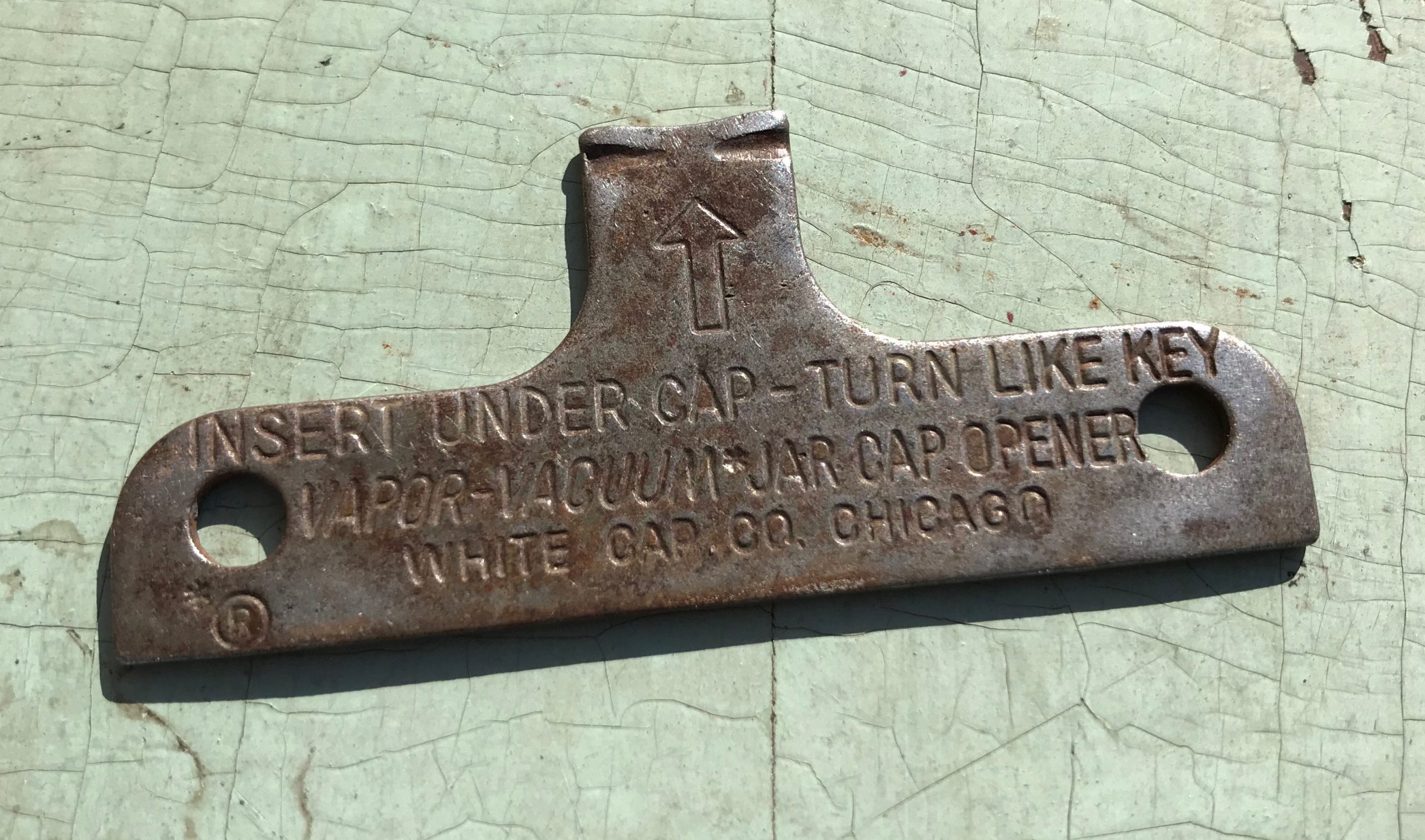

Museum Artifact: Vapor-Vacuum Jar Cap Opener, 1950s

Made By: White Cap Company, 1819 N. Major Ave., Chicago, IL [North Austin]

If you want to start a successful business, invent a solution to one of mankind’s great conundrums. If you want to stay in business, be ready to fix all the new problems your solution creates.

Back in 1930, a small Goose Island start-up called the White Cap Company introduced its “Vapor Vacuum” lid sealing system—a revolutionary new steam-based method for preserving the freshness and flavor of bottled commercial foods. From ketchup to pickles to baby food, dozens of suppliers raced to incorporate the new technology into their glass bottling plants, and as a result, the White Cap Co. emerged as that rarest of things in the Great Depression—an overnight success story.

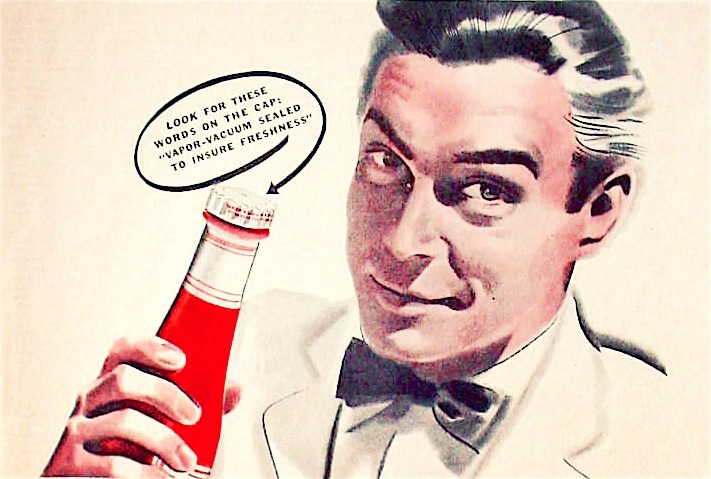

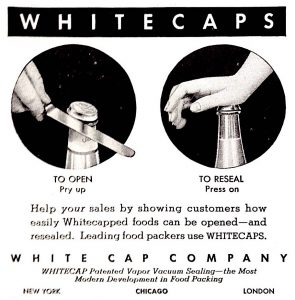

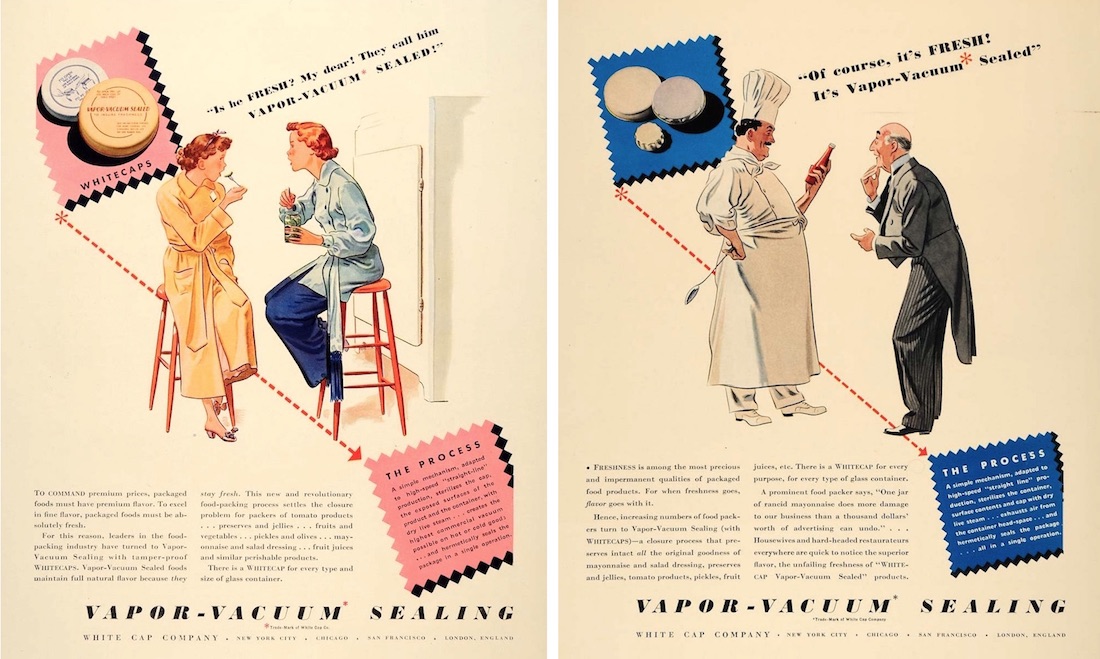

[1938 advertisement for White Cap Co’s “Vapor-Vacuum” Sealing System]

[1938 advertisement for White Cap Co’s “Vapor-Vacuum” Sealing System]

There was one small, unanticipated complication, however. As grateful as grocers and homemakers were for the crispier pickles, they were substantially less enthused about the Herculean effort now required to open up all these new vacuum-packed jars. The standard bottle openers on the market weren’t well equipped for it, and while certain sharp-edged utensils could get the job done, sword-fighting with a heavy glass container didn’t exactly sound like the final realization of an American dream.

White Cap Co. founder and president William (W.P.) White—along with his brothers and business partners George and Phil—knew that tackling this issue could be critical to the long term success of the Vapor-Vacuum process and its related jar caps. So, after years spent creating the ultimate lockdown closure, they went into reverse-engineering mode, looking for the perfect counter-solution. With help from the Heinz Company, a prototype vacuum cap remover was developed in 1941, but metal rationing during World War II scrapped the project before it went into mass production.

White Cap Co. founder and president William (W.P.) White—along with his brothers and business partners George and Phil—knew that tackling this issue could be critical to the long term success of the Vapor-Vacuum process and its related jar caps. So, after years spent creating the ultimate lockdown closure, they went into reverse-engineering mode, looking for the perfect counter-solution. With help from the Heinz Company, a prototype vacuum cap remover was developed in 1941, but metal rationing during World War II scrapped the project before it went into mass production.

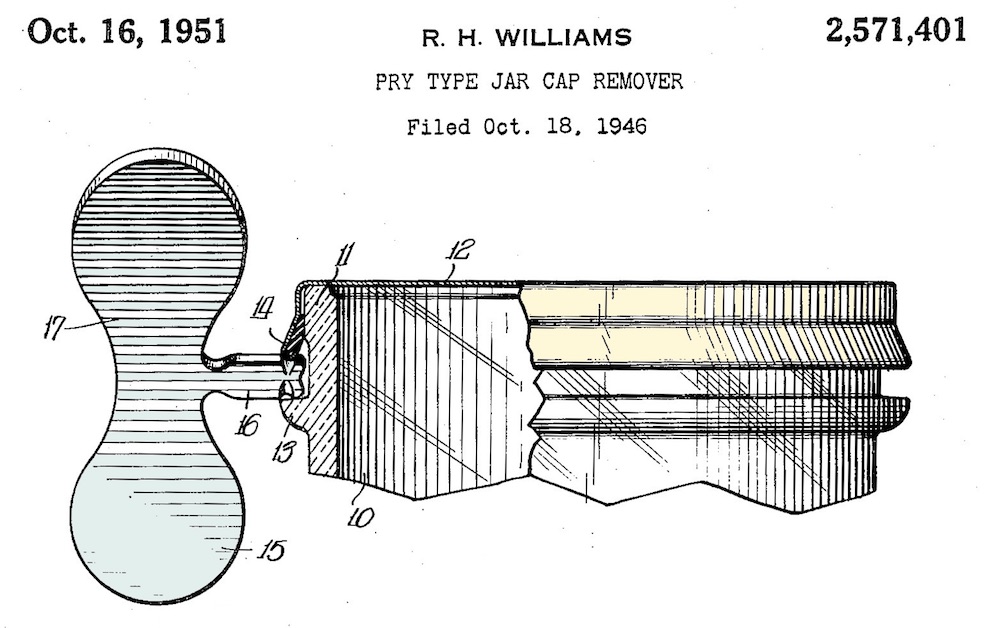

Finally, in 1946, an inventor named Raymond H. Williams—working under the White Cap banner—applied for a U.S. patent on a device he called the “pry type jar cap remover.” This simple T-shaped, turn-key design evolved into White Cap’s original “Vapor-Vacuum Jar Cap Opener” in the early 1950s, and the artifact in our museum collection is one of those early models.

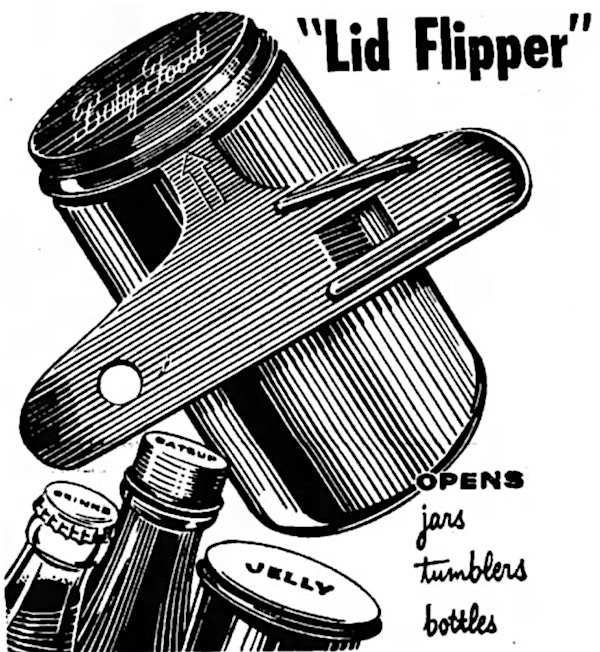

A few years later, when a hook was added to the back of the tool for tumbler style container lids, the opener was re-christened the “Lid Flipper,” and a full-blown media blitz ensued.

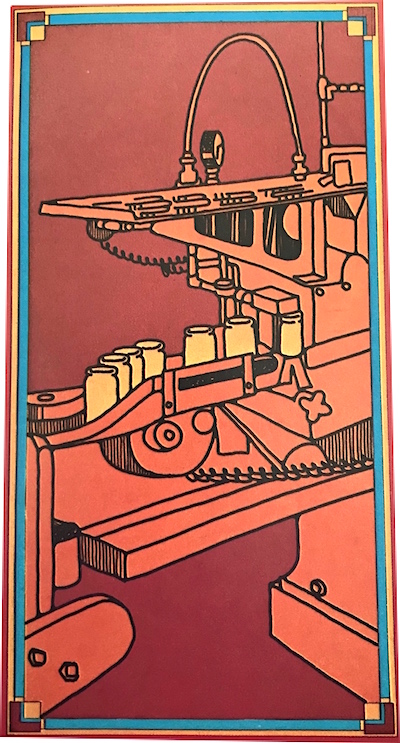

[Raymond Williams’s 1946 patent drawing of the Pry Type Jar Cap Remover, assigned to the White Cap Company]

[Raymond Williams’s 1946 patent drawing of the Pry Type Jar Cap Remover, assigned to the White Cap Company]

Enough to Flip Your Lid

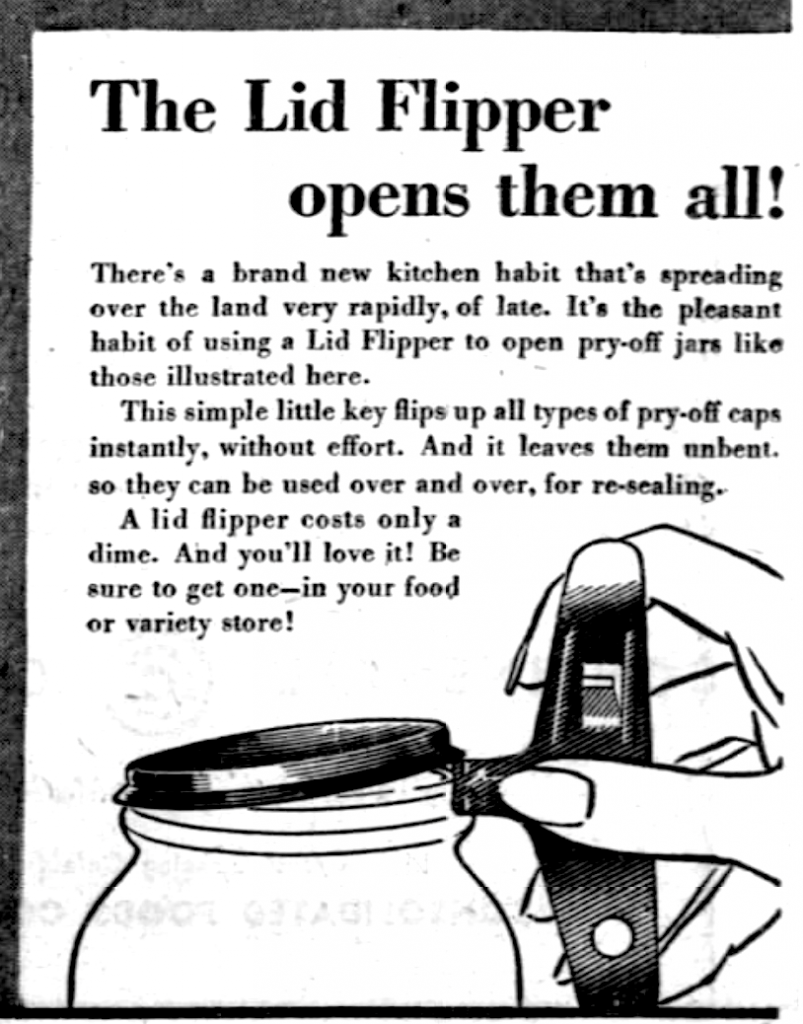

“They’ve finally developed a gadget to flip the lid of glass jars with pry-off caps,” the International News Service reported in February of 1955. “Instead of damaging your spoons or struggling with regular bottle openers, this new 10-cent ‘Lid Flipper’ makes the job easy because it’s specially made for the job. It’s made, incidentally, by the nation’s largest maker of pry-off caps for glass food containers—White Cap Co., Chicago.”

Technically speaking, White Cap actually outsourced the manufacturing of its lid flippers to another Chicago-based kitchen appliance colossus—the Ekco Products Co. But that doesn’t change the premise much.

“Last year, each family of four bought an average of about 100 glass packages with pry-off caps,” according to a 1955 issue of the Journal of Home Economics. “The lid flipper provides scientifically calculated leverage so that an easy twist provides the ‘lift’ that breaks the vacuum and raises the cap without bending it. ‘The cap is left in perfect condition for resealing,’ says the White Cap Company.”

“Last year, each family of four bought an average of about 100 glass packages with pry-off caps,” according to a 1955 issue of the Journal of Home Economics. “The lid flipper provides scientifically calculated leverage so that an easy twist provides the ‘lift’ that breaks the vacuum and raises the cap without bending it. ‘The cap is left in perfect condition for resealing,’ says the White Cap Company.”

White Cap certainly seemed invested in the Lid Flipper revolution. Not only did they put in production orders for 60 million of the things, but they also had instructions re-printed on more than 700 million lids coming out of the Chicago factory. Where they once said “To Open, Pry Up,” they would now say, “To Open, Use Lid Flipper.”

It was official; the Lid Flipper was a new sensation of the Eisenhower age. If you didn’t have one, it was on your agenda to get one. Nothing could stop its ascension into the pantheon of kitchenware necessities. . .

But then—like the tragic loss of James Dean that same cruel autumn of ’55—a twist of fate brought our hero’s journey to a sudden and premature end.

The twist, quite literally, was the nearly simultaneous debut of the quarter-turn “Twist-Off” lug closure—a superior technology (distinct for a plastisol gasket) that cruelly undermined everything the Lid Flipper stood for. By the end of the 1950s, “The Twist” wasn’t just the biggest dance craze in the country, it was the prevailing trend in the glass bottle biz, joining other roll-on caps and lug caps to effectively render all extraneous jar opening tools obsolete.

You might presume that the White Cap Company was blindsided and devastated by this development, but—in the biggest surprise twist of all—they’d actually been the ones behind it! The Twist-Off cap, you see, was a product of White Cap’s very own R&D department, patented by research director Donald H. Zipper, and presided over by William White’s own sons, William Jr. (company vice president) and Roger B. White (R & D head). Rather than a death blow to the business, the tool-free cap removal era was, instead, their next cash cow.

So, why did White Cap push the Lid Flipper out to market in the mid ’50s when the Twist-Off was already in development?

Well, I suppose the White family had probably learned from experience to start solving the obligatory “next problem” before it was created. The Twist-Off had actually experienced a few malfunctions in its early test runs, so while Donald Zipper worked on fine-tuning the plastisol gasket, his bosses decided to promote a stop-gap product. Basically, if you can make a jar opener for a nickel and sell it for a dime, you might as well do so before everyone figures out they won’t be needing it. In other words, be your own best competition.

Well, I suppose the White family had probably learned from experience to start solving the obligatory “next problem” before it was created. The Twist-Off had actually experienced a few malfunctions in its early test runs, so while Donald Zipper worked on fine-tuning the plastisol gasket, his bosses decided to promote a stop-gap product. Basically, if you can make a jar opener for a nickel and sell it for a dime, you might as well do so before everyone figures out they won’t be needing it. In other words, be your own best competition.

During this same period, in 1956, White Cap further raised its position in the industry by going international as a new subsidiary of the Continental Can Company. It was all a far cry from those humble days on Goose Island.

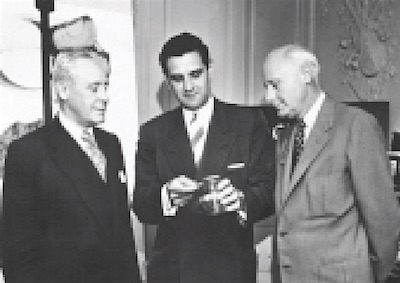

[From left to right: Bill, George and Phil White, founders of the White Cap Co.]

[From left to right: Bill, George and Phil White, founders of the White Cap Co.]

The Early Days of the White Cap Co.

Brothers William and George White (Philip joined later) organized their little family business in 1926, with the goal of developing W.P.’s novel idea for a new Side Seal / Pry-Off cap; an improvement on the standard screw tops of the period. William (b. 1885) was no newbie to the closure game. He’d already risen to the office of vice president with New York’s Anchor Cap and Closure Corp., and had a clear vision of how he wanted to run his own vacuum closure business in Chicago—albeit with limited capital to start from.

According to legend, the brothers rented out two floors of an old box factory on the river, and hired a team of just a dozen workers to roll out their first million caps. The pipes in the building had to be thawed every morning before work could get started, and most of the power was generated by stereotypical 1920s ambition.

[An early White Cap Co. trade show display, c. late 1920s]

[An early White Cap Co. trade show display, c. late 1920s]

Fortunately, the company gained enough traction to survive the market crash of 1929, as its Side Seal cap—which featured a rubber gasket that made it resealable—found a loyal following.

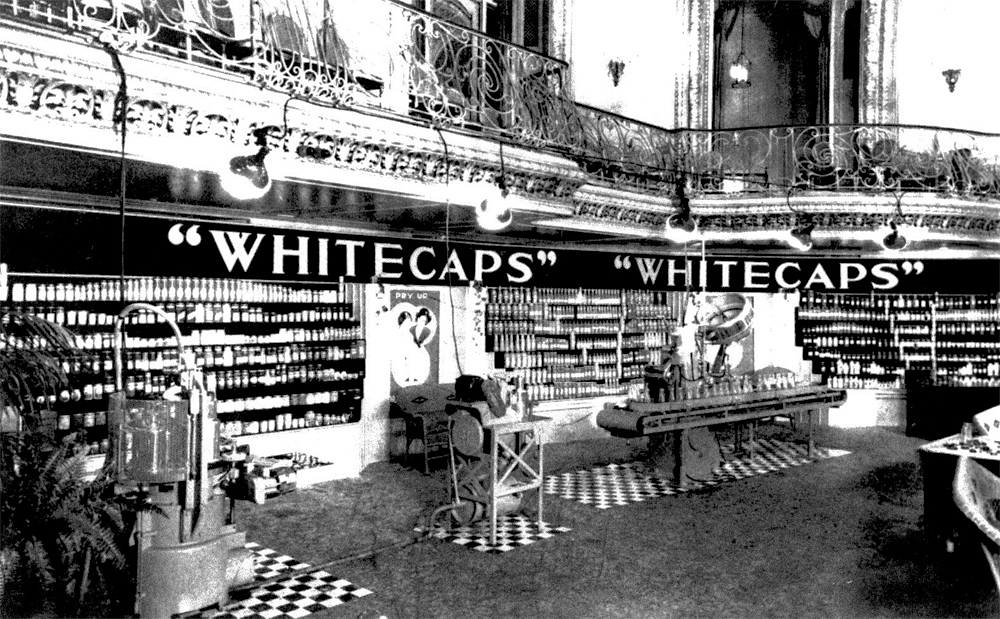

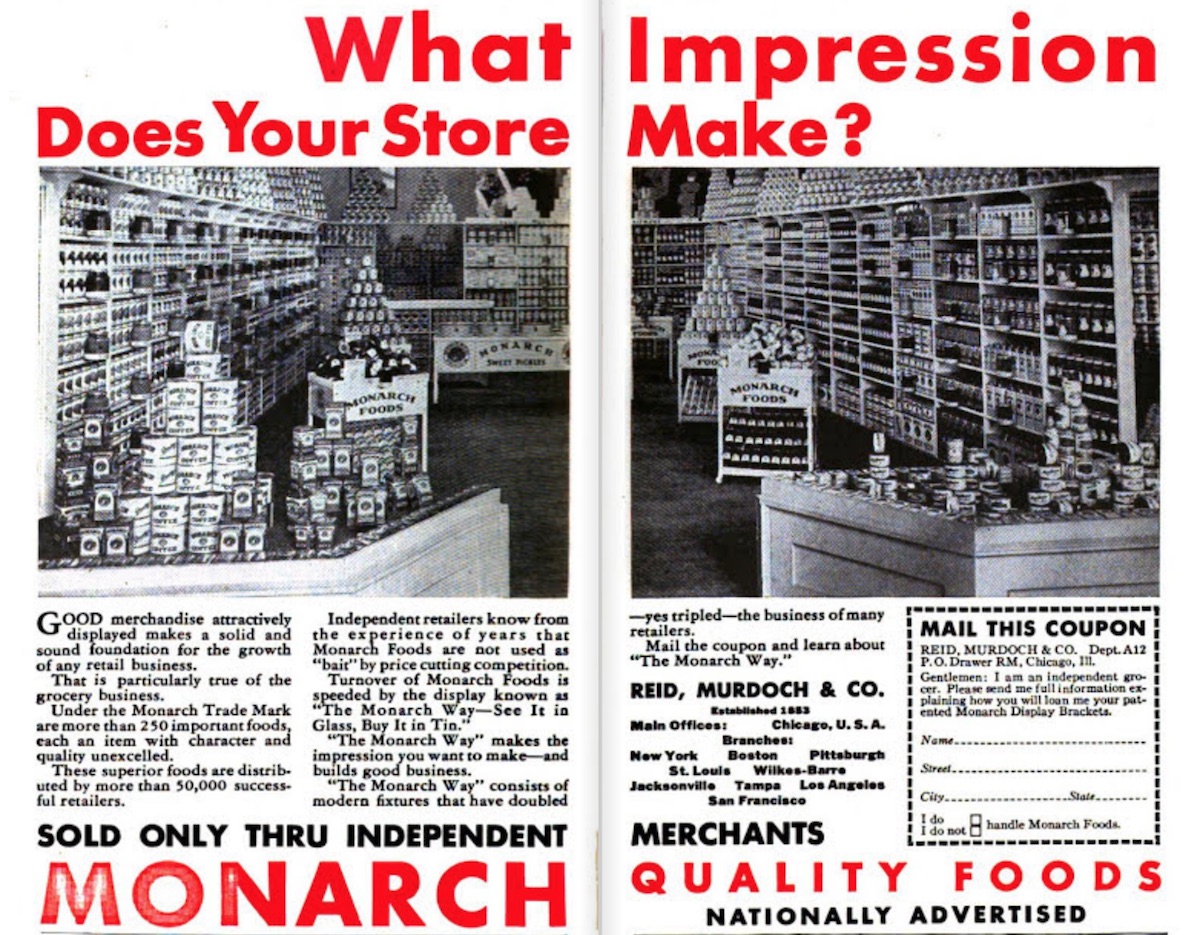

One of White Cap’s first big clients was the Chicago wholesale grocery giant Reid, Murdoch & Co., which used glass jars in its store displays to show customers the actual contents of foods generally sold in opaque tins. The company’s “See It In Glass, Buy It In Tin” campaign required glass jar closures that would keep the display food looking pretty for as long as possible, and the White Cap Co. won the account—a major windfall.

[Reid Murdoch’s “See It In Glass, Buy It In Tin” campaign, promoted in this 1930 ad, relied on White Cap’s side-seal closures]

[Reid Murdoch’s “See It In Glass, Buy It In Tin” campaign, promoted in this 1930 ad, relied on White Cap’s side-seal closures]

Vapor-Vacuum, Va Va Voom

At the dawning of the 1930s, when most business were counting their last pennies, White Cap introduced the aforementioned Vapor-Vacuum sealing machine, which instantly turned them from small players into industry leaders. Up to that point in history, food processors relied on large suction pumps to suck air out of each individual jar before lids were attached. It was slow, inefficient, and not even all that effective. The White Brothers, like a jar-capping version of the Wright Brothers, saw a better way.

At the dawning of the 1930s, when most business were counting their last pennies, White Cap introduced the aforementioned Vapor-Vacuum sealing machine, which instantly turned them from small players into industry leaders. Up to that point in history, food processors relied on large suction pumps to suck air out of each individual jar before lids were attached. It was slow, inefficient, and not even all that effective. The White Brothers, like a jar-capping version of the Wright Brothers, saw a better way.

“After extensive experimenting,” the Tribune later reported, “the White brothers discovered that a controlled vacuum could be obtained by distributing steam over the surface of the glass packed food and capping it immediately with a hermetic seal. Then, as the steam condensed, a vacuum was formed.”

The big breakthrough wasn’t just the superior seal, it was the speed at which the machine worked. More than 100 jars could be sealed per minute—unheard of for the time [later improvements would raise that rate to 1,500 jars per minute].

Any business that relied on selling a product in glass jars, from the international food conglomerates to small independent dairies, were now forced to adapt and jump on the bandwagon.

“Bottled milk may be kept sweet almost indefinitely by a preserving process which was demonstrated by its inventor, William P. White of Chicago, at the convention of the National Canners’ Association,” one newspaper reported in 1936. [White is pictured here in a publicity still from that Chicago convention]

“Bottled milk may be kept sweet almost indefinitely by a preserving process which was demonstrated by its inventor, William P. White of Chicago, at the convention of the National Canners’ Association,” one newspaper reported in 1936. [White is pictured here in a publicity still from that Chicago convention]

“The process, which is described as ‘vapor vacuum sealing’ and consists of exposing bottled milk to a vapor of dry steam and then sealing with a metal cap, has been adopted by the dairy farms conducted by the University of Illinois at Urbana, and Ohio State University at Columbus, Ohio, it was announced.

“. . . According to the inventor, ordinances now in force in 625 cities which require that milk be sold within 36 hours after being bottled, may be repealed if this method of preserving milk is adopted by the industry at large.”

The White Cap Company eventually took the fairly unusual step of advertising its creation in mainstream magazines like the Saturday Evening Post, hoping to go beyond the bottling trade to get the word out to other folks concerned with general food quality.

“Housewives and hard-headed restaurateurs everywhere are quick to notice the superior flavor, the unfailing freshness of ‘WHITECAP Vapor-Vacuum Sealed’ products,” one ad read. “There is a WHITECAP for every purpose, for every type of glass container.”

Called Up to the Majors

Naturally, the White Brothers—now flush with cash and changing the world— weren’t inclined to hang around their little Goose Island loft much longer. By the mid 1930s, they’d taken over and expanded a modern factory building at 1819 N. Major Avenue in North Austin, which would remain the company’s home for more than 60 years.

White Cap maintained a workforce of about 200 men and women during the deepest slog of the Depression, but when metal rationing forced hundreds of canning companies to switch to glass bottles during World War II, that workforce boomed to over 1,000 to keep up with new demand. The factory complex itself was further expanded, as well, and a new Research and Development department was created to keep the company ahead of the various industry curves.

[The former White Cap Co. factory at 1819 N. Major Ave. / 1812 N. Central Ave., in use from 1932 through the end of the century, and still standing today]

[The former White Cap Co. factory at 1819 N. Major Ave. / 1812 N. Central Ave., in use from 1932 through the end of the century, and still standing today]

By 1954, when the Lid Flipper was formally introduced, the White Cap Co. produced closures for a whopping 75% of all pry-off style glass containers sold each year. That amounted to about 3 billion caps in all—over a billion of which went on to baby food containers, with another 600 million for jams/jellies and 450 million for pickles. In another couple years, the rise of the Twist-Off would only increase their share of the overall cap market.

With his fortune more than secure, W.P. White had unofficially retired by now into the role of “president emeritus,” with brother George serving as chairman, Philip as president, and William Jr. as vice president. Even after the big sale of the business to Continental Can in ’56, White Cap carried on operating much as it had before, with the family business now buoyed by one of the world’s largest canning empires.

With his fortune more than secure, W.P. White had unofficially retired by now into the role of “president emeritus,” with brother George serving as chairman, Philip as president, and William Jr. as vice president. Even after the big sale of the business to Continental Can in ’56, White Cap carried on operating much as it had before, with the family business now buoyed by one of the world’s largest canning empires.

Eventually, another one of William’s sons, Robert P. White, became president of Continental’s White Cap division, serving in the role from 1961 to 1983. [pictured above: Robert P. White, center, with uncles George and Phil. As a former Air Force pilot, Robert enjoyed personally flying the private company plane to meet with various clients across the country.]

Smell of the Future

Multiple generations of White Cap factory employees started their own family traditions, as well. From its earliest days, the plant on Major Avenue served its workers free soup, coffee and ice cream everyday, and the various additions and improvements to the building over the years kept it up to the latest standards in terms of heating, cooling, fire safety, etc. The only consistent complaint, it seems, involved the “nauseating smell” of the paints and coating materials that protected the millions of caps from contamination. These fumes became part of the daily sensory experience around the industrial area at Central Avenue and Bloomingdale.

“Last summer, after years of complaints tendered with city offices, White Cap, 1819 N. Major, launched a pilot project aimed at getting rid of the smell created through their painting process,” The Suburbanite Economist reported in August of 1962. “It was a new device which literally burned the odors away. . . . ‘We had such good luck with that new device,” said Charles Hayes, plant manager, “that we put in five additional fume-burners and are planning to install three more.’ He added that every so often he does notice the old fumes around the plant but nothing like they used to be.”

“Last summer, after years of complaints tendered with city offices, White Cap, 1819 N. Major, launched a pilot project aimed at getting rid of the smell created through their painting process,” The Suburbanite Economist reported in August of 1962. “It was a new device which literally burned the odors away. . . . ‘We had such good luck with that new device,” said Charles Hayes, plant manager, “that we put in five additional fume-burners and are planning to install three more.’ He added that every so often he does notice the old fumes around the plant but nothing like they used to be.”

I’m sure ingesting those fumes everyday never hurt anybody, and burning them away was probably super safe, as well. But as they say, it was a different time.

A Sense of Closure

A few years after dealing with the stench issue, White Cap made its final warehouse additions to the Chicago headquarters, and by 1967, they had satellite facilities operating in Hayward, California, and Hazleton, Pennsylvania.

Through it all, the famous Twist-Off cap continued to evolve. Along with straight-walled, fluted, and tamper-proof variations of the original quarter-turn model, the company rolled out a new Press-On / Twist-Off cap in 1964 that became the new industry standard. The Press-Seal child resistant cap came around in 1972, and the first all-plastic caps debuted in 1985—around the same time Continental White Cap opened new facilities in Champaign (plastics) and Downers Grove (R&D).

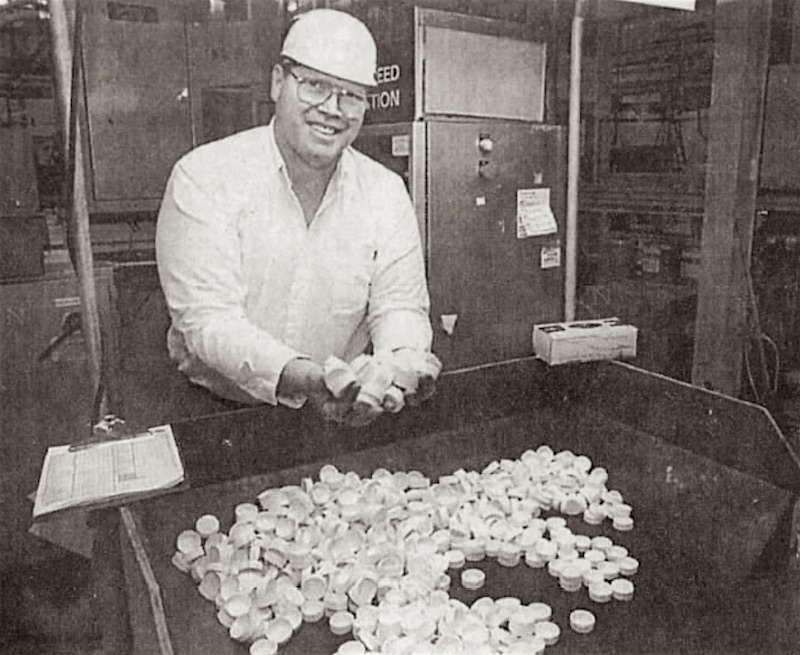

[Craig Hanson, plant manager at White Cap’s plastic cap factory in Champaign, IL, 1998]

[Craig Hanson, plant manager at White Cap’s plastic cap factory in Champaign, IL, 1998]

“Over 90% of our products involve custom design because different market segments have different requirements,” Chicago plant manager Jim Cox told the Greater North-Pulaski Business Times in 1989. “What’s made our company successful is our total system.”

The total system incidentally, was company-speak for (1) making the closures, (2) building and installing the sealing machinery, (3) servicing broken machinery, (4) researching new stuff, and even (5) decorative design consulting.

There were still 900 people employed at the old North Major plant as the 1990s began, and the average length of each worker’s employment was still a stellar 17 years, be it as a machinist, diemaker, engineer, lithographer, etc. The reliability of those jobs finally started coming into question towards the end of the century, however, as a series of confusing corporate sales, takeovers, buyouts, and shake-ups turned the White Cap division first over to a German company (Schmalbach-Lubeca), then an Australian one (Amcor Ltd.), and finally back to an American overlord (Silgan Holdings). Amid the chaos, the Chicago plant was finally abandoned in the early 2000s.

Almost 100 years of history in the can, as they say, and yet, there’s still no guarantee that you’re going to be able to open that pickle jar. Some conundrums die hard.

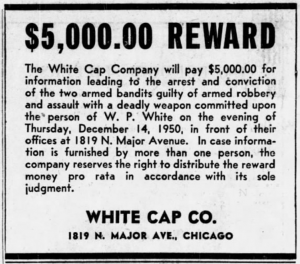

[By 1950, crime was already issue in the North Austin neighborhood]

[By 1950, crime was already issue in the North Austin neighborhood]

SOURCES:

Continental White Cap: The First 50 Years, 1976

White Cap Private Equity Management brochure, 2009

U.S. Patent 2,571,401A – “Pry Type Jar Cap Remover,” 1946-1951

“Champaign Plant Has Closure” – The Dispatch (Moline, IL), Oct 4, 1998

“New Can Opener” – Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan 19, 1951

Historic Bottle and Jar Closures, by Nathan E. Bender

“White Cap Tops Closure Market” – Greater North-Pulaski Business Times, Feb/March, 1989

“Odor Still Pervades Northwest Austin” – Suburbanite Economist (Chicago), Aug 22, 1962

“Robert P. White: 1923-2005” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 10, 2005

“William White, Jr: Manufacturer” – Chicago Tribune, April 18, 2000

“Invents Process to Keep Milk Sweet” – Council Grove Republican (Kansas), Feb 4, 1936

“White Caps Notes 50th Anniversary” – Standard Speaker (Hazleton, PA), May 17, 1976

“Anchor Can and Closure Corporation” – Canning Age, Vol. 3, 1922

“Bottle Opener” – Smithsonian, National Museum of American History

“Designs New Gimmick for Flipping Lids” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 21, 1954

“Lid Flipper” – International News Service / Daily Reporter (Greenfield, Indiana), Feb 4, 1955

“A New Kitchen Gadget” – Journal of Home Economics, vol. 47, 1955

“Continental Can Co. v.Anchor Hocking Glass Corp.” – United States District Court, N.D. Illinois, E.DAug 16, 1965

“Flip Your Lid” – Springville Journal (New York), June 16, 1955

Archived Reader Comments:

“My mother had an Eko “Lid Flipper” in her kitchen utensil drawer. Insert Lid Flipper key, turn slightly, hear satisfying pop, twist off jar lid. While we may have gotten spoiled with “New Quarter Twist” lids for more than half a century, today’s jars still sometimes need a little oomph to get them to release their vacuum seal. The Lid Flipper lives in my kitchen drawer nowadays, right under the can opener.” —Anita Holmes, 2019

“My father in law Mike Harsley worked for them off central for many years. Alas with merging, factory consolidations and price pressures, changes will happen. Sad ” —Scott Towler, 2019

” —Scott Towler, 2019

“Enjoyed reading the article. Brought back good memories of my grandfather, WP White.” —Pamela Ficarella, 2018

Looking for retirement pension worked for continental white cap for 10 years in Hayward ca. How do I apply for my pension.

My mother, Lorraine Lawler, and uncle, Joseph Kurzer, worked at White Cap in the 1950s. As others have commented, I enjoyed the yearly picnics. My mother took the bus to work for many years (we lived in the Belmont and Narragansett neighborhood then). Later, a co-worker drove her. Later still, she finally learned to drive, bought a car, and drove her 1953 Mercury to work.

My dad worked there until the company closed. I used to love going to the company picnic’s.

My dad Dick Richard Kosinski was a machinist at white cap for 45 years. He passed at 90 years old on Nov 1 2024. Posted by his son Alan Kosinski

My grandfather, Karl E. Swangren, patented some tooling for lug cap manufacture and designed the equipment for plastisol pouring, as well as machinery for lug, screw, and baby-food caps.

This article brought back memories of my grandmother. She proudly worked in the White Cap factory for 50 years. The entire family attended the White Cap Company picnic held at Cedar Lake every year without fail. When she retired, she was given a diamond ring, one of her most prized possessions. I never realized that she must have been one of the very first white Cap employees!

Our Company Has A Capping Machine with a Metal Tag White Cap Inc. Member Of Continental Can In Chicago Ill.

I Need A Machine Manuel Model Number VGLJG

Thank You

Marlene Halvosa

My father was a food scientist at White Cap company. He check the lids to make sure there was no bacteria under the lids.

Did Robert White 1923-2005 have any children?

I have a white cap 50th anniversary metal tray. Is there any value in this?

Why does the lid flipper have holes on the ends?

My grandfather was George White and I have great memories as a little kid of going to the factory and getting different jar tops coming off the conveyer belt. Today, two of my brothers and I went to the factory and looked around though it is fenced off for now.