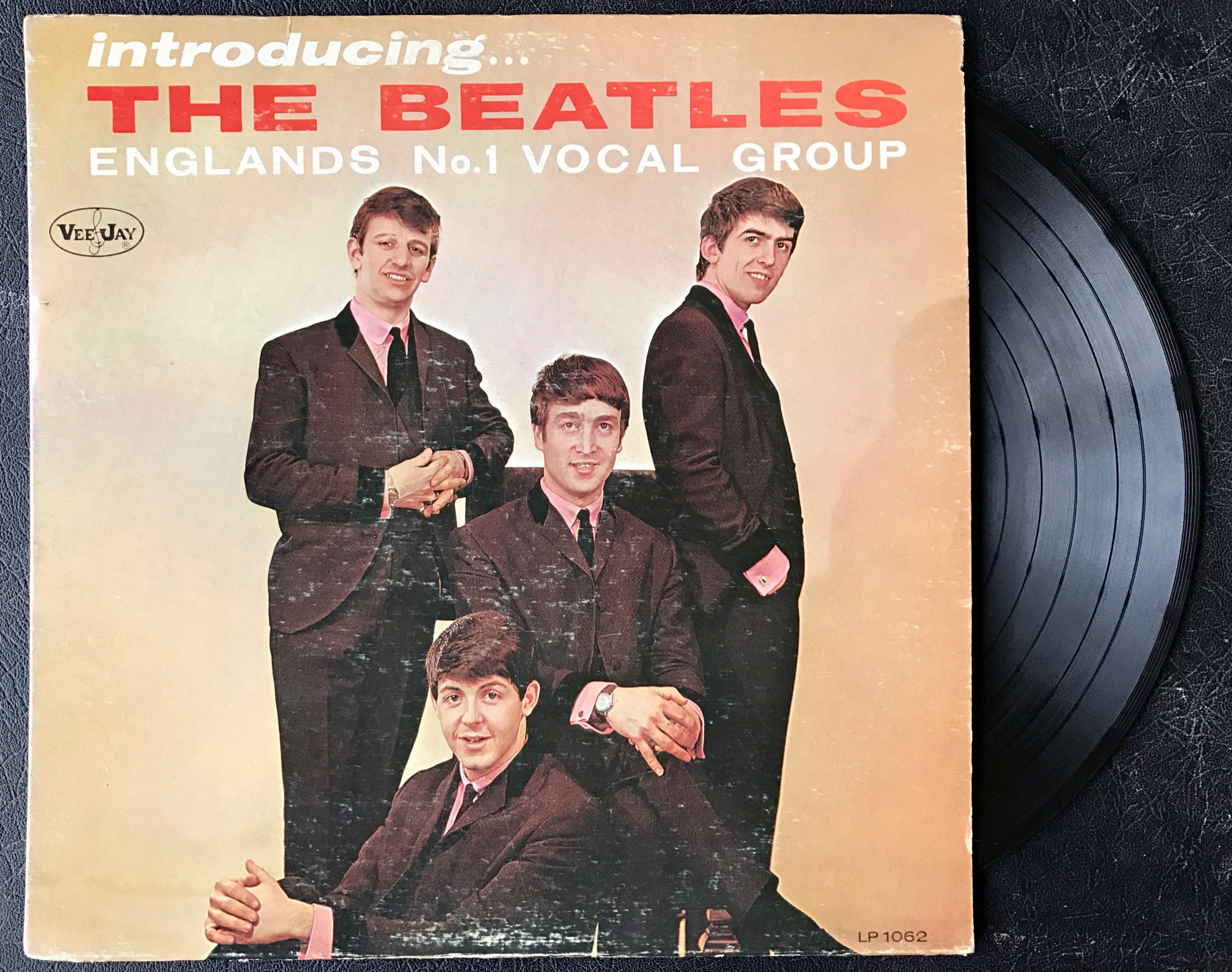

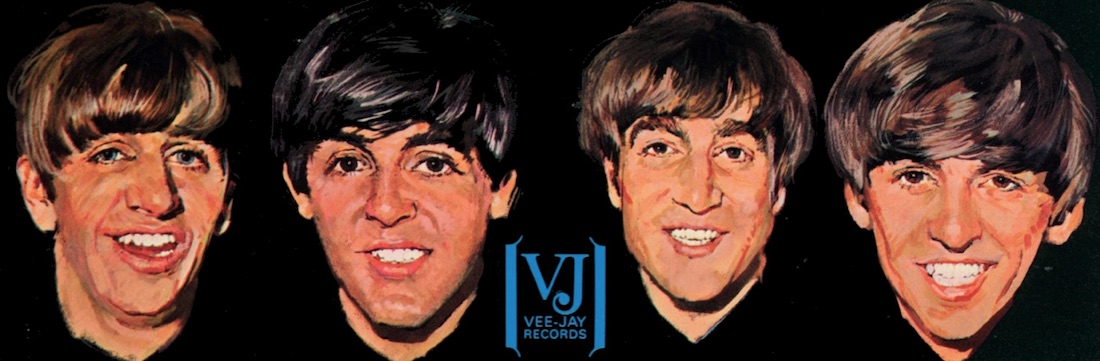

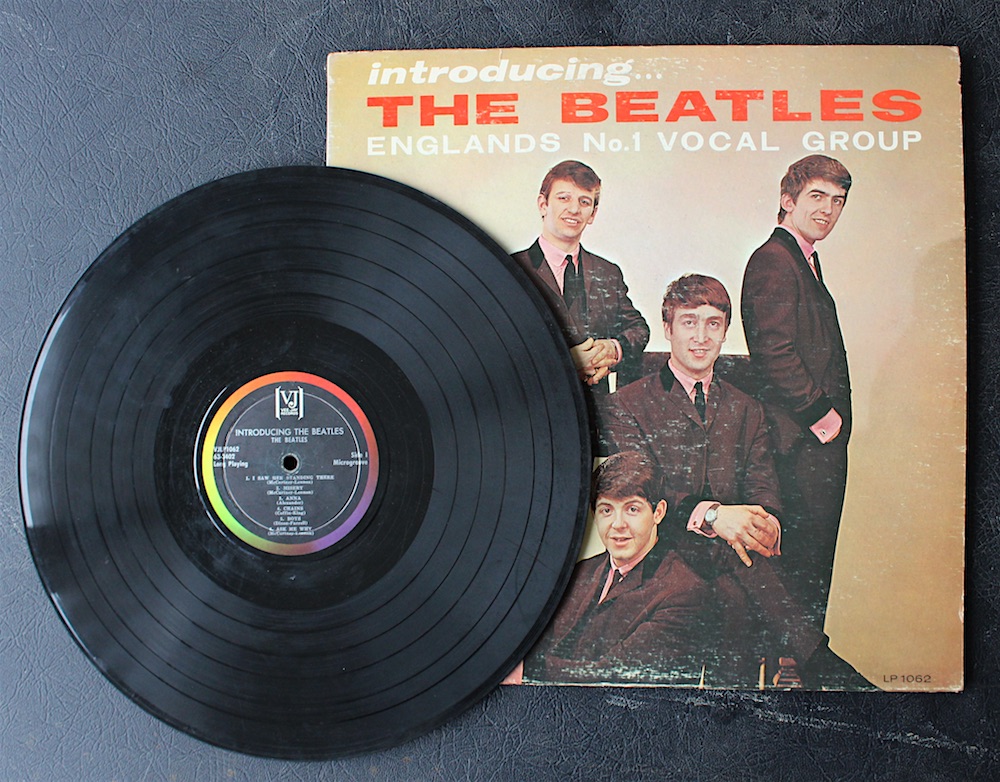

Museum Artifact: “Introducing The Beatles” Vinyl LP, 1964

Made By: Vee-Jay Records, Inc., 1449 S. Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL [Near South Side]

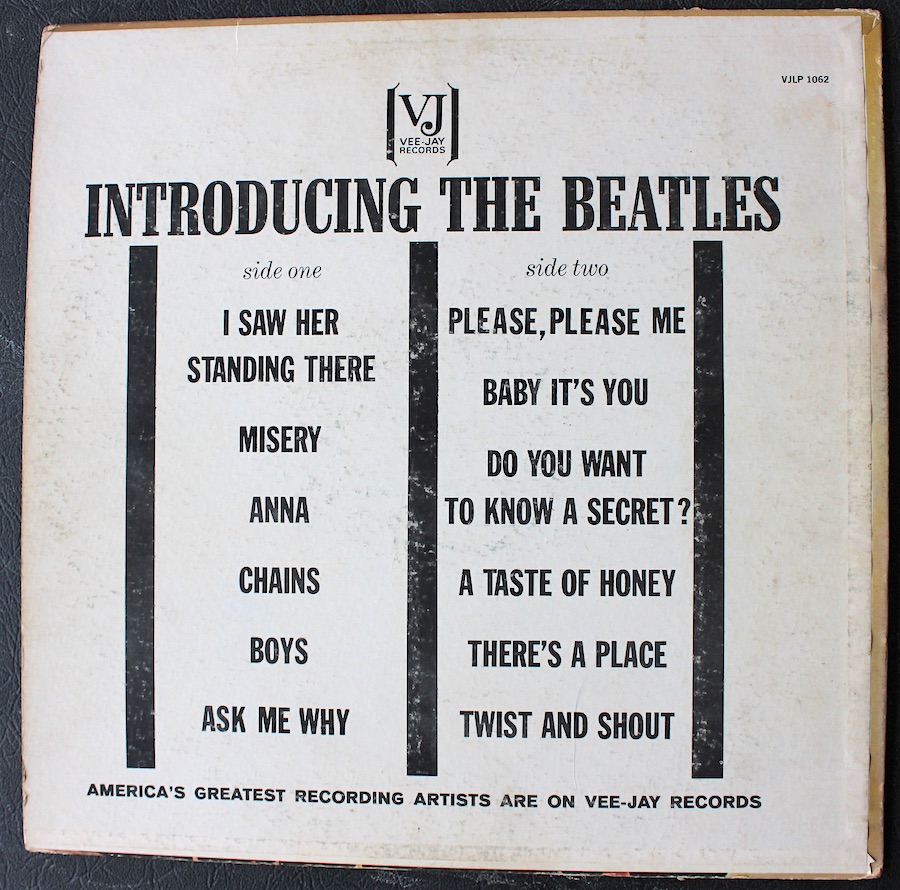

To a serious record collector, the copy of Introducing… The Beatles in our museum collection probably wouldn’t appear all that special. It is, after all, a non-mint example of the second and considerably more common version of the album, released in bulk on Chicago’s Vee-Jay label after some legal wranglings with Capitol Records in 1964 (the tracks “Love Me Do” and “P.S. I Love You” were scrapped from these later pressings due to a restraining order). To the teenage girl who actually purchased, played, cherished, and sang along to this record when it came out, however, its value remains unquantifiable. . . . And that’s a fact I have on firsthand authority from the girl herself, who later became my mother. Thanks for the donation, Mom!

Back in ’64, of course, young fans of the Liverpool lads didn’t care much about the business end of Beatlemania—labels and contract disputes, etc. They just wanted anything with John, Paul, George & Ringo on it. So, while Vee-Jay’s Introducing the Beatles has the distinction of being the first long-player Beatle album released in the U.S. (January 10, 1964), Capitol’s Meet the Beatles—released just two weeks later—immediately joined it at the top of the charts. Together, these records dropped the needle on a seismic pivot point in American culture, coming less than two months after the assassination of John F. Kennedy and one month before the Beatles themselves landed at the newly renamed JFK Airport in New York—recharging the batteries of a dazed populous in a bleak winter.

Back in ’64, of course, young fans of the Liverpool lads didn’t care much about the business end of Beatlemania—labels and contract disputes, etc. They just wanted anything with John, Paul, George & Ringo on it. So, while Vee-Jay’s Introducing the Beatles has the distinction of being the first long-player Beatle album released in the U.S. (January 10, 1964), Capitol’s Meet the Beatles—released just two weeks later—immediately joined it at the top of the charts. Together, these records dropped the needle on a seismic pivot point in American culture, coming less than two months after the assassination of John F. Kennedy and one month before the Beatles themselves landed at the newly renamed JFK Airport in New York—recharging the batteries of a dazed populous in a bleak winter.

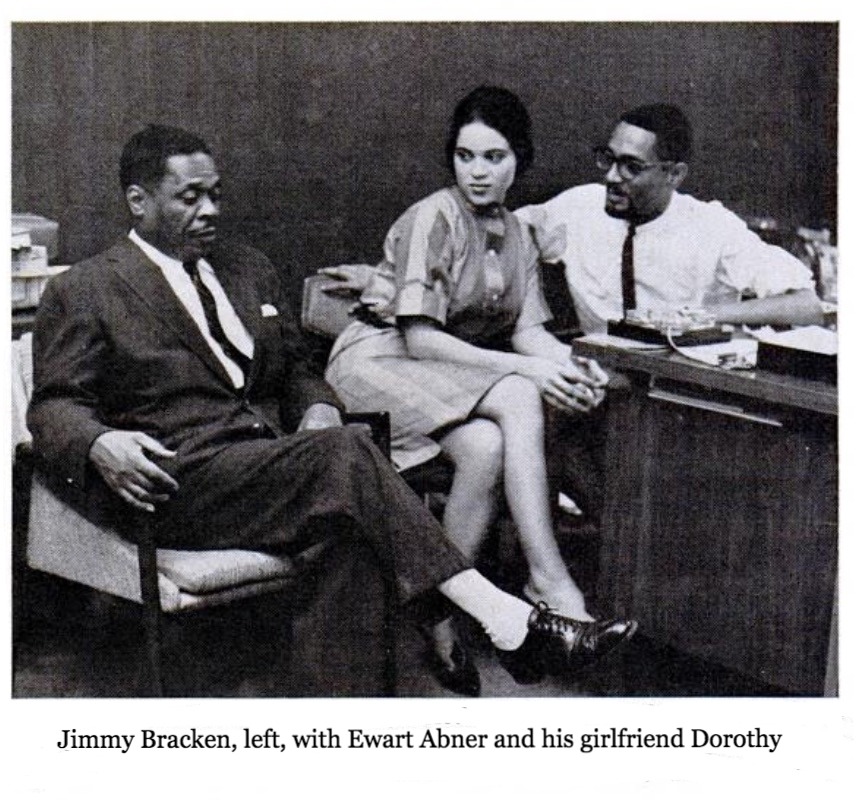

Inside the unlikely eye of this transcendental storm, meanwhile, was a small family business in Chicago—a fiercely independent record label co-owned and operated by a pioneering African-American woman, Vivian Carter, and driven by a diverse team of producers, promoters, and performers as talented as any in the country. This was Vee-Jay.

[from left: Vee-Jay co-owners Vivian Carter-Bracken and James Bracken, and company president Ewart Abner, 1961, from Ebony magazine]

[from left: Vee-Jay co-owners Vivian Carter-Bracken and James Bracken, and company president Ewart Abner, 1961, from Ebony magazine]

Now I’ll be the first to admit, using Introducing the Beatles as the representative artifact of Vee-Jay Records in the Made In Chicago Museum is simultaneously the logical choice (it was a platinum seller and their greatest dent in the zeitgeist) and a mildly insulting one, considering their larger body of work.

In the half-century since Vee-Jay’s demise, historians have inadvertently—but continuously—simplified the label’s musical legacy into a sort of frustrating “also ran” category. In a Chicago context, its contributions to blues and R&B are overshadowed by its Michigan Avenue neighbor, Chess Records. As a black-owned label, it’s eclipsed by Motown. Vivian Carter’s groundbreaking work as a female executive gets less ink than the similar efforts of her white contemporaries Estelle Axton (Stax) and Florence Greenberg (Scepter). And in the largest number of cases, Vee-Jay is merely reduced to a footnote in the oft-told saga of the Fab Four and their invasion of America.

In the half-century since Vee-Jay’s demise, historians have inadvertently—but continuously—simplified the label’s musical legacy into a sort of frustrating “also ran” category. In a Chicago context, its contributions to blues and R&B are overshadowed by its Michigan Avenue neighbor, Chess Records. As a black-owned label, it’s eclipsed by Motown. Vivian Carter’s groundbreaking work as a female executive gets less ink than the similar efforts of her white contemporaries Estelle Axton (Stax) and Florence Greenberg (Scepter). And in the largest number of cases, Vee-Jay is merely reduced to a footnote in the oft-told saga of the Fab Four and their invasion of America.

To set the record straight (pun intended), Vee-Jay didn’t need the Beatles to achieve success. If anything, the Beatles went looking for Vee-Jay. And in terms of record companies with a track record (pun less intended) for recruiting, recording, and marketing elite-level talent in the 1950s and 1960s, Vee-Jay’s resume easily speaks for itself. . . . But we’ll reiterate a bit anyway.

I. Livin’ with Vivian

Vee-Jay Records was launched in 1953 as an offshoot of a Gary, Indiana record shop owned by the aforementioned Vivian Carter and her soon-to-be husband James Bracken. Vivian (1921-1989) was something of a local celebrity—a velvet-voiced charmer who hosted a popular radio show, “Livin’ with Vivian,” on Gary stations WGRY and WWCA. “I was lucky to be able to tell what the people liked because of my program,” she later told Ebony magazine.

For several years, Vivian learned all about the relationship between music and marketing. She could hear a new record at her shop and promote it on her show (which featured mostly gospel and a little rhythm & blues), or—in many cases—she’d get positive feedback about a song from her radio listeners, and use it as an impetus to try and stock the corresponding record at the store. The only snag was that many local acts simply didn’t have any recordings available outside of a demo. And so, the next logical step became crystal clear.

For several years, Vivian learned all about the relationship between music and marketing. She could hear a new record at her shop and promote it on her show (which featured mostly gospel and a little rhythm & blues), or—in many cases—she’d get positive feedback about a song from her radio listeners, and use it as an impetus to try and stock the corresponding record at the store. The only snag was that many local acts simply didn’t have any recordings available outside of a demo. And so, the next logical step became crystal clear.

In their first foray into the record-making biz, Vivian and Jimmy spent $500 in 1953 cutting a couple singles for a teenage singing group, the Spaniels, who’d recently won a talent contest at Vivian’s old high school. Those tunes, which were actually released through Chicago’s Chance Records on the first go-round, were then played on Vivian’s radio show (not sure if self-payola is a thing) and soon found a wider audience across the Chicagoland area. The experiment was a success. Vee-Jay Records (as in “V” for Vivian and “J” for James) was a go.

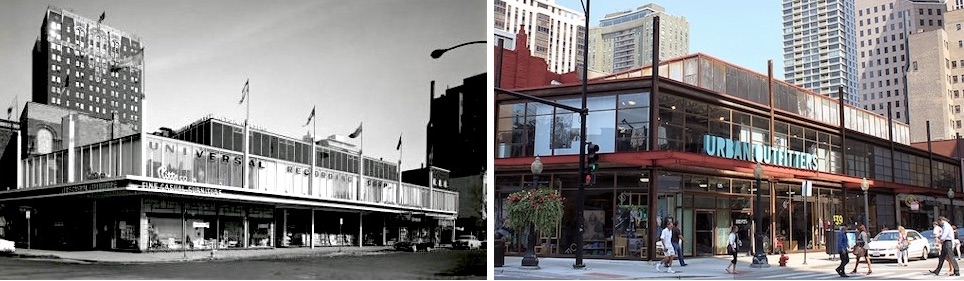

Despite its Gary roots, Vee-Jay operated, right from the beginning, as a Chicago business. This was largely because its original A&R man, Vivian’s brother Calvin Carter, was based in Chicago and equipped with connections. In 1953 alone, Calvin set up Vee-Jay’s first rehearsal/audition space in a garage at 47th Street and King Drive; discovered and signed its first marquee blues act in Jimmy Reed (who had been working in the Union Stockyards); and established a regular studio use arrangement with the Universal Recording Corp., one of the largest independent studios in the country.

[Most of Vee-Jay’s records were cut in the studios of Chicago’s Universal Recording Corp, which moved into this massive building at 46 E. Walton Street in 1955. The building is seen as a storefront in 2010 on the right. It has since been rehabbed again to the point of being nearly unrecognizable.]

[Most of Vee-Jay’s records were cut in the studios of Chicago’s Universal Recording Corp, which moved into this massive building at 46 E. Walton Street in 1955. The building is seen as a storefront in 2010 on the right. It has since been rehabbed again to the point of being nearly unrecognizable.]

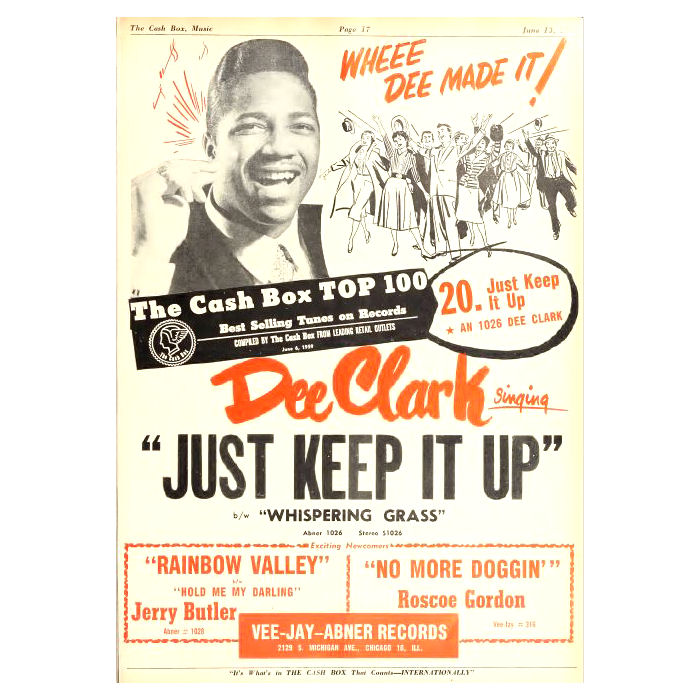

Vee-Jay also found a key partner in Chicago’s United Record Distributors, the first major black-owned music distribution company in the country, run by brothers George and Ernie Leaner (who later formed their own One-derful! label in 1962). It was at the United offices, at 2029 S. Michigan Avenue, just before Christmas in 1953, that Vivian Carter and Jimmy Bracken’s professional partnership became a more legally binding arrangement.

“Last week, December 16, while Ernie Leaner of United Record Distributors was very, very busy taking orders and helping his men pack off those Xmas record shipments, in walked Vivian Carter and Jimmy Bracken, partners in Vee Jay Records,” Cash Box magazine reported in its Jan 2, 1954 issue. “. . . ‘We’re looking for a preacher,’ Vivian casually mentioned to Ernie, after the usual affable greetings among these friends. Ernie’s ears pricked right up. His eyes lighted. But, looking out the window, with the snowy rain acomin’ down, Ernie said, ‘I know a preacher. He’s just down the street. Now you two stay here out of this bad weather,’ Ernie urged, ‘and I’ll go fetch him.’ So Ernie dashed down the street just as fast as he could go. And on the way bought a gorgeous bouquet for Vivian. Came back with the preacher and said, ‘Here they are, Reverend.’ So-o-o-o with Ernie Leaner and his secretary serving as the two necessary witnesses, Vivian Carter and Jimmy Bracken tied themselves together into the firmest kind of partnership by becoming Mr. and Mrs. And this happened right in the gay and festive Christmasy offices of United Record Distributors here in good, ole Chicago.”

“Last week, December 16, while Ernie Leaner of United Record Distributors was very, very busy taking orders and helping his men pack off those Xmas record shipments, in walked Vivian Carter and Jimmy Bracken, partners in Vee Jay Records,” Cash Box magazine reported in its Jan 2, 1954 issue. “. . . ‘We’re looking for a preacher,’ Vivian casually mentioned to Ernie, after the usual affable greetings among these friends. Ernie’s ears pricked right up. His eyes lighted. But, looking out the window, with the snowy rain acomin’ down, Ernie said, ‘I know a preacher. He’s just down the street. Now you two stay here out of this bad weather,’ Ernie urged, ‘and I’ll go fetch him.’ So Ernie dashed down the street just as fast as he could go. And on the way bought a gorgeous bouquet for Vivian. Came back with the preacher and said, ‘Here they are, Reverend.’ So-o-o-o with Ernie Leaner and his secretary serving as the two necessary witnesses, Vivian Carter and Jimmy Bracken tied themselves together into the firmest kind of partnership by becoming Mr. and Mrs. And this happened right in the gay and festive Christmasy offices of United Record Distributors here in good, ole Chicago.”

Right around the same time—as a wedding gift you might say—the Spaniels scored Vee-Jay’s first national R&B hit with “Goodnite, Sweetheart, Goodnite” (covered to even greater success later by the McGuire Sisters). Vivian, Jimmy and Calvin now had a sense that they could legitimately compete on the big stage, even if it meant watching white artists inevitably butcher their tunes shortly thereafter.

II. Behind the Music

Over the next year or so, 1954 into 1955, Vee-Jay got its house band together, purchased its own downtown offices on “Record Row” at 2129 S. Michigan Avenue (Chess Records would move in across the street, at 2120 S. Michigan, in 1956), and started accumulating a bigger roster of talent. In ’55, a local doo-wop group called the El Dorados notched the label its first hit on the national pop charts, and behind the scenes, an accountant named Ewart Abner left the now defunct Chance Records to become the general manager of Vivian and Jimmy’s budding business.

“Vivian and Jimmy didn’t really know all that much about business things when it got into the real heavy paperwork,” former Vee-Jay saxophonist Red Holloway recalled to journalist Mike Callahan in a 1981 Goldmine article. “So since Abner had been doing that at Chance, they just made a deal with him and he went over there. Abner became pretty much the boss. Jimmy and Vivian still called the shots, because they owned the label, but when it came to the final details of making deals and stuff, that’s where Abner was the boss, because he knew more about it and had more insight into what was happening.”

A graduate of Englewood High School and Howard University, Ewart Abner (1923-1997) first broke into the industry working in a Chicago record pressing plant in the ‘40s. He was a small, skinny fellow—hardly intimidating—but he carried a different sort of weight; a confidence that comes with being the smartest guy in the room. After going back to school to get an accounting degree from Depaul, he helped establish the Chance label in 1950 (with Art Sheridan), working on sessions with doo-wop luminaries the Moonglows and Flamingos. Later in his career, Abner’s greatest fame would come as a manager and eventual president of Motown during much of its golden era (1967-1975), managing acts like the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, the Temptations, the Jackson 5, and Stevie Wonder (he’d remain Stevie’s personal business manager into the 1980s). It was during his time with Vee-Jay, though, that Abner really built his reputation, not only introducing the world to the “Chicago Soul” sound, but expanding the horizons of what a “black label” could do.

A graduate of Englewood High School and Howard University, Ewart Abner (1923-1997) first broke into the industry working in a Chicago record pressing plant in the ‘40s. He was a small, skinny fellow—hardly intimidating—but he carried a different sort of weight; a confidence that comes with being the smartest guy in the room. After going back to school to get an accounting degree from Depaul, he helped establish the Chance label in 1950 (with Art Sheridan), working on sessions with doo-wop luminaries the Moonglows and Flamingos. Later in his career, Abner’s greatest fame would come as a manager and eventual president of Motown during much of its golden era (1967-1975), managing acts like the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, the Temptations, the Jackson 5, and Stevie Wonder (he’d remain Stevie’s personal business manager into the 1980s). It was during his time with Vee-Jay, though, that Abner really built his reputation, not only introducing the world to the “Chicago Soul” sound, but expanding the horizons of what a “black label” could do.

“Abner was the smartest guy I ever met in the record business, period,” claimed Bill Matheson, a lawyer who routinely negotiated with Abner while representing his client, R&B singer Jerry Butler. “No one came close. In fact, he was overqualified to be in the record business. . . . He apparently was a voracious reader, and could remember everything he read—something close to total recall. . . . He’d read something translated from Chinese just to find out what they were thinking. . . . He was a brilliant Renaissance guy.”

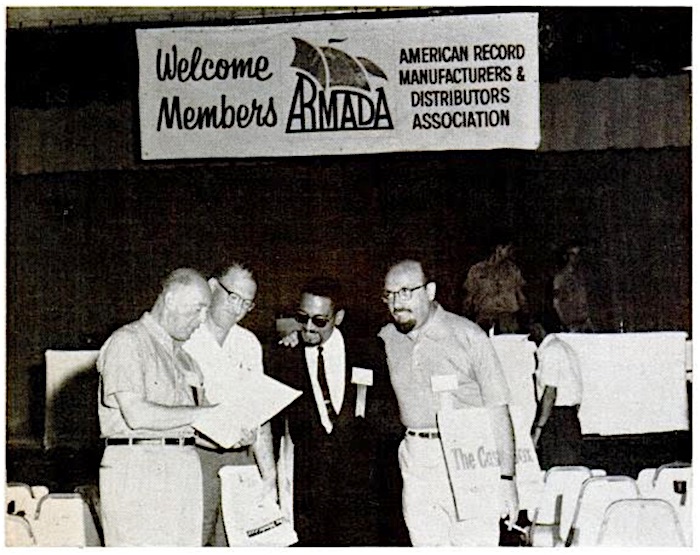

[Ewart Abner (dark suit) at a meeting of the American Record Manufacturers & Distributors Association with industry men William Shockett, Amos Heilicher, and Atlantic Records president Ahmet Ertegun. From Ebony magazine, 1961.]

[Ewart Abner (dark suit) at a meeting of the American Record Manufacturers & Distributors Association with industry men William Shockett, Amos Heilicher, and Atlantic Records president Ahmet Ertegun. From Ebony magazine, 1961.]

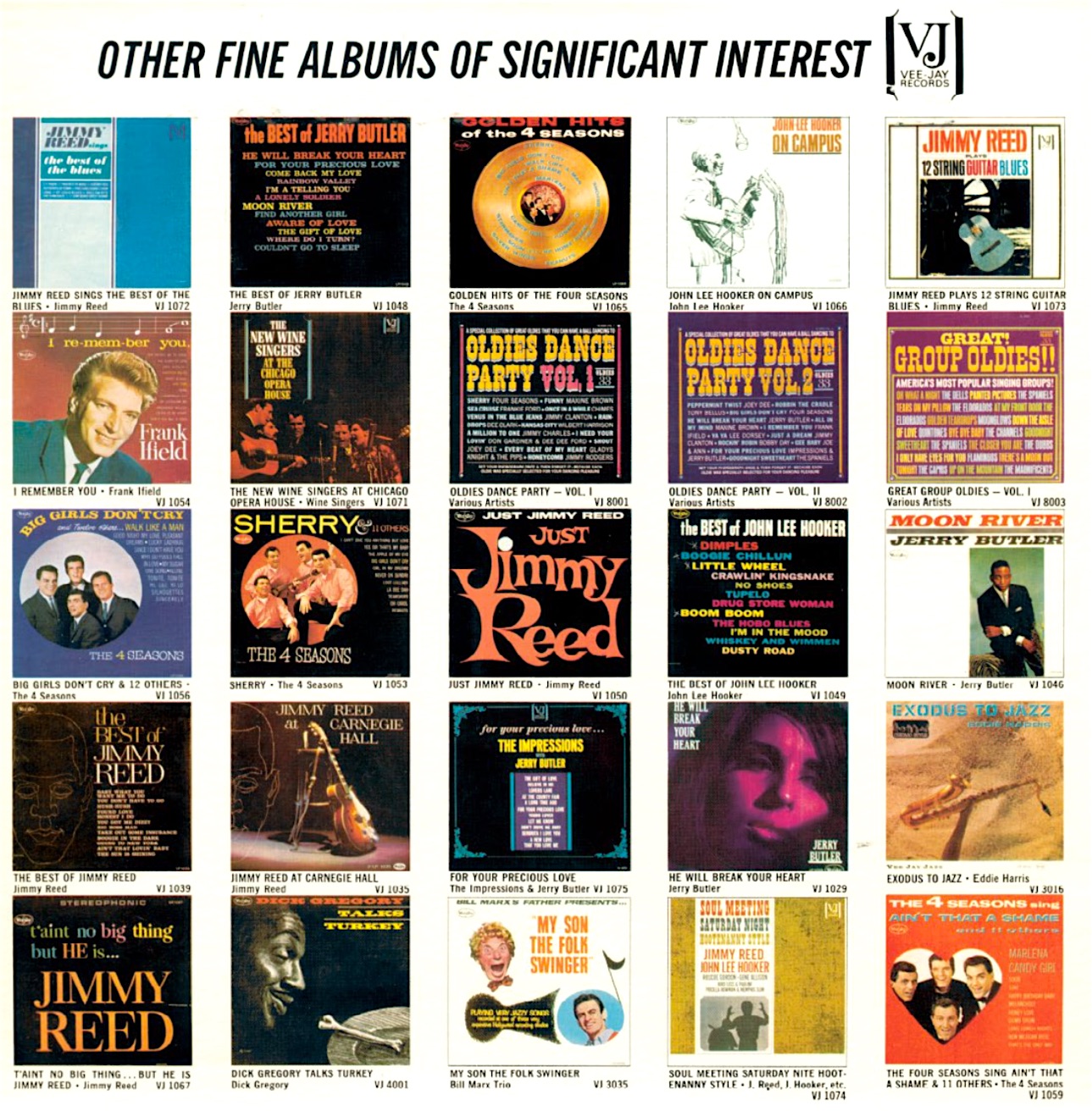

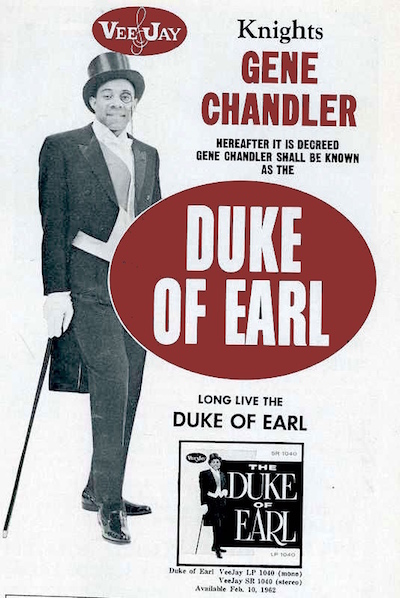

Abner tended to impress a lot of people he met, lawyers or otherwise. During his time as the face of Vee-Jay, he became something of a pied piper for his peers in the industry, organizing the American Record Manufacturers and Distributors Association in 1958. He also knew that sustained success depended on breaking down the old walls between white and black music—be it in distribution, radio play, and even talent acquisition. Vee-Jay employed both black and white foot soldiers to promote their artists across the country, and those artists themselves began to include more mainstream white pop acts, as well (about 30% of the Vee-Jay roster by 1961).

“If we want to stay in business,” Abner told Ebony, “we’ve got to stop thinking of ourselves as just a Negro company.”

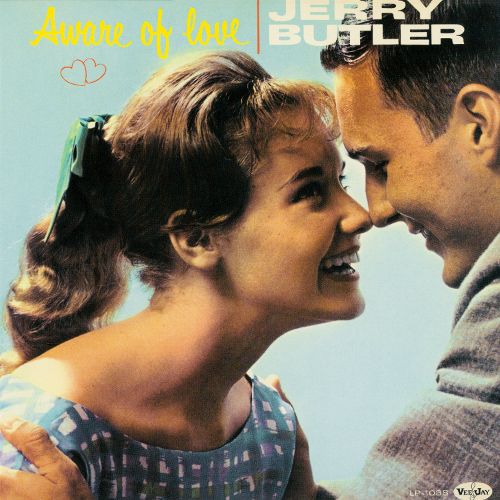

[Sometimes the Vee-Jay crossover strategy included putting some very vanilla looking white teens on the album cover of a black soul singer like Jerry Butler]

[Sometimes the Vee-Jay crossover strategy included putting some very vanilla looking white teens on the album cover of a black soul singer like Jerry Butler]

Abner, like a lot of ballsy intellectuals, was also a gambling man, and this wound up posing some serious problems for his employers down the road. In Vee-Jay’s formative years, though, Abner and Calvin Carter formed a truly dynamic duo. From soul and gospel to blues, jazz, and pop, they seemed to have a radar for star power and an instinct for fostering it. Abner handled the numbers, and Carter—a talented singer in his own right—held the auditions, ran the recording studio, and pinpointed the hooks.

“Calvin did it for 12 years,” Jerry Butler later said, “and when you list the acts he signed, using no other ears to depend on but his own, it reads like a ‘who’s who’ in the music business. He covered every base. For example, gospel acts he signed: Five Blind Boys, the Staple Singers, the Swan Silvertones, Maceo Woods, the Raspberry Singers. In the blues field, he signed Jimmy Reed and John Lee Hooker. In R&B, the Dells, the Spaniels, myself, the El Dorados. Female singers such as Priscilla Bowman and Betty Everett. The jazz artists included Eddie Harris and the MJT+3.”

Like his sister Vivian, Calvin Carter [pictured] had a natural knack for promotion, and like Abner, he maintained an unblinking focus on the goals at hand, particularly in the role of A&R man.

Like his sister Vivian, Calvin Carter [pictured] had a natural knack for promotion, and like Abner, he maintained an unblinking focus on the goals at hand, particularly in the role of A&R man.

“As soon as [Calvin Carter] thought he had a winner,” Butler said, “he started promoting it himself and didn’t stop until it was a hit.

“Unfortunately, the only industry people knowing him today are those who came in contact with him back in those days; but I think he deserves a place in R&B music on the same level as Phil Spector.”

Comparisons to Phil Spector don’t exactly mean what they used to, but you still get the point.

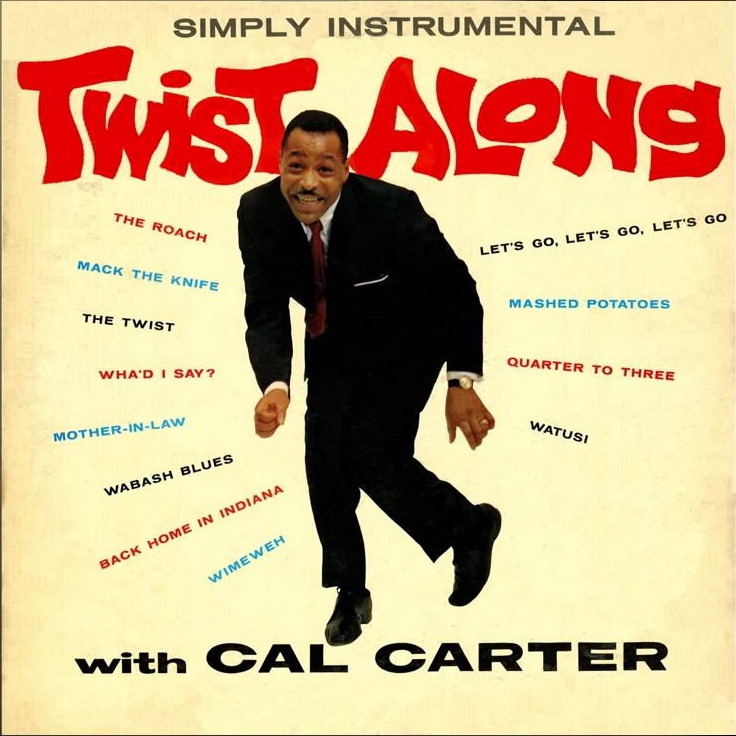

[Along with guiding Vee-Jay’s sound from behind the scenes, Calvin Carter also sometimes put himself on wax, including this obscure number from 1962]

[Along with guiding Vee-Jay’s sound from behind the scenes, Calvin Carter also sometimes put himself on wax, including this obscure number from 1962]

III. Biggest Little Giant

The Brackens moved the Vee-Jay HQ down the street to its more famous location, 1449 S. Michigan Ave., in 1960 (the same building would later house Brunswick Records from 1966 to 1976). By now, Vee-Jay was a big enough name that talent tended to seek them out, rather than the other way around.

[The Vee-Jay office building at 1449 S. Michigan, in 1961 and 2016]

[The Vee-Jay office building at 1449 S. Michigan, in 1961 and 2016]

In 1961, another one of Vee-Jay’s Michigan Avenue neighbors, the Johnson Publishing Company, made the label the focus of a feature article in the pages of Ebony magazine.

“Among America’s top record manufacturers—the men who know recordings best—Chicago’s hit making Vee-Jay Record Co. is fast becoming the biggest little giant in the industry,” the article claimed. “In a business known for its get-rich-quick luck and disappointing heartbreak, the Windy City firm now ranks tops among the 500 independent companies and has begun competing against the mighty chains who once controlled the market.”

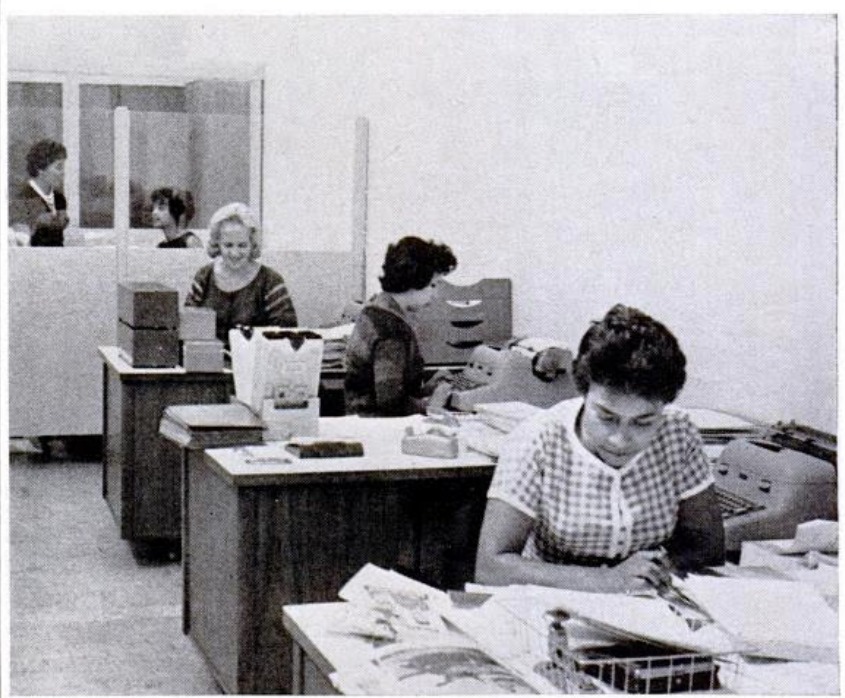

[Receptionists at the Vee-Jay offices in 1961. From left to right: Vera Watson, Charlotte Iwanaga Enright, Judy Snowden, Elena Morelieras, and Sharon Gamble. From Ebony magazine.]

[Receptionists at the Vee-Jay offices in 1961. From left to right: Vera Watson, Charlotte Iwanaga Enright, Judy Snowden, Elena Morelieras, and Sharon Gamble. From Ebony magazine.]

Vee-Jay had a fairly small staff of 22 employees in 1961, but they were grossing $3 million annually—about $25 million after inflation—and clearly feeling cocky about it (best example: a 1961 release titled Jimmy Reed at Carnegie Hall, which was literally just a studio session of Reed playing inside a rented room in Carnegie Hall—there had been no live show).

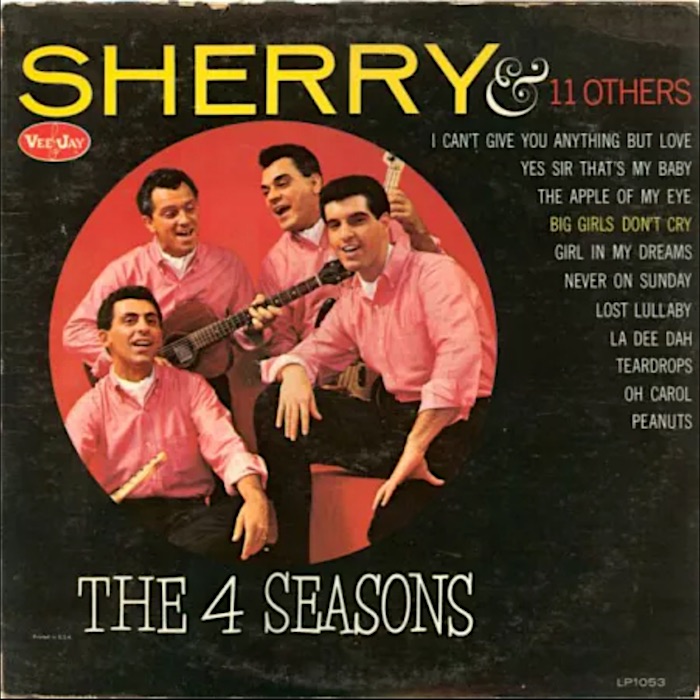

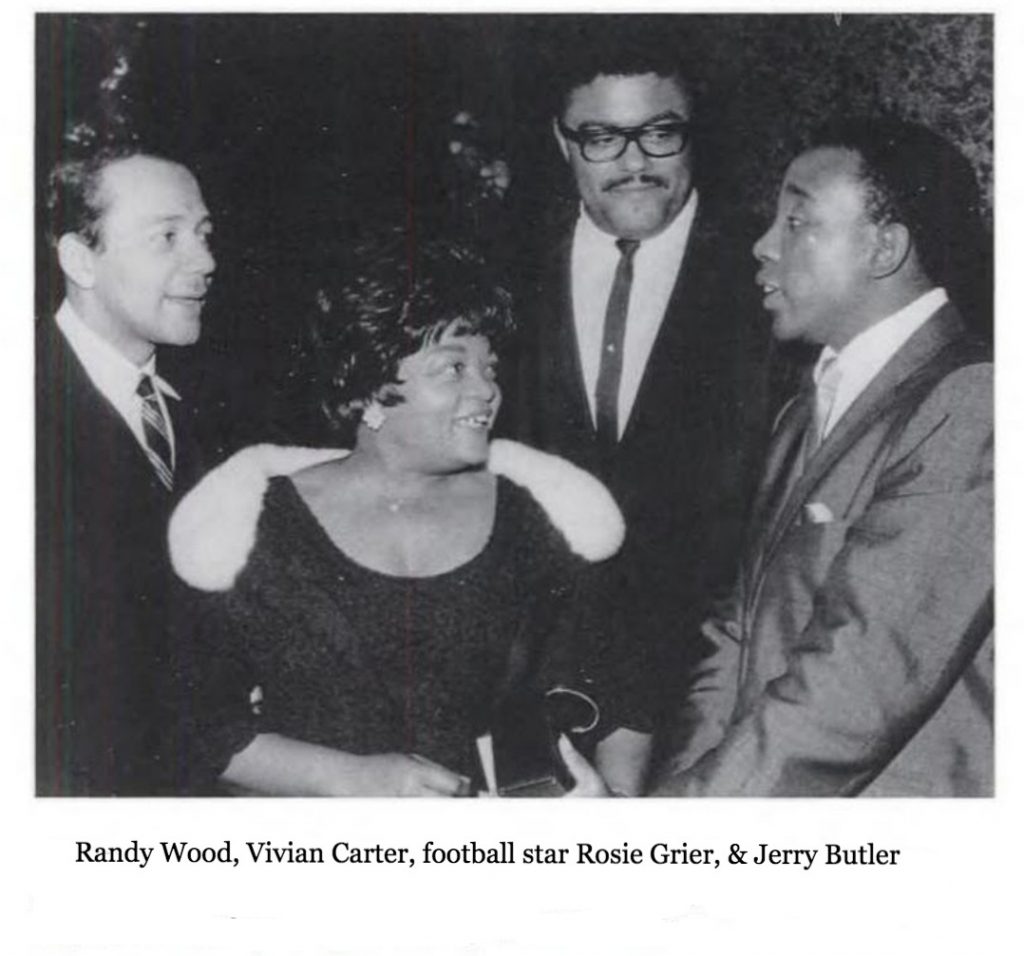

Heads only grew larger by the spring of ‘62, when Gene Chandler’s “Duke of Earl” became the label’s first million seller, soaring to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 for three weeks. Later that summer, one of Ewart Abner’s great white hopes, a harmony group from New Jersey called the Four Seasons (discovered by a new Vee-Jay rep named Randy Wood), hit the No. 1 spot with their debut single, “Sherry.” Their next release, “Big Girls Don’t Cry,” promptly followed suit, turning the group into a sensation. In a truly groundbreaking development, the biggest white act in America was putting out its records on a black-owned label. Abner’s genius was confirmed, and observers as far away as London were taking note.

IV. Leading the Invasion

In the summer of ’62, at the same time the Four Seasons were exploding, a young British torch singer named Frank Ifield was enjoying a breakout No. 1 hit of his own—in his native UK, at least—with a cover of an old WWII tune, “I Remember You.” EMI owned the rights to the track overseas, but their U.S. subsidiary, Capitol, took a hard pass on releasing it in the States. So, as the fates would have it, EMI turned to that hot new label in Chicago—the one with the Four Seasons—to bring Frank Ifield stateside. Happily embracing another opportunity to expand its portfolio, Vee-Jay inked a licensing agreement to put out the record, and it did well, reaching No. 5 on the charts.

Subsequent Ifield records mostly fizzled out, but for Vee-Jay, the more important development was its new relationship with EMI, which positioned them as a viable destination for any additional British acts that Capitol—in its infinite wisdom—deemed unfit for the U.S. market. You can see where this is leading.

In January of 1963, Vee-Jay Records—with virtually no fanfare—agreed to a licensing agreement for a batch of recordings by a spunky Liverpool quartet called The Beatles. Vee-Jay’s chief international representative at the time was a 30 year-old woman named Barbara Gardner, who traveled to London to cut the deal. By the end of the decade, Gardner (by then known as Barbara Proctor) would become the first African-American woman to own and operate her own advertising agency.

In retrospect, the Beatles signing certainly looks like an incredibly fortuitous gamble for Vee-Jay, but the pay-off wasn’t as instantaneous as one might expect—nor did the label seem to realize just how big of a marlin they had actually managed to wrangle.

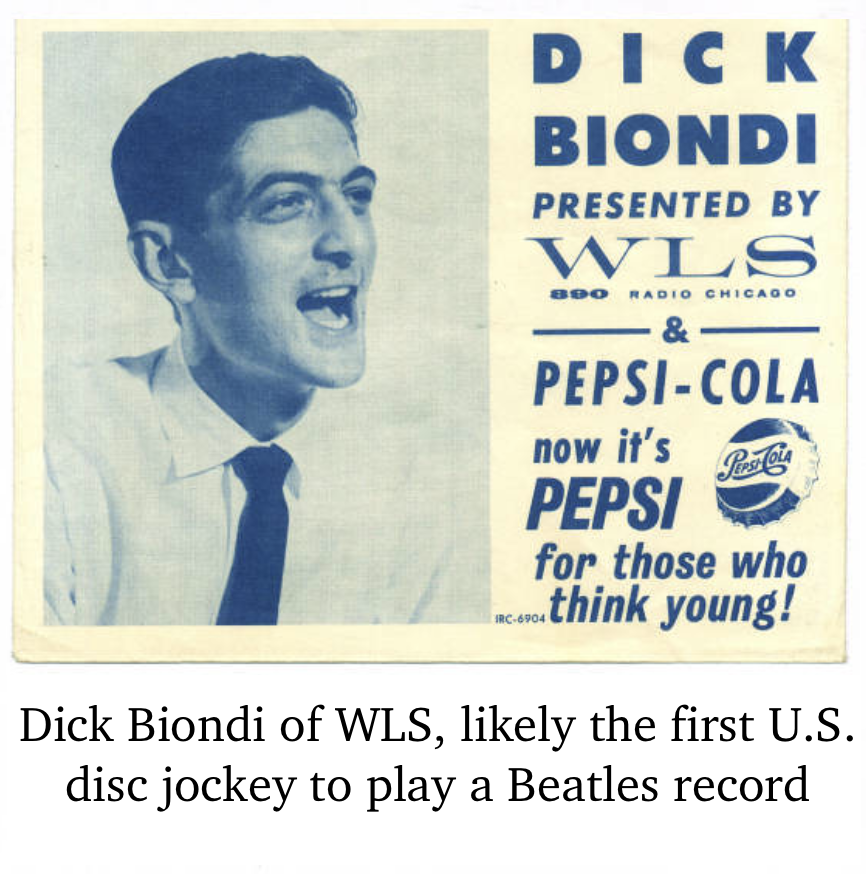

Case in point, when Vee-Jay released its first Beatles single, “Please Please Me,” in February of 1963, the initial pressings all misspelled the band’s name as BEATTLES, with a now infamous extra T tossed in. Perhaps still none the wiser, Ewart Abner handed the record to disc jockey Dick Biondi at Chicago’s WLS, who subsequently gave the Fab Four their first known radio airplay in America, a full year before the British Invasion effectively began. Radio listeners didn’t seem to dig the Beattles as much as they’d eventually love the Beatles, however, and the single topped out at #35 on WLS before disappearing. The follow-up, “From Me To You,” also made little impact, seemingly validating Capitol’s decision to pass on the Liverpudlians in the first place.

Case in point, when Vee-Jay released its first Beatles single, “Please Please Me,” in February of 1963, the initial pressings all misspelled the band’s name as BEATTLES, with a now infamous extra T tossed in. Perhaps still none the wiser, Ewart Abner handed the record to disc jockey Dick Biondi at Chicago’s WLS, who subsequently gave the Fab Four their first known radio airplay in America, a full year before the British Invasion effectively began. Radio listeners didn’t seem to dig the Beattles as much as they’d eventually love the Beatles, however, and the single topped out at #35 on WLS before disappearing. The follow-up, “From Me To You,” also made little impact, seemingly validating Capitol’s decision to pass on the Liverpudlians in the first place.

And then . . . everything began to change, not just for John, Paul, George and Ringo, but the Chicago label that had hitched itself to their rocketship. By the summer of ’63, Beatlemania had officially broken out in Britain—the screaming girls, the media storm, the whole nine yards. At the same time, Vee-Jay was beginning a year of turnover, tumult, and plot twists the likes of which most labels wouldn’t experience in a lifetime. It started with an announcement that “hit the industry with the force of an explosion,” according to Billboard magazine, as Ewart Abner was unceremoniously fired from his post as company president.

Vivian and Jimmy Bracken hadn’t exactly been conservative with their new wealth over the past couple years, but none of their lavish expenses could account for how much debt seemed to be mounting at the Vee-Jay offices. The true culprit, it seemed—to everyone’s despair—was Abner. His own high-roller lifestyle and a penchant for high stakes gambling had, according to many accounts, forced him to “borrow” from the company kitty—something in the neighborhood of $200,000. Far worse than that, the label had fallen into a slew of other holes, owing back taxes to the government, $250,000 in overdue bills to a single pressing plant alone, and most glaringly, a big chunk of royalty money to the Four Seasons—which had pushed the group to file a lawsuit.

Vivian and Jimmy Bracken hadn’t exactly been conservative with their new wealth over the past couple years, but none of their lavish expenses could account for how much debt seemed to be mounting at the Vee-Jay offices. The true culprit, it seemed—to everyone’s despair—was Abner. His own high-roller lifestyle and a penchant for high stakes gambling had, according to many accounts, forced him to “borrow” from the company kitty—something in the neighborhood of $200,000. Far worse than that, the label had fallen into a slew of other holes, owing back taxes to the government, $250,000 in overdue bills to a single pressing plant alone, and most glaringly, a big chunk of royalty money to the Four Seasons—which had pushed the group to file a lawsuit.

With Abner ousted, Vivian and Jimmy installed Randy Wood as the new president, and his new management team—largely based in Los Angeles—took over 49% ownership of the business. Calvin Carter (who remained in Chicago) was a stockholder, too, but he began to clash with his L.A. partners right from the get-go, particularly when Wood pushed for the label to move its offices to the West Coast and focus more attention on its pop acts. Calvin, effectively representing his sister and brother-in-law, wanted Vee-Jay to get back to its Chicago roots. A civil war was essentially underway, and amid all that chaos, a crucial legal battle was brewing, as well.

[Beatlemania was in full swing in Britain throughout 1963, but in the States, this CBS News story from the morning of November 22 was many Americans’ introduction to the phenomenon. The report was due to re-air that night, but the assassination of JFK delayed the re-broadcast for weeks.]

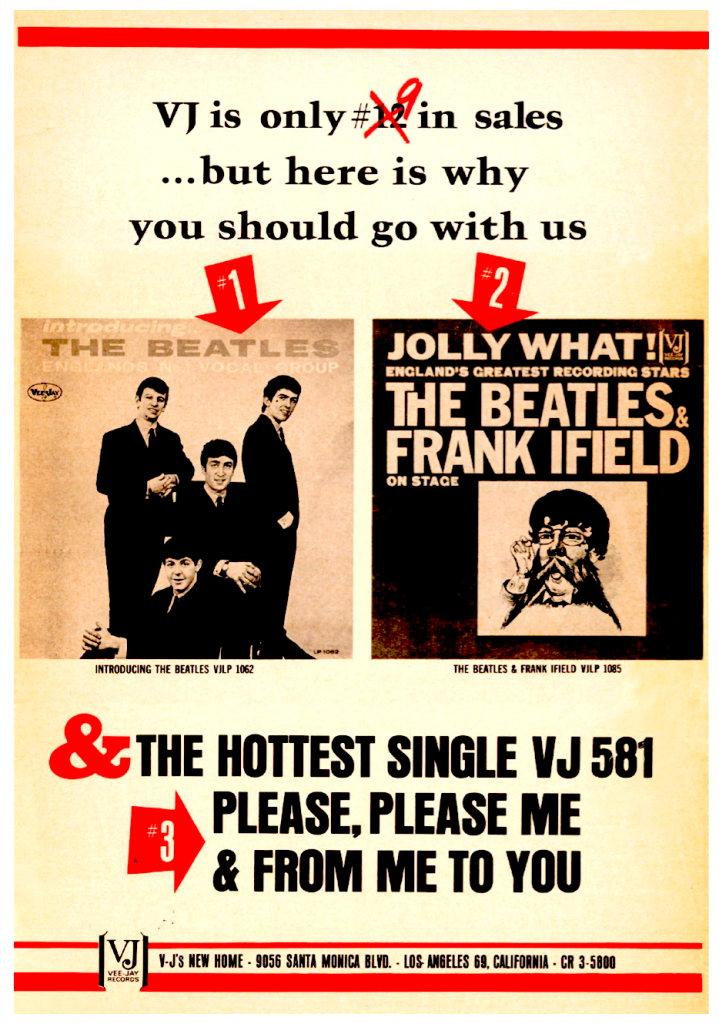

V. Vee-Jay vs. Capitol

Just about the only thing everyone at Vee-Jay could agree on by the end of 1963 was that, in order to make money and pay their debts, they would need to get a Beatles LP out on the shelves ASAP. By now, Capitol Records had realized its earlier mistake and had acquired its own batch of Beatles songs from EMI, with an album slated for a January 1964 release. Beatlemania was hard-charging for the shores of the U.S., and Vee-Jay couldn’t possibly let it happen while sitting on a stack of unsold recordings.

Fortunately, Calvin Carter already had most of Introducing the Beatles in the bag and ready to go. Vee-Jay had actually planned on releasing it back in the summer of 1963, but the Abner firing and ensuing madness had put it on the back burner. Now, by throwing together packaging, pressing, distribution, etc., they could make up lost ground and beat Capitol to the punch.

Sure enough, the first version of Introducing arrived just before Capitol’s Meet the Beatles in January of ’64, and it became every bit the financial godsend that Vee-Jay had hoped for. Since Capitol experienced even greater sales with its record, you might think everyone could reap the rewards together in peaceful solidarity, basking in Beatlemania’s riches. But Goliath was not interested in being David’s friend.

Instead, Capitol filed suit (one of about 64 lawsuits Vee-Jay had pending at the time, according to Randy Wood), claiming that a failure to pay royalties had rendered all of Vee-Jay’s previous rights to the Beatles catalog null and void.

“We put the album out, and EMI, through Capitol, sued us to cease and desist,” Calvin Carter told Goldmine in 1981. “They got an injunction against us seemingly every week. They would get an injunction against us on Monday, and we would get it off on Friday, then we’d press over the weekend and ship on Monday; we were smooth, we had everybody alerted, and we were pressing records all the time on the weekends.”

“We put the album out, and EMI, through Capitol, sued us to cease and desist,” Calvin Carter told Goldmine in 1981. “They got an injunction against us seemingly every week. They would get an injunction against us on Monday, and we would get it off on Friday, then we’d press over the weekend and ship on Monday; we were smooth, we had everybody alerted, and we were pressing records all the time on the weekends.”

Even when a judge ordered Vee-Jay to cease any use of the songs “Love Me Do” and “P.S. I Love You” (both on Version 1 of Introducing), the battle was far from from over. Instead, through an admirable effort of focused desperation, Vee-Jay threw together Version 2 of the album, replacing the banned tracks with “Please Please Me” and “Ask Me Why.” A ramshackle new back cover came with it, revealing the updated track list in two plain columns.

The Version 2 album in our museum collection was likely pressed in February or March of 1964, and it was one of more than a million copies sold that year. Unfortunately, Vee-Jay’s ongoing legal fight was less fruitful, as they finally settled out of court in April, agreeing to pay royalties to Capitol on future sales.

“We finally made something out of the court settlement, because we just couldn’t afford to fight that big a company,” Calvin Carter said. “We kept what we had, and they had all future product. We were selling so many Beatles records, we just couldn’t afford to fight for the five-year rights. At that point, we had even got a ten-year moratorium from our creditors on our outstanding bills, that we’d just keep them coming. There was a lot of pressure on us. We sold in one month’s time about 2.6 million Beatles singles on Vee-Jay and Tollie [a subsidiary]. Those were fantastic times. And right in the middle of this, we moved from Chicago to California. What a mess, what a mess.”

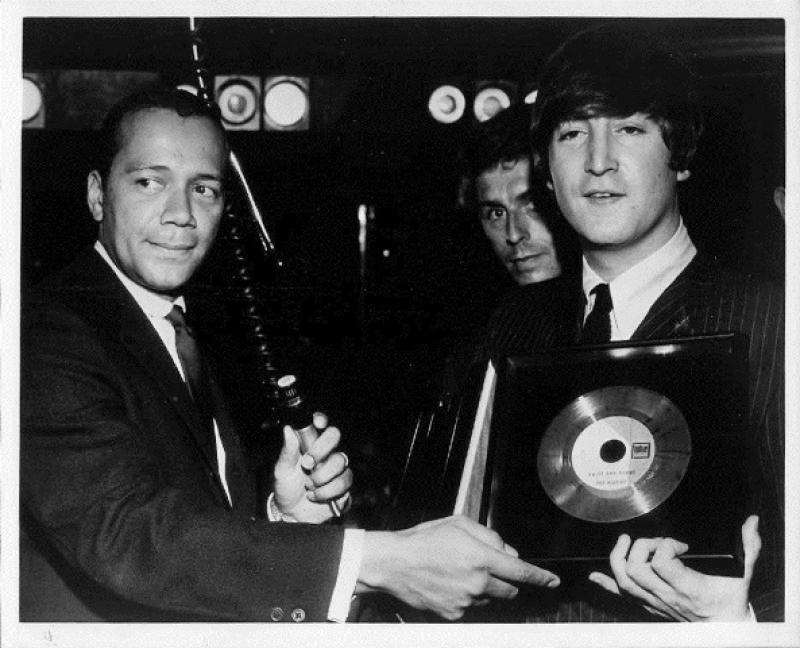

[Randy Wood, who became Vee-Jay’s president in the wake of Ewart Abner’s firing, presents a gold record to John Lennon]

[Randy Wood, who became Vee-Jay’s president in the wake of Ewart Abner’s firing, presents a gold record to John Lennon]

VI. The End Times

It’s a bittersweet tale if there ever was one. Just one month after releasing the first Beatles album in America, Vee-Jay abandoned Chicago for Santa Monica, and it would set the label on course toward its doom.

“We got the Beatles, and went from 15 or 20 employees to like 200 overnight,” Calvin Carter said. “The growth was just too fast. Everybody in there had a store of their own, there were lease cars all over the place, and it was just a bad job of managing. After we got the Beatles, they came up with a bright idea and all started trying to be grabbing stock. It was a Marx Brothers movie.”

Randy Wood was a fine record man in his own right, but his hopes of controlling the wobbling Vee-Jay behemoth from L.A. didn’t quite pan out. Some of the label’s top R&B acts had already left and signed with Ewart Abner’s new Constellation label, and the Four Seasons went to Mercury. The team in California did its damndest to sign new talent, stay profitable, and rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic (including the creation of more subsidiary labels like Tollie, Interphon, and Oldies-45), but the creative feud with Calvin and the Brackens had never been resolved, and the company’s whole reputation was collapsing under the weight of the ongoing disconnect.

Randy Wood was a fine record man in his own right, but his hopes of controlling the wobbling Vee-Jay behemoth from L.A. didn’t quite pan out. Some of the label’s top R&B acts had already left and signed with Ewart Abner’s new Constellation label, and the Four Seasons went to Mercury. The team in California did its damndest to sign new talent, stay profitable, and rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic (including the creation of more subsidiary labels like Tollie, Interphon, and Oldies-45), but the creative feud with Calvin and the Brackens had never been resolved, and the company’s whole reputation was collapsing under the weight of the ongoing disconnect.

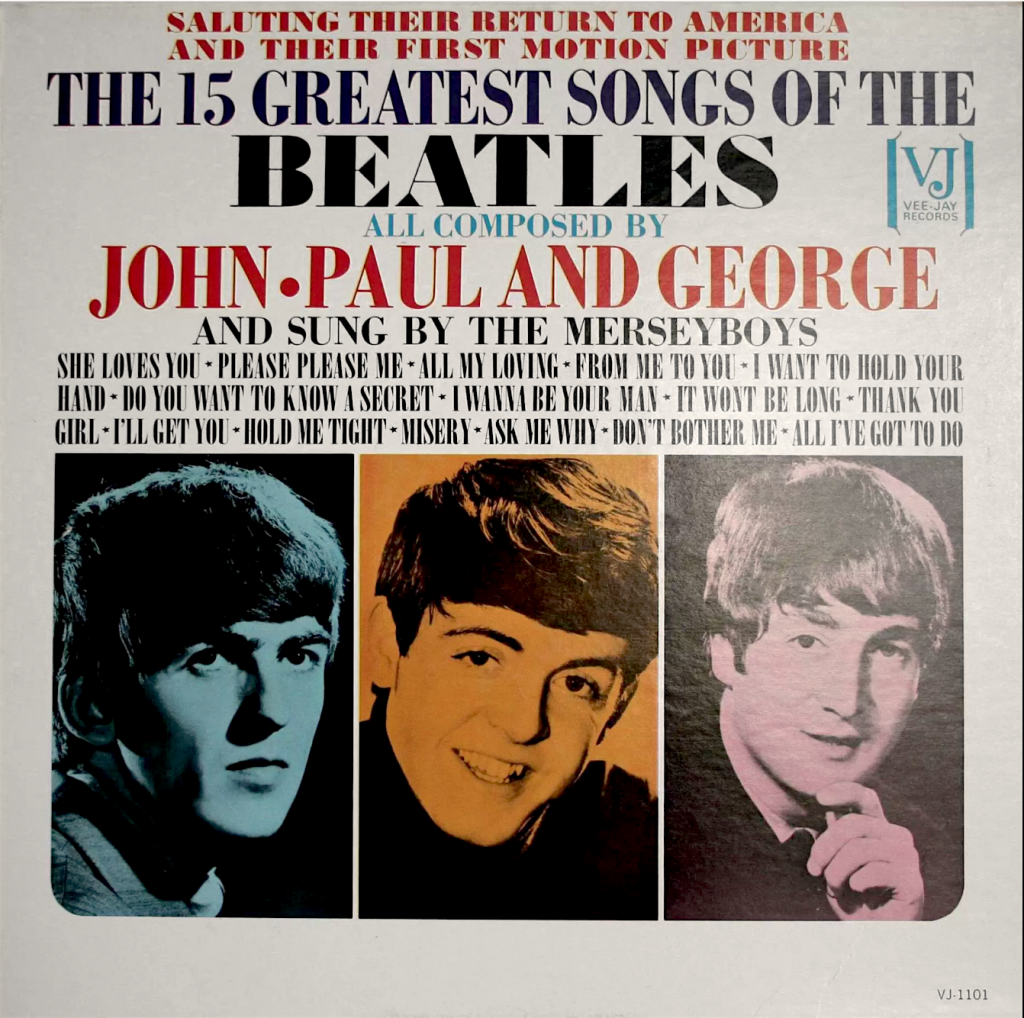

With no new Beatles material headed their way, Vee-Jay got embarrassingly creative in its efforts to squeeze every dime possible out of their mop-topped cash cow, too. They did several re-releases of the songs they already had, gussied up in new packaging, including bizarre combo albums with other acts that were marketed as faux collaborations—The Beatles & Frank Ifield On Stage (they weren’t together and the recordings weren’t live) and The Beatles vs. The Four Seasons. Maybe worst of all, there was VJ-1101: The 15 Greatest Songs of the Beatles— All composed by John, Paul and George . . . [fine print] and sung by the Merseyboys.”

Trying to trick young Beatles fans like my mom into buying some low-rent cover band’s record?! For shame.

[When is a Beatles record NOT a Beatles record? . . . When it’s sung by the Merseyboys]

[When is a Beatles record NOT a Beatles record? . . . When it’s sung by the Merseyboys]

Finally, a frustrated Jimmy Bracken had had enough of the nonsense. He swooped in and bought out the L.A. management group in 1965, re-installed Ewart Abner as general manager, and moved the Vee-Jay HQ back to Chicago. There was an exciting hope of putting everything back the way it was, and it seemed possible for a while. But there’s a reason people say “you can never go home again.” Not only was the company forever changed (and seemingly forever in debt), but the world was different, too. It was a rough crawl to the finish line.

Down to just a handful of artists, Vee-Jay officially closed its Chicago offices in May of 1966 and was liquidated by the end of the summer. The following year, the IRS even seized Vivian Carter’s record shop in Gary, which she had kept going through the entire Vee-Jay run. The Brackens’ fortune was effectively erased, and Vivian was left back where she started, hosting her radio show and playing records released by other labels.

Down to just a handful of artists, Vee-Jay officially closed its Chicago offices in May of 1966 and was liquidated by the end of the summer. The following year, the IRS even seized Vivian Carter’s record shop in Gary, which she had kept going through the entire Vee-Jay run. The Brackens’ fortune was effectively erased, and Vivian was left back where she started, hosting her radio show and playing records released by other labels.

Most of Vee-Jay’s assets were purchased after its bankruptcy (presumably for a song) by Randy Wood and another former company exec, Betty Chiappetta. This enabled the sale of the back catalog on a new imprint, Vee Jay International, in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, and also set the table for several re-launches of the brand in the decades that followed (to humble returns).

Clearly, it’s Vee Jay’s original run, from 1953 to 1966, that has held the attention of music historians. The label produced a treasure trove of great work (the vast majority of it recorded in Chicago at the Universal Recording Corp studio) that helped set the tone for the ‘60s music revolution. Sure, it might have turned into a “what if?” story in the end, but the what ifs would have been far more devastating without Vee-Jay’s contributions. Would we have still had the Impressions? Jimmy Reed? John Lee Hooker? The Staple Singers? The Four Seasons? . . . The Beatles?! . . . Okay, yeah, probably the Beatles. But nonetheless, respect.

[I suppose it’s 50 years too late at this point, but there really ought to be an apostrophe in “Englands”]

[I suppose it’s 50 years too late at this point, but there really ought to be an apostrophe in “Englands”]

[Jerry Butler, Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions perform “For Your Precious Love,” a VJ single in 1958]

Sources:

The Beatles Records on Vee-Jay, by Bruce Spizer, 2013

“The Vee-Jay Story,” by Mike Callahan (originally in Goldmine, 1981), see Online Version here

“UA Heritage: An Interview with Bill Putnam, Sr.,” by Larry Blakely, reprinted from Mix magazine. see Online Version here.

‘Biggest Little Giants in Disc Industry” – Ebony magazine, November 1961

“Beechwood Music Corporation v. Vee Jay Records, Inc.,” 226 F. supp. 8 (S.D.N.Y., 1964)

Doowop: The Chicago Scene, by Robert Pruter, 1996

Chicago Soul, by Robert Pruter, 1991

Cashbox, January 2, 1954

“Vee-Jay, Ex-Official Hit by Tax, Bribe Charges” – Jet magazine, June 16, 1966

Only the Strong Survive: Memoirs of a Soul Survivor, by Jerry Butler with Earl Smith, 2000

The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four, by Kenneth Womack

Indiana’s 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State, edited by Linda C. Gugin, James E. St. Clair

Archived Reader Comments:

“Some of the history I heard about through reading. Family members told me about Vivian was my grandmothers niece.. What is so amazing I was introduced to Ernie Lener years later and we dated before he passed…He was my significant other…Talk about full circle….” —Darlene, 2019

Do you know of anyone who can provide me with information about which Vee Jay company 45 sleeves or album inner sleeves were used with which 45s or albums?

For the 45s, it’s simple. Sleeves with the words Vee-Jay circling the center hole correspond to their oval logo, the “Singles of Significance” sleeves correspond to the releases with the brackets logo.

Releases during the maroon label years were always in generic brown paper sleeves.

Good afternoon. 1/what was the address of VJ’s pressing plant in St. Louis, Mo. 2/What caused label change from Rainbow to, Silver and Black? Thank you for such a wonderful insight into Vee Jay Records.

I remember going shopping at the mall for aqua net hair spray for the week. Had two cans in my hand and started looking at records and seen the new one out. The Beatles vs The Four Seasons. I put the hairspray back and had to buy the double LP. Can’t even remember how my hair held up for the week but remembered playing them LP’s and hanging pictures up.

Great article! I had only recently been researching another VeeJay artist, pianist Harold Harris, whose trio was featured during the Playboy Club’s early 60’s fame. I had wondered about Barbara Gardner, who wrote the liner notes “Here’s Harold” VeeJay release 3018 – now I know that she’s Barbara Proctor! Why hasn’t this story been made into a movie? Thanks.

This was a very well-written, well-presented & illustrated article that also made me laugh many times! (usually because captions underneath pics). Very well-done. I’m not new to this history, but I thoroughly enjoyed brushing up on it here, and picking up stuff I didn’t know, or didn’t remember. Thank you!

Hi,i’m Pagan Magda i’m writing from Italy. I own the Beatles album-introducing THE BEATLES England n’1 vocal group….-i would kindly like to know if it is counterfeit or not. I inherited the album from a relative who framed it .next to the disc there is a writing where it says that the disck is rare …. I would send you a photo….i would like you to contact me to be able to give me some information and to be able to send you the photo of the disc. Tank you in advance. Best regards. Pagan Magda