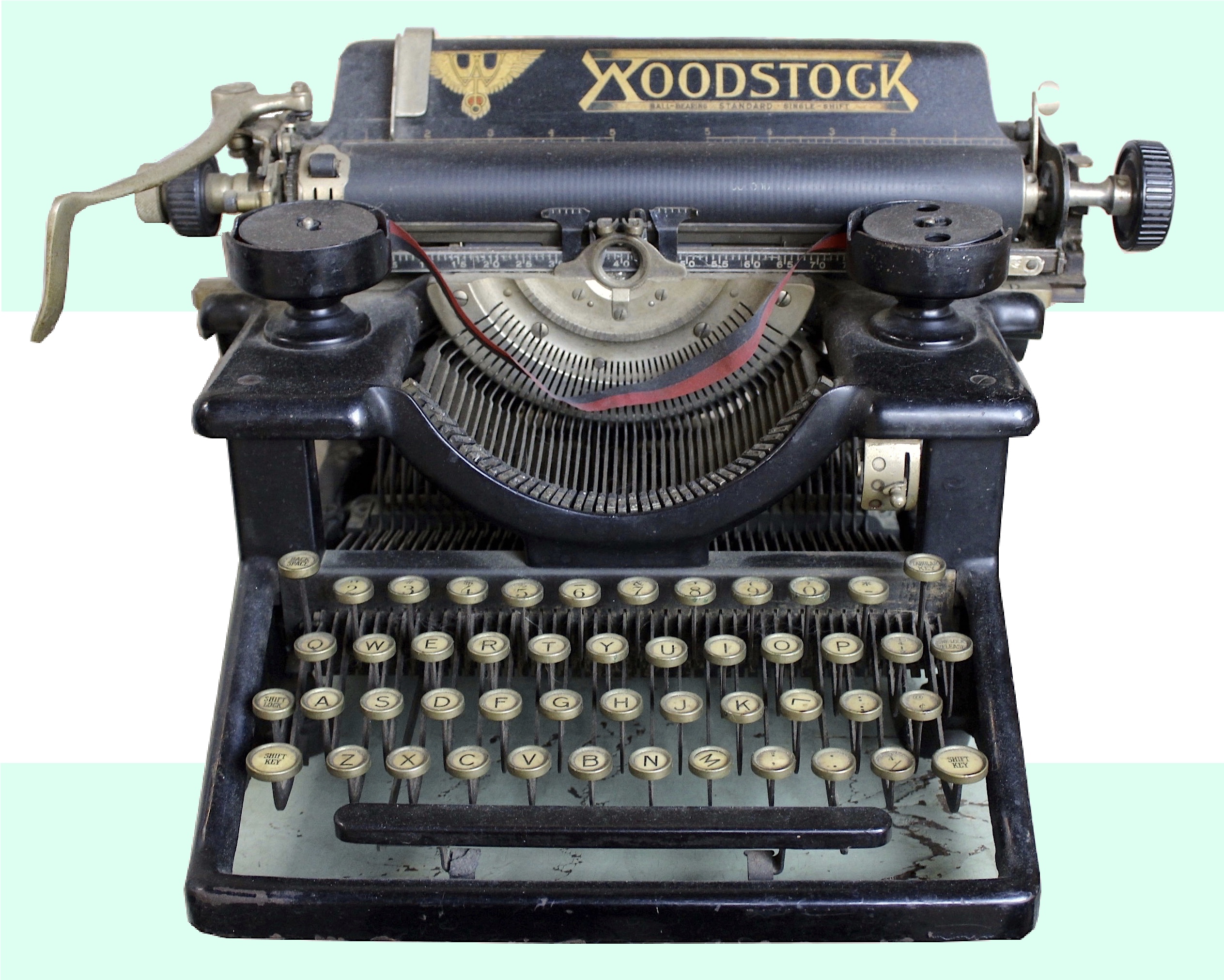

Museum Artifact: Woodstock Standard Typewriter, Model No. 5, 1922

Made By: Woodstock Typewriter Company, 300 N. Seminary Ave., Woodstock, IL (Offices at 35 N Dearborn St, Chicago)

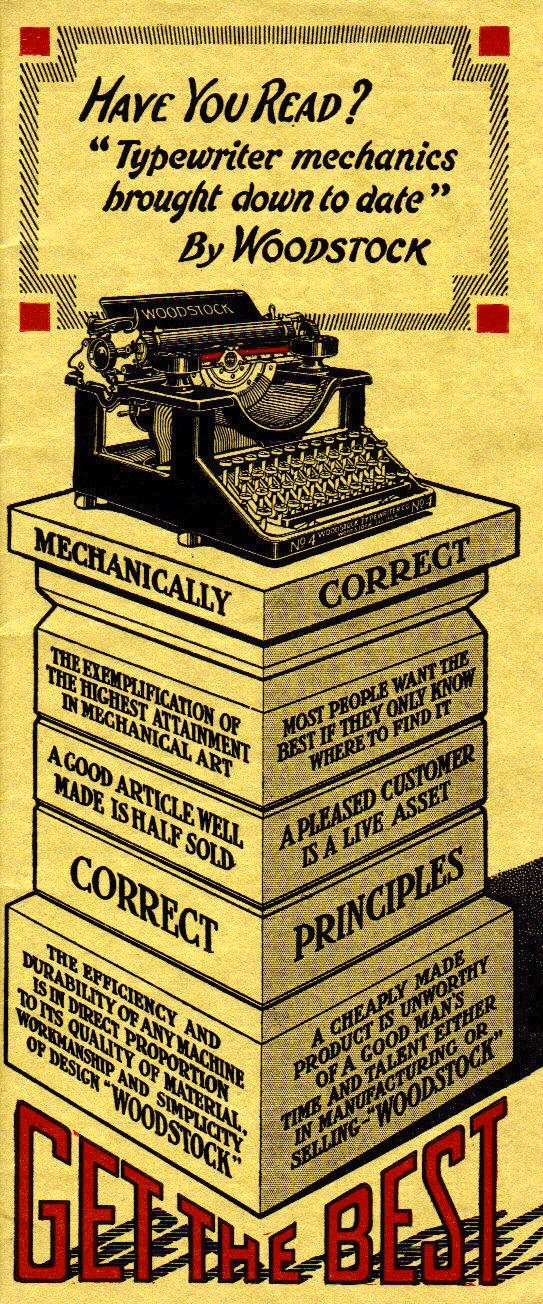

“The record of the Woodstock Typewriter stands out conspicuously as one of the great achievements in typewriter history. Probably no writing machine has stepped into prominence with less ado or been received with such universal favor.” —Woodstock Typewriter Co. advertisement, 1921

Woodstock, Illinois, is a sleepy, romantic little town of 25,000, accessible by the Union Pacific Northwest Metra rail line from downtown Chicago—about an hour and a half journey. If you go there, you might recognize it as the stand-in for Punxsutawney in the movie Groundhog Day (there’s even a plaque with a shoe imprint near the town square that says, “Bill Murray Stepped Here”). There’s also a sculpture of former local boy Orson Welles, and a museum dedicated to cartoonist Chester Gould, who created many of his famous Dick Tracy comic strips while living there.

Woodstock, Illinois, is a sleepy, romantic little town of 25,000, accessible by the Union Pacific Northwest Metra rail line from downtown Chicago—about an hour and a half journey. If you go there, you might recognize it as the stand-in for Punxsutawney in the movie Groundhog Day (there’s even a plaque with a shoe imprint near the town square that says, “Bill Murray Stepped Here”). There’s also a sculpture of former local boy Orson Welles, and a museum dedicated to cartoonist Chester Gould, who created many of his famous Dick Tracy comic strips while living there.

A bit less memorialized these days, however, is Woodstock’s former standing as the Typewriter Capital of the World.

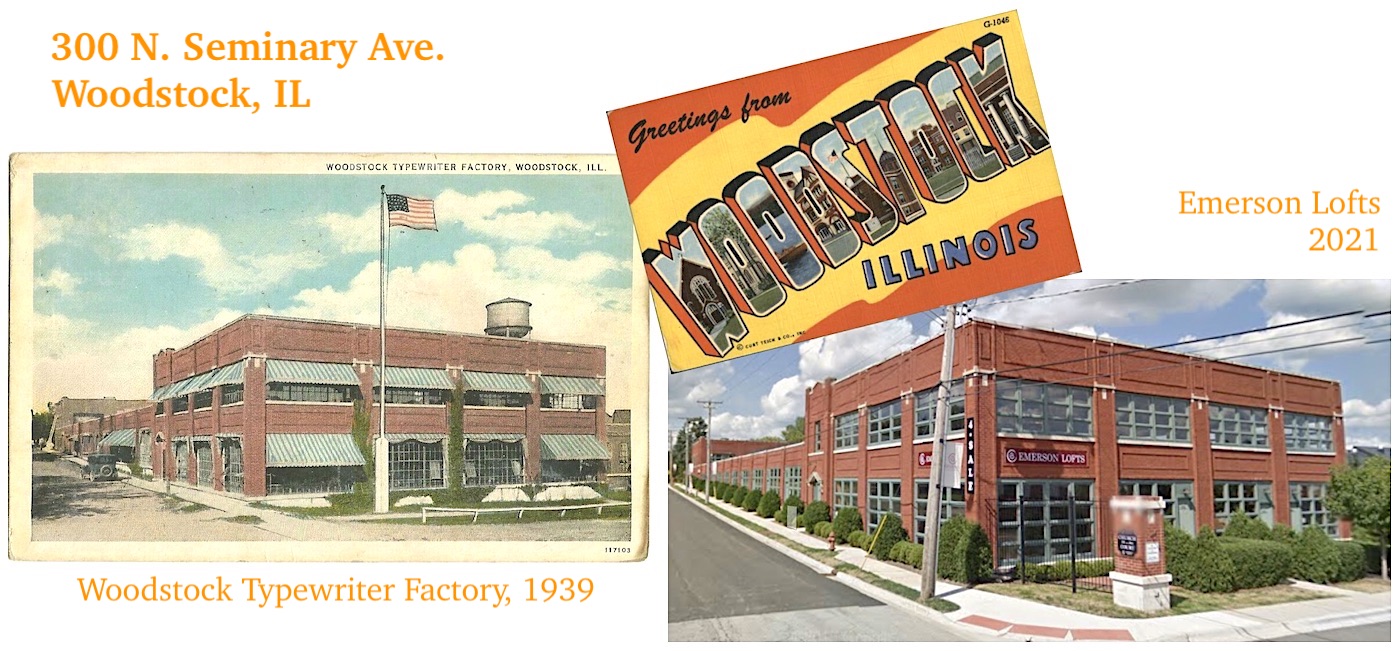

In 1910, Woodstock was already well established on the typographical map as the home of the successful Oliver Typewriter Company, which set up its main factory there in 1896. Now, the town had successfully coaxed another manufacturer—the fledgling Emerson Typewriter Co.—to move its operations from Momence, IL, up to a brand new facility at 300 N. Seminary Ave. Emerson would later re-launch as the Woodstock Typewriter Company, but it would take the last-minute financial backing of a Chicago retail legend—and the ingenuity of his equally famous business partner—to make it happen.

History of the Woodstock Typewriter Company, Part I: Sears & Roebuck to the Rescue

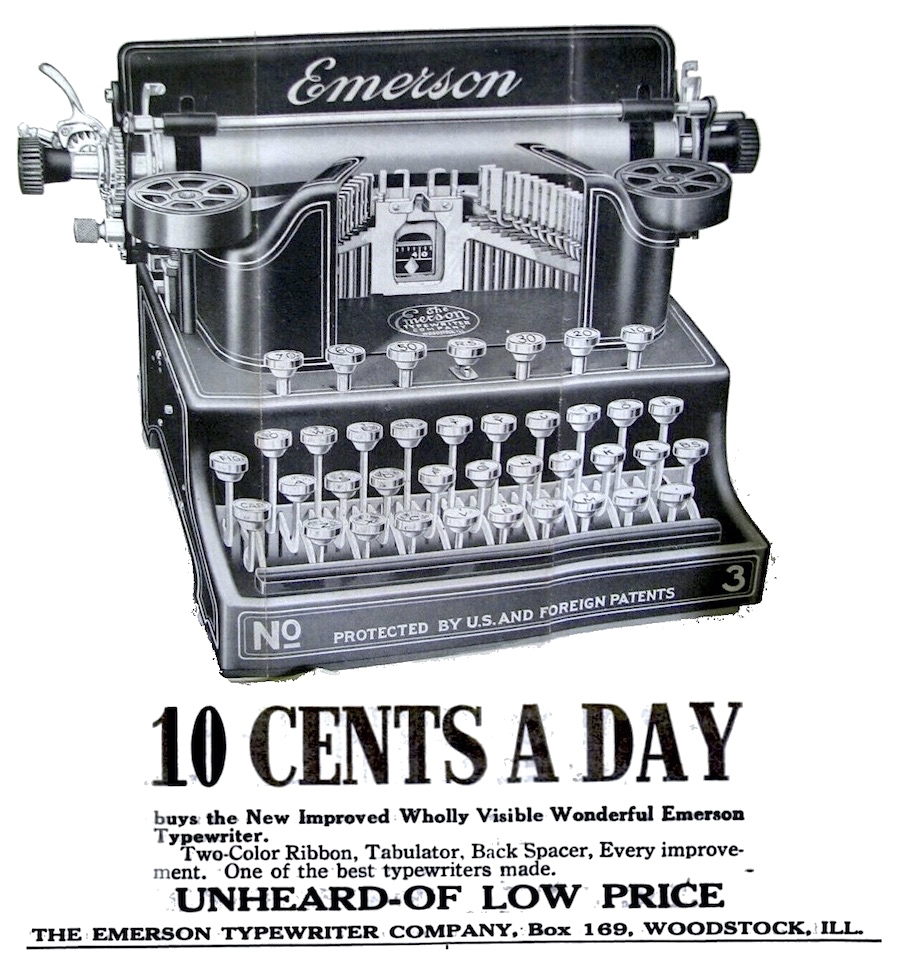

The Emerson Typewriter Company was originally established in Kittery, Maine, in 1907, but headed west a year later, establishing a small plant in Momence, IL, about 50 miles due south of Chicago. The company had generated some buzz around the release of its 1909 model, designed by noted typewriter architect Richard W. Uhlig. It was supposedly the first and only “Standard and Visible Typewriter” selling at a budget price—a $50 machine “that compares in every particular with all the so-called $100 machines.”

Unfortunately, both the production and sales figures of the new machine fell short of everyone’s hopes, and even before work was complete on the company’s new $40,000 factory in Woodstock, the Emerson stock holders got collectively spooked and jumped ship. Barring the miraculous arrival of a savior investor, the whole enterprise could have tanked right then and there.

Unfortunately, both the production and sales figures of the new machine fell short of everyone’s hopes, and even before work was complete on the company’s new $40,000 factory in Woodstock, the Emerson stock holders got collectively spooked and jumped ship. Barring the miraculous arrival of a savior investor, the whole enterprise could have tanked right then and there.

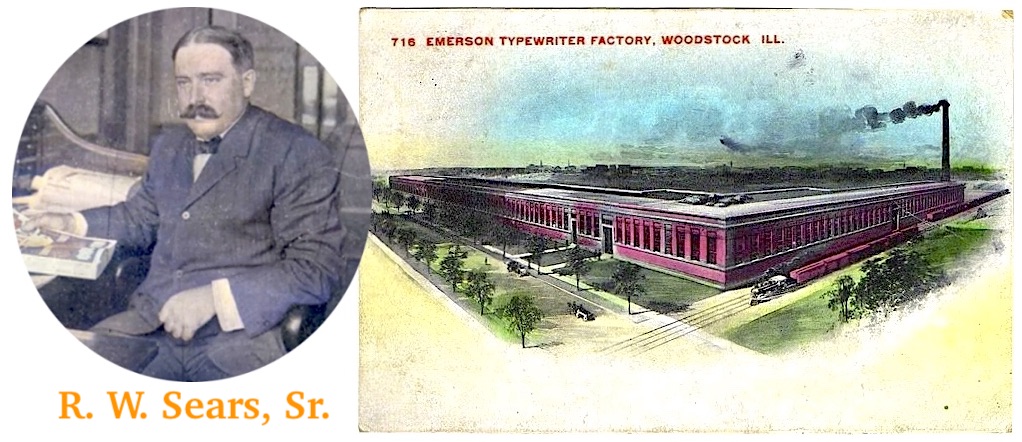

Enter Richard W. Sears, famed founder of America’s leading wholesale mail order house, Sears, Roebuck & Co.

In November of 1910, newspapers reported that the 47 year-old tycoon had, indeed, saved the proverbial day for the folks of Woodstock, buying the Emerson Typewriter Co. and its factory outright, with the intention of moving things forward “full steam ahead.”

“Woodstock people feel that sufficient capital is now back of the enterprise to place it on a firm financial foundation and enable the company to put the Emerson machine on the market in a manner to bring satisfactory returns,” the Richmond Gazette reported.

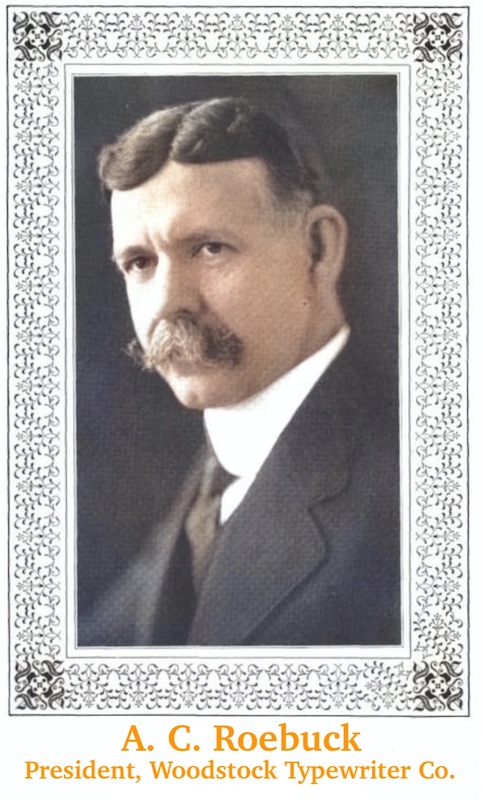

Mr. Sears, who was buying up similar manufacturing prospects with aplomb, had no intention of managing the daily affairs of the typewriter business, but to the surprise of many, his former righthand man—no less than Alvah C. Roebuck himself—was eager to get involved on the ground floor.

By 1912, the 48 year-old Roebuck was not only a major shareholder in the Emerson Typewriter Company; he also set up a residence in Woodstock and promptly replaced Frank L. Wilder as the company’s president.

As had been the case throughout his career, Roebuck—a former watchmaker from Indiana—saw himself as an engineer first and a businessman second. As such, despite having no prior experience building typewriters, he entered into this new undertaking with one goal: to design and patent a machine of his own, up to the highest standard, but within the budget of the average American.

As had been the case throughout his career, Roebuck—a former watchmaker from Indiana—saw himself as an engineer first and a businessman second. As such, despite having no prior experience building typewriters, he entered into this new undertaking with one goal: to design and patent a machine of his own, up to the highest standard, but within the budget of the average American.

“Unhampered by precedents or prejudices,” the trade magazine Office Appliances later reported, Roebuck took on the project with an open mind and with “characteristic thoroughness and foresight.”

Roebuck also started building the company in his own image. “He makes a consistent effort to secure the services of men of good character,” wrote Office Appliances, “and says he prefers a person who has natural ability and is somewhat lacking in experience, rather than a person with more experience and less ability and character. By nature Mr. Roebuck is democratic and popular among his employees.”

So popular was the new boss, in fact, that the Emerson stockholders voted to rename the business the “Roebuck Typewriter Company” in 1914. After just a few months, though, the humble Roebuck encouraged a more community-oriented rebrand, and thus, the Woodstock Typewriter Company was born. The change went into effect in September of 1914, several weeks before the untimely death of Richard Sears put the fate of the company all the more in the hands of Alvah Roebuck.

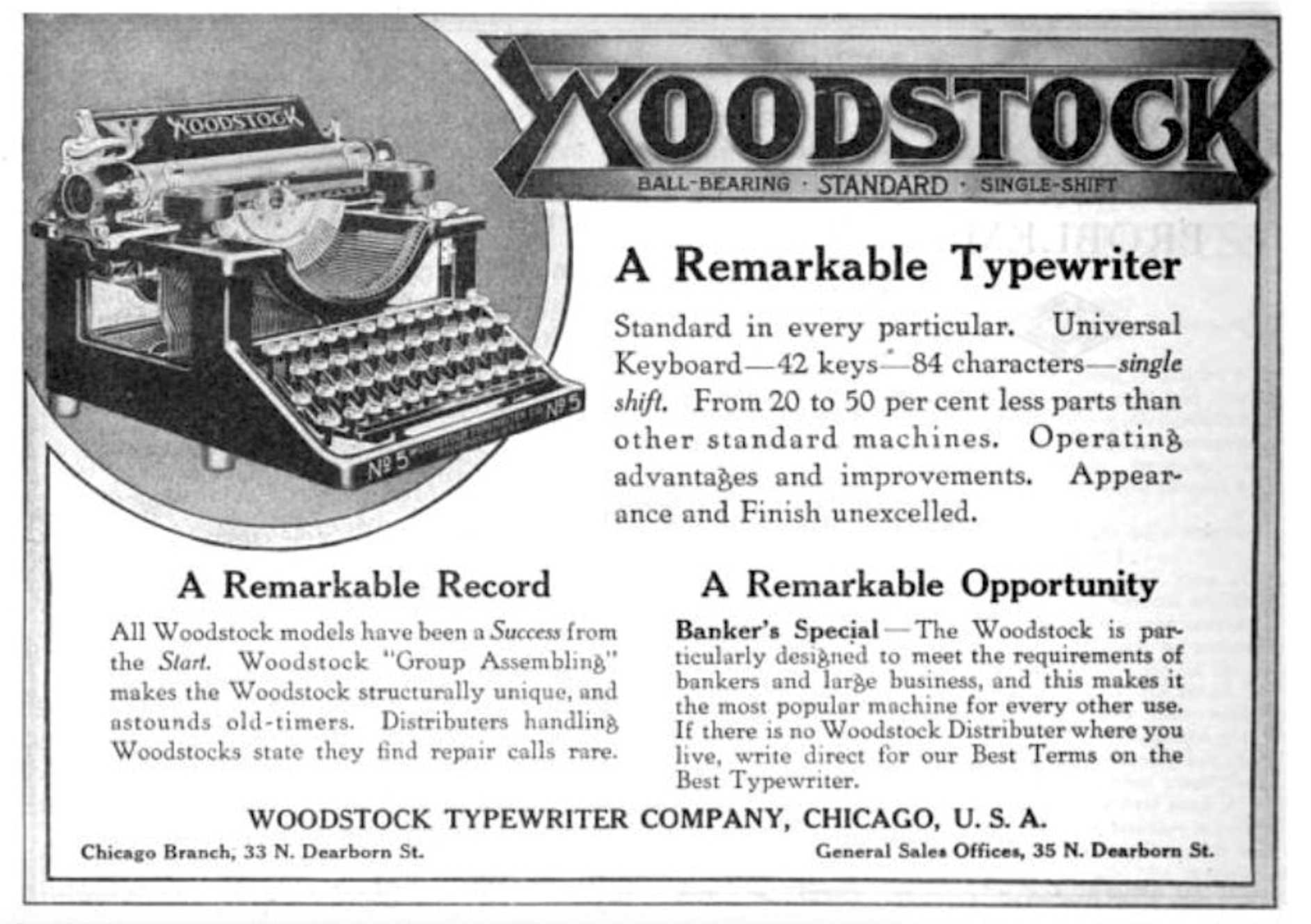

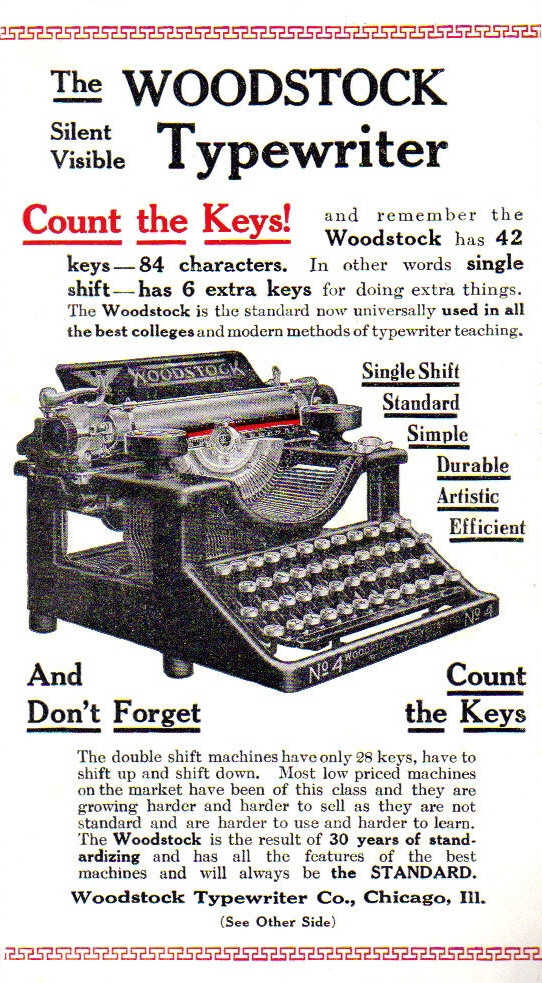

[1915 advertisement for the Woodstock Visible Silent Typewriter]

Fortunately, early reviews of Roebuck’s machine suggested he was more than up to the task.

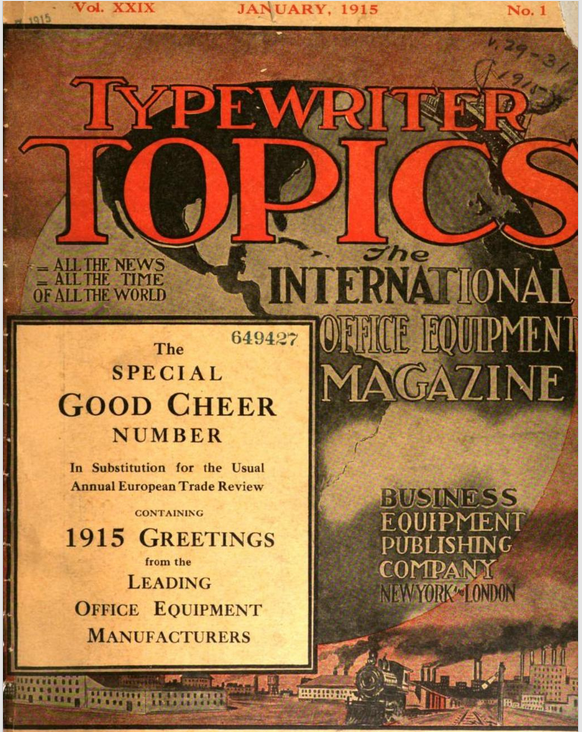

In 1915, the publication Typewriter Topics was particularly effusive in its praise:

“Quietly, but with energy characteristic of the man, A.C. Roebuck, chief in the work of mechanical development in no less capacity than as inventor, and in executive charge of the company as its president, has created in a surprisingly short length of time a writing machine of the standard variety that for simplicity and effectiveness in performance ranks far above the usual result from a first effort. A most exhaustive test of a considerable number of the machines, covering a period of several months, however, has given a gratifying degree of assurance that this new product is a success in every respect.

“The appearance of new typewriters on the market is of such frequent occurrence that something out of the ordinary is now required to attract more than passing attention. And we believe that our readers will agree with us when we say that the subject of this article, namely the New Woodstock Typewriter, manufactured by the Woodstock Typewriter Co., of Woodstock, Ill., U.S.A., seems to be in a class that at first sight attracts and holds your attention.”

Where the Emerson machine had stumbled out of the gates, the Woodstock—backed by the wisdom and influence of Sears and Roebuck—immediately gained ground in the highly competitive industry, stealing some market share from their next-door neighbors at Oliver, among others.

[Workers outside the Woodstock Typewriter Company factory, circa 1915-1920. As with the workers at the Oliver Typewriter plant, Woodstock employees had their own baseball team, band, and other social activities tied into the community.]

II. Model Number 5

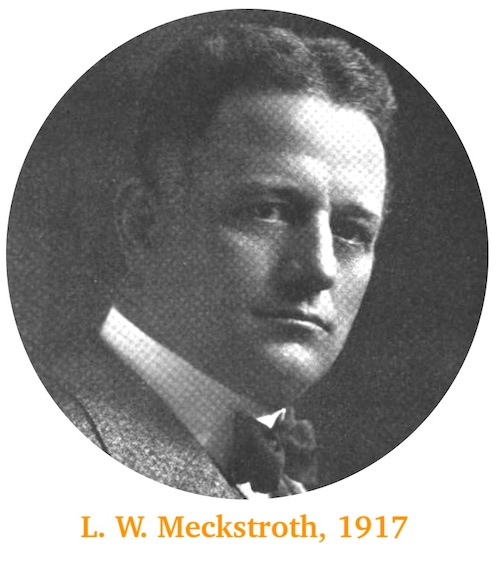

True to form, A. C. Roebuck wasn’t as interested in hanging around the boardroom once the innovation stage was largely complete. Though he remained a chief shareholder of the typewriter business (along with the widow of Richard Sears)—Roebuck and his family left Woodstock for Crystal Lake in 1916. A new company president was elected the following year in the form of Louis W. Meckstroth—a “man with a clear, true vision and broad ideas,” according to Typewriter Topics.

In a baptism of fire, Meckstroth was tasked with guiding the Woodstock Typewriter Co. through the uncertainty of World War I. But he and his new sales manager Vorley Wright (a former member of the Oliver team) seemed to have some momentum on their side.

“It is stated that in spite of the war, the excellent new Woodstock machine is already being handled in 48 foreign countries under 13 foreign languages,” Typewriter Topics reported. “This is an enviable record and speaks in the strongest terms for the machine itself as well as the management.”

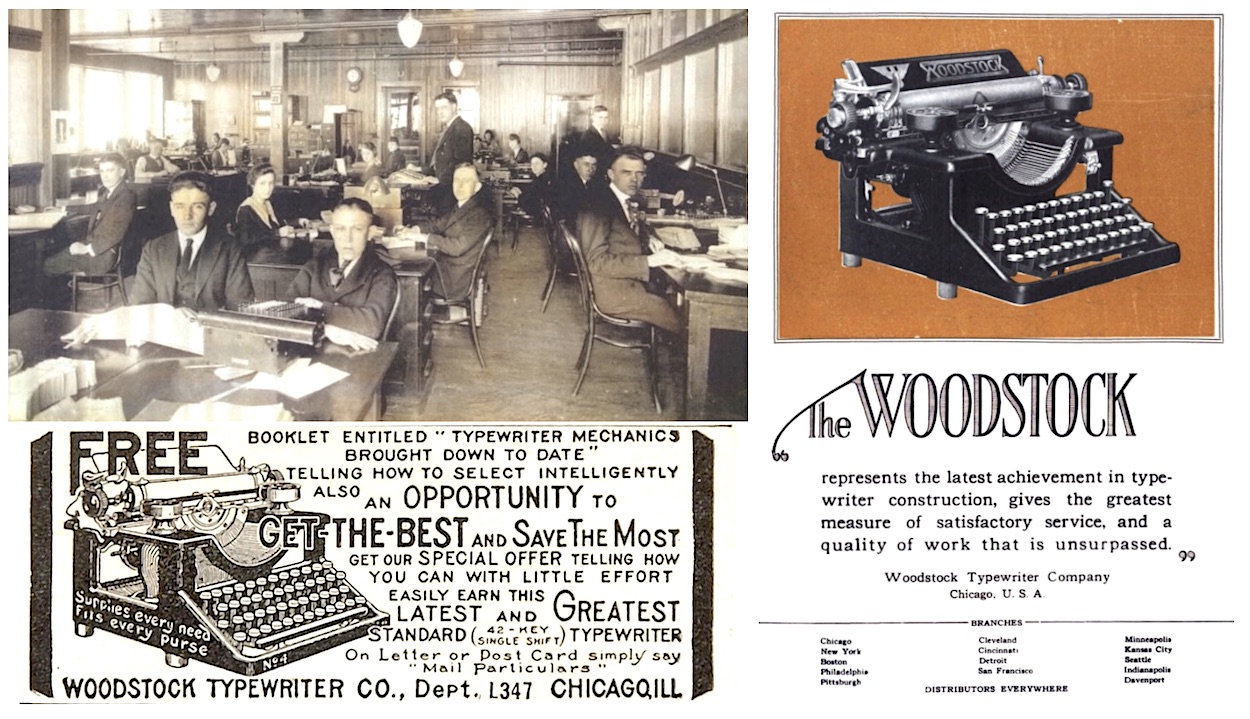

In the midst of the war, to help better manage this growing business, the Woodstock Typewriter Co. established new offices in downtown Chicago, at 35 North Dearborn. Here, Meckstroth and Wright worked with an often overwhelmed sales and management team to stay on top of the deluge of orders and correspondence coming from a now global clientele.

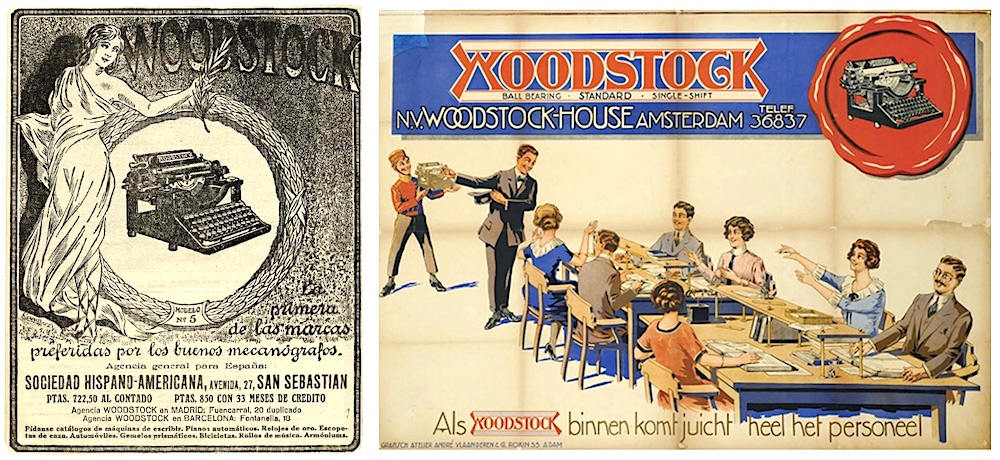

[During and after WWI, the Woodstock Model No. 5 was widely sold and promoted in nearly 50 countries, as evidenced by the ads above from Spain (left) and the Netherlands.]

There were various marketing strategies put in place on the home continent, too. Rather than pricing the machine at $50 to undercut the competition, for example, Woodstock typewriters generally sold for the same industry standard of $100. Buyers could get a rebate off their purchase of up to $32, though, if they promoted the machine to their friends and neighbors, then provided testimonial proof of having done so. This gimmick not only enticed budget conscious customers, it also created thousands of extra salesmen and women.

Once the war was over, Meckstroth’s next challenge was maintaining the allegiance of his own workforce. In 1919, a six-week strike threatened production of the latest Woodstock Model No. 5, as workers pushed for reforms. Meckstroth and his cohorts settled the dispute with a wage increase and a reduced nine-hour work day, but the plant remained less than progressive in its dealings with labor unions.

[Top Left: Inside the Woodstock Typewriter offices, circa 1915-20. Bottom Left: Early ad for the Woodstock No. 4. Right: 1923 advertisement for the Model No. 5]

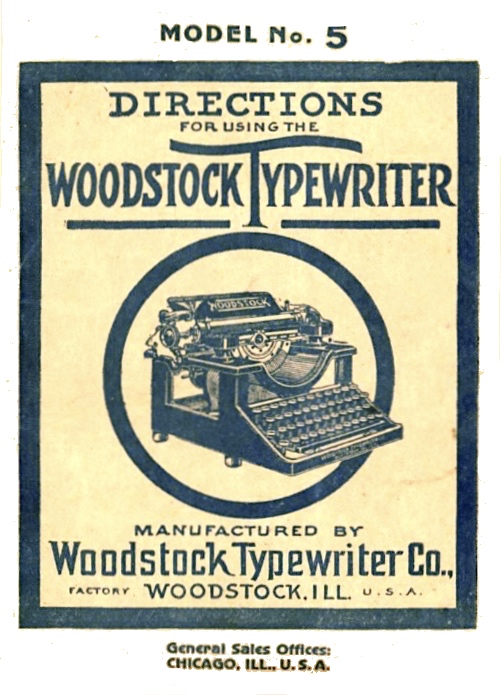

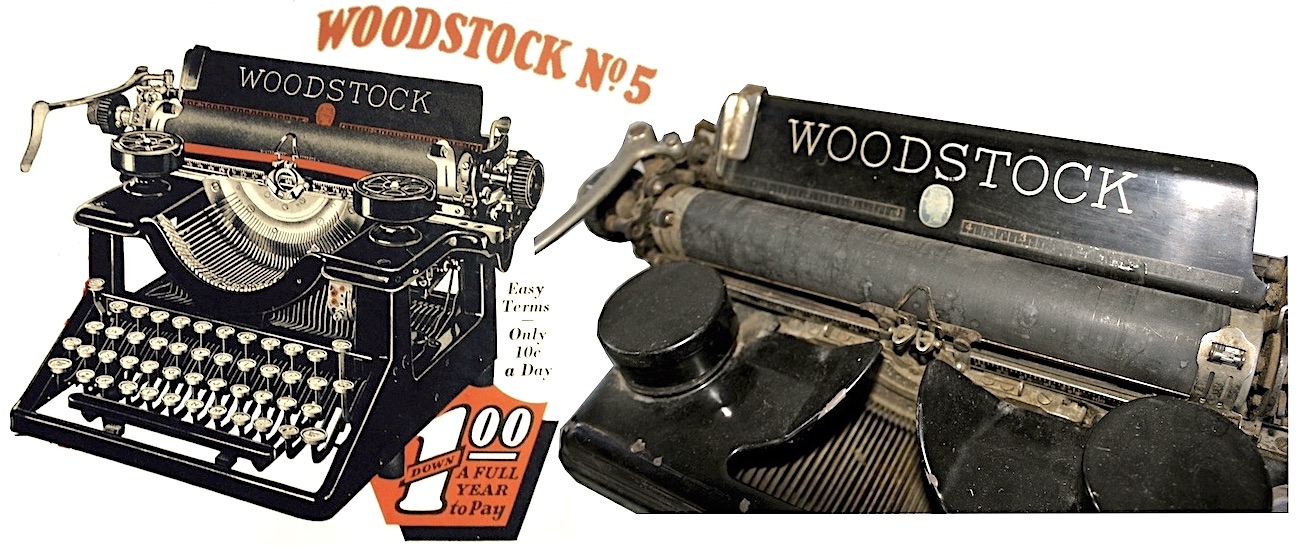

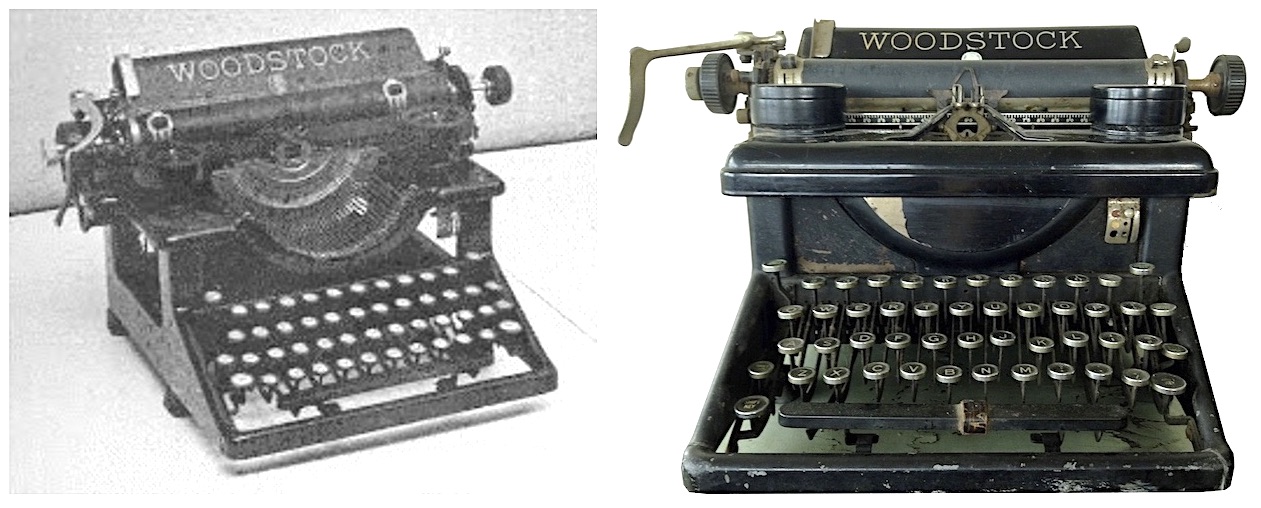

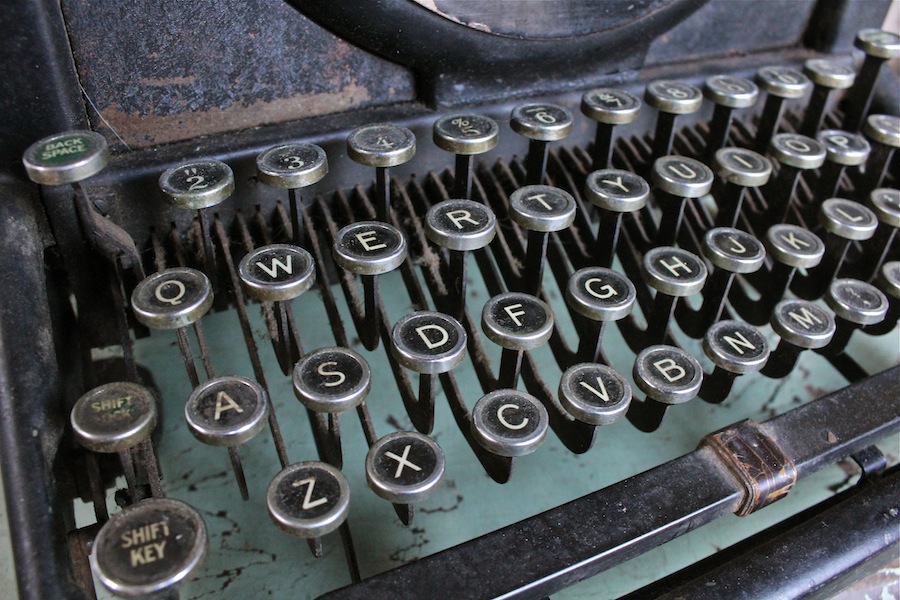

The aforementioned Woodstock No. 5—the model in our museum collection—was an ever-evolving workhorse for the company, regularly in production for over 20 years. It was touted for its quietness and ease of use. Even the machine’s official instruction manual seemed to suggest that no one would ever need to read it.

“Simplicity is of the utmost importance in any machinery,” the manual read, “and the WOODSTOCK TYPEWRITER is the simplest and has the fewest parts of any of the high grade typewriters. …The WOODSTOCK TYPEWRITER is so simple that no instructions are needed by one who has had any experience in operating a typewriter…”

“Simplicity is of the utmost importance in any machinery,” the manual read, “and the WOODSTOCK TYPEWRITER is the simplest and has the fewest parts of any of the high grade typewriters. …The WOODSTOCK TYPEWRITER is so simple that no instructions are needed by one who has had any experience in operating a typewriter…”

The fanboys at Typewriter Topics provided their own assessment of the Model No. 5 in the September 1917 issue:

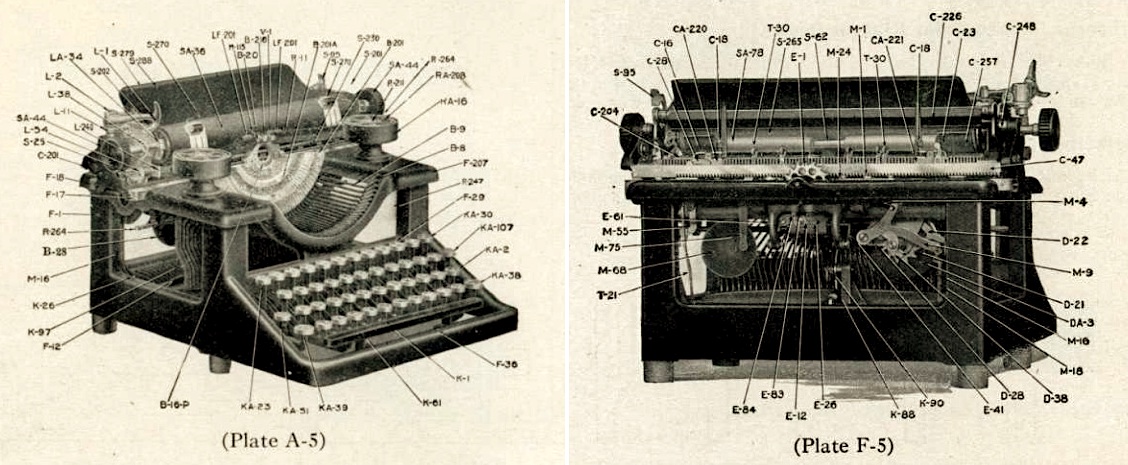

“The Model 5 Woodstock Typewriter has been in the field for less than one year, but it has proved to be the most popular model of this wonderfully successful make. It has all the essentials of a modern high grade typewriter, plus various inventions and improvements peculiar to the Woodstock. It is easy and convenient to use, and the experience with previous models of the Woodstock as well as with the No. 5 Model justifies the belief that it is the most durable and dependable typewriter ever made. With all of this it has fewer parts by about 20% than the average machine of standard design. The No. 5 Model has created a sensation both with dealers and with users wherever it has been introduced.”

The Woodstock No. 5 in our collection has a serial number of F94926, dating it to early 1922—the heyday of typewriter mania in the town of Woodstock, when half of the world’s entire typewriter production was centered here. At the time, 350 workers were employed at the 44,000 square foot Woodstock Typewriter plant, producing 55 of the finely tuned machines each day.

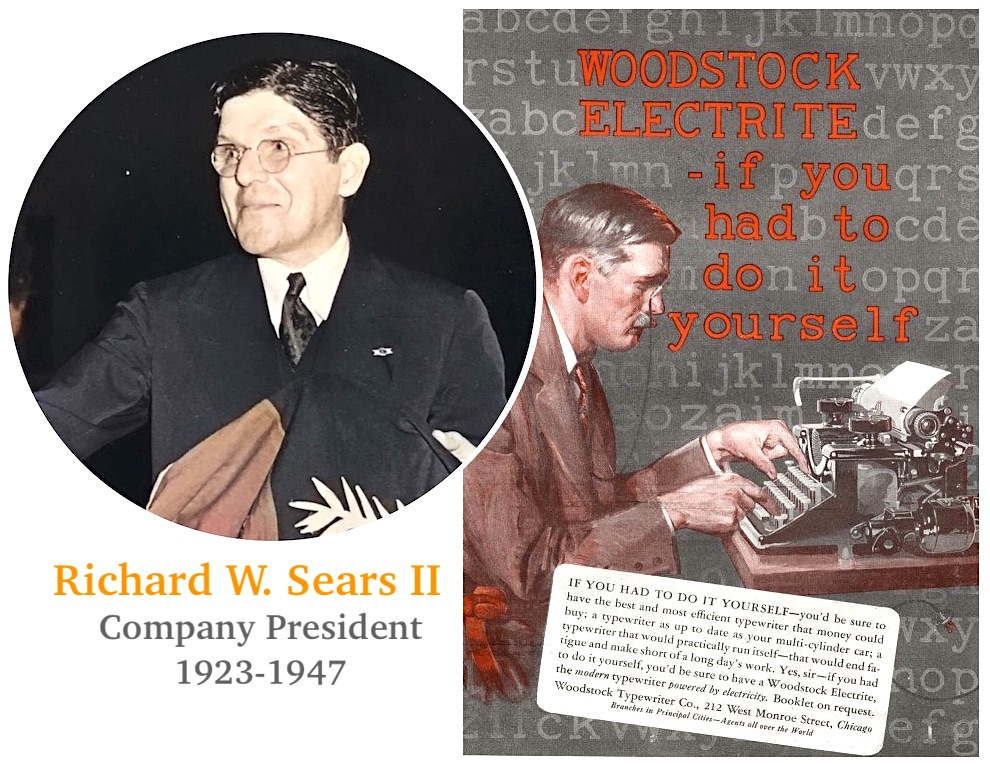

Taking notice of this steady production was a young man with a vested interest in the company’s success. Richard W. Sears II, the relatively obscure son of the great retail magnate, was just 25 years old when he took over the presidency of the Woodstock Typewriter Co. in 1923. Like his father, he never came to live in Woodstock, but he did play a similar role in helping the business overcome adversity—this time, in the aftermath of the stock market crash of 1929.

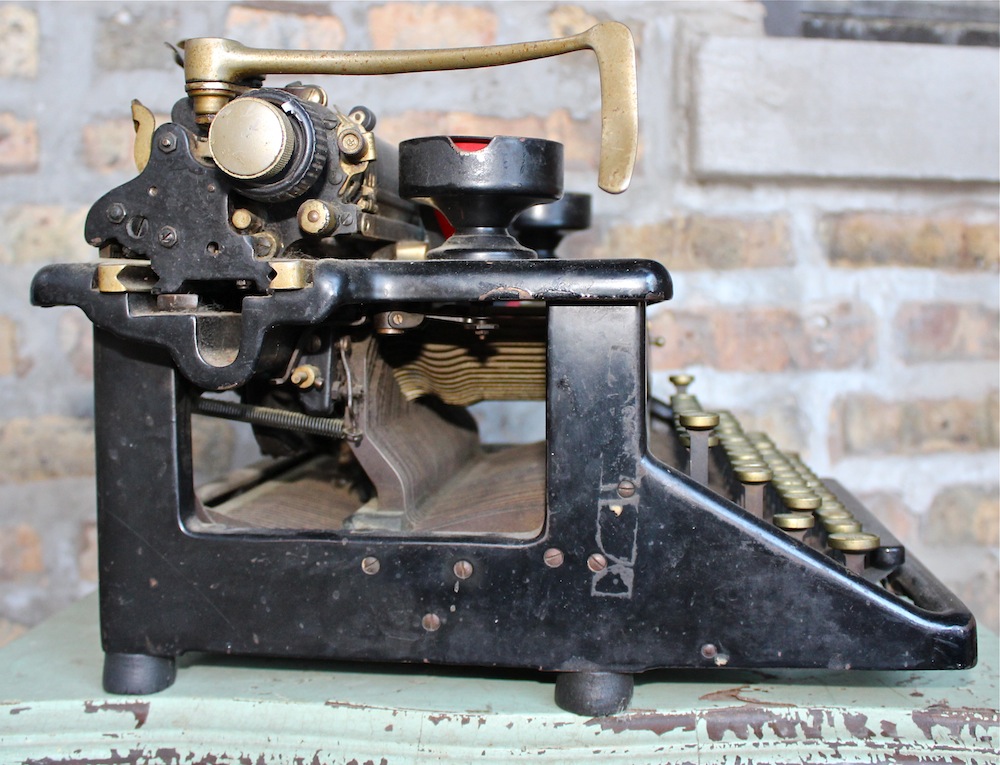

[Close-up view of the backside of the Woodstock No. 5 in our museum collection, which was built in 1922.]

III. A Second Mr. Sears

Up until the market crash, Sears II was setting up the Woodstock Typewriter Co. as a potential leader in innovation. Debuting around 1924, the company’s motor-powered machine, the Electrite, was among the first electric typewriters widely available in the country. The Depression would undercut such tech-minded efforts moving forward, but unlike their crosstown rivals at the Oliver Company—which was wiped out completely by the economic collapse—the Woodstock brand survived, expanding its clientele and competing admirably against the likes of Underwood, Royal, Remington, and the rest.

In 1931, the New York Board of Education called on Woodstock for one of the biggest single typewriter orders on record to that point, requesting 1,305 new machines. A year later, the Pittsburgh Board of Education ordered 623 new Woodstocks of their own. We know this, of course, because R. W. Sears II made a point of informing the national press about such things.

In 1931, the New York Board of Education called on Woodstock for one of the biggest single typewriter orders on record to that point, requesting 1,305 new machines. A year later, the Pittsburgh Board of Education ordered 623 new Woodstocks of their own. We know this, of course, because R. W. Sears II made a point of informing the national press about such things.

In January of 1936, the Woodstock Daily Sentinel ran a particularly rosy story about the bounce-back success of the town’s lone remaining typewriter business. The leadership team of Sears, vice president J. M. Hackney, treasurer J. F. Swahlstedt, and factory superintendent Edward Ebert reported more than a 20 percent increase in both production and total sales compared to the previous year, with 525 employees now sending out 160 machines each day. More importantly, even during the worst days of the Depression, the factory had maintained a regular work schedule and never delayed pay for more than a week.

“With the tremendous growth in popularity of the product,” Sears II told a conference of national salesmen, “with a more seasoned selling organization; with our factory organization working efficiently; and with the finest product we have built, I am sure you will agree that the future presents a most promising outlook.”

When Sears led the visiting salesmen on a tour of the Woodstock plant, they supposedly “marveled at the spirit of craftsmanship evident in all departments,” according to the Daily Sentinel. “On every side was heard comment about the orderly, efficient layout of the plant; the smoothness with which each operation was done and the work passed on down the production line; and the skill and precision of both men and machines.”

[Woodstock’s Model No. 5 actually went through many different iterations over 20 years. Above left is an ad from the late 1920s. On the right is a 1933 Model No. 5, also part of our museum collection]

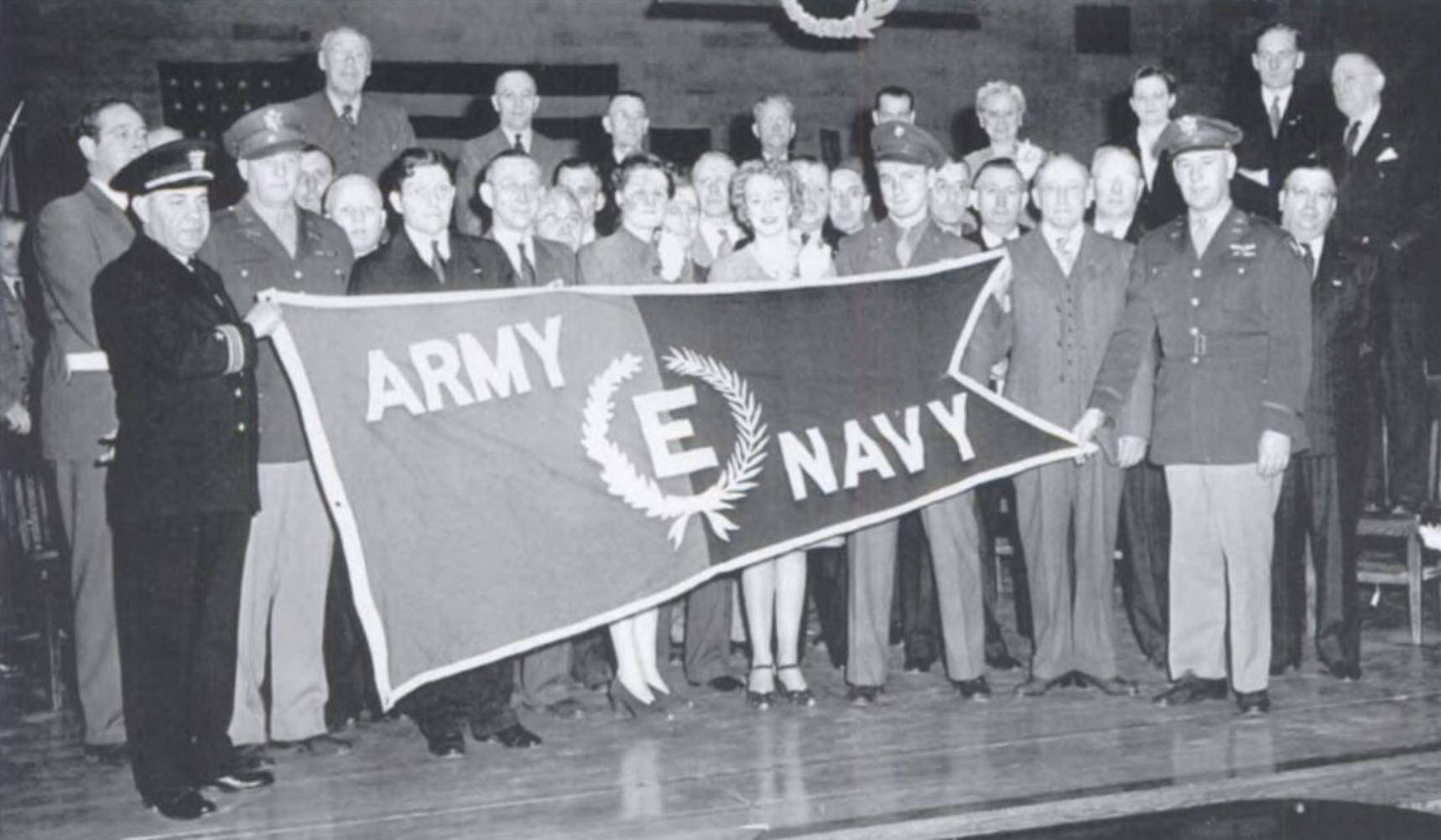

The capabilities of the Woodstock plant were truly put to the test five years later, when America’s entry into the Second World War put the facility into a singularly unique position.

After Pearl Harbor, the War Production Board ultimately required every major typewriter manufacturer in the country to switch over to defense work; making weapons and airplane parts, etc. The one surprising exception was the Woodstock factory, which was tasked with ramping up its typewriter production to essentially serve as the one and only supplier of the machines to the U.S. government and military.

This distinction didn’t come without controversy. For one thing, the U.S. government had pretty severely underestimated how important the typewriter was in the war effort. With all the other plants stopping production of the machines, the country soon faced a massive shortage, leading to a campaign asking civilians to donate their own typewriters for the cause. Secondly, there was plenty of sneering from Woodstock’s rivals, some of which felt that Richard Sears had won his contract through some backroom dealing with War Production Board chairman Donald Nelson, a former vice president at Sears-Roebuck.

This distinction didn’t come without controversy. For one thing, the U.S. government had pretty severely underestimated how important the typewriter was in the war effort. With all the other plants stopping production of the machines, the country soon faced a massive shortage, leading to a campaign asking civilians to donate their own typewriters for the cause. Secondly, there was plenty of sneering from Woodstock’s rivals, some of which felt that Richard Sears had won his contract through some backroom dealing with War Production Board chairman Donald Nelson, a former vice president at Sears-Roebuck.

Regardless of how they earned the responsibility, the Woodstock Typewriter Company and its employees—many of them women—met the enormous challenges of the war with great success, earning an Army-Navy “E” Award in 1944 “in appreciation for their fine work and accomplishment in the production of war equipment.”

Richard Sears was all smiles at the E Award ceremony, but rather than serving as a preview of great peacetime days ahead, the event was essentially a last hurrah for the company as an independent entity.

[Richard Sears II (front row, third from left) accepts the Army-Navy “E” Award in 1944. Other Woodstock employees pictured include Joseph Schmidt, Frieda Schmidt, Ray Roderick, Herman Stienke, Jim Engstrom, Frank Purvey, Henry Leonard, Ed Rogman, Walter Schroeder, James Koca, Frank Readely, William Thomsen, Howard Stone, Melvin Johnson, Bud Offer, and Harold Krull.]

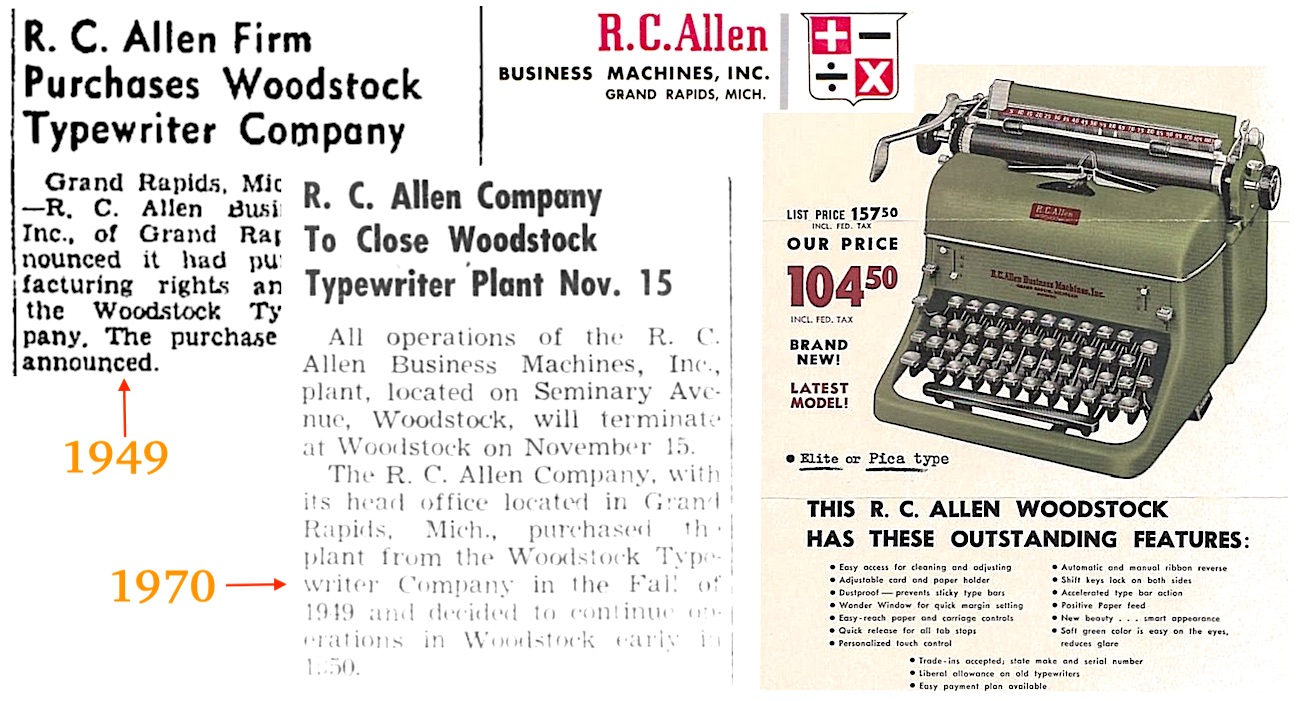

In 1946, shareholder Anna Lydia Sears—widow of Richard Sears, Sr. and mother of Richard II—died at the age of 77. A year later, Sears II made the surprising decision to sell the entirety of his family’s stock in the Woodstock Typewriter Company to the Century America Corporation of Chicago. This decision may have been based partly on health concerns of his own. Two years later, Richard Sears II died at just 50 years of age; the same age at which his father had died.

By 1950, the business had been sold again, this time to R. C. Allen Business Machines, Inc., of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Allen, to the relief of the workers in Woodstock, agreed to keep producing typewriters at the old plant, and did so well into the ‘60s. Like most of the country’s producers of standard manual typewriters, however, R. C. Allen eventually gave up the ghost, closing the factory in 1970. The old Emerson/Woodstock facility went on to serve as the home of Woodstock Wire Works before getting converted into a residential building, now known as the Emerson Lofts.

IV. A Woodstock’s Role in a Great American Spy Drama

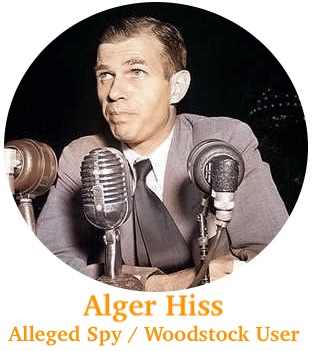

In 1948, just after the Sears family had sold off the Woodstock Typewriter Company, one of the company’s old pre-war machines was suddenly back in the news; serving as a surprisingly vital piece of evidence—and a lightning rod for controversy— in one of the most publicized espionage cases in American history.

The man at the center of this case was a former U.S. State Department official named Alger Hiss. A Baltimore native and a graduate of Harvard Law, the 44 year-old Hiss was, by most accounts, an upstanding, patriotic American. Just a few years prior, he had traveled with FDR to the Yalta Conference during World War II, and later helped in organizing the United Nations. Now, in a shocking twist, this same man was accused of having been a Soviet spy the whole time. The subsequent court drama captivated the nation, and the mystery of a certain Woodstock typewriter soon emerged as a key subplot.

The man at the center of this case was a former U.S. State Department official named Alger Hiss. A Baltimore native and a graduate of Harvard Law, the 44 year-old Hiss was, by most accounts, an upstanding, patriotic American. Just a few years prior, he had traveled with FDR to the Yalta Conference during World War II, and later helped in organizing the United Nations. Now, in a shocking twist, this same man was accused of having been a Soviet spy the whole time. The subsequent court drama captivated the nation, and the mystery of a certain Woodstock typewriter soon emerged as a key subplot.

Hiss had been implicated by a Time magazine editor and admitted ex-Communist, Whittaker Chambers, who testified to the infamous House Committee on Un-American Activities that Hiss had been connected with underground Communist networks since the 1930s. Called before the committee—which was chaired by an ambitious 35 year-old California congressman named Richard M. Nixon—Hiss strongly denied the claim and charged Chambers with libel. Chambers then responded by producing supposed physical evidence of Hiss’s treachery in the form of “the Baltimore documents.”

Essentially, Chambers claimed that Hiss and his wife Priscilla had taken classified U.S. documents, re-typed them at their home, and then passed the copied content on to Chambers, who supplied it to the Soviets. The typewriter used to commit this crime? A Woodstock Model No. 5, obviously!

And so, in a true “stranger than fiction” moment in American legal history, a bizarre quest began to locate the treacherous Woodstock machine, which the Hisses had given away a decade earlier. Why was it relevant? Because, if the typewriter could be produced, and the tiny details of its typeface exactly matched that of the Baltimore documents, it could help theoretically prove Hiss’s guilt. Whereas, if the font didn’t fit, as the saying goes, you would have to acquit.

This can all sound quite confusing here in the digital age, where computers and laser printers have made it virtually impossible to match any physical document to the exact machine from whence it came. During the Hunt for the “Red” Woodstock, however, the prevailing idea was that any standard manual typewriter, much like a piano, would have its own subtly unique character—a fingerprint within its key arrangements and imperfections that could differentiate it from all others; even the machines that shared its make, model, and manufacturing year.

And so, heading into Alger Hiss’s high profile perjury trial in 1949, both the prosecution and defense had a vested interest in trying to track down the typewriter in question. It seemed, realistically, to be a hopeless endeavor. But then, lo and behold, a Woodstock with the serial number N 230,099 magically appeared in court one day, in surprisingly decent condition. Alger Hiss himself, along with his brother Donald, had “found” the machine by following the guidance of various tipsters and supposed loyalists, but this supposed good luck quickly backfired on them.

When tested, the typewriter actually proved to be a shockingly good match for the Baltimore documents, and thus became a key piece of evidence in the eventual conviction of Hiss in his second perjury trial in 1950, resulting in a five-year prison sentence. Hiss, pondering how this could have happened, determined that he had been a victim of “forgery by typewriter”—and that the FBI had clearly planted this imposter Woodstock as a means of framing him.

Was it true? Did the FBI actually go to the trouble of retro-fitting a random No. 5 Woodstock so that it would type in the style of the Baltimore Documents? Did they then also intentionally lead Alger Hiss and his brother to believe they had discovered the original Woodstock, all as part of a set-up?

[Left: The infamous Exhibit #UUU from the Alger Hiss trial, Woodstock Model No. 5, serial number 230,099. Though Hiss’s missing typewriter was said to have been purchased in 1927, this machine’s serial number dates it to 1929. Right: A slightly later Model No. 5 from our museum collection, serial number 355,626, from 1933, which features more of a closed shell design.]

Well, actual FBI records released since the Freedom of Information Act—along with the written accounts of Richard Nixon himself—seem to indicate that the Bureau did indeed know, from the beginning, that the discovered Woodstock machine, Exhibit #UUU, was NOT the original Hiss typewriter. As to whether they manipulated evidence to ensure a known traitor went to prison, or simply used the same tactic to set up an innocent scapegoat . . . the jury is still out on that one.

Alger Hiss would maintain his innocence right on through to his death in 1996, and even today, he still has a small army of defenders taking up his case. In those circles, there are conspiracy theories related to the motives of Richard Nixon—who rode the wave of the Hiss case into the vice presidency just two years later—and J. Edgar Hoover, who could have targeted Hiss simply for his left wing political views. Hiss apologists will also cite evidence that the courtroom Woodstock machine, the N230,099, was later found to have been tampered with; a 1929 typewriter frame fitted with slugs from several years earlier.

For their part, the U.S. government—as recently as the past decade—still firmly denies any such typewriter forgery. The CIA’s own website even published a long piece on the Hiss case by John Erhman, suggesting that Hiss remains the most likely candidate to have been the spy known by the KGB as “ALES,” and that all arguments to the contrary are weak and unsubstantiated at best. He also suggested those still defending Hiss could be setting a bad precedent.

For their part, the U.S. government—as recently as the past decade—still firmly denies any such typewriter forgery. The CIA’s own website even published a long piece on the Hiss case by John Erhman, suggesting that Hiss remains the most likely candidate to have been the spy known by the KGB as “ALES,” and that all arguments to the contrary are weak and unsubstantiated at best. He also suggested those still defending Hiss could be setting a bad precedent.

“The pro-Hiss view,” Erhman wrote in 2007, “consistent with Progressive views from the late 1940s through the present, fixed responsibility for the start of the Cold War squarely on the United States, argued that the government greatly exaggerated internal and external dangers, and claimed that the Hiss case started the McCarthy period. Should this view gain ground in the academy and in popular accounts of the late 1940s and 1950s, debate on current issues will be affected. Intelligence and security agencies may find their analyses of threat under intense suspicion–if the government framed Hiss as a spy and covered it up for six decades, why should Washington’s current claims of internal threats be believed?–because of suspicions that old hysterias are returning. That would be a sad and dangerous development.”

Now that we’re 70 years removed from the trial and more than 80 years on from the alleged creation of the Baltimore Documents, it seems unlikely that Alger Hiss will ever be completely cleared, or that firm proof of his true allegiances will emerge. Maybe he did use his old, trusty Woodstock as a tool for treason. Or maybe he just liked typing up friendly letters to FDR as the whisper quiet Woodstock No. 5 rolled along. Either way, this typewriter remains a unique piece of trivia and one of the more memorable office appliances in American political history.

[Comparing the 1933 Woodstock No. 5 above to the 1922 version reveals some clear design changes over the course of a decade, including a more enclosed construction around the front and sides of the machine. The small logo under the brand name is the Greek god Hermes, which replaced the original golden eagle logo in the mid 1920s. In the early ‘30s, the Equipment Research Corporation of Chicago noted the Woodstock’s correspondence model’s main selling points: “light action, open face construction, speedy in operation, quiet to the point of best operation and efficiency, and other features desirable on a standard typewriter.”]

Sources:

“R. W. Sears . . . Has Purchased the Emerson Typewriter Company” – Waukegan News-Sun, Nov 12, 1910

“The New Woodstock Typewriter” – Typewriter Topics, January 1915

“Leader in Typewriter Field” (Roebuck profile) – Office Appliances, January 1917

“The Model No. 5 Woodstock Typewriter” – Typewriter Topics, September 1917

“Introducing to the Writing Machine Fraternity of the World Mr. L. W. Meckstroth, the New President of the Woodstock Typewriter Company” – Typewriter Topics, October 1917

“Woodstock Typewriter Strike Called Off” – Republican-Northwestern (Belvedere, IL), Sept 26, 1919

“Local Typewriter Company Produces Electric Machine” – Woodstock Daily Sentinel, Nov 20, 1924

“Woodstock Gets Big Typewriter Order” – Pittsburgh Press, Jan 15, 1932

“Local Factory Has Big Year” – Woodstock Daily Sentinel, Jan 7, 1936

“Not a Nice Story” (Donald Nelson & Richard Sears) – Cincinnati Enquirer, Oct 18, 1942

“Army Honors Local Company for Fine Work” – Woodstock Daily Sentinel, March 28, 1944

“R. W. Sears Is Called By Death” – Woodstock Daily Sentinel, Jan 10, 1949

“R. C. Allen Firm Purchases Woodstock Typewriter Company” – Freeport Journal-Standard, Nov 9, 1949

“Typewriter Plant Will Remain Here” – Woodstock Daily Sentinel, Jan 13, 1950

“R. C. Allen to Close Woodstock Typewriter Plant Nov. 15” – Marengo-Republican News, Oct 29, 1970

Images of America: Woodstock, IL, by Nancy L. Baker, 2006

“Once Again, the Alger Hiss Case,” by John Ehrman, Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 51, No. 4, 2007

“FBI Forgery By Typewriter,” by Robert Messenger

“Hiss and Hers,” by Sue Sanders

Archived Reader Comments:

“I have A Woodstock No. 4 that was given to my mother when she was a teenager. I used it through high school and college. I liked to listen to it as my mother typed on it – the sound of the bell at the end of a line.” —Pattie, 2020

“My grandfather sold Woodstock Typewriters. On his 1918 draft card, he showed the address as 23 W. Washington in Chicago.” —thejenr, 2020

I am an attorney that is probating the estate of a woman here in the State of Washington. One of the item in her estate is a Woodstock typewriter that she wanted donated to the Woodstock Museum.

What is the address and contact for the museum, if there is one? Would they want the typewriter?

There is a historical society in McHenry County (where Woodstock is located) but there is no museum dedicated to Woodstock, IL, or Woodstock typewriters. So I’m not sure specifically what she might have meant, unless she found this same page on our site and assumed the Made In Chicago Museum was only about Woodstock typewriters (many, many people make this type of mistake). –Andrew Clayman, Made In Chicago Museum

The City of Woodstock recently renovated the Old Courthouse on the historic square. The Chamber of Commerce has a visitors center inside with some history info and photos. Please consider donating the typewriter to them. Thanks

https://www.woodstockilchamber.com/visitors-center/

Hi, found an old Woodstock Typewriter in an attic of my house in 1987 in Yonkers NY.

Serial #N533268. I know have it with me in Wilmington NC. Can you tell me anything about it? For instance the age? Looking to start clearing out things, so my kids won’t have to deal with item I have accumulated over the years.

Thank you

When did the Woodstock logo go to the front panel of the typewriter?

I have a small (harmonica size)blue Woodstock box, I’m so curious as to what it was used for and how old it is.

Thanks for the great piece, although your history of the so-called Hiss machine and the case is incomplete. The FBI’s initial doubts were based on solid information regarding when the firm had purchased the machine. The serial number just wasn’t close. Later on, when it behooved the Bureau, they claimed serial numbers had been skipped. But everyone who had the machine said it was an unusable mess and the decal was missing. Lo and behold it typed fine in court, and there was it’s decal.

I’ve been able to take pictures of the typebars on the machine. There’s a lot that is fishy about them. As for Hiss being “ALES,” funny thing is the FBI tried to figure out if that was true for nearly three years and dropped its investigation after George Kennan no fan of Hiss’s said there was no way that the Venona account was accurate. I could say more, but this is long enough. I do hate to be lumped with Hiss defenders’ though. I’ve spent 47 years researching the case. I know the record and the files backwards and forwards. That’s how I came to my conclusions.

Dear Sirs! Are reserve parts available to a Woodstock typewriter probably Model no 5 (Serial number not visible). Being a non-professional and expatriate (Norwegian) I am not even familiar with itys correct terminology . The reserve part I need is the small, “roll cylinder” behind and underneath the larger one that together grip the paper and move it during a line shift. As a reult of decades of inactivity, and being stored without releasing the pressure by using the Shift key, the small roll cylinder has become compressed and flattend to a point where is has lost its function, leading to failure in propagadating the paper. Apart from this, the typewriter seems to be perfectly in order (!), except that it needs appropriate new typewriter ribbons (black and black/red). Grateful for info about availability for purchasing as well the roll cylinder as ribbons.

Yourds friendly Vidar Lehmann

My 1929 Woodstock, Serial No. N206863 has covers that snap over each key. Were these key covers intended to protect the keys or simply to make the keys stand a bit higher? Thank you for any feedback.

Mark Lamb

Houston, Texas

Mark33Lamb@outlook.com

I have an old Woodstock typewriter and would love to find a ribbon to fit it. I have tried universal refill ribbons, and they don’t fit. Any ideas of where I can find a ribbon?

Thanks!

I bought a universal one from Amazon…my typewriter is a 1920’s I just put it in and it’s fine

Ribbons are readily available, either in bulk, or sold on spools. You should try Baco Ribbon Supply. There is also a seller in Texas (name escapes me right now) who sells the original style metal spools with or without ribbon.

Thanks for the story relating the history of Woodstock typewriters. When I saw the brand name I wondered if it referred to the town of Woodstock here in Illinois, and was happy to see that it does (did!) . I enjoy reading about the history of products, especially those made in Illinois, so thanks again ~

I am cleaning out my home office. In one old box I found an article typed (obviously) on an old typewriter describing the Automatic “HY-O-LO” DOUBLE VISION COPY HOLDER”. Attached to the article are 3 photos of this holder fastened to a Woodstock Typewriter. The signing on the letter is a Samuel Davis Mathews of Houston, Texas. The zip code on his address is 1.

Hi! I just picked up a tin of typewriter ribbon from the Woodstock company. It’s orange and black and i was wondering if you could tell me around when it would’ve been made?

Hi, I absolutely love antiques/history and particularly enjoyed reading about Woodstock mark in history. I picked up a Woodstock recently at a garage sale, the seller new nothing about it and let it go for $20. I’m curios to learn how to identify the year that it was made. I don’t see any model/serial numbers on it. I’m open to suggestions. Best guess is somewhere between 1930-1948.

Shayna- I have an old Woodstock from 1917 and the serial number is on the bottom of the frame behind the front left foot. I missed it the first time I looked as it is faint, hard to see, and the machine weighs a ton. You can check the year of your typewriter by visiting this page: https://typewriterdatabase.com/Woodstock.5.58.bmys and comparing photos and serial numbers. That’s what I did anyway. Hope that helps.