Museum Artifacts: Super-Triumph Tube Radio (1951, pictured above), Model 4R Long Distance Receiver/Amplifier (1923), Model 808 Tombstone Radio (1934), Model 6D-2620 Radio (1942), Colsol-Tone H511 (1951), Royal 500 Transistor Radio (1960), Model F508V Radio (1964), Spirit of ’76 Television (1976)

Made By: Zenith Radio Corporation, 6001 W. Dickens Ave., Chicago, IL [Galewood]

“You’ve had your last tussle with howling radio static once you tune in this terrific performer. Reaching far beyond the usual FM range, it brings you news, sports, music and market reports where AM and many FM sets are practically useless. All beautifully sharp and clear . . . day or night, summer or winter—even during the worst storms!” –Advertisement for the Zenith Super-Triumph Radio, 1951

By the time the “Super Triumph” tube radio made its debut in the early 1950s, Chicago’s Zenith Corporation was rapidly approaching its own, well, zenith. Operating multiple factories employing nearly 5,000 workers in the Chicagoland area alone, the company had successfully transitioned into the explosive new television market after World War II while still maintaining its place as a long respected leader in radio production and innovation. It was a fine-tuned, international, industrial behemoth—a far cry from its rag-tag, rebellious roots.

That evolution was quite apparent in the design of Zenith’s radio sets themselves, which had gradually transformed from massive wooden “tombstones” to lightweight, plastic, fully portable style icons—shiny emblems of both the Atomic Age and the birth of rock n’ roll.

Where once the radio case was merely a protective shell for the delicate workings inside, mid-century Zenith designers were now paying attention to trends in industrial art, and occasionally establishing new ones along the way. Their efforts weren’t lost on the snobby appreciators of “real modern art,” either, as Zenith took part in a pair of exhibitions at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1944 and 1950, leading the charge not just in how Americans consumed media after the war, but in the way those essential new appliances would look going forward.

To fully understand Zenith’s mid-century dominance—as well as its unfortunate late-century demise—you really need to start at the beginning, during the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, and a little upstart outfit known as the Chicago Radio Laboratory.

[A look at the Zenith radios currently on display in the Made In Chicago Museum. A number of these sets were donated to the collection by Peter Contos and Family, by way of the Edgewater Historical Society.]

History of the Zenith Radio Corp, Part I: Karl and Ralph

The company that would become the Zenith Corporation began quite literally inside a “radio shack”—a nondescript two-car garage in Chicago’s Edgewater neighborhood that served double duty as a makeshift assembly plant and broadcasting bunker.

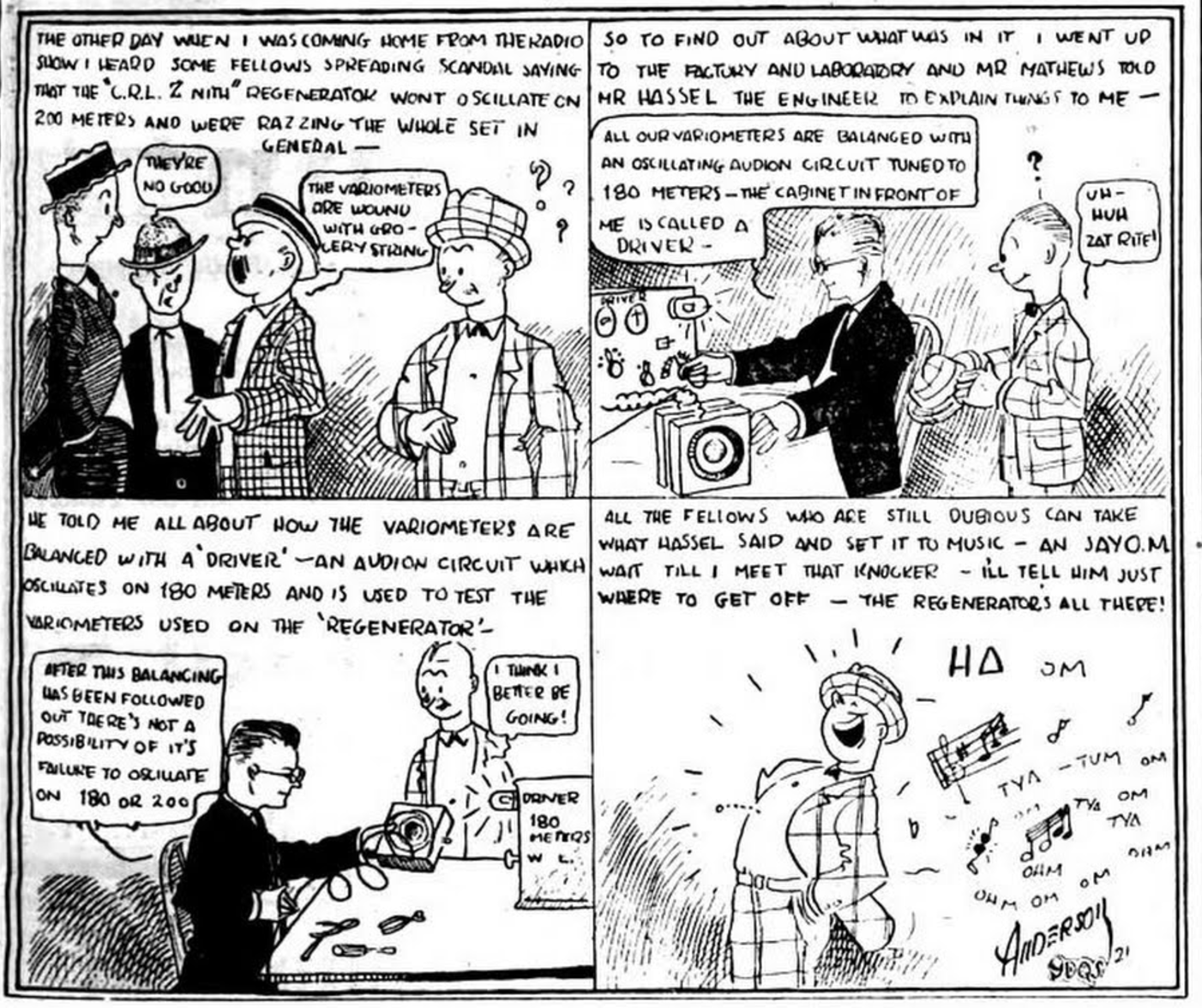

The Chicago Radio Laboratory, as it was originally known, was the brainchild of two baby-faced ham radio nerds in 1918; 22 year-old Pennsylvania native Karl Hassel and 21 year-old Chicagoan Ralph Mathews. During World War I, the two cadets crossed paths at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station and immediately bonded over their shared obsession with oscillating audion circuits and long wave receivers. Now, with the war in the rear-view, both fellas set their sights on what they agreed was the imminent rise of the radio age.

The Chicago Radio Laboratory, as it was originally known, was the brainchild of two baby-faced ham radio nerds in 1918; 22 year-old Pennsylvania native Karl Hassel and 21 year-old Chicagoan Ralph Mathews. During World War I, the two cadets crossed paths at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station and immediately bonded over their shared obsession with oscillating audion circuits and long wave receivers. Now, with the war in the rear-view, both fellas set their sights on what they agreed was the imminent rise of the radio age.

In the beginning, the business was not exactly operating on the same scale as its ambition. Ralph Mathews’s own apartment at 1316 W. Carmen Avenue was the Chicago Radio Labs’ official “headquarters” for a while, with the aforementioned shack at 5525 N. Sheridan Road serving as its “testing station.” The shack itself actually sat on the property of the swanky Edgewater Beach Hotel, but the hotel manager kindly let Mathews and Hassel make use of it, so long as they didn’t cause a fuss. Hotel guests had no idea that the seeds of a corporate titan were growing out there on the lawn.

In a 1919 advertisement in a radio trade magazine, the upstart business boldly announced its arrival: “Shake hands with something new in wireless—a radio manufacturing company producing apparatus designed by men who are prominent in amateur and experimental radio work and know from their own experience what the amateur wants and needs.”

In many respects, Mathews and Hassel were following a script not unlike the Steve Jobs/Steve Wozniak partnership some 50 years later—young tech enthusiasts dive into an industry that’s too new to be fully understood by the public, let alone properly regulated by the government. In both cases, there would be competition crawling out of the woodwork, copycat patent thieving, and alliances to forge and ultimately sever. But while software companies might threaten one another with lawsuits, things were a little bit more Wild West in the early days of radio.

[Above Left: One of the first Chicago Radio Laboratory ads from QST magazine (1919). Above Right: The apartment listed as the company’s address on that ad, Ralph Mathews’s home at 1316 W. Carmen Avenue in Andersonville / Edgewater. Below: The first Zenith testing station at 5525 N. Sheridan Rd. in the Edgewater neighborhood, 1920.]

Part II: Days of the Radio Gangs

Ralph Mathews—remembering his early teenage forays into Chicago’s amateur radio scene—described it more like a Prohibition-style turf war. There were “North, South, and West Side gangs,” he wrote in a 1921 article for QST magazine, “each having as a primary object the annihilation of the aerials [antennas] of the others.”

Radio gangs?! Indeed. With commercial radio not yet in existence, the city was essentially a sea of wireless pirates competing to establish the biggest and best communication relay networks. As a result, there was an incentive for sabotage.

Radio gangs?! Indeed. With commercial radio not yet in existence, the city was essentially a sea of wireless pirates competing to establish the biggest and best communication relay networks. As a result, there was an incentive for sabotage.

“Frankly, Chicago conditions before the war were the worst that this writer has ever seen anywhere,” Mathews wrote, citing a specific occasion when an entire antenna was “forcibly and thoroughly removed” thirty minutes before a scheduled relay time. When a replacement was built, it was manned with armed guards to protect it. “Two friends sat out under the mast with 38-calibre cannons,” Mathews recalled, “and they chased away exactly eight individuals, each with his little side-cutting pliers.”

In typical Chicago fashion, even the city’s geeky ham radio element had to start employing pistol-packing heavies. There needs to be a film about this madness.

“If this condition had continued,” Mathews noted, “Chicago would have been the dead spot in regard to relay traffic. . . Fortunately, however, there were in each of the already existing sectional ‘clubs’ certain individuals having influence and with an unselfish consideration for the radio game as a whole. [Myself] and Mr. F.H. Schnell, then Chicago City Manager, called together these men and the Chicago situation was discussed. As a result, the method of organization now known as the ‘Chicago Plan’ was evolved.”

The “Chicago Plan”—not to be confused with Daniel Burnham’s better-known “Plan of Chicago”—is rarely mentioned as part of the grand history of the Zenith Radio Corp, but it stands as one of the first of many major achievements in which the company played a leading role.

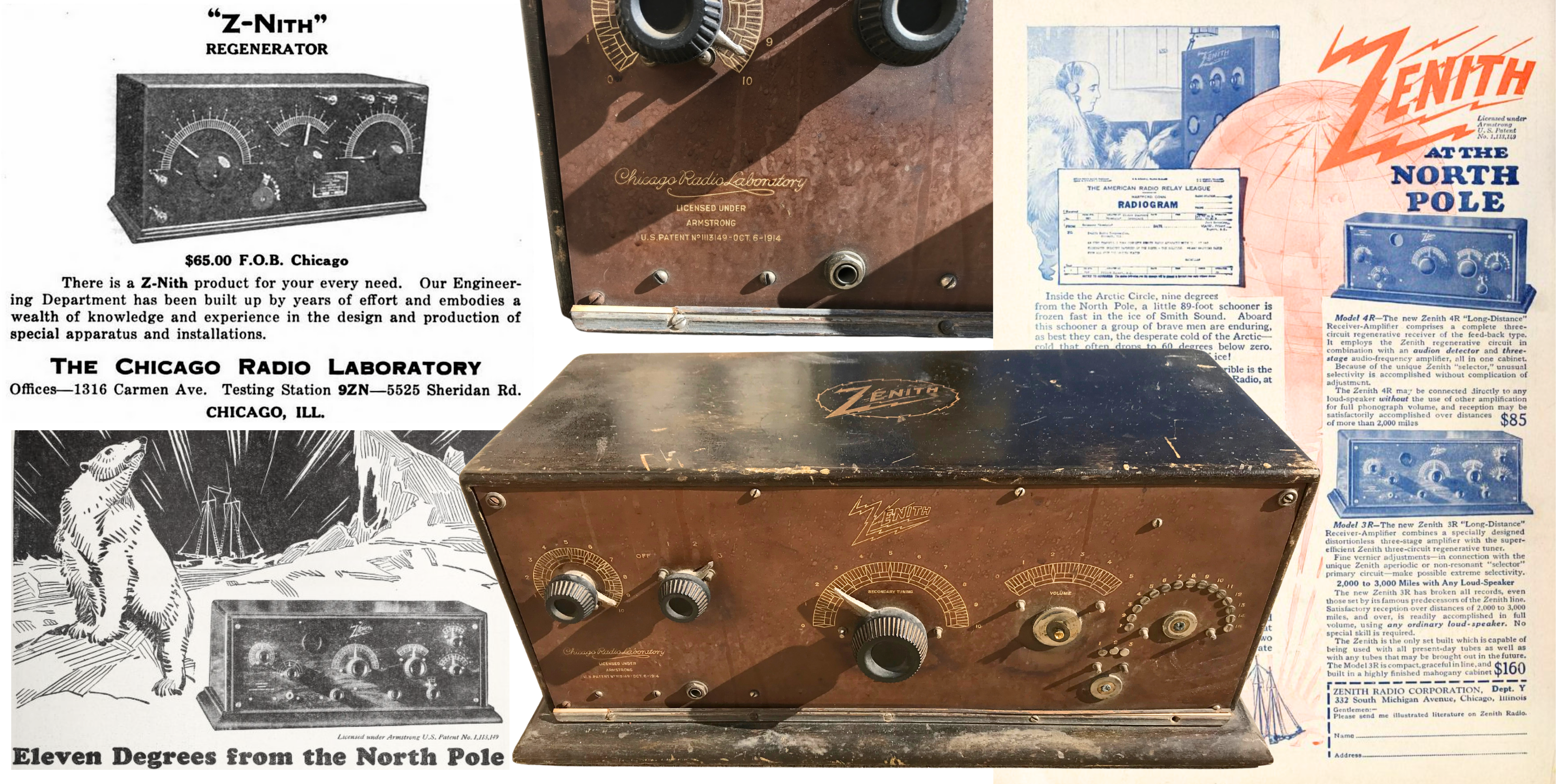

[The Chicago Radio Laboratory started using the Z-Nith brand, a play on the company’s “9ZN” radio call letters, in 1920, as seen in the ad in the top left corner. The other ads above are promoting the company’s Model 4R Long Distance Receiver, 1923, which is part of our museum collection. It gained fame as the radio that went with explorer Donald Baxter MacMillian on his 1923 voyage to the North Pole.]

By 1921, Ralph Mathews had helped negotiate the formation of an Executive Radio Council, with elected representatives from different clubs around the greater Chicagoland area. The council would negotiate terms and regulations for airwave traffic, and if any individual ham user broke these rules or “hogged” the air, his whole club would be fined for it. Social events and baseball games were also held in an effort to create “better friendly feeling and cooperation among the mass of Chicago radio men.” In short time, the program produced excellent results in stemming gang violence, such as it were.

Before we give Mathews too much credit for creating this airwave utopia, however, it’s worth noting that he did have some ulterior motives.

Before we give Mathews too much credit for creating this airwave utopia, however, it’s worth noting that he did have some ulterior motives.

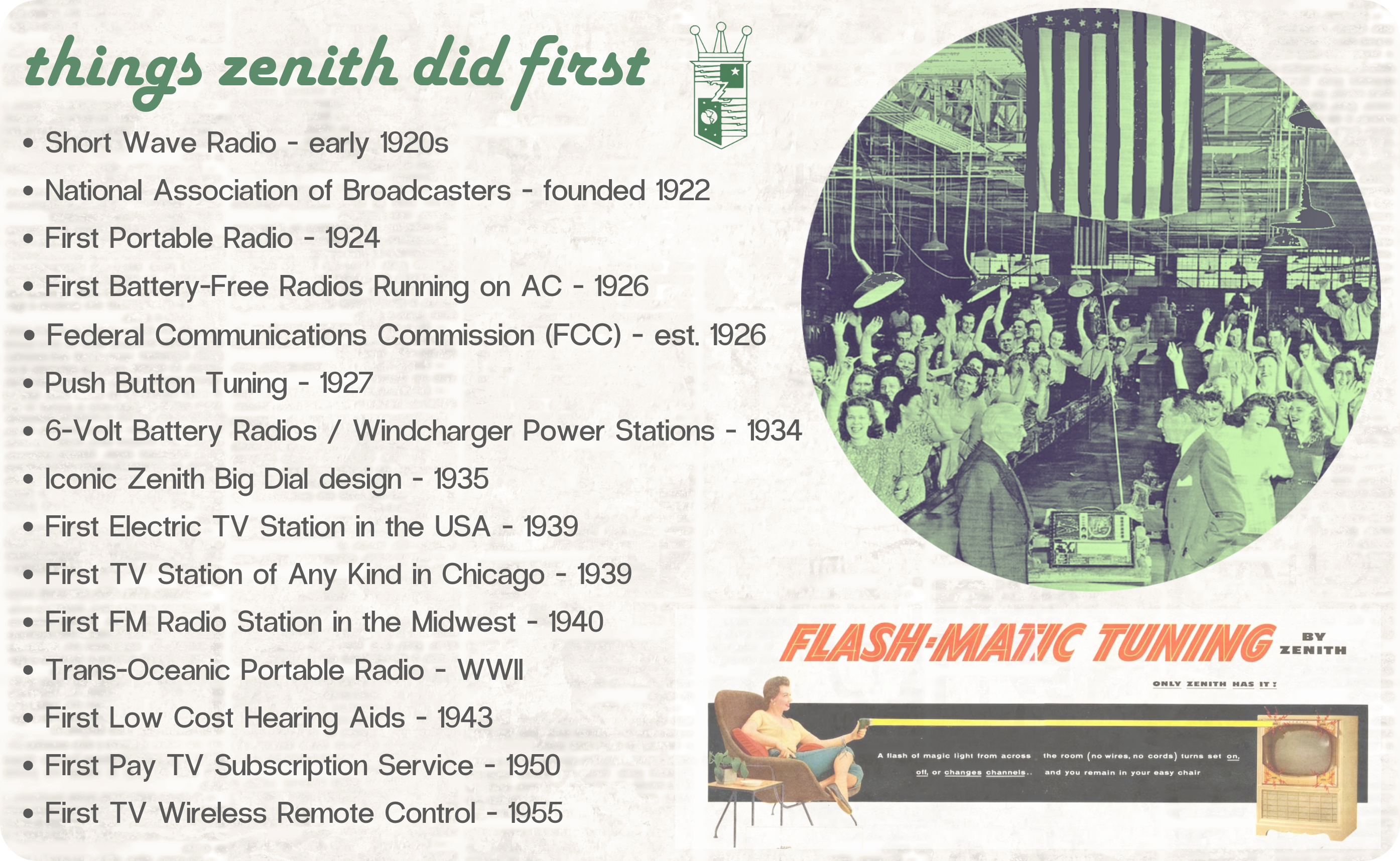

In the first year of the the Chicago Radio Laboratory’s existence, Mathews and Hassel mostly just focused on making equipment for their fellow amateur radio nuts. In 1920, that abruptly changed. First, the duo managed to license the regenerative circuit patent held by one of their heroes, the engineer Edwin H. Armstrong. Then, months later, the first radio broadcasts of a presidential election awoke the nation to the true power of the medium, rapidly increasing demand for quality, affordable radio sets. Mathews and Hassel were ready to take a big step, and cleaning up the riff-raff in Chicago’s radio underworld was a good place to start—essentially clearing the path to regional domination for the Chicago Radio Laboratory.

[The Chicago Radio Laboratory crew at work, 1921. Karl Hassel is the man second from left, standing in the back of the room.]

With the “Chicago Plan” bringing order from chaos, it was on to the next problem: CASH. Or more specifically, a lack thereof.

Chicago Radio Labs’ first catalog in 1919 was put together by Mathews’ father, who worked for a printing company. “It didn’t cost us anything,” Karl Hassel recalled years later, “[otherwise] we wouldn’t have had a catalog. I’m telling you, we didn’t have any money.”

The boys eventually did well enough to move into a more reasonable office space in the third floor of a building at 6433 N. Ravenswood Avenue in 1921, but paying six employees (on top of a $300 per month rental fee) was draining funds in a hurry. They desperately needed an investor, and as the fates would have it, he was about to walk right through their door.

[An employee tunes and tests a fleet of new 1R Receivers and 2M Amplifiers at the Zenith production plant, 1922]

Part III: The Commander

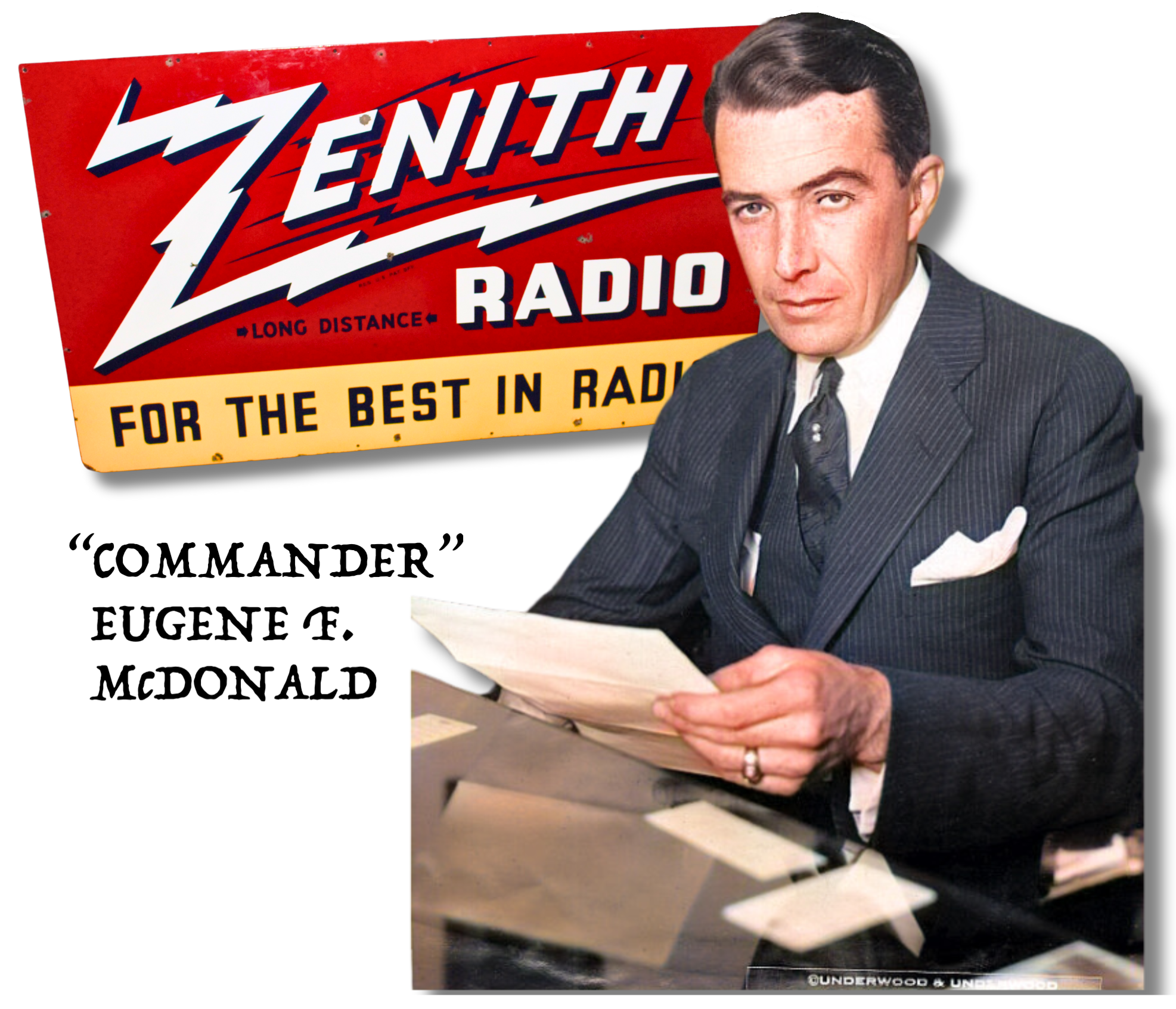

Eugene F. McDonald, Jr., was a 35 year-old high school dropout who’d turned himself first into a wealthy car salesman, then a Lieutenant-Commander in Navy Intelligence during the First World War. He was one of those guys who cast a long shadow; supremely if not irrationally confident. On one particular afternoon in 1921, McDonald made a visit to the Chicago Radio Laboratory, seeking out of “one of those crazy, new-fangled automobile radios” to install in his own car. “I heard you boys can make one.”

Karl Hassel took on the request enthusiastically, since a custom job meant a fat price tag. Fortunately, McDonald was ultimately pleased with his new automobile jambox, and—sniffing a business opportunity—decided to join forces with the radio lads as their new industrial sugar daddy.

Karl Hassel took on the request enthusiastically, since a custom job meant a fat price tag. Fortunately, McDonald was ultimately pleased with his new automobile jambox, and—sniffing a business opportunity—decided to join forces with the radio lads as their new industrial sugar daddy.

For his first executive order, McDonald got Mathews and Hassel to change their radio brand name from Z-nith to just the regular human word, “Zenith,” complete with a snazzy new lightning bolt trademark. Within three years time, the Chicago Radio Lab identity would be scrapped entirely, as the Zenith Radio Corporation was born—with the iron fist of E.F. McDonald steering the ship.

It’s very difficult to overstate the impact McDonald had on Zenith’s meteoric rise over the 30 years that followed. Mathews and Hassel might have had the technical knowledge, but McDonald had the capital, vision, business acumen, and cutthroat instincts to separate his company from an ever-growing pack of competitors.

One of McDonald’s earliest moves was the formation of a manufacturing partnership with Chicago’s QRS Music Company, a leading maker of player piano rolls (a significant music-listening medium at the time). For several years in the early 1920s, much of Zenith’s production moved to the QRS plant at 4829 S. Kedzie Avenue, greatly helping the firm ramp up its output of high profile new receivers like the model 4R, which famously traveled to the North Pole with explorer Donald Baxter MacMillan in 1923.

[Workers building Zenith products at the QRS plant, c. 1921. Top Left: The punch press line. Top Right: Engraving machines for the radios’ front panel markings. Bottom Right: Installation of tuning capacitors for a Model 1-R]

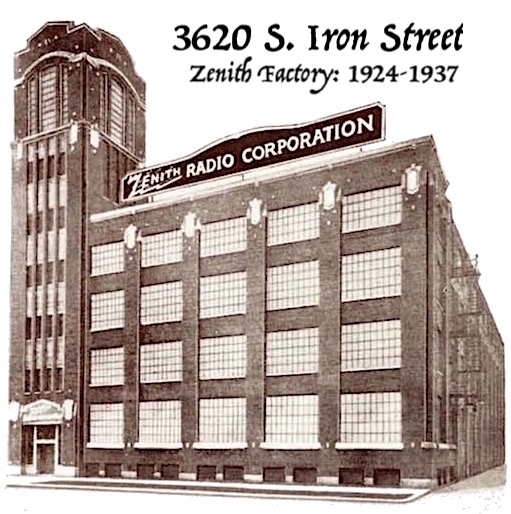

By 1924, the thriving Zenith Radio Corp. was now able to acquire its own large-scale manufacturing facility, located at 3620 South Iron Street in the Central Manufacturing District. This four-story building would serve as the primary Zenith HQ for the next decade, as the employee count ballooned from less than 100 to more than 450 workers by the mid 1930s, even despite the challenges of the Great Depression.

For years, McDonald’s employees called him “Commander,” and there seems to be a general consensus that the name had more to do with his personality than his military rank. Strict and to the point, he swiftly earned his employees’ respect and loyalty, and in turn, kept them happy, adapting to new challenges as the business grew. Unique profit sharing plans were eventually established to make workers feel part of the company’s success, and as a result, labor strikes were thoroughly avoided throughout McDonald’s tenure.

McDonald gradually built an all-star support team during his first decade on the job, hiring treasurer and future VP Hugh Robertson, as well as the company’s most important product development engineer in both the radio and (eventually) television departments, Gilbert E. Gustafson.

Karl Hassel stayed on for the long haul, as well, eventually putting in more than 40 years with the company he’d help launch. Ralph Mathews, by contrast, left in 1928 to pursue an advertising career. It’s possible he didn’t adjust to life with the Commander quite as well as some of his cohorts (he did end up coming back to electronics years later with Westinghouse and Magnavox, and lived well into his 90s).

[Top Left: An early Zenith storefront in Chicago, at Michigan and Huron, 1930s. There’s an Apple store there now, appropriately enough.The other images above feature the Model 808 radio from our museum collection, a “tombstone” design from 1934.]

The Commander poured money into research and development, even during the uncertainty of the ’30s. Having the best product was certainly a goal, but then again, if you do something first, you’re also automatically the best, at least until somebody else tries it. So for McDonald, innovation was everything.

This philosophy needn’t be limited to the science, either. In marketing, too, McDonald wanted to push the envelope, carrying over a Big Top adventurousness he’d developed during his car dealership days.

“Once, when the Commander was selling automobiles, he drove a new car straight up the steps of a Grant Park statue as a publicity stunt,” legendary Sun Times columnist Irv Kupcinet wrote in his memoir Kup’s Chicago. “Another time, he publicized his short-wave radios by traveling north into the Arctic Circle and leading Eskimos in a broadcast songfest.”

[Eugene McDonald invites native Inuits of Greenland to sing into a microphone, sending their voices 12,000 miles over short wave radio to a receiver in Tasmania, thus proving the superiority of Zenith equipment in 1925]

An April 1958 issue of Television Digest added this assessment:

“Whatever else you may think about Zenith’s pres. Eugene F. McDonald—and he’s not a man to ignore, especially as a competent and successful manufacturer and merchandiser—you must concede he’s one of the cleverest publicity hounds in the land. His method is provocation, controversy, anything to get his name and Zenith mentioned—for it helps sell goods.”

That’s not to say good old-fashioned quality wasn’t a major selling point, too—the longtime Zenith slogan made that clear: “The Quality Goes In Before the Name Goes On.” Still, if you want to see how this company grew into one of the great electronics juggernauts of the 20th century, it helps to look at the things they did first.

[Zenith technology promotional film “The Long Corridor,” 1955]

Part IV: Three Cheers for Pioneers

Despite the considerable number of “firsts” they’d already racked up in their first decade of existence, Zenith wasn’t guaranteed anything during the 1930s. With dozens of their old foes falling into bankruptcy after the bubble burst on the original radio boom, any decision about new investments or strategies could similarly spell doom for McDonald and his team. With this in mind, the years 1930-1936 could be seen as the most pivotal in the company’s history, as it not only weathered the economic storm, but took advantage of an opportunity to extend its lead in the marketplace.

By 1937, demand for quality Zenith radio sets was steady enough that the company outgrew its Iron Street plant and relocated to a new, 400,000 sq. ft. facility at 6001 West Dickens Avenue in the Belmont Cragin neighborhood. This complex would be repeatedly expanded over the next several decades, beginning with preparations for Zenith’s entrance into wartime manufacturing.

[Top Left: 1942 Zenith magazine ad. Top Right: Promotional Zenith radio sign from our museum collection, c. 1940s. Bottom Left: Model 6D-2620 tabletop radio from our museum collection, 1942. Bottom Right: Zenith Plant #1 at 6001 W. Dickens Ave., as seen on a 1937 Curt Teich postcard.]

“In a war run by Radar and Radio,” a 1944 employment ad read, “Hasten Victory—Help manufacture vital war equipment. Temporary, Duration or Permanent Jobs. Real post war opportunity.”

They weren’t just blowing smoke either. A huge portion of Zenith’s workforce were women, and many who joined the company during the war actually stayed on in peacetime. In 1946, the company was still posting regular ads specifically seeking out female labor. “Zenith Needs 500 Women and Girls to help us meet the overwhelming demand for the sensational new Zenith Radios—America’s Most Popular Radio. . . A grand place to work with people you like, plus all these other advantages: Higher Starting Rates; Rapid Advancement; Steady Work & Convenient Hours; 5 Clean Cafeterias with Appetizing Meals; Complete Medical Department; Liberal Profit Sharing Bonus Policy.”

Were they paid an equal wage? Of course not. But in an industry associated with a certain breed of collegiate machismo, it was actually highly skilled, working women who were crafting the majority of the precision components on America’s “Golden Age” radios and first-wave televisions.

[Top Left: 1944 newspaper ad seeking wartime workers + a group of workers at the Dickens Avenue plant in 1940. Bottom Left and Far Right: Zenith workers in the 1950s.]

Part V: Changing Tunes

Zenith sales topped $100 million in 1950, and close to 5,000 Chicagoans were earning their paycheck by either designing, building, packaging. testing, or shipping its products. The firm was on its way to becoming America’s number one manufacturer of black-and-white televisions, battling past its Chicago rival, the Admiral Corp. This post-war focus on TV did make radios a secondary focus of Zenith’s commercial manufacturing for the first time, but the shift to bakelite radio cabinets also ushered in a striking new era in the design of these units.

The “Consol-Tone” and “Super Triumph” models in our collection both date from the early 1950s and exemplify the curvier, Space Age look of many of these mid-century tabletop radios. “They’re new! They’re dramatically modern!” reads a 1951 Zenith magazine ad for the Consol-Tone H511. “They’re the smartest radios you’ve laid eyes on in many a year! Inside and out—they’re built to the highest standard of quality known to the industry. Zenith Quality—your safest, best buy for the years ahead.”

The “Consol-Tone” and “Super Triumph” models in our collection both date from the early 1950s and exemplify the curvier, Space Age look of many of these mid-century tabletop radios. “They’re new! They’re dramatically modern!” reads a 1951 Zenith magazine ad for the Consol-Tone H511. “They’re the smartest radios you’ve laid eyes on in many a year! Inside and out—they’re built to the highest standard of quality known to the industry. Zenith Quality—your safest, best buy for the years ahead.”

Another ad from that year, specifically for the Super Triumph, hails the new model’s “crystal-clear, static-free, interference-free reception” with a “giant dial for easy tuning, ‘Flexo-Grip’ handle for easy carrying, and rich maroon plastic cabinet.”

These were quality, portable AM-FM radios that were emerging right at the cusp of rock n’ roll’s arrival, and they would play no small role in the proliferation of that new brand of popular music, as radio owners were able to tune in their favorite stations in their bedrooms or at the beach with an equivalent quality of sound. One of those local Chicago radio stations, incidentally, was Zenith’s own pioneering FM station, 99.5 WEFM (the calls letters standing for “E.F. McDonald,” of course), which was routinely marked with a small dot on the shiny dials of Zenith radios, including the Super Triumph.

Later into the 1950s, Zenith grabbed a growing share of the all-important color TV market, having wisely aligned itself with the NTSC multiplex system that was eventually approved by the FCC as the preferred format.

The new technology that really became E. F. McDonald’s obsession, however, was the one thing he was having far less success bringing to the public: subscription television. Zenith’s own successfully-tested “Phonevision” system was highly controversial in the ‘50s and shut down by the FCC, but McDonald—literally down to the final months of his life—was waging war against what he saw as a dangerous TV monopoly controlled by the two main networks, NBC and CBS.

In a letter to Congress on March 21, 1958, McDonald wrote: “It would be presumptuous on my part to try to point out the extent to which the First Article of the Bill of Rights, guaranteeing free speech, has been undermined by the overpowering and frightening development of TV. Free speech is not primarily the right of the publisher to print, but the right of the public to hear and read all sides of a question. . . . The networks have been able to sway many Members of Congress to oppose even a trial of subscription TV. The networks know that this new service would lessen their coercive power over affiliated stations and give independence to stations that are now dependent on the networks for their economic existence. Their opposition to subscription TV arises from just one thing—the fear of competition.

In a letter to Congress on March 21, 1958, McDonald wrote: “It would be presumptuous on my part to try to point out the extent to which the First Article of the Bill of Rights, guaranteeing free speech, has been undermined by the overpowering and frightening development of TV. Free speech is not primarily the right of the publisher to print, but the right of the public to hear and read all sides of a question. . . . The networks have been able to sway many Members of Congress to oppose even a trial of subscription TV. The networks know that this new service would lessen their coercive power over affiliated stations and give independence to stations that are now dependent on the networks for their economic existence. Their opposition to subscription TV arises from just one thing—the fear of competition.

“This network monopoly, is in fact, a threat to freedom of speech—of vital interest to every printed publication. . . . Suppose for example, we were to elect the wrong man to the Presidency. Suppose he decided to use the tremendous power of TV to promote a ‘non-partisan’ issue, and enlisted the aid of the network chiefs. Suppose TV stations all over the country went on the air with fear propaganda . . . I daresay that such a campaign would produce millions of letters to Congress. Fantastic? The power is there, and it could be made use of if the wrong man came to power.”

McDonald died of cancer less than two months after writing that letter. He certainly had a level of media foresight few of his contemporaries could match, as his concepts of pay television obviously came to fruition a couple decades later. One could argue whether a splintered media has proven better at preventing propaganda than the old network monopoly model. But in any case, McDonald at least realized that people would always hate watching commercials.

[A promotional Zenith Color TV sign from our museum collection, c. 1970]

Part VI: Maximum Output

Within a few weeks of E. F. McDonald’s death in 1958, Zenith lost its long-time engineering genius, Gilbert Gustafson, as well. It was the end of an era, but not the end of the company’s growth period just yet. In fact, financially speaking at least, Zenith reached its apex in the 1960s, topping $500 million in sales by 1966 and employing an eye-popping 15,000 workers nationally and abroad.

The explosion of television certainly remained the big factor in that success, but while most of the TV designs of the ’50s and early 1960s were in the same kind of heavy, over-sized “tombstone” phase that radios had been in back in the ’20s, Zenith was able to rapidly produce the latest generation of lightweight portable radios, made from plastic, at remarkably cheap costs; making the audio side of their business still as vital as ever.

The explosion of television certainly remained the big factor in that success, but while most of the TV designs of the ’50s and early 1960s were in the same kind of heavy, over-sized “tombstone” phase that radios had been in back in the ’20s, Zenith was able to rapidly produce the latest generation of lightweight portable radios, made from plastic, at remarkably cheap costs; making the audio side of their business still as vital as ever.

The Royal 500 transistor pocket radio, as featured in our museum collection, is an early ’60s icon; the kind that every 12 year-old boy utilized to listen to his favorite baseball team when it was well past his bedtime. It was also the much more practical option for the picnic or beach trip, functioning like the smartphone + Spotify of its day.

“This superb new Zenith radio is so powerful it operates where others won’t . . . gives clear reception indoors, outdoors or in a car,” read a 1961 ad for the Royal 500. “Yes, you no longer need both a car radio and a portable! The Royal 500, with its unbreakable nylon case, gives you both!”

With televisions in most houses and transistor radios increasingly popular on the go, it was the old tabletop radio that was now under threat of becoming expendable. Again, though, cheaper plastic models and increasingly colorful, stylish designs kept that end of the business relatively strong, as represented by another of our museum relics, the salmon-toned model F508V, aka the “Tango,” which sold for about $20 in the early 1960s (equivalent to about $200 in the 2020s).

[The “Tango” tabletop radio from our museum collection, model F508V, c. 1964]

Even setting aside the demands of commercial radio and TV manufacturing, Zenith had also retained many of its government contracts long after World War II and the Korean War. So, a great deal of the company’s resources, especially on the R&D end, were going into hi-fi and communications equipment for government use.

All told, the Chicago area alone had a whole legion of Zenith factories in operation during the 1960s, right before the rise of international competition effectively ended the golden era of American electronics.

Zenith’s Chicago Factories (The Numbers as of 1962):

Plant #1: 6001 West Dickens Avenue – 2,500 workers made radio and television sets and Hi-Fi stereophonic phonographs.

Plant #2: 5801 West Dickens Ave. – 300 employees made electronics and servicing.

Plant #3: 1500 North Kostner Ave. – 2,100 employees made government electronics, radio and television components.

[Left and Top Right: Zenith workers at Plant #1, 1960-70s. Bottom Right: Plant #3 on Kostner Ave, opened in 1953]

Plant #4: 3501 West Potomac Ave. – 60 employees performed warehousing.

Plant #5: 6501 West Grand Ave. – 500-600 workers made government hi-fi equipment.

Plant #6: 4245 North Knox Ave. (operated by subsidiary the Rauland Corp.) – 850 workers who made television picture tubes.

Plant #7: 1247 West Belmont Ave. (operated by subsidiary Central Electronics, Inc.) – 100 employees made amateur radio equipment and performed auditory training.

[Zenith ‘s factories at 6001 W. Dickens Avenue (above) and down the street at 5801 W. Dickens were known as Plant 1 and Plant 2. Both buildings are still standing, although several fires in 2017 have left the long abandoned Plant 1 on the cusp of demolition as of 2024.]

Part VII: Fade Out

When Zenith radio and television sales finally started dropping dramatically as that new wave of cheap, east Asian competition emerged in the 1970s, the company found that trying to adapt to the new reality of American commerce was akin to turning around a massive container ship in a narrow canal.

Company chairman John Nevin expressed his frustration openly, challenging that Japan was “dumping” low-priced electronics into the US market in violation of trade laws. By 1977, despite still holding the title as America’s largest television manufacturer, Zenith had no choice but to start cutting its own costs to stay competitive. This meant the elimination of some of the longstanding profit-sharing plans that Eugene McDonald had established, followed by a series of devastating layoffs, including more than 2,000 of the company’s Chicago employees. Nevin penned a letter to all Zenith workers stating that the company “has tried longer and harder than others to protect the jobs of U.S. employees,” but that the failure of the U.S. government to intervene had left them little recourse.

Company chairman John Nevin expressed his frustration openly, challenging that Japan was “dumping” low-priced electronics into the US market in violation of trade laws. By 1977, despite still holding the title as America’s largest television manufacturer, Zenith had no choice but to start cutting its own costs to stay competitive. This meant the elimination of some of the longstanding profit-sharing plans that Eugene McDonald had established, followed by a series of devastating layoffs, including more than 2,000 of the company’s Chicago employees. Nevin penned a letter to all Zenith workers stating that the company “has tried longer and harder than others to protect the jobs of U.S. employees,” but that the failure of the U.S. government to intervene had left them little recourse.

Understandably, Zenith’s loyal Chicago employees didn’t respond well to finding out that so many of their jobs were moving to Mexico and Taiwan. For weeks, angry protests were held around the various Zenith facilities and outside the Daley Center in downtown Chicago, but this type of scene was all too familiar in the late ’70s, and no amount of anger or public sympathy could alter the trajectory of things.

[Above: Zenith employees at outside the Daley Center, protesting the company’s mass layoffs in 1977. Below: The bi-centennial “Spirit of ’76” Zenith portable television, produced a year prior and now part of our museum collection]

Through its history, Zenith had usually managed to bounce back from slumps by pivoting into new technology and anticipating the next great electronics frontiers. In the 1980s, the instinct was the same, as personal computing now represented the best opportunity for American tech manufacturers to make hay in the 1980s. And so, after seeing some success with its subsidiary Zenith Data Systems, the company was officially re-organized as the Zenith Electronics Corporation in 1984, with a focus on this field.

Unfortunately, despite a continued reputation for quality products and some promising developments in TV speakerphones and HDTV technology, there was no Commander McDonald this time around to lead the Zenith ship back to shore. With commercial sales still suffering, the last Chicago area factory shuttered in 1998, and Chapter 11 was filed shortly thereafter.

As the 21st century dawned, Korea’s LG Electronics purchased the remaining American chunk of the company. Technically speaking, Zenith still exists today as a division of LG, with offices in Lincolnshire, Illinois (under the name Zenith Electronics). But its more glorious past is entombed at places like the abandoned Plant #1 at Dickens and Austin Avenue in Chicago. A major fire here in 2017 further hollowed out what was already a crumbling husk of a once mighty headquarters of American industry and ingenuity.

[Left: The water tower over the abandoned Plant 1. Right: One of several fires that broke out at the abandoned Plant 1 in 2017. Below: Drone footage from 2022, by Hawkwind Droneworks]

As of 2024, the Dickens Avenue complex was still yet to be demolished despite ongoing discussions to put it out of its misery. The news has been better for Plant #2 just down the road, however, which underwent a surprise renovation in the 2020s and is now a commercial kitchens and modern food production facility.

As another noteworthy bright spot, one of the earliest Zenith / Chicago Radio Laboratory facilities—the three-story building at Ravenswood Avenue and Schreiber Ave.—has also recently been re-purposed as a unique public workspace.

The Chicago Industrial Arts and Design Center is a pretty novel concept, welcoming anyone to learn about and utilize a wide range of industrial equipment for welding projects, woodworking, casting, 3D printing, and more (once certified). It’s basically like a gym membership for crafty folks—something the old Zenith boys probably would have gotten behind.

[Photo Above: The first Zenith factory space was located on the third floor of this building at 6433 N. Ravenswood Ave]

[Chicago Radio Labs promotional comic strip from QST magazine, 1920]

[Chicago Radio Labs promotional comic strip from QST magazine, 1920]

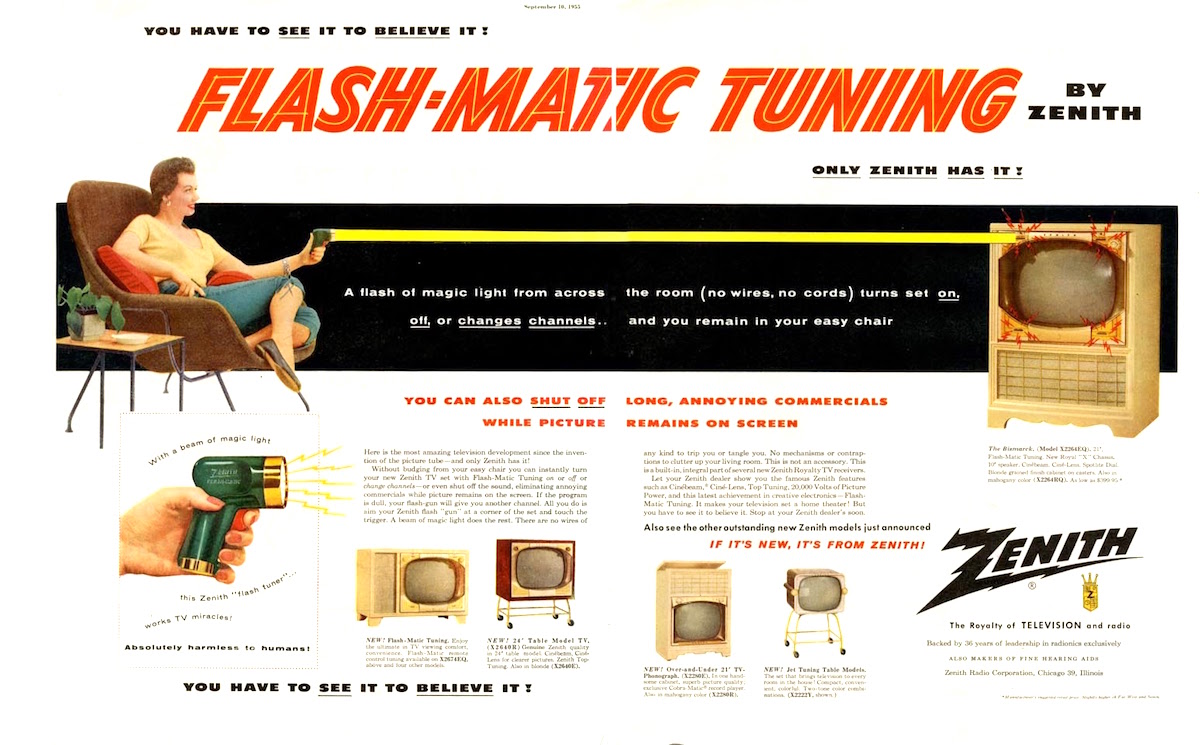

[1955 advertisement for the Zenith Flash-Matic TV remote, invented by Eugene Polley]

[1955 advertisement for the Zenith Flash-Matic TV remote, invented by Eugene Polley]

[Zenith 70th Anniversary promo film, 1988]

Sources:

“Zenith Electronics Corp.”– Encyclopedia of Chicago

Television Digest – May, 1958

Kup’s Chicago, by Irv Kupcinet

QST, Vol 4, May 1921

“Condolences for Zenith” – Daily Calumet, Oct 4, 1977

“Three Amateurs Induced Into Consumer Electronics Hall of Fame”– ARRL.org

“This Super Cool Hackerspace Lets You Build Anything” – DNAInfo.com

Archived Reader Comments:

“My grandfather was Gilbert Gustafson. I’m so proud of all his accomplishments and just sorry I was never able to meet him. Looking forward to organizing all the Zenith info and doing some writing about his life.” ––

” —

” —

Very engaging !!!! Can you put on web the historical foto of an american G.I. with his Zenith Transoceanic radio on a willis jeep ?

I have a Zenith TV. It is a color Sentry Zenith Systems Space Command and it says it was manufactured in 1983. I was curious to see if anyone in the Zenith companies or I guess I should say the companies who bought them would be interesting in purchasing this? Thank you Kathleen Barrett. And I do have pictures that I can upload and it works

My parents met at Zenith. My dad, Marty Vaagen, started there before the Depression, laid off during the Depression and returned after it. He talked about production halting during WWII and the scrutiny of employees as they worked on war efforts.He ended up becoming a Union Officer and then President of the Union…Independent Radionic Workers of America IRWA.

my Aunt Alberta schmidt Missak worked for zenith but not sure which plant or when she started working. I assume she worked at Plant 1 or Plant 2 but possibly Plant 6. She lived in chicago, il but moved out to lake villa, il and commuted. On sept 30, 1958 she along with 4 other Zenith employees were killed in a horrific care accident near grayslake il. They were car pooling to and from zenith everyday. If anyone knows of Alberta Missak and what plant she worked at please let me know!

My father, Edward Raffaelli, worked as an engineer for Zenith in Chicago from the mid 1960s-1977. Not sure what plant. I have found old drawings he made and we still have a few zenith radios. When he passed we had a lot of tubes and other things from zenith that he was working on at home. Not sure what happened to all that stuff. Would love to connect with anyone who worked with him.

I’m sitting here Christmas morning 2022, listening to Christmas music on my Great uncle’s 1954 Zenith Am Fm radio console with the Cobramatic turntable. He bought it brand new. I inherited it in 1994 after he passed at age 100. In the 28 years I’ve been using it, it hasn’t had a single issue . All original im sure, the 68 year old speaker sounds wonderful, it has absolutely no hum or hiss at all. Just pure beautiful music. I have many other Zenith radios from the early 50s and my parents 1961 Blonde black and white console also with a Cobramatic turntable. I have a Zenith TALL case radio from 1940 my moms parents bought new. Mom told me the family all sat next to it all day December 7 1941 listening to the pearl harbor attack. Without a doubt, Zeniths products were/are top quality products!

I just found Ben Calhoun’s piece about the closure of Zenith’s Melrose Park plant. Have a listen: https://backstory.newamericanhistory.org/episodes/a-history-of-manufacturing-in-5-objects/6/

Ben Calhoun, a producer of This American Life, and formerly a radio journalist for WBEZ, did an audio documentary serveral years ago about the closure of the Zenith plant in Melrose Park. I can’t find the audio anywhere right now, which is a shame. It is an incredible and emotional look at the pain that comes with the loss of a large manufacturing operation. It is a MUST listen if you ever get the chance.

Hello. I would like to learn more about manufacturing process’ during some years(i.e. radio dial faces, wood lamination process—glues used.)

I am starting a renovation company in Huntsville, Alabama called Craft & Trade Works. We want to provide high quality restorations for many items. This could be performed very well if we could learn more about manufacturing processes used during early company history. Is this information available?

hi my is Debbie i have a Zenith radio number s- 22922 that i would like to get fix can you help me THANK YOU

I am looking for former Zenith employees who may have worked with my dad, Alex Stone. He worked at Zenith from 1955 to 1975, VP Sales and Marketing

Please contact me if you worked at Zenith during that time or know of someone still living that worked at Zenith in sales, marketing, advertising… Contact me at onthebluestone@gmail.com

Hi, my mother Joyce whitehead worked at zenith in 1967, I’m looking for my father who also worked there his name is David Green . If anyone know of him can you please contact me. It’s been 53 years of searching. Thank you in advance

Hi Lucille, do you know what department your mom worked in? I am looking for former Zenith employees who may have worked with my dad Alex Stone from 1955 to 1975.

Hello – This was a very engaging history of Zenith and profile of one of its founders, E.F. McDonald.

My husband worked at Zenith’s classical music radio station WEFM from 1965-1974 eventually rising to the position of Program Director. WEFM had originally been a non-commercial radio station but converted to a commercial station around 1964.

E.F. McDonald’s first foray into radio broadcasting was in the 1920’a at station WJAZ that broadcast from the so-called “Crystal Studio” at the Edgewater Beach Hotel in Chicago. (check out the URL below to an article he wrote for a book entitled “Radio Broadcast, Vol. 4”, 1924. ) Perhaps the results of his listener survey may have planted the seed for his eventual founding of WEFM as a classical music station – call letters EFM=Eugene Francis McDonald.)

WEFM at 99.5FM on the radio dial, was originally a vehicle in the 1940’s to market Zenith radios and later t.v.’s. while serving up classical music. It was hailed as the nation’s “first FM” station. In 1974 the station was sold to G.C.C. corporation. A citizen’s advocacy group fought the sale tooth and nail in the courts, but they eventually settled their lawsuit (see reference below) and GCC switched to a rock n roll format in February 1978. Most of WEFM’s L.P.’s were donated to radio station WNIB and WBEZ. Remnants of that WEFM L.P. collection now reside in the DePaul University library in Lincoln Park.

E.F. McDonald was an amazing individual. His accomplishments, including building Zenith into a vibrant and successful corporation and establishing a well-respected Chicago classical music station, were wide-ranging and visionary.

References:

“Six Year fight to save WEFM” by Sammy R. Dana in the Journal of Broadcasting.

http://www.tandfonline.com

E.F. McDonald article, Vol. 4, Radio Broadcast (magazine), 1924

I have an original letter in answer to a telegram sent in 1937signed by an engineer who later was on the board of directors. Is it valuable.

The high quality of both The Zenith radio and electronic company and this article is very apparent. I recently inherited a Zenith radio likely from the 1960s. It was sitting up in an attic likely for decades and it still works. The only radio I will likely ever need to buy. Thanks for giving me an afternoon read!

Hi, do you know a David Green? Who worked there in q967

Hi Lucille, I am looking for people who may have worked with my dad at Zenith from 1955 to 1975. Did David work in advertising, marketing or sales?

I worked for Zenith from 1954 to 1998, from 1959 on in the Test Equipment Dept.

Many memories!!

Hi Richard, if you have any specific Zenith stories or photos you’d like to share, we’d love to hear more. Feel free to contact us at contact@madeinchicagomuseum.com

I have a plate that is from a transmitter (do not have transmitter), it says :

YACHT MIZPAH TRANSMITTER MODEL – A N ART -13 SERIAL NO. 101 CALL LETTERS WC – 2980 MANUFACTURED BY ZENITH RADIO CORP. CHICAGO, ILL.

I googled this and came up with AN ART-13 made by Collins Radio but could find anything about Zenith making this transmitter. Does anyone know anything about the Zenith transmitter?

My dad, Peter R Weiler was Chief Radio Engineer and Assistant Division Chief; he last worked at the Howard Street address in Evanston.

My grandmother worked at Zenith during WWII assembling radar equipment. When I was a young “hacker” in the early 70’s she could STILL remember (accurately) all of the resistor color codes. As far as I know those Zenith paychecks were the only paychecks she received from an employer in her life. I think that housewives (that’s what they were called then) in the neighborhood thought that it might be fun and a patriotic duty.

My grandparents didn’t need the money, my grandfather was working as a machinist 60-70 hours a week during the war and was raking it in (protected, could not be drafted due to his needed skills) but there was nothing to buy and he was too tired to do anything with money anyway.

I have a small collection of Zenith Trans-Oceanics made in the 50’s to the 70’s that may have been hand-assembled and wired (no printed circuit boards) in the same factory complex that she worked at. Of course, they still work just fine.

I worked at plant 1 from 1966 through 1969, making Test Equipment & It was the best job I have ever had. I bought one of their Radio’s from the Employee Special Sales. Later on, my apartment had caught fire & that Radio melted somewhat, but it still worked. I’m just sad that the Plant is so deserted now-a-days, cause there are so many memories that will never die, by so many employees, in which some are still living. That abandoned 4-block Plant is loaded with all our memories, and it sure would be great to see it Renovated & housing some other great company, as Zenith was.

I started working for Zenith in1961 and was trained to be an Industrial Engineer at Plant #3

on Kostner Ave. just south of the Helene Curtis plant. The Helene Curtis plant had an explosion that year which resulted in a fatality at our plant which faced Helene Curtis across

a parking lot. In that same parking lot we had a bunker filled with explosive detonators which were used in the M412 fuses we made for the government. It was very fortunate our bunker did not explode at the same time.

My grandmother had one of the first remotes,everything was zenit in her house.She told me she worked out of a garage building radios and was their first employee could this be true the timming is correct. she lived on montrose ave in chicago

My dad was a former Zenith employee worked at Plant 1 and Plant 2 , worked as a maintenance mechanic.

Zenith radio and phonograph built in 1940 is available for donation to made in Chicago museum. I can send photos if interested.

Hello,

I would like to add more.

In 1980 I worked at pt.31 in Glenview ,Illinois ( the last office we had– Goldstar bought us). I traveled to Canada (once), Chicago (many times) El Paso,Texas (many times), Mexico—(specially for Cable TV,many times). It was a the best time for working there—-extremely wonderful— a wish everyone enjoyed it— with great people( I see people later) ,great systems and great products. I lived only six miles away.I could write a book about my times there, but I will not, like my wonderful times, at lunch,my ventors,my Sunday trip to El Paso, and much more.

Thank you for this pleasant ime(God and my Dad– wanted me to work there)

I found a bunch of Zenith radio Corp. BOXES that your company used to package its products in..The boxes are all in great condition, and 1 of them says model number 52 made back in 1952.Do these boxes have any value to anyone since they’re so ancient/antiquish? If so please respond back to 765-238-9824 or 765-960-6976…Ask for Shuan thank you

Hi I have what I believe to be the only Model 630 Battery Tester made by Zenith. Could yous give me any information on this model. I have Googled it and have done web searches on it and haven’t found any information on it . Thanks

Hello,

This is extremely interesting. I worked at Plt 31 for 16 wonderful years.

Thank you

Ed Cappelle

Thank you for such a thorough and engaging article on Zenith history. My dad worked for Admiral in Chicago from the late ’40s until 1969. He got into the electronics field courtesy of the GI Bill, earning a degree from the DeForest Institute after WW 2. The quality and sophistication of design found in Zenith products were second to none, and although dad worked for Admiral and received a discount on their products, the family owned a Zenith console TV in the 1960’s. Take a look at current ebay listings for Zenith radios and you will see some of the most innovative and artistic industrial design ever produced in America, a cornucopia of sleek art deco and, later, jet-age inspired objets d’art of museum quality. Zenith was synonymous with top quality performance and design in the golden age of radio.

I have one Zenith ten band portable word radio transistor. It is marvelous. I do not use it now days since it requires 10number type D cells which are expensive for me.This set was made in 1950.

I have another ten band transistor- Grundig Yatch Boy 100, it is less expensive to use, it is also good.

Zenith radios are excellent.

Was your 1939 mirror-in-lid blond TV set used to show a horse race in a late 1940s movie? I vaguely remember a seeing a similar set in it. This was the first time I a picture of a TV set. I later learned that your set was updated in 1942 with a flyback type HV power supply and shorter neck CRT along with other design changes. I also have read that this was an experimental set installed in a remodeled radio-phonograph cabinet and was kept in one of your museum collections.

I hope you help answer my long remembered trivial curiosity from my childhood. I am very wishful that this TV set is still preserved in a mseum or collection somewhere. BTW I still vividly recall my parents’ large Zenith console with two FM bands, Cobramatic record changer and mysterious 6AL7 tuning eye. Yeah, I still have my blond 1954 chairside set and my white1958 “owl eyes” transistor radio.

I just so happened to come across this ( RADIO) & I’M WONDERING HOW MUCH ITS WORTH TODAY. IT’S IN VERY GOOD CONDITION FR ITS AGE & EVERYTHING WORKS….. CONTACT:::::: SCOTT ANDERSON EMAIL= kimnjeff47@gmail.com