Museum Artifact: Wilson Success Mid-Iron Golf Club, c. 1920s

Made By: Thos. E. Wilson & Co. / Wilson Sporting Goods, 2037 N. Campbell Ave., Chicago, IL [Logan Square]

Today, a typical set of Wilson golf clubs includes “woods” made of titanium and “irons” machined from flexible steel alloys. But once upon a time, these crooked fairway sticks were exactly what they purported to be—utilizing hickory for the shafts, persimmon for the wood heads, and hand-forged iron for, well, the irons. Look no further than Exhibit A from our Made-in-Chicago collection, a Wilson “Success” 1 Mid Iron dating from around 1920, for evidence of the genuine article. Golf as the Scots intended it.

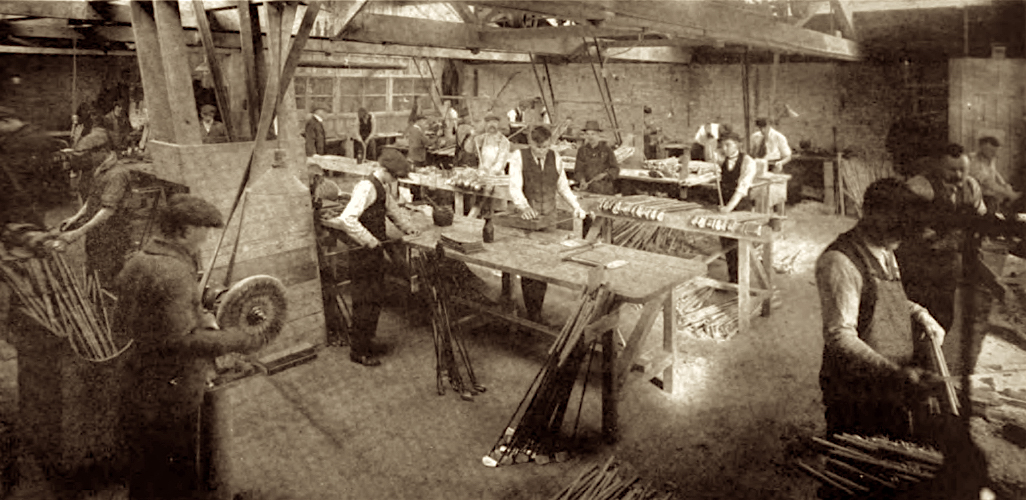

In 1921, Fort Dearborn Magazine toured some of the Wilson factories and gave us a firsthand account of how a club like this one would have been made:

In 1921, Fort Dearborn Magazine toured some of the Wilson factories and gave us a firsthand account of how a club like this one would have been made:

“The first operation in the making of golf clubs which we witnessed, was the forging of the heads of the ‘irons.’ They are hand-forged with hammer and anvil by big-muscled men, in the following manner: Taking a long rod of soft steel or ‘Swede’s iron,’ one of these men thrusts it deep into the forge-fire. Then, laying the glowing white tip of the rod on the anvil, two men beat it with alternate blows of heavy hammers. Suddenly it bends down, with a snake-like motion, and the head is roughly formed. Once more the rod is thrust into the fire, and this time the partly formed head is laid on another anvil, where one man alone hammers, turning it slightly, and shaping it with little blows to give it the right degree of ‘lie’ and ‘Ioft.’ According to requirement, it will come from his hand in the form of one of the main irons, such as the midiron, mashie, niblick, driving iron, approach cleek or putter, or a mongrel iron such as the pitching iron, lofter or mid-mashie.”

[The golf club manufacturing operations of Thos. E. Wilson & Co., 1921]

[The golf club manufacturing operations of Thos. E. Wilson & Co., 1921]

The “Success” series was one of the earliest golf club sets produced by a Wilson company still in its sporting goods infancy. The business wasn’t necessarily a humble upstart, however. Originally formed in 1913 as the Ashland Manufacturing Co., the firm was a subsidiary of the long-tenured Chicago meatpacking giant known as Schwartzchild and Sulzberger. The “Ashland” name simply came from the first factory location at 4100 S. Ashland Ave.

Like a lot of the major Chicago meatpacking powers of the era, Schwartzchild and Sulzberger (later Sulzberger and Sons) had been expanding its industrial pursuits to make use of the boundless excess resources coming out of the stockyards.

Animal gut by-products, for example, could be recycled into cleaning products, surgical sutures, and strings for musical instruments and tennis rackets, among other things. The purpose of the Ashland MFG Co. was to explore all these avenues—with departments for everything from football equipment to automobile tires and phonograph records

Animal gut by-products, for example, could be recycled into cleaning products, surgical sutures, and strings for musical instruments and tennis rackets, among other things. The purpose of the Ashland MFG Co. was to explore all these avenues—with departments for everything from football equipment to automobile tires and phonograph records

The catch-all business strategy seemed practical enough, but when an overstretched Sulzberger and Sons was abruptly forced into a receivership and taken over by a New York banking conglomerate in 1914, Ashland MFG and every other subsidiary looked doomed to get swept up in the implosion.

That was, however, before their knight in shining armor arrived on his trusty steed.

Mr. Wilson Saves the Day

“It was the last of February or the first of March, the day he came over here,” a security guard at the old Sulzberger plant later recalled, excitedly recounting his experience like it was a Bigfoot sighting. “A wretched day it was, too—rain and snow and sleet. I was standing in this box when he drove in, and he pulled up right side of me. ‘I’m Mr. Wilson,’ says he; ‘You might have heard I was coming over here. I thought I’d like to introduce myself.’ And would you believe it, sir, he asked me my name! And him and me shook hands. And then he asked me what was the way to the office, and where should he park his car?”

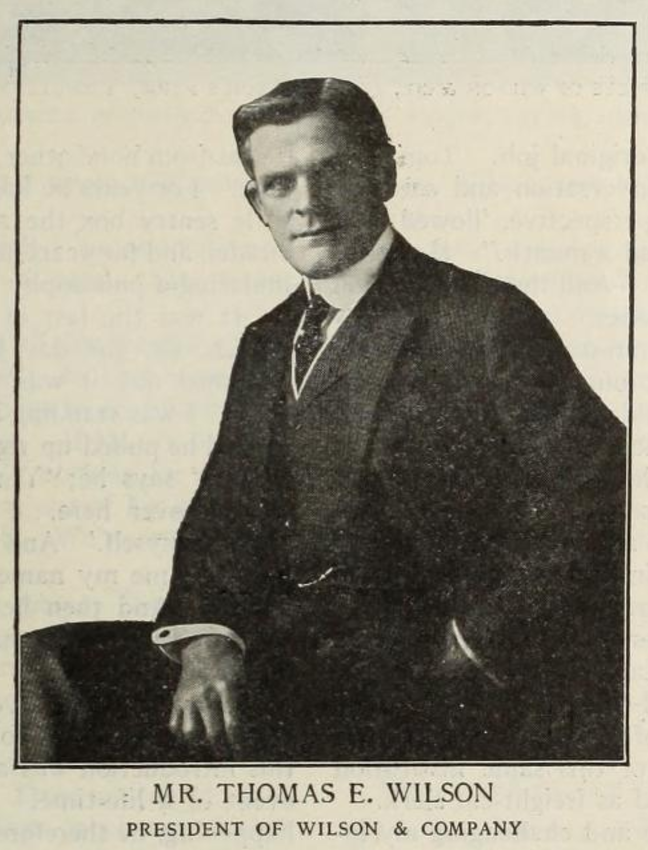

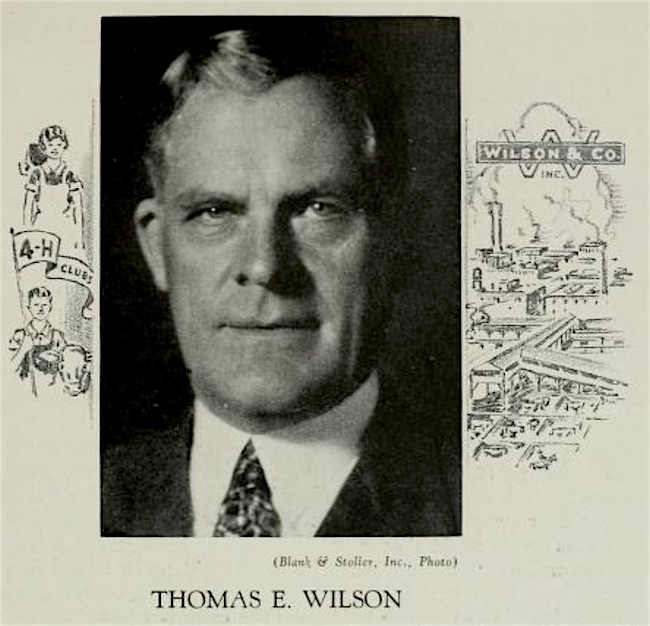

One can forgive the guard his childlike enthusiasm. A lot of people tended to remember the time and place they first encountered Thomas E. Wilson.

As the designated savior of Sulzberger and Sons, Wilson arrived as an established folk hero—a former railway worker who had talked his way into a job at the meatpacking firm of Nelson Morris and Co. at age 19, eventually ascending all the way to the company presidency through grit, smarts, determination, and—oddly enough—genuine friendliness.

As the designated savior of Sulzberger and Sons, Wilson arrived as an established folk hero—a former railway worker who had talked his way into a job at the meatpacking firm of Nelson Morris and Co. at age 19, eventually ascending all the way to the company presidency through grit, smarts, determination, and—oddly enough—genuine friendliness.

He was born in London, Ontario, Canada, in 1868, moving to Chicago with his family at the age of nine. Now, at age 47, Thomas Wilson was the young buck of Chicago’s stockyard tycoons—handpicked by that conclave of east coast moneymen to set the Sulzberger business back on course.

“One day in the fall of 1915 I received a telephone message from the Blackstone Hotel from two New York bankers who said they wanted to see me,” Wilson was quoted in the 1917 book, Men Who Are Making America. “I had a long talk with them. They wanted to engage me—at any salary I wanted to name—to take charge of Sulzberger & Sons Company. … [They] wanted to have it built up and developed in the best way possible. After proper consideration, I felt compelled to turn down their proposition.

“Shortly after I had rejected the offer, I met a friend in Chicago who hailed me with: ‘So you are going with Sulzberger’s.’

“‘No, that’s all off,’ I told him.

“‘Oh, yes, you are,’ he came back. ‘I was talking with some New York bankers and they told me you were to make the change but that you didn’t know it yourself yet. They told me they would get you yet.’

“They did. They worked out a proposition, giving me a very substantial interest in the business and everything else I wanted. They were very liberal. And so here I am.”

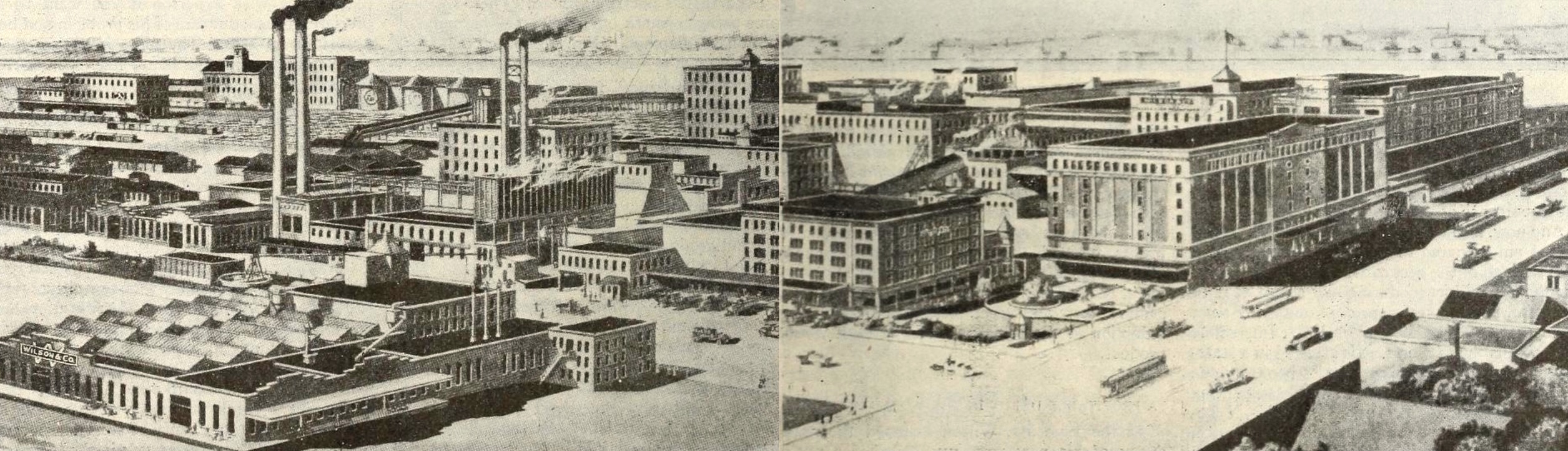

[The Sulzberger meatpacking complex becomes Wilson & Co. in 1916]

[The Sulzberger meatpacking complex becomes Wilson & Co. in 1916]

The fanfare around Tom Wilson’s arrival went a bit further than handshakes with the parking attendants. The very company itself, in fact, was rechristened for the occasion—officially introducing its new identity to the public on July 21, 1916. Sulzberger was no more. Wilson & Company was now in business.

Only… was it actually named after Thomas Wilson? Logic would darn well suggest so, but according to several accounts of the tale, those mysterious “New York bankers” actually had been planning to use the Wilson name for two years, hoping to align their meatpacking acquisition with the popular man in the White House, Woodrow Wilson. By later selecting Thomas Wilson as the new company president, then, they had either stumbled on a delightful coincidence or purposefully elevated a man to power based on the marketability of his moniker. Either way you slice it, it worked out swimmingly.

[Thos. E. Wilson & Co. catalog, 1919]

[Thos. E. Wilson & Co. catalog, 1919]

Mission Statements

Of course, a name change alone wasn’t going to inspire total confidence from every corner of the Wilson company. Many workers, including those in the Ashland MFG Co., remained unsure of their long term fates under their new boss. According to a 1917 article in The World’s Work, however, Mr. Wilson—tall, square-jawed, and blue-eyed—rallied his troops from the beginning with a cinematic “we’re all in this together” pep talk.

“I’m here, boys,” he supposedly told them, “and I’m all that’s coming. But I’m not a wizard. I can’t do this wonderful thing that we’re all so anxious to do, just by myself. I’ve got to have you. If there’s any one here who has a notion he’s working for me, the quicker he gets that notion out of his head, the better it will be for us all. We’re working together.

“And there’s one thing more: There’s a new name going to mark our products—the name of ‘Wilson & Company.’ I’m Wilson, but don’t forget that you’re the Company. The Wilson label has got to be our letter of recommendation. That label has got to stand for purity—and cleanliness—and quality. From now on I look to you all to make the Wilson label an absolute guarantee.”

[Wilson & Co. employee picnic, held at Tom Wilson’s “Edwellyn” farm near Lake Forest, IL, c. 1917]

[Wilson & Co. employee picnic, held at Tom Wilson’s “Edwellyn” farm near Lake Forest, IL, c. 1917]

According to the same publication, the manager of the Ashland wing of the company later piped up and asked, with considerable trepidation, “What are you going to do with the Sporting Goods Department, Mr. Wilson?”

“I’m going to make it the biggest thing of its kind in the world!” the boss responded without a flinch. “Go to it.”

If this all sounds like folklore, it’s because it probably is. But then again, we’re talking about articles written less than two years after the fact. If Wilson hadn’t won over his employees with his introduction, he seemed to have legitimately done so shortly thereafter when his ass started cashing the checks his mouth had written.

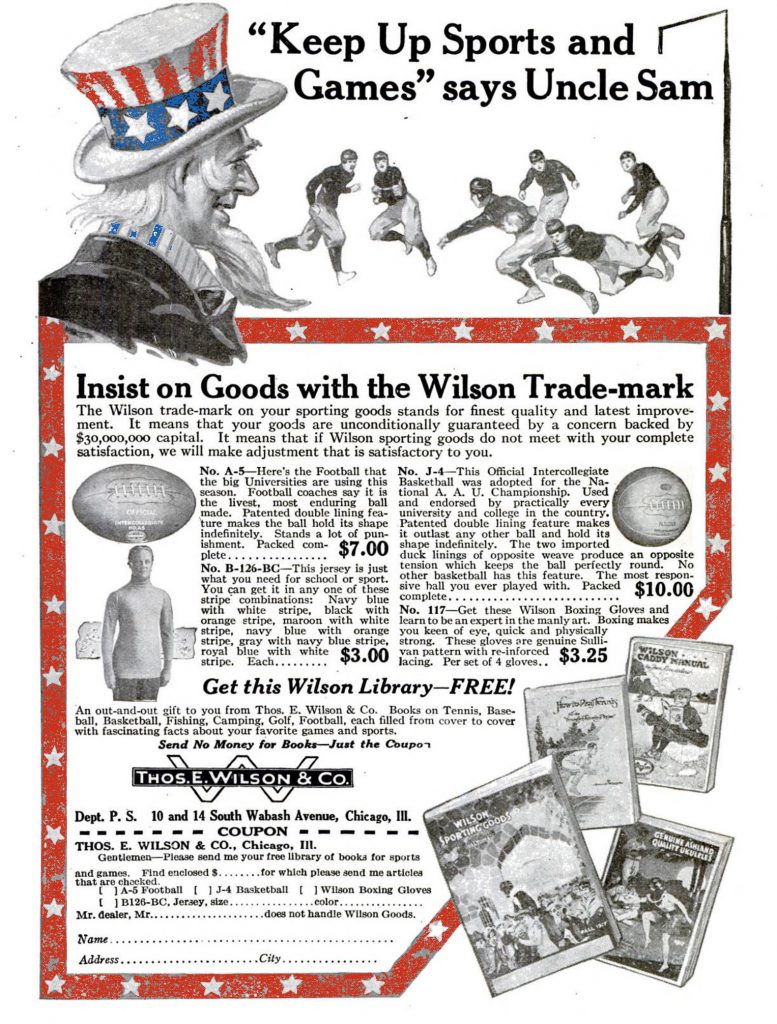

[An early ad for Thos. E. Wilson & Co., 1917]

[An early ad for Thos. E. Wilson & Co., 1917]

“It shortly developed that no matter how humble the individual, if he had an idea, or a complaint, or a grievance, he could take his case right to Tom Wilson and be assured of a courteous hearing,” journalist F. Burnham McLeary wrote for The World’s Work.

McLeary also quoted one of the Wilson department heads, who exclaimed, “Why, there isn’t a person in this place who doesn’t know that Tom Wilson will stand back of him and see that he gets a fair show.”

“I would rather waste a minute, now and then,” Wilson said for himself, “than to have any one going around here proclaiming that I’m utterly aloof and inaccessible. Besides, there’s nothing like talking with a person if you want to appreciate the exact nature of his problem and be in a position to help. The mere inflection of the voice, the turning of a hand, may mean everything.”

“I would rather waste a minute, now and then,” Wilson said for himself, “than to have any one going around here proclaiming that I’m utterly aloof and inaccessible. Besides, there’s nothing like talking with a person if you want to appreciate the exact nature of his problem and be in a position to help. The mere inflection of the voice, the turning of a hand, may mean everything.”

Open communication played an important role in how Wilson handled the Ashland Manufacturing business. As promised—rather than gutting the animal guts operation—he did indeed give it a renewed focus and a new name, as well—Thos. E. Wilson & Company. Then, using tactics he’d developed at the Morris Company, he went out on a quest to acquire smaller businesses with the goal of improving and expanding Wilson & Co’s sporting goods operations. This included snapping up the Sells MFG Co. of Canton, Ohio (makers of leather baseball gloves and balls) and Chicago’s Indestructo Caddy Bag MFG Co.—a rising force in golf equipment.

As soldiers started coming home from World War I, there were loads of new jobs opening up at Thos. E. Wilson & Co.’s “little red schoolhouse” factory at 43rd Street and Hermitage, as well as a new five-story warehouse at 701 N. Sangamon. There were also sales and satellite manufacturing work at several other facilities, including a golf club plant at 89th Street and S. Ada Street—where our “Success” iron may have been forged. In short order, new distribution offices were established in New York and San Francisco, as well.

[Wilson employees in 1921, working on the company’s original sporting good, the tennis racket]

[Wilson employees in 1921, working on the company’s original sporting good, the tennis racket]

Taking aim at the market shares of the recently deceased A.G. Spalding (another Chicagoan), Wilson put the pedal to the metal, turning Thos E. Wilson & Co. into a company with a million and a half invested capital within its first year, making it the second biggest sporting goods maker in the country practically overnight.

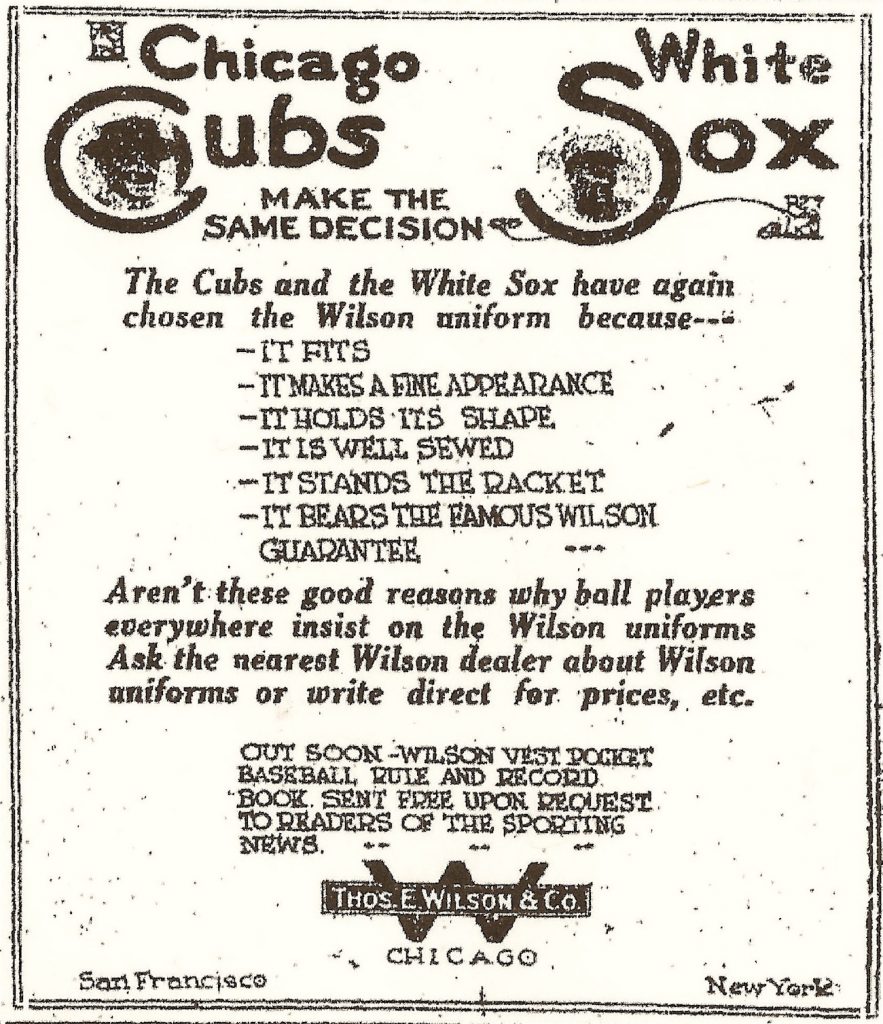

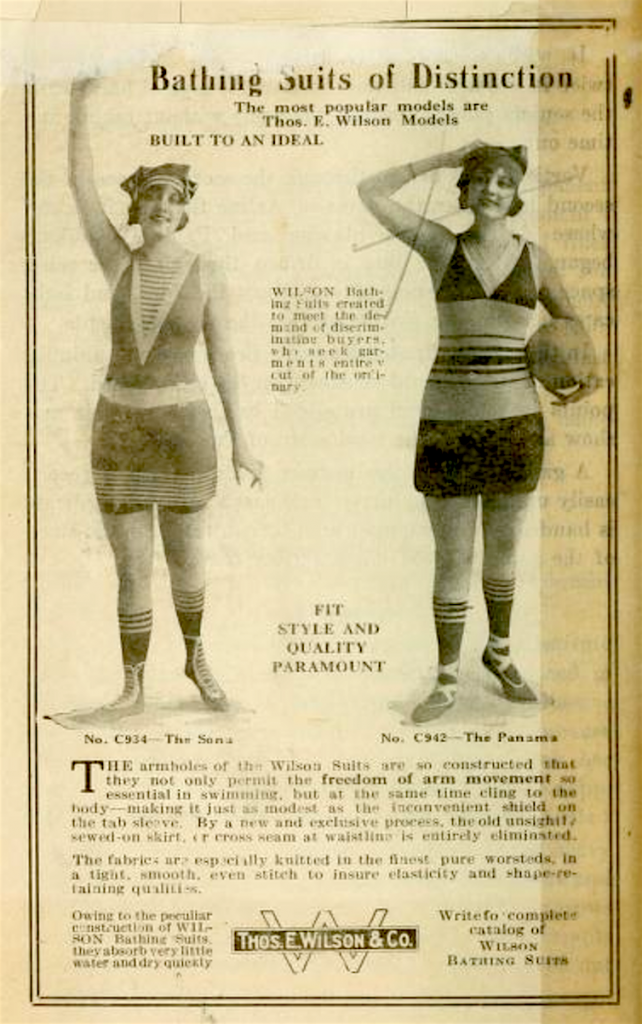

Wilson took full advantage of what he knew to be his biggest edge over most national competitors: the raw materials for much of his sporting equipment could be funneled directly out of his own primary concern—the meatpacking wing of Wilson & Co. This meant rapid production, self-sufficiency, savings on transport, and the ability to make a higher quality product—be it a racket, baseball mitt, golf club, football, etc.—at a lower retail price. Even the wool from the stockyard sheep went into making everything from decidedly unskimpy ladies swimsuits to the official jerseys of both the Chicago Cubs and White Sox—or Black Sox, as the media would soon start calling them.

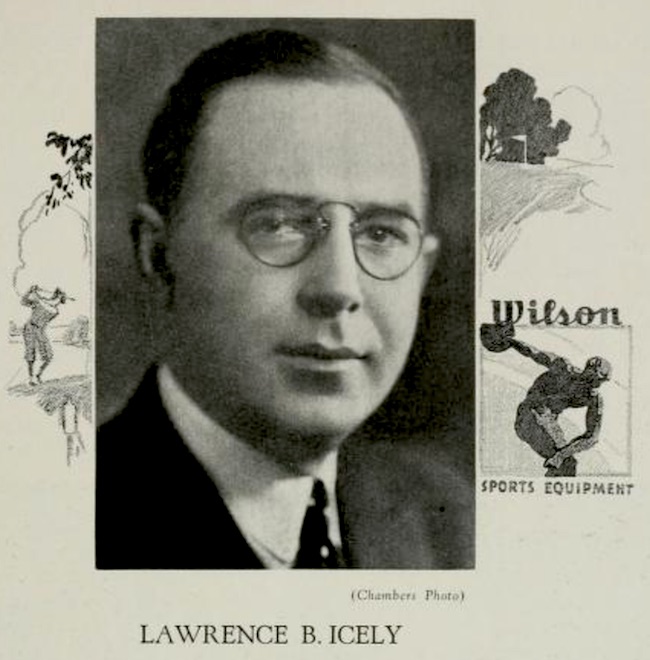

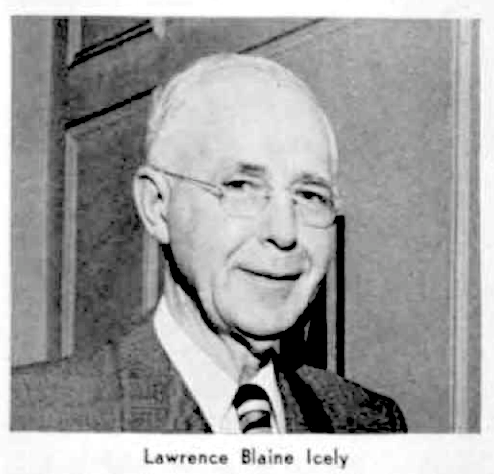

Wilson was also smart enough to avoid spinning too many of his own plates, choosing instead to delegate authority to worthy managers. While he oversaw the entirety of the far-reaching Wilson & Co. business, he quickly brought in a younger version of himself—33 year-old Lawrence B. Icely—to serve as the president of the sports department.

Icely, an Illinois native and a dedicated sportsman in his own right, had experience in the industry, but he also shared Wilson’s ability to grab the reins and inspire his workforce.

Icely, an Illinois native and a dedicated sportsman in his own right, had experience in the industry, but he also shared Wilson’s ability to grab the reins and inspire his workforce.

Golfdom Magazine called Icely—in contrast with his name—“a tremendous worker” who “kept in close touch with all internal elements of the Wilson business through a steady program of expansion, as well as giving generously of his time, effort and ability to the promotion of sports and the growth and stabilization of the sports good industry.”

In lockstep with Tom Wilson, Icely quickly chucked out the extraneous parts of the old Ashland business—the phonographs and tires, etc.—and carved the Thos. E. Wilson Co. into its recognizable modern form as a sports company, through and through.

Rise of the Big W

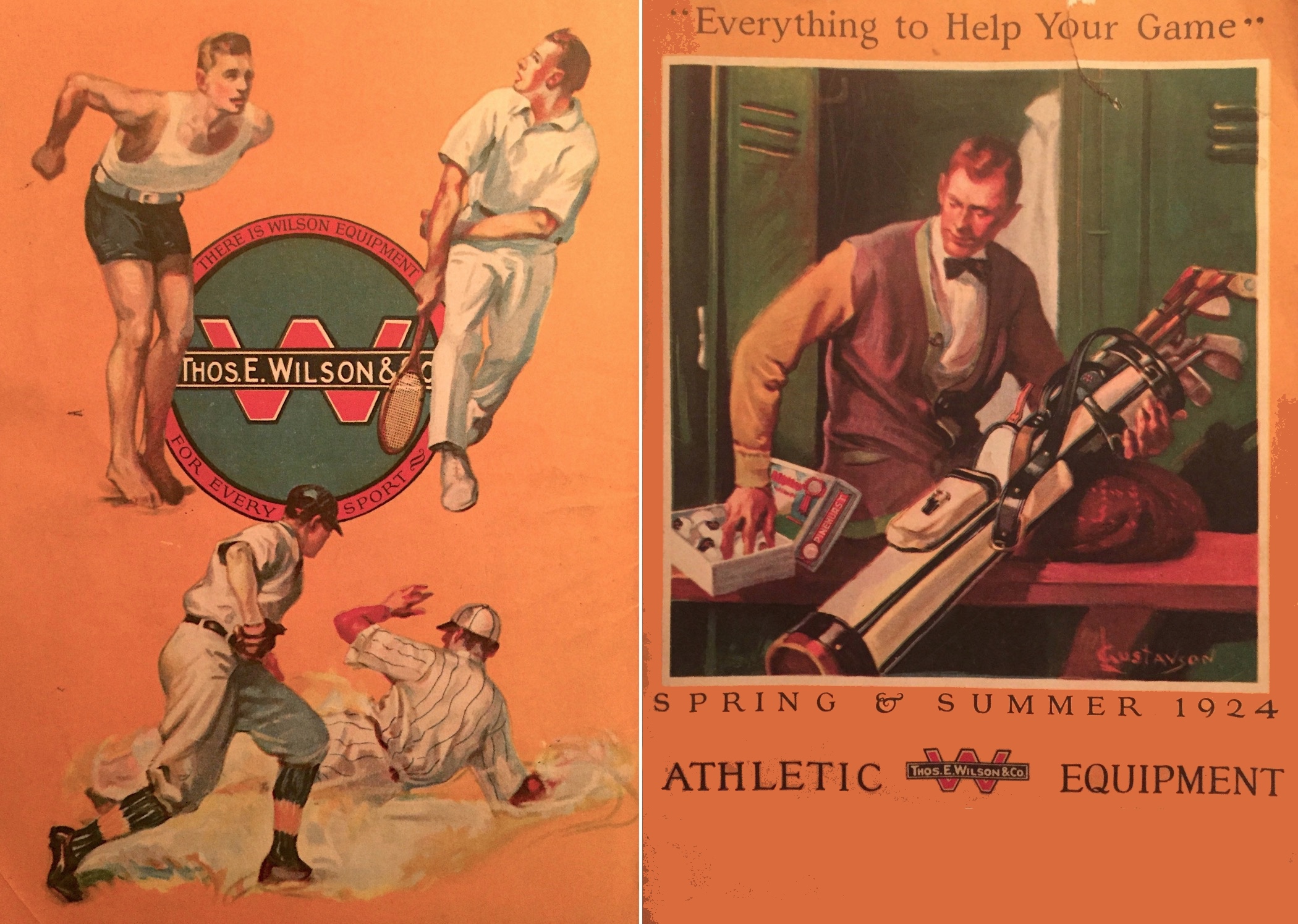

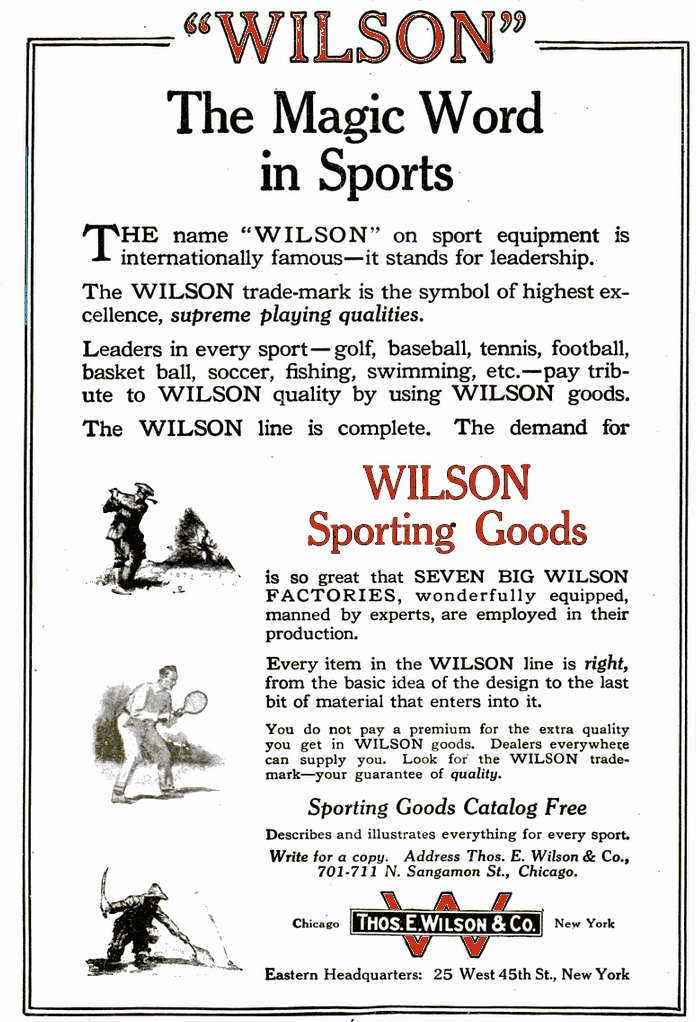

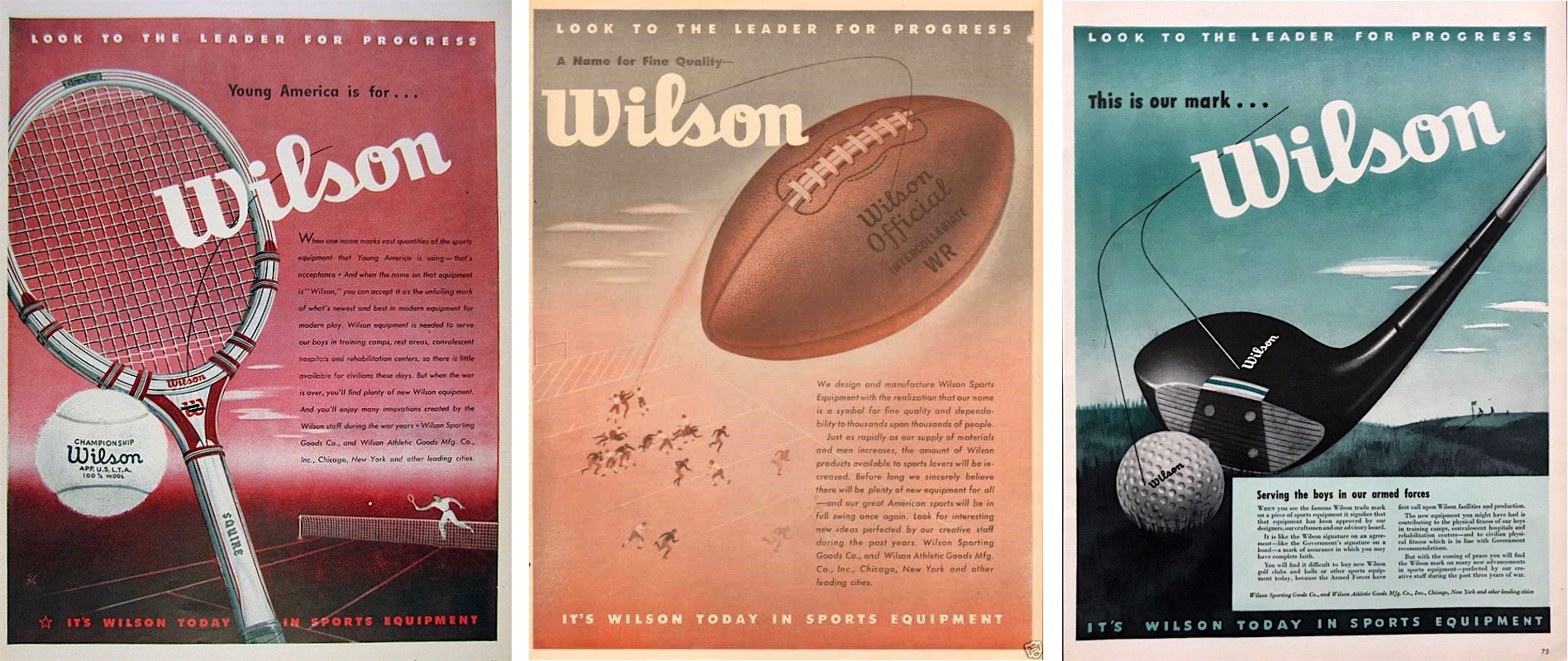

“WILSON—The Magic Word in Sports,” read a 1919 advertisement, further describing the company as “internationally famous” and “a symbol of highest excellence.” Of all the lasting, mainstream American commercial brands of the 20th century, it’s hard to imagine too many matched the zero-to-sixty growth spurt of Wilson during its first five years.

“WILSON—The Magic Word in Sports,” read a 1919 advertisement, further describing the company as “internationally famous” and “a symbol of highest excellence.” Of all the lasting, mainstream American commercial brands of the 20th century, it’s hard to imagine too many matched the zero-to-sixty growth spurt of Wilson during its first five years.

“The demand for WILSON Sporting Goods is so great,” the ad boastfully added, “that SEVEN BIG WILSON FACTORIES [all caps], wonderfully equipped, manned by experts, are employed in their production.”

Part of the reason those factories were “manned by experts” is that most of them were former independent, established operations that had been absorbed into the Wilson web, with the original craftsmen kept aboard to continue plying their trade.

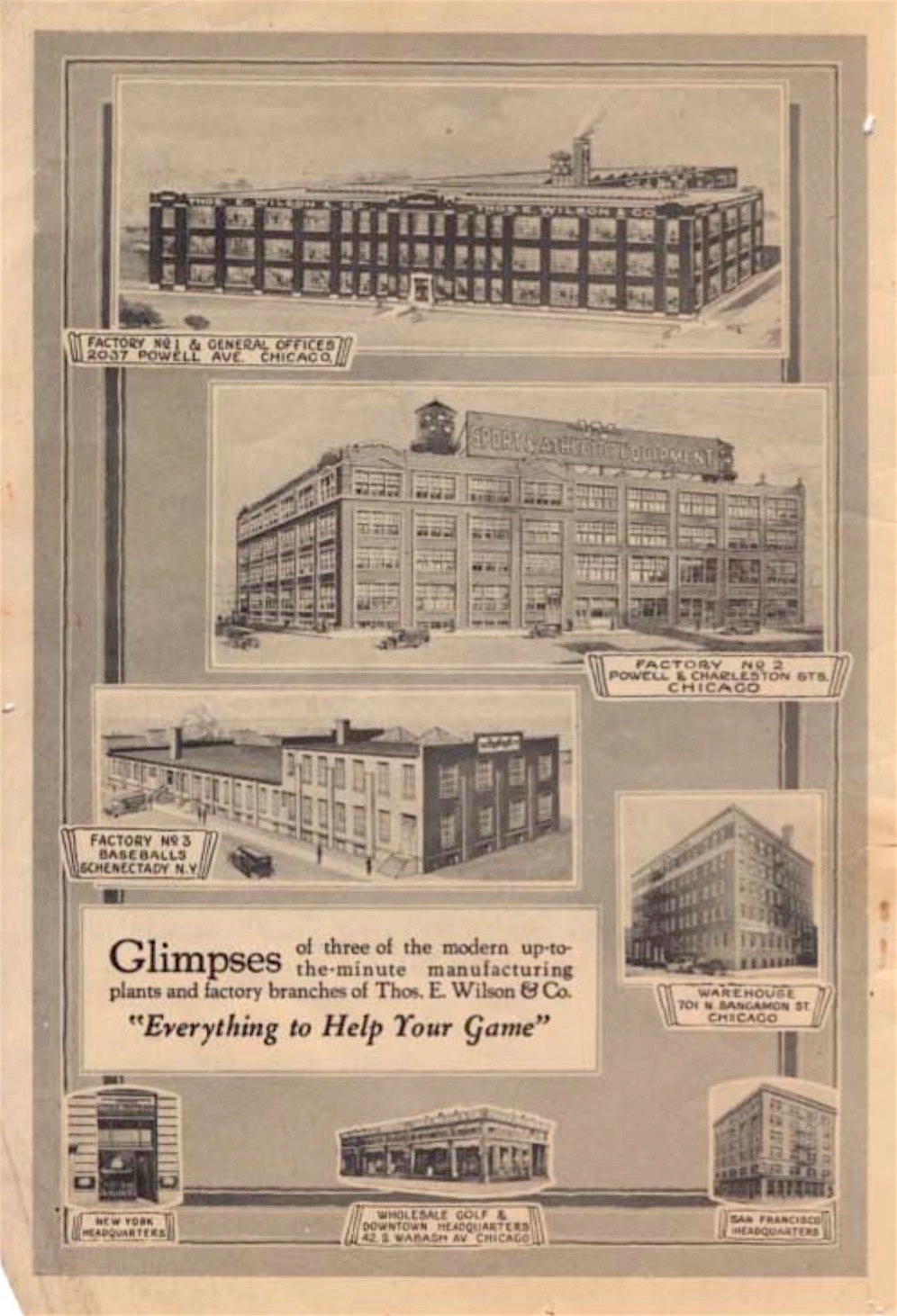

By the early 1920s, there were more than a dozen plants operating under the Wilson banner across the country, but the three central facilities remained firmly planted in Chicago—the warehouse at 701 Sangamon Street, the expansive “Factory No. 1” in Logan Square at 2037 N. Powell Ave. (now known as Campbell Ave.), and “Factory No. 2” just up the street at Campbell and Charleston Street. There was also a downtown office and wholesale golf headquarters inside the Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building at 42 S. Wabash Ave—selling fine selections like the “Success” iron in our collection. These combined facilities would employ upwards of 800 Chicagoans at any given time, even into the lowest years of the Depression. Today, only the Wabash location is still standing.

[Wilson’s main factories and offices, from the company’s 1924 catalog]

[Wilson’s main factories and offices, from the company’s 1924 catalog]

Tracking the locations of some of Wilson’s early “off-campus” manufacturing plants is a far tougher task, indeed. Wilson and Icely were on the road making acquisitions at the same pace other businesses buy new stationery. Between the wars, the duo’s list of conquered sporting good manufacturers included:

⇒ [The aforementioned] Sells MFG Co. (Canton, OH)

⇒ [The aforementioned] Sells MFG Co. (Canton, OH)

⇒ [The aforementioned] Indestructo Caddy Bag Co. (Chicago)

⇒ Hetzinger Knitting Mills (Chicago)

⇒ Chicago Sporting Goods Co.

⇒ Horace Partridge Co. (Boston)

⇒ Lowe and Campbell Co. (Kansas City)

⇒ Carolina Sporting Goods Co. (Charlotte)

⇒ Treman-King Co. (Ithaca, NY)

⇒ O’Shea Knitting Mills (Chicago)

⇒ Kings Sportwear (Chicago)

⇒ Walter Hagen Golf Equipment Co. (Grand Rapids)

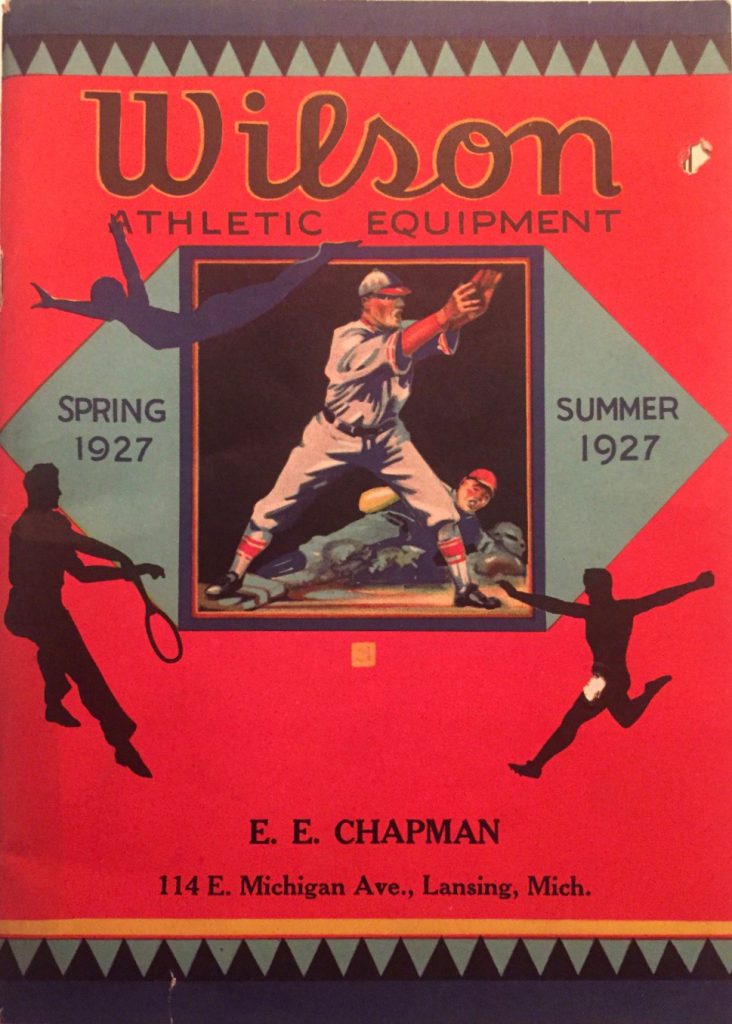

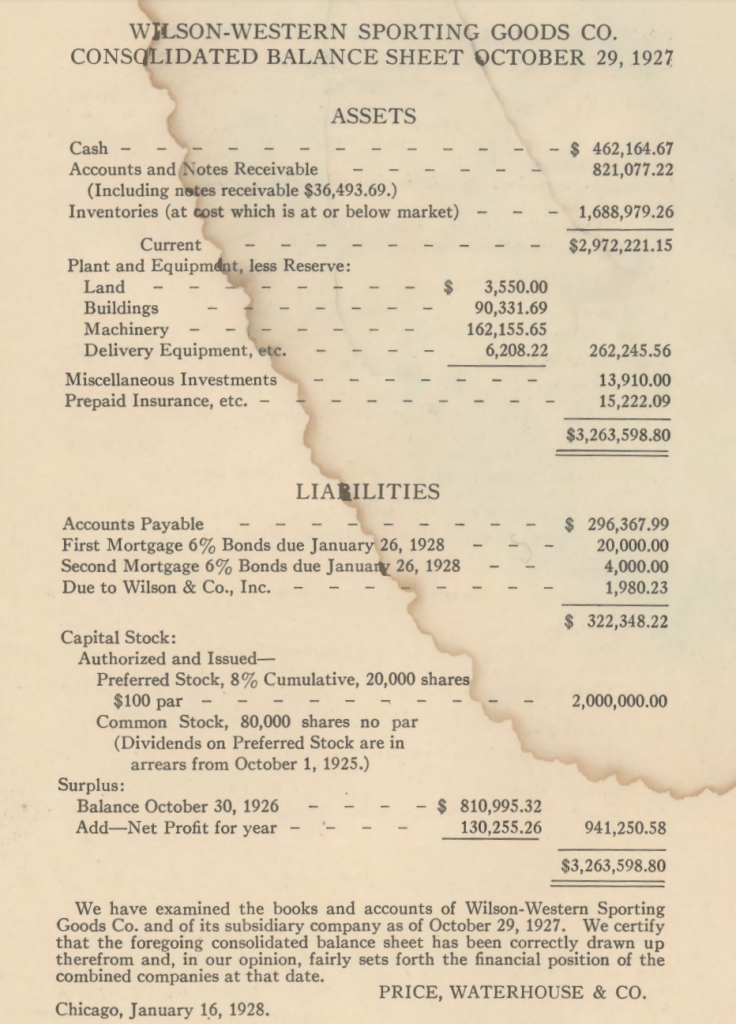

Not included in the list above, but more significant than any, was Wilson’s 1925 merger with Chicago’s Western Sporting Goods Co., leading to a short-term company name-change to the Wilson-Western Sporting Goods Co.—in use up to 1931. During this same period, around 1927, the company also debuted a new cursive block-letter logo, usually in red print. The logo survived the simplified name change to “Wilson Sporting Goods Co.” in 1931, and the branding has carried on mostly unchanged ever since.

“Everything That Helps Your Game”

Materials, mergers, and a swank logo can only get you so far. As Wilson & Co. stared the Depression in the face, they already felt well positioned as a company associated with quality products at reasonable prices. Even so, the rules of sports marketing have always been the same—people want to use what the pros use. And thus, star athlete sponsorships became a requirement.

Rather than just paying a few stars to appear in magazine ads, though, Wilson took things an innovative step further, forming actual advisory committees of accomplished athletes to help test new products and offer their insights on design changes. This, in turn, made the player’s eventual endorsement something that carried a bit more legitimate merit and cache for the company and the buying public

Rather than just paying a few stars to appear in magazine ads, though, Wilson took things an innovative step further, forming actual advisory committees of accomplished athletes to help test new products and offer their insights on design changes. This, in turn, made the player’s eventual endorsement something that carried a bit more legitimate merit and cache for the company and the buying public

In the 1920s, the Ray Schalk catcher’s mitt—named for and endorsed by the future White Sox Hall of Famer—became the gold standard in baseball. Notre Dame legend Knute Rockne was an advisor on the creation of a broad line of new football equipment, and golf champion Gene Sarazen worked with the company to help invent the modern sand wedge—with a steel shaft and flanged club face.

In the years after World War II, as Americans embraced the new leisure opportunities of peacetime, Wilson signed up tennis stars Jack Kramer and Bobby Riggs, golf champ Sam Snead, women’s golf phenoms Babe Didrikson Zaharias and Patty Berg [whom Icely assisted in the funding of the new LPGA], footballer Frank Gifford, and baseball stars Bob Feller and Ted Williams.

[Wilson golf advertisement from 1948, featuring a roster of pro stars]

[Wilson golf advertisement from 1948, featuring a roster of pro stars]

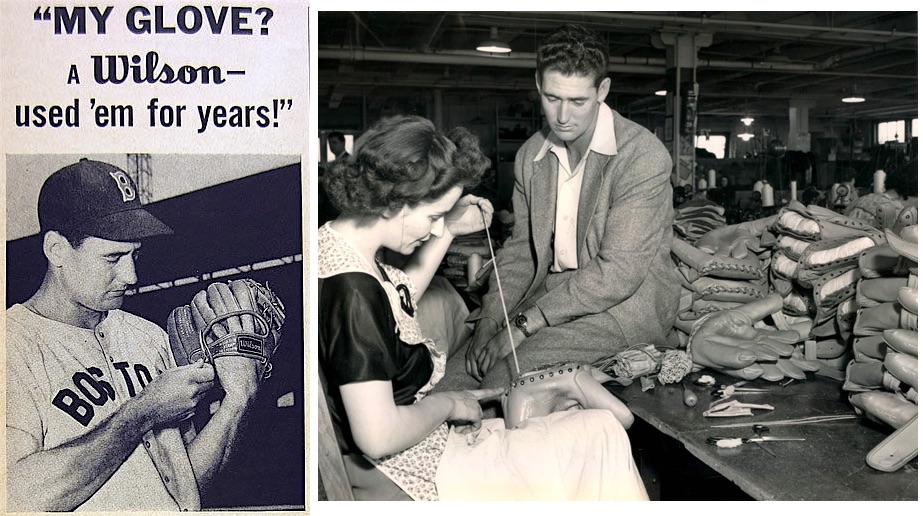

Ted Williams, the great but occasionally curmudgeonly Red Sox star, was about a million times more famous for his hitting than his fielding. Nonetheless, he hocked Wilson gloves for years, even visiting the factory in the late ‘40s to meet with the men and women who spun leather into gold.

[Teddy Ballgame in a 1956 ad for Wilson gloves (left) and visiting the Chicago factory in 1947 (right)]

[Teddy Ballgame in a 1956 ad for Wilson gloves (left) and visiting the Chicago factory in 1947 (right)]

The 1940s also saw the beginning of the long-term relationship between Wilson and the rapidly growing National Football League, as Chicago Bears owner George Halas got the league to make Wilson the official supplier of its footballs. To meet the demand, Wilson worked out a deal with a highly respected local Chicago tannery, the Horween Leather Co., to produce the quality leather for each and every ball. The footballs were initially sewn and completed in Chicago, as well, but by 1955, that operation had moved to one of Wilson’s acquired plants in Ada, Ohio—the Ohio-Kentucky MFG Co. Nearly 70 years later, all NFL footballs are still made with Horween leather at the Wilson factory in Ada.

Good Health is Good For Business

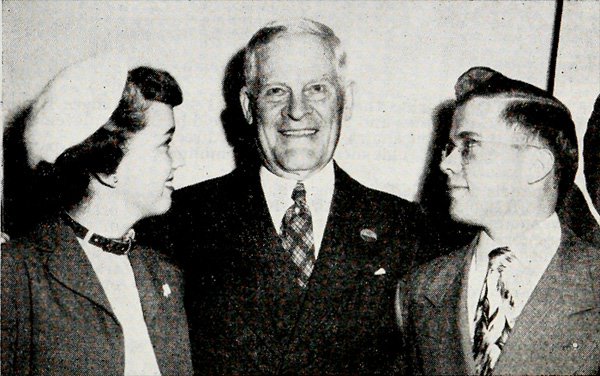

Thomas Wilson and Lawrence Icely remained fixtures of the business through its first 30 years, and are probably still the two men most responsible for Wilson Sporting Goods’ roughly $1 billion in annual income today. As late as the 1940s, with both men near or well past retirement age, they found new ways to effectively connect with their employees, their industry, and the general public.

For the entirety of his career as Wilson’s president, Thomas E. Wilson was actively involved with the National 4-H Club Congress, welcoming kids from across the country to attend an annual exposition at the Stockyards, where they could meet sports and film celebrities, explore career opportunities, and learn about productive, healthy living.

[Thomas Wilson (seated) watches as famed pilot Amelia Earhart pins a ribbon on children at the 1932 4-H Congress in Chicago]

[Thomas Wilson (seated) watches as famed pilot Amelia Earhart pins a ribbon on children at the 1932 4-H Congress in Chicago]

As the sporting goods part of the business became increasingly important, Lawrence B. Icely followed Wilson’s lead, realizing that a populous interested in fitness wasn’t just to the benefit of society as a whole, but to the profits of a sports equipment company, as well. Maybe I should have written that in the reverse order, but you get the point.

In 1942, Icely wrote an editorial in The Rotarian, calling out his own fellow middle-aged businessmen for a dangerous trend toward laziness and expanding waistlines.

“The attack on Pearl Harbor was not the first blow dealt my country,” he wrote. “The first one came two months earlier when Brigadier-General Lewis B. Hershey, head of the Select Service System, announced that of the first 2 million young men who walked up to selective-service and Army board doctors, 900,000 walked away rejected . . . physically deficient. Forty-five percent unfit for military service because of disease or defect!

“The attack on Pearl Harbor was not the first blow dealt my country,” he wrote. “The first one came two months earlier when Brigadier-General Lewis B. Hershey, head of the Select Service System, announced that of the first 2 million young men who walked up to selective-service and Army board doctors, 900,000 walked away rejected . . . physically deficient. Forty-five percent unfit for military service because of disease or defect!

“. . . For years we had been taken false assurance from the sinking death rate and lengthening life span—failing to see that what counts is not how long you live, but how well. Now we’re beginning to see that our own health record must be even poorer.

“. . . I’m in the sporting-goods business. I live among athletes. But bald-headed barbers sell gallons of hair tonic by telling their customers what they themselves discovered too late. Before it’s too late, may I pass along to you what a man in the business of making others physically fit has learned from close association with hundreds of superior athletes?

“That precious thing an athlete calls ‘tone.’ How does he keep it? By constant practice at his sport, of course. But here are other constituents: he watches his diet, knows how to relax, watches his posture, breathes right, and has poise to spare. . . . He has conditioned himself against distractions.

“That, most certainly, is the job of the businessman . . . if he’s to ward of ‘civilian shell shock.’ The last ten years of strain have taken their toll, and now with a more serious crisis on us we are compelled by elemental wisdom to appraise our individual fitness—and with a doctor’s help. If we don’t, we’ll have a horrifying number of casualties who never heard a gun fired. Don’t let that happen to you.”

Icely died in 1950 after surgery to repair a blood clot. He was 65.

“In so many activities he sacrificed his personal convenience and comfort to contribute to the general advancement of the industry in which he was engaged,” Golfdom magazine wrote in Icely’s obit. “. . . L. B. Icely probably would have been around now if he hadn’t worked so hard for all of us in his life-long campaign of preaching the gospel of sports as a counter-balance for the strains of high-pressure American life. But he liked that strenuous program and glorified in building up a big business from a tennis string start. So he lived every minute of a crowded life of achievement.”

Still a Chicago Institution

Three years before Icely’s death, Wilson Sporting Goods’ main plant in Chicago moved its operations to Tennessee, essentially ending Chicago’s role as the company’s manufacturing hub. The business end of things, however, never strayed too far from its origins.

By the company’s 50th anniversary in the mid ‘60s, there were 15 major domestic plants across the country and three international factories, with 27 sales divisions. The new corporate headquarters was located in suburban River Grove, IL. Those offices had opened in 1957, a year before Thomas Wilson’s death at the ripe old age of 90.

Over the course of a half century, Wilson Sporting Goods had fully outgrown its connection to the fading meatpacking business of Wilson & Co., and by 1967, it gained its first new affiliations—first as a subsidiary of Dallas’s Ling-Temco-Vaught, then as a wing of PepsiCo in 1970.

As many of their early 20th century contemporaries fell into obscurity, Wilson remained entrenched in the increasingly big-money landscape of pro sports, making the official basketball of the NBA, the official football of the NFL, and uniforms for most of the teams in Major League Baseball. Wilson tennis balls were used for play at the U.S. Open from the ‘70s into the 21st century, and a certain Wilson volleyball even became a film star alongside Tom Hanks in the year 2000.

As many of their early 20th century contemporaries fell into obscurity, Wilson remained entrenched in the increasingly big-money landscape of pro sports, making the official basketball of the NBA, the official football of the NFL, and uniforms for most of the teams in Major League Baseball. Wilson tennis balls were used for play at the U.S. Open from the ‘70s into the 21st century, and a certain Wilson volleyball even became a film star alongside Tom Hanks in the year 2000.

Wilson Sporting Goods is currently a subsidiary of a Finnish company, Amer Sports. But after a long stretch in River Grove, the corporate headquarters has continued to inch closer back to the ground it started on. In 1992, the offices relocated to a Rosemont high-rise near O’Hare Airport, where they’d remain for 25 years. As of 2017, however, those 400+ jobs are set to move into the Prudential Plaza downtown, overlooking Millennium Park.

Wilson’s factories have skipped town, but the company—after more than a century—maintains a highly visible presence.

“To what do you chiefly attribute your wonderful success?” Thomas Wilson was asked way back in 1917, still unaware of just how massive and long-lasting that success would prove to be.

“I am no wonder,” he replied. “I am no brainier or wiser than any number of other people. My whole success is traceable to the fact that I have enjoyed my work and have given to it the best in me. No job ever was too big for me to tackle. That is the foundation of success nine times out of ten— having confidence in yourself and applying yourself with all your might to your work.

“I am no wonder,” he replied. “I am no brainier or wiser than any number of other people. My whole success is traceable to the fact that I have enjoyed my work and have given to it the best in me. No job ever was too big for me to tackle. That is the foundation of success nine times out of ten— having confidence in yourself and applying yourself with all your might to your work.

“Too many men try to travel on a reputation. They stand upon their past achievements rather than daily press on toward further achievements. You cannot stake your future on the past, but on the present. A fellow must throw his whole energy into everything he undertakes and feel keenly that on this one thing, whatever it be he is doing, depends his whole future.”

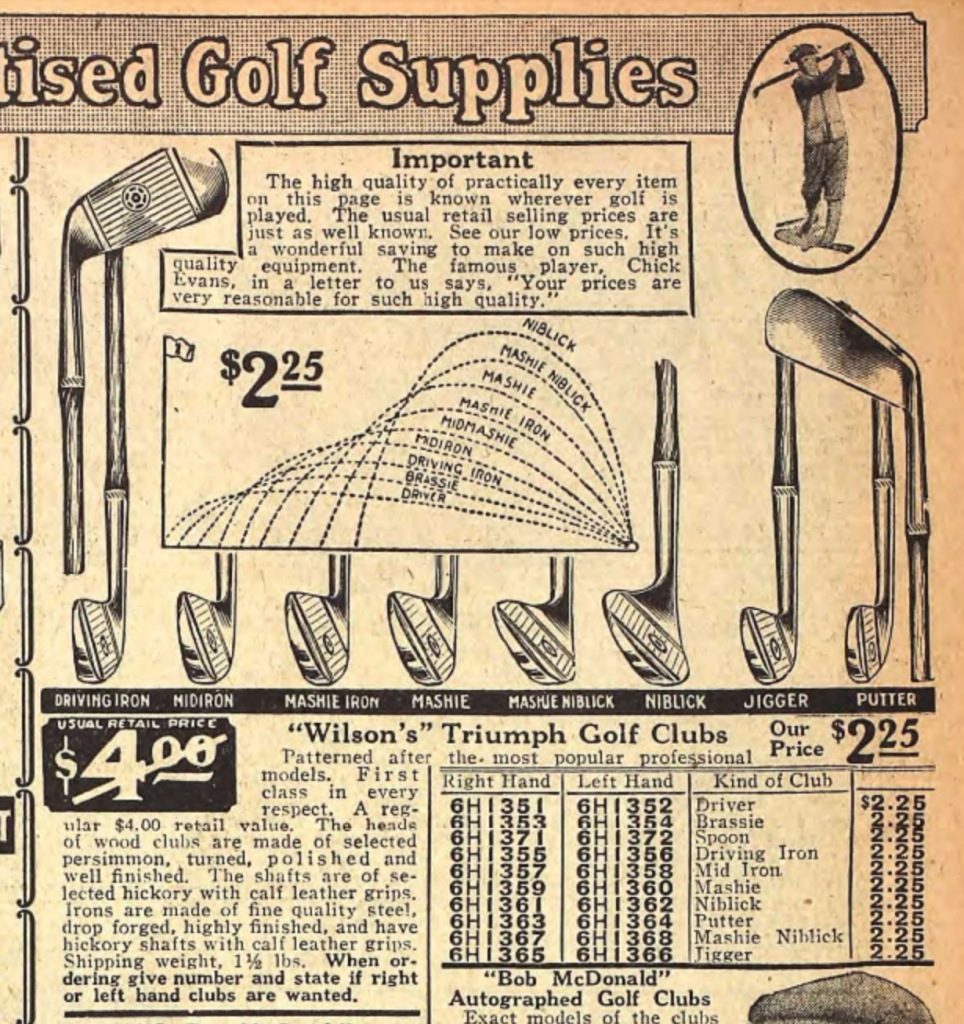

[Listing for Wilson “Triumph” Golf Clubs in Sears Roebuck catalog, 1919]

[Listing for Wilson “Triumph” Golf Clubs in Sears Roebuck catalog, 1919]

[Wilson golf ad, 1949]

[Wilson golf ad, 1949]

[Wilson golf ad featuring Patty Berg, 1956. Wilson played a key role in prpmoting women’s golf and the creation of the LPGA]

[Wilson golf ad featuring Patty Berg, 1956. Wilson played a key role in prpmoting women’s golf and the creation of the LPGA]

Sources:

–“Up On Your Toes Now, Gentlemen,” by Lawrence B. Icely, The Rotarian, July 1942

–“The Downfall of Wilson Golf,” by George Shackelford, Golfweek

–“Sporting Goods Maker’s Strings Go Long Way Back,” Chicago Tribune, Jan 4, 1964

–“Mary Ann Sarazen: Dad Didn’t Invent the Sand Wedge, but He Modernized It,” Golf.com

–“L. B. Icely, Golf Leader, Dies,” Golfdom magazine, September 1950

–“Wilson Sporting Goods Announces Move to Chicago’s One Prudential Plaza,” by Jay Koziarz, Curbed Chicago

—Chicago’s Accomplishments and Leaders, by Glenn A. Bishop and Paul T. Gilbert, 1932

–“Making Good at the Table of the American Family” by F. Burnham McLeary in The World’s Work, November 1917

—Men Who Are Making America, by B. C. Forbes, 1917

–“The Long, Storied History Behind the Footballs of the NFL,” Chicago Tribune, Jan 27, 2017

–“Sporting Goods Capital,” Chicagology.com

—Fort Dearborn Magazine, Midsummer 1921

–“Say It Ain’t So,” HaulsofShame.com, 2010

—Antique Golf Collectibles: A Price and Reference Guide, by Chuck Furjanic

Archived Reader Comments:

“Wonderful presentation of history of Wilson. Thank you” —Richard Marks, 2019

“Excellent article. It gives me a wonderful feeling that someone else takes the time to study into Wilson Sporting Goods history as I do, and writes a page about it. Also, the pictures of catalogs and advertisements are fantastic. I’m glad to see you posting the catalogs I uploaded are being put to good use! Keep up the good work!” —Jared Wilson, 2018

“My Dad worked for Wilson Sporting Goods, and had since he was 16 years old. In December, 1928, when he was 26, He lost an eye. This is his official notice of the accident:

Between the main building and the office building there is a court way. In this court there has been a practice golf net for the purpose of testing clubs and golf balls. Inasmuch as I have packers working for me, my superintendent, Mr. Hennock, instructed me to send my men out to the court way to take down the net.

At about 11 o’clock or between 11 and 11:30 on December 8, 1928, I became unusually busy in the shipping room and Mr. Hennock advised me to recall my men to the shipping room and pack the orders. I went out into the court to call the men and became interested in a conversation with a Mr. Walter Jacobson, a fellow employee from the golf ball factory, who was testing out golf balls. The conversation consisted of a discussion with reference to a ball which he was using. I dropped the ball from my hand and turned around to re-enter the factory, intending to go to the shipping room, and as I started to enter the building on a wooden walk which connects the office building with the factory building, one of the shipping room employees picked up a golf club and as he was walking back to the shipping room, was swinging it back and forth in a manner similar to practicing shooting. I walked behind him and thought he was far enough out of the reach of the swing. Taking a few steps further towards the factory, my fellow employee turned around and without warning swung the club from the opposite direction and I was struck on the upper part of the stroke in the left eye.

I was not rendered unconscious but immediately lost the sight of my eye and immediately went to the shipping room office, but was not able to find Mr. Hennock, so one of the boys in the shipping room called him on the auto-call and informed him a serious accident had occurred. Mr. Hennock immediately came to the shipping room and was informed of the accident. I was driven immediately to the hospital by one of the employees. The name of the employee that swung the golf club is Barney Pocelowski.” —Carol Jarentowski Larson

I have been collecting vintage golf clubs for over 40 years, and proudly display a Thomas E. Wilson WALKER CUP #1 Driving Iron on my wall. It has 6 lines of semi-circular scoring on the face (which is a real eye-catcher), and retains its original leather wrapped grip. It is marked “Spade” on the toe and has an image of a Spade stamped toward the heel. The shaft bears no marks.

I suspect that the club was manufactured in 1922 (the first year of the Walker Cup competition) or perhaps a year or so later. Any confirmation of this would be greatly appreciated.

Hello, I have my dad’s Arnold Palmer AP 33 left-handed putter. I’ve already checked on the Internet and can’t find any information when this club started manufacture. My guess is sometime in the 1960s by Wilson?

I’m not sure.

Thanks,

Bob

What year was the wilson redpush bull kart collapsible produced.

Magnifico artículo y presentación, soy un fiel fan de la marca Wilson y practico tenis desde pequeño. No habia encontrado anteriormente un artículo tan completo como éste acerca de la historia y los inicios de la marca, como de su creador y su equipo de trabajo.

Yo, feliz de tener mis tesoros que son 2 raquetas Wilson pro staff 85, bolso y 2 raquetas pro staff 97 con las que juego actualmente.

Gracias por la oportunidad de conocer esta preciosa historia !!!

Saludos desde Chile

Cristian

I am refurbishing a very old split bamboo fishing rod that has a Thos E. Wilson and Co. logo on the reel seat.

I am trying to get information on the year that the reel seat may have been manufactured and any other information about the line of fishing equipment that was used around that time.

Thank, you

Ed Nickerson

I would like to know where I can purchase any Wilson Men’s 1950’s/1960’s Nylon Button-Flapped pocket Golf/Tennis Pullover Windbreakers with the wool cuffs around the neck, waist and end of sleeves.

Well, I have not read one word about Thomas E. Wilson fishing rods, Chicago, Ill.

I still have two bamboo fly rods properly stamped on the chrome plated reel seat.

But not one word anywhere about what date this began, and who was involved, and where the rods were manufactured.

I’m very curious as to why this information is not part of the Wilson published history?

Thanks, Mike

Hi Mike. Wilson produced thousands of products over the course of the 20th century. This article is merely a synopsis of the company’s history in Chicago, and is not a completist guide to their full catalog of output. We are not affiliated with Wilson so we are limited to the information available through research. –Made In Chicago Museum

Dear Wilson Sporting Goods: I have a set of 1957 Wilson Staff Persimmon Woods in “museum” condition. These woods have virtually “never been hit”! I am liquidating my golf club collection and these deserve to be in your headquarters! Please contact me if interested and I will send photographs.

Sincerely, Jerry Wisz, PGA (Life Member Retired)

So Calif PGA Hall of Fame

Golf Professional of the Year

I have a wooden club with a natural wood face…identified as THOMAS WILSON & CO. I’m assuming it was built around 1923. Am I correct?

I have a Ted Ray seventy two wooden brassie with a wooden shaft and wooden head with a metal plate on the bottom of the club head. Did Aim Rite, Wilson sporting goods make this club, if so, could you please tell me when it was made. It measures 44 and 3/4 in long and the club head measures, 2 and 3/4 in wide. Any help would be appreciated.

I am the proud owner of a pair of vintage Wilson mittens, no. 125.

They are brown in color and were possibly made for use in skiing.

They, of course, have the Wilson logo and were made in USA.

Any idea when they were made?

i have a thos>e>wilson&co “onwenesia” tennis racket at perth aust would like to know what year this is thanks henry michael

I own a Alex Smith Westchester Biltmore 5 Mashie. Wilson Chromium with Red wrapped leather grip. Reg. No. 2755. Also has a circle and Diamond shape on back of club. Face has a 5 point star

inside a circle. Can you give approx. date it was manufactured?

I have a Wilson K-18 wooden longbow. Was wondering about Wilson’s history in the Archery world. What years? Was the archery equipment produced by them or was it made by somebody else and just branded as Wilson?

I am an antique club restorer and collector. I have many ,Wilsonian, Aim Right, and Cup Defender clubs and a Jock Hutchison, Medalist mashie, made by Thomas E Wilson & co.

Can you supply me with manufacture dates for these clubs?

I am the proud owner of a set of “AIM RITE” golf clubs that has a forge hammer engraved on the back and an jagged etcher=d the t look like WES over the words MATCHED MODELS the face has a circle with the words Aim Rite with a five pointed star. Is it the earliest model?

Hello,

I have a brand new, never hit set of Sam Snead golf clubs. Three woods and 8 irons. Also the bag and cart were included. No putter unfortunately I proudly display this find in my office and they are an endless conversation piece. I would love to learn more about the specific manufacturing date if you could help me with some history.

Thank you,

Kevin Johanson