the fun, and parents were assured of the product’s safety and educational value.

“The Toy Tinkers of Evanston like to think that in making the Tinker family of Toydom, they have made happiness for many a little solemn head and for many an older one, too,” read a 1917 ad in the Saturday Evening Post. “[We] believe that toys can build character, just as can books.”

Charles Pajeau was deeply involved in this first big national ad campaign, and even wrote a series of mini poems that appeared in them.

“Toy Tinkers, Toy Tinkers, make us a toy

Chock-full of quaintness ’n stuff-full of joy

Little folks, listen! That’s just what we do

And we plan it and shape it and make it for you.”

The magazine ads, packaging, and window displays—along with the quality of the toys themselves—put the Toy Tinkers of Evanston firmly in the public’s good graces. Between 1915 and 1920, the company moved over 6 million units. And while the raw sticks and spools were all purchased from an outside supplier, production demands were dramatically escalating all the same.

As such, a move was necessitated to a much larger Evanston factory space—located at 721 Custer Avenue—where a team of mostly high-school aged boys were paid $10-12 dollars per week for light manufacturing work, while girls, paid far less, handled much of the packaging (female employees did at least get their own private lunch room with a stove and coffee machine . . . progressive perks for the era).

There were some important grown-up employees on the team, too, including a Swedish-born engineer named Henry Martin Svebilius, who designed a pair of specialized machines that became integral to the Tinkertoy manufacturing process: one to cut slits in the ends of the rods, and another to bore holes in each spool.

There were some important grown-up employees on the team, too, including a Swedish-born engineer named Henry Martin Svebilius, who designed a pair of specialized machines that became integral to the Tinkertoy manufacturing process: one to cut slits in the ends of the rods, and another to bore holes in each spool.

Not everything was automated, though. As described in the 1925 book Business Organization and Management, the factory of the Toy Tinkers of Evanston represented an “interesting illustration of the results of operation analysis.” Robert Pettit had created a very streamlined assembly line in which even the final, presumably simplest step—putting the toys in the mailing tube—involved several levels of human oversight.

“The Inspector, who rapidly inspects the hubs as they move past him in a special glass fixture and loads them by an automatic counter into the carton

“The Supply Boy, who from time to time as needed, brings empty cartons from a nearby reserve supply and places them in front of the inspector. He also brings bundles of the wooden rods to the operator.

“The Sorters, each of whom picks up the required number of a particular size of rod and places them in the carton, which is passed from hand to hand from the inspector to the final packer.”

“The Sorters, each of whom picks up the required number of a particular size of rod and places them in the carton, which is passed from hand to hand from the inspector to the final packer.”

“The Packer, who puts in the directions, screws on the cover and places the carton in a packing box. The boxes are placed on a conveyor, sealed, and conveyed down to the storage room.”

Above all this bustle, company president Charles Pajeau wasn’t the traditional factory boss looking down on his workers with stern judgment. Sure, he maintained an executive office with a standard-issue mahogany desk, but he spent more of his time in a second, less shiny “working office” inside the factory building, where he enthusiastically continued to develop new products for the Tinkertoy line.

“When I want to get off by myself to do some creative thinking, here’s where I come,” Pajeau told System magazine. “I am seldom disturbed in this room. I can work, and experiment, and tinker away like a true Toy Tinker. Already we are waiting for the chance to manufacture and market about 20 other toys that have been designed here. Maybe they won’t sell at all; maybe they’ll beat Tinker Toy.”

A century later, we can easily say that none of Pajeau’s Tinkertoy offshoots ever rivaled the original, but no one can accuse the man of resting on his laurels. Between 1915 and 1940, he put several dozen more of his imaginings into production, including Tinker Blox, Tinker Pins, Bunny Tinker, Tom Tinker, Belle Tinker, Puppy Tinker, Baby Doll Tinker, and the oddest of them all, a dancing, sideshow performance doll called “Miss TillyTinker, The Terpsichorean Queen.”

[Above: Charles Pajeau in his workshop, where he hatched ideas for numerous products, including Tom and Belle Tinker, TinkerBlox, and Tilly Tinker the Terpsichorean Queen. Below: Promotional photos of a boy and girl building a plane with the “Giant Ticker” kit, 1920s.]

Fortunately, Pajeau’s boundless creative ambition was balanced out by his sales department’s wise preference for load management.

“Though we do not set any exact limit to the number [of products] we believe we can profitably make, 21 is just about the limit,” Pajeau admitted in 1925. “We know toy manufacturers who make 400 or more different items. Many of their products are only so much baggage. The diversity of their products only serves to confuse the buyers, the public, and themselves. They cannot specialize or concentrate on any particular group of toys. They have not multiplied the volume of their business by their additional numbers, but they have multiplied their troubles.”

By the late 1920s, the Toy Tinkers had migrated again to a new, 65,000 square foot Evanston factory at 2012 Ridge Avenue, which Bob Pettit described at the time as “not only the latest word in factory construction, suitable to our needs, but which will be an architectural credit to Evanston.”

[2012 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, 1928 vs. today]

The building was laid out as such:

First Floor: Executive offices, loading dock, paint room, and storage.

Second Floor: Assembly rooms, lunch room, and canister assembly room, aka “The Bench.”

Third Floor: More assembly and packing rooms.

Fourth Floor: Machine shop, drill machine operators, and stick machine operators.

Tower Portion: Conference room and Charles Pajeau’s workshop.

Rooftop: Recreation area with tennis, basketball and volleyball courts.

About 100 employees seemed to have a pretty nice future ahead of them, working for a fast-growing toy company and a good-humored boss in a swell new building. But even Pajeau himself was in for a rough wake up call as the Roaring ‘20s bottomed out.

[Charles Pajeau, in the bow tie, attending a toy industry convention in 1917]

V. Survival and Adaptation

Unlike a lot of toy companies, Toy Tinkers, Inc. didn’t sink during the Great Depression (making exclusively wooden toys certainly helped), but it was posed with plenty of challenges. For one thing, it was widely rumored that the company president, C. H. Pajeau, had lost a good deal of his fortune in failed investments. He and his wife were forced to leave their new Glencoe mansion and return to a small home in Evanston in the early ‘30s. Similarly, with consumer demand in decline, the mighty new Tinkertoy factory itself soon became too expensive to maintain. Many workers were laid off, and the plant was rented out to a cosmetics firm, Lady Esther, in 1933, as the Toy Tinkers retreated to a building down the street, one-half the size, at 1948 Ridge Avenue.

In an otherwise dark period for the business, though, there were flecks of color. In a literal sense, new Tinkertoy kits were introduced with striking paint jobs; red spools—as seen in our museum artifact—debuted in 1932, and colored sticks came along a few years later. Electric and spring motors were also popular new additions to the catalog, making it far easier to build moving components.

In an otherwise dark period for the business, though, there were flecks of color. In a literal sense, new Tinkertoy kits were introduced with striking paint jobs; red spools—as seen in our museum artifact—debuted in 1932, and colored sticks came along a few years later. Electric and spring motors were also popular new additions to the catalog, making it far easier to build moving components.

The days of Charles Pajeau churning out 12 new Tinker characters every year were reaching an end, however. After he was injured in a plane crash in 1938, the 63 year-old tinkerer-in-chief came out of his recovery with a revised assessment of the company’s future. Toy Tinkers would now focus solely on making its construction kits. As much as he’d happily spent his life at the drawing board, the time had come to be practical and simply give the people what they wanted.

According to Craig Strange’s Collector’s Guide to Tinker Toys, “As the Second World War approached, the demand for Tinkertoy construction sets continued to grow, while the labor pool began to shrink. By 1941, high school students from Evanston were working the night shift at the Toy Tinkers factory. There would typically be about fifteen people working this 3pm to 11pm shift . . . earning about 38 to 45 cents an hour.

“The schedule was rough on the high school students,” Strange writes, “yet, with Toy Tinkers being such a part of their lives, they managed to have fun on the job.” Strange notes one story recounted by a former teen employee named Paul Gardner, who—when suffering from a bad sunburn one day—was running the drill press without a shirt on. “One of the girls came up behind him and poured a bucket of sawdust on him. He was laughing when he told the story, so it appears it was all in fun.”

The plant continued to operate during the war, as toys remained important to homefront morale, but metal rationing spelled the demise of the electric and spring motor sets, and a switch from metal to cardboard container lids. More importantly, 1943 also marked the death of company co-founder Robert Pettit at the age of 62. Longtime employee Albert Liescke was elevated to the role of vice president, but with no clear heir in place under Charles Pajeau, Tinkertoy’s post-war future was left in some degree of doubt.

[Left: Fred Hiertz, who joined the Toy Tinkers in 1924, was factory superintendent for many years, and is seen here helping a woman at the stick machine in 1964. Right: Charles Pajeau photographed at the Sheridan Shore Yacht Club in the 1940s.]

VI. “Only the Teddy Bear Can Beat Us!”

“Forty-five million feet of wood—enough to construct 4,867 bridges the length of San Francisco’s Golden Gate span. . . . That vast amount is the quantity used each year to manufacture one of America’s most popular toys—the Tinkertoy.” — The Dispatch, 1972

Shortly after the war ended, Toy Tinkers, Inc. moved to what would be its final Evanston headquarters, at 807 Greenwood Street. By 1952, Albert Liescke was running the day-to-day operations, but Charles Pajeau was still devoted to the business and contributing to new promotions and the content of its instruction booklets. Even though the “Wonder Builder” sets hadn’t evolved that much from their simple origins, the types of objects that kids built from them continued to reflect the times, as bi-planes gave way to jets and space rockets.

Shortly after the war ended, Toy Tinkers, Inc. moved to what would be its final Evanston headquarters, at 807 Greenwood Street. By 1952, Albert Liescke was running the day-to-day operations, but Charles Pajeau was still devoted to the business and contributing to new promotions and the content of its instruction booklets. Even though the “Wonder Builder” sets hadn’t evolved that much from their simple origins, the types of objects that kids built from them continued to reflect the times, as bi-planes gave way to jets and space rockets.

Believing Tinkertoy could remain timeless in its appeal, Pajeau looked for a way to ensure the long term future of the business—specifically, he wanted a financial partner that would understand the principles of the company and carry on his vision. This included (a) loyalty to Evanston and the history of the business, (b) dedication to creating a safe product for anyone over the age of 3, and (c) never promoting the building of guns or weapons in Tinkertoy kits.

In 1952, a deal was struck with A. G. Spalding & Bros., Inc., a major sports equipment company with Chicagoland roots of its own. Some of the executives on the Spalding board were former Evanston lads themselves, and after earning Pajeau’s trust over a couple rounds of golf, they agreed to buy out the majority ownership from Pajeau, his wife Grace, and Bob Pettit’s family.

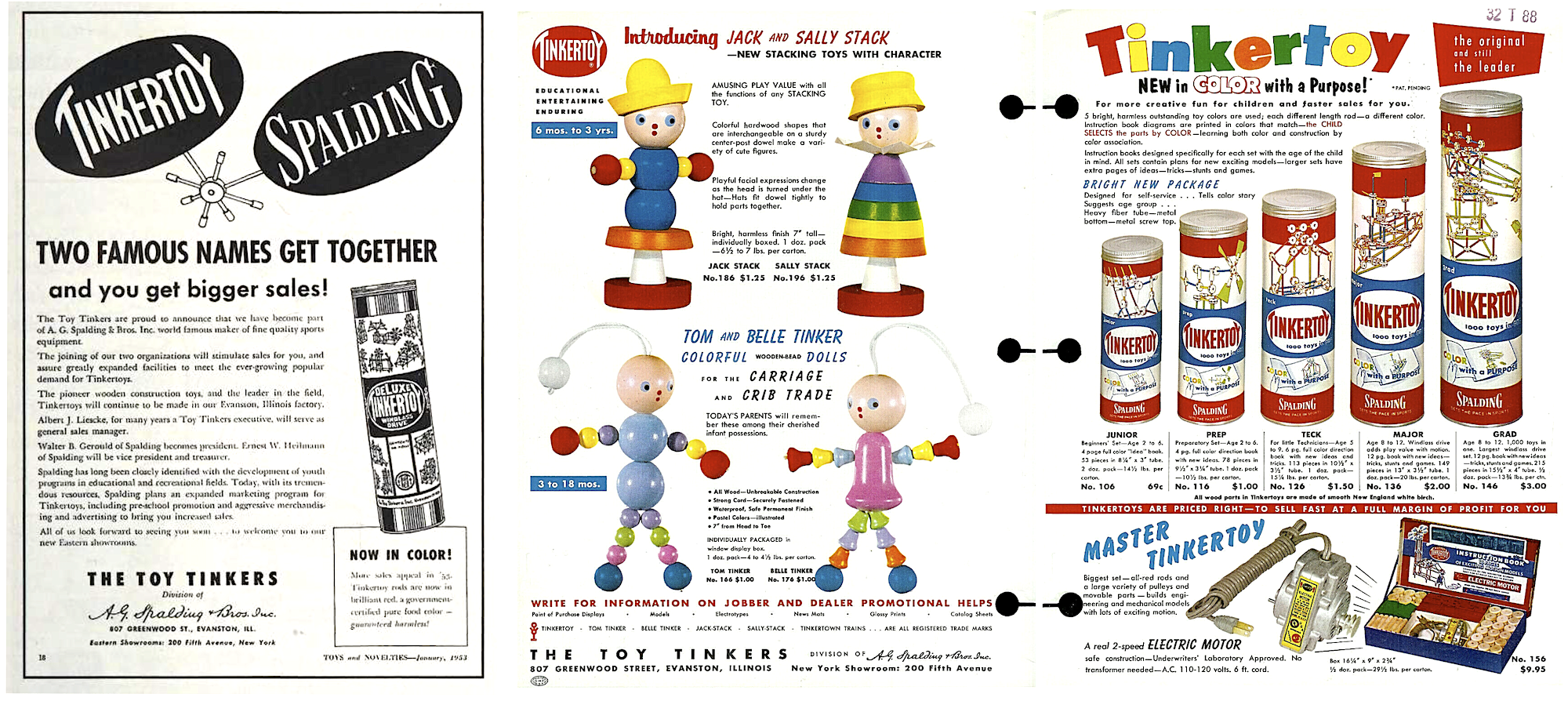

“Two Famous Names Get Together!” touted an advertisement in a trade publication. “The Toy Tinkers are proud to announce that we have become part of A. G. Spalding & Bros., Inc. . . . The joining of our two organizations will assure greatly expanded facilities to meet the ever growing popular demand for Tinkertoys.”

In the deal, Spalding agreed to keep production of Tinkertoys in Evanston, with longtime plant manager Fred Hiertz still on the job. Albert Liescke was also retained as general sales manager, while Spalding execs Walter B. Gerould and Ernest W. Heilmann would become president and VP, respectively. Pajeau was to remain on board as an advisor . . . but he never had the opportunity.

On December 17, 1952, just weeks after selling the business and hours after updating his will, Charles Hamilton Pajeau died of a heart attack, in his sleep, at his penthouse apartment in Evanston’s Orrington Hotel. Always a generous chap during the holiday season, he’d sent out Christmas cards to friends and employees a few days earlier, providing a warm—if unintended—farewell to his many admirers. Despite spending the first half of his life in the mausoleum business, he also ironically—or tellingly—opted for cremation.

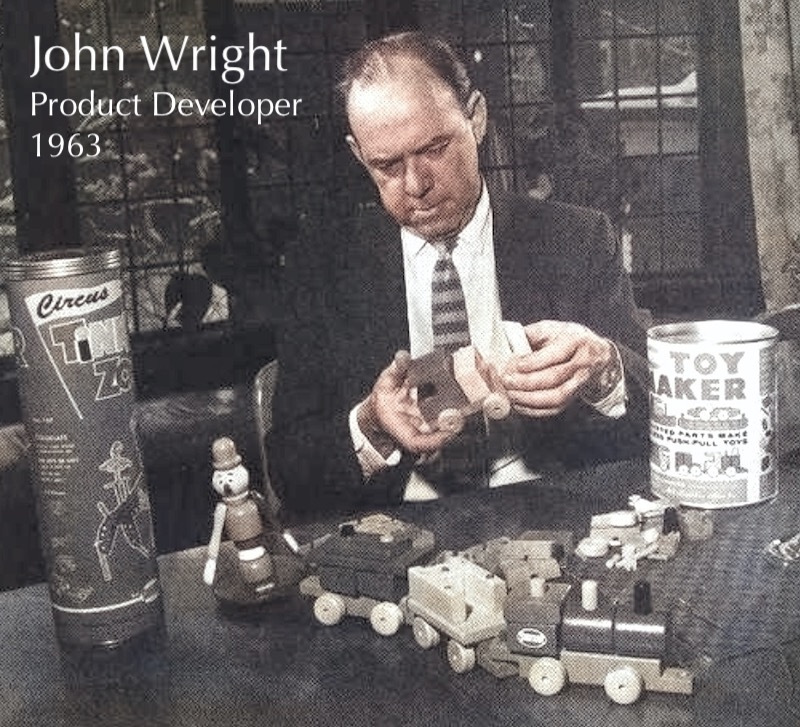

In the years that followed, Spalding kept up their end of the bargain while also putting their market analysts on the case, seeking out new opportunities. John Wright (no relation to Lincoln Logs creator John Lloyd Wright) was the new lead product developer, having been vouched for by Pajeau himself. Under Wright’s leadership, Spalding’s Tinkertoy relaunched some of the company’s old discontinued products (including Tom Tinker and Belle Tinker), revved up an expanded line of motor-operated kits, and introduced new ideas such as Tinker Zoo and Tinkertown Trains. Wright also suggested that Spalding consider striking a deal with an upstart Danish firm that was trying to bring its plastic stacking bricks to the U.S. market. The Spalding execs refused, missing the boat on LEGO.

In the years that followed, Spalding kept up their end of the bargain while also putting their market analysts on the case, seeking out new opportunities. John Wright (no relation to Lincoln Logs creator John Lloyd Wright) was the new lead product developer, having been vouched for by Pajeau himself. Under Wright’s leadership, Spalding’s Tinkertoy relaunched some of the company’s old discontinued products (including Tom Tinker and Belle Tinker), revved up an expanded line of motor-operated kits, and introduced new ideas such as Tinker Zoo and Tinkertown Trains. Wright also suggested that Spalding consider striking a deal with an upstart Danish firm that was trying to bring its plastic stacking bricks to the U.S. market. The Spalding execs refused, missing the boat on LEGO.

Nonetheless, when Tinkertoy marked its 50th anniversary in 1964, the company was still thriving; producing an estimated 2 million units of its flagship line that year, marking a grand total of 55 million units over the history of the business.

“We consider 50 years a remarkable record for longevity,” VP Heilmann said at the time. “Only the teddy bear can beat us.”

Charles Pajeau’s dream seemed to be intact, but in the world of big corporate mergers and American factory closures, the clock was actually ticking.

[807 Greenwood St., Evanston: Home to the Toy Tinkers from the late 1940s to 1973]

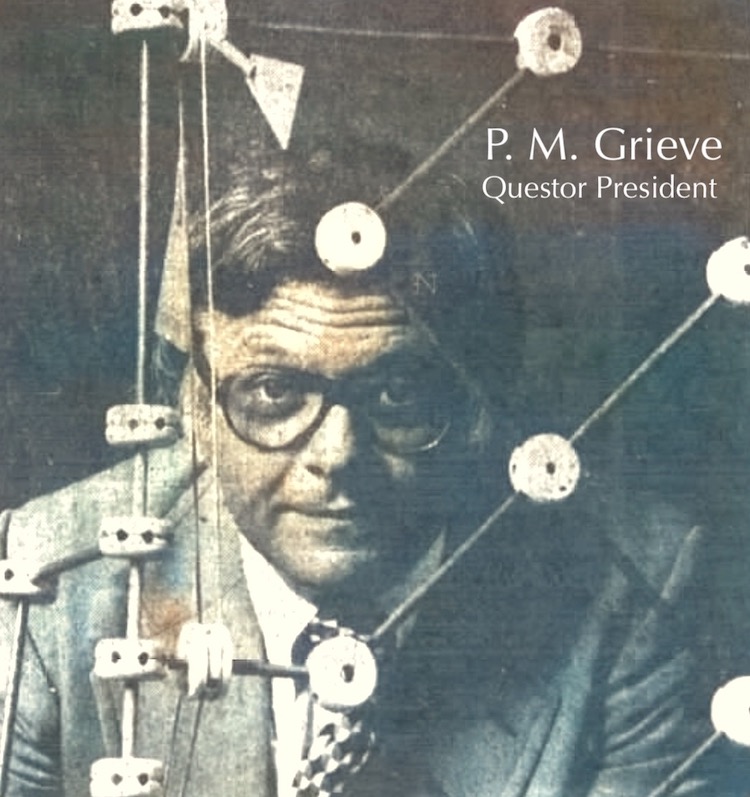

After Spalding fell under the ownership of Ohio’s Questor Corporation in the early 1970s, a new attitude moved through the organization at every level. Questor president Pierson M. Grieve, described by the Tribune as a “vigorous, square-jawed man who talks with appalling candor,” began making immediate changes, including the rebranding of the “The Toy Tinkers of Evanston” to “Tinkertoy Division of Questor Education Products Company.” Grieve, a Northwestern grad, kept alive some of Pajeau’s principles, including high safety standards, but his motivations may have been a tad different.

“You can imagine the amount of safety engineering we have to put in these things so the little shits won’t hurt themselves,” he told the Tribune. “You kill one kid and that’s it. Aside from the moral concern, financially, you’re ruined.”

“You can imagine the amount of safety engineering we have to put in these things so the little shits won’t hurt themselves,” he told the Tribune. “You kill one kid and that’s it. Aside from the moral concern, financially, you’re ruined.”

Questor’s focus on the bottom line was evident in their decision to abruptly shut down the Tinkertoy factory in 1973, consolidating all production in one of the conglomerate’s other plants in Brooklyn, NY. Overnight, Tinkertoy’s 60-year relationship with Evanston was over.

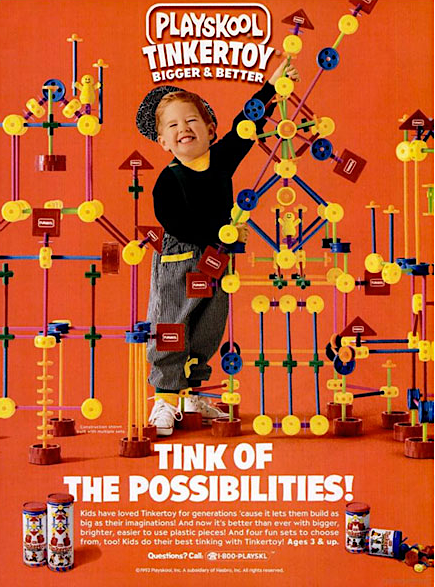

That’s not the end of the Tinkertoy story, of course. The toy line has remained popular to this day, even as it has passed hands from Questor to Gabriel Industries, then Hasbro/Playskool, and most recently, Basic Fun. Many of the sets are now constructed from plastic, but in terms of function and purpose, they still uphold Charles Pajeau’s original, simple observation: “a stick and a spool will amuse a child.”

[1992 ad]

Sources:

“Structural Toy Building Contest” – Dry Goods Reporter, May 1915

“Charles H. Pajeau” – System, The Magazine of Business, Vol. 34, 1918

“Whimsical Campaign of Toy Tinkers for Institutional Prestige” – Printer’s Ink, Feb 21, 1918

“How Tinker Toys Were Put Across” – Business Digest and Investment Weekly, Jan 28, 1919

“Chicago as a Maker of Christmas Toys” – Fort Dearborn Magazine, Dec 1920

“How We Build More Sales for Jobbers’ Salesmen,” by Lawrence D. Ely in Printer’s Ink Monthly, April 1922

“Modern Production Methods” – The Wood-Worker, January 1925

“Operation Analysis: Routing” – Business Organization and Management, by Henry P. Dutton, 1925

“Charles H. Pajeau” (Obit) – Chicago Tribune, Dec 19, 1952

“Generations of Boys Build Tinkertoy Fame” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 16, 1964

“45 Million Feet of Wood . . . For Tinkertoys” – The Dispatch (Moline, IL), Dec 14, 1972

“Toy Maker’s Chief Doesn’t Play Games” – Chicago Tribune, June 10, 1973

“Exhibit Puts Together Pieces of Tinkertoy’s Past” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 12, 1983

“A Short History of a Classic: Tinkertoys” – Morning Call (Allentown, PA) , Nov 4, 1990

Collectors’s Guide to Tinker Toys, by Craig Strange, 1996

“Tinkertoys: A Toy for the Ages, Born and Raised in Evanston” – PlaygroundProfessionals.com

“The Bizarre Christmas Marketing Stunt That Made Tinker Toys A Hit” – HistoryDaily.org

Hello

I am from Pittsburgh pa. Now living in nicasio California.

At a garage sale I purchased a tube of tinker toys. It says BIG BOY at the top of the can and is labeled #155. Its label says “the toy tinkers , division of Spaulding brothers inc, Evanston Illinois. Why does it say BIG BOY. Any value?

I have a toy marked nov 13, 1928. It doesn’t look like a tinker toy. Wood balls with metal that would loom like a measuring spoon , with a cup like piece on tje vottom. Amy ideas what it is?

Tinker Toys are my favorite. I have over 100 sets. I am 77 years old and have fun building with my grandchildren.

I have a cannister which is identical to the one on your website, little boy with hands in pocket and tinkertoy written on both sides of his trousers. Are there any markings on cannister to tell when it was made? I find nothing on the can itself.

I have several pieces as well as a fairly well deteriorated illustrated instruction manual of TinkerToys. What is unusual (to me at least) is that the “spars” are approximately 1/2″ SQUARE in section and the “hubs” are sheet metal disks with 1/2 moon shaped tabs that into slots cut in the ends of the spars.

I would love any and information as I have been unable to locate any whatsoever.

I have a set of tinker toys with the original container. It appears to be a replica of the set in the photo of the museum artifact. Is it worth keeping or ?

Hope you’ll check with us at the Evanston History Center, we have a lot of documentation of Tinker Toys.

We at Design Evanston have published two books about our architectural and design history that include references to TinkerToy.

“Evanston: 150 Years 150 Places” featured the architecture. “Evanston’s Design Heritage” soon to be released, features the designer, Charles Pajeau.

Happy to send pdfs of both via email.