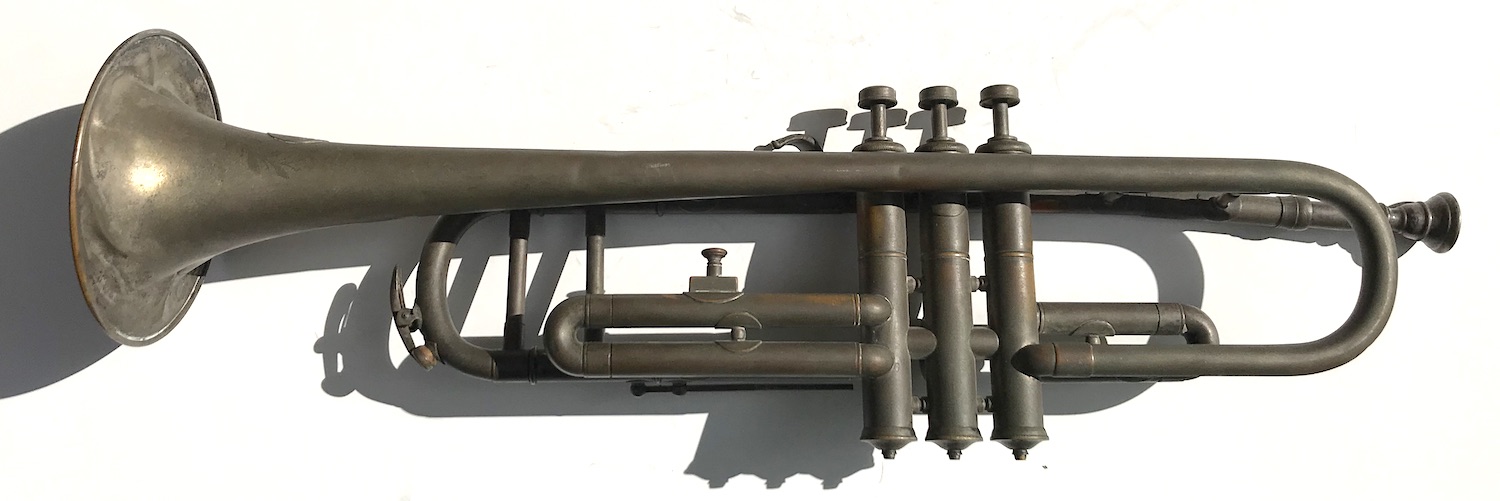

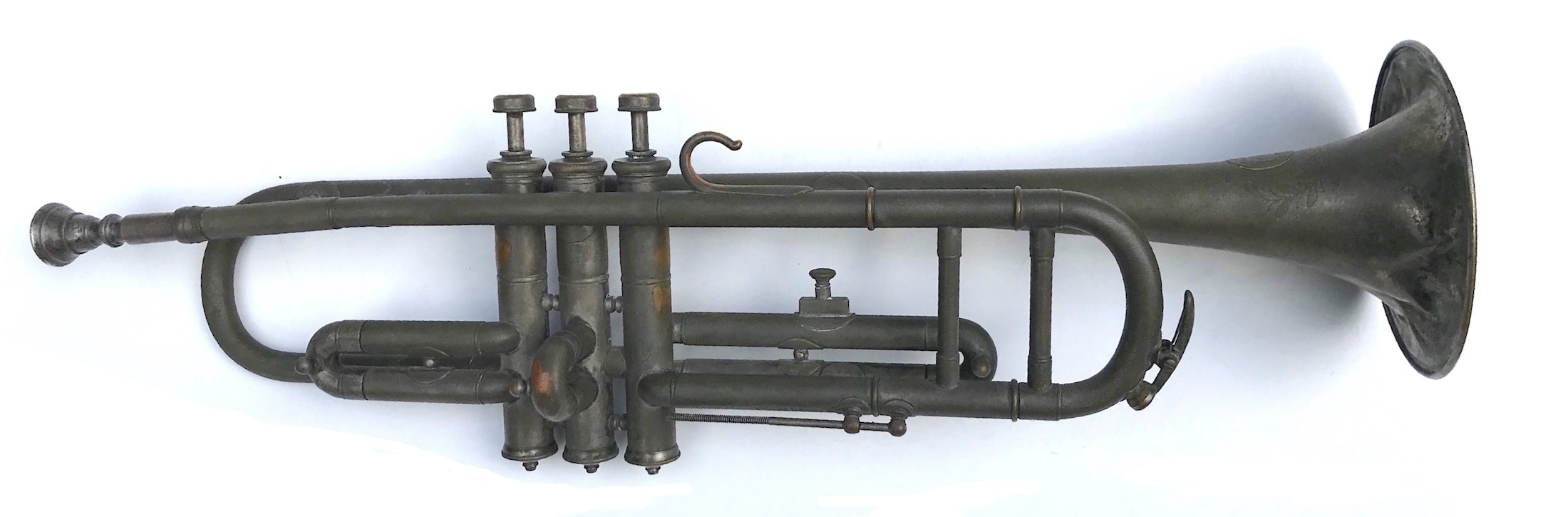

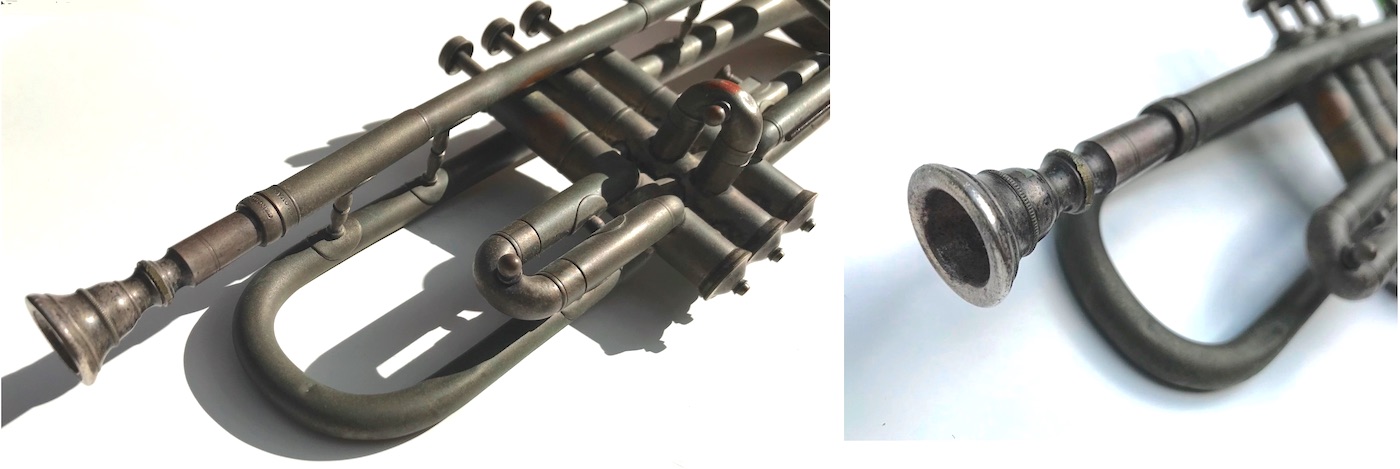

Museum Artifact: Tonk Sterling Shankless Trumpet, c. 1920s

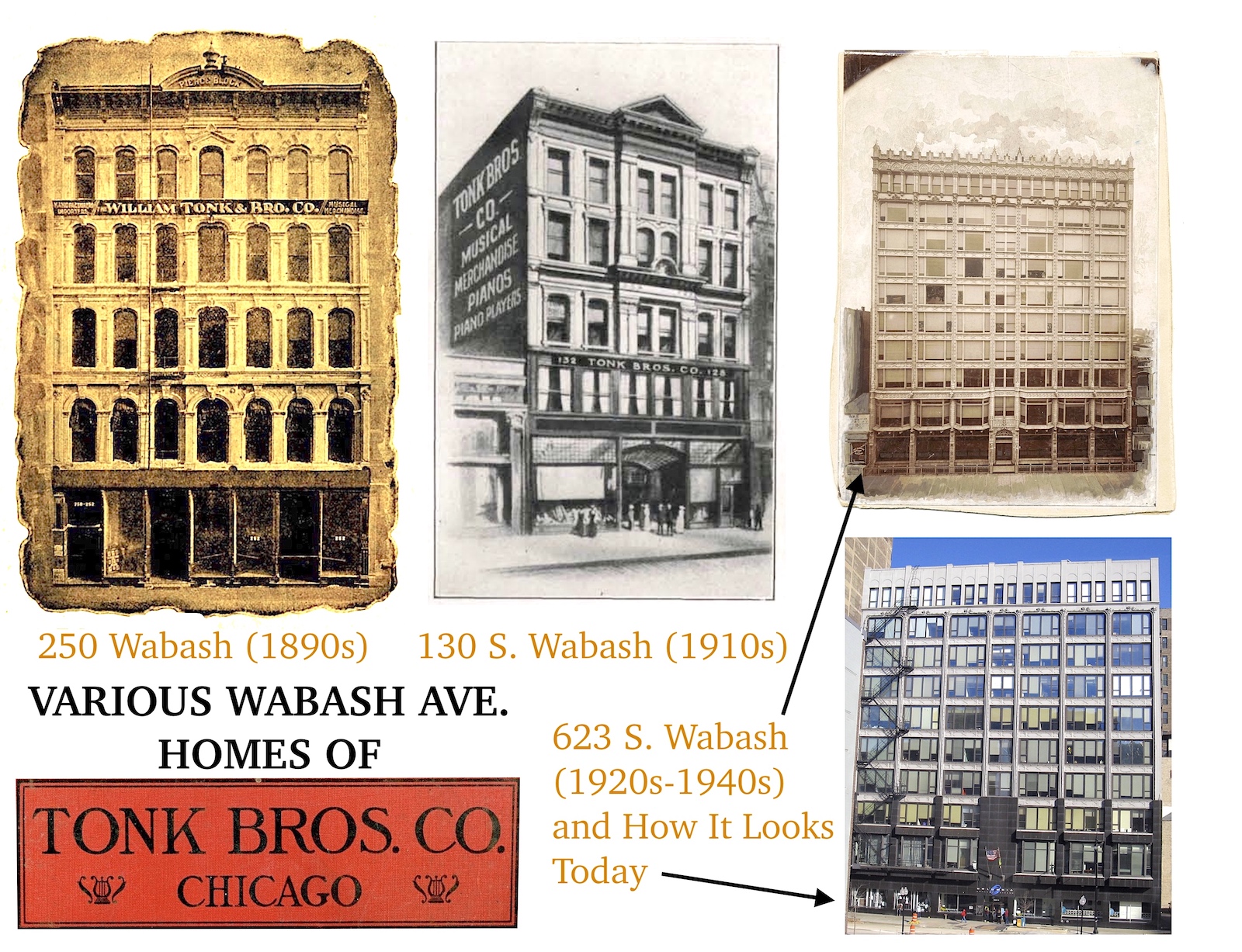

Made By: Tonk Brothers Company (Distributor), 623 S. Wabash Ave., connected with Tonk MFG Co., 2028 N. Clybourn Ave., Chicago, IL [Lincoln Park]

In a 1966 interview with Life magazine, jazz legend Louis Armstrong told the tale of the first horn he ever bought as a young boy in New Orleans, circa 1916:

“I couldn’t get enough money together to even talk about a horn of my own— used to rent one for each gig,” he recalled. “Then I found a little nickel-plate cornet for $10 in Uncle Jake’s pawn shop— all bent up, holes knocked in the bell. It was a Tonk Brothers—ain’t never heard of them. . . . I cleaned that horn out, scaled it good. It was all right.”

While it’s certainly bent-up much like the instrument mentioned above, the Tonk Brothers “Sterling” horn in our museum collection is sadly NOT the one once wielded by a teenage Louis Armstrong . . . at least, I’m fairly certain it’s not. Nobody knows where Satchmo’s fabled pawn shop Tonk ended up once he chucked it for a better model 100 years ago, so who’s to say?

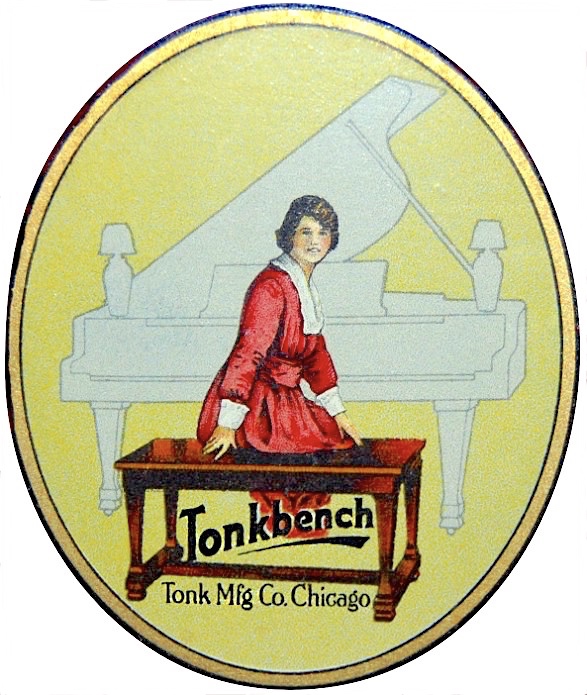

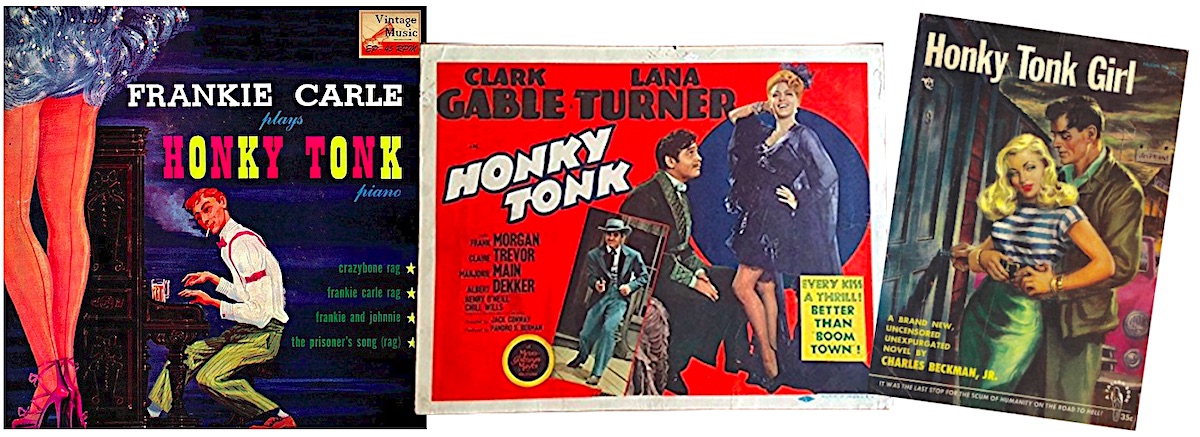

One thing is for sure; the Tonk Brothers name wasn’t quite so obscure as young Louis’s story might have suggested, nor were their products necessarily limited to the bargain bin. In fact, some etymologists theorize that the word “honky-tonk” itself—which Armstrong surely knew at a young age from playing gigs at such establishments—may have derived from the Tonk-manufactured pianos and piano stools that were often found in music joints during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

It may be impossible to ever fully confirm that theory, but it’s certainly easy to recognize just how pervasive the Tonk name was in the musical instrument industry, as the Tonk Brothers themselves organized and managed not one, not two, but three separate successful businesses from the Gilded Age through the Jazz Age. One of those entities, William Tonk & Bro., was based in New York, but the other two—the Tonk Brothers Company and the Tonk Manufacturing Co.—were longtime Chicago institutions.

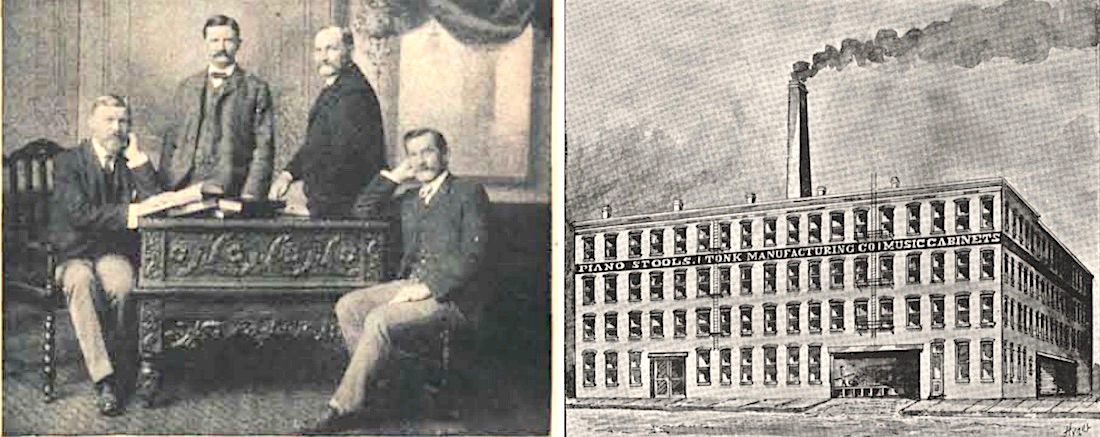

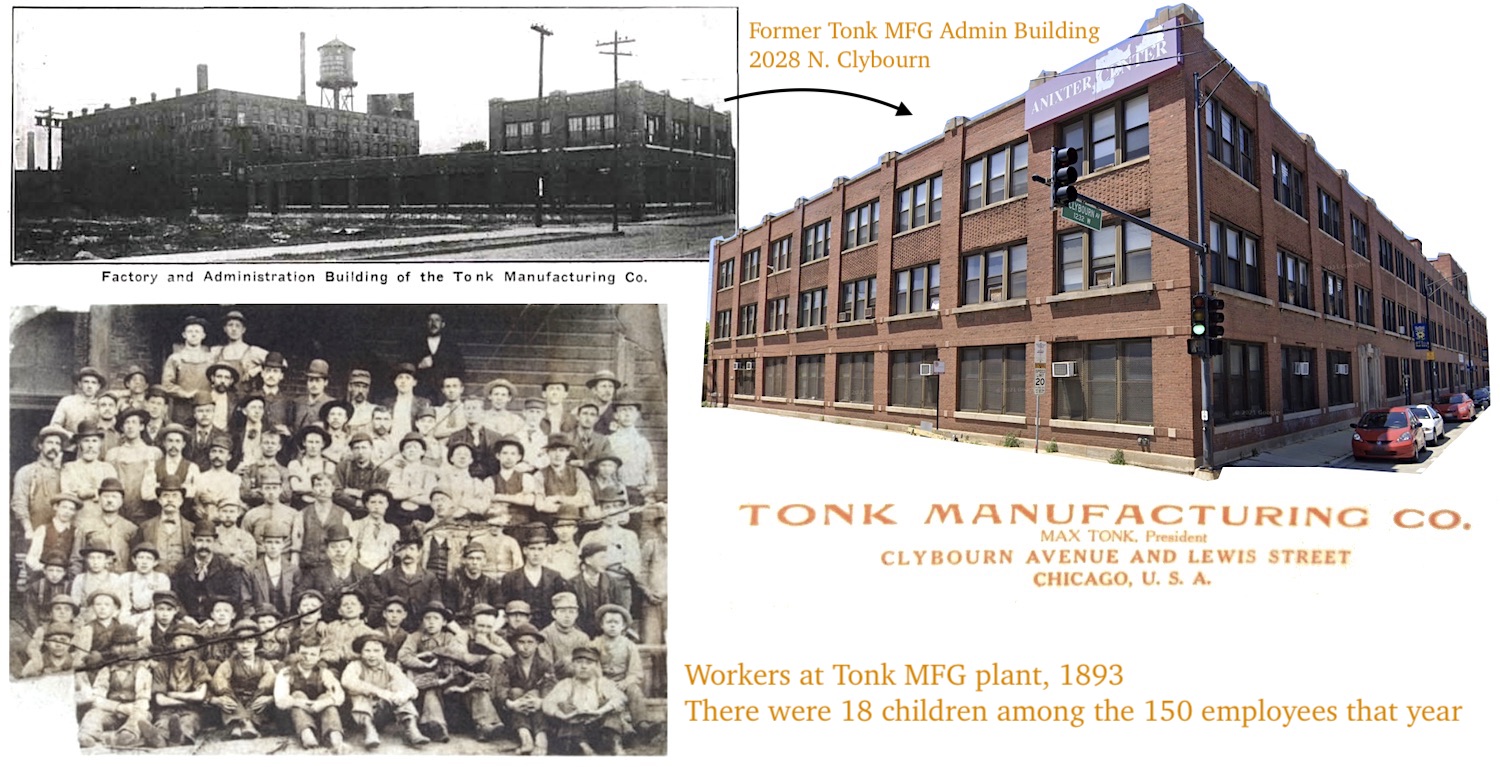

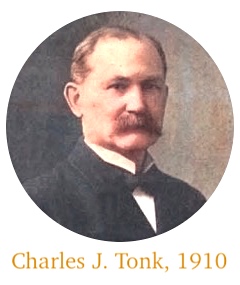

[The Tonk “Sterling” trumpet in our museum collection, pictured above, was distributed by the Tonk Brothers Company of Chicago, but wasn’t actually manufactured at a Tonk factory. Pictured on the left are the four Tonk brothers, from left: William, Albert E., Charles J., and Max. On the right is the factory of the Tonk MFG Co. at the corner of Clybourn Avenue and Magnolia, circa 1890; this plant mainly produced piano stools, benches, and other furniture.]

History of the Tonk Brothers, Part I: Max Tonk & the Tonk MFG Co. (est. 1873)

The first enterprise to bear the Tonk name was the Tonk Manufacturing Company, a “fancy furniture” business founded in Chicago in 1873 as Seaver, Tonk & Co., 87-89 West Lake Street. Best known for its line of quality piano stools and benches, this specific company was the brainchild of Max Tonk (b. 1851), second oldest son of German immigrants Johann Wilhelm Tonk and Albertine Tonk (nee Bauer).

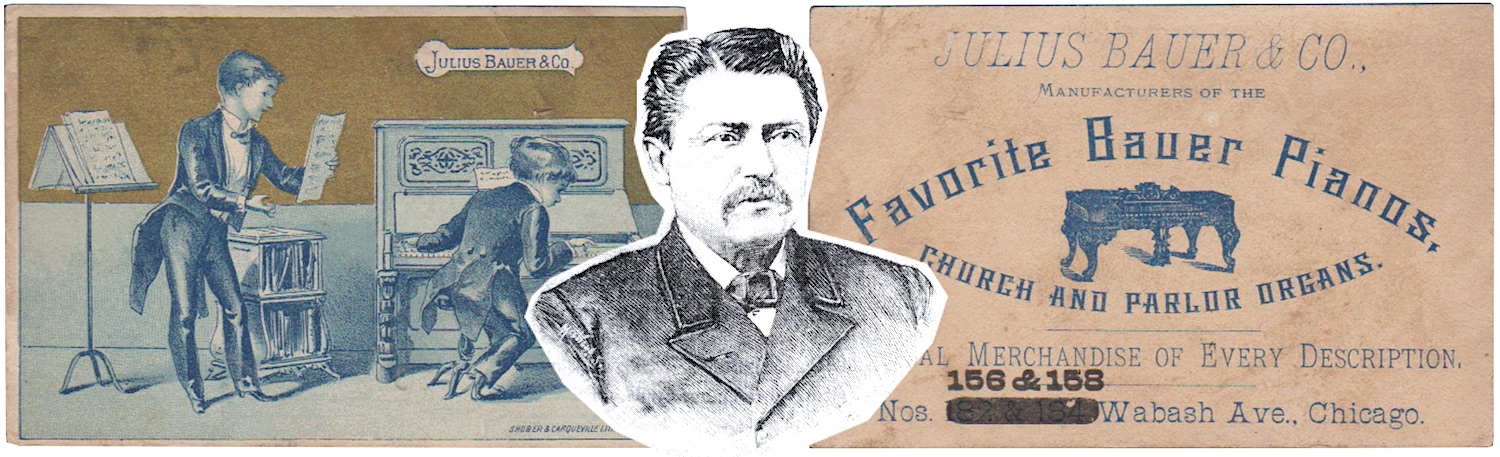

Max and his big brother William Tonk (b. 1848), were both born in Berlin, but made the long journey with their parents to America when they were still in diapers, giving them no vivid memories of the old country. Initially, the traveling Tonks settled in Newark, New Jersey, but by about 1857—following the birth of another son, Charles—they all headed west to join up with extended family in Chicago. This included Mama Tonk’s brother, Julius Bauer (or “Uncle Julius” to the Tonk boys), who ran his own music shop at 99 South Clark Street, producing and importing drums, strings, and the same type of silver and brass band instruments his nephews would be peddling 50 years later.

Max and his big brother William Tonk (b. 1848), were both born in Berlin, but made the long journey with their parents to America when they were still in diapers, giving them no vivid memories of the old country. Initially, the traveling Tonks settled in Newark, New Jersey, but by about 1857—following the birth of another son, Charles—they all headed west to join up with extended family in Chicago. This included Mama Tonk’s brother, Julius Bauer (or “Uncle Julius” to the Tonk boys), who ran his own music shop at 99 South Clark Street, producing and importing drums, strings, and the same type of silver and brass band instruments his nephews would be peddling 50 years later.

According to a write-up in Isaac D. Guyer’s History of Chicago (1862), Mr. Bauer had “long been associated with one of the great musical manufacturing houses at Leipsic [sic],” and his new Chicago store was now “one of the most attractive spots in this city for the lovers of this elegant art.”

As young boys, William and Max Tonk both started working in their uncle’s store, learning the ropes of the Victorian music biz and unwittingly setting up their own lifelong careers in the industry. While William was Bauer’s dependable bookkeeper and office manager, however, Max took a more roundabout path into becoming a businessman.

[The Chicago music store of Julius Bauer, pictured, was a key influence on his nephews, the Tonk brothers]

“I learned my trade in a woodworking shop on Lake Street, which, by the way, was then the principal street of the city,” Max Tonk told the Music Trades in 1913. “I secured a very good training in the work at that place.”

According to a story later told by his son Percy, Max also helped build drums for the Union Army during the Civil War, and later—when challenged by Julius Bauer to come up with an adjustable type of piano stool—he “carried out the idea,” using only a beer keg, some pipe, and pipe fittings to create “the original organ stool.”

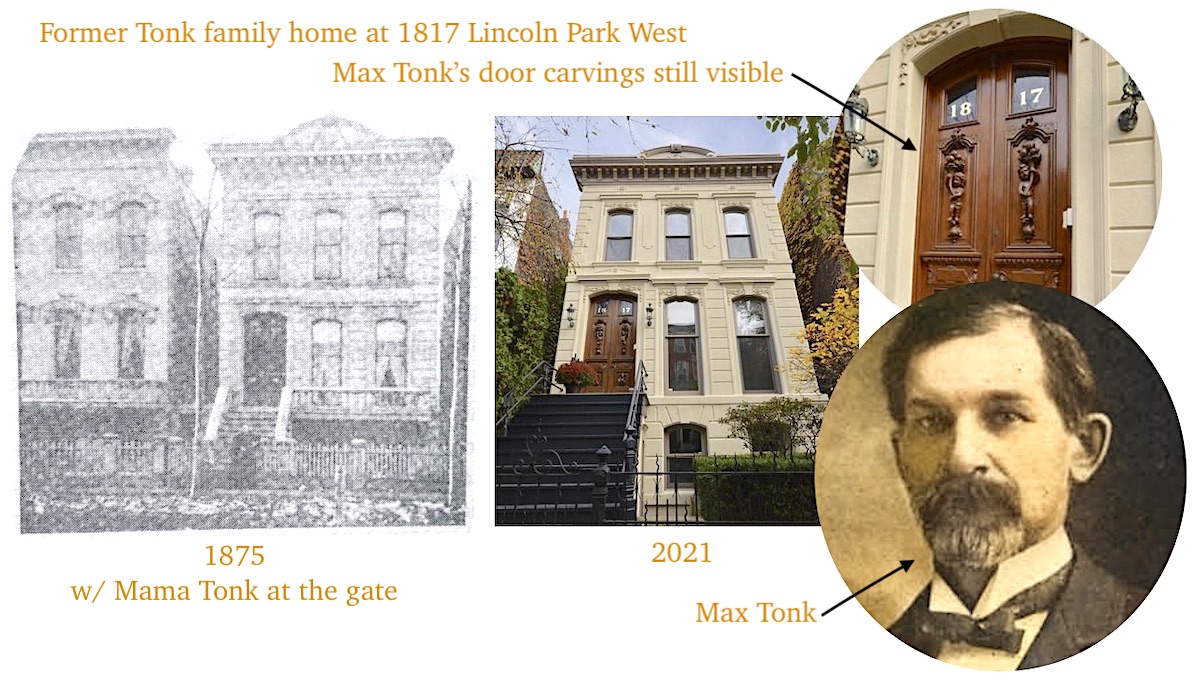

In 1870, a now 18 year-old Max was already listed in the U.S. census as a professional “carver.” His family had also grown to include four siblings: William, 22 (still a bookkeeper with Julius Bauer & Co), Charles, 14 (employed in a local newspaper office), and students Edward, 10, and Albert, 9. Whether by illness or accident, poor Edward died young, a family tragedy that was followed shortly by a national tragedy—the Great Fire of 1871—which consumed the Tonk family home, as well as Max’s woodshop and the Bauer music store.

In the aftermath, all of the Tonks quickly leaped into rebuild mode, with Max, in particular, eager to put his increasingly unique talents to use. When his parents commissioned a French architect to build them a new house, for example, Max personally carved the decorative front doorway, including a pair of cherubs that are still part of the home 150 years later, visible at 1817 Lincoln Park West. It was probably Max’s last gig as an amateur. By 1873, at age 22, he was a full fledged business owner.

“I went into business with another man under the name of Seaver, Tonk & Co.,” Max later recalled. “Our shop was at the corner of Lake and Jefferson streets, where at the time a majority of the factories were clustered.”

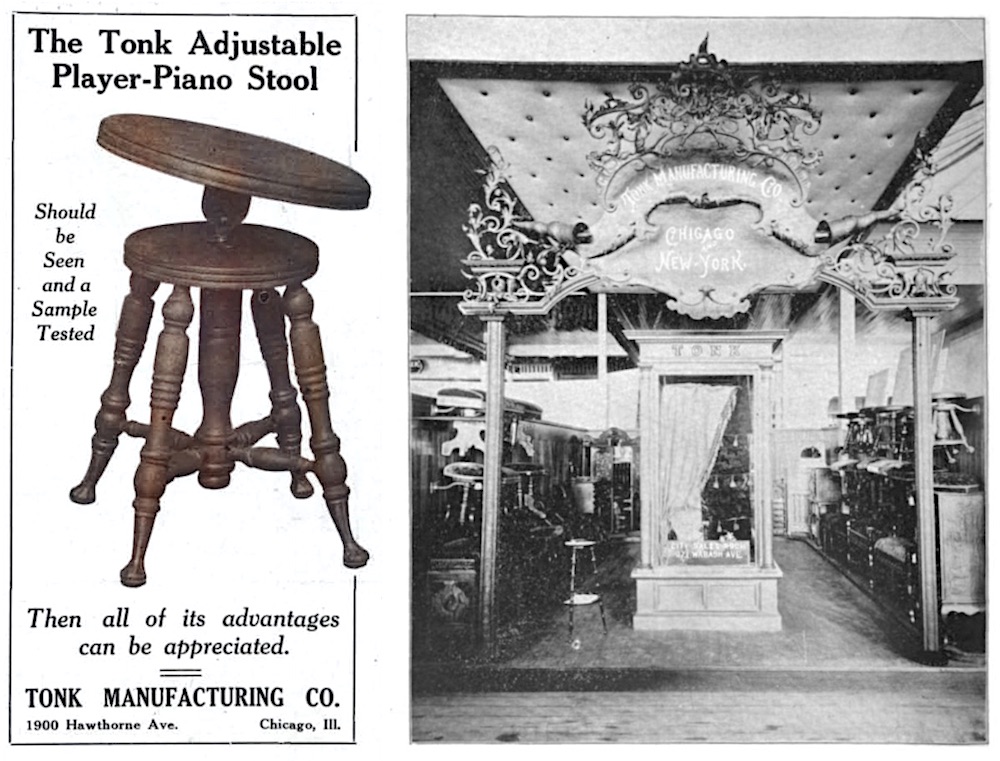

While the new business made quality, wood carved chairs and benches of various types, its calling card—from the beginning—was the type of niche item Uncle Bauer had helped inspire.

“My first product was a piano stool made of a wooden pillar to which three iron legs were fastened,” Max said. “The seat was either square or round and was covered with the everlasting hair cloth or reps or occasionally tapestry, the stuffing being either tow moss or hair and finished in ebony as, indeed, almost every stool at the time was. It wholesaled from $1.88 to $2.50. It proved to be quite popular and the sale of it cut deeply into the business of some Eastern people who had had things all their own way up to this time.”

During this era, harmoniums and pump organs were the common keyboard instruments of the home (space-efficient upright pianos hadn’t yet become widely available), and dealers rarely included stools along with them; so the Tonk MFG Company filled a significant need. Max, who bought out Mr. Seaver’s shares after a few years, even managed to collect a patent on an otherwise standard-looking two-legged stool, when his attorney “conceived the idea of proving how strong it was.”

During this era, harmoniums and pump organs were the common keyboard instruments of the home (space-efficient upright pianos hadn’t yet become widely available), and dealers rarely included stools along with them; so the Tonk MFG Company filled a significant need. Max, who bought out Mr. Seaver’s shares after a few years, even managed to collect a patent on an otherwise standard-looking two-legged stool, when his attorney “conceived the idea of proving how strong it was.”

“The breaking test showed it to be capable of supporting 3,600 LBS,” Max recalled, “and we secured our patent.”

In 1879, Tonk Manufacturing relocated to a new plant on the relatively unsettled west side of Lincoln Park, at Clybourn and Magnolia Avenue (at the time, the building also sat between Lewis Street and Hawthorne Avenue, two streets that were later built over).

“In 1882 we built an addition and in 1886 we were burned out,” Max said, noting that a bigger, better factory was already up and running by 1887. “It was about this time that the piano business made such tremendous strides and we found ourselves turning out for a stretch of three years an average of 125,000 stools a year.”

The company owned nearly five acres of factory ground and employed 150 Chicagoans by 1893, including 18 children, 19 women, and Max’s younger brother Albert Tonk, who’d joined the business as its treasurer. That same year, Tonk MFG made its presence known at the Chicago World’s Fair, hosting “one of the most interesting of all the splendid exhibits” in the Liberal Arts Building, according to a recap in the 1895 book, Musical Instruments at the World’s Columbian Exposition.

“We refer to the booth of the Tonk Manufacturing Co., whose display of piano and organ stools, music cabinets, scarfs and decorative specialties in musical requisites and art furnishings, was the most complete in the history of all the World’s Fairs.”

When Max and Albert Tonk set up their booth, they also included instruments shipped in from the New York firm operated simultaneously by the other two Tonk brothers, William and Charles.

[Left: Later advertisement for Tonk Adjustable Player Piano Stool, 1913. Right: the Tonk exhibit at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition]

Part II. William Tonk & Bro. (est. 1881)

While his younger brother Max was the trained furniture carver, William Tonk was no slouch either when it came to arts and crafts. Even before going to work at his uncle Julius Bauer’s music shop at the age of 12, he was already challenging himself to hand-make anything his parents either couldn’t or wouldn’t buy for him.

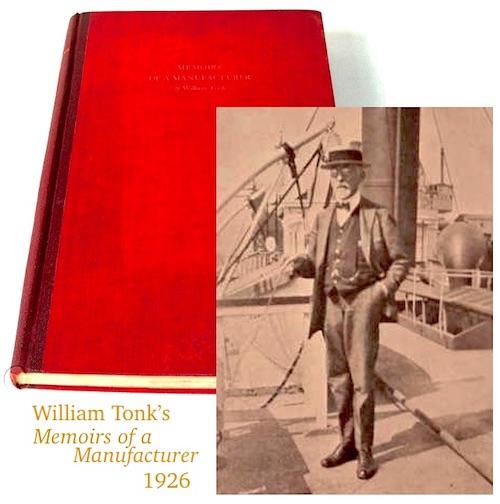

“I displayed my aptitude for mechanics in a number of ways,” William wrote in his 1926 autobiography, Memoirs of a Manufacturer, specifically recalling a washstand, a sleigh, and a semi-functional rowboat that he brought to fruition as a pre-teen. “Those are helped who help themselves,” Tonk decided in retrospect. “Many youngsters are spoiled, often for life, by too often being humored and helped instead of being obliged to do for themselves.”

“I displayed my aptitude for mechanics in a number of ways,” William wrote in his 1926 autobiography, Memoirs of a Manufacturer, specifically recalling a washstand, a sleigh, and a semi-functional rowboat that he brought to fruition as a pre-teen. “Those are helped who help themselves,” Tonk decided in retrospect. “Many youngsters are spoiled, often for life, by too often being humored and helped instead of being obliged to do for themselves.”

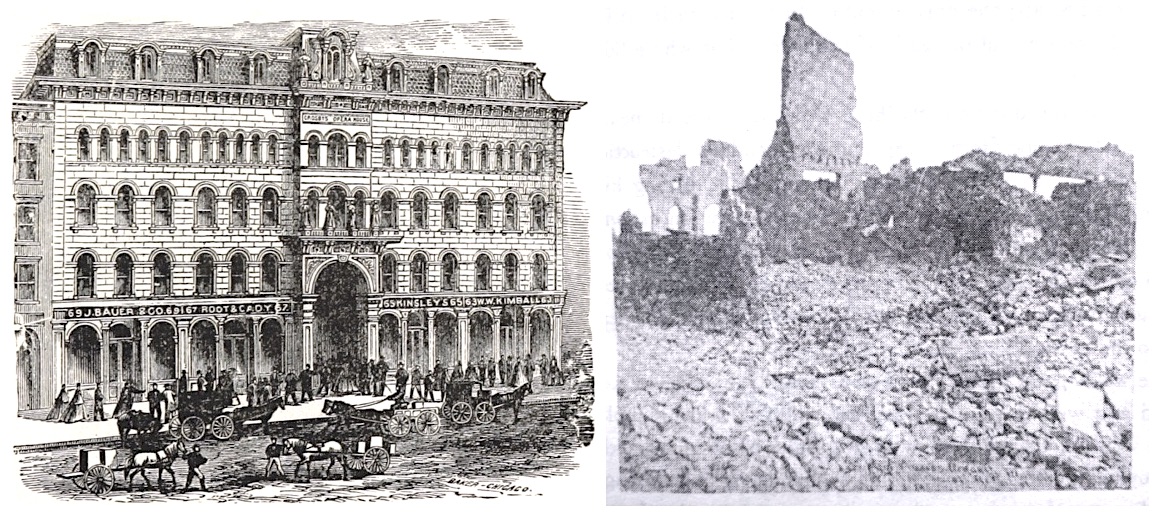

While still a teenager, William followed his uncle’s business from its original Clark Street location to a prime new spot inside Chicago’s majestic Crosby Opera House, where some other noted music dealers—including W. W. Kimball and Root & Cady—also had storefronts. The keen-eyed William was unavoidably absorbing the tricks of the trade from the best in the business, and when his grandfather’s cooperage shop started making drums for the Union Army during the Civil War, he found an additional outlet for his mechanical chops, joining his brother Max in that effort.

By the age of 23, William was already fully in charge of the finances and day-to-day business of Julius Bauer & Co.. This certainly added to the panic he felt on the morning of October 8, 1871, when his brother Charles awakened him with a warning of the massive fire making its way north across the city. “It appeared like an immense caldron, spitting fire and cinders which illuminated the heavens, its reflection turning night into day,” William later wrote.

[Left: The Crosby Opera House in Chicago, where William Tonk worked for Julius Bauer & Co. from about 1865-1871. Right: The ruins of the same opera house just after the Great Fire of 1871]

The Tonk family spent much of that day literally on the run, retreating to a field with a collection of valuable possessions wrapped in a rug. Their home and offices were lost, but William Tonk had managed to preserve the contracts and financial records of Julius Bauer & Co. in a safe, which he later recovered from the ashes of the Crosby Opera House. “The baking reduced the paper to a black charcoal, as it were, but did not obliterate the writing.”

With its books intact, Bauer & Co. re-opened and grew anew along with the city around it, soon occupying a storefront in the brand new Palmer House Hotel, followed by its own building at 182 Wabash Avenue. By 1880, it was a true family affair, with William Tonk as manager, his brother Charles as superintendent, and their father Wilhelm now in the fold as a clerk—not to mention several other employees from the Bauer side of the family tree.

After 20 years inside the comfort of this profitable and reputable family business, however, William Tonk soon longed for a new challenge. “My ambition had been to become something more than an employee,” he wrote, adding that his brother Max—by now already succeeding in his piano stool business—encouraged him to jump in the deep end.

Finally, William announced he was leaving Chicago for New York City, greatly disappointing his uncle Julius. His new venture, in which he was joined by his brother Charles, was Wm. Tonk & Bro., a wholesale business specializing mostly in imported European musical instruments.

Finally, William announced he was leaving Chicago for New York City, greatly disappointing his uncle Julius. His new venture, in which he was joined by his brother Charles, was Wm. Tonk & Bro., a wholesale business specializing mostly in imported European musical instruments.

“I made my start in the spring of 1881, at 47 Maiden Lane (NYC),” William wrote. “By strict economy and vigorous energy I succeeded in making some money the first year.”

Rather than seeing New York’s established piano makers as formidable foes, William instead did his best to form friendships with big wigs like William Steinway and Henry Behning . . . he even married the latter’s sister, Adelina, in 1882.

Using their experience and connections in the industry, William and Charles Tonk built up their business in New York just as quickly as Max Tonk had in Chicago. Exclusive distribution deals with a pair of French firms—the Schwander piano company and Chevrel Marquetry (a specialist in piano panel decorations)—built up Tonk’s esteem, and growing demand soon forced a move to a bigger headquarters at 26-28 Warren Street in Lower Manhattan.

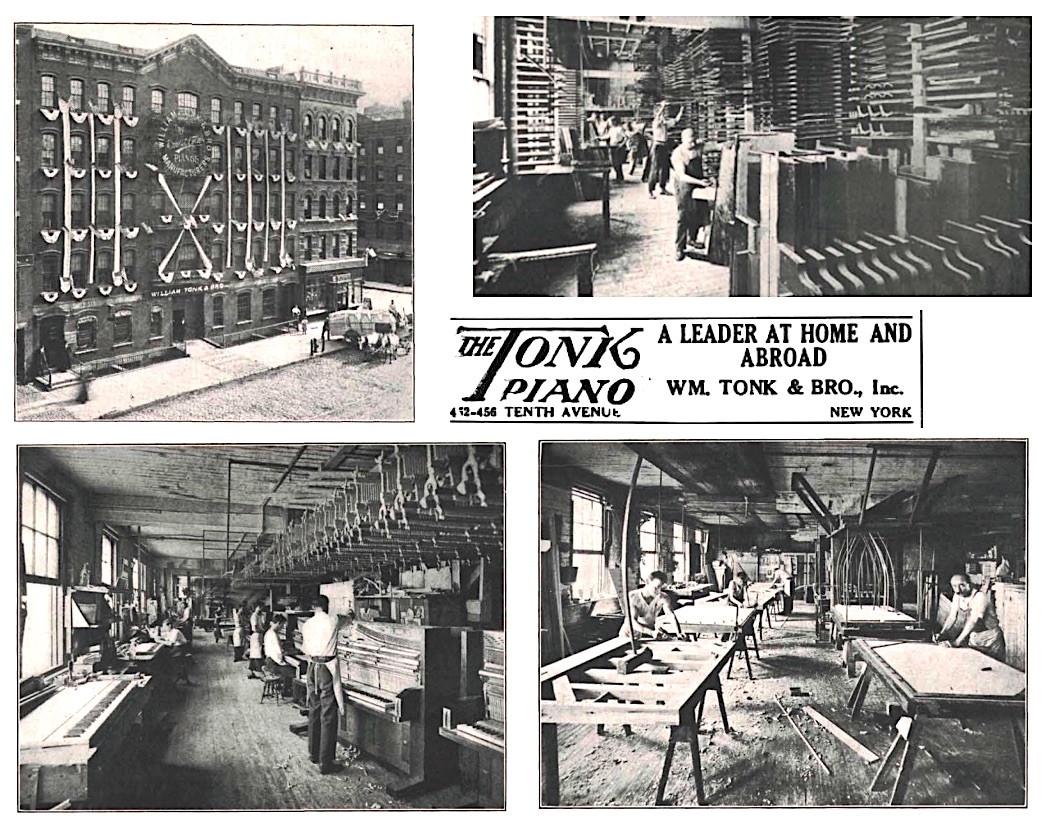

A factory was also opened in New York on 35th Street in the 1890s, which initially focused on making string instruments; particularly guitars and mandolins under the “Edwin” brand name—a nod to one of William’s sons. Later, “the piano department became so extended,” according to William, “that in 1897 we were led to manufacture the Tonk piano” in that same 35th Street plant.

[The Wm. Tonk & Bro factory near 10th Ave. and 35th Ave. in New York City, as it looked in 1910, including views of the exterior (top left), Varnishing Dept. (top right), Finishing & Side Glueing Dept. (bottom left), and Bellying Dept. (bottom right)]

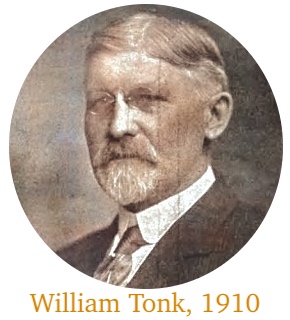

Crossing into the 20th century and the peak era of the upright and player piano craze, William Tonk became one of the industry’s elder statesmen; regularly celebrated at the meetings of the National Piano Manufacturers Association and inside the pages of the big trade publications of the day.

“The record of the house of William Tonk & Bro., Inc., emphasizes that their ideals are in sympathy with those of the founders of the industry,” trumpeted the Music Trades in a 1910 article. “From the start they have made a good piano. They have never ceased in their endeavor to improve their product, so that today the Tonk piano is held in high esteem by the trade at large.”

“Mr. [William] Tonk is one of the best known, most intelligent, and broad minded men in the business,” the same magazine reported in 1905. “He is a traveled man—a man of culture—and both by education and natural disposition inclined to be fair in any position in which he may be placed, or with regard to any subject he may take up for discussion.”

“Mr. [William] Tonk is one of the best known, most intelligent, and broad minded men in the business,” the same magazine reported in 1905. “He is a traveled man—a man of culture—and both by education and natural disposition inclined to be fair in any position in which he may be placed, or with regard to any subject he may take up for discussion.”

In truth, as William got older, he wasn’t always quite as “broad minded” in his assessment of new trends in popular music. For example, around the same time Louis Armstrong was learning to play his Tonk cornet, William Tonk was loudly proclaiming his own dislike for the new type of “discordant music, which, much to the dismay and displeasure of lovers of real harmonious music, has become ‘fashionable’ among ‘our younger set.’ How jazz music, which is produced by false, discordant notes, can find favor, even with some educated people, is hard to explain,” Tonk wrote in his memoir.

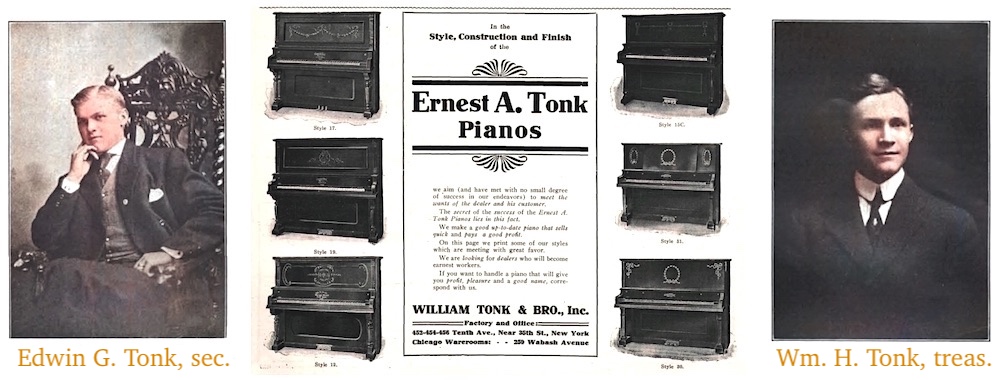

Fortunately, by this point, it was less necessary for William to have his finger on the pulse of America’s youthful music makers. His sons entered the business in the early 1900s, starting with William H. Tonk (b. 1884)—who took over management of the new Tonk & Bro. factory at 452 10th Avenue in 1903—and then Edwin G. Tonk (b. 1886), who became a secretary and sales manager for the business for many years.

Interestingly, when it came time to choose a brand name for one of the popular new Tonk upright pianos at the turn of the century, the honors went to neither of these sons—but instead to William’s favorite nephew Ernest A. Tonk (b. 1889), a son of Albert Tonk still living back in Chicago. Ernest grew up to be a well known painter of Western landscapes and had no connection to the music biz. The prominent use of his name on those early Tonk upright pianos, however, continues to create plenty of confusion for anyone trying to untangle the threads of this family narrative 100+ years later.

[William Tonk’s sons Edwin and William H. joined Tonk & Bro. in New York in the 1900s, but one of the company’s top selling pianos of that decade was actually named in honor of their cousin Ernest A. Tonk, who was supposedly William Sr.’s favorite nephew back home in Chicago (Ernest was a son of Albert Tonk and eventually became a painter of Western-inspired art in California]

. . . Which brings us to the third and final leg of the Tonk musical triad . . .

Part III. Charles Tonk & the Tonk Bros. Company (est. 1892)

Up until 1890, the Chicago business of Max Tonk and the New York business of William Tonk were fairly independent and unaffiliated with one another. This changed when William decided to open a branch office of Wm. Tonk & Bro. in Chicago.

The move reunited the family in some ways, as Max agreed to share some of his office space on Wabash Avenue to create a headquarters for William’s western interests. As part of the deal, their brother Charles Tonk—who’d been living in New York for nearly a decade—also returned to Chicago as a sort of go-between for the two firms. He was 35 now and, as a typical Tonk, attacked his new role with considerable ambition.

“My brother [Charles] was considered one of the best small-goods men in this country, especially capable in violins,” William Tonk wrote in his memoir. “His kindly disposition and strictly fair and honorable dealings in all matters in and out of business made for him a multitude of friends. ‘Charley Tonk’s word is as good as his bond’ was not an infrequent remark.”

“My brother [Charles] was considered one of the best small-goods men in this country, especially capable in violins,” William Tonk wrote in his memoir. “His kindly disposition and strictly fair and honorable dealings in all matters in and out of business made for him a multitude of friends. ‘Charley Tonk’s word is as good as his bond’ was not an infrequent remark.”

Charles, who’d worked in a newspaper office in his younger days, was arguably the most modern 20th century thinker of the Tonk clan. While he agreed with his brothers that the “merit” of Tonk products spoke for itself, he didn’t see that as any reason to muzzle the firm’s promotional efforts.

When asked about advertising in a 1900 interview, Charles told the Music Trade Review that “really satisfactory results can only be achieved by constant ‘hammering.’ These are busy times, and live men, in any walk of life, have so many details to think of and so much to do, that they must have things brought to their notice over and over again, as a rule, before they will take active steps to investigate.”

With the blessing of his brothers, Charles quickly transformed the “western office” of Wm. Tonk & Bro. into a new stand-alone wholesale business, which was eventually renamed the Tonk Brothers Company in 1906, with youngest brother Albert Tonk on board as secretary.

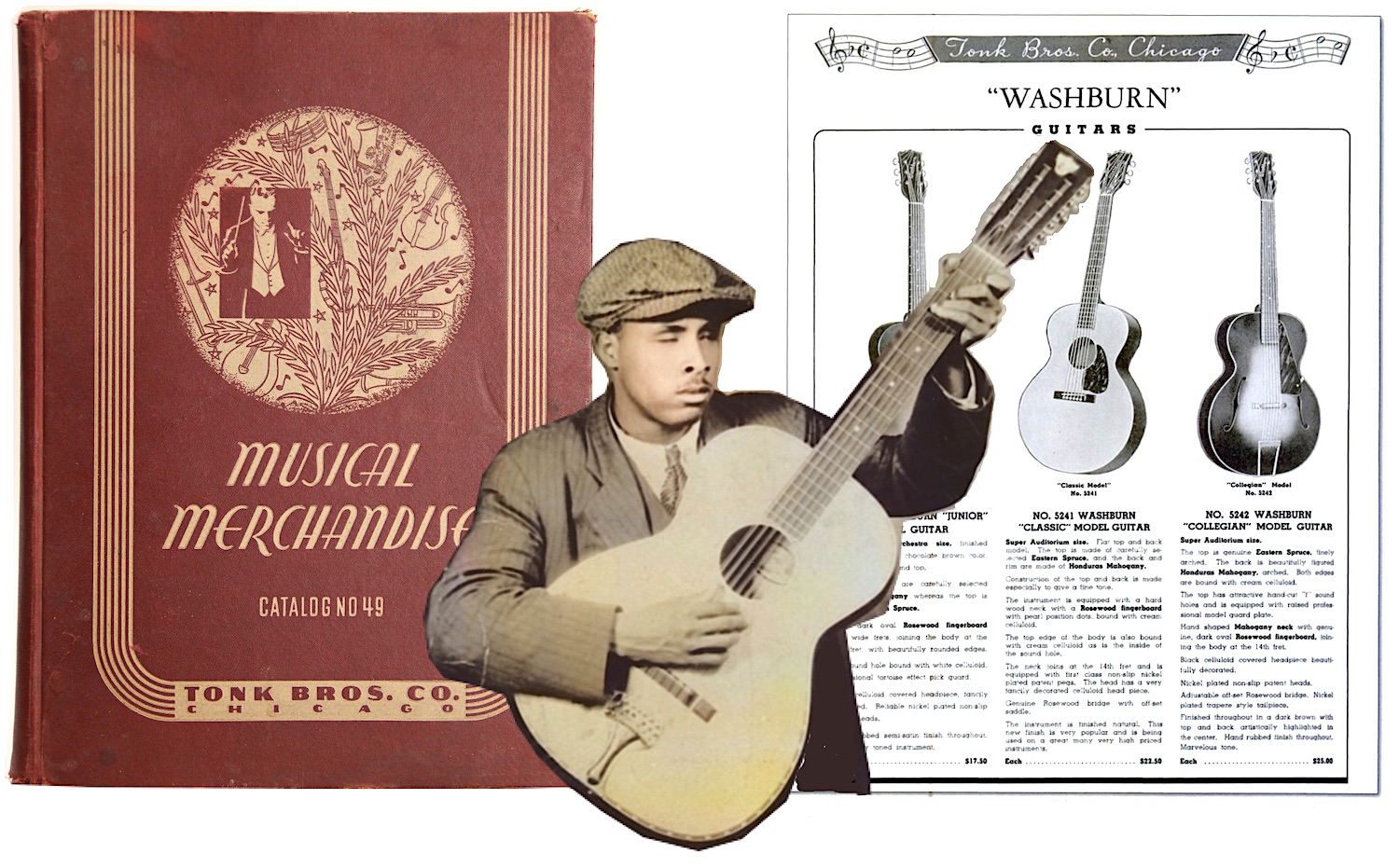

Tonk Brothers didn’t just sell instruments and furniture produced by Max’s and William’s factories, but a wide range of other products from other leading houses. This positioned the company more as a rival to Chicago’s best known wholesale music house, Lyon & Healy.

As the fates of those two firms moved in opposite directions later in the 20th century, Tonk actually was able to purchase Lyon & Healy’s musical merchandise department in 1928, including L&H’s popular Washburn brand of guitars and string instruments. Tonk Bros. catalogs also featured Chicago-made instruments produced by Regal, Ludwig, Harmony, and Deagan, among numerous other eastern and imported goods.

The “Sterling” name, which appears on the Tonk Bros. trumpet in our museum collection, came to prominence in the 1920s, and it appears to have originated from an existing brand of strings that Tonk acquired in 1919. From there, the company used the name liberally on a broad line of products, as the 1922 catalog advertised not just Sterling cornets, slide trombones, baritones, and basses, but also accordions, guitars, and flat-back mandolins under the same banner.

The “Sterling” name, which appears on the Tonk Bros. trumpet in our museum collection, came to prominence in the 1920s, and it appears to have originated from an existing brand of strings that Tonk acquired in 1919. From there, the company used the name liberally on a broad line of products, as the 1922 catalog advertised not just Sterling cornets, slide trombones, baritones, and basses, but also accordions, guitars, and flat-back mandolins under the same banner.

It’s unlikely that the same manufacturer produced all of these instruments, so pinpointing which of Tonk’s partners made our specific, well-loved museum horn remains an uphill climb we’ve sadly yet to complete.

[Tonk became an exclusive dealer of Washburn guitars after acquiring the Lyon & Healy merch department in 1928. Pictured is bluesman “Blind” Willie McTell, playing a Tonk 12-string, likely manufactured by Chicago’s Regal Musical Instrument Co.]

IV. The Tonk Legacy

There remains no smoking-gun evidence to directly connect the origin of the word “honky-tonk” with the products of the three Tonk family businesses, but it remains a pretty decent theory. Of course, back in 1893, one Kansas newspaper editor offered a different account: “When a particularly vicious and low grade theater opens up in an Oklahoma town they call it a ‘honky-tonk.’ The name didn’t ‘come from’ anything; it just growed.”

Whether the Tonk brothers can claim that bit of linguistic history or not, it should be clear by now that their surname was far from obscure in the 20th century. Along with the reputation already attached to their pianos, piano stools, and general wholesale music catalogs, the family continued to find success under the leadership of its second generation.

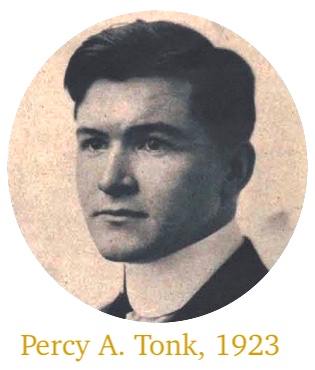

After the death of Max Tonk in 1914, the presidency of the Tonk MFG Co. was swiftly passed down to his 25 year-old son Percy Tonk, who, “although he is a but a young man, has had a very considerable experience in the business,” the Music Trade Review reported.

After the death of Max Tonk in 1914, the presidency of the Tonk MFG Co. was swiftly passed down to his 25 year-old son Percy Tonk, who, “although he is a but a young man, has had a very considerable experience in the business,” the Music Trade Review reported.

In fact, Percy hadn’t just trained in every department of his dad’s factory, he’d also developed a wisdom about the industry that Max himself might have been struggling to maintain in his later years. Percy recognized that (a) larger, storage-friendly piano benches were now in greater demand than stools, and (b) most piano dealers had begun bundling benches with the instrument itself, making it less necessary to appeal directly to the consumer market, or to develop dozens of different designs.

From 1915 onward, Percy Tonk standardized and simplified the operations at the old Clybourn Avenue plant, buying ready-cut wood stock rather than bothering with cutting up lumber or the expenses of kiln drying. This put less demand on the 60 men working in the factory, and paid off in profits for the company.

By Christmas of 1918, Percy Tonk’s fourth year as president, the Music Trades reported that “the shipping room of the Tonk Manufacturing Co., bench manufacturers, is one of the busiest places in Chicago just now.”

“The trade has been growing steadily ever since the summer,” Percy explained at the time. “The better grades of benches are especially in demand, and judging from our rush orders, the dealers of the country must be doing the biggest business of their careers.”

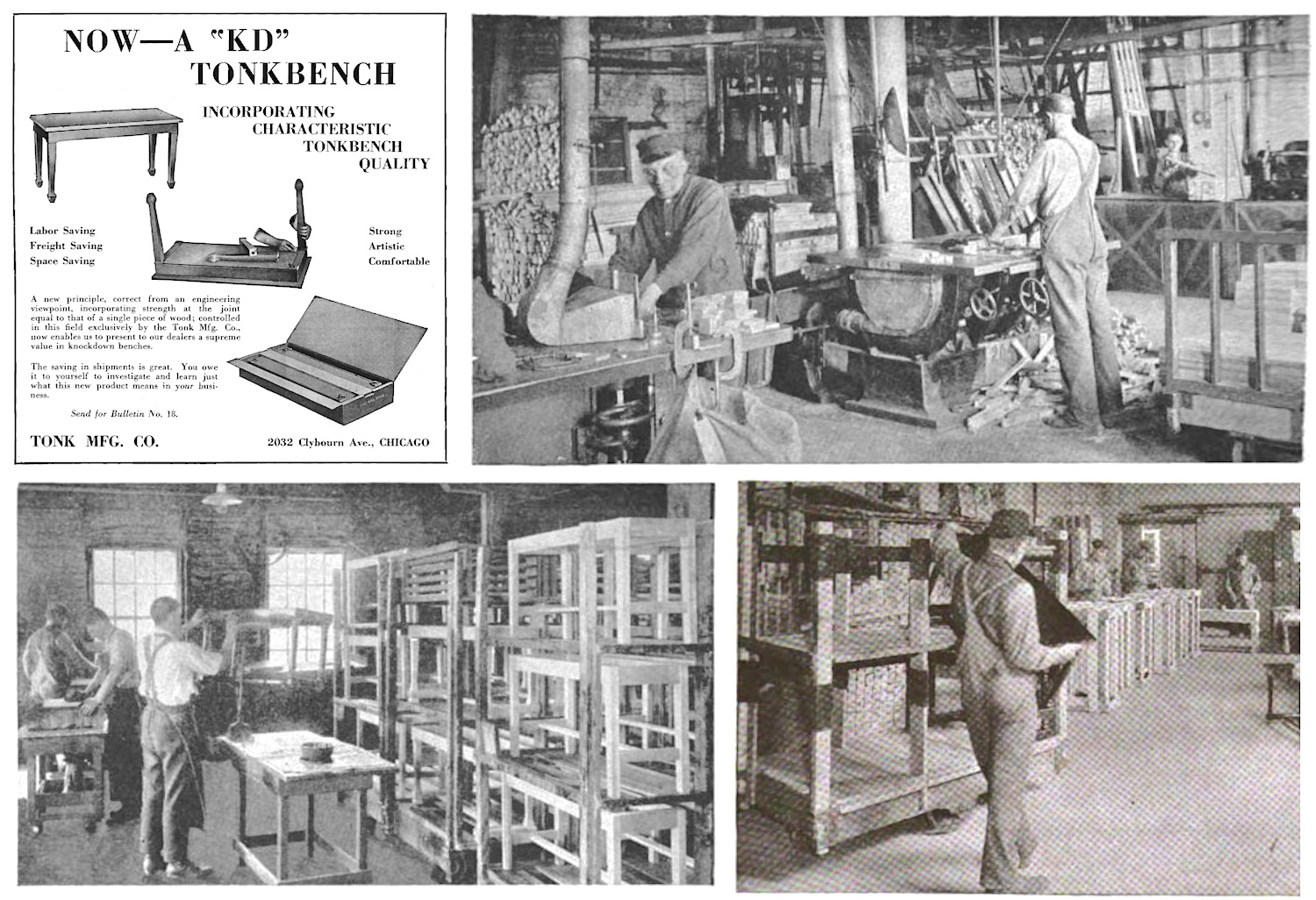

[Views inside Tonk’s Clybourn Avenue factory, 1925. Top Right: Pre-dried wood stock is cut to size. Bottom Left: Standardized bench designs help with efficiency. Bottom Right: Shipping crates are also standardized in two styles and made from ready-cut wood stock]

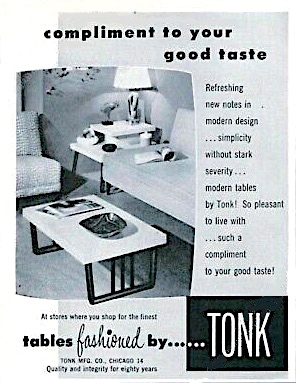

The Tonk MFG Co. remained a leader in piano benches through the 1920s, opening a second factory in Los Angeles, and continued in business into the 1960s, having shifted into more general mid-century modern household furniture, such as coffee tables and revolving cocktail tables (some designed by C. E. Waltman of Chicago).

During the 1940s and ‘50s, Percy’s daughter Doris A. Tonk was one of the company’s leading sales reps—a rarity for women in the furniture business at the time—and his son Hampton Tonk later took over the presidency through the company’s final years.

During the 1940s and ‘50s, Percy’s daughter Doris A. Tonk was one of the company’s leading sales reps—a rarity for women in the furniture business at the time—and his son Hampton Tonk later took over the presidency through the company’s final years.

***

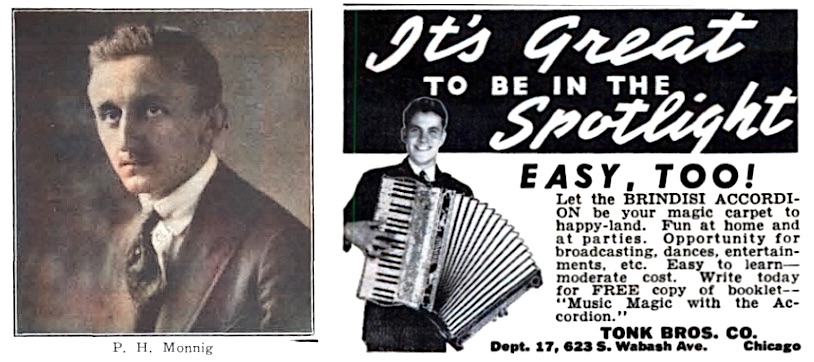

The Tonk Brothers wholesale music company, similarly, wasn’t derailed by the unexpected death of Charles Tonk in 1918. With younger brother Albert having already moved to California to become a fruit farmer—and with William still in New York—leadership of Tonk Bros. briefly fell to Charles’ widow, Sarah Tonk. Former treasurer Paul H. Monnig was then elected president in the early 1920s and served capably in the role for the next three decades. This included the negotiation of Tonk’s stunning acquisition of Lyon & Healy just before the stock market crash of 1929.

During the Depression, Tonk Bros.—now headquartered in the Brunswick Building at 623 South Wabash Ave— remained one of the largest musical merchandise houses in America, supplying orchestras, high school marching bands, and everything in between.

“The progress of this company,” read the 1937 Tonk Bros. catalog, “may be traced to a policy laid down by Charles J. Tonk nearly half a century ago: Carefully selected merchandise of established quality—fairly priced—promptly delivered—and sold on a basis of fair play to the retailer.”

[Left: Tonk Bros. president Paul H. Monnig, a German immigrant who took the position in 1924 and held it into the 1950s. Right: 1939 Tonk Bros. ad for the Brindisi Accordion]

We weren’t able to determine when the Tonk Brothers Company published its final catalog, but their share of the national marketplace clearly began to shrink by the Second World War, and by 1950, the company appears to have fallen into the stable of the Indiana music house, C. G. Conn, Ltd.

Paul Monnig, who died in 1972, was still listed as president of the firm into the late 1950s, maintaining an office in one room at 14 E. Jackson Blvd. The exact circumstances of the company’s final demise are unclear.

The same goes for the old New York piano business of Wm. Tonk & Bro., which also appears to fade out of existence gradually around the time of WWII. Patriarch William Tonk, who was kind enough to help us out by writing his Memoirs of a Manufacturer in the early 1920s, retired to upstate New York and died in 1934 at the age of 86. His sons William H. and Edwin maintained the company’s Fifth Avenue office for some time afterward, but it seems likely that the business either folded or was absorbed into the Tonk Bros. organization in Chicago.

The same goes for the old New York piano business of Wm. Tonk & Bro., which also appears to fade out of existence gradually around the time of WWII. Patriarch William Tonk, who was kind enough to help us out by writing his Memoirs of a Manufacturer in the early 1920s, retired to upstate New York and died in 1934 at the age of 86. His sons William H. and Edwin maintained the company’s Fifth Avenue office for some time afterward, but it seems likely that the business either folded or was absorbed into the Tonk Bros. organization in Chicago.

With the Tonk name heading toward obscurity in the 1960s, it’s easier to understand why Louis Armstrong and his subsequent biographers often summed up the company as a forgettable relic of the past—an odd name on a busted-up trumpet. Hopefully, this hefty retrospective will help, in a tiny way, to set the record straight.

Sources:

Memoirs of a Manufacturer, by William Tonk, 1926

“Seaver, Tonk & Co.” – The Industrial Interests of Chicago, 1873

“Tonk Manufacturing Co.” – Chicago and Its Resources Twenty Years After, 1871-1891

“The Tonk Manufacturing Company” – Musical Instruments at the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1895

“A Chat with Chas. J. Tonk” – Music Trade Review, March 17, 1900

“A House with Progressive Ideals” – Music Trade Review, Nov 5, 1910

“Forty Years in the Piano Stool Business” – Music Trade Review, Dec 6, 1913

“Pioneer in Business as Well as Location” – Music Trade Review, June 6, 1914

“Max Tonk Dead” – Music Trade Review, Aug 22, 1914

“Percy A. Tonk New Head of Tonk Manufacturing Co.” – Music Trade Review, Feb 13, 1915

“Charles J. Tonk Dies Suddenly” – Music Trade Review, March 2, 1918

“Bench Sales Show Big Piano Sales” – The Music Trades, Dec 14, 1918

“Tonk Bros. to Handle Sterling Line” – The Music Trades, March 22, 1919

“Violin Makes Big Strides in Popularity” – The Music Trades, Dec 17, 1921

“Evolution of the Piano Bench” – Presto, Dec 15, 1923

“A Four Years’ Experience with Dimension Stock” – Wood Working Industries, Jan 1925

“Eastern Firm Builds Plant” – Los Angeles Times, June 14, 1925

“New Tonk Bros. Catalog a Most Interesting Volume” – Music Trade Review, Nov 13, 1926

“Tonk Purchases Musical Merchandise Department of Lyon & Healy, Chicago” – Music Trade Review, July 28, 1928

Tonk Bros. Catalogs: 1930, 1937

“Cupids Recall Gay Past” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 24, 1961

Louis Armstrong: A Self Portrait, by Richard Meryman, 1971

“Retailer, Sales Representative Doris A. Tonk” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 7, 1990

Tonk timeline – Horn-u-Copia-net

I just purchased a Tonk Bench. For some time I have been looking for a bench for my sewing room. At a thrift shop, I found it.

The craftsmanship caught me eye at first but the quality is so obvious I could not believe my eyes.

I think it’s been reupholstered as it is not fabric seatcovering.

I have a coffee table, 1930’s, Louis XVI, inlaid mahogony.

Stamped on the underside- French Galleries by Tonk.

Cant find any catalogs or information at all,

is there any out there?

Interesting history. My grandfather and dad were trumpet players. I don’t have the instruments, but I found a 6 inch ruler in an old trunk, perfect condition with Tonk Bros. Co. Brunswick Building Chicago, Everything Musical written on it. Curiously led me to your website.

How would I find the value of my Tonk Piano (William Tonk & Bros New York)? I Checked serial # and it says it was made in 1914.

Thank you,

Jerline Martinez

jerline.martinez@gmail.com

Hi I recently bought a 40 key upright tonknnew york piano. The inside board reads 1895. I was wondering where one may find the Toni catalogues so I can learn more about this piano. It is red with pagoda illustrations on the front and side. Thanks

I can see how that there could have been an expression that to play a Tonk piano was to “honk a Tonk” which with usage became honky-tonk. The online dictionary lists no other meaning for the word tonk than a type of rummy card game so to me it seems almost certain that this was the origin of the term honky-tonk.

I have a swivel piano stool with the diamond shaped paper Tonk Trade Mark Warranted stamp on the bottom of the wooden seat. The top is red velvet. The iron plate says New York Tonk Chicago. The base is wood with 3 iron feet. I am wondering how I go about estimating the age and value. Thank you

I found my way here after reading an excerpt from a Life Magazine interview with Louis Armstrong. He said that the first trumpet / Cornet he bought was a Tonk Bothers Cornet.

“Armstrong’s memory appears so vivid that he even recalled the name of the obscure company who made the horn: “It was a Tonk Brothers — ain’t never heard of them.”[15] He then goes on to tell of how his mentor, Joe “King” Oliver got so sick of looking at the beat up Tonk Brothers horn that he gave Armstrong his old York model Cornet.”

That’s a great bit of info and I’ll definitely include it when I get a complete Tonk history written up. Thanks!