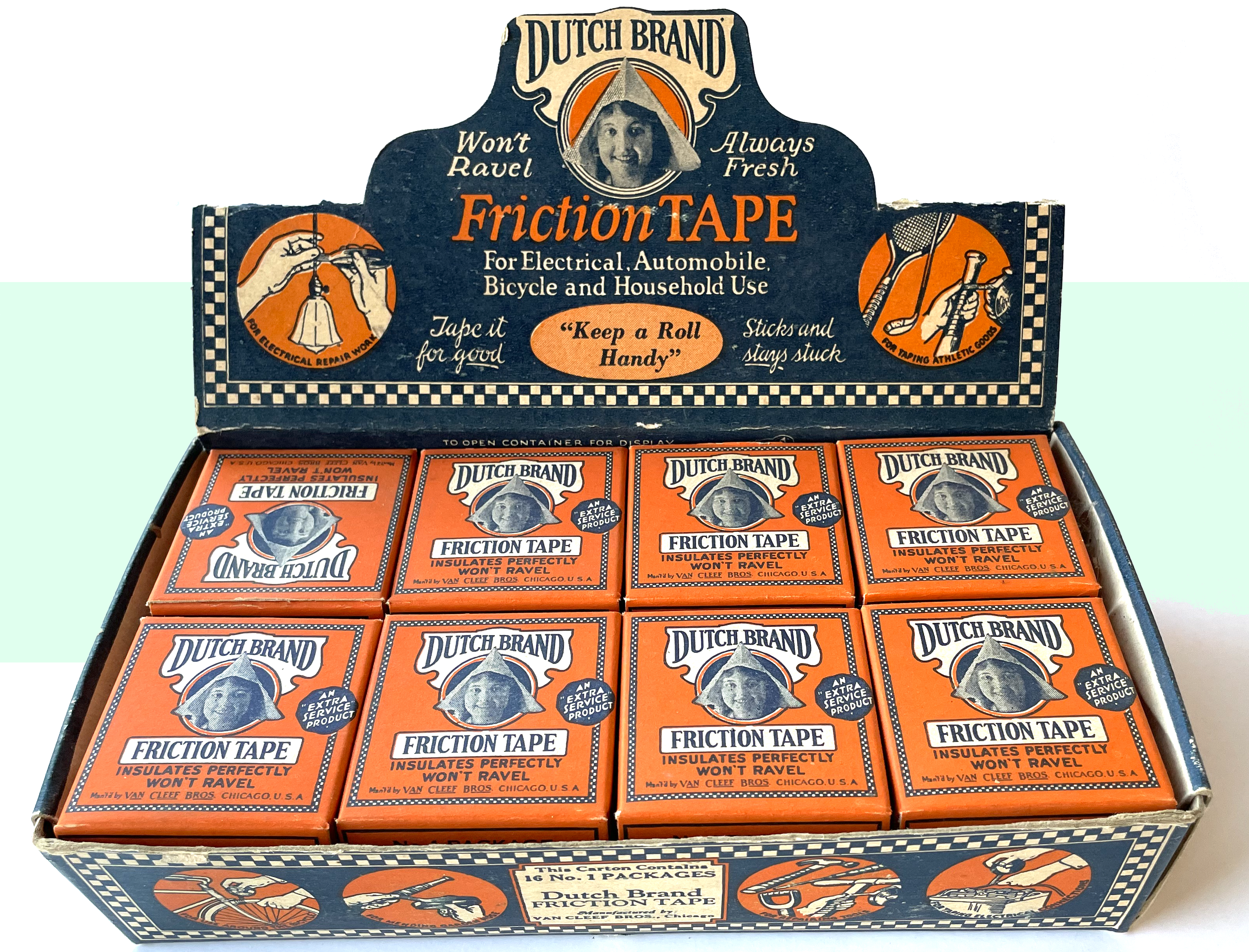

Museum Artifact: Dutch Brand Friction Tape Counter Display and Dutch Brand Grinding Compound, c. 1920s

Made By: Van Cleef Bros., Inc., 7800 Woodlawn Ave, Chicago, IL [Greater Grand Crossing]

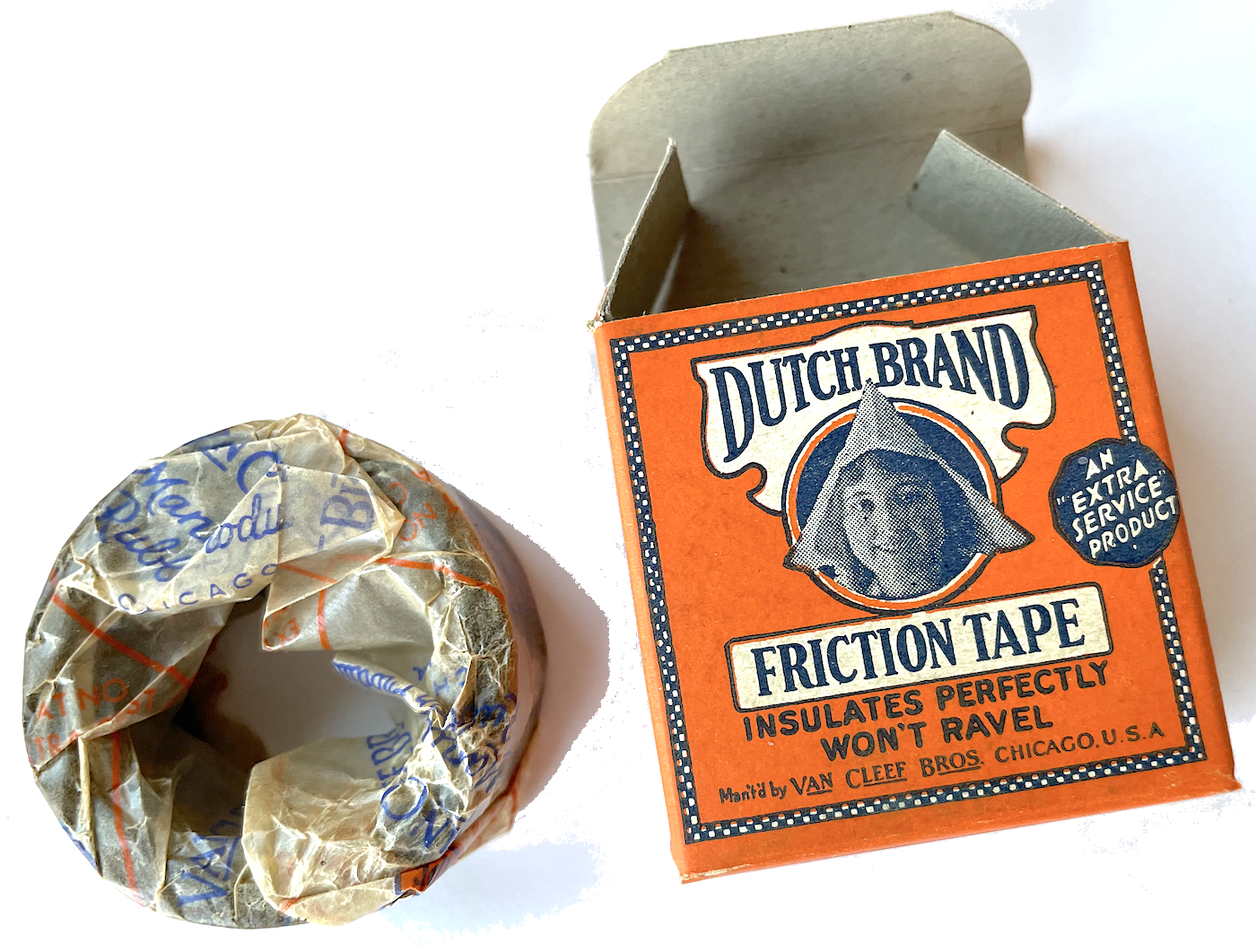

“This orange and blue package on a dealer’s counter will remind you to buy this useful little servant, DUTCH BRAND Friction Tape. Use it for automobiles, bicycles and electrical work; for home, store or shop; for mending tools, furniture, garden hose or anything else that’s broken . . . Tape it for good with Dutch Brand!” —Van Cleef Bros. advertisement, 1923

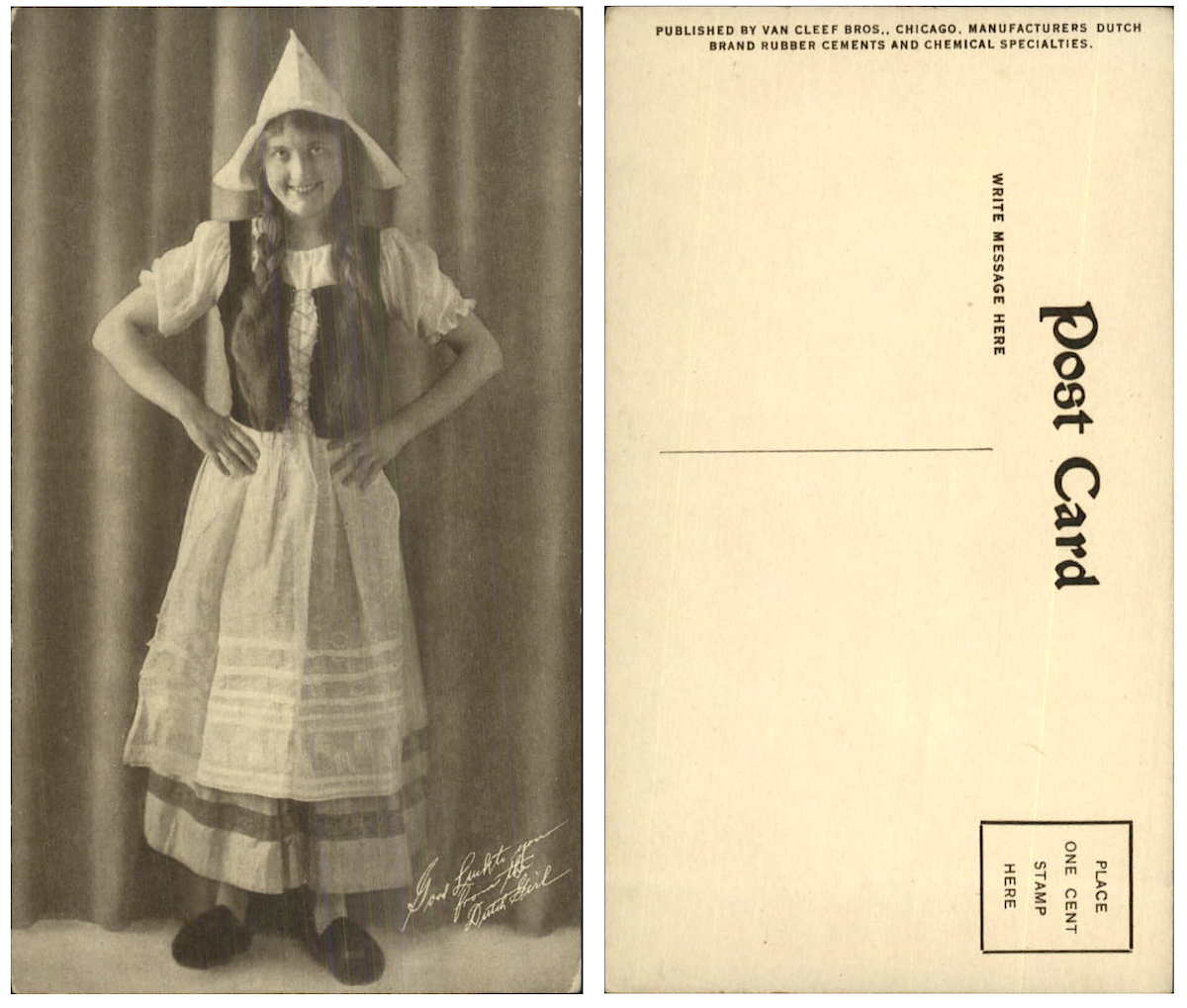

The label might say “Dutch Brand,” but the men behind this popular line of yesteryear adhesives were, in fact, five American siblings, born and raised on the South Side of Chicago. To confuse the matter slightly more, their father was actually a Belgian-born immigrant, and their mother came over from Prague. But thanks to some Holland-based heritage further back in the family tree—and a surname to match—the Van Cleef Brothers were accepted into Chicago’s small but tight-knit Dutch community, and ultimately selected a traditional “Dutch girl” inspired trademark when they launched their business in 1910.

The label might say “Dutch Brand,” but the men behind this popular line of yesteryear adhesives were, in fact, five American siblings, born and raised on the South Side of Chicago. To confuse the matter slightly more, their father was actually a Belgian-born immigrant, and their mother came over from Prague. But thanks to some Holland-based heritage further back in the family tree—and a surname to match—the Van Cleef Brothers were accepted into Chicago’s small but tight-knit Dutch community, and ultimately selected a traditional “Dutch girl” inspired trademark when they launched their business in 1910.

The logo went through several iterations (and faces), but the sight of Dutch Brand products would remain familiar to a large swath of the public for over 50 years, as Van Cleef Bros. parlayed its original specialty—rubber cement—into a diverse line-up of chemical goods and sealants found routinely in auto garages, hardware stores, shoe dealers, millinery workshops, and radio shacks. In the 1920s, visitors to those establishments may well have seen the colorful display box of Dutch Brand Friction Tape in our museum collection; which was specifically designed for quick-grab impulse buys off the countertop.

As noted in the ad copy at the top of this page, these pocket-sized “No. 1” rolls were offered up as reliable solutions for all sorts of day-to-day fix-up jobs. A precursor to plastic electrical tape, the design featured a core fabric strip with four layers of rubber around it, creating “tighter adhesion and insulating strength far greater than the usual two or three coat tapes.”

The Van Cleefs weren’t unique in trying to capitalize on the rubber boom of the early 20th century, but unlike a lot of their peers, ambition never seemed to get in the way of their ethics. The brothers were dedicated to science, obsessed with safety, progressive in their treatment of workers, and far more outspoken about “the betterment of humanity” than they were about market shares or revenues. Crazier still, they managed to run a business together while maintaining some semblance of family harmony.

“No better illustration of the value of working together has come to our notice than in the organization and development of Van Cleef Brothers, manufacturers of automobile chemicals and rubber cements with their main factory at Chicago, Illinois,” Hardware World magazine reported in 1920. “[Their history] proves the value of cooperation and disproves the old theory that too many cooks spoil the broth and too many relatives injure an enterprise.”

History of Van Cleef Bros., Part I: Meet the Van Cleefs!

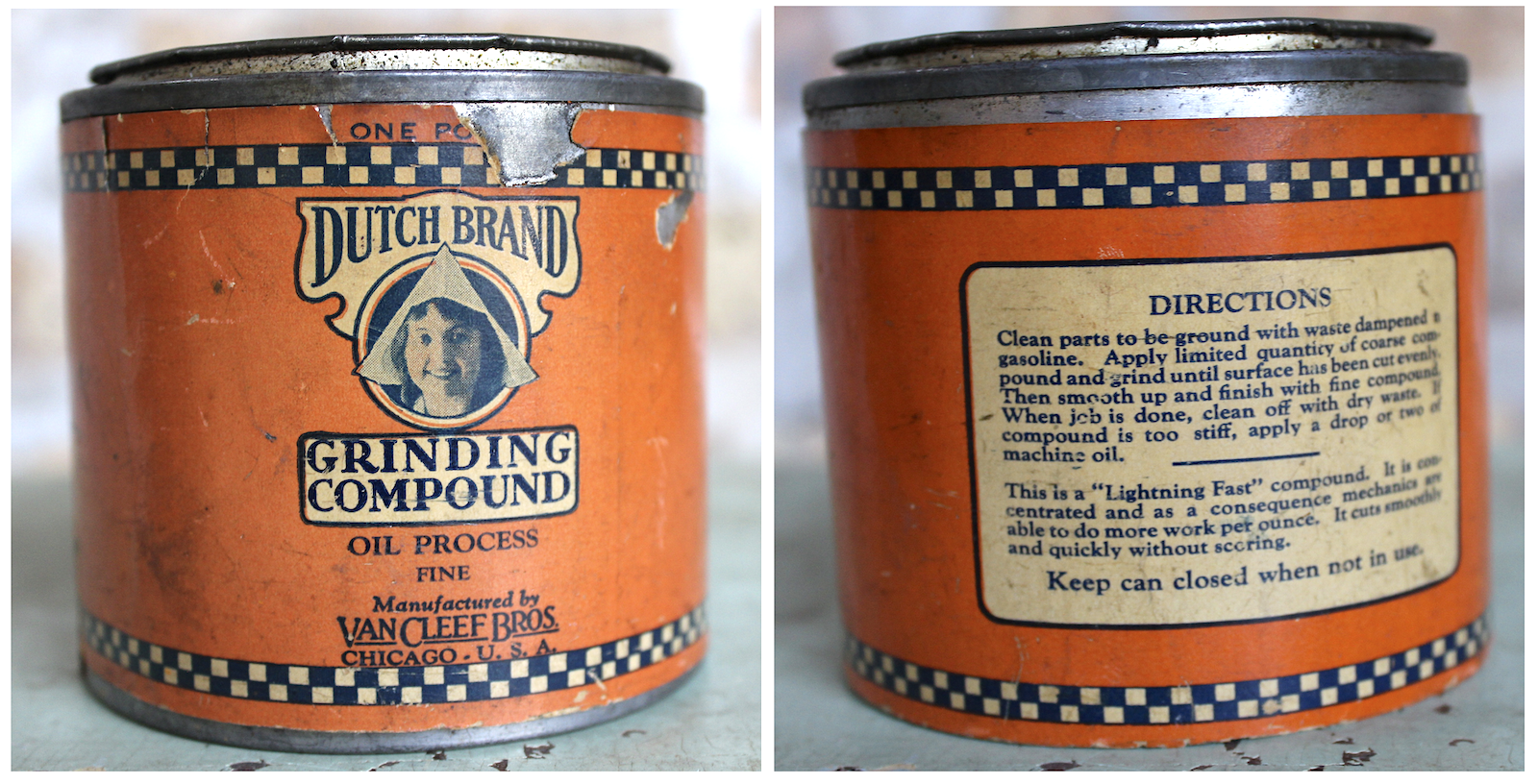

In 2015, while browsing the “going-out-of-business sale” of the old Riverside Cafe in Bucktown, I stumbled upon a small, sturdy can of Dutch Brand “Grinding Compound” sitting conspicuously on a dusty shelf. The weathered paper label, circa 1920s or ’30s, was still an eye-catching orange with blue-and-white checkerboard stripes and the smiling Dutch girl logo (Version 2.0) center-facing, her three-cornered hat poking out from a circular blue backdrop. That was my introduction to Van Cleef Bros. as a Chicago enterprise, though I’d soon learn that the demise of the original business had preceded that of the Riverside Cafe by about 70 years.

The good news was, the Van Cleefs themselves had not faded beyond the reach of research, and in fact, some aspects of their personalties and overarching philosophy had been preserved with rare depth and specificity. In particular, through info provided in trade magazines and the brothers’ very own self-published “Butterfly Association” newsletter, it became clear that there was a surprising poetical and political passion lurking behind this unassuming can of grinding compound.

So, to properly do the Van Cleefs justice, and to pay tribute to their distinct joie de vivre (or “levensvreugde” in Dutch), I will now introduce each of the five brothers not in the style of a biographical dictionary, but as if I were describing the members of the Jackson 5 in Teen Beat magazine:

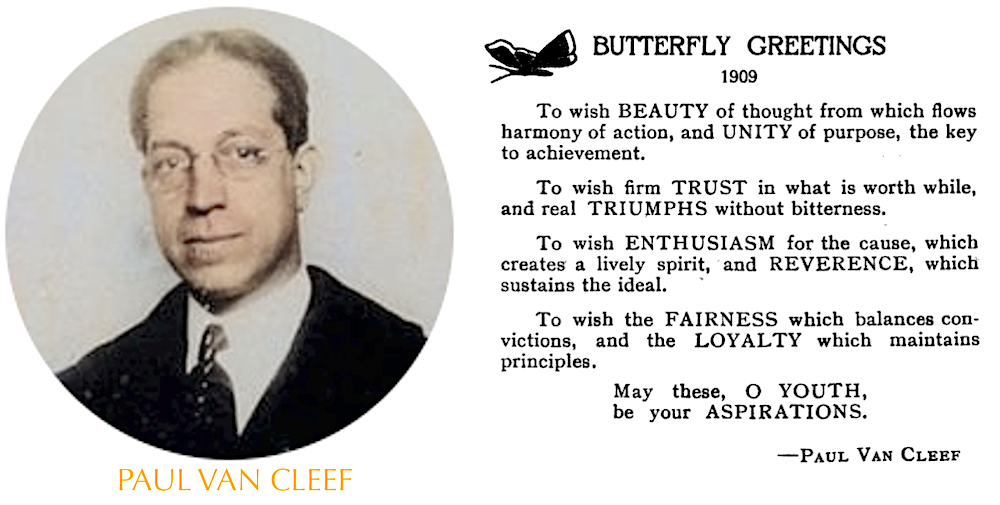

Heeeerrres PAUL!

Hey girls, this is Paul—the brains of the operation. Not only is this University of Chicago grad the top chemist and factory manager at the Van Cleef Bros. company, he’s also widely credited as one of the key innovators of rubber cement in the 20th century. That’s right, Paul here developed an awesome combo of latex polymers and acetone that helped give us one of the world’s most dependable and flexible dry adhesives. And he accomplished the feat while still in his mid 20s. Oh, did we mention he’s a poet, too?

Heeerrrees FELIX!

Heeerrrees FELIX!

He’s a former linen salesman who selflessly poured all his resources into helping brother Paul get that rubber cement business off the ground. Felix lived in New York for a while and has “traveled extensively in America and Europe,” giving him a “cosmopolitan interest in most all social work.” What a fellow!

Heeeerrees MAXIME!

Don’t be fooled by the name! It’s another boy! Brother Max used to sell linens with Felix, but when he heard about Paul’s rubber cement dreams, he hopped on board with enthusiasm. Maxime says, “I’m interested in practical social work, especially the elimination of selfishness.” From what we’re seeing, Max, mission accomplished!

Heeerrrrees NOAH!

Like a guy who takes charge? Meet big brother Noah! He’s the Executive Manager of Van Cleef Bros. His interests include the “elimination of graft in politics and business.” He’s also an “active member of several lodges and various associations.” Bet you’d like to lodge up with him, eh?

And finally, it’s EUGENE! [not pictured / too attractive?]

He might just be the “assistant” to his brother Noah (as of 1920, anyway), but Eugene ain’t no black sheep! A former teacher at the University of Chicago and commercial geographer at Rand McNally, Eugene is just as saintly in purpose as the rest of the Van Cleef crew. “I’m interested in increased advantages that may be afforded the mass of people.” The mass of people, girls. That means you! [Note: Eugene became a professor of geography at Ohio State and did not take part in the family business going forward].

[The Van Cleef sales team at the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair. On the far right, pointing, is Felix Van Cleef. Fourth from the right, standing in back and wearing a gray fedora, is Paul Van Cleef. Second from the left (not counting the partial view of one man) in a gray fedora and wearing gloves is Noah Van Cleef. Max Van Cleef does not seem to be in the photo.]

Anyway, all pageantry aside, it’s easy to ascertain that the Van Cleef boys were social activists of a sort even before they found success in the rubber business. The Butterfly Association, to which all five brothers belonged, was based in Chicago but counted members across the country and some internationally. Its purpose was the “encouragement of all that is good and beautiful,” and each Van Cleef took turns holding meetings and penning editorials for the group, starting from 1907 on. They tackled subjects as diverse as forest conservation, the importance of sincerity in salesmanship, the controversy over dancing in schools, and some other heavy issues—often with a progressive but slightly square-jawed approach.

“It has been said that ‘The world owes every man something.’ This is a fallacy,” Maxime wrote in Vol. 2 of the Butterfly newsletter. “The world owes us nothing. Only as we put forth our best efforts do we receive returns. It behooves us, therefore, to put something conscientious into this life, and in accordance with it is ‘What we get out of life.’”

As the sons of an immigrant father who scratched out a living as a saloon keeper and salesman, the Van Cleefs weren’t just taught about the importance of a good work ethic, they saw it in action. Paul Van Cleef took these lessons of perseverance to heart when his own career hit a snag in his early 30s. As an out-of-work chemist, he made a bold play to “work on a rubber cement that had been an idle fancy of his for some time.” Max and Felix, the linen salesmen, supported the effort by cobbling together $500 in capital for their brother Paul’s pursuit, and the new enterprise was on its way.

As the sons of an immigrant father who scratched out a living as a saloon keeper and salesman, the Van Cleefs weren’t just taught about the importance of a good work ethic, they saw it in action. Paul Van Cleef took these lessons of perseverance to heart when his own career hit a snag in his early 30s. As an out-of-work chemist, he made a bold play to “work on a rubber cement that had been an idle fancy of his for some time.” Max and Felix, the linen salesmen, supported the effort by cobbling together $500 in capital for their brother Paul’s pursuit, and the new enterprise was on its way.

By 1912, after just a couple years in business, Van Cleef Bros. had already acquired a good factory space on a large chunk of Woodlawn Avenue in Greater Grand Crossing, from 77th to 78th streets. While expansions and additions would follow, this would remain the company headquarters for the rest of its existence, and would continue to produce Dutch Brand products, under different ownership, through the 1960s. The building has since been demolished, with residential housing in its place.

The company primarily marketed itself to the auto, bicycle, and motorcycle markets in its early years, and grew right alongside the rise of the Model T. In the 1910s and ’20s, drivers would carry a can of rubber cement with them as a means of patching tire punctures on the roadside. There were quite a few companies producing the stuff, but Van Cleef Bros., ever ethical, didn’t use “junk rubber” like a lot of their competitors. Instead, they sourced their stock from Brazilian plantations and shipped them to Chicago in “biscuit shaped masses,” which were then soaked in vats, macerated and rolled in machines, hung in drying rooms for 2 months, then combined with a mix of chemicals (including benzol) to give it the proper consistency and adhesiveness.

“Making rubber cement is much like the work of a blast furnace,” Motor Age magazine reported after visiting the Van Cleef factory in 1916. “Once a mixture is in the drums where it is stirred and dissolved it must be given constant care, and the Van Cleef factory works night and day.”

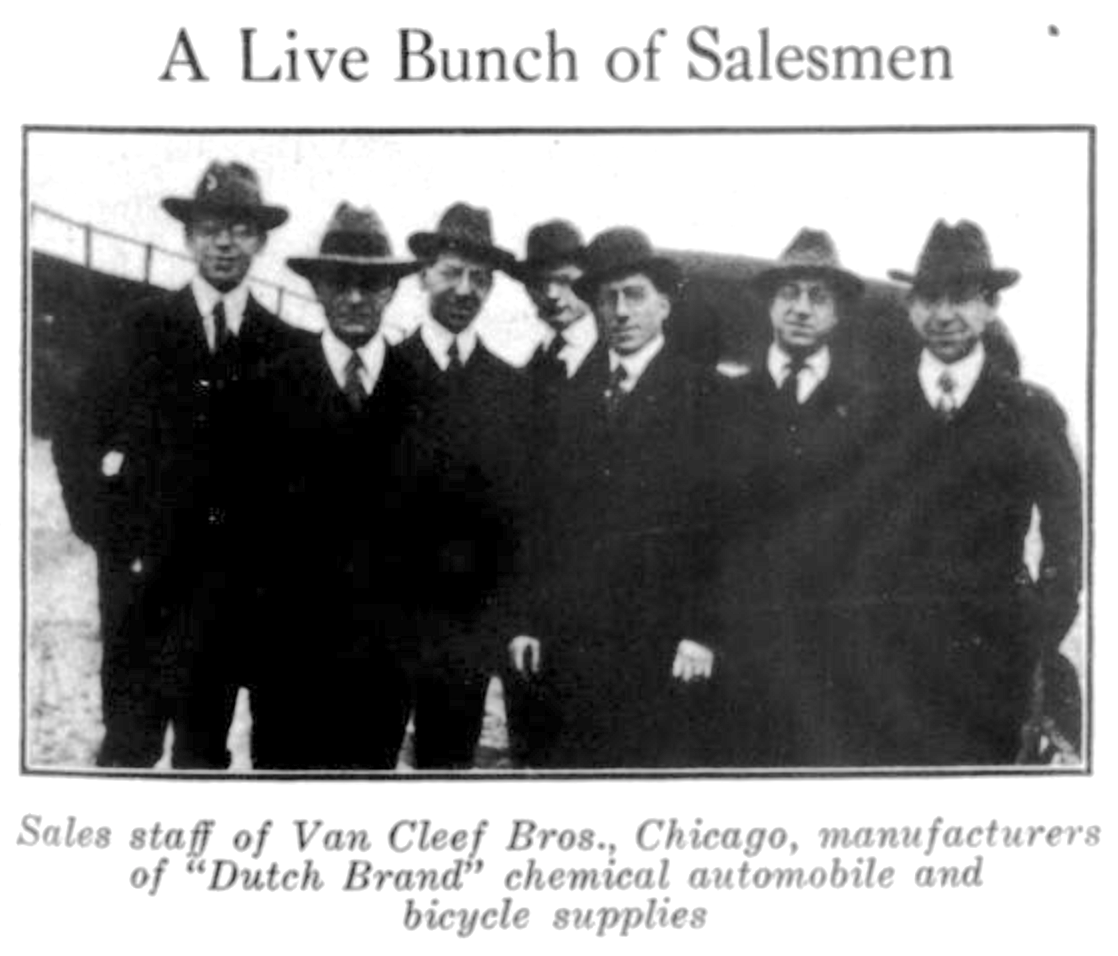

[Above: Van Cleef ads, 1917, appealing uniquely to both the motor and millinery trades. Below: A look at the Van Cleef sales team in 1918: “A Live Bunch of Salesmen” as described in Hardware Age]

Soon enough, Paul Van Cleef built up a prolific laboratory aimed at adapting his adhesives and solutions for a range other convenient uses, from repairing shoes to decorating hats; the company’s “Snow White Millinery Cement,” for example, was much quicker and just as effective as sewing, saving the country’s thousands of hat-makers from early onset arthritis.

“The Van Cleef line has become nationally famous in several trades,” Hardware World noted in 1920. “It goes to the automobile industry, the bicycle industry, the shoe finding men, and the millinery trade. The line includes all manner of rubber cements and compounds, automobile chemicals for valve grinding, radiator repair liquids, paints, enamels, lubricants, tape—a complete assortment and one that is known and accepted as standard in the trade.”

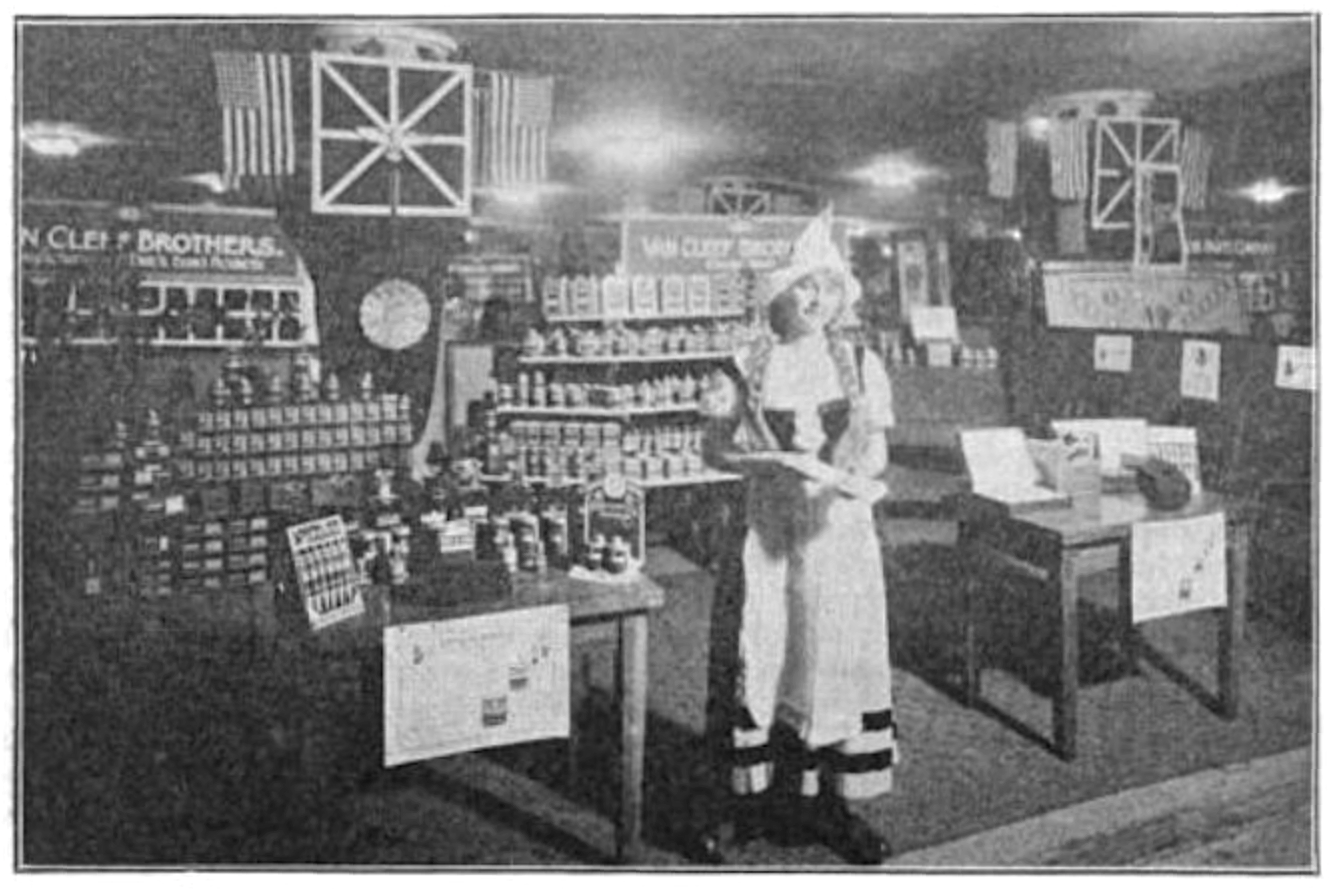

[A woman portraying the “Dutch Girl” in the Van Cleef Brothers display both at the 1919 convention of the Automotive Equipment Association, held at Chicago’s Medinah Temple.]

Part II: A Record in Safety

“In a period when disaffection between management and labor is so tragically serious, it is refreshing that there are plants like that of Van Cleef Bros., wherein the relationship of working force and executive staff is one of extreme kindly regard toward one another. All industry can absorb a lesson from the experience of this local plant.” – The Daily Calumet, July 21, 1945

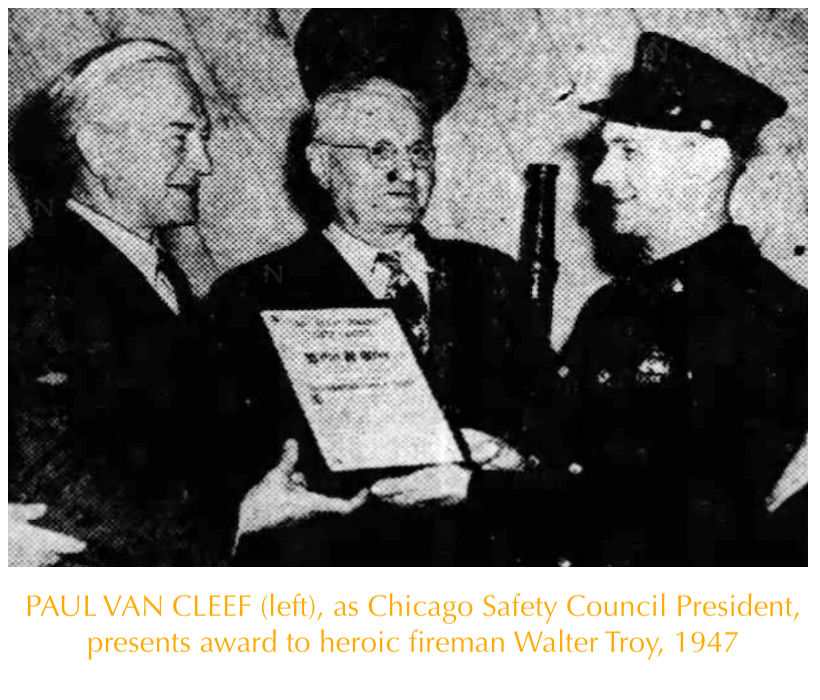

Working in a rubber factory was understood to be a job fraught with peril in the early 20th century; there were dangerous chemicals, heavy machinery, plenty of opportunity for industrial mishaps. Under the watch of the methodical and obsessively responsible Van Cleef brothers, though, these matters were taken a tad more seriously. Paul Van Cleef, in particular, was decades ahead of his time when it came to implementing safety standards; not just in his role as factory chief, but in his parallel duties as a leader of the Greater Chicago Safety Council (which, among other things, helped usher in laws requiring driver’s licenses in the 1920s).

Unsurprisingly, under Paul’s watch, the plant on Woodlawn Avenue soon developed a reputation for sterling factory-inspector reports and employee safety records.

In January of 1923, one worker missed a few days after an on-the-job injury. For the next 18 years, this never happened again.

“A record in safety has been set by the Van Cleef Brothers employes in the rubber products plant, 7800 Woodlawn Avenue,” The Daily Calumet newspaper reported on April 8, 1941. “Record shows 3,000 days without a lost-time accident, which for a plant of this size is an all-time record in the United States.”

At the time, president Noah Van Cleef remarked that, “The spirit of the men had much to do with making this record. On several occasions there were accidents where the individual could have stayed at home, but he refused to be a part in breaking the long time record. Out slogan is ‘Co-operation is Our Obligation.'”

[Top and Left: 1941 news headline from the Daily Calumet, noting 3,000 straight days without a work day lost to accident at the Van Cleef factory. Right: 1930s advertisements for Dutch Brand Friction Tape and the lesser known “Twintak” adhesive tape.]

That kind of rigid expectation would certainly be frowned upon today, but Van Cleef workers didn’t seem to feel overly oppressed by the demand for perfect attendance. Around the same time that their streak had begun, early in 1923, several members of the factory’s tape manufacturing department had organized a “safety and social club,” which played an equally big role in accident avoidance at the plant. The workers also created teams in bowling, basketball, softball, and roller skating, which competed against other clubs in the South Shore Y-Industrial League, further building a sense of camaraderie within the plant.

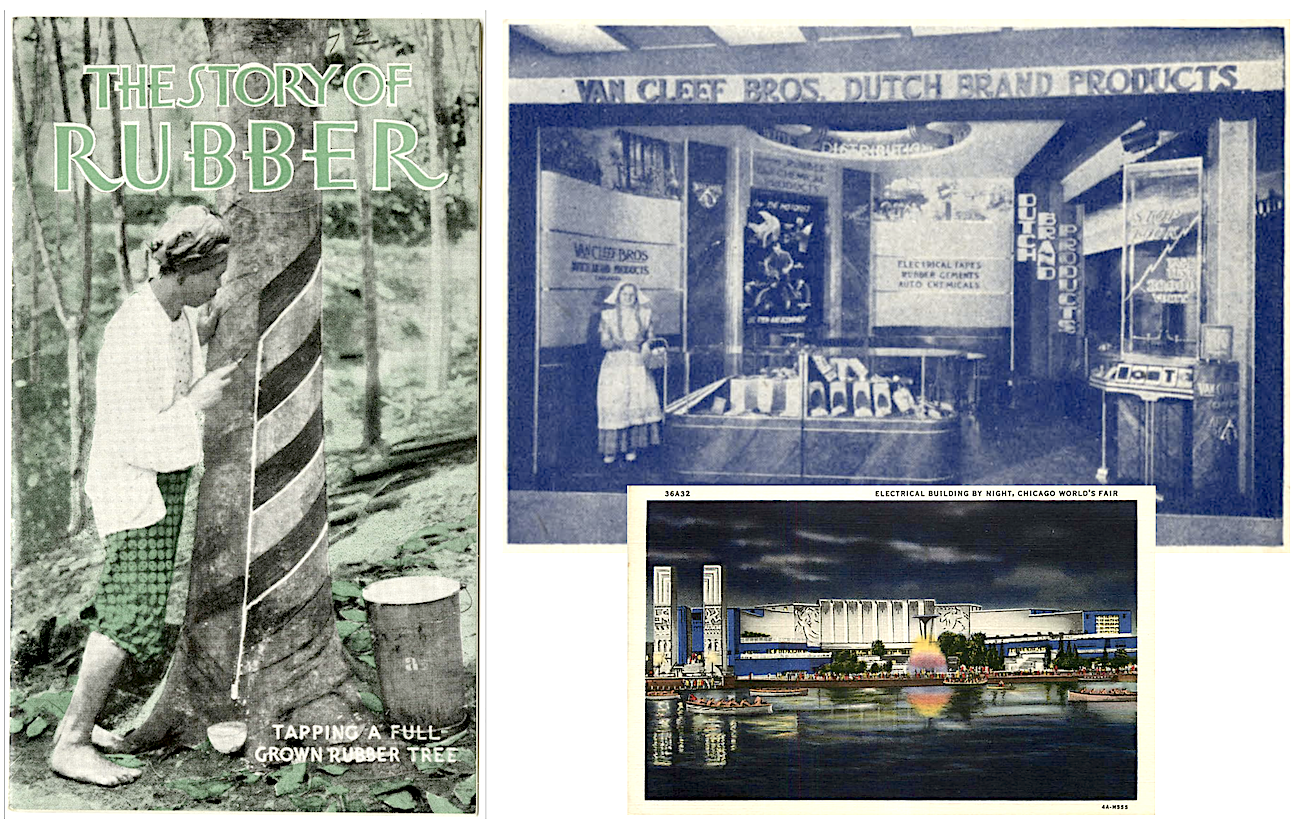

Even during the rough times of the 1930s, Van Cleef Bros. maintained an optimistic outlook that rubbed off on its employees. The firm maintained a steady sales and promotions budget in expectation of better times, and during the “Century of Progress” World’s Fair in Chicago, they invested in a large exhibit inside the Electrical Building; with the obligatory “Dutch Girl” greeter on site, handing out free gifts to visitors, including a roll of Dutch Brand Friction Tape and a promotional pamphlet called “The Story of Rubber.” Around the same time, a factory expansion was announced for the Woodlawn Avenue plant, which included not only new machinery, but rest rooms, locker rooms, and showers for the improved comfort of workers.

[Left: “The Story of Rubber” pamphlet handed out by Van Cleef at the 1933-34 Century of Progress. Upper Right: The Van Cleef exhibit inside the Electrical Building. Bottom Right: Exterior view of the Electrical Building]

As the best proof of the general feelings of the factory employees towards management, the roughly 275 person workforce at Van Cleef Bros. took the unusual step of presenting their own bosses with a bronze plaque in 1945; toward the end of several years of difficult wartime work. It was partially to mark the 35th anniversary of the business, but it was also a grand gesture reflecting the fact that, unlike so many other plants during the Depression and WWII, there were no strikes or stoppages at the Van Cleef plant, nor much in the way of seething animosity on either side.

“It is exceptional for any firm to remain uninterruptedly and successfully in business under the same management for 35 years,” Noah Van Cleef (by then about 70 years old) said when receiving the plaque from his employees, “and second, to have employees spontaneously and solely of their own accord, indicate in such an impressive way their high regard for the firm.

“There is bound to be a post-war period,” Noah continued, “and naturally everybody is anxious about its effect upon him. In our own specific case the post-war period has no terror for us. We shall not have to pause for any special preparation to enable us to proceed with making everything we produced in the pre-war period. Speaking for the firm, we shall continue to spare no effort to maintain, at all times, the wonderfully fine personal relations which exist between Van Cleef Bros and the entire staff, regardless of position held. So long as the present spirit of both firm and workers is maintained, we have nothing to fear for the future.”

Unfortunately, not even a positive spirit can out-duel Father Time. Just two years after the end of the war, in December of 1947, the Van Cleef Brothers—all now well into retirement age—opted to sell their business to the Johns-Manville Corporation out of New York. There were caveats: Van Cleef Bros., Inc. would become a wholly owned subsidiary of J-M, but its Chicago factory would carry on with the same management and continued oversight from the founders.

The arrangement worked out for a while. Johns-Manville revamped the Dutch Brand line over the next decade and continued producing many of the established Van Cleef goods with occasional tweaks as technology evolved. When longtime Van Cleef employees were inducted into the company’s “25-Year Club,” representatives from Johns-Manville would often travel to Chicago to give their kudos, as well.

[Above: Group photo of the inaugural class of the “Quarter Century Club” of employees at the Van Cleef plant in Chicago. While we can’t match names to the faces above, we do have a list of most of the honorees from the 1952 ceremony, which included: Felix, Paul, and Noah Van Cleef, Katy Kasehagen, Frank Aloe, Stanley F. Bentley, Frank Chonacki, William Dermott, James Drazba, John W. Duffas, Carl E. Frick, William F. Gereman, Edward Gordon, John Hoyne, Frank Illanich, Matthew Kasmir, Stanley Kracinski, Emma Lind, S. Stewart MacIntyre, Anne Mitchell, Roy C. Olson, Peter E. Pinta, Walter Polczynski, John B. Rago, Kathryn T. Sheehan, Joseph Sulski, Howard Weir, Ralph Wimmer, and John Wimmer.]

[Pamphlet for the Dutch Brand Products, now under Johns-Manville ownership, 1950s.]

Considering the Van Cleef brothers’ reputation for squeaky clean ethics, though, it became something of an irony that they’d ultimately put their future in the hands of a company, Johns-Manville, that made its fortune in the asbestos trade.

Years before purchasing Van Cleef Bros., executives at Johns-Manville were already aware of the proven connection between asbestos exposure and cancer, but they spent years (decades, in fact) downplaying or outright hiding the truth; mainly to avoid any liability for the illnesses of their own employees. By the time the company was finally taken to task through litigation in the early 1970s, they had already sold off their shrinking Dutch Brand division (formerly Van Cleef) to the Nashua Corp., an office products company. The Woodlawn Avenue plant in Chicago was acquired in the sale and remained in use as the “Dutch Brand division” of Nashua Corp. for a few years before its closure in the early 1980s. The Dutch Girl didn’t regenerate on this occasion.

Maxime (d. 1951), Noah (d. 1956), and Felix Van Cleef (d. 1963) didn’t live to see the rough demise of the reputable brand they’d built. Youngest brother Eugene died in 1973, just as the era was ending. As for Paul Van Cleef, the brilliant chemist, businessman, poet, and safety expert . . . he enjoyed his final years in Los Angeles, living to the ripe age of 96 and shuffling off the mortal coil in 1979. He was finally awarded the American Chemical Society’s Distinguished Service Award, posthumously, in 1982. Paul and his wife Jeanne are both buried in L.A.’s Westwood Memorial Park.

Maxime (d. 1951), Noah (d. 1956), and Felix Van Cleef (d. 1963) didn’t live to see the rough demise of the reputable brand they’d built. Youngest brother Eugene died in 1973, just as the era was ending. As for Paul Van Cleef, the brilliant chemist, businessman, poet, and safety expert . . . he enjoyed his final years in Los Angeles, living to the ripe age of 96 and shuffling off the mortal coil in 1979. He was finally awarded the American Chemical Society’s Distinguished Service Award, posthumously, in 1982. Paul and his wife Jeanne are both buried in L.A.’s Westwood Memorial Park.

We’ll leave the last word to Paul Van Cleef himself, speaking on the subject of ambition. Keep in mind, he wrote this piece in the Butterfly Association newsletter as a young man in his mid 20s, several years before launching his company and earning his own life’s fortune. Who knew the rubber cement guy could impart such wisdom?

AMBITION

by Paul Van Cleef, b. 1883, d. 1979

Do you know that Fahrenheit, who invented the thermometer named after him, was at first a merchant? Do you recall that Alvan Clark, renowned for his lens grinding, worked for nine years as a calico printer? Have you ever heard that Chatrian, the French writer, was a glass maker by trade? Do you remember that Oliver Wendell Holmes was eminent as a surgeon as well as a literateur? Did it ever appeal to you that most men are really designed by Nature to develop along specific lines? This tendency is unconsciously recognized by each individual when he feels within himself the desire to follow definite paths of work. This constitutes ambition.

To recognize within ourselves ability and powers, potential though they be, which are granted to us is not always an easy task; but sooner or later, in spite of ourselves, they will appear. The child, Mozart, displayed an unwonted talent at five years old as a musical composer. Landseer could not avoid exhibiting a precocity in art, even before he attended school, which surprised all beholders. But on the other hand, Hawthorne did not achieve success as a writer until he neared the age of forty five. Handel lost two years endeavoring out of filial respect to learn law. Instead music carried him into its dominion at last. Natural inclination is therefore the best guide for the field in which one’s activities should be focused.

An ambition cannot be tacked onto any man. This touches the cause for many failures in life. Many seek, while unfitted to do so, to emulate the example of others simply because the others have been successful, thereby hoping also to win success. One should strive to sound his soul, to discover the elements which are best adapted for a life’s work. These should guide the progress of one’s labors. Of course it is not always possible to cling to this idea. Environment checks careers. This is true to a certain extent. But look at John Mitchell, the labor leader—did he not work in the coal mines of Pennsylvania as a laborer? The strong men are those who rise above their environment. Be strong. The world is venal, too, some will assert. This is also true. But even here ambition may be satisfied. Rubens, at Antwerp, was a painter of vast canvases for wall and ceiling, because priest and prince demanded them, because he was a son of the church. On the contrary, Rembrandt, at Amsterdam, was a painter of easel pictures because Holland was Protestant, because it did not decorate its churches, because about the only thing it demanded of its painters was the portrait, the genre piece, or landscape. Nevertheless both followed Nature’s direction and became great among the artists of the world. Emerson found that he could not satisfy his conscience by remaining in the clergy, but he became a great and popular lecturer, and thus fulfilled the function for which Nature equipped him.

An ambition cannot be tacked onto any man. This touches the cause for many failures in life. Many seek, while unfitted to do so, to emulate the example of others simply because the others have been successful, thereby hoping also to win success. One should strive to sound his soul, to discover the elements which are best adapted for a life’s work. These should guide the progress of one’s labors. Of course it is not always possible to cling to this idea. Environment checks careers. This is true to a certain extent. But look at John Mitchell, the labor leader—did he not work in the coal mines of Pennsylvania as a laborer? The strong men are those who rise above their environment. Be strong. The world is venal, too, some will assert. This is also true. But even here ambition may be satisfied. Rubens, at Antwerp, was a painter of vast canvases for wall and ceiling, because priest and prince demanded them, because he was a son of the church. On the contrary, Rembrandt, at Amsterdam, was a painter of easel pictures because Holland was Protestant, because it did not decorate its churches, because about the only thing it demanded of its painters was the portrait, the genre piece, or landscape. Nevertheless both followed Nature’s direction and became great among the artists of the world. Emerson found that he could not satisfy his conscience by remaining in the clergy, but he became a great and popular lecturer, and thus fulfilled the function for which Nature equipped him.

A person is more likely, then, to become successful and to obtain greatness when he has recognized his own natural aptitudes, has cultivated them and utilized them before the world. The world observes talent, and generally favors it. But it always regards some of the commoner talents, like industry and temperance, highly, and these must be the accompaniments of talent. If one has ambition, he should be certain it is not founded on an imaginary fabric. He should assure himself of his foundation. He must prepare himself to develop, perhaps not swiftly, but surely, in the direction which he believes Nature appeared to intend him. Success must then be his, and ambition can thus only be satisfied. Let him commit as a watchword the words of the poet:

“Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul,

As the swift seasons roll!

Let each new temple, nobler than the last,

Shut thee from heaven with a dome more vast.

Till thou at length art free.

Leaving thine outgrown shell by life’s unresting sea”

(Oliver Wendell Holmes)

—Paul Van Cleef

Sources:

“How Rubber Cement is Made” – Motor Age, Nov 23, 1916

“Big Business Brought by Equipment Show” – Accessory and Garage Journal, Nov 1919

“Five Brothers Build an Industry” – Hardware World, August 1920

“Van Cleef Brothers Establishes New Lost-Time Accident Record” – The Daily Calumet, April 8, 1941

“Close Relations” – The Daily Calumet, July 21, 1945

“Johns-Manville Buys Van Cleef” – The Rubber Age, Dec 1947

“Van Cleef Div. of Johns-Manville Celebrates Founding Company’s 25-Year Club; Induct 30 Initial Members” – The Daily Calumet, July 15, 1952

“Nashua Firm to Acquire Dutch Brand” – Brattleboro Reformer, Jan 14, 1970

“Johns Manville Corporation History” – International Directory of Company Histories, Vol.64, 2004

Archived Reader Comments:

“This was this was a most enjoyable read, as have been the several other I have enjoyed.

While I research Chicago’s millinery history, the VanCleef adhesive caught my eye. Although my digging provided some personal aspects of Paul, the advertising for the glue is informative of the times.

Paul was so well established he had been Editor in Chief of the professional journal, Chemical, from 1920-1922. It was not until 1982 that Paul was awarded the American Chemical Society’s Distinguished Service Award.

The use of sewing has long been the method of choice for most millinery work. His glue, Snow White Millinery Cement, introduced the opportunity to cut down on the time spent on trimming a hat. They had hoped to broaden the use with the release of a booklet to publicize the cement. Millinery Without Sewing. Chicago: Van Cleef Bros., 1919.

“Advertising booklet produced by the manufacturers of Snow White Millinery Cement. Directions on how to cover frames with fabric, ribbon and feathers, and to make millinery ornaments using the product.” Their packaging had a catchphrase: Sticks and stays stuck. The booklet was advertised to be given free in the Illustrated Milliner 1916 in a full page.” –-Mary Robak

“Thank you so much for this amazing page. I didn’t know anything about my great-grand father (Paul Van Cleef) and his brothers. This is amazing” —Liz Liebman, 2016

“Liz, I just came across this website and saw your comment. I am Andy Schwarz and my mom was Jane Shamberg. She was the daughter of Hanna Ferst Einstein who had a sister, Ruth. Ruth was my great aunt and was married to Felix Van Cleef. He was an amazing human who we all adored.” —Andrew Schwarz, 2017

Thank you very much for this wonderful article. I rode the commuter train past the Van Cleef factory for decades, and was sad when it was torn down. I am a lawyer, and had occasion to visit the factory in the early 1980s to inspect a rubber calender mill manufactured by my client about 60 years earlier, that had been involved in a serious accident. I remember enjoying a conversation with one of the men who worked in the factory about some of its history. He had grown up in a house across the street. It is inspiring to read your article and to learn so much detail of the story of the five Van Cleef brothers, as well as of their many interests and high standards. I share their philosophy, as well as their enthusiasm for butterflies. Their story and their philosophy should be taught in business schools today!

Midwestern Manufacturing constructed Firemen’s rain coats and used midwestern Vanitex to water proof the jackets. The owner of the business was Gilbert Stowell. It was remarkable that the business was started on the second floor of the Hardware Store, in Mackinaw, Illinois. The other remarkable fact was that the business started the first of January in 1929. It almost coincided with the depression. The success of the business was built on rubberizing the outer coat with Vanitex, and the invention of the Snap Hook. Gilbert’s snap hook could be operated with only one hand to release the jacket. Gilbert’s Snap Hook was patented in 1934. I would like to know more about how the jackets were rubberized. Thanks, Bill Gillespie

My husband, Eldon Van Cleef Greenberg was the grandson of Maxime and also knew Paul well as those two brothers lived in Los Angeles in their later years. Our son has found a couple of objects from the tape business. His name is Maxim Van Cleef Greenberg. Hence, the family name moves on.

We have greatly enjoyed reading this history.

Dear Emily,

I am a real estate agent in Palm Springs. We will be placing the home of Etta and Maxime on the market in a week or so. It was build in 1939. Eldon is called out in a newspaper article as coming to stay at the house when he was an infant. It’s a very unusual house, very early modern, and we are wondering if perhaps your husband knows anything about it. He would have been very young, but perhaps in later years the house was spoken about?

Hello, Chris Menrad,

Dd you ever find out more about the home in Palm Springs of Etta and Maxime Van Cleef? I’ve only now read your question on this website. Paul Van Cleef was my father, and Max and Etta my uncle and aunt. I was always told that their house in Palm Springs was designed by the noted architect Richard Neutra. When they moved to Los Angeles in about 1939 and built a home at the corner of Warner and Loring Avenues in West L.A., the architect was Richard Neutra, which makes me even more sure that their Palm Springs home was designed by him. (That that house was designed by Neutra was verified again by articles written about the house some years ago when it was for sale.) The home built by their daughter Janis Van Cleef Greenberg and her husband Allan Greenberg some years later, on nearby Garwood Place, was also designed by Richard Neutra. The backyards of the two houses connected. Located just east of UCLA. Emily Greenberg’s comment above refers to her husband Eldon, who was the son of Janis and Allan.

Liz, I just came across this website too and see that my first cousin, Andrew Schwarz commented. My father was Gustave Howard Shamberg. Jane Shamberg was his sister. Great Uncle Felix and Ruth visited my family in Baltimore , every year, as they traveled the world. They always brought us wonderful gifts. It was always the best part of the year !

Carol, are you or Andrew on facebook? I’d love to connect. You can also email me at elizabeth.liebman@hotmail.com