Museum Artifacts: Luminous “Big Ben” & “Baby Ben” Clock Dials (1940s) and Style 1A “Big Ben” Alarm Clock (1920s)

Made By: Western Clock MFG Company, aka Westclox, 350 5th St., Peru, Illinois [LaSalle]

A clock without hands might seem indifferent to the passage of time, but these old “Big Ben” and “Baby Ben” dials have some serious stories to tell.

Purchased from a man who claimed to have salvaged them from the backroom of an unnamed Chicago watch repair shop, each round and weathered face represents the lasting work of an international manufacturing giant at the peak of its powers. Unfortunately, they also hint at a tragic chapter in American industrial history, when the appeal of a “luminous” new kind of paint wound up putting hundreds of workers—mostly young women—at great personal risk.

Before we get to that, though, we have to start with the issue of geography as it concerns the business in question.

For at least four generations, the Western Clock Manufacturing Company, aka Westclox, was the lifeblood and largest employer in the small town of Peru, Illinois (with a mailing address in its twin city of LaSalle). Located at 41.3275° N, 89.1290° W on the map, the company’s former plant is admittedly on the absolute fringes of what would typically be designated “Chicagoland” turf. Even today, with the considerable help of a thing called Interstate 80, it’s still about a two-hour journey from LaSalle Street to LaSalle County. So, does Westclox really belong in the Made In Chicago Museum?

Well, the company certainly maintained some major salesrooms here, and many of their employees came from the city and its suburbs. Above all else, though, the rise and fall of Westclox—and the deeper history of these Big Ben clocks, in particular—is simply far too intriguing to dismiss just because of a long-distance commute. Even if the Western Clock Co. wasn’t born in Chicago or headquartered here, the immediate aftershocks of the company’s cultural and industrial impact certainly reached our shores in a hurry, no interstate required.

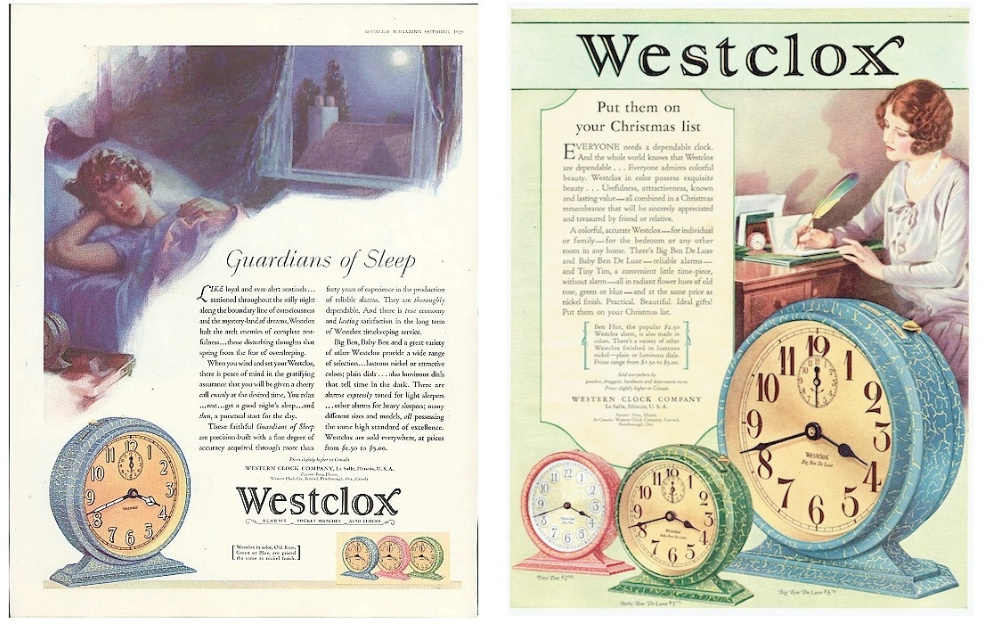

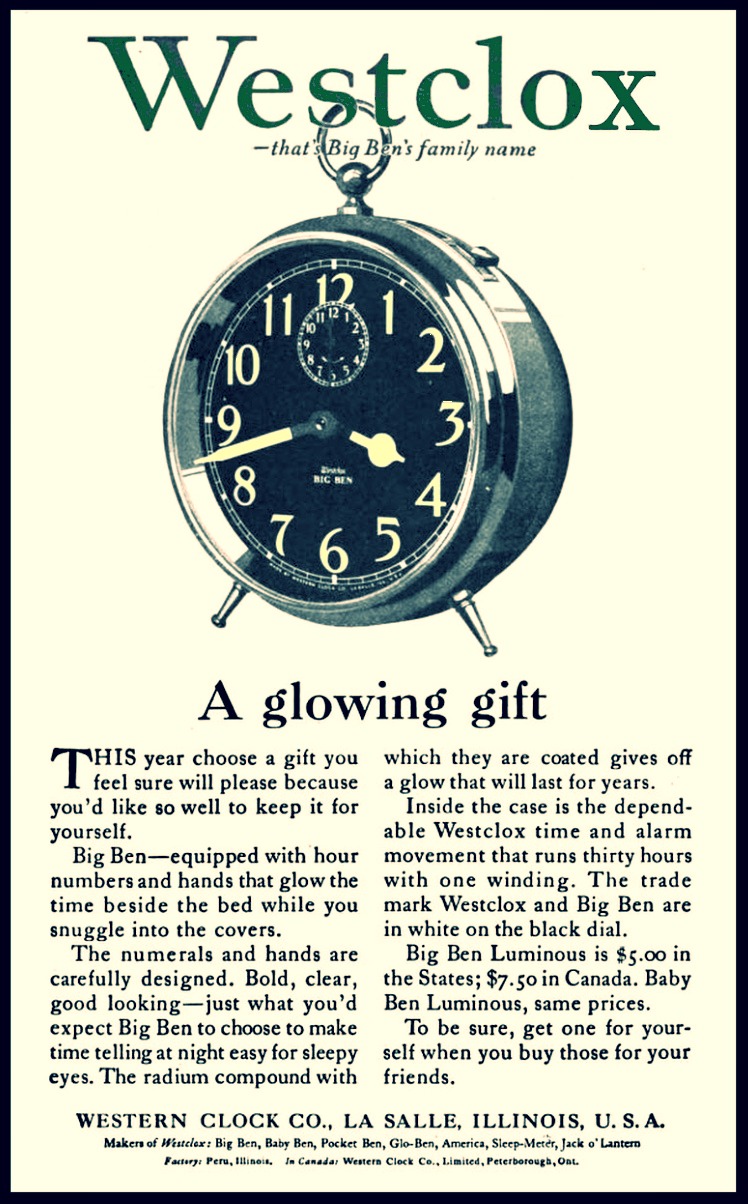

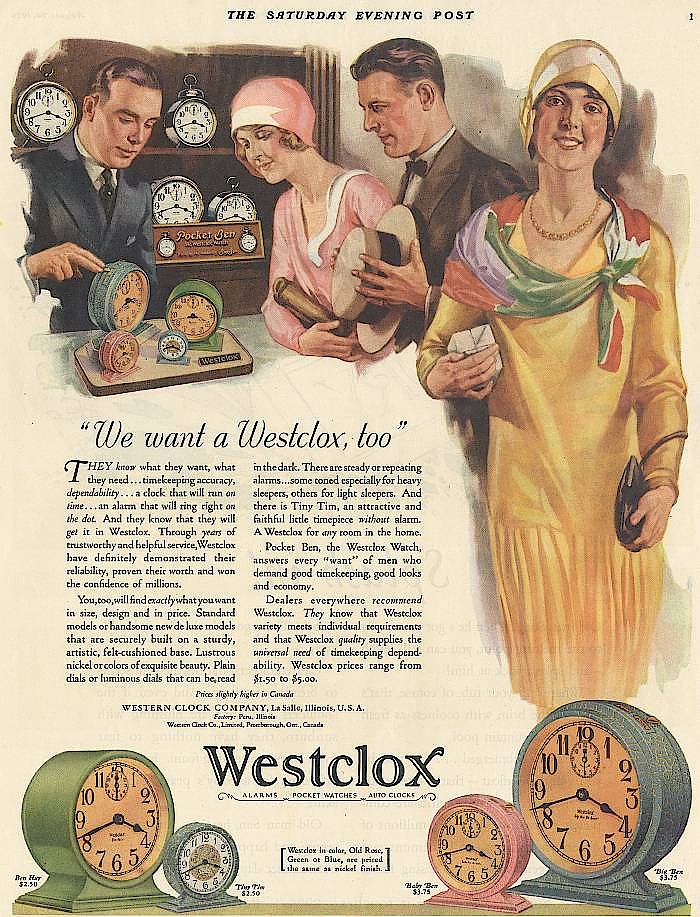

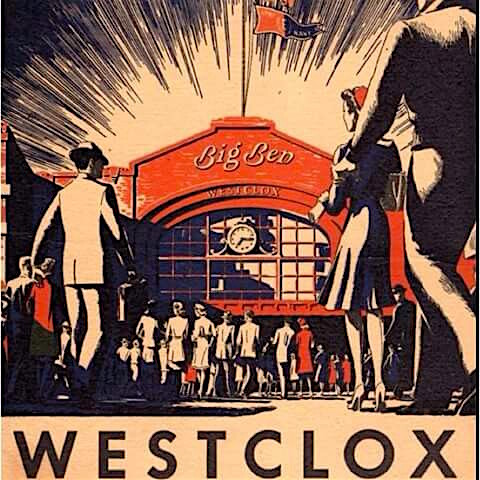

[Westclox advertisements from 1928]

[Westclox advertisements from 1928]

The Beginning of Time

In some respects, the early rise of the Western Clock MFG Co. is even more impressive considering the company didn’t have all the resources of an established, major metropolis to draw from.

The story begins with a Connecticut clockmaker named Charles Stahlberg getting a patent for a new alarm clock design in 1885. Like many East Coasters, he decides to pursue his fortune out West, but unlike many of his peers, he skips the bustling Second City in favor of a promising river & railroad region downstate; where the towns of Peru, LaSalle and Ottawa intersect. Stahlberg knows that no other noteworthy clock company has ever succeeded west of the Hudson, let alone smalltown Illinois, but he dives into the challenge, establishing his first factory. The pioneering spirit is there, but the business skills soon appear lacking. Stahlberg’s company goes bankrupt not once, but twice, within its first several years.

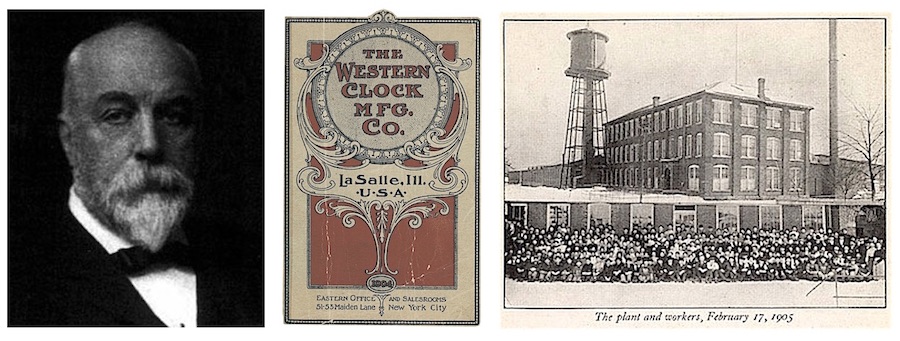

Luckily for Charles, however, he is living in the same small town as Frederick William Matthiessen—a fellow German, but one with a hell of a lot more money and business experience. Matthiessen [pictured below], who owns the powerful Illinois Zinc Company and most other things in Peru / LaSalle, decides to swoop in and save Stahlberg’s little clock business, incorporating it as the Western Clock Mfg. Company in 1888 and installing another talented German, Ernst Roth, as the general manager. It’s basically all forward momentum from here.

[left to right: F.W. Matthiessen, 1904 Western Clock MFG Co. catalog cover, and the original Peru factory in 1905]

[left to right: F.W. Matthiessen, 1904 Western Clock MFG Co. catalog cover, and the original Peru factory in 1905]

The new company tripled in size by the turn of the century, employing 232 people at its growing Peru plant (145 men, 73 women, 14 children) and producing 500,000 clocks annually. Within in another ten years, the workforce had tripled again, powered by employee George Kern’s 1908 invention of the first “Big Ben”—the sleek, iconic model that basically set the template for the 20th century wind-up alarm clock.

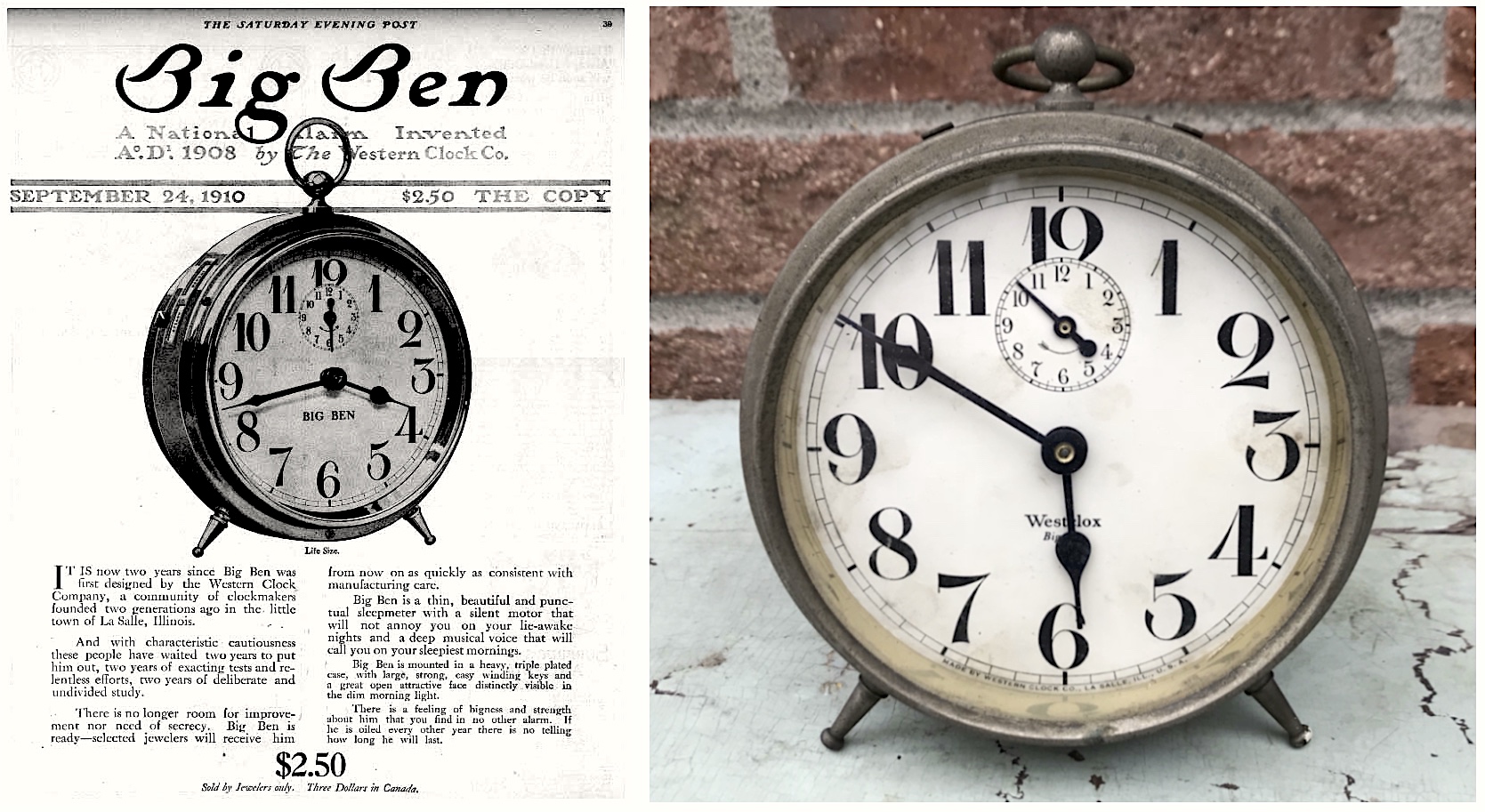

Selling for $2.50 in the years before World War I (or about $60 in modern money), the 5-inch diameter Big Ben and its half-pint cousin the “Baby Ben” combined to move over 900,000 units in just 1913 alone, and the Western Clock MFG Company—not yet officially known as Westclox—was producing more than twice that many clocks annually in total. They were officially America’s preferred wake-up call provider.

[Left: The first national Big Ben advertisement appears in the Saturday Evening Post in 1910: “Big Ben is a thin, beautiful and punctual sleepmeter with a silent motor that will not annoy you on your lie-awake nights and a deep musical voice that will call you on your sleepiest mornings.” Right and Below: A style 1A Big Ben from our museum collection, circa 1920s.]

Big Ben: The People’s Wake-Up Call

Both the Big and Baby Bens were housed in a newly refined “bell-back” clock case. So, rather than having the classic oversized bell or double-bell on top of the unit (to smash with your palm at 6am), the ringing mechanism was housed inside the back of the case, and a big winding key occupied the summit. The alarm mechanism was also improved as part of Kern’s new patents, with an intermittent ringing that kind of acted as an archaic form of snooze alarm.

Up until this point in time (pun intended), quality time pieces had been considered a rich man’s game. But it had always just been a matter of time (pun less intended) before industrial mass production made a wide-scale phenomenon like the Big Ben possible.

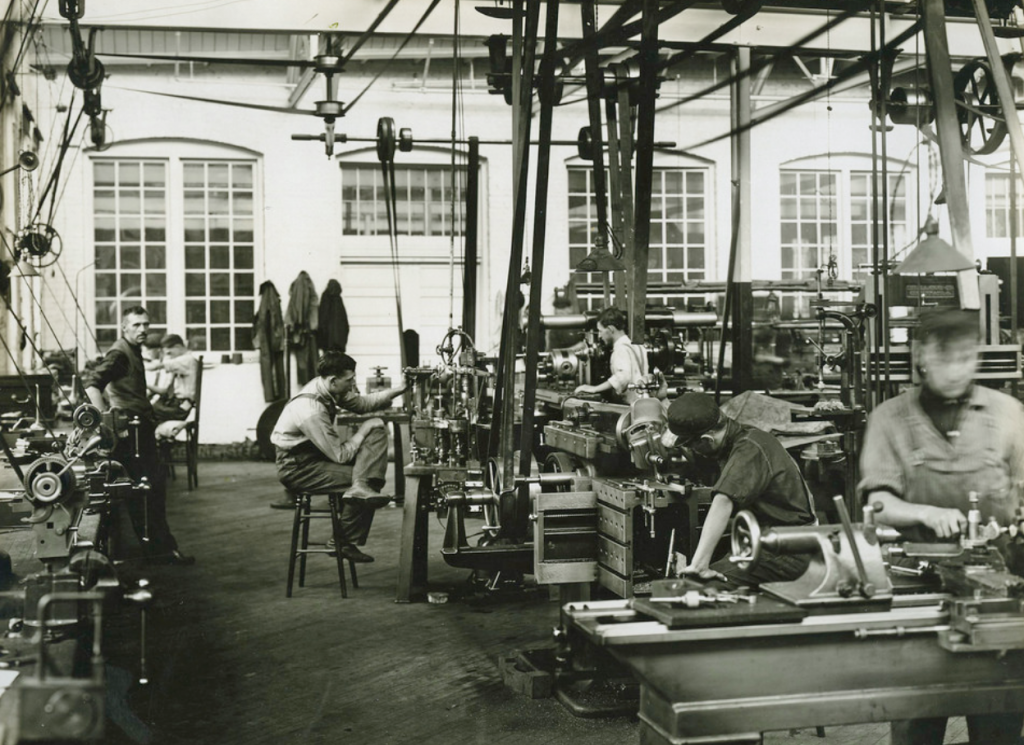

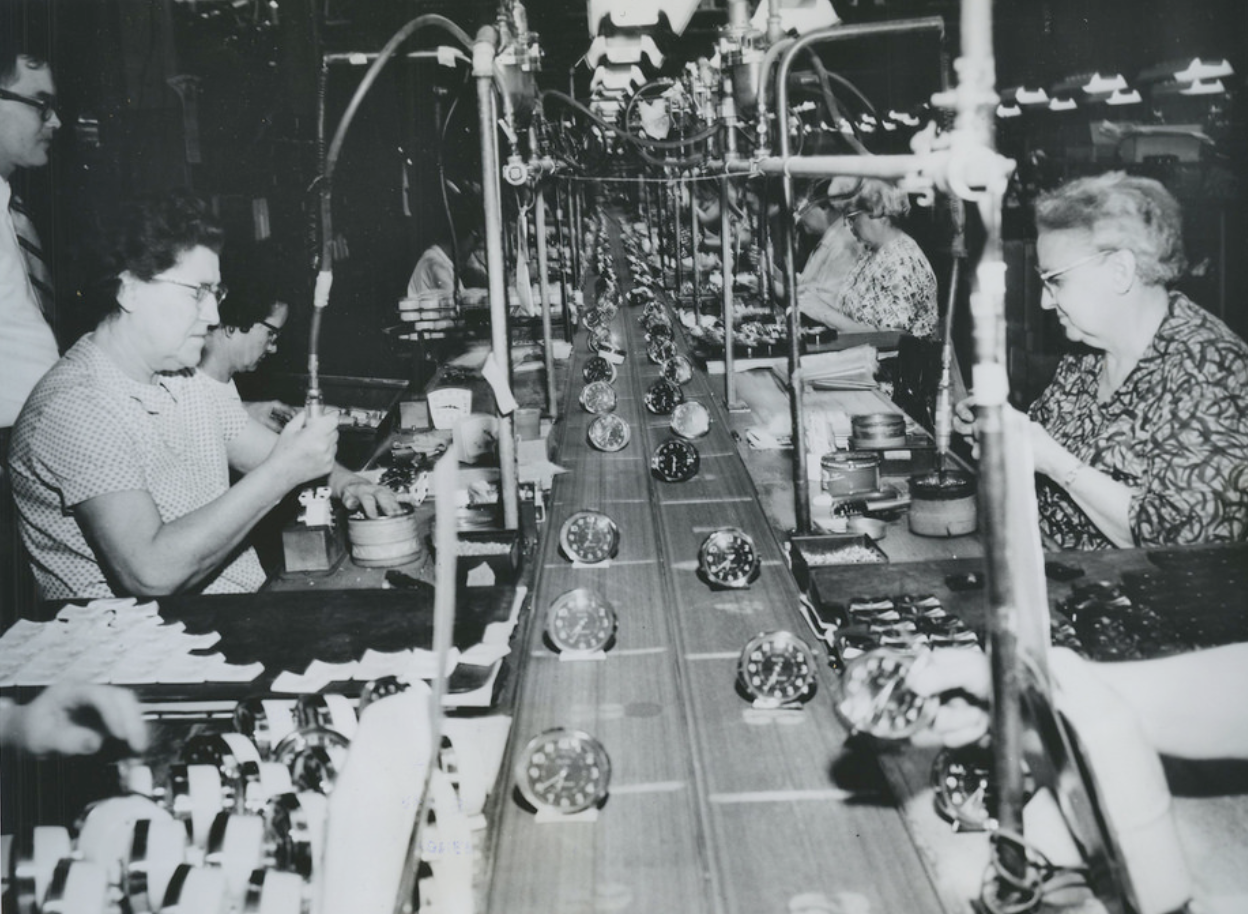

[Workers assembling Big Ben alarm clocks at the Westclox plant, 1910s. credit: Northern Illinois University]

[Workers assembling Big Ben alarm clocks at the Westclox plant, 1910s. credit: Northern Illinois University]

According to a 1909 article in Commercial America, “In clocks, as in all other lines of goods, there are two classes of consumers—the millions and the millionaires. American manufacturers were quick to see that the millionaires are a negligible quantity as consumers, and that, not chronometers—not marvels of intricacy and originality—were needed, but timepieces within the reach and want of all. In the production of ordinary clocks adapted to the needs and means of the millions, America produces results of remarkable excellence. It is in the manufacture of alarm and one-day clocks that these results are the most noticeable, because in this field the quality of the product had always been subordinated to the market value, and the general feeling was one of ‘let good enough alone.’

“In this particular branch of the clock industry the Western Clock Manufacturing Company has achieved great results in the last twenty years. The policy of the company is one of highly specialized production. They make alarm and one-day lever clocks only, and with practically two different articles, known as the 4-inch and 2-inch movements, they have an output of in their factory at LaSalle, Ill., of nearly two million clocks a year. . . . The aim of the Western Clock MFG Co. in entering the manufacture of alarms was to apply to nickel clocks, features which were previously found only in high-priced timepieces, and prohibited in low-priced lever clocks by the high cost of production involved. This end has been achieved by what is known as the Western Process—a process in which the component parts of a clock are cast, or, so to speak, cemented together with an alloy, instead of staked, and in which all hand labor is replaced by automatic machinery.”

“In this particular branch of the clock industry the Western Clock Manufacturing Company has achieved great results in the last twenty years. The policy of the company is one of highly specialized production. They make alarm and one-day lever clocks only, and with practically two different articles, known as the 4-inch and 2-inch movements, they have an output of in their factory at LaSalle, Ill., of nearly two million clocks a year. . . . The aim of the Western Clock MFG Co. in entering the manufacture of alarms was to apply to nickel clocks, features which were previously found only in high-priced timepieces, and prohibited in low-priced lever clocks by the high cost of production involved. This end has been achieved by what is known as the Western Process—a process in which the component parts of a clock are cast, or, so to speak, cemented together with an alloy, instead of staked, and in which all hand labor is replaced by automatic machinery.”

[Automatic machinery certainly sped up the manufacturing process, by plenty of human skill and attention was still required to make the Big Ben. Westclox’s Manual for Employees read, “We expect you to work hard, and the pay is accordingly large . . . If you do not expect to work hard and carefully, you are in the wrong place.” credit: Northern Illinois University]

[Automatic machinery certainly sped up the manufacturing process, by plenty of human skill and attention was still required to make the Big Ben. Westclox’s Manual for Employees read, “We expect you to work hard, and the pay is accordingly large . . . If you do not expect to work hard and carefully, you are in the wrong place.” credit: Northern Illinois University]

The Marketing Brain Behind the Big Ben

The massive success of the Big Ben design wasn’t just about function and style. Good old fashioned branding played a major role, as well. In the comprehensive “Big Ben & Baby Ben Identification Guide,” organized by researchers Richard Tjarks and Bill Stoddard, they credit the original brilliant marketing of these little wonders almost entirely to one man—a 28 year-old French immigrant named Gaston Le Roy.

Initially hired as a low level clerk, Le Roy worked his way up the company ladder in the early 1900s as an on-the-road sales rep, soliciting business from Chicago to New York to parts unknown. Soon, he was running the Western Clock Co. advertising department, and proving his worth with some clever marketing strategies. With George Kern’s new alarm clock, specifically, Le Roy decided it would be wise to craft a new brand name, and to leave the Western name off of the clock face entirely, since the company was overly associated with cheap goods at the time. In its place, he ironically dubbed the little bedside clock “Big Ben” (apparently not copyrighted by the British Parliament), and introduced it to the public in early ads as a gendered “he” instead of an “it.”

“Big Ben is a handsome, well built, refined and bright looking fellow with a clean-cut open face and a deep cheerful voice,” one ad read. “A well-dressed, steady and punctual chap, up to the minute and always on the job.”

“Big Ben always comes to you straight from home, LaSalle, Illinois,” read another. “But he only comes upon receipt of signed price agreement. We pay his railroad fare on all orders for a dozen or more, we brand him with your name in lots of 24.”

When many of these early Big Ben advertisements were still running, Gaston Le Roy’s life took a sudden and dramatic turn. While promoting Westclox products in Europe, the breakout of World War I and the laws of mandatory military service in his native France forced Le Roy to get his affairs in order and head for the front in 1914. He corresponded with Westclox General Manager Ernst Roth over the weeks that followed, but after a final letter that September, he went silent.

The next month, Roth got a cablegram from London; his friend and valued co-worker Le Roy had “died for his country.” Those simple words, Roth later wrote in the November 1914 issue of the company newsletter, Tick Talk, “unconsciously characterized the man—unaffected, direct, devoted to his cause.”

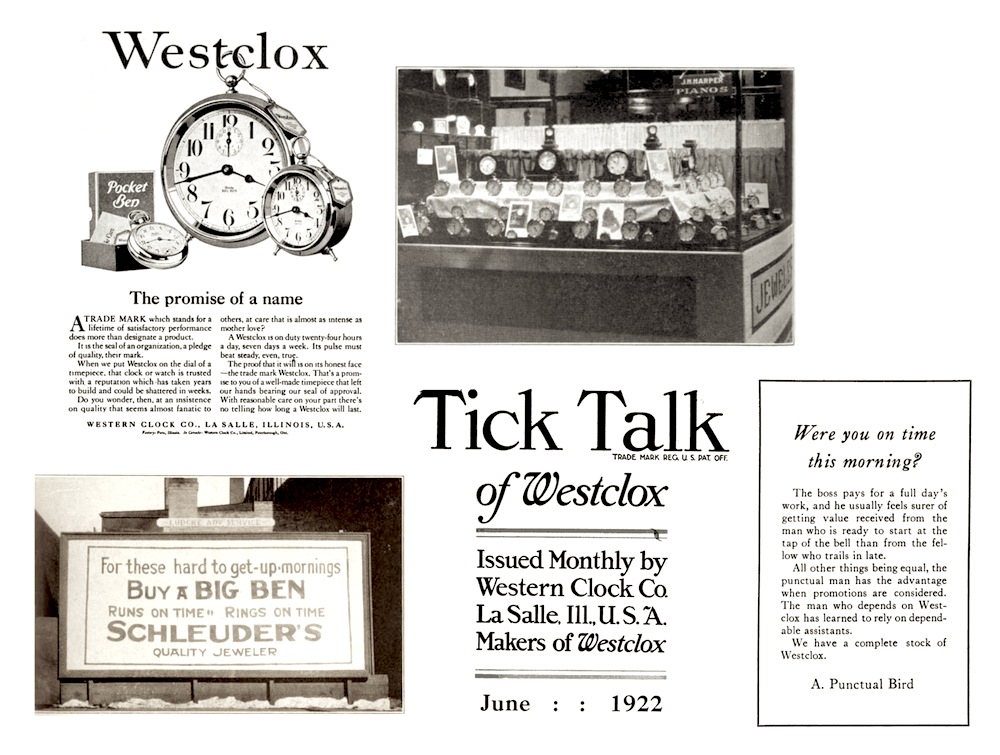

[Images from a 1922 issue of the Westclox company newsletter, the very cleverly titled “Tick Talk”]

[Images from a 1922 issue of the Westclox company newsletter, the very cleverly titled “Tick Talk”]

The end of the Great War began what was, in many respects, a halcyon time for Westclox, now arguably the best-known timekeeping brand in the world. Ironically, the war that had cost them Gaston Le Roy had also stifled much of the company’s European competition, opening up an even bigger share of the world marketplace in the 1920s.

Through it all, Peru remained the company’s home base, as over 3,000 employees now enjoyed the rapidly expanding space of the factory and its attached campus, with gardens, tennis courts, a bowling alley, and other things worthy of a Matthiessen estate. These efforts, combined with an ahead-of-its-time factory welfare department and employee benefits packages, led to a lot of workers spending their whole lives with Westclox. One employee, R.D. Patton, had joined Charles Stahlberg’s original start-up back in 1886 at the age of just 13, and he was still on board in 1936, 50 years later.

“Ghost Girls”

Not everyone involved with the manufacturing of Westclox products was employed directly by Westclox, however. In the early 1920s, when the company introduced a new series of Big Ben and Baby Ben clocks with “luminous” dials, the work of painting on this special, glow-in-the-dark element was outsourced to the Radium Dial Company—an independent business located just up the road in the neighboring town of Ottawa, IL.

The “magical glow,” as was widely understood by everyone involved, was created by radium—a radioactive element discovered by Marie Curie in 1898. It’s hard to fathom in retrospect, but in the early 20th century, it was generally believed that small amounts of radium were perfectly harmless to humans, and thus, the substance’s natural, long-lasting glow actually made it something of an attractive novelty of the time period—not just on clock dials, but in the worlds of quack medicine, fashion, cosmetics, and even a proto version of energy water, called “Radithor.”

The “magical glow,” as was widely understood by everyone involved, was created by radium—a radioactive element discovered by Marie Curie in 1898. It’s hard to fathom in retrospect, but in the early 20th century, it was generally believed that small amounts of radium were perfectly harmless to humans, and thus, the substance’s natural, long-lasting glow actually made it something of an attractive novelty of the time period—not just on clock dials, but in the worlds of quack medicine, fashion, cosmetics, and even a proto version of energy water, called “Radithor.”

When the Radium Dial Company moved to Ottawa in the ’20s to better serve its number one client, Westclox, they were welcomed with enthusiasm, particularly by the young, working class women in the town. The precise, delicate skill of painting clock dials with radium powder promised a much higher salary than most factory jobs available to women at the time (upwards of $18 a week), and the company soon employed as many as 200 female workers in its Ottawa plant.

In her 2017 book, The Radium Girls: The Dark Story of America’s Shining Women, author Kate Moore notes that many of the new girls at the Radium Dial factory started out painting the famous Westclox Big Ben clocks before moving on to the smaller and more challenging Baby Ben, and finally the Pocket Ben and Scotty pocket watches, all produced at the Westclox Works.

“Radium’s luminosity was part of its allure,” Moore writes. “The dial painters soon became known as the ‘ghost girls’ — because by the time they finished their shifts, they themselves would glow in the dark. They made the most of the perk, wearing their good dresses to the plant so they’d shine in the dance halls at night, and even painting radium onto their teeth for a smile that would knock their suitors dead.”

The Ghost Girls might have been the envy of the other girls in town, but no one yet realized just how much danger they were being subjected to. Behind the light, they’d been left in the dark. The standard operating procedure of their daily work involved literally placing radium flecked paint brushes between their lips to create a finer point before application. They were, incredibly enough, instructed to ingest a radioactive poison all day, every day, and never properly warned of any potential hazards.

“When I went home and washed my hands in a dark bathroom, they would appear luminous and ghostly,” an original Ghost Girl named Catherine Donohue (nee Wolfe) later testified. “My clothes, hanging in a dark closet, gave off a phosphorescent glare. When I walked along the street, Iwas aglow from the radium powder.”

[Mrs. Charlotte Purcell, like Catherine Donohue, was one of 15 former workers at the Radium Dial Company who contracted cancer and sought justice in the late 1930s]

[Mrs. Charlotte Purcell, like Catherine Donohue, was one of 15 former workers at the Radium Dial Company who contracted cancer and sought justice in the late 1930s]

Donohue, like many of her young peers in the radium industry, eventually realized that her amusing glow had been a warning of severe exposure to a radioactive substance. Over time, she contracted terrible cancerous tumors, lost most of her teeth, and suffered countless other health problems. Dozens of radium dial painters around the country developed similar symptoms, although the effects could take years to manifest, making it more difficult to pinpoint the phenomenon from its first cases in the early 1920s. As the dark cloud of fear and suspicion grew over the small town of Ottawa into the ’30s, the Radium Dial Company itself refused to take any responsibility, claiming innocence and ignorance.

Finally, with Catherine Donohue serving as a key witness from her death bed in 1938, a groundbreaking Supreme Court case finally delivered some long awaited justice to the victims. As Kate Moore explains it, “The radium girls’ case was one of the first in which an employer was made responsible for the health of the company’s employees. It led to life-saving regulations and, ultimately, to the establishment of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which now operates nationally in the United States to protect workers. Before OSHA was set up, 14,000 people died on the job every year; today, it is just over 4,500. The women also left a legacy to science that has been termed ‘invaluable’.”

Because it was one degree removed from the radium business itself, Westclox seems to have largely dodged the controversy and lawsuits altogether. The greater surprise, though, is that they didn’t abandon the use of radium in the years that followed. While the painting technique of the Ghost Girls was replaced with supposedly safer methods like silk screening, traces of radium were still used by many companies to get that desired glow effect throughout the 1940s and even as late as the ’60s. Just as pilots in World War II had radium on the dials in their cockpits for all-condition visibility, many people who purchased Big Ben alarm clocks during the same period—including the very style in our museum collection (made from 1939-1946)—went to bed each night sleeping next to a tiny box of radioactivity.

Importantly, the health risks tied to these old clocks is generally believed to be quite minimal, so long as one avoids long-term exposure or directly ingesting the paint as the Ghost Girls had. Even so, our case-less dials are certainly best left behind glass and out of reach, a sad reminder of a terrible and preventable episode in industrial history, the effects of which continued to plague the town of Ottawa for many years afterward.

Times of War

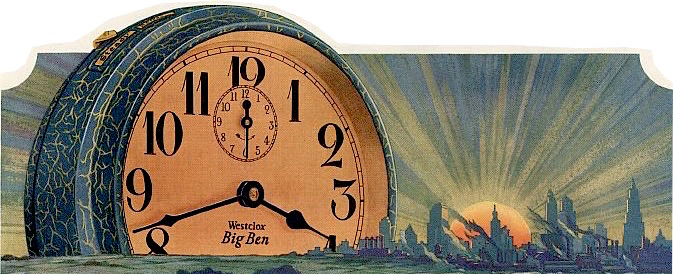

As radium luminosity came under attack in the 1930s, Westclox’s other updates to the Big Ben design were far more practical and uncontroversial. At the start of the decade, the company brought in a skilled new industrial designer named Henry Dreyfuss; a true modernist. Seeking the Big 3 goals of convenience, cleanliness, and cheap production, Dreyfuss rolled out his new-look Big Ben in 1931.

The new features, according to a synopsis from the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum, included: “shifting from serif to sans-serif typefaces and from slightly ornate to more streamlined minute and second hands, all of which eased legibility; setting the clock face closer to the glass, reducing shadows; and creating a slightly smaller form overall.”

Dreyfuss revised his changes at the end of the decade, designing the Style 5 and 5a Big Bens in 1938—including the featured Loud Alarm dials from our museum collection. That batch was in production non-continuously from 1939 to 1946, housed in gunmetal cases with nickel trim. While most of our Big Ben dials are black with luminous numbers, there were also white dials with black numerals in production at the same time.

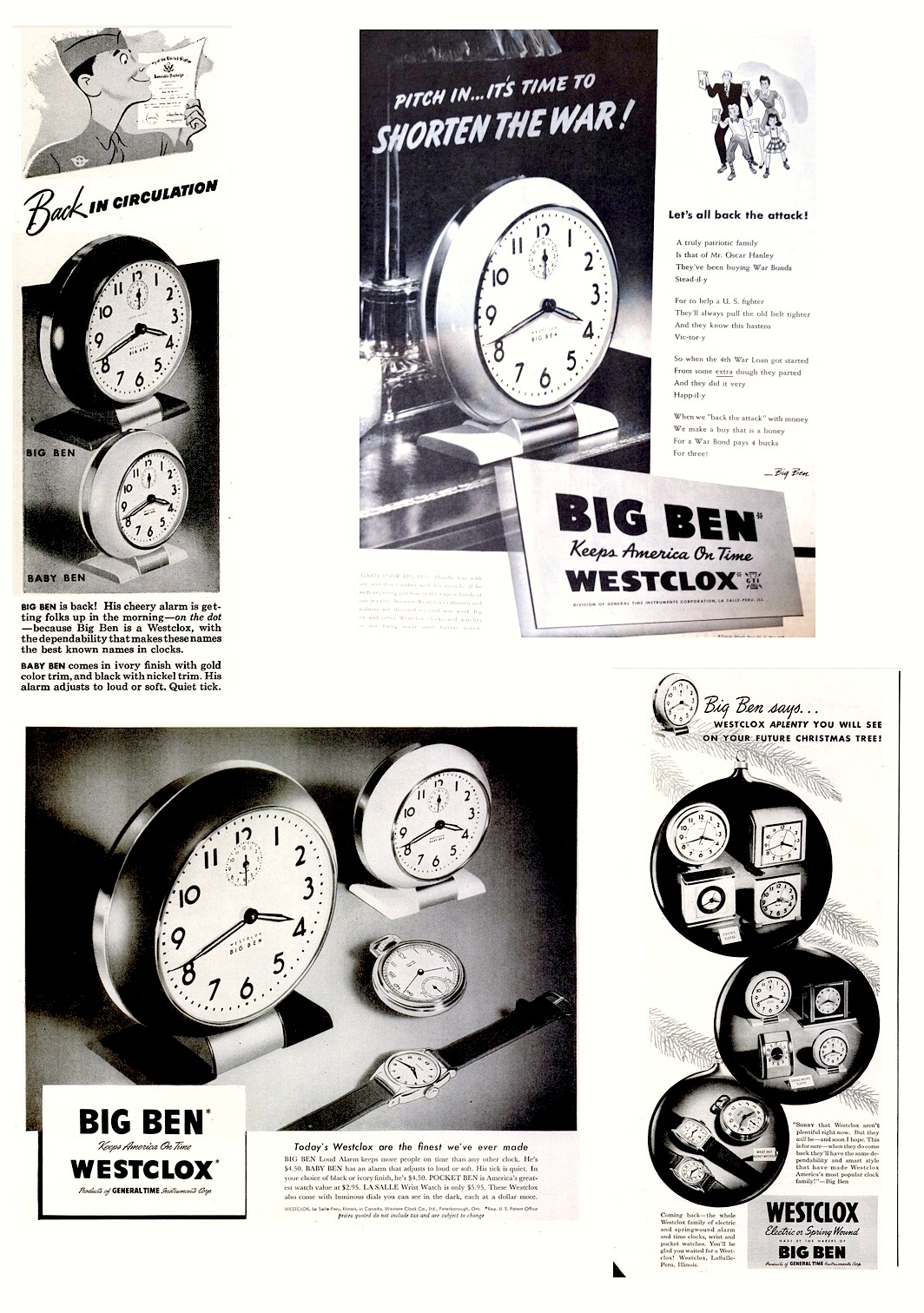

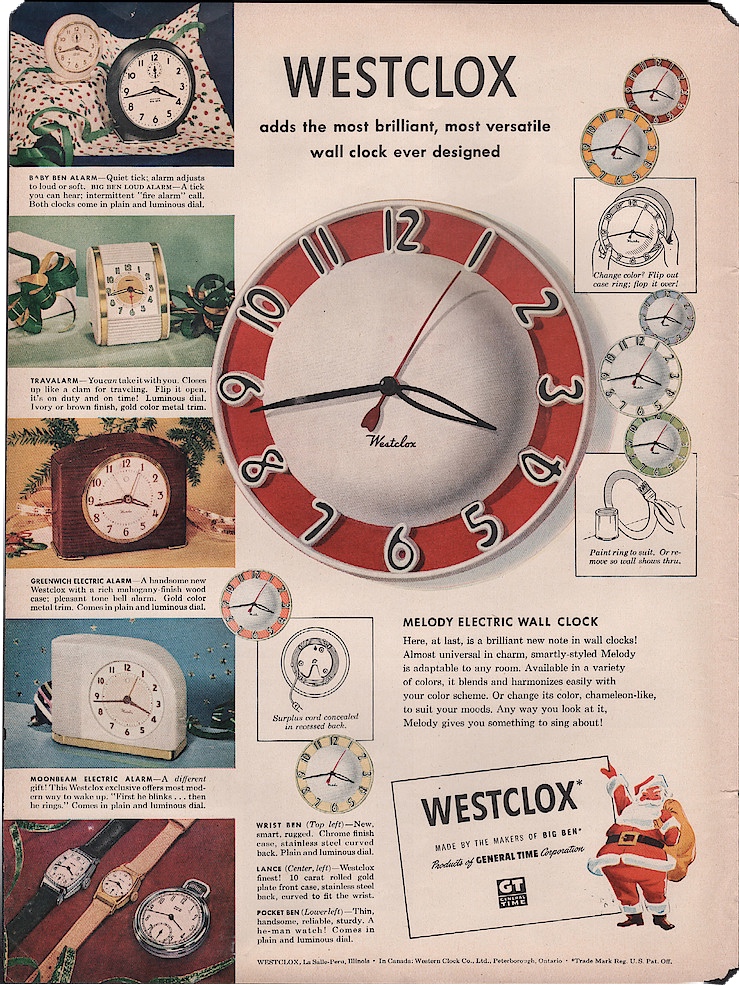

[Westclox advertisements from WWII period, ft. Style 5 dial design]

[Westclox advertisements from WWII period, ft. Style 5 dial design]

Despite Westclox’s deep German roots, the Illinois factory was a huge contributor to the U.S. military again during World War II, supplying upwards of a billion small parts for use in various defense products.

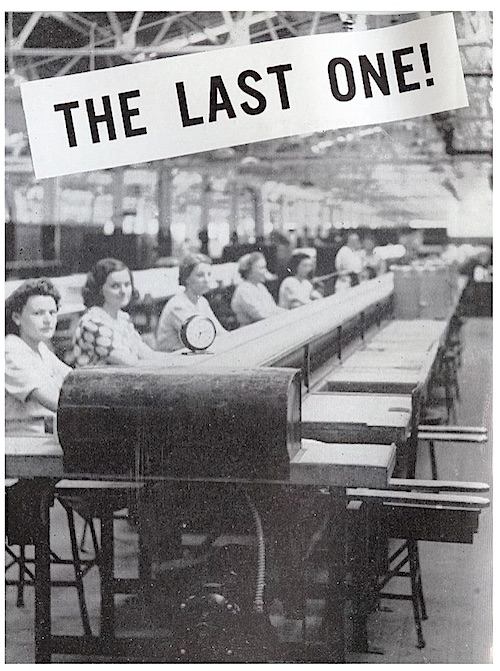

As seen below, the company made something of a symbolic gesture out of honoring the “last Big Ben” to roll off the assembly line on July 31, 1942, the day when all production shifted to government contracts for the duration of the war.

Technically speaking, though, Westclox did still produce clocks during the gap years that followed. In fact, one of their designs for the military, the terrifying sounding “WarAlarm,” spurred a small shopping riot in Chicago in 1944 when a small batch of the clocks was made available for commercial purchase at a downtown store.

Technically speaking, though, Westclox did still produce clocks during the gap years that followed. In fact, one of their designs for the military, the terrifying sounding “WarAlarm,” spurred a small shopping riot in Chicago in 1944 when a small batch of the clocks was made available for commercial purchase at a downtown store.

Ruth Spayer at the Westclox Museum tracked down a newspaper story from the Daily Post-Tribune on March 21, 1944, describing a scene in which “three women fainted, several clerks were trampled, and four showcase windows were shattered before police untangled a jam of 2,500 women and a few stout-hearted men who converged on the store.”

Never underestimate the value of an alarm clock when yours broke two years ago and nobody has manufactured a new one since.

Into and Out of the Ashes

Production was back in full force and at an all-time high by 1956, with 3,000 employees on staff. As the 1960s began, over 50 million Big Ben clocks had been produced in total, and additional Westclox plants were now in operation everywhere from Athens, Georgia, and Ontario, Canada, to Scotland and Australia. As various larger corporate interests got involved in the years ahead, however, and as increasing competition from electronic clockmakers slowed the Big Ben’s dominance, the inevitable slow down began.

Production was back in full force and at an all-time high by 1956, with 3,000 employees on staff. As the 1960s began, over 50 million Big Ben clocks had been produced in total, and additional Westclox plants were now in operation everywhere from Athens, Georgia, and Ontario, Canada, to Scotland and Australia. As various larger corporate interests got involved in the years ahead, however, and as increasing competition from electronic clockmakers slowed the Big Ben’s dominance, the inevitable slow down began.

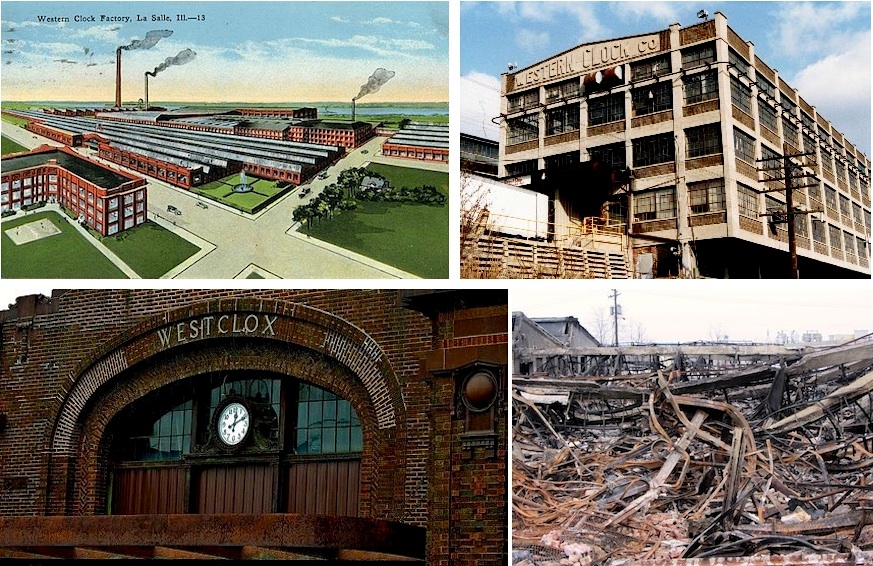

On March 31, 1980, the Peru-LaSalle plant was officially closed, narrowly missing its 100-year anniversary.

The Westclox building remained there in all its glory well into the 21st century, as plans were tossed around for some sort of repurposing of the huge, historic facility. Then, on New Year’s Eve, as 2011 became 2012, the unthinkable happened. A pair of teenage boys broke into the abandoned factory and set a fire that quickly spread and enveloped much of the central complex. For the town of Peru—which had tied much of its identity to Westclox for the better part of a century—the damage went beyond financial.

Fortunately, in the years since, there’s been a noble effort to retain surviving parts of the building and some of the important local history that the empty factory once represented. A Westclox Museum has been opened within the original facility, showing off rare collections from the millions of timepieces once manufactured there.

A 2015 article by Ben Hohenstatt in the Illinois Valley’s News Tribune included interviews with a few former Westclox workers who returned to see the museum and remember old times.

Excerpt from 2015 News-Tribune piece by Ben Hohenstatt:

Westclox closed its Peru factory 35 years ago.

This past weekend, thanks to the Westclox Museum, its doors were opened and former workers were welcomed back for Homecoming Day. This fall, the museum will be open more frequently and for more events.

“We’re finally at a point, where we’re ready to do more than just sit here,” said Ruth Spayer, curator for the museum.

Former employees showed up to view a collection of watches, clocks, tools, photographs of the old factory, a short black and white film of the factory in action and remember working for Westclox.

Richard Ristau Jr., former plant manager, said he’s happy to see the space being used for the museum.

“These folks here that are responsible for this are doing a marvelous job,” Ristau said. “I worked here for 28 years. My father (Richard Ristau Sr.) worked here for 48.”

Don Spayer, volunteer and former Westclox employee, said the bulk of the museum’s collection was built through donations.

Ristau said he remembered when the Westclox factory was “the heart of the city”, and recalled enjoying his time with Westclox.

“The thing I remember most is working with the people,” Ristau said. He also recalled playing in the factory.

The factory contained a bowling alley, and Ristau said his father was an excellent bowler.

“My dad was one of the top bowlers here,” Ristau said. “I spent many an evening here, watching him bowl.”

Art and Mary Ann Windy [pictured] have been married for 49 years, met as Westclox employees and were present for the open house.

[Former Westclox workers Art and Mary Ann Windy (standing), 2015]

[Former Westclox workers Art and Mary Ann Windy (standing), 2015]

“This is amazing,” Art said. “I never realized, even working here, they made so many different models.”

Among the rarities on display is a Westclox-made National Emergency Alarm Repeater.

“It might be the only one in the country,” Spayer said.

The Windys said their union confirms an old Westclox employee rumor about the long-lasting nature of a relationship struck up near a certain fountain.

“Next year, we’ll have been married for 49 years,” Mary Ann said. “The drinking fountain worked.”

*****

Going back further in time, here is a pretty hypnotizing silent film released by Westclox in the early 1920s to promote the Big Ben and other products.

Sources:

“Westclox Big Ben and Baby Ben Identification Guide” – ClockHistory.com

“Keeping Time in Peru” – Chicago Tribune, October 18, 1998

“Remembering the Great War” and “The Clock That Caused a Near Riot” – WestcloxMuseum.com

“For That Healthy Glow, Drink Radiation” – Popular Science, August 17, 2004

The Radium Girls: The Dark Story of America’s Shining Women, by Kate Moore, 2o17

“The Forgotten Story Of The Radium Girls, Whose Deaths Saved Thousands Of Workers’ Lives,” by Kate Moore, Buzzfeed.com

“One-Day and Alarm Clocks” – Commercial America, Vol VI, 1909

“Big Ben Clock, 1931” – Cooper Hewitt

“A Rude Awakening: The History of Alarm Clocks” – ThroughoutHistory.com

Does anyone know how many pieces are in a big ben wind up clock?

I have come across a weastern clock (nice) 30 hour clock. Might be an ormolu.Research shows it sold for $1.10. Not sure of age and can’t’ find numbers. Does anyone have an insight on this? I did get it running and it has held time for 2 days. Condition is great. Any Idea of age and value.

I would like to know the value of a #4 black, #321(in original cardboard Christmas box), mint condition, Baby Ben alarm clock is.

My Grandmother had a Westclox in her house. I was about 3ft high and recessed into the wall. At the top was a clock covered with a glass door. I think the clock was electric but could have been a wind up or maybe even a pendulum. It had beneath that four long tubes and they were the chimes for the door bell. they played a deep rich tone. I have been searching for one like as the clock went with the house after my Grandmother passed away. Can anyone direct me on how to find this clock?

How much is this alarm click worth today

i use a 1980s I believe westclox pocket ben sweep 2nd hand, I actually had a westclox bullseye from the early 1990s when I was in elementary school

This was a wonderful article to read. Thank you.

Did westclox stop using radioactive paint by the 1960’s?

Hi I need the face plate for a black face big ben with the alarm dial on its face do you have any you could sell me alonf with the radio dials

it was probably outsourced meaning westclox sold some watches to hot wheels, I had a westclox electric dialite like that

I bought a 1970s Westclox pocket watch with a Hotwheels face that says authorized seller on it. Is this a product that the company would have made or something someone created? I’m trying to determine if it is a legit or reproduction that someone made.

I have a Westclox Magnet Key Part number 031723 I think was used to open a door as it has an arrow on 1 end. it’s about 2 inches long maybe 1/2 in thick with holes on either end to be worn on a key chain perhaps? it’s a Gold coloring and the bottom is well worn like it was slid into something regularily. It is encased in hard polymer Plastic and the ends have rivets . Can someone get back to me as to what it is and possibe age of it.

CAN SOMEONE TELL ME HOW TO RELEASE THE CLICK ON A WESTCLOX MAN’S WRISTWATCH MODEL A-201?

THANK YOU

MIMI V.

who can refurbush big ben still runs good perfect time purchased in 1950 cataloge #885(885)

Do you have an archival dept who could give us an idea of our Western Clock which we recently acquired?

I have a small westclox alarm clock. I cannot date it. The only thing I found is the word Germny engraved on the back. I believed it was manufacturing tag. Was westclox ever manufactured in germany and if so when?

I had developed some sort of fascination for Big Ben and Baby Ben clocks. I have been purchasing these clocks as and when I got an opportunity. I have a quite a few pieces of both of them I have even one big Ben pocket watch which is still working after , I do not know how many years. I am a retired mechanical engineer, the quality has floored me, hats off to this company.

I was pained to learn how the girls had suffered while working here and sacrificed their lives to give the name of the company which it has today.