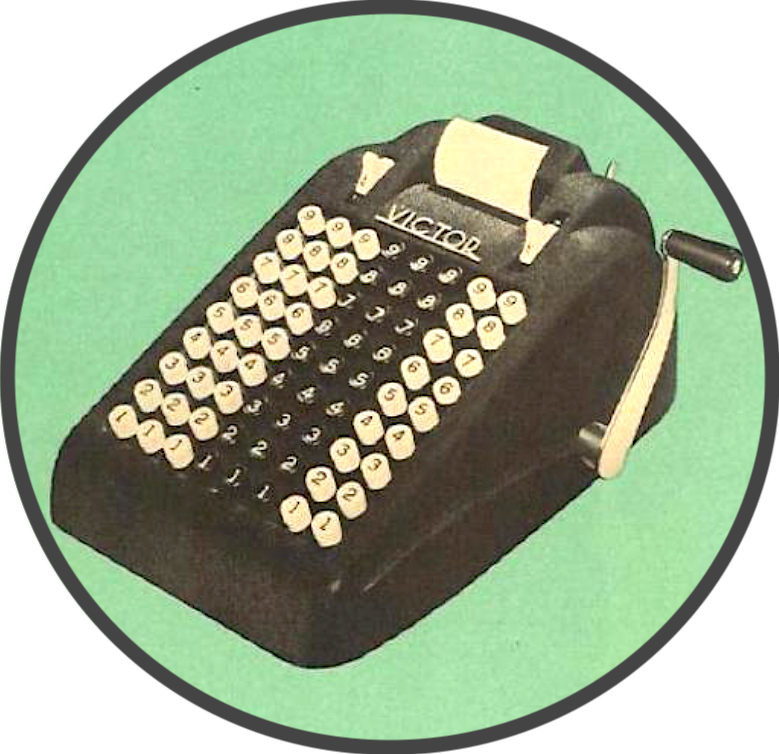

Museum Artifacts: Victor Adding Machines – Model 210 (c. 1925, donated by Robert Eichhorn) and 600 Series (c. 1939)

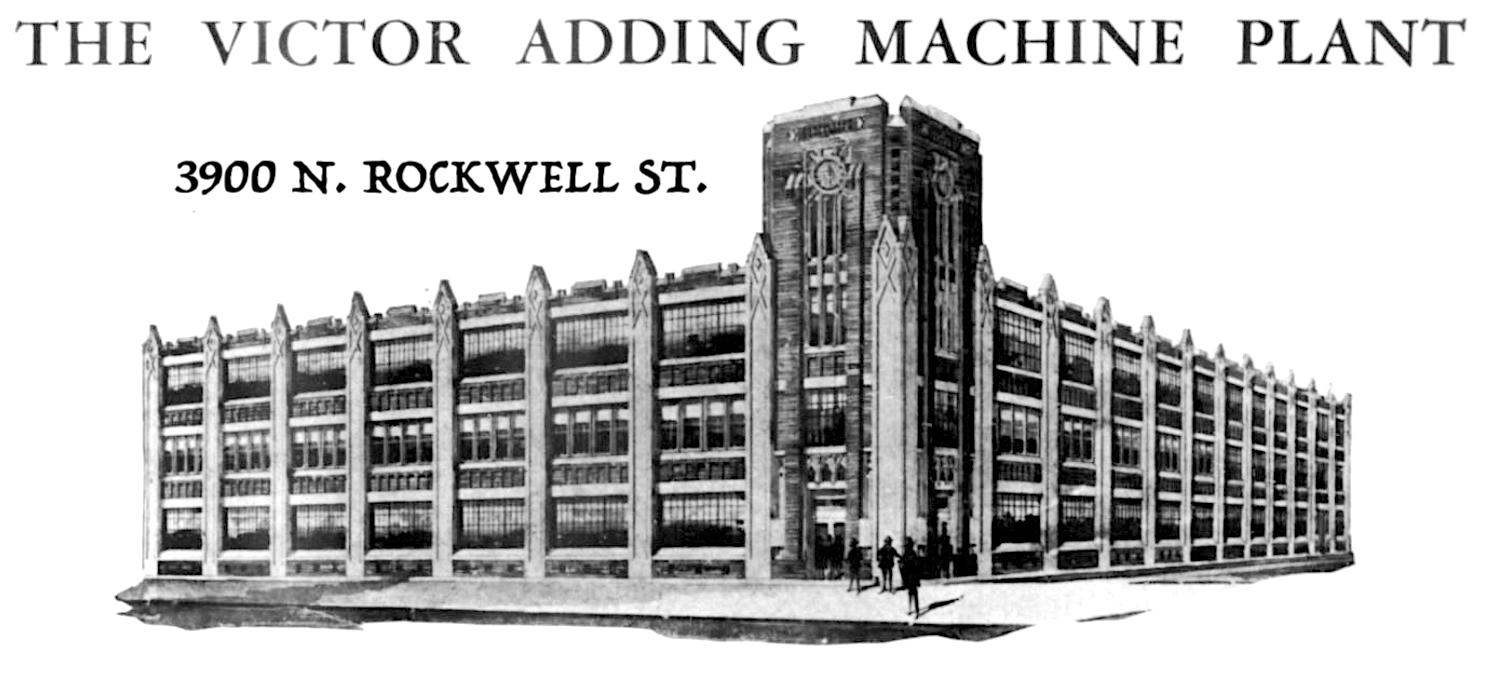

Made By: Victor Adding Machine Company, 3900 N. Rockwell St., Chicago, IL [North Center]

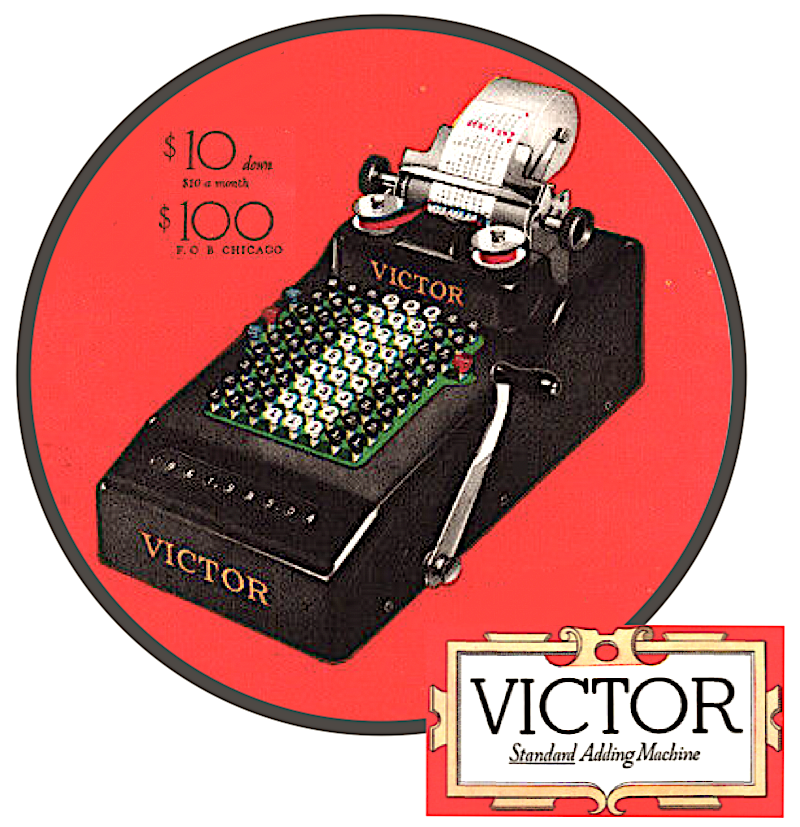

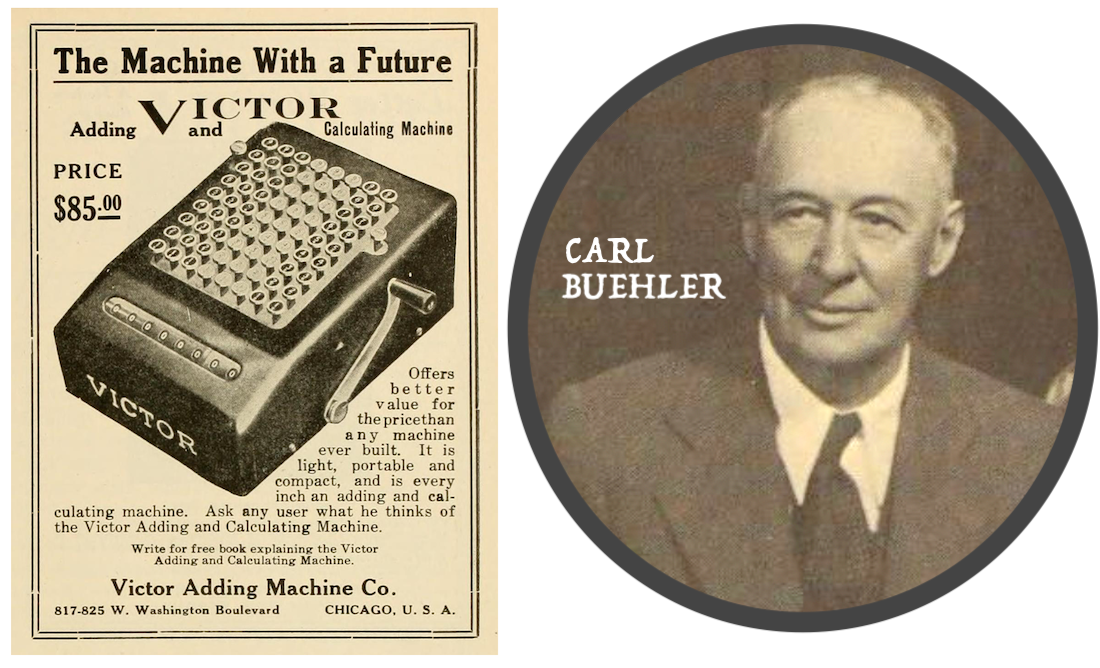

“The design of the VICTOR is a work of art, and has been pronounced by experts the most beautiful adding machine ever produced. It has about one-third the working parts ordinarily used in adding machine construction, and offers every up-to-the-minute feature known to modern adding machine efficiency . . . at a price within the reach of all.” –Victor Adding Machine advertisement, 1920

If every aspect of their functionality has long since been rendered obsolete, there should at least be no question, 100 years later, as to the enduring aesthetic appeal of the Victor adding machines in our museum collection.

If every aspect of their functionality has long since been rendered obsolete, there should at least be no question, 100 years later, as to the enduring aesthetic appeal of the Victor adding machines in our museum collection.

Believe it or not, one of the key selling points of these sleek beauties was their “lightweight” construction; bearing in mind that the 30-pound bulk of the early 1920s models was a bit of an improvement on the popular precursors on the market, including the early giant-sized Comptometers by Chicago’s Felt & Tarrant.

Over time, of course, Victor’s calculators evolved from industrial steel frames to bakelite and compact plastic casings. Likewise, the keyboards shed buttons and simplified while the speed and variety of different calculations improved as mechanical processes gave way to electrical. These changes were, in theory, good for business. But for the more observant engineers at Victor’s Chicago offices, everything was headed toward one inevitable conclusion; a point in time when a dedicated physical machine would no longer be needed for crunching numbers, and every sale would automatically record itself in one great big ledger in the clouds. Once that happened, the mighty Victor Adding Machine would no longer be a novelty of new technology. It would become the other kind of novelty . . . a curiosity; a desktop Model T. Even as a work of art, it would function more as a nostalgic visual prop, inspiring visions of sweaty Depression-era accountants clad in ill-fitting suspenders and tilted fedoras, smoke billowing from their ash trays while each plonky tap of a key, craaaank of the handle, and chirrup of unwinding paper slowly revealed the painful details of another financial shortfall.

Ironically, one could say that the Victor Adding Machine Company itself was founded on a miscalculation. Others might characterize it as a misunderstanding, or from another view, a bamboozling. Either way, it’s one of the stranger origin stories of any business profiled in the Made In Chicago Museum . . .

[This light-up Victor Adding Machines wall sign, circa 1950s, is also part of our museum collection]

History of the Victor Adding Machine Co., Part I: Buehler Meets Cheesman

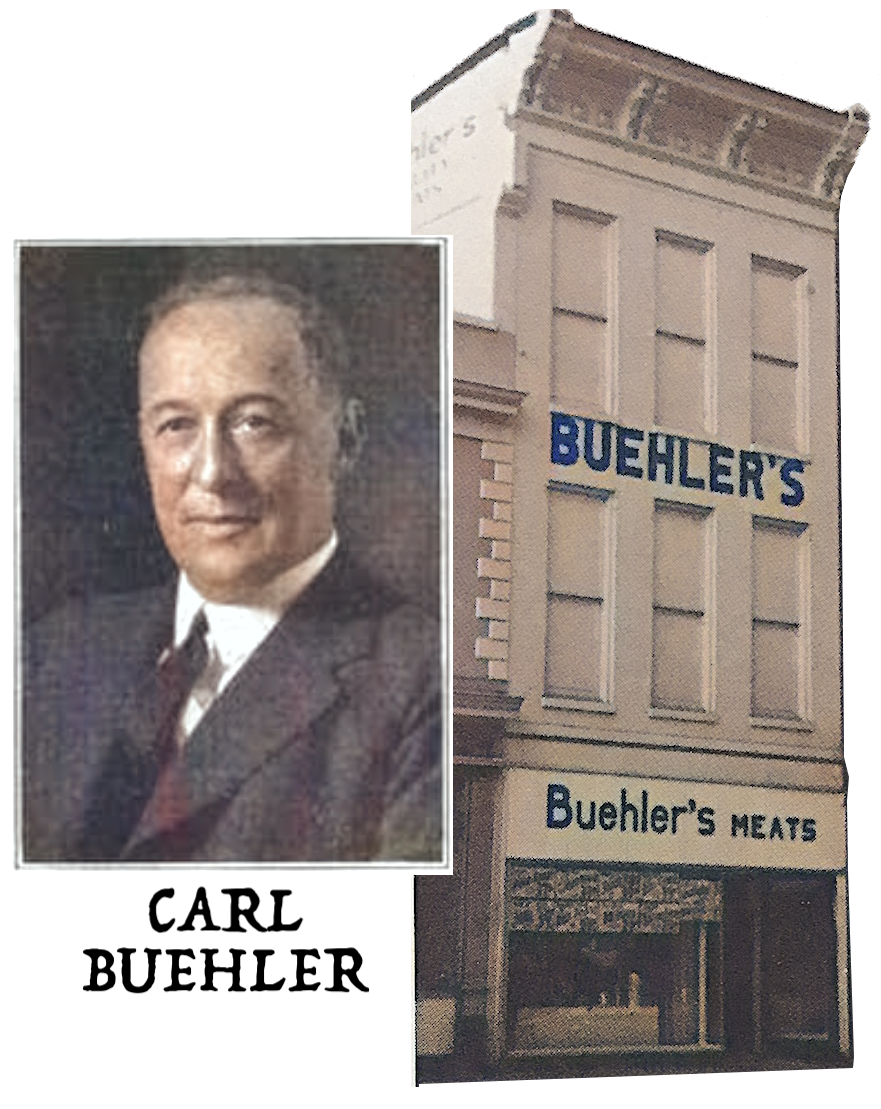

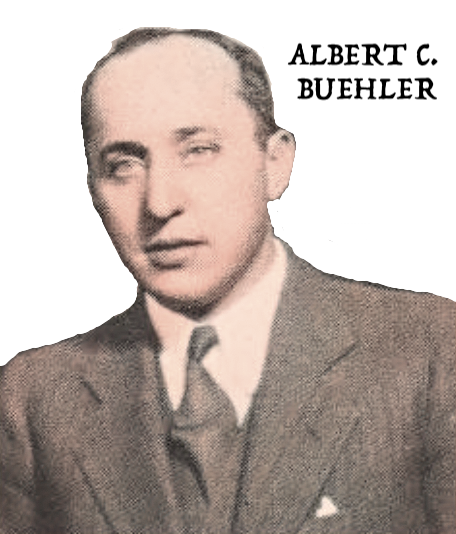

In the summer of 1918, according to lore, a salesman came to the door of the Buehler Bros. meat market on Lincoln Avenue, asking to speak with the owner of the joint. “You’re looking at him,” answered Carl Buehler.

“Ah, pleasure to meet you then, my good man,” said the salesman. “The name’s O. E. Cheesman [tips his cap]. I’m stopping by today to see if you’re satisfied with the current state of the adding machine in your establishment.”

Carl Buehler was no gullible Gus. Already a tick over the age of 50, he’d worked with his two brothers to establish one of the first legitimate grocery store chains in the country, with dozens of locations across the Midwest—from Cleveland to Kalamazoo, Peoria to Duluth [the one pictured here was in Springfield, Ohio]. His keen business instincts would normally tell him not to trust a fella named Cheesman, but as the fates would have it, Carl was actually desperately in need of a good tabulating device of some sort.

“Truth is, I don’t own one,” he told the salesman, explaining that he generally did his record keeping the old fashioned way, with a pen and a pad + some quick mental math.

“Well, sure, the brain can toss around some figures,” chimed Cheesman, “but my investors and I feel we’ve done it one better. I’m talking lickety split addition; huge inventories handled in a few quick strokes. Always accurate! Easy to operate! Lightweight! The brand new Victor Adding Machine is the cat’s pajamas!”

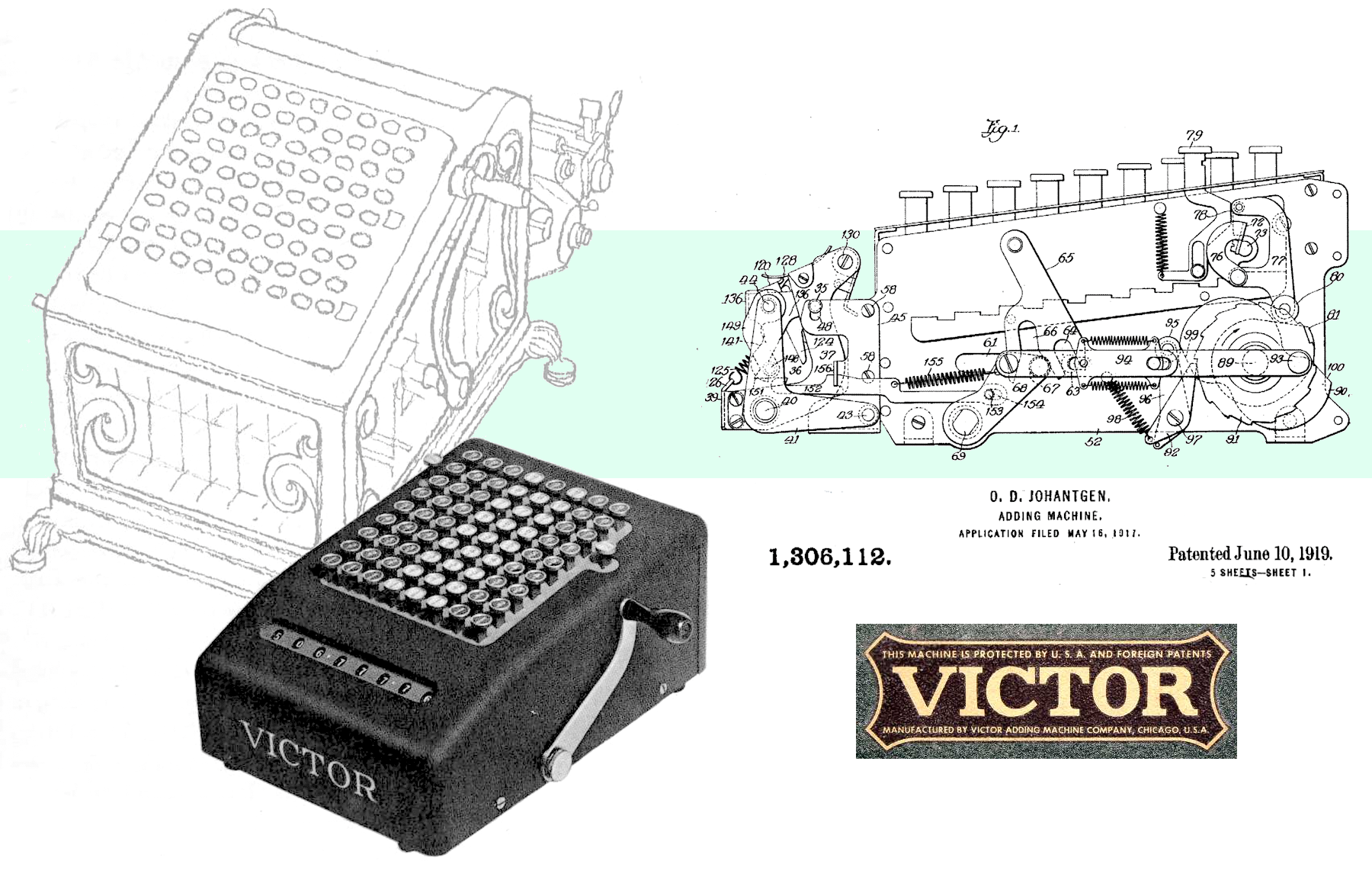

[The first Victor adding machine, developed in 1917 and patented in 1919, was only “lightweight” (35 LB) in comparison to some of the other giant 100+ LB calculator consoles of the 1910s, as represented in the background sketch above.]

Seduced by visions of efficiency, Carl Buehler agreed to a simple transaction. He’d hand over $100 for one of these newfangled magic number processors. Since most comparable machines of the day were selling for nearly twice that price, it sounded like a bargain.

“Hot dog! It’s a deal,” said Cheesman.

Sure enough, just a few days later, Buehler got what he’d paid for—only it wasn’t an actual adding machine, per se. It was a certificate—sent by mail—for 10 shares of Victor Adding Machine Company stock.

At first, Buehler was rightly miffed. He’d been hoodwinked by that sly cheese man. The more he thought about it, however, Carl decided he had more to gain by seeing how this new “investment” played out, rather than cutting bait at square one. . . . It wound up being a life changing decision.

II. V, as ever, for VICTOR!

By December of 1918, Carl Buehler was suddenly and unexpectedly knee deep in the add machine business. At a gathering of Victor stockholders, he spoke again with O.E. Cheesman, while also meeting the two key figures behind the company’s creation—investor George Eldred (who was also Cheesman’s brother-in-law) and the brains behind the whole operation, inventor Oliver D. Johantgen.

A farmboy from the small town of Oregon, Indiana, Johantgen had been working on this project obsessively for more than 20 years, despite never earning enough money to require the sort of math his machines provided. His first prototype was built in 1903, but it took another 15 years to convince a dedicated investment group (Eldred and Cheesman) to go all-in and get a charter to start a company. They called it “Victor,” even though it was arguably the single most overused brand name in America.

While everybody involved in the enterprise seemed plenty intelligent and ambitious, Carl Buehler was clearly the only one in the room with proven experience running a business. As such, he was voted president of the fledgling company just months after he’d accidentally purchased stock in it.

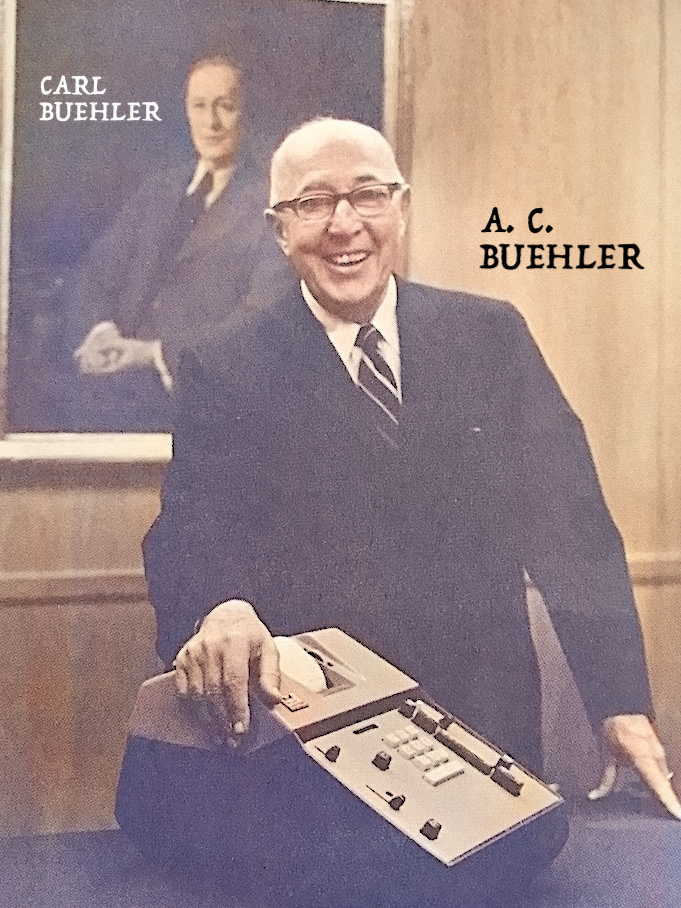

According to Carl’s son A.C. Buehler, his dad accepted the offer not just because he saw the potential in a portable, affordable adding machine, but because he simply relished a challenge.

“Dad seemed to have the ability to reason out how things could work,” A.C. recalled in a 1968 interview for the book, It All Adds Up: The Growth of Victor Comptometer Corporation. “He had a knowledge of people and their characteristics and their thinking. His basic premise was to try to satisfy the customer—to give good value at a low price. Businessmen didn’t always think that way. The old idea was to sell a few products at a high price to the top of the economic pyramid. But dad understood that the further down you go on the pyramid, the bigger the market; so if you could give a good value and get the price down very low, you were going to sell more.”

That was a philosophy Buehler had developed in his meat market business, and he saw no reason it couldn’t carry over to clunky little number crunchers.

By 1921, with Buehler personally keeping it financially afloat on his own dime, Victor slowly started gaining ground on its cumbersome, more expensive competitors—not only by offering high-end clients a more advanced machine, but by targeting middle-class customers whom other calculator companies weren’t even bothering with: mom-and-pop shop owners, small-time clerks and accountants, you name it.

In a move that surprised many within their own family, Carl Buehler also named his eldest son—the pint-sized 24 year-old Albert (A. C.) Buehler—as Victor’s general manager, believing the kid could do more good with the upstart tech company than he could for the far more profitable and established Buehler Bros. grocery business.

In a move that surprised many within their own family, Carl Buehler also named his eldest son—the pint-sized 24 year-old Albert (A. C.) Buehler—as Victor’s general manager, believing the kid could do more good with the upstart tech company than he could for the far more profitable and established Buehler Bros. grocery business.

The first obstacle was just making sure the product was worth everyone’s time.

In the early years, the Victor Company was nomadic, renting space in a few different locations (including 817 W. Washington Blvd., 3045 Carroll Ave., and 319 N. Albany Ave.), and fielding a team of less than a dozen workers. Oliver Johantgen, along with being the inventor of the machine, was also in the office every day as the final inspector—making sure any flaw was accounted for.

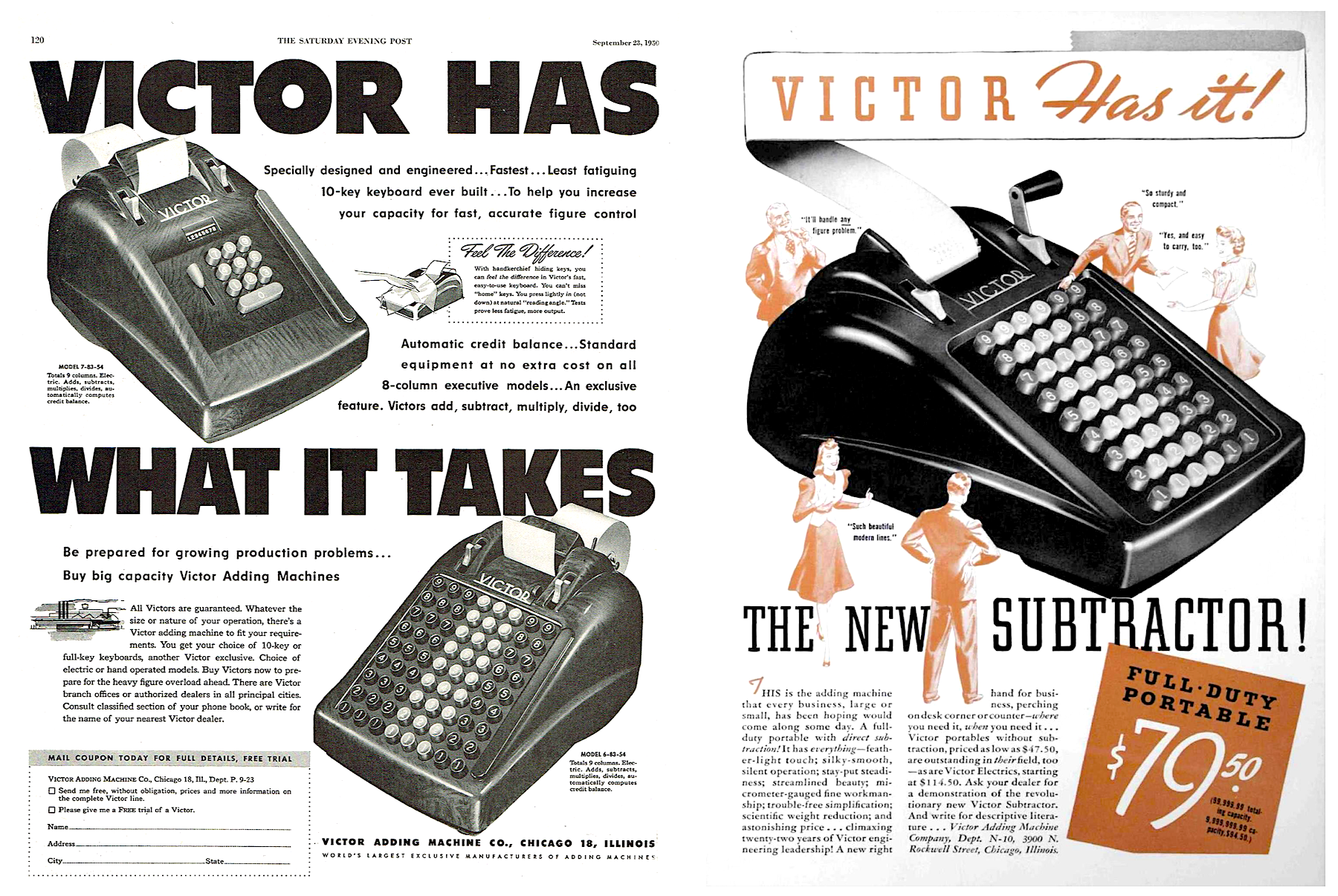

Johantgen and his pals were all gambling on the clear selling points that separated his adding machine from the old guard. The original Victor 110 model weighed far less than standard machines of the day (35 LBS vs 100 LBS), contained far fewer components (about 1,250 vs 2,500+), and could be built affordably on modern screw machines and punch presses, rather than old fashioned casting and milling. The Buehlers also settled on keeping the price tag at a solid $100—same as an average working man’s typewriter of the day, but far less than most commercial adding machines.

Competitors like Chicago’s Felt & Tarrant MFG Company tried to turn the Victor machine’s pros into cons, suggesting a light, sleek machine was also weak and vulnerable to breakdown. The Buehlers worked to refute those claims, while also encouraging Johantgen to redesign the model 110 with all the best modern features. It had to be a “listing” machine (one that prints out paper readouts) and needed an eighth column added to the numbered, push-button keypad. Johantgen complied, but the process was frustrating.

[1922 newspaper advertisement for “The Victor” featuring a similar model to the one in our museum collection]

“Our facilities for manufacturing at this time were very poor and we, therefore, had considerable trouble, both mechanical and financial,” Johantgen said in 1929. “But as Mr. Buehler always came to our rescue with the necessary cash, we were finally able to overcome our mechanical troubles and began to make a little money about 1922.”

Besides putting up the capital, Carl Buehler also knew how to get the most out of his employees. “Give a man a job to do,” he would say, “treat him with respect, recognize him when he does a good job, and let him make some money, too.”

The Victor sales team (which was fronted by F.B. Willis after Mr. Cheesman sold his shares) utilized innovative techniques, including bringing the actual machines door-to-door (instead of photos), and offering incentives like full refunds or free repairs for damaged devices. This sounded like a great perk to buyers, but from the Victor perspective, they were building such a smooth-running machine that those supposed repair, maintenance, and refund costs would actually amount to a sliver of their total budget.

III. A New Home

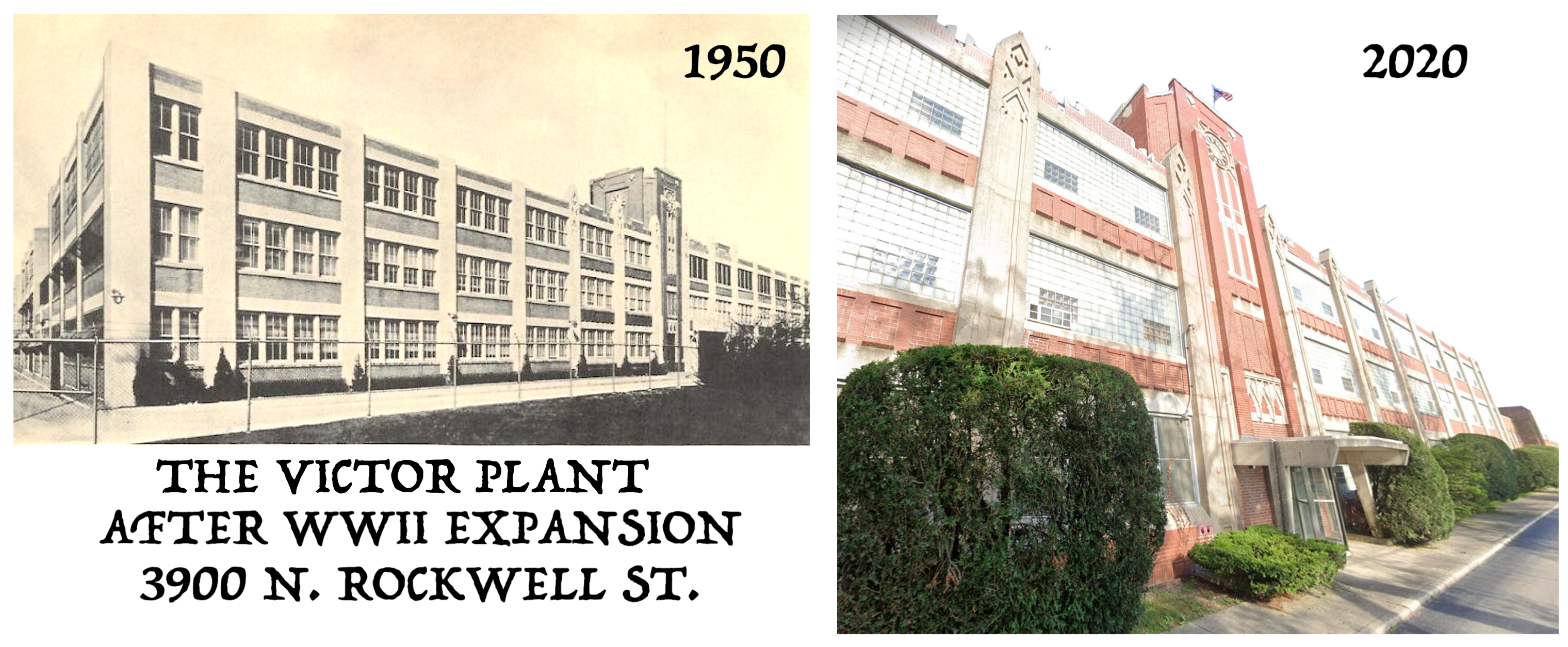

Come 1925, Victor had sold more than 100,000 machines into circulation, and they’d also finally managed to move into their own permanent factory space at 3900 N. Rockwell Street in what is now Chicago’s North Center neighborhood.

With a new 100,000 square foot facility secured, Victor started testing the limits of their business model.

With a new 100,000 square foot facility secured, Victor started testing the limits of their business model.

“In business you’ve just got to take chances,” A.C. Buehler said in 1968. “Sometimes you go wrong, of course. But you just have to keep trying, that’s all. I only know one way and that is to make a decision and then really to work and try to make it succeed. I figure if you’re 60 to 70 percent right, then you’re doing about as well as anyone can expect. Then you only have 30 to 40 percent to change. That’s when you take a new look, adjust your thinking, and go to work correcting your mistakes.”

There were a few mistakes along the way, indeed. In the mid ‘20s, Victor tried to break into the typewriter market with a lightweight design that seemed, logically, to have the same appeal as the Victor adding machines. It flopped. Overall sales were taking a hit by 1928, as well.

But like Hack Wilson down the road at Wrigley Field, A.C. Buehler also hit plenty of homeruns. He had helped forge a deal with the McCaskey Register Company of Alliance, Ohio, to use Victor adding machines as part of the McCaskey cash register design— a major coup. Similar unions were formed as A.C. hit the pavement across the country, making connections with dealers and distributors. Victor even went international, striking a deal with the Heissel Freres firm in Paris for distribution.

Things were looking more promising by 1929, as Victor’s new 310S and 320S machines ushered in the fancy-pants new subtraction function as a selling point. When the stock market crashed that October, however, the Victor Adding Machine Co. found they had to use those subtract buttons a bit more than they’d bargained for.

The company unveiled its advanced electric 500 series in 1931, greatly improving the quality of the product while keeping prices level. But their new competition was coming from an unexpected source. America’s shuttered businesses were selling off their old office equipment on the secondary market, and old Victor models could now be had on the cheap. For the first time, the company was losing money.

“The prospects for the coming year are difficult to forecast,” Carl Buehler told investors in 1931. “Adding machines are not vitally essential for the average business. At least, new equipment is not necessary until expansion programs are put into effect. And then only until such plans are well underway can we hope for such improvement. In the meantime, we will sit tight, cut expenses wherever possible, and wait for business to revive.”

“The prospects for the coming year are difficult to forecast,” Carl Buehler told investors in 1931. “Adding machines are not vitally essential for the average business. At least, new equipment is not necessary until expansion programs are put into effect. And then only until such plans are well underway can we hope for such improvement. In the meantime, we will sit tight, cut expenses wherever possible, and wait for business to revive.”

The following year, Carl Buehler died at the age of 66. As if that weren’t enough of a blow for his son to suffer, Victor’s mechanical genius Oliver Johantgen died the same year at just 57.

It was a turning point in Victor’s history, as both production and optimism were sitting at a low. With the company’s founders gone, 35 year-old A. C. Buehler certainly could have read the tea leaves and looked for the cheapest possible escape route out of the situation. Victor was still a relatively young company at the time, and its future was never guaranteed. Nonetheless, as a self-described chance taker, A. C. opted to carry forward, even amid some strategic disagreements with his younger brothers, who were also on the company board. In the short term, the focus was put on survival; not just of the business, but of the workers struggling to get by in the midst of the Depression.

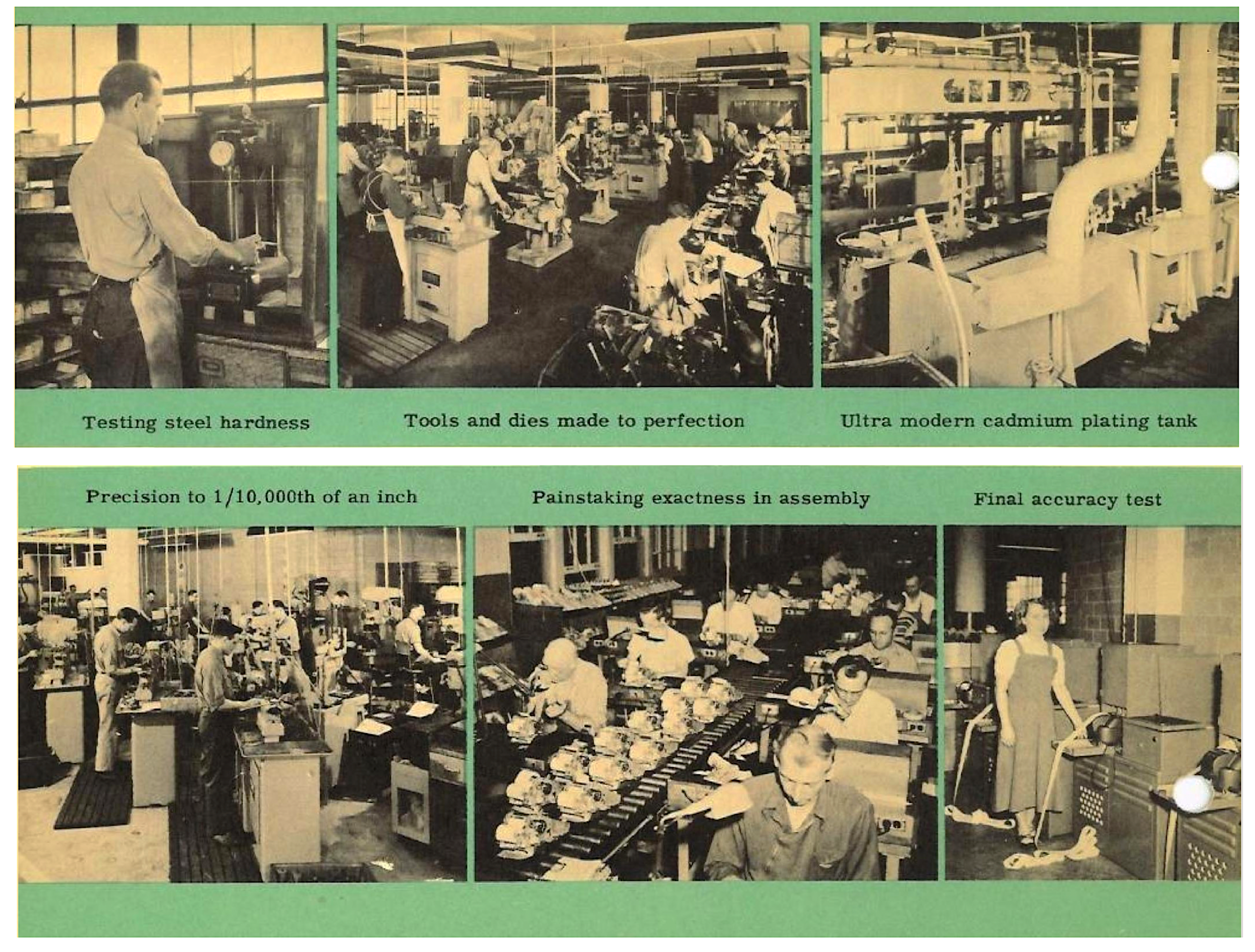

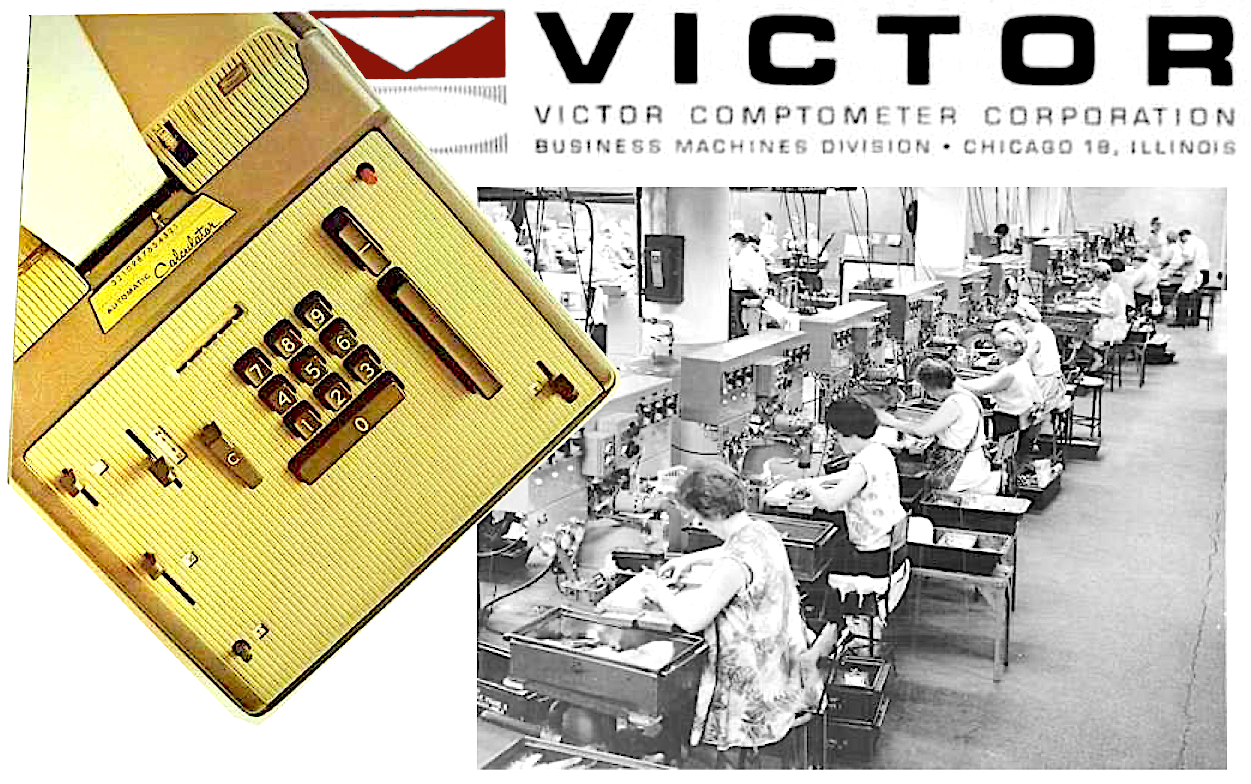

[Workers inside the Victor factory at 3900 N. Rockwell, circa 1940s]

“They tried their best for us,” one former employee recalled in the 1968 company history, It All Adds Up. “The works manager himself used to come over to our home and pick me up just so I’d be able to get in a few hours of work. They’d also send people around to the homes to find out if people needed any help. If we had debts, they’d help you figure out a way to pay them off, and they’d pay them off too. Then you repaid the company whenever you were able to. At work, soup and coffee were served free to the employees, and they set up a way we could get Buehler Bros. meat at the plant at wholesale prices.”

A. C. Buehler eventually set up an employee profit sharing plan, as well; one of the first modern types of its kind in Chicago. The plan, which was in the works towards the end of the Depression, was scheduled for a formal launch at a company-wide banquet at the Edgewater Beach Hotel on December 8, 1941. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor the day prior, the decision was made to carry on with the event anyway, as a show of support and solidarity. The faces in the crowd that night, however, reveal some of the new uncertainty of the moment.

[Victor employees gather at the Edgewater Beach Hotel at the launch of the company’s profit sharing plan on December 8, 1941. The event was a bit less joyous than intended, coming one day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.]

IV. Bargains and Bombsights

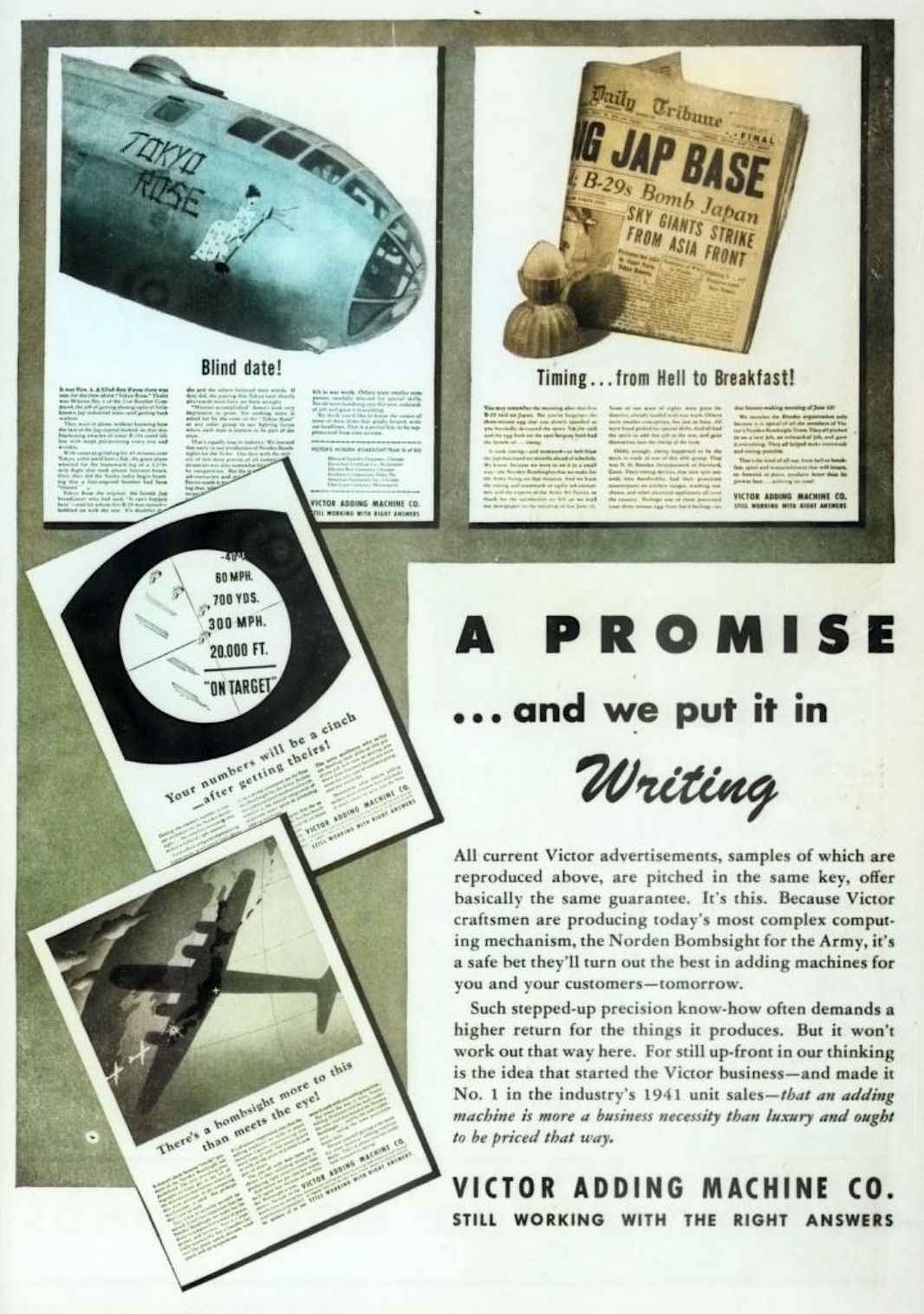

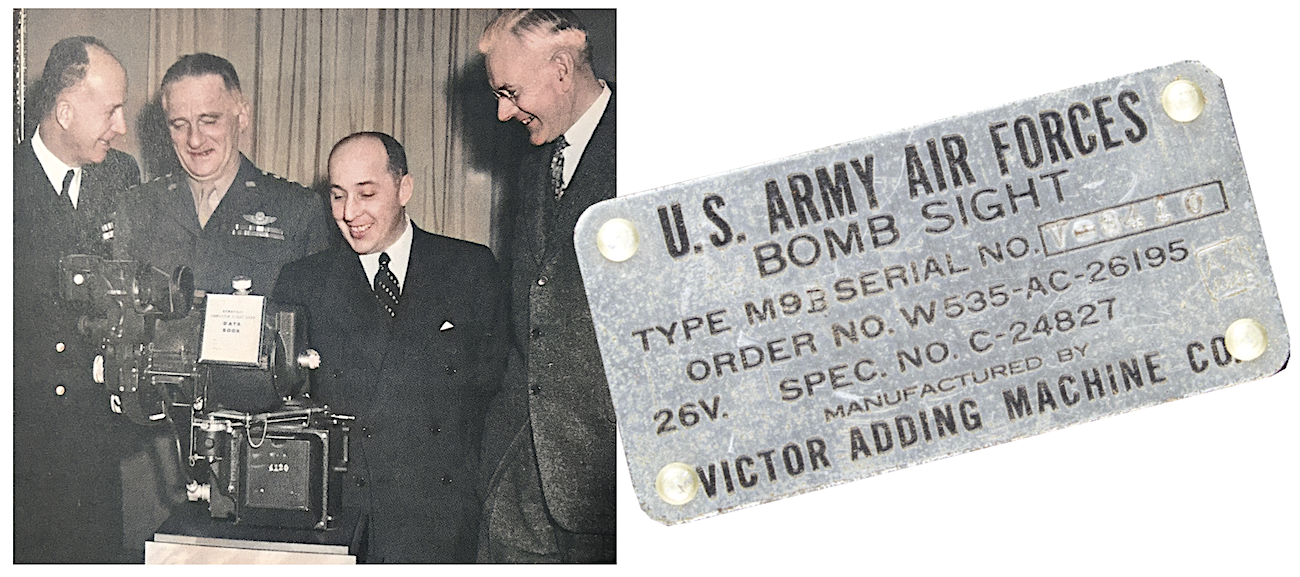

“Because Victor craftsmen are producing today’s most complex computing mechanism, the Norden Bombsight for the Army, it’s a safe bet they’Il turn out the best in adding machines for you and your customers . . . tomorrow.” –Victor advertisement, 1945

By looking out for its employees during its times of financial struggle, the Victor Adding Machine Company eventually found itself with a loyal, enthusiastic, and rapidly growing workforce once the script dramatically flipped from the late ’30s through the 1940s. While sales had already started to bounce back before the outset of World War II, Victor was certainly one of the many companies that experienced a financial windfall in wartime.

By looking out for its employees during its times of financial struggle, the Victor Adding Machine Company eventually found itself with a loyal, enthusiastic, and rapidly growing workforce once the script dramatically flipped from the late ’30s through the 1940s. While sales had already started to bounce back before the outset of World War II, Victor was certainly one of the many companies that experienced a financial windfall in wartime.

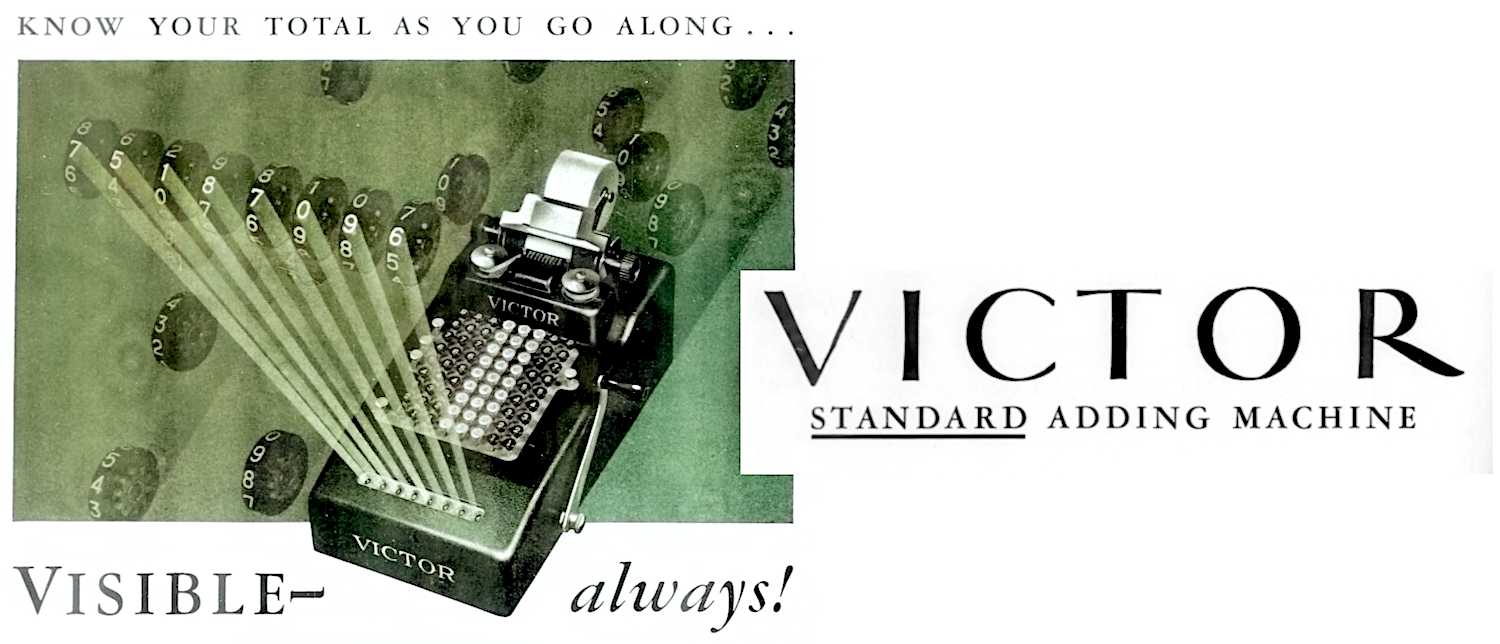

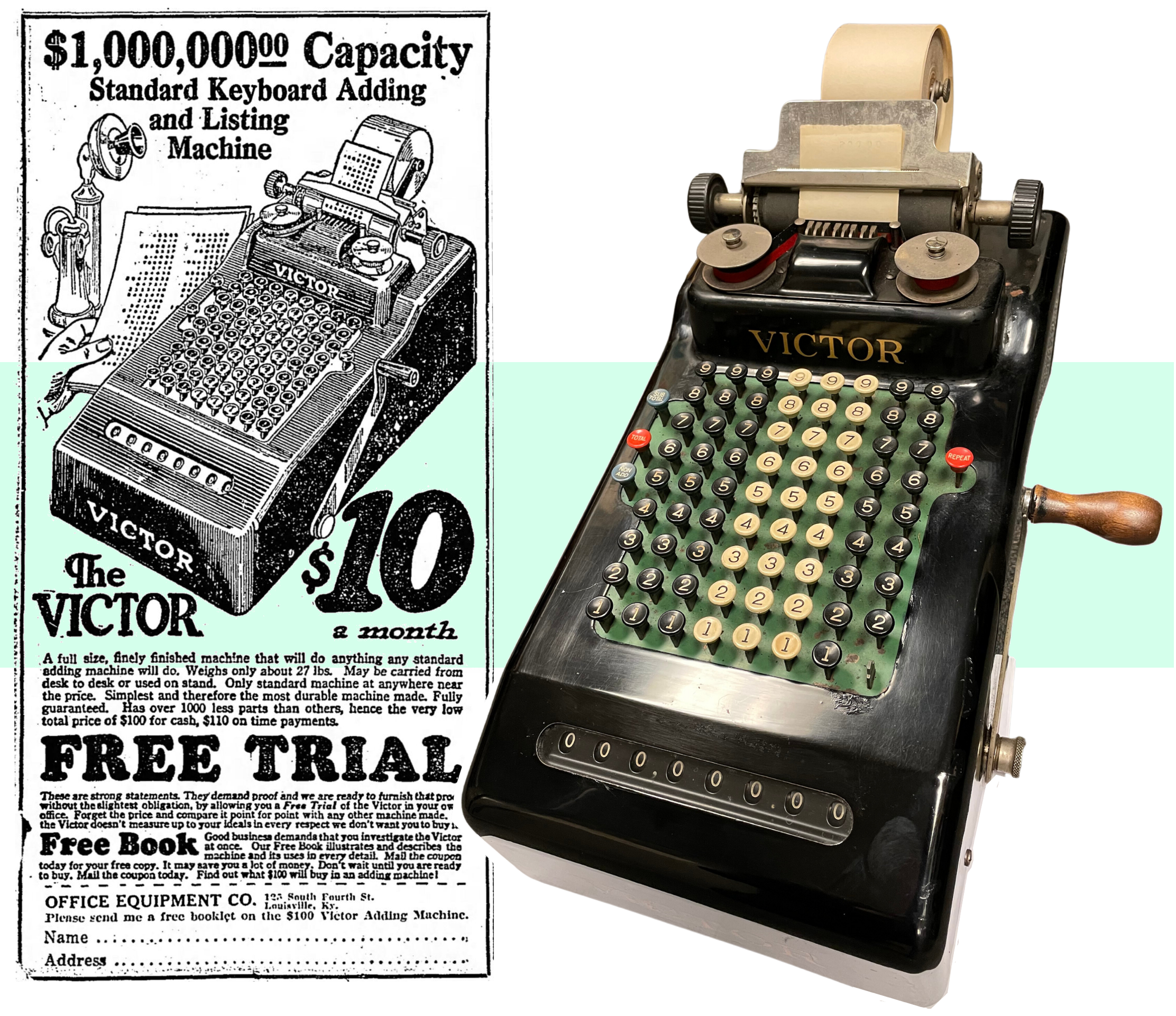

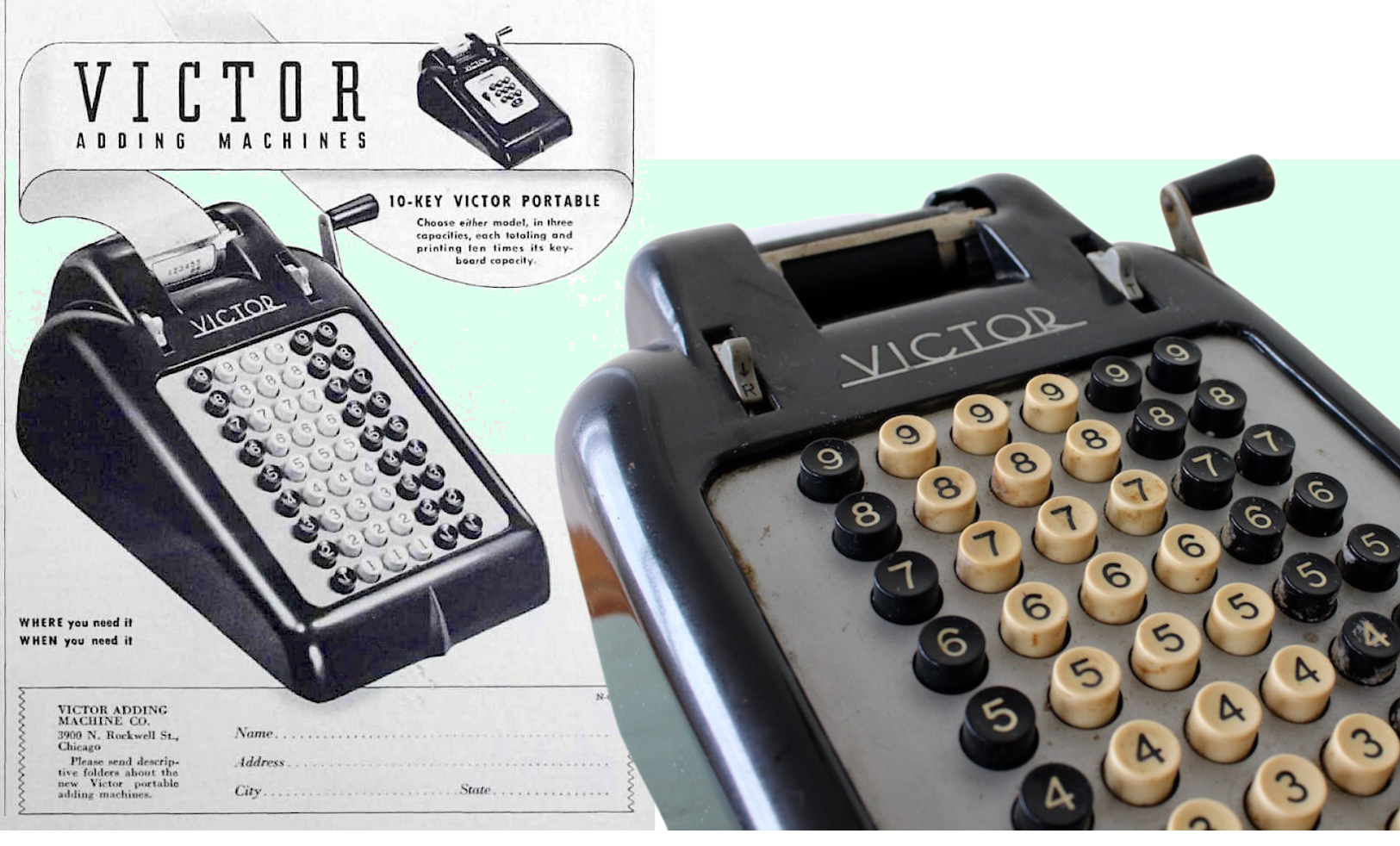

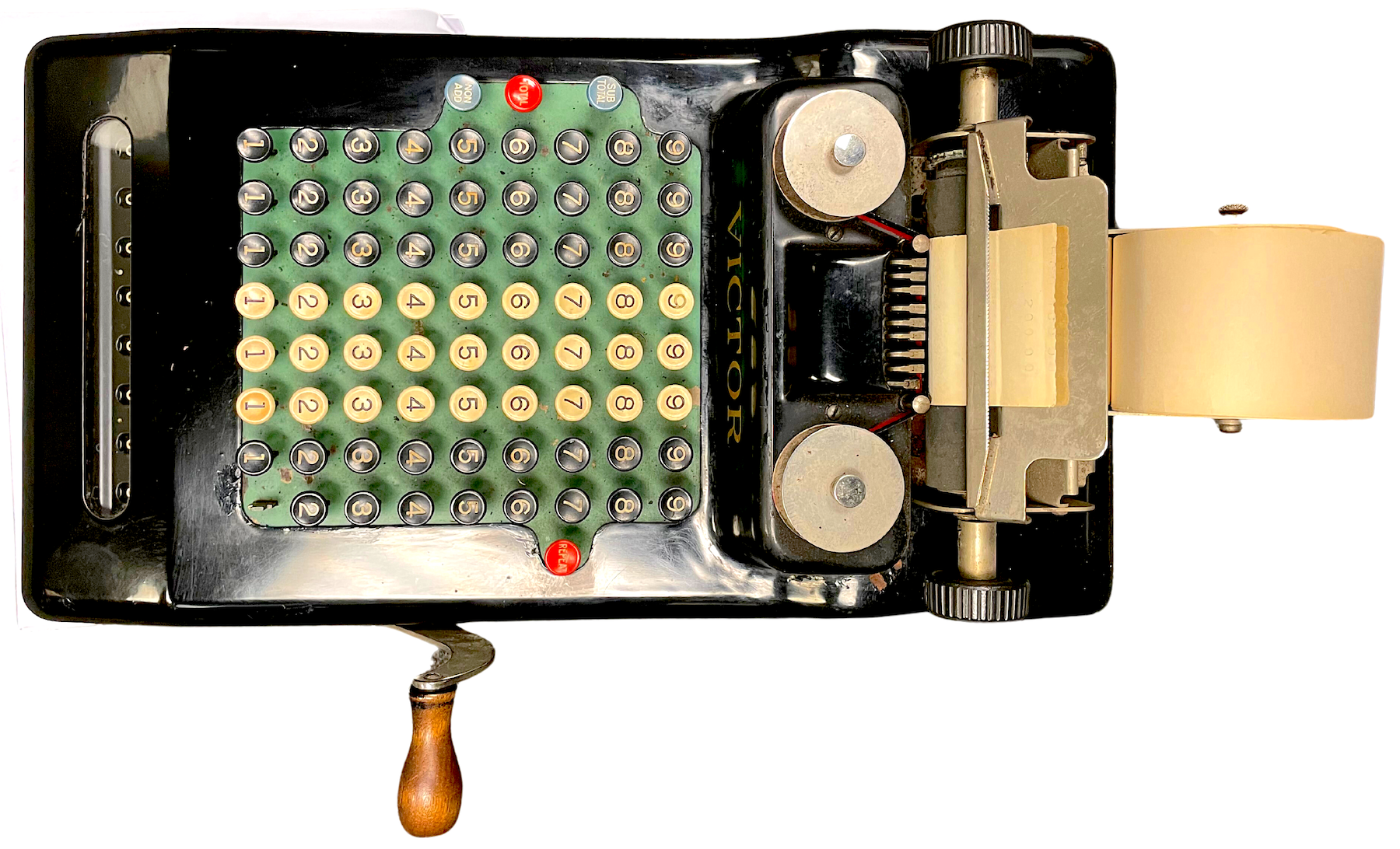

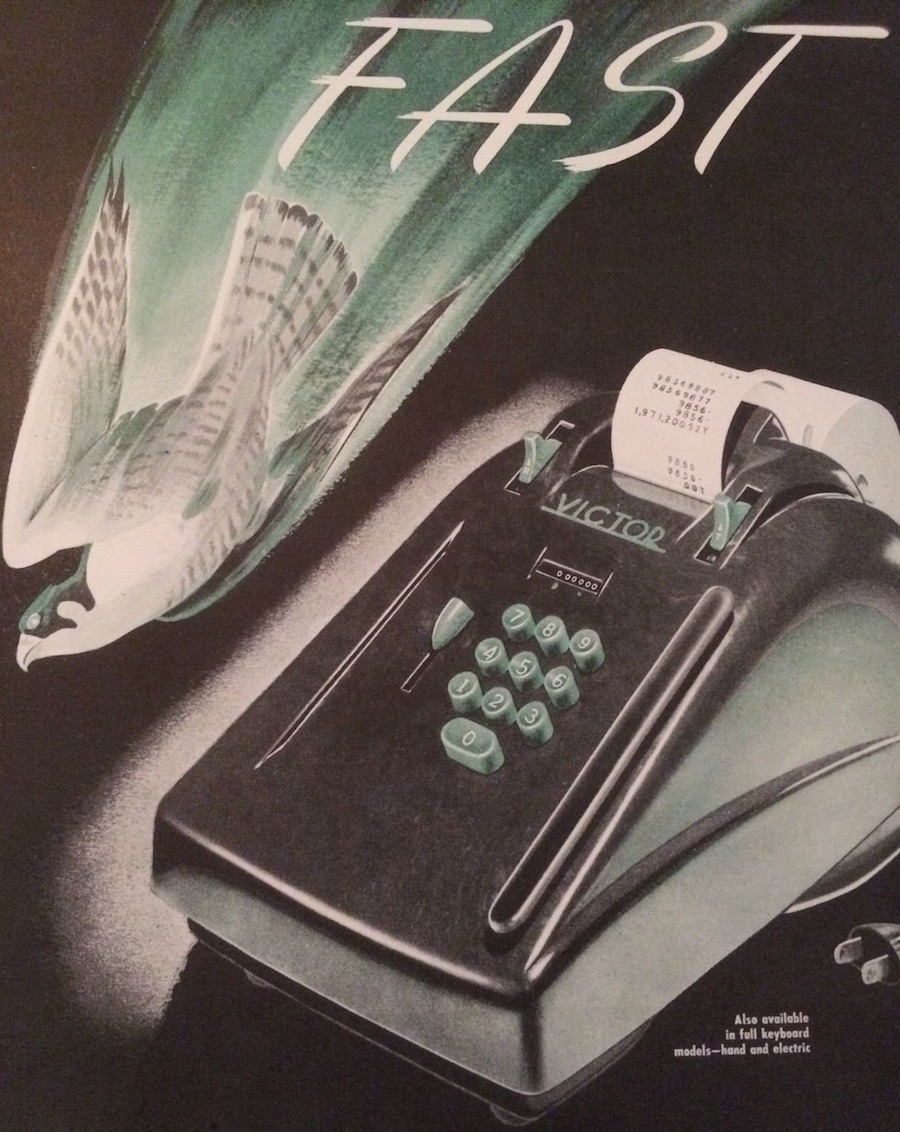

Part of this was the consequence of a rejuvenated research & development team, as A.C. Buehler had replaced the late Johantgen with another accomplished lifelong calculator machine junkie, Thomas O. Mehan (previously the inventor of the old “Brennan” machine). Just ahead of the war, Mehan rolled out the versatile Victor 600 and 700 series. One of the machines in our collection is a 600 model from around this period, featuring a full 6-column keyboard, no dial-wheel register, and the lightest weight achieved yet: less than 9 LBS! It sold in 1939 for around $50, or roughly $1,000 when adjusted for inflation.

Mehan’s slick modern designs captured the interest of a whole new generation of number crunchers, but the machines were marketed basically the same way every Victor model had been since the beginning.

[Left: 1940 advertisement for the 600 series Victor. Right: The same machine, as seen in our museum collection.]

“Cut your operating costs,” read one 1940s ad for the Victor 600. “Eliminate long hours of hand figuring. Anyone can operate. Small, compact, easy to move anywhere. Precision-built, like fine watches. Strong and sturdy. Made by the World’s Largest Exclusive Manufacturers of Adding Machines.”

During the war, of course, it would prove far more difficult for Victor to remain “exclusively” a manufacturer of adding machines, although the Allied Forces certainly had plenty of uses for the company’s primary product.

“Thousands of figuring machines made by the Victor Adding Machine Company of Chicago have gone to war,” Office Appliances magazine reported in 1945, “landing on the beachheads and in the front lines. These machines are especially packed for amphibious landings, where they are thrown into the water from landing craft and are later picked up when the tide goes out.”

“Thousands of figuring machines made by the Victor Adding Machine Company of Chicago have gone to war,” Office Appliances magazine reported in 1945, “landing on the beachheads and in the front lines. These machines are especially packed for amphibious landings, where they are thrown into the water from landing craft and are later picked up when the tide goes out.”

Like so many other Chicago manufacturers, Victor’s Rockwell Street plant also took on substantial military contracts outside their usual areas of expertise. And it was these arrangements that proved the most impactful for both “the cause” and the future financial standing of the business.

[The former Victor building is still standing today and looks largely as it did in its heyday]

In order to meet the demands of its new defense contracts, A.C. Buehler’s roster of workers grew from around 350 to over 1,400 during the war, and the plant was significantly expanded. Due in part to the company’s solid reputation with “figuring” instruments, it was given a critical role in producing bombsight devices for the U.S. Air Force—including the Norden design that would eventually be used by the Enola Gay above Hiroshima.

“Starting with two sample bombsights, the company set about making blueprints, getting special machinery, building new plant facilities, and training hundreds of men and women to carry out the highly skilled production job,” the Tribune reported in 1945. “For successful achievement of that production job at which others had failed, the Victor Adding Machine company next Monday will be given the Army-Navy ‘E’ [award of recognition].”

[A.C. Buehler (third from left) presenting the Enola Gay’s bombsight 4120 to the Smithsonian Institute in 1947]

V. Victor + Comptometer

“All that is quality stands out in what Victor prefers to call Character Construction. Strength of character in each and every part and in each and every finished machine is the objective.” –The Victor Story sales guide, 1952

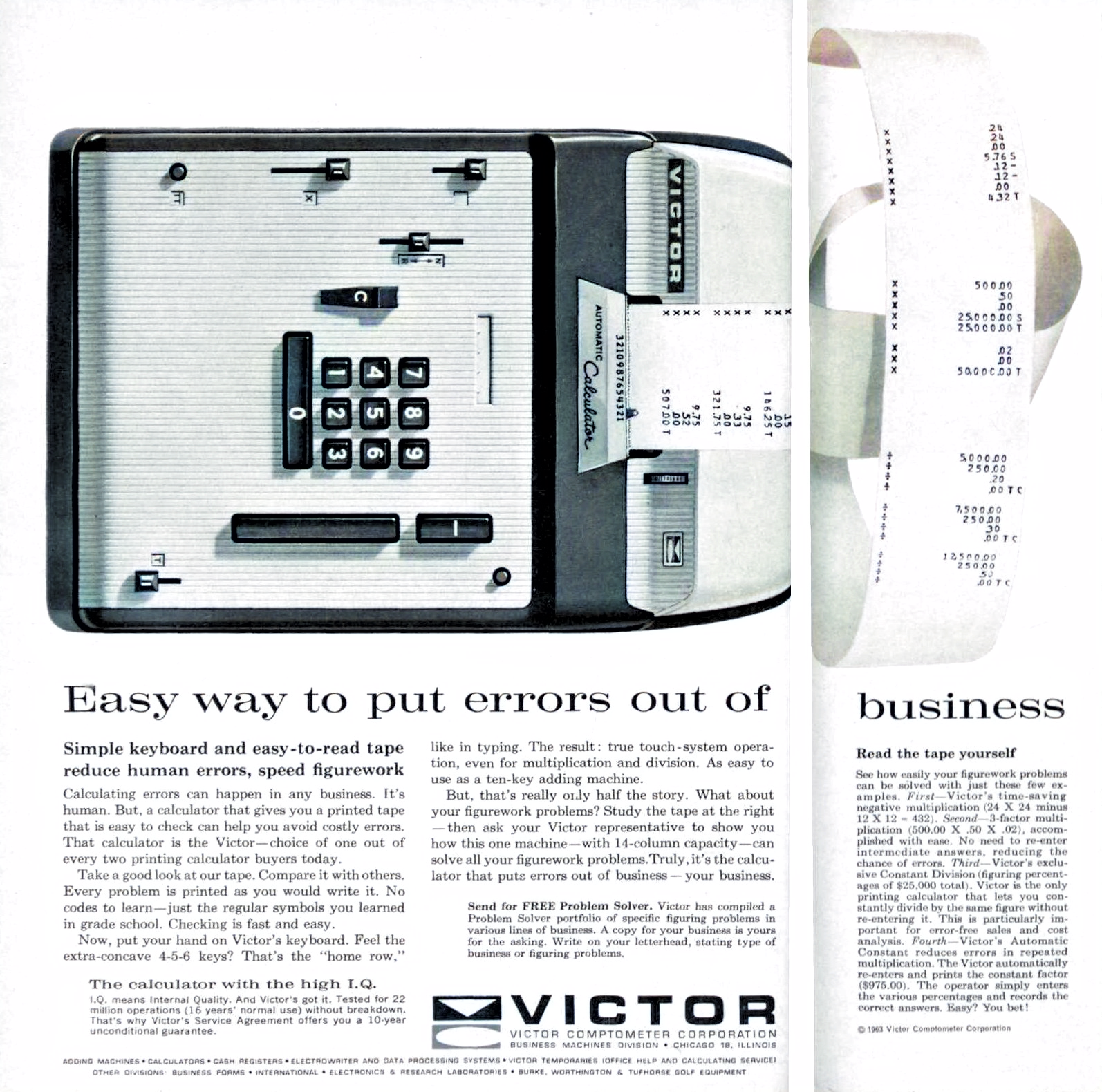

Riding high into peacetime, Victor was able to put its considerable resources into research and development, doing its best to keep up with the lightning fast advancements in business machine technology. There were necessary corporate shake-ups, too, as the firm bought out the old McCaskey Register Company, merged back in with the Buehler Bros. Company (which had been carrying on under the control of A.C.’s brothers all these years), and eventually joined forces with one of their old rivals—the Comptometer Corporation (formerly the Felt & Tarrant MFG Co.). The latter acquisition was called a “merger,” but Victor took over control of Comptometer’s automatic calculator products, creating a new entity in 1961 known as the Victor-Comptometer Corporation.

Riding high into peacetime, Victor was able to put its considerable resources into research and development, doing its best to keep up with the lightning fast advancements in business machine technology. There were necessary corporate shake-ups, too, as the firm bought out the old McCaskey Register Company, merged back in with the Buehler Bros. Company (which had been carrying on under the control of A.C.’s brothers all these years), and eventually joined forces with one of their old rivals—the Comptometer Corporation (formerly the Felt & Tarrant MFG Co.). The latter acquisition was called a “merger,” but Victor took over control of Comptometer’s automatic calculator products, creating a new entity in 1961 known as the Victor-Comptometer Corporation.

By 1968, the little upstart business that had begun with a misunderstanding had grown into a Fortune 500 company, with more than a dozen plants around North America—including the original Chicago facility. Following A.C. Buehler’s death in 1971, however—and the subsequent rise of his son A.C. Jr. to Chairman—change was on the way.

Victor-Comptometer merged with New Jersey’s Walter Kidde & Co, Inc., in 1977, and much of the old Victor calculator production was moved to El Paso, Texas, under the name Victor Business Products.

In the aftermath of a series of Chapter 11’s, buyouts, and brand swaps, a corporation known as Victor Technology, LLC, survived into the present day—still claiming a historical link to the original Victor Adding Machine Co. from 100 years ago, despite no clear connections to the old family business.

Victor Tech is still in the calculator game—calling itself “the exclusive provider of Sharp calculators in the U.S. and Latin America” and “the largest provider of printing calculators in the U.S.” Their headquarters, in Bolingbrook, Illinois, isn’t too far from where it all started.

Sources:

It All Adds Up: The Growth of Victor Comptometer Corporation, by Edwin Darby, 1968

Typewriter Topics, August 1922

Office Appliances, March 1945

The Victor Story, 1952

“Self Financed Firm Produces U.S. Bombsight” – Chicago Tribune, April 13, 1945

Archived Reader Comments:

“After graduation from High School, my aunt who worked on the Assembly Line asked if I could get a Job at the Plant on Rockwell Avenue. They hired me and I started to work on the “Calculator Line” putting the Cases on the Assembled Machines. Since my mechanical ability was “pretty good”, I set a new Production Record for that step in the Line and was quickly asked to try a new position further up the line. Then there was my first and not the last raise in salary. Needless to say, I learned many more Steps in the Assembly Process and was asked to help out the Day-Shift Head “Calculator” Repairman. Within 3 years, I went from the Case Assembly position to “Head Repairman” with 2 or 3 employees working under my direction. I was 21 years old when I saw what was happening to Technology and asked to leave to go to College. Victor’s Management fully supported my decision and said that I was welcome back for Summer Work which did not materialize since things were moving too quickly and the “Mechanical Calculator” became a “White Elephant.”

Texas Instrument became the driving force and one of my Classmates was the first to by a $250.00 Electronic Hand-Held Calculator that instantly gave you the answer. A few years later I saw the Auction Advertisement disposing of the Plant and Equipment on North Rockwell which I was asked to work “overtime” during the Plant Expansion in the 1960’s. I guess I did make the right decision to move on to College and seek another Career that I am still fully involved in at 75!” –-L. W. Ridder, 2019

“My father, Fred Barney, was a dealer for Victor adding machines, multipliers and cash registers in the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s. in the Rhode Island area. He sold 1000’s of these machines to Electric Boat, Groton Submarine base, Newport Naval Base and the Sea Bees base in Quonset Point, R.I. As a kid, I saw 18 wheeler trucks park in front of my dad’s business and unload 1000’s of these machines, while his mechanics prepared them, one by one for delivery.

Victor was very generous to their top sales people and dealers. My dad won fully paid trips and vacations all over the world, as he spread the Victor story all over the New England area.

My dad could completely take a Victor multiplier apart, screw by screw, link by link, spring by spring, put all the parts in a cardboard box and shake it up and reassemble the entire multiplier from memory. Yes, I saw him do it! Plus, all my dad’s mechanics were trained by Victor in Chicago. Everyone of them were ACE mechanics. I also got to see the first electronic handheld calculator produced by Victor. It was about 9 inches long, 3.5 inches wide and more than an inch thick. It sold for $400.00 dollars. Today, you can get the same capacity calculator, via Japan or China for .50 retail.

Thank you Victor Comptometer Corp. You richly helped my dad have the ability to give me a more than abundant life, as a youth growing up in this great country of America. Sincerely . . . ” –Fred I. Barney III, 2018

“I have sitting on my desk beside me a Victor 6-6-0 Serial 410721 in what appears to be perfect working order.. Needs a new ribbon though……very faint when printing. I have owned it for maybe 10/15 years.” —David Filbey-Haywood, 2017

When did Victor make the first aMod, (adding machine on a drawer)?

I have a cash register series Ka 40 Serial No. 939015

HUGIN KASSAREGISTER AB

MADE IN SWEDEN 1592

IS IT WORTH ANYTHING ?

Looking for ribbon and paper for what I believe is a 600 series. Serial # 713235 the ribbon is only black and measures 5/16 in. wide on a spool that is 1 1/2 in. in dia.

My father worked at Victor in Quality Control from the late 50’ to the mid 70’s. I remember Victor would give turkeys to their employees at holiday time.(I still have one of the Butterball boxes one of the turkeys came in.)

Ironically, I worked at Buehler YMCA from the mid 90’s til 2021. I still work out there every day. I didn’t know for several years after I began working there that Mr. Buehler was the owner of Victor!

Wow. Tres interessant. Je viens de retrouver une de vos machines dans les effets de mes vieux parents decedes recemment.

I’m trying to get information on my adding machine, there is a number on the bottom, I believe is the serial number #262102. From the pictures I’ve seen, mine looks very similar to the Victor. There are 72 different keys for the numbers in all, to the left of the numbers is an “error” key to the right of the numbers, bottom to top “SUBTOTAL”, “TOTAL”, “-“, NONADD”

I am now working at a bank in Central Illinois, I notice we had a Victor calulator. I said wow, my Dad, Godfather, and sister worked for this company, in the 60’s and 70’s. It was located at 3900 N Rockwell, near Irving Park Rd and Western in Chicago. I was very young, but I remember going to drop Dad off some days. He worked second shift, these were the times when there may have been one car per family. I remember the annual company picnics, we drove what seemed to be a long way. I cannot remember exactly where we went, but it was alway so much fun. Thanks for the memories, Joanie King

I have an old Victor from the 500-Series too, but this one (S.Nr. 218871) has nine columns of keys instead of the usual 8 or 10.

Can anybody here remember what the correct model-nr. of this machine was/is? All the sources on the net only show 8- or 10-column machines…

Best regards,

Th.Kirchhof

post@thomas-kirchhof.de (that website is showing my collection, btw.)

Loved reading these articles . My dad ( George Brewer) worked for Victor Adding Machine in Chicago for many years.(40”s and 50’s)

were can i buy a ribbon for a ribbon for a victor champion full keyboard adding machine

I have a Victor adding machine that I would like to donate to your museum. I don’t find a model number on it but I do have the numbers 956461C 60 85 54 on the bottom This machine was my dads n I hate to just throw it in the garbage. Can you use it? I also have an Olympia adding machine model RAS 12 A 62 that I am looking to get rid of.

I worked for Victor from 1957 to 1961 in their Brooklyn N.Y. office

as an outside door to door sales …Sold many adders and Calcs.

In 62..I opened my own Office Mach. Co. I sold it in 2008 ……I Have it

all Thanks to VICTOR I have a good life…..Thanks Val Lorenzo

My good guess is early 1950’s. When I started to work @ Victor in 1969 the serial # of new machines was about 3200000. Remember Iam going back a long way in my thinking. See above comments. Andrew Clayman may have a better date because your machine is before 1970. Good Luck.

I have an oldie. It says Victor on the front and back but not on the top.

It has a number on the bottom, # 380809. I’m trying to figure out just how old this one is. Any ideas?

My grandfather worked for Victor for many years and one of the Buehlers lived near us in Inverness when I was a boy. I recall that Victor had a wagon drawn by a team of ponies which always made a racing appearance at the International Livestock Show in Chicago in the 1950s. The ponies were named after the Buehler children at that time. Although I can’t verify it, I seem to recall my grandfather telling me that Victor also produced the first motorized golf cart.

MAX, You asked about # 218971. It was over a year that you posted the request. For anybody wanting to know the answer, I would say late 1940’s to early 50. Victor built bomb sights for WW!!. So it sounds right for the serial #.

ED Brown, 781760 is from the middle to late 1950’s. I think, it has been a long time for me to think back. Value is unknown. Only a collector may have an idea. Jim

I worked for Victor from 1970 to the closing day in Oct of 1983. I still have some old calculators

in my basement. I even have one of the first series 14-321 electronic machines. It should be still working when I can find it. Iam 77 yrs old and want to find someone to have these. I have even some small parts and old ribbons in their boxes. The # 36 is a series # for the model type. The long number is the serial number of how many of all machines they built. When I left the company, the serial number started at 41.

Hi Jim, thanks for your comment. Our museum collection focuses primarily on objects made before 1970. So anything you might be interested in donating from the ’60s or earlier, we’d certainly be happy to discuss. You can send photos or additional info to us at contact@madeinchicagomuseum.com

Jim, I’d be interested in purchasing those from you. Can you kindly send me an email?

I have a Victor Champion adding machine-Serial # 781760- Would like to know how old it is and approximate value- Thanks, Ed Brown

What can you tell me about the electrI-car division of victor adding machine co?

I worked for Victor from 1965 1970 as a field service tech. Got the job the day I got home from the U.S.Airforce. Went to Chicago for training in many of those mechanical machines.

Stayed working in Office machine field service for 50 years! A great start!

I saw the Rockwell St. building recently, while walking around the area. I’m grateful to this site for the information provided. But I’m curious to know whether this impressive structure is currently in use. Does anyone know?

As a matter of fact it currently in use, company by the name of basic wire and cable making wire and cable. I am currently employed there.

I worked for Victor for 21 years. I’m curious, is the entire building all 3 floors being utilized by Basic Wire?

Is the Cafeteria still in operation?

I own a mecanical Victor Adding machine serial no. 218971

Front side shows a colored emblem.

Can you give me some informations?

The 36 is a series model. The other long # is the # of manufacture of all Victor adding machines..

I have one of these and im trying to figure out what its worth, the serial number is 874784, it says series 36 then below it has 3692

I worked at Victor as Victor Business Products in 1981-2 as part of a young crew of digital era people on the Victor 9000 personal computer project.

Love to share more of the story from that time if anyone still interested.

Did Carl Beuler once own a home off Cuba Road near Ela Township?

This was an amazing read and am so fascinated by this man’s story. I have so much respect for entrepreneurs that take such good care of their employees and go so far!

A fine example of a good businessman with a heart of gold.

All the machines I have were built in the 70’s. Charles Cortina, I need to be able to contact you about your offer. I do not want money for them. A donation to any Veteran group would be fine. Iam a Vietnam Vet, USAF. I need to be able to ship them to you. They are heavy. Thanks Jim Van Wormer. My E-mail is vanwormer7@q.com

We have a Victor Model 7 57 54 Serial # 3734-368. I was courious about this machine. It is in like new condition and hasn’t been used min the nlast 50 years