Museum Artifact: General Motors “Erie Limited” Locomotive Data Card (Electro-Motive Div.), 1950s

Made By: Toby Rubovits, Inc., 127 S. Aberdeen St., Chicago, IL [West Loop]

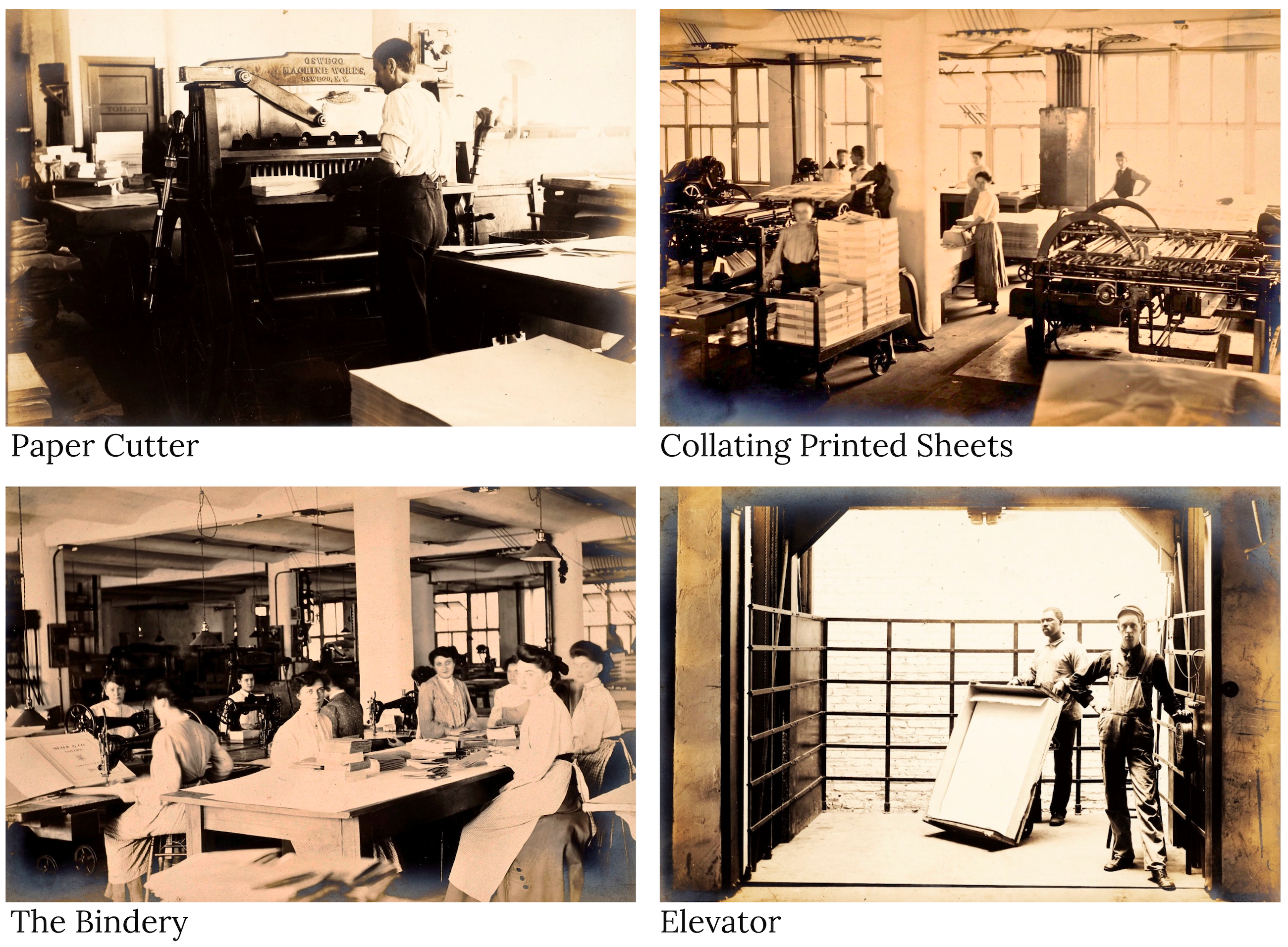

On New Year’s Day, 1912, Toby Rubovits took out a large advertisement in the Chicago Tribune, promoting his services as “Printing without frills.” He was, unlike many of his competitors, offering three professional skills in one office. Rubovits was a “Designer – capable of creating matter that is distinctive and appropriate to intended purpose; a Printer – with the ability to combine type, ink and paper with considerable thought; and a Binder – with unusual facilities and exclusive machinery for producing superior work.”

Rubovits was already 54 years old by this point, and had been involved in the printing industry since his teenage days, way back around the time of the Great Chicago Fire. He didn’t tend to emphasize that fact in his advertisements, though, as “experience” could sometimes be perceived as a handicap in a world in which printing methods and technology were constantly advancing. Fortunately, to the benefit of his company and his clients, Toby Rubovits was not a stubborn traditionalist, and his company’s embrace of new processes kept it a relevant force for more than 60 years.

Rubovits was already 54 years old by this point, and had been involved in the printing industry since his teenage days, way back around the time of the Great Chicago Fire. He didn’t tend to emphasize that fact in his advertisements, though, as “experience” could sometimes be perceived as a handicap in a world in which printing methods and technology were constantly advancing. Fortunately, to the benefit of his company and his clients, Toby Rubovits was not a stubborn traditionalist, and his company’s embrace of new processes kept it a relevant force for more than 60 years.

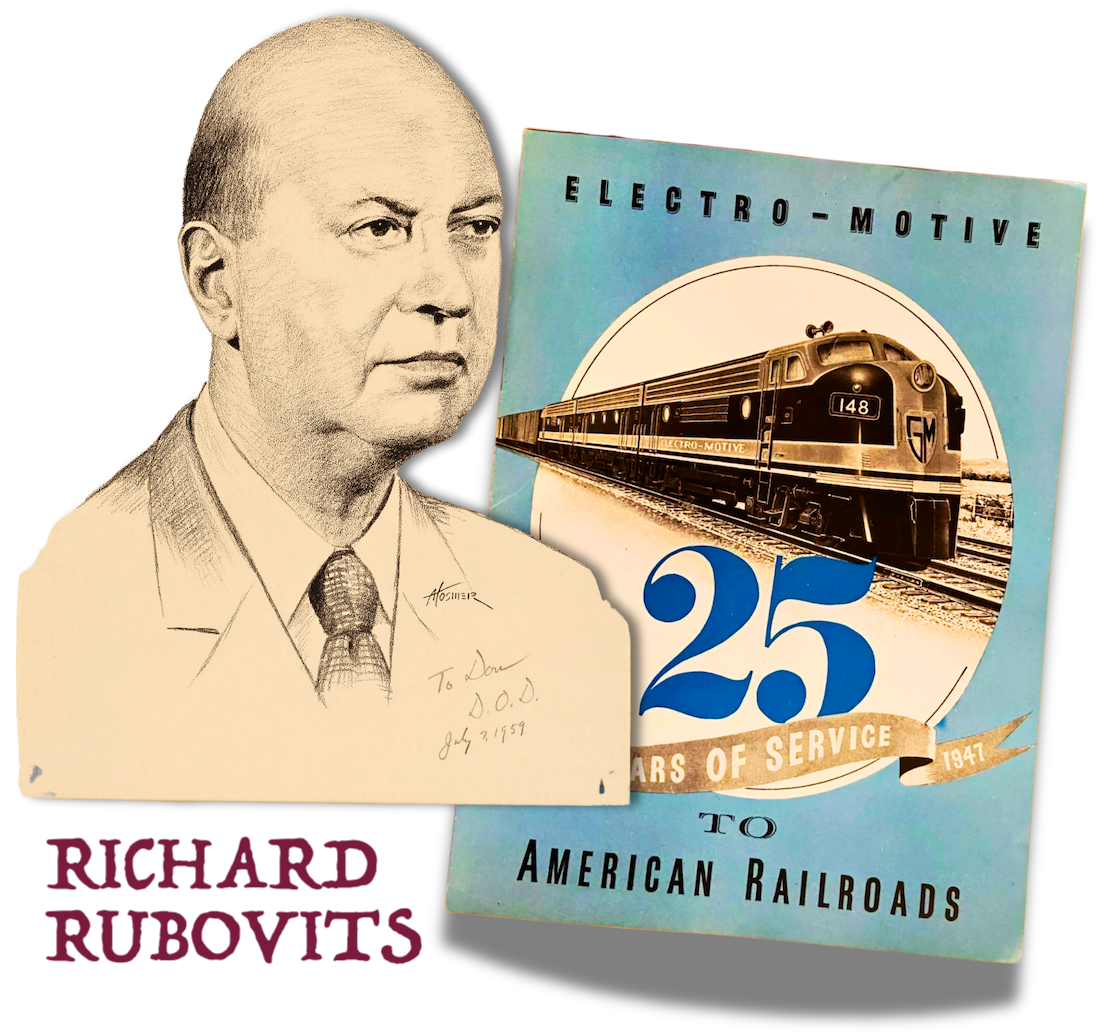

To tell the story of Toby Rubovits, Inc., the Made In Chicago Museum has welcomed the research and insights of Toby’s own grandson, Donald Finn Rubovits of Evanston, Illinois. Donald pieced together much of the history of his family’s company, which also included his father Richard Rubovits. Many of the photos included in this piece also come direct from the Rubovits family collection.

[Workers using hand-operated platen presses at the Toby Rubovits printing plant at what is now 517 S. Wells Street, 1910s]

History of Toby Rubovits Inc., Part I: Immigrant’s Ink

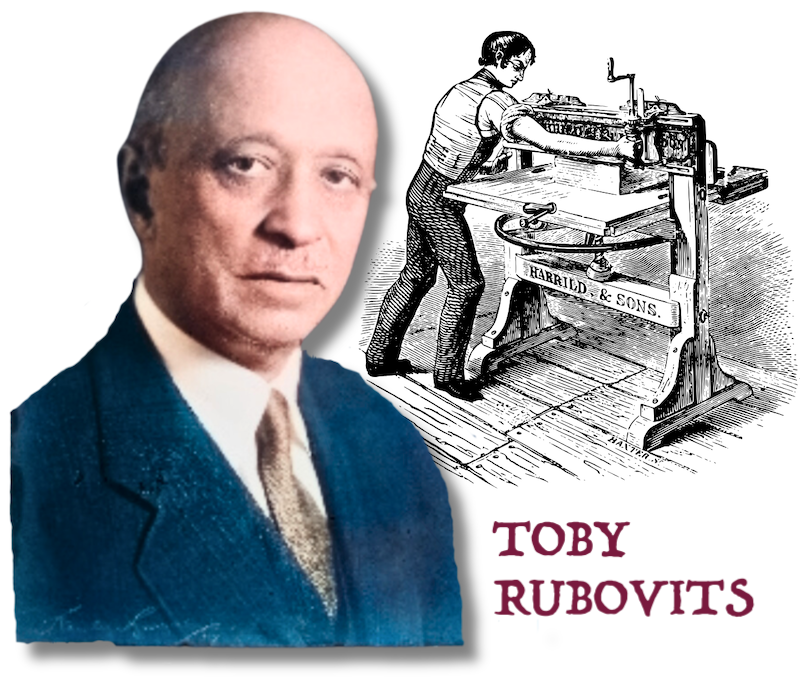

Tobias “Toby” Rubovits was born in 1857 in Eperjes, Hungary, which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Eperjes was later renamed Presov when the region was designated as part of Slovakia after World War I). His father was a miller and the family were German-speakers of the Jewish faith. Toby was the baby of the family, joining five older siblings.

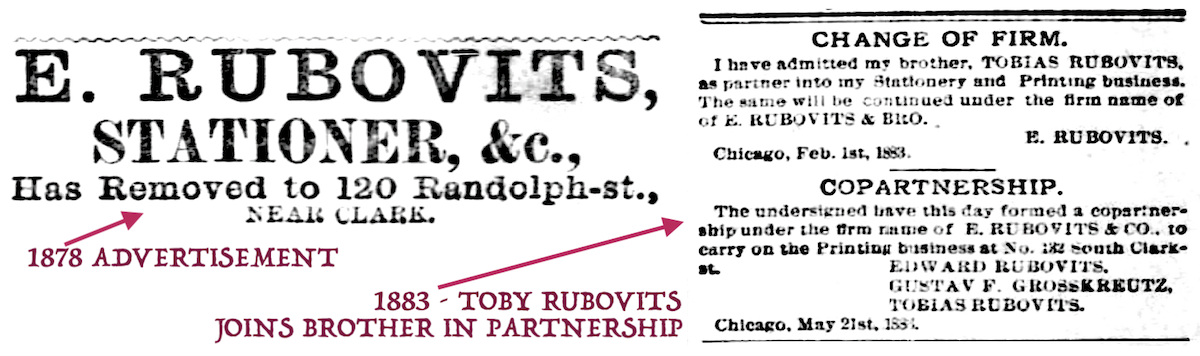

One of his much older brothers, Edward, immigrated to America in 1866, eventually arriving in Chicago and opening a book store in the vicinity of Randolph and Wells Street. A few years later, at the age of just 13, Toby decided to make the same journey, all by his lonesome no less; crossing the Carpathian Mountains in an oxcart, taking a ship across the Atlantic, and finally setting foot in Chicago in June of 1871. Edward Rubovits and his wife took young Toby in and gave him work delivering newspapers and handling new stock in the bookshop. A few months into this exciting new life, however, the Great Chicago Fire turned a bustling young city into a pile of rubble and left many of its new arrivals scrambling for a means of income.

One of his much older brothers, Edward, immigrated to America in 1866, eventually arriving in Chicago and opening a book store in the vicinity of Randolph and Wells Street. A few years later, at the age of just 13, Toby decided to make the same journey, all by his lonesome no less; crossing the Carpathian Mountains in an oxcart, taking a ship across the Atlantic, and finally setting foot in Chicago in June of 1871. Edward Rubovits and his wife took young Toby in and gave him work delivering newspapers and handling new stock in the bookshop. A few months into this exciting new life, however, the Great Chicago Fire turned a bustling young city into a pile of rubble and left many of its new arrivals scrambling for a means of income.

In the aftermath, Edward Rubovits was fortunate enough to stay in business, but he decided to add stationery and printing to his services, in hopes of making his enterprise a little more disaster proof. As a result, his kid brother Toby learned the printing trade from a very young age.

In 1877, at the age of 20, Toby expanded his education by working in the book bindery of Kiss and Ringer – later Ernest Hertzberg & Sons, and today, Monastery Hill Bindery. He then re-teamed with Edward as an official partner in his business, which was renamed E. Rubovits and Brother. Together, their shop on Randolph Street became something more than a commercial printer and binder; it was an important meeting spot that literally helped bind together much of Chicago’s intellectual Jewish community. As explained in the 1933 book Chicago and Its Jews: A Cultural History, “There were no Jewish clubhouses downtown in those days, and so the stationery store and printing establishment of Edward Rubovits and his brother Toby, at 120 East Randolph street, became the place where all restless souls congregated.”

During this same period, according to the Inland Printer magazine, “Toby Rubovits began to show a special knack for selling sample books to tailors. He developed special equipment and methods for economical production of sample books, and built up a large business on this single item.”

Business was good, but there were also more mouths to feed. Toby had married the delightfully named Hannah Goodkind in 1890, and the pair had three children, Arthur, Walter, and Richard. By 1892, at the age of 35, Toby was looking for other avenues of revenue to help his family out in a rough economy. In anticipation of the approaching Columbian Exposition, he and Edward launched a new side business, called the Columbus Memorial Company, with the following stated purpose: “to collect autographs, publish memorials and literature concerning the discovery of America by Columbus and the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago, Ill.” It was a nice enough side hustle, but Toby’s growing ambition needed a long term target.

And so, before 1893 was over, Toby Rubovits embraced the World’s Fair spirit and set out on a printing and binding venture of his own, with an office at 180 Monroe Street (Edward continued on with his original enterprise as E. Rubovits & Son, adding his son Frank in Toby’s abandoned spot).

It’s not clear if Toby and Edward had experienced creative differences or if Toby simply wanted to spread his wings. Either way, the kid brother soon proved himself well suited to the role of top dog. He assembled better typefaces, installed larger presses, and developed a capable staff as the new century rolled in. Rubovits was also an increasingly recognized figure in the larger world of the Chicago printing industry. In 1904, at a dinner held by the Chicago Typothetae association of printers, Toby gave a speech entitled “The Dignity of the Printing Business.” We don’t have the transcript, but one can safely presume that the man was passionate about his line of work.

[The original Toby Rubovits printing offices at 180 Monroe, c.1890s]

II. View from the Top

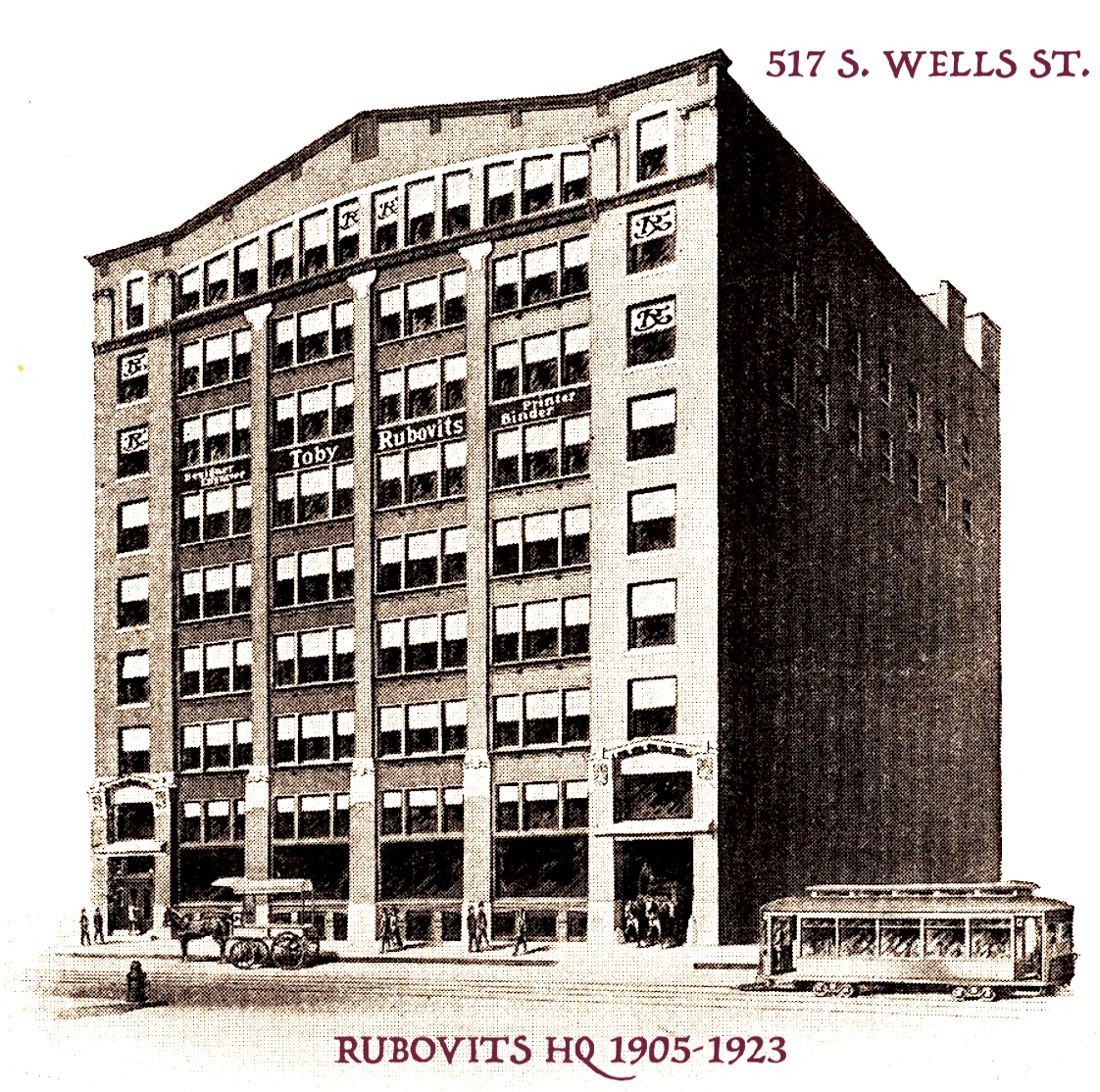

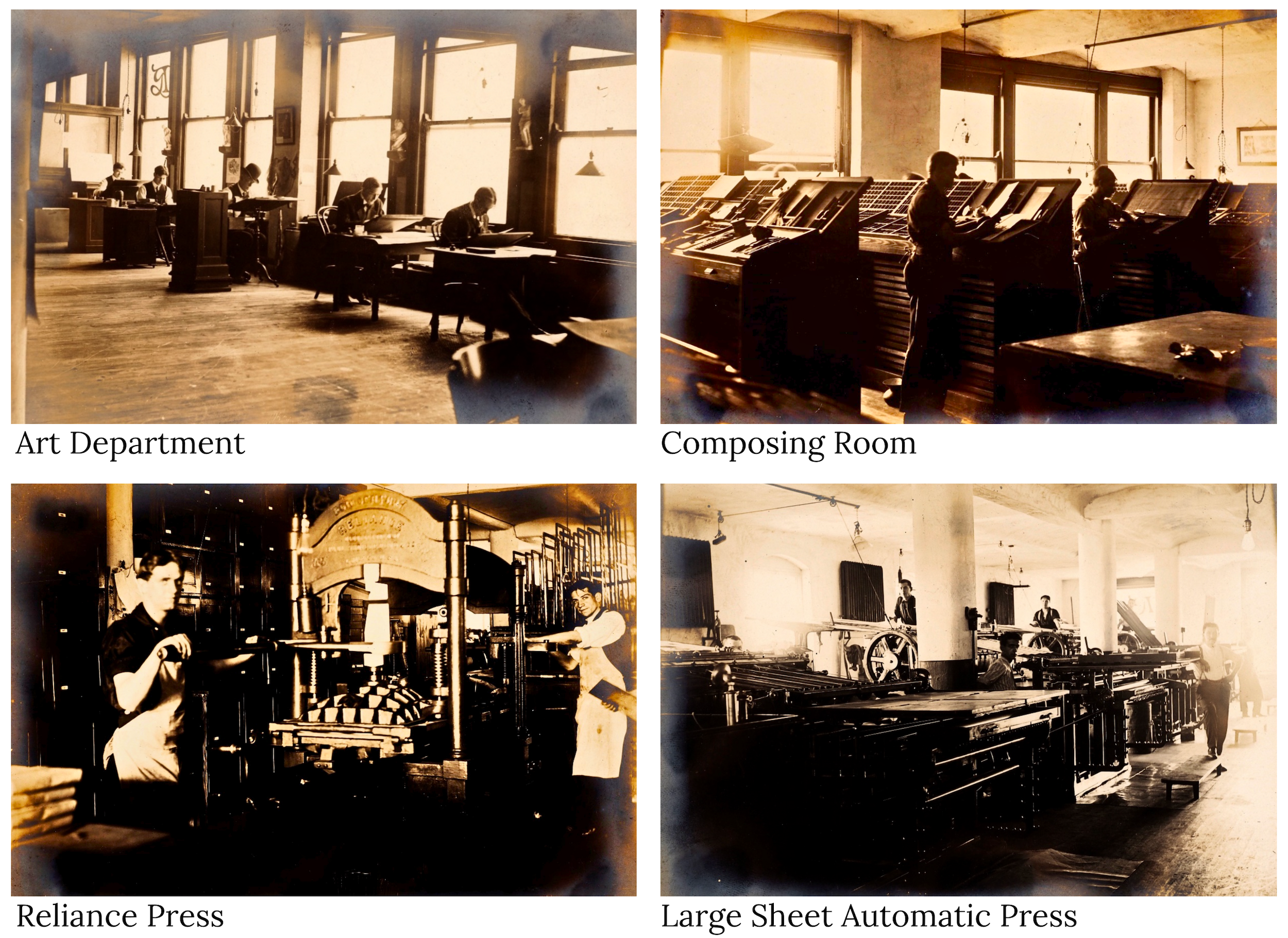

In 1905, the Toby Rubovits printing plant moved to the top three floors of a new fireproof steel building at 319-327 Fifth Avenue; or what would now be 517 South Wells Street (the building itself has since been demolished). As a dramatic change from the early days of the business, most of the machines in the new plant were powered by electricity; a fact Rubovits was quite proud of.

“We were the first people west of New York to put in electric power for a stamping machine, for driving and heating—and we would never use any other,” he said in 1907. “It is the only power to use for individual machines like this. The convenience and cleanliness of electric power would overbalance all other considerations.”

“We were the first people west of New York to put in electric power for a stamping machine, for driving and heating—and we would never use any other,” he said in 1907. “It is the only power to use for individual machines like this. The convenience and cleanliness of electric power would overbalance all other considerations.”

Rubovits was now so well known and respected within the industry that his opinions on matters of power sources and machinery selection were met with considerable interest. As such, he was routinely quoted in the ads of many of his product suppliers, including Monotype, the Inland Printer Company, and the Cline Electric MFG Co., among others.

While Toby was still the face of his business, though, all three of his sons were gradually taking on roles in the company, as well, helping to manage a rapidly growing team of highly skilled employees.

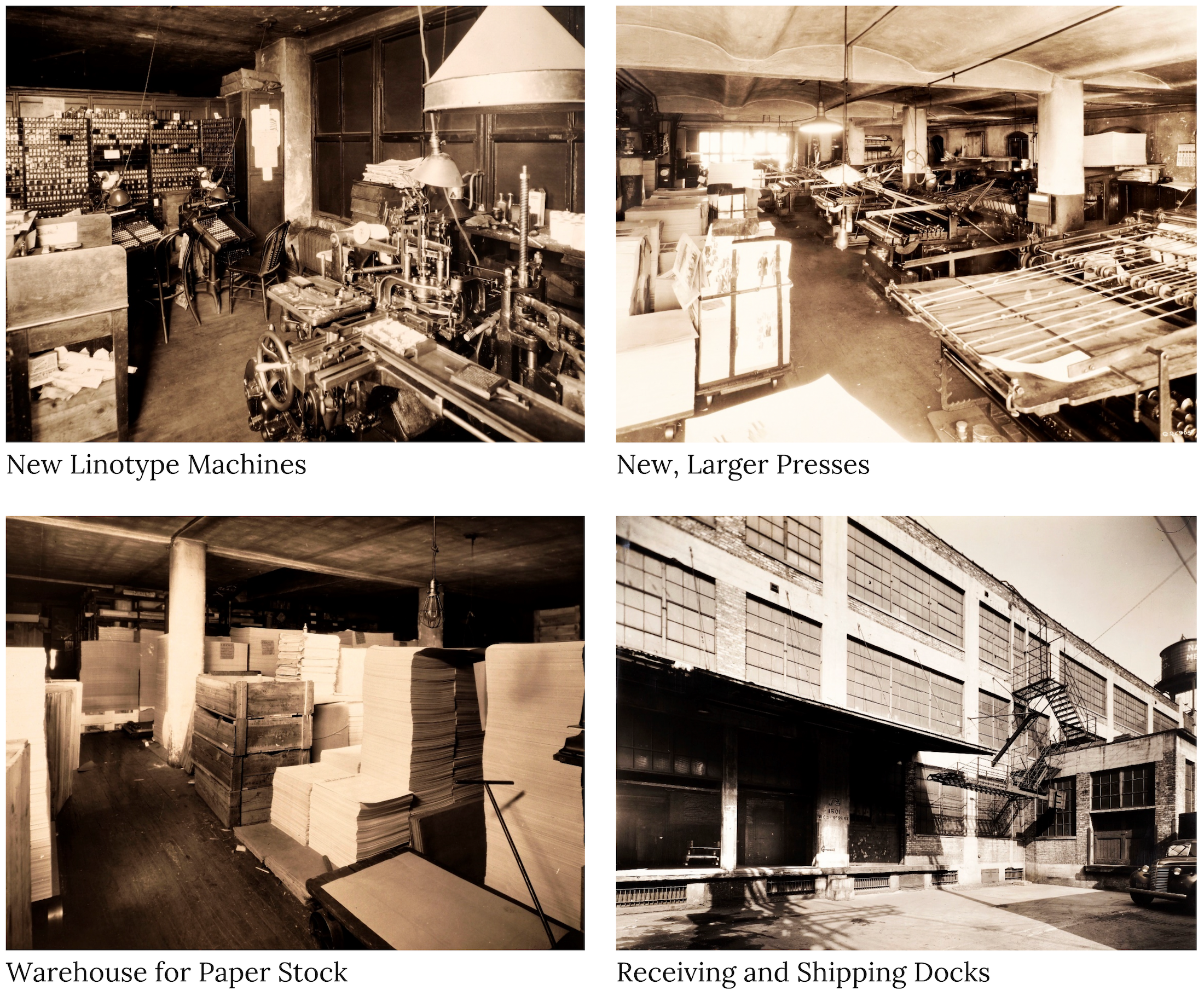

Inside the Toby Rubovits Printing Plant, c. 1910s

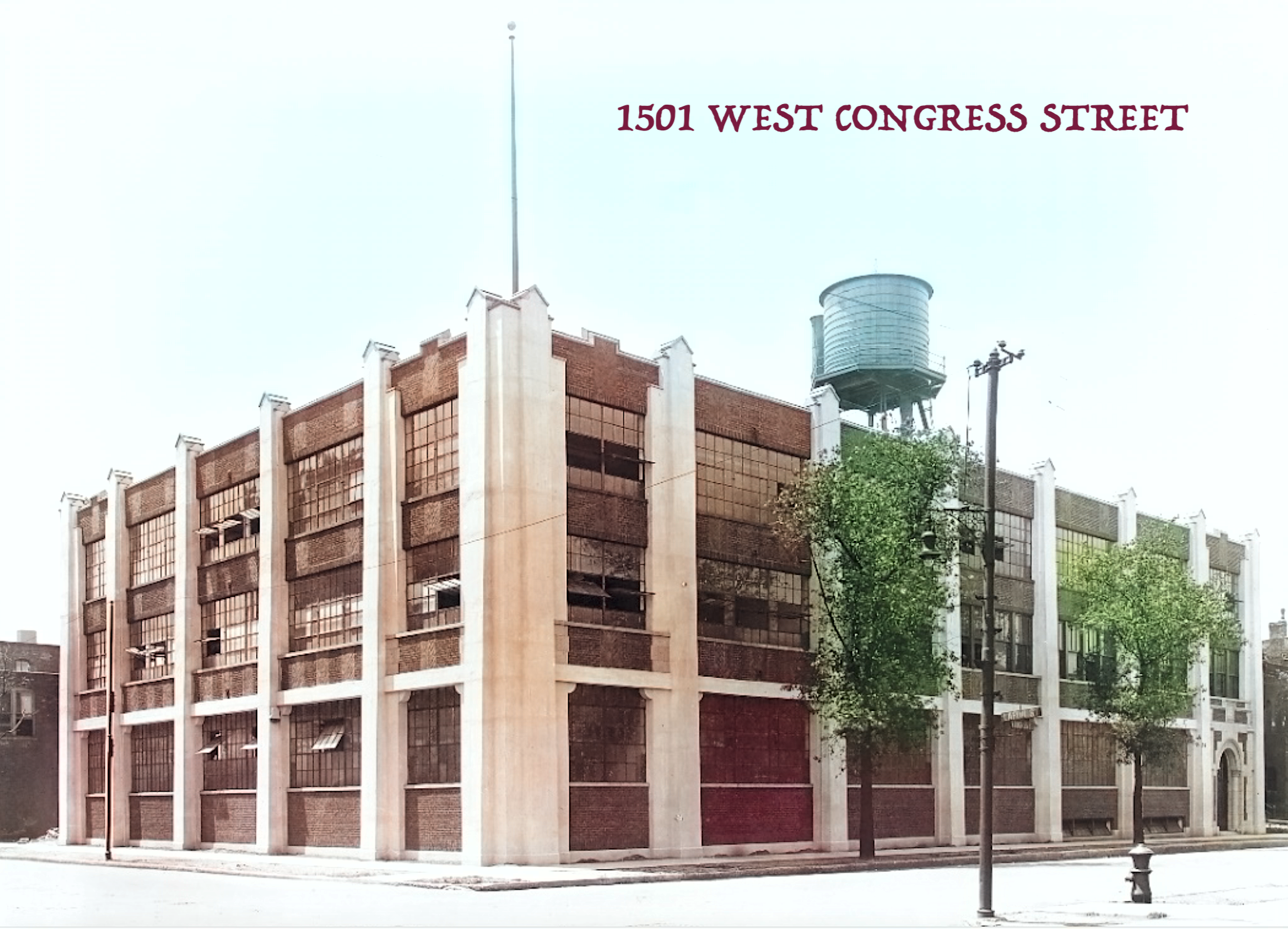

By the time the 1920s began, Toby Rubovits had been in the printing business for 50 years. He could have been pondering retirement at his age, but instead seemed quite determined to keep working, motivated by a mission to maintain a certain level of quality—not just in his own factory, but across an industry that was already starting to cut corners.

An editor with Bookbinding Magazine related a meeting with Rubovits around this time after visiting him at the Chicago plant. “Toby was his usual genial self, and he told me that his ambition was to see American book buyers become more ‘book conscious’—that is, to have a ‘feel’ for the better type of book.

“Booksellers should never be placed in the position of having to apologize to the customer for the general appearance of a particular volume,” the editor paraphrased Rubovits, “especially if the contents are by a good author. An attractive jacket, a neatly embossed cover or attractive cloth or imitation leather cover and better plates, in combination with a cheap grade paper, is the height of inconsistency, and it is a serious question whether it is good business policy from the standpoint of the publisher.”

[Left: Advertisements for Toby Rubovits, 1906-09. Right: A caricature drawing of Rubovits from the 1912 souvenir program of an industry event called the “Press Club Scoop,” held by the Press Club of Chicago at the Auditorium Theatre]

III. Off to Congress

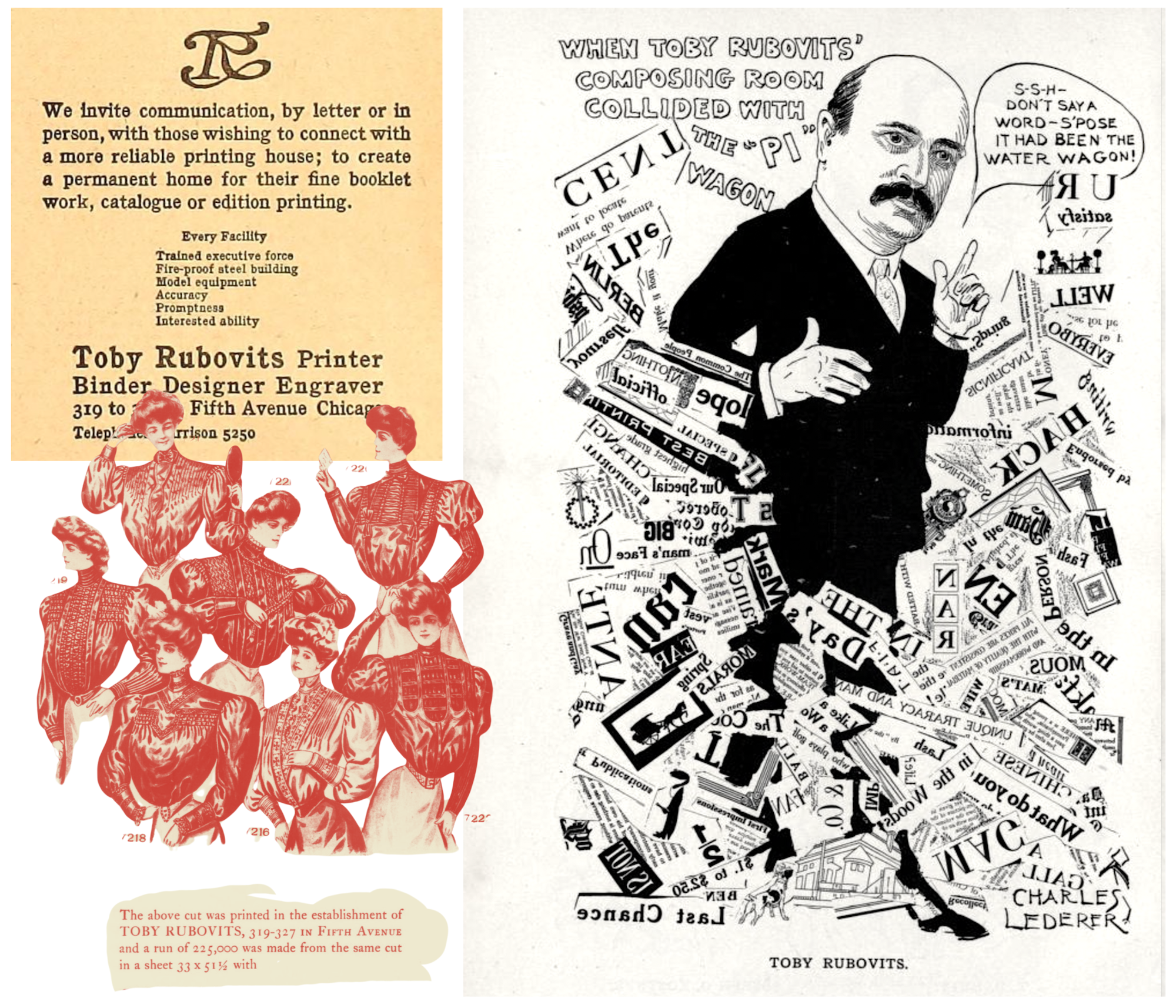

In 1923, a full 30 years after launching his independent shop, Toby Rubovits officially incorporated the business as Toby Rubovits, Inc. He also paid for the construction of a new, dedicated three-story printing plant at 1501 West Congress Street (this building has also since been demolished). The city’s leading industrial architect, Alfred S. Alschuler, was commissioned for the job.

“An example of effective consolidation of utilities is shown in the printing plant designed for Toby Rubovits in Chicago,” Alschuler wrote in a 1923 article for the Inland Printer. “The ground site is at the corner of two streets, with an alley in the rear. Former practice has often dictated that in such a location the building should run from street to alley, with a set-back from the property line, but in this case numerous advantages were obtained by a different procedure. The building was carried up to the property line, and set back twenty feet from the alley. The most decided gains from this arrangement were improvement in lighting, a larger proportion of north lighting, and the securing of a maximum clear floor space for plant operation.

“An example of effective consolidation of utilities is shown in the printing plant designed for Toby Rubovits in Chicago,” Alschuler wrote in a 1923 article for the Inland Printer. “The ground site is at the corner of two streets, with an alley in the rear. Former practice has often dictated that in such a location the building should run from street to alley, with a set-back from the property line, but in this case numerous advantages were obtained by a different procedure. The building was carried up to the property line, and set back twenty feet from the alley. The most decided gains from this arrangement were improvement in lighting, a larger proportion of north lighting, and the securing of a maximum clear floor space for plant operation.

“. . . The rectangular building secured by this layout lends itself better to printing purposes than if it were square and conformed to the lot lines. It also provides a floor space which is lighted from three sides and left clear of obstructions. . . . Another feature of the Rubovits building, which was designed for the erection of additional stories, was the use of a single elevator to handle freight and passengers both for the owner and for possible future tenants on the upper floors. By a carefully studied arrangement of the utilities and elevator openings, and the use of a passageway leading to the rear, this single elevator serves, without interference, as a freight or passenger conveyance for both the owner on the lower floor and the tenants on the upper floors.”

Inside the New Toby Rubovits Printing Plant, 1920s

[The full team of Rubovits employees at a company event in the 1920s]

There’s a reason Toby and his sons opted for a building optimized for adding more stories in the future. Business was reaching new heights during the Roaring ’20s, and with a team of 125 employees on board, the goal was to have a plant equipped for another 30 years of growth.

These dreams were mostly vanquished in October of 1929, unfortunately, when the stock market crash pulled a cloud over just about every mid-sized printing company. Survival would now depend on ingenuity, and, true to its history, Rubovits Inc. did its best to adapt.

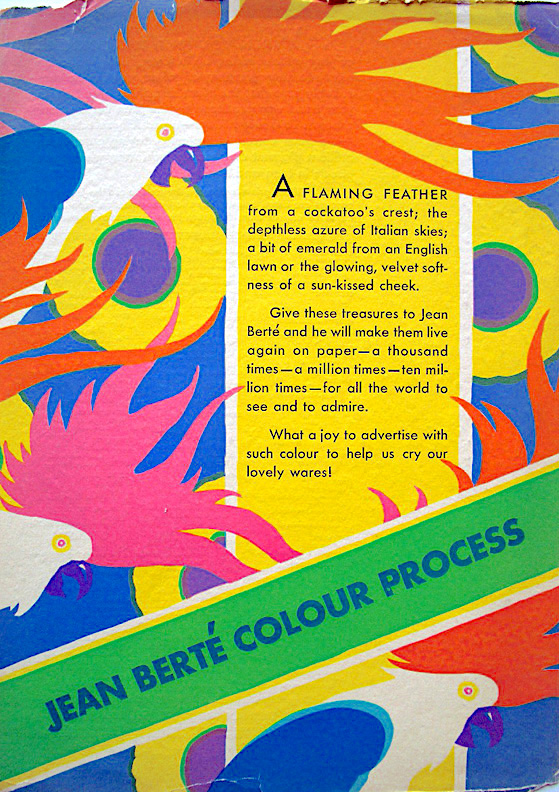

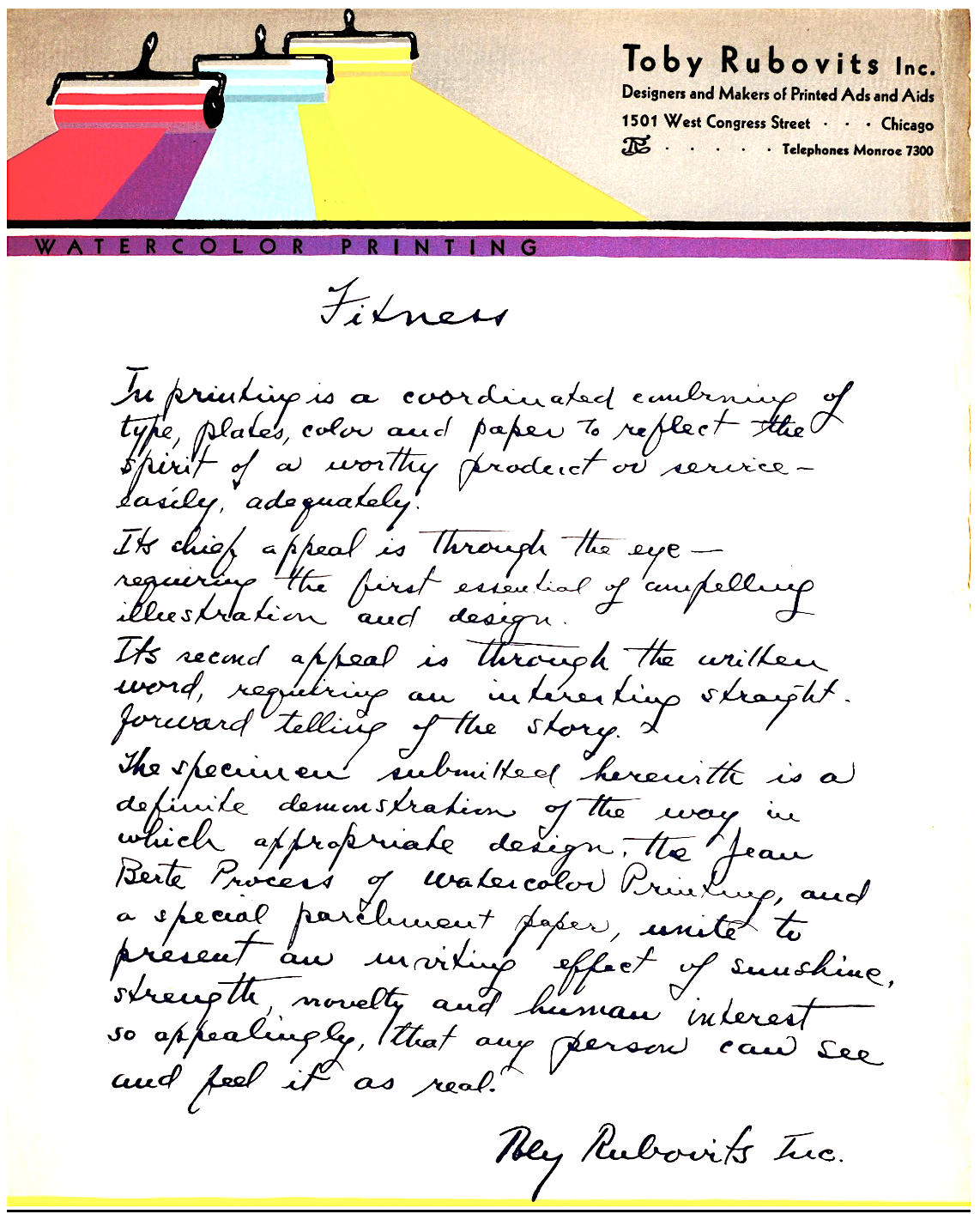

In the early 1930s, the company invested in a new letterpress printing process called the Jean Berté Process of Water Color Printing. A Rubovits promotional brochure from the period describes this newly acquired capability:

In the early 1930s, the company invested in a new letterpress printing process called the Jean Berté Process of Water Color Printing. A Rubovits promotional brochure from the period describes this newly acquired capability:

“There has long been a need in certain classes of printing to convey the vividness or delicacy of the artist’s original drawing to the finished work. In France such effects have been accomplished beautifully with the application of water colors by hand, or through stencils. . . . By the Jean Berté Process, actual water color inks may be applied on a modern printing press with results which, for all practical purposes, are indistinguishable from hand coloring. Bright and forceful colors, as well as pure and delicate pastel tints, give the printing the naturalness and fullness of color achieved in the artist’s original work. . . . The process is comparable in cost to regular letterpress printing, both as to cost of plates and actual printing operations.”

Normal letterpress processes involved acid-etching a photograph on to a copper plate and printing with oil-based inks. The Jean Berté Process relied on hand-cut rubber-faced letterpress blocks to print only the color images with luminous water-based inks. This water color printing was well adapted to announcements, brochures, posters, book jackets, envelope enclosures, and many other applications. It made artwork in the Art Deco style of the period look particularly vibrant, and Toby Rubovits spared no expense in promoting it through a series of beautiful brochures. While these certainly stand the test of time as an example of superior 1930s print design, the Jean Berté Process itself never gained lasting mainstream acceptance, leaving Rubovits Inc. in a rare position; a few steps behind its competition.

In the midst of this trying time, in 1935, company founder and patriarch Toby Rubovits died at the age of 78, leaving his sons Arthur Rubovits and Richard Rubovits to run the business. In the years that followed, that new generation was able to secure some important new clients, as the company printed catalogues for Harmony guitars and Stiffel lamps, among others. The most impactful partnership of all was the one Rubovits secured with one of the best known names in American industry: General Motors.

[Examples of Toby Rubovits printwork using the Jean Berté Process, 1930s]

IV. Electro-Motivation

Richard Rubovits, the youngest son of Toby Rubovits, served the Electro-Motive Division (EMD) of General Motors for 40 years, starting during the EMD’s early years in the 1930s. As the point-man between the EMD offices in La Grange, Illinois, and the Rubovits printing plant in Chicago, Richard worked closely with the staffs of both companies to put together books, specification brochures, art prints, and calendars promoting the EMD’s fleet of diesel locomotives. Rubovits also printed all the Christmas greetings sent to GM’s Electro-Motive employees, customers, and vendors.

After World War II, American railroads were rapidly replacing their remaining steam locomotives with those powered by diesel, most of which were built by GM’s Electro-Motive Division. So it was a vital period to be directly linked with such a symbol of mid-century American might.

After World War II, American railroads were rapidly replacing their remaining steam locomotives with those powered by diesel, most of which were built by GM’s Electro-Motive Division. So it was a vital period to be directly linked with such a symbol of mid-century American might.

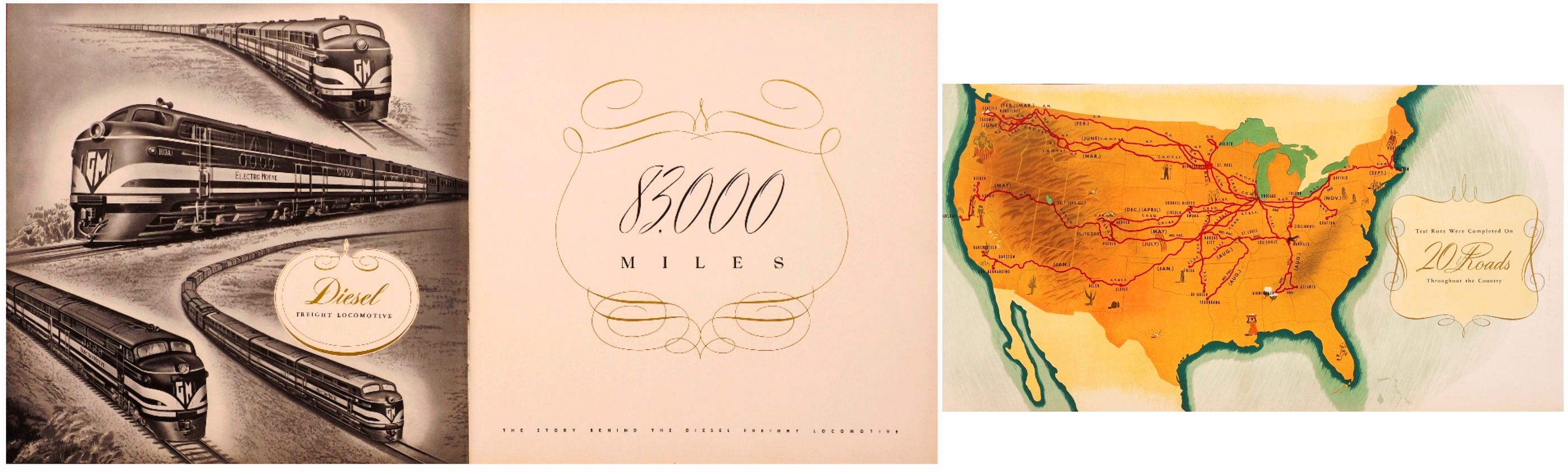

A signature piece from the Rubovits-GM relationship is an elaborate book Richard printed in the early 1940s for EMD, titled 83,000 Miles, The Story Behind the Diesel Freight Locomotive. Diesel locomotives were still new and their capabilities were relatively unknown to the general public at this point, so the book used some lovely graphics to showcase an exhaustive evaluation of EMD locomotives running on twenty important railroads. With its persuasive statistics on the superiority of diesel power over steam, the book was an important promotional tool for EMD, and one that found its way to the desks of most of the country’s railroad barons.

[Front cover, title page, and route map from 83,000 Miles, The Story Behind the Diesel Freight Locomotive, printed by Toby Rubovits Inc.]

When promoting sales to a particular railroad, EMD would have a commercial artist draw a dramatic picture of its diesel locomotive painted with that railroad’s color scheme. They would then commission Richard Rubovits to print as many as 1,000 copies of the picture and present them to the railroad execs. These 26”x17” prints would then hang in stations and offices all along the railroad’s routes.

The streamlined design and bright colors of these golden age diesel locomotives made the prints particularly appealing. Today, they remain popular collector items. That includes the smaller locomotive “data cards” like the one in our museum collection, which depicts the 4500 HP Diesel Locomotive that traveled on the Erie Railroad between Chicago and New York. Another slight variation of that same 4500 Erie loco is seen below.

Despite the reliable partnership with GM, Rubovits Inc. never quite recaptured the glory of its pre-Depression heyday. In the late 1930s, the Rubovits sons sold the Congress Street building and moved the plant to a smaller space at 127 South Aberdeen Street. By then, the company’s old letterpress equipment had become less competitive with the new offset printing technology taking over the industry.

Despite the reliable partnership with GM, Rubovits Inc. never quite recaptured the glory of its pre-Depression heyday. In the late 1930s, the Rubovits sons sold the Congress Street building and moved the plant to a smaller space at 127 South Aberdeen Street. By then, the company’s old letterpress equipment had become less competitive with the new offset printing technology taking over the industry.

Finally, after a precipitous slowdown in profits after World War II, the decision was made to liquidate the business in 1955. Arthur and Richard Rubovits remained in the trade, however, pursuing their craft with other printing companies. The family’s printing tradition also resurfaced again in 2020, as Richard’s son Donald Rubovits is using computer software to develop self-published books printed on today’s digital presses. The original Rubovits printer’s mark adorns each of these new books.

[Wallet sized locomotive calendar cards were printed by Rubovits in the hundreds of thousands]

[A photogravure process produced the relief on this copper plate. When the letterpress forces the inked copper plate against the paper, the ink on the raised part of the plate is transferred to the paper.]

[Left: Some of the booklets that helped reinforce EMD’s position as the dominant manufacturer of diesel locomotives. Right: Pages from an EMD specification book for a line of switching locomotives.]

[1930s letter showcasing Rubovits Inc.’s focus on design]

Sources:

“History of Toby Rubovits Inc.” – by Donald Rubovits, 2024

“Convenience and Cleanliness of Electric Power” – Chicago Tribune, March 17, 1908

“The Design of the Modern Printing Building” – Inland Printer, Sept 1923

“Bindery Brevities” – Bookbinding Magazine, Sept 1929

Chicago and Its Jews: A Cultural History, by Philip P. Bregstone, 1933

“Toby Rubovits, Printer Since ’71, Dead at 78” – Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1935

“Death Ends Rubovits’ Career” – Inland Printer, July 1935