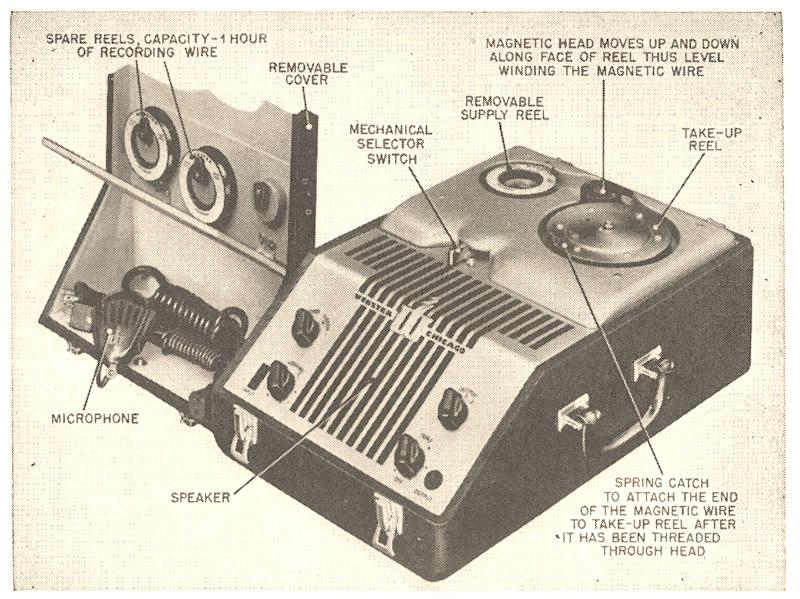

Museum Artifact: Webster “Electronic Memory” Wire Recorder, Model 180-1, c. 1949

Made By: Webster-Chicago Corp., aka WebCor, 5622 W. Bloomingdale Ave., Chicago, IL [North Austin]

“The Electronic Memory is truly one of the most useful additions to the modern home. Not only does it afford the never-failing amusement of hearing one’s own voice or dramatic productions, but it is also invaluable for wire-recording outstanding programs and fine music from radio or record discs, speech development, family events, the voices of growing children, and home movies.” —Webster-Chicago advertisement, 1948

If, like many people, you recoil at the sound of your own voice on an audio recording, you probably won’t relate to the “never-failing amusement” described in the advertisement above. We self-conscious folk of the 21st century often find ourselves disappointed when the imagined rich timbre of our internal monologues is replaced by the reedy reality of a replayed voice message. There’s a bit of an uncanny discomfort to the experience, too—an audio disembodiment—as you’re not only hearing yourself from a distance, but also from the past.

Of course, if you were someone who grew up in the days before home recording was widely available, the mere ability to capture live sound and re-visit it later would have inspired so much awe that there’d be little room left for awkwardness. “You can say something, or sing something, and keep it forever?!” you might have exclaimed in wide-eyed delight. Much like photography, recorded sound was better than anything mankind has previously described as “magic.” It completely changed how we would remember history and experience the present. Like anything else, though, it entered our lives in gradual stages.

The first home dictation machines came around in the first decade of the 1900s, incorporating the same types of wax cylinders that had been used for playing music up until the rise of phonograph disc records. There were popular dictation models from heavy-hitters Alexander Graham Bell (the Dictaphone) and Thomas Edison (Voice Writer), but these things were mega-expensive—priced about the same as the leading typewriters of the era (roughly $2,000 in modern money). And thus, even as radio arrived in most living rooms throughout the 1920s, most people still didn’t have a way to record the programs on it—let alone their own pontifications on Babe Ruth or the Lindbergh baby.

And this finally brings us to the object in question . . . Webster-Chicago’s Electronic Memory Wire Recorder—model No. 180—made its debut in the late 1940s, and for a brief moment in time, it represented the apex of audio tech. Now there was a new, easier way to capture a thought, re-live a moment, teach a lesson, or—if you were a TV detective—catch a killer confessing to their crime.

[A Webster Chicago wire recorder featured on a 1952 episode of Martin Kane: Private Eye]

At a price tag of about $150, the Electronic Memory machine was roughly half the cost of the old cylinder-based recorders that were still on the market; the Dictaphone and Voice Writer. It was also portable (the whole cumbersome system collapsed right into its own handy briefcase like a Transformer) and used a much more versatile technology—stainless steel wires that had first been put to regular use for military recorders during World War II. This wire, unlike wax, could actually be erased and re-used, creating a far more valuable and efficient piece of equipment—albeit with the occasional snarl in the winding process.

The Webster-Chicago Corp. had become a licensee of the Armour Research Foundation during the war, and began manufacturing some of the earliest wire recorders in 1945. When the war concluded and civilian clientele were back on the agenda, longtime Webster president Rudolph F. Blash jumped on the opportunity to adapt the technology for the consumer market. Many larger electronics manufacturers balked at wire recording’s long-term potential, and it’s hard to say they were wrong; the heyday of the wire age lasted about three years. For that short span of time, though, Webster-Chicago enjoyed a dominant a position in its niche industry. The gamble had, for the most part, paid off.

This was no overnight success story, however. Rudy Blash and his enterprise had a long track record dating back before the First World War, and they were often at the forefront of new innovations in sound.

History of the Webster-Chicago Corp., Part I: Rudolph’s Repeater

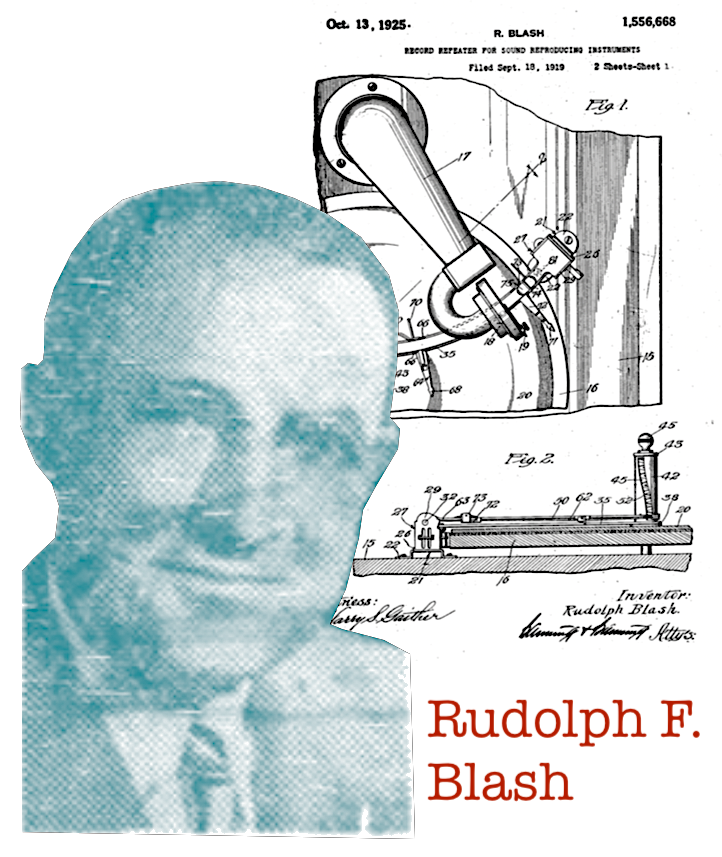

Rudolph F. Blash (b. 1885) grew up in the scenic town of Schönau am Königsee in Bavaria, but by the age of 18, he’d joined the wanderlust armada of young German/Austrian immigrants seeking their fortunes in America. Settling in Chicago, a 28 year-old Blash founded the Webster Novelty Company in 1914, operating out of a small factory office at 1314-1320 N. Sedgwick Street. The business was one of MANY competing in the rapidly evolving industry of “talking machines,” aka phonographs. Specifically, Blash had developed (and eventually patented) a “record repeater for sound producing instruments,” the purpose of which was “to produce automatically a repetition of sound from any selected portion of the record.”

It was a dog-eat-dog marketplace in those early days, and Blash was trying to navigate anti-German sentiments during and after the First World War, as well as legal challenges from other manufacturers of similar “repeater” devices. The cleverly named Repeat-O-Graph Company, in particular, filed an injunction against Webster Novelty in 1919, claiming that Blash was copying their patented device. There must not have been too much bad blood between the parties, though, because the execs at Repeat-O-Graph recruited Blash into a business partnership just two years later. For Rudolph, it might have been a case of “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em,” as the formerly feuding firms came together as the new Repeating Devices Corporation, 670 W. Randolph St.

It was a dog-eat-dog marketplace in those early days, and Blash was trying to navigate anti-German sentiments during and after the First World War, as well as legal challenges from other manufacturers of similar “repeater” devices. The cleverly named Repeat-O-Graph Company, in particular, filed an injunction against Webster Novelty in 1919, claiming that Blash was copying their patented device. There must not have been too much bad blood between the parties, though, because the execs at Repeat-O-Graph recruited Blash into a business partnership just two years later. For Rudolph, it might have been a case of “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em,” as the formerly feuding firms came together as the new Repeating Devices Corporation, 670 W. Randolph St.

“The purpose of this new organization,” according to a press release in the October 1921 issue of Talking Machine World magazine, was to “manufacture and sell under an exclusive license agreement all forms of automatic, repeating devices for sound-reproducing instruments under the patents heretofore used by the Repeatograph Co., by the Webster Novelty Co. and others. In other words, the new company states that the war which formerly existed among the Repeater Stop, Repeat-O-Graph and Webster Novelty Co. has come to an end, and that the inventors of all patents used by these former companies have buried the hatchet and placed all of their eggs in one basket.”

Blash took the role of secretary with the Repeating Devices Corp, but the new marriage was a rocky one, with disappointing returns. In short order, Rudolph decided the truce wasn’t worth it, and he went back to focusing on his own eggs and baskets. He revived Webster Novelty as The Webster Company, maintaining the old company offices on Sedgwick Street and the reliable Herman Biechele as secretary. This wouldn’t be the last time, though, that Blash would have stumble into an ill-fated business partnership.

[1919 advertisements for the Repeatograph Company and the Webster Novelty Company, two Chicago rivals that briefly consolidated as the Repeating Devices Corp. in 1921]

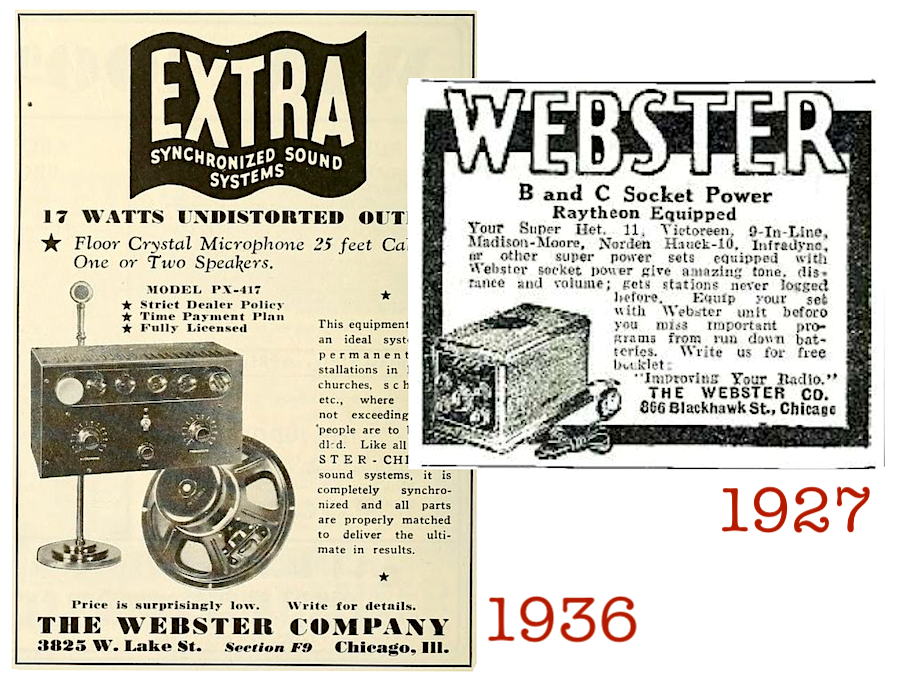

II. The Sound of Tomorrow

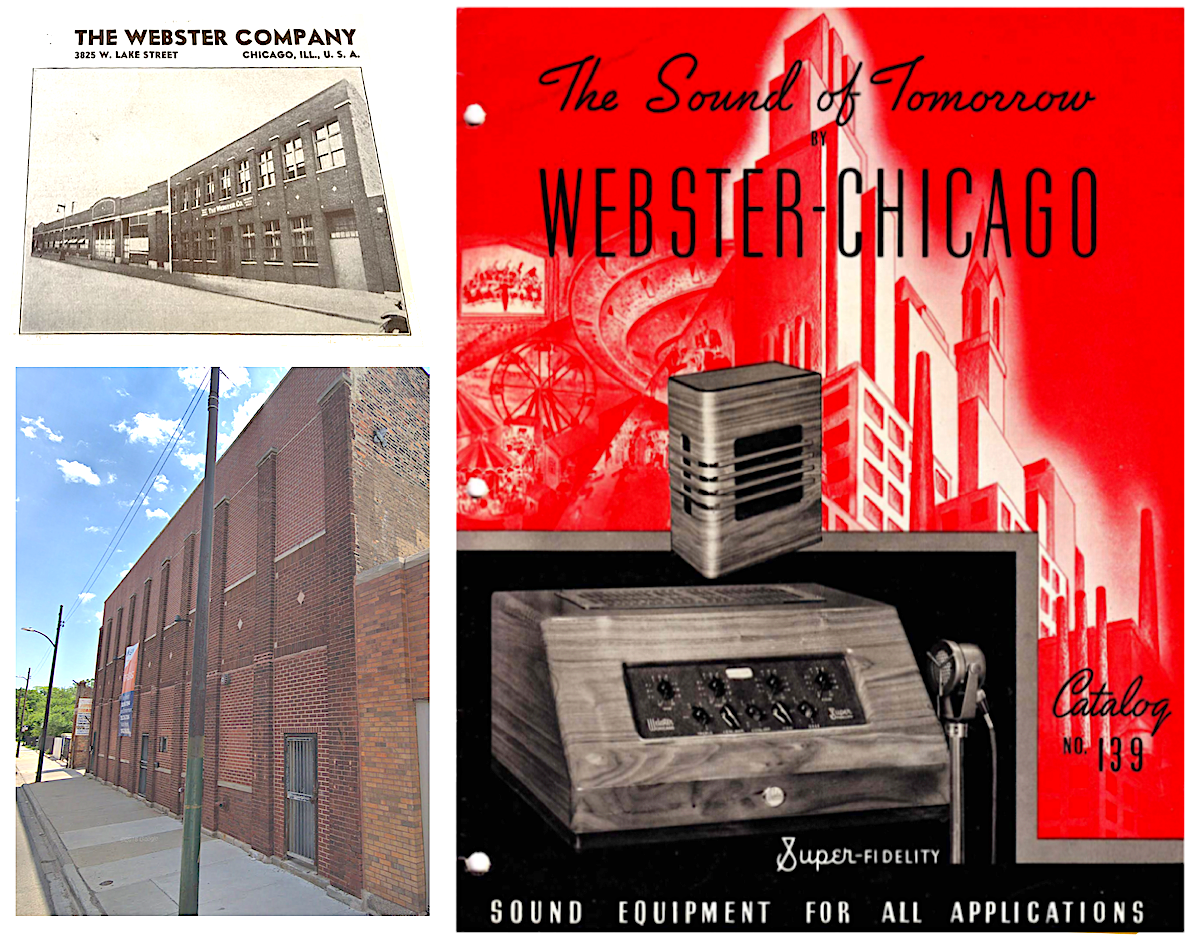

In the 1920s, the Webster Company made batteries and power packs for some of the earliest mass-produced radios, and the company’s amplification technology helped play a role in the arrival of the “talkie” era in motion pictures. The headquarters moved to 850-866 W. Blackhawk Street in the late ’20s, then on to 3825 W. Lake Street by the mid 1930s, where they developed into a major manufacturer of public address systems, or “Extra Synchronized Sound Systems,” for schools, churches, etc.

“SYNCHRONIZED, as related to Sound Equipment, insures the careful balancing of all parts and accessories to produce the finest results in reproduction and economical performance,” explained a mid ’30s Webster catalog.

“SYNCHRONIZED, as related to Sound Equipment, insures the careful balancing of all parts and accessories to produce the finest results in reproduction and economical performance,” explained a mid ’30s Webster catalog.

“All Webster-Chicago products are engineered from the very bottom. Webster does not stop at the design of the amplifier itself. The greatest care is exercised in testing and inspecting the various component parts that go into making up the complete systems.”

The use of the name “Webster-Chicago” was gradually adopted during the ’30s less for hometown pride and more out of obligation; to distinguish Rudolph Blash’s business from one of its competitors, the unrelated Webster Electric Company of Racine, Wisconsin.

As for why Blash had adopted the Webster name for his business in the first place? As far as we can tell, there was never a Mr. Webster involved in the enterprise at any point, so it may have been a strategic move in the 1910s to sound less German; a dynamic that was becoming increasing relevant again in the 1930s. While Blash and his wife were flag waving Americans, records show them traveling to their native Germany aboard a luxury liner in the fall of 1936, suggesting there still would have been plenty of complex feelings in their household when World War II broke out a few years later.

[Left: The former Webster Company plant at 3825 W. Lake Street, as seen in the 1930s and today. Right: Catalog No. 139, “The Sound of Tomorrow.”]

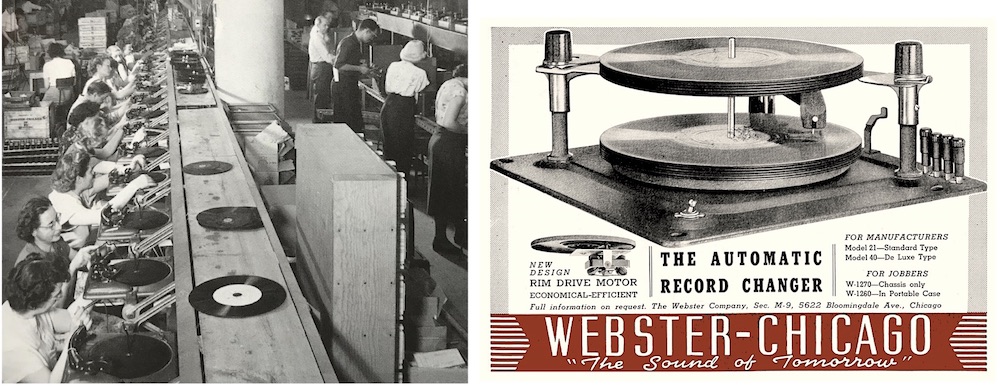

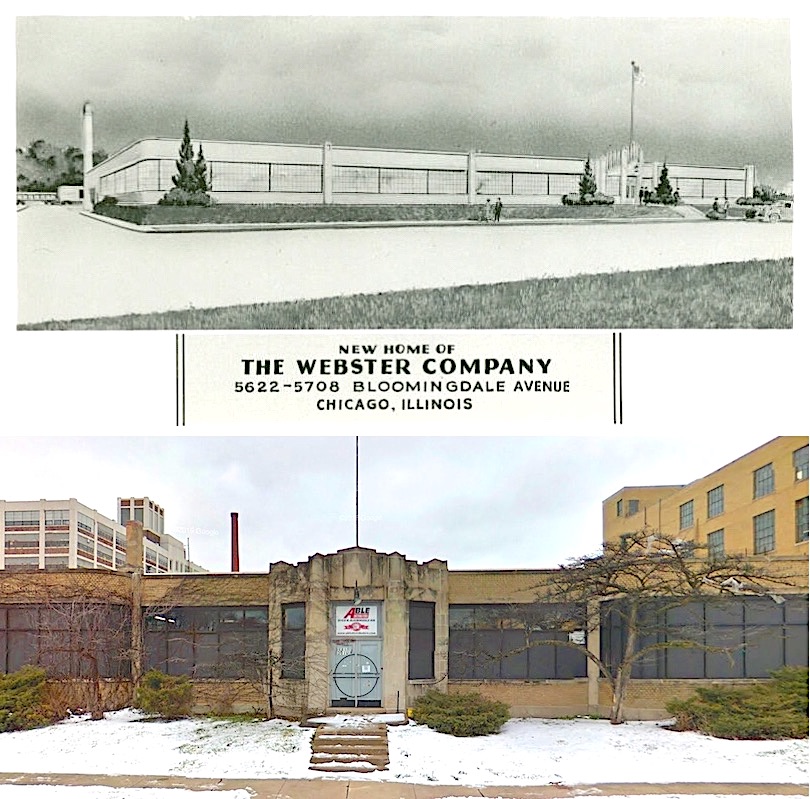

By 1940, the company had officially changed its name to the Webster-Chicago Corporation, with Blash (now 55) still serving as president, Biechele as secretary, and former Thordarson Company sales exec Charles Cushway on board as general sales manager. There was also an expansive new 40,000 sq. ft. factory and office at 5622 W. Bloomingdale Avenue in the North Austin neighborhood, where production ramped up on various audio electrical parts, including new-fangled “record changers” for the phonograph trade of the big band era.

“To the crowds on Main Street has come the crowning luxury of home entertainment,” read a 1940 ad, “the full hour of music automatically played as pre-arranged to the individual taste of the hostess or of her guests. Webster-Chicago’s sturdy, dependable, jam-proof record changer at moderate cost has opened the door wide to volume sales of luxury instruments (and to bigger sales of records, singly and in series).”

The new slogan adorning most Webster-Chicago promotional materials was “The Sound of Tomorrow,” a phrase that didn’t fully anticipate the company’s impending foray into capturing the sounds of the past.

[Above: Assembly line at the Webster-Chicago factory, c. 1940s, and a 1940 ad for the Webster-Chicago Automatic Record Changer. Below: Then and Now of the Webster plant at 5622 W. Bloomingdale Ave., 1940 and 2020.]

III. Down to the Wire

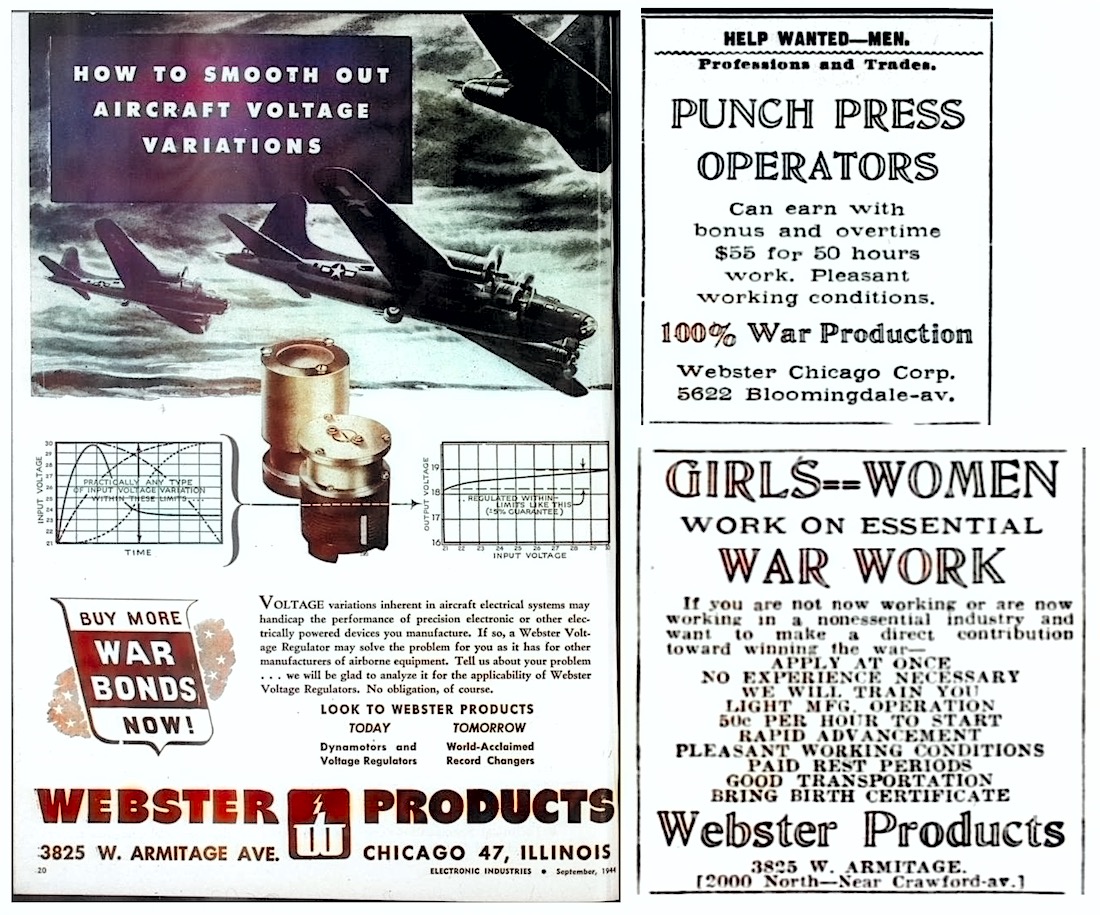

During World War II, Webster turned all its resources over to defense work. For two years, the company also split into two somewhat separate entities. The original Webster-Chicago Corp., at 5622 W. Bloomingdale, continued manufacturing “tools and dies, metal stampings, machine parts, and special apparatus,” while a new operation called Webster Products took over a plant at 3825 W. Armitage Avenue, producing “dynamotors, generators, inverters, small motors, voltage regulators, and special instruments.”

A 1943 newspaper ad recruiting girls and women to the Armitage factory expressed the importance of the work being done there: “If you are not now working or are now working in a nonessential industry and want to make a direct contribution toward winning the war– APPLY AT ONCE. No experience necessary. We will train you.”

A 1943 newspaper ad recruiting girls and women to the Armitage factory expressed the importance of the work being done there: “If you are not now working or are now working in a nonessential industry and want to make a direct contribution toward winning the war– APPLY AT ONCE. No experience necessary. We will train you.”

Like many electronics manufacturers during the war, Webster ran the risk of falling behind on its research and development for the consumer market. But, as many of these businesses learned, today’s innovations for the military could eventually become tomorrow’s exciting new products for the general public.

As noted earlier, Webster-Chicago / Webster Products became early licensees of the Armour Research Foundation during the war—specifically taking orders to produce Armour’s newly developed wire recorders for military use. Armour engineer Marvin Camras was one of the country’s leading developers of wire recording devices, and the goal of the Armour lab was to collect every patent possible related to this new technology. Under the guise of a wannabe conglomerate called the Wire Recorder Development Corporation, Armour sought out big electronics manufacturers to build their machines, charging them license fees and small royalties on all sales. The plan didn’t quite play out as hoped, largely because the simultaneously emerging technology of magnetic tape recording left a lot of companies unsure about investing in wire.

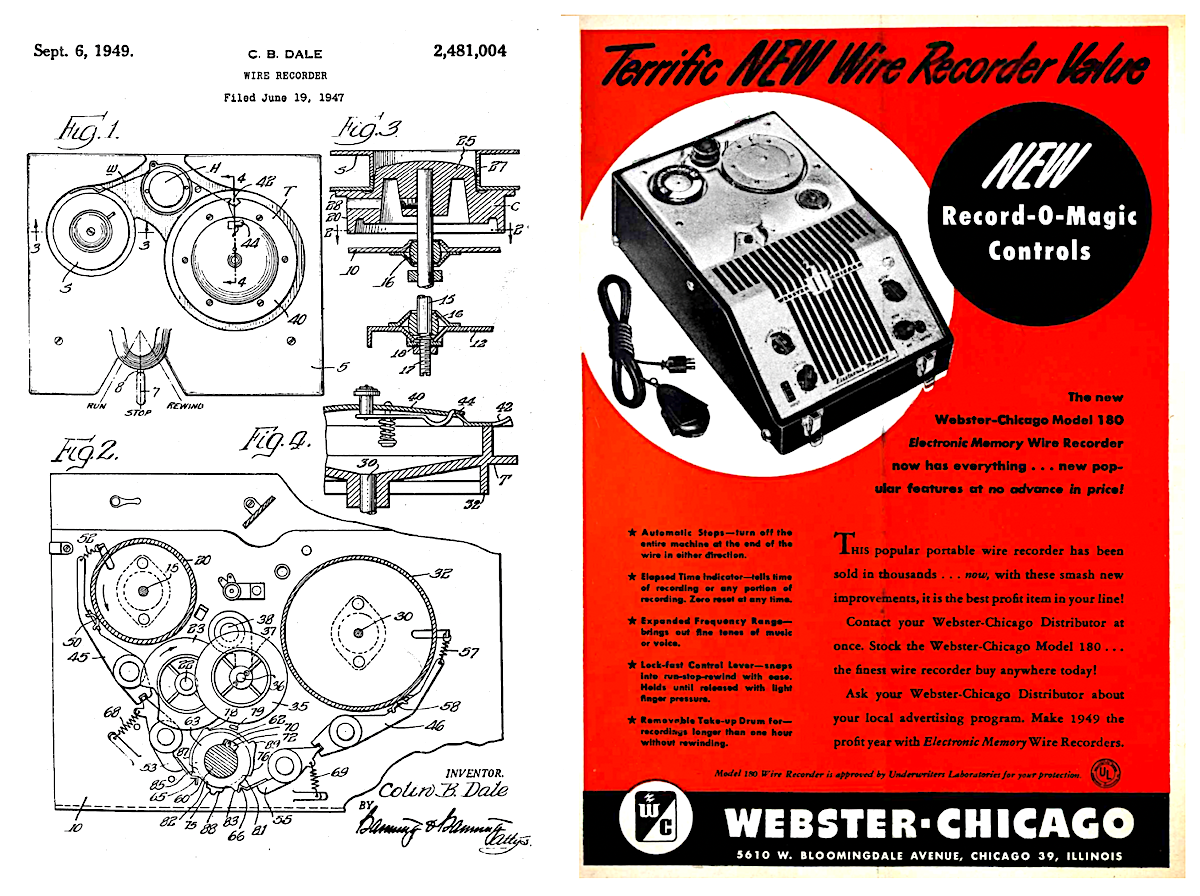

[Left: Colin B. Dale’s 1949 patent for Webster’s Wire Recorder. Right: 1949 advertisement for the Model 180]

Webster-Chicago, as a much smaller firm than the General Electrics or Westinghouses of the world, decided a risk was more worth their while, especially considering the greater retail affordability of wire recorders vs. tape recorders at the time. Once the war was over and Webster Products re-merged into the Webster-Chicago Corp., the production of wire recorders for the consumer market became a major focus. Lead research engineer Colin B. Dale also went to work refining the Armour designs, scooping up patents for Webster that might help them dodge some of those royalties owed to the Wire Recorder Development Corporation.

In 1947 and 1948 alone, Webster developed several models of its “Electronic Memory” machine and sold over 40,000 units—a pretty encouraging number for a hefty piece of specialty equipment in an unfamiliar format.

Rather than aiming their marketing solely at techies and audiophiles, the company emphasized the everyday appeal, ease of use, and friendly cost of their devices. It was not only a dictation machine, but a new way to record shows off the radio, or lessons in a classroom, proceedings in courtrooms, etc. Working on perfecting your accordion playing? The Electronic Memory could record 15, 30, or up to 60 minutes of your awful band practice for you and your friends to listen and learn from. The sound wasn’t exactly THX, but as mentioned earlier, it was still magical for people who’d never had any such technology at their disposal before.

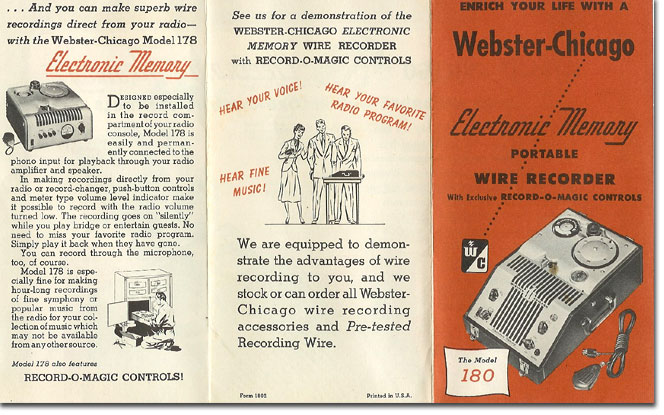

Here’s how one advertisement for our museum’s Model 180 summed up the wonders of the post-war, portable wire recorder:

“The new Webster-Chicago ‘Electronic Memory’ is easy to use!” Automatic Stops shut off motor before wire can run off either spool in either direction. Resets automatically when Lock-fast Operating Lever is returned to center position. Push-pull output Expanded Range amplifier allows recording of voice and music with excellent fidelity.

“Built-in Elapsed Time Indicator permits accurate timing, cueing and editing. New, powerful erase circuit. Removable Take-up Drum permits fast reload of recordings longer than one one hour. Has radio input and external speaker or amplifier outlets. Compact luggage case measures 17-3/8″ x 11-3/8″ x 7-1/2″. Carrying weight is 27 lbs. Operates on 105-120 volts, 50 or 60 cycles AC. Complete with microphone, 3 spools of recording wire and instructions. $149.50.”

As a testament to the designs of Colin Dale, the skill of Webster’s factory workers, and the standard set by Rudolph Blash himself, Webster’s wire recorders became highly respected by those aforementioned techies and audiophiles, as well, including today’s collectors. The 70+ year-old Model 180 in our museum collection is a good example of this quality; its handy carry case houses all the original components, including the Deco-fabulous microphone, and the reels and switches still operate as they did back in the day.

[A recovered wire recording played on a Webster 180, from a video posted by Complete Estate Solutions, 2018]

IV. A Tangled Webcor

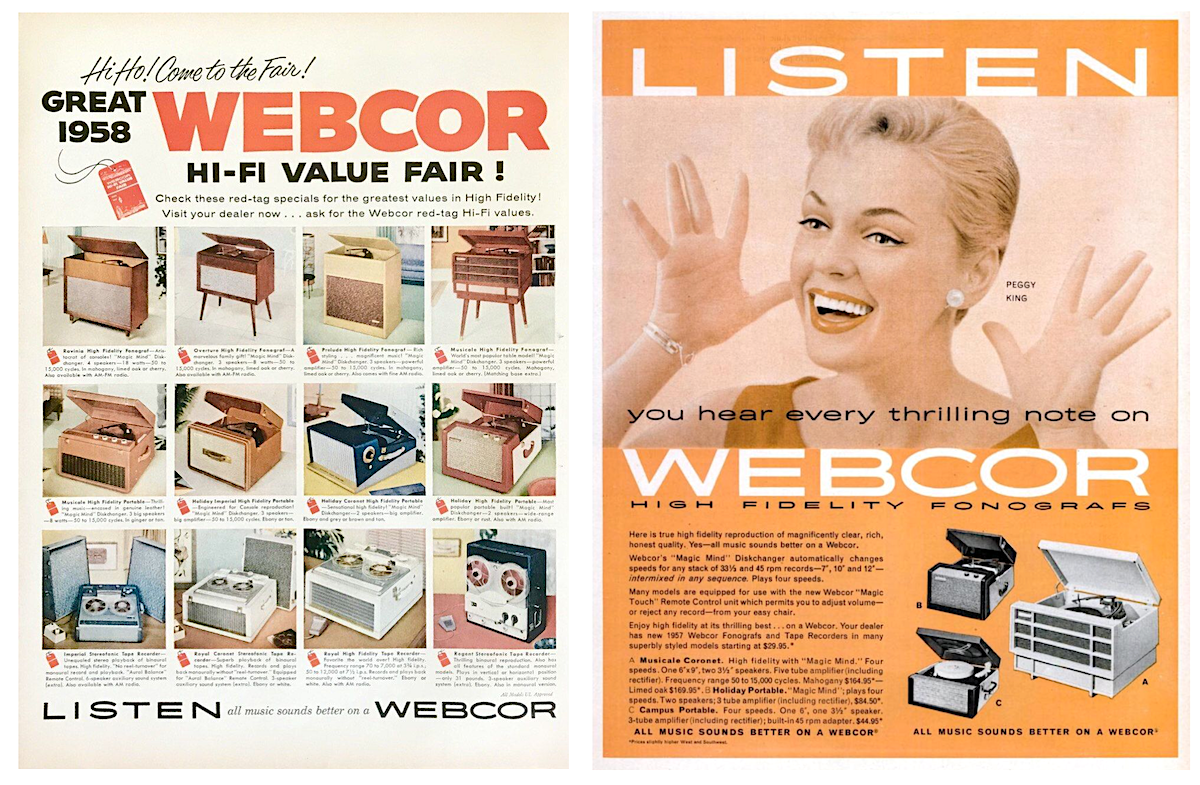

As the wire recorder bubble began to burst in the early 1950s, it was an unfortunate blow for Rudolph Blash, who was now over 65 and hoping for an easy retirement. Still, the outlook wasn’t entirely bleak. In the world of tech equipment, you’re only as good as your newest products, and staying competitive requires running a marathon at sprint speeds. Blash, even in his later years, remained keenly aware of this fact, and it helped Webster-Chicago—now routinely known by the nickname WEBCOR—hit an all-time high in sales in 1953, as its wire, phonograph, and record changer lines were joined by a new line of tape recording equipment. The company also employed over 1,800 workers in Chicago, a high water mark.

Much like the ill-fated Repeating Devices Corporation 30 years earlier, though, Blash’s eagerness to find like-minded partners led him into more boardroom misfortune.

Much like the ill-fated Repeating Devices Corporation 30 years earlier, though, Blash’s eagerness to find like-minded partners led him into more boardroom misfortune.

In 1952, he’d brought back a former protege, Donald MacGregor, to take over the company presidency. MacGregor had spent the past few years as the VP of the Zenith Radio Corp., and seemed like the perfect guy to guide Webcor into the new tech age. For mysterious reasons, however, he resigned just 10 days into his new role.

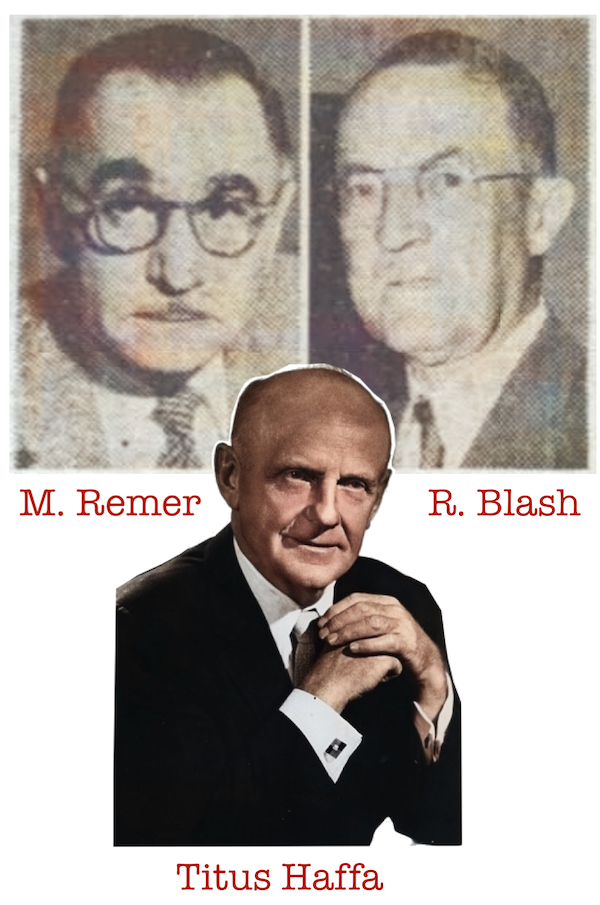

Undaunted, Blash next proposed a major corporate merger with the Emerson Radio and Phonograph Corp. of New York, which would have given Webster another avenue into the TV business. Unfortunately, this move—poorly timed with a seemingly suspicious sale of much of Blash’s own personal stock—drove a massive wedge into the Webster board of directors, with a leading investor named Martin C. Remer leading an aggressive campaign to discredit Blash and shut down the merger.

“My entire adult life has been spent in building the good name of Webster-Chicago and endowing it with products of which you can be justifiably proud,” Blash told the board in 1953. “It is true that I have disposed of a substantial amount of my shareholdings, but that was done primarily to assure liquidity of my estate, which theretofore consisted exclusively of my investment in Webster-Chicago corporation, and to prevent the enforced liquidation thereof in the event of my untimely death.”

[Advertisements for Webcor’s phonografs and tape recorders, 1957/58. By this point, the wire recorders were no longer being regularly promoted]

The deal with Emerson was ultimately shut down, and in the aftermath, as Webcor’s profits failed to keep up with its sales numbers, Blash became increasingly reliant on the advice and financial aid of an old childhood friend by the name of Titus Haffa.

Haffa, as profiled in our history of the Dormeyer Corporation, was a former Chicago alderman who’d served prison time in the 1920s for running an illegal booze ring during Prohibition. Now, 20 years later, he had re-emerged (largely through wartime defense contracts) as one of the city’s leading industrial tycoons—a millionaire with over a dozen companies under his control, including Dormeyer and the Haber Corp. Whether it was clear to his old buddy Rudy Blash or not, Haffa now had his sights firmly on adding Webcor to his empire.

After becoming a minority stockholder in the early ’50s, Haffa gradually bought up more and more of Blash’s shares in the business, supposedly as a “favor” to a friend who needed the money. On further inspection, and based on Haffa’s notorious reputation, it was also a not-so-hostile takeover. By the summer of 1955, Haffa suddenly had a majority stake in the firm, even though he wasn’t even on the board of directors. He decided to wield his new power by firing four Webcor executives without even bothering to consult with company president Norman C. Owen. In response, Owen resigned, and Haffa slid right into the presidency. “I thought I could work on the sidelines,” he told Business Week. “I wasn’t after any scalps.”

Rudolph Blash died a year later, aged 70, leaving 63 year-old Titus Haffa fully in control of Webcor’s fate.

During the 1960s, the business struggled to get ahead in the age of magnetic plastic audio tape and modern hi-fi systems. By 1965, the Bloomingdale Avenue headquarters was abandoned, as Haffa was forced to consolidate Webcor’s dwindling operations into the Dormeyer Corp. building at 700 North Kingsbury Street. In 1967, Webcor filed for bankruptcy, with executive vice president Richard Cole citing “unprofitable military contracts and foreign competition in the tape recorder field” as the main causes of the collapse. The company’s trademarks came under the ownership of U.S. Industries, Inc., in 1969, which kept the brand alive for a few more years until the proverbial spool of wire finally reached its end.

[An Electronic Memory wire recorder featured in the 2021 film Nightmare Alley. The film is set in 1941, about 7 years too soon for this machine to have existed. Oh well.]

Additional Sources:

“Another Consolidation” – Talking Machine World, Oct-Dec, 1921

The Concise Encyclopedia of American Radio, edited by Christopher H. Sterling, Cary O’Dell

Off the Record: The Technology and Culture of Sound Recording in America, by David Morton

“Steel Concern Buys 15 Acre Factory Site” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 29, 1936

“Webster Chicago Is Now the Official Name” – Radio Today, Sept 1940

Webster Chicago Has Sold Its Armitage Avenue Plant to Webster Products” – Metals and Alloys, July 1943

“Merger Plan is Defended by Webster Head” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 28, 1953

“Emerson Radio Kills Webster Merger Deal” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 5, 1953

“Lid Blows Off Webcor’s Rough and Tumble Row” – Business Week, July 23, 1955

“Webcor Losses Told” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 9, 1967

“Armour Research Foundation and the Wire Recorder: How Academic Entrepreneurs Fail,” by David Morton, Technology and Culture, Vol., 39, No. 2, 1998

Archived Reader Comments:

“I have an early 60’s WebCor that I found in a dumpster years ago, never used it as a tape recorder but the microphone input makes a killer guitar amp (all tube, of course)” —Marc, 2019

“ A very good writeup. I just heard a recording off of one of these today and am surprised at the quality (given that it was probably recorded 60 yrs ago) Thanks for the very nice tech history.” —John Brewer, 2019

A very good writeup. I just heard a recording off of one of these today and am surprised at the quality (given that it was probably recorded 60 yrs ago) Thanks for the very nice tech history.” —John Brewer, 2019

“Earlier I submitted comments on another company (Western Electric) as having worked there after my service in the AAF and moving to San Diego for a position at Convair Aircraft. Then, due to a family obligation, I moved back to Chicago and went to work at Webster _Chicago as a design engineer. This was at the time that WebCor had phased out their wire recorders and were in the 1st generation of their tape recorders. (I owned one). However, I was part of the military electronics group. This department was a big part of the company at the time and was developing electronic devices for the U.S. Government and use by the FBI among others. A great company, but I decided to return to Convair again later.” —Bob Bacchi, 2019

“Bob, interesting to hear this. My grandfather worked as a design engineer at Chicago Webster, then WebCor. His name was Norm Conrad. I have been researching what he actually did there. I was told that he was instrumental in designing wire recorders and was there at the beginning of the magnetic tape reel to reel days. I remember having one of the reel to reel players when I was a child. He passed away in 1952, I think. I know it was just before I was born in 1954. It’s good to hear from someone that was there.” —Jim Millener, 2019

Good morning,

I found a Webster A27 tube amplifier with the microphone in my grandfather’s belongings. I don’t know if it works, the tubes look ok but given the condition of the cables I didn’t connect the 220/110V transformer. Do you know anyone who might be interested?

I am in France.

I can save a Webster 180 from to be drown in an ugly scrapyard, looks little used, full documentation and have some wire reels. Is this something to save?

I am interested in the wire alloy that was used for recording at that time.

Our company is studying the magnetisation of steel wires

Hi, Can you tell me what an operational Webster model 322 reel to reel recorder is worth ? it has the vacuum tube amplifier & is fully operational. thks rick

Webster-Chicago also made a 45 rpm record adapter, a solid zinc disc notorious among record collectors today as difficult to remove. But it can be done, and this is the secret. Position the record so that two of the tabs that overlap the label are facing you, and are at the “12” and “6” positions. Gently slide the adapter either upward or downward, whichever way it moves more easily; until either the “12” or “6” tab is no longer overlapping the label. Now, also gently, press outward (away from you) against the half of the adapter, whether upper or lower, that is not overlapping the label. The adapter should swing on its horizontal axis and drop out of the record. (Clink!)

This should cause no damage to the record and little if any to the label. As for the zinc adapters, I dunno. Maybe if you had enough of them, you could string ’em on a chain and wear them???

I have one of your wire recording machines 041775 model number 228-1. RMA 375. I would like to know the year it made the price and more about it. I never seen one before.

Thank You Marilyn

Was this business located at 3825 Armitage in Chicago in 1941?

Good morning,

I have one if your product tape recorder same above or similar, unfortunately I can’t read the model number behind the tape, it’s very old, my question is the sound not working I think one of the values damaged, do you have spare parts.

Regards

Goodmorning Chicago Museum, my name is Ted.

I own a Webster Chicago MM-38 Crystal Hand Microphone. I was wondering, if you have a product manual for this model.

I’m looking for electronic specifications that would include power requirements, watts, volts, ohms and all that good stuff that will help me operate the mic without damaging it for lack of knowledge.

If you could email me a scan of the original operating manual or documents you have on digital file, that would be greatly appreciated.

Many thanks in advance, Ted Kelly

I have a model 18 Webster-Chicago wire recorder are they worth any money?