Museum Artifact: Marvel 60 Hole Punch, c. 1940s

Made By: Wilson Jones Company, 3300 W. Franklin Blvd., Chicago, IL [Humboldt Park]

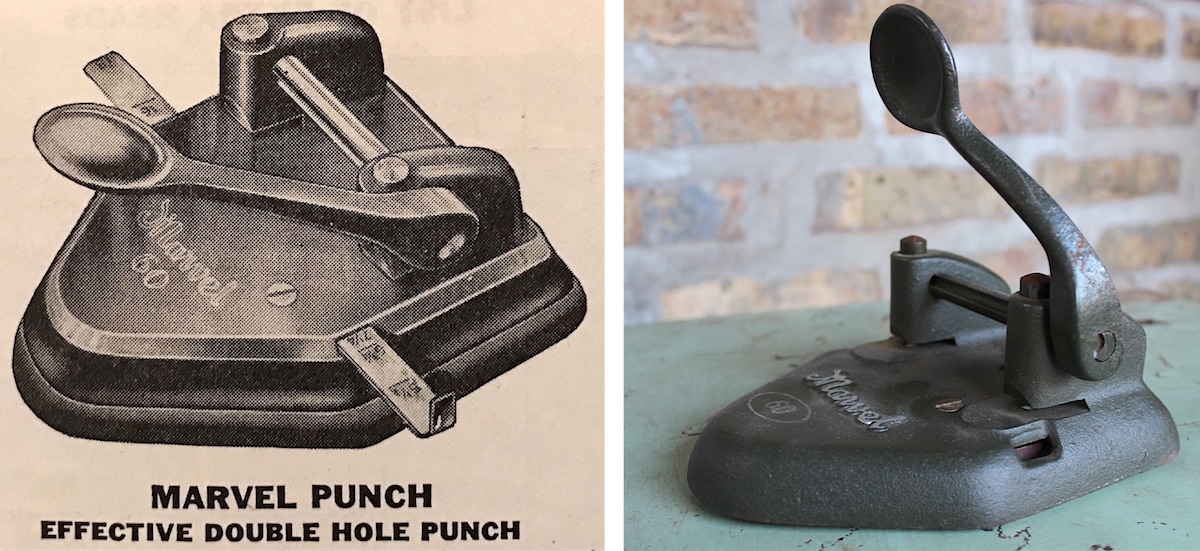

Long before any Marvel superhero ever punched a villain, the mighty Marvel Hole Punch was already dispensing its own brand of justice on unsuspecting sheets of binder paper. This lever-operated “paper perforator” was originally designed by Alexander and Chesley Dom of the Samuel C. Tatum Company in Cincinnati, making its debut around 1912. Chicago’s Wilson-Jones Company acquired the patent in the late 1920s and carried on manufacturing both the “Marvel” and “Hummer” lines—with only very minor design tweaks—through the end of the century. The Marvel No. 60 in our museum collection, which punches a pair of standard 1/4″ diameter holes, is likely a pre-war model, made at Wilson-Jones’s Humboldt Park factory in the late ’30s or early ’40s.

“The Marvel Punch has a solid iron base and is finished in olive green with the trimmings nicely nickel-plated,” read the product description in the company’s Catalog No. 139 (1939). “Hand lever made of malleable steel and always in upright position, ready for next punching operation. Equipped with detachable green moulded rubber base which also provides container for punchings. Side gauge adjustable to any desired margin. Maximum distance from center of hole to the binding edge of sheet 1/2 inch.”

“The Marvel Punch has a solid iron base and is finished in olive green with the trimmings nicely nickel-plated,” read the product description in the company’s Catalog No. 139 (1939). “Hand lever made of malleable steel and always in upright position, ready for next punching operation. Equipped with detachable green moulded rubber base which also provides container for punchings. Side gauge adjustable to any desired margin. Maximum distance from center of hole to the binding edge of sheet 1/2 inch.”

The price tag was usually about $2 before the war, which equates to a little under $40 after inflation. We got ours a few years ago for significantly less than that, as demand for heavy metal two-hole punches just ain’t what it used to be.

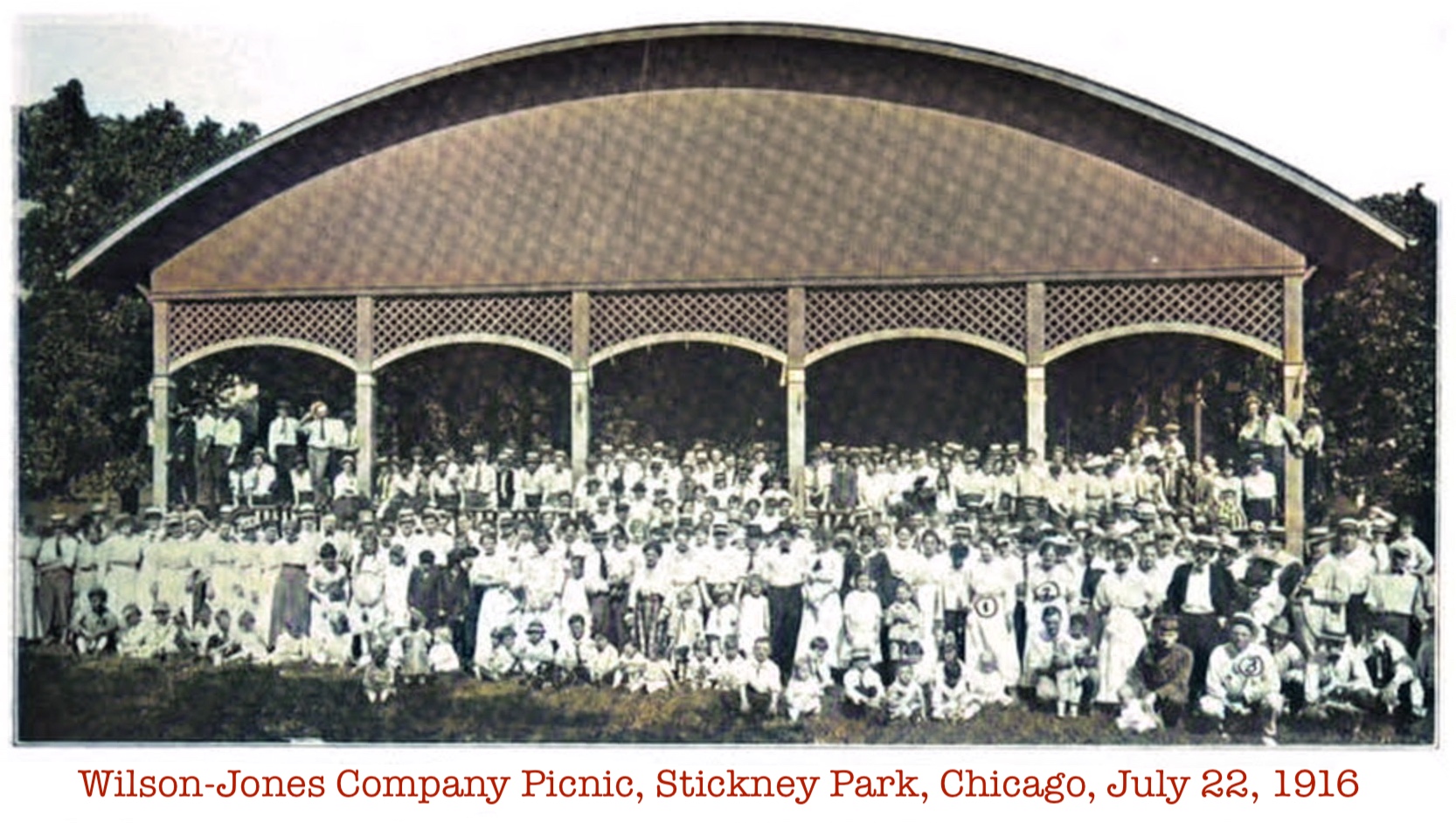

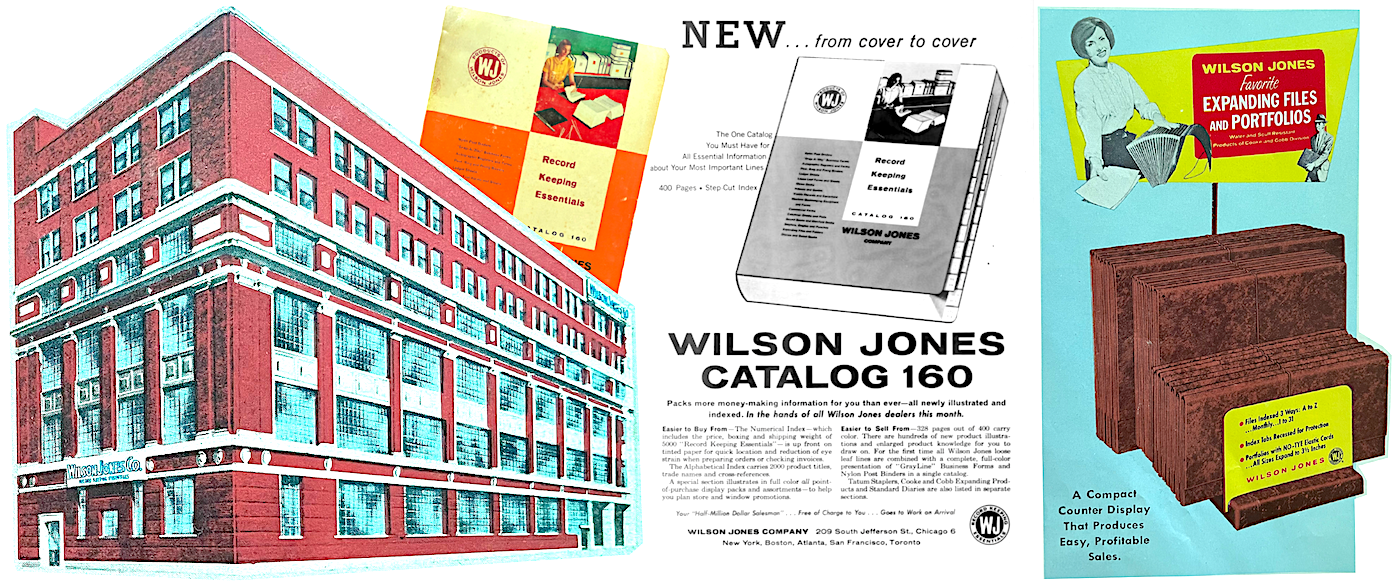

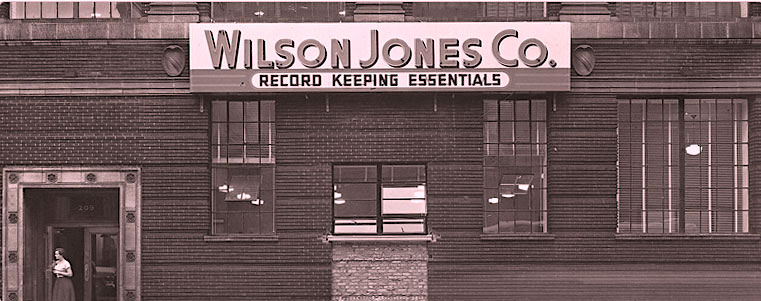

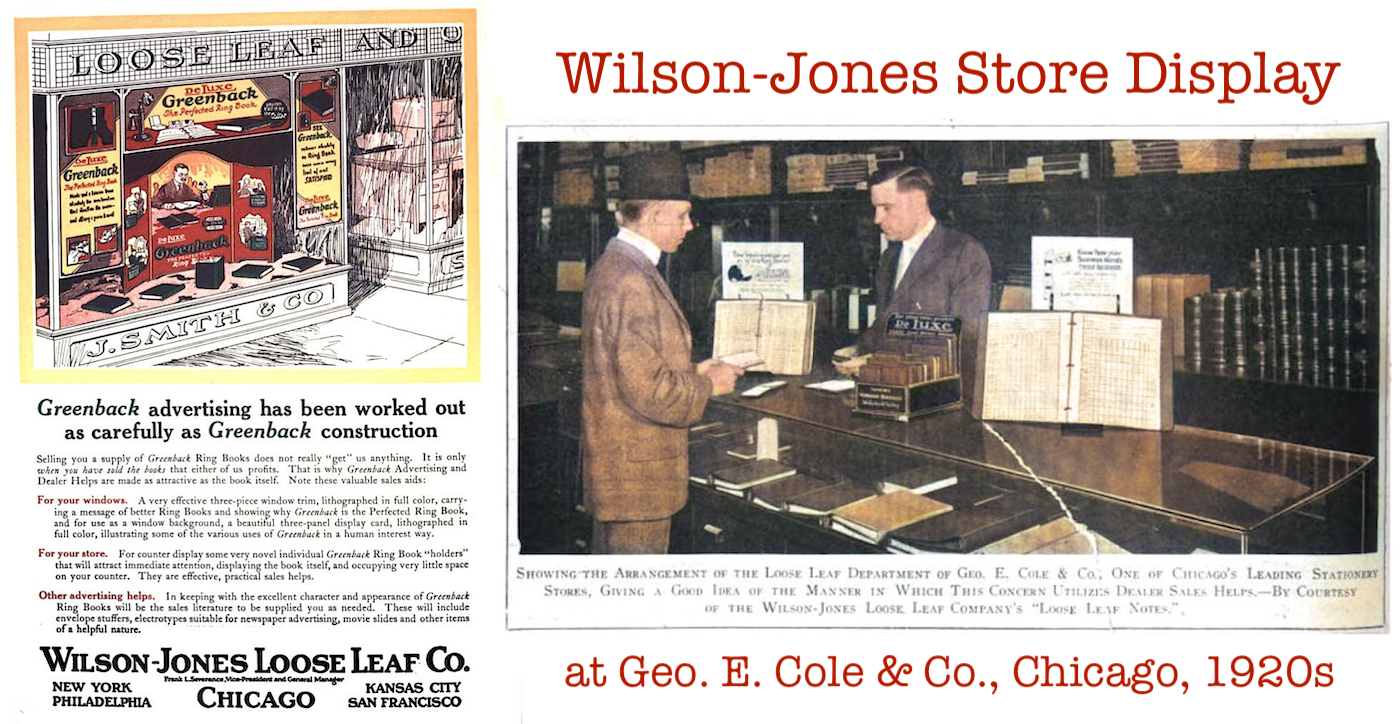

Because of their robust construction, Marvel punches are probably the most common Wilson-Jones “artifacts” you’re still likely to encounter from the company’s golden age, when they produced a wide range of stationery goods and “record keeping essentials” for a highly organized clientele. The sprawling factory at the corner of Franklin Boulevard and Spaulding Avenue, which employed upwards of 1,000 men and women at its mid-century peak, might have also occupied the finest smelling industrial block in the city. From the 1920s through the ‘50s, an employee of the Wilson Jones Company could spend his or her shift enjoying the scent of fresh cut paper products and leather book bindings. Then, walking out the front door at day’s end, they’d be greeted by a wafting cloud of confectionery goodness emanating from the Bunte Brothers candy factory directly across the street. That’s manufacturing at its most aromatic; factories of the finest olfactory standard.

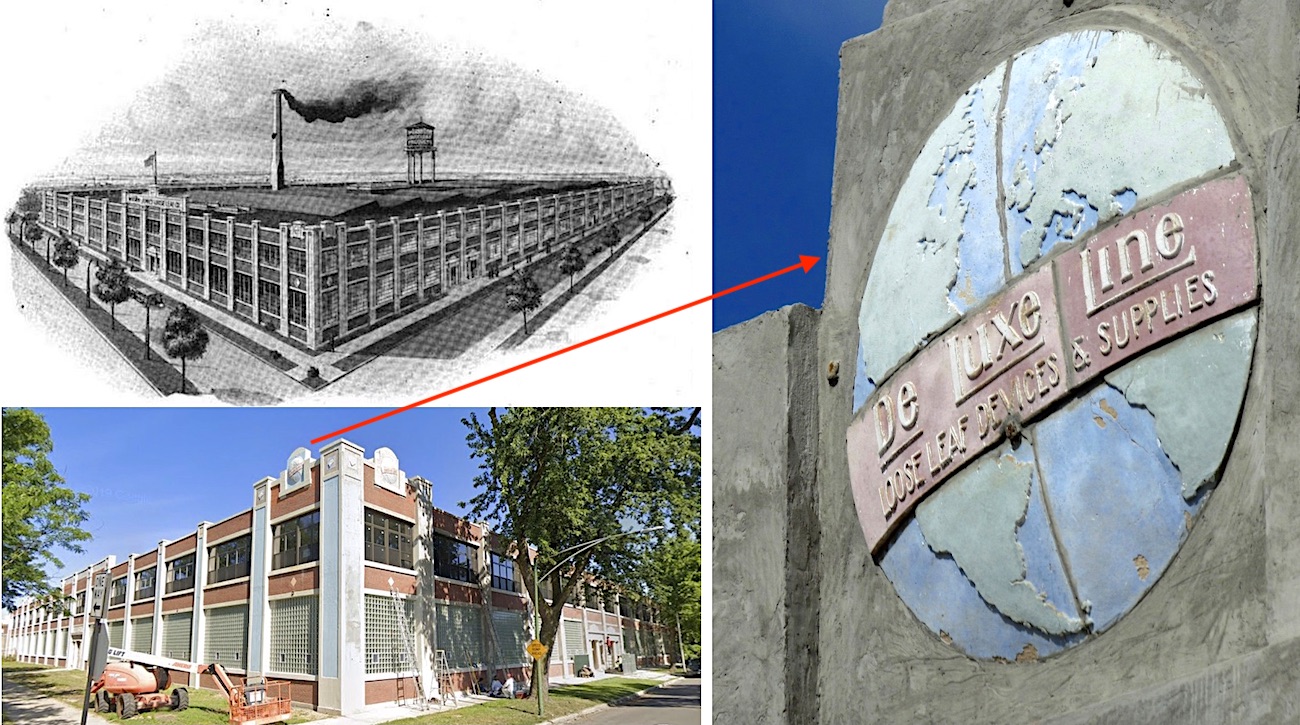

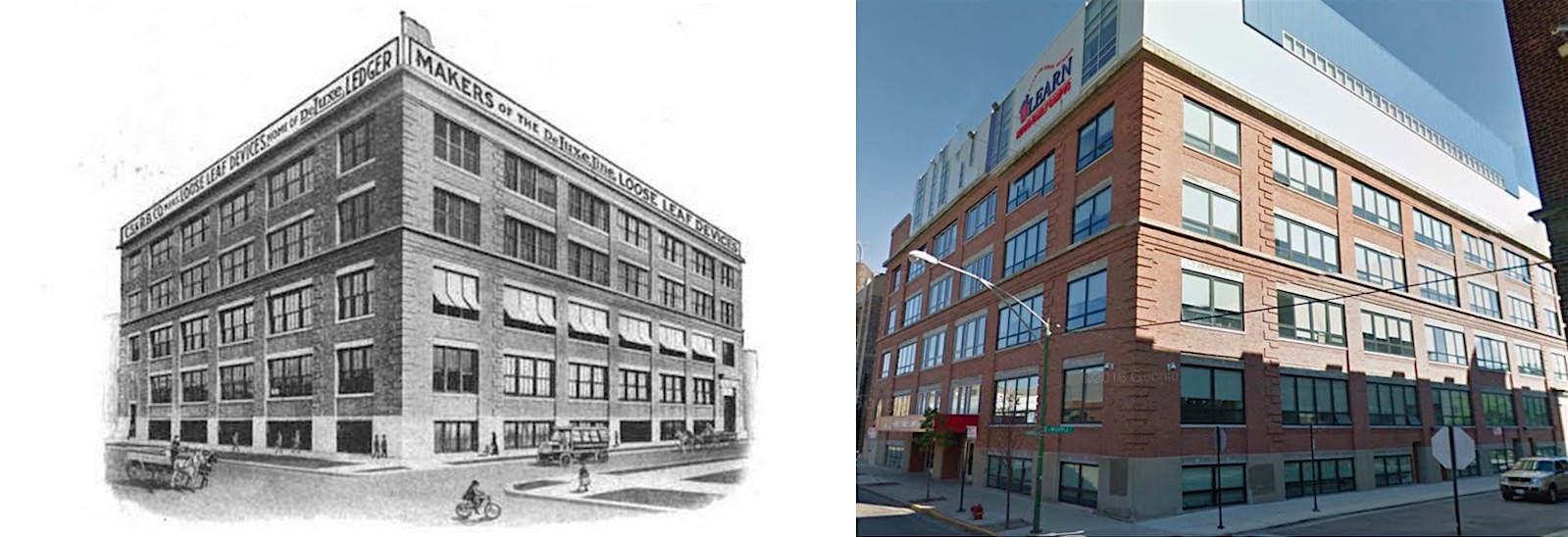

[Top Left: Wilson Jones building at 3300 W. Franklin Blvd, 1920s. Bottom Left: The same building in 2020, newly rescued from the wrecking ball and renovated. Right: Closer look at the ornamental globe atop the building, which had been painted over and hidden until the recent reclamation project. The globe, which dates back to the building’s construction in 1920, reads “De Luxe Line: Loose Leaf Devices & Supplies”]

Incidentally, the former Wilson Jones building was eventually abandoned, fell into terrible disrepair, and then—in just the past few years—was unexpectedly saved and fully renovated! A rare happy ending for a Made In Chicago storyline.

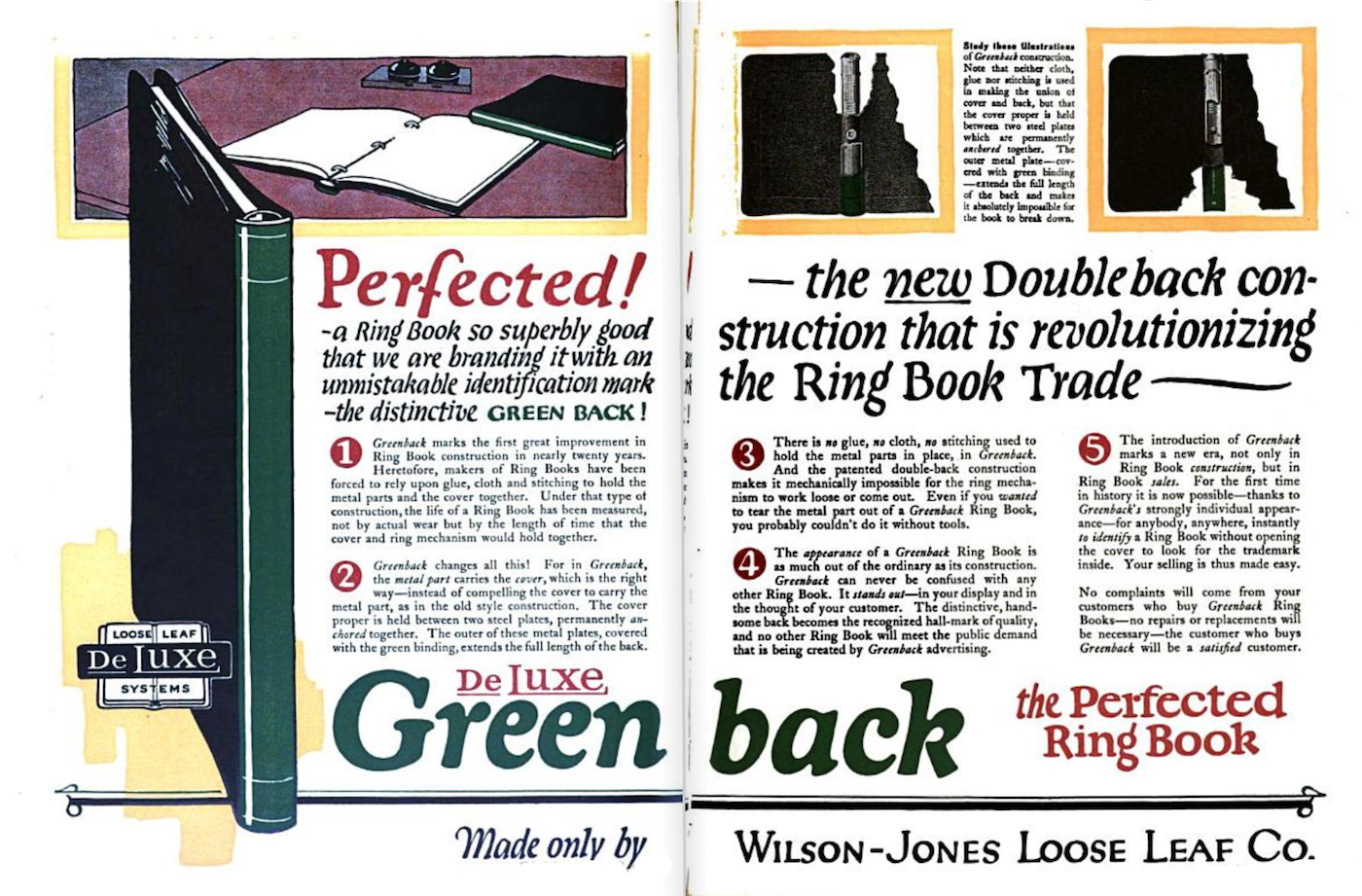

The Wilson-Jones Company has managed to survive, too, albeit as a subsidiary of the massive office supply conglomerate ACCO Brands (Swingline, Mead, Trapper Keeper, among others). Close to 130 years after its founding, the W-J brand name is still associated with loose leaf accessories like folders, ledgers, sheet protectors, and three-ring binders. If you believe ACCO Brands’ own corporate website, in fact, Wilson-Jones was actually the company that “invented the three-ring binder“—a crowning achievement that forever changed the contents of the world’s filing cabinets and backpacks. Unfortunately, that particular claim to fame—like many other details of the company’s early history—seems rooted more in perpetuated myth than concrete fact. To remedy this, we’ve dug through a few binders of our own in order to piece together a more complete, if unofficial, History of the Wilson-Jones Co.

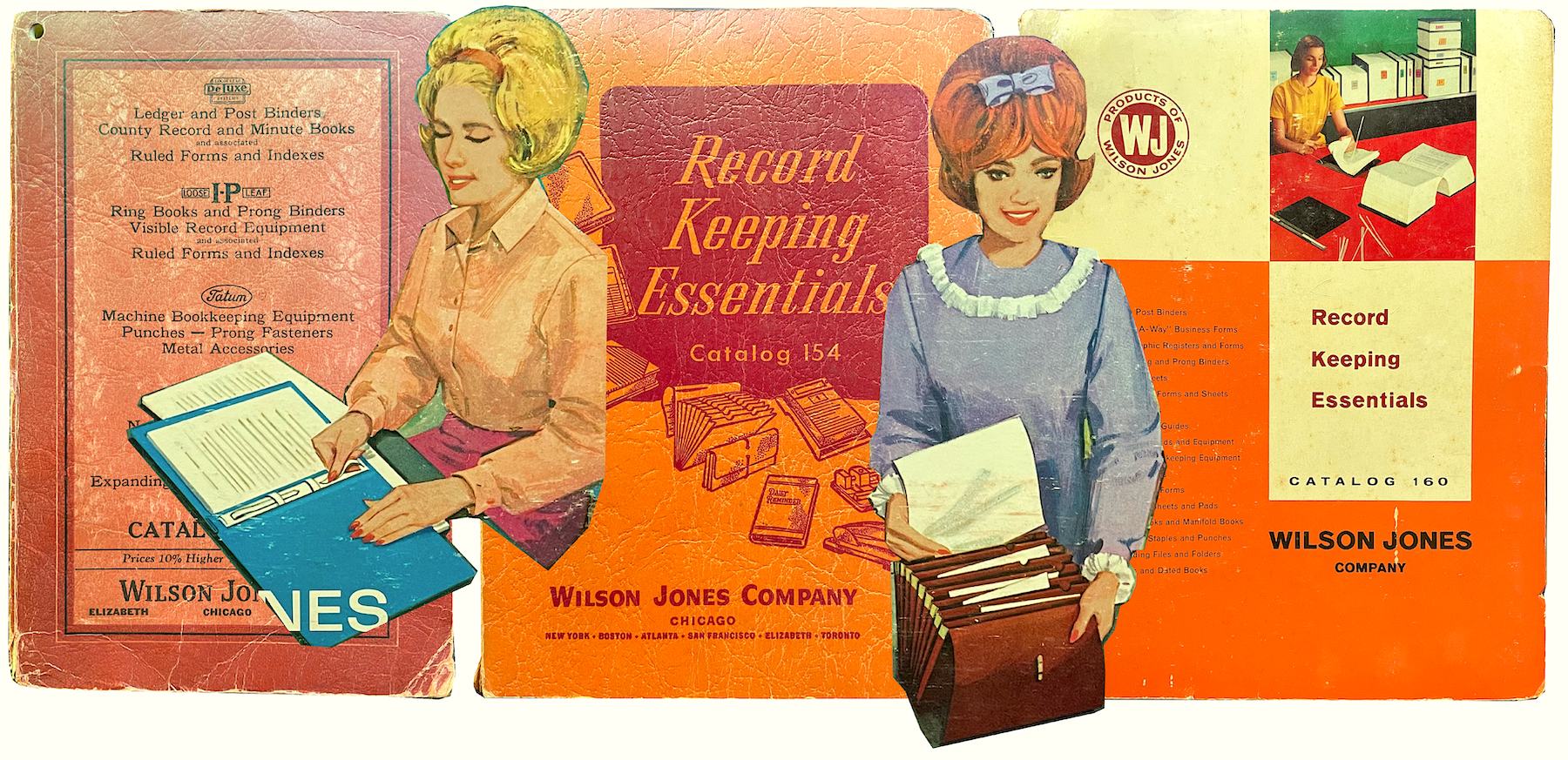

[Selection of Wilson-Jones sales catalogs donated by Patricia Thornbrough of Richardson, Texas. Patricia’s husband Clarence Thornbrough utilized these books across a 30 year career as an office supply salesman.]

History of the Wilson-Jones Co., Part I: Three Ring Circus

The original incarnation of Wilson-Jones was known as the Chicago Shipping and Receipt Book Company (or C.S. & R.B. Co.), and was supposedly started by a Clark Street jeweler during the World’s Fair summer of 1893. By some accounts, that jeweler was Ralph B. Wilson himself, the boisterous businessman who would run the company well into the 20th century. Other versions of the story, however, refer to “the jeweler” as a wholly separate, suspiciously anonymous individual—just basically a guy running a side business selling aluminum paper holders. Depending on which origin point you prefer, then, Ralph Wilson either “built” the business from scratch or “took it over” closer to the turn of the century. Even publications during Wilson’s own lifetime seem unsure of which version is true.

It probably didn’t help matters that Ralph Wilson (b. 1870 in Paolo, KS) was something of a notorious showman, prone to exaggeration and theatricality during his two decades as company president. These were traits he’d picked up in his youth, when he spent several years touring with the Ringling Brothers caravan show, serving as the big top’s “advance man,” or glorified publicist. The weird leap from the three-ring circus to three-ring binders, apparently, was merely a logical next step.

“Many men spend a lifetime in the circus and get nothing out of it,” Office Appliances magazine reported in 1920, “but the observing man is impressed, among other things, with the one big fact that, in the circus world, nothing that can arise in the necessary experience of the shows is going to be impossible of accomplishment. Mr. Wilson is observing. He learned the circus lesson of energy and practical determination to surmount obstacles, and in the conduct of the business he applies these lessons, doing what he sets out to do.”

No offense to the good people at Office Appliances, but it’s probably just as likely that Ralph Wilson simply enjoyed making flyers for the circus and decided to pursue a career with more paper crafts and fewer clowns. No deeper wisdom or inspirational acrobatics required. Either way, the result is the same. Wilson went to work building the Chicago Shipping and Receipt Book Company into a major player in the stationery biz.

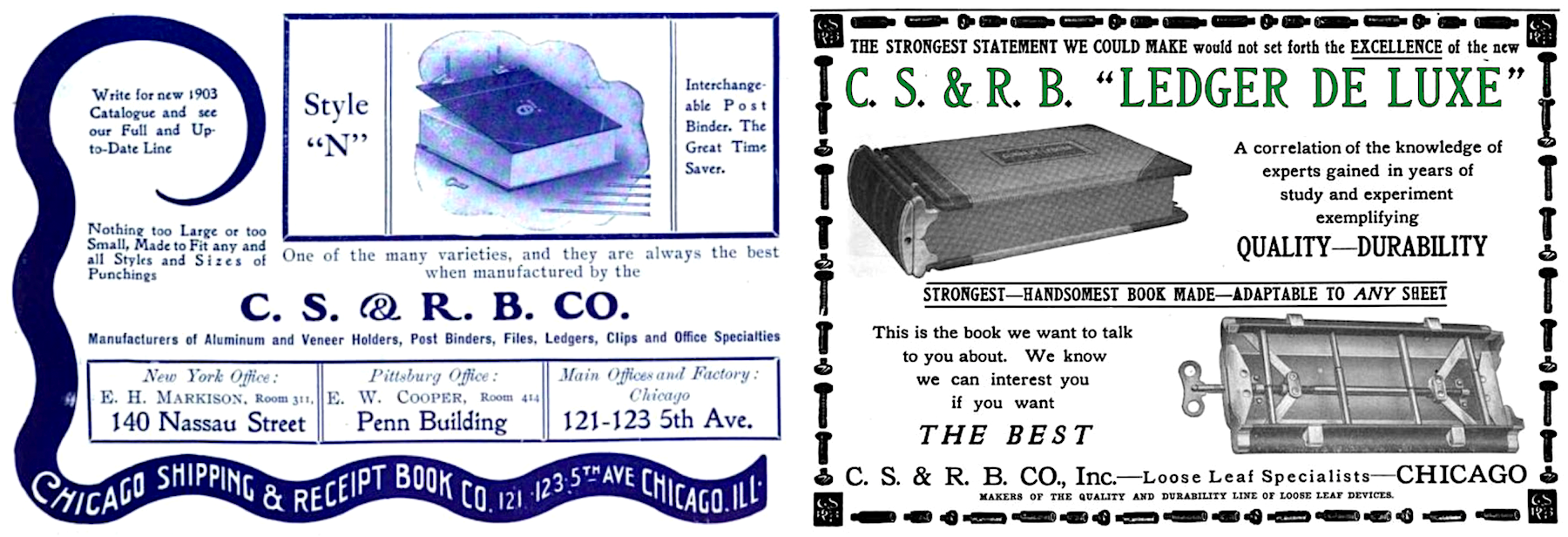

[Early advertisements for Wilson-Jones, then known as the Chicago Shipping & Receipt Book Company, or C.S. & R.B. Co., Inc. The ad on the left is from 1903, while the “DeLuxe” ad on the right dates from 1909]

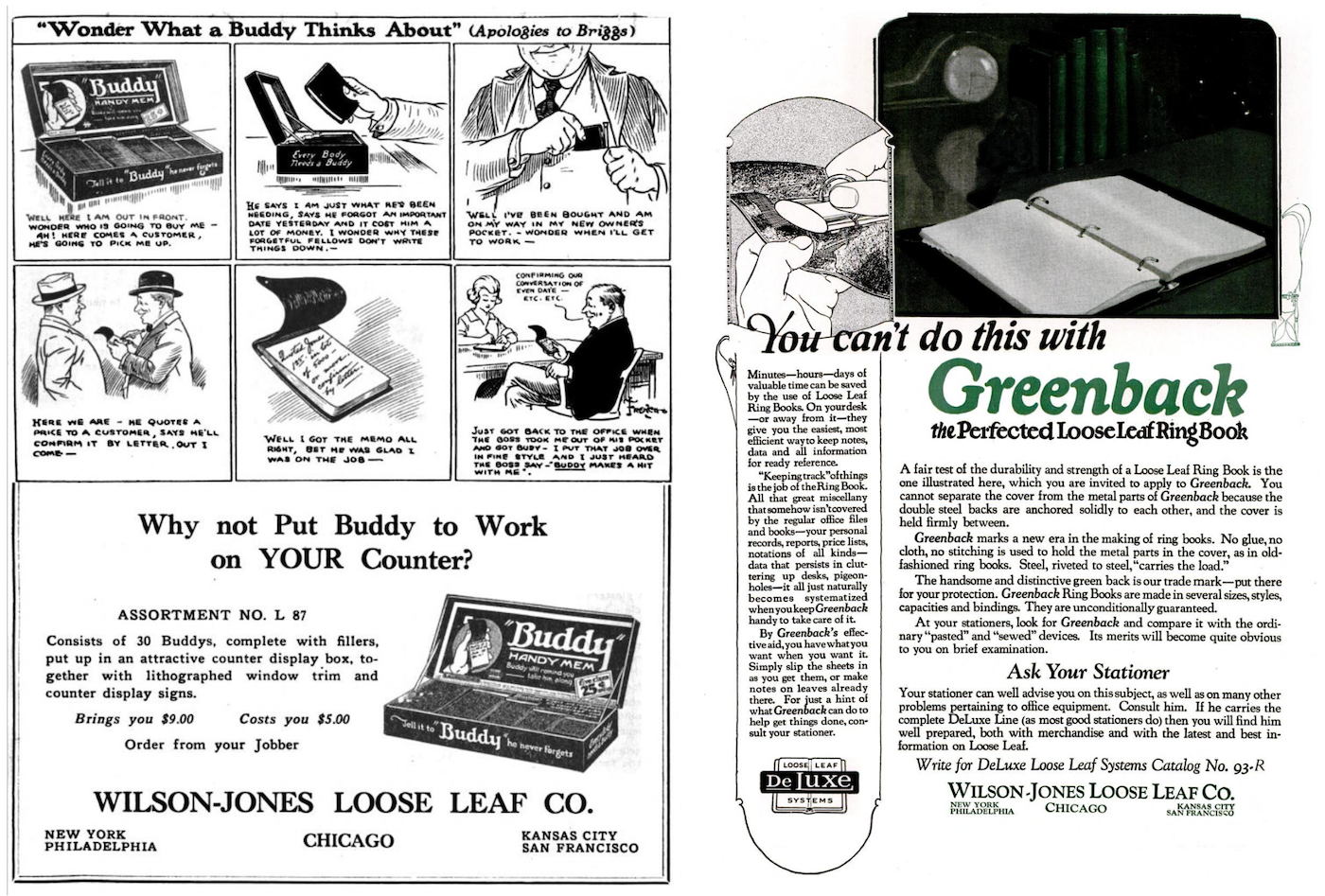

In 1900, still just 29 years of age, Wilson employed a small troupe of four men in a one-room office at 20 S. Clark Street. Within a few years, after introducing loose leaf ledgers and the DeLuxe brand of sectional post transfer binders to its arsenal, the company outgrew three subsequent factory spaces (Wells & Madison, Kinzie & State, Kinzie & Armour) and ballooned to a team of 150 workers.

It was around this time that C.S. & R.B.C. did, indeed, start manufacturing a style of three-ring binder, but the product was really more of an inevitability than a revolutionary concept by that point.

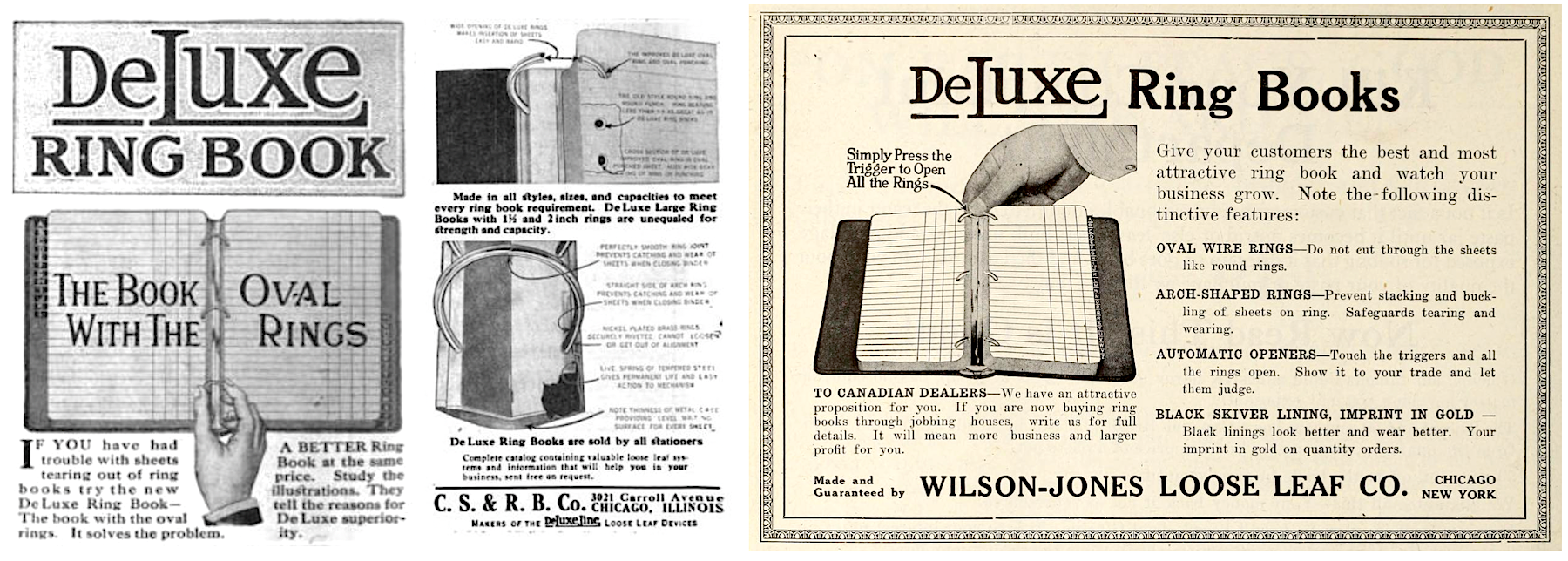

[Wilson-Jones “DeLuxe Ring Books” advertisements from 1912 (left) and 1915]

II. Ties That Bind

As far back as 1859, a 23 year-old named Henry T. Sisson (a future Civil War colonel and Lt. Governor of Rhode Island) filed a patent for a “novel apparatus which may be applied in the back of a portfolio or attached to a suitable handle for the purpose of holding and securing music sheets, pamphlets or papers of any kind.” By the 1880s, German inventor Friedrich Soennecken had invented a more advanced breed of ring-style binder, along with a new device to go with it; a hole punch. In the late 1890s, Ralph B. Wilson’s local rival, the Chicago Binder & File Co., was already selling a series of ringed binders, too.

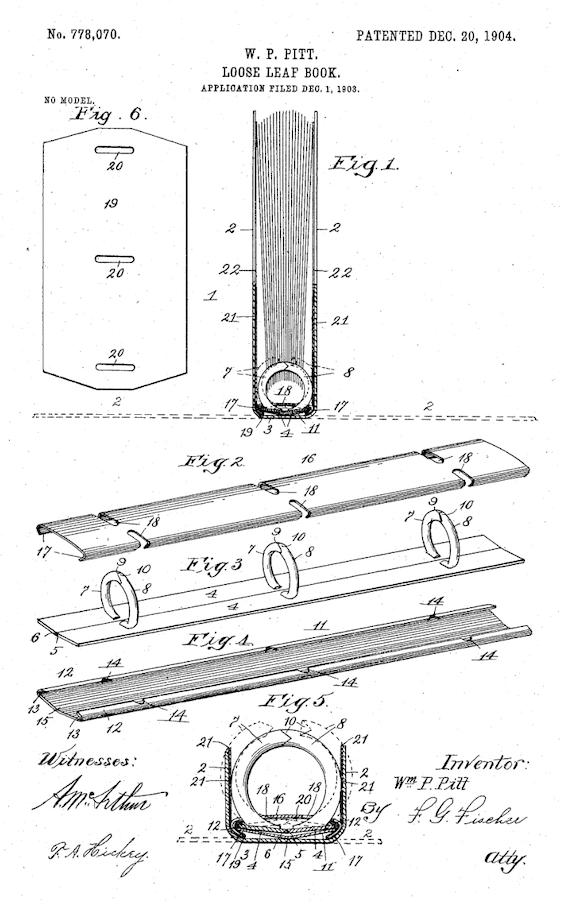

Finally, in 1904, the more recognizable modern concept for the three-ring binder was patented in the United States . . . by the Irving-Pitt Manufacturing Company of Kansas City. Ralph Wilson had nothing to do with that invention, but he would start getting the credit for it years later, after Wilson-Jones acquired Irving-Pitt in the late 1920s and started retconning the history of the latter firm’s most iconic product.

Even if some of Wilson’s supposed innovations might have been rooted in myth, there was no denying his very real success as a businessman. The thriving Chicago Shipping and Receipt Book Company needed less than a decade to become one of the largest stationery brands in the country, and Wilson was soon in a position to start gobbling up some of his key competitors, including the Public Record Index Company of Chicago and the Hamacher-Hawkins Company of Kansas City (another early producer of ring books). The products from every acquired firm were then seamlessly incorporated into the production lines of C.S. & R.B.

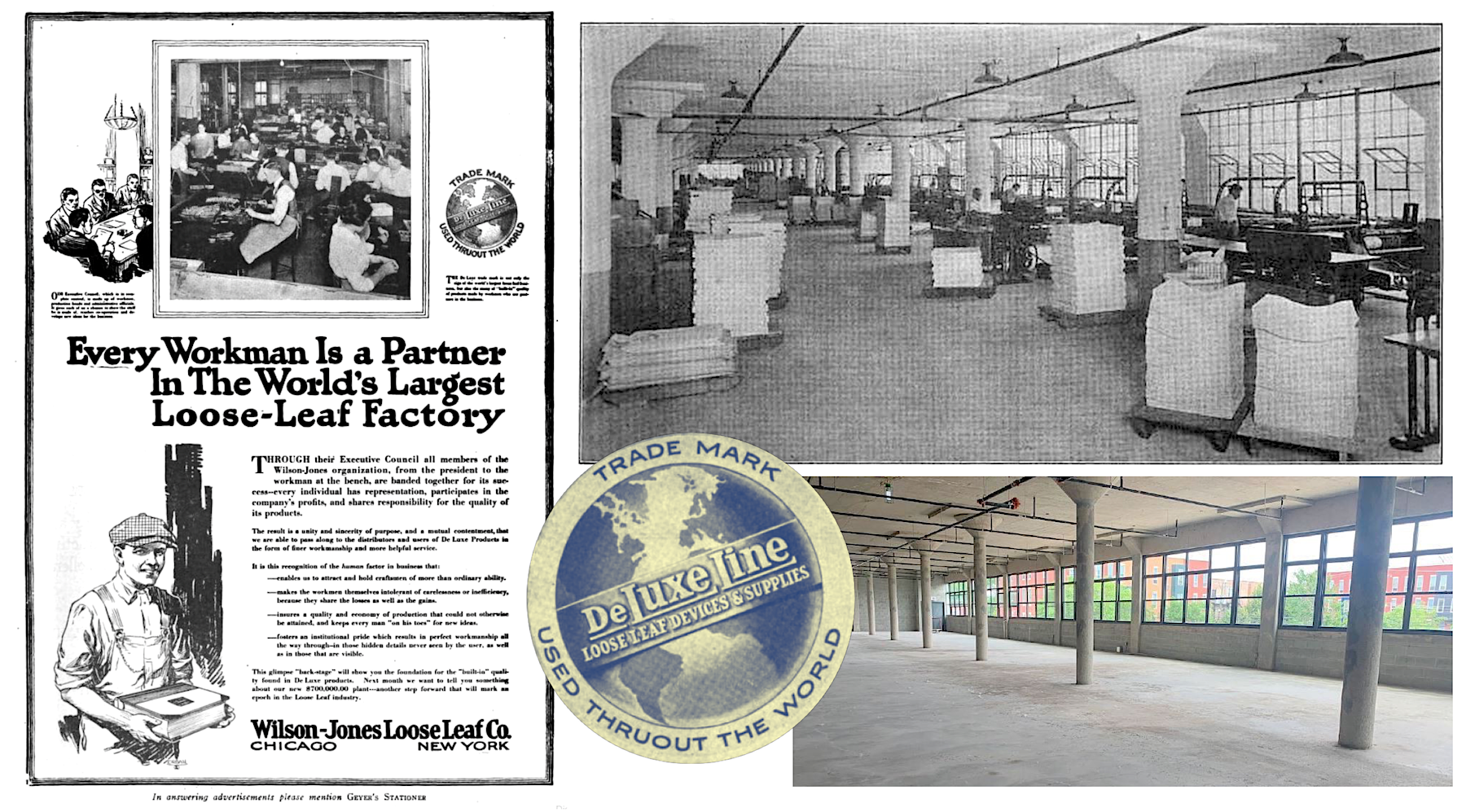

“Record making—building up a team interest in the game—that’s the basis of my method of cutting down losses in the shop,” Wilson once said. “Each department holds a definite position in relation to the making of the product. Each takes a pride in the work of his section. And when he sees in black and white the results of his efforts to keep up department efficiency, that score helps hold his interest.”

Interestingly, Wilson didn’t love the “team” concept quite as much when it came to the idea of labor unions. He routinely clashed with organized book binders and other tradesmen, leading to a series of strikes and lockouts between 1907 and 1910. Even so, during that same period, the Chicago Shipping and Receipt Book Company continued its rapid growth, graduating to yet another new factory space at 3021 W. Carroll Avenue in East Garfield Park; a building was promptly expanded from three to five stories (93,000 square feet) in 1913.

[The old Wilson-Jones plant at 3021 W. Carroll Ave., 1913 vs 2017]

[The old Wilson-Jones plant at 3021 W. Carroll Ave., 1913 vs 2017]

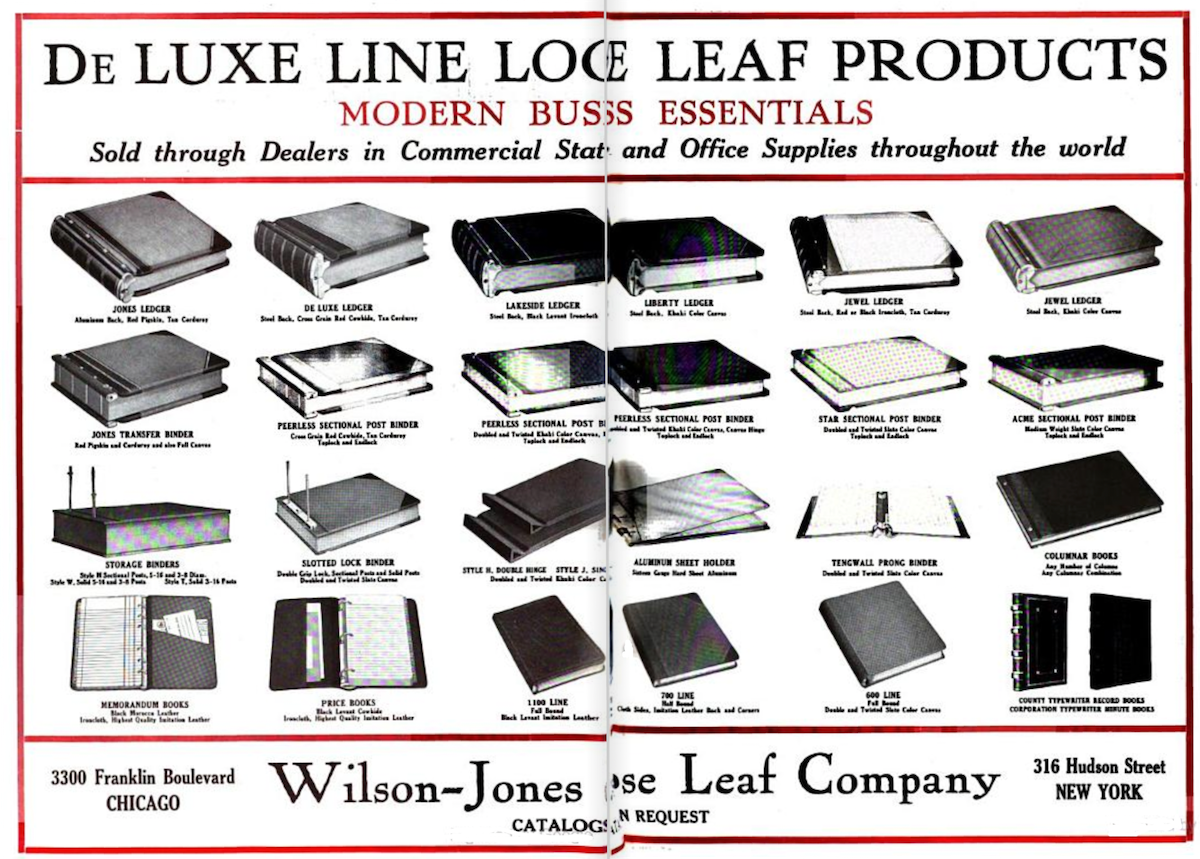

“The DeLuxe line of Loose Leaf Devices have earned a reputation throughout the world for quality and are extensively sold in Canada, Europe, Australia, South Africa, South America, as well as in all parts of the United States,” Geyer’s Stationer reported that year. “. . . In the factory there is a complete die and tool making plant, an assembling department, a plating department, a buffing department, bindery, ruling, printing, and index departments.”

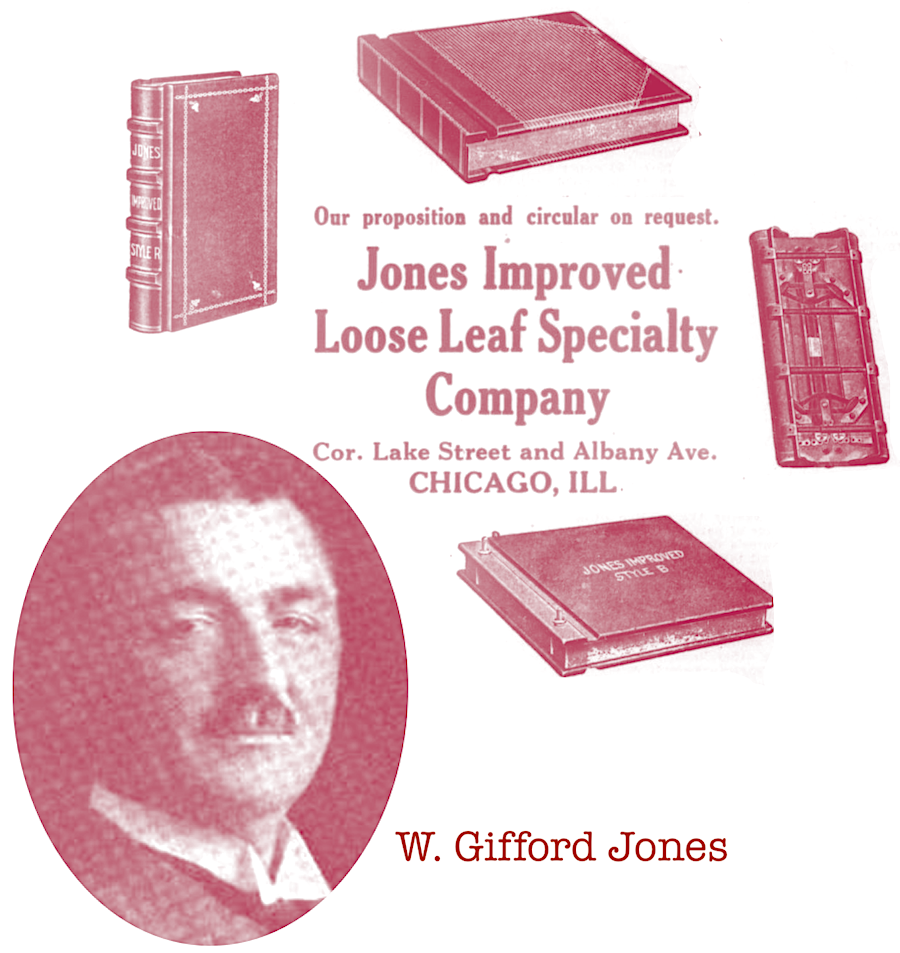

1913 was also the year that Ralph Wilson made the biggest acquisition of his career, agreeing to buy another leading Chicago competitor, the Jones Improved Loose Leaf Specialty Company.

The Jones firm, which had its own factory over at 3051 W. Lake Street, traced its roots back to 1899—when Harvey P. Jones and his sons W. Gifford Jones and Harry S. Jones started the Jones Perpetual Loose Leaf Co. The trio later sold that business and reorganized as the Improved version in 1902, but the patriarch Harvey Jones died just days later, leaving his sons to run the operation. They did so admirably for 11 years, but couldn’t pass up the benefits of joining Ralph Wilson’s merry band of binder makers.

The Jones firm, which had its own factory over at 3051 W. Lake Street, traced its roots back to 1899—when Harvey P. Jones and his sons W. Gifford Jones and Harry S. Jones started the Jones Perpetual Loose Leaf Co. The trio later sold that business and reorganized as the Improved version in 1902, but the patriarch Harvey Jones died just days later, leaving his sons to run the operation. They did so admirably for 11 years, but couldn’t pass up the benefits of joining Ralph Wilson’s merry band of binder makers.

The American Stationer described the deal as “the consummation of one of the most important deals ever effected in the history of Chicago’s stationery interests.” Of special note was the fact that the two companies would be “merged into one concern under the firm name of the Wilson-Jones Loose Leaf Company. . . . Ralph B. Wilson is to be president and treasurer of the new company, W. Gifford Jones will be vice president, and Harry S. Jones will fill the position of general superintendent of production.”

And there you have it, the mighty Wilson-Jones union was forged, set to carry on—at least as a brand name—for the next century to come. The irony, perhaps, is that the actual corporate co-existence of Wilson and the Joneses was practically over before it started.

III. Shredded Alliances

Less than a year after reporting on the partnership that established the Wilson-Jones Company, American Stationer informed its readers that “W. Gifford Jones and Harry S. Jones have withdrawn from the Wilson-Jones Loose Leaf Company and are planning to go into business for themselves again.”

Was that the plan all along? Had the Joneses merely been stewarding their dad’s old company into the merger for six months with the full intention of exiting stage left? Or was it an unexpected detour fueled by, say, an inability to work with their new ringmaster of a boss? We can only speculate, but whatever the reason, Wilson-Jones was thoroughly free of the Jones half of its identity by 1914. Afterwards, Ralph Wilson could have elected to revert to the company’s old name or conjure up a new one, but the business cards were long since printed. “Wilson-Jones” it would remain.

Was that the plan all along? Had the Joneses merely been stewarding their dad’s old company into the merger for six months with the full intention of exiting stage left? Or was it an unexpected detour fueled by, say, an inability to work with their new ringmaster of a boss? We can only speculate, but whatever the reason, Wilson-Jones was thoroughly free of the Jones half of its identity by 1914. Afterwards, Ralph Wilson could have elected to revert to the company’s old name or conjure up a new one, but the business cards were long since printed. “Wilson-Jones” it would remain.

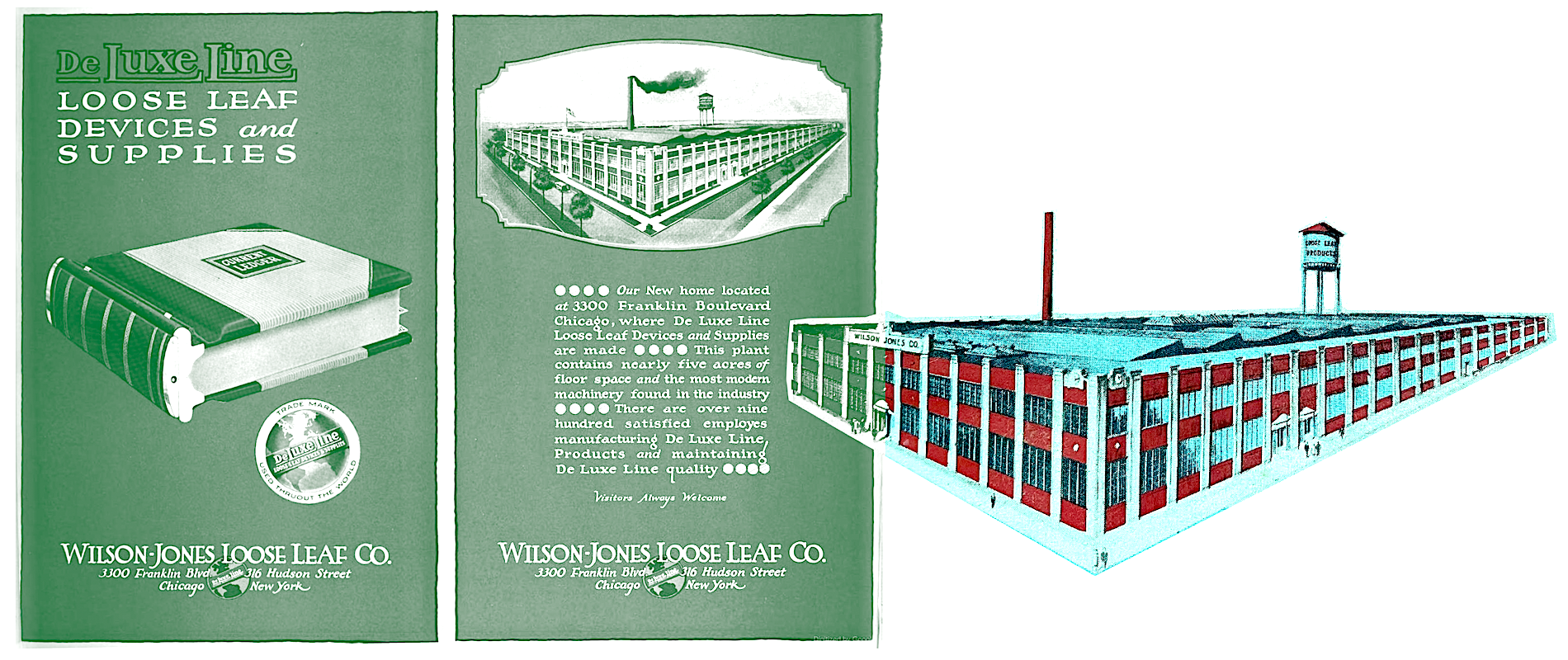

In 1920, the Wilson-Jones Company migrated to its grandest (and ultimately final) Chicago headquarters, at 3300 W. Franklin Boulevard; a 4.5 acre facility equipped with “many restrooms, an emergency hospital, restaurant, and large office, all finished with terrazza floors, circulating ice water system, filtered air ventilating system, and the most modern plumbing available,” according to a 1920 company ad.

“The new factory, built under Mr. Wilson’s direction and from his ideas, is really a wonderful plant,” Office Appliances reported after a private tour. “[It’s] a monument to his enterprise, energy and forethought.”

From Wilson’s perspective, it was also a parting gift to the company he’d devoted more than 20 years of his life to. A few months shy of his 50th birthday, the ever-adventurous executive decided to step back from the day-to-day operations of the business and hand it off to a new generation.

[The Wilson-Jones factory at 3300 W. Franklin Blvd. in Humboldt Park, opened in 1920 with 1,000 employees]

“I take this opportunity to thank the trade for the generous patronage which has made possible the steady growth of the business,” Wilson wrote in a press release upon his exit in 1920.

“In the history of the Wilson-Jones Loose Leaf Company,” Office Appliances added, “as in that of other businesses which have attained conspicuous success, the business grew with the man and the man expanded his mental horizon as the business grew.”

Wilson rode off into the sunset, off to spend his well-earned fortune with his family in southern California. His eventual successor, meanwhile—a young bank executive named Benjamin Kulp—would remain a dominant but polarizing figure at the company for the next 40 years.

[Left: 1920 advertisement. Right: Then and Now view of the interior of the Wilson-Jones factory at 3300 Franklin Blvd., 1920s vs. 2020s]

IV. Kulpability

Ben Kulp had certainly paid his dues. Immigrating from Lithuania as a small child, he spent most of his youth in a Jewish orphanage in Cleveland, Ohio, as his mother lacked the resources to care for him during the economic depression of the era. In subsequent records, both his date-of-birth (sometime between 1886 and 1890) and place of birth (he listed Lithuania, Ohio, and Iowa, depending on the census year) remained unclear even to Kulp himself. According to a message sent to the museum by his own great-niece, however, Kulp never ran from his past. He helped financially support his mother, who lived to be 100 years old, and in 1925, he made a substantial donation to the Cleveland orphanage in which he’d grown up.

“I have done well and wanted to pay for what the institution did for me,” Kulp told the American Stationer. “Recently I wrote and asked them what it cost them in the years 1895 to 1904 to keep a boy there. They estimated it at $150 a year. So I sent them a check for $1,350.”

While still a teenager, a determined Benjamin Kulp headed for Chicago, systematically working his way up from errand boy to bank manager to Vice President of the Madison and Kedzie State Bank. He was the classic self-made man—ambitious and uncompromising, and generally admired for it early on.

“The ‘I Will’ spirit is responsible for what Chicago is today,” The Advocate (a Jewish journal) reported in 1921, “but never was that spirit better displayed than by one of our best known citizens, Mr. Benjamin Kulp.”

Presumably, Ralph Wilson and the other board members of Wilson-Jones recognized this same spirit in Kulp, elevating him the role of company president by 1922, when he was still in his early 30s. The company, to his credit, remained the leader of its industry, acquiring two more key rivals in the 1920s (the aforementioned Samuel C. Tatum Co. and Irving-Pitt MFG Co.) and bucking trends in the 1930s by continuing to bank profits. A second major factory was opened in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and the W-J catalog was continuously expanded to cover any possible product worthy of being a “modern business essential.”

Ben Kulp was personally benefitting from the company’s good fortunes, as well, perhaps as much as any of his industrial compatriots of the period.

In 1937, when the U.S. Securities Commission released a list of corporation salaries to the public, Kulp was the highest individual earner on the entire list. Admittedly, his reported salary of $65,090 doesn’t sound all that impressive, and even after inflation, it’s only a little over $1 million. But that’s probably more of a statement on just how out of whack executive payouts have become in the ensuing decades.

Kulp was named Chairman of Wilson-Jones in 1940, but all was not smooth sailing by this point. Many of the company’s employees, including 850 men and women in Chicago and another 350 in New Jersey, were now in an ongoing conflict with their boss, citing his unfair negotiating tactics, including a supposed refusal to recognize the new United Loose Leaf and Blank Book Workers’ union as the workers’ bargaining agency.

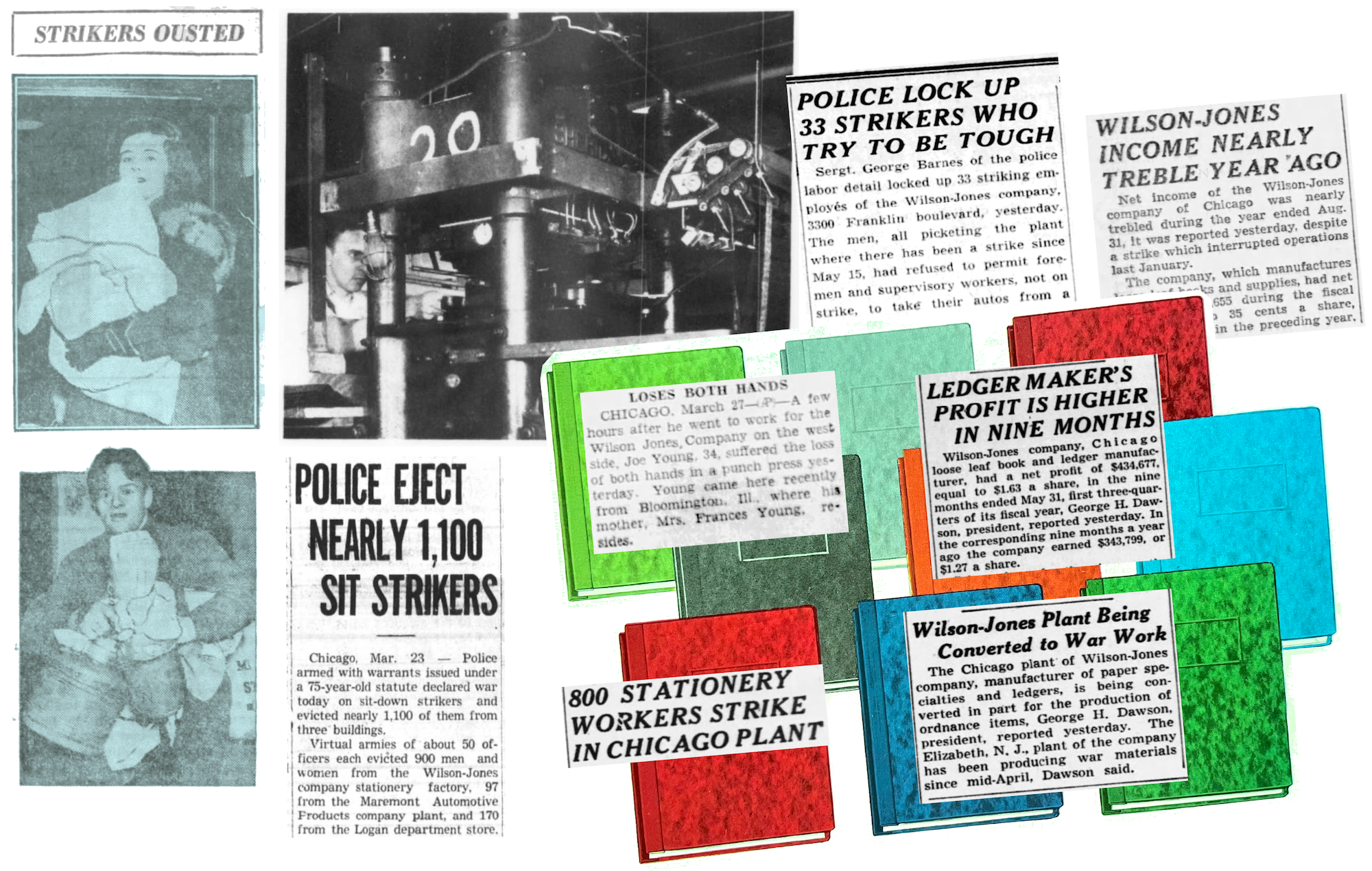

During an intended overnight sit-in strike at the Chicago plant in 1937, the police department unearthed a 75 year-old law that enabled them to force striking workers (many of them women) to leave the building under threat of arrest; many were photographed exiting the factory with blankets and pillows they’d brought with them for the sit-in. More strikes followed over the ensuing years, including a large wartime walkout in 1942 and another in 1945, led by the United Paper Workers Union. Kulp, like Ralph Wilson decades earlier, wasn’t the biggest fan of organized labor. And during the ’30s and ’40s, the contrast between Wilson-Jones’ big profits and the consistent unrest among its employees was glaring.

[Left: Two Wilson-Jones workers are forced out of a planned sit-in strike at the Chicago factory in 1937. In the other photo, a Wilson-Jones worker uses a stamping and embossing machine at the plant in 1941. By 1942, most of the factory had been repurposed for defense contracting work.]

Either by his intention or simply by his nature, Kulp did have a tendency to ruffle feathers. Even when he tried to use his own growing wealth for good deeds, it seemed to bring trouble—like the time he presented the town of Hot Springs, Arkansas (his summer home) with a bronze statue of Abraham Lincoln, thus launching an angry wave of backlash from the townsfolk in the old Confederate stronghold. That was an innocent miscalculation perhaps. But as he got older, Kulp also got more hot-headed and combative with those who didn’t see things his way.

According to Douglas V. Austin’s 1965 book, Proxy Contests and Corporate Reform, “Benjamin Kulp, chairman of the board of Wilson Jones, was involved in frequent altercations with some members of the board, and several members resigned in protest over his behavior. The opposition alleged that Kulp had caused Wilson-Jones irreparable damage because of his dictatorial, spendthrift management of the firm. The opposition contended that Kulp retained control only because he forced the employed directors to be ‘yes men’—the employee-directors had no employment contracts and did not dare express themselves freely.”

Things really came to ahead in the 1950s, when Kulp was approaching retirement age but still clinging to his hold on the business. As Financial World magazine later reported, Wilson-Jones was still “a leader in the office supplies field, particularly in the looseleaf and blank book segment of the industry,” but while the firm had a “diversified line of some 6,000 items, the record of Wilson-Jones over the past decade has been anything but spectacular. In the 1950-59 period, sales increased 51% and per share earnings only 9%; and in the five years 1955-59, volume rose slightly but earnings fell 23%.”

Into this scenario came New York’s famous stapler company Swingline, Inc., which offered to purchase Wilson-Jones for a hefty sum. Kulp and his loyalists, however, refused to approve the deal, battling tooth and nail with the growing number of insurgent shareholders inside the new Wilson-Jones corporate offices at 209 S. Jefferson Street.

[Wilson-Jones offices at 209 S. Jefferson Street and images from company catalog No. 160, from 1960]

“It would seem that a sharp clash of personalities, rather than a simple difference of opinion over policy, must have led to this wide split between the company’s owners and its managers,” Austin wrote.

In the end, under increasing pressure, Kulp finally surrendered, announcing his retirement in October of 1959, which came hand-in-hand with the sale of the majority of Wilson-Jones shares to Swingline. By 1963, Swingline gained complete ownership of the company.

Soon enough, the Franklin Boulevard plant, like the Bunte Brothers factory before it, was left abandoned, although Wilson-Jones did maintain a Chicago factory under Swingline ownership, at 6150 W. Touhy Avenue in Niles. That building was still in use through the 1980s, but was finally closed and demolished in 1995. Swingline, by that point, had been purchased by American Brands, which moved most of the corporation’s manufacturing (despite what the name would suggest) to Mexico. Both Swingline and Wilson-Jones carry on under the ACCO Brands banner today.

[1916 advertisement for the Marvel Punch, originally made by the Samuel C. Tatum Co. in Cincinnati, OH]

Sources:

Geyer’s Stationer, Vol. 55 (1913)

The American Stationer, Vol. 74 (1913), Vol. 86 (1920)

Office Appliances; The Magazine of Office Equipment, Volume 32 (1920)

The Advocate: America’s Jewish Journal, Volume 61 (1921)

“Pays 22 Year Old Board Bill” – American Stationer, Dec 26, 1925

“Wilson Jones Reports Sharp Earnings Gain” – Chicago Tribune, March 16, 1936

“Strikers Ousted” – Chicago Tribune, March 23, 1937

“Wilson Jones in Forum” – Financial World, Feb 10, 1960

Proxy Contests and Corporate Reform, by Douglas V. Austin, 1965

Tools of Business, an Encyclopedia of Office Equipment and Labor Saving Devices, edited by Elmer Herny Beach

“Sons of Confederate Veterans Rebel at Idea of Planned Lincoln Exhibit” by Noel E. Oman in the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 5, 2003

Archived Reader Comments:

“My mother, Mildred Uhl worked at Wilson-Jones from 1946-1973. I do have some photos in a retirement book. Will plan a museum visit this spring. All places in that area are very familiar in my youth. Good luck in your venture.” —Marilyn Uhl, 2019

“The Marvel Hole Punch was born from the labor of Alexander and Chesley Dom in 1915. It was the original property of the Sam’l C. Tatum Company who sold thousands of them. In 1922 the Tatum Company sold their hole punch interest to a company called Delmar, who later sold it to the Wilson-Jones Company. Needless to say, the Marvel has been one of the longest running office machines ever. I greatly enjoyed your article – nicely done.” —Curtis Scaglione, 2018

“American Stationer and Office Manager – Volume 91 – Page 30, 1922:

… THE Sam’l C. Tatum Company of Cincinnati, O., have sold their line of Office Punches to a new company recently formed, known as the Delmar Manufacturing Company. The new company will specialize on office punches and expect to add …

National Association News – Volumes 7-8, 1923:

The Sam’l C. Tatum Company, of Cincinnati, Ohio, announces that it has disposed of its punch department In the Delmar Manufacturing Company, of Cincinnati, which is a new company and expects to introduce several additional punches for …

US Patent No. 1,154,294 dated September 15, 1915

I have not been able to confirm the day Wilson-Jones acquired the right to the Improved Hummer line of hole punches, but believe it to be the mid 1920’s. It is more likely Ralph Wilson bought Delmar Manufacturing Company in total and put more effort towards the production of the hole punches and as a result made the Marvel a major money maker for his company.

I became interested in this line of machines when I noticed everyone on eBay trying to sale an Improved Hummer or a Marvel always believed their example was from the 1940’s – 1950’s. Through my own curiosity, I learned that both machines can date to 1915 and as late as a few years ago. Of course, which manufacturer’s name is on the machine, which improvements or on the machine, and what color the machine is can help to establish a pretty close date of manufacture.

Here are a few of my machines and some of my research: http://mystaplers.com/Punches.html”

–Curtis Scaglione, 2018

When I was 15 years old in 1963, I bought my first stapler from Wilson Jones Co. I worked as a banker, accountant and teacher and I bought some new ones during that time. But me Wilson Jones stapler was always me preferred one. It is now my unique stapler. No one beats it.

Thank you

How much is this to hole puncher worth

We have a piece of equipment Wilson Jones Marvel WJ Stock No. MO-10. We have no idea what it was used for. It seems to cut very fine strips of paper, as if you would be cleaning up the edge of a piece of paper. Could you assist in identifying what this was used for and what it is called? Thank you.

Could it be a letter opener? We still use one at the office I work in!

I have an old trifold fan that advertised for a florist as made by Oak Specialty Co., Chicago, ILL.

Wanted to know date made

Thank you

Is the Wilson Jones Company still in business in Chicago? I have an old wooden box with that name on it. A top board is missing on one side

I have old/antique hole punch machine which is heavy metal and in large size and i want to sell out, I will sell who give me good amount

I have 0323-12 personal finance record 6 ring 8.5 x 5.5 with Dollars and sense on front in gold on black book and looking for value of it

Gentlemen I have an antique piece of office equipment made in 1932 Wilson Jones Company and wondered if you would be interested in it. It has the original wheels and handles etc. Invented by V W Gideon Oct 11, 1932. I believe it’s called a posting tray? I can send pictures if interested?

Where in Elizabeth, NJ was the Wilson Jones factory located and when did it close down?

Tengo una perforadora Wilson and Jones co. Of one hole,inneed infortation of manufacturing thanks

I would like to get more information on Irving Pitt as to where he learned of the three-ring binder mechanism. I understand that he learned of it from Joseph Smith of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The angel Moroni had the gold plates with three ring binding mechanism. I understand that Irving Pitt learned of this from Joseph Smith and or his followers and therefrom invented the 3-ring binder. Do you have any further information of this. I would like to know.

I found some old ledger paper with a logo that says Wilson Jones Record Keeping Essentials Form N4-D. Anyone have any idea when this could be from?

I have one only single punch ando Say “oil occasionally Wilson co”

How much are they worth now?

What year was the Marvel model number 60 two hole cast iron punch made?

Want to know how much the two hole punch is worth? Check eBay – prices are ~$15+. You can pick one up cheap, give it a fresh coat of paint, and it will look great on your desk.

I have a small metal spring clipboard that is from the DeLuxe line. Stamped on the back with the number 13.

I have found a (12″X3″) booklet labeled Oklahoma Notes S 1820. It looks kind of like a checkbook. About 2/3rds have been used but I cannot find good info on this. It does have Wilson Jones Co did print them. If you have any information to share, I would appreciate it.

Sincerely,

Beverly A Corey

If this was $2.00 then, how much is this worth today?

I have a old paper punch that I would like to donate

How much is the two puncher worth???

I’ve just acquired the Marvel Wilson 2 hole punch, missing the slide but works perfectly. My mom has passed but had left it in a box of office supplies. I would love to see if there is a slide available for it.

I’ve displayed it on my office desk, love having a piece of history.

To Joanne Malinowski….

Assuming your dad was Joe

I worked with Joe in the 70s and 80s.

He was a great guy. Nice too everyone. Mentored me in my youth(was in my 20’s)

My father worker for Wilson Jones for most of his career – 1940’s to mid-1980’s, I think. After the company left the Franklin Boulevard site (around the mid-1960’s), they moved to a new facility in Niles, IL, near the former Leaning Tower YMCA (on Touhy and Melvina). That factory was closed in the mid-1980’s. The site is now occupied by the Target and Costco stores.

Very few people know that Harvey P. Jones designed and built the flat-roofed covered bridges of Madison County, Iowa in the 1870’s to early 1880’s. Yes, the ones featured in “The Bridges of Madison County” movie! He was clearly a very talented inventor and engineer.

Do you still make the RAVEN Black 241-40N?

Is the company still in business and making the loose leaf spread sheets??

I have a rare OSS Weapons, June 1944, that I bought in a Chicago bookstore in 1967-1968 and am working to authenticate. I grew up in LaGrange Park. This manual is roughly 25 pages and has a two hole punch in every page, down the left-hand side. The inserted metal clip that holds the pages is stamped “Wilson Jones” on both sides with the back side also having a circle with the initials “WJ” inside the circle.

This metal clip has two slide bars on the front side that slip over the ends of the clip to keep it in place. A slight bit of rust is present on the clips.

If you could put me in touch with anyone from the Wilson Jones company, or another expert, that specializes in their history, especially their metal 2-hole insert clips from circa 1940’s, I would be greatly appreciative.

My father-in-law died and we were cleaning out his house. We came across an old heavy, rusty device with “Wilson Jones Co. Chicago Patented ME in USA” on the bottom. There are no words on top, but a “1” . It is apparently missing the metal slide piece that goes through the middle. (I do not know what it is called.) The lever pulls down smoothly. U tried it and it cuts two holes in paper.

Are you interested in acquiring it?

Awesome work, of course! Commenting to let others know that the facility at 3300 Franklin has been restored and it’s looking good. Restoration over destruction – thumbs up!

I own a Marvel Wilson and Jones 2 hole punch, does not have guide bar or the rubber on the bottom but still works great. Would like to sell could you please tell what it’s worth on today’s market, and how can I find potential buyers